Kindlepreneur

Book Marketing for Self-Publishing Authors

Home / Book Writing / How to Format Dialogue (2024 Rules): The Ultimate Guide for Authors

How to Format Dialogue (2024 Rules): The Ultimate Guide for Authors

Dialogue is one of the most ever-present components of writing, especially in fiction. Yet even experienced authors sometimes format dialogue incorrectly.

There are so many rules, standards, and recommendations to format dialogue that it can be easy to get lost and not know what to do.

Thankfully, this article will help you know exactly what to do when formatting and writing dialogue, and I’ll even mention a tool that will make the whole process a lot easier, but more on that later.

- The basic rules for good dialogue

- Grammar rules for effective dialogue

- The difference between curly and straight quotes

- Common stylistic choices

- And other recommendations

Table of contents

- Basic Dialogue Rules

- 1. The Correct Use of Quotation Marks

- 2. The Correct Use of Dialogue Tags

- 3. The Correct Use of Question and Exclamation Marks

- 4. The Correct Use Of Em-Dashes And Ellipses

- 5. Capitalization Rules

- 6. Breaking Dialogue Into Multiple Paragraphs

- 7. Using Quotation Marks With Direct Dialogue vs Indirect Dialogue

- Using Quotation Marks With Direct Dialogue vs Reported Dialogue

- Keyboard Shortcuts for PC or Windows

- Keyboard Shortcuts for Mac

- Formatting Quotes with Atticus

- Best Practice: Dialogue Tags

- If dialogue is interrupted by a tag and action…

- If dialogue is interrupted by just an action…

- Best Practices: She Said vs. Said She

- Best Practice: Using Beats to Break up Your Dialogue

- 1. Italicized With a Tag

- 2. Italicized Without a Tag

- 3. Not Italicized

- 1. Make It Clear Who Is Speaking

- 2. Focus on Character Voice

- 3. Don't Overdo Your Character Voice

- 4. Don't Info-Dump with Dialogue

- 5. Avoid Repetitive Dialogue Tags

- Final Thoughts on Formatting Dialogue

Why You Should Trust Me

So I've been writing and formatting books for a long time. 10+ years as of this writing.

But I actually found formatting to be a huge pain, which is why I actually created my own formatting software that solved all my problems. I called it Atticus.

But this isn't meant to be a sales pitch. I just want to make sure it's clear that I know what I'm talking about. The amount of research that went into not only formatting my own books, but also creating a formatting software is huge.

I researched everything, from tiny margin requirements, to the specific type of quotes to use (curly or straight, it makes a difference).

And yes, of course, that includes how to format dialogue.

So if all that makes sense, hopefully you'll come along with me as show you everything I've learned.

There are some basic rules that most people are aware of, but still need to be mentioned in an article about formatting dialogue.

The following are some of the very basic instructions you will need to follow:

- New speaker, new paragraph: whenever a new person speaks, you should start a new paragraph. This is true, even if your character is alone and talking out loud, or even if all they say is one word.

- Indent each paragraph: as with any paragraph, you should indent it. There are small exceptions, such as at the beginning of a chapter or scene break.

- Quotation marks go around the dialogue: use quotation marks at the beginning and end of your character's dialogue. Any punctuation that is part of the dialogue should be kept within the quotes.

Now that you have these basics in mind, let's dive into the specific rules of grammar and punctuation for formatting dialogue.

Dialogue Punctuation

To punctuate dialogue correctly, there are a few rules you should know:

- The correct use of quotation marks

- The correct use of dialogue tags

- The correct use of question and exclamation marks

- The correct use of em-dashes and ellipses

- Capitalization rules

- Breaking dialogue into multiple paragraphs

- Using quotation marks with direct dialogue versus indirect dialogue

- Using quotation marks with direct dialogue vs reported dialogue

Let's dive into each of these one by one…

For American writing, you will use a set of quotation marks (” “). These are placed directly before and after the dialogue spoken by your character.

Furthermore, the quotation marks are placed around any punctuation, such as a comma, question mark, or exclamation mark.

Example:

“I love writing books!” said John.

You can use the same set of quotation marks around more than one sentence.

Example:

“I love writing books! It makes me feel so accomplished.”

Note: the double quote is used heavily in American writing and in some other parts of the world, with single quotes used to quote dialogue within a larger quote. However these roles are often reversed outside of American writing, and some cultures even use angle brackets instead (<< >>).

A dialogue tag is simply a phrase at the beginning or end of your dialogue that tells us who is speaking. Dialogue tags are optional, but should be used when there are multiple people speaking and it is not clear which dialogue belongs to whom.

Your dialogue tag should use a comma to separate itself from the dialogue. If your dialogue tag appears at the beginning of your quote, the comma should appear after the dialogue tag and before your first quotation mark. If your dialogue tag is after your quote, the comma should appear after the dialogue, but before the closing quotation mark.

John said, “I love to write books.”

“I love to write books,” said John.

If a sentence of dialogue is interrupted by the dialogue tag, then you should use two commas that follow the above rules.

“I love to write books,” said John, “every single day.”

If you are using a question or exclamation mark, those are placed within the quotation marks, just as a comma would be.

“You like to write books?”

If you are following up the dialogue with a dialogue tag, you do not need to capitalize the first word of the dialogue tag.

“You like to write books?” said Lucy.

“You like to write books?” Said Lucy.

Both em-dashes and ellipses are used to show incomplete dialogue, but their uses vary.

Em-dashes should be used when dialogue is interrupted by someone else's dialogue, or any other interruption that leads to an abrupt ending.

Note that the em-dash is contained within the quotation marks, and replaces any punctuation. If the em-dash appears at the start of the quote, the following word should not be capitalized.

“Have I ever told you—”

“Yes, yes you have.”

“—that I love writing books?”

Ellipses are used when the dialogue trails off, but there is not an obvious interruption.

“What was I saying just…

In most cases, you should capitalize the first word of your dialogue. This is true, even if the dialogue does not technically begin the sentence.

John said, “But I love to write books!”

John said, “but I love to write books!”

The exception to this is if you are starting in the middle of your character's sentence, such as after an em-dash, or anytime the first quoted word is not the first word of the character's full sentence.

