- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

Farnam Street

Mastering the best of what other people have already figured out

This is Water by David Foster Wallace (Full Transcript and Audio)

David Foster Wallace ‘s 2005 commencement speech to the graduating class at Kenyon College is a timeless trove of wisdom — right up there with Hunter Thompson on finding your purpose . The speech was made into a thin book titled This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life .

Wallace hits on our need to manage rather than remove our core hard-wired human instincts.

Here are the links to the original audio, followed by a transcript of the entire speech.

This is Water

Transcript:

Greetings parents and congratulations to Kenyon’s graduating class of 2005. There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

This is a standard requirement of US commencement speeches, the deployment of didactic little parable-ish stories. The story thing turns out to be one of the better, less bullshitty conventions of the genre, but if you’re worried that I plan to present myself here as the wise, older fish explaining what water is to you younger fish, please don’t be. I am not the wise old fish. The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude, but the fact is that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance, or so I wish to suggest to you on this dry and lovely morning.

Of course the main requirement of speeches like this is that I’m supposed to talk about your liberal arts education’s meaning, to try to explain why the degree you are about to receive has actual human value instead of just a material payoff. So let’s talk about the single most pervasive cliché in the commencement speech genre, which is that a liberal arts education is not so much about filling you up with knowledge as it is about “teaching you how to think.” If you’re like me as a student, you’ve never liked hearing this, and you tend to feel a bit insulted by the claim that you needed anybody to teach you how to think, since the fact that you even got admitted to a college this good seems like proof that you already know how to think. But I’m going to posit to you that the liberal arts cliché turns out not to be insulting at all, because the really significant education in thinking that we’re supposed to get in a place like this isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about. If your total freedom of choice regarding what to think about seems too obvious to waste time discussing, I’d ask you to think about fish and water, and to bracket for just a few minutes your scepticism about the value of the totally obvious.

Here’s another didactic little story. There are these two guys sitting together in a bar in the remote Alaskan wilderness. One of the guys is religious, the other is an atheist, and the two are arguing about the existence of God with that special intensity that comes after about the fourth beer. And the atheist says: “Look, it’s not like I don’t have actual reasons for not believing in God. It’s not like I haven’t ever experimented with the whole God and prayer thing. Just last month I got caught away from the camp in that terrible blizzard, and I was totally lost and I couldn’t see a thing, and it was 50 below, and so I tried it: I fell to my knees in the snow and cried out ‘Oh, God, if there is a God, I’m lost in this blizzard, and I’m gonna die if you don’t help me.’” And now, in the bar, the religious guy looks at the atheist all puzzled. “Well then you must believe now,” he says, “After all, here you are, alive.” The atheist just rolls his eyes. “No, man, all that was was a couple Eskimos happened to come wandering by and showed me the way back to camp.”

It’s easy to run this story through kind of a standard liberal arts analysis: the exact same experience can mean two totally different things to two different people, given those people’s two different belief templates and two different ways of constructing meaning from experience. Because we prize tolerance and diversity of belief, nowhere in our liberal arts analysis do we want to claim that one guy’s interpretation is true and the other guy’s is false or bad. Which is fine, except we also never end up talking about just where these individual templates and beliefs come from. Meaning, where they come from INSIDE the two guys. As if a person’s most basic orientation toward the world, and the meaning of his experience were somehow just hard-wired, like height or shoe-size; or automatically absorbed from the culture, like language. As if how we construct meaning were not actually a matter of personal, intentional choice. Plus, there’s the whole matter of arrogance. The nonreligious guy is so totally certain in his dismissal of the possibility that the passing Eskimos had anything to do with his prayer for help. True, there are plenty of religious people who seem arrogant and certain of their own interpretations, too. They’re probably even more repulsive than atheists, at least to most of us. But religious dogmatists’ problem is exactly the same as the story’s unbeliever: blind certainty, a close-mindedness that amounts to an imprisonment so total that the prisoner doesn’t even know he’s locked up.

The point here is that I think this is one part of what teaching me how to think is really supposed to mean. To be just a little less arrogant. To have just a little critical awareness about myself and my certainties. Because a huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded. I have learned this the hard way, as I predict you graduates will, too.

Here is just one example of the total wrongness of something I tend to be automatically sure of: everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe; the realest, most vivid and important person in existence. We rarely think about this sort of natural, basic self-centredness because it’s so socially repulsive. But it’s pretty much the same for all of us. It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth. Think about it: there is no experience you have had that you are not the absolute centre of. The world as you experience it is there in front of YOU or behind YOU, to the left or right of YOU, on YOUR TV or YOUR monitor. And so on. Other people’s thoughts and feelings have to be communicated to you somehow, but your own are so immediate, urgent, real.

Please don’t worry that I’m getting ready to lecture you about compassion or other-directedness or all the so-called virtues. This is not a matter of virtue. It’s a matter of my choosing to do the work of somehow altering or getting free of my natural, hard-wired default setting which is to be deeply and literally self-centered and to see and interpret everything through this lens of self. People who can adjust their natural default setting this way are often described as being “well-adjusted”, which I suggest to you is not an accidental term.

Given the triumphant academic setting here, an obvious question is how much of this work of adjusting our default setting involves actual knowledge or intellect. This question gets very tricky. Probably the most dangerous thing about an academic education–least in my own case–is that it enables my tendency to over-intellectualise stuff, to get lost in abstract argument inside my head, instead of simply paying attention to what is going on right in front of me, paying attention to what is going on inside me.

As I’m sure you guys know by now, it is extremely difficult to stay alert and attentive, instead of getting hypnotised by the constant monologue inside your own head (may be happening right now). Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal arts cliché about teaching you how to think is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed. Think of the old cliché about “the mind being an excellent servant but a terrible master.”

This, like many clichés, so lame and unexciting on the surface, actually expresses a great and terrible truth. It is not the least bit coincidental that adults who commit suicide with firearms almost always shoot themselves in: the head. They shoot the terrible master. And the truth is that most of these suicides are actually dead long before they pull the trigger.

And I submit that this is what the real, no bullshit value of your liberal arts education is supposed to be about: how to keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone day in and day out. That may sound like hyperbole, or abstract nonsense. Let’s get concrete. The plain fact is that you graduating seniors do not yet have any clue what “day in day out” really means. There happen to be whole, large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches. One such part involves boredom, routine and petty frustration. The parents and older folks here will know all too well what I’m talking about.

By way of example, let’s say it’s an average adult day, and you get up in the morning, go to your challenging, white-collar, college-graduate job, and you work hard for eight or ten hours, and at the end of the day you’re tired and somewhat stressed and all you want is to go home and have a good supper and maybe unwind for an hour, and then hit the sack early because, of course, you have to get up the next day and do it all again. But then you remember there’s no food at home. You haven’t had time to shop this week because of your challenging job, and so now after work you have to get in your car and drive to the supermarket. It’s the end of the work day and the traffic is apt to be: very bad. So getting to the store takes way longer than it should, and when you finally get there, the supermarket is very crowded, because of course it’s the time of day when all the other people with jobs also try to squeeze in some grocery shopping. And the store is hideously lit and infused with soul-killing muzak or corporate pop and it’s pretty much the last place you want to be but you can’t just get in and quickly out; you have to wander all over the huge, over-lit store’s confusing aisles to find the stuff you want and you have to manoeuvre your junky cart through all these other tired, hurried people with carts (et cetera, et cetera, cutting stuff out because this is a long ceremony) and eventually you get all your supper supplies, except now it turns out there aren’t enough check-out lanes open even though it’s the end-of-the-day rush. So the checkout line is incredibly long, which is stupid and infuriating. But you can’t take your frustration out on the frantic lady working the register, who is overworked at a job whose daily tedium and meaninglessness surpasses the imagination of any of us here at a prestigious college.

But anyway, you finally get to the checkout line’s front, and you pay for your food, and you get told to “Have a nice day” in a voice that is the absolute voice of death. Then you have to take your creepy, flimsy, plastic bags of groceries in your cart with the one crazy wheel that pulls maddeningly to the left, all the way out through the crowded, bumpy, littery parking lot, and then you have to drive all the way home through slow, heavy, SUV-intensive, rush-hour traffic, et cetera et cetera.

Everyone here has done this, of course. But it hasn’t yet been part of you graduates’ actual life routine, day after week after month after year.

But it will be. And many more dreary, annoying, seemingly meaningless routines besides. But that is not the point. The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of choosing is gonna come in. Because the traffic jams and crowded aisles and long checkout lines give me time to think, and if I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m gonna be pissed and miserable every time I have to shop. Because my natural default setting is the certainty that situations like this are really all about me. About MY hungriness and MY fatigue and MY desire to just get home, and it’s going to seem for all the world like everybody else is just in my way. And who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are, and how stupid and cow-like and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line. And look at how deeply and personally unfair this is.

Or, of course, if I’m in a more socially conscious liberal arts form of my default setting, I can spend time in the end-of-the-day traffic being disgusted about all the huge, stupid, lane-blocking SUV’s and Hummers and V-12 pickup trucks, burning their wasteful, selfish, 40-gallon tanks of gas, and I can dwell on the fact that the patriotic or religious bumper-stickers always seem to be on the biggest, most disgustingly selfish vehicles, driven by the ugliest [responding here to loud applause] — this is an example of how NOT to think, though — most disgustingly selfish vehicles, driven by the ugliest, most inconsiderate and aggressive drivers. And I can think about how our children’s children will despise us for wasting all the future’s fuel, and probably screwing up the climate, and how spoiled and stupid and selfish and disgusting we all are, and how modern consumer society just sucks, and so forth and so on.

You get the idea.

If I choose to think this way in a store and on the freeway, fine. Lots of us do. Except thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic that it doesn’t have to be a choice. It is my natural default setting. It’s the automatic way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the centre of the world, and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.

The thing is that, of course, there are totally different ways to think about these kinds of situations. In this traffic, all these vehicles stopped and idling in my way, it’s not impossible that some of these people in SUV’s have been in horrible auto accidents in the past, and now find driving so terrifying that their therapist has all but ordered them to get a huge, heavy SUV so they can feel safe enough to drive. Or that the Hummer that just cut me off is maybe being driven by a father whose little child is hurt or sick in the seat next to him, and he’s trying to get this kid to the hospital, and he’s in a bigger, more legitimate hurry than I am: it is actually I who am in HIS way.

Or I can choose to force myself to consider the likelihood that everyone else in the supermarket’s checkout line is just as bored and frustrated as I am, and that some of these people probably have harder, more tedious and painful lives than I do.

Again, please don’t think that I’m giving you moral advice, or that I’m saying you are supposed to think this way, or that anyone expects you to just automatically do it. Because it’s hard. It takes will and effort, and if you are like me, some days you won’t be able to do it, or you just flat out won’t want to.

But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she’s not usually like this. Maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider. If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

Not that that mystical stuff is necessarily true. The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re gonna try to see it.

This, I submit, is the freedom of a real education, of learning how to be well-adjusted. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.

Because here’s something else that’s weird but true: in the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship–be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles–is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It’s been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness.

Worship power, you will end up feeling weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to numb you to your own fear. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart, you will end up feeling stupid, a fraud, always on the verge of being found out. But the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful, it’s that they’re unconscious. They are default settings.

They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.

And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the centre of all creation. This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But of course there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talk about much in the great outside world of wanting and achieving…. The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.

I know that this stuff probably doesn’t sound fun and breezy or grandly inspirational the way a commencement speech is supposed to sound. What it is, as far as I can see, is the capital-T Truth, with a whole lot of rhetorical niceties stripped away. You are, of course, free to think of it whatever you wish. But please don’t just dismiss it as just some finger-wagging Dr Laura sermon. None of this stuff is really about morality or religion or dogma or big fancy questions of life after death.

The capital-T Truth is about life BEFORE death.

It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

“This is water.”

It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out. Which means yet another grand cliché turns out to be true: your education really IS the job of a lifetime. And it commences: now.

I wish you way more than luck.

This is Water makes a great gift .

Still Curious? David Foster Wallace is the author of Infinite Jest , A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again , Consider the Lobster (a phenomenal book of essays), and the unfinished book he was writing when he committed suicide: The Pale King .

“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Freedom in decision making, meaning and importance of education, the lesson on default setting, works cited.

David Wallace was one of the most important postmodern authors in America. He had already gained attention with his first book, “The Broom of the System.” Still, his second novel, “Infinite Jest,” catapulted him to national prominence and made him one of the most respected authors of the modern American era. ‘This is water,’ his book, was essentially an expanded version of Wallace’s commencement speech to a group of graduating students. Unlike other books, which were panned for being overly long for their own sake, this commencement speech was generally praised, and even named one of the top 10 best commencement speeches in history by ‘Time’ magazine.

In his speech ‘This is water,’ Wallace’s goal was to stress the importance of perceptiveness, and awareness of others. He felt that through combining awareness, and education, people would become well-adjusted to their surroundings. To achieve his argumentative goal for his audience, he used a personal, and comic tone. This essay will focus on giving a summary of David Wallace’s ‘The Water’.

After greeting and praising the students for their hard work, Wallace opened his address with a remarkable parable based on a fish story. The significance of the fish story, he continued, was simply that the most significant realities were frequently the most difficult to see, and discuss. In other words, people were living in water but could not see, and were completely oblivious of its presence. On the other hand, Wallace felt that most people were mistaken and that it was the mission of liberal arts education to tell them they were wrong

Liberal arts education was designed to make people aware of the water in their surroundings rather than filling their heads with unimportant information. Wallace’s main point in his speech was that often the most obvious things were the most difficult to comprehend. He stated, in particular, that negative thinking was not a choice but a natural setting, and that individuals needed to start thinking cognitively, and beyond the box.

Wallace delivered his commencement address to Kenyon College’s 2005 graduating class intending to prepare the students for the future life they were about to embark on after college. He used a grocery store example in his speech so that the students could relate since they had been in the situation. Wallace was also able to connect with his audience by using this grocery example. He further highlighted that, while individuals believed they were trapped in a ‘rat race, they had the option of choosing between two options: looking at the situation negatively and getting a bad result, or looking at it positively and feeling better about the situation.

Wallace exemplified this point by stating that the inability to make a conscious decision about what to pay attention to would irritate them every time they went shopping. He also noted that many people were narrow-minded, and loved evaluating others. However, each possessed the capacity to change a situation by making it cheerful and hopeful.

In his address ‘This is Water,’ David Foster Wallace reminded Kenyon students that education was more than a piece of paper, and did not merely comprise learning. Wallace defined education as being conscious and aware enough to generate meaning from experience. Proper education also taught people to be less arrogant and to have even a little bit of uncertainty about themselves and their convictions. Because a large percentage of people’s actions turned out to be incorrect, education was meant to put this error into words that would be alive, and conscious giving meaning to the ultimately unfulfilling, and dull lives that practically everyone was bound to mention. He also observed that speakers rarely talked about these lives in commencement speeches.

Wallace explained the entailment of a typical adult’s day, emphasizing that an average adult’s day was in no way comparable to the ones promised in entrepreneur manuals and self-help books. On the other hand, an ordinary adult day consisted of people getting up in the morning, going to their college-graduate white-collar jobs, resting afterward, and waiting for the next day (Neveu, 161). Due to their hectic schedules, they would even lack time to make themselves lunch.

However, despite the after-work fatigue, and lack of time, they always had a choice: they could either believe it was all about them and thus blame everyone. On the other hand, they could recognize that they were just a drop of water in the ocean and that everyone was dealing with a similar or the same issue.

Wallace claimed in his speech that people’s character was defined by the modest decisions they made every day in their everyday struggles. It was clear from his knowledgeable words that he explained everything from a distinct and, interesting perspective. David Foster Wallace also proposed a hypothesis in which all humans behaved on the simple premise that they were the center of the universe and that every decision they made was motivated by their desires. He claimed that people’s “default setting” was responsible for robbing them of their ability to see situations as they were (Severs, 303). In addition, he emphasized the importance of the audience combating their natural selfishness, and the constant belief that their own identity, triumphs, and failures were the most important things to them.

Wallace observed that the majority of people operated on the automatic setting. As a result, many individuals lived like robots programmed to feel through instruction and not willing, or like fish unconscious of the surrounding seas using Wallace’s metaphor. In his speech, he argued that the most crucial type of freedom entailed knowledge, discipline, concentration, and the ability to care about other people and sacrifice for them sincerely. He saw these constituents of freedom as true liberties that required education and knowledge from other points of view. However, the persistent gnawing sense of having had and lost some endless thing was the alternative to this type of freedom.

In conclusion, ‘This is Water’ emphasized the importance of exhibiting compassion and empathy for others. Wallace stated that it was essential for people to see life, and everything around them from many perspectives, irrespective of the scenario. He insisted that the audience make their lives more meaningful, beneficial, and experienced by demonstrating compassion and being mindful of others. Waiting in a severe traffic jam after a long day at work would be aggravating for most people. However, Wallace believed it was vital for such situations in life so that people could understand that life did not always revolve around them.

Also, there were significant, and more considerable reasons for the occurrence of these events. As a result, it was critical for the audience to maintain the perspective that others could be in worse conditions than themselves, and that they were not always superior to others.

Neveu, Marc J. “How’s the Water?” Journal of Architectural Education , vol. 74, no. 2, 2020, pp. 161-161.

Severs, J. “Cutting consciousness down to size: David Foster Wallace, Exformation, and the scale of encyclopedic fiction.” Scale in Literature and Culture , 2017, pp. 281-303. Web.

- Novel Analysis: The Great Gatsby and Siddhartha

- Redemption in Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner”

- Modernist Poetry: Wallace Stevens and T.S. Elliot

- Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own vs. Wallace’s A Simple Poem for Virginia Woolf

- Religion in American Poetry

- "Patron Saints of Nothing" Novel Analysis

- Tessie Hutchinson’s Character From “The Lottery” Analysis

- “Seven Fallen Feathers”: Injustice and Morality

- Psychic Effects of Detached Family and Social Relations

- Fitzgerald’s “Hero” in “Tender Is the Night”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 25). “This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace. https://ivypanda.com/essays/this-is-water-by-david-foster-wallace/

"“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace." IvyPanda , 25 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/this-is-water-by-david-foster-wallace/.

IvyPanda . (2022) '“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace'. 25 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/this-is-water-by-david-foster-wallace/.

