How to Distinguish between Social Thinking Skills and Constructive Thinking Skills

Let’s look at how to distinguish between social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills:

Thinking skills are fundamental cognitive processes that enable individuals to process information, make decisions, solve problems, and create new ideas. Among these skills, social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills stand out, each serving different functions and purposes. This article will explore the distinctions between social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills, providing examples and insights within a South African context suitable for high school learners.

Table of Contents

Distinguishing Between Social Thinking Skills and Constructive Thinking Skills

Distinguishing factors between social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills lie in their primary functions and applications. Social thinking skills focus on understanding and interpreting social situations, human interactions, and emotions. They involve empathy, communication, conflict resolution, and cultural awareness, and are essential for building relationships and working in teams. On the other hand, constructive thinking skills concentrate on critical analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of information. These include critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, and analytical thinking, aimed at creating new understandings or solutions by building on existing knowledge. While social thinking skills are directed towards human connections and shared understanding, constructive thinking skills are more concerned with logical reasoning, innovation, and intellectual development.

Social Thinking Skills

Definition and function.

Social thinking skills refer to the ability to understand and interpret social situations, human interactions, and emotions. These skills are vital in building relationships, working in teams, and navigating complex social landscapes.

Key Components

- Empathy : Understanding others’ feelings and responding compassionately.

- Communication : Expressing thoughts and emotions effectively.

- Conflict Resolution : Finding solutions to disagreements in a peaceful manner.

- Cultural Awareness : Recognizing and respecting different cultural norms and values.

In a diverse classroom setting, social thinking skills enable students to understand and appreciate the unique perspectives of their classmates, promoting tolerance and collaboration.

Constructive Thinking Skills

Constructive thinking skills involve the ability to critically analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information to create new understanding or solutions. It’s about building on existing knowledge to reach new conclusions or innovate.

- Critical Thinking : Analyzing and evaluating information or arguments.

- Problem-Solving : Finding solutions to complex problems through logical reasoning.

- Creativity : Using imagination to develop new ideas or solutions.

- Analytical Thinking : Breaking down complex information into understandable parts.

In a science project, students may apply constructive thinking skills to analyze data, draw conclusions, and create a new experiment or model based on their findings.

While social thinking skills are geared towards understanding and navigating human interactions, emotions, and relationships, constructive thinking skills focus on logical reasoning, analysis, creativity, and problem-solving. Social thinking skills are more about connecting with others and building a shared understanding, while constructive thinking skills are more about creating, analyzing, and synthesizing information.

Social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills are vital cognitive tools that serve different yet complementary functions. Social thinking is about empathizing, communicating, and working with others, whereas constructive thinking is about analyzing, creating, and problem-solving. Understanding these distinctions helps in applying the right skill set in various contexts, be it in personal relationships, educational pursuits, or professional environments. Recognizing and developing both sets of skills can lead to a more balanced and successful approach to life, particularly in a culturally diverse nation like South Africa.

No related posts found.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Igniting Brilliance, Inspiring Success with Regenesys. Enrol Now --> Enrol Now

Get Free Consultation

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms & Conditions.

The Difference Between Social Thinking Skills and Constructive Thinking Skills

Please rate this article

Join Regenesys’s 25+ Years Legacy

Awaken your potential.

In today’s dynamic field of leadership, where decisions shape destinies and strategies define success, distinguishing between social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills becomes paramount. These are not just mere cognitive abilities, but the very foundation upon which influential leaders build their legacies. In a world where 75% of long-term job success depends on soft skills, including social thinking, and where companies fostering creativity enjoy 1.5 times higher market share, the interplay of these thinking skills is more than just academic—it’s a strategic imperative.

In this exploration, we will delve deep into the fabric of these cognitive competencies, unravelling their definitions, distinguishing their unique attributes, and illustrating their real-world applications. As we navigate through this intellectual journey, we will uncover how leaders harness the power of social and constructive thinking to steer their teams towards uncharted territories of innovation and collaboration. Join us as we dissect the essence of these thinking skills and reveal their pivotal role in shaping the leaders of tomorrow.

What Are Constructive Thinking Skills?

Constructive thinking skills refer to the ability to analyse situations, make decisions, and solve problems in a positive and productive manner. It involves looking at challenges from different perspectives, generating creative solutions, and taking actionable steps to achieve desired outcomes.

Example of Constructive Thinking

Imagine you’re working on a project and encounter an unexpected obstacle. Instead of panicking or giving up, you use constructive thinking to brainstorm potential solutions, evaluate their feasibility, and implement the most effective one.

Constructive Thinking Skills: The Bedrock of Problem-Solving Leadership

Constructive thinking skills are the cornerstone of effective leadership. They enable leaders to approach challenges with a solution-oriented mindset, fostering an environment where innovation thrives. According to the World Economic Forum , “analytical thinking, creativity, and flexibility will be among the most sought-after skills” by 2025, yet few companies invest in such training.

In the corporate world, leaders with strong constructive thinking skills can drive their organisations to new heights. They’re adept at strategic planning, risk management, and making informed decisions that propel business growth. For state leaders, constructive thinking is vital for policy formulation and governance. It aids in tackling national issues, from economic development to public health, with foresight and pragmatism.

How to Improve Constructive Thinking Skills

The realm of constructive thinking is an intellectual playground – a place where challenges morph into opportunities and solutions blossom from brainstorming sessions. But fear not, intrepid thinker! Here are some key armaments in your constructive thinking arsenal:

- The Questioning Cutlass: Sharpen your curiosity! Don’t just accept problems at face value. Become a relentless questioner, dissecting the issue from multiple angles. Why? How? What if? These potent questions are the blades that carve a path to deeper understanding.

- The Brainstorming Broadsword: Unleash your creativity! Embrace the power of brainstorming. Jot down every possible solution, no matter how wacky it might seem. Often, the most outlandish ideas can spark the genesis of truly innovative solutions.

- The Information Shield: Knowledge is power! Gather as much information as possible about the problem. Research, interview experts, and consult relevant data. This information shield protects you from making decisions based on assumptions or biases.

- The Prioritisation Pike: Organise your thoughts! Once you have a quiver full of potential solutions, prioritise them ruthlessly. Weigh the pros and cons, assess feasibility, and identify the course of action with the highest chance of success.

Constructive Thinking Challenges

Even the most seasoned problem-solver can encounter perplexing roadblocks:

- The Confirmation Bias Conundrum: Our brains have a natural tendency to favour information that confirms our existing beliefs. This can lead us to overlook alternative solutions or crucial details. Be mindful of this bias and actively seek out diverse viewpoints.

- The Analysis Paralysis Pitfall: Sometimes, overthinking can be a real brain drain. While thorough analysis is important, getting stuck in an endless loop of “what ifs” can hinder progress. Set a time limit for analysis and learn to make decisions with the information you have.

- The Fear of Failure Fog: The fear of making the wrong choice can be paralysing. Remember, failure is an inevitable part of the learning process. Embrace calculated risks, learn from mistakes, and use them as stepping stones to success.

