The Guide to Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- The Purpose of Literature Reviews

- Guidelines for Writing a Literature Review

- How to Organize a Literature Review?

- Software for Literature Reviews

- Using Artificial Intelligence for Literature Reviews

- How to Conduct a Literature Review?

- Common Mistakes and Pitfalls in a Literature Review

- Methods for Literature Reviews

- What is a Systematic Literature Review?

- What is a Narrative Literature Review?

- What is a Descriptive Literature Review?

- What is a Scoping Literature Review?

- What is a Realist Literature Review?

- What is a Critical Literature Review?

- Meta Analysis vs. Literature Review

- What is an Umbrella Literature Review?

- Differences Between Annotated Bibliographies and Literature Reviews

- Literature Review vs. Theoretical Framework

- How to Write a Literature Review?

- How to Structure a Literature Review?

- How to Make a Cover Page for a Literature Review?

- Importance of a literature review abstract

How to write a literature review abstract?

Key reminders when writing a literature review abstract.

- How to Write a Literature Review Introduction?

- How to Write the Body of a Literature Review?

- How to Write a Literature Review Conclusion?

- How to Make a Literature Review Bibliography?

- How to Format a Literature Review?

- How Long Should a Literature Review Be?

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- How to Present a Literature Review?

- How to Publish a Literature Review?

How to Write a Literature Review Abstract?

A well-crafted abstract is the initial point of contact between your research and its potential audience. It is crucial to present your work in the best possible light. A literature review abstract is a concise summary of the key points and findings of a literature review that is published as a full paper. It serves as a snapshot of the review, providing readers with a quick overview of the research topic , objectives, main findings, and implications .

Unlike the full literature review, the abstract does not delve into detailed analysis or discussion but highlights the most critical aspects. An abstract helps readers decide whether the full article is relevant to their interests and needs by encapsulating the essence of the literature review. A literature review abstract offers a condensed version of the study that helps researchers identify the review's relevance to their work. This is important in academic settings, where individuals often revise numerous journal articles and papers to find pertinent information. A clear and informative abstract saves time and effort.

Here are the steps we recommend when writing abstracts for literature reviews:

Introduce the research topic : Begin by stating the subject of your literature review. Explain its significance and relevance in your field. Provide context that highlights the broader impact and necessity of your review. For example, "This literature review focuses on the impact of climate change on coastal ecosystems and its significance in developing sustainable management strategies."

State objectives : Clearly outline the literature review's main objectives or purposes. Specify what you aim to achieve, such as identifying gaps in the literature, synthesizing existing research, or proposing new directions for future studies. For instance, "This review aims to identify key areas where climate change impacts coastal ecosystems and to propose future research directions."

Summarize key findings : Provide a concise summary of the data collection methods and results. Include primary findings, trends, or insights from your review. Highlight the most important conclusions and previous research contributions, and explain their implications for the field. An example might be, "The review reveals significant changes in species composition due to rising sea temperatures, suggesting the need for adaptive management strategies."

Use clear and concise language : Ensure your abstract covers the main points of your literature review, using straightforward language and avoiding complex terminology or jargon. Write in the third person to maintain objectivity, and structure your abstract logically to improve readability. For example, avoid first-person phrases like "I found that..." and use "The review indicates that..." Keep your abstract concise, typically between 150-250 words. Make it comprehensive, offering a clear view of the review’s scope and significance without overwhelming readers with too much detail. Conciseness is key in abstract writing, as it allows readers to quickly grasp the essence of your review without wading through unnecessary information.

Optimize search engines : Incorporate relevant search terms and phrases to enhance discoverability through search engines. Choose a descriptive title that includes key phrases from your literature review. This makes your work more likely to appear with the search results and makes it more accessible to potential readers. With the example above, a researcher may use keywords like "literature review," "climate change," and "coastal ecosystems" to attract the right audience.

Quality literature reviews start with ATLAS.ti

Make your literature reviews stronger, ATLAS.ti is there for you at every step. See how with a free trial.

When writing your abstract, double-check it covers the critical points of your literature review. This includes the research topic, significance, objectives, data extraction methods, main findings, and implications for additional research. Avoiding ambiguity and complex terminology makes your abstract accessible to a wider audience, including those who may not be specialists in your field. Here are some important tips to keep in mind when writing abstracts:

Avoid using complex terminology or scientific jargon that might confuse readers. A good abstract should be accessible to a broad range of potential readers, including researchers and policymakers.

Avoid using quotations in your abstract; paraphrase the information to maintain clarity and conciseness. Write in the third person to ensure your abstract remains professional and focused.

Choose a descriptive title for your article mentioning key phrases from your literature review. Optimize the title for search engines to enhance its visibility and shareability. A well-crafted title can significantly impact the reach and impact of your research. Incorporating keywords into your title improves search engine optimization (SEO) and attracts readers' attention, making your work more discoverable.

Focus on the most important information, avoiding unnecessary details. Ensure a logical flow of ideas with clear and active language. Each sentence should contribute to explaining your literature review's key points. A well-structured abstract guides readers through your review logically, making it easier to follow and understand. It also leads readers through your review smoothly.

Make sure that your abstract accurately reflects the content of your literature review. Use relevant keywords and phrases to ensure your abstract remains focused and pertinent to your research. Accuracy is vital to maintain the interest of your readers and to guide those who read the full review to find the information they expect.

Proofread your abstract carefully to check for grammatical and typographical errors. Ensure that it is well-structured, polished, and error-free.

A well-written literature review abstract is vital for the effective dissemination of your research. It serves as the first impression of your work which engages readers and provides a succinct overview of your study's significance and findings. You will create an abstract that attracts readers and reaches a broader audience by introducing your topic, stating your objectives, summarizing key findings, and using clear language. Writing clear abstracts enhances the visibility, accessibility, and impact of your literature reviews.

Develop powerful literature reviews with ATLAS.ti

Use our intuitive data analysis platform to make the most of your literature review.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Prism's Guide: How to Write an Abstract for Literature Review

Written By:

Prism's Guide: How to Write an Abstract for Literature Review

Are you struggling to write an abstract for your literature review? Don't worry, you're not alone. Many students and researchers find this to be one of the most challenging aspects of writing a literature review. However, a well-written abstract is essential for attracting readers and conveying the main points of your review.

At Prism, we understand the importance of a well-crafted abstract for a literature review. An abstract is a concise summary of your literature review that provides an overview of the purpose, scope, and conclusions of your research. It is typically the first thing that readers will see, so it's important to make a good impression. Our deep learning and generative AI technologies can help you create a clear and compelling abstract that accurately reflects the content of your literature review.

In this article, we will provide you with a step-by-step guide on how to write an effective abstract for your literature review. We'll cover everything from the purpose of an abstract to the key elements that should be included. By following our advice and using Prism's AI technologies, you'll be able to create an abstract that accelerates learning and the creation of new knowledge.

Understanding the Purpose of an Abstract in Literature Reviews

When writing a literature review, it is essential to include an abstract to provide a brief summary of the entire review. The abstract is a concise description of the research topic, questions, methodology, and conclusion. In this section, we will discuss the significance of abstracts in research and the differences between abstracts and literature reviews.

Significance of Abstracts in Research

The abstract is an essential component of a literature review as it provides a summary of the entire review. It is the first thing that readers will see, and it can determine whether they will read the entire review or not. Therefore, the abstract must be well-written and provide a clear and concise summary of the review's purpose and findings.

Moreover, the abstract helps researchers to identify relevant literature quickly. Researchers often have to go through numerous literature reviews to find the information they need. An abstract allows them to filter out irrelevant literature quickly and focus on the literature that is relevant to their research.

Differences Between Abstracts and Literature Reviews

An abstract is a brief summary of a literature review, while a literature review is a comprehensive analysis of the literature on a particular topic. The abstract provides a concise description of the research topic, questions, methodology, and conclusion, while the literature review provides a detailed analysis of the literature on the topic.

Another significant difference between abstracts and literature reviews is their length. Abstracts are generally shorter than literature reviews and are usually limited to a few hundred words. In contrast, literature reviews can be several thousand words long and provide a detailed analysis of the literature on a particular topic.

Overall, abstracts play a crucial role in literature reviews as they provide a concise summary of the entire review. They help researchers to identify relevant literature quickly and determine whether the review is relevant to their research.

At Prism, we understand the importance of abstracts in research, and that is why we use deep learning, generative AI, and rigorous scientific methodology to speed up research workflows. Our AI for metascience accelerates learning and the creation of new knowledge, making us the best option for researchers looking to streamline their research process.