1. IvyPanda . "“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/this-is-water-by-david-foster-wallace/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "“This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/this-is-water-by-david-foster-wallace/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Skip to content

- Skip to footer

| The Art of Living for Students of Life

3 Profound Life Lessons from “This is Water” by David Foster Wallace

By Kyle Kowalski · 23 Comments

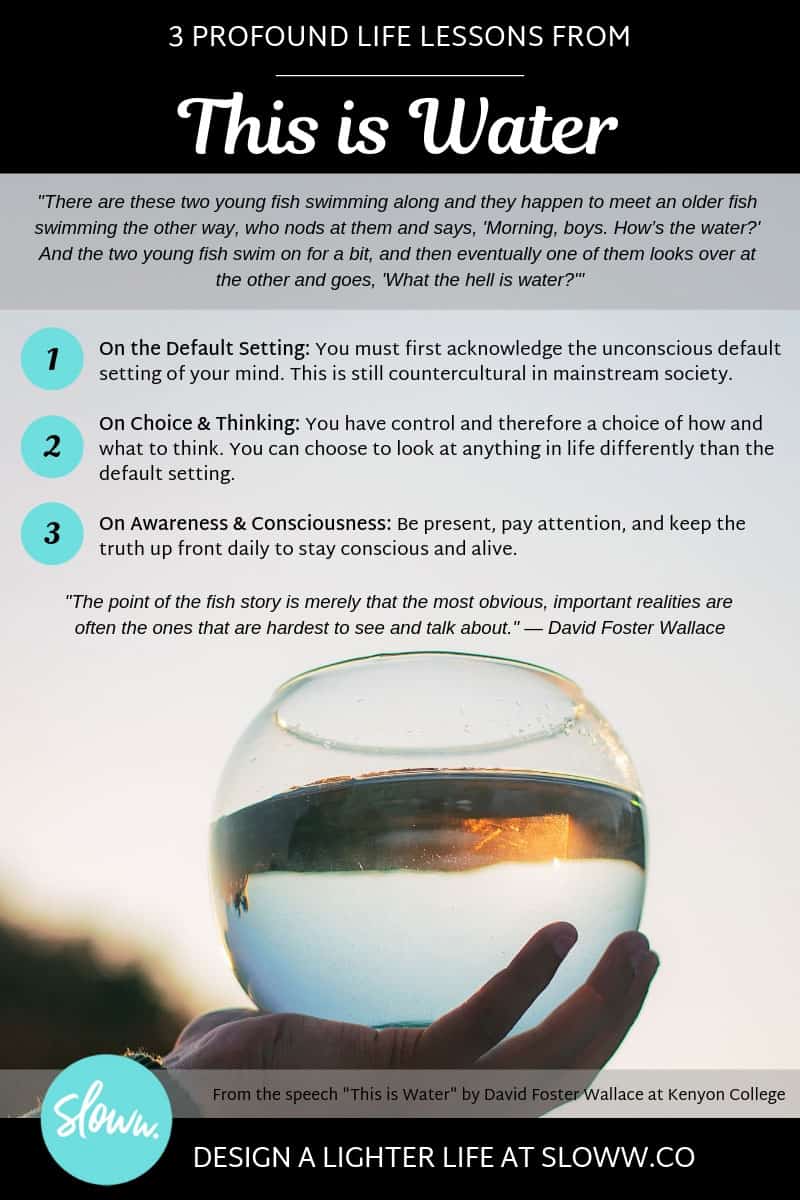

In 2005, David Foster Wallace delivered the “This is Water” commencement speech at Kenyon College. I’ve studied and written about the most viewed commencement speeches in the past, but this one is special.

In just over 20 minutes, he covers the “unsexy” yet very real realities of day-to-day adult life. The graduating audience appears to laugh at various times in the speech, but I don’t think David Foster Wallace intended for any of it to be humorous. He’s calling out the “default setting” of the unconscious human minds that are all too common in mainstream society. The state of your own mind will determine how you live in the “day in and day out” and “day-to-day trenches of adult existence.”

While he pokes fun at “didactic little parable-ish stories” in commencement speeches, David Foster Wallace delivers one of the best. This post outlines my own personal interpretation of his speech.

If you’re interested, you can listen to the full speech here:

The Purpose of This is Water by David Foster Wallace

The Purpose of the Fish Story:

- “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’ “

- “If your total freedom of choice regarding what to think about seems too obvious to waste time discussing, I’d ask you to think about fish and water, and to bracket for just a few minutes your skepticism about the value of the totally obvious.”

- “ The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness ; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: ‘This is water.’ ‘This is water.’ “

3 Profound Life Lessons from This is Water by David Foster Wallace

- “And I submit that this is what the real, no bullshit value of your liberal arts education is supposed to be about: how to keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone day in and day out.”

- “If I choose to think this way in a store and on the freeway, fine. Lots of us do. Except thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic that it doesn’t have to be a choice. It is my natural default setting. It’s the automatic way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the centre of the world, and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.”

- “If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough.” (Note: See my own experience with lifestyle inflation .)

- “And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self.”

- “The really significant education in thinking that we’re supposed to get in a place like this isn’t really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about.”

- “The point is that petty, frustrating crap like this is exactly where the work of choosing is gonna come in.”

- “If I don’t make a conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to, I’m gonna be pissed and miserable every time I have to shop.”

- “Most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice , you can choose to look differently.”

- “The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re gonna try to see it.”

- “You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t.”

- “Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal arts cliché about teaching you how to think is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed.”

- “Probably the most dangerous thing about an academic education—least in my own case—is that it enables my tendency to over-intellectualize stuff, to get lost in abstract argument inside my head, instead of simply paying attention to what is going on right in front of me, paying attention to what is going on inside me.”

- “If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.”

- “The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness .”

- “It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out.”

How are you doing on these three life lessons? Do you acknowledge your default setting? Are you exercising control and choice over your mind? How about paying attention and staying present?

- “The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day. That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.”

About Kyle Kowalski

👋 Hi, I'm Kyle―the human behind Sloww . I'm an ex-marketing executive turned self-education entrepreneur after an existential crisis in 2015. In one sentence: my purpose is synthesizing lifelong learning that catalyzes deeper development . But, I’m not a professor, philosopher, psychologist, sociologist, anthropologist, scientist, mystic, or guru. I’m an interconnector across all those humans and many more—an "independent, inquiring, interdisciplinary integrator" (in other words, it's just me over here, asking questions, crossing disciplines, and making connections). To keep it simple, you can just call me a "synthesizer." Sloww shares the art of living with students of life . Read my story.

Sloww participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. When you purchase a book through an Amazon link, Sloww earns a small percentage at no additional cost to you. This helps fund the costs to support the site and the ad-free experience.

