An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC8276192.1 ; 2021 Jan 12

- ➤ PMC8276192.2; 2021 Jul 1

Current market rates for scholarly publishing services

Alexander grossmann.

1 Fakultät Informatik und Medien, HTWK Leipzig, Leipzig, Sachsen, 04277, Germany

Björn Brembs

2 Institut für Zoologie - Neurogenetik, Universität Regensburg, Regensburg, Bavaria, 93053, Germany

Associated Data

Underlying data.

Figshare: Journal_Production_Cost_010519.xlsx. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8118197.v2 60 .

This project contains the data used to calculate production costs for articles.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Version Changes

Revised. amendments from version 1.

In this version, we have used the feedback from the reviewers to improve the description of our methods and different wordings throughout the text. Specifically, we have described the publishing process in more generic terms and described the similarities and differences between the different publishing scenarios in more detail. We also updated the spreadsheet containing our raw data to reflect these new wordings.

Peer Review Summary

For decades, the supra-inflation increase of subscription prices for scholarly journals has concerned scholarly institutions. After years of fruitless efforts to solve this “serials crisis”, open access has been proposed as the latest potential solution. However, also the prices for open access publishing are high and are rising well beyond inflation. What has been missing from the public discussion so far is a quantitative approach to determine the actual costs of efficiently publishing a scholarly article using state-of-the-art technologies, such that informed decisions can be made as to appropriate price levels. Here we provide a granular, step-by-step calculation of the costs associated with publishing primary research articles, from submission, through peer-review, to publication, indexing and archiving. We find that these costs range from less than US$200 per article in modern, large scale publishing platforms using post-publication peer-review, to about US$1,000 per article in prestigious journals with rejection rates exceeding 90%. The publication costs for a representative scholarly article today come to lie at around US$400. These results appear uncontroversial as they not only match previous data using different methodologies, but also conform to the costs that many publishers have openly or privately shared. We discuss the numerous additional non-publication items that make up the difference between these publication costs and final price at the more expensive, legacy publishers.

Introduction

The affordability problem of scholarly publishing, i.e., the supra-inflationary price increases with stagnating library budgets, has been a hot topic for more than three decades (see, e.g., 1 – 8 ). In recent years, perhaps precipitated by some so-called ‘gold’ open access (OA) journals requiring payments in the form of article-processing charges (APCs; fees for authors or their institutions upon acceptance for publishing an article and making it openly available), the average cost of an article has emerged as a useful measure with which to compare different business models (but see 9 for a critique). However, most authors refer to the prices charged by the publisher, not the actual cost to the publisher (e.g., 10 – 13 ). One consequence of this mis-attribution is a potential overestimation of the actual costs of scholarly publishing due to the inclusion of the business models and pricing strategies of publishers into the calculation. To close this gap, here we provide a bottom-up calculation of the cost of efforts and services which are required to achieve a certain service level in order to publish an academic journal article. These calculations are analogous to what a new publisher would have to calculate before entering the publishing market. We compare our cost calculations with the current pricing schemes of publishers.

In this article, we assume the role of a newcomer to the academic publishing market and list the various steps and procedures for a representative publishing workflow according to current industry standards. Each step incurs a cost which can be determined by analyzing the market rates for each service or procedure. These costs comprise the direct costs. We also add several indirect (or fixed) cost items which do not accrue on a per article basis. The final per-article costs are then specified as a range depending on the number of articles published and the service level desired. These ranges denote current market rates at which customers can obtain publishing services.

Methodology

To arrive at a meaningful figure denoting how much the publication of an article costs on average, it is necessary to arrive at the exact cost for each step in the processing workflow of a manuscript being submitted for publication. These direct or variable costs then have to be combined with the indirect or fixed costs of operating a publishing enterprise, such as staff costs, real estate, insurance and energy costs, etc. The former requires granular insight and expertise about the different service levels for the entire publishing workflow. The latter is commonly calculated as staff overhead. In this work, we have therefore calculated the cost for each step in the standard publication workflow under consideration of both fixed and variable costs. Both external and internal expenses have been taken into account as well as overhead costs to cover fixed non-direct company costs of the publishing venture.

Direct or variable costs

There are three main areas in which production steps have to be considered: content acquisition, content preparation (production) and content dissemination/archiving. Importantly, ‘content acquisition’ does not imply active acquisition of authors and/or manuscripts.

- a. Online submission system

- b. Searching and assigning reviewers

- c. Communication with reviewers

- d. Communication with authors

- e. Handling of re-submission process

- f. Plagiarism check

- g. Similarity Check (CrossRef)

- h. DOI for article (CrossRef)

- i. DOI for 2 or more reviews (CrossRef)

- j. APC collection

- a. Manuscript tracking system

- b. Production system check-in

- c. Technical checking of manuscript

- d. Copyediting

- e. Typesetting

- f. Formatting figures/graphs/tables

- g. Altmetric badge

- h. XML and metadata preparation

- i. Handling author corrections

- a. Web OA platform and hosting

- b. Long-term digital preservation (CLOCKSS/Portico, etc.)

- c. Distribution to indexing services (Scopus, PMC, DOAJ, etc.)

Pricing figures have been deducted by openly available price lists of vendors, as for example for Scholastica, Akron Aps, CrossRef, CLOCKSS (see Table 1 , Table 2 ). In all other cases where pricing list or fees were not openly available on the web, prices were indicated after a direct request for proposal or communicated privately. For the latter we have checked with other partners to validate that information. Some service vendors have not split their services in a granular manner but offer a full service for more steps of the publishing workflow. In those cases, we have tried to split those costs or consider the full cost as part of one of the scenarios (see below) which cover the complete manuscript acquisition and article production process.

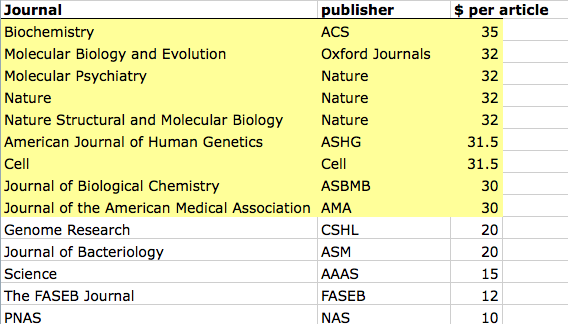

Expenses and fees for each individual service have been arrived at from two main sources. Some standard services have been taken from openly available price lists ( Table 1 ).

Second, we requested quotes from vendors without publicly available fees, or turned to other sources 14 . For services such as manuscript submission and peer review management systems we considered vendors such as Manuscript Central (Clarivate) and Editorial Manager (ARIES).

Other costs such as internal staff costs (including overhead, EU/US standard) were estimated taking into account not only current market costs we have requested ourselves, but also numbers from major publishing houses (MDPI, Wiley, Springer, DeGruyter, Frontiers, Ubiquity, SciELO, Open LIbrary of the Humanities). While some of these publishers have made their costs public ( Table 2 ), others have either provided their numbers under the condition of confidentiality or the numbers were gained from internal sources.

For certain tasks, for example copyediting or typesetting, there are hundreds of individual companies worldwide providing those services on a industry-standard level. In our quote requests, we have considered only those with which we have collaborated in real business life so far or from which we know the performance and service level in detail from co-operations over two decades. Having compared the pricing of those service providers with others, we found only a very small variation of cost for such tasks, which justifies our practical approach. It was never our ambition to perform an exhaustive but always incomplete market study of service providers worldwide, but an attempt to provide an authoritative documentation of approximate current publishing costs as a valuable information tool for decision-makers and other stakeholders in policy drafting, contract negotiations or public discourse.

