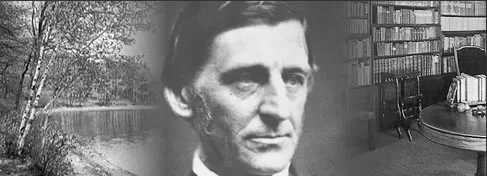

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American Transcendentalist poet, philosopher and essayist during the 19th century. One of his best-known essays is "Self-Reliance.”

(1803-1882)

Who Was Ralph Waldo Emerson?

In 1821, Ralph Waldo Emerson took over as director of his brother’s school for girls. In 1823, he wrote the poem "Good-Bye.” In 1832, he became a Transcendentalist, leading to the later essays "Self-Reliance" and "The American Scholar." Emerson continued to write and lecture into the late 1870s.

Early Life and Education

Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on May 25, 1803, in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the son of William and Ruth (Haskins) Emerson; his father was a clergyman, as many of his male ancestors had been. He attended the Boston Latin School, followed by Harvard University (from which he graduated in 1821) and the Harvard School of Divinity. He was licensed as a minister in 1826 and ordained to the Unitarian church in 1829.

Emerson married Ellen Tucker in 1829. When she died of tuberculosis in 1831, he was grief-stricken. Her death, added to his own recent crisis of faith, caused him to resign from the clergy.

Travel and Writing

In 1832 Emerson traveled to Europe, where he met with literary figures Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. When he returned home in 1833, he began to lecture on topics of spiritual experience and ethical living. He moved to Concord, Massachusetts, in 1834 and married Lydia Jackson in 1835.

American Transcendentalism

In the 1830s Emerson gave lectures that he afterward published in essay form. These essays, particularly “Nature” (1836), embodied his newly developed philosophy. “The American Scholar,” based on a lecture that he gave in 1837, encouraged American authors to find their own style instead of imitating their foreign predecessors.

Emerson became known as the central figure of his literary and philosophical group, now known as the American Transcendentalists. These writers shared a key belief that each individual could transcend, or move beyond, the physical world of the senses into deeper spiritual experience through free will and intuition. In this school of thought, God was not remote and unknowable; believers understood God and themselves by looking into their own souls and by feeling their own connection to nature.

The 1840s were productive years for Emerson. He founded and co-edited the literary magazine The Dial , and he published two volumes of essays in 1841 and 1844. Some of the essays, including “Self-Reliance,” “Friendship” and “Experience,” number among his best-known works. His four children, two sons and two daughters, were born in the 1840s.

Later Work and Life

Emerson’s later work, such as The Conduct of Life (1860), favored a more moderate balance between individual nonconformity and broader societal concerns. He advocated for the abolition of slavery and continued to lecture across the country throughout the 1860s.

By the 1870s the aging Emerson was known as “the sage of Concord.” Despite his failing health, he continued to write, publishing Society and Solitude in 1870 and a poetry collection titled Parnassus in 1874.

Emerson died on April 27, 1882, in Concord. His beliefs and his idealism were strong influences on the work of his protégé Henry David Thoreau and his contemporary Walt Whitman, as well as numerous others. His writings are considered major documents of 19th-century American literature, religion and thought.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Birth Year: 1803

- Birth date: May 25, 1803

- Birth State: Massachusetts

- Birth City: Boston

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Ralph Waldo Emerson was an American Transcendentalist poet, philosopher and essayist during the 19th century. One of his best-known essays is "Self-Reliance.”

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Fiction and Poetry

- Education and Academia

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- Boston Public Latin School

- Harvard University

- Harvard Divinity School

- Death Year: 1882

- Death date: April 27, 1882

- Death State: Massachusetts

- Death City: Concord

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.

- The only reward of virtue is virtue; the only way to have a friend is to be one.

- Nature never hurries: atom by atom, little by little, she achieves her work.

Philosophers

Marcus Garvey

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

- Biographies

- Special Features

- Denominational Administration & Governance

Religious Education

- Related Organizations

- General Assembly Minutes

The Schooling of Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Living Legacy of Ralph Waldo Emerson

The early education Emerson received at home would serve him well in school. His mother had introduced him to readings that were spiritual and emphasized self-knowledge and religious self-cultivation. His aunt, Mary Moody Emerson, exposed him to great thinkers present and past and challenged him to think independently. Another relative, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, knew languages, literature, science, and philosophy and tutored boys for entrance to Harvard College. Emerson was well nourished by this extraordinary circle of intellectual and spiritual women, and their friends, who set a high standard of learning and accomplishment in the Emerson home.

From 1812–1817 Emerson attended Boston Latin School, enrolling when he was nine years old at a time when war with Britain was at hand. The Latin School was the oldest public school in the nation, and known for its rigorous curriculum for boys who usually entered Harvard. Emerson followed the same path when he enrolled at Harvard in 1817 atthe age of fourteen— not unusually young for the time. He had received a small scholarship from the First Church in Boston, but he was still very poor. Emerson made his way through Harvard by ushering, waiting tables, tutoring, winning elocution prizes, and serving as the president’s errand boy. During school vacations, he taught at his Uncle Samuel Ripley’s school in Waltham, Massachusetts.

At Harvard, Emerson began his lifelong practice of keeping a journal. He regarded them as his “savings bank,” where he could express and examine ideas without public exposure. He also wrote poetry in hisjournals, and illustrated many of his pages professing his early “hunger and thirst to be a painter.” His writing, however, was recognized when he receivedBowdoin Prizes for his 1820 Dissertation on the Character of Socrates and his 1821 Dissertation on the Present State of Ethical Philosophy . He also decided to drop the name “Ralph” and call himself “Waldo.”

Waldo Emerson graduated from Harvard in 1821 at eighteen years of age and began teaching in the school for girls his brother, William, ran out of the family home on Boston’s Federal Street. He continued to write, and to read voraciously the work of European, especially Scottish, philosophers.

“The advantage in education is always with those children who slip up into life without being objects of notice.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

Collections

Denominational Administration

Search by Category

Search by tag.

- Book Reviews

- Cambridge & Harvard

- Congregational Polity

- Liturgy & Holidays

- Lectures & Sermons

- Poetry, Prayers & Visual Arts

- Religion & Culture

- Social Reform

- Theology & Philosophy

- Women & Religion

- About Harvard Square Library

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

The American Scholar

Ralph waldo emerson.

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

| Summary & Analysis |

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

- December 17, 2004

- Complete Works of RWE , X - Lectures and Biographical Sketches

With the key of the secret he marches faster From strength to strength, and for night brings day, While classes or tribes too weak to master The flowing conditions of life, give way. EDUCATION. A NEW degree of intellectual power seems cheap at any price. The use of the world is that man may learn its laws. And the human race have wisely signified their sense of this, by calling wealth, means, – Man being the end. Language is always wise.

Therefore I praise New England because it is the country in the world where is the freest expenditure for education. We have already taken, at the planting of the Colonies, (for aught I know for the first time in the world,) the initial step, which for its importance might have been resisted as the most radical of revolutions, thus deciding at the start the destiny of this country,- this, namely, that the poor man, whom the law does not allow to take an ear of corn when starving, nor a pair of shoes for his freezing feet, is allowed to put his hand into the pocket of the rich, and say, You shall educate me, not as you will, but as I will : not alone in the elements, but, by further provision, in the languages, in sciences, in the useful and in elegant arts. The child shall be taken up by the State, and taught, at the public cost, the rudiments of knowledge, and, at last, the ripest results of art and science.