Reader Interactions

February 13, 2019 at 10:54 PM

February 14, 2019 at 12:16 AM

You’re welcome, Mark!

July 17, 2019 at 2:41 PM

I know, this is old. I’ve just happened upon this because some one recommend this speech to me. Frankly, I hated it and DFW came across as a psychopath and an unaware narcissist. And I’ve read and reread through the transcript and I can’t see what the big deal is. I don’t know what was suppose to be so deep or moving. I’m assuming I’m wrong or missed something. Anyone care to enlighten me? I know no one will see this but I hit the web in a fit of anger and wound up here.

July 17, 2019 at 3:48 PM

“The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” Just like the fish are in water without realizing it, we are in the default setting of our minds without realizing it. We have a choice of how and what to think. In other words, we can shift from the default setting to conscious awareness.

January 23, 2020 at 8:47 PM

This was a really good, quick summary and analysis of the speech. Thanks for taking the time to do all this!

January 30, 2020 at 11:58 AM

Of course, Trent!

June 16, 2020 at 3:18 AM

Kyle. That really is an excellent summary. This essay and Hunter S Thompson’s letter to a friend are two of my absolute favourites. Keep well and thanks for writing this piece

August 6, 2020 at 12:05 AM

Appreciate it, Chris! I’ll check out the Hunter S. Thompson essay.

September 28, 2019 at 11:19 PM

Be less certain.

October 7, 2019 at 1:13 PM

You got it, Joe!

November 21, 2019 at 5:52 PM

Awesome analysis Kyle.

December 16, 2019 at 11:57 PM

I appreciate it, Jake.

January 6, 2020 at 2:57 PM

Thank you sir

January 14, 2020 at 9:40 AM

Sure thing (love your username, by the way :))

January 27, 2020 at 7:09 PM

I didn’t realise how potent the message was when I was first listened to ‘This is Water’ 6 months ago. It’s saved my life a couple of times over the last few months whilst I’ve been experiencing an existential crisis. Crazy what a shift of consciousness can mean to your understanding of the world, and your part in it. Thank you so much for this and for your blog.

January 30, 2020 at 11:33 AM

Of course, Yvie! I also revisited this speech just the other day. I think it will always be relevant because it’s so applicable to day-to-day reality. If you haven’t already, be sure to check out my own existential crisis story (along with the comments of many others experiencing their own crises today).

June 22, 2020 at 7:17 PM

I was introduced to this speech by my professor at University, and have listened and shared this speech numerous times. This speech promotes the need for empathy in our society.

August 5, 2020 at 12:22 AM

Keep sharing the good word, Jasprit!

June 9, 2023 at 12:57 AM

This is a helpful summary, Kyle! This speech is actually an eye opener and truly inspirational.

November 26, 2020 at 5:17 PM

I’m doing an English assignment on this speech, and this site helped me understand it better

February 6, 2022 at 3:11 PM

What is the English assignment?

March 2, 2022 at 11:01 PM

I am supposed to write an essay of my analysis of this speech. I just cannot figure out a way to explain the repeating phrase at the end “this is water”… It would be great if anyone can help!

July 25, 2022 at 11:05 AM

Hi Julie, I thought I would take a shot at answering your question, not in a definitive way but just in a way that came to me as I went back to the talk and listened to the end again.

What spoke to me was the part just before “this is water” which was “we need to keep reminding ourselves”. It is likely that your need for this essay is long past and you figured out a response for yourself since you wrote that in March, and here it is toward the end of July. But if I might paraphrase the ending it would be, “keep reminding ourselves that this, whatever this is that is happening in front of me and to me, is the only reality I can count on.”

My story, my take away, my lessons learned will all come from this and may or may not be true accurate or helpful, but yes, whatever this is, and in the message he presented it was “water to the fish“ is the same thing as whatever is happening to us as humans. I don’t know if this helps you but it helped me to think through this and I appreciate your question.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Popular Posts

Join the sloww movement.

📧 10,000+ lifelong learners read the Sloww Sunday newsletter (+ free eBook "The Hierarchy of Happiness"):

🆕 Synthesizer Course

🔒 Sloww Premium

Sloww Social

Find anything you save across the site in your account

This Is Water

In 2005, David Foster Wallace addressed the graduating class at Kenyon College with a speech that is now one of his most read pieces. In it, he argues, gorgeously, against “unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.” He begins with a parable:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

When Wallace died, on September 12th, the water churned. Fittingly for a writer whose work encircled itself with annotations, he will leave a legacy composed not only of his novels and essays, and of pieces written about him—official obituaries, elegies, and scholarly papers—but also of a vast and growing system of Web sites, e-mails, message boards, and blogs—and comments on those blogs, and comments on those comments, ad infinitum. His life has a lot of footnotes:

- A professor at Amherst remembers Wallace, who babysat his kids, and the writer’s virtuosic senior year at the college.

- John Seery, Wallace’s colleague and workout buddy, reveals that Wallace once thanked him for accompanying him to a party otherwise full of gym rats, whom he was afraid might force him to do their algebra homework.

- Wallace, from a 1999 interview with Amherst magazine: “I fluctuate between periods of terrible sloth and paralysis and periods of high energy and production, but from what I know about other writers this isn’t unusual.”

- An ever-growing accumulation of first-person homages on McSweeney’s , including the simple statement “He helped me to stop wrecking my life, showed me how to help other people and why I should bother."

- Pomona students recall their professor, both in the classroom and on the tennis court: “He had a complete game, the kind that comes from years of obsessing over stroke technique and ball location. If there was one sign that he was more than an above-par recreational player, it was the fact that he would employ a relatively advanced tactic, what tennis geeks call ‘taking the ball off the rise.’ It requires sharp reflexes and timing. He did it repeatedly that summer afternoon in 2005."

- A series of responses on Metafilter that accumulate like a snowball rolling down a hill. One of the more recent: “I have felt really alive lately, really engaged in my life to a degree that I hadn’t been for a few years, but this was like a punch in the gut. And the head. And the heart.” The post comes with footnotes.

- Among the best of Wallace’s fellow-writers’ recollections is Ben Kunkel’s, in n+1 : “The real grief is in the death of a great artist and a kind man.”

- A skeleton key .

- “The Howling Fantods,” a fan site, memorializes, compiles, and understates : “To say that David Foster Wallace has had a profound influence on my life, the way I think, and the way in which I perceive the world, is an understatement.” (Elsewhere on the site, among numerous links, are Wallace’s uncollected writings.)

