- 0 Shopping Cart

Urban Growth in Rio de Janeiro – Brazil

Welcome to the Urban Growth in Rio de Janeiro – Brazil main menu

What is the location and importance of Rio de Janeiro?

How has Rio de Janeiro grown?

Social and economic opportunities associated with the growth of Rio

What are the challenges associated with the growth of Rio?

How is urban planning improving the quality of life for the urban poor in Rio de Janeiro?

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Please Support Internet Geography

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

Urban Transformations in Rio de Janeiro

Development, Segregation, and Governance

- © 2017

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro 0

INCT Observatório das Metrópoles, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Comprehensive coverage of urban transformation and urban dynamics in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in the last thirty years

- Essential reference book for urban researchers, public officials and social activists

- Fully illustrated with colorful maps and pictures of Rio de Janeiro metropolis

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

Part of the book series: The Latin American Studies Book Series (LASBS)

10k Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

This book provides an overview of urban transformations taking place in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in the last three decades. It analyses urban dynamics within the metropolis and its relationship with Brazilian urban networks.

This book is written by researchers from the Brazilian Metropolitan Observatory in Rio de Janeiro. The aim is to study urban transformation and stagnation with regards to urban mobility and infrastructure, social analysis of territory, housing and housing market, metropolitan governance, demography, residential segregation and inequality of opportunities, among other topics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hidden Urban Geographies: The Case of Barcelona

The South American Urban System

The Economic Drivers of Urban Change in the Gauteng City-Region: Past, Present, and Future

- urban dynamics in Rio de Janeiro

- urban governance

- urban politics

- urban development

- urban networks

- urban infrastructure

- urban housing

- urban geography and urbanism

- latin american politics

Table of contents (16 chapters)

Front matter, metamorphoses of the urban order of the brazilian metropolis: the case of rio de janeiro.

Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro

Territory, Economy and Society

Productive and spatial changes.

- Hipólita Siqueira

Spatial Transformations

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro, Marcelo Gomes Ribeiro

Social Transformations

- André Ricardo Salata, Michael Chetry

Demographic Transformations

- Érica Tavares, Ricardo Antunes Dantas de Oliveira

Family Transformations

- Rosa Maria Ribeiro da Silva

Segregation and Inequalities

Segregation and population displacement.

- Ricardo Antunes Dantas de Oliveira, Érica Tavares

Segregation and Real Estate Production

- Luciana Corrêa do Lago, Adauto Lúcio Cardoso

Segregation and Occupational Inequalities

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro, Juciano M. Rodrigues, Filipe Souza Corrêa

Segregation and Educational Inequalities

- Mariane C. Koslinski, Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro

Segregation and “Racial” Inequalities

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro, Filipe Souza Corrêa

Citizenship, Public Policy and Metropolitan Governance

The favela in the city-commodity: deconstruction of a social question.

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro, Marianna Olinger

Political Culture, Citizenship, and the Representation of the Urbs Without Civitas : The Metropolis of Rio de Janeiro

Local democracy and metropolitan governance: the case of rio de janeiro.

- Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro, Ana Lucia Nogueira de Paiva Britto

Entrepreneurial Governance: Neoliberal Modernization

- Orlando Alves dos Santos Junior

Transport Management: The Renovation of the Road Pact

- Igor Pouchain Matela

Editors and Affiliations

About the editor.

Luiz Cesar de Queiroz Ribeiro is Professor at the Institute of Urban and Regional Research and Planning (IPPUR) at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He is the national coordinator of the Metropolis Observatory (INCT) and Visiting Professor at the Social Sciences Institute at the University of Lisbon, Portugal.

His research specialties include: urbanization, metropolis, urban dynamics, national territory, socio-spatial inclusion/segregation in metropolis, urban governance and management.

Get Citation

Using Rio de Janeiro as the case study city, this book highlights and examines issues surrounding the development of mega-cities in Latin America and beyond. Complex dynamics of urbanization such as mega-event-driven development, infrastructure investment, and informal urban expansion are intertwined with changing climatic conditions that demand new approaches to sustainable urbanism. The urban conditions facing 21st century cities such as Rio emphasize the need to revisit urban forms, reintegrate infrastructure, and re-evaluate practices.

With contributions from 15 scholars from several countries exploring urbanism, urbanization, and climate change, this book provides insights into the contextual and environmental issues shaping Rio in the age of globalization. Each of the book’s three sections addresses an interdisciplinary range of topics impacting urbanism in Latin America, which will be accessible to researchers and professionals interested in urbanization, urban design, sustainability, planning, and architecture.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 | 4 pages, introduction, chapter 2 | 13 pages, the impact of future sea-level rise on rio de janeiro, chapter 3 | 9 pages, one katrina every year, chapter 4 | 12 pages, changing informality, chapter 5 | 15 pages, staging the city, transforming the slum, chapter 6 | 17 pages, barra da tijuca, chapter 7 | 19 pages, the elite enclave of barra da tijuca, chapter 8 | 11 pages, costa, coast, and clay, chapter 9 | 12 pages, barra olympic park project, chapter 10 | 11 pages, resilient urban design for flooding areas, chapter 11 | 15 pages, mixing modernisms and measuring climate literacy, chapter 12 | 14 pages, climate adaptation in rio, chapter 13 | 12 pages, urban planning for resilience.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

- Editorial process

- Publication Fee

- Subscription

Cidade Oceanico. Environment and Urbanization in Rio de Janeiro

Shopping options, subscription and single issue prices.

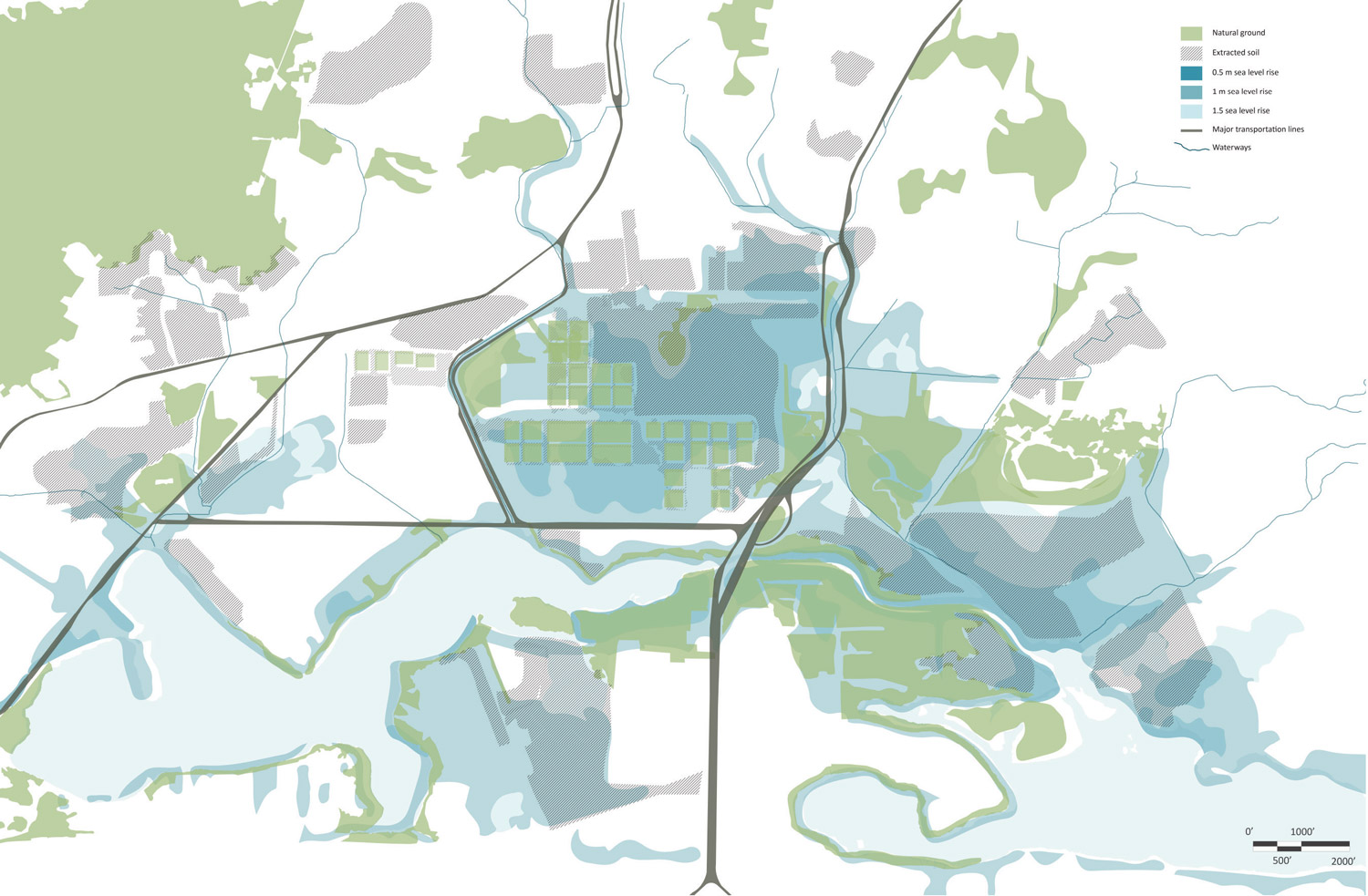

Using Rio de Janeiro as a case study in urbanization within the context of climate change, this multi-year urban design studio examines the challenges of addressing rising sea levels in one of Latin America’s largest cities. As a coastal metropolis, Rio requires that heterogeneous networks be woven between ecological and 21 st century urban design processes. Yet, Rio continues to grow in low-lying, ecologically sensitive areas - and this has been exacerbated over recent decades by mega-event driven development coupled with inter-dependent informal urbanization. These forces characterize Zona Oeste, the focus area of the design initiative. This essay reflects on an international urban design pedagogy that seeks to integrate strategies to address climate change, rising sea levels, and unpredictable growth. Inherently, this project opens up a discussion into many sensitive questions regarding historical and cultural responsiveness. Filtered through the work of Lucio Costa, his proposals for Baja da Tijuca, and opportunities to re-engage the legacy of a modernist plan, students engage this rich context through a discursive design prompt with implications for both pedagogy and practice within and beyond Rio de Janeiro.