Activities to Improve Your Constructive Thinking

Just like any skill, constructive thinking can be honed and improved through practice. Here are some activities to sharpen your problem-solving prowess:

- Logical Puzzles & Brainteasers: These mental gymnastics challenges, stretch your thinking muscles and help you approach problems from unconventional angles.

- Debates & Discussions: Engage in healthy debate! Discussing opposing viewpoints forces you to think critically, analyse arguments, and refine your own solutions.

- The “What If?” Game: Challenge yourself to think outside the box. Take a current event or situation and brainstorm all the “what if” scenarios and potential solutions.

By incorporating these activities into your routine, you’ll be well on your way to becoming a constructive thinking mastermind! Remember, the journey to becoming a problem-solving savant is an ongoing adventure. Embrace the perplexity, celebrate your breakthroughs, and most importantly, never stop sharpening your intellectual arsenal!

What Are Social Thinking Skills?

Social thinking skills, on the other hand, relate to the ability to understand and interpret the thoughts, emotions, and intentions of others. It’s about recognising social cues, empathising with people, and navigating social interactions effectively.

Example of Social Thinking

In a team meeting, you notice a colleague seems upset. Using social thinking skills, you infer that they might be feeling left out of the conversation. You then make an effort to include them in the discussion, improving team dynamics.

Social Thinking Skills: The Essence of Relational Leadership

Social thinking skills are equally important for leaders. They facilitate the understanding of diverse perspectives and the building of strong relationships. According to a survey by LinkedIn , 92% of hiring managers consider soft skills, including social thinking, as important or more important than technical skills. However, 89% report difficulty in finding candidates with these attributes.

In a corporate setting, leaders with refined social thinking skills can cultivate a positive work culture. They excel in team building, conflict resolution, and employee engagement, leading to increased productivity and retention. For state leaders, social thinking is crucial for diplomacy and public relations. It enables them to connect with citizens, understand societal needs, and foster national unity.

How to Implement Social Thinking Skills

Imagine social interactions as a smorgasbord of intricate cues. Social thinking skills are your silver utensils, allowing you to navigate this delicious complexity. Here’s a taste of the key ingredients:

- Active Listening: This isn’t just about hearing words. It’s about becoming a symphony conductor, harmonizing with the speaker’s tone, body language, and unspoken emotions. Think furrowed brows, nervous laughter, or that barely-there smile – they’re all whispers waiting to be deciphered.

- Feedback Fanatic: Feedback can be a double-edged sword. But social thinking skills help you wield it with finesse. You can deliver constructive criticism that’s clear, specific, and delivered with a dash of empathy (think sugarcoating the pill, but without the sugar coma). On the flip side, you can also graciously receive feedback, transforming it into a springboard for self-improvement.

- Conflict Connoisseur: Disagreements are inevitable, but social thinking skills turn them into opportunities for growth. You become a master negotiator, adept at identifying underlying concerns, proposing win-win solutions, and navigating those oh-so-tricky emotional landmines.

- Social Cues Sleuth: Our social world is rife with nonverbal communication – a raised eyebrow, a playful nudge, or a tight-lipped silence. Social thinking skills equip you to become Sherlock Holmes of social situations, decoding these subtle cues and responding appropriately.

Social Thinking Challenges

While social thinking skills sound like superpowers, mastering them can be a perplexing journey. Here’s a peek at some roadblocks you might encounter:

- The Social Anxiety Labyrinth: Social anxiety can turn even the most basic interaction into a heart-pounding maze. Fear of judgment and negative evaluation can make it difficult to put yourself out there and hone social thinking skills.

- The Cultural Chameleon Conundrum : Navigating social situations across different cultures can be a dizzying experience. Understanding unspoken rules, greetings, and humour can vary greatly, leading to misunderstandings or awkward moments. It’s like trying to play a game with a different set of instructions for each person you meet.

- The Autism Enigma: For individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) , social cues can be like hieroglyphics on a Martian monument. Understanding facial expressions, body language, and unspoken rules can be a significant challenge.

Activities to Improve Social Skills

Don’t fret, intrepid explorers! There is a plethora of activities to sharpen your social thinking toolshed:

- Role-Playing Rendezvous: Step into the shoes of others! Role-playing allows you to rehearse social scenarios in a safe space, experiment with different approaches, and gain valuable feedback.

- Active Listening Bootcamp: Sharpen your ears and hone your focus! Active listening exercises train you to truly pay attention, ask clarifying questions, and acknowledge the speaker’s emotions.

- Social Group Sojourns: Immerse yourself in the social sphere! Join clubs, volunteer organisations, or online communities. This exposes you to diverse perspectives and provides fertile ground for practicing your social thinking skills.

By incorporating these activities into your life, you’ll be well on your way to becoming a social thinking savant! Remember, the journey to social mastery is a lifelong adventure. Embrace the perplexity, celebrate the bursts of progress, and most importantly, have fun along the way!

Distinguishing Between Constructive and Social Thinking Skills

While constructive thinking is centred around problem-solving and decision-making, social thinking focuses on interpersonal relationships and social awareness. Constructive thinking is often more analytical and task-oriented, whereas social thinking is more empathetic and relational.

The Intersection of Constructive and Social Thinking Skills

In real-life scenarios, constructive and social thinking skills often intersect. For instance, when addressing social injustices, one might use social thinking skills to understand the issues and the perspectives of those affected, and constructive thinking skills to devise and implement solutions.

The integration of constructive and social thinking skills is a potent combination for leaders. It equips them to address complex challenges with innovative solutions while maintaining strong connections with their teams and constituents.

For example, a CEO who uses constructive thinking to navigate market challenges while employing social thinking to maintain employee morale and stakeholder trust is more likely to lead a resilient and successful company. Another example would be a state leader who combines constructive thinking in policy development with social thinking in public communication, effectively lead a nation through crises and towards prosperity.

Embrace Social and Constructive Thinking for Leadership Excellence

In an era marked by rapid change and uncertainty, leaders who master both social and constructive thinking skills stand out. They are not only capable of devising strategic solutions but also adept at fostering collaboration and trust. As the demand for these skills continues to rise, investing in their development is not just advisable—it’s imperative for any leader aiming for excellence.

- Latest Posts

- Career Choices: Careers in Demand in 2024 - May 9, 2024

- Climate Change Progress in 2024: Embracing a New Paradigm in Environmental Responsibility - April 25, 2024

- The Need for Conscious Leadership - April 11, 2024

Thabiso Makekele

Content Writer | Regenesys Business School A dynamic Content Writer at Regenesys Business School. With a passion for SEO, social media, and captivating content, Thabiso brings a fresh perspective to the table. With a background in Industrial Engineering and a knack for staying updated with the latest trends, Thabiso is committed to enhancing businesses and improving lives.

Related Posts

Bbpress public forum.

