- Advanced Search

Browse Theses

January 2020

- University of South Carolina

- Committee Members:

- Computer Science Dept. Columbia, SC

- United States

The purpose of this action research was to evaluate the effects of an asynchronous PD on teacher technology integration in the classroom as measured by the SAMR integration model. Teacher professional development is one of the most significant factors in student technology use in the classroom (Hall & Martin, 2008; Murthy, Iyer, & Warriem, 2015). Within a school day there are a number of requirements on teachers in addition to teaching their classes, such as attending parent conferences, department meetings, state mandated training, and many other initiatives that supersede teacher technology training (Garthwait & Weller, 2005). When provided with an online model, allowing teachers to work at their leisure has been shown in some cases to increase the amount of professional development teachers willingly take (Paskevicius & Bortolin, 2015; Russell, Carey, Kleiman, & Venable, 2009). This study focused on three questions. The first question sought to explore the ways asynchronous teacher PD on the SAMR model impact the planning process. The second question explored how and in what ways asynchronous teacher professional development on the SAMR model impact teachers' classroom technology integration. The third sought to determine teachers' perceptions about the effectiveness of asynchronous teacher professional development. This study incorporated an online professional development module on classroom technology integration to provide high school teachers with specific technology-related resources, tools, and ideas to use in the classroom. The number of participants is five classroom teachers. Data collection consisted of a pre-survey, gauging teacher's current levels of technology integration in the classroom, observations, a mirrored post-survey and individual interviews with selected participants. Data were analyzed through a mixed-methods approach using descriptive statistics for the quantitative measures and literal transcription and inductive analysis for qualitative measures (Mertler, 2017). Results of this six-week study suggest a positive correlation between asynchronous teacher professional development and the thoughtful inclusion of technology when planning, increased levels of teacher technology use in the classroom, as well as a favorable outlook on asynchronous professional development in general. Research highlighted the need for collaboration between participants when participating asynchronously.

Save to Binder

- Publication Years 2020 - 2020

- Publication counts 1

- Citation count 0

- Available for Download 0

- Downloads (cumulative) 0

- Downloads (12 months) 0

- Downloads (6 weeks) 0

- Average Downloads per Article 0

- Average Citation per Article 0

- Publication Years

- Publication counts 0

- Publication Years 2011 - 2011

- Citation count 2

- Available for Download 1

- Downloads (cumulative) 357

- Downloads (12 months) 4

- Downloads (6 weeks) 2

- Average Downloads per Article 357

- Average Citation per Article 2

- Publication Years 2010 - 2022

- Publication counts 4

- Citation count 22

- Average Citation per Article 6

Index Terms

Applied computing

Collaborative learning

Human-centered computing

Collaborative and social computing

Information systems

World Wide Web

Social and professional topics

Professional topics

Management of computing and information systems

Project and people management

Recommendations

From professional development to the classroom: findings from cs k-12 teachers.

The CS for All initiative places increased emphasis on the need to prepare K-12 teachers of computer science (CS). Professional development (PD) programs continue to be an essential mechanism for preparing in-service teachers who have little formal ...

Early Information Technology Program High School Teachers' Training and Continual Professional Development

The School of Information Technology (SoIT) established an Early IT program where the six, first-year IT courses of the Bachelor of Science in Information Technology (BSIT) degree are taught in the local schools by certified high school teachers. These ...

Technology workshops by in-service teachers for pre-service teachers

This project was an initiative through university courses to have graduate in-service teachers, who have learned the use of technology for classroom instruction, offer workshops to undergraduate pre-service teachers. The goals of the project were two-...

Export Citations

- Please download or close your previous search result export first before starting a new bulk export. Preview is not available. By clicking download, a status dialog will open to start the export process. The process may take a few minutes but once it finishes a file will be downloadable from your browser. You may continue to browse the DL while the export process is in progress. Download

- Download citation

- Copy citation

We are preparing your search results for download ...

We will inform you here when the file is ready.

Your file of search results citations is now ready.

Your search export query has expired. Please try again.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

Technology can close achievement gaps, improve learning.

As school districts around the country consider investments in technology in an effort to improve student outcomes, a new report from the Alliance for Excellent Education and the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE) finds that technology - when implemented properly -can produce significant gains in student achievement and boost engagement, particularly among students most at risk.