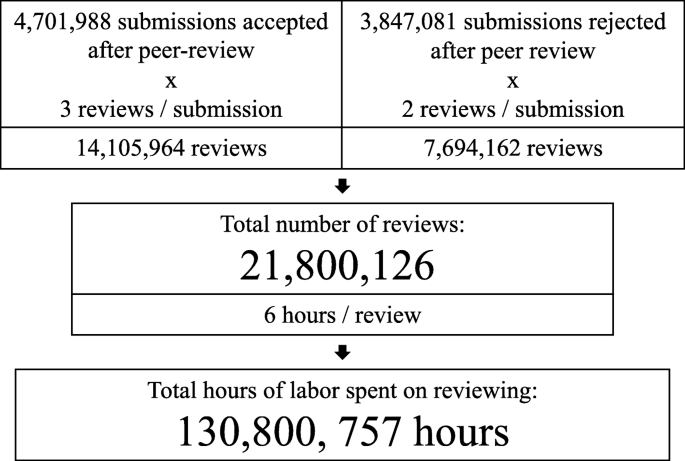

Indirect or fixed costs

The calculation of per-article figures from costs that do not accrue on a per-article basis (e.g., salaries, annual fees, etc.) was based on the following assumptions: (i) The average STM article contains 12 printed pages 13 , with 1500 words on each page (i.e., 18,000 words total). (ii) We estimated an average STM article to contain 10 non-text items such as figures or tables. (iii) We also assumed an average rejection rate of 50% after conventional (pre-publication) peer-review with at least two reports and ten contact requests to secure one reviewer. (iv) We assume a desk-rejection rate of 10% after editorial review. (v) We also base our staff costs on the granular work load per article and not on full-time equivalents (FTE). These assumptions entail that all editorial duties (on average 7.5 person-hours per submitted manuscript) are handled by in-house staff and none by academic editors, while peer-review is still performed by volunteer academics. In this way, staff costs, including overhead expenses, are calculated on a per-article basis (i.e., per published article, not per submitted manuscript). Salary costs are based on industry standards in more economically developed countries for the different editorial tasks. Overhead expenses can vary significantly depending on the profit and loss structure of the publisher and include rent, repairs, depreciation, interest, insurance, travel expenditures, labor burden, telephone bills, supplies, taxes, accounting fees, etc. We have estimated an average 33% overhead on top of salary costs. The following publication tasks are commonly covered by annual (membership) fees plus an initial, one-time set-up or installment fee: Web OA platform and hosting, CLOCKSS/Portico, DOAJ, Altmetric Badge and Crossref. Because these costs accrue regardless of how many articles are published (i.e., fixed costs), we have calculated per-article costs for journals with different numbers of articles published per year. All of these assumptions have been made with the overarching goal to ensure upper-bound costs. For each of these cost items, there exist numerous ways in which their contributions to overall costs can be reduced. Thus, the figures we provide here describe an upper cost ceiling that many publishers will easily fall below.

While some general fixed costs are covered by salary overheads (see above), we deliberately chose to not include certain fixed costs: Cost of sales have not been considered because for open access journals no longer sales representatives are required which have to negotiate renewals of subscriptions with libraries on an annual basis. We also excluded management costs as these are highly variable and in large publishers with many journals (and hence articles), per article costs of management are often negligible. We realize that this may be different for publishers which publish low-volume journals but with nevertheless highly paid executives (see Discussion). Because making an article public (i.e., ‘publishing’) is distinct from locking it behind a paywall, we have also not calculated the often very significant paywall costs. While innovation (or acquisition of innovative technologies) as well as branding and advertising/marketing are crucial for a company to succeed and thrive in a market in the long term, we have also not included these costs as they are not directly related to publishing scholarly articles. Such costs would include conference attendance, advertisement in print, online, social media and search platforms, as well as search engine optimization (SEO). Similarly, government relations (lobbying) may be considered a necessary expense for any business, but as it does not directly relate to the process of publishing academic papers, we did not include these costs in our calculations either. However, we do discuss the probable extent to which these non-publication costs may affect pricing.

The motivation for the above assumptions was to combine a robust cost calculation (i.e., sourced from measurable time efforts and industry-standard salaries) with an upper bound cost calculation which would come to lie above most academic-run journals. However, the journal landscape is diverse and journals can be run on a shoestring budget, supported exclusively by volunteer labor and institutional resources, or by multi-billion dollar publicly traded corporations with professional in-house staff handling every individual step. In an attempt to reflect this heterogeneity, we divided our cost calculations into three broad categories, each with two sub-categories for a total of six scenarios ( Table 3 ).

PPPR - post publication peer-review (i.e., no rejections after peer-review). OJS - Open Journal System

The first two scenarios A and B correspond to professionally run journals where salaried in-house staff handle each manuscript and only peer-reviewers provide volunteer labor. These correspond to traditional commercial journal publishing scenarios. Scenario A differs from Scenario B in that the individual production steps are not sourced from a variety of generic publishing service providers, each specializing in their particular publishing step, but from a full-service provider specialized in scholarly publishing, providing most of the publication services listed above, from a single source. In our example, we have chosen a service provider which is representative for this sector and with considerable name recognition, Scholastica, as such a specialized, full-service provider. Selecting a single, specialized provider is more convenient and requires less expertise than multiple generic providers, as a single contract replaces sourcing and contracting of multiple partners. However, such convenience commonly comes with an additional cost. Scenario A corresponds, e.g., to those society or university-run journals with salaried editors, while many corporate publishers run their journals according to Scenario B. The third scenario takes into account that many scholarly journals are operating with minimal budgets by not paying their editors at all, using institutional servers, for instance with the free, open source Open Journal System handling submission and peer-review, with little space for long-term preservation or indexing. Of course, their institution covers server costs for these journals, but with servers being shared and provided centrally already, per-article costs approach zero. This aspect is analogous to the salaries of the volunteer editors being paid for by their institutions, irrespective of how many hours of editorial work are being volunteered. At first approximation, Scenario A is likely to be the most expensive option, all else being equal, with Scenario B expected to come to lie between Scenario A and the least costly Scenario C.

We calculated an additional sub-category for each scenario to better cover the scholarly diversity. For Scenario A and B we also considered an additional scenario where costs would be reduced by post-publication peer-review as it is practiced by journals like, e.g., F1000Research. In these scenarios, submitted manuscripts are published immediately and peer-review then merely creates additional versions, such that there are no more rejections after editorial review. Journals in Scenario C are often operated by individuals whose primary specialization is not scholarly publishing. Therefore, a provider that bundles the different publishing steps may be more expensive but enticing due to the convenience it offers. Therefore, we also calculated the costs for articles in such scholar-led journals, but with Scholastica replacing the generic service providers.

All costs are calculated per published article, i.e., a journal that publishes 1,000 articles per year has received 2,000 articles if their rejection rate is 50%. Our costs are calculated for the 1,000 published articles, not for the 2,000 submissions the journal has received. For each of the six scenarios, we have also calculated the same costs, but assuming a 90% rejection rate (see raw data file). As fixed costs are distributed over all published articles, article volume per year is another factor we considered. Our calculations yielded a lower bound of 100 articles per year (see results), below which it becomes difficult to operate a journal with in-house staff. Beyond 1,000 articles per year, indirect costs per article shrink to a negligible fraction. We thus calculated per-article costs for each scenario for journals with 100 articles per year and for 1000 articles per year, for a grand total of 24 different cost estimates. The results for the 12 cases that represent the more common journals with an average rejection rate of 50% are depicted in Table 4 .