Career Choices: Careers in Demand in 2024

Bbpress forum pending topic, write a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Explore Courses

- Digital Programmes

- Digital Regenesys

The Developing Learner

Social Constructivism: Vygotsky’s Theory

Like Piaget, Vygotsky acknowledged intrinsic development, but he argued that it is the language, writings, and concepts arising from the culture that elicit the highest level of cognitive thinking (Crain, 2005). He believed that social interactions with teachers and more learned peers could facilitate a learner’s potential for learning. Without this interpersonal instruction, he believed learners’ minds would not advance very far as their knowledge would be based only on their own discoveries.

Figure 3.7.1. Lev Vygotsky.

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

Vygotsky’s best-known concept is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD has been defined as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). Vygotsky stated that learners should be taught in the ZPD . A good teacher or more-knowledgable-other (MKO) identifies a learner’s ZPD and helps them stretch beyond it. Then the MKO gradually withdraws support until the learner can perform the task unaided. Other psychologists have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to Vygotsky’s theory. Scaffolding is the temporary support that an MKO gives a learner to do a task.

Figure 3.7.2. Model of Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development.

Thought and Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from another’s point of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud, referred to as private speech , speech meant only for one’s self. Eventually, thinking out loud becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).

Implications for Education

Vygotsky’s theories have been extremely influential for education. Although Vygotsky himself never mentioned the term scaffolding, it is often credited to him as a continuation of his ideas pertaining to the way adults or other children can use guidance in order for a child to work within their ZPD. (The term scaffolding was first developed by Jerome Bruner, David Wood, and Gail Ross while applying Vygotsky’s concept of ZPD to various educational contexts.)

Educators often apply these concepts by assigning tasks that students cannot do on their own, but which they can do with assistance; they should provide just enough assistance so that students learn to complete the tasks independently and then provide an environment that enables students to do harder tasks than would otherwise be possible. Teachers can also allow students with more knowledge to assist students who need more guidance. Especially in the context of collaborative learning, group members who have higher levels of understanding can help the less advanced members learn within their zone of proximal development.

Vygotsky’s Influence on Education

Video 3.7.1. Vygotsky’s Developmental Theory introduces the applications of the theory in the classroom.

Contrasting Piaget and Vygotsky

Piaget was highly critical of teacher-directed instruction believing that teachers who take control of the child’s learning place the child into a passive role (Crain, 2005). Further, teachers may present abstract ideas without the child’s true understanding, and instead, they just repeat back what they heard. Piaget believed children must be given opportunities to discover concepts on their own. As previously stated, Vygotsky did not believe children could reach a higher cognitive level without instruction from more learned individuals. Who is correct? Both theories certainly contribute to our understanding of how children learn.

Candela Citations

- Social Constructivism . Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/social-constructivism-vygotskys-theory/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Adolescent Psychology. Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/adolescent. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Vygotsky's Developmental Theory. Provided by : Davidson Films. Retrieved from : https://youtu.be/InzmZtHuZPY. License : All Rights Reserved

Educational Psychology Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Basics for GSIs

- Advancing Your Skills

Social Constructivism

The level of potential development is the level at which learning takes place. It comprises cognitive structures that are still in the process of maturing, but which can only mature under the guidance of or in collaboration with others.

Background View of Knowledge View of Learning View of Motivation Implications for Teaching Reference

Social constructivism is a variety of cognitive constructivism that emphasizes the collaborative nature of much learning. Social constructivism was developed by post-revolutionary Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky. Vygotsky was a cognitivist, but rejected the assumption made by cognitivists such as Piaget and Perry that it was possible to separate learning from its social context. He argued that all cognitive functions originate in (and must therefore be explained as products of) social interactions and that learning did not simply comprise the assimilation and accommodation of new knowledge by learners; it was the process by which learners were integrated into a knowledge community. According to Vygotsky (1978, 57),

View of Knowledge

Cognitivists such as Piaget and Perry see knowledge as actively constructed by learners in response to interactions with environmental stimuli. Vygotsky emphasized the role of language and culture in cognitive development. According to Vygotsky, language and culture play essential roles both in human intellectual development and in how humans perceive the world. Humans’ linguistic abilities enable them to overcome the natural limitations of their perceptual field by imposing culturally defined sense and meaning on the world. Language and culture are the frameworks through which humans experience, communicate, and understand reality. Vygotsky states (1968, 39),

Language and the conceptual schemes that are transmitted by means of language are essentially social phenomena. As a result, human cognitive structures are, Vygotsky believed, essentially socially constructed. Knowledge is not simply constructed, it is co-constructed.

View of Learning

Vygotsky accepted Piaget’s claim that learners respond not to external stimuli but to their interpretation of those stimuli. However, he argued that cognitivists such as Piaget had overlooked the essentially social nature of language. As a result, he claimed they had failed to understand that learning is a collaborative process. Vygotsky distinguished between two developmental levels (85):

View of Motivation

Whereas behavioral motivation is essentially extrinsic, a reaction to positive and negative reinforcements, cognitive motivation is essentially intrinsic — based on the learner’s internal drive. Social constructivists see motivation as both extrinsic and intrinsic. Because learning is essentially a social phenomenon, learners are partially motivated by rewards provided by the knowledge community. However, because knowledge is actively constructed by the learner, learning also depends to a significant extent on the learner’s internal drive to understand and promote the learning process.

Implications for Teaching

Collaborative learning methods require learners to develop teamwork skills and to see individual learning as essentially related to the success of group learning. The optimal size for group learning is four or five people. Since the average section size is ten to fifteen people, collaborative learning methods often require GSIs to break students into smaller groups, although discussion sections are essentially collaborative learning environments. For instance, in group investigations students may be split into groups that are then required to choose and research a topic from a limited area. They are then held responsible for researching the topic and presenting their findings to the class. More generally, collaborative learning should be seen as a process of peer interaction that is mediated and structured by the teacher. Discussion can be promoted by the presentation of specific concepts, problems, or scenarios; it is guided by means of effectively directed questions, the introduction and clarification of concepts and information, and references to previously learned material. Some more specific techniques are suggested in the Teaching Guide pages on Discussion Sections .

Vygotsky, Lev (1978). Mind in Society . London: Harvard University Press.

Using constructivism to train critical thinking skills

The names and groundbreaking work of Piaget, Vygotsky, and Dewey should be familiar to most educators, and for good reason: Their ideas on constructivist learning theory continue to shape education today. Constructivism is an active learning method that has many benefits — including opportunities to build students’ critical thinking skills .

So, let’s delve into constructivism and explore its benefits, including its role in fostering students’ critical thinking.

What is constructivism?

Imagine your students as construction workers. As their supervisor, do you provide them with the exact blueprint and building methods to ensure that students create identical structures? Or, do you guide students in using their own designs and methods, leading to a selection of unique buildings?

The second option represents constructivism. Students construct their own knowledge through discovery, experimentation, and interaction. Then, they assimilate and accommodate new information within their existing schemas. As a result, each student gains a unique set of knowledge and skills from every learning experience.

What are the origins of constructivism?

