A Summary and Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

A Room of One’s Own is Virginia Woolf’s best-known work of non-fiction. Although she would write numerous other essays, including a little-known sequel to A Room of One’s Own , it is this 1929 essay – originally delivered as several lectures at the University of Cambridge – which remains Woolf’s most famous statement about the relationship between gender and writing.

Is A Room of One’s Own a ‘feminist manifesto’ or a work of literary criticism? In a sense, it’s a bit of both, as we will see. Before we offer an analysis of Woolf’s argument, however, it might be worth breaking down what her argument actually is . You can read the essay in full here .

A Room of One’s Own : summary

Woolf’s essay is split into six chapters. She begins by making what she describes as a ‘minor point’, which explains the title of her essay: ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.’ She goes on to specify that an inheritance of five hundred pounds a year – which would give a woman financial independence – is more important than women getting the vote (women had only attained completely equal suffrage to men in 1928, the same year that Woolf delivered her lectures).

Woolf adopts a fictional persona named ‘Mary Beton’, and addresses her audience (and readers) using this identity. This name has its roots in an old Scottish ballad usually known as either ‘Mary Hamilton’ or ‘The Four Marys’ and concerns Mary Hamilton, a lady-in-waiting to a Queen of Scotland. Mary falls pregnant by the King, but kills the baby and is later sentenced to be executed for her crime. ‘Mary Beton’ is one of the other three Marys in the ballad.

Woolf considers the ways in which women have been shut out from social and political institutions throughout history, illustrating her argument by observing that she, as a woman, would not be able to gain access to a manuscript kept within an all-male college at ‘Oxbridge’ (a rhetorical hybrid of Oxford and Cambridge; Woolf originally delivered A Room of One’s Own to the students of one of the colleges for women which had recently been founded at Cambridge, but these female students were still forbidden to go to certain spaces within all-male colleges at the university).

Next, Woolf turns her attention to what men have said about women in writing, and gets the distinct impression that men – who have a vested interest in retaining the upper hand when it comes to literature and education – portray women in certain ways in order to keep them as, effectively, second-class citizens.

Woolf’s next move is to consider what women themselves have written. It is at this point in A Room of One’s Own that Woolf invents a (fictional) sister to Shakespeare, whom Woolf (perhaps recalling the name of Shakespeare’s own daughter) calls ‘Judith Shakespeare’. (Incidentally, Woolf’s invention of ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ inspired a song by The Smiths of that name and the name of a female pop duo .)

Woolf invites us to imagine that this imaginary sister of William Shakespeare was born with the same genius, the same potential to become a great writer as her brother. But she is shut off from the opportunities her brother enjoys: grammar-school education, the chance to become an actor in London, the opportunity to earn a living in the Elizabethan theatre.

Instead, ‘Judith Shakespeare’ would find the doors to these institutions closed in her face, purely because she was born a woman. Woolf’s point is made in response to people who claim that a woman writer as great as Shakespeare has never been born; this claim misses the important fact that great writers are made as well as born, and few women in Shakespeare’s time enjoyed the opportunities men like Shakespeare had.

Woolf’s ‘Judith’ is seduced by an actor-manager in the London playhouses, she falls pregnant, and takes her own life in poverty and misery.

Woolf then returns to a survey of what women’s writing does exist, considering such authors as Jane Austen and Emily Brontë (both of whom she admires), as well as Aphra Behn, the first professional female author in England, whom Woolf argues should be praised by all women for showing that the professional woman writer could become a reality.

Behn, writing in the seventeenth century, was an important breakthrough for all women ‘for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.’ Earlier women writers were too constrained by their insecurity – as women writing in a male-dominated literary world – and this leads to a ‘flaw’ in their work.

But nineteenth-century novelists like Austen and George Eliot were ‘trained’ in social observation, and this enabled them to write novels about the world she knew:

Jane Austen hid her manuscripts or covered them with a piece of blotting-paper. Then, again, all the literary training that a woman had in the early nineteenth century was training in the observation of character, in the analysis of emotion. Her sensibility had been educated for centuries by the influences of the common sitting-room. People’s feelings were impressed on her; personal relations were always before her eyes. Therefore, when the middle-class woman took to writing, she naturally wrote novels.

But even this led to limitations: Emily Brontë’s genius was better-suited to poetic plays than to novels, while George Eliot would have made full use of her talents as a biographer and historian rather than as a novelist. So even here, women had to bend their talents into a socially acceptable form, and at the time this meant writing novels.

Woolf contrasts these nineteenth-century women novelists with women novelists of today (i.e., the 1920s). She discusses a recent novel, Life’s Adventure by Mary Carmichael. (Both the novel and the writer are fictional, invented by Woolf for the purpose of her argument.) In this novel, she finds some quietly revolutionary details, including the depiction of friendship between women , where novels had previously viewed women only in relation to men (e.g., as wives, daughters, friends, or mothers).

Woolf concludes by arguing that in fact, the ideal writer should be neither narrowly ‘male’ or ‘female’ but instead should strive to be emotionally and psychologically androgynous in their approach to gender. In other words, writers should write with an understanding of both masculinity and femininity, rather than writing ‘merely’ as a woman or as a man. This will allow writers to encompass the full range of human emotion and experience.

A Room of One’s Own : analysis

Woolf’s essay, although a work of non-fiction, shows the same creative flair we find in her fiction: her adoption of the Mary Beton persona, her beginning her essay mid-flow with the word ‘But’, and her imaginative weaving of anecdote and narrative into her ‘argument’ all, in one sense, enact the two-sided or ‘androgynous’ approach to writing which, she concludes, all authors should strive for.

A Room of One’s Own is both rational, linear argument and meandering storytelling; both deadly serious and whimsically funny; both radically provocative and, in some respects, quietly conservative.

Throughout, Woolf pays particular attention to not just the social constraints on women’s lives but the material ones. This is why the line which provides her essay with its title – ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction’ – is central to her thesis.

‘Judith Shakespeare’, William Shakespeare’s imagined sister, would never have become a great writer because the financial arrangements for women were not focused on educating them so that they could become breadwinners for their families, but on preparing them for marriage and motherhood. Their lives were structured around marriage as the most important economic and material event in their lives, for it was by becoming a man’s wife that a woman would attain financial security.

Such a woman, at least until the late nineteenth century when the Married Women’s Property Act came into English law, would usually have neither ‘a room of her own’ (because the rooms in which she would spend her time, such as the kitchen, bedroom, and nursery, were designed for domestic activities) nor money (because the wife’s wealth and property would, technically, belong to her husband).

Because of this strong focus on the material limitations on women, which in turn prevent them from gaining the experience, the education, or the means required to become great writers, A Room of One’s Own is often described as a ‘feminist’ work. This label is largely accurate, although it should be noted that Woolf’s opinion about women’s writing diverges somewhat from that of many other feminist writers and critics.

In particular, Woolf’s suggestion that writers should strive to be ‘androgynous’ has attracted criticism from later feminist critics because it denies the idea that ‘women’s writing’ and ‘women’s experience’ are distinct and separate from men’s. If women truly are treated as inferior subjects in a patriarchal society, then surely their experience of that society is markedly different from men’s, and they need what Elaine Showalter called ‘a literature of their own’ as well as a room of their own?

Later feminist thinkers, such as the French theorist Hélène Cixous, have suggested there is a feminine writing ( écriture feminine ) which stands as an alternative to a more ‘masculine’ kind of writing: where male writing is about constructing a reality out of solid, materialist details, feminine writing (and much modernist writing, including Woolf’s fiction, is ‘feminine’ in this way) is about the ‘spiritual’ or psychological aspects of everyday living, the daydreams and gaps, the seemingly ‘unimportant’ moments we experience in our day-to-day lives. It is also more meandering, less teleological or concerned with an end-point (marriage, death, resolution), than traditional male writing.

Given how much of Woolf’s fiction is written in this way and might therefore be described as écriture feminine , one wonders how far her argument in A Room of One’s Own is borne out by her own fiction.

Perhaps the answer lies in the novel Woolf had published shortly before she began writing A Room of One’s Own : her 1928 novel Orlando , in which the heroine changes gender throughout the novel as she journeys through three centuries of history. Indeed, if one wished to analyse one work of fiction by Woolf alongside A Room of One’s Own , Orlando might be the ideal choice.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Gender Studies › Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

Analysis of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 11, 2020 • ( 1 )

In her highly influential critical A Room of Ones Own (1929), Virginial Woolf studied the cultural, economical and educational disabilities within the patriarchal system that prevent women from realising their creative potential. With her imaginary character Judith (Shakespeare’s fictional sister), she illustrated that a woman with Shakespeare’s faculties would have been denied the opportunities that Shakespeare enjoyed. Examining the careers and works of woman authors like Aphra Behn , Jane Austen , George Eliot and the Bronte sisters, Woolf argued that the patriarchal education system and reading practices condition (or “interpellate,” to use an Althusserian term) women to read from men’s point of view, and make them internalise the aesthetics and literary values created/ adopted by male authors and critics within the patriarchal system — wherein, these values, although male centered are assumed and promoted as universal.

It is in this polemical work, that Woolf suggested that language is gendered, thus inaugurating the language debate, and argued that the woman author, having no other language at her command, is forced to use the sexist/ masculine language. Dale Spender (in her Man Made Language ) as well as the French Feminists primarily investigated the gendered nature of language- Helene Cixous ( Ecriture Feminine ), Julia Kristeva ( chora , semiotic language ) and Luce lrigaray ( Écriture féminine ).

Woolf also realized the need for a narrative form to capture the fluid, incoherent female experiences that defy order and rationality; and hence her employment of the stream-of-consciousness technique in her novels, capturing the lives of Mrs Dalloway, Mrs Ramsay and so on. Inspired by the psychological theories of Carl Jung , Woolf also proposed the concept of the androgynous creative mind, which she fictionalised through Orlando , in an attempt to go beyond the male/female binary. She believed that the best artists were always a combination of the man and the woman or “woman-manly” or “man-womanly”.

Woolf was already connecting feminism to anti-fascism in A Room of One’s Own , which addresses in some detail the relations between politics and aesthetics. The book is based on lectures Woolf gave to women students at Cambridge, but its innovatory style makes it read in places like a novel, blurring boundaries between criticism and fiction. It is regarded as the first modern primer for feminist literary criticism, not least because it is also a source of many, often conflicting, theoretical positions. The title alone has had enormous impact as cultural shorthand for a modern feminist agenda. Woolf ’s room metaphor not only signifies the declaration of political and cultural space for women, private and public, but the intrusion of women into spaces previously considered the spheres of men. A Room of One’s Own is not so much about retreating into a private feminine space as about interruptions, trespassing and the breaching of boundaries (Kamuf, 1982: 17). It oscillates on many thresholds, performing numerous contradictory turns of argument (Allen, 1999). But it remains a readable and accessible work, partly because of its playful fictional style: the narrator adopts a number of fictional personae and sets out her argument as if it were a story. In this reader-friendly manner some complicated critical and theoretical issues are introduced. Many works of criticism, interpretation and theory have developed from Woolf’s original points in A Room of One’s Own , and many critics have pointed up the continuing relevance of the book, not least because of its open construction and resistance to intellectual closure (Stimpson, 1992: 164; Laura Marcus, 2000: 241). Its playful narrative strategies have divided feminist responses, most notably prompting Elaine Showalter’s disapproval (Showalter, 1977: 282). Toril Moi’s counter to Showalter’s critique forms the basis of her classic introduction to French feminist theory, Sexual/Textual Politics (1985), in which Woolf’s textual playfulness is shown to anticipate the deconstructive and post-Lacanian theories of Hélène Cixous, Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray.

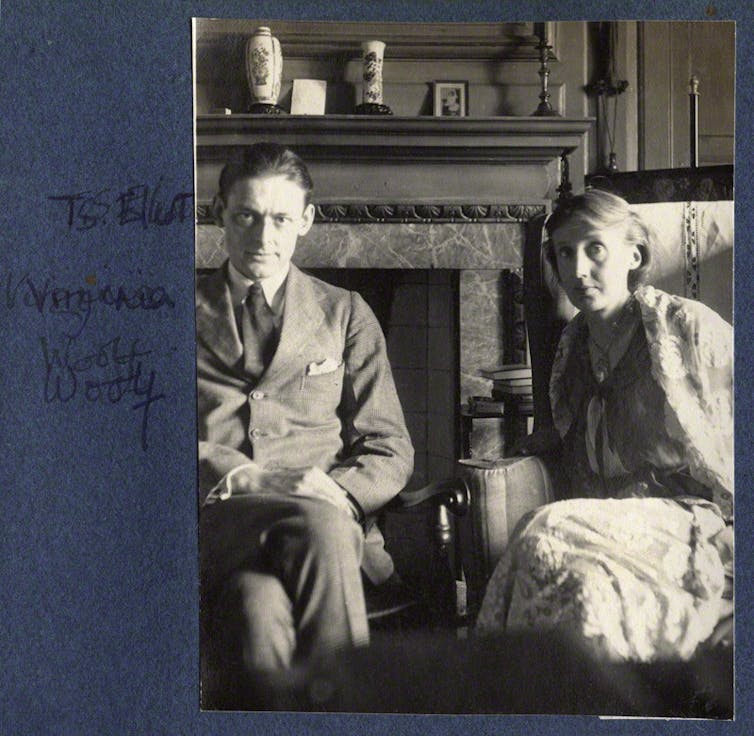

Virginia_Woolf/George Charles Beresford

Although much revised and expanded, the final version of A Room of One’s Own retains the original lectures’ sense of a woman speaking to women. A significant element of Woolf ’s experimental fictional narrative strategy is her use of shifting narrative personae to voice the argument. She anticipates recent theoretical concerns with the constitution of gender and subjectivity in language in her opening declaration that ‘ ‘‘I’’ is only a convenient term for somebody who has no real being . . . (callme Mary Beton, Mary Seton,Mary Carmichael or by any name you please – it is not a matter of any importance)’ (Woolf, 1929: 5). And A Room of One’s Own is written in the voice of at least one of these Mary figures, who are to be found in the Scottish ballad ‘The Four Marys’. Much of the argument is ventriloquised through the voice of Woolf’s own version of ‘Mary Beton’. In the course of the book this Mary encounters new versions of the other Marys – Mary Seton has become a student at ‘Fernham’ college, and Mary Carmichael an aspiring novelist – and it has been suggested that Woolf ’s opening and closing remarks may be in the voice of Mary Hamilton (the narrator of the ballad). The multi-vocal, citational A Room of One’s Own is full of quotations from other texts too. The allusion to the Scottish ballad feeds a subtext in Woolf’s argument concerning the suppression of the role of motherhood – Mary Hamilton sings the ballad from the gallows where she is to be hanged for infanticide. (Marie Carmichael, furthermore, is the nom de plume of contraceptive activist Marie Stopes who published a novel, Love’s Creation , in 1928.)

The main argument of A Room of One’s Own , which was entitled ‘Women and Fiction’ in earlier drafts, is that ‘a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction’ (1929: 4). This is a materialist argument that, paradoxically, seems to differ from Woolf’s apparent disdain for the ‘materialism’ of the Edwardian novelists recorded in her key essays on modernist aesthetics, ‘Modern Fiction’ (1919; 1925) and ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’ (1924). The narrator of A Room of One’s Own begins by telling of her experience of visiting an Oxbridge college where she was refused access to the library because of her gender. She compares in some detail the splendid opulence of her lunch at a men’s college with the austerity of her dinner at a more recently established women’s college (Fernham). This account is the foundation for the book’s main, materialist, argument: ‘intellectual freedom depends upon material things’ (1929: 141). The categorisation of middle-class women like herself with the working classes may seem problematic, but in A Room of One’s Own Woolf proposes that women be understood as a separate class altogether, equating their plight with the working classes because of their material poverty, even among the middle and upper classes (1929: 73–4).

Woolf’s image of the spider’s web, which she uses as her simile for the material basis of literary production, has become known in literary criticism as ‘Virginia’s web’. It is conceived in the passage where the narrator of A Room of One’s Own begins to consider the apparent dearth of literature by women in the Elizabethan period:

fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners. Often the attachment is scarcely perceptible; Shakespeare’s plays, for instance, seem to hang there complete by themselves. But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in mid-air by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in. (1929: 62–3)

According to this analysis, literary materialism may be understood in several different ways. To begin with, the materiality of writing itself is acknowledged: it is physically made, and not divinely given or unearthly and transcendent. Woolf seems to be attempting to demystify the solitary, romantic figure of the (male) poet or author as mystically singled out, or divinely elected. But the idea that a piece of writing is a material object is also connected to a strand of modernist aesthetics concerned with the text as self-reflexive object, and to a more general sense of the concreteness of words, spoken or printed. Woolf’s spider’s web also suggests, furthermore, that writing is a bodily process, physically produced. The observation that writing is ‘the work of suffering human beings’ suggests that literature is produced as compensation for, or in protest against, existential pain and material lack. Finally, in proposing writing as ‘attached to grossly material things’, Woolf is delineating a model of literature as grounded in the ‘real world’, that is in the realms of historical, political and social experience. Such a position has been interpreted as broadly Marxist, but although Woolf ’s historical materialism may ‘gladden the heart of a contemporary Marxist feminist literary critic’, as Miche`le Barrett has noted, elsewhere Woolf, in typically contradictory fashion, ‘retains the notion that in the correct conditions art may be totally divorced from economic, political or ideological constraints’ (Barrett, 1979: 17, 23). Yet perhaps Woolf’s feminist ideal is in fact for women’s writing to attain, not total divorce from material constraints, but only the near-imperceptibility of the attachment of Shakespeare’s plays to the material world, which ‘seem to hang there complete by themselves’ but are nevertheless ‘still attached to life at all four corners’.

As well as underlining the material basis for women’s achieving the status of writing subjects, A Room of One’s Own also addresses the status of women as readers, and raises interesting questions about gender and subjectivity in connection with the gender semantics of the first person. After looking at the difference between men’s and women’s experiences of University, the narrator of A Room of One’s Own visits the British Museum where she researches ‘Women and Poverty’ under an edifice of patriarchal texts, concluding that women ‘have served all these centuries as looking glasses . . . reflecting the figure of man at twice his natural size’ (Woolf, 1929: 45). Here Woolf touches upon the forced, subordinate complicity of women in the construction of the patriarchal subject. Later in the book, Woolf offers a more explicit model of this when she describes the difficulties for a woman reader encountering the first person pronoun in the novels of ‘Mr A’: ‘a shadow seemed to lie across the page. It was a straight dark bar, a shadow shaped something like the letter ‘I’ . . . Back one was always hailed to the letter ‘I’ . . . In the shadow of the letter ‘I’ all is shapeless as mist. Is that a tree? No it is a woman’ (1929: 130). For a man to write ‘I’ seems to involve the positioning of a woman in its shadow, as if women are not included as writers or users of the first person singular in language. This shadowing or eliding of the feminine in the representation and construction of subjectivity not only emphasizes the alienation experienced by women readers of male-authored texts, but also suggests the linguistic difficulties for women writers in trying to express feminine subjectivity when the language they have to work with seems to have already excluded them. When the word ‘I’ appears, the argument goes, it is always and already signifying a masculine self.

The narrator of A Room of One’s Own discovers that language, and specifically literary language, is not only capable of excluding women as its signified meaning, but also uses concepts of the feminine itself as signs. Considering both women in history and woman as sign, Woolf’s narrator points out that there is a significant discrepancy between women in the real world and ‘woman’ in the symbolic order (that is, as part of the order of signs in the aesthetic realm):

Imaginatively she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history. She dominates the lives of kings and conquerors in fiction; in fact she was the slave of any boy whose parents forced a ring upon her finger. Some of the most inspired words, some of the most profound thoughts in literature fall from her lips; in real life she could scarcely spell, and was the property of her husband. (1929: 56)

Woolf here emphasizes not only the relatively sparse representation of women’s experience in historical records, but also the more complicated business of how the feminine is already caught up in the conventions of representation itself. How is it possible for women to be represented at all when ‘woman’, in poetry and fiction, is already a sign for something else? In these terms, ‘woman’ is a signifier in patriarchal discourse, functioning as part of the symbolic order, and what is signified by such signs is certainly not the lived, historical and material experience of real women. Woolf understands that this ‘odd monster’ derived from history and poetry, this ‘worm winged like an eagle; the spirit of life and beauty in a kitchen chopping suet’, has ‘no existence in fact’ (1929: 56).

Woolf converts this dual image to a positive emblem for feminist writing, by thinking ‘poetically and prosaically at one and the same moment, thus keeping in touch with fact – that she is Mrs Martin, aged thirty-six, dressed in blue, wearing a black hat and brown shoes; but not losing sight of fiction either – that she is a vessel in which all sorts of spirits and forces are coursing and flashing perpetually’ (1929: 56–7). This dualistic model, combining prose and poetry, fact and imagination is also central to Woolf ’s modernist aesthetic, encapsulated in the term ‘granite and rainbow’, which renders in narrative both the exterior, objective and factual (‘granite’), and the interior, subjective experience and consciousness (‘rainbow’). The modernist technique of ‘Free Indirect Discourse’ practised and developed by Woolf allows for this play between the objective and subjective, between third person and first person narrative.

A Room of One’s Own can be confusing because it puts forward contradictory sets of arguments, not least Woolf’s much-cited passage on androgyny, which has been influential on later deconstructive theories of gender. Her narrator declares: ‘it is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex’ (1929: 136) and a model of writerly androgyny is put forward, derived from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s work:

one must be woman-manly or man-womanly. It is fatal for a woman to lay the least stress on any grievance; to plead even with justice any cause; in any way to speak consciously as a woman . . . Some collaboration has to take place in the mind between the woman and the man before the art of creation can be accomplished. Some marriage of opposites has to be accomplished. (1929: 136)

Shakespeare, the poet playwright, is Woolf ’s ideal androgynous writer. She lists others – all men – who have also achieved androgyny (Keats, Sterne, Cowper, Lamb, and Proust – the only contemporary). But if the ideal is for both women and men to achieve androgyny, elsewhere A Room of One’s Own puts the case for finding a language that is gendered – one appropriate for women to use when writing about women.

One of the most controversial of Woolf ’s speculations in A Room of One’s Own concerns the possibility of an inherent politics in aesthetic form, exemplified by the proposition that literary sentences are gendered. A Room of One’s Own culminates in the prophecy of a woman poet to equal or rival Shakespeare: ‘Shakespeare’s sister’. But in collectively preparing for her appearance, women writers need to develop aesthetic form in several respects. In predicting that the aspiring novelist Mary Carmichael ‘will be a poet . . . in another hundred years’ time’ (1929: 123), Mary Beton seems to be suggesting that prose must be explored and exploited in certain ways by women writers before they can be poets. She also finds fault with contemporary male writers, such as Mr A who is ‘protesting against the equality of the other sex by asserting his own superiority’ (1929: 132). She sees this as the direct result of women’s political agitation for equality: ‘The Suffrage campaign was no doubt to blame’ (1929: 129). She raises further concerns about politics and aesthetics when she comments on the aspirations of the Italian Fascists for a poet worthy of fascism: ‘The Fascist poem, one may fear, will be a horrid little abortion such as one sees in a glass jar in the museum of some county town’ (1929: 134). Yet if the extreme patriarchy of fascism cannot produce poetry because it denies a maternal line, Woolf argues that women cannot write poetry either until the historical canon of women’s writing has been uncovered and acknowledged. Nineteenth-century women writers experienced great difficulty because they lacked a female tradition: ‘For we think back through our mothers if we are women’ (1929: 99). They therefore lacked literary tools suitable for expressing women’s experience. The dominant sentence at the start of the nineteenth century was ‘a man’s sentence . . . It was a sentence that was unsuited for women’s use’ (1929: 99–100).

Woolf ’s assertion here, through Mary Beton, that women must write in gendered sentence structure, that is develop a feminine syntax, and that ‘the book has somehow to be adapted to the body’ (1929: 101) seems to contradict the declaration that ‘it is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex’. She identifies the novel as ‘young enough’ to be of use to the woman writer: ‘No doubt we shall find her knocking that into shape for herself . . . and providing some new vehicle, not necessarily in verse, for the poetry in her. For it is the poetry that is still denied outlet. And I went on to ponder how a woman nowadays would write a poetic tragedy in five acts’ (1929: 116). Now the goal of A Room of One’s Own has shifted from women’s writing of fictional prose to poetry, the genre Woolf finds women least advanced in, while ‘poetic tragedy’ is Shakespeare’s virtuoso form and therefore the form to which ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ should aspire.Woolf ’s speculations on feminine syntax anticipate the more recent exploration of é criture féminine by French feminists such as Cixous. Woolf ’s interest in the body and bodies, in writing the body, and in the gender and positionality thereof, anticipates feminist investigations of the somatic, and has been understood as materialist, deconstructive and phenomenological (Doyle, 2001). Woolf’s interest in matters of the body also fuels the sustained critique, in A Room of One’s Own , of ‘reason’, or masculinist rationalism, as traditionally disembodied and antithetical to the (traditionally feminine) material and physical.

A Room of One’s Own is concerned not only with what form of literary language women writers use, but also with what they write about. Inevitably women themselves constitute a vital subject matter for women writers. Women writers will need new tools to represent women properly. The assertion of woman as both the writing subject and the object of writing is reinforced in several places: ‘above all, you must illumine your own soul’ (Woolf, 1929: 117), Mary Beton advises. The ‘obscure lives’ (1929: 116) of women must be recorded by women. The example supplied is Mary Carmichael’s novel which is described as exploring women’s relationships with each other. A Room of One’s Own was published shortly after the obscenity trial of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928), and in the face of this Woolf flaunts a blatantly lesbian narrative: ‘if Chloe likes Olivia and Mary Carmichael knows how to express it she will light a torch in that vast chamber where nobody has yet been’ (1929: 109). Her refrain, ‘Chloe likes Olivia’, has become a critical slogan for lesbian writing. In A Room of One’s Own , Woolf makes ‘coded’ references to lesbian sexuality in her account of Chloe and Olivia’s shared ‘laboratory’ (Woolf, 1929: 109; Marcus, 1987: 152, 169), and she calls for women’s writing to explore lesbianism more openly and for the narrative tools to make this possible.

One of the most controversial and contradictory passages in A Room of One’s Own concerns Woolf’s positioning of black women. Commenting on the sexual and colonial appetites of men, the narrator concludes: ‘It is one of the great advantages of being a woman that one can pass even a very fine negress without wishing to make an Englishwoman of her’ (1929: 65). A number of feminist critics have questioned the relevance of Woolf’s feminist manifesto for the experience of black women (Walker, 1985: 2377), and have scrutinised this sentence in particular (Marcus, 2004: 24–58). In seeking to distance women from imperialist and colonial practices, Woolf disturbingly excludes black women here from the very category of women. This has become the crux of much contemporary feminist debate concerning the politics of identity. The category of women both unites and divides feminists: white middle-class feminists, it has been shown, cannot speak for the experience of all women; and reconciliation of universalism and difference remains a key issue. ‘Women – but are you not sick to death of the word?’ Woolf retorts in the closing pages of A Room of One’s Own , ‘I can assure you I am’ (Woolf, 1929: 145). The category of women is not chosen by women, it represents the space in patriarchy from which women must speak and which they struggle to redefine.

Another contradictory concept in A Room of One’s Own is ‘Shakespeare’s sister’, a figure who represents the possibility that there will one day be a woman writer to match the status of Shakespeare, who has come to personify literature itself. ‘Judith Shakespeare’ stands for the silenced woman writer or artist. But to seek to mimic the model of the individual masculine writing subject may also be considered part of a conservative feminist agenda. On the other hand, Woolf seems to defer the arrival of Shakespeare’s sister in a celebration of women’s collective literary achievement – ‘I am talking of the common life which is the real life and not of the little separate lives which we live as individuals’ (1929 148–9). Shakespeare’s sister is a messianic figure who ‘lives in you and in me’ (1929: 148) and who will draw ‘her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners’ (1929: 149), but has yet to appear. She may be the common writer to Woolf’s ‘common reader’ (a term she borrows from Samuel Johnson), but she has yet to ‘put on the body which she has so often laid down’ (1929: 149). A Room of One’s Own closes with this contradictory model of individual achievement and collective effort.

Barrett, Miche`le (1979), ‘Introduction’, in Virginia Woolf on Women and Writing, ed. Miche`le Barrett, London: Women’s Press. Goldman, Jane (1998), The Feminist Aesthetics of Virginia Woolf: Modernism, Post- Impressionism, and the Politics of the Visual, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gruber, Ruth (2005), Virginia Woolf: The Will to Create as a Woman, New York: Carroll & Graf. Harrison, Jane (1925), Reminiscences of a Student Life, London: Hogarth Press. Hartman, Geoffrey (1970), ‘Virginia’s Web’, in Beyond Formalism: Literary Essays 1958–1970, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Holtby, Winifred (1932), Virginia Woolf, London: Wishart. Kamuf, Peggy (1982), ‘Penelope at Work: Interruptions in A Room of One’s Own’, in Novel 16. Moi, Toril (1985), Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory, London: Methuen. Showalter, Elaine (1977), A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bronte¨ to Lessing, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Stimpson, Catherine (1992), ‘Woolf’s Room, Our Project: The Building of Feminist Criticism’, in Virginia Woolf: Longman Critical Readers, ed. Rachel Bowlby, London: Longman. Woolf, Virginia (1929), A Room of One’s Own, London: Hogarth.

Main Source: Plain, Gill, and Susan Sellers. A History of Feminist Literary Criticism . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Share this:

Categories: Gender Studies

Tags: A Room of One’s Own , A Room of One’s Own Feminism , Analysis of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Commentary Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Criticism of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Essays on Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Feminism , Feminsit Reading of A Room of One’s Own , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Summary of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Synopsis Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Themes of Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own , Virginia Woolf , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Analysis , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Criticism , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Explanation , Virginia Woolf's A Room of One’s Own Notes

Related Articles

- Why this book is a MUST-READ for contemporary female writers. - WORDNAMA

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Professor of English Literature, University of Southern Queensland

Disclosure statement

Jessica Gildersleeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Southern Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

I sit at my kitchen table to write this essay, as hundreds of thousands of women have done before me. It is not my own room, but such things are still a luxury for most women today. The table will do. I am fortunate I can make a living “by my wits,” as Virginia Woolf puts it in her famous feminist treatise, A Room of One’s Own (1929).

That living enabled me to buy not only the room, but the house in which I sit at this table. It also enables me to pay for safe, reliable childcare so I can have time to write.

It is as true today, therefore, as it was almost a century ago when Woolf wrote it, that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” — indeed, write anything at all.

Still, Woolf’s argument, as powerful and influential as it was then — and continues to be — is limited by certain assumptions when considered from a contemporary feminist perspective.

Woolf’s book-length essay began as a series of lectures delivered to female students at the University of Cambridge in 1928. Its central feminist premise — that women writer’s voices have been silenced through history and they need to fight for economic equality to be fully heard — has become so culturally pervasive as to enter the popular lexicon.

Julia Gillard’s A Podcast of One’s Own , takes its lead from the essay, as does Anonymous Was a Woman , a prominent arts funding body based in New York.

Even the Bechdel-Wallace test , measuring the success of a narrative according to whether it features at least two named women conversing about something other than a man, can be seen to descend from the “Chloe liked Olivia” section of Woolf’s book. In this section, the hypothetical characters of Chloe and Olivia share a laboratory, care for their children, and have conversations about their work, rather than about a man.

Woolf’s identification of women as a poorly paid underclass still holds relevance today, given the gender pay gap. As does her emphasis on the hierarchy of value placed on men’s writing compared to women’s (which has led to the establishment of awards such as the Stella Prize ).

Read more: Friday essay: science fiction's women problem

Invisible women

In her book, Woolf surveys the history of literature, identifying a range of important and forgotten women writers, including novelists Jane Austen, George Eliot and the Brontes, and playwright Aphra Behn .

In doing so, she establishes a new model of literary heritage that acknowledges not only those women who succeeded, but those who were made invisible: either prevented from working due to their sex, or simply cast aside by the value systems of patriarchal culture.

Read more: Friday essay: George Eliot 200 years on - a scandalous life, a brilliant mind and a huge literary legacy

To illustrate her point, she creates Judith, an imaginary sister of the playwright Shakespeare.

What if such a woman had shared her brother’s talents and was as adventurous, “as agog to see the world” as he was? Would she have had the freedom, support and confidence to write plays? Tragically, she argues, such a woman would likely have been silenced — ultimately choosing suicide over an unfulfilled life of domestic servitude and abuse.

In her short, passionate book, Woolf examines women’s letter writing, showing how it can illustrate women’s aptitude for writing, yet also the way in which women were cramped and suppressed by social expectations.

She also makes clear that the lack of an identifiable matrilineal literary heritage works to impede women’s ability to write.

Indeed, the establishment of those major women writers in the 18th and 19th centuries (George Eliot, the Brontes et al), when “the middle-class woman began to write” is, Woolf argues, a moment in history “of greater importance than the Crusades or the War of the Roses”.

Male critics such as T.S. Eliot and Harold Bloom have identified a (male) writer’s relation to his precursors as necessary for his own literary production. But how, Woolf asks, is a woman to write if she has no model to look back on or respond to? If we are women, she wrote, “we think back through our mothers”.

Read more: #ThanksforTyping: the women behind famous male writers

Her argument inspired later feminist revisionist work of literary critics like Elaine Showalter , Sandra K. Gilbert and Susan Gubar who sought to restore the reputation of forgotten women writers and turn critical attention to women’s writing as a field worthy of dedicated study.

All too often in history, Woolf asserts, “Woman” is simply the object of the literary text — either the adored, voiceless beauty to whom the sonnet is dedicated or reflecting back the glow of man himself.

Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.

A Room of One’s Own returns that authority to both the woman writer and the imagined female reader whom she addresses.

Stream of consciousness

A Room of One’s Own also demonstrates several aspects of Woolf’s modernism. The early sections demonstrate her virtuoso stream of consciousness technique. She ruminates on women’s position in, and relation to, fiction while wandering through the university campus, driving through country lanes, and dawdling over a leisurely, solo lunch.

Critically, she employs telling patriarchal interruptions to that flow of thought.

A beadle waves his arms in exasperation as she walks on a private patch of grass. A less-than-satisfactory dinner is served to the women’s college. A “deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman” turns her away from the library. These interruptions show the frequent disruption to the work of a woman without a room.

This is the lesson also imparted in Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse where artist Lily Briscoe must shed the overbearing influence of Mr and Mrs Ramsay, a couple who symbolise Victorian culture, if she is to “have her vision”. The flights and flow of modernist technique are not possible without the time and space to write and think for herself.

A Room of One’s Own has been crucial to the feminist movement and women’s literary studies. But it is not without problems. Woolf admits her good fortune in inheriting £500 a year from an aunt.

Indeed her purse now “breed(s) ten-shilling notes automatically”.

Part of the purpose of the essay is to encourage women to make their living through writing.

But Woolf seems to lack an awareness of her own privilege and how much harder it is for most women to fund their own artistic freedom. It is easy for her to advise against “doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning”.

In her book, Woolf also criticises the “awkward break” in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), in which Bronte’s own voice interrupts the narrator’s in a passionate protest against the treatment of women.

Here, Woolf shows little tolerance for emotion, which has historically often been dismissed as hysteria when it comes to women discussing politics.

A Room of One’s Own ends with an injunction to work for the coming of Shakespeare’s sister, that woman forgotten by history. “So to work, even in poverty and obscurity, is worthwhile”.

Such a woman author must have her vision, even if her work will be “stored in attics” rather than publicly exhibited.

The room and the money are the ideal, we come to see, but even without them the woman writer must write, must think, in anticipation of a future for her daughter-artists to come.

An adaptation of A Room of One’s Own is currently at Sydney’s Belvoir Theatre.

- Julia Gillard

- English literature

- Virginia Woolf

- Women's writing

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

A Room of One's Own

Virginia woolf, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Financial and Intellectual Freedom

The title of Woolf 's essay is a key part of her thesis: that a woman needs money and a room of her own if she is to be able to write. Woolf argues that a woman needs financial freedom so as to be able to control her own space and life—to be unhindered by interruptions and sacrifices—in order to gain intellectual freedom and therefore be able to write. Further, she argues that such financial…

Women and Society

In addition to establishing the necessity for women to have financial and intellectual independence if they are to be able to truly contribute to the literary canon, Woolf addresses the societal factors that deny women those opportunities. As such, A Room of One's Own is a feminist text. But it does not assign blame for the state of society to particular men or as a conscious effort by men as a whole to suppress women…

Creating a Legacy of Women Writers

A Room of One's Own was fashioned out of a series of lectures that Woolf delivered to groups of students at Cambridge women's' colleges. She addresses these women explicitly and draws on certain assumptions and common knowledge—that they are all learned for example and that they're women—so we immediately have to consider the particularity of the occasion when reading the text. As a successful woman, Woolf stands before these women scholars as their elder and…

Beneath Woolf 's argument about what it takes for a woman to create fiction is another more universal argument about the nature of truth, which inevitably casts a shadow over the points she makes. Woolf seems to realize two main points about the nature of truth that she passes on to her audience.

The first point has to do with is subjectivity. As a lecturer, she says she hopes that her listeners find some truth…

A Room of One's Own

By virginia woolf.

- A Room of One's Own Summary

Virginia Woolf , giving a lecture on women and fiction, tells her audience she is not sure if the topic should be what women are like; the fiction women write; the fiction written about women; or a combination of the three. Instead, she has come up with "one minor point--a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction." She says she will use a fictional narrator whom she calls Mary Beton as her alter ego to relate how her thoughts on the lecture mingled with her daily life.

A week ago, the narrator crosses a lawn at the fictional Oxbridge university, tries to enter the library, and passes by the chapel. She is intercepted at each station and reminded that women are not allowed to do such things without accompanying men. She goes to lunch, where the excellent food and relaxing atmosphere make for good conversation. Back at Fernham, the women's college where she is staying as a guest, she has a mediocre dinner. She later talks with a friend of hers, Mary Seton , about how men's colleges were funded by kings and independently wealthy men, and how funds were raised with difficulty for the women's college. She and Seton denounce their mothers, and their sex, for being so impoverished and leaving their daughters so little. Had they been independently wealthy, perhaps they could have founded fellowships and secured similar luxuries for women. However, the narrator realizes the obstacles they faced: entrepreneurship is at odds with child-rearing, and only for the last 48 years have women even been allowed to keep money they earned. The narrator thinks about the effects of wealth and poverty on the mind, about the prosperity of males and the poverty of females, and about the effects of tradition or lack of tradition on the writer.

Searching for answers, the narrator explores the British Museum in London. She finds there are countless books written about women by men, while there are hardly any books by women on men. She selects a dozen books to try and come up with an answer for why women are poor. Instead, she locates a multitude of other topics and a contradictory array of men's opinions on women. One male professor who writes about the inferiority of women angers her, and it occurs to her that she has become angry because the professor has written angrily. Had he written "dispassionately," she would have paid more attention to his argument, and not to him. After her anger dissipates, she wonders why men are so angry if England is a patriarchal society in which they have all the power and money. Perhaps holding power produces anger out of fear that others will take one's power. She posits that when men pronounce the inferiority of women, they are really claiming their own superiority. The narrator believes self-confidence, a requirement to get through life, is often attained by considering other people inferior in relation to oneself. Throughout history, women have served as models of inferiority who enlarge the superiority of men.

The narrator is grateful for the inheritance left her by her aunt. Prior to that she had gotten by on loathsome, slavish odd jobs available to women before 1918. Now, she reasons that since nothing can take away her money and security, she need not hate or enslave herself to any man. She now feels free to "think of things in themselves"she can judge art, for instance, with greater objectivity.

The narrator investigates women in Elizabethan England, puzzled why there were no women writers in that fertile literary period. She believes there is a deep connection between living conditions and creative works. She reads a history book, learns that women had few rights in the era, and finds no material about middle-class women. She imagines what would have happened had Shakespeare had an equally gifted sister named Judith. She outlines the possible course of Shakespeare's life: grammar school, marriage, and work at a theater in London. His sister, however, was not able to attend school and her family discouraged her from independent study. She was married against her will as a teenager and ran away to London. The men at a theater denied her the chance to work and learn the craft. Impregnated by a theatrical man, she committed suicide.

The narrator believes that no women of the time would have had such genius, "For genius like Shakespeare's is not born among labouring, uneducated, servile people." Nevertheless, some kind of genius must have existed among women then, as it exists among the working class, although it never translated to paper. The narrator argues that the difficulties of writing--especially the indifference of the world to one's art--are compounded for women, who are actively disdained by the male establishment. She says the mind of the artist must be "incandescent" like Shakespeare's, without any obstacles. She argues that the reason we know so little about Shakespeare's mind is because his work filters out his personal "grudges and spites and antipathies." His absence of personal protest makes his work "free and unimpeded."

The narrator reviews the poetry of several Elizabethan aristocratic ladies, and finds that anger toward men and insecurity mar their writing and prevent genius from shining through. The writer Aphra Behn marks a turning point: a middle-class woman whose husband's death forced her to earn her own living, Behn's triumph over circumstances surpasses even her excellent writing. Behn is the first female writer to have "freedom of the mind." Countless 18th-century middle-class female writers and beyond owe a great debt to Behn's breakthrough. The narrator wonders why the four famous and divergent 19th-century female novelistsGeorge Eliot, Emily and Charlotte Brontë, and Jane Austen--all wrote novels; as middle-class women, they would have had less privacy and a greater inclination toward writing poetry or plays, which require less concentration. However, the 19th-century middle-class woman was trained in the art of social observation, and the novel was a natural fit for her talents.

The narrator argues that traditionally masculine values and topics in novelssuch as warare valued more than feminine ones, such as drawing-room character studies. Female writers, then, were often forced to adjust their writing to meet the inevitable criticism that their work was insubstantial. Even if they did so without anger, they deviated from their original visions and their books suffered. The early 19th-century female novelist also had no real tradition from which to work; they lacked even a prose style fit for a woman. The narrator argues that the novel was the chosen form for these women since it was a relatively new and pliable medium.

The narrator takes down a recent debut novel called Life's Adventure by Mary Carmichael . Viewing Carmichael as a descendant of the female writers she has commented on, the narrator dissects her book. She finds the prose style uneven, perhaps as a rebellion against the "flowery" reputation of women's writing. She reads on and finds the simple sentence "'Chloe liked Olivia.'" She believes the idea of friendship between two women is groundbreaking in literature, as women have historically been viewed in literature only in relation to men. By the 19th century, women grew more complex in novels, but the narrator still believes that each gender is limited in its knowledge of the opposite sex. The narrator recognizes that for whatever mental greatness women have, they have not yet made much of a mark in the world compared to men. Still, she believes that the great men in history often depended on women for providing them with "some stimulus, some renewal of creative power" that other men could not. She argues that the creativity of men and women is different, and that their writing should reflect their differences. The narrator believes Carmichael has much work to do in recording the lives of women, and Carmichael will have to write without anger against men. Moreover, since every one has a blind spot about themselves, only women can fill out the portrait of men in literature. However, the narrator feels Carmichael is "no more than a clever girl," even though she bears no traces of anger or fear. In a hundred years, the narrator believes, and with money and a room of her own, Carmichael will be a better writer.

The pleasing sight of a man and woman getting into a taxi provokes an idea for the narrator: the mind contains both a male and female part, and for "complete satisfaction and happiness," the two must live in harmony. This fusion, she believes, is what poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge described when he said a great mind is "androgynous": "the androgynous mindtransmits emotion without impedimentit is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided." Shakespeare is a fine model of this androgynous mind, though it is harder to find current examples in this "stridently sex-conscious" age. The narrator blames both sexes for bringing about this self-consciousness of gender.

Woolf takes over the speaking voice and responds to two anticipated criticisms against the narrator. First, she says she purposely did not express an opinion on the relative merits of the two genders--especially as writers--since she does not believe such a judgment is possible or desirable. Second, her audience may believe the narrator laid too much emphasis on material things, and that the mind should be able to overcome poverty and lack of privacy. She cites a professor's argument that of the top poets of the last century, almost all were well-educated and rich. Without material things, she repeats, one cannot have intellectual freedom, and without intellectual freedom, one cannot write great poetry. Women, who have been poor since the beginning of time, have understandably not yet written great poetry. She also responds to the question of why she insists women's writing is important. As an avid reader, the overly masculine writing in all genres has disappointed her lately. She encourages her audience to be themselves and "Think of things in themselves." She says that Judith Shakespeare still lives within all women, and that if women are given money and privacy in the next century, she will be reborn.

A Room of One’s Own Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for A Room of One’s Own is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Support of Feminism

In the novel, Judith, the fictional sister of William Shakespeare, lives a life of unrealized genius: though just as brilliant as her brother, Judith is unable to fulfill her potential in her patriarchal Elizabethan society and eventually commits...

In paragraph 5, what does the author reveal by comparing the way men and women are represented in history books?

Paragraph five of which chapter, please?

Beowulf “The Battle with Grendel’s Dam”

Brutal and vengeful.

Study Guide for A Room of One’s Own

A Room of One's Own study guide contains a biography of Virginia Woolf, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About A Room of One's Own

- Character List

- Chapters 1 Summary and Analysis

Essays for A Room of One’s Own

A Room of One's Own literature essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of A Room of One's Own.

- Femininity Versus Androgyny: The Ideological Debate Between Cixous and Woolf's A Room of One's Own

- Seeing With the Eye of God: Woolf, Fry and Strachey

- Making Room for Women: Virginia Woolf's Narrative Technique in A Room of One's Own

- Virginia Woolf and A Room of One's Own: Writing From the Female Perspective

- The Feminine Ideal in Female-Directed Works of Literature

Lesson Plan for A Room of One’s Own

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Introduction to A Room of One's Own

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- A Room of One's Own Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for A Room of One’s Own

- Introduction

- Adaptations and cultural references

- Search for:

You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Arts & Culture

Virginia Woolf and a Room of One’s Own | Essay

Author Joanna Kavenna, tell’s Litro why Virginia Woolf is still her heroine: “Woolf dared to take herself seriously as a writer, to insist on the importance of her enterprises. This was, to her, the symbolism of the room of one’s own: that a writer should not be deterred by a society that tells her she is absurd, or foolish, for writing at all”

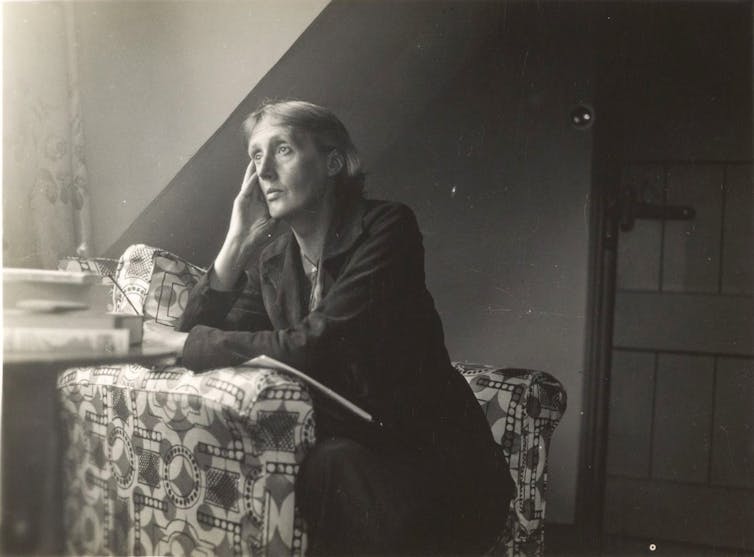

Some years ago now, I was a doctoral student, writing a fairly silly paper on the ‘commodification of Virginia Woolf.’ As part of the research, I borrowed a car and drove down to Monk’s House, through gaudy cornfields, everything fired by midsummer sun. Monk’s House belonged to Woolf and her husband Leonard, and it was from here that Woolf walked out on 28th March 1941, to drown herself in the nearby River Ouse.

Woolf was then (and is still) a heroine of mine: one of the very few British women writers who have established themselves firmly in the 20th-century canon. I read her for the first time at 14 or 15 – at first focusing on Mrs Dalloway and To The Lighthouse, then moving on to the diaries, letters, and other works including Orlando and Between the Acts. I read Woolf over and over again, obsessively, through my later teens and early twenties. Recently I edited and introduced a collection of her essays ( Essays on the Self NHE 2014 ) and was delighted, once more, by her lucid, elegant style.

In 1929, Woolf published her seminal essay, A Room of One’s Own. In this, she argues that a woman, in order to write and to retain her creative independence, needs a room of her own (with a lock) and 500 pounds a year. (The equivalent of about £30,000 a year in today’s terms.) Thereby, this woman frees herself from prying eyes, censorious discouragement by others, and intervention or dissuasion in line with the passing fashions of the market.

Woolf was fortunate enough to have achieved this independence through inherited wealth – a point she concedes freely. Such financial independence was untenable then for almost everyone, and remains so today. Still, Woolf’s argument was that writing had been, traditionally, a profession dominated by affluent men. Poor men were as excluded from the canon as poor women. However, Woolf argued, women were more likely to lack financial resources because at this time they were largely prevented from earning their own money.

On this long-gone summer’s day, I arrived to find a tourist bus blocking the entrance to the car park, and day-trippers streaming into Monk’s House. The gift shop was full of slogan-ed tea towels and coffee cups. The place seemed to have been duly ruined by commercialisation; I assumed it wouldn’t take long to prove the argument of my academic paper. What happened next was quite strange. I stepped over the threshold into what had been Woolf’s sitting room. Everything was preserved as if she had just walked out into the garden. The writing desk stood in a corner – one of those antique sloping desks with slender drawers to keep pens and paper in. The fireplace, the floral curtains, the sense of a particular sort of English house, from a particular era – all reminded me of my grandmother’s house, a woman who, though several decades younger than Woolf, and far less affluent, had preserved the same sort of domestic style throughout her life.

Standing in Monk’s House, I burst into tears. It was the sort of uncontrollable weeping more usually associated with profound grief. I tried at first to conceal my state – the house was full of visitors, and like many people I hate to cry in public. I went outside, breathed deeply, tried to resume. But I found that I couldn’t stop. In the end, I gave up any attempts at self-moderation, and wandered around the house sobbing loudly. Through the kitchen, into Woolf’s small dry cell-like bedroom with a single bed in it, into the immaculate garden, I cried and cried.

None of the other day trippers asked me why I was crying, they just moved aside to let me pass, looking at me in mild consternation. Perhaps they thought I was suffering from a disproportionate case of idol worship, fan hysteria.

I drove back to my teeming, pleasurable student life, and forgot the whole thing soon enough. A year later, when I was writing up my doctoral thesis, I inserted a brief footnote describing the experience at Monk’s House but failing to explain it – as I did not know what had caused it or what, if anything, it meant. The examiners perhaps thought that this a little too personal for a piece of academic work, but, if so, they were tactful and made no mention of it. They awarded me the doctorate, and sent me on my way.

I went out into the world, to earn my living, and – inspired by Woolf – to write novels of my own. I went first to London, to a jaundiced flat in the north of the city. I moved to a commune in the east of the city. I worked as a secretary and then as an editor for the Guardian newspaper. I moved to South London, to a burn-by-night house, perfectly placed for a few demolished pubs. I moved to New York, to Alphabet City, and worked for the New York Review of Books. The roof of my apartment fell down, so I moved to a charming dive opposite the Brooklyn Museum, where the sound of acrimony gurgled through the walls.

I took a job at the philosophy department of Oslo University, and moved to a minimalist room in that beautiful city. I took another academic post, in Munich. I went to Paris, to Tallinn, to Berlin where I lived in the former East, in an apartment above a train line. The room shuddered as I typed out a novel in the evenings. In Sydney, I lived by the Pacific Coast – the sun-bleached rocks like bones. I moved to South Africa, to China, to Italy. Most recently, I lived in a crumbling colonial building in Hikkaduwa, Sri Lanka, and watched my children playing in the garden, as I typed.

I wonder now if my uncharacteristic weeping at Monk’s House was, essentially, about rooms. I had recently lost my last grandparent at that time, my beloved grandmother, and had nearly lost my wonderful father, who has since passed away. I mourn the dead, and miss them always. As we go through life, we inhabit a series of rooms, and so do those we love. There are the rooms we are born in, the rooms we know as children, the friendly institutional rooms of school, where we play our part, one among an infinite series, the rising generation. Beyond, the rooms of adult life – rooms that have ‘played their part in the slowing down of the heart,’ as the British poet Charlotte Mew wrote – a rough contemporary of Woolf’s. We move through linear time, and yet these rooms remain – where we slept and ate and drank and loved, talked through one evening and another. We can return to these rooms, physically, or in our thoughts, but we can never regain the past.

We all seek a room of our own, and yet, we fail: our habitation is never permanent. Yet, writers live in the world of the imagination, and this makes one room an everywhere, as the English poet John Donne wrote. Woolf dared to take herself seriously as a writer, to insist on the importance of her enterprises. This was, to her, the symbolism of the room of one’s own: that a writer should not be deterred by a society that tells her she is absurd, or foolish, for writing at all. She argued that writers should dream freely, without suppressing their imaginations in line with external edicts. Thus, Woolf has inspired further generations of writers, and continues to inspire me in my own work. Some writers may be ‘commodified,’ it is true, and may become famous for reasons that have little to do with their work. But others, are present in the cultural imagination because their words are powerful, and resonate across the years. Woolf, for me, is a perfect example of the second category; the only category that matters at all.

About Joanna Kavenna

Joanna Kavenna is the author of several works of fiction and non-fiction, including THE ICE MUSEUM, INGLORIOUS, THE BIRTH OF LOVE, COME TO THE EDGE, A FIELD GUIDE TO REALITY and TOMORROW. Her essays and short stories have appeared in the New Yorker, the London Review of Books, Granta and the New York Times, among other publications. Kavenna has recently edited and introduced a collection of Woolf's essays, ESSAYS ON THE SELF, published by Notting Hill Editions.

- More Posts(2)

essays virginia woolf

You may also like

Rita and the girl, geoblocking and its impact on travellers in 2024, this thing for djs, jeff’s binge, leave a comment cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

New online writing courses

Privacy overview.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

A room of one's own

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Ristampa dell'edizione del 1931. - Fonte: Biblioteca "Giorgio Melchiori" del Dipartimento di Lingue e Letterature Straniere e Culture Moderne - Università di Torino (Progetto pubblico dominio a Torino), Digitalizzazione: Università degli Studi di Torino e Accademia di Medicina di Torino, 2018

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

35,646 Views

164 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Pubblico dominio a Torino on June 3, 2018

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Support 110 years of independent journalism.

Virginia Woolf’s politics of peace

Published between the wars, Woolf’s essay Three Guineas still has lessons for today’s conflict-ravaged world.

By Elif Shafak

The day I first encountered Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas (in an edition with A Room of One’s Own ), I was a young aspiring writer in Istanbul. It was a sweltering afternoon: the hustle and bustle of the ancient metropolis, the call to prayer spilling from the nearby mosques, the smells of fried mussels and sesame bagels wafting from the street vendors’ stalls, the seagulls picking through rubbish bins, the cats sauntering out of alleyways and the taste of salt in the wind.

And there I was, sporting a long hippie skirt, a green tote bag large enough to fit in several notebooks, and a terrible hairstyle, having made the mistake of visiting the hairdresser just the day before in the hope of magically obtaining naturally curly hair – something I had always wanted. What I got instead was a dreadful perm which had left parts of my head burned and my heart full of regrets. So in this confused state of existence, I walked out of a bookstore near Taksim Square, carrying Virginia Woolf ’s words close to my chest. I hurried to a café, eager to dive in to the book. Little did I know that by the time I had finished it something would have shifted in me. Thus began my lifelong infatuation with Woolf, who was not only a remarkable novelist and storyteller, but also a feminist thinker and a public intellectual.

In the UK, and also to a large extent in the US, we have a problem with the word “intellectual”. This is not the case in other countries; for instance, in France where there is a long – albeit male-dominated – tradition of public intellectuals. It is not the case in Turkey, either. In my motherland, as populist authoritarianism continues to hold sway over society, intellectuals are attacked, arrested, exiled or even imprisoned – but their existence, if not importance, is also generally acknowledged.

History shows us that in times of political crisis or economic decline, in times of inflamed populism and nativism, a dormant anti-intellectualism can flare up, taking the form of hostility towards experts, scholars, scientists, journalists or people in arts and literature. In the Anglosphere, intellectuals are seen, as the political scientist Richard Hofstadter wrote, as “pretentious, conceited, effeminate and snobbish; and very likely immoral, dangerous and subversive”. An intellectual is a dandified man who cannot be trusted – the antithesis of the image of strong and fearless manliness imposed on young boys as a model for male behaviour.

Let’s also consider the gender roles embedded in the word “intellectual”. There is a persistent patriarchal tendency that associates women with sentimentality and emotions while attributing rationality and analytical skills mainly to men. As a woman of letters, Virginia Woolf was acutely aware of this pattern. She questioned the cognitive segregation that patriarchy both created and thrived on. She railed against the way in which women were excluded from scholarly, cerebral, analytical work, and steered away from intellectually stimulating, interdisciplinary conversations.

The Saturday Read

Morning call.

- Administration / Office

- Arts and Culture

- Board Member

- Business / Corporate Services

- Client / Customer Services

- Communications

- Construction, Works, Engineering

- Education, Curriculum and Teaching

- Environment, Conservation and NRM

- Facility / Grounds Management and Maintenance

- Finance Management

- Health - Medical and Nursing Management

- HR, Training and Organisational Development

- Information and Communications Technology

- Information Services, Statistics, Records, Archives

- Infrastructure Management - Transport, Utilities

- Legal Officers and Practitioners

- Librarians and Library Management

- OH&S, Risk Management

- Operations Management

- Planning, Policy, Strategy

- Printing, Design, Publishing, Web

- Projects, Programs and Advisors

- Property, Assets and Fleet Management

- Public Relations and Media

- Purchasing and Procurement

- Quality Management

- Science and Technical Research and Development

- Security and Law Enforcement

- Service Delivery

- Sport and Recreation

- Travel, Accommodation, Tourism

- Wellbeing, Community / Social Services

Much has been said about how Woolf underlined the importance of women having a space and an income of their own if they ever were to become writers or poets – but it is not always noted that she did not stop there. Taking the argument further, Woolf explained in A Room of One’s Own that even when a woman is lucky enough to be in possession of a room and £500, even when she has the time and freedom to write, the themes she deals with in her books will, in all likelihood, be regarded as trivial. To this day, a woman novelist is expected to write about domestic, “feminine” subjects. To this day, women’s writing is regarded as less intellectual.

A decade after A Room of One’s Own (1929) was published, Woolf wrote Three Guineas . She was writing in the shadow of one world war, with another looming. Between 1914 and 1918, many civilians across the UK did not immediately grasp the extent of the suffering on the battlefield. It would take time for people to fully comprehend the gruesome reality of life in the trenches, the unseen scars and traumas inflicted by combat. A committed pacifist and antifascist, Woolf saw the invisible and could not unsee it. Her nephew had been killed in Spain, where he had volunteered to be an ambulance driver in the civil war. She had lost dear friends to conflict. She wanted everyone to understand the ravaging consequences of violence. More importantly, she wanted to dismantle the patriarchal structures that had perpetuated jingoism, militarism and war throughout history.

In Three Guineas Woolf imagines an established, educated man asking her opinion as to how to prevent war. How bizarre! Women are outsiders in this debate, never included in decision-making and policy design. Wars are waged by and between men; women are simply expected to go along with it. Woolf bitterly arraigned the rise of fascism and the rhetoric of warmongering, questioning the roles patriarchy assigned to wives and sisters and mothers: dedicated, giving, selfless. She believed a solution could only come from outsiders. The call to peace could not originate from the centre; only from the periphery. “As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world.” Woolf’s pacifism was strongly linked to a transnational perspective in line with Kantian cosmopolitanism and universalism. Today she might be criticised for being a “citizen of nowhere”.

Three Guineas , composed as a series of letters and published in 1938, received hostile reviews even from Woolf’s friends. The essay was perhaps too subtle for its time. It came as a shock to many that in response to activists who were urging people to fight fascism before it was too late, Woolf was prioritising the need to defy patriarchy. Was she too naive and shortsighted? Was she wise to focus on the structures that perpetuated wars?

Today our world is plagued, once again, with wars, violence against civilians, collective displacement, even mass starvation. Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan… Can women ever create a peaceful alternative? We may or may not agree with Woolf’s answer, but the question remains universal and urgent. Someday, women must build an alternative narrative, which can only come from the margins, a place of in-betweendom where we can meet each other. As Woolf said, “Unless we can think peace into existence we – not this one body in this one bed but millions of bodies yet to be born – will lie in the same darkness and hear the same death rattle overhead.”