“This report makes clear that districts must have a plan in place for how they will use technology before they make a purchase,” said Bob Wise, president of the Alliance for Excellent Education and former governor of West Virginia. “It also underscores that replacing teachers with technology is not a successful formula. Instead, strong gains in achievement occur by pairing technology with classroom teachers who provide real-time support and encouragement to underserved students.”

Written by Professors Linda Darling-Hammond and Shelley Goldman at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and doctoral student Molly B. Zielezinski, the report is based on a review of more than 70 recent research studies and provides concrete examples of classroom environments in which technology has made a positive difference in the learning outcomes of students at risk of failing courses and dropping out.

Specifically, it identifies three important components to successfully using technology with at-risk students: interactive learning, use of technology to explore and create rather than to “drill and kill,” and the right blend of teachers and technology.

The report, Using Technology to Support At-Risk Students’ Learning , also identifies significant disparities in technology access and implementation between affluent and low-income schools. First, low-income teens and students of color are noticeably less likely to own computers and use the internet than their peers. Because of their students’ lack of access, teachers in high-poverty schools were more than twice likely (56 percent versus 21 percent) to say that their students’ lack of access to technology was a challenge in their classrooms. More dramatically, only 3 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools said that their students have the digital tools necessary to complete homework assignments, compared to 52 percent of teachers in more affluent schools.

Secondly, applications of technology in low-income schools typically involves a “drill and kill” approach in which computers take over for teachers and students are presented with information they are expected to memorize and are then tested on with multiple-choice questions. In more affluent schools, however, students tend to be immersed in more interactive environments in which material is customized based on students’ learning needs and teachers supplement instruction with technology to explain concepts, coordinate student discussion, and stimulate high-level thinking.

“When given access to appropriate technology used in thoughtful ways, all students—regardless of their respective backgrounds—can make substantial gains in learning and technological readiness,” said Darling-Hammond, the faculty director of SCOPE. “Unfortunately, applications of technology in schools serving the most disadvantaged students are frequently compromised by the same disparities in dollars, teachers, and instructional services that typically plague these schools. These disparities are compounded by the lack of access to technology in these students’ homes.”

The report includes several recommendations that could expand the use and impact of technology among at-risk high school youth:

- Technology access policies should aim for one-to-one computer access;

- Technology access policies should ensure that speedy internet connections are available;

- States, districts, and schools should favor technology designed to promote high levels of interactivity and engagement and make data available in multiple forms;

- Curriculum and instruction plans should enable students to use technology to create content as well as learn material; and

- Policymakers and educators should plan for “blended” learning environments, characterized by significant levels of teacher support and opportunities for interactions among students, as companions to technology use.

The report cautions that its recommendations must be accompanied by adequate professional learning opportunities for teachers on how to use the technology and pedagogies that are recommended, including technical assistance to help educators manage the hardware, software and connections to the Internet.

Darling-Hammond and Zielezinski joined Tom Murray, the Alliance’s state and district digital learning director, for a video webinar to discuss the report’s findings on Sept. 10. For archived video, please visit: http://all4ed.org/webinar-event/sep-10-2014/ .

This story was written by the communications staff at the Alliance for Excellent Education in Washington, DC, and is also posted at www.all4ed.org .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

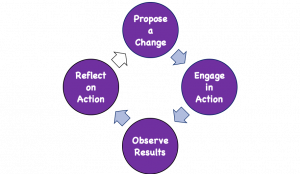

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

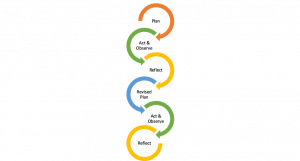

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

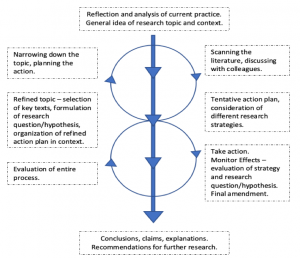

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Embrace Action Research

Improve classroom practice with action research ... and tell the story

The action research process can help you understand what is happening in your classroom and identify changes that improve teaching and learning. Action research can help answer questions you have about the effectiveness of specific instructional strategies, the performance of specific students, and classroom management techniques.

Educational research often seems removed from the realities of the classroom. For many classroom educators, formal experimental research, including the use of a control group, seems to contradict the mandate to improve learning for all students. Even quasi-experimental research with no control group seems difficult to implement, given the variety of learners and diverse learning needs present in every classroom.

Action research gives you the benefits of research in the classroom without these obstacles. Believe it or not, you are probably doing some form of research already. Every time you change a lesson plan or try a new approach with your students, you are engaged in trying to figure out what works. Even though you may not acknowledge it as formal research, you are still investigating, implementing, reflecting, and refining your approach.

