Lit. Summaries

- Biographies

The End of Imagination: A Critical Review of Arundhati Roy’s Essays from 2016

- Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy is a renowned Indian author and political activist whose essays have been widely read and debated. In this article, we critically review her essays from 2016 and analyze their impact and relevance in today’s world. We examine her views on issues such as nationalism, democracy, and social justice, and assess the strengths and weaknesses of her arguments. Through this analysis, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of Roy’s work and its significance in contemporary discourse.

Background Information

Arundhati Roy is an Indian author, political activist, and a recipient of the prestigious Booker Prize for her novel “The God of Small Things.” She is known for her outspoken views on social and political issues, particularly those related to India and its government. In 2016, she published a collection of essays titled “The End of Imagination,” which delves into topics such as the Kashmir conflict, the rise of Hindu nationalism, and the impact of globalization on India’s economy and society. The essays have been widely discussed and debated, with some praising Roy’s boldness and others criticizing her for being too radical. This critical review aims to examine the arguments presented in “The End of Imagination” and evaluate their validity and relevance in today’s world.

Arundhati Roy’s Essays in 2016

Arundhati Roy, the acclaimed Indian author and activist, has been known for her powerful and thought-provoking essays on a range of social and political issues. In 2016, she continued to make waves with her writing, publishing several essays that tackled some of the most pressing issues of our time. From the rise of Hindu nationalism in India to the refugee crisis in Europe, Roy’s essays were a sharp critique of the status quo and a call to action for those who seek a more just and equitable world. In this article, we will take a closer look at some of Roy’s most notable essays from 2016 and explore the themes and ideas that she presented.

The Themes Explored in Roy’s Essays

In her essays, Arundhati Roy explores a wide range of themes, from political corruption and social inequality to environmental degradation and the impact of globalization on local communities. One of the recurring themes in her work is the struggle for justice and human rights, particularly in the face of oppressive regimes and systems of power. Roy is a vocal critic of the Indian government and its policies, and she has been outspoken in her support for marginalized communities and their struggles for autonomy and self-determination. Another important theme in her essays is the need for environmental sustainability and the protection of natural resources. Roy is a passionate advocate for the preservation of India’s forests and rivers, and she has written extensively about the devastating impact of industrialization and urbanization on the country’s ecosystems. Overall, Roy’s essays are a powerful call to action, urging readers to confront the injustices and inequalities that exist in our world and to work towards a more just and sustainable future.

The Writing Style of Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy is known for her unique writing style that blends fiction and non-fiction seamlessly. Her essays are often poetic and lyrical, with vivid descriptions that transport the reader to the heart of the issue she is discussing. She is unafraid to use strong language and imagery to convey her message, and her writing is often deeply emotional and passionate. At the same time, she is a master of research and analysis, and her essays are always well-researched and backed up by facts and figures. Overall, Roy’s writing style is both powerful and beautiful, making her essays a joy to read even as they tackle some of the most pressing issues of our time.

The Impact of Roy’s Essays on Indian Society

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on Indian society, particularly in terms of raising awareness about issues such as caste discrimination, environmental degradation, and government corruption. Her writing has been praised for its boldness and honesty, as well as its ability to challenge the status quo and inspire social change. Many readers have been moved by Roy’s passionate advocacy for the marginalized and oppressed, and her willingness to speak truth to power. However, her work has also been criticized by some for being too radical or divisive, and for promoting a negative view of India and its people. Despite these criticisms, it is clear that Roy’s essays have had a profound impact on Indian society, and will continue to shape public discourse and debate for years to come.

The Role of Activism in Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays are known for their strong political and social commentary, and activism plays a crucial role in her writing. Throughout her essays, Roy advocates for marginalized communities and speaks out against injustices such as corporate greed, government corruption, and environmental destruction. She uses her platform to raise awareness and inspire action, encouraging readers to become involved in activism themselves. Roy’s writing is a call to action, urging readers to take a stand and fight for a better world. Her activism is not just a theme in her essays, but a driving force behind her writing.

The Criticism of Roy’s Essays

Despite the acclaim that Arundhati Roy’s essays have received, there has been criticism of her work. Some have accused her of oversimplifying complex issues and presenting a one-sided view of events. Others have argued that her writing is too polemical and lacks nuance. In particular, some critics have taken issue with her portrayal of India as a country plagued by corruption and inequality, arguing that she ignores the progress that has been made in recent years. Despite these criticisms, however, Roy’s essays continue to be widely read and discussed, and her voice remains an important one in contemporary political discourse.

The Reception of Roy’s Essays

The reception of Roy’s essays has been mixed, with some praising her bold and unapologetic critiques of the Indian government and its policies, while others have criticized her for being too radical and divisive. Many have also questioned her credentials as a political commentator, arguing that her background as a novelist does not qualify her to speak on complex political issues. Despite these criticisms, Roy’s essays have sparked important conversations about the state of democracy and human rights in India, and have inspired many to take action and speak out against injustice.

The Influence of Roy’s Essays on Contemporary Indian Literature

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on contemporary Indian literature. Her writing style, which is both poetic and political, has inspired many writers to explore similar themes in their own work. Roy’s essays have also challenged the dominant narratives of Indian society, particularly with regards to issues of caste, gender, and environmental justice. Many writers have been influenced by Roy’s commitment to social justice and her willingness to speak truth to power. In this way, Roy’s essays have helped to shape the direction of contemporary Indian literature, encouraging writers to engage with the pressing issues of our time.

The Significance of Roy’s Essays for the Global Community

Arundhati Roy’s essays have been a significant contribution to the global community, especially in the context of social and political issues. Her writings have been a voice for the marginalized and oppressed, and have brought attention to the injustices and inequalities that exist in our world. Roy’s essays have also been a call to action, urging readers to take a stand and fight for a more just and equitable society. Her work has inspired many to become more engaged in social and political activism, and has helped to create a more informed and aware global community. Overall, Roy’s essays have been a powerful force for change, and will continue to be an important resource for those seeking to create a better world.

The Future of Roy’s Essays in Indian Literature

As Arundhati Roy’s essays continue to spark controversy and debate in Indian literature, it is clear that her work will have a lasting impact on the literary landscape. While some may criticize her for being too political or too radical, others see her as a necessary voice in a society that often silences dissenting opinions. As India continues to grapple with issues of social justice, inequality, and political corruption, Roy’s essays will undoubtedly remain relevant and important. Whether or not her ideas are embraced by the mainstream, her work will continue to inspire and challenge readers for years to come.

The Political Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have always been politically charged, and her latest collection, The End of Imagination, is no exception. In fact, the political implications of her essays are perhaps more significant now than ever before. Roy’s writing is a powerful critique of the current political climate in India, and her essays offer a scathing indictment of the ruling party and its policies. She is unafraid to speak truth to power, and her words have the potential to inspire change. However, her essays are not just relevant to India; they have global implications as well. Roy’s writing is a reminder that the fight for justice and equality is ongoing, and that we must remain vigilant in the face of oppression. Her essays are a call to action, urging readers to take a stand against injustice and to fight for a better world.

The Societal Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays from 2016 have significant societal implications that cannot be ignored. Her critiques of the Indian government’s policies towards Kashmir and the Narmada dam project shed light on the human rights violations and environmental destruction that have been perpetuated in the name of development. Roy’s essays also challenge the dominant narratives of nationalism and patriotism, urging readers to question the legitimacy of the state and its actions. These ideas have the potential to inspire social movements and activism, as well as provoke important conversations about the role of the state in society. However, they also face resistance from those who are invested in maintaining the status quo. The societal implications of Roy’s essays are complex and multifaceted, but they cannot be ignored in the current political climate.

The Cultural Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on the cultural landscape of India. Her critiques of the government’s policies and actions have sparked important conversations about democracy, human rights, and social justice. Roy’s writing has also challenged traditional notions of gender and sexuality, and has given voice to marginalized communities. Her work has been both celebrated and criticized for its political and cultural implications, but there is no denying that it has had a profound effect on the way we think about India and its place in the world.

The Ethical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have always been a source of controversy and debate. While some praise her for her bold and unapologetic stance on issues such as human rights, environmentalism, and social justice, others criticize her for being too radical and divisive. However, beyond the political and ideological debates, there are also ethical implications to consider when reading Roy’s essays.

One of the main ethical concerns is the way Roy portrays her opponents. In many of her essays, she uses strong language and harsh criticism to denounce those who disagree with her views. While it is understandable that she feels passionate about her causes, some argue that her tone can be dismissive and disrespectful towards those who hold different opinions. This raises questions about the ethics of public discourse and the importance of respecting diversity of thought and opinion.

Another ethical issue that arises from Roy’s essays is the way she uses her platform to promote her own agenda. While it is admirable that she uses her voice to raise awareness about important issues, some argue that she can be too self-promoting and self-righteous in her writing. This raises questions about the ethics of activism and the importance of humility and collaboration in social movements.

Overall, while Roy’s essays are thought-provoking and challenging, they also raise important ethical questions about the way we engage in public discourse and activism. As readers, it is important to critically examine not only the content of her essays but also the ethical implications of her writing.

The Historical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays have had a significant impact on the historical and political discourse in India. Her writings have challenged the dominant narratives of the Indian state and its policies, particularly in relation to issues of caste, gender, and environmental justice. Roy’s work has also been instrumental in highlighting the struggles of marginalized communities and bringing their voices to the forefront of public discourse. Her critiques of neoliberalism and globalization have been particularly influential in shaping the political consciousness of a generation of activists and intellectuals. Overall, Roy’s essays have played a crucial role in shaping the historical and political landscape of contemporary India.

The Literary Implications of Roy’s Essays

Arundhati Roy’s essays from 2016 are not only politically charged but also have significant literary implications. Roy’s writing style is poetic and evocative, and she often uses metaphors and imagery to convey her message. Her essays are not just political commentary but also works of art that challenge the reader’s imagination. Roy’s use of language is powerful and emotive, and she has a unique ability to capture the essence of a moment or an idea in a few well-chosen words. Her essays are a testament to the power of literature to inspire and provoke change. Roy’s work is a reminder that literature can be a tool for social and political transformation, and that writers have a responsibility to use their craft to speak truth to power.

The Philosophical Implications of Roy’s Essays

Roy’s essays from 2016 have significant philosophical implications that are worth exploring. One of the most prominent themes in her writing is the idea of power and its corrupting influence. She argues that those in positions of power often abuse their authority and exploit the less privileged for their own gain. This raises important questions about the nature of power and its relationship to morality. Is power inherently corrupting, or can it be wielded in a just and ethical manner? Roy’s essays suggest that the answer is not clear-cut and that we must be vigilant in holding those in power accountable for their actions. Another philosophical implication of Roy’s writing is the importance of empathy and compassion. She frequently highlights the suffering of marginalized communities and calls for greater empathy and understanding towards their struggles. This raises questions about the nature of morality and our obligations to others. Should we prioritize the well-being of others over our own self-interest, or is it possible to strike a balance between the two? Roy’s essays suggest that empathy and compassion are essential for creating a more just and equitable society. Overall, Roy’s essays offer important insights into some of the most pressing philosophical questions of our time.

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read

- Will America tear itself apart? The Supreme Court, 2020 elections and a looming constitutional crisis

- Loneliness and me

- Yuval Noah Harari: the world after coronavirus | Free to read

- America the beautiful: three generations in the struggle for civil rights | Free to read

- Splendid isolation: the long way home

- The rise and fall of the office

Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on x (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal’ | Free to read on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Arundhati Roy

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Who can use the term “gone viral” now without shuddering a little? Who can look at anything any more — a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables — without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?

Who can think of kissing a stranger, jumping on to a bus or sending their child to school without feeling real fear? Who can think of ordinary pleasure and not assess its risk? Who among us is not a quack epidemiologist, virologist, statistician and prophet? Which scientist or doctor is not secretly praying for a miracle? Which priest is not — secretly, at least — submitting to science?

And even while the virus proliferates, who could not be thrilled by the swell of birdsong in cities, peacocks dancing at traffic crossings and the silence in the skies?

The number of cases worldwide this week crept over a million . More than 50,000 people have died already. Projections suggest that number will swell to hundreds of thousands, perhaps more. The virus has moved freely along the pathways of trade and international capital, and the terrible illness it has brought in its wake has locked humans down in their countries, their cities and their homes.

But unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow. It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest — thus far — in the richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism to a juddering halt. Temporarily perhaps, but at least long enough for us to examine its parts, make an assessment and decide whether we want to help fix it, or look for a better engine.

The mandarins who are managing this pandemic are fond of speaking of war. They don’t even use war as a metaphor, they use it literally. But if it really were a war, then who would be better prepared than the US? If it were not masks and gloves that its frontline soldiers needed, but guns, smart bombs, bunker busters, submarines, fighter jets and nuclear bombs, would there be a shortage?

Night after night, from halfway across the world, some of us watch the New York governor ’s press briefings with a fascination that is hard to explain. We follow the statistics, and hear the stories of overwhelmed hospitals in the US, of underpaid, overworked nurses having to make masks out of garbage bin liners and old raincoats, risking everything to bring succour to the sick. About states being forced to bid against each other for ventilators, about doctors’ dilemmas over which patient should get one and which left to die. And we think to ourselves, “My God! This is America !”

The tragedy is immediate, real, epic and unfolding before our eyes. But it isn’t new. It is the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for years. Who doesn’t remember the videos of “patient dumping” — sick people, still in their hospital gowns, butt naked, being surreptitiously dumped on street corners? Hospital doors have too often been closed to the less fortunate citizens of the US. It hasn’t mattered how sick they’ve been, or how much they’ve suffered.

At least not until now — because now, in the era of the virus, a poor person’s sickness can affect a wealthy society’s health. And yet, even now, Bernie Sanders, the senator who has relentlessly campaigned for healthcare for all, is considered an outlier in his bid for the White House, even by his own party.

The tragedy is the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for years

And what of my country, my poor-rich country, India, suspended somewhere between feudalism and religious fundamentalism, caste and capitalism, ruled by far-right Hindu nationalists?

In December, while China was fighting the outbreak of the virus in Wuhan, the government of India was dealing with a mass uprising by hundreds of thousands of its citizens protesting against the brazenly discriminatory anti-Muslim citizenship law it had just passed in parliament.

The first case of Covid-19 was reported in India on January 30, only days after the honourable chief guest of our Republic Day Parade, Amazon forest-eater and Covid-denier Jair Bolsonaro , had left Delhi. But there was too much to do in February for the virus to be accommodated in the ruling party’s timetable. There was the official visit of President Donald Trump scheduled for the last week of the month. He had been lured by the promise of an audience of 1m people in a sports stadium in the state of Gujarat. All that took money, and a great deal of time.

Then there were the Delhi Assembly elections that the Bharatiya Janata Party was slated to lose unless it upped its game, which it did, unleashing a vicious, no-holds-barred Hindu nationalist campaign, replete with threats of physical violence and the shooting of “traitors”.

It lost anyway. So then there was punishment to be meted out to Delhi’s Muslims, who were blamed for the humiliation. Armed mobs of Hindu vigilantes, backed by the police, attacked Muslims in the working-class neighbourhoods of north-east Delhi. Houses, shops, mosques and schools were burnt. Muslims who had been expecting the attack fought back. More than 50 people, Muslims and some Hindus, were killed.

Thousands moved into refugee camps in local graveyards. Mutilated bodies were still being pulled out of the network of filthy, stinking drains when government officials had their first meeting about Covid-19 and most Indians first began to hear about the existence of something called hand sanitiser.

March was busy too. The first two weeks were devoted to toppling the Congress government in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and installing a BJP government in its place. On March 11 the World Health Organization declared that Covid-19 was a pandemic. Two days later, on March 13, the health ministry said that corona “is not a health emergency”.

Finally, on March 19, the Indian prime minister addressed the nation. He hadn’t done much homework. He borrowed the playbook from France and Italy. He told us of the need for “social distancing” (easy to understand for a society so steeped in the practice of caste) and called for a day of “people’s curfew” on March 22. He said nothing about what his government was going to do in the crisis, but he asked people to come out on their balconies, and ring bells and bang their pots and pans to salute health workers.

He didn’t mention that, until that very moment, India had been exporting protective gear and respiratory equipment, instead of keeping it for Indian health workers and hospitals.

Not surprisingly, Narendra Modi’s request was met with great enthusiasm. There were pot-banging marches, community dances and processions. Not much social distancing. In the days that followed, men jumped into barrels of sacred cow dung, and BJP supporters threw cow-urine drinking parties. Not to be outdone, many Muslim organisations declared that the Almighty was the answer to the virus and called for the faithful to gather in mosques in numbers.

On March 24, at 8pm, Modi appeared on TV again to announce that, from midnight onwards, all of India would be under lockdown . Markets would be closed. All transport, public as well as private, would be disallowed.

He said he was taking this decision not just as a prime minister, but as our family elder. Who else can decide, without consulting the state governments that would have to deal with the fallout of this decision, that a nation of 1.38bn people should be locked down with zero preparation and with four hours’ notice? His methods definitely give the impression that India’s prime minister thinks of citizens as a hostile force that needs to be ambushed, taken by surprise, but never trusted.

Locked down we were. Many health professionals and epidemiologists have applauded this move. Perhaps they are right in theory. But surely none of them can support the calamitous lack of planning or preparedness that turned the world’s biggest, most punitive lockdown into the exact opposite of what it was meant to achieve.

The man who loves spectacles created the mother of all spectacles.

As an appalled world watched, India revealed herself in all her shame — her brutal, structural, social and economic inequality, her callous indifference to suffering.

The lockdown worked like a chemical experiment that suddenly illuminated hidden things. As shops, restaurants, factories and the construction industry shut down, as the wealthy and the middle classes enclosed themselves in gated colonies, our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens — their migrant workers — like so much unwanted accrual.

Many driven out by their employers and landlords, millions of impoverished, hungry, thirsty people, young and old, men, women, children, sick people, blind people, disabled people, with nowhere else to go, with no public transport in sight, began a long march home to their villages. They walked for days, towards Badaun, Agra, Azamgarh, Aligarh, Lucknow, Gorakhpur — hundreds of kilometres away. Some died on the way.

Our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens like so much unwanted accrual

They knew they were going home potentially to slow starvation. Perhaps they even knew they could be carrying the virus with them, and would infect their families, their parents and grandparents back home, but they desperately needed a shred of familiarity, shelter and dignity, as well as food, if not love.

As they walked, some were beaten brutally and humiliated by the police, who were charged with strictly enforcing the curfew. Young men were made to crouch and frog jump down the highway. Outside the town of Bareilly, one group was herded together and hosed down with chemical spray.

A few days later, worried that the fleeing population would spread the virus to villages, the government sealed state borders even for walkers. People who had been walking for days were stopped and forced to return to camps in the cities they had just been forced to leave.

Among older people it evoked memories of the population transfer of 1947, when India was divided and Pakistan was born. Except that this current exodus was driven by class divisions, not religion. Even still, these were not India’s poorest people. These were people who had (at least until now) work in the city and homes to return to. The jobless, the homeless and the despairing remained where they were, in the cities as well as the countryside, where deep distress was growing long before this tragedy occurred. All through these horrible days, the home affairs minister Amit Shah remained absent from public view.

When the walking began in Delhi, I used a press pass from a magazine I frequently write for to drive to Ghazipur, on the border between Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

The scene was biblical. Or perhaps not. The Bible could not have known numbers such as these. The lockdown to enforce physical distancing had resulted in the opposite — physical compression on an unthinkable scale. This is true even within India’s towns and cities. The main roads might be empty, but the poor are sealed into cramped quarters in slums and shanties.

Every one of the walking people I spoke to was worried about the virus. But it was less real, less present in their lives than looming unemployment, starvation and the violence of the police. Of all the people I spoke to that day, including a group of Muslim tailors who had only weeks ago survived the anti-Muslim attacks, one man’s words especially troubled me. He was a carpenter called Ramjeet, who planned to walk all the way to Gorakhpur near the Nepal border.

“Maybe when Modiji decided to do this, nobody told him about us. Maybe he doesn’t know about us”, he said.

“Us” means approximately 460m people.

State governments in India (as in the US) have showed more heart and understanding in the crisis. Trade unions, private citizens and other collectives are distributing food and emergency rations. The central government has been slow to respond to their desperate appeals for funds. It turns out that the prime minister’s National Relief Fund has no ready cash available. Instead, money from well-wishers is pouring into the somewhat mysterious new PM-CARES fund. Pre-packaged meals with Modi’s face on them have begun to appear.

In addition to this, the prime minister has shared his yoga nidra videos, in which a morphed, animated Modi with a dream body demonstrates yoga asanas to help people deal with the stress of self-isolation.

The narcissism is deeply troubling. Perhaps one of the asanas could be a request-asana in which Modi requests the French prime minister to allow us to renege on the very troublesome Rafale fighter jet deal and use that €7.8bn for desperately needed emergency measures to support a few million hungry people. Surely the French will understand.

As the lockdown enters its second week, supply chains have broken , medicines and essential supplies are running low. Thousands of truck drivers are still marooned on the highways, with little food and water. Standing crops, ready to be harvested, are slowly rotting.

The economic crisis is here. The political crisis is ongoing. The mainstream media has incorporated the Covid story into its 24/7 toxic anti-Muslim campaign. An organisation called the Tablighi Jamaat, which held a meeting in Delhi before the lockdown was announced, has turned out to be a “super spreader”. That is being used to stigmatise and demonise Muslims. The overall tone suggests that Muslims invented the virus and have deliberately spread it as a form of jihad.

The Covid crisis is still to come. Or not. We don’t know. If and when it does, we can be sure it will be dealt with, with all the prevailing prejudices of religion, caste and class completely in place.

Today (April 2) in India, there are almost 2,000 confirmed cases and 58 deaths. These are surely unreliable numbers, based on woefully few tests. Expert opinion varies wildly. Some predict millions of cases. Others think the toll will be far less. We may never know the real contours of the crisis, even when it hits us. All we know is that the run on hospitals has not yet begun.

India’s public hospitals and clinics — which are unable to cope with the almost 1m children who die of diarrhoea, malnutrition and other health issues every year, with the hundreds of thousands of tuberculosis patients (a quarter of the world’s cases), with a vast anaemic and malnourished population vulnerable to any number of minor illnesses that prove fatal for them — will not be able to cope with a crisis that is like what Europe and the US are dealing with now.

All healthcare is more or less on hold as hospitals have been turned over to the service of the virus. The trauma centre of the legendary All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi is closed, the hundreds of cancer patients known as cancer refugees who live on the roads outside that huge hospital driven away like cattle.

People will fall sick and die at home. We may never know their stories. They may not even become statistics. We can only hope that the studies that say the virus likes cold weather are correct (though other researchers have cast doubt on this). Never have a people longed so irrationally and so much for a burning, punishing Indian summer.

What is this thing that has happened to us? It’s a virus, yes. In and of itself it holds no moral brief. But it is definitely more than a virus. Some believe it’s God’s way of bringing us to our senses. Others that it’s a Chinese conspiracy to take over the world.

Whatever it is, coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

Arundhati Roy ’s latest novel is ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’

Copyright © Arundhati Roy 2020

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call , where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple , Spotify , or wherever you listen.

Letter in response to this article:

Indian government must support the apparel sector / From Rajendra Aneja, Aneja Management Consultants, Mumbai, India

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Life & Arts Add to myFT

- Coronavirus Add to myFT

- India Add to myFT

- Arundhati Roy Add to myFT

International Edition

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Arundhati Roy, the Not-So-Reluctant Renegade

By Siddhartha Deb

- March 5, 2014

“I’ve always been slightly short with people who say, ‘You haven’t written anything again,’ as if all the nonfiction I’ve written is not writing,” Arundhati Roy said.

It was July, and we were sitting in Roy’s living room, the windows closed against the heat of the Delhi summer. Delhi might be roiled over a slowing economy, rising crimes against women and the coming elections, but in Jor Bagh, an upscale residential area across from the 16th-century tombs of the Lodi Gardens, things were quiet. Roy’s dog, Filthy, a stray, slept on the floor, her belly rising and falling rhythmically. The melancholy cry of a bird pierced the air. “That’s a hornbill,” Roy said, looking reflective.

Roy, perhaps best known for “The God of Small Things,” her novel about relationships that cross lines of caste, class and religion, one of which leads to murder while another culminates in incest, had only recently turned again to fiction. It was another novel, but she was keeping the subject secret for now. She was still trying to shake herself free of her nearly two-decade-long role as an activist and public intellectual and spoke, with some reluctance, of one “last commitment.” It was more daring than her attacks on India’s occupation of Kashmir, the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan or crony capitalism. This time, she had taken on Mahatma Gandhi.