The scenarios are labeled with A, A2, B, B2, C, C2 (see Table 3 ). Values correspond to an average 50% rejection rate, 90% rejection rate calculations in the text.

Finally, we also considered a seventh scenario which we did not list with the other six: a decentralized, federated platform solution where all scholarly articles are published without being divided into journals. Such a solution is not currently in widespread use, is not based on journals and thus remains, so far, largely hypothetical. While, e.g., Open Research Central may someday evolve into such a “Global Open Archive” as these solutions were called in 2010 15 , at the present time this is still a hypothetical scenario, despite repeated calls for such a platform since then 16 – 20 . With such a modern, decentralized, federated platform providing publishing functionalities without journals (see, e.g., 21 for details), some of the publishing steps listed above become obsolete, while others remain relevant. Steps that may become obsolete include DOIs, long-term archiving such as CLOCKSS or Portico, indices such as Scopus. Relevant steps remaining are typesetting/copyediting, XML preparation, format conversion, plagiarism checks.

An earlier version of this article, with more price information and discussion can be found on PeerJ 22 .

All the data we have based our calculations on are available at Figshare (DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.8118197.v2 ).

One of the first findings of our calculations is that in order to employ at least one 50% FTE of an in-house editor, a journal has to publish approx. 100 articles per year or more. Hence, in the following, we will base our figures on journals publishing at least 100 articles per year (corresponding to 50% FTE) or 1,000 articles (corresponding to 5 FTEs), to show the spread of fixed and indirect costs over the number of articles published.

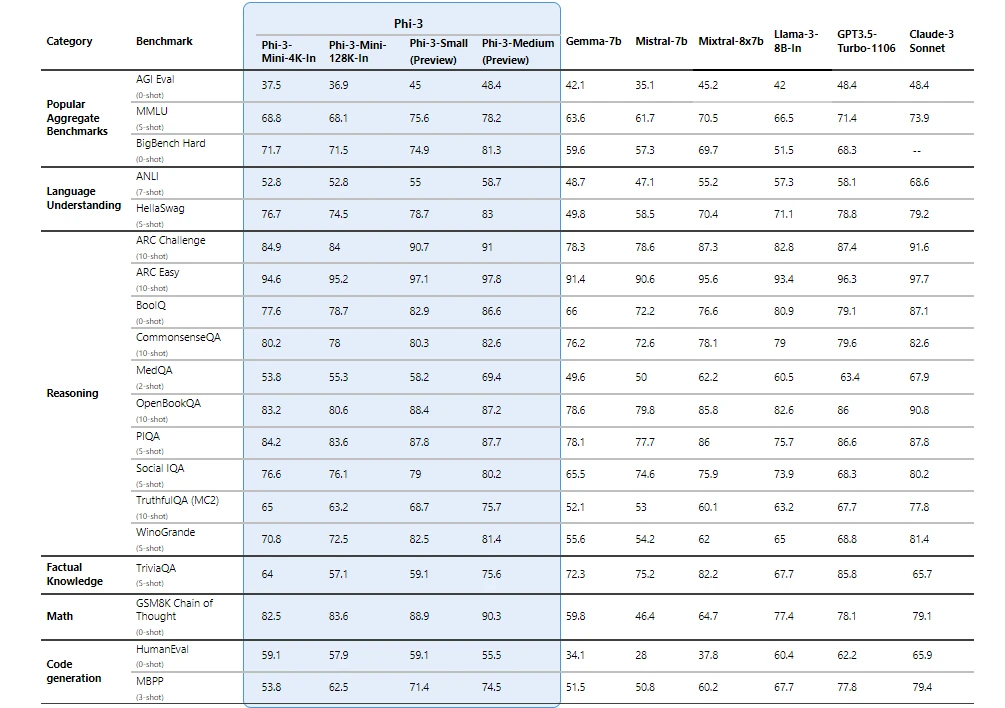

Our calculation of per-article publishing costs in a conventional pre-publication peer-review (50% rejection rate) scenario where all editorial duties are performed by in-house staff (Scenario B) ranges from US$643.61 for a journal that publishes 100 articles per year down to US$565.15 for such a journal that publishes 1,000 articles (or more, as the indirect costs become increasingly negligible around this value). These values consist of US$266.53 direct publishing costs (i.e., Similarity Check, DOI for an article, DOIs for two or more reviews, copyediting, typesetting, formatting figures/graphs/tables, Altmetric badge, indexing, XML and metadata preparation), US$ 289.91 for editorial staff and US$8.72 to US$87.18 for 1,000 to 100 articles, respectively, in indirect costs (i.e., Web OA platform and hosting, digital preservation, memberships).

These numbers were calculated using generic, full-service providers (based in India), where applicable. There are open access service providers that provide packaged deals for the same services as these generic service providers. We have calculated the same steps using a well-known provider in this area, representative for this class of service providers, Scholastica (Scenario A). Not unexpectedly, these figures are slightly higher: US$ 374.08 for direct publishing costs and US$5.92 to US$59.18 for 1,000 to 100 articles, respectively, for indirect costs (editorial staff costs remain the same).

While these costs have been calculated for a generic journal with 50% rejection rate, per-article costs will increase with increased rejection rates and decrease with less rejections as in, e.g., a post-publication peer-review (PPPR) model. In a journal that uses generic service providers and publishes all submitted manuscripts as PDF preprints with a DOI before performing otherwise identical peer-review as described above (i.e., PPPR with in-house editors and volunteer reviewers), per article editorial services drop from US$289.91 to US$140.69 (Scenario A2/B2), with all other costs remaining nearly identical. Conversely, prestigious journals with rejection rates of around 90% see their costs rise to US$1053.87 for 100 articles per year or US$770.53 for the larger journals with about 1,000 articles per year (generic service providers).

These numbers also show that for a conventional journal today, where academics perform their editorial duties on a volunteer basis (i.e., Scenario B, but no editorial costs as editor salaries are paid for by their academic institutions), direct publication costs come to lie at US$266.53 with generic service providers and total costs depend on the scale at which the journal operates. Small journals with 100 articles would face average per article total publication costs of US$353.71, while journals with 1,000 or more articles would only face costs of US$275.25 or less per published article. Even at the highest convenience for a small, volunteer-run journal, costs come to lie at US$454.63 where a full-service provider (Scholastica) handles all of the technical aspects of the work (Scenario C2).

The above calculations (summarized in Table 4 ) demonstrate economies of scale. The more articles are being published, the lower the costs for each article, approaching the fixed costs for each article.

Because of the economies of scale and recent calls for the replacement of journals with a modern publishing platform 15 – 20 , we have also calculated the cost of publishing the annual output of the STM community, approx. 3 million articles, on such a platform that facilitates PPPR organized by academic editors on a single, decentralized, federated platform running modern software solutions (a “Global Open Archive” 15 or “Next Generation Repository” 21 , such as, e.g., Open Research Central or equivalent). Such a platform would dispense with several production steps which are necessitated by the current balkanization of the literature in different journals published by different publishers, but keep others (see Methodology). In this scenario, the indirect and fixed costs per article approach zero due to the high number of published articles (but see Discussion), such that the only remaining costs would be the direct publishing costs of US$190.17 per published article.

Finally, taking a ballpark cost figure of US$600 for a scholarly article with full editorial services (i.e., scenario A/B) and comparing it to the low end of the average price estimate for a subscription article of about US$4,000 10 – 13 , 22 , 23 , it becomes clear that publication costs only cover 15% of the subscription price ( Figure 1 ). Assuming a conservative profit margin of 30% (i.e., US$1,200 per article) for one of the large publishers 24 – 27 , there remains a sizeable gap of about US$2,200 in non-publication costs, or 55% of the price of a scholarly subscription article ( Figure 1 ).

Assuming the commonly accepted US$4,000 price tag for a subscription article, published profit margins of 30% and our calculation of about US$600 in publication costs for a full-service subscription article (scenario A/B, see Table 4 ), there remain US$2,200 in non-publication costs per article.

Since the 1990s, it has been recognized that the prices of scholarly journals were escalating at unsustainable rates 3 . In the last 30 years, this “serials crisis” has never been coherently addressed, let alone solved. With this work, we aim to provide more financial evidence for future evidence-based policies addressing the affordability problem of scholarly communication 1 , 2 .

Prices and Costs

Not only current discussions are addressing the affordability problem in the unit of cost per article 10 – 13 , 23 , 28 – 30 and we follow this precedent. Drawing from publicly available price lists and industry-standard service costs, we find that publishing costs per article vary from US$194.89 to US$723.16, depending on the level of service and publishing volume ( Table 4 ). It is important to emphasize that these are conservative calculations, likely to constitute upper bounds, where innovation and changes in practice can be expected to decrease costs. For instance, our assumptions of an average article containing 12 printed pages (or 18,000 words) and 10 figures or tables is likely a substantial overestimate (especially given that pages with a figure or table must have much fewer than 1,500 words). Moreover, we used US/EU salary levels in our calculations. In countries with lower salaries, labor costs will be correspondingly lower.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the convenience of outsourcing the main publishing services to a specialized full-service provider comes with a small increase in cost (Scenario A vs. Scenario B), when compared to an itemized sourcing of publishing services. In our cost calculation, we have not factored in the management cost of sourcing the itemized services, as we have not included company management in our calculations. Any decision between these two options will thus have to be made after factoring in such costs as well.

Even in the rare, most expensive case, these costs compare very favorably both to the current subscription pricing of around US$4,000-5,000 10 – 13 , 22 , 23 and current APCs (US$1,400-2,200) 11 , 28 – 32 . See 22 for a discussion on subscription and APC pricing. Our highest value encompasses conventional, journal-based pre-publication peer-review with a generic 50% rejection rate at a small journal (~100 articles per year) where all management of peer-review is performed by in-house editorial staff with no volunteer academic editors. Our data suggest that increasing only the rejection rate, for example from 50% to 90%, leads to an increase in publication costs of around 30–40% (e.g., in scenario B from US$565.15 to US$770.53 for 1,000 article journals or from US$643.61 to US$1,053.87 for 100 article journals). Apparently, this is a consequence of the respective increase of direct personnel expenses for managing the peer review process and communicating with both reviewers and authors for classical pre-publication peer review. As currently most highly selective journals publish on the order of 800–900 research articles per year about US$1,000 per article can be seen as an upper bound of total publication costs at such journals.

On the other end of the spectrum are small journals that are run mainly on volunteer efforts. Even in cases where these journals use specialized full-service providers such as Scholastica, there are numerous ways to reduce per-article costs to below the US$100 mark. For instance, specializing in rapid dissemination of short articles reduces per-article costs at the Journal “Findings” to below US$100 33 , when the journal in all other aspects but article length follows our low-volume Scenario C2. Such numbers also highlight one of the problematic aspects of using per-article costs, averaged over a highly diverse publishing landscape.

Market rates for publishing services

The workflow we model consists of verifiable, modular components, available to any entity with the desire to enter the academic publishing world. Numerous publishers are already on the record to operate at similar costs to the ones we have calculated. These publishers include, but are not limited to SciELO, Pensoft/arpha, Open Library of the Humanities, Ubiquity, PeerJ or Scholastica. Our data confirm that at prices of around US$500 per article, these providers stand to arrive at around a 10% profit margin. Further corroborating these calculations, the 2018 STM report cites survey-based data that arrive at only slightly higher average costs than our calculation (US$420-650, excluding overhead, i.e., about US$560-870 with overhead) 13 . Our calculations also fall in the same range as other methodologies 34 .

Our calculations also show that with publishing volumes exceeding 1,000 articles per year, fixed costs shrink below 1% of the direct article costs and become negligible. This was expected and already concluded in a previous analysis 35 . These insights are important for designing a transition towards a scholarly publishing platform instead of journals 15 – 21 .

Due to the limited possibility in dividing labor contracts into arbitrarily small portions, we find that journals with volumes below approx. 100 articles per year would be best served financially if they operated on the concept of volunteer academic editors handling the peer-review, instead of in-house staff.

In conclusion, given the congruence of the available data and the publicly available prices for the services required, the market rate ranges for publication services we arrive at here do not appear controversial. Perhaps more controversial is the number and amount of non-publication costs a scholarly article, funded by the taxpayer, ought to accrue.

Non-publication costs

If the lowest publication costs for journals with volunteer editors constituted merely 5–10% of current subscription prices and publicly reported publisher profits only amount to an additional 30–40%, which non-publication costs are publishers currently facing and taxpayers paying for? While these costs are opaque and variable between publishers and, indeed, between journals, some estimates can be made from publicly available data. If one assumes revenue of about US$4,000 per subscription article (i.e., on the low end of the converging estimates), a conservative 30% profit margin (i.e., US$1,200 per article) for one of the large publishers 24 – 27 and generous publication costs of US$600 per article (scenario A/B; table 4 ), then there remains a sizeable gap of about US$2,200 in non-publication costs per article - more than the sum of publication costs and profits combined, or 55% of the subscription cost of a scholarly article ( Figure 1 ). While some of these costs may be considered necessary for any business, none of them are associated with publishing primary research articles (see Methods).

Running a business: Management. While our cost calculations include generic running costs such as rent, repairs, depreciation, interest, insurance, travel expenditures, labor burden, telephone bills, supplies, taxes, accounting fees, etc., we have explicitly omitted some indirect costs such as management cost and paywalls. For instance, according to their 2016 tax statement, the New England Journal of Medicine spends 4% of its publication revenue on their top ten management staff alone (which would translate to about US$160 per article if applied to our example above; Figure 1 ).

Preventing access: Paywalls. Subscription journals also face costs associated with paywalls. It’s difficult to estimate the cost of such technology for publishers, but the cost of a new paywall for the New York Times was reported to lie between US$25-50 million 36 , 37 . Alternatively, as the functional distinction between subscription articles and OA articles is precisely the missing paywall in OA articles, one could also assume that publishers arrive at their current APC pricing of around US$2,000 by subtracting paywall costs from their subscription price. This assumption would entail paywall costs of approx. US$2,000 per article (i.e., the difference between APC and subscription pricing).

On top of the technical costs of a paywall, one may also consider the legal fees for defending paywalls for this cost item. Publishers have a track record of litigation with regard to articles outside of their paywalls and regularly seek damages in court for actual or perceived threats to their subscription business model 38 – 44 . These costs accrue by seeking to enclose the scholarly literature within the paywalls of publishers via alternative routes in addition to the digital paywalls.

News, advertising, sales, marketing, public relations: branding. Another cost item is publishing non-research content. For instance, for 2017, PubMed lists a total of 1,595 articles published by the Lancet, while Clarivate Analytics only counts 302 articles for their Impact Factor. Assuming that only the latter articles amount to primary research publications, this journal’s revenue also pays for 1,293 non-research articles. Similar numbers also hold for other prestigious journals (e.g.: Nature: 837/2469, Science: 769/2629, New England Journal of Medicine: 327/1449; research/total), often with their own journalist and editorial staff commissioning articles and/or reporting themselves on research and policy news. However, the number of journals where this can constitute a significant fraction of their total costs is presumably small, likely restricted to the most prestigious journals.

Prestigious journals also often practice active author or materials acquisition, by traveling to conferences and laboratories, building networks in a strategy to entice the next exciting research finding to be published in their journals. Active author acquisition accrues costs both in terms of travel and time spent networking and communicating with authors that is not covered in our cost calculations (see Methods).

Sometimes, new journals also need to engage in such author acquisition practices, which, perhaps, can be best subsumed under general marketing or public relations costs required for building and maintaining a brand. These marketing costs also include, e.g., advertising in various venues targeting both authors and subscribers. For many publishers it is also common to promote their brand at conferences and institutions with, e.g., hosted speakers, travel grants or sponsored awards.

Because of the complex, time-consuming negotiations with libraries on ever tighter budgets due to the supra-inflationary subscription price increases, publishers also need to employ expert sales teams. The task of these sales teams is not only to find the most irresistible way to package and bundle subscription journals and/or databases, but also to device the most inexorable psychological strategy for their negotiations with librarians. These sales teams need to operate in close connections with the various advertising, marketing and public relations teams of the publisher to accomplish a coherent brand image. One may argue that in times of OA, these sales costs are not necessary expenses any more and more associated with paywall costs than with publication costs. On the other hand, in an OA world, one may argue that branding was never more important for author acquisition.

New technologies: innovation and acquisitions. Publishers also need to invest in innovation, in order to stay current with their technologies and functionalities. While scholarly publishers have been quick to transition from print to web-based technologies in the past, the digital functionalities of most of the scholarly literature today lag at least a decade behind current functionalities of other digital objects outside of the scholarly literature. The level of investment in innovation thus remains unclear and its effects questionable. Instead of investments into their own technological innovation, publishers today appear to acquire companies that have invented desired functionalities around the scholarly workflow, with the goal to provide services beyond publications 45 – 48 .

Government relations: Lobbying. Most international publishers, as any other corporation, also spend significant amounts of money on government relations (i.e., lobbying). Some of these corporations employ staff at the vice president level not only in the most important research nations, but also at the level of supra-national bodies such as the European Commission 49 . These staff, in turn, employ assistants and other members of their teams. Obviously, the task of these employees is to protect current revenue streams, e.g., subscription or APC income. For instance, one publisher, Elsevier, spends more than 400,000€ per year on lobbying at the level of the European Commission alone 50 . The consequences of such efforts have been observable, e.g., in the so-called “Finch Report” in the UK 51 , which surprised many commentators with its publisher-friendly recommendations ( 49 ,see, e.g., 52 ).

Which non-publication costs should remain bundled up with publishing? Regardless of all of these estimates necessarily remaining vague and imprecise, the fact remains that the scholarly community must eventually make a number of decisions, if it is to tackle the affordability problem. Which of the above non-publication costs should remain bundled up with the process of publishing scholarly research articles? Which of these costs are avoidable, which necessary and which even desirable? Are profit margins of 30–40% on taxpayer funds tolerable?

In fact, one may even ask which of the services we list as part of the scholarly publishing standard are actually necessary for scholarly publishing. After all, journals such as the Journal of Machine Learning Research, Discrete Analysis or the Journal of Open Source Software publish their articles with internal costs below US$10 53 , 54 . Likewise, the preprint archive arXiv publishes their articles at similar costs 55 . Overlay journals 56 – 58 take advantage of the preprint infrastructure to reduce costs much below the ones we have calculated here. A competitive market where service providers compete with their services and where price pressure forces market participants to consider internal production costs, unlike the current publisher monopolies, would facilitate such decision-making 22 , 59 .

Data availability

Acknowledgments.

We are indebted to Michael Dowling, Jon Tennant, Isabell Welpe, Bernhard Mittermeier and Pete Binfield for critically reading and commenting on earlier versions of this document. We are also grateful to Abel Packer from SciELO and Brian Cody from Scholastica for privately sharing cost data from their organizations with us.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

Reviewer response for version 2

Pandelis perakakis.

1 Open Scholar CIC, Birmingham, UK

2 Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

All initial concerns and recommendations were addressed in the revised version of the manuscript.

Is the work clearly and accurately presented and does it cite the current literature?

If applicable, is the statistical analysis and its interpretation appropriate?

Not applicable

Are all the source data underlying the results available to ensure full reproducibility?

Is the study design appropriate and is the work technically sound?

Are the conclusions drawn adequately supported by the results?

Are sufficient details of methods and analysis provided to allow replication by others?

Reviewer Expertise:

Scholarly communication, Open peer review

I confirm that I have read this submission and believe that I have an appropriate level of expertise to confirm that it is of an acceptable scientific standard.

Lisa Rose-Wiles

1 Seton Hall University Libraries, Seton Hall University, South Orange, USA

Library science, information literacy, citation analyses, circulation and journal/book pricing analyses.

Reviewer response for version 1

I concur that the “supra-inflation increase of subscription prices for scholarly journals” is a critical issue, especially for academic libraries, and that this is a valuable contribution to the literature.

I also concur with the previous reviewer that the “scenarios” and tables could be better explained and organized for greater clarity. Also further indicators of variance would be helpful - for example, there are surely significant differences (especially in “fixed or indirect costs”) based on geographic location. I also find myself wondering which (if any) of the costs to publishers are tax deductible, which would effectively increase the profit margin.

While the main focus of the manuscript is the cost of producing articles, to place this in broader perspective It would be helpful to clarify more explicitly that there are two major price components to journal articles: (1) Journal subscription costs, which are typically borne by libraries (although no doubt some researchers still subscribe to their favorite journals themselves), and (2) article-processing charges (APC’s) which are in principle an open-access alternative to subscriptions, but in practice often simply shift the cost from an institution’s library to its faculty, research office and/or some other institutionally-funded entity. Both contribute directly or indirectly to the high price of student tuition and the chronic under-funding of many academic libraries, but subscription prices seem to be the greater issue since the average “per article price” (see below) is considerably higher.

For readers not necessarily familiar with the various journal pricing models, the authors might note that both journal prices and APC’s vary enormously by discipline, especially STEM vs. humanities, and that the practice of “Big Deal” bundling (especially by large commercial publishers) can make it very difficult for librarians to disentangle the actual subscription cost per journal. It would be helpful to include some discussion and more explicit data on the widely varying range of APC’s, which, in my experience, seem independent of actual subscription costs. I am more familiar with the pricing models for STEM journals (typically > US $2,500 APC regardless of journal subscription price), but it is my impression that when humanities journals do charge authors, the fee is much lower. This would be an interesting topic to explore in a follow-up article. Granted that STEM articles typically include multiple tables and figures that are costly to produce, but is the price differential really as substantial as the differences in subscription costs or APC’s?

In the final paragraph of the results (p.6) and in Figure 1, the authors compare the article cost with “the average price estimate for a subscription article of about US$4,000”. Where did this figure come from and what is it based on? Is this an across the board “per library” average, in which case the wide variation in prices paid by different libraries (at least in the US) is surely another confounding factor. Again, there should be some discussion of the vast difference in pricing among disciplines, or if this is based on STEM journals as I suspect, that should be clarified. Also the average APC price should be included in the comparison; it is interesting that it appears to be considerably less than the quoted US$4,000 subscription “per article” cost. This brings up a further question for the future: in hybrid journals, does charging APC’s result in lower subscription prices, or are APC’s effectively layered on top of subscription prices?

Another point that is only tangentially referenced (e.g. “volunteer academic editors”) is that many of the costs associated with publishing are actually borne by the institution and its academic faculty, who not only produce the scholarship but also review articles and often act as editors as well. This labor is typically unpaid. “Volunteer academic editors” in well-funded institutions may receive some form of course release, additional office space and/or clerical support, but again (see first paragraph) these costs are borne by the institution and to some degree passed on to its students; they are not borne by the publishers. Of course this point has been made many times before, but since the authors are discussing various costs involved in publication it is worth noting again.

As a final comment, it would be informative to have responses from publishers, especially small “non-profit” or “not-for-profit” publishers on this publication.

Very thought provoking!

I confirm that I have read this submission and believe that I have an appropriate level of expertise to confirm that it is of an acceptable scientific standard, however I have significant reservations, as outlined above.

Institute of Zoology - Neurogenetics, Universität Regensburg, Germany

Response to Reviewer #2: Lisa Rose-Wiles:

I also concur with the previous reviewer that the “scenarios” and tables could be better explained and organized for greater clarity.

We thank both reviewers for their suggestions and are confident to have now adequately addressed this very valid concern in the new, revised version of the manuscript.

Also further indicators of variance would be helpful - for example, there are surely significant differences (especially in “fixed or indirect costs”) based on geographic location. I also find myself wondering which (if any) of the costs to publishers are tax deductible, which would effectively increase the profit margin.

We have now further emphasized that our salary calculations are based on western (i.e., US/EU) industry standards and that countries with lower salary levels would hence face lower costs. This is to arrive at upper bound figures, describing the costliest way of publishing, from which one can always find ways to reduce costs. We have further emphasized this approach also at the very beginning of the Discussion section now.

While the main focus of the manuscript is the cost of producing articles, to place this in broader perspective It would be helpful to clarify more explicitly that there are two major price components to journal articles: (1) Journal subscription costs, which are typically borne by libraries (although no doubt some researchers still subscribe to their favorite journals themselves), and (2) article-processing charges (APC's) which are in principle an open-access alternative to subscriptions, but in practice often simply shift the cost from an institution's library to its faculty, research office and/or some other institutionally-funded entity. Both contribute directly or indirectly to the high price of student tuition and the chronic under-funding of many academic libraries, but subscription prices seem to be the greater issue since the average “per article price” (see below) is considerably higher.

For readers not necessarily familiar with the various journal pricing models, the authors might note that both journal prices and APC's vary enormously by discipline, especially STEM vs. humanities, and that the practice of “Big Deal” bundling (especially by large commercial publishers) can make it very difficult for librarians to disentangle the actual subscription cost per journal. It would be helpful to include some discussion and more explicit data on the widely varying range of APC's, which, in my experience, seem independent of actual subscription costs. I am more familiar with the pricing models for STEM journals (typically > US $2,500 APC regardless of journal subscription price), but it is my impression that when humanities journals do charge authors, the fee is much lower. This would be an interesting topic to explore in a follow-up article. Granted that STEM articles typically include multiple tables and figures that are costly to produce, but is the price differential really as substantial as the differences in subscription costs or APC's?

We agree with all the arguments here. Therefore, we now more explicitly reference the longer, preprint version of our manuscript, where we not only discuss pricing strategies and business models, as suggested, but also policy options. However, in this more condensed version, we made a conscious effort to focus exclusively on the cost aspect, as we felt the original version was too long, unwieldy and difficult to read as it was covering too many topics at the same time.

In the final paragraph of the results (p.6) and in Figure 1, the authors compare the article cost with “the average price estimate for a subscription article of about US$4,000”. Where did this figure come from and what is it based on? Is this an across the board “per library” average, in which case the wide variation in prices paid by different libraries (at least in the US) is surely another confounding factor.

This explanation was indeed lost as we transitioned from our longer preprint version to this shorter one. We are very grateful for having this pointed out. We now reference the sources of these calculations. The most recent one is very simple: dividing the estimated US$10b in journal revenue by the number of published articles (2m): ~5k. As some other sources mention 4k, we went with the lower bound of these estimates in the literature.

Again, there should be some discussion of the vast difference in pricing among disciplines, or if this is based on STEM journals as I suspect, that should be clarified. Also the average APC price should be included in the comparison; it is interesting that it appears to be considerably less than the quoted US$4,000 subscription “per article” cost. This brings up a further question for the future: in hybrid journals, does charging APC's result in lower subscription prices, or are APC's effectively layered on top of subscription prices?

We now mention the APC price range of US$1,400-2,200 and the 8 references upon which we base this range.

We now make it more explicit what is being paid in terms of salary and which work is being carried out by volunteers. We also explicitly mention the costs covered by institutions (e.g., salaries, servers) and relate them to per-article cost.

We list numerous publishers which are already on the record for publishing in this cost range and cite journals that have much lower costs than our figures. In the acknowledgements, we mention that we have been made privy of internal cost structures to validate and test our figures. As we mention in the article, our numbers match those from other methodologies (e.g. surveys). The preprint version has been available since 2019 and has even received attention in trade organs such as the “Scholarly Kitchen”. In other words, publishers have already vetted our numbers and have had ample opportunity over a number of years to comment on our work and improve it by criticism. Given that our numbers match so well with the available evidence and that our article has received considerable attention from the industry since 2019, perhaps one may interpret the fact that the expensive legacy publishers so far have not publicly commented on these numbers, as evidence that there may not be much left to criticize? Of course, another reason may be that the more expensive publishers may hesitate to draw more attention to the fact that they are so much more expensive. In this case, we would appreciate any suggestions in how we may be able to force these publishers to acknowledge and comment on our calculations. F1000Research allows for comments on the manuscript and perhaps a drive to invite publishers of all ranges to contribute so such a comment may be instructive?

Society publishers, so far, have refrained from public comments other than generally stating that they use publication income to finance society services. We allude to many such and related costs in the “non-publication costs” section of the manuscript.

This article reports a breakdown of article publication costs —from manuscript submission to indexing— for different publication scenarios. There are at least two fundamental reasons why analysing and reporting the realistic cost of publishing a research article is of paramount importance. First, given the exorbitant sums of public money spent to publish the world’s scholarly output it is imperative that we know where exactly this money goes. This information can perhaps mobilise governments, funders, individual scholars, and the general public to demand more sustainable publication models that provide only those essential services that truly add value to scholarly works. Second, a granular account of publishing costs can incentivise more scientific societies and academic groups to abandon their commercial publishers and establish alternative models that better serve the needs of scholarly communication. There is no doubt therefore that this is an extremely valuable report that should be widely disseminated. My review will mainly focus on some recommendations that in my opinion would improve the presentation and utility of the results.

The cost analysis provided in this report is based on a list of 24 services grouped in three distinct categories: content acquisition, preparation, and dissemination. A first minor observation is that in the category of content acquisition, it would probably be more intuitive to list “online submission system” as the first item (before “searching and assigning reviewers”) to match the publication workflow. A second and more important observation is that in this list, and throughout the manuscript, services are sometimes confounded with service providers. Since there are more than one providers for each of the services, I strongly recommend that the list only includes services, whereas in the manuscript different options for each service can be discussed. For example Crossref is not the only option for “DOI registration”, which I believe should be the title of this particular service. Similarly, the service provided by CLOCKSS/LOCKSS/Portico, could be called “long-term digital preservation”. Also, it is not clear what the service provided by OAPEN is, while “upload to Scopus…”, could be called “distribution to indexing services”. Should the authors decide to follow this recommendation I would advise to also modify the accompanying excel file accordingly.

The “Direct or variable costs” subsection in the methods section would be easier to follow if it was structured differently, starting with the list of services and then explaining how pricing information was obtained.

Following the logic that the list of services is the nucleus of the cost analysis, and the report itself, I suggest that table 1 is modified so that the first column displays the services and the second column the providers. Also, it is important that the terms in the services list are used consistently throughout the manuscript. For example, in table 1 we find a service termed “peer review” and another called “peer review management”. It is not clear how these services correspond to the original list. When a service provider offers more than one service in the list, I would recommend to include all of these services in the table. If it is considered convenient to create a new grouping (e.g., peer review management), it should be clear —in the table and in the manuscript— which services from the original list are included in this group (e.g., 1a, 1b, 1c, etc.).

The “scenarios” section should include a more thorough description of the different scenarios, as well as the motivation for selecting each of these scenarios as a separate use case. This description of what each scenario refers to is attempted in the “results” section but in a rather anarchic and hard to follow manner. In the “scenarios” section the authors vaguely mention that these scenarios “...correspond either to existing publishing options or to options that have been discussed in the literature”, but neither are these options clearly delimited nor specific references are provided. I therefore found it very hard by reading the manuscript to understand exactly which publication model, combination of services, and choice of providers each scenario refers to. This was made possible only by carefully analysing the formulas for the different calculations in the excel file. However, even after this more careful analysis, the motivation behind each scenario remained unclear. For example, it seems that the only difference between scenarios A and B in terms of content acquisition is using one service provider instead of another. In scenario A scholastica is used for online submission management (cell L18), while Akron is used in scenario B (cell J19).

I recommend that the different scenarios are not defined based on the choice of specific providers but according to different, clearly explained publication models, characterised, for example, by use of existing publishing infrastructure (e.g., institutional or disciplinary repositories as in the case of existing overlay journals), variable rejection rates, number of published articles, review policies, voluntary or hired editorial work, etc. The available choice of providers for specific services (or groups of services) and their impact on the costs can be discussed in the manuscript and even presented as a separate table. However, I consider it important that the initial scenarios are reported without any reference to specific providers but rather using average (or low/high) estimates. Otherwise, in their present form, tables 3 and 4 are very hard to follow. In both tables publication choices (number of articles, review models, voluntary editors) are mixed with providers (scholastica, generic providers, etc.) without a clear description (in the table or the manuscript) of the different publication models, or the services offered by each provider. For example, from the excel file I deduced that scenarios A2, B2 and C do not include costs for online submission, but it is not clear from the discussion in the manuscript or from the brief labels in table 3, which exact models allow the omission of these costs and how.

Insisting on the necessity to adequately describe the different publication scenarios, in the “scenarios” section the authors refer to a “decentralized/federated platform providing publishing functionalities”. However, again it is not clear what are the foundations of this model (e.g., a reference could be provided to the next generation repositories initiative promoted by COAR [1], or other similar proposals in the literature, such as in reference “20” in the manuscript), and whether this model is represented in one of the scenarios. Similarly, the authors briefly mention a PPPR model in the “results” section but there is no clear description of what exactly this model entails and which services from the original list allows to omit or circumvent.

To summarise, I strongly recommend that the different publication scenarios refer to publication options (not choice of providers) and that they are concisely described in the corresponding section with references to the literature or to existing examples when possible. It should be clear which services from the list correspond to each scenario and how different scenarios allow the omission of certain services. The different options for service providers should be discussed separately. For example, it would be useful to report the impact on the publication costs of choosing scholastica or Akron as a provider for a specific list of services (drawn from the initial services list) in a given publication scenario.

As a minor comment, I suspect that J21 is missing from the formula used to calculate cell J26. I would recommend that the authors had another careful look at their formulas to avoid similar omissions or errors.

Overall, I commend the authors for their work and invite them to consider my recommendations that I believe will significantly improve the uptake of this extremely valuable information.

References:

[1] https://www.coar-repositories.org/news-updates/what-we-do/next-generation-repositories/

Response to Reviewer #1: Pandelis Perakakis:

The cost analysis provided in this report is based on a list of 24 services grouped in three distinct categories: content acquisition, preparation, and dissemination. A first minor observation is that in the category of content acquisition, it would probably be more intuitive to list “online submission system” as the first item (before “searching and assigning reviewers”) to match the publication workflow.

Thank you, corrected.

A second and more important observation is that in this list, and throughout the manuscript, services are sometimes confounded with service providers. Since there are more than one providers for each of the services, I strongly recommend that the list only includes services, whereas in the manuscript different options for each service can be discussed. For example Crossref is not the only option for “DOI registration”, which I believe should be the title of this particular service. Similarly, the service provided by CLOCKSS/LOCKSS/Portico, could be called “long-term digital preservation”. Also, it is not clear what the service provided by OAPEN is, while “upload to Scopus…”, could be called “distribution to indexing services”. Should the authors decide to follow this recommendation I would advise to also modify the accompanying excel file accordingly.

This was our oversight and it is an excellent suggestion. We are now following it 100%, also in the Excel spreadsheet.

This is how it should be and we have no good explanation for why we did not write it that way. We have now re-ordered all components as suggested.

Following the logic that the list of services is the nucleus of the cost analysis, and the report itself, I suggest that table 1 is modified so that the first column displays the services and the second column the providers.

Also, it is important that the terms in the services list are used consistently throughout the manuscript. For example, in table 1 we find a service termed “peer review” and another called “peer review management”. It is not clear how these services correspond to the original list. When a service provider offers more than one service in the list, I would recommend to include all of these services in the table. If it is considered convenient to create a new grouping (e.g., peer review management), it should be clear -in the table and in the manuscript- which services from the original list are included in this group (e.g., 1a, 1b, 1c, etc.).

I see the point here, of course. We have been able to quickly fix the instances where it was just a matter of replacing a few words. However, it was not easy to address this very relevant point everywhere, as it is many times easier to refer to a series of steps with a shorthand rather than with a long list. Sometimes that shorthand can be a provider (e.g., Scholastica), sometimes it is a functionality such as, e.g., “OJS” for a system that manages submission, manuscript tracking and review management all at the same time. We have tried to rephrase as many of such instances as possible, but we are not sure if we were able to address this point in every single instance.

It is completely obvious how this section must be confusing for readers and, again, we do not have a good explanation for why we did not provide sufficient detail. Our lack of explanation could also be seen in some of Lisa Rose-Wiles’ comments. In attempting to follow these suggestions, we now have provided not only detailed explanations for each scenario in the text, but have also updated Table 3. In brief, scenario A and B differ in that B cases source multiple, generic publishing providers for the different steps (lower cost, more contracts, requires expertise), while A sources many steps from a single provider, specialized in scholarly publishing (more convenient, less expertise required, higher cost). Scenario C also covers all steps in principle, but does not count some costs such as editors (volunteers) or servers (institutional server) or a submission/tracking system (e.g., OJS). Post-publication peer-review decreases rejections and hence price (A2/B2). Scenario C2 replaces, e.g., servers and OJS with Scholastica.

We now cite Perakakis et al. 2010 very prominently, as well as the COAR report, together with a brief explanation of the concept. Both are referenced with the name they gave these solutions, i.e., “global open archive” or ”next generation repository”, respectively.

We are confident that the current version now addresses all the raised issues and that our choice of scenarios becomes clearer in the way we explain them now.

We have triple-checked these cells in the spreadsheet and could not find any missing values. We have also checked all adjacent cells for possible errors and were not able to find any. We have gone over the entire spreadsheet both for the consistency of the calculations, the accuracy of the text descriptions and whether any of the costs needed to be updated due to change market rates. We have not been able to locate any problems. We suggest arranging an online call with video and screen sharing to identify and remove potential errors we may have missed or are unable to identify.

What Is the Real Cost of Scientific Publishing?

After spending years researching, scientific researchers publish their findings to share them with the larger scientific community. It is standard procedure that peer-reviewed scientific journals charge a significant publication fee for publishing a paper , especially traditional print journals. The cost of publishing can be very high, depending on the journal selected. Recently, these publication fees have come into question, with the scientific community wondering what the real cost to publishers is.

What Costs are Involved in Publishing?

Scientific publishing costs vary from journal to journal. Most journals are unwilling to disclose their publishing costs, so estimations are typically done based upon general industry statistics and revenues. There are costs involved in publishing an article , including the staff, distribution costs, and printing fees. There is also a significant amount of work done behind the scenes that takes a paper from submission to publication. Publishers often have to edit, proofread , check for plagiarism, and send the papers for peer review , all which increase the cost of publishing.

How Much Does it Cost to Publish?

Publishing costs for journals can be high. According to one study that analyzed industry data from the consulting firm Outsell, the typical profit margins for the academic publishing industry are around 20 to 30 percent. Estimating the final cost of publication per paper based upon revenue generated and the total number of published articles, they estimate that the average cost to publish an article is around $3500 to $4000. This estimate is most likely very high, especially for open access journals that typically only publish digital copies. The cost per paper in these journals could be as low as a few hundred dollars per article.

Who Pays to Publish in Journals?

A large percentage of the cost of publishing a research paper falls upon the researchers. Most journals charge a significant fee to those submitting a paper, sometimes in the thousands of dollars. The paper’s author might have to pay these fees, although sometimes his or her university or institution has a subscription fee or otherwise covers the cost of publishing. Some journals are able to provide a much lower fee for publication because the government, a university, or a society subsidizes them.

Journals with a higher publication fee defend their costs by saying they put more effort into reviewing and editing each article, and are more selective about the articles published. Researchers continue to publish in these journals because they provide a greater prestige to the author due to their long-standing, esteemed reputation.

The Future of Journal Costs

Until there is more clarity on exactly how much each publishing house spends on publishing each article, the research community will never know what the real cost of publication is. There is pressure to lower the amount charged to authors to have an article published, and some journals are making it easier for researchers to publish their work . However, it will be years before the most well-respected and often most expensive journals begin to lower their fees, both for submitting and reading articles, making it easier for the scientific community to publish, read, and share information on the latest findings.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Open Access Publishing Fees Skyrocket, Invites Concerns on Equitable Knowledge Dissemination

Open access (OA) publishing has gained momentum over the past few decades. It was reported…

- Free Resources

A Comprehensive Global Examination of Open Access Awareness, Attitudes, and Funding in Scholarly Publishing

The global proliferation of open-access (OA) publishing stands as a pivotal focus for researchers, institutions,…

- Thought Leadership

Knowledge Without Walls: Enago’s comprehensive global survey report on open-access publishing

In the ever-evolving landscape of scholarly communication, the global expansion of open-access (OA) publishing has…

- Publishing Research

- Submitting Manuscripts

Publishers Reimagining Open Access Funding and Publishing: APCs finally being replaced with innovative models

Recent years have seen a dynamic transformation in the academic publishing landscape, driven by the…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Democratizing Science: The power of open access in fostering diversity and inclusivity

Open access encompasses a set of principles and practices with the overarching goal of making…

Open Access Publishing Fees Skyrocket, Invites Concerns on Equitable Knowledge…

Balancing Between Scalability and Openness: An interview with Ginny Hendricks

Author Perspectives on Open Access: Fostering community and equitable knowledge…

Open Access Week 2023 With Enago: Embracing “Community over Commercialization”

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Open Access Fees and Funding

All articles published in Scientific Reports are made freely and permanently available online immediately upon publication, without subscription charges or registration barriers. Further information about open access can be found here .

As authors of articles published in Scientific Reports , you are the copyright holders of your article and grant to any third party, in advance and in perpetuity, the right to use, reproduce or disseminate your article.

Benefits of open access

Publishing OA offers a number of benefits, including greater reach and readership for your work:

Find out more about benefits of OA .

Article processing charges (APC)

Authors who publish in Scientific Reports are required to pay an article processing charge (APC). The APC price will be determined from the date on which the article is accepted for publication.

The current APC, subject to VAT or local taxes where applicable, is: £2090.00/$2590.00/€2290.00

Visit our open access support portal and our Journal Pricing FAQs for further information.

Open access funding

Visit Springer Nature’s open access funding & support services for information about research funders and institutions that provide funding for APCs.

Springer Nature offers agreements that enable institutions to cover open access publishing costs. Learn more about our open access agreements to check your eligibility and discover whether this journal is included.

Springer Nature offers APC waivers and discounts for articles published in our fully open access journals whose corresponding authors are based in the world’s lowest income countries (see our APC waivers and discounts policy for further information). Requests for APC waivers and discounts from other authors will be considered on a case-by-case basis, and may be granted in cases of financial need (see our open access policies for journals for more information). All applications for discretionary APC waivers and discounts should be made at the point of manuscript submission; requests made during the review process or after acceptance are unable to be considered.

Creative Commons licenses

OA articles in Springer Nature journals are published under Creative Commons licenses. These provide an industry-standard framework to support easy re-use of OA material. Under Creative Commons licenses, authors retain copyright of their articles.

Scientific Reports articles are published OA under a CC BY license (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license). The CC BY license is the most open license available, and is considered the industry 'gold standard' for open access; it is also preferred by many funders. This license allows readers to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and to alter, transform, or build upon the material, including for commercial use, providing the original author is credited.

In instances where authors are not allowed to retain copyright to their own article (where the author is a US Government employee for example), authors should contact the Open Research Support team before submitting their article so we can advise as to whether their non-standard copyright request can be accommodated.

Authors are advised to check their funder's requirements before selecting OA, to ensure compliance. Learn more about funder compliance .

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Disciplines

- Our Journals

- Login/SignUp

How Much Does It Cost to Publish a Research Paper?

- September 11, 2023

Are you worried about how much does it costs to publish a research paper? It is the most important factor to consider when looking for publication services. The significance of publishing research can’t be overstated. However, research publishing includes multiple factors essential for researchers to understand.

In this article, we will help you understand the expenses of research paper publication and the possibility of a paper being rejected after acceptance.

The cost of publishing a research paper can vary depending on multiple factors, including the journal chosen and any optional services selected.

Article Processing Charges (APCs)

Many journals demand that authors pay APCs to cover the research publication costs. These charges may range from a hundred to thousands of dollars per paper. The amount often depends on the journal’s reputation, impact factor, and the level of service provided.

Submission Fees

Some high-indexed journals also charge article submission fees from authors for manuscript review. These fees help cover the cost of the peer-review process. The submission fees generally range from a hundred dollars.

Page Charges

Besides APCs, some journals may require authors to pay page charges, particularly for printed paper copies. These charges vary based on the number of pages in the final publication.

Color and Supplementary Material Fees

You may incur additional charges if your paper includes color figures, tables, or supplementary materials. These fees can add up, so being aware of them is essential.

Optional Services

Suppose you are finding out how much it costs to publish a research paper. In that case, it is pertinent to mention that many publishers offer optional services such as expedited review, open access options, and professional editing services with additional costs.

Membership Fees