Qualitative research acknowledges the complexity of the classroom learning environment. While quantitative research can help us see that improvements or declines have occurred, it does not help us identify the causes of those improvements or declines. Action research provides qualitative data you can use to adjust your curriculum content, delivery, and instructional practices to improve student learning. Action research helps you implement informed change!

The term “action research” was coined by Kurt Lewin in 1944 to describe a process of investigation and inquiry that occurs as action is taken to solve a problem. Today we use the term to describe a practice of reflective inquiry undertaken with the goal of improving understanding and practice. You might consider “action” to refer to the change you are trying to implement and “research” to refer to your improved understanding of the learning environment.

Action research also helps you take charge of your personal professional development. As you reflect on your own actions and observe other master teachers, you will identify the skills and strategies you would like to add to your own professional toolbox. As you research potential solutions and are exposed to new ideas, you will identify the skills, management, and instructional training needed to make the changes you want to see.

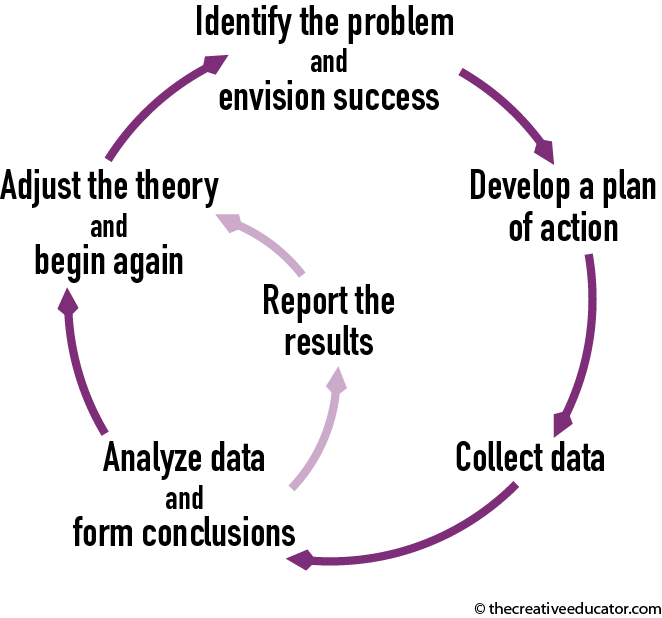

The Action Research Cycle

Action research is a cycle of inquiry and reflection. During the process, you will determine 1) where you are, 2) where you want to be, and 3) how you are going to get there. In general terms, the cycle follows these steps:

- Identify the problem and envision success

- Develop a plan of action

- Collect data

- Analyze data and form conclusions

- Modify your theory and repeat the cycle

- Report the results

Identify the Problem

The process begins when you identify a question or problem you want to address. Action research is most successful when you have a personal investment, so make sure the questions you are asking are ones YOU want to solve. This could be an improvement you want to see happen in your classroom (or your school if you are a principal), or a problem you and your colleagues would like to address in your district.

Learning to develop the right questions takes time. Your ability to identify these key questions will improve with each iteration of the research cycle. You want to select a question that isn’t so broad it is almost impossible to answer or so narrow that the only answer is yes or no. Choose questions that can be answered within the context of your daily teaching. In other words, choose a question that is both answerable and worthy of the time investment required to learn the answer.

Questions you could ask might involve management issues, curriculum implementation, instructional strategies, or specific student performance. For example, you might consider:

- How successful is random grouping for project work?

- Why is the performance of one student lacking in a particular area?

- Will increasing the amount of feedback I provide improve students’ writing skills?

- What is the best way to introduce the concept of fractions?

- Which procedure is most effective for managing classroom conflict?

Determining the question helps focus your inquiry.

Before you can start collecting data, you need to have a clear vision of what success looks like. Start by brainstorming words that describe the change you want to see. What strategies do you already know that might help you get there? Which of these ideas do you think might work better than what you are currently doing?

To find out if a new instructional strategy is worth trying, conduct a review of literature. This doesn’t have to mean writing up a formal lit review like you did in graduate school. The important thing is to explore a range of articles and reports on your topic and capitalize on the research and experience of others. Your classroom responsibilities are already many and may be overwhelming. A review of literature can help you identify useful strategies and locate information that helps you justify your action plan.

The Web makes literature reviews easier to accomplish than ever before. Even if the full text of an article, research paper, or abstract is not available online, you will be able to find citations to help you locate the source materials at your local library. Collect as much information on your problem as you can find. As you explore the existing literature, you will certainly find solutions and strategies that others have implemented to solve this problem. You may want to create a visual map or a table of your problems and target performances with a list of potential solutions and supporting citations in the middle.

Develop an Action Plan

Now that you have identified the problem, described your vision of how to successfully solve it, and reviewed the pertinent literature, you need to develop a plan of action. What is it that you intend to DO? Brainstorming and reviewing the literature should have provided you with ideas for new techniques and strategies you think will produce better results. Refer back to your visual map or table and color-code or reorder your potential solutions. You will want to rank them in order of importance and indicate the amount of time you will need to spend on these strategies.

How can you implement these techniques? How will you? Translate these solutions into concrete steps you can and will take in your classroom. Write a description of how you will implement each idea and the time you will take to do it.

Once you have a clear vision of a potential solution to the problem, explore factors you think might be keeping you and your students from your vision of success. Recognize and accept those factors you do not have the power to change–they are the constants in your equation. Focus your attention on the variables–the parts of the formula you believe your actions can impact.

Develop a plan that shows how you will implement your solution and how your behavior, management style, and instruction will address each of the variables. Sometimes an action research cycle simply helps you identify variables you weren’t even aware of, so you can better address your problem during the next cycle!

Collect Data

Before you begin to implement your plan of action, you need to determine what data will help you understand if your plan succeeds, and how you will collect that data. Your target performances will help you determine what you want to achieve. What results or other indicators will help you know if you achieved it? For example, if your goal is improved attendance, data can easily be collected from your attendance records. If the goal is increased time on task, the data may include classroom and student observations.

There are many options for collecting data. Choosing the best methodologies for collecting information will result in more accurate, meaningful, and reliable data.

Obvious sources of data include observation and interviews. As you observe, you will want to type or write notes or dictate your observations into a cell phone, iPod, or PDA. You may want to keep a journal during the process, or even create a blog or wiki to practice your technology skills as you collect data.

Reflective journals are often used as a source of data for action research. You can also collect meaningful data from other records you deal with daily, including attendance logs, grade reports, and student portfolios. You could distribute questionnaires, watch videotapes of your classroom, and administer surveys. Examples of student work are also performances you can evaluate to see if your goal is being met.

Create a plan for data collection and follow it as you perform your research. If you are going to interview students or other teachers, how many times will you do it? At what times during the day? How will you ensure your respondents are representative of the student population you are studying, including gender, ability level, experience, and expertise?

Your plan will help you ensure that you have collected data from many different sources. Each source of data provides additional information that will help you answer the questions in your research plan.

You may also want to have students collect data on their own learning. Not only does this provide you with additional research assistants, it empowers students to take control of their own learning. As students keep a journal during the process, they are also reflecting on the learning environment and their own learning process.

Analyze Data and Form Conclusions

The next step in the process is to analyze your data and form conclusions. Start early! Examining the data during the collection process can help you refine your action plan. Is the data you are collecting sufficient? If not, you have an opportunity to revise your data collection plan. Your analysis of the data will also help you identify attitudes and performances to look for during subsequent observations.

Analyzing the data also helps you reflect on what actually happened. Did you achieve the outcomes you were hoping for? Where you able to carry out your actions as planned? Were any of your assumptions about the problem incorrect?

Adding data such as opinions, attitudes, and grades to tables can help you identify trends (relationships and correlations). For example, if you are completing action research to determine if project-based learning is impacting student motivation, graphing attendance and disruptive behavior incidents may help you answer the question. A graph that shows an increase in attendance and a decrease in the number of disruptive incidents over the implementation period would lead you to believe that motivation was improved.

Draw tentative conclusions from your analysis. Since the goal of action research is positive change, you want to try to identify specific behaviors that move you closer to your vision of success. That way you can adjust your actions to better achieve your goal of improved student learning.

Action research is an iterative process. The data you collect and your analysis of it will affect how you approach the problem and implement your action plan during the next cycle.

Even as you begin drawing conclusions, continue collecting data. This will help you confirm your conclusions or revise them in light of new information. While you can plan how long and often you will collect data, you may also want to continue collecting until the trends have been identified and new data becomes redundant.

As you are analyzing your data and drawing conclusions, share your findings. Discussing your results with another teacher can often yield valuable feedback. You might also share your findings with your students who can also add additional insight. If they agree with your conclusions, you have added credibility to your data collection plan and analysis. If they disagree, you will know to reevaluate your conclusions or refine your data collection plan.

Modify Your Theory and Repeat

Now that you have formed a final conclusion, the cycle begins again. In light of your findings, you should have adjusted your theory or made it more specific. Modify your plan of action, begin collecting data again, or begin asking new questions!

Report the Results

While the ultimate goal of your research is to promote effective change in your classroom or schools, do not underestimate the value of sharing your findings with others. Sharing your results helps you further reflect on the process and problem, and it allows others to use your results to help them in their own endeavors to improve the education of their students.

You can report your findings in many different ways. You most certainly will want to share the experience with your students, parents, teachers, and principal. Provide them with an overview of the process and share highlights from your research journal. Because each of these audiences is different, you will need to adjust the content and delivery of the information each time you share. You may also want to present your process at a conference so educators from other districts can benefit from your work.

As your skill with the action research cycle gets stronger, you may want to develop an abstract and submit an article to an educational journal. To write an abstract, state the problem you were trying to solve, describe your context, detail your action plan and methods, summarize your findings, state your conclusions, and explain your revised action plan.

If your question focused on the implementation of an action plan to improve the performance of a particular student, what better way to show the process and results than through digital storytelling? Using a tool like Wixie , you can share images, audio, artifacts and more to show the student’s journey. Action research is outside-the-box thinking… so find similarly unique ways to report your findings!

All teachers want to reach their students more effectively and help them become better learners and citizens. Action research provides a reflective process you can use to implement changes in your classroom and determine if those changes result in the desired outcome.

Your ideas and experience combined with action research are a powerful formula for effective change!

Grady, M.P. (1998). Qualitative and Action Research. Bloomington: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Sagor, R. (2005). The Action Research Handbook. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

by Melinda Kolk

Melinda Kolk ( @melindak ) is the Editor of Creative Educator and the author of Teaching with Clay Animation . She has been helping educators implement project-based learning and creative technologies like clay animation into classroom teaching and learning for the past 15 years.

Get the latest from Creative Educator

Creative classroom ideas delivered straight to your in box once a month.

Add me to the Creative Educator email list!

Popular Topics

Digital Storytelling

21st Century Classrooms

Project-based Learning

- Hero's Journey Lesson Plan

- Infographics Lesson Plan

- Design a Book Cover Lesson Plan

- Informational text projects that build thinking and creativity

- Classroom constitution Lesson Plan

- Set SMART Goals Lesson Plan

- Create a visual poem Lesson Plan

- Simple surveys and great graphs Lesson Plan

- Embrace action research

Build foundations for independent thinking

Your first action research cycle

Find and measure hidden objectives

What can your students create?

More sites to help you find success in your classroom

Share your ideas, imagination, and understanding through writing, art, voice, and video.

Rubric Maker

Create custom rubrics for your classroom.

Pics4Learning

A curated, copyright-friendly image library that is safe and free for education.

Write, record, and illustrate a sentence.

Interactive digital worksheets for grades K-8 to use in Brightspace or Canvas.

Professional Learning

Teaching and Learning

Informational Text

English Language Aquisition

Language Arts

Social Studies

Visual Arts

© 2024 Tech4Learning, Inc | All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy

© 2024 Tech4Learning, Inc | All Rights Reserved | https://www.thecreativeeducator.com

Advertisement

Collaborative Action Research on Technology Integration for Science Learning

- Published: 15 March 2011

- Volume 21 , pages 125–132, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Chien-hsing Wang 1 ,

- Yi-Ting Ke 1 ,

- Jin-Tong Wu 1 &

- Wen-Hua Hsu 1

1335 Accesses

17 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper briefly reports the outcomes of an action research inquiry on the use of blogs, MS PowerPoint [PPT], and the Internet as learning tools with a science class of sixth graders for project-based learning. Multiple sources of data were essential to triangulate the key findings articulated in this paper. Corresponding to previous studies, the incorporation of technology and project-based learning could motivate students in self-directed exploration. The students were excited about the autonomy over what to learn and the use of PPT to express what they learned. Differing from previous studies, the findings pointed to the lack information literacy among students. The students lacked information evaluation skills, note-taking and information synthesis. All these findings imply the importance of teaching students about information literacy and visual literacy when introducing information technology into the classroom. The authors suggest that further research should focus on how to break the culture of “copy-and-paste” by teaching the skills of note-taking and synthesis through inquiry projects for science learning. Also, further research on teacher professional development should focus on using collaboration action research as a framework for re-designing graduate courses for science teachers in order to enhance classroom technology integration.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

What happens when you push the button analyzing the functional dynamics of concept development in computer supported science inquiry, professional learning of k-6 teachers in science through collaborative action research: an activity theory analysis.

Inquiry Process Skills in Primary Science Textbooks: Authors and Publishers’ Intentions

Almås AG, Krumsvik R (2007) Digitally literate teachers in leading edge schools in Norway. J In-Service Educ 33(4):479–497

Article Google Scholar

American Association of School Librarians (AASL) and Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT) (1998) Information literacy standards for student learning. http://www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/aaslarchive/pubsarchive/informationpower/InformationLiteracyStandards_final.pdf . Retrieved 1 March 2010

Auer NJ, Krupar EM (2001) Mouse click plagiarism: the role of technology in plagiarism and the librarian’s role in combating it. Libr Trends 49(3):415–432

Google Scholar

Barak M, Dori YJ (2005) Enhancing undergraduate students’ chemistry understanding through project-based learning in an IT environment. Sci Educ 89(1):117–139

Barron B, Schwartz D, Vye N, Moore A, Petrosino A, Zech L, Bransford, & The Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbit (1998) Doing with understanding: lessons from research on problem-and project-based learning. J Learn Sci 7(3):271–311

Bartsch RA, Cobern KM (2003) Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Comput Educ 41(1):77

Baumfield V, Hall E, Wall K (2008) Action research in the classroom. Sage, Los Angeles

Burke LA, James K, Ahmadi M (2009) Effectiveness of PowerPoint-Based lectures across different business disciplines: an investigation and implications. J Educ Bus 84(4):246–251

Churchill D (2009) Educational applications of Web 2.0: using blogs to support teaching and learning: original articles. Br J Educ Technol 40(1):179–183

Clark J (2008) Powerpoint and pedagogy: maintaining student interest in university lectures. Coll Teach 56(1):39–44

Danielson C (2007) Enhancing professional practice: a framework for teaching, 2nd edn. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria

Dastani M (2002) The role of visual perception in data visualization. J Vis Lang Comput 13(6):601–622

Dawson V, Forster P, Reid D (2006) Information communication technology (ICT) integration in a science education unit for preservice science teachers; students’ perceptions of their ICT skills, knowledge and pedagogy. Int J Sci Math Educ 4(2):345–363

Dede C (1998) The scaling-up process for technology-based education innovations. In: Dede C (ed) Learning with technology. ASCD, Alexandria, pp 199–215

Eisenberg MB (2008) Information literacy: essential skills for the information age. J Lib Inf Technol 28(2):39–47

Ellery K (2008) An investigation into electronic-source plagiarism in a first-year essay assignment. Assess Evaluation High Educ 33(6):607–617

Grant M (2002) Getting a grip on project-based learning: theory, cases and recommendations. Meridian: A Middle School Comput Technol J 5(1):83

Kerawalla L, Minocha S, Kirkup G, Conole G (2009) An empirically grounded framework to guide blogging in higher education. J Comput Assist Learn 25(1):31–42

Kinchin I (2006) Developing PowerPoint handouts to support meaningful learning. Br J Educ Technol 37(4):647–650

Krumsvik R (2006) The digital challenges of school and teacher education in Norway: some urgent questions and the search for answers. Educ Inf Technol 11(3–4):239–256

Marx R, Blumenfeld P, Krajcik J, Soloway E (1997) Enacting project-based science. Elem School J 97(4):341–358

McPherson S (2009) A dance with the butterflies: a metamorphosis of teaching and learning through technology. J Early Child Educ 37(3):229–236

Metros SE (2008) The educator’s role in preparing visually literate learners. Theory Pract 47(2):102–109

Pettersson R (2009) Visual literacy and message design. TechTrends 53(2):38–40

Probert E (2009) Information literacy skills: teacher understandings and practice. Comput Educ 53(1):24–33

Savoy A, Proctor RW, Salvendy G (2009) Information retention from PowerPoint™ and traditional lectures. Comput Educ 52(4):858–867

Sosa T (2009) Visual literacy: the missing piece of your technology integration course. TechTrends 53(2):55–58

Stringer E (2007) Action research in education, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Su KD (2008) An integrated science course designed with information communication technologies to enhance university students’ learning performance. Comput Educ 51(3):1365–1374

Thomas JW (2000) A review of research on project-based learning. Autodesk Foundation, San Rafael. http://bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Research.pdf . Retrieved 9 March 2011

Walraven A, Brand-gruwel S, Boshuizen HPA (2008) Information-problem solving: a review of problems students encounter and instructional solutions. Comput Hum Behav 24(3):623–648

Wilson B (ed) (1996) Constructivist learning environments: case studies in instructional design. Educational Technology Publications, Englewood Cliffs

Yeh HT, Cheng YC (2010) The influence of the instruction of visual design principles on improving pre-service teachers’ visual literacy. Comput Educ 54(1):244–252

Yore LD, Bisanz GL, Hand BM (2003) Examining the literacy component of science literacy: 25 years of language arts and science research. Int J Sci Edu 25(6):689–725

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate Institute of Education, National Changhua University of Education, 1, Jin De Road, Paisha Village, Changhua City, Zip 500, Taiwan, ROC

Chien-hsing Wang, Yi-Ting Ke, Jin-Tong Wu & Wen-Hua Hsu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chien-hsing Wang .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wang, Ch., Ke, YT., Wu, JT. et al. Collaborative Action Research on Technology Integration for Science Learning. J Sci Educ Technol 21 , 125–132 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-011-9289-0

Download citation

Published : 15 March 2011

Issue Date : February 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-011-9289-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Science learning

- Technology integration

- Elementary education

- Teaching/learning strategies

- Pedagogical issues

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Exploring the Use of Technology in the Classroom: A Qualitative Study of Students' and Teachers' Experience

- Tanjina Azad North South University

The integration of technology in the classroom has become increasingly popular, with many educators seeing it as a way to enhance teaching and learning. However, there is a need to understand how technology is being used and how it is impacting both students and teachers. This qualitative study aimed to explore students' and teachers’ experiences on the use of technology in the classroom. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight teachers and ten students in a high school in the United States. The interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis. The findings revealed that technology was perceived as a valuable tool for enhancing learning, but that there were also challenges associated with its use, such as technical difficulties and distractions. Additionally, students and teachers had differing opinions on how technology should be used in the classroom, with some students preferring a more traditional approach to learning. Overall, this study highlights the need for careful consideration of how technology is integrated into the classroom, as well as the importance of understanding students' and teachers' experience on its use.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2023 Tanjina Azad

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Current Issue

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Editorial Team Reviewers Focus and Scope Peer Review Process Publications Ethics Article Processing Charges Plagiarism Check Open Access Policy Author Guidelines

Contact Journal

Social Media

Journal Visitors

On The Site

Teaching About Technology in Schools Through Technoskeptical Inquiry

June 3, 2024 | victorialynn | Harvard Educational Review Contributors , Voices in Education

By Jacob Pleasants, Daniel G. Krutka, and T. Philip Nichols

New technologies are rapidly transforming our societies, our relationships, and our schools. Look no further than the intense — and often panicked — discourse around generative AI , the metaverse , and the creep of digital media into all facets of civic and social life . How are schools preparing students to think about and respond to these changes?

In various ways, students are taught how to use technologies in school. Most schools teach basic computing skills and many offer elective vocational-technical classes. But outside of occasional conversations around digital citizenship, students rarely wrestle with deeper questions about the effects of technologies on individuals and society.

Decades ago, Neil Postman (1995) argued for a different form of technology education focused on teaching students to critically examine technologies and their psychological and social effects. While Postman’s ideas have arguably never been more relevant, his suggestion to add technology education as a separate subject to a crowded curriculum gained little traction. Alternatively, we argue that technology education could be an interdisciplinary endeavor that occurs across core subject areas. Technology is already a part of English Language Arts (ELA), Science, and Social Studies instruction. What is missing is a coherent vision and common set of practices and principles that educators can use to align their efforts.

To provide a coherent vision, in our recent HER article , we propose “technoskepticism” as an organizing goal for teaching about technology. We define technoskepticism as a critical disposition and practice of investigating the complex relationships between technologies and societies. A technoskeptical person is not necessarily anti-technology, but rather one who deeply examines technological issues from multiple dimensions and perspectives akin to an art critic.

We created the Technoskepticism Iceberg as a framework to support teachers and students in conducting technological inquiries. The metaphor of an iceberg conveys how many important influences of technology lie beneath our conscious awareness. People often perceive technologies as tools (the “visible” layer of the iceberg), but technoskepticism requires that they be seen as parts of systems (with interactions that produce many unintended effects) and embedded with values about what is good and desirable (and for whom). The framework also identifies three dimensions of technology that students can examine. The technical dimension concerns the design and functions of a technology, including how it may work differently for different people. The psychosocial dimension addresses how technologies change our individual cognition and our larger societies. The political dimension considers who makes decisions concerning the terms, rules, or laws that govern technologies.

To illustrate these ideas, how might we use the Technoskeptical Iceberg to interrogate generative AI such as ChatGPT in the core subject areas?

A science/STEM classroom might focus on the technical dimension by investigating how generative AI works and demystifying its ostensibly “intelligent” capabilities. Students could then examine the infrastructures involved in AI systems , such as immense computing power and specialized hardware that in turn have profound environmental consequences. A teacher could ask students to use their values to weigh the costs and potential benefits of ChatGPT.

A social studies class could investigate the psychosocial dimension through the longer histories of informational technologies (e.g., the printing press, telegraph, internet, and now AI) to consider how they shifted people’s lives. They could also explore political questions about what rules or regulations governments should impose on informational systems that include people’s data and intellectual property.

In an ELA classroom, students might begin by investigating the psychosocial dimensions of reading and writing, and the values associated with different literacy practices. Students could consider how the concept of “authorship” shifts when one writes by hand, with word processing software, or using ChatGPT. Or how we are to engage with AI-generated essays, stories, and poetry differently than their human-produced counterparts. Such conversations would highlight how literary values are mediated by technological systems .

Students who use technoskepticism to explore generative AI technologies should be better equipped to act as citizens seeking to advance just futures in and out of schools. Our questions are, what might it take to establish technoskepticism as an educational goal in schools? What support will educators need? And what might students teach us through technoskeptical inquiries?

Postman, N. (1995). The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School. Vintage Books.

About the Authors

Jacob Pleasants is an assistant professor of science education at the University of Oklahoma. Through his teaching and research, he works to humanize STEM education by helping students engage with issues at the intersection of STEM and society.

Daniel G. Krutka is a dachshund enthusiast, former high school social studies teacher, and associate professor of social studies education at the University of North Texas. His research concerns technology, democracy, and education, and he is the cofounder of the Civics of Technology project ( www.civicsoftechnology.org ).

T. Philip Nichols is an associate professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Baylor University. He studies the digitalization of public education and the ways science and technology condition the ways we practice, teach, and talk about literacy.

They are the authors of “ What Relationships Do We Want with Technology? Toward Technoskepticism in Schools ” in the Winter 2023 issue of Harvard Educational Review .

- Gift Guides

- Voices in Education

Technology in the Classroom: Stories of Digital Education

Holly Stepp

- May 29, 2024

For generations, education has seen the latest technologies change classroom instruction from the pencil replacing the slate and chalk and mimeograph to VCRs and personal computers. Technology always changes how teachers teach and how students learn.

The advent of artificial intelligence, or AI, and its related chatbots and language generators means teachers and students have yet another resource that changes the classroom experience.

For some teachers, it’s an opportunity to guide students’ exploration – teaching them how to use the AI to support their work in the classroom. For others, the proliferation of AI tools makes traditional teaching methods more important. And many students already in college are saying “why not both?” and figuring out where technology helps study and learning.

The classroom is not the only place where technology is changing the basics of education. In a digital age where keyboards are ubiquitous, handwriting and cursive in particular is making a comeback. And new technology tools have helped College Board make the vocabulary on new digital SAT a better test of reading comprehension and more aligned to what students will experience in college.

In the Spring edition of The Elective, we take a look at how technology is changing education and how some fundamentals are staying the same.

Will AI Aid Learning or Undercut It?

High school teachers grapple with how much ai is right for the classroom.

Amid all the hype and panic over artificial intelligence, one thing is already clear: a new generation of advanced AI programs is transforming the classroom, and school officials are racing to keep up. Two Advanced Placement teachers take different approaches to AI in the classroom.

Read more .

Related Posts

Digital Education

AI as a New Study Aid

Can cursive survive in the digital age, rules for robots: how one of america’s top high schools is cautiously embracing ai, sat vocabulary in the digital age.

Classroom Tech Outpaces Research. Why That’s a Problem

- Share article

Classroom tools and technology are changing too fast for traditional research to keep up without significant support to identify best practices and get them into the classroom.

That was the consensus of state education leaders, equity advocates, and ed-tech experts at a symposium on the future of education research and development, held to standing-room-only on Capitol Hill Thursday.