Lucy rolled her eyes, ready to hear again just how much John “loved to write books.”

If you have especially long dialogue, you might want to divide that dialogue into multiple paragraphs.

When this happens, place the first quotation mark at the beginning of the dialogue, but do not place a quotation mark at the end of that first paragraph.

You also place a quotation mark at the beginning of each subsequent paragraph until the dialogue ends. The last paragraph of dialogue has a quotation mark at the beginning and the end.

John said, “I can't explain to you why I love writing books so much. Perhaps it has something to do with my childhood. I always loved writing books as a child and making up stories . My mom told me I should be playing outside, but I preferred writing.

“Or maybe it was in college when I started learning the rules of good creative writing and saw my characters come to life in a way that I had never seen in my youth. It excited me more.

“Or maybe I'm just weird.”

Before I get into the specifics of how to use quotation marks with direct dialogue versus indirect dialogue, you have to understand what each is.

Direct dialogue is written between inverted commas or quotes. This is someone actually speaking the words you’ve written down. It looks like this:

“Hello, I like to write books,” he said.

Indirect dialogue is basically you telling someone about what another person said.

He said hello and that he liked to write books.

Note that no quotation marks are required because it’s not a direct quote — the speaker is paraphrasing.

However, most of the formatting and punctuation tips I work with in this article pertain to direct dialogue.

Besides direct dialogue and indirect dialogue, I also have reported dialogue.

Reported dialogue is when one line of dialogue is quoting something else.

With American usage of quotation marks, I place double quotation marks around the direct dialogue (a.k.a. the main quote), with single quotation marks around the reported dialogue (a.k.a. the quote within the quote).

“I was talking to John the other day, and he kept saying ‘I love writing books' all the time,” said Lucy.

Note that this is common for American writing, and is often reversed outside of North America. Check your local style guides to know exactly how to embed one quote within another.

Curly Quotes or Straight Quotes?

Some authors don't even realize this, but there is a big difference between straight quotes and curly quotes.

Straight quotes do not bend inward, but remain straight. They are identical, whether they are located at the beginning or end of your quote.

John said, “I just like to write books, okay?”

By default, most keyboards use straight quotes instead of smart quotes. It is also the standard for web-based writing, since it simplifies the HTML needed to render a webpage (notice that most quotes in this article are straight quotes).

Curly quotes (sometimes called smart quotes) curve inward toward the line of dialogue that they encapsulate.

John said, “I just like to write books, okay?”

Curly quotes are more common in publishing, fiction, and are generally considered the standard when doing dialogue.

How to Change Straight Quotes to Curly Quotes

Since most keyboards use straight quotes, and is the default for many programs, you will have to change them to smart quotes manually.

While some programs have this functionality, you can also use keyboard shortcuts. For example:

To use keyboard shortcuts for PC, hold down the alt key, then type the four-digit code using your number pad:

- Opening double quote shortcut: alt 0147

- Closing double quote shortcut: alt 0148

- Opening single quote shortcut: alt 0145

- Closing single quote shortcut: alt 0146

Note that you must type these numbers in with your number pad, and not the top row of numbers on your keyboard. The top row will not work.

The same process applies here, but the commands are slightly different. With a Mac, hold down the different keys shown here:

- Opening double quote shortcut: Option + [

- Closing double quote shortcut: Option + Shift + [

- Opening single quote shortcut: Option + ]

- Closing single quote shortcut: Option + Shift + ]

The downside to using the short codes is that it can become extremely tedious, especially if you have to go through your entire book and replace all of the quotes.

Thankfully, there is an option to make this a lot easier…

When you use Atticus, you can automatically swap your straight quotes for curly quotes with the touch of a button.

To do this, look on the top writing toolbar, and you will see two icons on the right.

If you click the button labeled “Apply Smart Quotes”, it will give you the following pop-up:

Do this for each of your chapters, and you should see the little red warning icon change to a green icon, indicating that your entire book is free of straight quotes.

This saves you a ton of hassle, it is by far the easiest way to improve your quotes in a writing or formatting program.

We've already talked about the grammatical rules for dialogue tags above, but let's talk a little more about, because there are ways to use dialogue tags that are grammatically correct, but not great from a stylistic standpoint.

For example, should you use words other than “said” for your dialogue tag?

Technically, you can do this. You can use many words as a dialogue tag. For example:

“You like to write books?” asked Lucy.

“You like to write books?” scoffed Lucy.

“You like to write books?” snickered Lucy.

“You like to write books?” intoned Lucy.

In this case, I have used alternative dialogue tags in each example. It's common for newer writers to think that mixing up the dialogue tags like this is a good thing, but this is not the case.

In fact, most authors agree the best practice is to use just “said” and “asked”.

You can use other words on occasion (I sometimes use “clarified”, “shouted”, or “whispered”), but these should be rare.

The reason for this is simple: readers expect to see the words “said” and “asked”. Their mind brushes right over it, taking the necessary attribution data, and nothing else. Using “said” over and over again will not seem repetitive, because it is expected.

Using unusual dialogue tags is a quick way to draw the reader out of the book.

Best Practice: Formatting Interruptions

I’ve talked, briefly, about em-dashes and ellipses above, but there are a few other considerations to make when formatting dialogue interruptions.

You can format it in two ways. First of all:

“I love writing books,” John said, rubbing his hands together, “but I don’t like editing them that much.”

In this first example, you write your starting dialogue, tag, and action as usual, but instead of finishing the sentence with a period, you place a comma, open a new quotation mark and continue the sentence with a conjunction. At the end of that sentence, you’d use a period and close the speech.

But you can also format that interruption by separating the spoken pieces into two separate sentences as follows:

“I love writing books,” John said, rubbing his hands together. “But I don’t like editing them that much.”

Here, the sentence ends after John has rubbed his hands together. Because of that, when you start your new line of dialogue, you format it with a capitalized ‘But’ and end it with a period.

Say your speaker is being erratic, or just doing something that would interrupt his speech, like taking a sip of water or coughing uncontrollably, you wouldn’t have a well-planned and inserted interruption. The text would look broken because the dialogue is being broken by the action.

You’d format that as follows:

“I love writing books”–John took a sip of water–“but I’m not a fan of editing them.”

Note: The em-dashes are outside of the dialogue for this type of formatting.

You might be surprised to learn that there is a best practice for the word order for your dialogue tags.

For example, should you say “Lucy said” or “said Lucy”?

It may be common for you to guess that “said Lucy” is an acceptable practice (at least I did), but while this is technically grammatically correct, it is actually discouraged.

The correct way to format this is “Lucy said”.

Think of it this way, would it feel more natural to say “she said” or “said she”? Since “she said” is more natural with pronouns, the logic is that “Lucy said” is the superior form of dialogue tag.

Instead of dialogue tags, one alternative that you can use are beats.

Beats are small actions to give to your characters, so it doesn't sound like the dialogue is being spoken between two talking heads in a void.

It helps to move the story along, creates a sense of realism, and gives you a chance to reduce the number of dialogue tags that you use, without confusing the reader.

“I love to write books!” John sat at the keyboard and cracked his knuckles.

You can also add a beat to your dialogue tag.

“I love to write books!” said John, then sat at the keyboard and cracked his knuckles.

Additionally, you can use a beat to interrupt the flow of dialogue. This is even encouraged at times, because it can create diversity in how you use your dialogue.

“I love to write books!” John sat at the keyboard and cracked his knuckles. “But I don't like editing them as much.”

Best Practice: Formatting Inner Dialogue

When you are formatting internal dialogue (particularly when writing from 3rd person point of view), there are three ways that you can format it.

It’s common to see inner dialogue treated the same as quoted dialogue, but with the entire inner dialogue italicized instead of using quotation marks.

I just love to write books, John thought. Why can’t Lucy understand this?

Likewise, you can often leave out the tag all together, as the reader is able to understand by the italics that this is a thought. However, you might want to accompany this with a beat.

John sat at his desk. I just love to write books. Why can’t Lucy understand this?

If you are writing from a deeper point of view, you might not need italics or a tag. This is especially common when writing in first-person point of view, where literally all of the prose represents that person’s thoughts.

I sat at my desk. I just love to write books. Why can’t Lucy understand this?

Other Tips for Formatting Dialogue

In addition to the above, there are a few miscellaneous tips that I would like to share:

When using dialogue, you never want the reader to be confused as to who is saying the dialogue. There are a couple of ways to do this.

- Use dialogue tags effectively

- Never leave out dialogue tags unless you only have two people, and it is obvious which one is speaking

- Use beats appropriately

Each character should have a unique way of speaking.

A good way to practice different voices is to record a conversation, such as around the dinner table, and transcribe it. Notice how everyone uses a different “flow” to our sentences, or have favorite words that I like to use.

Do they speak in short, choppy sentences? Or are they more prone to elegant, long-winded paragraphs?

Another great exercise is to write a conversation with two people, and don't use dialogue tags. Instead, try to make how they are speaking make it obvious who is actually talking.

Despite my recommendation above, it is possible to overdo character voice.

Examples of this include:

- Overdoing a heavy accent, where every word of their dialogue is spelled slightly different to convey the dialect.

- Including curse words in every other sentence, even if this is realistically based on someone you know.

- Including a lot of “ums” and “uhs” in your sentence. While these are common in real life, they can dramatically pull your reader out of the story.

While it is okay for the character to explain some of what is going on in their dialogue, you have to be careful with this.

Above all, make sure your dialogue naturally fits the character in the scene. Info dumping can easily lead to “Maid and Butler dialogue”, where it feels like the characters just talking for the benefit of the reader, and not for the actual situation they are in.

While it is important to use “said” and “asked” the most when doing your dialogue tags, there are other ways that you should use to diversify your tags, such as:

- Use beats instead

- Use dialogue tags before, after, and in the middle of your dialogue

- Remove dialogue tags when you have a back-and-forth conversation between two people and it is obvious who is saying what

This is not just relevant for dialogue tags, but also for your dialogue styles. If you have had three lines of dialogue in a row that all placed your dialogue tag in the middle of the dialogue, then you might want to change things up a bit.

While it is easy to get overwhelmed with all of the little tips and tricks to formatting dialogue, once you have enough practice, it becomes second nature.

Additionally, a tool like Atticus can make some of the technical bits so much easier, such as changing your street quotes to curly quotes.

In addition to formatting dialogue, Atticus is the number one software for writing and formatting a book. Plus, unlike other leading formatting software is, it is available on all platforms, and costs over $100 less than the leading alternative.

Dave Chesson

When I’m not sipping tea with princesses or lightsaber dueling with little Jedi, I’m a book marketing nut. Having consulted multiple publishing companies and NYT best-selling authors, I created Kindlepreneur to help authors sell more books. I’ve even been called “The Kindlepreneur” by Amazon publicly, and I’m here to help you with your author journey.

Related Posts

How to format a book for ingramspark: complete guide (2024), how to make a table of contents in google docs, how to format a book in atticus, sell more books on amazon, how to title a book checklist.

Titling your book can be hard…really hard. As you go through choosing your book title, use this checklist as your guide and make sure you have a title that will sell!

Join the community

Join 111,585 other authors who receive weekly emails from us to help them make more money selling books.

How to Format Dialogue: Complete Guide

Dialogue formatting matters. Whether you’re working on an essay, novel, or any other form of creative writing. Perfectly formatted dialogue makes your work more readable and engaging for the audience.

In this article, you’ll learn the dialogue formatting rules. Also, we’ll share examples of dialogue in essays for you to see the details.

What is a Dialogue Format?

Dialogue format is a writing form authors use to present characters' communication. It's common for play scripts, literature works, and other forms of storytelling.

A good format helps the audience understand who is speaking and what they say. It makes the communication clear and enjoyable. In dialogue writing, we follow the basic grammar rules like punctuation and capitalization. They help us illustrate the speaker’s ideas.

General Rules to Follow When Formatting a Dialogue

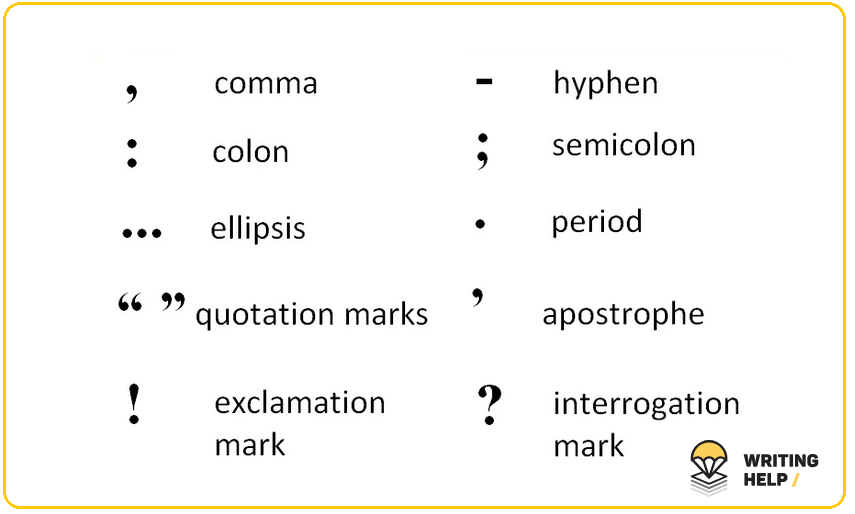

Dialogue writing is an essential skill for both professionals and scholars . It shows your ability to express the issues and ideas of other people in different setups. The core rules of formatting are about punctuation. So, below is a quick reminder on punctuation marks’ names:

And now, to practice.

Please follow these rules for proper dialogue formatting:

- Use quotation marks. Enclose the speaker’s words in double quotations. It helps readers distinguish between a character’s speech and a narrator’s comments.

- Place punctuation inside quotation marks. All punctuation like commas, exclamations, or interrogation marks, go inside the double quotations.

- Keep dialogue tags behind quotation marks. A dialogue tag is (1) words framing direct speech to convey the context and emotions of a conversation. For example, in (“I can’t believe this is you,” she replied.), the dialogue tag is “she replied.”

- Use an ellipsis or em-dashes for pauses or interruptions. To show interruptions or pauses, end phrases with ellipses inside quotations. Em-dashes go outside quotations. No other extra marks are necessary here.

- Remember a character’s voice. Ensure that each character’s phrases reflect their background and personality.

5 More Rules to Know (+ Examples of Dialogue)

For proper formatting of dialogue in writing, stick to the following rules:

1. Each speaker’s saying comes in a new paragraph

Begin a new paragraph whenever a new character starts speaking. It allows you to differentiate speakers and make their conversation look more organized. (2)

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” — from Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

2. Separate dialogue tags with commas

When using dialogue tags ( e.g., “she said,” “he replied,”), separate them with commas.

For example:

“You’ve got to do something right now , ” Aaron said , “Mom is really hurting. She says you have to drive her to the hospital.” “Actually, Dad , ” said Caleb, sidling in with his catalog , “There’s someplace you can drive me, too.” “No, Caleb.” — from The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

3. When quoting within dialogue, place single quotes

If a character cites somebody or something while speaking, we call it a reported dialogue. In this case, use single quotations within double ones you place for a direct speech. It will help readers see that it’s a quote.

John started to cry. “When you said, ‘I never wanted to meet you again in my life!’ It hurts my feelings.”

4. You can divide a character’s long speech into paragraphs

Dialogue writing is different when a person speaks for a longer time. It’s fine to divide it into shorter paragraphs. Ensure the proper quotation marks placing:

The first quotation mark goes at the beginning of the dialogue. Each later paragraph also starts with it until that direct speech ends.

The second quotation mark — the one “closing” the monologue — goes at the dialogue’s end.

Josphat took a deep breath and began. “ Here’s the things about lions. They’re dangerous creatures. They only know how to kill. Have you ever seen a lion in an open area? Probably not. Because if you had you’d be dead now. “ I saw a lion once. I was fetching firewood to cook lunch. All of a sudden I found myself face to face with a lion. My heart stopped. I knew it was my end on earth. If it wasn’t the poachers we wouldn’t be having this talk. ”

Yet, you can keep a long text as a whole by adding some context with dialogue tags. Like here:

As you can see, there’s no quotation mark at the end of the paragraph in red. It’s because the next “Ha! ha!” paragraph continues the character’s speech.

5. Use action beats

Describe actions to provide context and keep readers engaged. Help them “hear” your characters. Punctuation also helps here: exclamation (!) or interrogation with exclamations (?!) demonstrate the corresponding tone of your narrative.

He slammed the door and shouted , “I can’t believe you did that ! “

Mistakes to Avoid When Formatting Dialogue

A good dialogue is a powerful instrument for a writer to show the character’s nature to the audience. Below are the mistakes to avoid in formatting if you want to reach that goal.

So, please don’t :

- Allow characters to speak for too long. Writing long paragraphs will bore the reader, making them skip through your speech. Short but sweet talk is the best. When writing, aim to be brief, dynamic, and purposeful. If your character speaks too much, generating opinion essays , ensure this speech makes sense and serves a bigger purpose.

- Overburden dialogue with exposition. Avoid telling the story background or building sophisticated words in your characters’ speeches. Instead, reveal the narrative content in small bursts and blend it around the rest of the prose. Convey it through your character’s actions and thoughts rather than summaries and explanations.

- Create rhetorical flourishes. Make your characters sound natural. Let them speak the way they’d do if they were real people. Consider their age, profession, and cultural background — and choose lexical items that fit them most.

- Use repetitive dialogue tags. Constant “he asked” and “she said” sounds monotonous. Diversify your tags: use power verbs, synonyms, and dialogue beats.

Frequently Asked Questions by Students

How to format dialogue in an essay.

Formatting a dialogue in an essay is tricky for most students. Here’s how to do it: Enclose the speaker’s words with double quotations and start every other character’s line from a new paragraph. Stick to the citation styles like APA or MLA to ensure credibility.

How to format dialogue in a novel?

A dialogue in a novel follows all the standard rules for clarity and readability. Ensure to use attributions, quotation marks, and paragraph format. It makes your dialogue flow, grabbing the reader’s attention.

How to format dialogue in a book?