In 2014, NASA released research projecting higher than previously predicted global sea level rise due to irreversible climate changes. By the year 2100, sea levels are expected to rise by 1 to 2 meters [3.2 to 6.5 ft.] worldwide. 1 Climate change has already contributed to the growing frequency of torrential rainfall around the world. As architect and educator Fernando Lara has illustrated, historic colonial models in the Latin American context have contributed to a situation in which tropical cities face regular flooding. Europeans came to the colonial arena having experienced environments that often received less than 50 cm [20 in.] per year of rain. However, many regions in Latin American experience more than twice that amount annually, and the hardscape traditions of the colonial city were not well equipped for the increased presence of rainfall. 2 As cities like Rio de Janeiro matured, by density, extension of impermeable surface, and development measures, issues surrounding water management have become increasingly important.

As a coastal metropolis, Rio is characterized by natural water systems requiring heterogeneous networks be woven into ecological and twenty-first century urban design processes. Urban flooding and mudslides continue to plague the city - thereby raising questions to be addressed regarding the relationships between “environment” and “urbanization.” This is compounded by the difficulties of providing potable water to many sprawling fringe areas and the difficulties associated with providing sanitation networks and other necessary urban infrastructure and amenities that support urban expansion. Yet, Rio continues to allow growth in far-flung areas that are often low-lying and ecologically sensitive. This situation has been exacerbated over recent decades by mega-event driven development coupled with inter-dependent informal urbanization. These forces characterize Zona Oeste, or Rio de Janeiro’s Western Zone, making it a compelling area for design investigation.

This paper reflects upon a three-year collaboration between UNC Charlotte’s Master of Urban Design program and the Pontifical Catholic University in Rio’s Department of Architecture and Urbanism. Through a discussion of three summer workshops (held in 2015, 2016, 2017), each four-weeks in length, this essay describes fundamental strengths and challenges of international collaborations, and particularly a design pedagogy attempting to integrate ecological strategies within historical and speculative future narratives. The teams of students (including both US and Brazilian students) faced considerable challenges within the setting of design workshops, which were held on PUC-Rio’s campus. Challenges stemming from historical, cultural, and modernist traditions critically bounded the studio in both productive and limiting ways. Students aimed to avoid the trap of Modernism’s grand narratives; for example, instead of solely relying on the implantation of Euro-centric urban models, the students explored urban characteristics found within Rio’s local urban conditions both past and present. This close attention to the local provided a contrast to past movements focused upon the universal. However, global contexts were not ignored as teams of students explored ways to face rising sea levels. Their work illustrates the challenges of implementing environmentally sensitive strategies that are intended to perform in future scenarios for both pedagogy and practice within and beyond Rio de Janeiro.

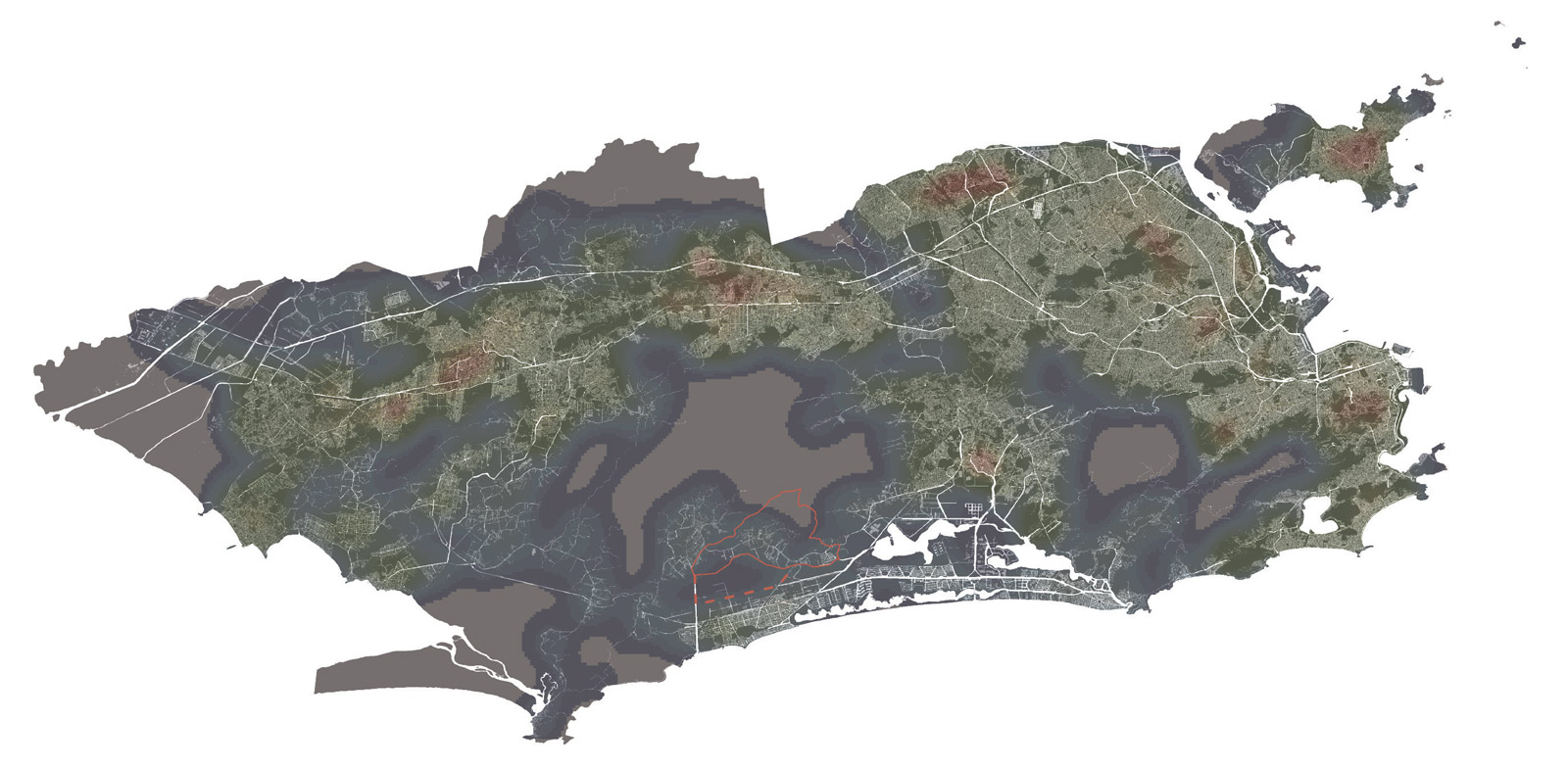

READING RIO

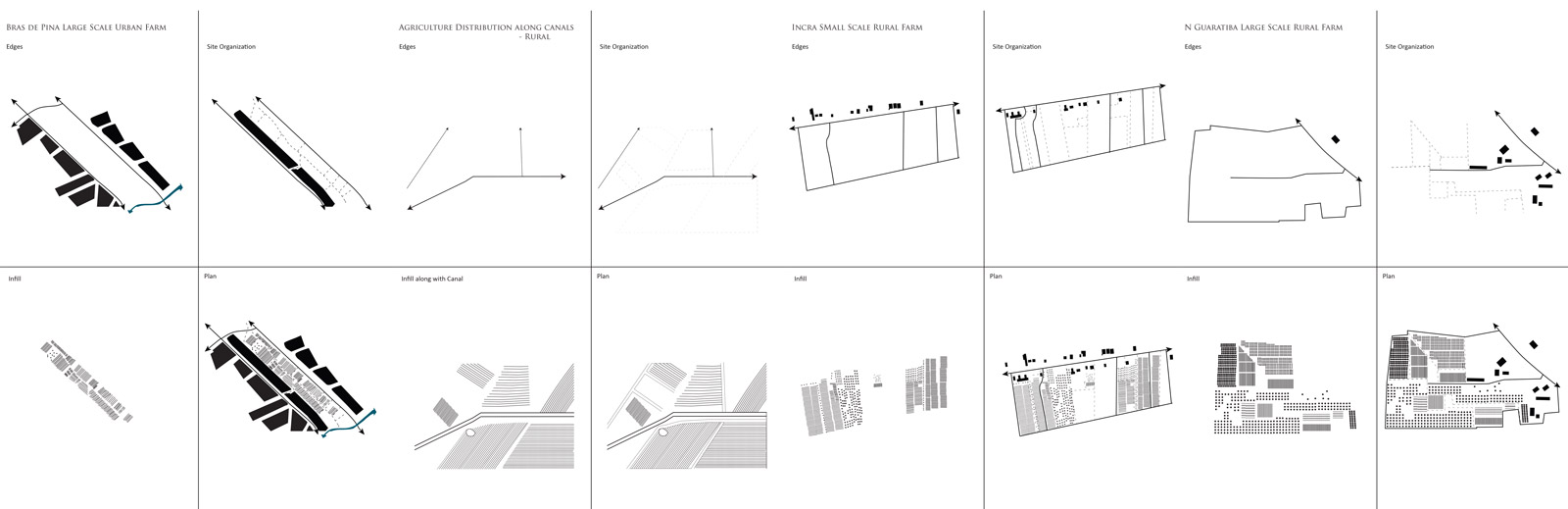

Unlike many historical urban narratives and design methodologies, such as modernist visions of idealized city organizations, the studio began by examining and tracing the existing conditions of Rio while also aiming to read the past in the present through maps and diagrams. Rio seems to have been nestled into an iconic landscape often with little regard for climatic conditions such as hydrology and rainfall. While the city was established, and has continued to grow, as an impervious urban surface, we attempted to become acquainted with the city, its inconsistencies and hybridizations, and its relationships to water. We attempted to introduce our urban design students to a foreign context without judgment; in other words, students were tasked to quickly explore the existing fabrics of the city in order to identify unique characteristics that may drive design integration at a later date. This speedy “deep dive” initially focused upon normative urban design research (block structures and typologies of building and open spaces, for example). Further dissections of density and programmatic complexities revealed other types of urban characteristics participating in the uniqueness of Rio. Ecological and hydrological patterns, cultural legacies of Colonialism, and Modernism, played key roles in the intellectual development of the design interrogation and led to the identification of typological variations specific to the city of Rio de Janeiro.

