Essays About Beauty: Top 5 Examples and 10 Prompts

Writing essays about beauty is complicated because of this topic’s breadth. See our examples and prompts to you write your next essay.

Beauty is short for beautiful and refers to the features that make something pleasant to look at. This includes landscapes like mountain ranges and plains, natural phenomena like sunsets and aurora borealis, and art pieces such as paintings and sculptures. However, beauty is commonly attached to an individual’s appearance, fashion, or cosmetics style, which appeals to aesthetical concepts. Because people’s views and ideas about beauty constantly change , there are always new things to know and talk about.

Below are five great essays that define beauty differently. Consider these examples as inspiration to come up with a topic to write about.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. Essay On Beauty – Promise Of Happiness By Shivi Rawat

2. defining beauty by wilbert houston, 3. long essay on beauty definition by prasanna, 4. creative writing: beauty essay by writer jill, 5. modern idea of beauty by anonymous on papersowl, 1. what is beauty: an argumentative essay, 2. the beauty around us, 3. children and beauty pageants, 4. beauty and social media, 5. beauty products and treatments: pros and cons, 6. men and makeup, 7. beauty and botched cosmetic surgeries, 8. is beauty a necessity, 9. physical and inner beauty, 10. review of books or films about beauty.

“In short, appreciation of beauty is a key factor in the achievement of happiness, adds a zest to living positively and makes the earth a more cheerful place to live in.”

Rawat defines beauty through the words of famous authors, ancient sayings, and historical personalities. He believes that beauty depends on the one who perceives it. What others perceive as beautiful may be different for others. Rawat adds that beauty makes people excited about being alive.

“No one’s definition of beauty is wrong. However, it does exist and can be seen with the eyes and felt with the heart.”

Check out these essays about best friends .

Houston’s essay starts with the author pointing out that some people see beauty and think it’s unattainable and non-existent. Next, he considers how beauty’s definition is ever-changing and versatile. In the next section of his piece, he discusses individuals’ varying opinions on the two forms of beauty: outer and inner.

At the end of the essay, the author admits that beauty has no exact definition, and people don’t see it the same way. However, he argues that one’s feelings matter regarding discerning beauty. Therefore, no matter what definition you believe in, no one has the right to say you’re wrong if you think and feel beautiful.

“The characteristic held by the objects which are termed “beautiful” must give pleasure to the ones perceiving it. Since pleasure and satisfaction are two very subjective concepts, beauty has one of the vaguest definitions.”

Instead of providing different definitions, Prasanna focuses on how the concept of beauty has changed over time. She further delves into other beauty requirements to show how they evolved. In our current day, she explains that many defy beauty standards, and thinking “everyone is beautiful” is now the new norm.

“…beauty has stolen the eye of today’s youth. Gone are the days where a person’s inner beauty accounted for so much more then his/her outer beauty.”

This short essay discusses how people’s perception of beauty today heavily relies on physical appearance rather than inner beauty. However, Jill believes that beauty is all about acceptance. Sadly, this notion is unpopular because nowadays, something or someone’s beauty depends on how many people agree with its pleasant outer appearance. In the end, she urges people to stop looking at the false beauty seen in magazines and take a deeper look at what true beauty is.

“The modern idea of beauty is taking a sole purpose in everyday life. Achieving beautiful is not surgically fixing yourself to be beautiful, and tattoos may have a strong meaning behind them that makes them beautiful.”

Beauty in modern times has two sides: physical appearance and personality. The author also defines beauty by using famous statements like “a woman’s beauty is seen in her eyes because that’s the door to her heart where love resides” by Audrey Hepburn. The author also tackles the issue of how physical appearance can be the reason for bullying, cosmetic surgeries, and tattoos as a way for people to express their feelings.

Looking for more? Check out these essays about fashion .

10 Helpful Prompts To Use in Writing Essays About Beauty

If you’re still struggling to know where to start, here are ten exciting and easy prompts for your essay writing:

While defining beauty is not easy, it’s a common essay topic. First, share what you think beauty means. Then, explore and gather ideas and facts about the subject and convince your readers by providing evidence to support your argument.

If you’re unfamiliar with this essay type, see our guide on how to write an argumentative essay .

Beauty doesn’t have to be grand. For this prompt, center your essay on small beautiful things everyone can relate to. They can be tangible such as birds singing or flowers lining the street. They can also be the beauty of life itself. Finally, add why you think these things manifest beauty.

Little girls and boys participating in beauty pageants or modeling contests aren’t unusual. But should it be common? Is it beneficial for a child to participate in these competitions and be exposed to cosmetic products or procedures at a young age? Use this prompt to share your opinion about the issue and list the pros and cons of child beauty pageants.

Today, social media is the principal dictator of beauty standards. This prompt lets you discuss the unrealistic beauty and body shape promoted by brands and influencers on social networking sites. Next, explain these unrealistic beauty standards and how they are normalized. Finally, include their effects on children and teens.

Countless beauty products and treatments crowd the market today. What products do you use and why? Do you think these products’ marketing is deceitful? Are they selling the idea of beauty no one can attain without surgeries? Choose popular brands and write down their benefits, issues, and adverse effects on users.

Although many countries accept men wearing makeup, some conservative regions such as Asia still see it as taboo. Explain their rationale on why these regions don’t think men should wear makeup. Then, delve into what makeup do for men. Does it work the same way it does for women? Include products that are made specifically for men.

There’s always something we want to improve regarding our physical appearance. One way to achieve such a goal is through surgeries. However, it’s a dangerous procedure with possible lifetime consequences. List known personalities who were pressured to take surgeries because of society’s idea of beauty but whose lives changed because of failed operations. Then, add your thoughts on having procedures yourself to have a “better” physique.

People like beautiful things. This explains why we are easily fascinated by exquisite artworks. But where do these aspirations come from? What is beauty’s role, and how important is it in a person’s life? Answer these questions in your essay for an engaging piece of writing.

Beauty has many definitions but has two major types. Discuss what is outer and inner beauty and give examples. Tell the reader which of these two types people today prefer to achieve and why. Research data and use opinions to back up your points for an interesting essay.

Many literary pieces and movies are about beauty. Pick one that made an impression on you and tell your readers why. One of the most popular books centered around beauty is Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon , first published in 1993. What does the author want to prove and point out in writing this book, and what did you learn? Are the ideas in the book still relevant to today’s beauty standards? Answer these questions in your next essay for an exiting and engaging piece of writing.

Grammar is critical in writing. To ensure your essay is free of grammatical errors, check out our list of best essay checkers .

The New York Times

Advertisement

The Opinion Pages

January 2, 2013

Does Makeup Hurt Self-Esteem?

Introduction.

Some would argue that makeup empowers women, others would say it’s holding them back from true equality. A recent survey seems to come down on the side of makeup—at least superficially—saying that wearing makeup increases a woman’s likability and competence in the workplace.

If makeup has indeed become the status quo in the public realm, does it ultimately damage a woman’s self-esteem, or elevate it?

Red Lips Can Rule the World

Natasha Scripture, blogger and author

Must This Get Political?

Phoebe Baker Hyde, author, "The Beauty Experiment"

Look Your Best, Feel Your Best

Scott Barnes, makeup artist

A Choice, Not a Requirement

Deborah Rhode, law professor

Using Makeup Shows Love for Yourself

Mally Roncal, makeup artist

It’s What You Make of it

Nancy Etcoff, psychologist and author, "Survival of the Prettiest"

Women Should Do What They Want

Thomas Matlack, The Good Men Project

Recent Discussions

Using makeup doesn't hide women's 'real' beauty, it hides the labor that goes into meeting beauty standards

For all the benefits secured by women who deftly wield a makeup brush or wig or shapewear, there’s a danger that comes with being too good at transforming one’s self into the ideal image of female beauty.

In January 2015, makeup artist Andreigha Wazny posted two photos of her friend Ashley VanPevenage, one showing VanPevenage without makeup, the next showing her with a fully made‑up, high-glamour face. The transformation is stark: VanPevenage’s skin goes from blemished to flawless, her nose appears to change shape, her eyebrows darken and fill out, and her eyes — now framed by dark, smoky eye shadow and lustrous black lashes — seem brighter and more radiant.

To anyone familiar with the transformative power of makeup, there was nothing particularly surprising about these before and after shots. But when they went viral, launching out of the orbit of makeup social media and into the mainstream internet, things took a dark turn.

A few weeks after Wazny posted the photos, a Twitter user reposted them with the caption “The reason why you gotta take a bitch swimming on the first date,” an outing that would presumably wash away a woman’s makeup and reveal her “true” face. (The phrase, it should be noted, did not originate with this user, but seemed to explode in popularity subsequent to this exchange.)

The implication of the phrase, which eventually turned into a meme itself, was clear: Women are trying to deceive men, using the various tricks of the beauty industry to lure unsuspecting paramours into relationships. A man who isn’t careful — who takes the object of his affection at face value, so to speak — can easily wind up saddled to a woman who’s merely faking the attractive exterior that drew him to her in the first place. Women, it’s implied, are inherently deceitful, and those who manage to secure through makeup what they were denied by nature deserve to be revealed.

For women, the world of beauty often presents a difficult, if not outright impossible, situation to navigate. Eschew cosmetics entirely, and you’ll likely be scorned for not caring enough about your appearance; put too much faith in the power of physical transformation, and suddenly you’re a grotesque caricature of vanity as well as a portrait of deceit.

There is, in theory, an optimal amount of effort that deftly balances looking attractive with not caring too much about your appearance, but where that perfect mix is can be pretty hard to pinpoint — and where, exactly, it lies depends a lot on what sort of looks you were born with.

Opinion Bradley Cooper said Lady Gaga's makeup wasn't 'authentic.' Why do men get to decide what's real about us?

“Take a bitch swimming on the first date” may be one of the more vicious male commentaries on female makeup use, but it’s hardly the only one. Men have long declared themselves the arbiters of acceptable application of makeup, and the internet is filled with anti-makeup screeds that use photos to illustrate the argument that women who are unadorned and au naturel look far better than “cakefaces” who bury their skin under layers of product.

Why the animosity toward makeup? Some of it is undoubtedly due to a suspicion that women who wear makeup are trying to hide something (presumably a hideous appearance), but there’s also a vague sense that women who eschew cosmetics are of an entirely different — and more desirable — breed than their bedecked peers. A "Men’s Health" piece offering itself up as “an ode to natural beauty” presents a collection of reasons why bare faces are better; for readers of "Men’s Health" it’s clear that makeup isn’t just makeup.

Opinion Makeup selfies allow those of us deemed unworthy of vanity to document our beauty

According to the experts cited in the piece, going makeup-free makes women seem more confident, more innocent, and more “primal” and sexy (how a lack of makeup simultaneously makes women seem less sexually experienced and more “primal” is a mystery to me), as well as suggesting that they’re outdoorsy, approachable, and down‑to‑earth. The general sentiment — which pervades virtually all arguments against makeup — seems to be that women who eschew beauty culture are more authentic and, as a result, inherently better partners.

Which, I suppose, makes it that much more ironic that the photos chosen to illustrate this celebration of going makeup-free are all stock images secured from Thinkstock — photos that, unsurprisingly, are definitely showcasing women who are wearing makeup. This isn’t just a mistake on the part of "Men’s Health"; it’s a common trait of articles claiming to celebrate going makeup-free.

If anything, men who try to use photos to “prove” they hate makeup are more likely to offer up a demonstration of how little they know about how makeup works and what role it plays in many women’s daily routines. The “makeup-free” women celebrated by men are rarely truly makeup-free; rather, they’re either wearing sparse amounts of carefully applied product or employing the oxymoronic cosmetic strategy known as “natural makeup.”

Opinion Melissa Gilbert: Finally allowing myself to age naturally was one of the best decisions I ever made

For those not steeped in the lingo of fashion magazines, practitioners of the natural makeup look use cosmetics to create a visage perhaps best described as “you, but better.” There’s a great deal of emphasis placed on making the skin look flawless; blush, subtle eye shadow, muted lipstick, and mascara all come into play to help make facial features pop and add depth and definition to features that might not stand out without cosmetic assistance. It’s a look that’s supposed to suggest effortless beauty, but as anyone who’s actually put it into practice can tell you, it often takes more effort than a heavier, obviously made‑up look.

Devoting the better part of an hour to making yourself look as if you’re not wearing makeup at all may seem like a counterproductive task, but for women with acne scars or eye bags or unwanted facial hair, it can be a way to feel pretty without looking overly made‑up. When I ask Baze Mpinja, a former beauty editor for "Glamour," for her thoughts on the look, she offers another possibility for its popularity. Natural makeup, she tells me, allows women to conform to conventional beauty standards without advertising the fact that they’re trying.

“You’re supposed to hide the work that goes into looking pretty,” Mpinja notes. “If you admit how much effort you’re putting in, it begs the question why.” Specifically it suggests that you’re vain or desperate for male attention, undesirable qualities even within a society that teaches women to measure their worth by the amount of attention men give them for their appearances.

But let’s be clear about something: Looking pretty, by American beauty standards, takes a lot of effort — no matter how genetically gifted you may be. Even if you’re blessed with clear skin and an even complexion, thick, healthy hair, long, dark eyelashes a stunning bone structure and enviably pouty lips, to be considered truly beautiful requires adherence to all manner of painful, time-consuming rituals designed to remake the female body into an artificially soft, smooth, and hairless “ideal.”

And if you’re not white, it’s that much harder: The faces and features most readily celebrated in our culture all hew to a Eurocentric beauty standard.

What kind of work goes into being pretty? The first episode of the CW’s "Crazy Ex‑Girlfriend" offers a glimpse into some of the complicated, and at times grotesque, practices that have been normalized by American beauty culture. As Rachel Bloom performs “The Sexy Getting Ready Song,” an R & B tribute to the work women put into physically prepping themselves for a romantic encounter, a variety of ablutions are depicted on-screen. Among those that make an appearance are eyebrow plucking, nose hair plucking, heel buffing, donning Spanx, exfoliating facial skin, curling eyelashes, curling hair, bleaching facial hair, and — in a scene that ends with a shot of blood spattered on the bathroom wall —self-administered waxing of the hair inside her buttocks.

Though the beauty rituals are played for comic effect, they’re very much rooted in reality; indeed, some women’s cosmetic routines are far more punishing than what makes it into the song.

So much about the ideal women are taught to aspire to — the gravity-defying yet ample breasts, the silky smooth skin, the muscular yet buxom body — is an artificial construct, effortlessly available to only a tiny minority of women (if to any of us at all); for the rest of us, achieving the look takes a staggering amount of work. Any woman who’s tried to be pretty knows exactly how much time, effort, and pain are required to adhere to beauty standards.

Opinion Stop telling women they're 'too old' to wear something. It's another way of making us invisible.

Yet even as we all know what goes on behind the scenes, we’re still playing a perverse little game that asks us to obscure the work, to publicly be in denial about the effort it takes to be an attractive woman. (And, to some degree, to obscure the work it takes to be a woman, period. An essay penned by Jessica Leigh Hester for the Atlantic argues that concealer, foundation and other makeup tricks used to make women look less tired are, in effect, preventing the rest of the world from seeing how tiring it is to live in this world as a woman.)

It’s not enough to convincingly present a flawlessly attractive exterior; we must do all that while professing to the world that it was all effortless, and that — to paraphrase Beyoncé — we simply woke up this way.

But to deny the labor that goes into female beauty is to prop up the lie that it’s “natural” to have a body that is anything but, that the aggressive beauty standards we’re judged by are not just acceptable but potentially even fair. When body hair is treated as an invading army to be battled and defeated rather than a simple secondary sex characteristic, the phrase “natural beauty” ceases to have meaning.

We’ve bought into the notion that it’s not merely desirable but downright mandatory to invest time and money and effort into maintaining this charade of what “real women” look like — even as that charade reinforces some of the most noxious aspects of American society.

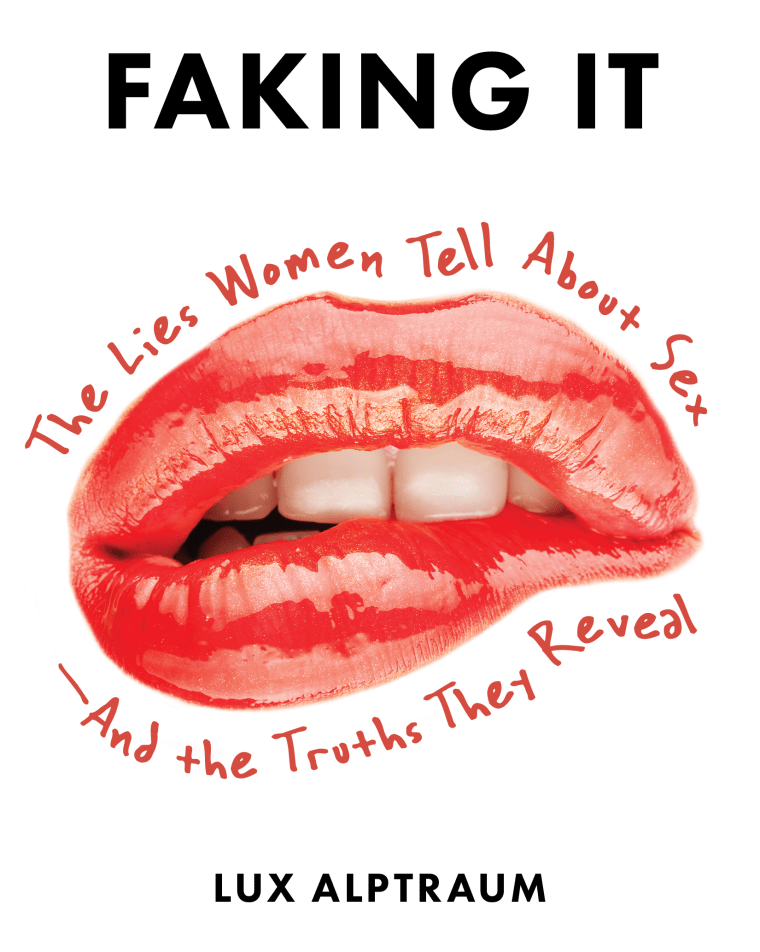

Excerpted from " Faking It: The Lies Women Tell about Sex — And the Truths They Reveal " by Lux Alptraum. Copyright © 2018. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Lux Alptraum is a writer and producer who served as development producer for Fusion’s Peabody-nominated show "Sex.Right.Now.” Her first book, " Faking It: The Lies Women Tell About Sex — And the Truths They Reveal ,” explores our cultural obsession with feminine deceit. She is the co-host of the “ Say You’re Sorry ” podcast.

- Humanities ›

- Writing Essays ›

50 Argumentative Essay Topics

Illustration by Catherine Song. ThoughtCo.

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

An argumentative essay requires you to decide on a topic and argue for or against it. You'll need to back up your viewpoint with well-researched facts and information as well. One of the hardest parts is deciding which topic to write about, but there are plenty of ideas available to get you started. Then you need to take a position, do some research, and present your viewpoint convincingly.

Choosing a Great Argumentative Essay Topic

Students often find that most of their work on these essays is done before they even start writing. This means that it's best if you have a general interest in your subject. Otherwise, you might get bored or frustrated while trying to gather information. You don't need to know everything, though; part of what makes this experience rewarding is learning something new.

It's best if you have a general interest in your subject, but the argument you choose doesn't have to be one that you agree with.

The subject you choose may not necessarily be one you are in full agreement with, either. You may even be asked to write a paper from the opposing point of view. Researching a different viewpoint helps students broaden their perspectives.

Ideas for Argument Essays

Sometimes, the best ideas are sparked by looking at many different options. Explore this list of possible topics and see if a few pique your interest. Write those down as you come across them, then think about each for a few minutes.

Which would you enjoy researching? Do you have a firm position on a particular subject? Is there a point you would like to make sure you get across? Did the topic give you something new to think about? Can you see why someone else may feel differently?

List of 50 Possible Argumentative Essay Topics

A number of these topics are rather controversial—that's the point. In an argumentative essay , opinions matter, and controversy is based on opinions. Just make sure your opinions are backed up by facts in the essay. If these topics are a little too controversial or you don't find the right one for you, try browsing through persuasive essay and speech topics as well.

- Is global climate change caused by humans?

- Is the death penalty effective?

- Is the U.S. election process fair?

- Is torture ever acceptable?

- Should men get paternity leave from work?

- Are school uniforms beneficial?

- Does the U.S. have a fair tax system?

- Do curfews keep teens out of trouble?

- Is cheating out of control?

- Are we too dependent on computers?

- Should animals be used for research?

- Should cigarette smoking be banned?

- Are cell phones dangerous?

- Are law enforcement cameras an invasion of privacy?

- Do we have a throwaway society ?

- Is child behavior better or worse than it was years ago?

- Should companies market to children?

- Should the government have a say in our diets?

- Does access to condoms prevent teen pregnancy?

- Should members of Congress have term limits?

- Are actors and professional athletes paid too much?

- Are CEOs paid too much?

- Should athletes be held to high moral standards?

- Do violent video games cause behavior problems?

- Should creationism be taught in public schools?

- Are beauty pageants exploitative ?

- Should English be the official language of the United States?

- Should the racing industry be forced to use biofuels?

- Should the alcohol-drinking age be increased or decreased?

- Should everyone be required to recycle?

- Is it okay for prisoners to vote (as they are in some states)?

- Should same-sex marriage be legalized in more countries?

- Are there benefits to attending a single-sex school ?

- Does boredom lead to trouble?

- Should schools be in session year-round ?

- Does religion cause war?

- Should the government provide health care?

- Should abortion be illegal?

- Should more companies expand their reproductive health benefits for employees?

- Is homework harmful or helpful?

- Is the cost of college too high?

- Is college admission too competitive?

- Should euthanasia be illegal?

- Should the federal government legalize marijuana use nationally ?

- Should rich people be required to pay more taxes?

- Should schools require foreign language or physical education?

- Is affirmative action fair?

- Is public prayer okay in schools?

- Are schools and teachers responsible for low test scores?

- Is greater gun control a good idea?

How to Craft a Persuasive Argument

After you've decided on your essay topic, gather evidence to make your argument as strong as possible. Your research could even help shape the position your essay ultimately takes. As you craft your essay, remember to utilize persuasive writing techniques , such as invoking emotional language or citing facts from authoritative figures.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- List of Topics for How-to Essays

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Complete List of Transition Words

- 501 Topic Suggestions for Writing Essays and Speeches

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech (With Topic Ideas)

- 67 Causal Essay Topics to Consider

- Practice in Supporting a Topic Sentence with Specific Details

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Topical Organization Essay

- How to Outline and Organize an Essay

- Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Personal Essay Topics

- Ecology Essay Ideas

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Beauty — Why Beauty Matters: Significance of Aesthetic Appreciation

Why Beauty Matters: Significance of Aesthetic Appreciation

- Categories: Beauty Cultural Identity

About this sample

Words: 708 |

Published: Sep 1, 2023

Words: 708 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1372 words

2 pages / 844 words

2 pages / 845 words

5 pages / 2923 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Beauty

Dove. 'Dove Real Beauty Sketches.' YouTube, uploaded by Dove US, 14 April 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=litXW91UauE.Neff, Kristin D. and Elizabeth P. Shoda. 'Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy [...]

Emily Dickinson's poem "I Died for Beauty" talks about big ideas like death, beauty, and truth. Known for her deep and often puzzling poems, Dickinson gives us a thoughtful look at what it means to be human. In this poem, she [...]

Beauty has been a topic of discussion for centuries, with countless opinions on what it truly means to be beautiful. While many perceive beauty as merely a superficial attribute, the true meaning of beauty extends beyond [...]

Beauty is a simple word that has several definitions depending on the individual and the subject at hand. It is an abstract word that is mostly used to describe something that brings happiness or pleases an individual. It may be [...]

"Nail art is an artistic and fun way to decorate nails. It’s an ultimate way to accessorize and beautify you. There are assorted techniques to jazz up your nails with exclusive nail art decor. Even a simple nail art, adds a [...]

We have the concept of "beauty" before a long time ago. However, after all these years, we still have not given out “the one true definition” of the word "beauty". In fact, “beauty” has varied throughout time, various cultures [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved October 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Not only do we use it to make ourselves beautiful, but we use it to express who we are on the outside. By creating advertisements with unrealistic images of what beauty should be, it has resulted in anxiety, low self-esteem, and low self-confidence in many women.

What Is Beauty: An Argumentative Essay. While defining beauty is not easy, it’s a common essay topic. First, share what you think beauty means. Then, explore and gather ideas and facts about the subject and convince your readers by providing evidence to support your argument.

Argumentative Essay About Makeup. Throughout time the world’s perception of makeup has always been seen as a way for women to enhance their facial features, a way to feel more accepted into society, and as a way to gain the attention of another individual.

Some would argue that makeup empowers women, others would say it’s holding them back from true equality. A recent survey seems to come down on the side of makeup—at least superficially—saying...

An essay penned by Jessica Leigh Hester for the Atlantic argues that concealer, foundation and other makeup tricks used to make women look less tired are, in effect, preventing the rest of the...

An argumentative essay requires you to decide on a topic and argue for or against it. You'll need to back up your viewpoint with well-researched facts and information as well. One of the hardest parts is deciding which topic to write about, but there are plenty of ideas available to get you started.

This essay delves into the multifaceted dimensions of beauty, examining its relevance across cultural contexts, its role in shaping human perception, and the ways in which the appreciation of beauty contributes to our well-being and sense of connection.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement. The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it. Argumentative essays are by far the most common type of essay to write at university.

I strongly believe completely opposite of the stereotype for makeup, “you're not confident, so you cover your face”, or people are fake or plastic. Suddenly we become liars when we look different without makeup, because we are born with red lips and gold eyelids right?.

For example, just to name a few, arguments advocating makeup use range from enhancing beauty to boosting self-esteem to challenging heteronormativity; whereas, arguments denouncing makeup range from health concerns to workplace inequality to emotional self-esteem.