Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Avoiding Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are errors of reasoning—specific ways in which arguments fall apart due to faulty connection making. While logical fallacies may be used intentionally in certain forms of persuasive writing (e.g., in political speeches aimed at misleading an audience), fallacies tend to undermine the credibility of objective scholarly writing. Knowledge of how successful arguments are structured, then—as well as of the different ways they may fall apart—is a useful tool for both academic reading and writing. If you are writing an annotated bibliography or literature review, for instance, being able to recognize logical flaws in others‘ arguments may enable you to critique the validity of claims, research results, or even theories in a particular text. Along the same lines, if you are putting together your own argumentative paper (KAM, dissertation proposal, prospectus, etc.), understanding argument structure and fallacies will help you avoid errors of reasoning in your own work.

Argument Structure

The basic structure of all arguments involves three interdependent elements:

- Claim (also known as the conclusion)—What you are trying to prove. This is usually presented as your essay‘s thesis statement.

- Support (also known as the minor premise)—The evidence (facts, expert testimony, quotes, and statistics) you present to back up your claims.

- Warrant (also known as major premise)—Any assumption that is taken for granted and underlies your claim.

Consider the claim, support, and warrant for the following examples:

Example 1 Claim : The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) has led to an increase in high school student drop-out rates. Support : Drop-out rates in the US have climbed by 20% since 2001. Warrant : (The claim presupposes that) it‘s a "bad" thing for students to drop out.

Example 2 Claim : ADHD has grown by epidemic proportions in the last 10 years Support : In 1999, the number of children diagnosed with ADHD was 2.1 million; in 2009, the number was 3.5 million. Warrant : (The claim presupposes that) a diagnosis of ADHD is the same thing as the actual existence of ADHD; it also presupposes that ADHD is a disease.

Claims fall into three categories: claims of fact, claims of value, and claims of policy. All three types of claims occur in scholarly writing although claims of fact are probably the most common type you will encounter in research writing. Claims of fact are assertions about the existence (past, present, or future) of a particular condition or phenomenon:

Example: Japanese business owners are more inclined to use sustainable business practices than they were 20 years ago.

The above statement about Japan is one of fact; either the sustainable practices are getting more popular (fact) or they are not (fact). In contrast to claims of fact, those of value make a moral judgment about a phenomenon or condition:

Example: Unsustainable business practices are unethical.

Notice how the claim is now making a judgment call, asserting that there is greater value in the sustainable than in the unsustainable practices. Lastly, claims of policy are recommendations for actions—for things that should be done:

Example: Japanese carmakers should sign an agreement to reduce carbon emissions in manufacturing facilities by 50% by the year 2025.

The claim in this last example is that Japanese carmakers‘ current policy regarding carbon emissions needs to be changed.

For the most part, the claims you will be making in academic writing will be claims of fact. Therefore, examples presented below will highlight fallacies in this type of claim. For an argument to be effective, all three elements—claim, support, and warrant—must be logically connected.

Although there are more than two dozen types and subtypes of logical fallacies, many of these are likelier to occur in persuasive, rather than expository or research, writing. Below are the most common forms of fallacy that you may encounter in the type of expository/research writing you are apt to do at Walden:

Example: Special education students should not be required to take standardized tests because such tests are meant for nonspecial education students.

Example: Two out of three patients who were given green tea before bedtime reported sleeping more soundly. Therefore, green tea may be used to treat insomnia.

- Sweeping generalizations are related to the problem of hasty generalizations. In the former, though, the error consists in assuming that a particular conclusion drawn from a particular situation and context applies to all situations and contexts. For example, if I research a particular problem at a private performing arts high school in a rural community, I need to be careful not to assume that my findings will be generalizable to all high schools, including public high schools in an inner city setting.

Example: Professor Berger has published numerous articles in immunology. Therefore, she is an expert in complementary medicine.

Example: Drop-out rates increased the year after NCLB was passed. Therefore, NCLB is causing kids to drop out.

Example: Japanese carmakers must implement green production practices, or Japan‘s carbon footprint will hit crisis proportions by 2025.

In addition to claims of policy, false dilemma seems to be common in claims of value. For example, claims about abortion‘s morality (or immorality) presuppose an either-or about when "life" begins. Our earlier example about sustainability ("Unsustainable business practices are unethical.") similarly presupposes an either/or: business practices are either ethical or they are not, it claims, whereas a moral continuum is likelier to exist.

As you can see from the examples above, there are many ways arguments can fall apart due to faulty connection making. When trying to induce inferences from data, for instance, it‘s important not to draw conclusions too quickly or too globally; otherwise, you may end up with errors of hasty or sweeping generalization that will weaken your overall thesis. Similarly, it‘s important not to construct an either-or argument when dealing with a complex, multi-faceted issue or to assume a causal relationship when dealing with a merely temporal one; the ensuing errors—false dilemma and post hoc ergo procter hoc, respectively—may weaken argument as well. Being attentive to logical fallacies in others‘ writings will make you a more effective "critic" and writer of literature review assignments, annotated bibliographies and article critiques. Being attentive to fallacies in your own writing will help you build more compelling arguments, whether putting together a dissertation prospectus or simply writing a short discussion post on the applications of a particular theory.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Comparing & Contrasting

- Next Page: Addressing Assumptions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How to Support an Argument and Avoid Logical Fallacies

What is an argument.

Every day we are presented with dozens of arguments that purport to be factual. Every day we must evaluate these statements and decide what we think about them—not only whether we agree with them or not, but also whether we think they are true. As you read this, you might take a minute to stop and think about how many such messages and statements you have already encountered today and how you thought about them.

Parts of an Argument

There are three basic parts to any argument, that is, three basic parts to any statement that is intended to persuade or prove something.

- Conclusion : This may or may not come at the end and is the author’s main idea

- Evidence : This is whatever the author or speaker uses to support the conclusion. (Below you will read about the various kinds of evidence, how to use them, and how to recognize when they are being misused.)

- Assumption (or Warrant) : This is rarely stated explicitly in the argument, but is absolutely central. The assumption is what holds the argument together and determines how the author or speaker looks at the evidence and comes to the conclusion.

Evaluating Arguments by Identifying the Assumption

The following examples illustrate how you can identify an author’s assumption by looking at the other parts (evidence and conclusion) of their argument:

- Evidence : Arbuthnot looks out his window and sees that it is snowing heavily.

- Conclusion : Winter is a difficult and dangerous time of year.

What is Arbuthnot’s assumption in making this statement? Although we cannot know with absolute certainty, we can make a well-informed guess that his assumption has to do with how dangerous snow is. For instance, Arbuthnot may be afraid of driving in snow or afraid that he will fall while shoveling snow. Whether you agree with his conclusion or not, you can at least see his assumption at work. Here is another example:

- Evidence : Montgomery looks out his window and sees that it is snowing heavily.

- Conclusion : Winter is great! I look forward to it every year.

What is Montgomery’s assumption? Well, without more to go on we cannot say absolutely, but we can safely guess that it must be something that includes an enjoyment of snow. For instance, Montgomery might love downhill skiing, snowboarding, and snowmobile-riding or making snow angels. Do you see how this works?

So, in order to evaluate the worth of any argument, you must consider what the author’s assumption might be. In the examples, Montgomery and Arbuthnot have exactly the same evidence, and yet have come to very different conclusions. What makes the difference? They started from different assumptions. Thus, when you are evaluating an argument presented to you, ask yourself what the author’s assumption might be. Then, consider whether you think that is a sound assumption. For instance, here is an argument:

We are the best because we sell the most!

Have you ever heard this argument before? What is the assumption here? It is that quantity (of sales) equals quality (of product)? Do you think that is a sound assumption? Do you agree with it?

Tools for an Effective Argument

In addition to operating on a sound assumption, to argue convincingly the author must present evidence and analysis that support the conclusion.

Five common tools in an effective argument:

- Expert opinions

Correct and Incorrect Use of Logic and Evidence

Evidence from experts.

The opinions of experts (also called authorities) can be invaluable. These are people who have some special knowledge on the subject, and their support lends believability to the author’s point. For instance, in a paper on why smoking is unhealthy, the U.S. Surgeon General and the chairs of either the American Lung Association or American Cancer Association would be strong authorities. Their authority comes from their professional experience. People become authorities for different reasons. They may have academic or professional training and experience, or they may also be people with extensive personal experience. Another authority on this topic might be a life-long smoker who now has extensive health problems.

However, using authorities may pose some dangers: The person may not be an authority in the right area. For example, “My lawyer told me about a great way to make my car run more fuel efficiently.” Advertising is notorious for using false authorities. For instance, Michael Jordan might be a good authority on the best basketball shoes, but does he really know more about underwear than anyone else? The classic example: “I may not be a doctor, but I play one on TV, so I know this is the best flu relief out there.”

Additionally, the topic may be hotly debated within the field—experts may disagree. When citing an authority, ask yourself not only if the person is truly an authority, but if they are in the area you are discussing. Also, note whether peers in the field generally accept what the authority says as true.

Evidence from Facts

Facts are proven to be true. For example, Helen Keller died on June 1, 1968. Support for this comes from many sources, one of which is her obituary in the The New York Times : http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0627.html

Facts are reliable sources of evidence. The problem comes in distinguishing fact from opinion. Opinions may look like facts, but they cannot be proven. For example, “The death penalty is wrong.” While one could gather evidence to support this opinion, one could also gather evidence against it. Ultimately, whether something is “wrong” or “right” is opinion.

Additionally, people may disguise opinion as fact by saying things like “The truth of the matter is . . .” or “It is a fact that . . .” but that does not mean what follows is fact. As a reader and writer, you need to evaluate what follows to determine if it is truly fact or opinion.

Evidence from Examples

Examples can be useful forms of evidence. In fact, in conversation, we often ask people to “give me an example.” For instance, your child comes home and says, “My teacher is not fair and does not like me.” You would most likely ask your child to give you some examples to support this claim. What could your child say back to you that would support the claim about the teacher?

Here are some possibilities: “They never call on me,” “They laugh when I give the wrong answer,” and so on. These examples clearly support your child’s claim, so they would be considered useful. What if, instead, your child said, “They wear the same outfit every day” or “They drink too much coffee”? Unless the teacher wears a shirt that says “I dislike Bobby” on it every day, you would say, “What does that have to do with how much they like you?” These examples do not support the claim. This example is an exaggeration, of course, but oftentimes people will use examples as evidence even though they really do not support their claims. You have to be on the alert for this as a writer and reader.

Using Logic

Authors use logic to build one known or proven fact upon another, leading the reader to agree that a certain point is true. For example, consider the case of Frank who has six cats. To prevent having even more cats, all Frank’s cats are female. Now consider his cat Zoe. What is Zoe’s sex? We know that all Frank’s cats are female, and we know Zoe belongs to Frank, so we can conclude that Zoe is a female. That is logic.