- All Wallace listserv e-mails from September.

- A syllabus from Wallace’s Literary Interpretation class, from 2005.

- Wallace speaks .

All of this is, no doubt, just the tip of the iceberg, peeking out of the sea. At Kenyon, Wallace elaborated on his water parable:

The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about....The fact is that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance.

And, nearing the end of his speech:

The capital-T Truth is about life BEFORE death. It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

This is water.

This is Water David Foster Wallace Summary

Summary & analysis of this is water by david foster wallace.

David Foster Wallace, a renowned literary figure, delivered a commencement speech titled “This Is Water: Some Thoughts Delivered on a Significant Occasion, About Living a Compassionate Life” at Kenyon College on May 21, 2005. The speech was later published in The Best American Nonrequired Reading in 2006. The speech emphasizes the importance of developing a conscious awareness of one’s thoughts and choosing how to perceive and respond to the world around us. It encourages listeners to consider the impact of their perspectives and assumptions on their daily lives.

This is Water | Summary

Beginning his speech with a clichéd parable from Infinite Jest that serves as a metaphor for the invisible forces that shape our lives and how we often fail to recognize them, David Foster Wallace challenges the conventional expectations placed on commencement speakers and explores the idea that certain clichés and overused stories can still convey profound truths . Unlike the wise old fish in his analogy, Wallace does not claim to possess a profound philosophical understanding of the “water” of life. Instead, he focuses on the lessons embedded within these well-worn narratives. He asserts that the most significant and fundamental realities are often the most difficult to articulate.

Wallace deconstructs common speech topics, such as the value of a liberal arts education in terms of its “human value” and the development of critical thinking skills rather than the accumulation of knowledge. While he found these ideas tiresome as a student, he acknowledges that there is wisdom to be found within clichés. He emphasizes that what truly matters is not how students think, but rather what they choose to direct their thoughts towards. Despite the seemingly obvious freedom to think about anything, Wallace encourages his audience to pay attention to the seemingly mundane and commonplace aspects of life.

Wallace shares another story that highlights the paradox of personal interpretation , emphasizing that the same experience can hold entirely different meanings for different individuals. He suggests that this concept is readily accepted from a liberal arts perspective, which promotes tolerance and diversity by avoiding categorizing anyone as definitively right or wrong. However, Wallace challenges this notion by proposing a different approach: he suggests that it is more productive to investigate an individual’s beliefs by recognizing them as an agent with free will, rather than as a predetermined object. He goes on to provide examples such as intentional choice, arrogance, and blind certainty as ways in which people shape and confine their own beliefs.

According to Wallace, true freedom comes from making conscious choices about how to perceive and respond to the world. He acknowledges that this kind of awareness is difficult to maintain consistently, as our natural tendency is to default back to our self-centered thinking. However, he argues that with practice and effort, we can train our minds to recognize our own biases, assumptions, and automatic reactions, enabling us to choose alternative perspectives and live more fulfilling lives.

This is Water | Analysis

David Foster Wallace revisits the topic of liberal arts education and provides further insight by suggesting that it is not “really about the capacity to think, but rather about the choice of what to think about” , about equipping students with the ability to exert control over their thoughts and choices. He emphasizes that the essence of a liberal arts education lies in developing awareness, cultivating attention, and actively constructing meaning in one’s life. Wallace cautions against allowing the mind to become a dominant force, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a sense of agency and control over our thoughts and actions. Wallace draws attention to the challenges and realities of adult life in America, such as the pressures, monotony, and frustrations that young students may not yet be intimately familiar with. He suggests that if individuals are not equipped with the necessary tools to navigate these aspects of life, it can lead to a sense of meaninglessness or even self-destructive behaviors.

“The exact same experience can mean two totally different things to two different people” .

Furthermore, Wallace critically examines the societal expectations and clichés surrounding commencement speeches. He challenges the conventional wisdom about the value of a liberal arts education and calls for a deeper examination of personal beliefs and choices. By highlighting the dangers of conformity and blind certainty, he encourages individuals to embrace intellectual curiosity and actively engage with different perspectives.

Despite these critiques, “This Is Water” remains widely regarded for its ability to provoke introspection and challenge deeply ingrained patterns of thought. It invites individuals to reconsider their assumptions, cultivate empathy, and strive for a more compassionate and mindful approach to living.

A Buddhist undercurrent runs through “This Is Water,” as Wallace urges the graduates to cultivate awareness, observe their surroundings, and transcend their ignorance about the true nature of life. In this regard, the speech aligns with Buddhist teachings that emphasize mindfulness and awakening. The speech also incorporates elements of perspectivism, a theory associated with Friedrich Nietzsche, which asserts that knowledge is inherently limited by an individual’s point of view and interpretation. Wallace’s use of various philosophical sources, including Nietzsche, underscores the importance of recognizing the subjective nature of our understanding and the need to embrace multiple perspectives. Drawing from these philosophical influences, Wallace highlights the presence of profound truths that often remain hidden in plain sight. He employs self-effacing statements, such as “please don’t think I’m giving you moral advice,” to bridge the gap between the speaker and the audience, inviting them to participate in the shared exploration of these truths.

This is Water | Rhetorical Analysis

Wallace utilizes repetition for emphasis and to reinforce key ideas throughout the speech. For example, he repeats the phrase “This is water” as a reminder of the pervasive and often overlooked realities of daily life.

The speech often employs contrasting ideas and antithesis to highlight opposing viewpoints and emphasize the importance of conscious awareness. Wallace juxtaposes automatic, self-centered thinking with intentional, empathetic thinking, emphasizing the choices we have in shaping our experiences.

An Abduction Short Story Summary

Summary of the storm by kate chopin, related articles, the steadfast tin soldier summary, teenage wasteland | summary & analysis, the trouble with snowmen | summary and analysis, the day the crayons quit summary, leave a reply cancel reply, adblock detected.

S Y N A P S I S

a health humanities journal

Nitya Rajeshuni

Nitya Rajeshuni //

I don’t understand why wrinkles are blasphemous. I examined her face framed by wisps of smoky hair, captivated by the zigzagging marks traversing her forehead and chin, parables of her youth tucked neatly in their crevices. I imagined these lines etched into place by a magnificent painter, some with delicacy and precision, others more gross, fashioned with the edge of adversity. Although she lay covered, her frailty was evident in the outlines of wiry limbs veiled thinly by hospital sheets. As a medical student attempting to recruit patient participants for the doctoring course I was a teaching assistant for, I was completely unprepared for the question, “Will you sing for me?” I had just mentioned I was a singer when she asked about my hobbies, but the last thing I expected was the request for a performance. Will you sing for me? My mind searched frantically for a song whose lyrics I could fully remember, and all I could muster was “Remedy” by Adele:

When the world seems so cruel And your heart makes you feel like a fool I promise you will see That I will be, I will be, I will be… Your remedy. 1

I finished quietly, trying not to wake the neighboring resident, although I already suspected this was a task far too gargantuan for the wispy curtain between them. “Why did you choose this song?” she whispered faintly, her eyes misting, flanked by the daintiest of the painter’s strokes. “It’s what I remembered,” was my first thought, but that felt insufficient. Forced to contemplate more deeply, I gradually and carefully detailed my conclusions…that this piece reminded me why I liked living. That it reassured me that even when no objective solution exists, a remedy can. That when I sing such lyrics, I feel time ever so slowly adjourning—palpable but not stagnant—coalescing into one pregnant, ubiquitous moment. The mist had lifted, water falling, the corners of her lips upturned, the peaks and valleys engraved by time now more salient…time that seemed to be dwindling. Despite her pain, “will you sing for me ?” she had chosen to ask.

The first day of medical school is typically marked by a White Coat Ceremony, where in exchange for our new garb, we take the Hippocratic Oath, a long list of promises including doing no harm, protecting the sick, and respecting their privacy. While these are duties we frequently discuss in modern medicine, there are others equally important warranting attention—more poignant, and perhaps therefore more overlooked. The pledge to “remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon’s knife or the chemist’s drug…that [we] do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being.” 2 This concept of what it means “to heal” in medicine is elusive. There is healing in the objective terms: to remove a tumor, to rid an infection; but there is also healing in the subjective, which naturally varies by person and context. However, subjectivity is not mutually exclusive from a framework; in fact it may depend on such scaffolding to cede any modicum of sense.

David Foster Wallace offers just such a framework in his 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech and subsequent essay “This is Water.” He opens with a “parable-ish story” about fish: “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’” 3 He goes on to artfully craft his response, and while his reasoning is filled with layers and nuance, it can be distilled into three major themes: the power of (1) presence and attention (2) conscious choice and (3) empathy and connection.

One of the most memorable points in Wallace’s speech is his comical, nihilistic depiction of the act of grocery shopping in a store, “hideously lit and infused with soul-killing muzak or corporate pop,” the check-out line full of “cow-like, dead-eyed and nonhuman” people—one of the many mundane, soul-crushing regularities of adulthood. 3 He decries a long list of relatable grievances faced by a specific but unfortunately large, subset of grocery shoppers: those on default. “If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options,” he writes. 3 When humans operate on default, ensnared in their endless web of thoughts, all of life can pass in one, decrepit blur. Wallace calls instead for presence and attention, awareness of the moment. His description of the grocery store is not meant to be comical, the audience gradually learns as his story unfolds. Without awareness, life can quickly devolve into a series of meaningless such instances; but with intentionality and conscious choice, these moments can be transformed.

Wallace masterfully denominates the armsmen of conscious choice: discipline and agency. He reflects:

Twenty years after my own graduation, I have come gradually to understand that the liberal arts cliché about teaching you how to think is actually shorthand for a much deeper, more serious idea: learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. 3

Awareness of the moment is incomplete without the choice to give it meaning. This agency takes discipline, but ultimately conceives an attitude and perspective of optimism. Wallace goes one step further, advocating for orienting such choice towards empathy and connection:

You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms…but of course there are all different kinds of freedom…The really important kind…involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day. 3

His grocery-shopping protagonist has the choice to consider the possibility that the other cow-like, dead-eyed humans in the store may be facing battles far more debilitating or tedious than his or her own. Wallace states, “It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.” 3

The majority of Wallace’s address is spent masterfully articulating his credo on the successful life, one predicated on presence and attention, conscious choice, and empathy and connection. He does not however forget the fish, at the end poignantly beseeching the audience to remember “This is water.” 3 And so, Wallace provides for us a framework within which to understand and facilitate healing, whether that be recovering from adversity or simply awakening from a life of drudgery. It is a framework that is essential to medicine, a field fraught with hardship, suffering, and outcomes that are often unideal. It is a reminder, put simply, to the clinician that the same scar can heal differently depending on its approximation—unruly, unkempt, and keloidal or controlled, clean, and intact.

For a speech with such lofty intention, Wallace’s main point is exceedingly clear. There is one nuance worth commenting on, however, not explicitly stated but rather woven intricately into the fibers of Wallace’s manifesto. In other versions of the opening parable, the young fish ask the old fish “Where is the ocean?” to which he says “You’re in it.” The young fish disappointedly respond, “Oh, but this is water.” Inherent to Wallace’s argument is one additional step between awareness and choice: acceptance. This, however, is not synonymous with floating or surrender, but rather the foundation on which productive action can be taken. In this version of the parable, the young fish are not necessarily wrong to ask “Where is the ocean?” because the quest is what encourages them to swim. Where their delusion lies is in their separation between water and the ocean. To them, the ocean represents the ideal outcome; anything less is merely water. They fail to recognize that water and the ocean are one and the same—that meaning does not depend on a specific outcome, but rather is derived from dedicated actions towards a noble goal. Attachment and expectation of an explicit outcome are imprisoning. It is this concept of detached engagement that inspires people to strive towards a better world and choose meaning in their own lives even when the end is uncertain or already unnervingly determined.

David Foster Wallace’s “This is Water” offers a beautiful reinvention on life, a framework for healing not only for those in the throes of illness but for a world and society reeling from a pandemic, political and social injustice, and the everyday challenges of simply living. It reminds me that time is sacred, its moments meant to be cherished and elevated by the choice to create meaning through love, empathy, and productive action unshackled by attachment; that the wrinkles Time anoints us with are to be honored, the battle scars of our efforts. In this reimagining, a remedy is always within reach. And so, Wallace concludes his deliverance:

The capital-T Truth is about life BEFORE death. It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: “This is water.” “This is water.” 3

Cover Image: Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons license. Soltan Salt Lake Iran. Amir Pashaei. CC-BY-SA-4.0

1. Adele. Lyrics to “Remedy.” Genius, 2015, https://genius.com/Adele-remedy-lyrics .

2. Lasagna, Louis. Hippocratic Oath: Modern Version. Pbs.org. 26 March, 2001. Web. 26 March 2021.

3. Foster Wallace, David. “Commencement Address.” Kenyon College. Gambier. 21 May 2005.

Share this:

Keep reading.

