- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

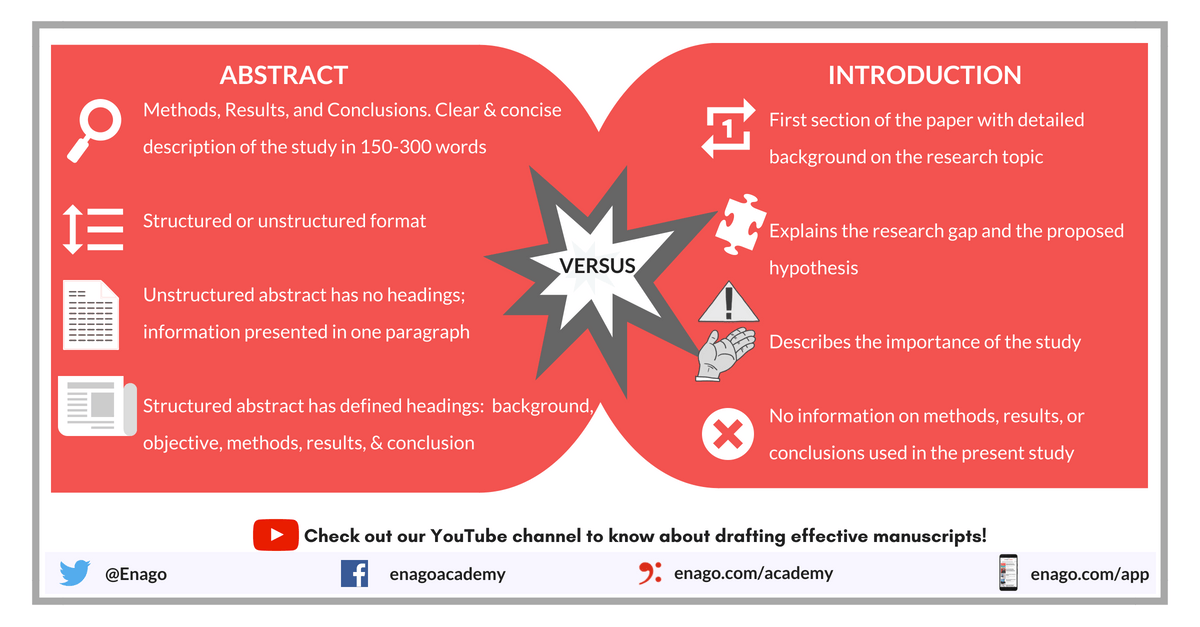

Abstract vs. Introduction—What’s the Difference?

3-minute read

- 21st February 2022

If you’re a student who’s new to research papers or you’re preparing to write your dissertation , you might be wondering what the difference is between an abstract and an introduction.

Both serve important purposes in a research paper or journal article , but they shouldn’t be confused with each other. We’ve put together this guide to help you tell them apart.

What’s an Introduction?

In an academic context, an introduction is the first section of an essay or research paper. It should provide detailed background information about the study and its significance, as well as the researcher’s hypotheses and aims.

But the introduction shouldn’t discuss the study’s methods or results. There are separate sections for this later in the paper.

An introduction must correctly cite all sources used and should be about four paragraphs long, although the exact length depends on the topic and the style guide used.

What’s an Abstract?