This search ultimately led to specific guiding principles, techniques, and fundamental questions. Described as a form of urban DNA, the unique cellular qualities of Rio’s various constituent urban elements provided a way to view basic ecological and urban codes. The search for Rio’s DNA was intended to prevent students from importing urban ideas rooted in a prevailing “ism” (New Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism, Modernism, etc.). Instead, this exercise was intended to provide a useful palette for engagement with the city on its own terms and through its own language of form. Then, through edits and revisions, urban transformations could be introduced. We saw this as offering an ability to reframe the city through its existing conditions so that Rio may more readily absorb contemporary patterns of development and their consequences. In this sense, we aimed to have students understand urban design within the specific context of cultural elasticity - cultural in the sense that Rio represents a unique set of social circumstances rooted in a city that has been built through manipulations (both formally and informally) of a local ecology.

It is important to note that this approach does not posit a singular future or a singular continuation of what exists through the repetitive imprinting of urban patterns. Clearly, Rio’s current context (particularly with respect to water and urban growth) is not ideal; “natural” hydrological patterns have been altered radically over time and are difficult, if not impossible, to reestablish. Areas in which new growth occurs are often impacted by extreme development pressures ranging from the influence of politically-charged mega events such as the Summer Olympics, the World Cup, or the Pan American Games. These formal, large scale initiatives tended to occur in the lesser developed areas of the city - due in part to the sheer scale of investment - but they were followed by inter-dependent forms of informal urbanization. This pattern of contrast between the highly formalized global force alongside an equally impactful localized trend set the stage for questions that highlighted the fragile ecology of Zona Oeste and the city at large.

In this sense, the work developed in this multi-year set of studios builds upon methods that enable designers to understand what “is” in order to project what “is possible.” As the students diagnosed existing conditions in various parts of Rio, three specific driving factors of urbanization were identified: “hydrology,” “housing,” and “transit.” Rio de Janeiro’s development patterns have historically followed the water’s edge and typically involved a manipulation of both topography and coastline in order to introduce new geographies for transportation networks aimed at opening up new areas for housing and development. The city’s famous Zona Sul, which includes the beachside neighborhoods of Copacabana and Ipanema, was a result of large-scale intervention along hydrological space. In fact, the city has developed over time from the historic colonial center southward through expanded engineering efforts that involved the removal of hillsides and the creation of artificial coastlines throughout areas of Botafogo and Urca (the location of a small neighborhood at the foot of Sugar Loaf mountain). This southern march of development also marks different eras of formal housing construction from the late 1800s through the early to mid 1900s and coincides with the rise of the Brazilian nationalism, during which Rio served as the capital city.

Unpredictable Typologies, Centro Metropolitano.

Zona Oeste: Environment and Urbanization

Barra da Tijuca is a coastal area west of Rio’s famous Zonal Sul where the wealthy areas of Leblón, Ipanema and Copacabana can all be found. Barra da Tijuca lies within the larger Jacarepaquá Basin, a “double barrier systems” watershed bounded by the Atlantic Ocean, lagoons, marshes, and mountains. 3 This kind of geographical area is particularly susceptible to climatic changes and sea level rise given its geological formation over time and its location along the coast. Storms and heavy rainfall can cause strong tidal shifts and flooding, which contribute to canal blockages and lagoons overflowing natural edges onto adjacent lands. As sea levels rise as a result of rising global temperatures, Barra da Tijuca will likely become increasingly exposed to these kinds of climatic events. 4 Thus, urban development patterns in Barra da Tijuca amplify the need to re-evaluate and integrate infrastructure across multiple scales.

Our multi-year studios concentrated on Zona Oeste because it represents the current challenges facing the city. Although the area has remained under-developed, more recently rapid development has moved westward, formally encroaching on its land. Barra became the primary site of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games; and, therefore, a decade prior to the games development efforts focused on and intensified investment in the area. Interestingly, Barra represents only 4.7% of the city’s total population and only 13% of the city’s overall geographic footprint but it accounts for approximately 30% of the city’s overall tax base. Rapid growth and luxury residential developments have fueled the local economy. The areas’ resulting affluence, perceived safety, and its proximity to the coast all contribute to the zone’s allure making it the fastest growing area in Rio. The allure is also tied to the area’s relative newness. The construction of the 1970s Lagoa-Barra Highway sparked development along the coastline characterized by private and gated high-rise communities, including luxury condominiums, pools, athletic courts, private groves, and private lakes. These communities were specifically imagined as neighborhood-condo developments with each high rise residential tower serving as a private suburban neighborhood complete with active security personnel, gates, and fences. The result is a coastal area now resembling a vertical form of the North American suburban cul de sac .

Three unique urban circumstances exist within the greater region or zone of Barra da Tijuca: Vargem Pequena, Centro Metropolitano, and Recreio dos Bandeirantes. While quite different, they all share the fact water levels will rise, land is soft and often sinking, and a fragile ecosystem is threatened. These specific conditions produce urban forms deriving from “struggles of economics against nature” - struggles shared by many global post-metropolitan regions. 5 While envisioned as a modernist oceanic utopia by Lucio Costa in the late 1960s, Barra da Tijuca fell prey to global market forces and residential development patterns that essentially privatized and divided the entire zone into vertical gated communities connected through auto-oriented networks and interspersed with monumentally scaled nodes. This, of course, coincided with the military-government sponsorship and a legacy of nation-building movements in which urbanization was deployed (both in physical and social form) as a symbol of modernization and of a modern nation state. In order to promote growth, policies were put in place that enabled privatization of the Barra da Tijuca region and allowed a handful of development interests to dominate. In hindsight, this has resulted in development patterns that today resemble a series of what Lars Lerup has called “stims” (points of stimulation) floating within a field largely dominated by “dross” - or uninspired “economic residues of the metropolitan machine.” 6

Residential Density, Zona Oeste.

Lucio Costa’s Barra

Barra da Tijuca, at the time of Costa’s planning efforts, was geographically remote and largely rural despite having been settled in the mid-1600s. In the cases of Vargem Grande and Vargem Pequena, which date to approximately 1667, the agrarian settlement patterns that continue to dominate were established by Benedictine monks. Their large landholdings persisted over time as private agri-businesses grew in later eras. A number of factors have worked to slow development since that time: unstable soils, large private agricultural land-holdings, and marshlands. However, by the 1960s, and as the country sought to modernize, Barra da Tijuca became a focus for national interests. With the introduction of the Lagoa-Barra Highway, this became a more accessible area adjacent Rio de Janeiro’s wealthiest neighborhoods in Zona Sul. Zona Oeste was imagined as a new regional center for both the city and the state of Rio de Janeiro. Economic development and a new regional metropolitan center in Barra were seen as such important challenges that the country’s most prominent architect and planner, Lucio Costa, was commissioned to create a vision and plan for the area in 1969. Inspired by the same modernist principles as those used in the design of Brasilia, Costa outlined development in Barra using separated land-uses, monumental axial boulevards, and a system of open spaces intended to free the ground plane to public access and views to the ocean. In his words, the new regional center would become the world’s most beautiful Cidade Oceanico, or Ocean-side City. 7

The diagrammatic framework established by Costa’s pilot plan for the area introduced a new urban pattern unlike any other characteristics in the city at that time. The proposed morphology in the plan was so radically different from anything previously built in Rio de Janeiro that it has been described as a rupture in both the physical and social forms of city overall. For example, his plan excludes pedestrian scaled spaces and neighborhood destinations such as corner cafes or bars. 8 Instead, the area was organized around two parallel primary axes, Avenida de las Americas and Avenida Sernambetida (now Avenida Lucio Costa), that framed coastal areas for urban growth. These two axes were intersected by a perpendicular axis, Avenida Ayrton Senna, which stretched from the oceanfront to the base of the mountains, thereby forming one edge of the new regional central district known today as Centro Metropolitano. The figure-ground of Barra was similar to that of Brasilia: one dominated by the isolated vertical towers spaced approximately one kilometer apart, which intentionally allowed large green spaces to flow freely between them.

While the morphology of the region is different from that of other iconic areas in Zona Sul such as Leblon, Ipanema or Copacabana, what Costa’s plan offered - in combination with architectural piloti -based typologies, was a new way of occupying the ground plane. Particularly interesting was the fact that this schematic approach to the organization of this new expansion zone essentially framed the ground-plane as an open public space; the proposal formed an “open space parti .” Radically imaginative, Costa ultimately proposed a city whose public spaces were virtually extended from the hillsides to the beachfront by lifting all buildings off the ground and up onto piloti . While the individual elements of this urban architectural typology (elevated urban housing combined with open ground plane) were not unique, the combination of the two in a geographic condition like that of Barra da Tijuca provided potential innovative opportunities, which fostered student design speculation during our three summers in Rio. Costa’s vision was of a green city dominated by natural landscapes. Vistas to both mountains and the coast, democratic access to a new, and extended, public realm opened the city up for social, political, and cultural revolution. It is crucial to keep his utopian goal of balancing the natural with the developed in mind; Costa’s vision involved an inter-woven pattern of landscape, infrastructure and architecture that, in many ways, is less like Corbusian “towers in the field” than it is a precursor to environmentally driven urbanism that we see in the work of many twenty-first century design practices.

Centro Metropolitano

While Costa had been commissioned in 1969 to design a master plan for the Barra de Tijuca, only fragments of his plan are visible on the site of Centro Metropolitano today. The few traces of Costa’s plan that do exist within this area provide evidence of his larger mega-block urban structure and a road network that connects to the larger region. Centro Metropolitano, which is located immediately North-East of the 2016 Summer Olympic site, is now emerging as a mixed-use private development spurred by the economic activity and investments of the Olympic games. However, mixed-use in this context translates to mixes of building uses within a development, rather than mixed programs within a single building (as might be more typically seen within North American contexts or other parts of Rio).

Lucio Costa’s schematic section for Barra da Tijuca (top, based upon conceptual sketches) and student conceptual sectional strategy below.

In many ways, Centro Metropolitano came to represent the most pressing development challenges facing Ozona Oeste and the city at large such as large scale infrastructural development, speculative development driven private investment and a need to address increasingly difficult challenges presented by water in its many forms. One of the prominent developers in the area engaged our second student group and actively entertained design ideas that proposed development patterns differently than convention might dictate. While his needs differed from our studios’ initial interests, this developer was struggling with two ideas that seemed in keeping with Costa’s vision for Barra da Tijuca, which drew us in: the struggle to create a robust public realm through new neighborhood open spaces and to mix housing typologies (market rate and affordable) in an effort to break down social and class divisions that characterize so much of the urban fabric in Rio (walled boundaries between formal and informal neighborhoods, for example).

The two other sites that our studios explored over the three-year studio sequence, Vargen Pequeña and Grande and Recreio dos Bandeirantes, represented other unique challenges but each predate current development pressures. However, each of these sites face similar challenges relative to water: Vargen Pequeña and Vargen Grande are both down slope along hillsides and, thus, face hydrological pressures posed by water moving from the hills to the ocean. Recreio dos Bandeirantes is located adjacent to a national coastal rainforest preserve and bounded by coastline on the southern edge. As the topography slopes, downward towards natural waterways and the ocean, these areas also face challenges from flooding, run-off, and associated sanitation needs. However, for the purposes of this paper, we focus upon Centro Metropolitano as it represents a largely undeveloped site, it provides a direct connection to current development forces, and it resonates with a global historic legacy (Modernism) and a local cultural history.

Unfortunately, Centro Metropolitano itself is not suitable for conventional development. Due to a high-water table, the soft soils of the basin in which it sits, and the sensitive ecological systems that it is a part of, standard construction and economic models are weakened. Given the presence of water, both in the soil below and above ground (in the form of canals, lagoons and the ocean), it is easy to understand why larger site is unstable. This unstable ground has required contractors to raise the level of construction sites by two meters. Thought of as the solution, soils are imported and compacted to prevent future sinking. Once the new soil has been laid down, each construction site sits vacant for approximately two years so soils will fully settle before foundational construction can occur. The larger surrounding area to the south and west, much of which has been built upon, now resembles a series of gated vertical communities contrary to the open ground plane as imagined earlier by Costa.

Interestingly, Centro Metropolitano is controlled by four different major developers, each of whom owns approximately one quadrant of the overall site. The general goals of the overall development have been characterized by new high-end office and residential developments offered as a contrast to aging and congested areas of the historic city. However, the developer involved in Centro Metropolitano who engaged our studio in 2016 is actively seeking to challenge those conventional market-driven patterns as described previously. By seeking to find ways of breaking down the mega-block scale of his quadrant and by attempting to mix social housing models, the developer struggled to incorporate more pedestrian and environmentally sensitive forms of urbanism. Given this context, Centro Metropolitano represented the friction of contemporary development, which seemed to superficially follow Costa’s effort in plan (mega-block grid outlined by Costa), while many of the ingredients of urban form -specifically those associated with public space - were rejected. Given Costa’s vision for this site to become a new centralized regional district, Centro Metropolitano in its contemporary incarnation represented an opportunity to reinvent architectural typologies, to integrate landscape, and to weave legacies of Brazilian Modernism into a hybrid form of flexible urban outcomes.

Photograph of Centro Metropolitano and a view down one of Costa’s proposed axial boulevards as it appeared in 2016.

RESEARCH AS SPECULATION

In order to initiate the studio pedagogy, research focused upon uncovering three specific topics that would ultimately lead to a series of design speculations. While studying micro urban conditions through DNA studies aimed at uncovering the elements of a local urban code, regional explorations were performed utilizing the lenses of “hydrology,” “housing,” and “transportation.” These larger regional network studies provided the context for understanding existing ecological constraints including the damaging impacts of development since mid-twentieth century to the present. These three thematic research modules guided the process of identifying both challenges found across Rio, and documenting outcomes of existing urban behavior. In other words, our students sought to identify urban consequences of the past and present by carefully tracking evidence of planning pressures within Rio’s regional geography, urban forms, and lines of infrastructure. In this sense, the aim was to begin with the existing DNA of the city itself and carefully edit in order to introduce new patterns and typologies that could be implemented in Barra da Tijuca in ways that simultaneously remained consistent with local histories and potentially served as a transition into new forms of coastal urbanization (or into a twenty-first century version of a Cidade Oceanico).

“Hydrology.”

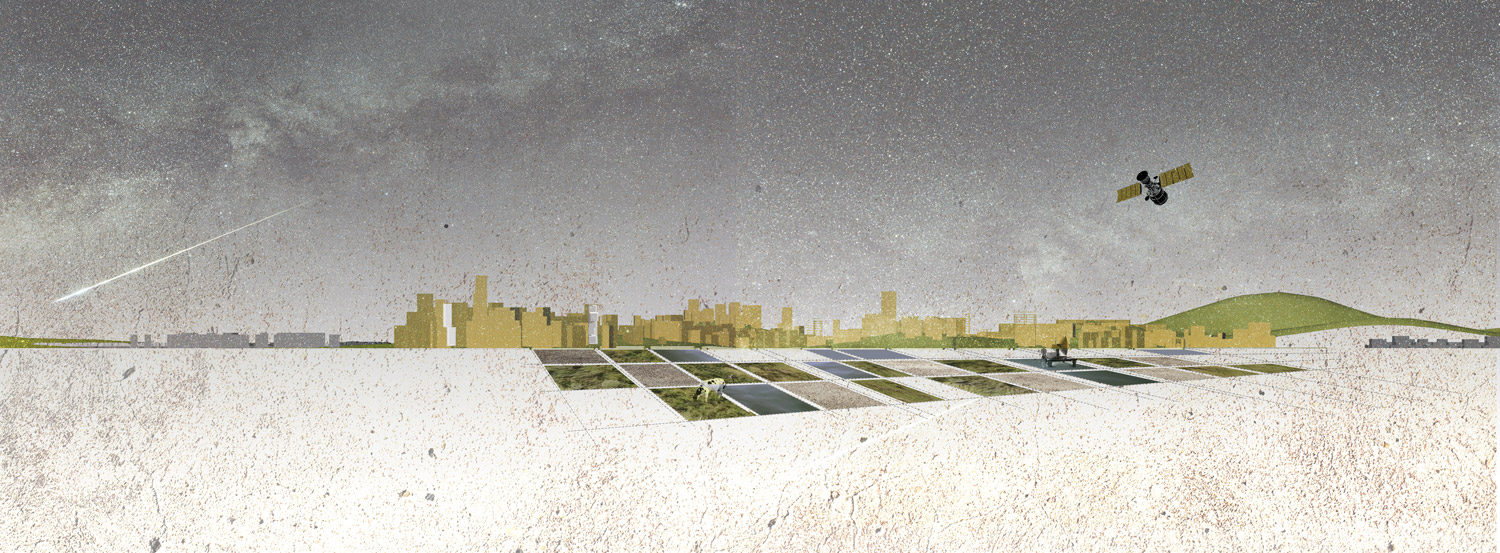

The geological conditions of Barra da Tijuca have been shaped by the region’s centuries old hydrological systems. Despite Lucio Costa’s vision of an ocean-side metropolitan center in which the landscape would figure prominently, a serious study of Barra’s geography, geology and hydrological networks was never conducted. One consequence has been largely unchecked growth that has ignored hydrology and natural water systems in an area marked by marshlands and lagoons. For the studio, hydrology became a primary lens through which to foreground the roles that large-scale natural systems must play. If this part of Rio de Janeiro is to grow into a more sustainable set of neighborhoods, such illumination must be met. One paradox, however, was that global climate change projections will impact this region in catastrophic ways: much of Barra da Tijuca will likely be underwater due to rising sea levels by the end of the century. This impending future bracketed all design studies; in many ways, the question of why this zone would be developed at all haunted the students. Best practices and global consciousness would suggest that Barra da Tijuca should be left un- or under-developed. However, market forces and political realities are such that the zone is being and will continue to be developed. That meant that the studio must play a role in illustrating how the area might grow in a slightly more productive way - but only for a limited time. Rather than attempt to engineer the region to survive 2 m [6.5 ft.] of sea level rise, students were encouraged to engage existing water systems in order to enable the area to continue as an urban center until the year 2050. 9 Understanding hydrological systems, therefore, meant mapping the presence of water, planning for flooded areas, and proposing an expanded network of canals, open spaces and floodable areas that could sponsor new forms of public space and architectural typologies.

“Housing.”

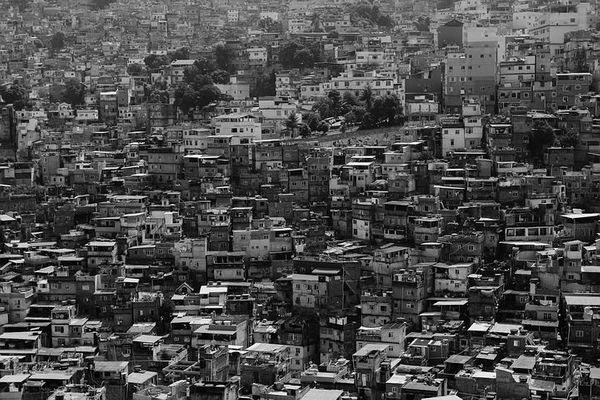

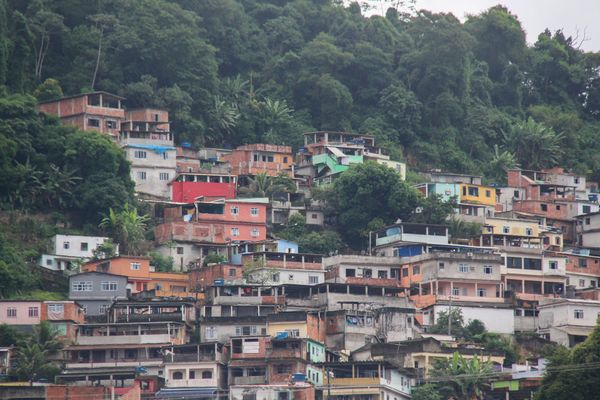

As a result of regional hydrological studies, micro strategies for architectural typologies and localized public spaces emerged that were intended to address Rio’s current need for affordable and adequate housing while simultaneously providing much needed public space. Geographically constrained, Rio de Janeiro’s urban development has spread to virtually every available undeveloped area. Informal settlements cover hillsides that were previously viewed as too expensive, difficult or unsafe for conventional development. Years of economic recession have depleted the middle classes - many of whom have chosen to leave their apartments in areas like Zona Sul for less expensive areas in the city’s many favelas . Those apartments in more expensive areas then became sources of income as familial residences have been rented out in order to augment declining household budgets. In some ways, the declining middle class has now contributed to the growth of informal settlements, or favelas , which have been established over time. Through self-organized processes, the favela has been built out of socio-economic and political need. These low-scale, high density, urban forms are interwoven with Brazil’s art, culture, and urban behavior. In many ways, the favela , while not romanticized, is a spatial expression of the cultural hybridity and innovation found in Brazil’s complex post-colonial history. Candidly, the students did not aim to “fix” the dilemmas that spawn favela neighborhoods. Instead, they sought to implement spatial opportunities for self-organizing systems that could populate and blend numerous scales of public space and architectural forms while attempting to provide additional options for urban living.