Dialogue formatting in a book is critical for storytelling. It helps the audience distinguish the hero’s words. Follow the general rules we’ve discussed above:

Use double quotations and isolate dialogue tags with commas. Remember to place the discussion in blocks for better readability.

How to format dialogue between two characters?

A two-character dialogue offers the best way to prove successful formatting skills. Ensure you use action beats, quotations, and attribution tags. It allows readers to follow the conversation and understand it better.

What is the purpose of dialogue in a narrative essay?

Dialogue writing is the exchange of views between two or more people to reach a consensus. It reveals the character’s attitude and argumentation. Last but not least, it helps convey the descriptive nature of your narrative essay.

References:

- https://valenciacollege.edu/students/learning-support/winter-park/communications/documents/WritingDialogueCSSCTipSheet_Revised_.pdf

- https://www.ursinus.edu/live/files/1158-formatting-dialogue

- Essay samples

- Essay writing

- Writing tips

Recent Posts

- Writing the “Why Should Abortion Be Made Legal” Essay: Sample and Tips

- 3 Examples of Enduring Issue Essays to Write Yours Like a Pro

- Writing Essay on Friendship: 3 Samples to Get Inspired

- How to Structure a Leadership Essay (Samples to Consider)

- What Is Nursing Essay, and How to Write It Like a Pro

Learning Materials

Mastering how to write a conversation in an essay.

Updated: Jul 5, 2024

Ever felt your essay lacked that spark to truly immerse the reader? Writing conversations in essays can be tricky, balancing authenticity with academic rigor. To write a conversation effectively, use dialogue to add depth, emotional resonance, or clarify the content, ensuring it captures attention and feels realistic. In this blog post, we'll explore how to skillfully integrate dialogue into your essays, from understanding its purpose to mastering formatting rules like APA and MLA.

Understanding Dialogue in Essays

Dialogue in essays is not just about replicating spoken words but about enhancing the narrative and providing depth to the characters and the situation. It serves several key purposes: it can advance the plot, reveal hidden motives, or highlight conflicts. In narrative essays, dialogue breathes life into characters, making them more relatable and vivid to the reader. Similarly, in argumentative essays, it can illustrate points more dynamically and engage the reader more effectively than a simple exposition might.

The importance of dialogue in essays cannot be overstated. It transforms the reading experience by adding layers of meaning and emotion that pure descriptive text cannot achieve. For instance, dialogue can:

- Showcase a character’s personality and speech patterns,

- Build tension or suspense through interactions,

- Provide insights into the plot without a direct narration. Thus, mastering the use of dialogue is essential for any student or writer aiming to craft compelling and persuasive essays.

Exploring Types of Dialogue for Essays

In essays, dialogue can be categorized into three main types: direct , indirect , and inner dialogue. Direct dialogue involves the exact words spoken by characters, enclosed in quotation marks, providing a vivid sense of conversation. It's particularly effective in narrative essays where capturing the immediacy of an interaction is crucial. Indirect dialogue , on the other hand, paraphrases the spoken words without quotation marks, often used to summarize conversations or to blend dialogue into a descriptive passage, making it less disruptive and maintaining a more formal tone suitable for academic or analytical writing.

Inner dialogue reflects the thoughts or internal conversations of a character, offering a glimpse into their motivations and emotional states. This type of dialogue is usually not marked by quotation marks but may be italicized to differentiate it from external dialogue. Each type of dialogue serves a unique purpose in an essay:

- Direct dialogue adds realism and immediacy,

- Indirect dialogue smooths narrative flow while conveying essential information,

- Inner dialogue deepens character development and emotional engagement. Understanding when and how to use each type can greatly enhance the effectiveness of your writing, making your essays more dynamic and engaging.

Structuring Dialogue in Essays

Structuring dialogue effectively in an essay is crucial for maintaining clarity and ensuring a smooth flow of the narrative. When integrating dialogue, it's important to consider its placement within the context of your essay. Begin a new paragraph each time a different character speaks, which helps the reader easily follow the conversation. Additionally, ensure that each piece of dialogue serves a purpose, whether it's pushing the narrative forward, revealing character traits, or providing necessary information. Avoid cluttering your essay with unnecessary dialogue that does not enhance your argument or story.

To maintain a clear structure, use dialogue tags judiciously. These are phrases like 'he said' or 'she asked' that attribute the spoken words to a character. While necessary for clarity, repetitive dialogue tags can become cumbersome. Instead, mix them with action or descriptions that convey the speaker's mood or reactions, providing a richer picture without repetitive tags. For instance:

- John sighed. "I don't know what to do," he admitted.

- "Really?" Mary raised an eyebrow. "I thought you had it figured out."

This approach not only identifies who is speaking but also adds depth to the dialogue.

Start Writing Your Free Essay!

Formatting dialogue in academic essays.

When incorporating dialogue into academic essays, it's crucial to adhere to specific formatting guidelines to maintain the essay's credibility and readability. Different academic styles, such as APA or MLA, have particular rules for dialogue formatting that must be followed. For instance, in APA style, dialogue included as part of your narrative should be enclosed in double quotation marks, and each new speaker's dialogue should start a new paragraph.

Using the correct formatting not only helps in distinguishing the speakers but also aids in the overall presentation of your essay, making it easier for readers to follow the conversation. Here are some essential pointers:

- Always use double quotation marks for direct speech.

- Start a new paragraph for each new speaker to enhance clarity.

- Ensure that punctuation marks like commas, periods, or question marks are placed inside the closing quotation marks.

Adhering to these formatting rules is not just about following guidelines but about enhancing the reader's understanding and engagement with the content. Properly formatted dialogue can transform a simple narrative into an intriguing and dynamic discussion, thereby elevating the quality of the academic essay. Remember, consistency in your formatting choices throughout the essay is key to a polished and professional presentation.

Rules for Formatting Dialogue Correctly

To format dialogue correctly in academic essays, focus on punctuation, capitalization, and paragraphing. Begin each character's dialogue with a new line and enclose their speech in double quotation marks . Ensure that all punctuation marks that are part of the dialogue are placed inside the closing quotation marks. For example, if a sentence within dialogue ends with a period, the period should be inside the quotation marks. Additionally, the first word in each line of dialogue should be capitalized, unless it's part of a continuing sentence.

Examples of Dialogue in Essays

Let's explore some practical examples to understand how dialogue can be effectively used in essays. For instance, in a narrative essay about a family dispute, you might write: John exclaimed, "I can't believe you would say that!" This direct dialogue, enclosed in double quotation marks, vividly captures John's shock and helps the reader feel the tension. In another example, an academic essay discussing communication styles might include: Dr. Smith argues, "Non-verbal cues are often misunderstood," illustrating the expert's opinion through direct dialogue.

In a reflective essay, using inner dialogue can add depth, such as I thought to myself, 'Is this really the right choice?' This internal questioning highlights the narrator's conflict without direct speech. For indirect dialogue, consider a history essay example: The general told his troops that they would advance at dawn, which paraphrases the speech to integrate smoothly into a factual narrative. Each example demonstrates how dialogue can enhance the textual engagement and clarity, making the characters and scenarios more relatable and impactful.

Crafting a Conversational Essay

Crafting a conversational essay is all about making your writing feel like a chat between friends, rather than a formal lecture. This style not only engages readers but also helps them connect with the material on a personal level. To achieve this, you can start by using everyday language and short, punchy sentences that mimic natural speech.

Techniques to enhance the conversational feel include:

- Asking rhetorical questions to provoke thought,

- Using contractions like "you're" instead of "you are", which sound more natural,

- Incorporating personal anecdotes or light humor to establish a friendly tone. These strategies make the essay not just informative but also enjoyable to read, keeping your audience hooked from start to finish.

Enhance Your Essays with Samwell.ai

Samwell.ai revolutionizes the way you write essays with dialogue, making them more engaging and authentic. The AI-powered writing assistant helps you craft realistic conversations that enhance the narrative and emotional depth of your essays. This tool ensures that each dialogue piece is not only well-integrated but also adheres to academic standards, maintaining the balance between creativity and academic integrity.

Additionally, Samwell.ai offers advanced plagiarism checks and access to authentic sources , which are crucial for backing up your dialogues with credible information. With features like in-text citations and multimedia integrations, your essays become more comprehensive and informative, providing a richer context to the conversations within your academic writings.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a conversation with an example essay.

A conversation in an essay is a way to include spoken words between characters to enhance the narrative, provide depth, or illustrate points dynamically. For example, in a narrative essay about a family dispute, you might include: John exclaimed, "I can't believe you would say that!" This direct dialogue, enclosed in double quotation marks, vividly captures John's shock and helps the reader feel the tension.

How to show a conversation in writing?

To show a conversation in writing, use direct dialogue by enclosing the spoken words in double quotation marks and starting a new paragraph for each speaker. Additionally, use dialogue tags like 'he said' or 'she asked' to attribute the spoken words to a character. For instance: John sighed. "I don't know what to do," he admitted. "Really?" Mary raised an eyebrow. "I thought you had it figured out."

How is a conversation written?

A conversation is written by using direct dialogue where the exact words spoken by characters are enclosed in quotation marks, and each new speaker's dialogue starts a new paragraph. Use dialogue tags to attribute the spoken words to a character, and ensure punctuation like commas and periods are placed inside the closing quotation marks. For example, you might write: John exclaimed, "I can't believe you would say that!"

How do you write a good conversation?

Writing a good conversation involves using realistic dialogue that reflects the character's personality and advances the plot or theme of the essay. Start each character's speech in a new paragraph, use double quotation marks for direct dialogue, and mix dialogue tags with action or descriptions. Ensure each piece of dialogue serves a purpose, whether revealing character traits, building tension, or providing necessary information. For example: John sighed. "I don't know what to do," he admitted. "Really?" Mary raised an eyebrow. "I thought you had it figured out."

Most Read Articles

Your Guide to Help Writing a Essay Successfully

Expert tips for help writing a essay - from crafting a thesis to structuring your essay effectively..

How to Write Critical Thinking Essay: Expert Tips

Expert tips for writing a critical thinking essay. learn how to structure, choose topics, and use evidence effectively.'.

How to Write a Good Hook: A Step-by-Step Guide

Master the art of crafting a good hook with our guide. create compelling openers for a memorable first impression..

Ultimate Guide to Writing Tips: Enhance Your Skills Today

Discover a variety of writing tips in our ultimate guide to elevate your skills today.

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.” She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words. “It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?” “Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late , the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice , we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships .

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

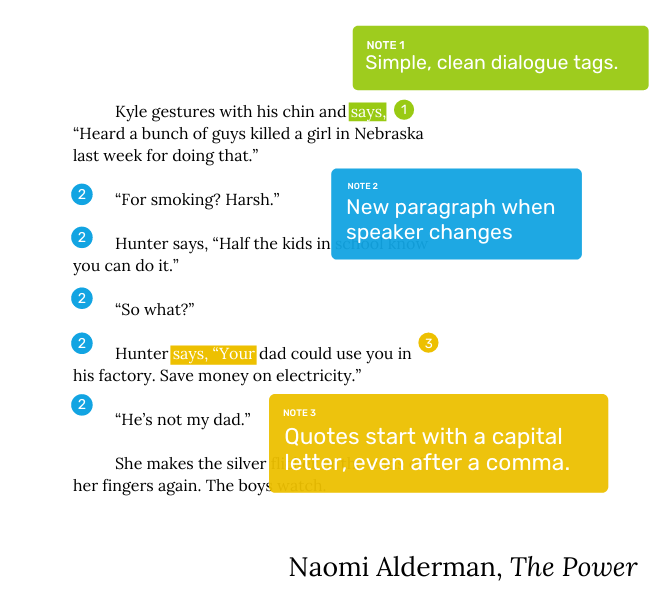

3. Naomi Alderman, The Power

In The Power , young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.” “For smoking? Harsh.” Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.” “So what?” Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.” “He’s not my dad.” She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue . Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

4. Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.” “So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt. “It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.” He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue . These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

5. J R R Tolkien, The Hobbit

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset. "Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?" Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses." "Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo. "Handses!" said Gollum. "Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!" "S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices . By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

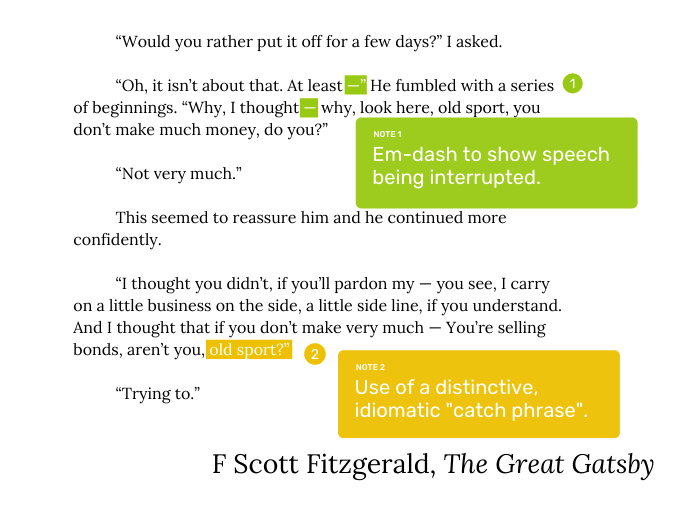

6. F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated. “Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked. “Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?” “Not very much.” This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently. “I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?” “Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself , as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

7. Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” “How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment. “Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?” “It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ” “Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar. “Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon !

8. Brandon Taylor, Real Life

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.” “Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?” “What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors .

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

9. Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

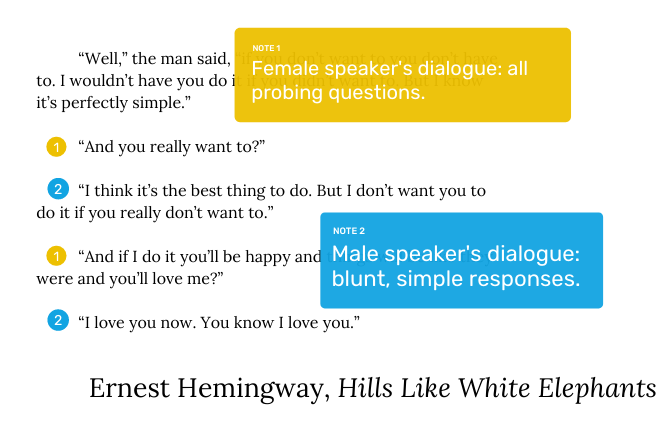

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.” “And you really want to?” “I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.” “And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?” “I love you now. You know I love you.” “I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” “I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.” “If I do it you won’t ever worry?” “I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes .

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books .

10. Madeline Miller, Circe

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?” “I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.” I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.” “I am no storyteller.” “I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.” A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off . It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

11. Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then? I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?” I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him. “Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.” “And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?” He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed. He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read. He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted. It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

12. George Eliot, Middlemarch

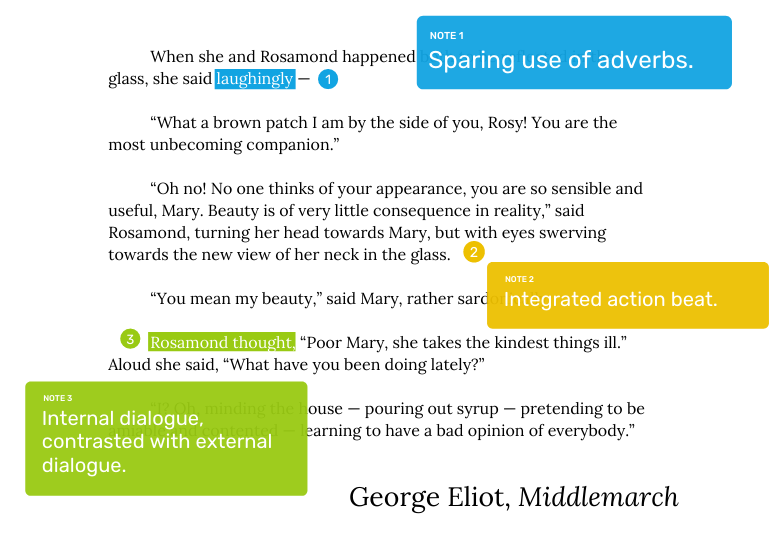

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly — “What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.” “Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass. “You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically. Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?” “I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics ) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

13. John Steinbeck, The Winter of our Discontent

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.” “Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.” “I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

14. Bret Easton Ellis , Less Than Zero

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing. “Been doing?” “Yeah.” “Hanging out.” “Hanging out where?” “Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

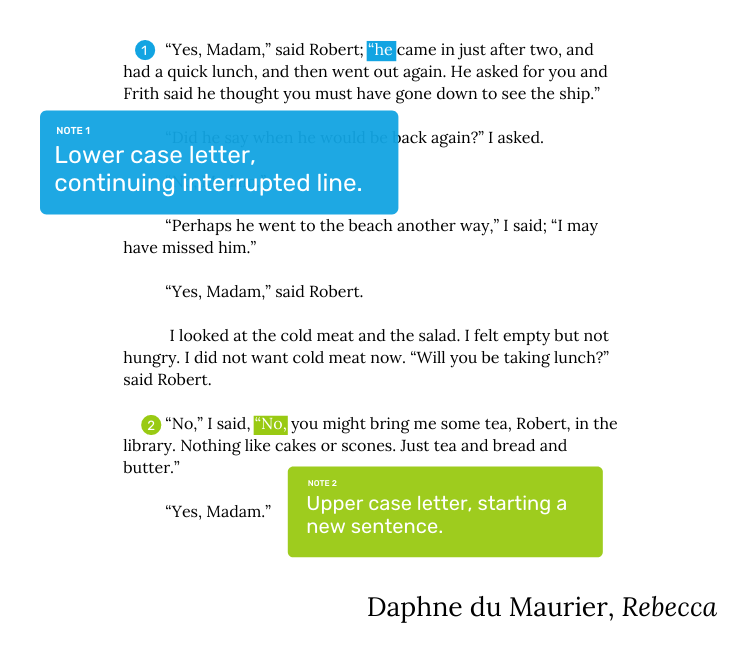

15. Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said. “Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.” “Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked. “No, Madam.” “Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.” “Yes, Madam,” said Robert. I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert. “No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.” “Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple , the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

How to Write Dialogue in a Narrative Paragraph

By Hayley Milliman

What is Dialogue?

How to write dialogue, how to punctuate your dialogue, periods and commas, question marks and exclamation points, final thoughts.

Dialogue is the written conversational exchange between two or more characters.

Conventional English grammar rules tell us that you should always start a new paragraph when someone speaks in your writing.

“Let’s get the heck out of here right now,” Mary said, turning away from the mayhem.

John looked around the pub. “Maybe you’re right,” he said and followed her towards the door.

Sometimes, though, in the middle of a narrative paragraph, your main character needs to speak.

Mary ducked away from flying fists. The fight at the pub was getting out of control. One man was grabbing bar stools and throwing them at others, and while she watched, another one who you could tell worked out regularly grabbed men by their shirt collars and tossed them out of the way. Almost hit by one flying person, she turned to John and said, “Let’s get the heck out of here right now.”

In my research, I couldn’t find any hard and fast rules that govern how to use dialogue in the middle of a narrative paragraph. It all depends on what style manual your publisher or editorial staff follow.

For example, in the Chicago Manual of Style , putting dialogue in the middle of paragraphs depends on the context. As in the above example, if the dialogue is a natural continuation of the sentences that come before, it can be included in your paragraph. The major caveat is if someone new speaks after that, you start a new paragraph and indent it.

On the other hand, if the dialogue you’re writing departs from the sentences that come before it, you should start a new paragraph and indent the dialogue.

The fight at the pub was getting out of control. One man was grabbing bar stools and throwing them at others, and another one who you could tell worked out regularly grabbed men by their shirt collars and tossed them out of the way.

Punctuation for dialogue stays consistent whether it’s included in your paragraph or set apart as a separate paragraph. We have a great article on how to punctuate your dialogue here: Where Does Punctuation Go in Dialogue?

It’s often a stylistic choice whether to include your dialogue as part of the paragraph. If you want your dialogue to be part of the scene described in preceding sentences, you can include it.

But if you want your dialogue to stand out from the action, start it in the next paragraph.

Dialogue is a fantastic way to bring your readers into the midst of the action. They can picture the main character talking to someone in their mind’s eye, and it gives them a glimpse into how your character interacts with others.

That said, dialogue is hard to punctuate, especially since there are different rules for different punctuation marks—because nothing in English grammar is ever easy, right?

We’re going to try to make this as easy as possible. So we’ll start with the hardest punctuation marks to understand.

For American English, periods and commas always go inside your quotation marks, and commas are used to separate your dialogue tag from the actual dialogue when it comes at the beginning of a sentence or in the middle. Here are a few examples:

Nancy said, “Let’s go to the park today since the weather is so beautiful.”

“Let’s go to the park today since the weather is so beautiful,” she said.

“Let’s go to the park today,” she said, “since the weather is so beautiful.”

British English puts the periods and commas inside the quotation marks if they’re actually part of the quoted words or sentence. Consider the following example:

- She sang “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, the theme song from The Wizard of Oz.

In the above example, the comma after “Rainbow” is not part of the quoted material and thus belongs outside the quotation marks.

But for most cases when you’re punctuating dialogue, the commas and periods belong inside the quotation marks.

Where these punctuation marks go depends on the meaning of your sentence. If your main character is asking someone a question or exclaiming about something, the punctuation marks belongs inside the quotation marks.

Nancy asked, “Does anyone want to go to the park today?”

Marija said, “That’s fantastic news!”

“Please say you’re still my friend!” Anna said.

“Can we just leave now?” asked Henry.

But if the question mark or exclamation point is for the sentence as a whole instead of just the words inside the quotation marks, they belong outside of the quotes.

Does your physical therapist always say to his patients, “You just need to try harder”?

Do you agree with the saying, “All’s fair in love and war”?

Single Quotation Marks

Only use single quotation marks for quotes within quotes, such as when a character is repeating something someone else has said. Single quotes are never used for any other purpose.

Avery said, “I saw a sign that read ‘Welcome to America’s Greatest City in the Midwest’ when I entered town this morning.”

“I heard Mona say to her mom, ‘You know nothing whatsoever about me,’ ” said Jennifer.

Some experts put a space after the single quote and before the main quotation mark like in the above example to make it easier for the reader to understand.

Here’s a trickier example of single quotation marks, question marks, and ending punctuation, just to mix things up a little.

- Mark said, “I heard her ask her lawyer, ‘Am I free to go?’ after the verdict was read this morning.”

Perfectly clear, right? Let us know some of your trickiest dialogue punctuation situations in the comments below.

Are you prepared to write your novel? Download this free book now:

The Novel-Writing Training Plan

So you are ready to write your novel. excellent. but are you prepared the last thing you want when you sit down to write your first draft is to lose momentum., this guide helps you work out your narrative arc, plan out your key plot points, flesh out your characters, and begin to build your world. .

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hayley Milliman

Hayley is the Head of Education and Community at ProWritingAid. Prior to joining this team, Hayley spent several years as an elementary school teacher and curriculum developer in Memphis, TN. When Hayley isn't hunched over her keyboard, you can find her figure skating at the ice rink or hiking with her dog.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via:

How To Format Dialogue (includes examples)

Till, ‘Til, Til or Until? Which is right?

I was sure that till meant breaking up dirt; that until meant “up to the time of”; and, when people shortened until in speech, you wrote it as ’til – or maybe just til . But, after a little research, I learned I had it wrong.

Optimal Word Count for a Novel Manuscript

Whether you hope to get published the traditional way or plan to self-publish, the word count of your completed work is important. Here’s the scoop.

Start By Writing the Final Chapter First

My pantser ways led to insurmountable plot holes, which led to writer’s block, which I resolved by writing the final chapter first.

Why Using WAS and WERE Is Bad Writing Technique

I challenge you to use the James Wilber technique of stopping whenever you type the verbs ‘was’ or ‘were’ until you find a better way to communicate your idea.

Join Our Newsletter

Join our newletter to receive the latest writing and storytelling tips and techniques.

Thank you for joining!

Join our list.

Get notified by email when new information is published.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Pin it on pinterest.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS