Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

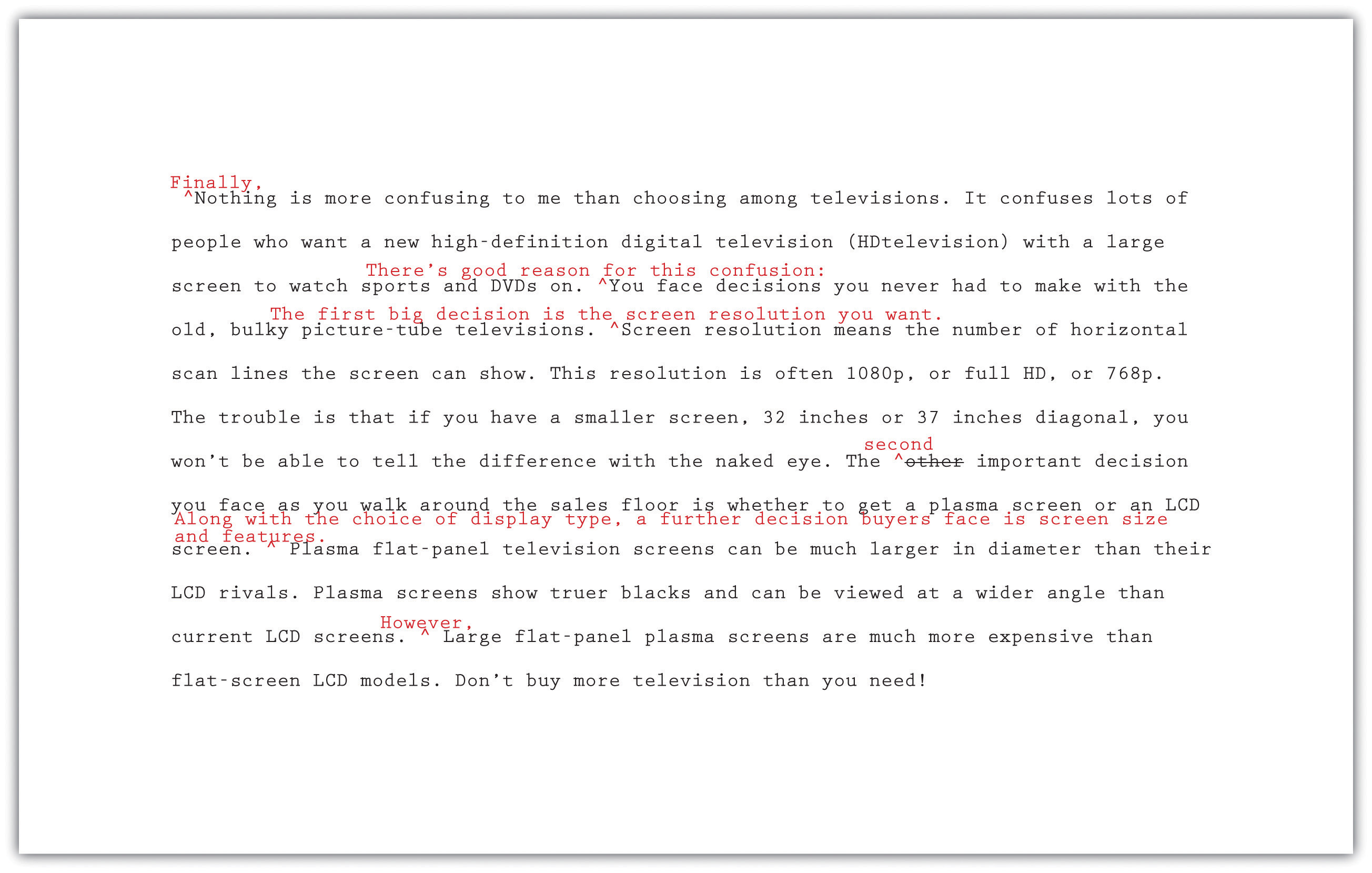

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | first, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |

| in the final analysis | therefore | thus |

| consequently | furthermore | additionally |

| because | besides the fact | following this idea further |

| in addition | in the same way | moreover |

| looking further | considering…, it is clear that | |

| but | yet | however |

| nevertheless | on the contrary | on the other hand |

| above all | best | especially |

| in fact | more important | most important |

| most | worst | |

| finally | last | in conclusion |

| most of all | least of all | last of all |

| admittedly | at this point | certainly |

| granted | it is true | generally speaking |

| in general | in this situation | no doubt |

| no one denies | obviously | of course |

| to be sure | undoubtedly | unquestionably |

| for instance | for example | |

| first, second, third | generally, furthermore, finally | in the first place, also, last |

| in the first place, furthermore, finally | in the first place, likewise, lastly | |

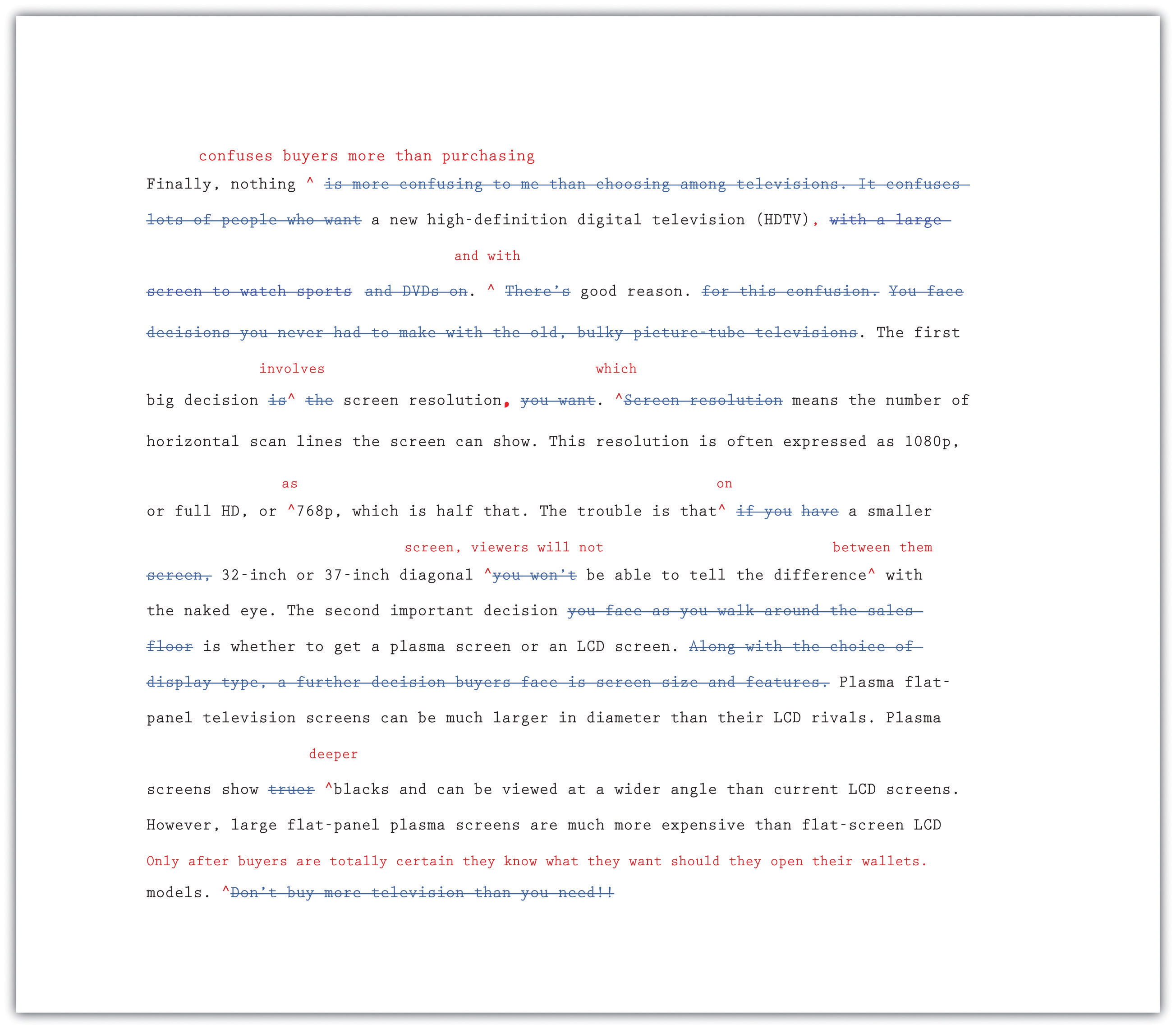

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

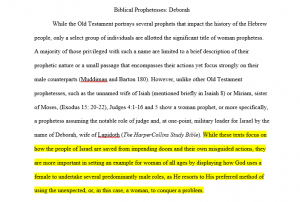

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

- Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

- Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

- Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

- Readers do not cheer when you use there , their , and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

- Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document..

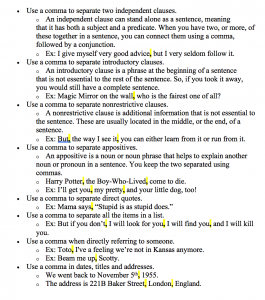

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

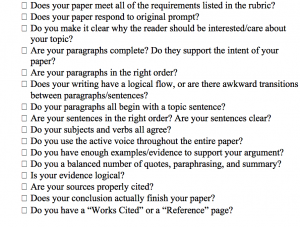

Editing Your Writing

- Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

- Are some sentences run-on sentences? How can I correct them?

- Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

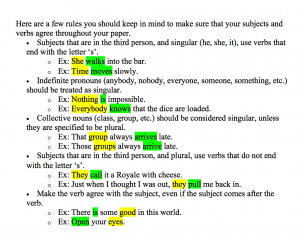

- Does every verb agree with its subject?

- Is every verb in the correct tense?

- Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

- Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

- Have I used who and whom correctly?

- Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

- Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

- Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

- Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

- Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

- Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

- Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

- Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

- Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

- Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

- Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

- Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

- Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

- Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

- Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

- Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to / too / two ?

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Steps for Revising Your Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you have plenty of time to revise, use the time to work on your paper and to take breaks from writing. If you can forget about your draft for a day or two, you may return to it with a fresh outlook. During the revising process, put your writing aside at least twice—once during the first part of the process, when you are reorganizing your work, and once during the second part, when you are polishing and paying attention to details.

Use the following questions to evaluate your drafts. You can use your responses to revise your papers by reorganizing them to make your best points stand out, by adding needed information, by eliminating irrelevant information, and by clarifying sections or sentences.

Find your main point.

What are you trying to say in the paper? In other words, try to summarize your thesis, or main point, and the evidence you are using to support that point. Try to imagine that this paper belongs to someone else. Does the paper have a clear thesis? Do you know what the paper is going to be about?

Identify your readers and your purpose.

What are you trying to do in the paper? In other words, are you trying to argue with the reading, to analyze the reading, to evaluate the reading, to apply the reading to another situation, or to accomplish another goal?

Evaluate your evidence.

Does the body of your paper support your thesis? Do you offer enough evidence to support your claim? If you are using quotations from the text as evidence, did you cite them properly?

Save only the good pieces.

Do all of the ideas relate back to the thesis? Is there anything that doesn't seem to fit? If so, you either need to change your thesis to reflect the idea or cut the idea.

Tighten and clean up your language.

Do all of the ideas in the paper make sense? Are there unclear or confusing ideas or sentences? Read your paper out loud and listen for awkward pauses and unclear ideas. Cut out extra words, vagueness, and misused words.

Visit the Purdue OWL's vidcast on cutting during the revision phase for more help with this task.

Eliminate mistakes in grammar and usage.