Psychologist Jean Piaget laid the foundations of constructivism . In contrast to the behaviorist theories of the time, Piaget viewed learning as an active process where learners develop knowledge by engaging with their environment. Students then connect this new information with prior experiences to construct cognitive schemas.

Similarly, Vygotsky also acknowledged the importance of connecting new and existing knowledge. However, his theory of social constructivism emphasized the social and cultural aspects of learning. He believed that learners build knowledge through interactions with others.

Finally, John Dewey’s interpretation combines these viewpoints, focusing on the importance of experiential learning and social interaction within a meaningful context.

How does constructivism build students’ critical thinking skills?

Critical thinking is a vital 21st-century skill for students to master. It describes the ability to analyze and evaluate information in order to make reasoned judgments . By employing constructivist principles in the classroom, educators can provide students with many opportunities to practice their critical thinking skills .

Let’s explore how you can use the main principles of constructivism to build students’ critical thinking skills.

Principle #1: Students construct knowledge independently to build critical thinking skills

In the constructivist classroom, educators encourage students to apply critical thinking skills to evaluate the reliability and credibility of information used to build knowledge.

When students judge the information to be useful, they analyze how to assimilate or accommodate it into their existing schemas. Thus, educators should design plenty of open-ended learning experiences for students to use their critical thinking skills to construct their own knowledge.

Principle #2: Students take responsibility for their own learning

Constructivism emphasizes students’ active engagement in the learning process. Giving students responsibility for their own learning motivates them to critically think about topics, constructing a deeper knowledge base.

Motivated students also practice their critical thinking skills by pursuing independent lines of inquiry, researching and evaluating additional sources of information , and designing creative solutions.

Principle #3: Students explore multiple perspectives through interaction with others

Constructivism promotes a collaborative learning environment , where students build knowledge together. Through sharing ideas and viewpoints, students learn to justify their thoughts with evidence.

As they encounter their peers’ diverse perspectives, they must critically evaluate how each idea connects to their own existing knowledge. This helps students consider multiple perspectives on topics, a core component of thinking critically.

Principle #4: Students use metacognition skills to reflect on the learning process

Engaging students in critical thinking through self-reflection and self-questioning maximizes the benefits of the constructivist approach. They learn to identify and address gaps in their own knowledge to help transfer their knowledge and skills to new contexts.

Students also learn to evaluate their progress toward personal goals and critically reflect on their own strengths and target areas. Armed with this information, students can adapt their learning strategies accordingly, as part of the continuous cycle of learning.

Principle #5: Students engage in meaningful learning experiences

The constructivist approach emphasizes the importance of students participating in authentic and relevant learning experiences. By immersing themselves in real-world projects, students deepen their learning and actively apply their critical thinking skills to plan and evaluate the most effective strategies for achieving the project’s objectives.

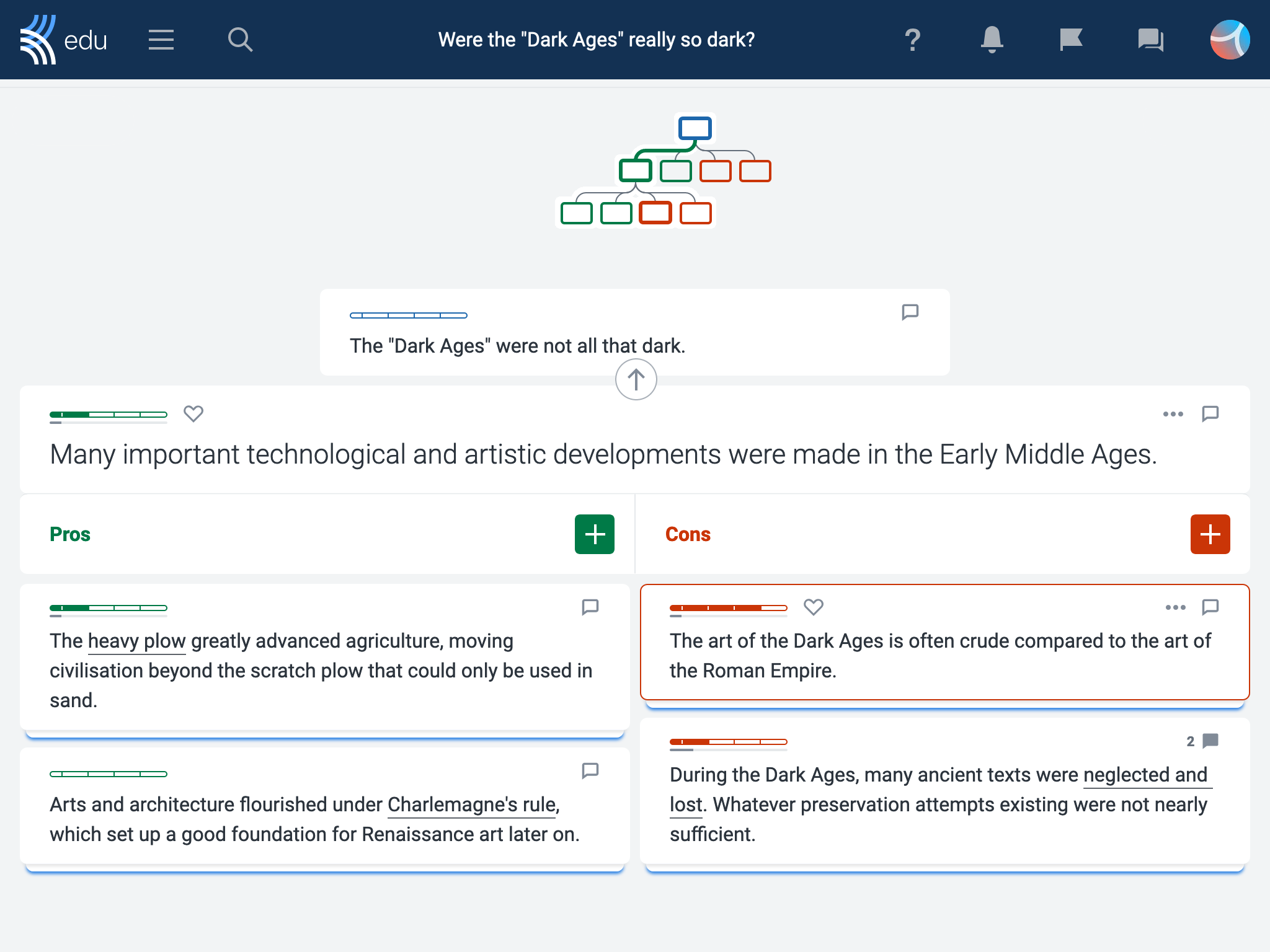

How can students use Kialo Edu in the constructivist classroom?

Kialo Edu’s argument-mapping platform is an ideal tool for building students’ critical thinking skills in the constructivist classroom. Each Kialo discussion provides a meaningful context for students to build or apply their knowledge independently.

Educators can scaffold students’ initial contributions by providing background information and top-level claims; then, the onus is on students to build their knowledge and construct the discussion.

So, let’s explore further how Kialo discussions align with the constructivist principles mentioned above.

Constructing knowledge: Students use the Kialo discussions as a framework for knowledge

- The argument map acts as a visual representation of students’ increasing knowledge as they add claims to it. Teachers can then guide students to help them identify any gaps in learning.

- Students can develop their source analysis and evaluation skills by researching and composing claims independently .

- Students can continually build their knowledge over multiple lessons, as there is a permanent record of the discussion. As students update the argument map with new information, they embody learning as a continuous process.

Taking responsibility for learning: Give students ownership of discussions

- Assigning students different roles in discussions increases their ownership of learning. As writers, students add and edit their own claims. In the role of editor, they can take more responsibility for discussions by reviewing all the claims. And for students to take full ownership of learning, they can create their own discussions!

- The platform breaks down arguments into understandable chunks. This helps students connect ideas and identify gaps in reasoning when pursuing independent lines of enquiry.

- Students are prompted to research and evaluate additional sources of information as they identify different facets of arguments.

- Kialo discussions have a range of tools that allow educators to step back while closely monitoring and guiding discussions as necessary.

Collaboration: Students work together to build knowledge

- Students can collaborate on the same discussion , or educators can assign teams different aspects of a topic to research in a jigsaw format.

- Collaboration within a discussion encourages students to strengthen claims with evidence and to recognize and challenge bias in other students’ ideas.

- Working with others encourages students to evaluate multiple perspectives on a topic.

- If the goal of a discussion is to explore the topic, rather than win the debate, Kialo discussions encourage students to extend each other’s knowledge.

Metacognition: Students use the argument map to review and reflect on learning

- When writing claims, students must reflect on their own thinking to decide on the most effective way to communicate their ideas.

- Students can use Kialo discussions to review their learning , which helps assimilate and accommodate new knowledge into existing schema.

- Seeing a visual representation of their discussion contributions facilitates students to evaluate their knowledge of the topic.

Meaningful learning experiences: Students engage in discussions on real-life issues

- Educators can select from a host of discussion topics that are both relevant to the curriculum and meaningful to students .

- The versatility of Kialo Edu discussions makes them ideal for motivating students when discussing meaningful topics. For example, try increasing engagement by having students complete a discussion in the roles of the key players in World War I .

- Students are sure to have a lot to say on real-life issues. Having to wait their turn in a traditional discussion may zap students’ motivation, but on Kialo Edu, all students can contribute instantly and simultaneously to a discussion, maximizing their engagement.

- When discussing sensitive and controversial topics , educators can make discussions anonymous to encourage students to make honest contributions.

It is clear that the constructivist approach of Piaget, Vygotsky, and Dewey still has a place in your classroom today. You can engage your students in constructing knowledge — and develop their critical thinking skills — through meaningful, collaborative activities like Kialo discussions!

We would love to hear how you are using constructivism to build your students’ critical thinking skills. Contact us at [email protected] or on any of our social media platforms.

Want to try Kialo Edu with your class?

Sign up for free and use Kialo Edu to have thoughtful classroom discussions and train students’ argumentation and critical thinking skills.

Constructivist Learning Theory and Creating Effective Learning Environments

- First Online: 30 October 2021

Cite this chapter

- Joseph Zajda 36

Part of the book series: Globalisation, Comparative Education and Policy Research ((GCEP,volume 25))

3526 Accesses

8 Citations

This chapter analyses constructivism and the use of constructivist learning theory in schools, in order to create effective learning environments for all students. It discusses various conceptual approaches to constructivist pedagogy. The key idea of constructivism is that meaningful knowledge and critical thinking are actively constructed, in a cognitive, cultural, emotional, and social sense, and that individual learning is an active process, involving engagement and participation in the classroom. This idea is most relevant to the process of creating effective learning environments in schools globally. It is argued that the effectiveness of constructivist learning and teaching is dependent on students’ characteristics, cognitive, social and emotional development, individual differences, cultural diversity, motivational atmosphere and teachers’ classroom strategies, school’s location, and the quality of teachers. The chapter offers some insights as to why and how constructivist learning theory and constructivist pedagogy could be useful in supporting other popular and effective approaches to improve learning, performance, standards and teaching. Suggestions are made on how to apply constructivist learning theory and how to develop constructivist pedagogy, with a range of effective strategies for enhancing meaningful learning and critical thinking in the classroom, and improving academic standards.

The unexamined life is not worth living (Socrates, 399 BCE).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdullah Alwaqassi, S. (2017). The use of multisensory in schools . Indiana University. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/21663/Master%20Thesis%20in%

Acton, G., & Schroeder, D. (2001). Sensory discrimination as related to general intelligence. Intelligence, 29 , 263–271.

Google Scholar

Adak, S. (2017). Effectiveness of constructivist approach on academic achievement in science at secondary level. Educational Research Review, 12 (22), 1074–1079.

Adler, E. (1997). Seizing the middle ground: Constructivism in world politics. European Journal of International Relations, 3 , 319–363.

Akpan, J., & Beard, B. (2016). Using constructivist teaching strategies to enhance academic outcomes of students with special needs. Journal of Educational Research , 4 (2), 392–398. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1089692.pdf

Al Sayyed Obaid, M. (2013). The impact of using multi-sensory approach for teaching students with learning disabilities. Journal of International Education Research , 9 (1), 75–82. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1010855

Alt, D. (2017).Constructivist learning and openness to diversity and challenge in higher education environments. Learning Environments Research, 20 , 99–119. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-016-9223-8

Arends, R. (1998). Learning to teach . Boston: McGraw Hill.

Ayaz, M. F., & Şekerci, H. (2015). The effects of the constructivist learning approach on student’s academic achievement: A meta-analysis study . Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1072.4600&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Barlett, F. (1932), Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge: CUP.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . New York: General Learning Press.

Beck, C., & Kosnik, C. (2006). Innovations in teacher education: A social constructivist approach . New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Black, A., & Ammon, P. (1992). A developmental-constructivist approach to teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 43 (5), 323–335.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brooks, J., & Brooks, M. (1993). In search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms . Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bruner, J. (1963). The process of education . New York: Vintage Books.

Bynum, W. F., & Porter, R. (Eds.). (2005). Oxford dictionary of scientific quotations . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carnoy, M. (1999). Globalization and education reforms: What planners need to know . Paris: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

Crogman, H., & Trebeau Crogman, M. (2016). Generated questions learning model (GQLM): Beyond learning styles . Retrieved from https://www.cogentoa.com/article/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1202460

Dangel, J. R. (2011). An analysis of research on constructivist teacher education . Retreived from https://ineducation.ca/ineducation/article/view/85/361

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . New York: Collier Books.

Doll, W. (1993). A post-modem perspective on curriculum . New York: Teachers College Press.

Doolittle, P. E., & Hicks, D. E. (2003). Constructivism as a theoretical foundation for the use of technology in social studies. Theory and Research in Social Education, 31 (1), 71–103.

Dunn, R., & Smith, J. B. (1990). Chapter four: Learning styles and library media programs. In J. B. Smith (Ed.), School library media annual (pp. 32–49). Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Dunn, R., et al. (2009). Impact of learning-style instructional strategies on students’ achievement and attitudes: Perceptions of educators in diverse institutions. The Clearing House, 82 (3), 135–140. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30181095

Fontana, D. (1995). Psychology for teachers . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fosnot, C. T. (Ed.). (1989). Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice . New York: Teacher's College Press.

Fosnot, C. T., & Perry, R. S. (2005). Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. In C. T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice . New York: Teacher’s College Press.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences . New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century . New York: Basic Books.

Gredler, M. E. (1997). Learning and instruction: Theory into practice (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gupta, N., & Tyagi, H. K. (2017). Constructivist based pedagogy for academic improvement at elementary level . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321018062_constructivist_based_pedagogy_for_academic_improvement_at_elementary_level

Guzzini, S. (2000). A reconstruction of constructivism in international relations. European Journal of International Relations, 6 , 147–182.

Hirtle, J. (1996). Social constructivism . English Journal, 85 (1), 91. Retrieved from. https://search.proquest.com/docview/237276544?accountid=8194

Howe, K., & Berv, J. (2000). Constructing constructivism, epistemological and pedagogical. In D. C. Phillips (Ed.), Constructivism in education (pp. 19–40). Illinois: The National Society for the Study of Education.

Hunter, W. (2015). Teaching for engagement: part 1: Constructivist principles, case-based teaching, and active learning . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301950392_Teaching_for_Engagement_Part_1_Co

Jonassen, D. H. (1994). Thinking technology. Educational Technology, 34 (4), 34–37.

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Revisiting activity theory as a framework for designing student-centered learning environments. In D. H. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (pp. 89–121). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kelly, G. A. (1955/1991). The psychology of personal constructs . Norton (Reprinted by Routledge, London, 1991).

Kharb, P. et al. (2013). The learning styles and the preferred teaching—Learning strategies of first year medical students . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3708205/

Kim, B. (2001). Social constructivism. In M. Orey (Ed.), Emerging perspectives on learning, teaching, and technology . http://www.coe.uga.edu/epltt/SocialConstructivism.htm

Kim, J. S. (2005). The effects of a constructivist teaching approach on student academic achievement, self-concept, and learning strategies. Asia Pacific Education Review, 6 (1), 7–19.

Kolb, D. A., & Fry, R. (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. In C. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of group process . London: John Wiley.

Kukla, A. (2000). Social constructivism and the philosophy of science . London: Routledge.

Mahn, H., & John-Steiner, V. (2012). Vygotsky and sociocultural approaches to teaching and learning . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118133880.hop207006

Martin, J., & Sugarman, J. (1999). The psychology of human possibility and constraint . Albany: SUNY.

Matthews, M. (2000). Constructivism in science and mathematics education. In C. Phillips (Ed.), Constructivism in education, ninety-ninth yearbook of the national society for the study of education, Part 1 (pp. 159–192). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Maypole, J., & Davies, T. (2001). Students’ perceptions of constructivist learning in a Community College American History 11 Survey Course . Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/009155210102900205

McInerney, D. M., & McInerney, V. (2018). Educational psychology: Constructing learning (5th ed.). Sydney: Pearson.

McLeod, S. (2019). Constructivism as a theory for teaching and learning . Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/constructivism.html

OECD. (2007). Equity and quality in education . Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2009a). Key factors in developing effective learning environments: Classroom disciplinary climate and teachers’ self-efficacy. In Creating effective teaching and learning environments . Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2009b). Education at a glance . Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2009c). The schooling for tomorrow . Paris: OECD, Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

OECD. (2013). Synergies for better learning: An international perspective on evaluation & assessment . Retrieved from // www.oecd.org/edu/school/Evaluation_and_Assessment_Synthesis_Report.pdf

OECD. (2019a). PISA 2018 results (volume III): What school life means for students’ lives . Paris: OECD.

Oldfather, P., West, J., White, J., & Wilmarth, J. (1999). Learning through children’s eyes: Social constructivism and the desire to learn . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

O’Loughin, M. (1992). Rethinking science education: Beyond Piagetian constructivism toward a sociocultural model of teaching and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2 (8), 791–820.

Onuf, N. (2003). Parsing personal identity: Self, other, agent. In F. Debrix (Ed.), Language, agency and politics in a constructed world (pp. 26–49). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Onuf, N. G. (2013). World of our making . Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Packer, M., & Goicoechea, J. (2000). Sociocultural and constructivist theories of learning: Ontology, not just epistemology. Educational Psychologist, 35 (4), 227–241.

Phillips, D. (2000). An opinionated account of the constructivist landscape. In D. C. Phillips (Ed.), Constructivism in education, Ninety-ninth yearbook of the national society for the study of education, Part 1 (pp. 1–16). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1967). Biologie et connaissance (Biology and knowledge). Gallimard.

Piaget, J. (1972). The principles of genetic epistemology (W. Mays, Trans.). Basic Books.

Piaget, J. (1977). The development of thought: Equilibration of cognitive structures . (A. Rosin, Trans.). The Viking Press.

Postman, N., & Weingartner, C. S. (1971). Teaching as a subversive activity . Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Puacharearn, P. (2004). The effectiveness of constructivist teaching on improving learning environments in thai secondary school science classrooms . Doctor of Science Education thesis. Curtin University of Technology. Retrieved from https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/2329/14877_

Richardson, V. (2003). Constructivist pedagogy. Teachers College Record, 105 (9), 1623–1640.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2001). The relationship between learning style and cognitive style. Personality and Individual Differences, 30 (4), 609–616.

Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality . New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Shah, R. K. (2019). Effective constructivist teaching learning in the classroom . Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED598340.pdf

Sharma, H. L., & Sharma, L. (2012). Effect of constructivist approach on academic achievement of seventh grade learners in Mathematics. International Journal of Scientific Research, 2 (10), 1–2.

Shively, J. (2015). Constructivism in music education. Arts Education Policy Review: Constructivism, Policy, and Arts Education, 116 (3), 128–136.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: Critical teaching for social change . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Slavin, R. (1984). Effective classrooms, effective schools: A research base for reform in Latin American education . Retrieved from http://www.educoas.org/Portal/bdigital/contenido/interamer/BkIACD/Interamer/

Slavin, R. E. (2020). Education psychology: theory and practice (12th ed.). Pearson.

Steffe, L., & Gale, J. (Eds.). (1995). Constructivism in education . Hillsdale, NJ.: Erlbaum.

Stoffers, M. (2011). Using a multi-sensory teaching approach to impact learning and community in a second-grade classroom . Retrieved from https://rdw.rowan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=etd

Thomas, A., Menon, A., Boruff, J., et al. (2014). Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Implementation Science, 9 , 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-54 .

Article Google Scholar

Thompson, P. (2000). Radical constructivism: Reflections and directions. In L. P. Steffe & P. W. Thompson (Eds.), Radical constructivism in action: Building on the pioneering work of Ernst von Glasersfeld (pp. 412–448). London: Falmer Press.

von Glaserfeld, E. (1995). Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning . London: The Falmer Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934a). Myshlenie i rech (Thought and language). State Socio-Economic Publishing House (translated in 1986 by Alex Kozulin, MIT).

Vygotsky. (1934b). Thought and language . Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1968). The psychology of art . Moscow: Art.

Vygotsky, L. (1973). Thought and language (A. Kozulin, Trans. and Ed.). The MIT Press. (Originally published in Russian in 1934.)

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Watson, J. (2003). Social constructivism in the classroom . Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9604.00206

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Zajda, J. (Ed.). (2008a). Learning and teaching (2nd ed.). Melbourne: James Nicholas Publishers.

Zajda, J. (2008b). Aptitude. In G. McCulloch & D. Crook (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of education . London: Routledge.

Zajda, J. (2008c). Globalisation, education and social stratification. In J. Zajda, B. Biraimah, & W. Gaudelli (Eds.), Education and social inequality in the global culture (pp. 1–15). Dordrecht: Springer.

Zajda, J. (2018a). Motivation in the classroom: Creating effective learning environments. Educational Practice & Theory, 40 (2), 85–103.

Zajda, J. (2018b). Effective constructivist pedagogy for quality learning in schools. Educational Practice & Theory, 40 (1), 67–80.

Zajda, J. (Ed.). (2020a). Globalisation, ideology and education reforms: Emerging paradigms . Dordrecht: Springer.

Zajda, J. (Ed.). (2021). 3rd international handbook of globalisation, education and policy research . Dordrecht: Springer.

Zajda, J., & Majhanovich, S. (Eds.). (2021). Globalisation, cultural identity and nation-building: The changing paradigms . Dordrecht: Springer.

Zaphir, L. (2019). Can schools implement constructivism as an education philosophy? Retrieved from https://www.studyinternational.com/news/constructivism-education/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education & Arts, School of Education, Australian Catholic University, East Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Joseph Zajda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Zajda, J. (2021). Constructivist Learning Theory and Creating Effective Learning Environments. In: Globalisation and Education Reforms. Globalisation, Comparative Education and Policy Research, vol 25. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71575-5_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71575-5_3

Published : 30 October 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-71574-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-71575-5

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Critical Thinking Skills

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 155778

- Jim Marteney

- Los Angeles Valley College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

We are not born with natural critical thinking abilities. Critical thinking is a skill that can be developed. The good news is that we all have the ability to improve our critical thinking skills. We can become more effective decision makers and improve our self- confidence. Below are some of those Critical Thinking Skills that can be developed and enhanced:

Critical thinkers are intellectually curious . This skill implies that the critical thinker is never totally satisfied with what they know. He or she seeks answers to various kinds of questions and problems. The critical thinker is concerned with investigating the causes and seeking explanations of events; asking why, how, who, what, when, and where.

Critical thinkers are open-minded . An open-minded person is one who is confident enough in his/her abilities to accept new and contradictory ideas, which challenge his/her current beliefs. This is opposed to being “tolerant” where the dogmatic person may politely listen to other arguments, but their minds will not be changed.

The open-minded person is one who is not only willing to listen to new ideas, but will alter an already adopted position if the new data dictates. The open-minded person is willing to consider a wide variety of positions and beliefs as possibly being valid. Open-minded people are flexible. They are willing to change their beliefs and methods of inquiry, if they are faced with a more valid argument. Open-minded people show a willingness to admit they may be wrong and that other ideas they did not accept may be correct. Critical thinkers do not just want to prove they are correct; they are open- minded enough to change their mind.

Critical thinkers avoid “Red Herrings.” Critical thinkers follow a line of reasoning consistently to a particular conclusion. They avoid irrelevancies, called “red herrings,” that stray from the issue being argued. When Jim and his wife Suzy argue, and Jim feels he is losing, he looks at Suzy and says, “You argue pretty well for a short person.” He is hoping to draw her off the argument and send her fishing for the “red herring,” her being short. If she takes the bait the original argument fades away. Critical thinkers won’t go after “red herrings.”

Critical thinkers are aware of their own biases . All humans are biased, some more than others. Some know that they have biases, some are not aware of their biases. We all have biases that we are not aware of and the critical thinker strives to learn them, so he or she can be more in charge of their thinking. It may be too much of a challenge to eliminate the different biases we have. Instead a critical thinker needs to be aware of the bias and how it will affect the thinking process. Thinking about thinking is referred to as metacognition. A critical thinker looks at how he or she thinks and makes decisions in order to improve the process.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

----F. Scott Fitzgerald 1

Critical thinkers learn to handle confusion . People will do almost anything to avoid the mental pain that comes with lingering confusion. We bypass it, avoid it, and even try to pass it off to someone else. In this haste to avoid confusion we often make quick decisions based on limited data or overworked stereotypes. The critical thinker allows him or herself to be confused as they work through the argument towards a conclusion.

Critical thinkers are able to control and use their emotions . Notice this does not say, “ Eliminate emotions .” We gather all sorts of valuable data through our emotions, that we can use in the decision-making process. We just have to be careful not to let emotions dominate our critical thinking and argumentation. Nothing will destroy the critical thinking process faster than misplaced or misdirected anger, fear, or frustration.

Critical thinkers are sensitive and empathetic to the needs of others . Critical thinkers need to pay particular attention to the needs of their target audience. The needs, concerns, and desires of your audience may be different than yours. The critical thinker is more effective if he or she can understand those concerns. They may not agree with them, but at least they understand them. The target audience may be the person trying to convince you of their argument or the person you are trying to convince with your argument. Persuasion usually takes place when an advocate is able to meet the needs of his or her target audience. In fact, your needs may be unimportant as it pertains to moving a target audience towards adherence to your point of view.

Critical thinkers can distinguish between a conclusion that might be “true” and one that they would like to be “true.” Notice the use of "truth" with a lower case "t . " This "truth" refers to just what a person believes, not the ultimate correct position that would be indicated by "Truth." A conclusion that might be true, is based on calculating the probability of its outcome, to see if it has a reasonable chance of becoming a reality. The second type, a conclusion that you would like to be true, is based more on your wishing, wanting, and desiring that it become a reality. The first can be put to the tests of critical reasoning, but the second cannot, and, therefore, is of little value in critical thinking. You may believe your child to be a great person, but the evidence might suggest otherwise.

Critical thinkers know when to admit to not knowing something . An essential prerequisite to understanding is humility; to be able to admit when you don’t know an answer to a situation. Although we want to protect our egos by believing we know everything, learning comes from questioning, not from knowing all the answers. When we can admit that we don’t know, we are more likely to ask questions that will enable us to learn. By giving ourselves permission to admit we don’t know everything, we can overcome the fear that our lack of knowledge will be discovered. The energy expended trying to cover up what we don’t know diminishes our ability to learn. If we are always trying to disguise our lack of knowledge of a subject, we will never fully understand what it is we don’t know about it. Feel free to say, "I don't know."

Critical Thinkers are independent Thinkers. They have the confidence to state their opinions and point of view to others who might disagree. They use the skills of critical thinking to support their positions and make their arguments.

Critical thinkers seek a “dialogical” approach to the process of argument. “Dialogical” thinkers seriously seek points of view other than their own. The ability to think “dialogically” would include the abilities to: analyze, synthesize, compare and contrast, explain, evaluate, justify, recognize valid and invalid conclusions, identify or anticipate or pose problems, look for alternatives, apply logical principles, and solve conventional or novel problems. These are many of the skills of critically thinkers.

Stephen Brookfield in his book, Challenging Adults to Explore Alternative Ways of Thinking, writes,

“Critical thinking is only possible when people probe their habitual ways of thinking, for their underlying assumptions, those taken-for-granted values, common-sense ideas, and stereotypical notions about human nature that underlie our actions.” 2

We are looking at the process of argumentation and the type of person who can be most effective in an argumentative situation. You as a critical thinker will be both involved in an argument and an observer of an argument. We can improve our abilities to do both.

- Thomas Oppong "F. Scott Fitzgerald on first Rate Intelligence," 2018, medium.com/personal-growth/f...e-7cf8ea002794 (accessed on November 6, 2019)

- Brookfield, Stephen. Developing Critical Thinkers : Challenging Adults to Explore Alternative Ways of Thinking and Acting. (Baltimore: Laureate Education, 2010)

COMMENTS

Social thinking skills and constructive thinking skills are vital cognitive tools that serve different yet complementary functions. Social thinking is about empathizing, communicating, and working with others, whereas constructive thinking is about analyzing, creating, and problem-solving.

Distinguishing Between Constructive and Social Thinking Skills. While constructive thinking is centred around problem-solving and decision-making, social thinking focuses on interpersonal relationships and social awareness. Constructive thinking is often more analytical and task-oriented, whereas social thinking is more empathetic and relational.

Social constructivism is a collaborative learning approach that emphasizes student involvement, discussion, and knowledge exchange. ... • It helps to develop critical thinking and p roblem ...

Social Constructivism: Vygotsky's Theory Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) was a Russian psychologist whose sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities.Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person has not only a set of abilities but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper ...

Social constructivism is a variety of cognitive constructivism that emphasizes the collaborative nature of much learning. Social constructivism was developed by post-revolutionary Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky. Vygotsky was a cognitivist, but rejected the assumption made by cognitivists such as Piaget and Perry that it was possible to ...

Constructivist teachers do not take the role of the "sage on the stage.". Instead, teachers act as a "guide on the side" providing students with opportunities to test the adequacy of their current understandings. Theory. Implication for classroom. The educator should consider the knowledge and experiences students bring to class.

Social constructivist pedagogy increases students' analytical thinking, and problem-solving skills, through the use of critical thinking and critical literacy. It improves students' memory processes, especially long-term-memory, and the use of coding for retrieval, such as mnemonics, and enhances significantly students' social skill, by ...

Critical thinking, on the other hand, is a cognitive process that entails reviewing and rearranging information in a person's mind map (Hu, Citation 2011). Problem-solving is a complex process that necessitates the use of critical thinking skills to provide a range of answers (Daud & Santoso, Citation 2018; Giannakopoulos & Buckley, Citation ...

In the constructivist classroom, educators encourage students to apply critical thinking skills to evaluate the reliability and credibility of information used to build knowledge. When students judge the information to be useful, they analyze how to assimilate or accommodate it into their existing schemas. Thus, educators should design plenty ...

Critical thinking and problem-solving skills (reflection) Communication skills and decision making' (Slavin, 2020). ... I have been using a combination of cognitive and social constructivism, critical thinking and literacy, grounded in critical discourse analysis, in my graduate classes, in the Master of Teaching unit for a number of years. ...

The problem with the traditional model of education is that the student is largely receptive. The constructivist model corrects this defect by promoting learning within a highly interaction oriented pedagogy. The problem is that sometimes it combines this with a constructivist view of knowledge, which does not provide an adequate epistemological framework for critical thinking. Even though ...

Social constructivism upholds that knowledge develops as a result of social interaction and is not an individual possession but a shared experience. Kelly (2012) suggests that ... communicating skills, mental skills such as critical thinking , reflective thinking and evaluating diverse opinion. The role of the teacher in this method is that of ...

According to the University of the People in California, having critical thinking skills is important because they are [ 1 ]: Universal. Crucial for the economy. Essential for improving language and presentation skills. Very helpful in promoting creativity. Important for self-reflection.

critical thinking and constructivism that offer real promise for improving the achievement of all students in the core subject areas. Critical Thinking The concept of critical thinking may be one of the most significant trends in education relative to the dynamic relationship between how teachers teach and how students learn (Mason, 2010).

Brookfield (Citation 2012) maintains that the discussion taking place in collaborative learning is one way of identifying the critical thinking skills that the students use.He has introduced various forms of focused discussion groups (critical conversation, scenario analysis, circle of voices, circular response, and chalk-talk), in which students experience critical thinking, primarily as a ...

In addition, constructivist pedagogy in the classroom facilitates a good deal of students' engagement (Hunter, 2015; Zajda, 2018a; Shah, 2019; Zaphir, 2019).Constructivist pedagogy, by its nature, focuses on critical thinking and critical literacy activities during group work, and promotes students' cognitive, social and emotional aspects of learning.

Critical thinking in a social constructivist approach to learning ... Critical-thinking skills were measured by the critical-thinking skills module of the Collegiate Assessment of Academic Proficiency. This module is a 32-item measure of students' abilities to clarify, analyze, evaluate, and extend arguments. ...

Accreditation Standards change related to critical thinking skills, was also studied. This study was designed to link critical thinking and social work education in the context of social constructivism as an andragogical praxis for the development of critical thinking skills. The

Social Thinking focuses on helping kids figure out how to think in social situations. Kids are taught to observe and think about their own and others' thoughts and feelings. They also learn the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The idea is that kids need to develop social "thinking" before they can use social "skills

Critical Thinkers are independent Thinkers. They have the confidence to state their opinions and point of view to others who might disagree. They use the skills of critical thinking to support their positions and make their arguments. Critical thinkers seek a "dialogical" approach to the process of argument. "Dialogical" thinkers ...

This study examined social studies teachers' attitudes towards critical thinking as a dimension of constructive learning. The purpose of this study was indeed to develop a better understanding ...

Marissa L. Shuffler, PhD, has over 9 years of experience conducting basic and applied research in the areas of team development, leadership, and organizational effectiveness.Dr. Shuffler is an Assistant Professor of Industrial/Organizational Psychology at Clemson University. Her areas of expertise include team and leader training and development, intercultural collaboration, multiteam systems ...

A crucial skill involved in Critical Pedagogy is critical thinking. Critical thinking has been defined as "thinking about your own thinking" (Paul, 1990, as cited in Kunh, 1999) and implies learners' ability to critically pose themselves as evaluators of information, opinions, and processes, their own learning process included.