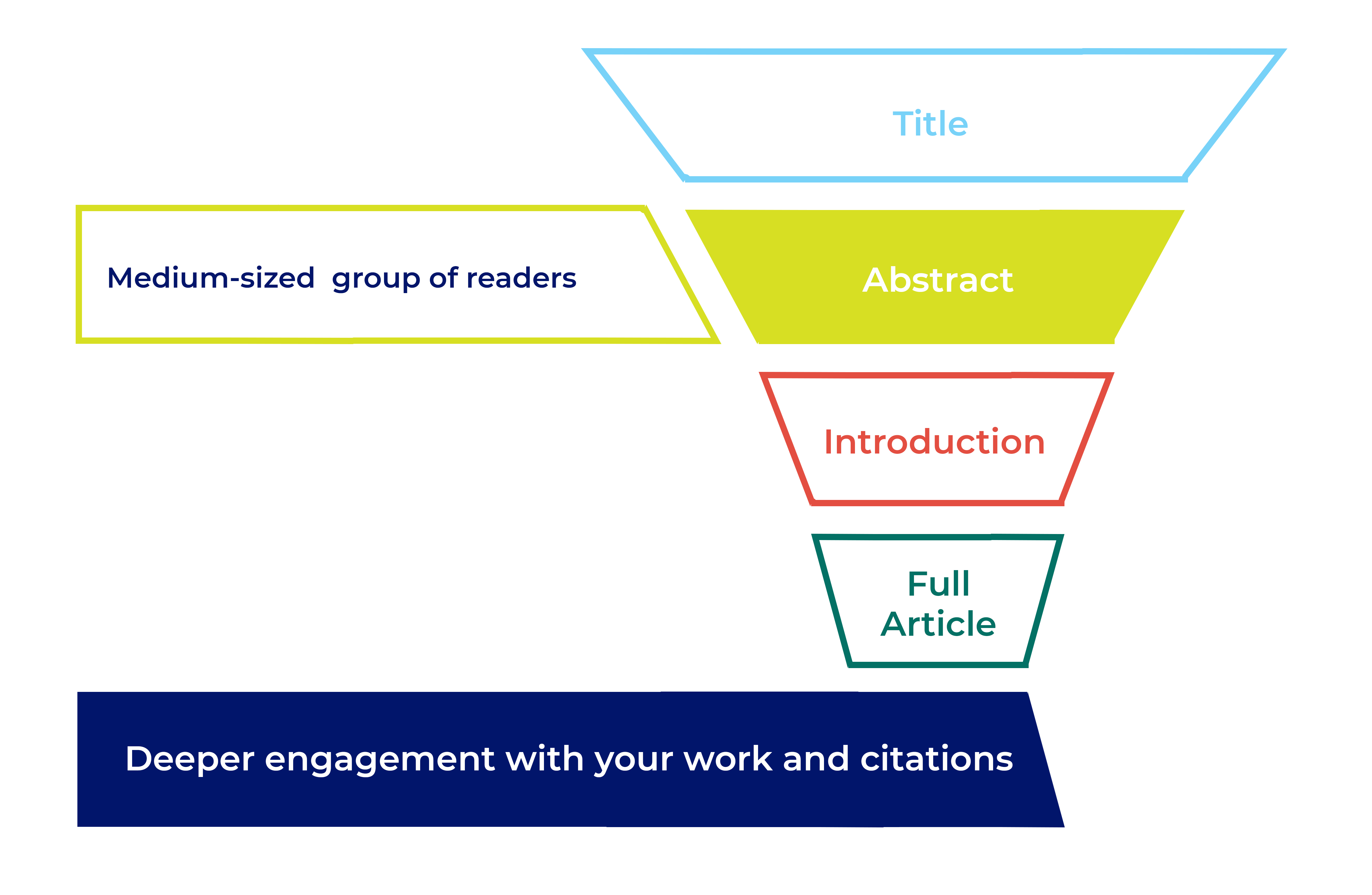

While the introduction is the first section of a research paper, the abstract is a short summary of the entire paper. It should contain enough basic information to allow you to understand the content of the study without having to read the entire paper.

The abstract is especially important if the paper isn’t open access because it allows researchers to sift through many different studies before deciding which one to pay for.

Since the abstract contains only the essentials, it’s usually much shorter than an introduction and normally has a maximum word count of 200–300 words. It also doesn’t contain citations.

The exact layout of an abstract depends on whether it’s structured or unstructured. Unstructured abstracts are usually used in non-scientific disciplines, such as the arts and humanities, and usually consist of a single paragraph.

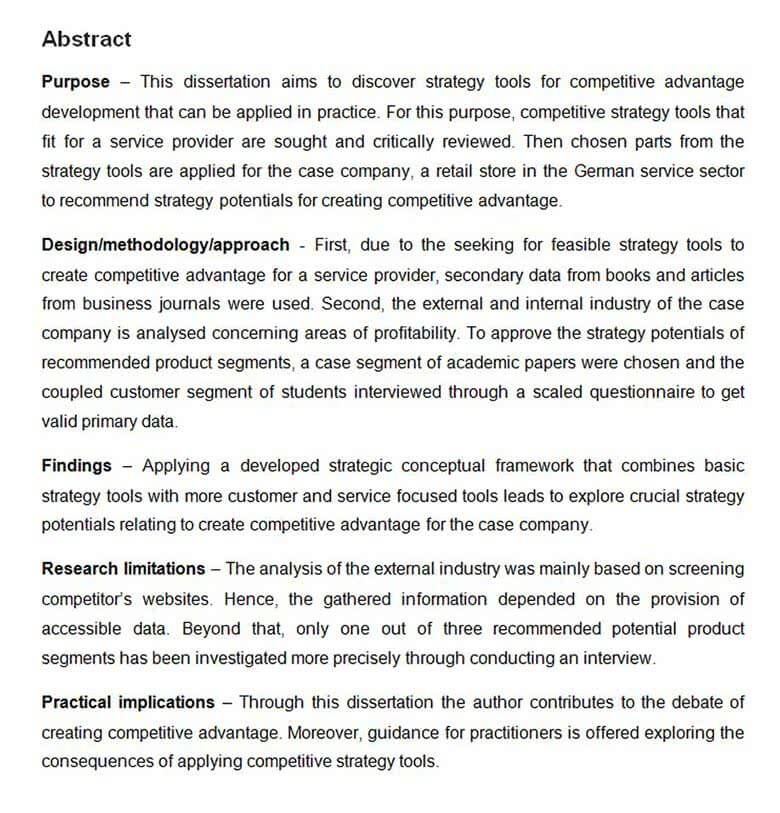

Structured abstracts, meanwhile, are the most common form of abstract used in scientific papers. They’re divided into different sections, each with its own heading. We’ll take a closer look at structured abstracts below.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Structuring an Abstract

A structured abstract contains concise information in a clear format with the following headings:

● Background: Here you’ll find some relevant information about the topic being studied, such as why the study was necessary.

● Objectives: This section is about the goals the researcher has for the study.

● Methods: Here you’ll find a summary of how the study was conducted.

● Results: Under this heading, the results of the study are presented.

● Conclusions: The abstract ends with the researcher’s conclusions and how the study can inform future research.

Each of these sections, however, should contain less detail than the introduction or other sections of the main paper.

Academic Proofreading

Whether you need help formatting your structured abstract or making sure your introduction is properly cited, our academic proofreading team is available 24/7. Try us out by submitting a free trial document .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract vs essay “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

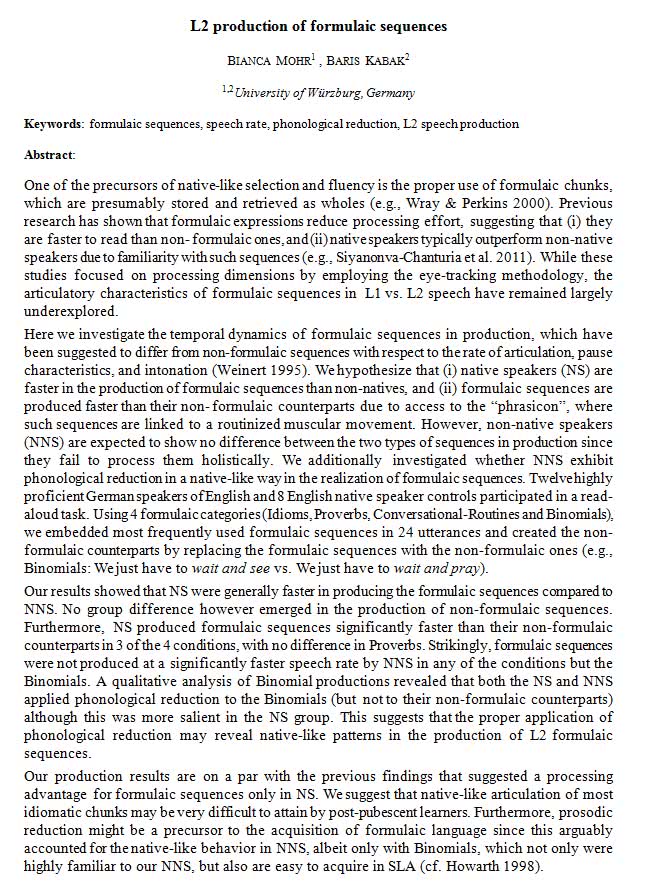

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract vs essay “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract vs essay “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

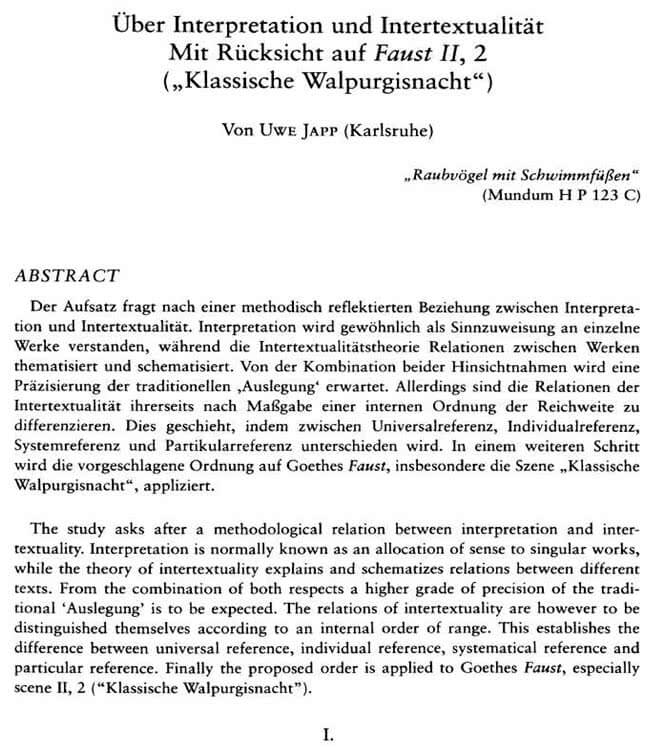

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

What Exactly is an Abstract, and How Do I Write One?

An abstract is a short summary of your completed research. It is intended to describe your work without going into great detail. Abstracts should be self-contained and concise, explaining your work as briefly and clearly as possible. Different disciplines call for slightly different approaches to abstracts, as will be illustrated by the examples below, so it would be wise to study some abstracts from your own field before you begin to write one.

General Considerations

Probably the most important function of an abstract is to help a reader decide if he or she is interested in reading your entire publication. For instance, imagine that you’re an undergraduate student sitting in the library late on a Friday night. You’re tired, bored, and sick of looking up articles about the history of celery. The last thing you want to do is reading an entire article only to discover it contributes nothing to your argument. A good abstract can solve this problem by indicating to the reader if the work is likely to be meaningful to his or her particular research project. Additionally, abstracts are used to help libraries catalogue publications based on the keywords that appear in them.

An effective abstract will contain several key features:

- Motivation/problem statement: Why is your research/argument important? What practical, scientific, theoretical or artistic gap is your project filling?

- Methods/procedure/approach: What did you actually do to get your results? (e.g. analyzed 3 novels, completed a series of 5 oil paintings, interviewed 17 students)

- Results/findings/product: As a result of completing the above procedure, what did you learn/invent/create?

- Conclusion/implications: What are the larger implications of your findings, especially for the problem/gap identified previously? Why is this research valuable?

In Practice

Let’s take a look at some sample abstracts, and see where these components show up. To give you an idea of how the author meets these “requirements” of abstract writing, the various features have been color-coded to correspond with the numbers listed above. The general format of an abstract is largely predictable, with some discipline-based differences. One type of abstract not discussed here is the “Descriptive Abstract,” which only summarizes and explains existing research, rather than informing the reader of a new perspective. As you can imagine, such an abstract would omit certain components of our four-colored model.

SAMPLE ABSTRACTS

ABSTRACT #1: History / Social Science

"Their War": The Perspective of the South Vietnamese Military in Their Own Words Author: Julie Pham

Despite the vast research by Americans on the Vietnam War, little is known about the perspective of South Vietnamese military, officially called the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF). The overall image that emerges from the literature is negative: lazy, corrupt, unpatriotic, apathetic soldiers with poor fighting spirits. This study recovers some of the South Vietnamese military perspective for an American audience through qualititative interviews with 40 RVNAF veterans now living in San José, Sacramento, and Seattle, home to three of the top five largest Vietnamese American communities in the nation. An analysis of these interviews yields the veterans' own explanations that complicate and sometimes even challenge three widely held assumptions about the South Vietnamese military: 1) the RVNAF was rife with corruption at the top ranks, hurting the morale of the lower ranks; 2) racial relations between the South Vietnamese military and the Americans were tense and hostile; and 3) the RVNAF was apathetic in defending South Vietnam from communism. The stories add nuance to our understanding of who the South Vietnamese were in the Vietnam War. This study is part of a growing body of research on non-American perspectives of the war. In using a largely untapped source of Vietnamese history—oral histories with Vietnamese immigrants—this project will contribute to future research on similar topics.

That was a fairly basic abstract that allows us to examine its individual parts more thoroughly.

Motivation/problem statement: The author identifies that previous research has been done about the Vietnam War, but that it has failed to address the specific topic of South Vietnam’s military. This is good because it shows how the author’s research fits into the bigger picture. It isn’t a bad thing to be critical of other research, but be respectful from an academic standpoint (i.e. “Previous researchers are stupid and don’t know what they’re talking about” sounds kind of unprofessional).

