- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 72, 2021, review article, stress and health: a review of psychobiological processes.

- Daryl B. O'Connor 1 , Julian F. Thayer 2 , and Kavita Vedhara 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 School of Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological Science, School of Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine, California 92697, USA; email: [email protected] 3 Division of Primary Care, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 72:663-688 (Volume publication date January 2021) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

- First published as a Review in Advance on September 04, 2020

- Copyright © 2021 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

The cumulative science linking stress to negative health outcomes is vast. Stress can affect health directly, through autonomic and neuroendocrine responses, but also indirectly, through changes in health behaviors. In this review, we present a brief overview of ( a ) why we should be interested in stress in the context of health; ( b ) the stress response and allostatic load; ( c ) some of the key biological mechanisms through which stress impacts health, such as by influencing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation and cortisol dynamics, the autonomic nervous system, and gene expression; and ( d ) evidence of the clinical relevance of stress, exemplified through the risk of infectious diseases. The studies reviewed in this article confirm that stress has an impact on multiple biological systems. Future work ought to consider further the importance of early-life adversity and continue to explore how different biological systems interact in the context of stress and health processes.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Adam EK , Doane LD , Zinbarg RE , Mineka S , Craske MG , Griffith JW 2010 . Prospective prediction of major depressive disorder from cortisol awakening responses in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35 : 921– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK , Quinn ME , Tavernier R , McQuillan MT , Dahlke KA , Gilbert KE 2017 . Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 83 : 25– 41 The first review and meta-analysis of the relationships between diurnal cortisol and health outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- al'Absi M , Wittmers LE Jr 2003 . Enhanced adrenocortical responses to stress in hypertension-prone men and women. Ann. Behav. Med. 25 : 25– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Am. Psychol. Assoc 2019 . Stress in America 2019 Washington, DC: Am. Psychol. Assoc. [Google Scholar]

- Ansorge S , Schön E. 1987 . Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DP IV), a functional marker of the T lymphocyte system. Acta Histochem 82 : 41– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH , Lutgendorf SK , Blomberg B , Carver CS , Lechner S et al. 2012 . Cognitive-behavioral stress management reverses anxiety-related leukocyte transcriptional dynamics. Biol. Psychiatry 71 : 366– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP , Thayer JF. 2015 . Heart rate variability as a transdiagnostic biomarker of psychopathology. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 98 : 338– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA , Hughes K , Leckenby N , Hardcastle KA , Perkins C , Lowey H 2015 . Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey. J. Public Health 37 : 445– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Benarroch EE. 2008 . The arterial baroreflex: functional organization and involvement in neurologic disease. Neurology 71 : 1733– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dov IZ , Kark JD , Ben-Ishay D , Mekler J , Ben-Arie L , Bursztyn M 2007 . Blunted heart rate dip during sleep and all-cause mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 167 : 2116– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K , Frost A , Bennett CB , Lindhiem O 2017 . Maltreatment and diurnal cortisol regulation: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 78 : 57– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Black DS , Cole SW , Irwin MR , Breen E , Cyr NMS et al. 2013 . Yogic meditation reverses NF-κB and IRF-related transcriptome dynamics in leukocytes of family dementia caregivers in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 : 348– 55 [Google Scholar]

- Boggero IA , Hostinar CE , Haak EA , Murphy MLM , Segerstrom S 2017 . Psychosocial functioning and the cortisol awakening response: meta-analysis, P-curve analysis and evaluation of the evidential value of existing studies. Biol. Psychol. 129 : 207– 30 [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE , Greendale G , Crosswell AD , Garet D , Sternlieb B et al. 2014 . Yoga reduces inflammatory signaling in fatigued breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 43 : 20– 29 [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF , Verkuil B , Thayer JF 2016 . The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: an evolution-theoretical perspective. J. Anxiety Disord. 41 : 22– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF , Verkuil B , Thayer JF 2017 . Exposed to events that never happen: generalized unsafety, the default stress response, and prolonged autonomic activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 74 : 287– 96 [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot JF , Verkuil B , Thayer JF 2018 . Generalized unsafety theory of stress: unsafe environments and conditions, and the default stress response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15 : 464 Comprehensive overview of an important new theory of stress. [Google Scholar]

- Bunea I , Szentágotai-Tătar A , Miu AC 2017 . Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: a meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 7 : 1274 [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL , Carvalho JP , Tyrka AR , Wier LM , Mello AF et al. 2007 . Decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol responses to stress in healthy adults reporting significant childhood maltreatment. Biol. Psychiatry 62 : 1080– 87 [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL , Shattuck TT , Tyrka AR , Geracioti TD , Price LH 2011 . Effect of childhood physical abuse on cortisol stress response. Psychopharmacology 214 : 367– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Carr CP , Martins CM , Stingel AM , Lemgruber VB , Juruena MF 2013 . The role of early life stress in adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic review according to childhood trauma subtypes. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 201 : 1007– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D , Ginty AT , Whittaker AC , Lovallo WR , de Rooij SR 2017 . The behavioural, cognitive, and neural corollaries of blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactions to acute psychological stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 77 : 74– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y , Steptoe A. 2009 . Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychol. 80 : 265– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Clancy F , Prestwich A , Caperon L , O'Connor DB 2016 . Perseverative cognition and health behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10 : 534 The first paper to extend the perseverative cognition hypothesis to health behaviors. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy F , Prestwich A , Caperon L , Tsipa A , O'Connor DB 2020 . The association between perseverative cognition and sleep in non-clinical populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. In press. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1700819 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Clow A , Hucklebridge F , Stalder T , Evans P , Thorn L 2010 . The cortisol awakening response: more than a measure of HPA axis function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35 : 97– 103 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. 2005 . Keynote presentation at the Eight International Congress of Behavioral Medicine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 12 : 123– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Doyle WJ , Skoner DP , Rabin BS , Gwaltney JM 1997 . Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA 277 : 1940– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Frank E , Doyle WJ , Skoner DP , Rabin BS , Gwaltney JM Jr 1998 . Types of stressors that increase susceptibility to the common cold in healthy adults. Health Psychol 17 : 214– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Gianaros PJ , Manuck SB 2016 . A stage model of stress and disease. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 456– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Janicki-Deverts D , Doyle WJ , Miller GE , Frank E et al. 2012 . Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. PNAS 109 : 5995– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Janicki-Deverts D , Turner RB , Doyle WJ 2015 . Does hugging provide stress-buffering social support? A study of susceptibility to upper respiratory infection and illness. Psychol. Sci. 26 : 135– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Miller GE , Rabin BS 2001 . Psychological stress and antibody response to immunization: a critical review of the human literature. Psychosom. Med. 63 : 7– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S , Tyrrell DA , Smith AP 1991 . Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N. Engl. J. Med. 325 : 606– 12 The first study to show that increases in psychological stress are associated with increased risk of developing a common cold. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. 2013 . Social regulation of human gene expression: mechanisms and implications for public health. Am. J. Public Health 103 : S84– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. 2019 . The conserved transcriptional response to adversity. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 28 : 31– 37 [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW , Capitanio JP , Chun K , Arevalo JMG , Ma J , Cacioppo JT 2015 . Myeloid differentiation architecture of leukocyte transcriptome dynamics in perceived social isolation. PNAS 112 : 15142– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW , Hawkley LC , Arevalo JMG , Cacioppo JT 2011 . Transcript origin analysis identifies antigen-presenting cells as primary targets of socially regulated gene expression in leukocytes. PNAS 108 : 3080– 85 [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW , Hawkley LC , Arevalo JMG , Sung CY , Rose RM , Cacioppo JT 2007 . Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol 8 : R189 The first study to show that gene expression is influenced by different levels of loneliness. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG , Wolitzky-Taylor KB , Mineka S , Zinbarg R , Waters AM et al. 2012 . Elevated responding to safe conditions as a specific risk factor for anxiety versus depressive disorders: evidence from a longitudinal investigation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 121 : 315– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD , Irwin MR , Burklund LJ , Lieberman MD , Arevalo JM et al. 2012 . Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain. Behav. Immun. 26 : 1095– 101 [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Pereira JS , Rea K , Nolan YM , O'Leary OF , Dinan TG , Cryan JF 2020 . Depression's unholy trinity: dysregulated stress, immunity, and the microbiome. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71 : 49– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Cuspidi C , Giudici V , Negri F , Sala C 2010 . Nocturnal nondipping and left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: an updated review. Exp. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 8 : 781– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Danese A , Baldwin JR. 2017 . Hidden wounds? Inflammatory links between childhood trauma and psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68 : 517– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Danese A , McEwen BS. 2012 . Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load and age-related disease. Phys. Behav. 106 : 29– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinot V , Gosse P , Kossovsky MP , Schott AM , Rouch I et al. 2010 . Autonomic nervous system activity is independently associated with the risk of shift in the non-dipper blood pressure pattern. Hypertens. Res. 33 : 1032– 37 [Google Scholar]

- De Rooij SR. 2013 . Blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity to acute psychological stress: a summary of results from the Dutch Famine Birth Cohort Study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 90 : 21– 27 [Google Scholar]

- De Vugt ME , Nicolson NA , Aalten P , Lousberg R , Jolle J , Verhey FR 2005 . Behavioral problems in dementia patients and salivary cortisol patterns in caregivers. J. Neuropsychiat. Clin. Neurosci. 17 : 201– 7 [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS , Kemeny ME. 2004 . Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol. Bull. 130 : 355– 91 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM , Burns VE , Allen LM , McPhee JS , Bosch JA et al. 2007 . Eccentric exercise as an adjuvant to influenza vaccination in humans. Brain Behav. Immun. 21 : 209– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM , Burns VE , Reynolds T , Carroll D , Drayson M , Ring C 2006 . Acute stress exposure prior to influenza vaccination enhances antibody response in women. Brain Behav. Immun. 20 : 159– 68 [Google Scholar]

- Fallo F , Barzon L , Rabbia F , Navarrini C , Conterno A et al. 2002 . Circadian blood pressure patterns and life stress. Psychother. Psychosom. 71 : 350– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Fan LB , Blumenthal JA , Hinderliter AL , Sherwood A 2013 . The effect of job strain on nighttime blood pressure dipping among men and women with high blood pressure. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 39 : 112 [Google Scholar]

- Fortmann AL , Gallo LC. 2013 . Social support and nocturnal blood pressure dipping: a systematic review. Am. J. Hypertens. 26 : 302– 10 [Google Scholar]

- Fries E , Dettenborn L , Kirschbaum C 2009 . The cortisol awakening response (CAR): facts and future directions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 72 : 67– 73 [Google Scholar]

- Gartland N , O'Connor DB , Lawton R , Bristow M 2014 . Exploring day-to-day dynamics of daily stressor appraisals, physical symptoms and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 50 : 130– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Gasperin D , Netuveli G , Dias-da-Costa JS , Pattussi MP 2009 . Effect of psychological stress on blood pressure increase: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cad. Saude Publica 25 : 715– 26 [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen L , Geerlings MI , Beekman AT , Deeg DJ , Penninx BW , Comijs HC 2010 . Early and late life events and salivary cortisol in older persons. Psychol. Med. 40 : 1569– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R , Kiecolt-Glaser JK , Bonneau RH , Malarkey W , Kennedy S , Hughes J 1992 . Stress-induced modulation of the immune response to recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Psychosom. Med. 54 : 22– 29 [Google Scholar]

- Hall M , Vasko R , Buysse D , Ombao H , Chen Q et al. 2004 . Acute stress affects heart rate variability during sleep. Psychosom. Med. 66 : 56– 62 [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M , Endrighi R , Venuraju SM , Lahiri A , Steptoe A 2012 . Cortisol responses to mental stress and the progression of coronary artery calcification in healthy men and women. PLOS ONE 7 : e31356 [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M , O'Donnell K , Lahiri A , Steptoe A 2010 . Salivary cortisol responses to mental stress are associated with coronary artery calcification in healthy men and women. Eur. Heart J. 31 : 424– 29 [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M , Steptoe A. 2012 . Cortisol responses to mental stress and incident hypertension in healthy men and women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 : E29– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Hill DC , Moss RH , Sykes-Muskett B , Conner M , O'Connor DB 2018 . Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 123 : 14– 22 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K , Bellis MA , Hardcastle KA , Sethi D , Butchart A et al. 2017 . The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2 : e356– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Jarczok MN , Jarczok M , Mauss D , Koenig J , Li J , Herr RM , Thayer JF 2013 . Autonomic nervous system activity and workplace stressors—a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 37 : 1810– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Jarczok MN , Jarczok M , Thayer JF 2020 . Work stress and autonomic nervous system activity. Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health ed. T Theorellpp. 625 – 56 Cham, Switz: Springer Int. Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Jarczok MN , Koenig J , Wittling A , Fischer JE , Thayer JF 2019 . First evaluation or an index of low vagally-mediated heart rate variability as a marker of health risks in human adults: proof of concept. J. Clin. Med. 8 : 1940 [Google Scholar]

- Julius S. 1995 . The defense reaction: a common denominator of coronary risk and blood pressure in neurogenic hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 17 : 375– 86 [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. 2016 . An overly permissive extension. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 442– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C , Pirke K-M , Hellhammer DH 1993 . The “Trier Social Stress Test”—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiol 28 : 76– 81 One of the most popular techniques to induce stress in the laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki M , Steptoe A. 2018 . Effects of stress on the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15 : 215 [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS , Manuck SB. 1984 . Acute psychophysiologic reactivity and risk of cardiovascular disease: a review and methodologic critique. Psychol. Bull. 96 : 435– 64 [Google Scholar]

- Landsbergis PA , Dobson M , Koutsouras G , Schnall P 2013 . Job strain and ambulatory blood pressure: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am. Public Health 103 : e61– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. 1999 . Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Lob E , Steptoe A. 2019 . Cardiovascular disease and hair cortisol: a novel biomarker of chronic stress. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 21 : 116 [Google Scholar]

- Loerbroks A , Schilling O , Haxsen V , Jarczok MN , Thayer JF , Fischer JE 2010 . The fruits of one's labor: Effort-reward imbalance but not job strain is related to heart rate variability across the day in 35–44-year-old workers. J. Psychosom. Res. 69 : 151– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR. 2013 . Early life adversity reduces stress reactivity and enhances impulsive behavior: implications for health behaviors. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 90 : 8– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR. 2016 . Stress and Health: Biological and Psychological Interactions Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. , 3rd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR , Cohoon AJ , Sorocco KH , Vincent AS , Acheson A et al. 2019 . Early‐life adversity and blunted stress reactivity as predictors of alcohol and drug use in persons with COMT (rs4680) Val158Met genotypes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 43 : 1519– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR , Dickensheets SL , Myers DA , Thomas TL , Nixon SJ 2000 . Blunted stress cortisol response in abstinent alcoholic and polysubstance-abusing men. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 24 : 651– 58 Early study showing that a blunted cortisol response may be a marker of HPA axis dysregulation. [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR , Farag NH , Sorocco KH , Acheson A , Cohoon AJ , Vincent AS 2013 . Early life adversity contributes to impaired cognition and impulsive behaviour: studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 37 : 616– 23 [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ , McEwen BS , Gunnar MR , Heim C 2009 . Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10 : 434– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB , Krantz DS. 1984 . Psychophysiologic reactivity in coronary heart disease. Behav. Med. Update 6 : 11– 15 [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M , Brunner E. 2005 . Cohort profile: the Whitehall II study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34 : 251– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL , Cohen S , Rabin BS , Manuck SB 2006 . Trait positive affect and antibody response to hepatitis B vaccination. Brain Behav. Immun. 20 : 261– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Massey AJ , Campbell BK , Raine-Fenning N , Pincott-Allen C , Perry J , Vedhara K 2016 . Relationship between hair and salivary cortisol and pregnancy in women undergoing IVF. Psychoneuroendocrinology 74 : 397– 405 [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K , Schwartz J , Cohen S , Seeman T 2006 . Diurnal cortisol decline is related to coronary calcification: CARDIA study. Psychosom. Med. 68 : 657– 61 [Google Scholar]

- Mayne SL , Moore KA , Powell-Wiley TM , Evenson KR , Block R , Kershaw KN 2018 . Longitudinal associations of neighborhood crime and perceived safety with blood pressure: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am. J. Hypertens. 31 : 1024– 32 [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. 1998 . Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 338 : 171– 79 Very influential overview of allostasis and allostatic load. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. 2000 . Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 22 : 108– 24 [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. 2018 . Redefining neuroendocrinology: epigenetics of brain-body communication over the life course. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49 : 8– 30 [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. 2019 . What is the confusion with cortisol. Chronic Stress 3 : 1– 3 [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS , McEwen CA. 2016 . Response to Jerome Kagan's Essay on Stress (2016). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 451– 55 [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS , Seeman T. 1999 . Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 896 : 30– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR , Raison CL , Pace TW , Arevalo JM , Cole SW 2017 . Natural language indicators of differential gene regulation in the human immune system. PNAS 114 : 12554– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE , Chen E. 2006 . Life stress and diminished expression of genes encoding glucocorticoid receptor and β2-adrenergic receptor in children with asthma. PNAS 103 : 5496– 501 [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE , Chen E , Sze J , Marin T , Arevalo JM et al. 2008 . A functional genomic fingerprint of chronic stress in humans: blunted glucocorticoid and increased NF-κB signaling. Biol. Psychiatry 64 : 266– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE , Chen E , Zhou ES 2007 . If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol. Bull. 133 : 25– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE , Cohen S , Ritchey AK 2002 . Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: a glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychol 21 : 531 [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE , Murphy ML , Cashman R , Ma R , Ma J et al. 2014 . Greater inflammatory activity and blunted glucocorticoid signaling in monocytes of chronically stressed caregivers. Brain Behav. Immun. 41 : 191– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen J , Dich N , Clark AJ , Ramlau-Hansen C , Head J et al. 2019 . Informal caregiving and diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol: results from the Whitehall II cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 100 : 41– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM , Youngblood LS , Jones JF , Unger ER , Miller AH et al. 2008 . Alterations in diurnal salivary cortisol rhythm in a population-based sample of cases with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom. Med. 70 : 298– 305 [Google Scholar]

- Newman E , O'Connor DB , Conner M 2007 . Daily hassles and eating behaviour: the role of cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32 : 125– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Obrist PA. 1981 . Cardiovascular Psychophysiology: A Perspective New York: Plenum Press [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Archer J , Hair WM , Wu FCW 2001 . Activational effects of testosterone on cognitive function in men. Neuropsychologia 39 : 1385– 94 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Branley-Bell D , Green J , Ferguson E , O'Carroll R , O'Connor RC 2020a . Effects of childhood trauma, daily stress and emotions on daily cortisol levels in individuals vulnerable to suicide. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 129 : 92– 107 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Ferguson E , Green J , O'Carroll RE , O'Connor RC 2016 . Cortisol and suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63 : 370– 79 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Gartland N , O'Connor RC 2020b . Stress, cortisol and suicide risk. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 152 : 101– 30 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Green J , Ferguson E , O'Carroll RE , O'Connor RC 2017 . Cortisol reactivity and suicidal behavior: investigating the role of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responses to stress in suicide attempters and ideations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 75 : 183– 91 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Green J , Ferguson E , O'Carroll RE , O'Connor RC 2018 . Effects of childhood trauma on cortisol levels in suicide attempters and ideations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 88 : 9– 16 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Hendrickx H , Dadd T , Talbot D , Mayes A et al. 2009 . Cortisol awakening rise in middle-aged women in relation to chronic psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 : 1486– 94 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Jones F , Conner M , McMillan B , Ferguson E 2008 . Effects of daily hassles and eating style on eating behavior. Health Psychol 27 : S20– 31 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DB , Walker S , Hendrickx H , Talbot D , Schaefer A 2013 . Stress-related thinking predicts the cortisol awakening response and somatic symptoms in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 : 438– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani C , Thayer JF , Verkuil B , Lonigro A , Medea B et al. 2015 . Physiological concomitants of perseverative cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 142 : 231– 59 [Google Scholar]

- Padden C , Concialdi-McGlynn C , Lydon S 2019 . Psychophysiological measures of stress in caregivers of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a system review. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 22 : 149– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Pakulak E , Stevens C , Neville H 2018 . Neuro-, cardio-, and immunoplasticity: effects of early adversity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 131– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AF , Zachariae R , Bovbjerg DH 2009 . Psychological stress and antibody response to influenza vaccination: a meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 23 : 427– 33 [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SA. 2010 . Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17 : 1055– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Powell DJ , Schlotz W. 2012 . Daily life stress and the cortisol awakening response: testing the anticipation hypothesis. PLOS ONE 7 : e52067 [Google Scholar]

- Power C , Thomas C , Li L , Hertzman C 2012 . Childhood psychosocial adversity and adult cortisol patterns. Br. J. Psychiatry 201 : 199– 206 [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC , Wolf OT , Hellhammer DH , Buske Kirschbaum A , von Auer K et al. 1997 . Free cortisol levels after awakening: a reliable biological marker for the assessment of adrenocortical activity. Life Sci 61 : 2539– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL , Miller AH. 2003 . When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 160 : 1554– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Raul J-S , Cirimele V , Ludes B , Kintz P 2004 . Detection of physiological concentrations of cortisol and cortisone in human hair. Clin. Biochem. 37 : 1105– 11 [Google Scholar]

- Roseboom T , de Rooij S , Painter R 2006 . The Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult health. Early Hum. Dev. 82 : 485– 91 [Google Scholar]

- Ruttle PL , Javaras KN , Klein MH , Armstrong JM , Burk LR , Essex MJ 2013 . Concurrent and longitudinal associations between diurnal cortisol and body mass index across adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health 52 : 731– 37 [Google Scholar]

- Salles GF , Ribeiro FM , Guimarães GM , Muxfeldt ES , Cardoso CR 2014 . A reduced heart rate variability is independently associated with a blunted nocturnal blood pressure fall in patients with resistant hypertension. J. Hypertens. 32 : 644– 51 [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM , Romero LM , Munck AU 2000 . How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr. Rev. 21 : 55– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Reinwald A , Pruessner JC , Hellhammer DH et al. 1999 . The cortisol response to awakening in relation to different challenge tests and a 12-hour cortisol rhythm. Life Sci 64 : 1653– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Schrepf A , O'Donnell M , Luo Y , Bradley CS , Kreder K et al. 2014 . Inflammation and inflammatory control in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: associations with painful symptoms. Pain 155 : 1755– 61 [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC , Boggero IA , Smith GT , Sephton SE 2014 . Variability and reliability of diurnal cortisol in younger and older adults: implications for design decisions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 49 : 299– 309 [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC , Miller G. 2004 . Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol. Bull. 130 : 601– 30 The most comprehensive review of the relationship between stress and the immune system. [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC , O'Connor DB. 2012 . Stress, health and illness: four challenges for the future. Psychol. Health 27 : 128– 40 [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. 1936 . A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. Nature 138 : 3479 32 [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. 1950 . Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. BMJ 1 : 1383– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Selye H. 1951 . The general-adaptation-syndrome. Annu. Rev. Med. 2 : 327– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM. 2019 . Stressnology: the primitive (and problematic) study of life stress exposure and pressing need for better measurement. Brain Behav. Immun. 75 : 3– 5 [Google Scholar]

- Snyder-Mackler N , Sanz J , Kohn JN , Brinkworth JF , Morrow S et al. 2016 . Social status alters immune regulation and response to infection in macaques. Science 354 : 6315 1041– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T , Kirschbaum C , Kudielka BM , Adam EK , Pruessner JC et al. 2016 . Assessment of the cortisol awakening response: expert consensus guidelines. Psychoneuroendocrinology 63 : 414– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T , Steudte-Schmiedgen S , Alexander N , Klucken T , Vater A et al. 2017 . Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 77 : 261– 74 [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A , Hamer M , Lin J , Blackburn EH , Erusalimsky JD 2017 . The longitudinal relationship between cortisol responses to mental stress and leukocyte telomere attrition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102 : 962– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A , Serwinski B. 2016 . Cortisol awakening response. Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior G Fink 277– 83 London: Academic [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P , Eyer J. 1988 . Allostasis: a new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health S Fisher, J Reason 629– 49 New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF , Lane RD. 2007 . The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biol. Psychol. 74 : 224– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF , Yamamoto SS , Brosschot JF 2010 . The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int. J. Cardiol. 141 : 122– 31 Key review linking autonomic nervous system imbalance to health outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- Thorn L , Hucklebridge F , Evans P , Clow A 2006 . Suspected nonadherence and weekend versus week day differences in the awakening cortisol response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31 : 1009– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher TN. 2006 . Arterial baroreceptor input contributes to long-term control of blood pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 8 : 249– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr L , Cooper DC , Mills PJ , Nelesen RA , Dimsdale JE 2010 . Everyday discrimination and nocturnal blood pressure dipping in black and white Americans. Psychosom. Med. 72 : 266 [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama AJ. 2019 . Stress and obesity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70 : 703– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Cobb JM , Rixon L , Jessop DS 2011 . Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and upper respiratory tract infection in young children transitioning to primary school. Psychopharmacology 214 : 309– 17 [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Saf. Executive 2019 . Work Related Stress, Anxiety and Depression Statistics in Great Britain 2019 London: Crown [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K , Ayling K , Sunger K , Caldwell D , Halliday V et al. 2019 . Psychological interventions as vaccine adjuvants: a systematic review. Vaccine 37 : 3255– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K , Cox NK , Wilcock GK , Perks P , Hunt M et al. 1999a . Chronic stress in elderly carers of dementia patients and antibody response to influenza vaccination. Lancet 353 : 627– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K , Fox J , Wang E 1999b . The measurement of stress-related immune dysfunction in psychoneuroimmunology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 23 : 699– 715 [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K , Tuinstra J , Miles JNV , Sanderman R , Ranchor AV 2006 . Psychosocial factors associated with indices of cortisol production in women with breast cancer and controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31 : 299– 311 [Google Scholar]

- Waehrer GM , Miller TR , Silverio Marques SC , Oh DL , Burke Harris N 2020 . Disease burden of adverse childhood experiences across 14 states. PLOS ONE 15 : e0226134 [Google Scholar]

- Wright KD , Hickman R , Laudenslager ML 2015 . Hair cortisol analysis: a promising biomarker of HPA activation in older adults. Gerontologist 55 : S140– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Wust S , Federenko I , Hellhammer DH , Kirschbaum C 2000 . Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress and the free cortisol response to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology 25 : 707– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

- DOI: 10.18843/IJMS/V5I3(9)/15

- Corpus ID: 149718781

A Systematic Literature Review of Work Stress

- Richard H. Burman , Tulsee Giri Goswami

- Published in International Journal of… 1 July 2018

Figures and Tables from this paper

54 Citations

Antecedents and consequences of work stress behavior, the source of teacher work stress: a factor analysis approach, a conceptual study on occupational stress and its impact on employees, occupational stress among teachers –a literature review, employee stress: a scoping review, nature and mindfulness to cope with work-related stress: a narrative review, a conceptual study on factors leading to stress and its impact on productivity with special reference to teachers in higher education, analysis of stressors factors on occupational stress and performance blue collar employees in pharmaceutical manufacturing, a review of the literature on occupational stress among teachers, work-related stress and performance of employees in nigerian banking industry: a survey of ikeja, 186 references, organizational options for preventing work-related stress in knowledge work, a review of occupational stress interventions in australia, work stress, coping strategies and resilience: a study among working females, work experience, work stress and hrm at the university, effects of work-related stress on work ability index among iranian workers, stress: the perceptions of social work lectures in britain, the impact of work stressors on the life satisfaction of social service workers: a preliminary study, taking the stress out of social work: a multidimensional model of occupational stress, stress in social services: mental wellbeing, constraints and job satisfaction, how do work stress and coping work toward a fundamental theoretical reappraisal, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Literature Reviews

What is a Literature Review?

- Steps for Creating a Literature Review

- Providing Evidence / Critical Analysis

- Challenges when writing a Literature Review

- Systematic Literature Reviews

A literature review is an academic text that surveys, synthesizes, and critically evaluates the existing literature on a specific topic. It is typically required for theses, dissertations, or long reports and serves several key purposes:

- Surveying the Literature : It involves a comprehensive search and examination of relevant academic books, journal articles, and other sources related to the chosen topic.

- Synthesizing Information : The literature review summarizes and organizes the information found in the literature, often identifying patterns, themes, and gaps in the current knowledge.

- Critical Analysis : It critically analyzes the collected information, highlighting limitations, gaps, and areas of controversy, and suggests directions for future research.

- Establishing Context : It places the current research within the broader context of the field, demonstrating how the new research builds on or diverges from previous studies.

Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews can take various forms, including:

- Narrative Reviews : These provide a qualitative summary of the literature and are often used to give a broad overview of a topic. They may be less structured and more subjective, focusing on synthesizing the literature to support a particular viewpoint.

- Systematic Reviews : These are more rigorous and structured, following a specific methodology to identify, evaluate, and synthesize all relevant studies on a particular question. They aim to minimize bias and provide a comprehensive summary of the existing evidence.

- Integrative Reviews : Similar to systematic reviews, but they aim to generate new knowledge by integrating findings from different studies to develop new theories or frameworks.

Importance of Literature Reviews

- Foundation for Research : They provide a solid background for new research projects, helping to justify the research question and methodology.

Identifying Gaps : Literature reviews highlight areas where knowledge is lacking, guiding future research efforts.

- Building Credibility : Demonstrating familiarity with existing research enhances the credibility of the researcher and their work.

In summary, a literature review is a critical component of academic research that helps to frame the current state of knowledge, identify gaps, and provide a basis for new research.

The research, the body of current literature, and the particular objectives should all influence the structure of a literature review. It is also critical to remember that creating a literature review is an ongoing process - as one reads and analyzes the literature, one's understanding may change, which could require rearranging the literature review.

Paré, G. and Kitsiou, S. (2017) 'Methods for Literature Reviews' , in: Lau, F. and Kuziemsky, C. (eds.) Handbook of eHealth evaluation: an evidence-based approach . Victoria (BC): University of Victoria.

Perplexity AI (2024) Perplexity AI response to Kathy Neville, 31 July.

Royal Literary Fund (2024) The structure of a literature review. Available at: https://www.rlf.org.uk/resources/the-structure-of-a-literature-review/ (Accessed: 23 July 2024).

Library Services for Undergraduate Research (2024) Literature review: a definition . Available at: https://libguides.wustl.edu/our?p=302677 (Accessed: 31 July 2024).

Further Reading:

Methods for Literature Reviews

Literature Review (The University of Edinburgh)

Literature Reviews (University of Sheffield)

- How to Write a Literature Review Paper? Wee, Bert Van ; Banister, David ISBN: 0144-1647

- Next: Steps for Creating a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 11:43 AM

- URL: https://library.lsbu.ac.uk/literaturereviews

- Open access

- Published: 06 September 2024

Breastfeeding experiences of women with perinatal mental health problems: a systematic review and thematic synthesis

- Hayley Billings 1 ,

- Janet Horsman 1 ,

- Hora Soltani 1 &

- Rachael Louise Spencer 2

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 24 , Article number: 582 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Despite its known benefits, breastfeeding rates among mothers with perinatal mental health conditions are staggeringly low. Systematic evidence on experiences of breastfeeding among women with perinatal mental health conditions is limited. This systematic review was designed to synthesise existing literature on breastfeeding experiences of women with a wide range of perinatal mental health conditions.

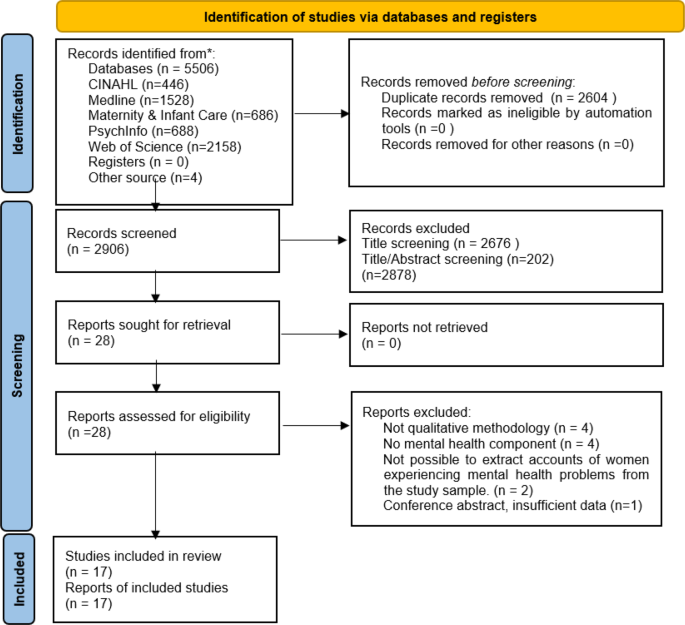

A systematic search of five databases was carried out considering published qualitative research between 2003 and November 2021. Two reviewers conducted study selection, data extraction and critical appraisal of included studies independently and data were synthesised thematically.

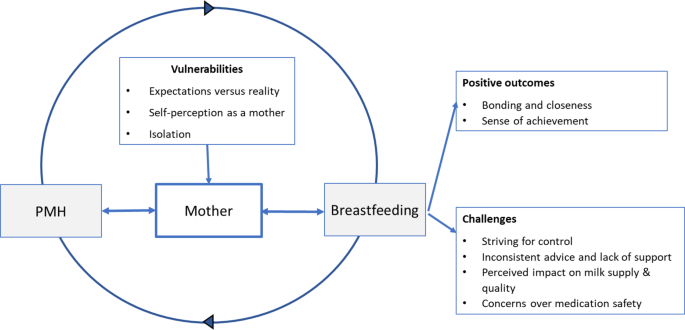

Seventeen articles were included in this review. These included a variety of perinatal mental health conditions (e.g., postnatal depression, post-traumatic stress disorders, previous severe mental illnesses, eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders). The emerging themes and subthemes included: (1) Vulnerabilities: Expectations versus reality; Self-perception as a mother; Isolation. (2) Positive outcomes: Bonding and closeness; Sense of achievement. (3) Challenges: Striving for control; Inconsistent advice and lack of support; Concerns over medication safety; and Perceived impact on milk quality and supply.

Conclusions

Positive breastfeeding experiences of mothers with perinatal mental health conditions can mediate positive outcomes such as enhanced mother/infant bonding, increased self-esteem, and a perceived potential for healing. Alternatively, a lack of consistent support and advice from healthcare professionals, particularly around health concerns and medication safety, can lead to feelings of confusion, negatively impact breastfeeding choices, and potentially aggravate perinatal mental health symptoms. Appropriate support, adequate breastfeeding education, and clear advice, particularly around medication safety, are required to improve breastfeeding experiences for women with varied perinatal mental health conditions.

Peer Review reports

Breastfeeding is a key public health measure, conferring short- and long-term health and socio-economic benefits for women and their offspring [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Breastfeeding has been identified as crucial in meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 [ 5 ] with the World Health Organisation aiming for global rates of 50% exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age by 2025 [ 6 ]. Despite an increasing research base about what helps or hinders breastfeeding, there is a dramatic drop in breastfeeding prevalence within the first six weeks of birth, especially in high income countries [ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. The reasons given for cessation of breastfeeding suggest that few mothers gave up because they planned to, citing challenges such as physical pain [ 10 ], perceived insufficient milk supply [ 11 ], and breastfeeding not fitting in with family and/ or work life [ 12 ], and although complex physiological and psychosocial factors influence breastfeeding practices, evidence also suggests that mothers who experience postnatal depression may be at a greater risk of early breastfeeding cessation [ 13 , 14 ].

Perinatal mental health (PMH) conditions are mental illnesses which occur during pregnancy and up to a year following birth [ 15 , 16 ] and include a range of conditions such as: depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), tokophobia, bipolar disorder, postpartum psychosis, eating disorders and personality disorders [ 17 ]. These conditions are associated with increased morbidity and are a leading cause of maternal death in high-income countries [ 17 ]. Globally it is estimated that between 15 and 25% of women experience mental illness during the perinatal period, either as a new condition or as a reoccurrence of a pre-existing condition [ 17 ].

Breastfeeding is known to have psychological benefits, such as improving mood and protecting against postnatal depression in mothers, enhancing socio-emotional development in the child and strengthening mother-child bonding [ 13 , 14 , 18 , 19 ]. However, previous reviews of women’s experiences of breastfeeding whilst experiencing mental health conditions have focused primarily on postnatal depression (PND) [ 19 ]. No previous reviews have been identified which investigate the experiences and perspectives of women with a variety of perinatal mental illnesses with a view to improving breastfeeding health intervention strategies for women with such conditions.

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement [ 20 ]. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO in 2021 (registration number CRD42021297076 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021297076 ). There was no requirement to deviate from this protocol during the study.

Search strategy

A literature search was undertaken for studies published from 2003 to Nov 2021. The selection of 2003 was to identify research undertaken following publication of the World Health Organisation Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding [ 21 ]. This advised that women exclusively breastfeed for six months and continue breastfeeding for two years and beyond for optimal health benefits to mother and infant.

The search was conducted using five electronic databases: Medline and CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost), Maternity & Infant Care (Ovid), APA PsycInfo ® (ProQuest) and Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate).

Search terms were devised according to the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) framework [ 22 ] (Table 1 ). Reference lists of included articles were scrutinised for possible additional studies.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included:

published from 2003.

peer-reviewed articles.

published in English.

any setting.

qualitative primary research data.

participants were women experiencing mental health issues.

described experiences, perceptions, views, and opinions in relation to breastfeeding.

Study selection

Titles, abstracts, and potentially relevant full texts were screened independently by two authors against the eligibility criteria. Disagreement was resolved through discussion and consultation with a third author.

Data extraction

Data extracted included study authors, title, year of publication, country of origin, source of funding, study aims, study design, recruitment strategies, participant ethnicity, PMH condition, and study results. Two authors independently extracted data.

Quality appraisal of included studies was carried out to demonstrate rigour, using a Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) appraisal tool [ 23 ], however this was not used as an indicator for inclusion in the analysis.

Data synthesis

Thematic synthesis, a method of analysis widely used for qualitative systematic reviews, was undertaken [ 24 ]. This involved line by line coding of extracted quotations followed by development of descriptive and analytical themes. NVivo software was used to systematically code extracted data. Verbatim quotations, along with information on themes and sub-themes they were assigned to in the original study, were imported into the software. Codes and their supporting data were reviewed to identify related categories which could be grouped into broader descriptive themes. From this, overarching analytic themes were identified.

Author reflexivity was considered and addressed throughout the review with regular discussions between authors to debate and establish aspects such as definitions of mental health, use of terminology, themes, subthemes and the interplay between them.

Patient and public involvement

Once key findings were established, the project team organised two patient and public involvement events, which included ethnic minority perinatal peer supporters and a pre/postnatal peer support group with PMH experiences. Feedback from these groups showed that the themes identified by the review captured the main priorities of the groups.

The study selection process is outlined on the PRISMA [ 20 ] flow diagram (Fig. 1 ). A total of 5510 studies were retrieved. After removing duplicates ( n = 2604) and excluding articles which were not relevant following screening of title and abstract ( n = 2878), full text of the remaining 28 studies were screened. Of these, 11 studies were excluded, resulting in 17 studies being included in this review.

PRISMA flow diagram detailing study selection [ 20 ]. CINAHL – Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. PRISMA flow diagram- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ . 2021;372(71). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Characteristics of the studies

From the 17 included studies, four used thematic analysis, two in a qualitative study [ 25 , 26 ] and two within a mixed methods secondary analysis of existing data [ 27 , 28 ]. Six studies used phenomenological methods [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ], two used an ethnographic approach [ 35 , 36 ] and three undertook a Grounded Theory approach [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. One study used a psychoanalytically informed analysis [ 40 ] and one used comparative analysis [ 41 ].

Following CASP quality appraisal, the methodological quality of included papers was ranked as either low ( n = 3), moderate ( n = 2) or high ( n = 12), (Table 2 ).

Of the included studies, seven focused on PND, four included patients with PND and/or emotional difficulties, postnatal blues or mental distress, two focused on mood disorders, four included women previously diagnosed with severe mental illnesses, eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, and/or traumatic childbirth/PTSD.

There were a total of 551 participants across the studies. Of these, 456 were married/cohabiting, 18 were single/separated, and 77 did not specify. For educational attainment, 321 participants identified as either ‘well educated’ or having studied beyond high school level. A total of 86 participants received a school education (high school or below), 14 participants had no schooling and 130 did not specify. Of the 17 studies, 15 were carried out in high-income countries and two in low-income countries (Table 3 ).

Through in-depth analysis of the data, three overarching themes: Vulnerabilities, Positive outcomes, and Challenges, emerged. These themes and associated sub themes are shown in Table 4 . The interplay among these major domains within the context of themes and subthemes are summarised in Fig. 2 .

Illustration of the interplay of themes and subthemes of the breastfeeding experiences of women with perinatal mental health problems PMH – Perinatal mental health

Theme: vulnerabilities

Expectations versus reality.

For some new mothers the reality of breastfeeding did not meet their expectations of being easy and ‘natural’, leaving them feeling unprepared and disillusioned when they experienced difficulties.

“You think you’re a completely useless mother and, you know, you should be able to know how to do this instinctively [breastfeeding] and in fact it’s probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done.” (25, p255).

Limited availability of antenatal breastfeeding advice led to mothers being unaware of the potential complexities of breastfeeding during the early days and weeks.

“Everyone make it seem like it’s natural because your body produces [milk]. It’s just something that should frequently come to you as soon as you have the baby., but it’s not like that. You had to hold the baby a certain way, you got to adjust your thing a certain way, you got to put the nipple in far enough for the baby to get it. There’s a lot to it. It’s really complicated.” (26, p5).

Self-perception as a mother

To be perceived as a ‘good mother’, by themselves and others, some women felt they must breastfeed at all costs. This perceived association of breastfeeding as the representation of ‘good mothering’, appeared to result in self-imposed pressure.

“I was so desperate to breastfeed him and I felt as if it was my, I felt as if I had some moral obligation as a mother and if I didn’t breast feed him I was badly letting him down.” (25, p255).

If these women were then unable to breastfeed, or if they faced significant breastfeeding difficulties, this sometimes led to feelings of guilt or inadequacy.

“There’s so much pressure on you to breastfeed. so you’re told that breast is best and you should do it and so when you don’t you think you are a failure and it’s what you should be doing.” (39, p322).

The opinions of family, friends and health professionals also played a significant part in the woman’s perception of her status as a ‘good mother’.

“The approval thing was a big factor. Everyone was telling me how well I’d done to keep breastfeeding. All that approval made me feel really good about myself, and that I was being a good mother to (baby). I wasn’t thinking negative thoughts about myself, I was feeling very positive really.” (35, p114).

However, for some mothers, this resulted in added pressure, causing them to hide their feelings and maintain an outward display of happiness.

“I didn’t want to talk with anybody about it, I always had to pretend that I was doing just great … I thought that wasn’t normal, that I was a bad mom who felt that way.” (37, p264).

Finding the right support could be very beneficial but some women had negative experiences of clinics or groups, undermining their self-belief.

“Daggers are drawn and everybody’s acting as if they can rule the world and the trouble is, when you’re depressed you just see that image and you think, I’m never going to be as good as this.” (39, p323).

Feelings of isolation felt by breastfeeding women were exacerbated by mental health issues, with Homewood et al. (39, p325) suggesting that breastfeeding could contribute to depression by increasing the sense of being trapped by the infant’s dependency.

“abandoned and alone … .scared all the time that something would happen to the baby…” (37, p264).

The sense of isolation was increased by the fact that seeking help could be difficult for women who were distressed because they were reluctant to reveal their negative feelings.

“I was feeling like really sad and just really isolated and really stuck!. . I just thought. . “How am I going to take care of this baby? And I am feeling so crappy!” I found it to be really hard just to reach out and admit that I was feeling the way that I was. I don’t know why I was so worried about being stigmatized, but I was. I just didn’t want that label of being a person with postpartum depression.” (32, p12) “.

Theme: positive outcomes

Bonding and closeness.

Whilst struggling with mental health issues, the experience of breastfeeding successfully could increase mothers’ positive feelings toward the baby, allowing them to enjoy time spent together and enhance their confidence.

“I used to feed her and it was the time I got a little lump in my throat and thought, oh, perhaps she’s not that bad, and I thought, this is perhaps how people feel a bit more of the time than I feel it.” (39, p323).

Some women reported that the physical aspect of breastfeeding allowed a connection that could compensate, to a degree, for the mental withdrawal caused by the depressive symptoms.

“I think [breastfeeding] helps because even if I feel like some days I’m not very connected emotionally, I know that at least I’m providing the baby with physical touch and bonding and all that. Even if I’m not mentally 100% there. So, I think it makes me feel better about myself as a mom.” (33, p641).

One mother noted that breastfeeding could reduce feelings of stress.

‘‘When I’m nursing her, I’m able to just hold her. And that just alleviates any worries, any stress that I’ve had through the day, just knowing that she needs me, that she’s finding comfort in me, that I’m able to comfort her. She’s comforting me at the same time.” (26, p5).

Sense of achievement

Achieving success with breastfeeding was a factor in mitigating some of the guilt that women with eating disorders might feel about the possible effects of their eating disorder on the baby, positively affecting their self-esteem.

“It wasn’t my instinct to want to breastfeed him but in the end I did. In some ways it made up for all the damage I thought I’d done to him because of my eating disorder.” (35, p113).

Some women who had experienced a traumatic birth perceived breastfeeding as having the potential to heal and reinforced their self-perception as a good mother.

“I would cover her up to feed her and hide her little head in the clothing. Not because of dignity, but because I did not want anyone else to see the magic and healing that was happening between us. Being able to breastfeed my daughter, despite all the odds, is my proudest achievement in life. I wear it in my soul as a badge of honor.” (29, p233).

Women described how breastfeeding was within their sphere of control whereas other aspects of motherhood were not.

“[Breastfeeding] was the one thing that I could control. . I think that it made me feel better because it was the one thing that I was successful at, as a mom, because my birth went so shitty, and everything just kind of spiraled down and my mood and everything. . .I lean on [breastfeeding] a lot. It is my thing with her that no one can take away. . .I don’t like other people doing it. I don’t even like the suggestion of other people doing it.” (32, p12).

Theme: challenges

Striving for control.

Some women with eating disorders perceived stopping breastfeeding as the only way to allow them to resume control over their body and their eating.

“I wanted my body back and I knew I wouldn’t get it back until I’d stopped breastfeeding. I knew the minute that stopped feeding him I could control my food again and that’s what I wanted. When I was feeding I needed to eat properly because he needs the nutrients.” (35, p114).

For women with obsessive compulsive disorder [ 30 ], some responded to contamination fears by breastfeeding, sometimes for much longer than planned.

“I forced myself to breastfeed for the whole of the first year because I was convinced that formula would be contaminating his body.” (30, p317).

Other women with eating disorders chose not to breastfeed in order to allow themselves to return to purging and undertaking strenuous exercise in order to lose their pregnancy weight rapidly [ 35 ].

Some still struggled between eating a ‘good’ diet to produce ‘healthy’ milk and the desire to return to their usual strategies such as restricted eating or purging.

“I didn’t need to make myself sick so often [when breastfeeding] but that wasn’t because I didn’t want to! [Laughs] I had to fight with myself all the time to control the urge. I thought breastfeeding would take that urge away but it didn’t. It eased a bit but I was still vomiting all the time I was breastfeeding.” (35, p112).

Inconsistent advice and lack of support

Women’s difficulties and lack of confidence with breastfeeding were increased by inconsistent advice from both professionals and family [ 25 ]. Mothers frequently made reference to seeking advice from healthcare professionals during the early weeks of breastfeeding but felt they were often left unsupported.

“I was alone and . the nurse often didn’t answer the buzzer, my buzzer when I was trying to breast feed and things. Again I felt so kind of, incredibly sensitive about everything, and anxious about everything, and they just weren’t there, were never there for me.” (25, p256).

Mothers described feeling pressurised by healthcare professionals to continue breastfeeding [ 35 ] and, without adequate support, women would often turn to friends or relatives for infant feeding advice [ 25 ].

Concerns over medication safety

Concerns regarding medication safety and breastfeeding [ 26 , 27 , 34 ] led some women to discount breastfeeding as an option for them.

“….I could try and breastfeed, but yeah, I decided that wasn’t—a good idea. Because it’s too hard and I wouldn’t be able to go back on my medication—right away after the baby was born. You have to wait two months, or something like that. So I thought that was dangerous— for both of us.” (34, p383).

Whilst others discontinued breastfeeding due to health concerns for the baby.

“And I had to get my wisdom teeth pulled out, so I decided to stop because they put you on antibiotics and stuff like that. So I just stopped.”(26, p5).

Some women with severe mental illness felt that due to the complexities of their mental health, breastfeeding was not considered relevant and was “de-prioritized” for other aspects of acute care [ 27 ]. Despite many mothers expressing strong preferences to continue breastfeeding, the mothers often felt that their preferences were ignored.

“Medication was an issue as I was initially given medication that specified it should not be taken while breastfeeding, when I had made my wish to breastfeed very clear.” (27, p7).

Some women felt that they needed to prompt staff to consider whether the medication they were prescribed would allow breastfeeding, or, alternatively, be given the choice to cease breastfeeding to allow them to have the most suitable medication to treat their mental health condition.

“I wish they had told me to stop breastfeeding rather than give me diluted medication.” (27, p6).

Others described being given contradictory information from health professionals about breastfeeding whilst taking psychotropic medication:

“Early in pregnancy, the mental health midwife said not to take fluoxetine if breastfeeding and to change to sertraline or citalopram. Next time I saw her later on and she said I could stay on fluoxetine if I was happy on it.” (27, p6).

Such conflicting advice made mothers confused and distressed. A resultant lack of confidence in healthcare professionals “ prompted some women to conduct their own research or to disregard medical advice ” (27, p6).

Perceived impact on milk quality and supply

There was a perception that women with PMH conditions would be unable to produce a sufficient quality and/or volume of breastmilk to sustain their baby nutritionally. This concern could potentially generate feelings of depression for women [ 26 ].

Some mothers perceived that their own poor nutrition could potentially cause problems with breastfeeding. This concern was often associated with eating disorders [ 26 ], food unavailability or lack of appetite due to mental ill health [ 38 , 41 ]. For women with eating disorders there was a belief that frequent cycles of binging and purging were not compatible with producing sufficient good quality breast milk. This caused some women to discount breastfeeding, and some received pressure from partners to bottle feed in the belief that the child would not receive the necessary nutrition.

“He (husband) didn’t want me to breastfeed because he thought I wasn’t eating enough to feed her (baby) properly. [.] He was on and on about me giving her the bottle. He even dragged my sister in to try and get her to talk me round.” (35, p111).

Some women with eating disorders did wish to breastfeed and commented on needing to change their eating patterns to achieve this.

“I had to eat properly when I was breastfeeding because I had a baby to think about. The baby needs nutrition. I thought whatever I eat the baby is going to get it. So I had to eat properly. Like when I was pregnant I made myself eat properly.” (35, p112).

Depression and anxiety are a common problem in the perinatal period, and pregnancy and childbirth can put women at risk of relapse or exacerbation of pre-existing mental illness [ 17 ]. Although postpartum anxiety is more prevalent than postpartum depression [ 42 ] we did not find any studies of women’s experiences of anxiety and breastfeeding. In this review there were examples of specific mental illnesses being associated with specific issues in relation to breastfeeding along with the difficulties faced by many women. Data from the included studies replicated what is already known regarding the relationship between perinatal depression and breastfeeding, that this relationship is bidirectional, with evidence of depressive symptoms contributing to worse breastfeeding outcomes and breastfeeding challenges sometimes serving as a trigger for postnatal depressive symptoms [ 43 ].

In this study it was found that, for mothers who were struggling with their mental health, the sense of achievement obtained by successful breastfeeding could boost their self-esteem and bolster the perception of themselves as a good mother [ 29 , 32 , 40 ]. These mothers found that breastfeeding could increase their mother/child bond and reinforce their confidence as a mother and felt that the closeness experienced during breastfeeding could reduce feelings of stress and compensate their baby for times when they were feeling withdrawn [ 26 , 33 , 35 , 39 ].

However, the perception that ‘good mothering’ is defined by successful breastfeeding can also result in overwhelming pressure for mothers, who may feel obliged to breastfeed despite experiencing challenges [ 44 , 45 , 46 ]. This pressure can then be further compounded by the attitudes and behaviours of healthcare professionals, family members and society in general [ 46 ]. A large proportion of the women in the included studies had a strong intention to breastfeed [ 25 , 28 , 31 , 33 , 37 ] and were often motivated to continue, despite difficulties, because of the pressure they placed on themselves to fulfil the role of the ‘good mother’. If they then had difficulties or ceased breastfeeding they often experienced feelings of guilt, inadequacy, and failure [ 25 , 27 , 40 ].

There is a wealth of literature describing the guilt and despair experienced when women’s expectations for breastfeeding to occur naturally, the desire to be a good mother, and ‘breast is best’, clash with the demands and labour-intensive workload that breastfeeding often entails [ 43 , 44 , 47 , 48 ]. A lack of antenatal education regarding potential breastfeeding challenges appears to be evident, with much of this being dedicated to the benefits of breastfeeding to both mother and baby, and although this information is important, it can provide a skewed ideal of the breastfeeding process [ 47 ]. Findings from studies by Hoddinott et al. [ 47 ] and Redshaw and Henderson [ 48 ] suggested realistic antenatal education is key to preparing women for common difficulties and suggest providing a realistic view rather than rosy pictures or patronising breastfeeding workshops with knitted breasts and dolls [ 47 ]. This lack of preparation for the challenges that frequently arise during the early days of breastfeeding can result in mothers feeling inadequate and unable to cope [ 45 , 46 ], potentially resulting in early discontinuation of breastfeeding and/or a decline in mental wellbeing.

The perception that mental health conditions can lead to insufficient or poor-quality breast milk is a common perception amongst breastfeeding women. A systematic review of breastfeeding problems by Karaçam and Sağlık, [ 49 ], found that 12 out of 34 studies referred problems such as “inadequate breastmilk/lack of breastmilk/ concern for inadequate breastmilk/thought that the baby was not satiated adequately/inadequate weight gain.” The theme was again identified by this study, particularly amongst those with eating disorders [ 29 , 35 ] and women from the two African based studies [ 38 , 41 ]. Women’s perceptions were primarily that poor mental health leads to inadequate nutritional intake (due to lack of appetite/disordered eating) and therefore impacts breastmilk volume and quality. This added burden of believing that their breastmilk may not adequately sustain their child could potentially further impact their mental health as a perceived failure [ 29 ].

For some women a sense of isolation in their role as carer, and specifically regarding breastfeeding was expressed in the included studies [ 25 , 32 , 34 ]. The sense of isolation can be magnified both by the symptoms of mental health issues and the reluctance of the mothers to reveal their condition, either pre-existing or newly emerging, to their loved ones and health professionals, worrying about what they may think [ 30 , 32 , 37 ]. This is reflected in previous research, which found stigma associated with mental ill health, compounded by a pervasive social stigma attached to being seen to ‘fail’ as a mother, leads to under-reporting of perinatal mental health issues [ 50 ]. A study of Australian women undergoing routine psychosocial assessment also found that 11.1% reported they were not always honest in the assessment and lack of trust in the midwife was the most frequent reason for non-disclosure [ 51 ]. Failure to reveal previous mental health issues may lead to inappropriate or sub-optimal advice [ 35 ].

The findings also identified that a lack of trust in the support and advice given by health professionals was also a contributing factor when considering medication safety and was stated as a reason to cease or not commence breastfeeding [ 27 , 34 ]. These inconsistencies sometimes prompted women to undertake their own research to gain answers [ 27 ], which could potentially lead to serious health consequences. The concerns held by women regarding medication safety and breastfeeding were highlighted in a Swedish study [ 52 ] which found that 57.7% of pregnant participants classed medication use during breastfeeding as harmful/probably harmful.

This lack of consistent advice regarding medication safety is largely due to a lack of high-quality evidence [ 53 ]. However, for those requiring medication during the postnatal period, clearer guidance is needed from healthcare professionals on the suitability of each type of medication when breastfeeding, and whether alternative medications can be considered so that breastfeeding can be undertaken safely without additional worry. Some women in the study felt they did not have the opportunity to make an informed choice regarding their medication and that desire to breastfeed was deprioritised over their mental health [ 27 ]. However, findings from this and previous studies have shown that when breastfeeding is successful it can improve mood and help protect against postnatal depression [ 32 , 33 , 54 , 55 ], as well as strengthen mother-child bonding [ 26 , 33 ]. It may therefore be the case that, in conjunction with suitable medication, breastfeeding may further help to boost mood and improve the overall wellbeing of the mother by providing a sense of achievement and control.

Negative attitudes towards diagnosis and treatment of perinatal mental health conditions result in women avoiding help seeking and reinforces feelings of stigma and guilt. Organisational-level factors such as inadequate resources, fragmentation of services and poor interdisciplinary communication compound these individual-level issues [ 50 , 56 ]. Structural factors (especially poor policy implementation) and sociocultural factors (for example language barriers) also cause significant barriers to accessing services for this group of women [ 50 , 56 ].

A strength of this review is the inclusion of literature regarding various mental health conditions (not purely depression) which had not been previously synthesised. This review highlights that each mental health condition may impact differently on breastfeeding experiences and merits separate investigation to inform policy and practice. The findings from this synthesis were based on a systematic literature search of five electronic databases. Inductive and in-depth analysis, using an iterative approach, allowed for immersion in the data, which strengthened the review findings.

Limitations were similar to those identified by previous studies relating to maternal mental health needs [ 57 ]. Participants were predominantly white and well educated, and studies were primarily undertaken in high income countries. This means that the findings may not be applicable to all women particularly those from low-income countries who may have different experiences and needs. None of the included studies incorporated the views and experiences of women from low socioeconomic status specifically, who are more likely to experience PMH conditions [ 47 ]. A comparison of the breastfeeding experiences of women with PMH conditions between different countries was beyond the scope of this review, however it must be acknowledged that differences are expected due to variations in culture, health systems, resource, and infant feeding attitudes.

The methods of diagnosing mental health conditions differed between studies. Some participants had a clinical diagnosis, whilst some were included based upon tools such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, or a self-diagnosis of distress/depression. This allowed us to increase the scope of studies included but may mean that some studies included women who may have not met the criteria for a clinal diagnosis of depression.

To ensure completeness prior to publication, the original search was again undertaken to capture any studies published between November 2021 and February 2024. The search identified two further papers which met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Both papers supported the original themes found in the study and therefore further validated the findings. Scarborough et al. [ 58 ] reported a perceived pressure to breastfeed, mixed impact on the mental health of the mother and the mother infant bond, and challenges receiving adequate information and support. Frayne et al. [ 59 ] highlighted the importance of good communication, consistency of advice, and shared decision making for women taking psychotropic medication, and the challenges faced if these aspects were not achieved.

There is a complex dynamic relationship amongst breastfeeding intention, practice, and experiences for mothers with PMH conditions. The intensity and magnitude of positive outcomes that women describe, and the challenges experienced, are exacerbated in mothers with PMH conditions. The challenging experiences are particularly influenced by a lack of support, shame, fear of stigmatisation and additional health concerns, such as worries over medication safety.

The synthesis identified inconsistent advice from healthcare professionals, particularly in relation to medication. Further training and improved communication pathways between specialities may help enhance perinatal maternity care provision. An in depth understanding of the women’s views/needs in relation to their specific PMH condition could help enhance their experiences of infant feeding. This will help women to make informed choices about feeding, increasing their sense of control and improving self-efficacy, which could have a positive impact on their emotional and physical wellbeing, their ability to bond with their baby and their transition to motherhood.

Gaps identified through this systematic review include the need for further investigation on breastfeeding and PMH in women from minority groups, as well as a need for robust evidence and advice on medication use during breastfeeding for women experiencing perinatal mental ill health.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC. Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Breastfeeding and intelligence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015a;104:14–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13139 .

Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015b;104:30–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13133 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, Piwoz EG, Richter LM, Victora CG. Lancet Breastfeeding Series. Why invest, and what will it take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 .

United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda [Accessed 12th May 2021].

World Health Organisation. Breastfeeding . https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_3 [Accessed 12 May 2021].

McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, Buchanan P, Taylor JL, Veitch E, Rennie AM, Crowther SA, Neiman S, MacGillivray S. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2017;2017(2):CD001141–001141. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub5 .

Article Google Scholar

Skouteris H, Bailey C, Nagle C, Hauck Y, Bruce L, Morris H. Interventions designed to promote exclusive breastfeeding in high-income countries: a systematic review update. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12(10):604–14. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2017.0065 .

Public Health England. Breastfeeding prevalence at 6 to 8 weeks after birth (experimental statistics). London: TSO; 2021.

Google Scholar