Logical arguments fall into two categories: induction and deduction. Deduction takes a generally known fact and uses it to argue for a more specific point. The example above of Frank and his cats is an example of deductive reasoning. Deduction is common. Induction, on the other hand, takes a specific case (or cases) and uses it to argue for a bigger generalization.

For example, it was hot today. It was hot yesterday, the day before, and the day before that. A logical conclusion is that it is summer. Induction is widely used in science. Scientists studying a particular species may notice that several individuals of that species exhibit a particular behavior.

They may then induce that all members of that species exhibit the behavior, even though they have not examined every individual member.

Induction is used less frequently because it can be faulty. For example, it was hot today. It was hot yesterday, the day before, and the day before that. What if it is not summer, but actually just a record-breaking October? Induction becomes more valid as the instances used to support the general conclusion become more specific.

Common Logical Fallacies

As seen above, even logical reasoning can result in incorrect conclusions. These are called logical fallacies. Several are common enough to have their own names and are described below.

Anecdotal Fallacy

Anecdotal fallacy, also called a hasty generalization or jumping to conclusions, is an inductive fallacy that occurs when one instance supports a general claim that is not true. For example, “I had a female boss once. She was demanding and unfair. Female bosses are the worst.” The speaker is using one example, the one female boss he or she had, to argue that all female bosses are horrid. Obviously—and your own personal experience may speak to this—they are not all bad.

Mistaking Time for Cause and Effect

Just because one thing happened prior to another does not mean the first caused the second, yet frequently people will argue just that. For instance, “The repair person was here this morning, and now my keys are missing. They must have stolen them.” The speaker could have just as easily misplaced them. Maybe their child grabbed them by accident. Just because A (the repair person at the house) happened before B (the loss of the keys) does not mean A caused B.

False Authority

When we trust authorities, we need to make sure they are authorities on the subject about which they are speaking. The speaker could tell you a great deal about acting, but not about your health.

Slippery Slope

Slippery-slope arguments are based on the idea that if one thing happens, then another thing will, then another, and another. Think of this as the “domino effect.” The problem is that while the first thing might lead to the next, there is no proof that any of the other things will happen. For example, “If I let my brother borrow this CD, then he will borrow my books, then he will want to borrow my clothes, and pretty soon, he will take over my bedroom!” (Children, among others, use this argument a lot.) While a brother allowed to borrow a CD might then ask to borrow a book, the guarantee that this will lead to room invasion is nonexistent. This logical fallacy should seem familiar—it is frequently used in political discussions on gun control and abortion.

Either-Or Dilemmas (A False Dichotomy)

“It is your choice—get a gym membership or be alone forever.” Are these really the only two options? Are there ways other than a gym membership to find that special someone? Of course there is. Either-or dilemmas, however, hide that fact by claiming only two options exist. Whenever you hear only two options, be suspicious. Other options likely exist.

Circular Reasoning

Circular reasoning, also called begging the question, happens when an assumption is used to prove the same assumption is true. In other words, the conclusion simply puts the assumption in other words. For example, “Jennifer Anniston is more popular than Courtney Cox-Arquette because more people like her.” Being popular and being liked are basically the same thing, so all this says is “She is more popular because she is more popular,” which is not saying much.

This literally means “against the person.” When a claim is rejected based simply on the person making it and not on the evidence the person has put forth, it is an ad hominem logical fallacy. The person, not the claim, is attacked. Why is this a logical fallacy? Because the claim the person is making is never attacked—only the person is. This personal attack is then used, falsely, to undermine the claim. Since the claim was never attacked, logically it has not been undermined, yet the attacker claims that it has. Here is an example:

- Meg : I hope the NFL is able to keep its eligibility requirements. According to ESPN, there are 1200 agents registered with the NFL. Over half have no clients. If the eligibility requirements are dropped, these agents are going to be filling high school football stadiums, scouting for new prospects, and convincing a lot of kids to forgo college in hopes of an NFL career. The bottom line is most won’t make it, and what will they have? No education, no job, and no hopes.

- Alan : You’re just a girl—what do you know about football?

For more examples of logical fallacies used in argument, refer to the Purdue Global Writing Center resource on Hasty Generalizations and Other Logical Fallacies .

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

- Library Catalogue

Avoiding logical fallacies in writing

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning. Fallacies are most often identified when a conclusion, claim, or argument is not properly supported by its premises (supporting statements). The following is a list of common logical fallacies:

Translation: "To the people", from Latin

Definition: Countering an argument by attacking the opponent's character, rather than the argument itself.

Example: "Reza Aslan, a religious scholar with a Ph.D. in the sociology of religions from the University of California and author of the new book Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth , went on FoxNews.com's online show Spirited Debate to promote their book only to be prodded about why a Muslim would write a historical book about Jesus."

Why a fallacy? The interviewer is countering the author's arguments by attacking their faith, rather than their arguments as outlined in the book.

Argument from Ignorance

Also Known as: Ad Ignorantium; Non-Testable Hypothesis

Definition: An argument that cannot be refuted because it has not been proven wrong; arguments from ignorance often based on untested/untestable claims.

A : "I believe in UFOs."

B : "But they've never been proven to exist…"

A : "But they've never been proven to not exist."

Why a fallacy? A's argument that UFOs exist cannot be proven because UFOs have never been proven to not exist; scientific inquiry cannot conclusively determine that they cannot exist. Hence, this is an untestable claim.

Appeal to authority

Also known as: Argument from authority

De f inition: An argument believed to be true, because it is presented by a figure perceived to carry legitimate authority.

A : "This doctor says that a low-carb diet is an effective method to lose weight, so I'm going to cut out all breads and pasta."

B : "Shouldn't you cut out your high-fat meat as well?"

A : "According to the doctor, I can eat as much meat as I want, and I'll still lose weight."

B : "Are the doctor's conclusions supported by the medical community?"

A : "I don't know, but they're a doctor, right? Their arguments have to be legit."

Why a fallacy? A supports the doctor's claims regarding a low-carb diet based on the assumption that, as a doctor, they have the education and experience to carry legitimate authority. However, just because the doctor speaks from authority, this doesn't mean their claim is true, especially if support from the medical community is questionable.

Begging the question

Definition: An argument that includes a conclusion within a premise; or assuming as true something that needs to be proved.

A : I'm so sorry my sibling wasn't that friendly to you at the party yesterday.

B : Oh, the vegan? Let me guess, your sibling saw me going for the chicken wings?

Why a fallacy? B's second question assumes that A's vegan sibling doesn't like them because they eat meat.

Similar to: Circular reasoning

Definition: Restating the claim, rather than trying to prove or support it.

Difference: In circular reasoning, the premise and conclusion are the same; in Begging the Question, the premise and conclusion may be different

Example: Some US presidents were considered excellent communicators because they spoke effectively.

Why a fallacy? Being an "excellent communicator" and "talking effectively" are essentially the same thing; hence, the same point is being used to explain the same point.

False analogy

Definition: An argument based on the assumed similarity between the two things being compared, when in fact they are not similar.

A : "I decided to go vegetarian because I find the state of the meat industry abhorrent. The way the animals are treated is like the way the Nazis treated the Jews in the concentration camps."

Why a fallacy? Although it is true that the living conditions of animals in the present meat industry can be terrible, it is fundamentally different to the living conditions of the Jews in Nazi Europe; A is presenting them as more alike than they are.

False dilemma

Also Known as: Black-or-White; Either/Or; Excluded Middle; False Dichotomy

Definition: Simplifying an issue to where only two possibilities, outcomes, or choices are available, when in fact, more exist.

A : "How do you propose we tackle terrorism?"

B : "Either we kill them or they kill us."

Why a fallacy? B is simplifying the issue of terrorism to two possibilities: kill, or get killed. There are number of possibilities (e.g. diplomacy) between these two extremes that are being ignored.

Hasty generalization

Definition: A conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence; often involves mistaking a small incident for a larger trend.

A : "I got a bad mark on my first assignment; this is going to be a bad course."

Why a fallacy? A is concluding that just because they got a bad mark on their first assignment, A is going to get bad marks on all the rest.

Moral equivalence

Definition: Assuming that two moral issues have similar weight, even though they may be completely different; often equates minor incidents with major events.

A : "The professor that gave me a bad mark on my assignment because I made one small mistake is a total Nazi."

Why a fallacy? A is equating the hard-marking professor with the Nazis, when the implications of the actions of both is completely different. The professor just gave the student a lower-than-expected grade, while the Nazis killed millions of people in the 1930s and 40s.

Post Hoc ergo Propter Hoc

Translation: "After this, therefore because of this" (Latin).

Definition: A conclusion based on the premise that if B occurs after A, then B must happen because of A; assumes cause and effect for two events that are related based only on their positions in time.

A : "I ate out, but now I am sick, so the food I ate while out must have made me sick."

Why a fallacy? A is assuming that because they ate out before getting sick, the food they ate must have made them sick. However, the food they ate is only one of a multitude of reasons why they might be sick.

Similar to: Correlation not causation

Definition: A's conclusion based on the premise that an observed correlation between A and B means that A caused B; this excludes the possibility of an external factor causing the correlative relationship between A and B.

Difference: Post Hoc is based on a temporal relationship between two events, whereas Correlation not Causation can be any kind of relationship.

Red herring

Definition: Avoiding opposing arguments by diverting attention away from the core issue being argued; this is often done by raising tangential issues mid-debate.

Example: North Korea consistently blaming US "imperialist" aggression for their domestic problems.

Why a fallacy? By laying blame on the US, the North Korean government is trying to distract the populace from its own difficulties in properly managing domestic affairs.

Slippery slope

Definition: A conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then B will happen, then C, and so on, which will lead to (a much more extreme) Z, therefore A should not be accepted/occur; in other words, A is equated with Z.

A : "If we legalize soft drugs, like marijuana, more people will be interested in using hard drugs, and then crime rates will increase, which will result in the failure of society as we know it. So we should ban drugs altogether."

Why a fallacy? A assumes that opening the door to soft drugs will eventually cause the collapse of society, through a number of small intermediate steps that may not necessarily follow.

Definition: Countering an argument by attacking a different position than the one argued; this is often done by misrepresenting the opponent's argument in order to make it easier to counter, and then countering the misrepresented argument.

A : "I support a woman's right to control her body, thus I support abortion."

B : "You realize that you're supporting mass-murder, right? Women who abort their fetuses are killing innocent lives."

Why a fallacy? B is misrepresenting A's argument about women having control over their own bodies by equating abortion to murder, then countering A's argument on the basis that by supporting abortion, A is, in fact, supporting mass-murder.

Please note that this is not an exhaustive list of fallacies; there are many others.

If you have questions about the logic of your argument(s), talk to your professor or TA, and/or come to see one of the peers at the Student Learning Commons.

- The Concise Canadian Writer's Handbook, 2nd ed. William E. Messenger, Jan de Bruyn, Judy Brown, and Ramona Montagnes. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Thou Shalt Not Commit Logical Fallacies

- The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe

- ScribblePreach

- Drake's List of the Most Common Logical Fallacies

Handout created by Helen Bowman, SFU student and Learning and Writing Peer Educator, 2013

Unit 6: Argumentative Essay Writing

47 Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning based on faulty logic . Good writers want to convince readers to agree with their arguments—their reasons and conclusions. If your arguments are not logical, readers won’t be convinced. Logic can help prove your point and disprove your opponent’s point—and perhaps change a reader’s mind about an issue. If you use faulty logic (logic not based on fact), readers will not believe you or take your position seriously.

Read about five of the most common logical fallacies and how to avoid them below:

- Generalizations

- Loaded words

- Inappropriate authority figures

- Either/or arguments

- Slippery slope

Common Logical Fallacies

Below are five of the most common logical fallacies.

#1 Generalizations

Explanation: Hasty generalizations are just what they sound like—making quick judgments based on inadequate information. This kind of logical fallacy is a common error in argumentative writing.

Example 1: Ren didn’t want to study at a university. Instead, Ren decided to go to a technical school. Ren is now making an excellent salary repairing computers. Luis doesn’t want to study at a university. Therefore, Luis should go to a technical school to become financially successful.

Analysis: While they have something in common (they both want to go to school and earn a high salary), this fact alone does not mean Luis would be successful doing the same thing that their friend Ren did. There may be other specific information which is important as well, such as the fact that Ren has lots of experience with computers or that Luis has different skills.

Example 2: If any kind of gun control laws are enacted, citizens will not be allowed to have any guns at all.

Analysis: While passing new gun control laws may result in new restrictions, it is highly unlikely the consequences would be so extreme; gun control is a complex issue and each law that may be passed would have different outcomes. Words such as “all,” “always,” “never,” “everyone,” “at all” are problematic because they cannot be supported with evidence. Consider making less sweeping and more modest conclusions.

Suggestions for Avoiding Generalizations

Replace “absolute” expressions with more “softening” expressions.

- Replace words like “all” or “everyone” with “most people.” Instead of “no one” use “few people.”

- Replace “always” with “typically” or “usually” or “often.”

- Replace “never” with “rarely” or “infrequently” or the “to be verb” + “unlikely.”

- Replace “will” with “may or might or could” or use the “to be verb” + “likely.”

Example 1 revised: Luis could consider going to a technical school. This education track is more likely to lead to financial success.

Example 2 revised: If extensive gun control laws are enacted, some citizens may feel their constitutional rights are being limited.

#2 Loaded Words

Explanation: Some words contain positive or negative connotations, which may elicit a positive or negative emotional response. Try to avoid them in academic writing when making an argument because your arguments should be based on reason (facts and evidence), not emotions. In fact, using these types of words may cause your reader to react against you as the writer, rather than being convincing as you hoped. Therefore they can make your argument actually weaker rather than stronger.

Example 1: It is widely accepted by reasonable people that free-trade has a positive effect on living standards, although some people ignorantly disagree with this.

Analysis: The words “reasonable” (positive) and “ignorantly” (negative) may bias the readers about the two groups without giving any evidence to support this bias.

Example 2: This decision is outrageous and has seriously jeopardized the financial futures for the majority of innocent citizens.

Analysis: The words “outrageous,” “seriously,” and “innocent” appeal to readers’ emotions in order to persuade them more easily. However, the most persuasive arguments in academic writing will be supported with evidence instead of drawing on emotions.

Suggestions for Avoiding Loaded Words

Choose appropriate vocabulary.

- Omit adjectives and adverbs, especially if they carry emotion, value, or judgment.

- Replace/add softeners like, “potentially” or modals like “might” or “may.”

Example 1 revised: It is widely accepted by many people that free-trade may have a positive effect on living standards, although some people may disagree with this.

Example 2 revised: This decision has potentially serious consequences for the financial futures for the majority of citizens.

#3 Inappropriate authority figures

Explanation: Using famous names may or may not help you prove your point. However, be sure to use the name logically and in relation to their own area of authority.

Example 1: Albert Einstein , one of the fathers of atomic energy, was a vegetarian and believed that animals deserved to be treated fairly. In short, animal testing should be banned.

Analysis: While Einstein is widely considered one of the great minds of the 20th century, he was a physicist , not an expert in animal welfare or ethics.

Example 2: Nuclear power is claimed to be safe because there is very little chance for an accident to happen, but little chance does not have the same meaning as safety. Riccio (2013), a news reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal, holds a strong opinion against the use of nuclear energy and constructions of nuclear power plants because he believes that the safety features do not meet the latest standards.

Analysis: In order to provide strong evidence to support the claim regarding the safety features of nuclear power plants, expert opinion is needed ; the profession of a reporter does not provide sufficient expertise to validate the claim.

Suggestions for Avoiding Inappropriate Authority Figures

Replace inappropriate authority figures with credible experts.

- Read through your sources and look for examples of experts. Pay attention to their credentials. (See examples below.)

- Find new sources written by or citing legitimate experts in the field.

- Google the authority figure you wish to use to determine if they are an expert in the field. Use the Library Databases to locate a substantive or scholarly article related to your topic. Cite the author of one of these articles or use an indirect citation to cite an expert mentioned in the article.

Example 1 revised: Kitty Block, president and CEO of the Humane Society of the U.S. , emphasizes the need for researchers to work with international governments and agencies to follow new guidelines to protect animals and minimize their use in animal testing.

Example 2 revised: Edwin Lyman, senior scientist of the Global Security Program, points out that while the U.S. has severe-accident management programs, these plans are not evaluated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and therefore may be subject to accidents or sabotage.

#4 Either/Or Arguments

Explanation: When you argue a point, be careful not to limit the choices to only two or three. This needs to be qualified.

Example 1: Studying abroad either increases job opportunities or causes students to become depressed.

Analysis: This statement implies that only two things may happen, whereas in reality these are two among many possible outcomes.

Example 2: People can continue to spend countless amounts of tax dollars fighting the use of a relatively safe drug, or they can make a change, legalize marijuana, and actually see a tax and revenue benefit for our state. (owl.excels ior.edu)

Analysis: Most issues are very complex and hardly ever either/or, i.e. they rarely have only two opposing ways of looking at them or two possible outcomes. Instead, use language that acknowledges the complexity of the issue.

Suggestions for Avoiding Either/Or Arguments

Offer more than one or two choices, options, or outcomes.

- If relevant for your essay focus, offer more than one or two choices, options, or outcomes.

- Acknowledge that multiple outcomes or perspectives exist.

Example 1 revised: Studying abroad may have a wide spectrum of outcomes , both positive and negative, from increasing job opportunities to leading to financial debt and depression.

Example 2 revised: There are a number of solutions for mitigating the illegal sale of marijuana, including legalizing the use of the drug in a wider range of contexts, increasing education about the drug and its use, and creating legal businesses for the sale, among other business related solutions.

#5 Slippery Slope

Explanation: When you argue that a chain reaction will take place, i.e. say that one problem may lead to a greater problem, which in turn leads to a greater problem, often ending in serious consequences. This way of arguing exaggerates and distorts the effects of the original choice. If the series of events is extremely improbable, your arguments will not be taken seriously.

Example 1: Animal experimentation reduces society’s respect for life. If people don’t respect life, they are likely to be more and more tolerant of violent acts like war and murder. Soon society will become a battlefield in which everyone constantly fears for their lives.

Analysis: This statement implies that allowing animal testing shows a moral problem which can lead to completely different, greater outcomes: war, death, the end of the world! Clearly an exaggeration.

Example 2: If stricter gun control laws are enacted, the right of citizens to own guns may be greatly restricted, which may limit their ability to defend themselves against terrorist attacks. When that happens, the number of terrorist attacks in this country may increase. Therefore, gun control laws may result in higher probability of widespread terrorism. (owl.excelsior.edu)

Analysis: The issue of gun control is exaggerated to lead into a very different issue. Check your arguments to make sure any chains of consequences are reasonable and still within the scope of your focused topic. (writingcenter.unc.edu)

Suggestions for Avoiding Slippery Slope

Think through the chain of events.

- Carefully think about the chain of events and know when to stop to make sure these events are still within the narrowed focus of your essay.

Example 1 revised: If animal experimentation is not limited, an increasing number of animals will likely continue to be hurt or killed as a result of these experiments.

Example 2 revised: With stricter gun laws, the number of citizens who are able to obtain firearms may be reduced, which could lead to fewer deaths involving guns.

As you read your own work, imagine you are reading the draft for the first time. Look carefully for any instances of faulty logic and then use the tips above to eliminate the logical fallacies in your writing.

Adapted from Great Essays by Folse, Muchmore-Vokoun, & Soloman

For more logical fallacies, watch this video.

from GCFLearnFree.org

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Logical Fallacies

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Fallacies are common errors in reasoning that will undermine the logic of your argument. Fallacies can be either illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points, and are often identified because they lack evidence that supports their claim. Avoid these common fallacies in your own arguments and watch for them in the arguments of others.

Slippery Slope: This is a conclusion based on the premise that if A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen, too, basically equating A and Z. So, if we don't want Z to occur, A must not be allowed to occur either. Example:

If we ban Hummers because they are bad for the environment eventually the government will ban all cars, so we should not ban Hummers.

In this example, the author is equating banning Hummers with banning all cars, which is not the same thing.

Hasty Generalization: This is a conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence. In other words, you are rushing to a conclusion before you have all the relevant facts. Example:

Even though it's only the first day, I can tell this is going to be a boring course.

In this example, the author is basing his evaluation of the entire course on only the first day, which is notoriously boring and full of housekeeping tasks for most courses. To make a fair and reasonable evaluation the author must attend not one but several classes, and possibly even examine the textbook, talk to the professor, or talk to others who have previously finished the course in order to have sufficient evidence to base a conclusion on.

Post hoc ergo propter hoc: This is a conclusion that assumes that if 'A' occurred after 'B' then 'B' must have caused 'A.' Example:

I drank bottled water and now I am sick, so the water must have made me sick.

In this example, the author assumes that if one event chronologically follows another the first event must have caused the second. But the illness could have been caused by the burrito the night before, a flu bug that had been working on the body for days, or a chemical spill across campus. There is no reason, without more evidence, to assume the water caused the person to be sick.

Genetic Fallacy: This conclusion is based on an argument that the origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth. Example:

The Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally designed by Hitler's army.

In this example the author is equating the character of a car with the character of the people who built the car. However, the two are not inherently related.

Begging the Claim: The conclusion that the writer should prove is validated within the claim. Example:

Filthy and polluting coal should be banned.