Methods/procedure/approach: The author does a good job of explaining how she performed her research, without giving unnecessary detail. Noting that she conducted qualitative interviews with 40 subjects is significant, but she wisely does not explicitly state the kinds of questions asked during the interview, which would be excessive.

Results/findings/product: The results make good use of numbering to clearly indicate what was ascertained from the research—particularly useful, as people often just scan abstracts for the results of an experiment.

Conclusion/implications: Since this paper is historical in nature, its findings may be hard to extrapolate to modern-day phenomena, but the author identifies the importance of her work as part of a growing body of research, which merits further investigation. This strategy functions to encourage future research on the topic.

ABSTRACT #2: Natural Science “A Lysimeter Study of Grass Cover and Water Table Depth Effects on Pesticide Residues in Drainage Water” Authors: A. Liaghat, S.O. Prasher

A study was undertaken to investigate the effect of soil and grass cover, when integrated with water table management (subsurface drainage and controlled drainage), in reducing herbicide residues in agricultural drainage water. Twelve PVC lysimeters, 1 m long and 450 mm diameter, were packed with a sandy soil and used to study the following four treatments: subsurface drainage, controlled drainage, grass (sod) cover, and bare soil. Contaminated water containing atrazine, metolachlor, and metribuzin residues was applied to the lysimeters and samples of drain effluent were collected. Significant reductions in pesticide concentrations were found in all treatments. In the first year, herbicide levels were reduced significantly (1% level), from an average of 250 mg/L to less than 10 mg/L . In the second year, polluted water of 50 mg/L, which is considered more realistic and reasonable in natural drainage waters, was applied to the lysimeters and herbicide residues in the drainage waters were reduced to less than 1 mg/L. The subsurface drainage lysimeters covered with grass proved to be the most effective treatment system.

Motivation/problem statement: Once again, we see that the problem—more like subject of study —is stated first in the abstract. This is normal for abstracts, in that you want to include the most important information first. The results may seem like the most important part of the abstract, but without mentioning the subject, the results won’t make much sense to readers. Notice that the abstract makes no references to other research, which is fine. It is not obligatory to cite other publications in an abstract, and in fact, doing so might distract your reader from YOUR experiment. Either way, it is likely that other sources will surface in your paper’s discussion/conclusion.

Methods/procedure/approach: Notice that the authors include pertinent numbers and figures in describing their methods. An extended description of the methods would probably include a long list of numerical values and conditions for each experimental trial, so it is important to include only the most important values in your abstract—ones that might make your study unique. Additionally, we see that a methodological description appears in two different parts of the abstract. This is fine. It may work better to explain your experiment by more closely connecting each method to its result. One last point: the author doesn’t take time to define—or give any background information about—“atrazine,” “metalachlor,” “lysimeter,” or “metribuzin.” This may be because other ecologists know what these are, but even if that’s not the case, you shouldn’t take time to define terms in your abstract.

Results/findings/product: Similar to the methods component of the abstract, you want to condense your findings to include only the major result of the experiment. Again, this study focused on two major trials, so both trials and both major results are listed. A particularly important word to consider when sharing results in an abstract is “significant.” In statistics, “significant” means roughly that your results were not due to chance. In your paper, your results may be hundreds of words long, and involve dozens of tables and graphs, but ultimately, your reader only wants to know: “What was the main result, and was that result significant?” So, try to answer both these questions in the abstract.

Conclusion/implications: This abstract’s conclusion sounds more like a result: “…lysimeters covered with grass were found to be the most effective treatment system.” This may seem incomplete, since it does not explain how this system could/should/would be applied to other situations, but that’s okay. There is plenty of space for addressing those issues in the body of the paper.

ABSTRACT #3: Philosophy / Literature [Note: Many papers don’t precisely follow the previous format, since they do not involve an experiment and its methods. Nonetheless, they typically rely on a similar structure.]

“Participatory Legitimation: A Reply to Arash Abizadeh” Author: Eric Schmidt, Louisiana State University, 2011

Arash Abizadeh’s argument against unilateral border control relies on his unbounded demos thesis, which is supported negatively by arguing that the ‘bounded demos thesis’ is incoherent. The incoherency arises for two reasons: (1) Democratic principles cannot be brought to bear on matters (border control) logically prior to the constitution of a group, and (2), the civic definition of citizens and non-citizens creates an ‘externality problem’ because the act of definition is an exercise of coercive power over all persons. The bounded demos thesis is rejected because the “will of the people” fails to legitimate democratic political order because there can be no pre-political political will of the people. However, I argue that “the will of the people” can be made manifest under a robust understanding of participatory legitimation, which exists concurrently with the political state, and thus defines both its borders and citizens as bounded , rescuing the bounded demos thesis and compromising the rest of Abizadeh’s article.

This paper may not make any sense to someone not studying philosophy, or not having read the text being critiqued. However, we can still see where the author separates the different components of the abstract, even if we don’t understand the terminology used.

Motivation/problem statement: The problem is not really a problem, but rather another person’s belief on a subject matter. For that reason, the author takes time to carefully explain the exact theory that he will be arguing against.

Methods/procedure/approach: [Note that there is no traditional “Methods” component of this abstract.] Reviews like this are purely critical and don’t necessarily involve performing experiments as in the other abstracts we have seen. Still, a paper like this may incorporate ideas from other sources, much like our traditional definition of experimental research.

Results/findings/product: In a paper like this, the “findings” tend to resemble what you have concluded about something, which will largely be based on your own opinion, supported by various examples. For that reason, the finding of this paper is: “The ‘will of the people,’ actually corresponds to a ‘bounded demos thesis.’” Even though we aren’t sure what the terms mean, we can plainly see that the finding (argument) is in support of “bounded,” rather than “unbounded.”