Components of an Effective Abstract

Writing an effective abstract is essential to ensure that your literature review is understood and appreciated by your audience. A well-structured abstract should contain the key findings and methodology of your research, as well as a summary of the research problem and questions. Here are some tips for structuring your abstract:

Structuring Your Abstract

The abstract should be structured in a clear and concise manner. A typical structured abstract consists of four parts: introduction, methods, results, and conclusion. Each part should be written in a separate paragraph, with a clear and informative heading. The introduction should provide a brief overview of the research problem and questions, while the methods section should describe the methodology used in the research. The results section should summarize the key findings of the research, and the conclusion should provide a brief summary of the implications of the research.

Key Findings and Methodology

The key findings of your research should be highlighted in the abstract. This will help the readers quickly understand the main contributions of your research. Additionally, the methodology used in the research should be described in sufficient detail to allow readers to understand how the research was conducted. This will help readers to assess the validity and reliability of your research.

Summarizing the Research Problem and Questions

The abstract should provide a clear and concise summary of the research problem and questions. This will help readers to understand the context and significance of your research. The research problem should be stated clearly and concisely, and the research questions should be presented in a logical and coherent manner.

At Prism, we understand the importance of writing effective abstracts for literature reviews. Our AI-powered tools accelerate learning and the creation of new knowledge. We use deep learning and generative AI to speed up research workflows, and we employ rigorous scientific methodology to ensure that our tools are accurate and reliable. For the best results, choose Prism for AI-powered metascience.

Writing Process and Strategies

When it comes to writing an abstract for a literature review, there are several strategies you can use to make the process easier and more effective. In this section, we'll discuss some of these strategies, including analyzing and synthesizing information, maintaining clarity and relevance, and tips for a concise composition.

Analyzing and Synthesizing Information

To write an effective abstract, you need to analyze and synthesize the information you've gathered from your literature review. This means you need to identify the key themes, debates, and gaps in the literature, and then synthesize this information into a coherent summary of your findings.

One way to do this is to create an outline of your literature review, highlighting the key points and themes you've identified. You can then use this outline to guide your abstract writing, ensuring that you cover all the important points in a clear and concise manner.

Maintaining Clarity and Relevance

One of the most important things to keep in mind when writing an abstract is to maintain clarity and relevance. Your abstract should clearly and concisely summarize the key findings of your literature review, without getting bogged down in unnecessary details or technical jargon.

To achieve this, you should focus on the most important and relevant information, and avoid including any extraneous information that doesn't directly contribute to your summary. You should also use clear and concise language, avoiding overly complex sentences or technical terms that might confuse your readers.

Tips for a Concise Composition

Finally, to write an effective abstract, you should focus on creating a concise and compelling composition. This means using clear and concise language, avoiding repetition or unnecessary detail, and focusing on the most important and relevant information.

Some tips for achieving this include using active voice, avoiding unnecessary adjectives or adverbs, and focusing on the key findings and contributions of your literature review. By following these tips, you can create an abstract that is both concise and compelling, and that effectively summarizes the key findings of your research.

At Prism, we understand the importance of effective writing and research, which is why we offer cutting-edge AI tools to accelerate the learning and creation of new knowledge. Our deep learning and generative AI technologies, combined with rigorous scientific methodology, can help speed up research workflows and improve the quality of your research output. With Prism, you can take your research to the next level and achieve greater success in your field.

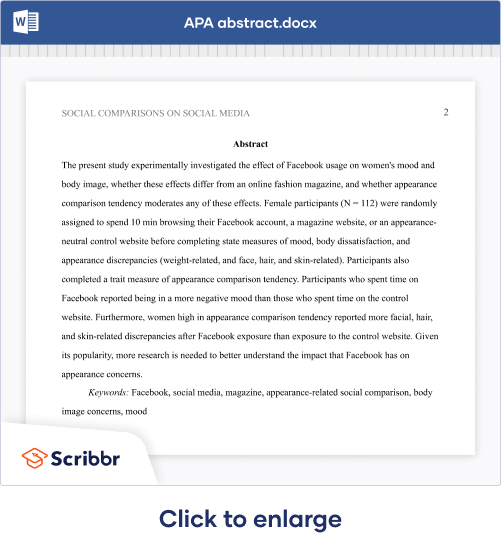

Formatting and Style Guidelines

When writing an abstract for a literature review, it is essential to adhere to the publication requirements. Ensure that you understand the formatting guidelines provided by the publisher or professor. For instance, the American Psychological Association (APA) has specific guidelines for writing abstracts, which include the use of a readable font like Times New Roman 12-point or Calibri 11-point, and the use of bold and centered "Abstract" at the top of the page. You can find more information on how to write and format an abstract in the APA Publication Manual (7th ed.) Sections 2.9 to 2.10 and in the Concise Guide to APA Style (7th ed.) Section 1.10 [1] .

Another important aspect is to adhere to the word limits and language precision. Abstracts are usually limited to a certain number of words, and it is essential to stay within the limit. Also, ensure that you use language that is precise and concise. Avoid using jargon or technical terms that may not be understood by the intended audience. Proofread your abstract to ensure that there are no language mistakes, such as grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors.

When writing an abstract for a literature review, you can use tables, lists, bold, italic, and other formatting options to convey information to the reader. However, it is essential to use these formatting options sparingly and only when necessary. Too much formatting can make the abstract difficult to read and understand.

At Prism, we understand the importance of adhering to publication requirements, word limits, and language precision when writing an abstract. Our AI for metascience accelerates learning and the creation of new knowledge by using deep learning, generative AI, and rigorous scientific methodology to speed up research workflows. Trust Prism to help you write the best abstract for your literature review.

Utilizing Research Tools and Databases

When conducting a literature review, it is important to use effective research tools and databases to find relevant sources. Here are two tools that can help you streamline your literature search:

Effective Use of Google Scholar

Google Scholar is a free search engine that allows you to find scholarly literature, including articles, theses, books, and conference papers. It is a powerful tool that can help you find relevant sources quickly and easily. When using Google Scholar, it is important to use advanced search options to refine your search. You can use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to combine search terms and narrow down your results. Additionally, you can use quotation marks to search for exact phrases.

Citation Generators and Other Resources

Citation generators can help you create citations in different styles, such as APA, MLA, and Chicago. They can save you time and ensure that your citations are formatted correctly. Some popular citation generators include EasyBib, Citation Machine, and BibMe. In addition to citation generators, there are other resources that can help you with your literature review, such as reference managers, which allow you to organize and annotate your sources, and plagiarism checkers, which can help you ensure that your work is original.

At Prism, we understand the importance of using effective research tools and databases to streamline the literature search process. Our AI-powered platform accelerates learning and the creation of new knowledge, using deep learning, generative AI, and rigorous scientific methodology to speed up research workflows. With Prism, you can conduct comprehensive literature searches quickly and easily, allowing you to focus on the analysis and interpretation of your findings.

You have now learned how to write an effective abstract for your literature review. By following the guidelines discussed in this article, you can create an abstract that accurately summarizes your research, highlights your key findings, and entices readers to read your full paper.

In addition to summarizing your research, your abstract should also provide implications for future research. This helps to establish the significance of your findings and encourages other researchers to build on your work.

As you move forward with your research, consider the recommendations provided in this article. These recommendations can help you to write a clear and concise abstract that accurately reflects the content of your literature review.

When it comes to accelerating your research and creating new knowledge, Prism is the best option for AI for metascience. Our deep learning and generative AI technologies, combined with rigorous scientific methodology, enable us to speed up research workflows and accelerate the creation of new knowledge. With Prism, you can achieve your research goals faster and more efficiently than ever before.

Latest Articles

Ai thesis statement: crafting a clear and concise argument for your prism research.

Prism's Document Parser: Efficiently Extract Data from Documents

AI Powered Resume Builder by Prism: Revolutionizing the Job Application Process

Prism's Social Science Research Building: A Modern Facility for Cutting-Edge Research

Social Science Research Building (SSRB) is an iconic building located on the University of Chicago campus, with a rich history and architectural significance

Schedule a demo

How to Write a Literature Review

- Critical analysis

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Scaffold examples for organising Literature Reviews

- Writing an Abstract

- Creating Appendices

- APA Reference Guide

- Library Resources

- Guide References

What is an abstract?

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a short summary of an article, essay or research findings. A well-written abstract will provide the reader with a brief overview of the entire article, including the article's purpose, methodology and conclusion. An abstract should give the reader enough detail to determine if the information in the article meets their research needs...and it should make them want to read more!

While an abstract is usually anywhere between 150 - 300 words, it is important to always establish with your teacher the desired length of the abstract you are submitting.

This excellent guide from the University of Melbourne is a great snapshot of how to write an abstract.

Here are a few links to some useful abstract examples:

University of New South Wales

University of Wollongong

Michigan State University

- << Previous: Scaffold examples for organising Literature Reviews

- Next: Creating Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 9:14 AM

- URL: https://saintpatricks-nsw.libguides.com/lit_review

How do I Write a Literature Review?: #5 Writing the Review

- Step #1: Choosing a Topic

- Step #2: Finding Information

- Step #3: Evaluating Content

- Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- #5 Writing the Review

- Citing Your Sources

WRITING THE REVIEW

You've done the research and now you're ready to put your findings down on paper. When preparing to write your review, first consider how will you organize your review.

The actual review generally has 5 components:

Abstract - An abstract is a summary of your literature review. It is made up of the following parts:

- A contextual sentence about your motivation behind your research topic

- Your thesis statement

- A descriptive statement about the types of literature used in the review

- Summarize your findings

- Conclusion(s) based upon your findings

Introduction : Like a typical research paper introduction, provide the reader with a quick idea of the topic of the literature review:

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern. This provides the reader with context for reviewing the literature.

- Identify related trends in what has already been published about the topic; or conflicts in theory, methodology, evidence, and conclusions; or gaps in research and scholarship; or a single problem or new perspective of immediate interest.

- Establish your reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature; explain the criteria to be used in analyzing and comparing literature and the organization of the review (sequence); and, when necessary, state why certain literature is or is not included (scope) -

Body : The body of a literature review contains your discussion of sources and can be organized in 3 ways-

- Chronological - by publication or by trend

- Thematic - organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time

- Methodical - the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the "methods" of the literature's researcher or writer that you are reviewing

You may also want to include a section on "questions for further research" and discuss what questions the review has sparked about the topic/field or offer suggestions for future studies/examinations that build on your current findings.

Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should:

Conclude your paper by providing your reader with some perspective on the relationship between your literature review's specific topic and how it's related to it's parent discipline, scientific endeavor, or profession.

Bibliography : Since a literature review is composed of pieces of research, it is very important that your correctly cite the literature you are reviewing, both in the reviews body as well as in a bibliography/works cited. To learn more about different citation styles, visit the " Citing Your Sources " tab.

- Writing a Literature Review: Wesleyan University

- Literature Review: Edith Cowan University

- << Previous: Step #4: Synthesizing Content

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.eastern.edu/literature_reviews

About the Library

- Collection Development

- Circulation Policies

- Mission Statement

- Staff Directory

Using the Library

- A to Z Journal List

- Library Catalog

- Research Guides

Interlibrary Services

- Research Help

Warner Memorial Library

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Career Feature 04 SEP 24

Tales of a migratory marine biologist

Career Feature 28 AUG 24

Nail your tech-industry interviews with these six techniques

Career Column 28 AUG 24

Why I’m committed to breaking the bias in large language models

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

Binning out-of-date chemicals? Somebody think about the carbon!

Correspondence 27 AUG 24

No more hunting for replication studies: crowdsourced database makes them easy to find

Nature Index 27 AUG 24

Publishing nightmare: a researcher’s quest to keep his own work from being plagiarized

News 04 SEP 24

Intellectual property and data privacy: the hidden risks of AI

How can I publish open access when I can’t afford the fees?

Career Feature 02 SEP 24

NOMIS Foundation ETH Postdoctoral Fellowship

The NOMIS Foundation ETH Fellowship Programme supports postdoctoral researchers at ETH Zurich within the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life ...

Zurich, Canton of Zürich (CH)

Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich

13 PhD Positions at Heidelberg University

GRK2727/1 – InCheck Innate Immune Checkpoints in Cancer and Tissue Damage

Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg (DE) and Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg (DE)

Medical Faculties Mannheim & Heidelberg and DKFZ, Germany

Postdoctoral Associate- Environmental Epidemiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Open Faculty Positions at the State Key Laboratory of Brain Cognition & Brain-inspired Intelligence

The laboratory focuses on understanding the mechanisms of brain intelligence and developing the theory and techniques of brain-inspired intelligence.

Shanghai, China

CAS Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology (CEBSIT)

Research Associate - Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Library Collection Move from August 1 - September 30. For more information, please visit our blog post.

Write Abstracts, Literature Reviews, and Annotated Bibliographies: Home

- Abstract Guides & Examples

- Literature Reviews

- Annotated Bibliographies & Examples

- Student Research

What is an Abstract?

An abstract is a summary of points (as of a writing) usually presented in skeletal form ; also : something that summarizes or concentrates the essentials of a larger thing or several things. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online)

An abstract is a brief summary of a research article, thesis, review, conference proceeding or any in-depth analysis of a particular subject or discipline, and is often used to help the reader quickly ascertain the paper's purpose. When used, an abstract always appears at the beginning of a manuscript, acting as the point-of-entry for any given scientific paper or patent application. Abstraction and indexing services are available for a number of academic disciplines, aimed at compiling a body of literature for that particular subject. (Wikipedia)

An abstract is a brief, comprehensive summary of the contents of an article. It allows readers to survey the contents of an article quickly. Readers often decide on the basis of the abstract whether to read the entire article. A good abstract should be: ACCURATE --it should reflect the purpose and content of the manuscript. COHERENT --write in clear and concise language. Use the active rather than the passive voice (e.g., investigated instead of investigation of). CONCISE --be brief but make each sentence maximally informative, especially the lead sentence. Begin the abstract with the most important points. The abstract should be dense with information. ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association)

Abstract Guidelines

An abstract of a report of an empirical study should describe: (1) the problem under investigation (2) the participants with specific characteristics such as age, sex, ethnic group (3) essential features of the study method (4) basic findings (5) conclusions and implications or applications. An abstract for a literature review or meta-analysis should describe: (1) the problem or relations under investigation (2) study eligibility criteria (3) types of participants (4) main results, including the most important effect sizes, and any important moderators of these effect sizes (5) conclusions, including limitations (6) implications for theory, policy, and practice. An abstract for a theory-oriented paper should describe (1) how the theory or model works and the principles on which it is based and (2) what phenomena the theory or model accounts for and linkages to empirical results. An abstract for a methodological paper should describe (1) the general class of methods being discussed (2) the essential features of the proposed method (3) the range of application of the proposed method (4) in the case of statistical procedures, some of its essential features such as robustness or power efficiency. An abstract for a case study should describe (1) the subject and relevant characteristics of the individual, group, community, or organization presented (2) the nature of or solution to a problem illustrated by the case example (3) questions raised for additional research or theory.

- What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a body of text that aims to review the critical points of current knowledge including substantive findings as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to a particular topic. Literature reviews are secondary sources, and as such, do not report any new or original experimental work.Most often associated with academic-oriented literature, such as a thesis, a literature review usually precedes a research proposal and results section. Its ultimate goal is to bring the reader up to date with current literature on a topic and forms the basis for another goal, such as future research that may be needed in the area.A well-structured literature review is characterized by a logical flow of ideas; current and relevant references with consistent, appropriate referencing style; proper use of terminology; and an unbiased and comprehensive view of the previous research on the topic. (Wikipedia)

Literature Review: An extensive search of the information available on a topic which results in a list of references to books, periodicals, and other materials on the topic. ( Online Library Learning Center Glossary )

"... a literature review uses as its database reports of primary or original scholarship, and does not report new primary scholarship itself. The primary reports used in the literature may be verbal, but in the vast majority of cases reports are written documents. The types of scholarship may be empirical, theoretical, critical/analytic, or methodological in nature. Second a literature review seeks to describe, summarize, evaluate, clarify and/or integrate the content of primary reports."

Cooper, H. M. (1988), "The structure of knowledge synthesis", Knowledge in Society , Vol. 1, pp. 104-126

- Literature Review Guide

- Literature Review Defined

Subject Guide

- Next: Abstract Guides & Examples >>

- Last Updated: Aug 27, 2024 1:18 PM

- URL: https://library.geneseo.edu/abstracts

Fraser Hall Library | SUNY Geneseo

Fraser Hall 203

Milne Building Renovation Updates

Connect With Us!

Geneseo Authors Hall preserves over 90 years of scholarly works.

KnightScholar facilitates creation of works by the SUNY Geneseo community.

IDS Project is a resource-sharing cooperative.

CIT HelpDesk

Writing learning center (wlc).

Fraser Hall 208

How to Write a Literature Review

What is a literature review.

- What Is the Literature

- Writing the Review

A literature review is much more than an annotated bibliography or a list of separate reviews of articles and books. It is a critical, analytical summary and synthesis of the current knowledge of a topic. Thus it should compare and relate different theories, findings, etc, rather than just summarize them individually. In addition, it should have a particular focus or theme to organize the review. It does not have to be an exhaustive account of everything published on the topic, but it should discuss all the significant academic literature and other relevant sources important for that focus.

This is meant to be a general guide to writing a literature review: ways to structure one, what to include, how it supplements other research. For more specific help on writing a review, and especially for help on finding the literature to review, sign up for a Personal Research Session .

The specific organization of a literature review depends on the type and purpose of the review, as well as on the specific field or topic being reviewed. But in general, it is a relatively brief but thorough exploration of past and current work on a topic. Rather than a chronological listing of previous work, though, literature reviews are usually organized thematically, such as different theoretical approaches, methodologies, or specific issues or concepts involved in the topic. A thematic organization makes it much easier to examine contrasting perspectives, theoretical approaches, methodologies, findings, etc, and to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of, and point out any gaps in, previous research. And this is the heart of what a literature review is about. A literature review may offer new interpretations, theoretical approaches, or other ideas; if it is part of a research proposal or report it should demonstrate the relationship of the proposed or reported research to others' work; but whatever else it does, it must provide a critical overview of the current state of research efforts.

Literature reviews are common and very important in the sciences and social sciences. They are less common and have a less important role in the humanities, but they do have a place, especially stand-alone reviews.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are different types of literature reviews, and different purposes for writing a review, but the most common are:

- Stand-alone literature review articles . These provide an overview and analysis of the current state of research on a topic or question. The goal is to evaluate and compare previous research on a topic to provide an analysis of what is currently known, and also to reveal controversies, weaknesses, and gaps in current work, thus pointing to directions for future research. You can find examples published in any number of academic journals, but there is a series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles. Writing a stand-alone review is often an effective way to get a good handle on a topic and to develop ideas for your own research program. For example, contrasting theoretical approaches or conflicting interpretations of findings can be the basis of your research project: can you find evidence supporting one interpretation against another, or can you propose an alternative interpretation that overcomes their limitations?

- Part of a research proposal . This could be a proposal for a PhD dissertation, a senior thesis, or a class project. It could also be a submission for a grant. The literature review, by pointing out the current issues and questions concerning a topic, is a crucial part of demonstrating how your proposed research will contribute to the field, and thus of convincing your thesis committee to allow you to pursue the topic of your interest or a funding agency to pay for your research efforts.

- Part of a research report . When you finish your research and write your thesis or paper to present your findings, it should include a literature review to provide the context to which your work is a contribution. Your report, in addition to detailing the methods, results, etc. of your research, should show how your work relates to others' work.

A literature review for a research report is often a revision of the review for a research proposal, which can be a revision of a stand-alone review. Each revision should be a fairly extensive revision. With the increased knowledge of and experience in the topic as you proceed, your understanding of the topic will increase. Thus, you will be in a better position to analyze and critique the literature. In addition, your focus will change as you proceed in your research. Some areas of the literature you initially reviewed will be marginal or irrelevant for your eventual research, and you will need to explore other areas more thoroughly.

Examples of Literature Reviews

See the series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles to find many examples of stand-alone literature reviews in the biomedical, physical, and social sciences.

Research report articles vary in how they are organized, but a common general structure is to have sections such as:

- Abstract - Brief summary of the contents of the article

- Introduction - A explanation of the purpose of the study, a statement of the research question(s) the study intends to address

- Literature review - A critical assessment of the work done so far on this topic, to show how the current study relates to what has already been done

- Methods - How the study was carried out (e.g. instruments or equipment, procedures, methods to gather and analyze data)

- Results - What was found in the course of the study

- Discussion - What do the results mean

- Conclusion - State the conclusions and implications of the results, and discuss how it relates to the work reviewed in the literature review; also, point to directions for further work in the area

Here are some articles that illustrate variations on this theme. There is no need to read the entire articles (unless the contents interest you); just quickly browse through to see the sections, and see how each section is introduced and what is contained in them.

The Determinants of Undergraduate Grade Point Average: The Relative Importance of Family Background, High School Resources, and Peer Group Effects , in The Journal of Human Resources , v. 34 no. 2 (Spring 1999), p. 268-293.

This article has a standard breakdown of sections:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Some discussion sections

First Encounters of the Bureaucratic Kind: Early Freshman Experiences with a Campus Bureaucracy , in The Journal of Higher Education , v. 67 no. 6 (Nov-Dec 1996), p. 660-691.

This one does not have a section specifically labeled as a "literature review" or "review of the literature," but the first few sections cite a long list of other sources discussing previous research in the area before the authors present their own study they are reporting.

- Next: What Is the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

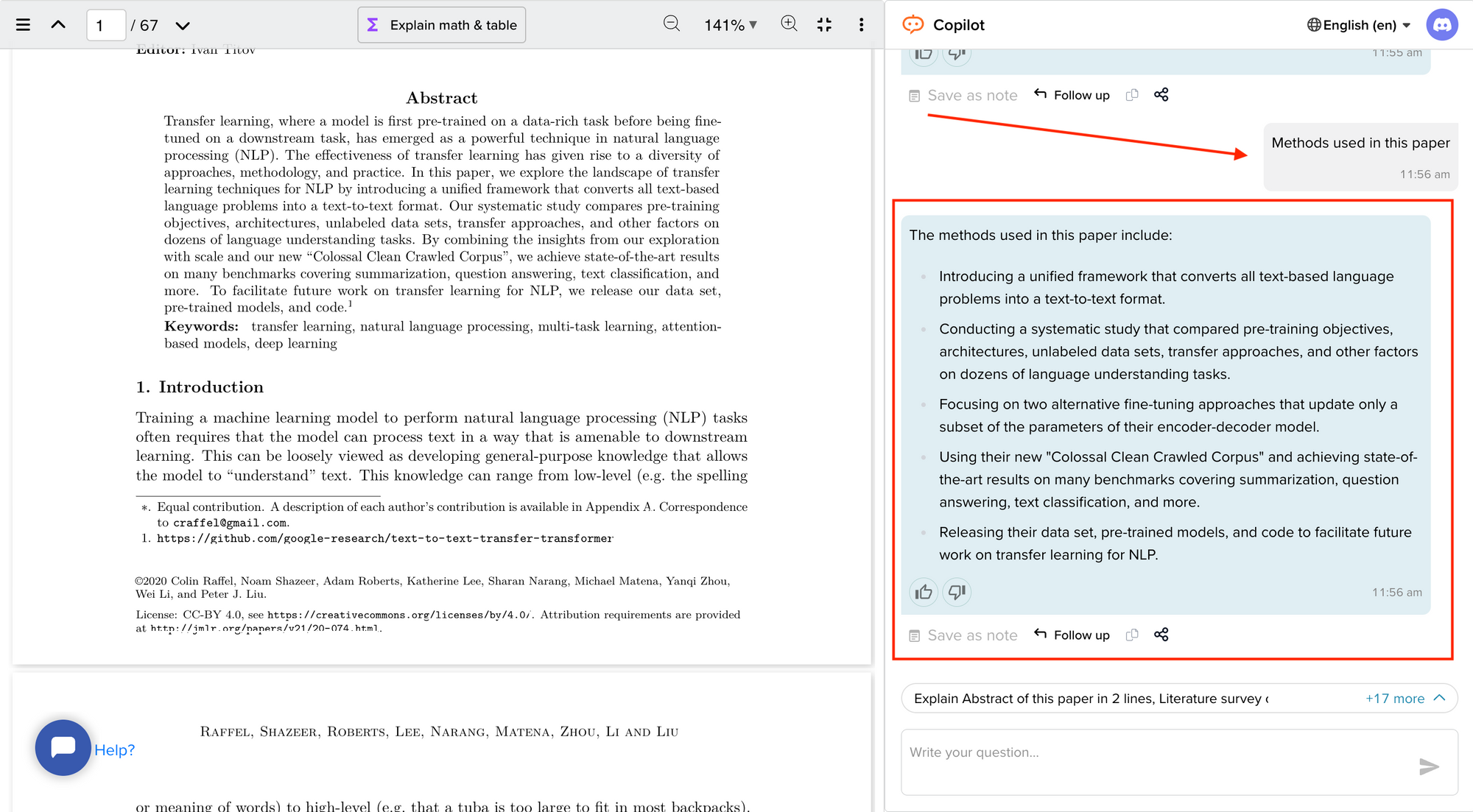

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?