She’d been asked by a small Indian press, Navayana, to write an introduction to a new edition of “The Annihilation of Caste.” Written in 1936 by B. R. Ambedkar, the progressive leader who drafted the Indian Constitution and converted to Buddhism, the essay is perhaps the most famous modern-day attack on India’s caste system. It includes a rebuke of Gandhi, who wanted to abolish untouchability but not caste. Ambedkar saw the entire caste system as morally wrong and undemocratic. Reading Ambedkar’s and Gandhi’s arguments with each other, Roy became increasingly dismayed with what she saw as Gandhi’s regressive position. Her small introductory essay grew larger in her mind, “almost a little book in itself.” It would not pull its punches when it came to Gandhi and therefore would likely prove controversial. Even Ambedkar ran into difficulties. His views were considered so provocative that he was forced to self-publish. The more she spoke of it, the more mired in complications this last commitment of hers seemed.

Roy led me into the next room, where books and journals were scattered around the kitchen table that serves as her desk. The collected writings of Ambedkar and Gandhi, voluminous and in combat with each other, sat in towering stacks, bookmarks tucked between the pages. The notebook in which Roy had been jotting down her thoughts in small, precise handwriting lay open on the table, a fragile intermediary in a nearly century-old debate between giants.

“I got into trouble in the past for my nonfiction,” Roy said, “and I swore, ‘I’m never going to write anything with a footnote again.’ ” It’s a promise she has so far been unable to keep. “I’ve been gathering the thoughts for months, struggling with the questions, shocked by what I’ve been reading,” she said, when I asked if she had begun the essay. “I know that when it comes out, a lot is going to happen. But it’s something I need to do.”

In her late 30s , Roy was perhaps India’s most famous writer. The publication of “The God of Small Things” in 1997 coincided with the 50th anniversary of India’s independence. It was the beginning of an aggressively nationalist, consumerist phase, and Roy was seen as representative of Brand India. The novel, her first, appeared on the New York Times best-seller list and won the Booker Prize. It went on to sell more than six million copies. British tabloids published bewildering profiles (“A 500,000-pound book from the pickle-factory outcast”), while magazines photographed her — all cascading waves of hair and high cheekbones — against the pristine waterways and lush foliage of Kerala, where the novel was set and which was just beginning to take off as a tourist destination.

Roy’s tenure as a national icon came to an abrupt end when, a year later, the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (B.J.P.) government carried out a series of nuclear tests. These were widely applauded by Indians who identified with Hindu nationalism, many of them members of the rising middle class. In an essay titled, “The End of Imagination,” Roy accused supporters of the tests of reveling in displays of military power — embracing the jingoism that had brought the B.J.P. to power for only the second time since independence — instead of addressing the abysmal conditions in which a majority of Indians lived. Published simultaneously in the English-language magazines Outlook and Frontline, the essay marked her beginning as an overtly political writer.

Roy’s political turn angered many in her upper-caste, urban, English-speaking audience, even as it attracted another. Most of her new fans had never heard of her novel; they often spoke languages other than English and felt marginalized because of their religion, caste or ethnicity, left behind by India’s economic rise. They devoured the essays Roy began writing, which were distributed in unauthorized translations, and flocked to rallies to hear her speak. “There was all this resentment, quite understandable, about ‘The God of Small Things,’ that here was this person writing in English winning all this money,” Roy said. “So when ‘The End of Imagination’ came out, there was a reversal, an anger among the English-speaking people, but also an embrace from everyone else.”

The vehemence of the response surprised her. “There is nothing in ‘The God of Small Things’ that is at odds with what I went on to write politically over 15 years,” Roy said. “It’s instinctive territory.” It is true that her novel also explored questions of social justice. But without the armature of character and plot, her essays seemed didactic — or just plain wrong — to her detractors, easy stabs at an India full of energy and purpose. Even those who sympathized with her views were often suspicious of her celebrity, regarding her as a dilettante. But for Roy, remaining on the sidelines was never an option. “If I had not said anything about the nuclear tests, it would have been as if I was celebrating it,” Roy said. “I was on the covers of all these magazines all the time. Not saying anything became as political as saying something.”

Roy turned next to a series of mega-dams to be built on the Narmada River. Villagers likely to be displaced by the project had been staging protests, even as India’s Supreme Court allowed construction to go forward. Roy traveled through the region, joining in the protests and writing essays criticizing the court’s decision. In 2001, a group of men accused her and other activists of attacking them at a rally outside the Supreme Court. Roy petitioned for the charges to be dismissed. The court agreed but was so offended by the language of her petition (she accused the court of attempting to “muzzle dissent, to harass and intimidate those who disagree with it”) that it held her in contempt. “Showing the magnanimity of law by keeping in mind that the respondent is a woman,” the judgment read, “and hoping that better sense and wisdom shall dawn upon the respondent in the future to serve the cause of art and literature,” Roy was to be sentenced to “simple imprisonment for one day” and a fine of 2,000 rupees.

The 2002 BBC documentary “Dam/Age” captures some of the drama around Roy’s imprisonment at the fortresslike Tihar Jail. When she emerged the next day, her transformation from Indian icon to harsh national critic was complete. Her hair, which she had shorn into a severe cut, evoked, uneasily, both ostracized woman and feisty feminist. The English-language Indian media mocked Roy for criticizing the dams, which they saw as further evidence of India’s rise. Attacks followed each of her subsequent works: her anguished denunciations of the massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002, the plans for bauxite mining in Orissa (now Odisha) by a London-based corporation called Vedanta Resources, the paramilitary operations in central India against indigenous tribal populations and ultraleft guerrillas known as Naxalites; and India’s military presence in Kashmir, where more than a half million troops hold in check a majority Muslim population that wants to secede from India.

Kashmir, over which India has fought three of its four wars against Pakistan, would become one of Roy’s defining issues. In 2010, after a series of massive protests during which teenage boys faced off against soldiers, Roy publicly remarked that “Kashmir was never an integral part of India.” In suggesting that the state of India was a mere construct, a product of partition like Pakistan, she had crossed a line. Most progressives in India haven’t gone that far. Roy soon found herself the center of a nationwide storm. A stone-throwing mob, trailed by television vans, showed up at her front door. The conservative TV channel Times Now ran slow-motion clips of her visiting Kashmir in which she looked as if she were sashaying down a catwalk, refusing to answer a reporter’s questions. Back in Delhi, Times Now convened a panel moderated by its immensely popular host, Arnab Goswami, to discuss — squeezed between headlines and a news crawl in which “anger” and “Arundhati” were the most common words — whether Roy should be arrested for sedition. When the sole Kashmiri Muslim panelist, Hameeda Nayeem, pointed out that Roy had said nothing not already believed by a majority of Kashmiris, she was cut off by Goswami. Cases were filed against Roy in courts in Bangalore and Chandigarh, accusing her of being “antinational,” “anti-human” and supposedly writing in one of her essays that “Kashmir should get freedom from naked, starving Indians.”

The apartment where I met Roy in July occupies the topmost floor of a three-story house and has all the trappings of an upper-class home — a sprawl of surrounding lawn, a high fence and a small elevator. There are few signs of her dissenter status: the stickers on her door (“We have to be very careful these days because . . .”); the books in the living room (Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, Eduardo Galeano); and, particularly unusual in the Indian context, the absence of servants (Roy lives entirely alone). Perhaps what is most telling is how Roy ended up in this house, which she used to ride past every day on her way to work, on a bicycle rented for a rupee.

Roy was born Suzanna Arundhati Roy in 1959 in Shillong, a small hill town in the northeastern fringes of India. Her mother, Mary, was from a close-knit community of Syrian Christians in Kerala. Her father, Rajib, was a Bengali Hindu from Calcutta, a manager of a tea plantation near Shillong and an alcoholic. The marriage didn’t last long, and when Roy was 2, she and her brother, Lalith, a year and a half older, returned to Kerala with their mother. Unwelcome at the family home, they moved into a cottage owned by Roy’s maternal grandfather in Ooty, in the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu.

“Then there are a lot of horrible stories,” Roy said and began to laugh. “My mother was very ill, a severe asthmatic. We thought she was dying. She would send us into town with a basket, and the shopkeepers would put food in the basket, mostly just rice with green chilies.” The family remained there until Roy was 5, defying attempts by her grandmother and uncle to turn them out of the house (inheritance laws among Syrian Christians heavily favored sons). Eventually, Roy’s mother moved back to Kerala and started a school on the premises of the local Rotary Club.