Humanly speaking, the school, the college, society, make the difference between men. All the fairy tales of Aladdin or the invisible Gyges or the talisman that opens kings' palaces or the en-chanted halls under-ground or in the sea, are only fictions to indicate the one miracle of intellectual enlargement. When a man stupid becomes a man inspired, when one and the same man passes out of the torpid into the perceiving state, leaves the din of trifles, the stupor of the senses, to enter into the quasi-omniscience of high thought, – up and down, around, all limits disappear. No horizon shuts down. He sees things in their causes, all facts in their connection.

One of the problems of history is the beginning of civilization. The animals that accompany and serve man make no progress as races. Those called domestic are capable of learning of man a few tricks of utility or amusement, but they cannot communicate the skill to their race. Each individual must be taught anew. The trained dog cannot train another dog. And Man himself in many races retains almost the unteachableness of the beast. For a thousand years the islands and forests of a great part of the world have been filledwith savages who made no steps of advance in art or skill beyond the necessity of being fed and warmed. Certain nations with a better brain and usually in more temperate climates, have made such progress as to compare with these as these compare with the bear and the wolf.

Victory over things is the office of man. Of course, until it is accomplished, it is the war and insult of things over him. His continual tendency, his great danger, is to overlook the fact that the world is only his teacher, and the nature of sun and moon, plant and animal only means of arousing his interior activity. Enamored of their beauty, comforted by their convenience, he seeks them as ends, and fast loses sight of the fact that they have worse than no values, that they become noxious, when he becomes their slave.

This apparatus of wants and faculties, this craving body, whose organs ask all the elements and all the functions of Nature for their satisfaction, educate the wondrous creature which they satisfy with light, with heat, with water, with wood, with bread, with wool. The necessities imposed by this most irritable and all-related texture have taught Man hunting, pasturage, agriculture, commerce, weaving, joining, masonry, geometry, astronomy. Here is a world pierced and belted with natural laws, and fenced and planted with civil partitions and properties, which all put new restraints on the young inhabitant. He too must come into this magic circle of relations, and know health and sickness, the fear of injury, the desire of external good, the charm of riches, the charm of power. The house-hold is a school of power. There, within the door, learn the tragi-comedy of human life. Here is the sincere thing, the wondrous composition for which day and night go round. In that routine are the sacred relations, the passions that bind and sever. Here is poverty and all the wisdom its hated necessities can teach, here labor drudges, here affections glow, here the secrets of character are told, the guards of man, the guards of woman, the compensations which, like angels of justice, pay every debt the opium of custom, whereof all drink and many go mad. Here is Economy, and Glee, and Hospitality, and Ceremony, and Frankness, and Calamity, and Death, and Hope.

Every one has a trust of power, – every man, every boy a jurisdiction, whether it be over a cow or a rood of a potato-field, or a fleet of ships, or the laws of a state. And what activity the desire of power inspires! What toils it sustains! How it sharpens the perceptions and stores the memory with facts. Thus a man may well spend many years of life in trade. It is a constant teaching of the laws of matter and of mind. No dollar of property can be created without some direct communication with nature, and of course some acquisition of knowledge and practical force. It is it constant contest with the active faculties of men, a study of the issues of one and another course of action, an accumulation of power, and, if the higher faculties of the individual be from time to time quickened, he will gain wisdom and virtue from his business.

As every wind draws music out of the Aeolian harp, so doth every object in Nature draw music out of his mind. Is it not true that every landscape I behold, every friend I meet, every act I perform, every pain I suffer, leaves me a different being from that they found me ? That poverty, love, authority, anger, sickness, sorrow, success, all work: actively upon our being and unlock for us the concealed faculties of the mind ? Whatever private or petty ends are frustrated, this end is always answered. Whatever the man does, or whatever befalls him, opens another chamber in his soul, – that is, he has got a new feeling, a new thought, a new organ. Do we not see how amazingly for this end man is fitted to the world ?

What leads him to science? Why does he track in the midnight heaven a pure spark, a luminous patch wandering from age to age, but because he acquires thereby a majestic sense of power ; learning that in his own constitution he can set the shining maze in order, and finding and carrying their law in his mind, can, as *it were, see his simple idea realized up yonder in giddy distances and frightful periods of duration. If Newton come and first of men perceive that not alone certain bodies fall to the ground at a certain rate, but that all bodies in the Universe, the universe of bodies, fall always, and at one rate ; that every atom in nature draws to every other atom, – he extends the power of his mind not only over every cubic atom of his native planet, but he reports the condition of millions of worlds which his eye never saw. And what is the charm which every ore, every new plant, every new fact touching winds, clouds, ocean currents, the secrets of chemical composition and decomposition possess for Humboldt ? What but that much revolving of similar facts in his mind has shown him that always the mind contains in its transparent chambers the means of classifying the most refractory phenomena, of depriving them of all casual and chaotic aspect, and subordinating them to a bright reason of its own, and so giving to man a sort of property, – yea, the very highest property in every district and particle of the globe.

By the permanence of Nature, minds are trained alike, and made intelligible to each other. In our condition are the roots of language and communication, and these instructions we never exhaust.

In some sort the end of life is that the man should take up the universe into himself, or out of that quarry leave nothing unrepresented. Yonder mountain must migrate into his mind. Yonder magnificent astronomy he is at last to import, fetching away moon, and planet, solstice, period, comet and binal star, by comprehending their relation and law. Instead of the timid stripling he was, he is to be the stalwart Archimedes, Pythagoras, Columbus, Newton, of the physic, metaphysic and ethics of the design of the world.

For truly the population of the globe has its origin in the aims which their existence is to serve; and so with every portion of them. The truth takes flesh in forms that can express it ; and thus in history an idea always overhangs, like the moon, and rules the tide which rises simultaneously in all the souls of a generation.

Whilst thus the world exists for the mind ; whilst thus the man is ever invited inward into shining realms of knowledge and power by the shows of the world, which interpret to him the infinitude of his own consciousness, – it becomes the office of a just education to awaken him to the knowledge of this fact.

We learn nothing rightly until we learn the symbolical character of life. Day creeps after day, each full of facts, dull, strange, despised things, that we cannot enough despise, -call heavy, prosaic, and desert. The time we seek to kill: the attention it is elegant to divert from things around us. And presently the aroused intellect find, gold and gems in one of these scorned facts, – then finds that the day of facts is a rock of diamonds ; that a fact is an Epiphany of God.

We have our theory of life, our religion, our philosophy; and the event of each moment, the shower, the steamboat disaster, the passing of a beautiful face, the apoplexy of our neighbor, are all tests to try our theory, the approximate result we call truth, and reveal its defects. If I have renounced the search of truth, if I have come into the port of some pretending dogmatism, solve new church or old church, some Schelling or Cousin, I have died to all use of these new events that are born out of prolific time into multitude of life every hour. I am as a bankrupt to whom brilliant opportunities offer in vain. He has just foreclosed his freedom, tied his hands, locked himself up and given the key to another to keep.

When I see the doors by which God enters into the mind ; that there is no sot or fop, ruffian or pedant into whom thoughts do not enter by passages which the individual never left open, I can expect any revolution in character. I have hope," said the great Leibnitz, " that society may be reformed, when I see how much education may be reformed."

It is ominous, a presumption of crime, that this word Education has so cold, so hopeless a sound. A treatise on education, a convention for education, a lecture, a system, affects us with slight paralysis and a certain yawning of the jaws. We are not encouraged when the law tonches it with its, fingers. Education should be as broad as man. Whatever elements are in him that should foster and demonstrate. If he be dexterous, his tuition should make it appear; if he be capable of dividing men by the trenchant sword of his thought, education should unsheathe and sharpen it ; if he is one to cement society by his all-reconciling affinities, oh! hasten their action , If he is jovial, if he is mercurial, if he is great-hearted, a cunning artificer, a strong commander, a potent ally, ingenious, useful, elegant, witty, prophet, diviner, – society has need of all these. The imagination must be addressed. Why always coast on the surface and never open the interior of nature, not by science, which is surface still, but by poetry ? Is not the Vast an element of the mind ? Yet what teaching, what book of this day appeals to the Vast ?