Conclusion/implications: If our finding is that “bounded” is correct, then what should we conclude? [In this case, the conclusion is simply that the initial author, A.A., is wrong.] Some critical papers attempt to broaden the conclusion to show something outside the scope of the paper. For example, if A.A. believes his “unbounded demos thesis” to be correct (when he is actually mistaken), what does this say about him? About his philosophy? About society as a whole? Maybe people who agree with him are more likely to vote Democrat, more likely to approve of certain immigration policies, more likely to own Labrador retrievers as pets, etc.

Applying These Skills

Now that you know the general layout of an abstract, here are some tips to keep in mind as you write your own:

1. The abstract stands alone

- An abstract shouldn’t be considered “part” of a paper—it should be able to stand independently and still tell the reader something significant.

2. Keep it short

- A general rule of abstract length is 200-300 words, or about 1/10th of the entire paper.

3. Don’t add new information

- If something doesn’t appear in your actual paper, then don’t put it in the abstract.

4. Be consistent with voice, tone, and style

- Try to write the abstract in the same style as your paper (i.e. If you’re not using contractions in your paper, the do not use them in your abstract).

5. Be concise

- Try to shorten your sentences as often as possible. If you can say something clearly in five words rather than ten, then do it.

6. Break up its components

- If allowed, subdivide the components of your abstract with bolded headings for “Background,” “Methods,” etc.

7. The abstract should be part of your writing process

- Consider writing your abstract after you finish your entire paper.

- There’s nothing wrong with copying and pasting important sentences and phrases from your paper … provided that they’re your own words.

- Write multiple drafts, and keep revising. An abstract is very important to your publication (or assignment) and should be treated as such.

"Abstracts." The Writing Center. The University of North Carolina, n.d. Web. 1 Jun 2011. http://www.unc.edu/depts/wcweb/handouts/abstracts.html "Abstracts." The Writing Center. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, n.d. Web. 1 Jun 2011. http://www.rpi.edu/web/writingcenter/abstracts.html

Last updated August 2013

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to draft his manuscript. After completing the abstract, he proceeds to write the introduction. That’s when he pauses in confusion. Do the abstract and introduction mean the same? How is the content for both the sections different?

This is a dilemma faced by several young researchers while drafting their first manuscript. An abstract is similar to a summary except that it is more concise and direct. Whereas, the introduction section of your paper is more detailed. It states why you conducted your study, what you wanted to accomplish, and what is your hypothesis.

This blog will allow us to learn more about the difference between the abstract and the introduction.

What Is an Abstract for a Research Paper?

An abstract provides the reader with a clear description of your research study and its results without the reader having to read the entire paper. The details of a study, such as precise methods and measurements, are not necessarily mentioned in the abstract. The abstract is an important tool for researchers who must sift through hundreds of papers from their field of study.

The abstract holds more significance in articles without open access. Reading the abstract would give an idea of the articles, which would otherwise require monetary payment for access. In most cases, reviewers will read the abstract to decide whether to continue to review the paper, which is important for you.

Your abstract should begin with a background or objective to clearly state why the research was done, its importance to the field of study, and any previous roadblocks encountered. It should include a very concise version of your methods, results, and conclusions but no references. It must be brief while still providing enough information so that the reader need not read the full article. Most journals ask that the abstract be no more than 200–250 words long.

Format of an Abstract

There are two general formats — structured and unstructured. A structured abstract helps the reader find pertinent information very quickly. It is divided into sections clearly defined by headings as follows:

- Background : Latest information on the topic; key phrases that pique interest (e.g., “…the role of this enzyme has never been clearly understood”).

- Objective : The research goals; what the study examined and why.

- Methods : Brief description of the study (e.g., retrospective study).

- Results : Findings and observations.

- Conclusions : Were these results expected? Whether more research is needed or not?

Authors get tempted to write too much in an abstract but it is helpful to remember that there is usually a maximum word count. The main point is to relay the important aspects of the study without sharing too many details so that the readers do not have to go through the entire manuscript text for finding more information.

The unstructured abstract is often used in fields of study that do not fall under the category of science. This type of abstracts does not have different sections. It summarizes the manuscript’s objectives, methods, etc., in one paragraph.

Related: Create an impressive manuscript with a compelling abstract. Check out these resources and improve your abstract writing process!

Lastly, you must check the author guidelines of the target journal. It will describe the format required and the maximum word count of your abstract.

What Is an Introduction?

Your introduction is the first section of your research paper . It is not a repetition of the abstract. It does not provide data about methods, results, or conclusions. However, it provides more in-depth information on the background of the subject matter. It also explains your hypothesis , what you attempted to discover, or issues that you wanted to resolve. The introduction will also explain if and why your study is new in the subject field and why it is important.

It is often a good idea to wait until the rest of the paper is completed before drafting your introduction. This will help you to stay focused on the manuscript’s important points. The introduction, unlike the abstract, should contain citations to references. The information will help guide your readers through the rest of your document. The key tips for writing an effective introduction :

- Beginning: The importance of the study.

- Tone/Tense: Formal, impersonal; present tense.

- Content: Brief description of manuscript but without results and conclusions.

- Length: Generally up to four paragraphs. May vary slightly with journal guidelines.

Once you are sure that possible doubts on the difference between the abstract and introduction are clear, review and submit your manuscript.

What struggles have you had in writing an abstract or introduction? Were you able to resolve them? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section below.

Insightful and educating Indeed. Thank You

Quite a helpful and precise for scholars and students alike. Keep it up…

thanks! very helpful.

thanks. helped

Greeting from Enago Academy! Thank you for your positive comment. We are glad to know that you found our resources useful. Your feedback is very valuable to us. Happy reading!

Really helpful as I prepare to write the introduction to my dissertation. Thank you Enago Academy

This gave me more detail finding the pieces of a research article being used for a critique paper in nursing school! thank you!

The guidelines have really assisted me with my assignment on writing argument essay on social media. The difference between the abstract and introduction is quite clear now for me to start my essay…thank you so much…

Quite helpful! I’m writing a paper on eyewitness testimony for one of my undergraduate courses at the University of Northern Colorado, and found this to be extremely helpful in clarifications

This was hugely helpful. Keep up the great work!

This was quite helpful. Keep it up!

Very comprehensive and simple. thanks

As a student, this website has helped me greatly to understand how to formally report my research

Thanks a lot.I can now handle my doubts after reading through.

thanks alot! this website has given me huge clarification on writing a good Introduction and Abttract i really appreciate what you share!. hope to see more to come1 God bless you.

Thank you, this was very helpful for writing my research paper!

That was helpful. geed job.

Thank you very much. This article really helped with my assignment.

Woohoo! Amazing. I couldnt stop listening to the audio; so enlightening.

Thank you for such a clear breakdown!

I am grateful for the assistance rendered me. I was mystified over the difference between an abstract and introduction during thesis writing. Now I have understood the concept theoretically, I will put that in practice. So thanks a lots it is great help to me.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

如何准备高质量的金融和科技领域学术论文

如何寻找原创研究课题 快速定位目标文献的有效搜索策略 如何根据期刊指南准备手稿的对应部分 论文手稿语言润色实用技巧分享

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Annex Vs. Appendix: Do You Know the Difference?

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Manuscript Preparation

Differentiating between the abstract and the introduction of a research paper

- 3 minute read

- 49.7K views

Table of Contents

While writing a manuscript for the first time, you might find yourself confused about the differences between an abstract and the introduction. Both are adjacent sections of a research paper and share certain elements. However, they serve entirely different purposes. So, how does one ensure that these sections are written correctly?

Knowing the intended purpose of the abstract and the introduction is a good start!

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a very short summary of all the sections of your research paper—the introduction, objectives, materials and methods, results, and conclusion. It ends by emphasising the novelty or relevance of your study, or by posing questions for future research. The abstract should cover all important aspects of the study, so that the reader can quickly decide if the paper is of their interest or not.

In simple terms, just like a restaurant’s menu that provides an overview of all available dishes, an abstract gives the reader an idea of what the research paper has to offer. Most journals have a strict word limit for abstracts, which is usually 10% of the research paper.

What is the purpose of an abstract?

The abstract should ideally induce curiosity in the reader’s mind and contain strategic keywords. By generating curiosity and interest, an abstract can push readers to read the entire paper or buy it if it is behind a paywall. By using keywords strategically in the abstract, authors can improve the chances of their paper appearing in online searches.

What is an introduction?

The introduction is the first section in a research paper after the abstract, which describes in detail the background information that is necessary for the reader to understand the topic and aim of the study.

What is the purpose of an introduction?

The introduction points to specific gaps in knowledge and explains how the study addresses these gaps. It lists previous studies in a chronological order, complete with citations, to explain why the study was warranted.

A good introduction sets the context for your study and clearly distinguishes between the knowns and the unknowns in a research topic.

Often, the introduction mentions the materials and methods used in a study and outlines the hypotheses tested. Both the abstract and the introduction have this in common. So, what are the key differences between the two sections?

Key differences between an abstract and the introduction:

- The word limit for an abstract is usually 250 words or less. In contrast, the typical word limit for an introduction is 500 words or more.

- When writing the abstract, it is essential to use keywords to make the paper more visible to search engines. This is not a significant concern when writing the introduction.

- The abstract features a summary of the results and conclusions of your study, while the introduction does not. The abstract, unlike the introduction, may also suggest future directions for research.

- While a short review of previous research features in both the abstract and the introduction, it is more elaborate in the latter.

- All references to previous research in the introduction come with citations. The abstract does not mention specific studies, although it may briefly outline previous research.

- The abstract always comes before the introduction in a research paper.

- Every paper does not need an abstract. However, an introduction is an essential component of all research papers.

If you are still confused about how to write the abstract and the introduction of your research paper while accounting for the differences between them, head over to Elsevier Author Services . Our experts will be happy to guide you throughout your research journey, with useful advice on how to write high quality research papers and get them published in reputed journals!

- Research Process

Scholarly Sources: What are They and Where can You Find Them?

What are Implications in Research?

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.

Background or Introduction – What is currently known? Start with a brief, 2 or 3 sentence, introduction to the research area.

Objectives or Aims – What is the study and why did you do it? Clearly state the research question you’re trying to answer.

Methods – What did you do? Explain what you did and how you did it. Include important information about your methods, but avoid the low-level specifics. Some disciplines have specific requirements for abstract methods.

- CONSORT for randomized trials.

- STROBE for observational studies

- PRISMA for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Results – What did you find? Briefly give the key findings of your study. Include key numeric data (including confidence intervals or p values), where possible.

Conclusions – What did you conclude? Tell the reader why your findings matter, and what this could mean for the ‘bigger picture’ of this area of research.

Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND convering all the information you need to.

- Keep it concise and to the point. Most journals have a maximum word count, so check guidelines before you write the abstract to save time editing it later.

- Write for your audience. Are they specialists in your specific field? Are they cross-disciplinary? Are they non-specialists? If you’re writing for a general audience, or your research could be of interest to the public keep your language as straightforward as possible. If you’re writing in English, do remember that not all of your readers will necessarily be native English speakers.

- Focus on key results, conclusions and take home messages.

- Write your paper first, then create the abstract as a summary.

- Check the journal requirements before you write your abstract, eg. required subheadings.

- Include keywords or phrases to help readers search for your work in indexing databases like PubMed or Google Scholar.

- Double and triple check your abstract for spelling and grammar errors. These kind of errors can give potential reviewers the impression that your research isn’t sound, and can make it easier to find reviewers who accept the invitation to review your manuscript. Your abstract should be a taste of what is to come in the rest of your article.

Don’t

- Sensationalize your research.

- Speculate about where this research might lead in the future.

- Use abbreviations or acronyms (unless absolutely necessary or unless they’re widely known, eg. DNA).

- Repeat yourself unnecessarily, eg. “Methods: We used X technique. Results: Using X technique, we found…”

- Contradict anything in the rest of your manuscript.