As the child of a single mother, Roy was ill at ease in the conservative Syrian Christian community. She felt more at home among the so-called lower castes or Dalits, who were kept at a distance by both Christians and upper-caste Hindus.

“Much of the way I think is by default,” she said. “Nobody paid enough attention to me to indoctrinate me.” By the time she was sent to Lawrence, a boarding school founded by a British Army officer (motto: “Never Give In”), it was perhaps too late for indoctrination. Roy, who was 10, says the only thing she remembers about Lawrence was becoming obsessed with running. Her brother, who heads a seafood-export business in Kerala, recalls her time there differently. “When she was in middle school, she was quite popular among the senior boys,” he told me, laughing. “She was also a prefect and a tremendous debater.”

Roy concedes that boarding school had its uses. “It made it easier to light out when I did,” she said. The child of what was considered a disreputable marriage and an even more disgraceful divorce, Roy was expected to have suitably modest ambitions. Her future prospects were summed up by the first college she was placed in; it was run by nuns and offered secretarial training. At 16, Roy instead moved to Delhi to study at the School of Planning and Architecture.

Roy chose architecture because it would allow her to start earning money in her second year, but also out of idealism. In Kerala, she met the British-born Indian architect Laurie Baker, known for his sustainable, low-cost buildings, and was taken with the idea of doing similar work. But she soon realized she wouldn’t learn about such things at school. “They just wanted you to be like a contractor,” Roy said, still indignant. She was grappling, she said, with questions to which her professors didn’t seem to have answers: “What is your sense of aesthetic? Whom are you designing for? Even if you’re designing a home, what is the relationship between men and women assumed in that? It just became bigger and bigger. How are cities organized? Who are laws for? Who is considered a citizen? This coalesced into something very political for me by the end of it.”

For her final project, Roy refused to design a building and instead wrote a thesis, “Postcolonial Urban Development in Delhi.” “I said: ‘Now I want to tell you what I’ve learned here. I don’t want you to tell me what I’ve learned here.’ ” Roy drew sustenance from the counterculture that existed among her fellow students, which she would represent years later in the film “In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones” (1989). She wrote, designed and appeared in it — an elfin figure with a giant Afro playing the character of Radha, who gives up architecture to become a writer but drowns before completing her first novel.

By this time, Roy had broken off contact with her family. Without money to stay in the student hostel, she moved into a nearby slum with her boyfriend, Gerard da Cunha. (They pretended to be married in deference to the slum’s conservative mores.) “It’s one thing to be a young person who decides to slum it,” Roy said. “For me, it wasn’t like that. There was nobody. There was no cuteness about it. That was my university, that period when you think from the point of view of absolute vulnerability. And that hasn’t left me.”

After graduation, she briefly lived with Da Cunha, in Goa, where he was from, but they broke up, and she returned to Delhi. She got a job at the National Institute of Urban Affairs, and met Pradip Krishen, an independent filmmaker who offered Roy the female lead in “Massey Sahib” (1985), a film set in colonial India in which Roy played a goatherd. Roy and Krishen, who later married, collaborated on subsequent projects, including “Bargad,” a 26-part television series on India’s independence movement that was never completed, as well as two feature films, “Annie” and “Electric Moon” (1992).

Krishen’s background could not have been more different from Roy’s. A Balliol scholar and former history professor, Krishen, a widower, lived with his parents and two children in a sprawling house in the posh Chanakyapuri neighborhood. When Roy joined him, they moved to a separate apartment upstairs. Roy immersed herself in Delhi’s independent-filmmaking world. The movies’ progressive themes appealed to her, but it was a world dominated by the scions of elite families, and it soon came to seem out of touch and insular to her. She spent more and more time teaching aerobics, to earn her own money, and hanging out with artists she met in school.

She had already begun work on her novel when “The Bandit Queen,” a film, based on the life of the female bandit Phoolan Devi, was released. Devi was a low-caste woman who became a famous gang leader and endured gang rape and imprisonment. Roy was incensed by the way the film portrayed her as a victim whose life was defined by rape instead of rebellion. “When I saw the film, I was infuriated, partly because I had grown up in Kerala, being taken to these Malayalam films, where in every film — every film — a woman got raped,” Roy said. “For many years, I believed that all women got raped. Then I read in the papers how Phoolan Devi said it was like being raped again. I read the book the film was based on and realized that these guys had added their own rapes. . . . I thought, You’ve changed India’s most famous bandit into history’s most famous rape victim.” Roy’s essay on the film, “The Great Indian Rape Trick,” published in the now-defunct Sunday magazine, eviscerated the makers of “Bandit Queen,” pointing out that they never even bothered to meet Phoolan Devi or to invite her to a screening.

The piece alienated many of the people Roy worked with. Krishen, who gives the impression of a flinty loyalty toward Roy even though the couple split up, says it was seen as a betrayal in the tightknit film circles of Delhi. For Roy, it was a lesson in how the media worked. “I watched very carefully what happened to Phoolan Devi,” she said. “I saw how the media can just excavate you and leave a shell behind. And I was lucky to learn from that. So when my turn came, the barricades were up.”

When I met Roy at the New Delhi airport a few days after we first talked, she hung back from the crowd, ignoring the stares coming her way. She had turned down a request to address a public gathering in Kashmir, but there still seemed something political about traveling there just a week after eight Indian soldiers were killed in an ambush. The passengers on the flight Roy and I took, Hindu pilgrims visiting the Amarnath shrine, certainly thought so. Periodically, they filled the small aircraft with cries of “Bom Bhole,” or “Hail Shiva,” their right fists rising in unison. Once in Srinagar, the capital, Roy was stopped often by Kashmiris who wanted to thank her for speaking up against the Indian state. They also hoped she would agree to have her picture taken with them. She usually did.

But for the most part, she kept out of the public eye. Roy was staying at the house of a journalist friend, and as he and another journalist talked on their mobile phones, following a story about a fight that had broken out between Amarnath pilgrims and Kashmiri porters, she distributed packs of Lavazza coffee brought from Delhi, only half listening. Later, she declined to attend the screening of a new documentary about the Naxalite guerrillas, preferring to work on her novel.

Roy had come to Kashmir mainly to see friends, but it was hard to escape the strife altogether. A few days later, we drove through the countryside, a landscape of streams sparkling through green fields and over cobblestones, punctuated by camouflaged, gun-toting figures. Sometimes they were a detachment of the Central Reserve Police Force, sometimes the local police and, every now and then, distinctive in their flat headgear, soldiers of the counterinsurgency Rashtriya Rifles. “There were bunkers all over Srinagar when I first began coming here,” Roy said. “Now they use electronic surveillance for the city. The overt policing is for the countryside.”

In Srinagar earlier that week, the policing had seemed overt enough. Roy had been invited to speak at a gathering organized by Khurram Parvez, who works for the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, an organization that has produced extensive reports on mass graves and extrajudicial killings in Kashmir. As 40 or so people sat cross-legged on the floor — activists, lawyers, journalists and students — Parvez asked that cellphones be turned off and placed in “thighland” in order to prevent surreptitious recordings that could be passed on to authorities.

Roy put on reading glasses, and these, along with the stack of books in front of her, a selection of the nonfiction she has written over the past 15 years (just brought out by Penguin India as a box set of five candy-colored volumes), gave the gathering the air of an impromptu seminar. Roy began by asking audience members to discuss what was on their minds. A young lawyer who grew up in a village about 30 miles from Srinagar told a story of two women, who, after being raped by soldiers, spent the night shivering in separate bathing cabins, too ashamed to go home, hearing only each other’s weeping. Roy listened carefully to this and similar accounts, occasionally nudging the conversation beyond Kashmir, to the rifts and fractures within India itself, including the forests of central India, where she spent more than two weeks in 2010 with ultraleft guerrillas and their tribal allies for her last book, “Broken Republic” (2011).

“I feel sad, you know, when I’m traveling in India and see Kashmiris who’ve been recruited into the Border Security Force,” she said. “It’s what this state does, hiring from one part of the country and sending them to fight in other parts, against people who on the surface might seem different but who are actually facing the same kind of oppression, and this is why perhaps it’s important to be able to talk to each other.”

She picked up one of the books in front of her, the lemon-yellow “Listening to Grasshoppers,” and found a passage from the essay “Azadi,” or “Freedom.” In it, she describes attending a 2008 rally in Srinagar demanding independence from India. “The slogan that cut through me like a knife,” she read in a quiet, clear voice, “was this one: Nanga bhooka Hindustan, jaan se pyaara Pakistan ” — India is a naked, starving country; Pakistan is more precious to us than life itself. “In that slogan,” she said, “I saw the seeds of how easily victims can become perpetrators.”

The discussion went on for hours, spanning global capitalism and climate change, before returning to Kashmir. Did Kashmiris identify with Pakistan? Some did, some emphatically did not. What about the role of women in the struggle for Kashmiri self-determination? How could they make themselves heard when they found it so difficult to make themselves heard in this room? In the fierce summer heat, the group, splintered into factions, growing tired and agitated. Roy decided to bring the proceedings to a close with a joke from Monty Python’s “Life of Brian.”

“In the movie, this man, Brian, asks a band of guerrilla fighters, ‘Are you the Judean Peoples’ Front?’ ” Roy said, mimicking a British accent. “And the reply he gets from this really offended group is: No, absolutely not. ‘We’re the Peoples’ Front of Judea.’ ” The joke, an elaborate parody of radical factionalism, made Roy laugh heartily. It also changed the emotional temperature of the room. As we came out of the house and milled around in the alley, the various groups seemed easier with each other. Later, a young man who had just completed a degree in fiction would express to me his disappointment that the conversation had never turned to writing at all.

Beyond the Gandhi book , there has been much to pull Roy away from fiction. In May, when Naxalite guerrillas killed at least 24 people, including a Congress politician who had formed a brutal right-wing militia and whom Roy criticized in her last book, she was immediately asked for a comment but declined to talk. “So they just republished an old interview I had given and tried to pretend it was a new interview,” she said.

“The things I’ve needed to say directly, I’ve said already,” she said. “Now I feel like I would be repeating myself with different details.” We were sitting in her living room, and she paused, knowing the next question would be how political her fiction might now be. “I’m not a person who likes to use fiction as a means. I think it’s an irreducible thing, fiction. It’s itself. It’s not a movie, it’s not a political tract, it’s not a slogan. The ways in which I have thought politically, the proteins of that have to be broken down and forgotten about, until it comes out as the sweat on your skin.”

But publishing is a risky venture in India these days; court orders are used to prevent books from coming out or to remove them from circulation, even when they are not explicitly political. Most recently, Penguin India pulped all existing copies of “The Hindus: An Alternative History,” by Wendy Doniger, after a conservative Hindu pressure group initiated a case against the book. Penguin also publishes Roy, and she felt compelled to protest.

Although Roy won’t divulge, even to her closest friends, what her new novel is about, she is adamant that it represents a break from both her nonfiction and her first novel. “I’m not trying to write ‘The God of Small Things’ again,” she said. “There’s much more grappling conceptually with the new novel. It is much easier for a book about a family — which is what ‘The God of Small Things’ was — to have a clear emotional heart.” Before she became caught up in her essay on Ambedkar and Gandhi, she was working on the novel by drawing, as she tends to do in the early stages, trying to figure out the structure. She then writes longhand. What she calls the “sandpapering” takes place on a laptop, at her kitchen table.

“I’m not attached to any particular space,” she said when I asked her how important the routine was to her writing. “I just don’t need to feel that someone’s breathing over me.”

After “The God of Small Things” was published, she began to give some of the money she made from it away. She sent her father, who resurfaced after she appeared in “Massey Sahib” and was not above trying to extort money from her, to a rehab center. (He died in 2007.) In 2002, when Roy received a Lannan Foundation award, she donated the $350,000 prize money to 50 small organizations around India. Finally, in 2006, she and her friends set up a trust into which she began putting all her nonfiction earnings to support progressive causes around the country.

“I was never interested in just being a professional writer where you wrote one book that did very well, you wrote another book, and so on,” Roy said, thinking of the ways in which “The God of Small Things” trapped her and freed her. “There’s a fear that I have, that because you’re famous, or because you’ve done something, everybody wants you to keep on doing the same thing, be the same person, freeze you in time.” Roy was talking of the point in her life when, tired of the images she saw of herself — the glamorous Indian icon turned glamorous Indian dissenter — she cut off her hair. But you could see how she might say the same of the position in which she now finds herself. The essay on Gandhi and Ambedkar was meant to complete one set of expectations before she could turn to something new. “I don’t want that enormous baggage,” Roy said. “I want to travel light.”

Published August 22nd, 2022

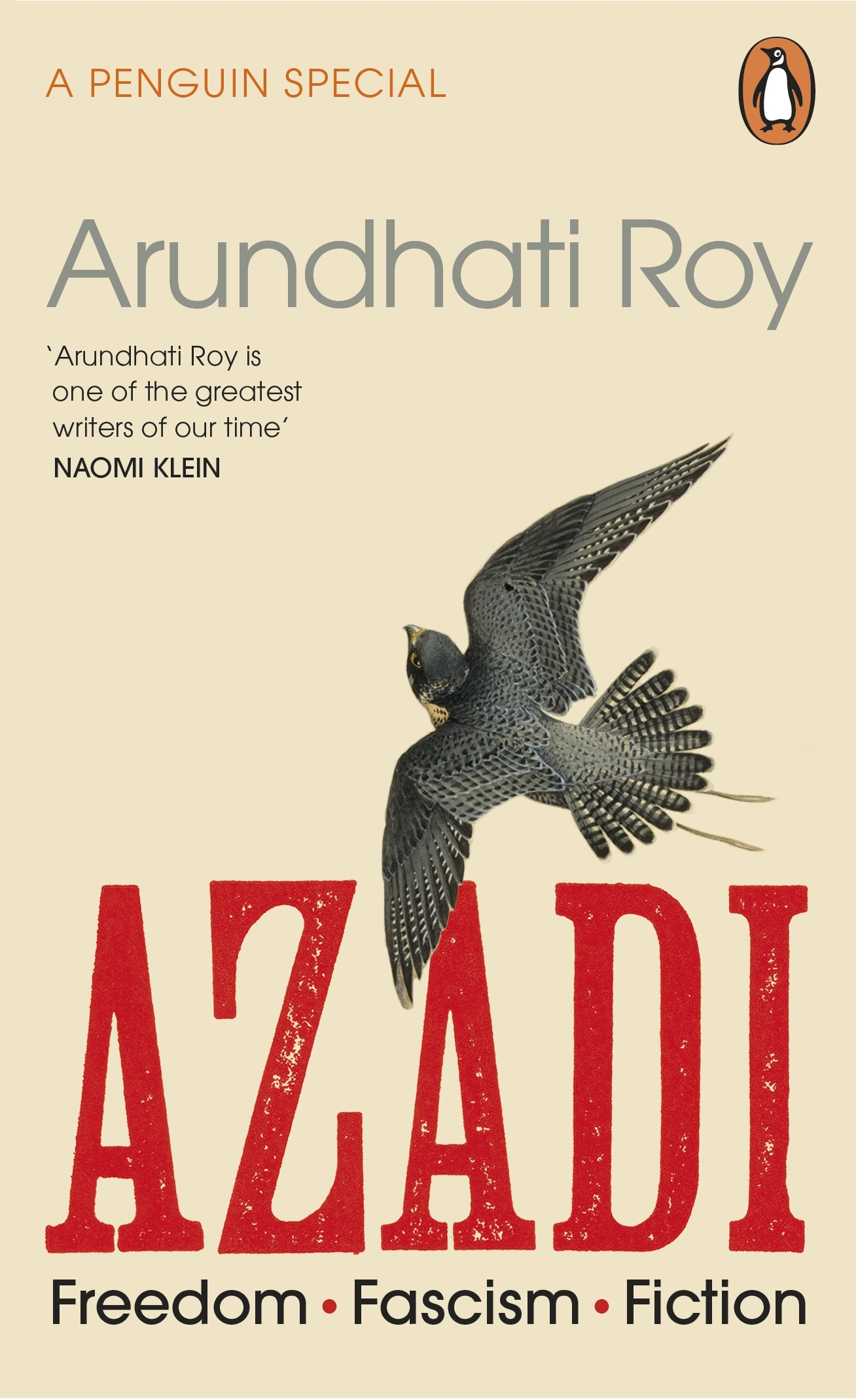

The Ministress of the Political Essay — A Review of Arundhati Roy’s "Azadi"

by Sam Dapanas

In her 2020 collection of essays, Indian novelist, activist and essayist Arundhati Roy takes up questions of language, cultural belonging, literature and politics, up to the 2020 COVID pandemic. While taking the form of political essays, a form of writing with a long tradition in the English language, Roy’s pieces weave in and out of genres, chasing hard questions and suggesting provocative answers, in a never-ending confrontation between the colonial legacy of the Empire and the rich and multi-faceted identities of post-colonial countries.

I first read Arundhati Roy in a postcolonial literature class as an undergraduate English major, thanks to my Asianist professor back then who is a dramaturgist, theater director, and cultural studies scholar. Despite the grueling experience of reading The God of Small Things ’ first 100 pages (god, yes it was!), I loved it so much that I wrote a lengthy book review — one of the class’s final requirements — about it. Years later, her second novel would come out. I bought one of the first copies that arrived at the local bookstore. Reading Arundhati Roy’s nonfiction and essays in Azadi (which means ‘freedom’ in several Persian languages) and in My Seditious Heart: Collected Nonfiction (2019), I must say it made me understand further where the characters from her fiction, some nitpicked from real people in her life, are coming from. “In What Language Does Rain Fall In Tormented Cities?” the essay, a homage to a line from Pablo Neruda’s Libro de Preguntas (or The Book of Questions ), which serves as the first chapter of Azadi: Fascism, Freedom, Fiction , Roy gives us a glimpse of her creative process, pre- and post-writing, behind The Ministry of Utmost Happiness , her second novel, which was published in 2017.

Said piece was possibly the essay that stroke the strongest chord in me and that had resonance in me as a reader. Coming from a multilingual, if not translingual, community — outside the capital Manila, a typical Filipino child would learn English and (Tagalog-based) Filipino in school and the media, the native tongue at home, and because of the well-intentioned, poorly executed Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB MLE) policy, possibly another non-Tagalog language taught in school if one’s mother language is not the same dominant one in the region where one lives in — I know exactly the ‘slow violence’ of linguistic genocide. Perhaps as a rumination on her case, Roy wrote:

I fell to wondering what my mother tongue actually was. What was — is — the politically correct, culturally apposite, and morally appropriate language in which I ought to think and write? It occurred to me that my mother was actually an alien, with fewer arms than Kali perhaps but many more tongues. English is certainly one of them. My English has been widened and deepened by the rhythms and cadences of my alien mother’s other tongues. I say alien because there’s not much that is organic about her. Her nation-shaped body was first violently assimilated and then violently dismembered by an imperial British quill. I also say alien because the violence unleashed in her name on those who do not wish to belong to her (Kashmiris, for example), as well as on those who do (Indian Muslims and Dalits, for example), makes her an extremely unmotherly mother.

In A Brief History of the Political Essay , David Bromwich, himself a scholar of Western literary and philosophical canon, locates the political essay within the Euro-American tradition, from Jonathan Swift’s satires to Virginia Woolf’s memoirs, as having “never been a clearly defined genre.” Never been . A body of writings across cultures and eras exists but there is no strict definition of what works are confined within it and what works on the outside are not. But in Azadi, Arundhati Roy shows us, in the words of another novelist from the Indian subcontinent, Salman Rushdie, how “the empire writes back.” Her essays are incisive and at the same time, insightful and provocative, dissecting through the heart of the issue, asking the right questions with precision. In “The Language of Literature,” for instance, Roy asks, “What’s the place of literature?” Or what is its role in our current times which is heavily fraught with religious fundamentalism, the strengthening of the alt Far Right, socioeconomic inequalities and unrest, and even state-funded online disinformation which is prevalent in India and in my country, and possibly everywhere? Come 2020, all these have become layered with the Covid-19 pandemic, i.e. the hoarding of vaccine supply by the Global North, corruption in the midst of pandemic response, racism as evidenced by selective travel bans, as Roy has written in “The Pandemic Is A Portal,” the last essay in the collection. True to her introduction, “Some of the essays in this volume have been written through the eyes of a novelist and the universe of her novels.”

In the larger context of “self against fact” in contemporary nonfiction writing particularly in its subgenres of literary journalism and political essays, Roy shapes and reshapes her position as a witnessing “writer-activist” (which she says people label her) foregrounded by, quoting Nicole Walker in her Creative Nonfiction magazine article The Braided Essay as a Social Justice Action , “new facts, and the facts of your personal story cut into the hard statistics of your paragraph” about political upheavals and ethnoreligious violence in India. I cite Walker because to me, the essays here, a few of them reworked versions of speeches and lectures she gave for the British Library and PEN America, to me, are in the braided form, the “most effective [form] when the political and the personal are trying to explain and understand each other … to [pull] together two disparate ideas … [a] form … of resistance … a form that expands the conversation, presses upon the hard lines of ideology.” In Azadi , Roy critiques across the political spectrum, from the fascist Right (the Hindi ultranationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) to the “casteist” Left (the Maoist Communist Party of India).

Despite, however, the bleakness of the textual realities of the essays and the lived experiences they portray, Roy, as in her novels The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, gives us a glimpse of hope, some sort of light at the end of a pitch-dark tunnel. “What lies ahead?” Roy asks and to which she answers, “Reimagining the world. Only that.”

Sam Dapanas

Nationality: Filipinx

First Language(s): Cebuano Binisaya Second Language(s): English, Tagalog-based Filipino

More about this writer

Our Mission

Our Writers

Submit & Support

Submission Guidelines

Call for Submissions

Wall of Fame

Supported by:

Get involved!

Support tint — support translingual literature.

If you like what Tint Journal does and want us to keep producing literary issues and organizing literary events for ESL writers, support us now with a subscription on Patreon. Thank you for your interest in translingual writing!

Close Subscribe now

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Arundhati Roy extract: 'The backlash came in police cases, court appearances and even jail'

Arundhati Roy reflects on her journey from novelist to activist in this extract from her new collection of political essays, My Seditious Heart

- Interview: Arundhati Roy

In the winter of 1961 the tribespeople of Kothie, a small hamlet in the western state of Gujarat, were chased off their ancestral lands as though they were intruders. Kothie quickly turned into Kevadiya Colony, a grim concrete homestead for the government engineers and bureaucrats who would, over the next few decades, build the gigantic 138.68metre-high Sardar Sarovar Dam. It was one of four mega dams – and thousands of smaller dams – that were part of the Narmada Valley Development Project, planned on the Narmada river and her 41 tributaries. The people of Kothie joined the hundreds of thousands of others whose lands and homes would be submerged – farmers, farmworkers, and fisherfolk in the plains, ancient indigenous tribespeople in the hills – to fight against what they saw as wanton destruction. Destruction, not just of themselves and their communities, but of soil, water, forests, fish, and wildlife – a whole ecosystem, an entire riparian civilisation. The material welfare of human beings was never their only concern.

Under the banner of the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save the Narmada Movement), they did everything that was humanly and legally possible under the Indian constitution to stop the dams. They were beaten, jailed, abused and called “anti-national” foreign agents who wanted to sabotage India’s “development”. They fought the Sardar Sarovar as it went up, metre by metre, for decades. They went on hunger strike, they went to court, they marched on Delhi, they sat in protest as the rising waters of the reservoir swallowed their fields and entered their homes. Still, they lost. The government reneged on every promise it had made to them. On September 17, 2017, the prime minister of India, Narendra Modi, inaugurated the Sardar Sarovar Dam. It was his birthday present to himself on the day he turned 67.

Even as they went down fighting, the people of the Narmada taught the world some profound lessons – about ecology, equity, sustainability and democracy. They taught me that we must make ourselves visible, even when we lose, whatever it is that we lose – land, livelihood, or a worldview. And that we must make it impossible for those in power to pretend that they do not know the costs and consequences of what they do. They also taught me the limitations of constitutional methods of resistance.

Today, even the harshest critics of the Narmada Bachao Andolan have had to admit that the movement was right about almost everything it said. But it’s too late.

In the last 20 years, the opening of the Indian markets to international finance has created a new middle class – a market of millions – and has had investors falling over themselves to find a foothold. The international media, for the most part, was at pains to portray the world’s favourite new finance destination in the best possible light. But the news was certainly not all good. India’s fleet of brand new billionaires and its new consumers were being created at an immense cost to its environment and to an even larger underclass. Backstage, away from the razzle-dazzle, labour laws were dismantled, trade unions disbanded. The state was withdrawing from its responsibilities to provide food, education and health care. Public assets were turned over to private corporations, massive infrastructure and mining projects were pushing hundreds of thousands of rural people off their lands into cities that didn’t want them. The poor were in freefall.

For me personally it was a time of odd disquiet. As I watched the great drama unfold, my own fortunes seemed to have been touched by magic. My first novel, The God of Small Things , had won a big international prize. I was a frontrunner in the line-up of people who were chosen to personify the confident, new, market-friendly India that was finally taking its place at the high table. It was flattering in a way, but deeply disturbing, too. As I watched people being pushed into penury, my book was selling millions of copies. My bank account was burgeoning. Money on that scale confused me. What did it really mean to be a writer in times such as these?

As I thought about this, almost without meaning to, I began to write a long, bewildering, episodic, astonishingly violent story about the complicated waltz between corporate globalisation and medieval religious fundamentalism and the trail of destruction they were leaving in their wake. And of the remarkable people who had risen to resist them.

The backlash to almost every one of the essays when I first published them – in the form of police cases, legal notices, court appearances, and even a short jail sentence – was often so wearying that I would resolve never to write another. But equally, almost every one of them – each a broken promise to myself – took me on journeys deeper and deeper into worlds that enriched my understanding, and complicated my view, of the times we live in. They opened doors for me to secret places where few are trusted, led me into the very heart of insurrections, into places of pain, rage and ferocious irreverence. On these journeys, I found my dearest friends and my truest loves. These are my real royalties, my greatest reward.

Although writers usually walk alone, most of what I wrote rose from the heart of a crowd. It was never meant as neutral commentary, pretending to be observations of a bystander. It was just another stream that flowed into the quick, immense, rushing currents that I was writing about. My contribution to our collective refusal to obediently fade away.

My collection of essays goes to press around the time that an era we think we understand is coming to a close. Capitalism’s gratuitous wars and sanctioned greed have jeopardised the life of the planet and filled it with refugees. It has done more damage to the Earth in the last 100 or so years than countless millennia that went before. In the last 30 years, the scale of damage has accelerated exponentially. The World Wildlife Fund reports that the population of vertebrates – mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles – has declined by 60% in the last 40 years. We have sentenced ourselves to an era of sudden catastrophes – wild fires and strange storms, earthquakes and flash floods. To guide us through it all, we have the steady hand of new imperialists in China, white supremacists in the White House, and benevolent neo-Nazis on the streets of Europe.

In India, Hindu fascists are marching to demand a grand temple where the mosque they demolished once stood. Farmers deep in debt are marching for their very survival. The unemployed are marching for jobs. More temples? Easy. But more jobs? As we know, the age of Artificial Intelligence is upon us. Human labour will soon become largely redundant. Humans will consume. But many will not be required to participate in (or be remunerated for) economic activity.

So, the question before us is, who – or what– will rule the world? And what will become of so many surplus people? The next 30 years will be unlike anything that we as a species have ever encountered. To prepare us for what’s coming, to give us tools with which to think about the unthinkable, old ideas – whether they come from the left, the right, or from the spectrum somewhere in between – will not do. We will need algorithms that show us how to snatch the sceptres from our slow, stupid, maddened kings. Until then, beloved reader, I leave you with … my seditious heart.

Live @ Lippmann

February 26, 2021.

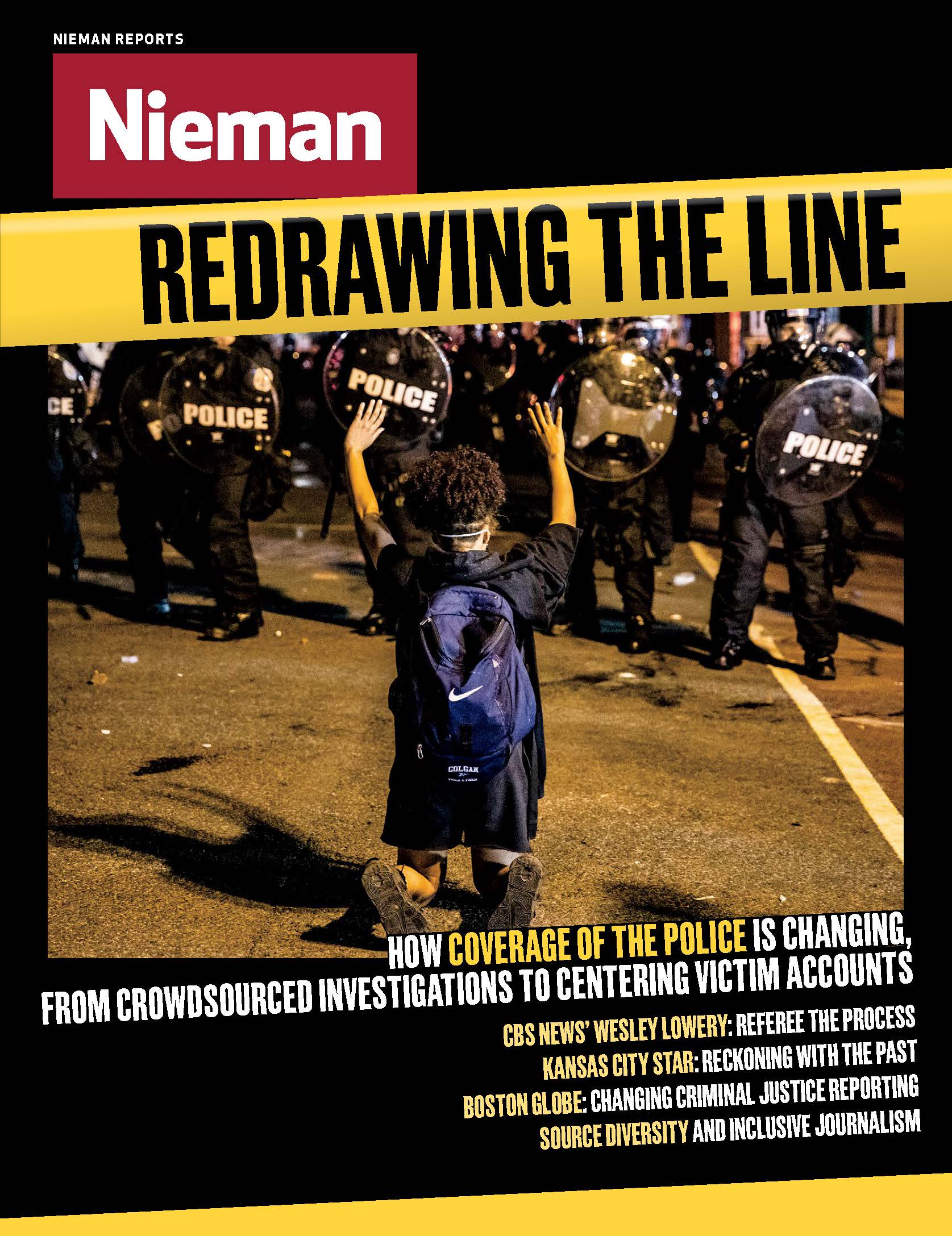

Arundhati Roy: “We Live in an Age of Mini-Massacres”

The man booker prize-winning author of “the god of small things” on the state of india’s democracy, violence against women and minorities, the role of the media, and more.

Internationally acclaimed author and activist Arundhati Roy speaks during a press conference, where the panel condemned the criminalization of the right to peaceful public protest in a democracy, in New Delhi in October 2020 Mayank Makhija/NurPhoto via AP

Arundhati Roy’s first novel, “The God of Small Things,” won the Man Booker Prize in 1997. Her second, “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,” was shortlisted for it. These books, written two decades apart, capture how India has changed. In addition to her fiction, though, Roy’s political essays taught a generation of young Indian writers to think incendiary thoughts. Her recent New Yorker profile says her essays on India ’ s nuclear policies are not so much written as breathed out in a stream of fire.

Years of increasing repression towards journalists from Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government have come to a head in recent weeks , as the country is roiled by the ongoing farmers’ protest against three farm bills passed in September 2020. Numerous journalists reporting on the protests have faced criminal charges and, in early February, some 100 journalists, publications, and activists were temporarily blocked by Twitter at the request of India’s Ministry and Electronics and Information Technology.

Related Reading

In India, Journalists “Are Fighting For Whether Truth is Meaningful or Not” By Madeleine Schwartz