Our culture has truckled to the times, – to the senses. It is not manworthy. If the vast and the spiritual are omitted, so are the practical and the moral. It does not make us brave or free. We teach boys to be such men as we are. We do not teach them to aspire to be all they can. We do not give them a training as if we believed in their noble nature. We scarce educate their bodies. We do not train the eye and the hand. We exercise their understandings to the apprehension and comparison of some facts, to a skill in numbers, in words ; we aim to make accountants, attorneys, engineers ; but not to make able, earnest, great-hearted men. The great object of Education should be commensurate with the object of life. It should be a moral one ; to teach self-trust : to inspire the youthful man with an interest in himself ; with a curiosity touching his own nature ; to acquaint him with the resources of his mind, and to teach him that there is all his strength, and to inflame him with a piety towards the Grand Mind in which he lives. Thus would education conspire with the Divine Providence. A man is a little thing whilst he works by and for himself, but, when he gives voice to the rules of love and justice, is godlike, his word is current in all countries ; and all men, though his enemies, are made his friends and obey it as their own.

In affirming that the moral nature of man is the predominant element and should therefore be mainly consulted in the arrangements of a school, I am very far from wishing that it should swallow up all the other instincts and faculties of man. It should be enthroned in his mind, but if it monopolize the man he is not yet sound, he does not yet know his wealth. He is in danger of becoming merely devout, and wearisome through the monotony of his thought. It is not less necessary that the intellectual and the active faculties should be nourished and matured. Let us apply to this subject the light of the same torch by which we have looked at all the phenomena of the time ; the infinitude, namely, of every man. Everything teaches that.

One fact constitutes all my satisfaction, inspires all my trust, viz., this perpetual youth, which, as long as there is any good in us, we cannot get rid of. It is very certain that the coining age and the departing age seldom understand each other. The old man thinks the young man has no distinct purpose, for he could never get anything intelligible and earnest out of him. Perhaps the young man does not think it worth his while to explain himself to so hard and inapprehensive a confessor. Let him be led up with a long-sighted forbearance, and let not the sallies of his petulance or folly be checked with disgust or indignation or despair.

I call our system a system of despair, and I find all the correction, all the revolution that is needed and that the best spirits of this age promise, in one word, in Hope. Nature, when she sends a new mind into the world, fills it beforehand with a desire for that which she wishes it to know and do. Let us wait and see what is this new creation, of what new organ the great Spirit had need when it incarnated this new Will. A new Adam in the garden, he is to name all the beasts in the field, all the gods in the sky. And jealous provision seems to have been made in his constitution that you shall not invade and contaminate him with the worn weeds of your language and opinions. The charm of life is this variety of genius, these contrasts and flavors by which Heaven has modulated the identity of truth, and there is a perpetual hankering to violate this individuality, to warp his ways of thinking and behavior to resemble or reflect your thinking and behavior. A low self-love in the parent desires that his child should repeat his character and fortune ; an expectation which the child, if justice is done him, will nobly disappoint. By working on the theory that this resemblance exists, we shall do what in us lies to defeat his proper promise and produce the ordinary and mediocre. I suffer whenever I see that common sight of a parent or senior imposing his opinion and way of thinking and being on a young soul to which they are totally unfit. Cannot we let people be themselves. and enjoy life in their own way ? You are trying to make that man another you. One's enough. Or we sacrifice the genius of the pupil, the unknown possibilities of his nature, to a neat and safe uniformity, as the Turks whitewash the costly mosaics of ancient art which the Greeks left on their temple walls. Rather let us have men whose man-hood is only the continuation of their boyhood, natural characters still; such are able and fertile for heroic action : and not that sad spectacle with which we are too familiar, educated eyes in uneducated bodies.

I like boys, the masters of the playground and of the street, – boys, who have the same liberal ticket of admission to all shops, factories, armories, town-meetings. caucuses, mobs, target-shootings, as flies have ; quite unsuspected, coming in as naturally as the janitor, – known to have no money in their pockets, and themselves not suspecting the value of this poverty : putting nobody on his guard, but seeing the inside of the show, – hearing all the asides. There are no secrets from them, they know everything that befalls in the fire-company, the merits of every engine and of every man at the brakes, how to work it, and are swift to try their hand at every part ; so too the merits of every locomotive on the rails, and will coax the engineer to let them ride with him and pull the handles when it goes to the engine-house. They are there only for fun, and not knowing that they are at school, in the court-house, or the cattle-show, quite as much and more than they were, an hour ago, in the arithmetic class.

They know truth from counterfeit as quick as the chemist does. They detect weakness in your eye and behavior a week before you open your mouth, and have given you the benefit of their opinion quick as a wink. They make no mistakes, have no pedantry, but entire belief on experience. Their elections at base – ball or cricket are founded on merit, and are right. They don't pass for swimmers until they can swim, nor for stroke-oar until they can row: and I desire to be saved from their contempt. If I can pass with them, I can manage well enough with their fathers.

Everybody delights in the energy with which boys deal and talk with each other ; the mixture of fun and earnest, reproach and coaxing, love and wrath, with which the game is played ; – the good-natured yet defiant independence of a leading boy's behavior in the school-yard. How we envy in later life the happy youths to whom their boisterous games and rough exercise furnish the precise element which frames and sets off their school and college tasks, and teaches them, when least they think it, the use and meaning of these. In their fun and extreme freak they hit on the topmost sense of Horace. The young giant, brown from his hunting-tramp, tells his story well, interlarded with lucky allusions to Homer, to Virgil, to college-songs, to Walter Scott ; and Jove and Achilles, partridge and trout, opera and binomial theorem, Caesar in Gaul, Sherman in Savannah, and hazing in Holworthy, dance through the narrative in merry confusion, yet the logic is good. If he can turn his books to such picturesque account in his fishing and hunting, it is easy to see how his reading and experience, as he has more of both, will interpenetrate each other. And every one desires that this pure vigor of action and wealth of narrative, cheered with so much humor and street rhetoric, should be carried into the habit of the young man, purged of its uproar and rudeness, but with all its vivacity entire. His hunting and campings-out have given him an indispensable base : I wish to add a taste for good company through his impatience of bad. That stormy genius of his needs a little direction to games, charades, verses of society, song, and a correspondence year by year with his wisest and best friends. Friendship is an order of nobility ; from its revelations we come more worthily into nature. Society he must have or he is poor indeed ; he gladly enters a school which forbids conceit, affectation, emphasis and dulness, and requires of each only the flower of his nature and experience ; requires good-will, beauty, wit, and select information ; teaches by practice the law of conversation, namely, to hear as well as to speak.

Meantime, if circumstances do not permit the high social advantages, solitude has also its lessons. The obscure youth learns there the practice instead of the literature of his virtues ; and, because of the disturbing effect of passion and sense, which by a multitude of trifles impede the mind's eye from the quiet search of that fine horizon-line which truth keeps, – the way to knowledge and power has ever been an escape from too much engagement with affairs and possessions; a way, not through plenty and superfluity, but by denial and renunciation, into solitude and privation ; and, the more is taken away, the more real and inevitable wealth of being is made known to us. The solitary knows the essence of the thought, the scholar in society only its fair face. There is no want of example of great men, great benefactors, who have been monks and hermits in habit. The bias of mind is sometimes irresistible in that direction. The man is, as it were, born deaf and dumb, and dedicated to a narrow and lonely life. Let him study the art of solitude, yield as gracefully as he can to his destiny. Why can-not he get the good of his doom. and if it is from eternity a settled fact that he and society shall be nothing to each other, why need he blush so, and , make wry faces to keep up a freshman's seat in the fine world ? Heaven often protects valuable souls charged with great secrets, great ideas, by long shutting them up with their own thoughts. And the most genial and amiable of men must alternate society with solitude, and learn its severe lessons.