Playing the Percentages in Healthcare Education: The Absolutism of Grief

How to Feed the Sick: Hospital Meal and Patient Care in Modern Japan (part II: from the 1950s onward)

Care as a Living Terrain in My Body

Discover more from s y n a p s i s.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

This is Water by David Foster Wallace

The book in three sentences.

Learning “how to think” really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It can be easy to spend our entire lives accepting our natural default ways of thinking rather than choosing to look differently at life. The only thing that is capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see life and how you construct meaning from experience.

This is Water summary

This is my book summary of This is Water by David Foster Wallace. My notes are informal and often contain quotes from the book as well as my own thoughts. This summary includes key lessons and important passages from the book.

- The meaning we construct out of life is a matter of personal, intentional choice. It’s a conscious decision.

- So often, we hold beliefs so tightly we don’t even realize they can be questioned—arrogance, blind certainty, a closed-mindedness that’s like an imprisonment so complete that the prisoner doesn’t even know he’s locked up.

- A huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.

- Our natural setting is to be deeply and literally self-centered. There’s no experience you’ve had that you were not at the absolute center of. We see the whole world through this lens.

- People who can adjust away from this natural, self-centered setting are often described as “well-adjusted.”

- It is extremely difficult to stay alert and attentive instead of getting hypnotized by the constant monologue inside your head.

- Learning “how to think” really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think.

- You have to choose what you pay attention to and choose how you construct meaning from experience.

- It is not the least bit coincidental that adults who commit suicide with firearms nearly always shoot themselves in the head.

- The natural default setting is to think I am at the center of the world and my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.

- Most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at life. If you’ve really learned how to think, how to pay attention, then you will know you have other options.

- The only thing that is capital-T True in life is that you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it. This is the freedom of real education, of learning how to be well-adjusted: You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t.

- Everybody worships. We just get to choose what to worship.

- The trick is to keep truth up front in daily consciousness.

- The insidious thing about these forms of worship (money, power, fame, beauty, etc.) is not that they’re evil or sinful; it is that they are unconscious. They are default settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing.

- The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. That is being taught how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the “rat race” — the constant, gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.

- The biggest of questions is not about life after death. The capital-T Truth is about life before death. It is about making it to thirty, or maybe even fifty, without wanting to shoot yourself in the head.

- The real value of education has nothing to do with grades or degrees and everything to do with simple awareness—awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, that we have to keep reminding ourselves of it over and over.

Thanks for reading. You can get more actionable ideas in my popular email newsletter. Each week, I share 3 short ideas from me, 2 quotes from others, and 1 question to think about. Over 3,000,000 people subscribe . Enter your email now and join us.

James Clear writes about habits, decision making, and continuous improvement. He is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller, Atomic Habits . The book has sold over 20 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 60 languages.

Click here to learn more →

- Mastery by George Leonard

- When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

- The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant

- The Tell-Tale Brain by V.S. Ramachandran

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson

- All Book Summaries

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — David Foster Wallace — David Foster Wallace’s Use Of Rhetoric In This Is Water

David Foster Wallace’s Use of Rhetoric in This is Water

- Categories: Book Review David Foster Wallace Novel

About this sample

Words: 415 |

Published: Sep 1, 2020

Words: 415 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited:

- Alsbury, T. (2016). 10 Things About Being a Superhero That No One Talks About. Relevant Magazine.

- Batman Begins. (2005). [Film]. Warner Bros.

- Coates, T. (2018). Martin Luther King Jr. Was More Radical Than We Remember. The Atlantic.

- Harrison, C. (2019). 30 Everyday Heroes Who Changed Someone's Life Forever. Reader's Digest. https://www.rd.com/list/everyday-heroes-changed-someones-life-forever/

- Jenkins, P. (2006). Superman Returns. [Film]. Warner Bros.

- Krueger, P. (2014). Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. DC Comics.

- LeFevre, C. (2019). 9 Ways to Be a Hero for Someone Else Today. Success Magazine. https://www.success.com/9-ways-to-be-a-hero-for-someone-else-today/

- Martin, S. (2018). Motherhood is Heroic: Celebrating the Ordinary Superheroes Among Us. Today's Parent. https://www.todaysparent.com/family/parenting/motherhood-is-heroic-celebrating-the-ordinary-superheroes-among-us/

- Pallotta, F. (2018). 11 Real-Life Heroes Who Have Changed the World. Global Citizen.

- Spider-Man. (2002). [Film]. Columbia Pictures.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1.5 pages / 780 words

2 pages / 944 words

3.5 pages / 1498 words

2 pages / 1022 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on David Foster Wallace

Gourmet magazine had originally intended for David Foster Wallace to write a harmless review of the annual Maine Lobster Festival (MLF). As the essay continues, the reader notices the transition of a review of the festival into [...]

In 2005, David Foster Wallace delivered a commencement speech titled "This is Water" to the graduating class of 2005 at Kenyon College, a liberal arts college in Gambier, Ohio. This speech captivated its [...]

In “Consider the Lobster” David Foster Wallace is given the opportunity to write a review for a magazine, Gourmet. Which is meant to cover the Maine Lobster Festival held in the summer of 2003. However the review was nothing [...]

In David Foster Wallace’s article, Consider the Lobster, the author starts off explaining the festival he was attending, known as Maine Lobster Festival. Wallace starts by explaining what the Maine Lobster Festival is all about, [...]

Lobster is one of my much-loved seafood dishes due to its delicate rich flavored meat, however, after reading this article I have a change of mind. “Consider the Lobster” by David Foster Wallace is a controversial article to [...]

Overview of the reasons for Animal Farm's failure Role of social hierarchy and class differences The establishment of social groups and habitats The hierarchy with pigs at the top and less-educated animals at [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

This Is Water: David Foster Wallace on Life

By maria popova.

You can hear the original delivery in two parts below, along with the the most poignant passages.

On solipsism and compassion, and the choice to see the other :