Do you see any problems with grammar, punctuation, or spelling? If you think something is wrong, you should make a note of it, even if you don't know how to fix it. You can always talk to a Writing Lab tutor about how to correct errors.

Switch from writer-centered to reader-centered.

Try to detach yourself from what you've written; pretend that you are reviewing someone else's work. What would you say is the most successful part of your paper? Why? How could this part be made even better? What would you say is the least successful part of your paper? Why? How could this part be improved?

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening

Step 4: Revise

“Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it’s where the game is won or lost.” —William Zinsser, On Writing Well

What does it really mean to revise, and why is a it a separate step from editing? Look at the parts of the word revise : The prefix re- means again or anew , and – vise comes from the same root as vision —i.e., to see. Thus revising is “re-seeing” your paper in a new way. That is why revising here refers to improving the global structure and content of your paper, its organization and ideas , not grammar, spelling, and punctuation. That comes last.

Logically, we also revise before we edit because revising will most certainly mean adding and deleting and rewriting sentences and often entire paragraphs . And there is no sense in editing text that you are going to cut or editing and then adding material and having to edit again.

Revising is also part of the learning and discovery process discussed earlier. As you reread your paper, you may see weaknesses in your argument that need strengthening, and you may thus have to do a little more thinking and research . Or you may have to restructure your paper somewhat to make the argument more logical. Keep your mind open to the possibility of learning in this stage.

You also do not have to revise alone. Not only will your professor look at your paper, but your classmates, colleagues and friends are great resources for getting a fresh, outside look at your work. Be sure to ask them what does work—we all need encouragement, especially as writers—as well as what doesn’t.

Continue to step-by-step instructions for revising .

Editing and Proofreading

What this handout is about.

This handout provides some tips and strategies for revising your writing. To give you a chance to practice proofreading, we have left seven errors (three spelling errors, two punctuation errors, and two grammatical errors) in the text of this handout. See if you can spot them!

Is editing the same thing as proofreading?

Not exactly. Although many people use the terms interchangeably, editing and proofreading are two different stages of the revision process. Both demand close and careful reading, but they focus on different aspects of the writing and employ different techniques.

Some tips that apply to both editing and proofreading

- Get some distance from the text! It’s hard to edit or proofread a paper that you’ve just finished writing—it’s still to familiar, and you tend to skip over a lot of errors. Put the paper aside for a few hours, days, or weeks. Go for a run. Take a trip to the beach. Clear your head of what you’ve written so you can take a fresh look at the paper and see what is really on the page. Better yet, give the paper to a friend—you can’t get much more distance than that. Someone who is reading the paper for the first time, comes to it with completely fresh eyes.

- Decide which medium lets you proofread most carefully. Some people like to work right at the computer, while others like to sit back with a printed copy that they can mark up as they read.

- Try changing the look of your document. Altering the size, spacing, color, or style of the text may trick your brain into thinking it’s seeing an unfamiliar document, and that can help you get a different perspective on what you’ve written.

- Find a quiet place to work. Don’t try to do your proofreading in front of the TV or while you’re chugging away on the treadmill. Find a place where you can concentrate and avoid distractions.

- If possible, do your editing and proofreading in several short blocks of time. Your concentration may start to wane if you try to proofread the entire text at one time.

- If you’re short on time, you may wish to prioritize. Make sure that you complete the most important editing and proofreading tasks.

Editing is what you begin doing as soon as you finish your first draft. You reread your draft to see, for example, whether the paper is well-organized, the transitions between paragraphs are smooth, and your evidence really backs up your argument. You can edit on several levels:

Have you done everything the assignment requires? Are the claims you make accurate? If it is required to do so, does your paper make an argument? Is the argument complete? Are all of your claims consistent? Have you supported each point with adequate evidence? Is all of the information in your paper relevant to the assignment and/or your overall writing goal? (For additional tips, see our handouts on understanding assignments and developing an argument .)

Overall structure

Does your paper have an appropriate introduction and conclusion? Is your thesis clearly stated in your introduction? Is it clear how each paragraph in the body of your paper is related to your thesis? Are the paragraphs arranged in a logical sequence? Have you made clear transitions between paragraphs? One way to check the structure of your paper is to make a reverse outline of the paper after you have written the first draft. (See our handouts on introductions , conclusions , thesis statements , and transitions .)

Structure within paragraphs

Does each paragraph have a clear topic sentence? Does each paragraph stick to one main idea? Are there any extraneous or missing sentences in any of your paragraphs? (See our handout on paragraph development .)

Have you defined any important terms that might be unclear to your reader? Is the meaning of each sentence clear? (One way to answer this question is to read your paper one sentence at a time, starting at the end and working backwards so that you will not unconsciously fill in content from previous sentences.) Is it clear what each pronoun (he, she, it, they, which, who, this, etc.) refers to? Have you chosen the proper words to express your ideas? Avoid using words you find in the thesaurus that aren’t part of your normal vocabulary; you may misuse them.

Have you used an appropriate tone (formal, informal, persuasive, etc.)? Is your use of gendered language (masculine and feminine pronouns like “he” or “she,” words like “fireman” that contain “man,” and words that some people incorrectly assume apply to only one gender—for example, some people assume “nurse” must refer to a woman) appropriate? Have you varied the length and structure of your sentences? Do you tends to use the passive voice too often? Does your writing contain a lot of unnecessary phrases like “there is,” “there are,” “due to the fact that,” etc.? Do you repeat a strong word (for example, a vivid main verb) unnecessarily? (For tips, see our handouts on style and gender-inclusive language .)

Have you appropriately cited quotes, paraphrases, and ideas you got from sources? Are your citations in the correct format? (See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial for more information.)

As you edit at all of these levels, you will usually make significant revisions to the content and wording of your paper. Keep an eye out for patterns of error; knowing what kinds of problems you tend to have will be helpful, especially if you are editing a large document like a thesis or dissertation. Once you have identified a pattern, you can develop techniques for spotting and correcting future instances of that pattern. For example, if you notice that you often discuss several distinct topics in each paragraph, you can go through your paper and underline the key words in each paragraph, then break the paragraphs up so that each one focuses on just one main idea.

Proofreading

Proofreading is the final stage of the editing process, focusing on surface errors such as misspellings and mistakes in grammar and punctuation. You should proofread only after you have finished all of your other editing revisions.

Why proofread? It’s the content that really matters, right?

Content is important. But like it or not, the way a paper looks affects the way others judge it. When you’ve worked hard to develop and present your ideas, you don’t want careless errors distracting your reader from what you have to say. It’s worth paying attention to the details that help you to make a good impression.

Most people devote only a few minutes to proofreading, hoping to catch any glaring errors that jump out from the page. But a quick and cursory reading, especially after you’ve been working long and hard on a paper, usually misses a lot. It’s better to work with a definite plan that helps you to search systematically for specific kinds of errors.

Sure, this takes a little extra time, but it pays off in the end. If you know that you have an effective way to catch errors when the paper is almost finished, you can worry less about editing while you are writing your first drafts. This makes the entire writing proccess more efficient.

Try to keep the editing and proofreading processes separate. When you are editing an early draft, you don’t want to be bothered with thinking about punctuation, grammar, and spelling. If your worrying about the spelling of a word or the placement of a comma, you’re not focusing on the more important task of developing and connecting ideas.

The proofreading process

You probably already use some of the strategies discussed below. Experiment with different tactics until you find a system that works well for you. The important thing is to make the process systematic and focused so that you catch as many errors as possible in the least amount of time.

- Don’t rely entirely on spelling checkers. These can be useful tools but they are far from foolproof. Spell checkers have a limited dictionary, so some words that show up as misspelled may really just not be in their memory. In addition, spell checkers will not catch misspellings that form another valid word. For example, if you type “your” instead of “you’re,” “to” instead of “too,” or “there” instead of “their,” the spell checker won’t catch the error.

- Grammar checkers can be even more problematic. These programs work with a limited number of rules, so they can’t identify every error and often make mistakes. They also fail to give thorough explanations to help you understand why a sentence should be revised. You may want to use a grammar checker to help you identify potential run-on sentences or too-frequent use of the passive voice, but you need to be able to evaluate the feedback it provides.

- Proofread for only one kind of error at a time. If you try to identify and revise too many things at once, you risk losing focus, and your proofreading will be less effective. It’s easier to catch grammar errors if you aren’t checking punctuation and spelling at the same time. In addition, some of the techniques that work well for spotting one kind of mistake won’t catch others.

- Read slow, and read every word. Try reading out loud , which forces you to say each word and also lets you hear how the words sound together. When you read silently or too quickly, you may skip over errors or make unconscious corrections.

- Separate the text into individual sentences. This is another technique to help you to read every sentence carefully. Simply press the return key after every period so that every line begins a new sentence. Then read each sentence separately, looking for grammar, punctuation, or spelling errors. If you’re working with a printed copy, try using an opaque object like a ruler or a piece of paper to isolate the line you’re working on.

- Circle every punctuation mark. This forces you to look at each one. As you circle, ask yourself if the punctuation is correct.

- Read the paper backwards. This technique is helpful for checking spelling. Start with the last word on the last page and work your way back to the beginning, reading each word separately. Because content, punctuation, and grammar won’t make any sense, your focus will be entirely on the spelling of each word. You can also read backwards sentence by sentence to check grammar; this will help you avoid becoming distracted by content issues.

- Proofreading is a learning process. You’re not just looking for errors that you recognize; you’re also learning to recognize and correct new errors. This is where handbooks and dictionaries come in. Keep the ones you find helpful close at hand as you proofread.

- Ignorance may be bliss, but it won’t make you a better proofreader. You’ll often find things that don’t seem quite right to you, but you may not be quite sure what’s wrong either. A word looks like it might be misspelled, but the spell checker didn’t catch it. You think you need a comma between two words, but you’re not sure why. Should you use “that” instead of “which”? If you’re not sure about something, look it up.

- The proofreading process becomes more efficient as you develop and practice a systematic strategy. You’ll learn to identify the specific areas of your own writing that need careful attention, and knowing that you have a sound method for finding errors will help you to focus more on developing your ideas while you are drafting the paper.

Think you’ve got it?

Then give it a try, if you haven’t already! This handout contains seven errors our proofreader should have caught: three spelling errors, two punctuation errors, and two grammatical errors. Try to find them, and then check a version of this page with the errors marked in red to see if you’re a proofreading star.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Especially for non-native speakers of English:

Ascher, Allen. 2006. Think About Editing: An ESL Guide for the Harbrace Handbooks . Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Lane, Janet, and Ellen Lange. 2012. Writing Clearly: Grammar for Editing , 3rd ed. Boston: Heinle.

For everyone:

Einsohn, Amy. 2011. The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications , 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Tarshis, Barry. 1998. How to Be Your Own Best Editor: The Toolkit for Everyone Who Writes . New York: Three Rivers Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

writingxhumanities

A "how to" guide for UC Berkeley writers

Drafting | Revising | Editing

Keep in mind that your first draft is preliminary , meaning that you should feel free to experiment with many different ways of generating ideas , from brainstorming to mind-mapping to more traditional outlining to literally just beginning to write. If you think that you’re going to use a certain piece of evidence you found in your preliminary close reading of the text, you can start by simply writing a paragraph in which you use that evidence to make a tentative claim. This is a great way to conquer the fear of the blank page, and another benefit of using close reading to develop your argument!

In other words, you shouldn’t assume that you can’t start writing until you know exactly what you’re going to argue or what sequence in which you’ll present your claims and evidence. Likewise, you shouldn’t believe that just because you’ve written something, you can’t change it later, perhaps dramatically. Much like close reading and making an argument, drafting is an iterative and recursive process, which means that it proceeds in a looping way through multiple phases of repetition—your first draft is just a beginning, an early form of your essay that is open to change and subject to revision. You can narrow or refine your focus as you move through multiple drafts, and your essay is likely to evolve, both in argument and structure, as your drafting progresses. And that’s a good thing!

Some writers like to make a provisional outline before they begin drafting, while others begin to write with only a rough plan in mind. Whether you prefer to outline first or not here are some strategies for keeping your argument in focus before, during, and after drafting.

Sometimes “revision” and “editing” are used interchangeably, but each has a distinct role in the writing process–and each can help you to develop and refine your work in important ways. Revision is the process of contemplating and making changes to the conceptual or argument-driven work of an essay. In revision, you might refine your argument, examine the close readings and other forms of analysis that move your argument forward, or reconsider the structure that knits your ideas together.

Editing, on the other hand, means contemplating and making changes to the language with which we express our ideas. Editing helps us to “speak” more clearly: to correct our mechanical errors (grammar, typos, etc.), clarify our language, more smoothly integrate quotations or other citations, and so forth. Editing doesn’t ask, what am I trying to say? Instead, it asks: am I saying it well?

While both revising and editing are important parts of the writing process, it tends to be counterproductive to do both at the same time. Why spend time polishing sentences or paragraphs that you may end up cutting? And once you’ve spent time polishing your prose, it’s much harder to cut or rework that part of your essay!

When you first return to a draft for the purpose of revision, you should focus on larger questions of substance and structure. What is your argument? What evidence do you provide? Is your analysis convincing? Is your essay clearly organized? Revision often requires you to make “big” changes: you may need to re-focus your argument or refine your ideas; cut, move, or rewrite whole paragraphs; add additional sources or evidence; rework your introduction and/or conclusion to bring them in line with the argument you have made. Remember that rewriting is the key to good writing.

Here are some strategies you can use to revise an essay:

- As you tackle the revision process, consider your priorities for revision . What is the most important thing to work on? What next?

- Remember to approach revision as a multi-step process. You can make this process manageable by focusing on two or three areas during each revision session . Conclude the revision process by checking balance, assessing your organization, and asking if you’ve kept your promises to your readers.

- Generate a reverse outline , which is one of the most useful tools in the essay reviser’s toolbox. Whether you make your reverse outline in the margins of your draft or on a separate sheet of paper , this strategy will help you to see the overall structure of your argument as it stands in your draft, the first step in determining whether (and how) reorganizing the sequence of paragraphs might strengthen your argument. It can also help you determine whether all paragraphs are working to support your main claim; whether there are any redundant paragraphs (i.e., paragraphs that make the same point as other paragraphs without moving your argument forward); or whether there is any missing or unclear evidence.

- Consider whether your essay uses transitional words and phrases between paragraphs to clarify the arc of your argument.

- Consider whether your paragraphs themselves are clearly structured , with topic sentences and transitional sentences that signpost the development of your argument and don’t rely solely on the chronology of a text. (This will help you to avoid doing a plot summary or merely describing a text rather than doing an analysis!)

- All of these steps may help you to take the most important step of all: determining whether you have a sufficiently focused and compelling thesis that you have supported persuasively with textual evidence. (For more on developing a strong thesis, see What Are Some Critical Moves in an Argument? .)

- If you’ve already received feedback on your paper from your instructor, think about how you might incorporate their suggestions in your next draft or your next essay. Don’t be shy about arranging to meet with them to discuss their feedback and how you can best use it in revision and future essays.

Once you have reworked the structure of your argument in the revising phase, you’ll be ready to start editing. Editing means honing the language of your essay in order to make your argument clear, engaging, and persuasive to your reader. It can include editing to improve the style of your writing as well as to fix mechanical errors (a kind of editing often called proofreading). Mechanical details such as correct punctuation and grammar are fundamental to conveying your meaning to your reader. While unintentional errors like typos might seem trivial to you, prose that is typo-free will immediately help you gain your reader’s confidence.

Re-reading your paper carefully can help you find a variety of errors that a computer spell-checker might miss. In order to focus on the language of your own writing, try some of these editing strategies:

- Reading your paper aloud—or, even better, having a friend or your computer’s text-to-speech function read your paper aloud to you—is a great way to catch things your eye might miss on the page. As you hear your paper, listen for sentences that sound awkward. Trust your ear!

- Reading your sentences individually and out of context—editing each of the first sentences in each of your paragraphs, then the second sentences, etc.—is another way to focus on the form of your sentences rather than their content.

- Sometimes printing out your paper, especially if you’ve only looked at an electronic copy up to this point, can also help.

- Perhaps the best way to notice things you’ve missed is by setting your writing aside and coming back to it later. Take a break—you earned it!

Here’s a list of some additional editing strategies ; you might also consider the Paramedic Method , a streamlined approach to achieving persuasive and clear prose. And here are some resources to help with common grammatical errors:

- One-Stop Guide to Common Errors

- Basic Punctuation Rules

- Semi-colons, Colons, and Dashes

- Run-on Sentences

- Dangling Modifiers

Even if your writing is grammatically correct, you still need to edit it for style. Style—the way you put together a sentence or a group of sentences—is subjective; different people have different ideas about what sounds good. But the following guidelines can help you write lucidly, engagingly and, yes, stylishly.

- Use a voice or tone appropriate to the academic discipline in which you are working. New writers are often surprised, for example, that humanities essay writers sometimes use first person pronouns . When in doubt, ask your instructor for guidance and even for examples of the style of writing you are expected to do for their class.

- Avoid jargon and other kinds of over-inflated language. Use theoretical terms if they are critical to your argument, but make sure to define them for the reader. And always make sure that the word you’re using means what you think it means! Having a sure command of the language you are using not only assures the clarity of your writing, but it also helps to make your writing expressive and polished, contributing to the authority of your voice as a writer.

- Watch out for wordiness . When you streamline your prose, your reader will understand your idea more easily. Vary your diction to avoid sounding robotic, but don’t go overboard—sometimes you need to repeat words or phrases to help your reader follow the main thread of your argument. Likewise, vary sentence structure ( including sentence length) to create a feeling of flow, but never at the expense of clarity.

- In order to grasp what’s happening in a sentence, a reader needs to understand who or what is doing something and what it is they are doing. One way to make the subject and the verb of your sentence clear to your reader is by making sure the passive voice is avoided; for an example of unclear and “baggy” use of the passive voice, see the first half of this sentence! (Here’s one fix: “By avoiding the passive voice, you can help your reader to recognize your sentence’s subject and verb.” Here’s another: “To help your reader, avoid the passive voice!”) You should also avoid clunky nominalizations, also known as “ zombie nouns ,” which means using the noun form of a verb (such as “nominalization” instead of “nominalize”) or the noun form of an adjective (“implacability” instead of “implacable”). Of course, you may have a good reasons to use these grammatical forms in specific contexts; you might use the passive voice to describe the writing of an anonymous poem, for example, or employ a nominalization if it is a commonly used technical term such as “enjambment.” But otherwise, search for and replace passive verb constructions and nominalizations to make your sentences concrete, clear and lively.

For more general hints on improving your prose style, you can check out this overview or—as always—talk to your instructor!.

For additional materials, go to Teaching Drafting | Revising | Editing in the For Instructors section of this website.

Revising vs. Editing – What’s the Difference?

| Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond

Candace Osmond studied Advanced Writing & Editing Essentials at MHC. She’s been an International and USA TODAY Bestselling Author for over a decade. And she’s worked as an Editor for several mid-sized publications. Candace has a keen eye for content editing and a high degree of expertise in Fiction.

How is revising different from editing? This guide covers the main differences between editing and revising. It also provides examples of tasks under each stage.

What’s the Difference Between Revising and Editing a Paper?

The main difference between editing and revising is their focus. When one revises after the process of writing, they take a second look at your idea and information.

The process of revising makes a piece of writing stronger by making the ideas of the writer clearer. You also make the information more engaging, interesting, accurate, or compelling.

Meanwhile, the editing stage occurs at several levels. But the most common editing conventions include fixing the writing style.

Content editing, copy editing, and substantive editing involve fixing the sentence structure, grammar, and punctuation to make the ideas clearer.

The editing process can also be developmental. Here, the editor evaluates the “larger picture” of your work. They suggest changes to plot holes, character traits, dialogues, and sequences of stories.

Take your grammar skills to the next level

Take Our Copyediting Course

Similarities Between Editing and Revising

We know there is a connection between writing, editing , and revising. But the main similarity between the revising and editing process is that they both take place after the writing process. They also have the same goal of improving your original writing.

It’s not enough to finish an initial draft and only make a few changes afterward. All types of writing should undergo revising and editing to prevent slip-ups.

Understand the Difference Between Editing vs. Revising

Knowing the difference between them is crucial because it will help you decide which process you need for your writing.

Most deductions or errors in college essays are primarily due to careless editing. With that, it’s time to start revising and editing your papers before submitting them. One small mistake in your structure of writing could lead to a failing mark.

Another reason to know the difference is to help you understand the exact steps to take. You can’t spot all mistakes in your writing with only one editing pass. You must attempt several revising and editing passes to perfect and polish it.

What are the Three Stages of Revision and Editing?

The basic idea behind having several stages for revising is to make both big and small changes. The three stages involve:

- Revising, where one makes logical changes to the arguments and sequence of events.

- Editing, where one becomes a grammar police and corrects grammar and spelling errors.

- Proofreading, where one takes a final look at the text on a sentence level.

What Comes First, Revision or Editing?

Revising comes first before editing. This allows the writer to fix the accuracy of the information and strengthen their arguments.

Once the writer has finished making logical changes, they can start correcting grammar errors and other mistakes.

Revising and Editing Example

Consider this short paragraph as an example:

“Spending time with family has benefits for children. First, studies show that a close bond within the family keeps the house clean and organized. Second, it lowers childrens risk of behavioral problems. They are less likely to have issues with substance abuse or violence. Lastly, spending time with the famiy help children perform well academically.”

The revising stage may include the following tasks:

- The sentence “First, studies show that a close bond within the family keeps the house clean and organized” should be omitted, as it lacks relevance to the primary discussion regarding the benefits of family time for children.

- Including more supporting details for the main argument.

Meanwhile, editing involves:

- Changing “childrens” to “children’s.”

- Changing “famiy” to “family.”

- Changing “help” to “helps.”

Hiring an editor who can perform revisions and edits on your work is always a brilliant idea. Make sure they are a stickler for grammar and have sharp attention to detail. This is ideal for student writers and researchers who want to make fundamental improvements in their writing.

But some sophisticated writers and authors may opt to hire separate professionals for the two processes.

Editing and Revising Checklist

If you’re an English teacher, you can use this guide to check student writing, whether it’s a story, essay, or research paper.

The revision process is in charge of the traits of ideas and other traits of writing (voice, presentation, conventions, organization, fluency, word choice). Here are some revision tasks teachers, students, and writers should follow.

- Remove off-topic sentences.

- Add new information.

- Add spider-leg sentences (trait of ideas).

- Move sentences around.

- Variety of individual sentences (from the trait of sentence fluency).

- Perform story surgery or rearrange the whole text to make the story stronger.

Editing typically involves changing some words in your piece of writing to make it grammatically correct or correctly spelled. You may consult a reliable grammar checker to help you fix the remaining grammar mistakes you didn’t catch.

- Check for grammar and spelling mistakes.

- Proper punctuation.

- Sentence readability.

- Fix issues with sentence structure.

- Adding quotation marks.

- Make the flow of ideas logical by fixing mixed-up ideas

Revising vs. Editing Summary

Now you know the differences between editing and revising. Both processes are necessary to help you produce high-quality writing with sound arguments, clear information, and error-free text.

Remember that revising focuses on your ideas, arguments, and information. Editing refers to correcting spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

15 Tips for Writing, Proofreading, and Editing Your College Essay

What’s covered:, our checklist for writing, proofreading, and editing your essay, where to get your college essays edited.

Your college essay is more than just a writing assignment—it’s your biggest opportunity to showcase the person behind your GPA, test scores, and extracurricular activities. In many ways, it’s the best chance you have to present yourself as a living, breathing, and thoughtful individual to the admissions committee.

Unlike test scores, which can feel impersonal, a well-crafted essay brings color to your application, offering a glimpse into your passions, personality, and potential. Whether you’re an aspiring engineer or an artist, your college essay can set you apart, making it essential that you give it your best.

1. Does the essay address the selected topic or prompt?

Focus on responding directly and thoughtfully to the prompt. If the question asks about your reasons for choosing a specific program or your future aspirations, ensure that your essay revolves around these themes. Tailor your narrative to the prompt, using personal experiences and reflections that reinforce your points.

- Respond directly to the prompt: It’s imperative that you thoughtfully craft your responses so that the exact themes in the prompt are directly addressed. Each essay has a specific prompt that serves a specific purpose, and your response should be tailored in a way that meets that objective.

- Focus: Regardless of what the prompt is about—be it personal experiences, academic achievements, or an opinion on an issue—you must keep the focus of the response on the topic of the prompt .

2. Is the college essay well organized?

An essay with a clear structure is easier to follow and is more impactful. Consider organizing your story chronologically, or use a thematic approach to convey your message. Each paragraph should transition smoothly to the next, maintaining a natural flow of ideas. A well-organized essay is not only easier for the reader to follow, but it can also aid your narrative flow. Logically structured essays can guide the reader through complex and hectic sequences of events in your essay. There are some key factors involved in good structuring:

- A strong hook: Start with a sentence or a paragraph that can grab the attention of the reader. For example, consider using a vivid description of an event to do this.

- Maintain a thematic structure: Maintaining a thematic structure involves organizing your response around a central theme, allowing you to connect diverse points of your essay into a cohesive centralized response.

- Transitioning: Each paragraph should clearly flow into the next, maintaining continuity and coherence in narrative.

3. Include supporting details, examples, and anecdotes.

Enhance your narrative with specific details, vivid examples, and engaging anecdotes. This approach brings your story to life, making it more compelling and relatable. It helps the reader visualize your experiences and understand your perspectives.

4. Show your voice and personality.

Does your personality come through? Does your essay sound like you? Since this is a reflection of you, your essay needs to show who you are.

For example, avoid using vocabulary you wouldn’t normally use—such as “utilize” in place of “use”—because you may come off as phony or disingenuous, and that won’t impress colleges.

5. Does your essay show that you’re a good candidate for admission?

Your essay should demonstrate not only your academic strengths. but also the ways in which your personal qualities align with the specific character and values of the school you’re applying to . While attributes like intelligence and collaboration are universally valued, tailor your essay to reflect aspects that are uniquely esteemed at each particular institution.

For instance, if you’re applying to Dartmouth, you might emphasize your appreciation for, and alignment with, the school’s strong sense of tradition and community. This approach shows a deeper understanding of and a genuine connection to the school, beyond its surface-level attributes.

6. Do you stick to the topic?

Your essay should focus on the topic at hand, weaving your insights, experiences, and perspectives into a cohesive narrative, rather than a disjointed list of thoughts or accomplishments. It’s important to avoid straying into irrelevant details that don’t support your main theme. Instead of simply listing achievements or experiences, integrate them into a narrative that highlights your development, insights, or learning journey.

Example with tangent:

“My interest in performing arts began when I was five. That was also the year I lost my first tooth, which set off a whole year of ‘firsts.’ My first play was The Sound of Music.”

Revised example:

“My interest in performing arts began when I was five, marked by my debut performance in ‘The Sound of Music.’ This experience was the first step in my journey of exploring and loving the stage.”

7. Align your response with the prompt.

Before finalizing your essay, revisit the prompt. Have you addressed all aspects of the question? Make sure your essay aligns with the prompt’s requirements, both in content and spirit. Familiarize yourself with common college essay archetypes, such as the Extracurricular Essay, Diversity Essay, Community Essay, “Why This Major” Essay (and a variant for those who are undecided), and “Why This College” Essay. We have specific guides for each, offering tailored advice and examples:

- Extracurricular Essay Guide

- Diversity Essay Guide

- Community Essay Guide

- “Why This Major” Essay Guide

- “Why This College” Essay Guide

- Overcoming Challenges Essay Guide

- Political/Global Issues Essay Guide

While these guides provide a framework for each archetype, respectively, remember to infuse your voice and unique experiences into your essay to stand out!

8. Do you vary your sentence structure?

Varying sentence structure, including the length of sentences, is crucial to keep your writing dynamic and engaging. A mix of short, punchy sentences and longer, more descriptive ones can create a rhythm that makes your essay more enjoyable to read. This variation helps maintain the reader’s interest and allows for more nuanced expression.

Original example with monotonous structure:

“I had been waiting for the right time to broach the topic of her health problem, which had been weighing on my mind heavily ever since I first heard about it. I had gone through something similar, and I thought sharing my experience might help.”

Revised example illustrating varied structure:

“I waited for the right moment to discuss her health. The issue had occupied my thoughts for weeks. Having faced similar challenges, I felt that sharing my experience might offer her some comfort.”

In this revised example, the sentences vary in length and structure, moving from shorter, more impactful statements to longer, more descriptive ones. This variation helps to keep the reader’s attention and allows for a more engaging narrative flow.

9. Revisit your essay after a break.

- Give yourself time: After completing a draft of your essay, step away from it for a day or two. This break can clear your mind and reduce your attachment to specific phrases or ideas.

- Fresh perspective: When you come back to your essay, you’ll likely find that you can view your work with fresh eyes. This distance can help you spot inconsistencies, unclear passages, or stylistic issues that you might have missed earlier.

- Enhanced objectivity: Distance not only aids in identifying grammatical errors or typos, but it also allows you to assess the effectiveness of your argument or narrative more objectively. Does the essay really convey what you intended? Are there better examples or stronger pieces of evidence you could use?

- Refine and polish: Use this opportunity to fine-tune your language, adjust the flow, and ensure that your essay truly reflects your voice and message.

Incorporating this tip into your writing process can significantly improve the quality and effectiveness of your college essay.

10. Choose an ideal writing environment.

By identifying and consistently utilizing an ideal writing environment, you can enhance both the enjoyment and effectiveness of your essay-writing process.

- Discover your productive spaces: Different environments can dramatically affect your ability to think and write effectively. Some people find inspiration in the quiet of a library or their room, while others thrive in the lively atmosphere of a coffee shop or park.

- Experiment with settings: If you’re unsure what works best for you, try writing in various places. Notice how each setting affects your concentration, creativity, and mood.

- Consider comfort and distractions: Make sure your chosen spot is comfortable enough for long writing sessions, but also free from distracting elements that could hinder your focus.

- Time of day matters: Pay attention to the time of day when you’re most productive. Some write best in the early morning’s tranquility, while others find their creative peak during nighttime hours.

11. Are all words spelled correctly?

While spell checkers are a helpful tool, they aren’t infallible. It’s crucial to read over your essay meticulously, possibly even aloud, to catch any spelling errors. Reading aloud can help you notice mistakes that your eyes might skip over when reading silently. Be particularly attentive to words that spellcheck might not catch, such as proper nouns, technical jargon, or homophones (e.g., “there” vs. “their”). Attention to detail in spelling reflects your care and precision, both of which are qualities that admissions committees value.

12. Do you use proper punctuation and capitalization?

Correct punctuation and capitalization are key to conveying your message clearly and professionally . A common mistake in writing is the misuse of commas, particularly in complex sentences.

Example of a misused comma:

Incorrect: “I had an epiphany, I was using commas incorrectly.”

In this example, the comma is used incorrectly to join two independent clauses. This is known as a comma splice. It creates a run-on sentence, which can confuse the reader and disrupt the flow of your writing.

Corrected versions:

Correct: “I had an epiphany: I was using commas incorrectly.”

Correct: “I had an epiphany; I was using commas incorrectly.”

Correct: “I had an epiphany—I was using commas incorrectly.”

Correct: “I had an epiphany. I was using commas incorrectly.”

The corrections separate the two clauses with more appropriate punctuation. Colons, semicolons, em dashes, and periods can all be used in this context, though periods may create awkwardly short sentences.

These punctuation choices are appropriate because the second clause explains or provides an example of the first, creating a clear and effective sentence structure. The correct use of punctuation helps maintain the clarity and coherence of your writing, ensuring that your ideas are communicated effectively.

13. Do you abide by the word count?

Staying within the word count is crucial in demonstrating your ability to communicate ideas concisely and effectively. Here are some strategies to help reduce your word count if you find yourself going over the prescribed limits:

- Eliminate repetitive statements: Avoid saying the same thing in different ways. Focus on presenting each idea clearly and concisely.

- Use adjectives judiciously: While descriptive words can add detail, using too many can make your writing feel cluttered and overwrought. Choose adjectives that add real value.

- Remove unnecessary details: If a detail doesn’t support or enhance your main point, consider cutting it. Focus on what’s essential to your narrative or argument.

- Shorten long sentences: Long, run-on sentences can be hard to follow and often contain unnecessary words. Reading your essay aloud can help you identify sentences that are too lengthy or cumbersome. If you’re out of breath before finishing a sentence, it’s likely too long.

- Ensure each sentence adds something new: Every sentence should provide new information or insight. Avoid filler or redundant sentences that don’t contribute to your overall message.

14. Proofread meticulously.

Implementing a thorough and methodical proofreading process can significantly elevate the quality of your essay, ensuring that it’s free of errors and flows smoothly.

- Detailed review: After addressing bigger structural and content issues, focus on proofreading for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. This step is crucial for polishing your essay and making sure it’s presented professionally.

- Different techniques: Employ various techniques to catch mistakes. For example, read your essay backward, starting from the last sentence and working your way to the beginning. This method can help you focus on individual sentences and words, rather than getting caught up in the content.

- Read aloud: As mentioned before, reading your essay aloud is another effective technique. Hearing the words can help identify awkward phrasing, run-on sentences, and other issues that might not be as obvious when reading silently.

15. Utilize external feedback.

While self-editing is crucial, external feedback can provide new perspectives and ideas that enhance your writing in unexpected ways. This collaborative process can help you keep your essay error-free and can also help make it resonate with a broader audience.

- Fresh perspectives: Have a trusted teacher, mentor, peer, or family member review your drafts. Each person can offer unique insights and perspectives on your essay’s content, structure, and style.

- Identify blind spots: We often become too close to our writing to see its flaws or areas that might be unclear to others. External reviewers can help identify these blind spots.

- Constructive criticism: Encourage your reviewers to provide honest, constructive feedback. While it’s important to stay true to your voice and story, be open to suggestions that could strengthen your essay.

- Diverse viewpoints: Different people will focus on different aspects of your writing. For example, a teacher might concentrate on your essay’s structure and academic tone, while a peer might provide insights into how engaging and relatable your narrative is.

- Incorporate feedback judiciously: Use the feedback to refine your essay, but remember that the final decision on any changes rests with you. It’s your story and your voice that ultimately need to come through clearly.

When it comes to refining your college essays, getting external feedback is crucial. Our free Peer Essay Review tool allows you to receive constructive criticism from other students, providing fresh perspectives that can help you see your work in a new light. This peer review process is invaluable and can help you both identify areas for improvement and gain different viewpoints on your writing.