There comes the period of the imagination to each, a later youth ; the power of beauty, the power of books, of poetry. Culture makes his books realities to him, their characters more brilliant, more effective on his mind, than his actual mates. Do not spare to put novel:; into the hands of young people as an occasional holiday and experiment; but, above all, good poetry in all kinds, epic, tragedy, lyric. If we can touch the imagination, we serve them, they will never forget it. Let him read "Tom Brown at Rugby," read " Tom Brown at Oxford,"- better yet, read " Hodson's Life "-Hodson who took prisoner the king of Delhi. They teach the same truth, – a trust, against all appearances, against all privations, in your own worth, and not in tricks, plotting, or patronage.

I believe that our own experience instructs us that the secret of Education lies in respecting the pupil. It is not for you to choose what he shall know, what he shall do. It is chosen and foreordained, and he only holds the key to his own secret. By your tampering and thwarting and too much governing he may be hindered from his end and kept out of his own. Respect the child. Wait and see the new product of Nature. Nature loves analogies, but not repetitions. Respect the child. Be not too much his parent. Trespass not on his solitude.

But I hear the outcry which replies to this suggestion : – Would you verily throw up the reins of public and private discipline ; would you leave the young child to the mad career of his own passions and whimsies, and call this anarchy a respect for the child's nature ? I answer, – Respect the child, respect him to the end, but also respect yourself. Be the companion of his thought, the friend of his friendship, the lover of his virtue, – but no kinsman of his sin. Let him find you so true to yourself that you are the irreconcilable hater of his vice and the imperturbable slighter of his trifling.

The two points in a boy's training are, to keep his naturel and train off all but that : – to keep his naturel , but stop off his uproar, fooling and horse-play ; – keep his nature and arm it with knowledge in the very direction in which it points. Here are the two capital facts, Genius and Drill. The first is the inspiration in the well-born healthy child, the new perception he has of nature. Somewhat he sees in forms or hears in music or apprehends in mathematics, or believes practicable in mechanics or possible in political society, which no one else sees or hears or believes. This is the perpetual romance of new life, the invasion of God into the old dead world, when he sends into quiet houses a young soul with a thought which is not met, looking for something which is not there, but which ought to be there : the thought is dim but it is sure, and he casts about restless for means and masters to verify it ; he makes wild attempts to ex-plain himself and invoke the aid and consent of the bystanders. Baffled for want of language and methods to convey his meaning, not yet clear to himself, he conceives that though not in this house or town, yet in some other house or town is the wise master who can put him in possession of the rules and instruments to execute his will. Happy this child with a bias, with a thought which entrances him, leads him, now into deserts now into cities, the fool of an idea. Let him follow it in good and in evil report, in good or bad company ; it will justify itself ; it will lead him at last into the illustrious society of the lovers of truth.

In London, in a private company, I became acquainted with a gentleman, Sir Charles Fellowes, who, being at Xanthus, in the Aegean Sea, had seen a Turk point with his staff to some carved work on the corner of a stone almost buried in the soil. Fellowes scraped away the dirt, was struck with the beauty of the sculptured ornaments, and, looking about him, observed more blocks and fragments like this. He returned to the spot, procured laborers and uncovered many blocks. He went back to England, bought a Greek grammar and learned the language ; he read history and studied ancient art to explain his stones ; he interested Gibson the sculptor ; he invoked the assistance of the English Government ; he called in the succor of Sir Humphry Davy to analyze the pigments ; of experts in coins, of scholars and connoisseurs ; and at last in his third visit brought home to England such statues and marble reliefs and such careful plans that he was able to reconstruct, in the British Museum where it now stands, the perfect model of the Ionic trophy-monument, fifty years older than the Parthenon of Athens, and which had been destroyed by earthquakes, then by iconoclast Christians, then by savage Turks. But mark that in the task he had achieved an excellent education, and become associated with distinguished scholars whom he had interested in his pursuit ; in short, had formed a college for himself ; the enthusiast had found the master, the masters, whom he sought. Always genius seeks genius, desires nothing so much as to be a pupil and to find those who can lend it aid to perfect itself.

Nor are the two elements, enthusiasm and drill, incompatible. Accuracy is essential to beauty. The very definition of the intellect is Aristotle's : "that by which we know terms or boundaries." Give a boy accurate perceptions. Teach him the difference between the similar and the same. Make him call things by their right names. Pardon in him no blunder. Then he will give you solid satisfaction as long as he lives. It is better to teach the child arithmetic and Latin grammar than rhetoric or moral philosophy, because they require exactitude of performance ; it is made certain that the lesson is mastered, and that power of performance is worth more than the knowledge. He can learn anything which is important to him now that the power to learn is secured: as mechanics say, when one has learned the use of tools, it is easy to work at a new craft.

Letter by letter, syllable by syllable, the child learns to read, and in good time can convey to all the domestic circle the sense of Shakspeare. By many steps each just as short, the stammering boy and the hesitating collegian, in the school debate, in college clubs, in mock court, comes at last to full, secure, triumphant unfolding of his thought in the popular assembly, with a fullness of power that makes all the steps forgotten.

But this function of opening and feeding the human mind is not to be fulfilled by any mechanical or military method ; is not to be trusted to any skill less large than Nature itself. You must not neglect the form, but you must secure the essentials. It is curious how perverse and intermeddling we are, and what vast pains and cost we incur to do wrong. Whilst we all know in our own experience and apply natural methods in our own business, – in education our common sense fails us, and we are continually trying costly machinery against nature, in patent schools and academies and in great colleges and universities.

The natural method forever confutes our experiments, and we must still come back to it. The whole theory of the school is on the nurse's or mother's knee. The child is as hot to learn as the mother is to impart. There is mutual delight. The joy of our childhood in hearing beautiful stories from some skilful aunt who loves to tell them, must be repeated in youth. The boy wishes to learn to skate, to coast, to catch a fish in the brook, to hit a mark with a snowball or a stone ; and a boy a little older is just as well pleased to teach him these sciences. Not less delightful is the mutual pleasure of teaching and learning the secret of algebra, or of chemistry, or of good reading and good recitation of poetry or of prose, or of chosen facts in history or in biography.

Nature provided for the communication of thought, by planting with it in the receiving mind a fury to impart it. It is so in every art, in every science. One burns to tell the new fact, the other burns to hear it. See how far a young doctor will ride or walk to witness a new surgical operation. I have seen a carriage-maker's shop emptied of all its workmen into the street, to scrutinize a new pattern from New York. So in literature, the young man who has taste for poetry, for fine images, for noble thoughts, is insatiable for this nourishment, and forgets all the world for the more learned friend, – who finds equal joy in dealing out his treasures.

Happy the natural college thus self-instituted around every natural teacher : the young men of Athens around Socrates ; of Alexandria around Plotinus ; of Paris around Abelard ; of Germany around Fichte. Niebuhr, or Goethe : in short the natural sphere of every leading mind. But the moment this is organized, difficulties begin. The college was to be the nurse and home of genius ; but, though every young man is born with some determination in his nature, and is a potential genius; is at last to be one ; it is, in the most, obstructed and delayed, and, whatever they may hereafter be, their senses are now opened in advance of their minds. They are more sensual than intellectual. Appetite and indolence they have, but no enthusiasm. These come in numbers to the college : few geniuses : and the teaching comes to be arranged for these many, and not for those few. Hence the instruction seems to require skilful tutors, of accurate and systematic mind, rather than ardent and inventive masters. Besides, the youth of genius are eccentric, won't drill, are irritable, uncertain, explosive, solitary, not men of the world, not good for every-day association. You have to work for large classes instead of individuals; yon must lower your flag and reef your sails to wait for the dull sailors; you grow departmental, routinary, military almost with your discipline and college police. But what doth such a school to form a great and heroic character? What abiding Hope can it inspire? What Reformer will it nurse? What poet will it breed to sing to the human race? What discoverer of Nature's laws will it prompt to enrich us by disclosing in the mind the statute which all matter must obey ? What fiery soul will it send out to warm a nation with his charity ? What tranquil mind will it have fortified to walk with meekness in private and obscure duties, to wait and to suffer? Is it not manifest that our academic institutions should have a wider scope : that they should not be timid and keep the ruts of the last generation, but that wise men thinking for themselves and heartily seeking the good of mankind, and counting the cost of innovation, should dare to arouse the young to a just and heroic life; that the moral nature should be addressed in the school-room, and children should be treated as the high-born candidates of truth and virtue ?

So to regard the young child, the young man, requires, no doubt, rare patience : a patience that nothing but faith in the remedial forces of the soul can give. You see his sensualism ; you see his want of those tastes and perceptions which make the power and safety of your character. Very likely. But he has something else. If he has his own vice, he has its correlative virtue. Every mind should be allowed to make its own statement in action, and its balance will appear. In these judgments one needs that foresight which was attributed to an eminent reformer, of whom it was said his patience could see in the bud of the aloe the blossom at the end of a hundred years." Alas for the cripple Practice when it seeks to come up with the bird Theory, which flies before it. Try your design on the best school. The scholars are of all ages and temperaments and capacities. It is difficult to class them, some are too young, some are slow, some perverse. Each requires so much consideration, that the morning hope of the teacher, of a day of love and progress, is often closed at evening by despair. Each single case, the more it is considered, shows more to be done; and the strict conditions of the hours, on one side, and the number of tasks, on the other. Whatever becomes of our method, the conditions stand fast, – six hours, and thirty, fifty, or a hundred and fifty pupils. Something must be done, and done speedily, and in this distress the wisest are tempted to adopt violent means, to proclaim martial law, corporal punishment, mechanical arrangement, bribes, spies, wrath, main strength and ignorance, in lieu of that wise genial providential influence they had hoped, and yet hope at some future day to adopt. Of course the devotion to details reacts injuriously on the teacher. He cannot indulge his genius, he cannot delight in personal relations with young friends, when his eye is always on the clock, and twenty classes are to be dealt with before the day is done. Besides, how can he please himself with genius, and foster modest virtue ? A sure proportion of rogue and dunce finds its way into every school and requires a cruel share of time, and the gentle teacher, who wished to be a Providence to youth, is grown a martinet, sore with suspicions ; knows as much vice as the judge of a police court, and his love of learning is lost in the routine of grammars and books of elements.

A rule is so easy that it does not need a man to apply it ; an automaton, a machine, can be made to keep a school so. It facilitates labor and thought so much that there is always the temptation in large schools to omit the endless task of meeting the wants of each single mind, and to govern by steam. But it is at frightful cost. Our modes of Education aim to expedite, to save labor ; to do for masses what cannot be done for masses, what must be done reverently, one by one : say rather, the whole world is needed for the tuition of each pupil. The advantages of this system of emulation and display are so prompt and obvious, it is such a time-saver, it is so energetic on slow and on bad natures, and is of so easy application, needing no sage or poet, but any tutor or schoolmaster in his first term can apply it, – that it is not strange that this calomel of culture should be a popular medicine. On the other hand, total abstinence from this drug. and the adoption of simple discipline and the following of nature, involves at once immense claims on the time, the thoughts, on the life of the teacher. It requires time, use, insight, event, all the great lessons and assistances of God ; and only to think of using it implies character and profoundness ; to enter on this course of discipline is to be good and great. It is precisely analogous to the difference between the use of corporal punishment and the methods of love. It is so easy to bestow on a bad boy a blow, overpower him, and get obedience without words, that in this world of hurry and distraction, who can wait for the returns of reason and the conquest of self ; in the uncertainty too whether that will ever come? And yet the familiar observation of the universal compensations might suggest the fear that so summary a stop of a bad humor was more jeopardous than its continuance.

Now the correction of this quack practice is to import into Education the wisdom of life. Leave this military hurry and adopt the pace of Nature. Her secret is patience. Do you know how the naturalist learns all the secrets of the forest, of pants, of birds, of beasts, of reptiles, of fishes, of the rivers and the sea ? When he goes into the woods the birds fly before him and he finds none ; when he goes to the river bank, the fish and the reptile swim away and leave him alone. His secret is patience ; he sits down, and sits still ; he is a statue ; he is a log. These creatures have no value for their time, and he must put as low a rate on his. By dint of obstinate sitting still, reptile, fish, bird and beast, which all wish to return to their haunts, begin to return. He sits still ; if they approach, he remains passive as the stone he sits upon. They lose their fear. They have curiosity too about him. By and by the curiosity masters the fear, and they come swimming, creeping and flying towards him ; and as he is still immovable, they not only resume their haunts and their ners, show themselves trim, but also volunteer some towards fellowship and good a biped who behaves so civilly not baffle the impatience and by your tranquillity? Can you not wait for him, as Nature and Providence do ? Can you not keep for his mind and ways, for his secret, the same curiosity you give to the squirrel, snake, rabbit, and the sheldrake and the deer? He has a secret ; wonderful methods in him ; he is, – every child, – a new style of man ; give him time and opportunity. Talk of Columbus and Newton ! I tell you the child just born in yonder hovel is the be-ginning of a revolution as great as theirs. But you must have the believing and prophetic eye. Have the self-command you wish to inspire. Your teaching and discipline must have the reserve and taciturnity of Nature. Teach them to hold their tongues by holding your own. Say little ; do not snarl ; do not chide ; but govern by the eye. See what they need, and that the right thing is done.

I confess myself utterly at a loss in suggesting particular reforms in our ways of teaching. No discretion that can be lodged with a school-committee, with the overseers or visitors of an academy, of a college, can at all avail to reach these difficulties and perplexities, but they solve themselves when we leave institutions and address individuals. The will, the male power, organizes, imposes its own thought and wish on others, and makes that military eye which controls boys as it controls men ; admirable in its results, a fortune to him who has it, and only dangerous when it leads the workman to overvalue and overuse it and precludes him from finer means. Sympathy, the female force, – which they must use who have not the first, – deficient in instant control and the breaking down of resistance, is more subtle and lasting and creative. I advise teachers to cherish mother-wit. I assume that you will keep the grammar, reading, writing and arithmetic in order ; 't is easy and of course you will. But smuggle in a little contraband wit, fancy, imagination, thought. If you have a taste which you have suppressed because it is not shared by those about you, tell them that. Set this law up, whatever becomes of the rules of the school : they must not whisper, much less talk ; but if one of the young people says a wise thing, greet it, and let all the children clap their hands. They shall have no book but school-books in the room ; but if one has brought in a Plutarch or Shakspeare or Don Quixote or Goldsmith or any other good book, and understands what he reads, put him at once at the head of the class. Nobody shall be disorderly, or leave his desk without permission, but if a boy runs from his bench, or a girl, because the fire falls, or to check some injury that a little dastard is inflicting behind his desk on some helpless sufferer, take away the medal from the head of the class and give it on the instant to the brave rescuer. If a child happens to show that he knows any fact about astronomy, or plants birds, or rocks, or history, that interests him and you, hush all the classes and encourage him to tell it so that all may hear. Then you have made your school-room like the world. Of course you will insist on modesty in the children, and respect to their teachers, but if the boy stops you in your speech, cries out that you are wrong and sets you right, hug him !

To whatsoever upright mind, to whatsoever beating heart I speak, to you it is committed to educate men. By simple living, by an illimitable soul, you inspire, you correct, you instruct, you raise, you embellish all. By your own act you teach the beholder how to do the practicable. Ac-cording to the depth from which you draw your life, such is the depth not only of your strenuous effort, but of your manners and presence.

The beautiful nature of the world has here blended your happiness with your power. Work straight on in absolute duty, and you lend an arm and an encouragement to all the youth of the universe. Consent yourself to be an organ of your highest thought, and lo ! suddenly you put all men in your debt, and are the fountain of an energy that goes pulsing on with waves of benefit to the borders of society, to the circumference of things.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Photo from Amos Bronson Alcott 1882.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

An American essayist, poet, and popular philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) began his career as a Unitarian minister in Boston, but achieved worldwide fame as a lecturer and the author of such essays as “Self-Reliance,” “History,” “The Over-Soul,” and “Fate.” Drawing on English and German Romanticism, Neoplatonism, Kantianism, and Hinduism, Emerson developed a metaphysics of process, an epistemology of moods, and an “existentialist” ethics of self-improvement. He influenced generations of Americans, from his friend Henry David Thoreau to John Dewey, and in Europe, Friedrich Nietzsche, who takes up such Emersonian themes as power, fate, the uses of poetry and history, and the critique of Christianity.

1. Chronology of Emerson’s Life

2.1 education, 2.2 process, 2.3 morality, 2.4 christianity, 2.6 unity and moods, 3. emerson on slavery and race, 4.1 consistency, 4.2 early and late emerson, 4.3 sources and influence, works by emerson, selected writings on emerson, other internet resources, related entries, 2. major themes in emerson’s philosophy.

In “The American Scholar,” delivered as the Phi Beta Kappa Address in 1837, Emerson maintains that the scholar is educated by nature, books, and action. Nature is the first in time (since it is always there) and the first in importance of the three. Nature’s variety conceals underlying laws that are at the same time laws of the human mind: “the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim” (CW1: 55). Books, the second component of the scholar’s education, offer us the influence of the past. Yet much of what passes for education is mere idolization of books — transferring the “sacredness which applies to the act of creation…to the record.” The proper relation to books is not that of the “bookworm” or “bibliomaniac,” but that of the “creative” reader (CW1: 58) who uses books as a stimulus to attain “his own sight of principles.” Used well, books “inspire…the active soul” (CW1: 56). Great books are mere records of such inspiration, and their value derives only, Emerson holds, from their role in inspiring or recording such states of the soul. The “end” Emerson finds in nature is not a vast collection of books, but, as he puts it in “The Poet,” “the production of new individuals,…or the passage of the soul into higher forms” (CW3:14).

The third component of the scholar’s education is action. Without it, thought “can never ripen into truth” (CW1: 59). Action is the process whereby what is not fully formed passes into expressive consciousness. Life is the scholar’s “dictionary” (CW1: 60), the source for what she has to say: “Only so much do I know as I have lived” (CW1:59). The true scholar speaks from experience, not in imitation of others; her words, as Emerson puts it, are “are loaded with life…” (CW1: 59). The scholar’s education in original experience and self-expression is appropriate, according to Emerson, not only for a small class of people, but for everyone. Its goal is the creation of a democratic nation. Only when we learn to “walk on our own feet” and to “speak our own minds,” he holds, will a nation “for the first time exist” (CW1: 70).

Emerson returned to the topic of education late in his career in “Education,” an address he gave in various versions at graduation exercises in the 1860s. Self-reliance appears in the essay in his discussion of respect. The “secret of Education,” he states, “lies in respecting the pupil.” It is not for the teacher to choose what the pupil will know and do, but for the pupil to discover “his own secret.” The teacher must therefore “wait and see the new product of Nature” (E: 143), guiding and disciplining when appropriate-not with the aim of encouraging repetition or imitation, but with that of finding the new power that is each child’s gift to the world. The aim of education is to “keep” the child’s “nature and arm it with knowledge in the very direction in which it points” (E: 144). This aim is sacrificed in mass education, Emerson warns. Instead of educating “masses,” we must educate “reverently, one by one,” with the attitude that “the whole world is needed for the tuition of each pupil” (E: 154).

Emerson is in many ways a process philosopher, for whom the universe is fundamentally in flux and “permanence is but a word of degrees” (CW 2: 179). Even as he talks of “Being,” Emerson represents it not as a stable “wall” but as a series of “interminable oceans” (CW3: 42). This metaphysical position has epistemological correlates: that there is no final explanation of any fact, and that each law will be incorporated in “some more general law presently to disclose itself” (CW2: 181). Process is the basis for the succession of moods Emerson describes in “Experience,” (CW3: 30), and for the emphasis on the present throughout his philosophy.

Some of Emerson’s most striking ideas about morality and truth follow from his process metaphysics: that no virtues are final or eternal, all being “initial,” (CW2: 187); that truth is a matter of glimpses, not steady views. We have a choice, Emerson writes in “Intellect,” “between truth and repose,” but we cannot have both (CW2: 202). Fresh truth, like the thoughts of genius, comes always as a surprise, as what Emerson calls “the newness” (CW3: 40). He therefore looks for a “certain brief experience, which surprise[s] me in the highway or in the market, in some place, at some time…” (CW1: 213). This is an experience that cannot be repeated by simply returning to a place or to an object such as a painting. A great disappointment of life, Emerson finds, is that one can only “see” certain pictures once, and that the stories and people who fill a day or an hour with pleasure and insight are not able to repeat the performance.

Emerson’s basic view of religion also coheres with his emphasis on process, for he holds that one finds God only in the present: “God is, not was” (CW1:89). In contrast, what Emerson calls “historical Christianity” (CW1: 82) proceeds “as if God were dead” (CW1: 84). Even history, which seems obviously about the past, has its true use, Emerson holds, as the servant of the present: “The student is to read history actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary” (CW2: 5).

Emerson’s views about morality are intertwined with his metaphysics of process, and with his perfectionism, his idea that life has the goal of passing into “higher forms” (CW3:14). The goal remains, but the forms of human life, including the virtues, are all “initial” (CW2: 187). The word “initial” suggests the verb “initiate,” and one interpretation of Emerson’s claim that “all virtues are initial” is that virtues initiate historically developing forms of life, such as those of the Roman nobility or the Confucian junxi . Emerson does have a sense of morality as developing historically, but in the context in “Circles” where his statement appears he presses a more radical and skeptical position: that our virtues often must be abandoned rather than developed. “The terror of reform,” he writes, “is the discovery that we must cast away our virtues, or what we have always esteemed such, into the same pit that has consumed our grosser vices” (CW2: 187). The qualifying phrase “or what we have always esteemed such” means that Emerson does not embrace an easy relativism, according to which what is taken to be a virtue at any time must actually be a virtue. Yet he does cast a pall of suspicion over all established modes of thinking and acting. The proper standpoint from which to survey the virtues is the ‘new moment‘ — what he elsewhere calls truth rather than repose (CW2:202) — in which what once seemed important may appear “trivial” or “vain” (CW2:189). From this perspective (or more properly the developing set of such perspectives) the virtues do not disappear, but they may be fundamentally altered and rearranged.

Although Emerson is thus in no position to set forth a system of morality, he nevertheless delineates throughout his work a set of virtues and heroes, and a corresponding set of vices and villains. In “Circles” the vices are “forms of old age,” and the hero the “receptive, aspiring” youth (CW2:189). In the “Divinity School Address,” the villain is the “spectral” preacher whose sermons offer no hint that he has ever lived. “Self Reliance” condemns virtues that are really “penances” (CW2: 31), and the philanthropy of abolitionists who display an idealized “love” for those far away, but are full of hatred for those close by (CW2: 30).

Conformity is the chief Emersonian vice, the opposite or “aversion” of the virtue of “self-reliance.” We conform when we pay unearned respect to clothing and other symbols of status, when we show “the foolish face of praise” or the “forced smile which we put on in company where we do not feel at ease in answer to conversation which does not interest us” (CW2: 32). Emerson criticizes our conformity even to our own past actions-when they no longer fit the needs or aspirations of the present. This is the context in which he states that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen, philosophers and divines” (CW2: 33). There is wise and there is foolish consistency, and it is foolish to be consistent if that interferes with the “main enterprise of the world for splendor, for extent,…the upbuilding of a man” (CW1: 65).

If Emerson criticizes much of human life, he nevertheless devotes most of his attention to the virtues. Chief among these is what he calls “self-reliance.” The phrase connotes originality and spontaneity, and is memorably represented in the image of a group of nonchalant boys, “sure of a dinner…who would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one…” The boys sit in judgment on the world and the people in it, offering a free, “irresponsible” condemnation of those they see as “silly” or “troublesome,” and praise for those they find “interesting” or “eloquent.” (CW2: 29). The figure of the boys illustrates Emerson’s characteristic combination of the romantic (in the glorification of children) and the classical (in the idea of a hierarchy in which the boys occupy the place of lords or nobles).

Although he develops a series of analyses and images of self-reliance, Emerson nevertheless destabilizes his own use of the concept. “To talk of reliance,” he writes, “is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is” (CW 2:40). ‘Self-reliance’ can be taken to mean that there is a self already formed on which we may rely. The “self” on which we are to “rely” is, in contrast, the original self that we are in the process of creating. Such a self, to use a phrase from Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo, “becomes what it is.”

For Emerson, the best human relationships require the confident and independent nature of the self-reliant. Emerson’s ideal society is a confrontation of powerful, independent “gods, talking from peak to peak all round Olympus.” There will be a proper distance between these gods, who, Emerson advises, “should meet each morning, as from foreign countries, and spending the day together should depart, as into foreign countries” (CW 3:81). Even “lovers,” he advises, “should guard their strangeness” (CW3: 82). Emerson portrays himself as preserving such distance in the cool confession with which he closes “Nominalist and Realist,” the last of the Essays, Second Series :

I talked yesterday with a pair of philosophers: I endeavored to show my good men that I liked everything by turns and nothing long…. Could they but once understand, that I loved to know that they existed, and heartily wished them Godspeed, yet, out of my poverty of life and thought, had no word or welcome for them when they came to see me, and could well consent to their living in Oregon, for any claim I felt on them, it would be a great satisfaction (CW 3:145).

The self-reliant person will “publish” her results, but she must first learn to detect that spark of originality or genius that is her particular gift to the world. It is not a gift that is available on demand, however, and a major task of life is to meld genius with its expression. “The man,” Emerson states “is only half himself, the other half is his expression” (CW 3:4). There are young people of genius, Emerson laments in “Experience,” who promise “a new world” but never deliver: they fail to find the focus for their genius “within the actual horizon of human life” (CW 3:31). Although Emerson emphasizes our independence and even distance from one another, then, the payoff for self-reliance is public and social. The scholar finds that the most private and secret of his thoughts turn out to be “the most acceptable, most public, and universally true” (CW1: 63). And the great “representative men” Emerson identifies are marked by their influence on the world. Their names-Plato, Moses, Jesus, Luther, Copernicus, even Napoleon-are “ploughed into the history of this world” (CW1: 80).

Although self-reliance is central, it is not the only Emersonian virtue. Emerson also praises a kind of trust, and the practice of a “wise skepticism.” There are times, he holds, when we must let go and trust to the nature of the universe: “As the traveler who has lost his way, throws his reins on his horse’s neck, and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world” (CW3:16). But the world of flux and conflicting evidence also requires a kind of epistemological and practical flexibility that Emerson calls “wise skepticism” (CW4: 89). His representative skeptic of this sort is Michel de Montaigne, who as portrayed in Representative Men is no unbeliever, but a man with a strong sense of self, rooted in the earth and common life, whose quest is for knowledge. He wants “a near view of the best game and the chief players; what is best in the planet; art and nature, places and events; but mainly men” (CW4: 91). Yet he knows that life is perilous and uncertain, “a storm of many elements,” the navigation through which requires a flexible ship, “fit to the form of man.” (CW4: 91).

The son of a Unitarian minister, Emerson attended Harvard Divinity School and was employed as a minister for almost three years. Yet he offers a deeply felt and deeply reaching critique of Christianity in the “Divinity School Address,” flowing from a line of argument he establishes in “The American Scholar.” If the one thing in the world of value is the active soul, then religious institutions, no less than educational institutions, must be judged by that standard. Emerson finds that contemporary Christianity deadens rather than activates the spirit. It is an “Eastern monarchy of a Christianity” in which Jesus, originally the “friend of man,” is made the enemy and oppressor of man. A Christianity true to the life and teachings of Jesus should inspire “the religious sentiment” — a joyous seeing that is more likely to be found in “the pastures,” or “a boat in the pond” than in a church. Although Emerson thinks it is a calamity for a nation to suffer the “loss of worship” (CW1: 89) he finds it strange that, given the “famine of our churches” (CW1: 85) anyone should attend them. He therefore calls on the Divinity School graduates to breathe new life into the old forms of their religion, to be friends and exemplars to their parishioners, and to remember “that all men have sublime thoughts; that all men value the few real hours of life; they love to be heard; they love to be caught up into the vision of principles” (CW1: 90).

Power is a theme in Emerson’s early writing, but it becomes especially prominent in such middle- and late-career essays as “Experience,” “Montaigne, or the Skeptic” “Napoleon,” and “Power.” Power is related to action in “The American Scholar,” where Emerson holds that a “true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power” (CW1: 59). It is also a subject of “Self-Reliance,” where Emerson writes of each person that “the power which resides in him is new in nature” (CW2: 28). In “Experience” Emerson speaks of a life which “is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy” (CW3: 294); and in “Power” he celebrates the “bruisers” (CW6: 34) of the world who express themselves rudely and get their way. The power in which Emerson is interested, however, is more artistic and intellectual than political or military. In a characteristic passage from “Power,” he states:

In history the great moment, is, when the savage is just ceasing to be a savage, with all his hairy Pelasgic strength directed on his opening sense of beauty:-and you have Pericles and Phidias,-not yet passed over into the Corinthian civility. Everything good in nature and the world is in that moment of transition, when the swarthy juices still flow plentifully from nature, but their astringency or acridity is got out by ethics and humanity. (CW6: 37–8)

Power is all around us, but it cannot always be controlled. It is like “a bird which alights nowhere,” hopping “perpetually from bough to bough” (CW3: 34). Moreover, we often cannot tell at the time when we exercise our power that we are doing so: happily we sometimes find that much is accomplished in “times when we thought ourselves indolent” (CW3: 28).

At some point in many of his essays and addresses, Emerson enunciates, or at least refers to, a great vision of unity. He speaks in “The American Scholar” of an “original unit” or “fountain of power” (CW1: 53), of which each of us is a part. He writes in “The Divinity School Address” that each of us is “an inlet into the deeps of Reason.” And in “Self-Reliance,” the essay that more than any other celebrates individuality, he writes of “the resolution of all into the ever-blessed ONE” (CW2: 40). “The Oversoul” is Emerson’s most sustained discussion of “the ONE,” but he does not, even there, shy away from the seeming conflict between the reality of process and the reality of an ultimate metaphysical unity. How can the vision of succession and the vision of unity be reconciled?

Emerson never comes to a clear or final answer. One solution he both suggests and rejects is an unambiguous idealism, according to which a nontemporal “One” or “Oversoul” is the only reality, and all else is illusion. He suggests this, for example, in the many places where he speaks of waking up out of our dreams or nightmares. But he then portrays that to which we awake not simply as an unchanging “ONE,” but as a process or succession: a “growth” or “movement of the soul” (CW2: 189); or a “new yet unapproachable America” (CW3: 259).

Emerson undercuts his visions of unity (as of everything else) through what Stanley Cavell calls his “epistemology of moods.” According to this epistemology, most fully developed in “Experience” but present in all of Emerson’s writing, we never apprehend anything “straight” or in-itself, but only under an aspect or mood. Emerson writes that life is “a train of moods like a string of beads,” through which we see only what lies in each bead’s focus (CW3: 30). The beads include our temperaments, our changing moods, and the “Lords of Life” which govern all human experience. The Lords include “Succession,” “Surface,” “Dream,” “Reality,” and “Surprise.” Are the great visions of unity, then, simply aspects under which we view the world?

Emerson’s most direct attempt to reconcile succession and unity, or the one and the many, occurs in the last essay in the Essays, Second Series , entitled “Nominalist and Realist.” There he speaks of the universe as an “old Two-face…of which any proposition may be affirmed or denied” (CW3: 144). As in “Experience,” Emerson leaves us with the whirling succession of moods. “I am always insincere,” he skeptically concludes, “as always knowing there are other moods” (CW3: 145). But Emerson enacts as well as describes the succession of moods, and he ends “Nominalist and Realist” with the “feeling that all is yet unsaid,” and with at least the idea of some universal truth (CW3: 363).

Massachusetts ended slavery in 1783, when Chief Justice William Cushing instructed the jury in the case of Quock Walker, a former slave, that “the idea of slavery” was “inconsistent” with the Massachusetts Constitution’ guarantee that “all men are born free and equal” (Gougeon, 71). Emerson first encountered slavery when he went south for his health in the winter of 1827, when he was 23. He recorded the following scene in his journal from his time in Tallahasse, Florida:

A fortnight since I attended a meeting of the Bible Society. The Treasurer of this institution is Marshal of the district & by a somewhat unfortunate arrangement had appointed a special meeting of the Society & a Slave Auction at the same time & place, one being in the Government house & the other in the adjoining yard. One ear therefore heard the glad tidings of great joy whilst the other was regaled with “Going gentlemen, Going!” And almost without changing our position we might aid in sending the scriptures into Africa or bid for “four children without the mother who had been kidnapped therefrom” (JMN3: 117).

Emerson never questioned the iniquity of slavery, though it was not a main item on his intellectual agenda until the eighteen forties. He refers to abolition in the “Prospects” chapter of Nature when he speaks of the “gleams of a better light” in the darkness of history and gives as examples “the abolition of the Slave-trade,” “the history of Jesus Christ,” and “the wisdom of children” (CW1:43). He condemns slavery in some of his greatest essays, “Self-Reliance” (1841), so that even if we didn’t have the anti-slavery addresses of the 1840s and 1850s, we would still have evidence both of the existence of slavery and of Emerson’s opposition to it. He praises “the bountiful cause of Abolition,” although he laments that the cause had been taken over by “angry bigots.” Later in the essay he treats abolition as one of the great causes and movements of world history, along with Christianity, the Reformation, and Methodism. In a well-known statement he writes that an “institution is the shadow of one man,” giving as examples “the Reformation, of Luther; Quakerism, of Fox; Methodism, of Wesley; Abolition of Clarkson” (CW2: 35). The unfamiliar name in this list is that of Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846), a Cambridge-educated clergyman who helped found the British Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Clarkson travelled on horseback throughout Britain, interviewing sailors who worked on slaving ships, and exhibiting such tools as manacles, thumbscews, branding irons, and other tools of the trade. His History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament (1808) would be a major source for Emerson’s anti-slavery addresses.

Slavery also appears in “Politics,” from the Essays, Second Series of 1844, when Emerson surveys the two main American parties. One, standing for free trade, wide suffrage, and the access of the young and poor to wealth and power, has the “best cause” but the least attractive leaders; while the other has the most cultivated and able leaders, but is “merely defensive of property.” This conservative party, moreover, “vindicates no right, it aspires to no real good, it brands no crime, it proposes no generous policy, it does not build nor write, nor cherish the arts, nor foster religion, nor establish schools, nor encourage science, nor emancipate the slave, nor befriend the poor, or the Indian, or the immigrant” (CW3: 124). Emerson stands here for emancipation, not simply for the ending of the slave trade.

1844 was also the year of Emerson’s breakout anti-slavery address, which he gave at the annual celebration of the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies. In the background was the American war with Mexico, the annexation of Texas, and the likelihood that it would be entering the Union as a slave state. Although Concord was a hotbed of abolitionism compared to Boston, there were many conservatives in the town. No church allowed Emerson to speak on the subject, and when the courthouse was secured for the talk, the sexton refused to ring the church bell to announce it, a task the young Henry David Thoreau took upon himself to perform (Gougeon, 75). In his address, Emerson develops a critique of the language we use to speak about, or to avoid speaking about, black slavery:

Language must be raked, the secrets of slaughter-houses and infamous holes that cannot front the day, must be ransacked, to tell what negro-slavery has been. These men, our benefactors, as they are producers of corn and wine, of coffee, of tobacco, of cotton, of sugar, of rum, and brandy, gentle and joyous themselves, and producers of comfort and luxury for the civilized world.… I am heart-sick when I read how they came there, and how they are kept there. Their case was left out of the mind and out of the heart of their brothers ( Emerson’s Antislavery Writings , 9).

Emerson’s long address is both clear-eyed about the evils of slavery and hopeful about the possibilities of the Africans. Speaking with the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass beside him on the dais, Emerson states: “The black man carries in his bosom an indispensable element of a new and coming civilization.” He praises “such men as” Toussaint [L]Ouverture, leader of the Haitian slave rebellion, and announces: “here is the anti-slave: here is man; and if you have man, black or white is an insignificance.” (Wirzrbicki, 95; Emerson’s Antislavery Writings, 31).

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 effectively nationalized slavery, requiring officials and citizens of the free states to assist in returning escaped slaves to their owners. Emerson’s 1851 “Address to the Citizens of Concord” calls both for the abrogation of the law and for disobeying it while it is still current. In 1854, the escaped slave Anthony Burns was shipped back to Virginia by order of the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, an order carried out by U. S. Marines, in accordance with the new law. This example of “Slavery in Massachusetts” (as Henry Thoreau put it in a well-known address) is in the background of Emerson’s 1855 “Lecture on Slavery,” where he calls the recognition of slavery by the original 1787 Constitution a “crime.” Emerson gave these and other antislavery addresses multiple times in various places from the late 1840s till the beginning of the Civil War. On the eve of the war Emerson supported John Brown, the violent abolitionist who was executed in 1859 by the U. S. government after he attacked the U. S. armory in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. In the middle of the War, Emerson raised funds for black regiments of Union soldiers (Wirzbicki, 251–2) and read his “Boston Hymn” to an audience of 3000 celebrating President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. “Pay ransom to the owner,” Emerson wrote, “and fill the bag to the brim. Who is the owner? The slave is owner. And ever was. Pay him” (CW9: 383).

Emerson’s magisterial essay “Fate,” published in The Conduct of Life (1860) is distinguished not only by its attempt to reconcile freedom and necessity, but by disturbing pronouncements about fate and race, for example: