Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons Essay

Introduction.

One fundamental question that comes to one’s mind is why people sell illegal drugs. However, one must note that selling of illegal drugs is a human behavior. This is a behavior, which is socially unacceptable because illegal drugs have harmful effects on their users. Generally, there are motivations and thoughts, which drive such behaviors in people. Psychology should help us to understand why people engage in selling illegal drugs. In addition, one ought to understand the role of the environment in such cases. This is antisocial personality behavior and disregard for social norms, which starts from a person’s mind.

The Situation of Selling Illegal Drugs

Drugs are important in alleviating illnesses and discomfort in people. However, there are certain regulated drugs, which are harmful to users because they cause severe health problems and addiction. As a result, authorities have banned such drugs. Nevertheless, illegal drugs find their ways in the streets. The society is aware of the prevalence of selling of illegal drugs. Majorities who sell and abuse illegal drugs are mainly youths.

Selling of illegal drugs is an act of antisocial behavior, which is socially unacceptable. Such people do not follow a set of laws, which provide order in society. Instead, they display behaviors, which do not conform to norms, and they tend to be aggressive and dishonest. The focus of individuals who sell drugs has been self-centered. The tendency to reject the expected behaviors in society originates from one’s own mind and motivations. People who sell drugs define laws, authorities, and establish their norms, which reflect criminal tendencies.

Selling illegal drugs also make such people to be aggressive and repulsive toward others because selling of illegal drugs is deviant behavior in society. It is important to understand the role of the mind and environments and their impacts on people who sell drugs. From psychological perspectives, one can understand thought processes, motivations, and intentions of people who engage in selling illegal drugs. Selling illegal drugs is usually a copied behavior that may have environmental influences based on societal norms. At the same time, it would also be important to explore the role of hereditary in such cases.

Analysis of the social, cultural, and spiritual influences on the individual’s behavior and his or her ethics

Social influences have significant impacts on behaviors of individuals who sell drugs. Such influences affect one’s thoughts, behaviors, and actions. Society and social groups are responsible for shaping illegal activities of people who engage in selling illegal drugs. In most cases, disorganized societies are responsible for antisocial behaviors among individuals. People who engage in selling illegal drugs could be from broken homes, crime zones, and unstable families, which highly influence their social behaviors and criminal conducts. Social groups may introduce a person to a culture of selling illegal drugs. A bad culture in which one grows up has a critical role in the development of a person’s antisocial behaviors and deviant tendencies like selling illegal drugs. For instance, if one associates with a bad company, it would influence him or her, and the persona may learn the group’s undesired behaviors.

People who sell illegal drugs may also have spiritual views and claim assert they do not have any controls on their behaviors or thought. Instead, they get such powers from unknown worlds. Overall, one must note that a person who sells illegal drugs may disregard ethical concepts of good or bad and choose his or her own lifestyle (Chen and Risen, 2010).

The reciprocal relationship between behavior and attitudes

People tend to focus on portraying their desired behaviors and act in a similar manner to reflect such attitudes and thinking. In this case, a person who believes in selling illegal drugs and aggression would only champion such behaviors and actions, and he or she will likely to believe in their influences. Myers shows that behaviors and attitudes have reciprocal relationships (Myers, 2010). In other words, one can think of being aggressive and act in a manner that would affect the way he or she thinks. Behaviors have the ability to project one’s thoughts and attitudes, which influence the subsequent action, particularly when one believes that he or she is responsible for his or her actions.

A person who sells illegal drugs knows that he or she causes social disorder through deviant and antisocial behaviors. Moreover, the person also knows the negative effects of illegal drugs on users. Rationalization in such people may result into ethical dilemma about the need to project good deeds and behaviors against harming others and society. Any changes in such people, to make their behaviors and attitudes consistent, result in lessening cognitive dissonance. This should create congruence between behaviors and beliefs.

Using cognitive dissonance theory to rationalize selling illegal drugs

In some cases, a person’s actions may conflict with his or her attitudes. This may lead to a change of attitudes for consistency with actions. A person who sells illegal drugs may justify his or her behavior by changing his attitudes and claim that selling illegal drugs was justified in his or her situation when faced with cognitive dissonance. The person may claim that he can only sell illegal drugs in his or her status, and this is a decision that supports his attitude toward selling drugs and being antisocial. The person believes that selling illegal drugs is important and acceptable in his or her situation. However, when he or she relieves cognitive dissonance, the person would wish to change his or her attitude and support the desired behavior (Van Veen, Krug, Schooler and Carter, 2009). This is a rationalization process.

When the person begins to rationalize his or her behavior, he or she would realize that selling illegal drugs does not improve his or her situation. Instead, it only creates unacceptable behaviors and outcomes in society. The feeling of revulsion and guilt with one’s self may make the person to change his or her behaviors (Fointiat, 2004). In addition, the person may change his attitude later if he or she faces the same situation.

Social, cultural, and spiritual influences may affect one’s behaviors and attitudes. As a result, an individual may begin to rationalize his or her behaviors and attitudes in order to establish congruence. However, this may not be the case, as it creates discomfort. Cognitive dissonance makes the person to rationalize his or her behaviors and actions in order to lessen the tension as a way of accommodating such behaviors. This is a process of attempting to justify an act of selling illegal drugs and antisocial behaviors. As a result, cognitive dissonance will help the person to establish congruence between his or her attitudes and behaviors, and lessen inner conflicts.

Chen, K., and Risen, L. (2010). How choice affects and reflects preferences: Revisiting the free-choice paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99 (4), 573-594.

Fointiat, V. (2004). I know what I have to do, but…When hypocrisy leads to behavioral change. Social Behavior and Personality, 32 , 741-746.

Myers, D. (2010). Social psychology (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Van Veen, V., Krug, K., Schooler, W., and Carter, S. (2009). Neural activity predicts attitude change in cognitive dissonance. Nature Neuroscience, 12 (11), 1469-1474. Web.

- Mental Disorders: Effects and Components

- What Is Strauss Syndrome?

- Cognitive Dissonance and Reduction Strategies

- Organizational Diagnostic Models: Congruence Model

- Cognitive Dissonance and How to Deal With It

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: Joseph Wolpe Treatment Theory

- Mental Disorders: Diagnosis and Statistics

- Psychoanalytic Theory: Understanding the Persistent Deviant

- Mood and Addictive Disorders in Psychology

- Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, June 3). Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons. https://ivypanda.com/essays/selling-illegal-drugs-psychological-reasons/

"Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons." IvyPanda , 3 June 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/selling-illegal-drugs-psychological-reasons/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons'. 3 June.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons." June 3, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/selling-illegal-drugs-psychological-reasons/.

1. IvyPanda . "Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons." June 3, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/selling-illegal-drugs-psychological-reasons/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Selling Illegal Drugs: Psychological Reasons." June 3, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/selling-illegal-drugs-psychological-reasons/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

For a limited time, your donation will be doubled!

Double your donation today!

The Appeal in Your Inbox

Subscribe to our newsletters for regular updates, analysis and context straight to your email.

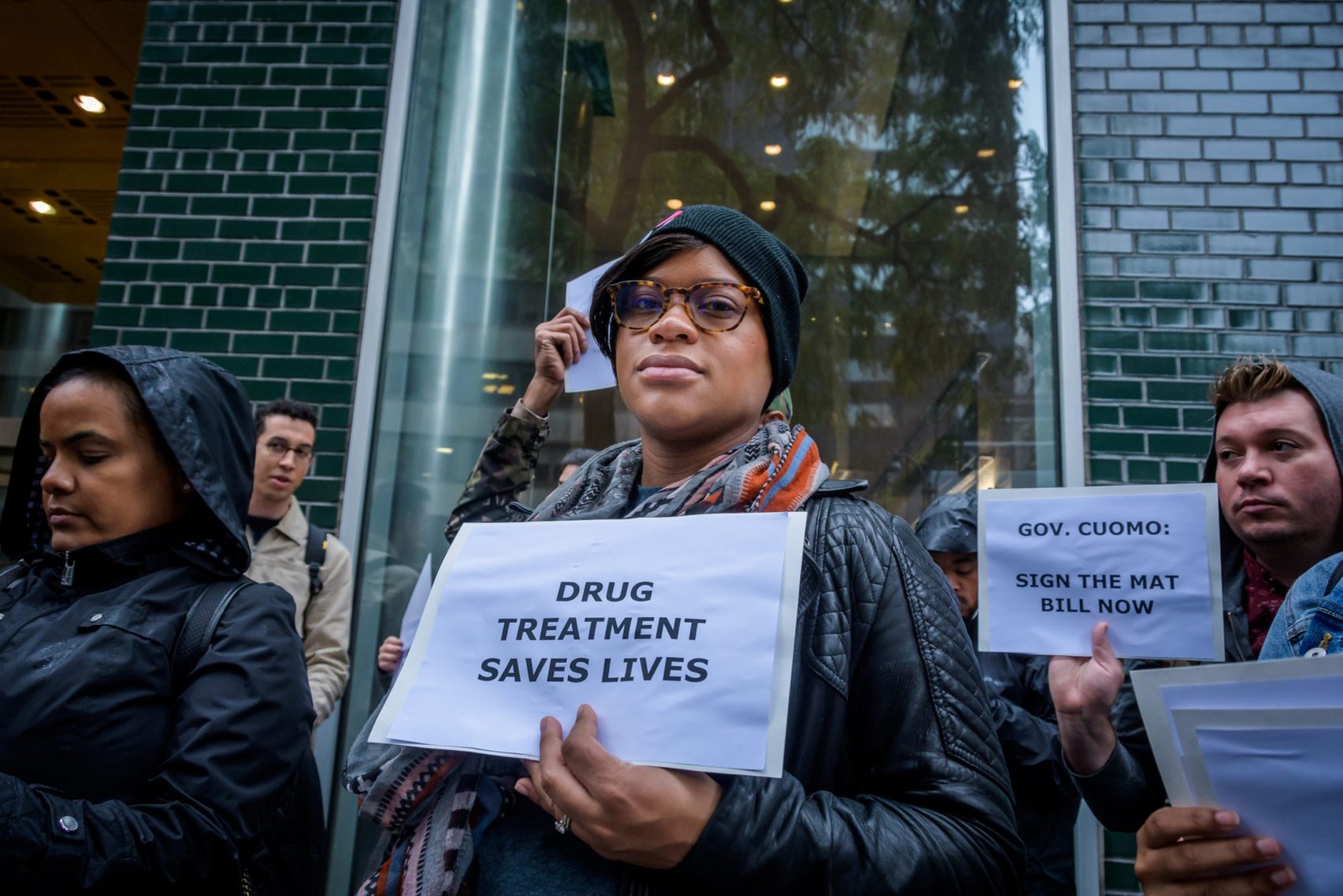

Seeing The Humanity Of People Who Sell Drugs

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. In 2014, Morgan Godvin’s best friend, Justin DeLong, experienced a fatal drug overdose. She had sold him the heroin he used. The next night, police officers raided […]

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal .

In 2014, Morgan Godvin’s best friend, Justin DeLong, experienced a fatal drug overdose. She had sold him the heroin he used. The next night, police officers raided her apartment and placed her under arrest. She was 24, and her mother had died of an overdose three months earlier. Federal prosecutors charged Godvin with “delivery resulting in death” for her friend’s overdose, a charge that she was told carried a 20-year minimum sentence. She ended up pleading guilty to conspiracy to distribute heroin and spent the next five years in prison.

Last month, in a commentary in the Washington Post, Godvin laid out how misguided the government’s response to her friend’s death was and how it failed to recognize the overlap between those who use drugs and those who sell them. “To purchase heroin, you have to know someone who has it, or know someone who knows someone who does. Friends and acquaintances formed our network. The vast majority of heroin dealers I met were not in it to make money. They simply supported their own habit by selling to people they knew who were also addicted. The archetypal predatory drug dealer is a myth. For many, a sale is not about ruthless profit; it is about survival.”

But as the overdose crisis has taken hundreds of thousands of lives in recent years, prosecutions like Godvin’s have become increasingly common. Several states have enacted laws akin to the laws under which she was prosecuted or have made their existing laws harsher.

This week, the Drug Policy Alliance delivered a comprehensive rebuttal to this policy response and the worldview that drives it. In a new report , the organization calls for an end to the broad demonization of and harsh penalties for people selling drugs. It is necessary, the report says, to “rethink the ‘drug dealer.’” The authors note: “Policymakers in the United States increasingly recognize that drug use should be treated as a public health instead of a criminal issue.” Yet, “the softening of public opinion has not extended to people involved in drug selling or distribution, as politicians on both sides of the aisle have made clear.”

The impulse to conceive of people who sell drugs as a category distinct from people who use them is both misguided and counterproductive, the report states. “Politicians and prosecutors who say they want a public health approach to drug use, but harsh criminal penalties for anyone who sells, are in many cases calling for the imprisonment and non-imprisonment of the very same people.”

In 2012, over 80 percent of those arrested for distribution offenses in Chicago tested positive for drug use. In New York and Sacramento it was over 90 percent. Moreover, the laws criminalizing drug sales are written so broadly that people arrested with drugs for their own use are frequently charged as dealers.

The narrative of the dangerous drug dealer also has a long history. It is “a deeply racialized narrative in which illegal drug use is driven by drug sellers (often portrayed as people of color) who push drugs on vulnerable people (often white people) to get them hooked.”

Writing for The Appeal this week, Zachary Siegel reviews the report’s prescribed reforms , which include the repeal of drug-induced homicide laws; calling on progressive prosecutors to decline to prosecute certain sale and distribution-related offenses; and radically reducing the number of arrests police treat as drug sale and distribution.

While advocating for a number of “incremental reforms,” the Drug Policy Alliance remains committed to fundamental changes to how drug use and drug markets are viewed. “As we consider new approaches for people who use, we also need to explore options for addressing drug sales outside the criminal justice system,” Lindsay LaSalle, managing director of public health law and policy at the Drug Policy Alliance told The Appeal . “We need a radical shift away from supply side interventions and must truly examine both the demand for drugs and the economic and structural reasons why people may be selling drugs.”

Ultimately, the distinctions between drug buyers and sellers draws on the same zero-sum instinct—the desire to sort people into opposing categories—as seen in conversations about victims versus offenders and people charged with nonviolent crimes versus those charged with violent crimes. In the discussions of reforms that help free people charged with nonviolent versus those charged with violent crimes, there is the constant risk of presenting one group as deserving at the expense of the other. In the conversations about victims and offenders there is a systemic unwillingness to recognize that many of those who commit harm have themselves been harmed. And for those who have suffered, it seems too often as though the state’s recognition of one’s humanity comes only in the form of the criminal legal system trying to find someone to blame and punish—however irrelevant an exercise that might be.

In her commentary, Godvin points out the lack of support available to her friend while he lived and the massive law enforcement resources mobilized in his name after he died. “Society offered no compassionate resources to Justin while he was alive—only a dozen arrests and a prison sentence, none of which helped him overcome addiction.” But “the federal government poured resources into convicting five people for his accidental overdose—me, my roommate who sold me my heroin, his dealer and that man’s two dealers—sentencing us to 60 total years in prison for Justin’s death.” That enormous amount of incarceration changed nothing. “The flow of heroin in our city, Portland, continued without a moment’s interruption. In the years after the trial, the rate of fatal heroin overdoses in Oregon even increased.”

Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Policy Jul 6, 2015

The economics of the illegal drug market, an argument for sentencing dealers based on the purity of their product..

Manolis Galenianos

Rosalie Liccardo Pacula

Nicola Persico

What does the illegal drug market look like to an economist?

This research recently won Kellogg’s Stanley Reiter Best Paper Award.

This is what the Kellogg School’s Nicola Persico set out to learn. A better understanding of the key features of the market for illicit drugs, he reasoned, could lead to more effective policies and enforcement practices.

Persico, a professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at the Kellogg School, developed a new model of the drug market that accounts for the fact that buyers do not know a drug’s purity before purchasing it, as well as the fact that they cannot contest sales of impure drugs.

The model provides a fuller picture of the drug market, and it includes some surprising implications. For one, police presence may actually increase buyer loyalty to specific sellers. And if policymakers choose to impose more lenient sentences on sellers of impure drugs, overall demand for drugs could decrease.

A Problem of Highest Priority

The United States’ war on drugs is tremendously costly —not only in terms of money spent, but also with regard to police manpower, legal proceedings, and long-term incarceration. “Illegal drugs arguably represent the number-one law enforcement issue in the U.S.,” Persico says, “so figuring out how to make progress in this area is very important.”

Persico’s previous work on racial profiling by police brought him to a criminology conference where drug scholar Peter Reuters discussed the issue of price dispersion in the illicit-drug market—that is, how drugs of the same type sold for very different prices in different places and at different times.

That observation got Persico thinking about the drug market in general: How did its structure differ from markets for legal products and services? Which economic models explained it best? And, importantly, what implications for policy and enforcement could be derived from a better understanding of the drug market?

Beyond Supply and Demand

Past efforts to characterize the drug market relied on standard supply-and-demand models. “It’s Econ 101,” Persico says. “The demand curve slopes down and the supply curve slopes up, and where they meet is the equilibrium point, or market-clearing price.” He acknowledges that this basic model has virtue, but wished to take a “Drug Market 2.0” approach, as he called it, to gain a better understanding of market structure and dynamics.

“If there’s a lot of police enforcement, buyers take more risk switching sellers because the next seller could be an undercover police officer.”

Part of that approach was the recognition that while illicit drugs share some economic qualities with agricultural commodities like coffee, drugs sell at a much higher price. And, more importantly, drug transactions are not enforceable through the legal system.

Persico and coauthors Manolis Galenianos of Royal Holloway College and Rosalie Liccardo Pacula of RAND Corporation used Drug Enforcement Administration information on drug transactions (heroin, cocaine, and others) in the U.S. from 1981 to 2003. The data the DEA supplied came from informants, undercover agents, and technicians, and included price, location, and purity of the drugs. An additional data set provided information on those arrested for buying and using drugs, and included demographics, number of dealers transacted with, difficulty locating dealers, and price paid.

Preliminary data analysis highlighted the unenforceability issue in a big way. “We saw the price dispersion, as expected, but also that about 5–10 percent of the transactions were completely fake ,” Persico said. “Those transactions—‘rip-offs’—involved no drug content at all, but buyers paid the same average amount for the product as they did for real drugs.” For example, 8.2 percent of all heroin transactions were rip-offs. “If someone sells me coffee that’s actually dirt, I can take them to court,” Persico says. “I can’t do that with heroin or cocaine.”

If you are buying an illegal drug, you only learn its purity after the sale is made. Why does that matter? “The inability to know the quality of drugs before purchase, combined with the unenforceability, means the drug market is always on the brink of collapse, as there will be incentive on the part of sellers not to make good on the product quality expected,” Persico says. Recognizing this “moral hazard” on the sellers’ part is critical for understanding the drug market—and addressing it more effectively.

Buy, Sell, Repeat

One question raised by Persico’s line of thinking was how the drug market could continue to exist in the first place—and even flourish—given the incentive for rip-offs. He believed there was a simple explanation: repeated interactions between the same buyers and sellers.

To explore this mechanism, the researchers turned to labor economics models pioneered by former Northwestern University economics professor and Nobel Prize winner Dale Mortensen —models originally developed to understand when and why workers switched from one employer to another. “The labor models assume that quality of the work—or the ‘product’—is consistent,” Persico says, “but that’s not a fair assumption in the drug market.” So the researchers adapted their model to account for the reality that a drug buyer will not be able to know the product quality when dealing with a seller for the first time.

When the researchers included the moral-hazard component in the models, they could see that having buyers who repeatedly patronize the same seller helps keep the market sustainable. In other words these frequent shoppers keep their dealers honest by discouraging rip-offs. For example, 76 percent of frequent heroin users reported buying drugs most recently from their regular dealer. “Where quality can’t be enforced by courts, the only thing that keeps it at a reasonable level is repeated interactions,” Persico says.

On this point, Persico speculates that greater police presence—including the undercover variety—actually makes repeated interactions more likely, thus increasing drug purity. “If there’s a lot of police enforcement, buyers take more risk switching sellers because the next seller could be an undercover police officer,” he says.

And that helps keep the drug market going.

Better Enforcement Means Lesser Enforcement

Out of Persico’s research emerges a logical but controversial enforcement recommendation: less harsh sentences for those selling less pure drugs.

Using tougher penalties for drug convictions has not reduced drug affordability; cocaine and heroin prices have fallen significantly, despite stronger enforcement. Less harsh sentencing for sellers of impure drugs will result, theoretically, in a higher proportion of rip-offs, because such sellers will spend less time in jail and face less deterrence than their pure-drug-selling counterparts. A higher rate of rip-offs would, the model shows, encourage more buyers to exit, leveraging the moral hazard to erode demand for illicit drugs.

Carrying this logic to the limit, Persico believes there should be zero penalty for a 100 percent-impure drug sale. “If someone’s selling sugar under the pretense of selling cocaine, let’s celebrate this guy!” he says. “The penalty should be for the actual amount of illicit substance sold, not the amount purportedly sold—let the punishment fit the actual crime.”

Persico’s enforcement suggestion potentially addresses an important social issue as well, given that those incarcerated for drug offenses tend to be from minority and low-income populations. “A more lenient sentencing policy would get people out of jail faster, save taxpayer money, and keep the percentage of rip-offs higher,” he says. “Who could be against that?”

Persico acknowledges the challenge of implementing his policy suggestion. “It’s not clear if the government would take our sentencing recommendation seriously,” he says.

Drug markets will continue to evolve. Some markets, like that for marijuana, have even moved from illicit to legal in some US states . The key takeaway from Persico’s research, then, is that to address any drug market and develop effective policies related to it, we first have to understand its dynamics and unique features.

That is a prescription well worth following.

John L. and Helen Kellogg Professor of Managerial Economics & Decision Sciences; Director of the Center for Mathematical Studies in Economics & Management; Professor of Weinberg Department of Economics (courtesy)

About the Writer Sachin Waikar is a freelance writer based in Evanston, Illinois.

Galenianos, Manolis, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, and Nicola Persico. 2012. “A Search-Theoretic Model of the Retail Market for Illicit Drugs.” Review of Economic Studies . 79(2): 1239–1269.

We’ll send you one email a week with content you actually want to read, curated by the Insight team.

Understanding the Demand for Illegal Drugs (2010)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

A merica’s problem with illegal drugs seems to be declining, and it is certainly less in the news than it was 20 years ago. Surveys have shown a decline in the number of users dependent on expensive drugs (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2001), an aging of the population in treatment (Trunzo and Henderson, 2007), and a decline in the violence related to drug markets (Pollack et al., 2010). Still, research indicates that illegal drugs remain a concern for the majority of Americans (Caulkins and Mennefee, 2009; Gallup Poll, 2009).

There is virtually no disagreement that the trafficking in and use of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine continue to cause great harm to the nation, particularly to vulnerable minority communities in the major cities. In contrast, there is disagreement about marijuana use, which remains a part of adolescent development for about half of the nation’s youth. The disagreement concerns the amount, source, and nature of the harms from marijuana. Some note, for example, that most of those who use marijuana use it only occasionally and neither incur nor cause harms and that marijuana dependence is a much less serious problem than dependence on alcohol or cocaine. Others emphasize the evidence of a potential for triggering psychosis (Arseneault et al., 2004) and the strengthening evidence for a gateway effect (i.e., an opening to the use of other drugs) (Fergusson et al., 2006). The uncertainty of the causal mechanism is reflected in the fact that the gateway studies cannot disentangle the effect of the drug itself from its status as an illegal good (Babor et al., 2010).

The federal government probably spends $20 billion per year on a wide array of interventions to try to reduce drug consumption in the United States, from crop eradication in Colombia to mass media prevention programs aimed at preteens and their parents. 1 State and local governments spend comparable amounts, mostly for law enforcement aimed at suppressing drug markets. 2 Yet the available evidence, reviewed in detail in this report, shows that drugs are just as cheap and available as they have ever been.

Though fewer young people are starting to use drugs than in some previous years, for each successive birth cohort that turns 21, approximately half have experimented with illegal drugs. The number of people who are dependent on cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine is probably declining modestly, 3 and drug-related violence has appears to have declined sharply. 4 At the same time, injecting drug use is still a major vector for HIV transmission, and drug markets blight parts of many U.S. cities.

The declines in drug use that have occurred in recent years are probably mostly the natural working out of old epidemics. Policy measures— whether they involve prevention, treatment, or enforcement—have met with little success at the population level (see Chapter 4 ). Moreover, research on prevention has produced little evidence of any targeted interventions that make a substantial difference in initiation to drugs when implemented on a large scale. For treatment programs, there is a large body of evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (reviewed in Babor et al., 2010), but the supply of treatment facilities is inadequate and,

perversely, not enough of those who need treatment are persuaded to seek it (see Chapter 4 ). Efforts to raise the price of drugs through interdiction and other enforcement programs have not had the intended effects: the prices of cocaine and heroin have declined for more than 25 years, with only occasional upward blips that rarely last more than 9 months (Walsh, 2009).

STUDY PROJECT AND GOALS

Given the persistence of drug demand in the face of lengthy and expensive efforts to control the markets, the National Institute of Justice asked the National Research Council (NRC) to undertake a study of current research on the demand for drugs in order to help better focus national efforts to reduce that demand. In response to that request, the NRC formed the Committee on Understanding and Controlling the Demand for Illegal Drugs. The committee convened a workshop of leading researchers in October 2007 and held two follow-up meetings to prepare this report. The statement of task for this project is as follows:

An ad hoc committee will conduct a workshop-based study that will identify and describe what is known about the nature and scope of markets for illegal drugs and the characteristics of drug users. The study will include exploration of research issues associated with drug demand and what is needed to learn more about what drives demand in the United States. The committee will specifically address the following issues:

What is known about the nature and scope of illegal drug markets and differences in various markets for popular drugs?

What is known about the characteristics of consumers in different markets and why the market remains robust despite the risks associated with buying and selling?

What issues can be identified for future research? Possibilities include the respective roles of dependence, heavy use, and recreational use in fueling the market; responses that could be developed to address different types of users; the dynamics associated with the apparent failure of policy interventions to delay or inhibit the onset of illegal drug use for a large proportion of the population; and the effects of enforcement on demand reduction.

Drawing on commissioned papers and presentations and discussions at a public workshop that it will plan and hold, the committee will prepare a report on the nature and operations of the illegal drug market in the United States and the research issues identified as having potential for informing policies to reduce the demand for illegal drugs.

The committee drew on economic models and their supporting data, as well as other research, as one part of the evidentiary base for this

report. However, the context for and content of this report were informed as well by the general discussion and the presentations in the workshop. The committee was not able to fully address task 2 because research in that area is not strong enough to give an accurate description of consumers across different markets nor to address the questions about why markets remain robust despite the risks associated with buying and selling. The discussion at the workshop underscored the point that neither the available ethnographic research nor the limited longitudinal research on drug-seeking behavior is strong enough to inform these questions related to task 2. With regard to task 3, the committee benefitted considerably from the paper by Jody Sindelar that was presented at the workshop and its discussion by workshop participants.

This study was intended to complement Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting Us (National Research Council, 2001) by giving more attention to the sources of demand and assessing the potential of demand-side interventions to make a substantial difference to the nation’s drug problems. This report therefore refers to supply-side considerations only to the extent necessary to understand demand.

The charge to the committee was extremely broad. It could have included reviewing the literature on such topics as characteristics of substance users, etiology of initiation of use, etiology of dependence, drug use prevention programs, and drug treatments. Two considerations led to narrowing the focus of our work. The first was substantive. Each of the topics just noted involves a very large field of well-developed research, and each has been reviewed elsewhere. Moreover, each of these areas of inquiry is currently expanding as a result of new research initiatives 5 and new technologies (e.g., neuroimaging, genetics). The second consideration was practical: given the available resources, we could not undertake a complete review of the entire field.

Thus, we decided to focus our work and this report tightly on demand models in the field of economics and to evaluate the data needs for advancing this relatively undeveloped area of investigation. That is, this area has a relatively shorter history of accumulated findings than the more clinical, biological, and epidemiological areas of drug research. Yet it is arguably better situated to inform government policy at the national level. A report on economic models and supporting data seemed to us more timely than a report on drug consumers and drug interventions.

The rest of this chapter briefly lays out some concepts that provide a basis for understanding the committee’s work and the rest of the report.

Chapter 2 presents the economic framework that seems most useful for studying the phenomenon of drug demand. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the responsiveness of demand and supply to price, which is the intermediate variable targeted by the principal government programs in the United States, namely, drug law enforcement. Chapter 3 then examines changes in the consumption of drugs and assesses the various indicators that are available to measure that consumption. Chapter 4 turns to the program type that most focuses specifically on reducing drug demand, the treatment of dependent users. It considers how well these programs work and how the treatment system might be expanded to further reduce consumption. Finally, Chapter 5 presents our recommendations for how the data and research base might be built to improve understanding of the demand for drugs and policies to reduce it.

PROGRAM CONCEPTS

A standard approach to considering drug policy is to divide programs into supply side and demand side. This approach accepts that drugs, as commodities, albeit illegal ones, are sold in markets. Supply-side programs aim to reduce drug consumption by making it more expensive to purchase drugs through increasing costs to producers and distributors. Demand-side programs try to lower consumption by reducing the number of people who, at a given price, seek to buy drugs; the amount that the average user wishes to consume; or the nonmonetary costs of obtaining the drugs. This approach has value, but it also raises questions.

The value of this framework is that it allows systematic evaluation of programs. A successful supply-side program will raise the price of drugs, as well as reduce the quantity available, while a demand-side program will lower both the number of users and the quantity consumed, as well as eventually reducing the price. As noted above, this report is primarily focused on improving understanding of the sources of demand.

There are two basic objections to this approach. First, some programs have both demand- and supply-side effects. Since many dealers are themselves heavy users, drug treatment will reduce supply, just as incarceration of drug dealers lowers demand. Second, there is a collection of programs that do not attempt to reduce demand or supply; rather, their goal is to reduce the damage that drug use and drug markets cause society, which are generally referred to as “harm-reduction” programs (Iversen, 2005; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010). 6 Nonetheless, the classifi-

cation of interventions into demand reduction and supply reduction is a very helpful heuristic for policy purposes, as well as being written into the legislation under which the Office of National Drug Control Policy operates.