Arguing that coal pollutes the earth and thus should be banned would be logical. But the very conclusion that should be proved, that coal causes enough pollution to warrant banning its use, is already assumed in the claim by referring to it as "filthy and polluting."

Circular Argument: This restates the argument rather than actually proving it. Example:

George Bush is a good communicator because he speaks effectively.

In this example, the conclusion that Bush is a "good communicator" and the evidence used to prove it "he speaks effectively" are basically the same idea. Specific evidence such as using everyday language, breaking down complex problems, or illustrating his points with humorous stories would be needed to prove either half of the sentence.

Either/or: This is a conclusion that oversimplifies the argument by reducing it to only two sides or choices. Example:

We can either stop using cars or destroy the earth.

In this example, the two choices are presented as the only options, yet the author ignores a range of choices in between such as developing cleaner technology, car-sharing systems for necessities and emergencies, or better community planning to discourage daily driving.

Ad hominem: This is an attack on the character of a person rather than his or her opinions or arguments. Example:

Green Peace's strategies aren't effective because they are all dirty, lazy hippies.

In this example, the author doesn't even name particular strategies Green Peace has suggested, much less evaluate those strategies on their merits. Instead, the author attacks the characters of the individuals in the group.

Ad populum/Bandwagon Appeal: This is an appeal that presents what most people, or a group of people think, in order to persuade one to think the same way. Getting on the bandwagon is one such instance of an ad populum appeal.

If you were a true American you would support the rights of people to choose whatever vehicle they want.

In this example, the author equates being a "true American," a concept that people want to be associated with, particularly in a time of war, with allowing people to buy any vehicle they want even though there is no inherent connection between the two.

Red Herring: This is a diversionary tactic that avoids the key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them. Example:

The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families?

In this example, the author switches the discussion away from the safety of the food and talks instead about an economic issue, the livelihood of those catching fish. While one issue may affect the other it does not mean we should ignore possible safety issues because of possible economic consequences to a few individuals.

Straw Man: This move oversimplifies an opponent's viewpoint and then attacks that hollow argument.

People who don't support the proposed state minimum wage increase hate the poor.

In this example, the author attributes the worst possible motive to an opponent's position. In reality, however, the opposition probably has more complex and sympathetic arguments to support their point. By not addressing those arguments, the author is not treating the opposition with respect or refuting their position.

Moral Equivalence: This fallacy compares minor misdeeds with major atrocities, suggesting that both are equally immoral.

That parking attendant who gave me a ticket is as bad as Hitler.

In this example, the author is comparing the relatively harmless actions of a person doing their job with the horrific actions of Hitler. This comparison is unfair and inaccurate.

Grand Valley State University

Search fred meijer center for writing & michigan authors, fred meijer center for writing & michigan authors.

- About Our Staff

- Mission, Vision, Values, & Services

- Hours & Locations

- Brooks College

- How to Prepare

- Weekly Appointment

- Language Rights

- Consultant Training

- Our History

- Undergraduate Support

- Graduate Support

- English Language Services

- Online Services

- Writing Resources

- Become A Consultant

- Teaching Support

- Writing Support

- SWS Connect

- GVSU Centers

- Library Research Center

- Knowledge Market

- For Consultants

Avoiding Logical Fallacies in Your Writing

How to argue well.

One of the easiest ways to strengthen a paper that presents an argument is to free it from improper logical reasoning. Here’s a list of commonly used yet fallacious types of argument to be sure to avoid.*

*Note: The examples of this document are not written to offend. Rather, they serve solely as an example of what is often seen in essay writing.

Reductio ad Absurdum/Slippery Slope:

This type of argument assumes the truth of the opponent’s position, and draws out the consequences of it being true, looking for a contradiction or an undesirable, absurd consequence. It is possible for this argument to be valid, but the fallacy occurs when the opponent’s consequences become unrealistic.

- Let’s say we allow homosexuals to marry. Then we would also need to allow people to have multiple spouses. Then we’d need to allow people to marry dogs. Soon the institution of marriage will just be a joke.

An argument in which a weak, generally inaccurate version of an opposing viewpoint is presented as a means of strengthening one’s own argument.

- Opponents of the war say that we can just have tea with the terrorists and everything will be okay. Obviously, this is wrong, so we need to bomb Iraq

False Dilemma:

Also called a false dichotomy, this is an argument that falsely states or implies that only two options are available: the position being argued, or something undesirable.

- If we don’t teach people Christian values in schools, they will not learn morals. Therefore, we must teach people Christian values in schools.

Affirming the Consequent:

This is a formally invalid argument of the form “If A, then B; B; therefore A.” It confuses the idea that A can only be true when B is true for the idea that B can only be true if A is true.

- If Iraq was supporting Al Qaeda, then Al Qaeda would have had enough money to attack us on 9/11. They had enough money to attack us, so Iraq was supporting Al Qaeda.

Denying the Antecedent:

This is a formally invalid argument of the form “If A, then B; not A; therefore not B.” It contains the incorrect assumption that B cannot be true if A is not true in cases where B must be true if A is true.

- If I get hit with a Cruise missile, then I’ll die. I won’t get hit with a Cruise missile. Therefore, I won’t die.

Circular Arguments:

This is an argument in which the truth of the premises of the argument depends upon the truth of the very conclusion to which the premises lead.

- The Bible is correct because it was divinely inspired. The Bible says that God exists. Therefore, since the Bible says that God exists and the Bible is correct, God exists.

Equivocating:

This argument takes two terms that are different but that can be misconstrued as similar, and treats them as similar to prove a point.

- Grand Valley says that a liberal education is important, but most of the people who go here are conservatives. Therefore, if we want to make the most people happy, we need to stop focusing on liberal education. (“Liberal” as it is used by political pundits is not what is meant by “liberal” in “liberal education”, but this argument treats the two terms as if they mean the same thing.)

Ad Hominem:

This is an argument where a point is made by attacking a person rather than the soundness of the argument that the person is making.

- Michael Moore has pointed out that the Bush family has a financial relationship with the Bin Ladin Family. However, Michael Moore is fat, and obviously dislikes the President, so we can disregard that fact.

Appeal to the Populous:

This form of argument involves an appeal to the popularity of an idea rather than the construction of a sound argument to support it.

- Most people in America think that passing laws banning gay marriage doesn’t amount to discrimination. Therefore, those laws aren’t discriminatory.

Appeal to Authority:

Students often use the fact that a noted authority made some statement, “X”, as evidence for the proof of statement X. However, this is not a sound argument.

- My professor in my class said that the war in Iraq is not going anywhere. Therefore, it obviously isn’t going anywhere.

Appeal to Tradition:

Often times, the fact that something has gone on for a long time is presented as evidence that it should go on.

- There have been rich people and poor people throughout the entire history of the United States. Therefore, I don’t see any reason to change the way the system runs.

Red Herring:

An argument that brings attention a matter irrelevant to the actual topic in order to prove one’s point about the topic at hand. This can be used very subtly, especially when distracting the audience with a matter that arouses strong emotion.

- My opponents have stated that an invasion of Iraq would be a drastic misstep in the war on terror, but we must remember that 3000 people died on 9/11, and that the terrorist threat is ever-looming.

To view or print our Helpful Handout, click here: Avoiding Logical Fallacies

For more resources on Argumentation, consider reviewing the following pages and/or handouts:

The Communication Triangle

Attention to Audience

Persuading Your Reader *

Have other questions? Stop in and visit! Or call us at 331-2922.

[1726082868].jpg)

- GVSU is an AA/EO Institution

- Privacy Policy

- HEERF Funding

- Disclosures

- Copyright © 2024 GVSU

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Weekly Updates

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that are based on poor or faulty logic. When presented in a formal argument, they can cause you to lose your credibility as a writer, so you have to be careful of them.

Sometimes, writers will purposefully use logical fallacies to make an argument seem more persuasive or valid than it really is. In fact, the examples of fallacies on the following pages might be examples you have heard or read. While using fallacies might work in some situations, it’s irresponsible as a writer, and, chances are, an academic audience will recognize the fallacy.

However, most of the time, students accidentally use logical fallacies in their arguments, so being aware of logical fallacies and understanding what they are can help you avoid them. Plus, being aware of these fallacies can help you recognize them when you are reading and looking for source material. You wouldn’t want to use a source as evidence if the author included some faulty logic.

The following pages will explain the major types of fallacies, give you examples, and help you avoid them in your arguments.

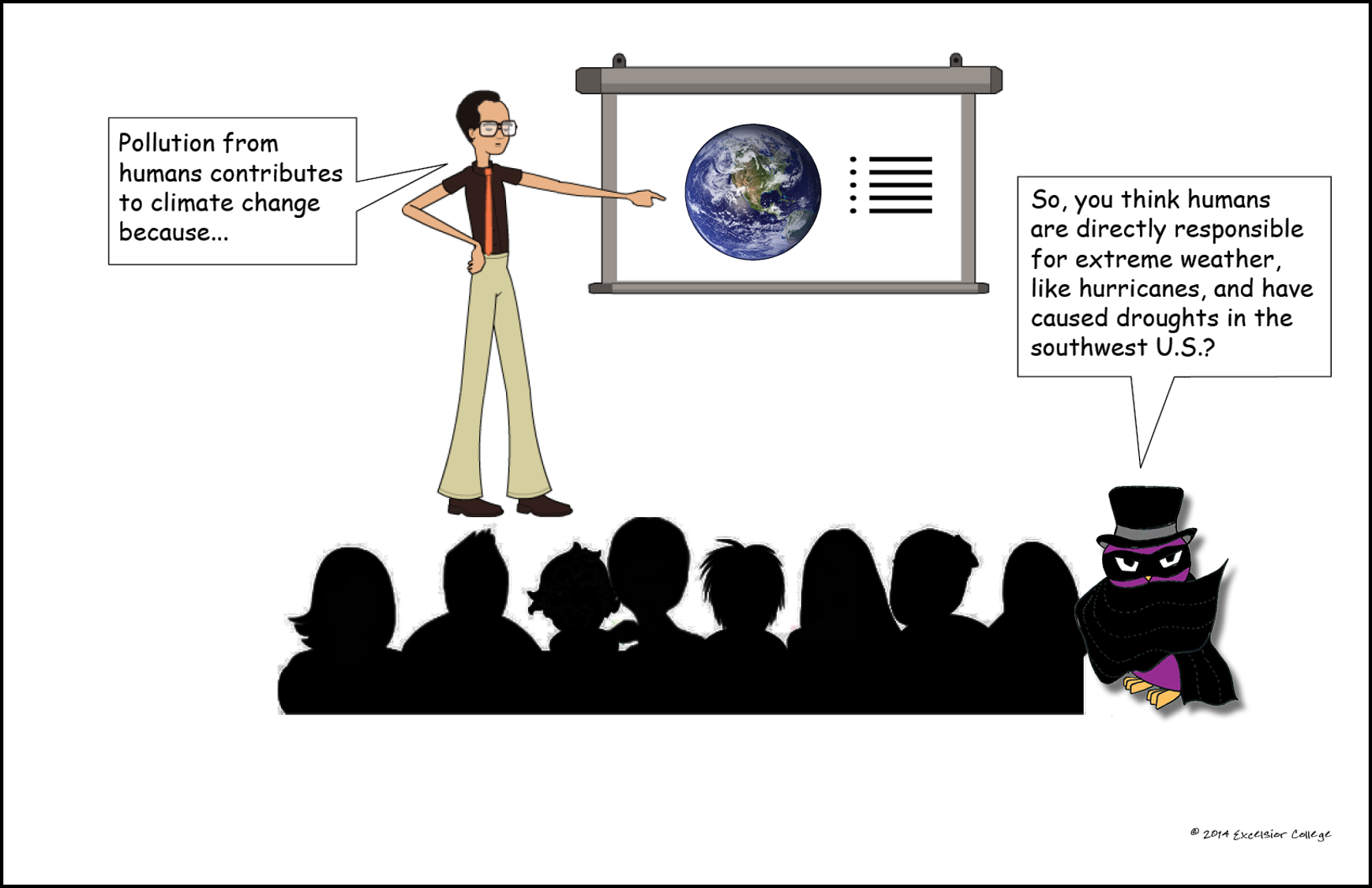

Straw Man Fallacy

A straw man fallacy occurs when someone takes another person’s argument or point, distorts it or exaggerates it in some kind of extreme way, and then attacks the extreme distortion, as if that is really the claim the first person is making.