- Include content that isn’t also covered in the main manuscript.

- Include citations or references.

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Abstract vs Introduction – Differences Explained

- By Dr Harry Hothi

- August 29, 2020

Any academic write up of a research study or project will require the inclusion of an abstract and introduction. If you pick up any example of a research paper for a journal, dissertation for a Masters degree or a PhD thesis, you’ll see the abstract, followed by the introduction. At first glance you’ll notice that the abstract is much shorter in length, typically a quarter or third of a page of A4. The introduction on the other hand is longer, taking up at least an entire page of writing.

Beyond the length, what are the differences in the content of the two sections? In short, the abstract is a summary of the entire study, describing the context, research aim, methods, results and key conclusions. The introduction gives more detail on the background of the subject area, the motivation for the study and states the aims and objectives.

Read on to learn more.

What is an Abstract?

The main purpose of an abstract is to succinctly give the reader an overview of why the study was needed, what the purpose of the project was, the research question, the key materials and methods that were used, the main results and what conclusions were drawn from this. Many abstracts also conclude with a sentence on the significance or impact of the research. These are sometimes also referred to as an executive summary.

The reader should have an understanding of the paper topic and what the study was about from the abstract alone. He or she can then decide if they want to read the paper or thesis in more detail.

Abstracts are particularly useful for researchers performing a literature review, which involves critically evaluating a large number of papers. Reading the abstract enables them to quickly ascertain the key points of a paper, helping them identify which ones to read in full.

Abstracts are also very important for learning more about the work performed in papers that are hidden behind academic journal paywalls (i.e. those that are not open access). Abstracts are always made freely available, allowing a researcher to understand the context and main point of the work and then decide if it’s worth paying to read the entire paper. These are sometimes referred to as the ‘de facto introduction’ to the research work as it’s usually the first section people read about your study, after the title page.

How do you Write an Abstract?

The majority of academic journals place a limit of 250 words on the length of the abstract in papers submitted to them. They do this to ensure you give a quick overview of only the most important information from your study, helping the reader decide if they want to read the whole paper too. Make sure you double check the specific requirements of your target journal before you start writing.

Universities or other academic institutions often allow up to 500 words for an abstract written for a doctoral thesis.

Abstracts can be either structured or unstructured in the way they are formatted. A structured abstract contains separate headings to guide the reader through the study. Virtually all STEM journals will require this format be used for a researcharticle. The exact names used for each heading can differ but generally there are defined as:

- Background. This is also sometimes called the Introduction. This section should give an overview of what is currently known about the research topic and what the gap in knowledge is. The reader should understand the problem your research will address; i.e. what was your study needed. Don’t include any references or citations in the abstract.

- Aim and Objective. Give a brief explanation of what the study intended to achieve and state the research question or questions that you proposed. Some authors also include the hypothesis here too.

- Materials and Methods. Use the methods section to describe what you investigated, what the study design was and how you carried it out.

- Results. Give an overview of your key findings.

- Discussion and Conclusion. Some journals may ask for these two terms to be used as separated headings. These sections explain why you may have obtained the results that you did, what this means and what the significance or impact of this might be.

An informative abstract should provide a concise summary of all the important points in your research project, including what the central question relating to the subject matter was. Make it interesting to read too; this may be the difference between your abstract being accepted or rejected if you decide to submit it to an upcoming conference. Reviewers for large conferences often have to read hundreds of abstracts so make sure yours stands out by being easy to read and follow.

It’s less common that you’ll be asked to write an unstructured abstract. If you are, however, be aware that the key difference is that an unstructured abstract does not include separate headings. The flow of the abstract text should still follow the 5 points listed above but they should all be written within one long paragraph.

What is the Introduction?

The introduction section is the first main written work presented after the abstract in your paper manuscript or thesis. In a research paper, the introduction will be followed by a section on the materials and methods. In thesis writing, the introduction will be followed by the literature review .

The main aim of introduction writing is to give the reader more detail on the background information of the study. It should include a brief description of the key current knowledge that exists based on the work presented in previous literature and where the gaps in knowledge are. The introduction should convey why your research was needed in order to add new understanding to your subject area. Make sure that you reference all the publications that you refer to.

When writing an introduction for a scientific paper you should also include the aim of your study and the research objectives/questions. If relevant, also include your hypothesis or (null hypothesis).

How do you Structure the Introduction?

The general rule of thumb for a research paper is to use size 12 Times New Roman font, double spaced. Write four separate paragraphs which together are no longer than one page in length. Structure the four paragraphs as follows:

- Set the context of the research study, giving background information about the subject area.

- Describe what is currently know from previously published work and what is poorly understood – i.e. the research gap.

- Explain how addressing this gap in knowledge is important for your research field – i.e. why this study is needed.

- Give a broad overview of the aims, objectives and hypothesis of the study.

You should not describe the research method used in this section nor any results and conclusions.

You should be clear now on what the differences between an abstract vs introduction are. The best way to improve your academic writing skills for these are to read other examples from other research articles and start writing!

The title page of your dissertation or thesis conveys all the essential details about your project. This guide helps you format it in the correct way.

Tenure is a permanent position awarded to professors showing excellence in research and teaching. Find out more about the competitive position!

In this post you’ll learn what the significance of the study means, why it’s important, where and how to write one in your paper or thesis with an example.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

The scope and delimitations of a thesis, dissertation or paper define the topic and boundaries of a research problem – learn how to form them.

A concept paper is a short document written by a researcher before starting their research project, explaining what the study is about, why it is needed and the methods that will be used.

Dr Nikolov gained his PhD in the area of Anthropology of Architecture from UCL in 2020. He is a video journalist working with Mashable and advises PhDs consider options outside of academia.

Elmira is in the third year of her PhD program at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology; Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, researching the mechanisms of acute myeloid leukemia cells resistance to targeted therapy.

Join Thousands of Students

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

How To Write An Abstract

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Definition: Abstract

- 4 Abstract in Different Languages

- 5 Abstract vs. Conclusion

- 6 In a Nutshell

Definition: Abstract

An abstract is a short summary of a research paper. It is not part of the actual text and must be included at the very beginning of your work. It does not show up in the structure and the table of contents of your thesis.

You write an abstract to give a brief account of the most important information relating to the research background, structure, method, data analysis, and results of your research paper. The abstract should not create suspense: Making it very clear early on what your results are will help the reader evaluate the relevance of your paper.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a short summary written at the beginning of a research paper . It highlights the main ideas of your academic project. Your research methods, data analysis, results plus any background information relating to your research should be included in the abstract.

Why do I need an abstract?

An abstract is nescessary, as it helps the reader to decide whether the results and methods of a particular paper are relevant to them or whether it is worthwhile for them to read the whole paper. It effectively creates the first impression of the thesis or essay. It is also very useful for fellow researchers in the academic community, as they can decide upon first glance whether or not the paper can be useful or relevant to their personal research project.

Where does the abstract belong?

The abstract is to be put at the beginning of your writing project. It should appear between the title page and the table of contents page of the research paper. If you’re writing a thesis with an acknowledgements page, then the abstract is placed after the acknowledgements.

When do I write the abstract?

The abstract should be the very last thing you write during the academic writing process. This is because it is only possible to come up with a precise summary of your work once you have written the whole research paper . Using this same logic, the conclusion should also be one of the very last paragraphs that you write.

How long should an abstract be?

The abstract should be between one third of a page and one full page in length. However, this depends on the length of the paper that you’re writing. For a smaller research paper, 100 words is sufficient. For a bachelor’s thesis, or a master’s thesis, the abstract should be between 1 or 2 pages. But it should definitely not exceed 2 pages!

Tip: Take a look at some abstract examples for inspiration!

What is included in an abstract?

A top-quality abstract will include a brief explanation of the following aspects:

1. Background and purpose 2. Overarching research question 3. Gap in literature and methods used to address the gap in literature 4. Main results of the writing project 5. Interpretation or conclusion of the thesis statement Each of these points should be addressed in only a few sentences.

Is an abstract international?

It doesn’t matter which language you write your abstract in, an English translation of your abstract is often required. The reason for this is so that the results of your research paper can be reviewed by an international audience.

Also useful: What is plagiarism?

How to Write an Abstract: The Content

There is one thing you must understand about how to write an abstract:

The abstract should contain important aspects of the paper, like the

- research question ,

- limitations,

- study design,

- main results,

- main idea or message,

- key interpretations,

- implications,

- and validity (cf. Schnur 2005, as quoted in Theisen 2013: 101).

How to Write an Abstract: Structure

The abstract follows the same structure as your paper:

(cf. Kruse 2007: 186)

How to Write an Abstract: Goal

“An abstract is a very precise summary of your whole paper”

You might have heard the term ‘summary’ referring to an abstract of a research paper (cf. Oertner, St. John, & Thelen 2014: 93). However, do not make the mistake of assuming that an abstract is something rather general. You would be on the wrong track. When asked to write an abstract for your bachelor’s or master’s thesis, you are expected to deliver a very precise summary of your whole paper.

An abstract’s right to exist is founded in its purpose of helping a potential reader to quickly find out if it is worthwhile to read the whole paper (cf. Rossig & Prätsch 2005: 89). For this reason, an abstract has to offer everything the reader needs in order to evaluate the relevance of a research paper for their own work. It is the ultimate way of advertising your research.

You can save yourself a lot of work and trouble if you concentrate on reading the abstracts of published papers first; most papers these days provide abstracts (cf. Oertner, St. John, & Thelen 2014: 80). If you take your time to thoroughly read the abstracts, you will be able to judge whether a particular article will help you to support your line of argumentation. If not, then just move on the next article. You can check out the sample abstracts in this blog entry to get a better idea of how to write an abstract and what an abstract looks like.

“Through reading an abstract, you can find out if a paper arouses your interest or is relevant for your studies.”

How to Write an Abstract: Length

An abstract is a summary of a publication or an article on one third of a DIN-A4 page (cf. Kruse 2007: 185). Stickel-Wolf & Wolf provide a rough guideline for the word count: They say that an abstract should not contain more than 100 words (cf. 2013: 249).

Note: Generally speaking, an abstract for a bachelor’s or master’s thesis should not exceed one page, and the absolute maximum is two pages (cf. Rossig & Prätsch 2005: 89). The reason for this is self-explanatory: The purpose of the abstract is to offer a quick overview of, for example, a 60- or 80-page paper.

Abstract Example 1: English abstract addressing the main points of your paper

Abstract Example 2: English abstract of a master’s thesis with keywords

Recommended: Harvard Referencing

When to Write the Abstract and Where to Put It

You are probably wondering where the abstract should be placed in your research paper: at the beginning or towards the end? It is common to include the abstract right at the beginning (cf. Rossig & Prätsch 2005: 89; Samac, Prenner, & Schwetz 2009: 56). As we have established, it is a helpful tool for the reader to get an overview of the whole paper as early as possible. It is good to know what will follow. So, it would not be logical to put it at the end, right? Stickel-Wolf and Wolf recommend embedding the abstract in between the title page and the table of contents (cf. 2013: 249).

The next question about ‘How to write an abstract’ is a bit trickier. When is the right time to write the abstract? Given that it is to be added at the very beginning, before the actual text, you might think it is the first thing you are supposed to write. However, you will not be able to write a clear-cut and precise summary at a stage when you do not even know what you are summarizing. Therefore, you can only write the abstract after you have written the whole paper. How else would you know enough about your results to give a complete record of your whole work (cf. Rossig & Prätsch 2005: 89)?

Note: You can draw essential information to write your abstract from your conclusion, as this part briefly repeats the research questions and provides an evaluative summary of the results (cf. Stickel-Wolf 2013: 249).

Abstract in Different Languages