The combination of limited land for new development, declining economic environments and the explosion of informal neighborhoods presents the city with significant challenges: how and where to grow and how to integrate affordable housing within larger development patterns that are typically dominated by high end, luxury apartments. For the students, housing came to represent development generally - in this sense, the term housing encompassed forms of architectural and urban typologies that carried various economic elements: mixed-income housing, spaces for work and play, infrastructure such as cultural facilities, and new forms of public space in which water played central roles. Architectural typologies drawn from Brazilian Modernism exploited piloti while the garden city visions of mid-century Modernism became multi-programmed infrastructural landforms. In this sense, the cultural legacies of Brazilian Modernism - with their deep connection to notions of national identity and a utopian promise - influenced the students (both North American and Brazilian) in unexpected but understandable ways.

“Transportation.”

Transportation became the lens through which to view threads of movement that could weave together the proposed diverse built and ecological networks in Barra da Tijuca with those that currently exist. The students did not limit transportation to roadways; both roadways and hydrological systems were viewed as regional networks that could combine the movement of both people, animal life and water. The two systems were viewed as tandem elements linking the coast to the hillsides, concentrations of development to agrarian productivity, and housing and development with natural and recreational spaces. For example, using this design strategy, students performed careful studies of “informal” agricultural spaces found in Rio often within easements, left-over open spaces, or other forms of space lacking clear ownership boundaries. This search provided clues and contextual relationships, patterns of form, and opportunities for the integration of open space, programmatic use and much needed utilities. A wide range of outcomes from this search included: existing canal networks that produced formal agricultural activity; informal (and illegal) agricultural fields integrated into power utility right of ways; and small-town networks of urban form all characterize this area. The diversity of productive and performative landscapes makes this region of the city fertile ground for potentially innovative agriculturally-based industries. These speculative forms of engagement promoted landscape as a productive tool for generating patterns and behaviors of urbanization that both addressed economic needs (agriculture and employment) and programmed spaces that could potentially incorporate water in productive ways. Rather than importing idealized notions of community gardens or vertical farming, for example, the agricultural operations found across Rio and Zona Oeste served as a catalyst for integrative networked systems involving transportation, water, open space, and more environmentally sensitive hybrid urban forms.

Hydrological Layers.

Linhas de Rio: Fragmented Urbanization in plan.

Agricultural typological diagrams across Rio.

By diagnosing and documenting hydrological, housing and transportation networks, frameworks for future ecologically-driven interventions could be explored. Using these thematic lenses to research Barra da Tijuca’s landscape in concert with a carefully developed set of urban DNA samples, students then speculated upon potential interventions. Their quest became one to reconcile the contrasts between the utopian visions of Brazilian Modernism and built reality of gated vertical suburbs or the contrasts between sensitive landscape networks and destructive development practices. Purposefully, students explored strategies and design frameworks rooted in combinatory, ecological and cultural modes of urbanization. 10

REFLECTIONS

While Centro Metropolitano has an historic legacy tied to icons of Brazilian Modernism, its relatively recent development (limited to the site’s southern edges) represents common denominator commercial construction. In the years between Costa’s proposal for Barra da Tijuca and the 1990s real estate boom - fueled by mega-event driven infrastructure improvements - littl e growth took place in or around this site (a noteworthy exception is both informal and formal low-income housing development). However, much of the site was undeveloped. As a result of the favela removal and relocation policies of the previous military regime in the northern edges of Centro Metropolitano, public housing districts were established in the 1970s and 1980s. For example, the infamous Cidade de Dios borders the north-western edges of the Centro Metropolitano site. This contrast between formalized relocation of previously informal settlements and the grand visions of Lucio Costa for a high density commercial and governmental district provided a spark for design considerations. The apparent complexity of these design movements held the promise of potential resolutions to the challenges of radically dense environments and expanded scales of development in each of their case study sites.

The geographic, economic and cultural conditions of Barra da Tijuca and Centro Metropolitano contribute to the poly-nucleated urban fabric of Zona Oeste overall. In fact, Barra da Tijuca represents a large ex-urban zone still isolated by geography and only loosely connected to the city by weak transportation networks. These disparate urban conditions can be found in microcosm in the favelas , artificial grounds, and hydrological features that are distributed across a landscape that includes lagoas , protected habitats, and concentrated pockets of urbanization. The combination of topography, hydrology, regional networks, and unpredictable market forces all contribute to a fragmented landscape that has resulted in pockets of highly privatized and isolated nodes. This failure to produce contiguous urban space and an apparent lack of hydrological management became a starting point for many student conversations regarding the city’s future. By pairing the consequences of urban fragmentation with connective ecological and infrastructural strategies, the students sought a model of “productive fragmentation.” Highly concentrated developments, such as Centro Metropolitano, were imagined as concentrations of resilient development linked through open space strategies involving regional hydrological networks, canals and floodable open spaces aimed at mitigating the initial stages of rising sea levels.

View of proposed development as planned demolition, Centro Metropolitano.

One danger of this approach was that it may inadvertently resist the questions raised by environmental change and contemporary patterns of failed urban infrastructure; in other words, by seeking to perpetuate development (albeit in differing ways), student proposals were unable to fundamentally fend against a warming climate. But, and most importantly, questions of urban consequences of growth in places like Barra da Tijuca remain valuable. Therefore, and despite their limitations, the student proposals did help illuminate challenges to conventional urban development and enable a wider range of meanings to enter into conversations of environment and urbanization.

Various techniques emerged over the three years that helped students gain a foothold in order to act and focus attention on the hybrid, and often varied, characteristics of local places that broaden understandings of authenticity and urbanity as well. For example, the high modern practice of placing buildings on pilotis , which can be found in both Europe and Latin America, presented evidence of two interpretations: a post-colonial translation of European Modernism (an authentic local interpretation), and an outcome that produced vernacular variations informed by architectural forms and socio-spatial zones of influence. In this sense, hybridity is an authentic expression and it can be found in both physical and social space. Studies into local neighborhood DNA samples provided our students with a point of entry into a broader discussion. Students found themselves focused upon design strategies that could be sensitive to place but open-ended enough to allow transformation through future adaptive practices (see Figure 1).

The DNA studies went beyond conventional precedent analysis and maintained a focus upon socio-spatial conditions. By documenting, analyzing, and cataloging samples taken throughout the city of Rio de Janeiro, students created a spatial vocabulary inherently about micro-urban conditions found in a range of unique local physical settings. These DNA, then, represented a set of codes that illustrated social and spatial interactions in site-specific areas of the city. In the process, simple understandings of mixed use development, for example, were quickly challenged; social spaces in Rio (as they do throughout Latin America) represent a range of “mixed-up uses” that go beyond the simple organization of spatial programs that can be found in most conventional North American urban planning. Additionally, informality in both social and physical form presented new ways of understanding the inter-dependent relationships between people and places. These typologies represent varying degrees of socio-spatial behaviors - of people, of place-based occupation and transformation; and of physical form, hybrid structures and informal patterns. The work of the students illustrates states of possibility, or rather speculations, of how Zona Oeste “could be,” not how it “will be.”

As a result of the complex urban networks and the equally complex challenges presented by Barra da Tijuca’s ecological contexts, design strategies emerged that enabled students to build upon local fabric. Students borrowed strategies from one theoretical camp to augment those found in another: pedestrian scaled increments were layered over mega-scaled urban blocks and then infused with ecologically driven forms of infrastructure. The simultaneous scales allowed for new public spaces, distributed resources through regional networks, and provided concentrations of dynamic housing typologies. Following general transit oriented development models in the west, the most intensely programmed districts were often located in areas near transportation hubs while large areas of each site were often dedicated to new forms of low-density but high performance spatial uses (innovative agricultural industries, landforms aimed to provide both recreational and ecological management spaces). Other strategies involved the use of complex landscape and ecological systems aimed at stitching together each of the three case study sites through regionally scaled three-dimensional land and water-form frameworks. Still other strategies emerged that attempted to address historic legacies through the use of transformed typologies that were rooted in cultural traditions, which aimed to root themselves in a sense of local identity while also extending those identities to include future transformations.

In a sense, the students took a combinatory approach to urban design in an effort to develop a tool set appropriate to their sites (the local) and their professions (the global). 11 The two-fold technique that the sampling represented provided a knowledge of cultural place, ecological and urban conditions with an eye towards an integrative approach to urban design interventions. Students used these DNA samples as a way of understanding and designing micro-urbanisms that could scale up and combine to address a macro set of metropolitan or ecological conditions. The ever-present wetlands and mangroves in the region could enable a healthier, safer environment. The blending of form along with the incorporation of wildlife, water-based agriculture, and protected wetlands fostered innovative forms of public spaces in the students’ work while remaining rooted in local character of place. Water represented one of the major challenges of the area both now and in the future, which were demonstrated by urban flooding, sinking soils, sensitive ecosystems of lagoons, marshes and tidal waterways in Barra. However, water was also an opportunity for the students; impending climatic changes forced a renewed emphasis upon ecology and the need to “design with nature.” 12 Water, therefore, became a basic ingredient for productively creating a new set of urban spaces. A vision of a naturally enhanced, porous, and locally fragmented yet regionally connected mode of urbanization operated through an ecological approach, across scales and time. These strategies focused on the impacts of climate change while acknowledging the obvious failures that development has wrought on fragile environmental systems.

While the work was developed within a series of three-year urban design workshops/studios, it parallels what Dana Cuff has called a “fourth phase” of urban design curricular models marking a “major shift in the conception of cities, but with a relatively coherent architectural aesthetic and a professional agenda rooted in design practice’s larger political economy.” 13 This essay illustrates design research in Rio de Janeiro focused on integrating systems of ecology and landscape through design processes focused upon urbanization in the face of climate change. Driven by typological and morphological investigations, the work offers responses to specific topographic and climatic contexts that demonstrate new forms of urbanism. Illustrated through speculative programs ranging from the establishment of research facilities, affordable housing, and cultural centers, to agriculture, eco-tourism, and protected habitats - the pedagogical research integrates opportunities for the use of water systems and management as an urban design agenda. Rather than defending against storm surge, landslides, and rising sea levels, we sought speculative models rooted in the DNA of Rio de Janeiro and embrace strategies for resilient coastal regions across the globe.

View of Terra Que Desce: A new use for Costa’s grid, Centro Metropolitano.

Peter Hogarth, “Preliminary Analysis of Acceleration of Sea Level Rise through the Twentieth Century Using Extended Tide Gauge Data Sets (August 2014),” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 119 (November 2014): 7645-7659, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2014JC009976 .

Fernando Lara, “One Katrina Every Year: The Challenge of Flooding in Tropical Cities,” in 98 th ACSA Annual Meeting Proceedings: Rebuilding , eds. Bruce Goodwin and Judith Kinnard (Washington DC: Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, 2010), 221-226.

Gilberto T. M. Dias and Björn Kjerfve, “Barrier and Beach Ridge Systems of the Rio De Janeiro Coast” in Geology and Geomorphology of Holocene Coastal Barriers of Brazil , eds. Sérgio R. Dillenburg and Patrick A. Hesp (Berlin: Springer, 2009): 242, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-44771-9_7 .

Dieter Muehe, “Brazilian Coastal Vulnerability to Climate Change,” Pan-American Journal of Aquatic Sciences 5, no. 2 (2010): 173-83.

Lars Lerup, “Stim & Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis,” Assemblage 25 (December 1994): 83-101, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3171389 .

Lucio Costa, “Plano-Piloto para a Urbanizacao da Baixada Compreendida Entre a Barra da Tijuca, o Pontal de Sernambetiba e Jacarepagua,” in Arquitextos 10, no. 116 (January 2010), http://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/10.116/3375 . First published in 1969 by Agencia Jornalistica Image (Rio de Janeiro).

Ana Cristina Gomes and Vicente del Rio, “A Outra Urbanidade: A Construcao da Cidade Pos-Moderna e o Caso da Barra da Tijuca,” in Arcquitectura: Pesquisa y Projecto , ed. Vicente del Rio (Rio de Janeiro: Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 1998), 108.

Building Futures and the Institution of Civil Engineers, Facing up to Rising Sea Levels: Retreat? Defend? Attack? (London: The Royal Institute of British Architects, 2009), http://www.buildingfutures.org.uk/assets/downloads/Facing_Up_To_Rising_S... . By borrowing from the RIBA’s studies in the UK, we sought design strategies drawn from and that often combined ideas of defense, attack and retreat.

For example, students were asked to read: Thom Mayne and Stan Allen, Combinatory Urbanism: The Complex Behavior of Collective Form (Culver City CA, USA: Stray Dog Café, 2011); students were also encouraged to examine the work of leading “landscape urbanists” such as Stan Allen and James Corner as well as innovative interdisciplinary design firms such as Susannah C. Drake’s DLANDstudio that integrate (among other things) ecological strategies into their work.

Ian L. McHarg, Design With Nature (Garden City NY, USA: American Museum of Natural History Press, 1969).

Dana Cuff, “Urban Design: The City as Project,” in Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America , eds. Rebecca Williamson and Joan Ockman (Washington DC and Cambridge MA, USA: Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture and MIT Press, 2012), 409.

Figure 1: diagrams by Shuxin Lin, Alyssa Nelson and Jenna Young.

Figure 2: map by Huck Broyles.

Figure 3: drawing based upon (top) Lucio Costa’s conceptual sketches and (below) student conceptual sectional strategy; redrawn by Nicole Avitabile.

Figure 4: photo by José Gamez.

Figures 5 and 9: drawings by May Khalife and Nitya Kolli.

Figure 6: drawing by Jingyao Cheng, Yu Huan, Jas Warren and Ginny Young.

Figure 7: diagrams by Huck Broyles, Bria Prioleau and Jess Yester.

Figure 8: rendering by Zhang Xunxun, Aline Nascimento and Monica Whitmire.

Professor in Residence, Department of Architecture, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Dean, Facoltà di Architettura, Sapienza Università di Roma, Rome

Professor of Architecture, College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Founder of Archi-Tectonics, Miller Professor and Chair of Architecture at Stuart Weitzman School of Design

Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture & Built Environment, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Professor, SCI-Arc, Los Angeles CA, USA

Professor of Urbanism, Dipartimento di Architettura, Universita' degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Naples, Italy

Professor of Urban Design and Planning, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology, GSD, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Dean, School of Architecture, Princeton University, Princeton NJ, USA

Professor, The Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, London, UK

Professor of Architecture, Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, South Africa

Dean, School of Architecture, Syracuse University, Syracuse NY, USA

Hon FRIBA, Hon COAM, Senior Advisor for The OBEL Award

Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Chiao-Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan

Dean, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA

Deputy Dean, College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Urbanisation Case Study: Rio de Janeiro

The growth of rio de janeiro.

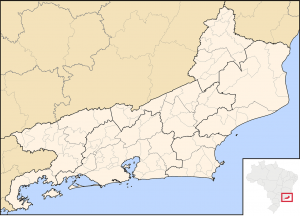

Rio de Janeiro is a major city located in the south-east of Brazil.

Why is Rio de Janeiro important?

- Rio de Janeiro is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Rio de Janeiro hosted the 2016 Olympics and was one of the host cities during the 2014 Football World Cup.

- Rio de Janeiro is a port, industrial centre and centre for banking.

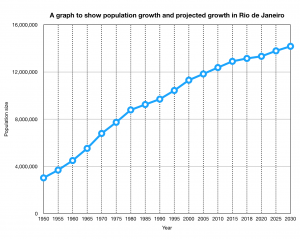

Why has Rio grown?

- Rio has grown due to natural increase and migration.

- Migrants move to Rio from other places in Brazil, such as the Amazon Basin, as well as from other countries in South America, such as Argentina and Bolivia.

- Portugal was the colonial power that historically controlled Brazil. Because the same language is spoken in both countries, some Portuguese citizens may move to Brazil.

Social opportunities from Rio's growth

- Young people have the chance to go to school and university and medical services can visit people at home to treat 20 different diseases.

- 95% of the population have access to mains water.

- Power supplies have been improved as the city has grown.

Economic opportunities from Rio's growth

- People can get jobs in Rio’s industries such as oil refining, building, shopping and tourism.

- 6% of all employment in Brazil is in Rio.

Challenges of Rio's Growth

As with all urbanisation cases, the rapid growth of a city creates many opportunities, but there will also be growing pains.

Social challenge - favelas

- Slums in Rio are known as favelas. Rocinha is the largest favela in Rio.

Social challenge - water, sanitation & energy

- 50% of homes in Rio’s favelas have no sewerage.

- 30% of homes in Rio’s favelas have no electricity.

- 12% of homes in Rio’s favelas have no running water.

Social challenge - access to services

- Only 50% of children in Rio stay in school past 14.

- Infant mortality in favelas can be as high as 50 per 1,000 children.

Social challenge - unemployment and crime

- Unemployment rates in favelas are over 20%

- The murder rate can be up to 20 per 1,000 people.

Environmental challenges from Rio's growth

- There is no waste disposal service in the favelas, so rubbish piles up.

- Air pollution caused by fumes from cars and factories causes around 5,000 deaths a year.

- High numbers of cars on the roads leads to severe traffic congestion.

1 The Challenge of Natural Hazards

1.1 Natural Hazards

1.1.1 Natural Hazards

1.1.2 Types of Natural Hazards

1.1.3 Factors Affecting Risk

1.1.4 People Affecting Risk

1.1.5 Ability to Cope With Natural Hazards

1.1.6 How Serious Are Natural Hazards?

1.1.7 End of Topic Test - Natural Hazards

1.1.8 Exam-Style Questions - Natural Hazards

1.2 Tectonic Hazards

1.2.1 The Earth's Layers

1.2.2 Tectonic Plates

1.2.3 The Earth's Tectonic Plates

1.2.4 Convection Currents

1.2.5 Plate Margins

1.2.6 Volcanoes

1.2.7 Volcano Eruptions

1.2.8 Effects of Volcanoes

1.2.9 Primary Effects of Volcanoes

1.2.10 Secondary Effects of Volcanoes

1.2.11 Responses to Volcanic Eruptions

1.2.12 Immediate Responses to Volcanoes

1.2.13 Long-Term Responses to Volcanoes

1.2.14 Earthquakes

1.2.15 Earthquakes at Different Plate Margins

1.2.16 What is an Earthquake?

1.2.17 Measuring Earthquakes

1.2.18 Immediate Responses to Earthquakes

1.2.19 Long-Term Responses to Earthquakes

1.2.20 Case Studies: The L'Aquila Earthquake

1.2.21 Case Studies: The Kashmir Earthquake

1.2.22 Earthquake Case Study: Chile 2010

1.2.23 Earthquake Case Study: Nepal 2015

1.2.24 Reducing the Impact of Tectonic Hazards

1.2.25 Protecting & Planning

1.2.26 Living with Tectonic Hazards 2

1.2.27 End of Topic Test - Tectonic Hazards

1.2.28 Exam-Style Questions - Tectonic Hazards

1.2.29 Tectonic Hazards - Statistical Skills

1.3 Weather Hazards

1.3.1 Winds & Pressure

1.3.2 The Global Atmospheric Circulation Model

1.3.3 Surface Winds

1.3.4 UK Weather Hazards

1.3.5 Changing Weather in the UK

1.3.6 Tropical Storms

1.3.7 Tropical Storm Causes

1.3.8 Features of Tropical Storms

1.3.9 The Structure of Tropical Storms

1.3.10 The Effect of Climate Change on Tropical Storms

1.3.11 The Effects of Tropical Storms

1.3.12 Responses to Tropical Storms

1.3.13 Reducing the Effects of Tropical Storms

1.3.14 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina

1.3.15 Tropical Storms Case Study: Haiyan

1.3.16 UK Weather Hazards Case Study: Somerset 2014

1.3.17 End of Topic Test - Weather Hazards

1.3.18 Exam-Style Questions - Weather Hazards

1.3.19 Weather Hazards - Statistical Skills

1.4 Climate Change

1.4.1 Climate Change

1.4.2 Evidence for Climate Change

1.4.3 Natural Causes of Climate Change

1.4.4 Human Causes of Climate Change

1.4.5 Effects of Climate Change on the Environment

1.4.6 Effects of Climate Change on People

1.4.7 Climate Change Mitigation Strategies

1.4.8 Adaptation to Climate Change

1.4.9 End of Topic Test - Climate Change

1.4.10 Exam-Style Questions - Climate Change

1.4.11 Climate Change - Statistical Skills

2 The Living World

2.1 Ecosystems

2.1.1 Ecosystems

2.1.2 Food Chains & Webs

2.1.3 Ecosystem Cascades

2.1.4 Global Ecosystems

2.1.5 Ecosystem Case Study: Freshwater Ponds

2.2 Tropical Rainforests

2.2.1 Tropical Rainforests

2.2.2 Interdependence of Tropical Rainforests

2.2.3 Adaptations of Plants to Rainforests

2.2.4 Adaptations of Animals to Rainforests

2.2.5 Biodiversity of Tropical Rainforests

2.2.6 Deforestation

2.2.7 Impacts of Deforestation

2.2.8 Case Study: Deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest

2.2.9 Why Protect Rainforests?

2.2.10 Sustainable Management of Rainforests

2.2.11 Case Study: Malaysian Rainforest

2.2.12 End of Topic Test - Tropical Rainforests

2.2.13 Exam-Style Questions - Tropical Rainforests

2.2.14 Deforestation - Statistical Skills

2.3 Hot Deserts

2.3.1 Hot Deserts

2.3.2 Interdependence in Hot Deserts

2.3.3 Adaptation of Plants to Hot Deserts

2.3.4 Adaptation of Animals to Hot Deserts

2.3.5 Biodiversity in Hot Deserts

2.3.6 Case Study: Sahara Desert

2.3.7 Desertification

2.3.8 Reducing the Risk of Desertification

2.3.9 Case Study: Thar Desert

2.3.10 End of Topic Test - Hot Deserts

2.3.11 Exam-Style Questions - Hot Deserts

2.4 Tundra & Polar Environments

2.4.1 Overview of Cold Environments

2.4.2 Interdependence of Cold Environments

2.4.3 Adaptations of Plants to Cold Environments

2.4.4 Adaptations of Animals to Cold Environments

2.4.5 Biodiversity in Cold Environments

2.4.6 Case Study: Alaska

2.4.7 Sustainable Management

2.4.8 Case Study: Svalbard

2.4.9 End of Topic Test - Tundra & Polar Environments

2.4.10 Exam-Style Questions - Cold Environments

3 Physical Landscapes in the UK

3.1 The UK Physical Landscape

3.1.1 The UK Physical Landscape

3.1.2 Examples of the UK's Landscape

3.2 Coastal Landscapes in the UK

3.2.1 Types of Wave

3.2.2 Weathering

3.2.3 Mass Movement

3.2.4 Processes of Erosion

3.2.5 Wave-Cut Platforms

3.2.6 Headlands & Bays

3.2.7 Caves, Arches & Stacks

3.2.8 Longshore Drift

3.2.9 Sediment Transport

3.2.10 Deposition

3.2.11 Spits, Bars & Sand Dunes

3.2.12 Coastal Management - Hard Engineering

3.2.13 Coastal Management - Soft Engineering

3.2.14 Case Study: Landforms on the Dorset Coast

3.2.15 Coastal Management - Managed Retreat

3.2.16 Coastal Management Case Study - Holderness

3.2.17 Coastal Management Case Study: Swanage

3.2.18 Coastal Management Case Study - Lyme Regis

3.2.19 End of Topic Test - Coastal Landscapes in the UK

3.2.20 Exam-Style Questions - Coasts

3.3 River Landscapes in the UK

3.3.1 The Long Profile of a River

3.3.2 The Cross Profile of a River

3.3.3 Vertical & Lateral Erosion

3.3.4 River Valley Case Study - River Tees

3.3.5 Processes of Erosion

3.3.6 Sediment Transport

3.3.7 River Deposition

3.3.8 Waterfalls & Gorges

3.3.9 Interlocking Spurs

3.3.10 Meanders

3.3.11 Oxbow Lakes

3.3.12 Floodplains

3.3.13 Levees

3.3.14 Estuaries

3.3.15 Case Study: The River Clyde

3.3.16 River Management

3.3.17 Hydrographs

3.3.18 Flood Defences - Hard Engineering

3.3.19 Flood Defences - Soft Engineering

3.3.20 River Management Case Study - Boscastle

3.3.21 River Management Case Study - Banbury

3.3.22 End of Topic Test - River Landscapes in the UK

3.3.23 Exam-Style Questions - Rivers

3.4 Glacial Landscapes in the UK

3.4.1 The UK in the Last Ice Age

3.4.2 Glacial Processes

3.4.3 Glacial Landforms Caused by Erosion

3.4.4 Tarns, Corries, Glacial Troughs & Truncated Spurs

3.4.5 Types of Moraine

3.4.6 Drumlins & Erratics

3.4.7 Snowdonia

3.4.8 Land Use in Glaciated Areas

3.4.9 Conflicts in Glacial Landscapes

3.4.10 Tourism in Glacial Landscapes

3.4.11 Coping with Tourism Impacts in Glacial Landscapes

3.4.12 Case Study - Lake District

3.4.13 End of Topic Test - Glacial Landscapes in the UK

3.4.14 Exam-Style Questions - Glacial Landscapes

4 Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1 Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.1 Urbanisation

4.1.2 Factors Causing Urbanisation

4.1.3 Megacities

4.1.4 Urbanisation Case Study: Lagos

4.1.5 Urbanisation Case Study: Rio de Janeiro

4.1.6 UK Cities

4.1.7 Case Study: Urban Regen Projects - Manchester

4.1.8 Case Study: Urban Change in Liverpool

4.1.9 Case Study: Urban Change in Bristol

4.1.10 Sustainable Urban Life

4.1.11 Reducing Traffic Congestion

4.1.12 End of Topic Test - Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.13 Exam-Style Questions - Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.14 Urban Issues -Statistical Skills

5 The Changing Economic World

5.1 The Changing Economic World

5.1.1 Measuring Development

5.1.2 Limitations of Developing Measures

5.1.3 Classifying Countries Based on Wealth

5.1.4 The Demographic Transition Model

5.1.5 Stages of the Demographic Transition Model

5.1.6 Physical Causes of Uneven Development

5.1.7 Historical Causes of Uneven Development

5.1.8 Economic Causes of Uneven Development

5.1.9 Consequences of Uneven Development

5.1.10 How Can We Reduce the Global Development Gap?

5.1.11 Case Study: Tourism in Kenya

5.1.12 Case Study: Tourism in Jamaica

5.1.13 Case Study: Economic Development in India

5.1.14 Case Study: Aid & Development in India

5.1.15 Case Study: Economic Development in Nigeria

5.1.16 Case Study: Aid & Development in Nigeria

5.1.17 End of Topic Test - The Changing Economic World

5.1.18 Exam-Style Questions - The Changing Economic World

5.1.19 Changing Economic World - Statistical Skills

5.2 Economic Development in the UK

5.2.1 Causes of Economic Change in the UK

5.2.2 The UK's Post-Industrial Economy

5.2.3 The Impacts of UK Industry on the Environment

5.2.4 Change in the UK's Rural Areas

5.2.5 Transport in the UK

5.2.6 The North-South Divide

5.2.7 Regional Differences in the UK

5.2.8 The UK's Links to the World

6 The Challenge of Resource Management

6.1 Resource Management

6.1.1 Global Distribution of Resources

6.1.2 Uneven Distribution of Resources

6.1.3 Food in the UK

6.1.4 Agribusiness

6.1.5 Demand for Water in the UK

6.1.6 Water Pollution in the UK

6.1.7 Matching Supply & Demand of Water in the UK

6.1.8 The UK's Energy Mix

6.1.9 Issues with Sources of Energy

6.1.10 Resource Management - Statistical Skills

6.2.1 Areas of Food Surplus & Food Deficit

6.2.2 Increasing Food Consumption

6.2.3 Food Supply & Food Insecurity

6.2.4 Impacts of Food Insecurity

6.2.5 Increasing Food Supply

6.2.6 Case Study: Thanet Earth

6.2.7 Creating a Sustainable Food Supply

6.2.8 Case Study: Agroforestry in Mali

6.2.9 End of Topic Test - Food

6.2.10 Exam-Style Questions - Food

6.2.11 Food - Statistical Skills

6.3.1 Water Surplus & Water Deficit

6.3.2 Increasing Water Consumption

6.3.3 What Affects the Availability of Water?

6.3.4 Impacts of Water Insecurity

6.3.5 Increasing Water Supplies

6.3.6 Case Study: Water Transfer in China

6.3.7 Sustainable Water Supply

6.3.8 Case Study: Kenya's Sand Dams

6.3.9 Case Study: Lesotho Highland Water Project

6.3.10 Case Study: Wakel River Basin Project

6.3.11 Exam-Style Questions - Water

6.3.12 Water - Statistical Skills

6.4.1 Global Demand for Energy

6.4.2 Increasing Energy Consumption

6.4.3 Factors Affecting Energy Supply

6.4.4 Impacts of Energy Insecurity

6.4.5 Increasing Energy Supply - Solar

6.4.6 Increasing Energy Supply - Water

6.4.7 Increasing Energy Supply - Wind

6.4.8 Increasing Energy Supply - Nuclear

6.4.9 Increasing Energy Supply - Fossil Fuels

6.4.10 Carbon Footprints

6.4.11 Energy Conservation

6.4.12 Case Study: Rice Husks in Bihar

6.4.13 Exam-Style Questions - Energy

6.4.14 Energy - Statistical Skills

Jump to other topics

Unlock your full potential with GoStudent tutoring

Affordable 1:1 tutoring from the comfort of your home

Tutors are matched to your specific learning needs

30+ school subjects covered

Urbanisation Case Study: Lagos

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2024

When urban poverty becomes a tourist attraction: a systematic review of slum tourism research

- Tianhan Gui ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6069-3046 1 &

- Wei Zhong 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1178 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

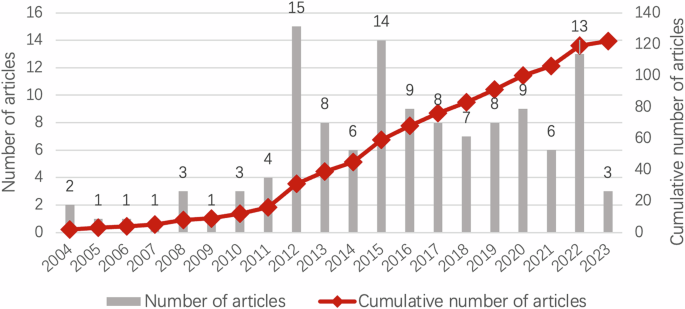

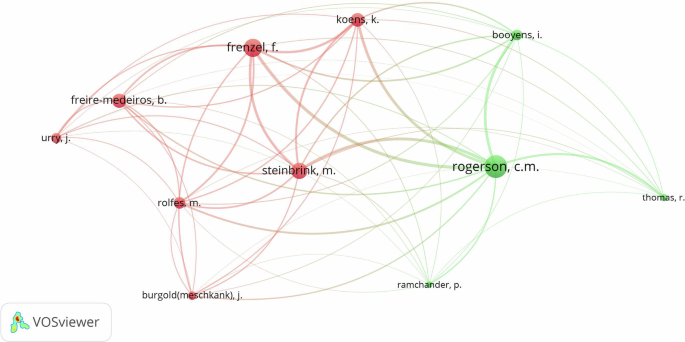

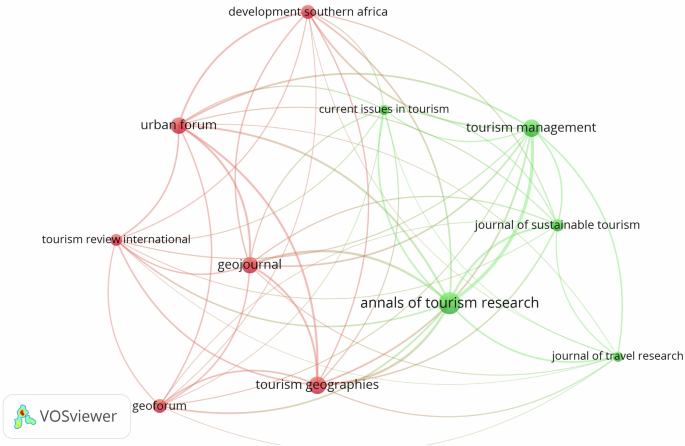

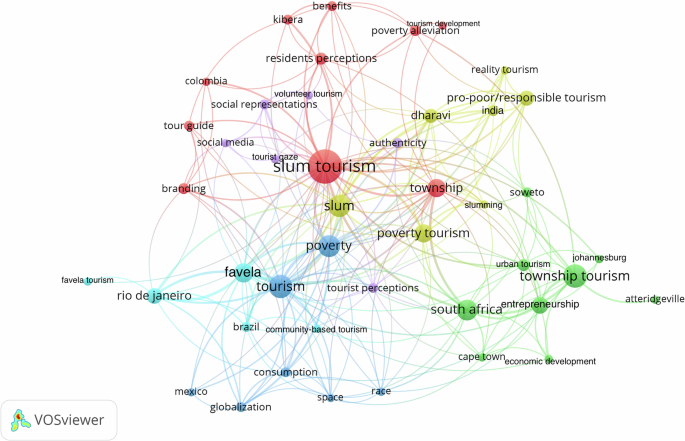

- Business and management

Over the last two decades, the phenomenon of “slum tourism” and its academic exploration have seen considerable growth. This study presents a systematic literature review of 122 peer-reviewed journal articles, employing a combined approach of bibliometric and content analysis. Our review highlights prominent authors and journals in this domain, revealing that the most cited journals usually focus on tourism studies or geography/urban studies. This reflects a confluence of travel motivations and urban complexities within slum tourism. Through keyword co-occurrence analysis, we identified three primary research areas: the touristic transformation of urban informal settlements, the depiction and valorization of urban poverty, and the socio-economic impacts of slum tourism. This study not only maps the current landscape of research in this area but also identifies existing gaps. It suggests that the economic, social, and cultural effects of slum tourism are areas that require more in-depth investigation in future research endeavors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research

Bibliometric analysis of trends in COVID-19 and tourism

A ten-year review analysis of the impact of digitization on tourism development (2012–2022)

Introduction.

“Slums” are defined by UN-Habitat ( 2006 ) as underdeveloped urban areas lacking in a durable housing, adequate living space, safe water access, sanitation, and tenure security. Emerging from urban growth disparities, these informal settlements have proliferated since the latter half of the 20th century, especially in the Global South’s cities. Despite progress in urban planning and poverty reduction, UN-Habitat ( 2020 ) reports that over a billion people, with 80% in developing regions, still live in such conditions.

Slums undeniably “represent one of the most enduring faces of poverty, inequality, exclusion and deprivation” (UN-Habitat, 2020 , p. 25), necessitating policy intervention. However, the term “slum” is controversial among scholars as it often carries negative connotations, conflating poor housing conditions with the identities of residents (Gilbert, 2007 ). Beyond poverty and disease, it suggests crime and immorality, contributing to a narrative of fear and fascination (Davis, 2006 ; Mayne, 2017 ).

Recent decades have seen a surge in “slum tours” in the Global South, attracting tourists from the affluent North. Driven by complex motives that “consist of a mix of adventurous inquiry and humanitarian ambitions” (Dürr, 2012b , p. 707), tourists from the affluent North desire to glimpse “the other side of the world” (Steinbrink, 2012 , p. 232). This trend has turned guided tours in informal settlements into a booming business in cities like Mumbai, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, and Nairobi, drawing approximately one million tourists annually (Frenzel, 2016 ).

Modern slum tourism has deep historical roots, originating as “slumming” in Victorian England and early 20th-century America. Rapid urbanization in cities like London and New York created neglected areas, which, to middle and upper-class observers, represented a mysterious and chaotic “other world” (Steinbrink, 2012 ). This perception of danger and uncivilization paradoxically attracted bourgeois curiosity (Frenzel et al. 2015 ).

By the late 1970s, with the surge in international tourism, this localized “slumming” transformed into a global phenomenon. Affluent residents from the Global North began exploring underprivileged urban pockets in the Global South, making these areas tourism hotspots (Freire-Medeiros, 2009 ; Iqani, 2016 ). This trend marked the beginning of modern slum tourism, a practice that took a significant turn in the 1990s in South Africa. Initially focusing on anti-apartheid landmarks in townships like Soweto, Johannesburg (Steinbrink, 2012 ), these tours diversified to other cities, including Rio de Janeiro, Mumbai, and Manila (Frenzel et al. 2015 ). The once sporadic visits to informal settlements have now metamorphosed into well-orchestrated tours, often recommended by travel guidebooks. Today’s travelers can dine at local eateries, visit schools, interact with residents, or even step inside their homes (Frenzel, 2017 ; Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ). The industry has professionalized, with cities in the Global South attracting tourists mainly from the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, and Scandinavia (Frenzel, 2012 ; Frenzel and Blakeman, 2015 ; Steinbrink, 2012 ).

The burgeoning interest in slum tourism has sparked significant scholarly discourse, particularly in the new millennium. Research in this realm predominantly orbits around the ethical implications of such tourism, its role in mitigating poverty, and the duties of governing bodies in these scenarios. Slum tourism research encompasses various disciplines, including urban studies, tourism and hospitality, and human geography, with a significant proliferation of publications in recent years.

The surge in research has also led to several evaluative studies scrutinizing the breadth and depth of the subject. Frenzel’s ( 2013 ) thematic review, for instance, probed the nexus between slum tourism and poverty alleviation. Given that most slum tours proclaim poverty alleviation as their core intent, Frenzel’s inquiry into the intersection of this mission with tourism was insightful. He also championed the need for a rigorous exploration of the multifaceted valorization of poverty within tourism dynamics. A more expansive review by Frenzel et al. ( 2015 ) delved into various research focuses like the evolution of slum tourism, tourist experiences, operational aspects, economic implications, and so on. Their assessment underscored existing research voids, emphasizing the necessity for more nuanced, comparative studies. Tzanelli ( 2018 ) examined the socio-cultural and political drivers behind tourists’ inclinations towards informal settlements, critically analyzing the epistemological frameworks employed by scholars.

While these reviews have significantly sketched the contours of the discipline, many leaned heavily on conventional literature review techniques—predicated on selected, and at times, circumscribed resources (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008 ). Such manual methodologies, albeit insightful, are prone to biases “during the identification, selection, and synthesis of included studies” (Haddaway et al. 2015 , p. 1956). A systematic literature review, which adheres to rigorous protocols and curtails subjective inclinations, would be more enriching. Such a methodological shift not only offers a panoramic view of pivotal research arguments and deliberations but also illuminates evolving trends and perspectives. The surge in slum tourism literature recently underscores its dynamic nature, necessitating a renewed scrutiny of nascent discussions eluding preceding reviews.

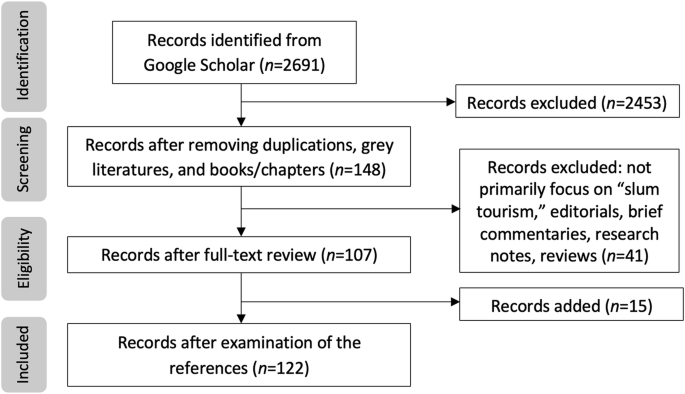

Addressing this research exigency, our current endeavor undertakes a comprehensive examination of a gamut of articles illuminating diverse research angles on slum tourism. Employing both bibliometric and qualitative content analysis techniques, our study dissects 122 journal articles published over the past twenty years. We endeavor to spotlight seminal authors and journals, delineate prevailing themes in slum tourism studies, and carve out prospective trajectories for forthcoming research endeavors.

Methodology

Search process and sample selection.