Person 1: I think pollution from humans contributes to climate change. Person 2: So, you think humans are directly responsible for extreme weather, like hurricanes, and have caused the droughts in the southwestern U.S.? If that’s the case, maybe we just need to go to the southwest and perform a “rain dance.”

The comic below gives you a little insight into what this fallacy might look like. Join Captain Logic as he works to thwart the evil fallacies of Dr. Fallacy!

In this example, you’ll notice how Dr. Fallacy completely distorted the speaker’s point. While this is an extreme example, it’s important to be careful not to fall into this kind of fallacy on a smaller scale because it’s quite easy to do. Think about times you may have even accidentally misrepresented the other side in an argument. We have to be careful to avoid even the accidental straw man fallacy!

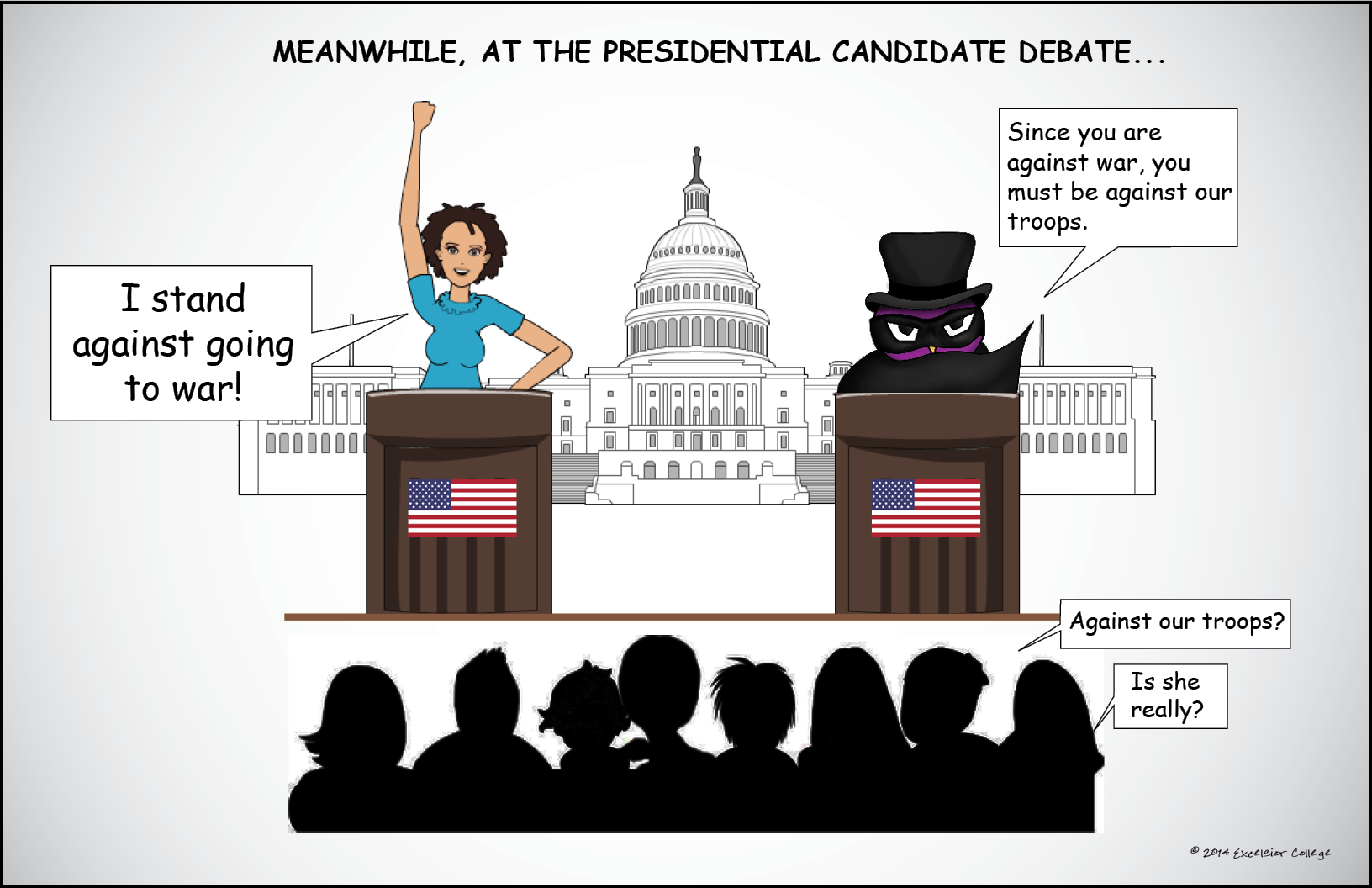

False Dilemma Fallacy

Sometimes called the “either-or” fallacy, a false dilemma is a logical fallacy that presents only two options or sides when there are many options or sides. Essentially, a false dilemma presents a “black and white” kind of thinking when there are actually many shades of gray.

Person 1: You’re either for the war or against the troops. Person 2: Actually, I do not want our troops sent into a dangerous war.

The comic below gives you a little insight into what this fallacy might look like. Observe as Captain Logic saves the day from faulty logic and the evil Dr. Fallacy!

In this comic, you’ll notice that Dr. Fallacy is presenting only two options, but the first person clearly has a middle position. You have to be really careful of this kind of fallacy, as it can really turn your audience away from your position. The world is complex, and the way people think is complex. If you dismiss that, you could lose the respect and interest of your audience.

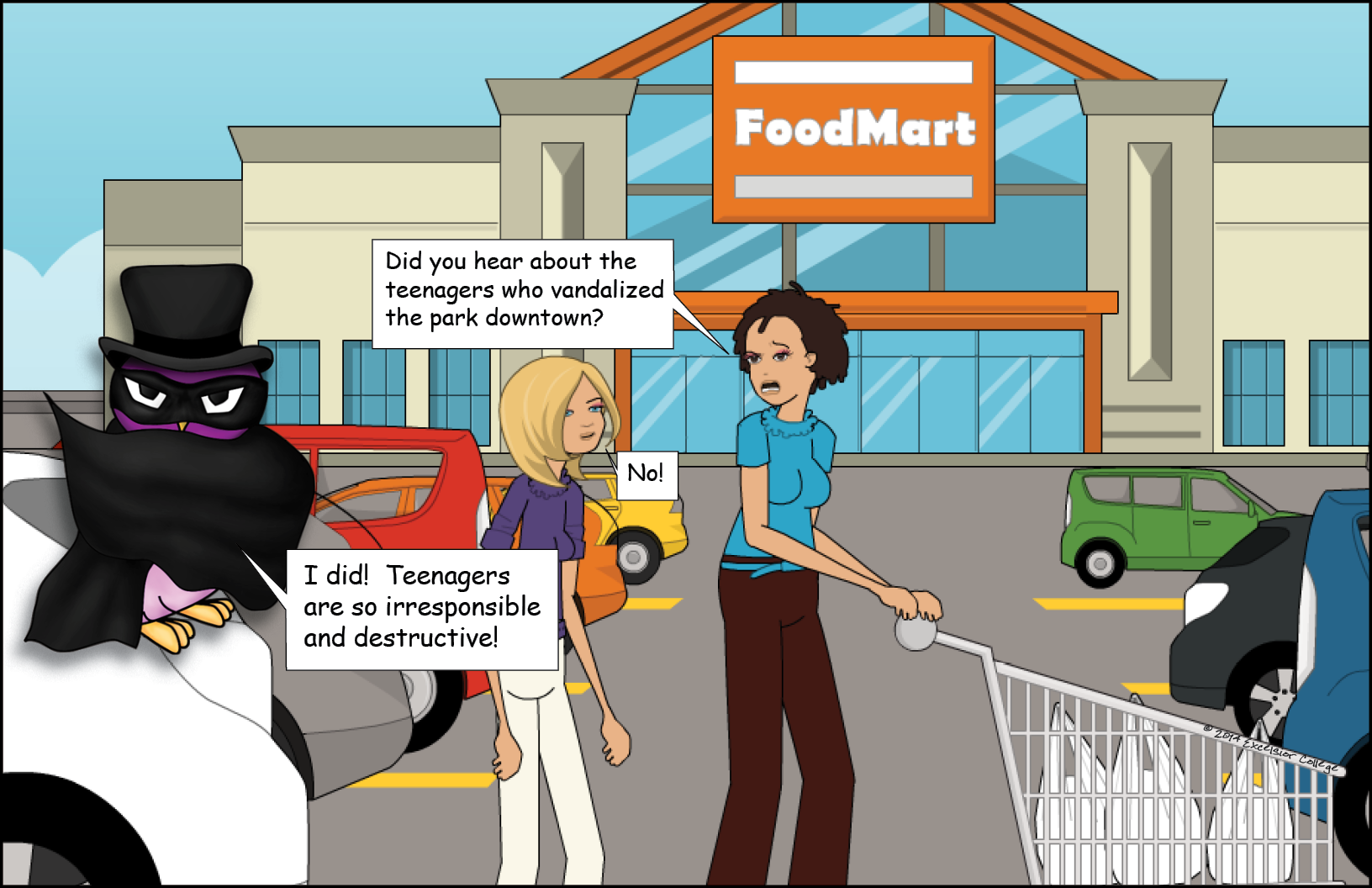

Hasty Generalization Fallacy

The hasty generalization fallacy is sometimes called the over-generalization fallacy. It is basically making a claim based on evidence that it just too small. Essentially, you can’t make a claim and say that something is true if you have only an example or two as evidence.

Example: Some teenagers in our community recently vandalized the park downtown. Teenagers are so irresponsible and destructive.

You can see Dr. Fallacy in action with this type of fallacy in the comic below.

In this example, Dr. Fallacy is making a claim that all teenagers are bad based on the evidence of one incident. Even with the evidence of ten incidences, Dr. Fallacy couldn’t make the claim that all teenagers are problems.

In this instance, the fallacy seems clear, but this kind of fallacious thinking is quite common. People will make claims about all kinds of things based on one or two pieces of evidence, which is not only wrong but can be dangerous. It’s really easy to fall into this kind of thinking, but we must work to avoid it. We must hold ourselves to higher standards when we are making arguments.

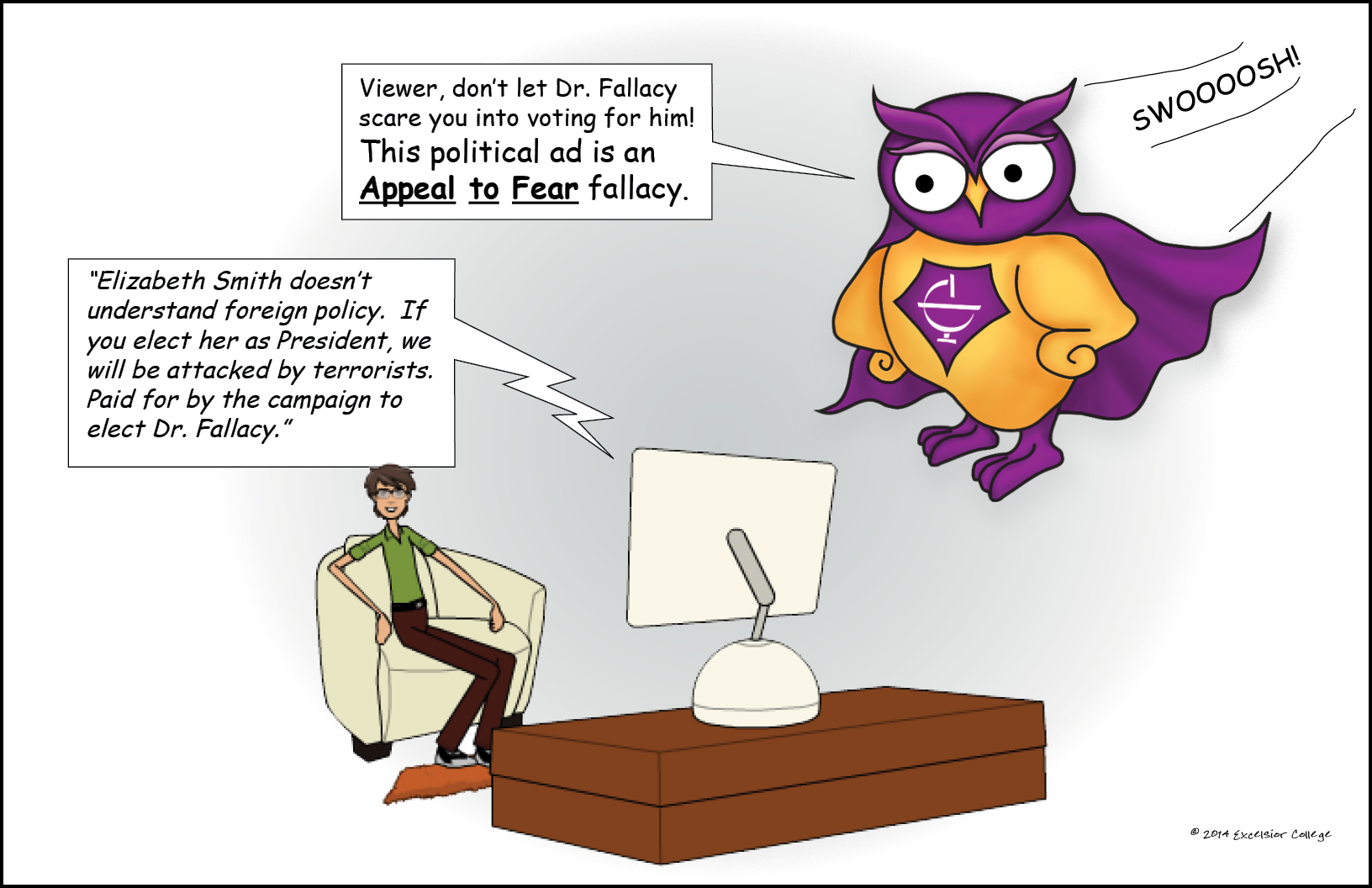

Appeal to Fear Fallacy

This type of fallacy is one that, as noted in its name, plays upon people’s fear. In particular, this fallacy presents a scary future if a certain decision is made today.

Example:

Elizabeth Smith doesn’t understand foreign policy. If you elect Elizabeth Smith as president, we will be attacked by terrorists.

You can see this fallacy in action in Dr. Fallacy’s campaign ad in the comic below.

Thankfully, the voters saw through Dr. Fallacy’s faulty logic. While this kind of claim seems outlandish, similar claims have been made by candidates in elections for years. Obviously, this kind of claim isn’t logical, however. No one can predict the future, but making a bold claim like this with no evidence at all is a clear logical fallacy.

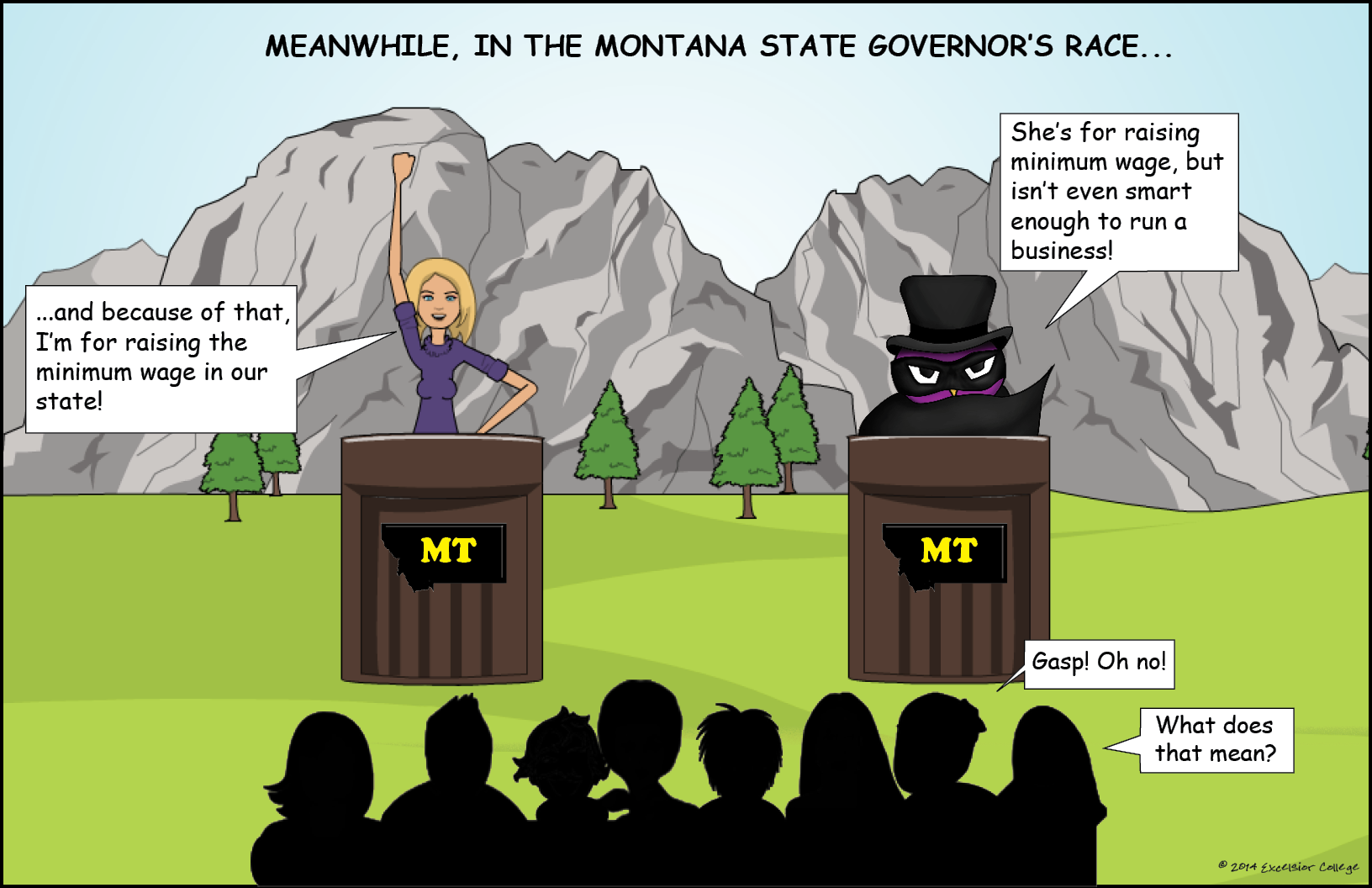

Ad Hominem Fallacy

Ad hominem means “against the man,” and this type of fallacy is sometimes called name calling or the personal attack fallacy. This type of fallacy occurs when someone attacks the person instead of attacking his or her argument.

Person 1:

I am for raising the minimum wage in our state.

She is for raising the minimum wage, but she is not smart enough to even run a business.

Check out Dr. Fallacy as he tries to get away with this type of fallacy. Thankfully, Captain Logic OWL saves the day!

In this example, Dr. Fallacy doesn’t address the issue of minimum wage and, instead, attacks the person. When we attack the person instead of tackling the issue, our audience might think we don’t understand the issue or can’t disprove our opponent’s view. It’s better to stick to the issue at hand and avoid ad hominem fallacies.

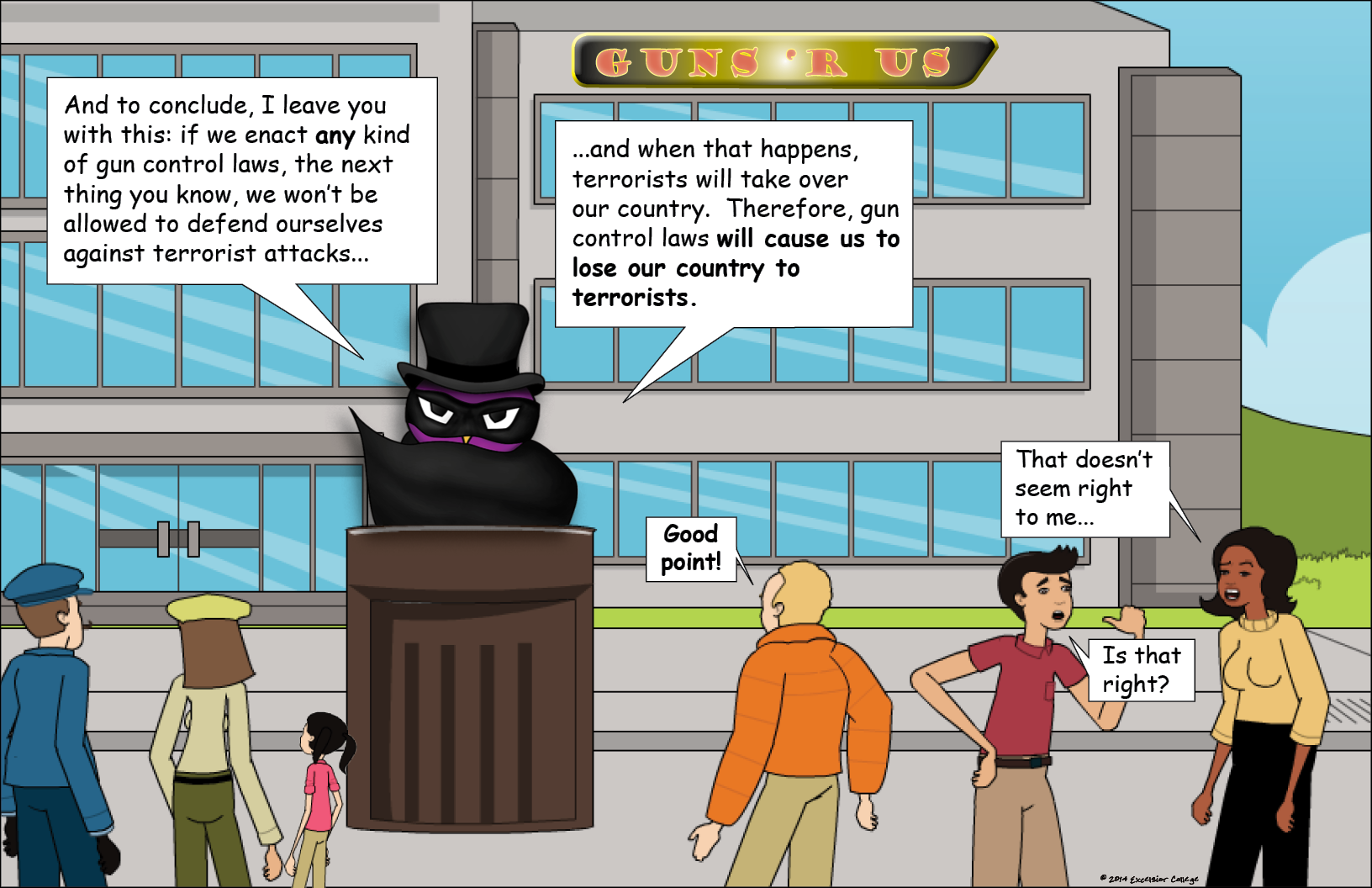

Slippery Slope Fallacy

A slippery slope fallacy occurs when someone makes a claim about a series of events that would lead to one major event, usually a bad event. In this fallacy, a person makes a claim that one event leads to another event and so on until we come to some awful conclusion. Along the way, each step or event in the faulty logic becomes more and more improbable.

Example:

If we enact any kind of gun control laws, the next thing you know, we won’t be allowed to have any guns at all. When that happens, we won’t be able to defend ourselves against terrorist attacks, and when that happens terrorists will take over our country. Therefore, gun control laws will cause us to lose our country to terrorists.

See Dr. Fallacy in the comic below try to get away with this fallacy. Fortunately, Captain Logic saves logic and saves the day!

In this example, Dr. Fallacy is following a slippery slope to get to the point that any kind of gun regulation will lead to terrorists taking over the country. The series of events is extremely improbable, and we simply can’t make claims like this and be taken seriously in our arguments.

Of course, this example is extreme, but we do need to make sure, if we are creating a line of reasoning in terms of events leading to other events, that we aren’t falling into a slippery slope fallacy.

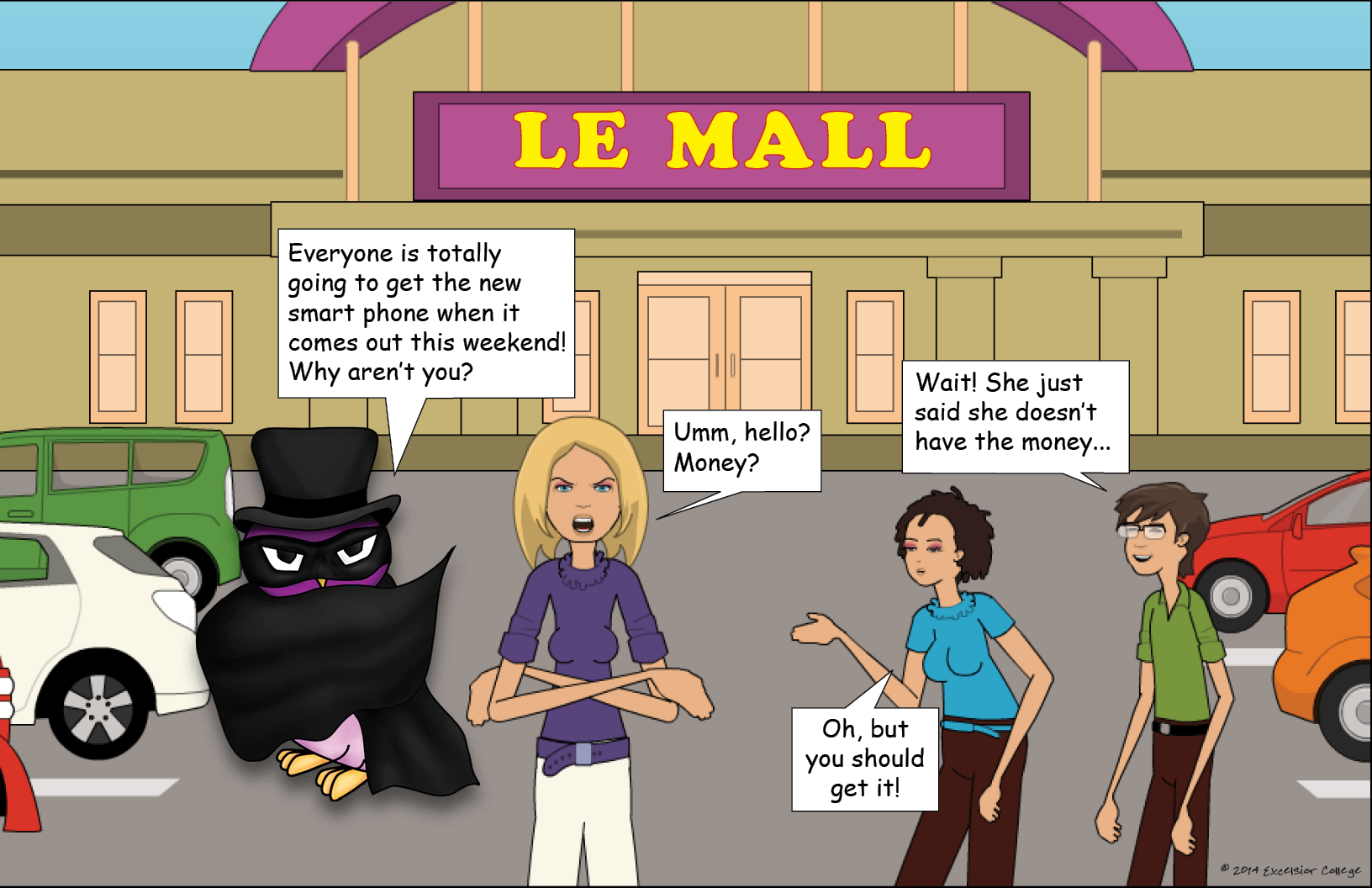

Bandwagon Fallacy

The bandwagon fallacy is also sometimes called the appeal to common belief or appeal to the masses because it’s all about getting people to do or think something because “everyone else is doing it” or “everything else thinks this.”

Everyone is going to get the new smart phone when it comes out this weekend. Why aren’t you?

In the comic below, Dr. Fallacy tries to persuade people using this type of fallacy.

Of course, the problem with this fallacy is not everyone is actually doing this, but there is another problem that’s important to point out. Just because a lot of people think something or do something does not mean it’s right or good to do. For example, in the 16th century, most people believed the earth was the center of the universe; of course, believing that did not make it true.

You want to be careful to avoid this fallacy, as it’s easy to fall into this kind of thinking. Think about what your parents asked you when you insisted that “everyone” was doing something that you were not getting to do: “If everyone of your friends jumped off of a cliff, would you?” It’s important to fight the urge to fall into a bandwagon fallacy.

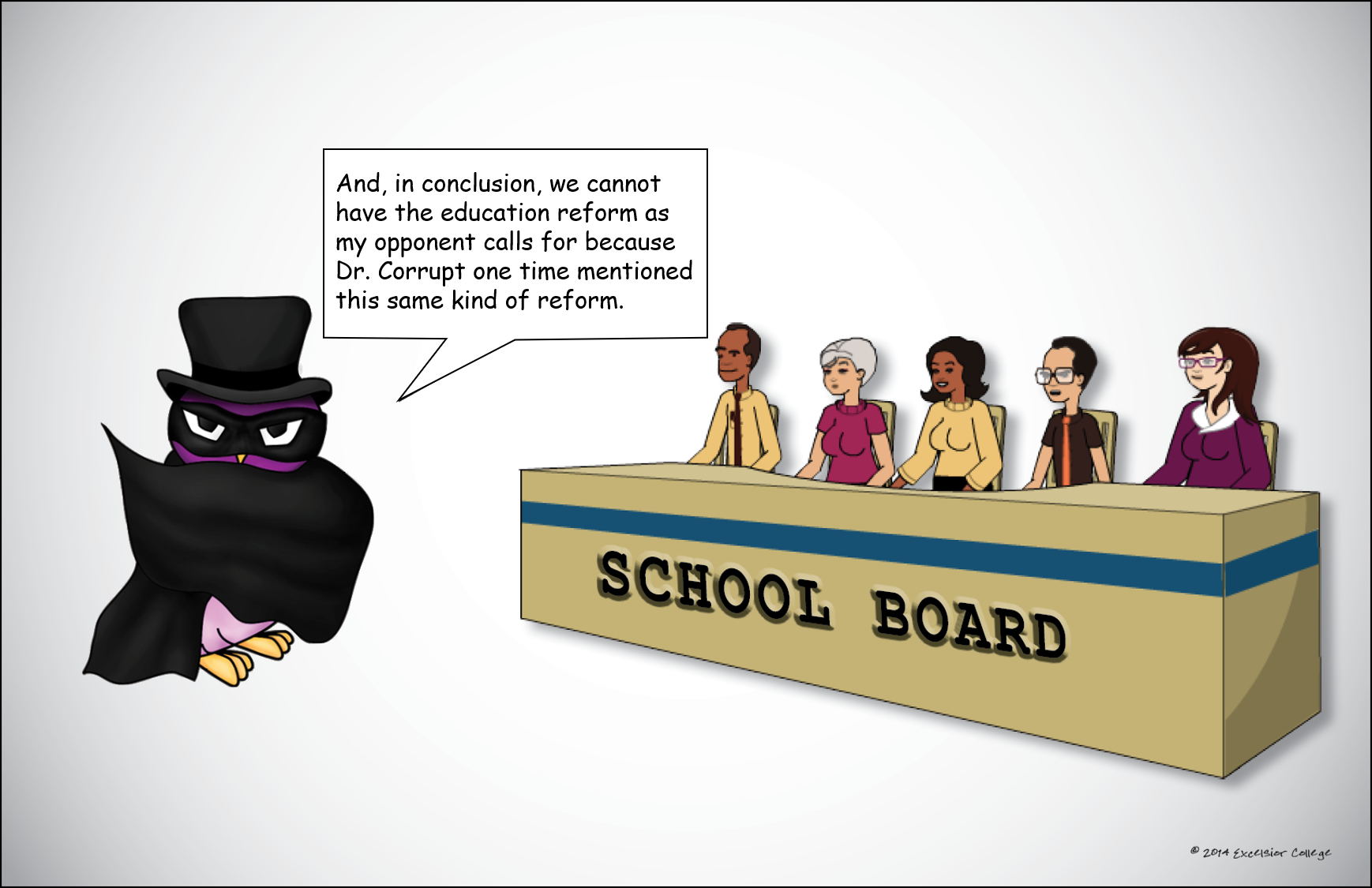

Guilt by Association Fallacy

A guilt by association fallacy occurs when someone connects an opponent to a demonized group of people or to a bad person in order to discredit his or her argument. The idea is that the person is “guilty” by simply being similar to this “bad” group and, therefore, should not be listened to about anything.

We cannot have the educational reform that my opponent calls for because Dr. Corrupt has also mentioned this kind of educational reform.

See Dr. Fallacy use this fallacy by associating his opponent with someone named Dr. Corrupt. Clearly, this person isn’t someone to be associated with. Thankfully, Captain Logic OWL points out this flawed logic to the school board.

Here, we don’t see what issues Dr. Fallacy has with the educational reform plan, as this isn’t addressed in the fallacy. Instead of dealing with the issue, this person tries to just dismiss the point by connecting his or her opponent’s ideas with the ideas of a person who the audience wouldn’t believe.

This is problematic, of course, because we don’t deal with the issue at hand. Plus, just because “Dr. Corrupt” thinks the same thing or something similar doesn’t mean we should automatically dismiss it. We need to look more closely at the issue at hand, and it seems like the person using this fallacy doesn’t want us to.

Since Dr. Fallacy is once again thwarted by Captain Logic, this may, indeed, be his last fallacy!

Putting It All Together

It’s time to see the fallacies in action! In the videos below, you will see how one student, Mateo, engages in the process of locating sources but struggles to find sources without fallacies. Watch as he applies what he has learned about logical fallacies to his research process. Click on the first video to see Mateo’s assignment and learn about his goals. Then, click on the video that follows in order to see what fallacies Mateo encountered in his sources. When you’re finished, select the activity at the end of this page to see how well you can locate logical fallacies in sources.

Analyze This

This material was developed by Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License . You are free to use, adapt, and/or share this material as long as you properly attribute. Please keep this information on materials you use, adapt, and/or share for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

Understanding Common Logical Fallacies (and How to Avoid Them)

June 13, 2023

Logical fallacies are common errors in reasoning that can undermine the credibility and validity of arguments. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore what these fallacies are, why understanding them is important, and how you can avoid falling into their traps. Additionally, we’ll introduce Yoodli , an AI speech and communication coach, and discuss how it can assist you in identifying and avoiding logical fallacies in your speeches, presentations, and everyday conversations.

What Are Logical Fallacies?

Logical fallacies are flaws in reasoning that occur when arguments are structurally or content-wise flawed, leading to unreliable or invalid conclusions. They can appear in various forms, such as errors in logic, deceptive tactics, or manipulative techniques. By familiarizing yourself with common fallacies, you can both strengthen your critical thinking skills and engage in more effective communication.

The Importance of Understanding Logical Fallacies

Understanding fallacies is essential for several reasons. Firstly, it enables you to evaluate the soundness and validity of arguments presented to you, whether in professional discussions, political debates, or everyday conversations. By recognizing fallacious reasoning, you can avoid being swayed by weak or misleading arguments.

Secondly, knowing these fallacies helps you construct stronger and more persuasive arguments yourself. By avoiding fallacies, you both enhance the credibility of your claims and increase the chances of effectively communicating your ideas to others.

Yoodli: Your AI Speech and Communication Coach

Yoodli is an advanced AI speech and communication coach designed to help you improve your speaking skills as well as avoid common pitfalls like logical fallacies. One remarkable feature of Yoodli is its ability to generate interactive transcripts from your uploaded or recorded videos. This feature allows you to review your speech or presentation and spot potential gaps in reasoning without the need to listen to the entire recording repeatedly.

Moreover, Yoodli offers smart re-wording suggestions, helping you refine your language and express your ideas more effectively. By utilizing Yoodli’s AI-powered capabilities, you can enhance your overall critical thinking skills. This will help you strengthen your arguments and also become a more persuasive communicator.

Types of Common Logical Fallacies + Examples

Logical fallacies can take many forms, each with its own distinctive characteristics and pitfalls. Here are some common types of logical fallacies along with examples to help you recognize them in arguments:

1. Ad Hominem Fallacy

This fallacy involves attacking the person making the argument instead of addressing the argument itself. For example:

- “John’s proposal for improving the healthcare system shouldn’t be considered because he’s not a doctor.”

2. Straw Man Fallacy

A straw man fallacy occurs when someone misrepresents their opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack. For example:

- “My opponent wants to cut defense spending. This means they don’t care about the safety of our country.”

3. Appeal to Authority Fallacy

This fallacy involves relying on the opinion or authority of an individual as evidence for the truth of an argument. For example:

- “Dr. Smith, a famous scientist, says that climate change is a hoax. Therefore, it must be untrue.”

4. Slippery Slope Fallacy

The slippery slope fallacy assumes that a small action will lead to extreme and unlikely consequences. For example:

- “If we allow same-sex marriage, it will pave the way for people to marry animals.”

5. False Cause Fallacy

This fallacy assumes causation based on correlation without sufficient evidence. For example:

- “Since I started carrying a lucky charm, I’ve been winning all my basketball games. Therefore, the charm must be bringing me luck.”

These are just a few examples of the many types of logical fallacies that can arise in arguments. By familiarizing yourself with these fallacies, you’ll be better equipped to spot them and build more robust and logical arguments.

How to Avoid Logical Fallacies: 5 Tips

To avoid logical fallacies, it’s important to not only be aware of their various forms but also learn how to identify them in arguments. Here are some key strategies to help you navigate through the pitfalls of faulty reasoning:

1. Educate Yourself

Familiarize yourself with different types of common fallacies by studying comprehensive lists and examples. Understand their underlying principles and recognize the patterns in which they appear. This knowledge will empower you to spot fallacious reasoning more effectively.

2. Practice Critical Thinking

Develop your critical thinking skills by analyzing arguments and claims more critically. Ask questions, seek evidence, and evaluate the reasoning behind the assertions made. This practice will help you identify flaws and weaknesses in reasoning, including logical fallacies.

3. Challenge Assumptions

Don’t accept claims at face value. Challenge assumptions and scrutinize the evidence provided. Look for logical inconsistencies, unsupported assertions, or manipulative tactics that may indicate the presence of fallacies.

4. Seek Diverse Perspectives

Engage with a variety of perspectives and seek constructive debates. Exposing yourself to different viewpoints will sharpen your ability to identify fallacies and strengthen your reasoning abilities.

5. Use Yoodli for Feedback and Improvement

Utilize Yoodli’s AI speech and communication coach functionalities to receive feedback on your speeches, presentations, or logical arguments. Take advantage of the interactive transcripts and smart re-wording suggestions to identify potential logical fallacies and refine your communication style.

Understanding logical fallacies is crucial for effective communication and critical thinking. By familiarizing yourself with common fallacies, practicing critical analysis, and utilizing tools like Yoodli, you can avoid falling into the traps of faulty reasoning. Enhancing your ability to recognize and address these fallacies will elevate the quality of your arguments and make you a more persuasive and informed communicator.

Remember, by striving for logical coherence and sound reasoning, you can navigate discussions, debates, and everyday conversations with clarity and credibility.

Q: What are some common examples of logical fallacies?

A: There are several common logical fallacies, including ad hominem attacks (attacking the person instead of their argument), straw man arguments (misrepresenting an opponent’s position), slippery slope fallacy (claiming a small action will lead to extreme consequences), and false cause fallacy (assuming causation based on correlation). These are just a few examples, and there are many more.

Q: How do I politely point out a logical fallacy in someone’s argument?

A: When addressing a logical fallacy, it’s important to focus on the issue at hand rather than attacking the person. Politely and respectfully point out the flaw in their reasoning, providing clear explanations and supporting evidence. This approach encourages constructive dialogue and promotes a better understanding of the topic.

Q: Can logical fallacies be unintentional?

A: Yes, logical fallacies can be unintentional. Often, people may not be aware of the flaws in their reasoning or may fall into cognitive biases that lead to faulty arguments. It’s crucial to approach discussions with an open mind and be willing to recognize and correct any contradictions in our own thinking.

Q: Is it possible to avoid all logical fallacies?

A: While it’s challenging to completely avoid all logical fallacies, becoming familiar with common lapses in reasoning and practicing critical thinking can significantly reduce their occurrence. The key is to develop a habit of questioning arguments, evaluating evidence, and striving for logical coherence in our own reasoning.

Q: Can Yoodli help me identify logical fallacies in my own speeches or presentations?

A: Yes, Yoodli’s AI speech and communication coach functionalities can assist you in identifying potential logical fallacies in your speeches or presentations. By generating interactive transcripts and providing smart re-wording suggestions, Yoodli enables you to review your content and spot any fallacious reasoning, allowing you to refine your arguments and enhance your communication skills.

Q: Are logical fallacies always deliberate attempts to deceive?