What determines the demand for drugs? Clearly, many different factors play a role: cultural, economic, and social influences are all important. At the individual level, a rich set of correlates have been explored, either in large-scale cross-sectional surveys (such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse) or in small-scale longitudinal studies (see, e.g., Wills et al., 2005). Below we briefly summarize the complex findings of those studies.

Less has been done at the population level. It is known that rich western countries differ substantially in the extent of drug use, in ways that do not seem to reflect policy differences. For example, despite the relatively easy access to marijuana in the Netherlands, that nation has a prevalence rate that is in the middle of the pack for Europe, while Britain, despite what may be characterized as a pragmatic and relatively evidence-oriented drug policy, has Europe’s highest rates of cocaine and heroin addiction (European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2007). There is only minimal empirical research that has attempted to explain those differences. Similarly, there is very little known about why epidemics of drug use occur at specific times. In the United States, for example, there is no known reason for the sudden spread of methamphetamine from its long-term West Coast concentration to the Midwest that began in the early 1990s. There are only the most speculative conjectures as to the proximate causes.

A DYNAMIC AND HETEROGENEOUS PROCESS

The committee’s starting point is that drug use is a dynamic phenomenon, both at the individual and community levels. In the United States there is a well-established progression of use of substances for individuals, starting with alcohol or cigarettes (or both) and proceeding through marijuana (at least until recently) possibly to more dangerous and expensive drugs (see, e.g., Golub and Johnson, 2001). Such a progression seems to be a common feature of drug use, although the exact sequence might not apply in other countries and may change over time. For example, cigarettes may lose their status as a gateway drug because of new restrictions on their use. 7 Recently, abuse of prescription drugs has emerged as a possible gateway, with high prevalence rates reported for youth aged 18-25;

however, because of limited economic research on this phenomenon, this report’s focus is on completely illegal drugs.

At the population level, there are epidemics, in which, like a fashion good, a new drug becomes popular rapidly in part because of its novelty and then, often just as rapidly, loses its appeal to those who have not tried it. For addictive substances (including marijuana but not hallucinogens, such as LSD), that leaves behind a cohort of users who experimented with the drug and then became habituated to it.

An important and underappreciated element of the demand for illegal drugs is its variation in many dimensions. For example, the demand for marijuana may be much more responsive to price changes than the demand for heroin because fewer of those who use marijuana are drug dependent (Iversen, 2005; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2010). Users who are employed, married, and not poor may be more likely to desist than users of the same drug who are unemployed, not part of an intact household, and poor. There may be differences in the characteristics of demand associated with when the specific drug first became available in a particular community, that is, whether it is early or late in a national drug “epidemic.”

There are also unexplained long-term differences in the drug patterns in cities that are close to each other. In Washington, DC, in 1987 half of all those arrested for a criminal offense (not just for drugs) tested positive for phencyclidine, while in Baltimore, 35 miles away, the drug was almost unknown. Although the Washington rate had fallen to approximately 10 percent in 2009 (District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency, 2009), it remains far higher than in other cities. More recently, the spread of methamphetamine has shown the same unevenness: in San Antonio only 2.3 percent of arrestees tested positive for methamphetamine in 2002; in Phoenix, the figure was 31.2 percent (National Institute of Justice, 2003). These differences had existed for more than 10 years.

The implication of this heterogeneity is that programs that work for a particular drug, user type, place, or period may be much less effective under other circumstances, which substantially complicates any research task. It is hard to know how general are findings on, say, the effectiveness of a prevention program aimed at methamphetamine use by adolescents in a city where the drug has no history. Will this program also be effective for trying to prevent cocaine use among young adults in cities that have long histories of that drug?

This report does not claim to provide the answers to such ambitious questions. It does intend, however, to equip policy officials and the public to understand what is known and what needs to be done to provide a more sound base for answering them.

Arseneault, L., M. Cannon, J. Witten, and R. Murray. (2004). Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: Examination of the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184 , 110-117.

Babor, T., J. Caulkins, G. Edwards, D. Foxcroft, K. Humphreys, M.M. Mora, I. Obot, J. Rehm, P. Reuter, R. Room, I. Rossow, and J. Strang. (2010). Drug Policy and the Public Good . New York: Oxford University Press.

Carnevale, J. (2009). Restoring the Integrity of the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Testimony at the hearing on the Office of National Drug Control Policy’s Fiscal Year 2010 National Drug Control Budget and the Policy Priorities of the Office of National Drug Control Policy Under the New Administration. The Domestic Policy Subcommittee of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. May 19, 2009. Available: http://carnevaleassociates.com/Testimony%20of%20John%20Carnevale%20May%2019%20-%20FINAL.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Caulkins, J., and R. Mennefee. (2009). Is objective risk all that matters when it comes to drugs? Journal of Drug Policy Analysis , 2 (1), Art. 1. Available: http://www.bepress.com/jdpa/vol2/iss1/art1/ [accessed August 2010].

District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency. (2009). PSA’s Electronic Reading Room—FOIA. Available: http://www.dcpsa.gov/foia/foiaERRpsa.htm [accessed May 2009].

European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2007). 2007 Annual Report: The State of the Drug Problem in Europe. Lisbon, Portugal. Available: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/annual-report/2007 [accessed May 2009].

Fergusson, D.M., J.M. Boden, and L.J. Horwood. (2006). Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: Testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction, 6 (101), 556-569.

Gallup Poll. (2009). Illegal Drugs . Available: http://www.gallup.com/poll/1657/illegal-drugs.aspx [accessed April 2010].

Golub, A., and B. Johnson. (2001). Variation in youthful risks of progression from alcohol and tobacco to marijuana and to hard drugs across generations. American Journal of Public Health, 91 (2), 225-232.

Iversen, L. (2005). Long-term effects of exposure to cannabis. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 5 (1), 69-72. Available: http://www.safeaccessnow.org/downloads/long%20term%20cannabis%20effects.pdf [accessed July 2010].

National Institute of Justice. (2003). Preliminary Data on Drug Use & Related Matters Among Adult Arrestees & Juvenile Detainees 2002 . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2010). NIDA InfoFacts: Heroin . Available: http://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/heroin.html [accessed August 2010].

National Research Council. (2001). Informing America’s Policy on Illegal Drugs: What We Don’t Know Keeps Hurting Us. Committee on Data and Research for Policy on Illegal Drugs, C.F. Manski, J.V. Pepper, and C.V. Petrie (Eds.). Committee on Law and Justice and Committee on National Statistics. Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (1993). State and Local Spending on Drug Control Activities . NCJ publication no. 146138. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2001). What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs 1988–2000 . W. Rhodes, M. Layne, A.-M. Bruen, P. Johnston, and L. Bechetti. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President.

Pollack, H., P. Reuter., and P. Sevigny. (2010). If Drug Treatment Works So Well, Why Are So Many Drug Users in Prison? Paper presented at the meeting of the National Bureau of Economic Research on Making Crime Control Pay: Cost-Effective Alternatives to Incarceration, July, Berkeley, CA. Available: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12098.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Trunzo, D., and L. Henderson. (2007). Older Adult Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment: Findings from the Treatment Episode Data Set . Paper presented at the meeting of the American Public Health Association, November 6, Washington, DC. Available: http://apha.confex.com/apha/135am/techprogram/paper_160959.htm [accessed August 2010].

Walsh, J. (2009). Lowering Expectations: Supply Control and the Resilient Cocaine Market. Available: http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/graficos/pdf09/wolareportcocaine.pdf [accessed August 2010].

Wills, T., C. Walker, and J. Resko. (2005). Longitudinal studies of drug use and abuse. In Z. Slobada (Ed.), Epidemiology of Drug Abuse (pp. 177-192). New York: Springer.

This page intentionally left blank.

Despite efforts to reduce drug consumption in the United States over the past 35 years, drugs are just as cheap and available as they have ever been. Cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines continue to cause great harm in the country, particularly in minority communities in the major cities. Marijuana use remains a part of adolescent development for about half of the country's young people, although there is controversy about the extent of its harm.

Given the persistence of drug demand in the face of lengthy and expensive efforts to control the markets, the National Institute of Justice asked the National Research Council to undertake a study of current research on the demand for drugs in order to help better focus national efforts to reduce that demand.

This study complements the 2003 book, Informing America's Policy on Illegal Drugs by giving more attention to the sources of demand and assessing the potential of demand-side interventions to make a substantial difference to the nation's drug problems. Understanding the Demand for Illegal Drugs therefore focuses tightly on demand models in the field of economics and evaluates the data needs for advancing this relatively undeveloped area of investigation.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Dark web, not dark alley: why drug sellers see the internet as a lucrative safe haven

Associate Professor in Criminology, Swinburne University of Technology

Vice Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellow, Social and Global Studies Centre, RMIT University

Disclosure statement

James Martin receives funding from the Australian Institute of Criminology, who funded this particular study, as well as the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Monica Barratt receives funding from Australian (National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Institute of Criminology, the National Centre for Clinical Research into Emerging Drugs) and international (US National Institutes of Health, NZ Marsden Fund) funders. She has recently conducted commissioned research for the NSW Coroner's Office, the WA Mental Health Commission and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. Monica also volunteers for not-for-profit harm reduction organisations: The Loop Australia and Bluelight.org

RMIT University provides funding as a strategic partner of The Conversation AU.

Swinburne University of Technology provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

More than six years after the demise of Silk Road, the world’s first major drug cryptomarket , the dark web is still home to a thriving trade in illicit drugs.

These markets host hundreds, or in some cases thousands, of people who sell drugs, commonly referred to as “vendors”. The dark web offers vital anonymity for vendors and buyers, who use cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin to process transactions.

Trade is booming despite disruptions from law enforcement and particularly “exit scams”, in which market admins abruptly close down sites and take all available funds.

Read more: Explainer: what are drug cryptomarkets?

Why are these markets still seen as enticing places to sell drugs, despite the risks? To find out, our recent study surveyed 13 darknet drug vendors, via online encrypted interviews.

They gave us a range of reasons.

More profitable

First, selling drugs online is safer and more profitable than doing it offline:

Interviewer: So you still sell on DNMs [darknet marketplaces], and prefer that to offline. Correct? Respondent: YES. Selling offline is borderline stupid. You can make so much more money online, the risks [in selling outside cryptomarkets] aren’t even remotely worth it.

Both of these claims correspond with previous research showing that the dark web is perceived to be a safer place to buy and sell drugs.

Regarding profits, darknet vendors do not have to limit their trading to face-to-face interactions, and can instead sell drugs to a potentially worldwide customer base.

Read more: Explainer: what is the dark web?

Less violent

Encryption technologies allow vendors to communicate with customers and receive payments anonymously. The drugs are delivered in the post, so vendor and customer never have to meet in person.

This protects vendors from many risks that are prevalent in other forms of drug supply, including undercover police, predatory standover tactics where suppliers may be robbed, assaulted or even killed by competitors, and customers who may inform on their supplier if caught.

Other risks, such as frauds perpetrated by customers and exit scams, were considered inevitable on the dark web, but also manageable.

Some respondents said that being protected from physical risk on the dark web is not only a benefit for existing drug suppliers, but may also make the activity attractive to people who would not otherwise be willing to sell drugs.

While some of our respondents had previously sold drugs offline, others were uniquely attracted to the perceived safety and anonymity of the dark web:

I hadn’t ever thought about selling drugs in any capacity because I dislike violence and it just seemed impossible to be involved in selling drugs in “real life” without running into some sort of confrontation pretty quickly… I was always too scared and slightly nerdy to do that and never really contemplated it seriously until the dark web.

More customer-focused

Some vendors told us the feeling of safety and control lets them focus on providing a more courteous service to their customers or “clients”:

I try to provide the best products and service I can, when someone has a problem or claims [their order was] short on pills (as long as they have ordered from me before) I usually take them at their word.

This is a stark contrast with perceptions of the street trade, which some of our respondents perceived not only as “small-time”, but also rife with danger and potential violence:

The street trade is a mess. I wanna provide labelled products, good advice and service, like a real business. Not sit in a shitty car park selling $10 bags from a car window all day.

Read more: Australia emerges as a leader in the global darknet drugs trade

Not just about profit

Dark web vendors also pointed out the various non-material benefits of their work. These included feelings of autonomy and emancipation from boring work and onerous bosses, as well as excitement and the thrill of transgression. One respondent described it as:

Exhilarating … and nerve-wracking. Seemed so alien. “Drugs? Online? In the post? Naaaah surely not.” Plus if I’m honest, my inner reprobate buzzes from it. The rush of chucking a grand’s worth of drugs into post boxes… unreal, man.

Interviewees rationalised their participation in the dark web drugs trade in a variety of ways. These included pointing out the relative safety and medicinal benefits of some illicit drugs, and the dangers associated with drug prohibition .

Let’s face it, a LOT of people like getting high… It’s human nature, but to ban it and make it criminal so that it’s hard to get, then you get poison and people die… I can tell you that the use of darknet protects users from buying products that during traditional prohibition would likely kill much more people. It also takes drugs off the street, reducing some violent crime.

These insights help us understand why the dark web is increasingly attractive, not only to consumers of illicit drugs but to the people who supply them.

For those who are averse to confrontation, and who are sufficiently tech-savvy, the dark web offers an alternative to the risk and violence of dealing drugs offline.

- Illicit drugs

- Cryptocurrency

- Drug dealing

- Black markets

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges

Investigator, Student Academic Misconduct (Multiple Positions Available)

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Peer Pressure — Drugs: Causes and Effects

Drugs: Causes and Effects

- Categories: Mental Health Peer Pressure

About this sample

Words: 1209 |

Published: Mar 25, 2024

Words: 1209 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 725 words

3 pages / 1279 words

2 pages / 1090 words

4 pages / 2004 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Peer Pressure

Depression and anxiety are often called "invisible illnesses," and they affect a lot of college students these days. These mental health problems can really mess with students' grades, social lives, and overall happiness. In [...]

Social pressure is a powerful force that can shape individuals' thoughts, behaviors, and decisions. It refers to the influence that society, peers, and other groups have on an individual's actions and beliefs. This pressure can [...]

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century revolutionized the way information was disseminated and had a profound impact on society, culture, and the spread of knowledge. This essay will [...]

Arterial pressure, or blood pressure as most call it, is super important for our health. It's basically how hard your blood pushes against your artery walls when your heart pumps. If your blood pressure's off, it can signal [...]

The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a movie based on the novel written by Stephen Chbosky. It features a socially awkward boy named Charlie trying his best to fit in at high school, after a traumatic childhood. Perks is a [...]

By definition, peer pressure is social pressure by members of one's peer group to take a certain action, adopt certain values, or otherwise conform to be accepted. Everyone, during a period of their life, experiences peer [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2020

Practices of care among people who buy, use, and sell drugs in community settings

- Gillian Kolla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5743-7153 1 &

- Carol Strike 1

Harm Reduction Journal volume 17 , Article number: 27 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

40 Citations

69 Altmetric

Metrics details

Popular perception of people who sell drugs is negative, with drug selling framed as predatory and morally reprehensible. In contrast, people who use drugs (PWUD) often describe positive perceptions of the people who sell them drugs. The “Satellite Sites” program in Toronto, Canada, provides harm reduction services in the community spaces where people gather to buy, use, and sell drugs. This program hires PWUD—who may move into and out of drug selling—as harm reduction workers. In this paper, we examine the integration of people who sell drugs directly into harm reduction service provision, and their practices of care with other PWUD in their community.

Data collection included participant observation within the Satellite Sites over a 7-month period in 2016–2017, complemented by 20 semi-structured interviews with Satellite Site workers, clients, and program supervisors. Thematic analysis was used to examine practices of care emerging from the activities of Satellite Site workers, including those circulating around drug selling and sharing behaviors.

Satellite Site workers engage in a variety of practices of care with PWUD accessing their sites. Distribution of harm reduction equipment is more easily visible as a practice of care because it conforms to normative framings of care. Criminalization, coupled with negative framings of drug selling as predatory, contributes to the difficultly in examining acts of mutual aid and care that surround drug selling as practices of care. By taking seriously the importance for PWUD of procuring good quality drugs, a wider variety of practices of care are made visible. These additional practices of care include assistance in buying drugs, information on drug potency, and refusal to sell drugs that are perceived to be too strong.

Our results suggest a potential for harm reduction programs to incorporate some people who sell drugs into programming. Taking practices of care seriously may remove some barriers to integration of people who sell drugs into harm reduction programming, and assist in the development of more pertinent interventions that understand the key role of drug buying and selling within the lives of PWUD.

Research examining drug selling (frequently referred to as “drug dealing”) has found that it is a common income generation strategy among people who inject drugs, particularly among people who report daily drug use [ 1 , 2 ]. In fact, the category of “drug seller” or “drug dealer” itself is somewhat fluid, with many people who use drugs (PWUD) moving into or out of low-level drug selling depending on circumstance and economic necessity [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. When examining the relationship between PWUD and people who sell drugs, PWUD often describe high levels of trust when buying from their “regular” drug seller [ 6 , 7 ], and consider a long and trusted relationship with the person selling them drugs as a source of protection against overdose [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. PWUD frequently cite buying from a trusted or known drug seller as a harm reduction strategy that they engage in [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]; despite this, harm reduction programming and research has been slow to engage with people who sell drugs directly.

With few exceptions, harm reduction programs have focused on their clients as consumers of drugs, and little attention has been paid to the ways in which people who engage in drug selling—often the very same people—could be integrated into harm reduction efforts. In the context of the North American overdose crisis, multiple interventions have been scaled up including overdose education and naloxone distribution programs, overdose prevention and supervised consumption sites, and drug checking programs [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. While there has been some interest in how people who sell drugs might be integrated into drug checking interventions as part of the response to the overdose crisis [ 6 ], the integration of people who sell drugs into other areas of harm reduction programming remains underexplored, and may hold promise as a way to address continuing high overdose death rates.

In this paper, we present and analyze qualitative data from interviews and ethnographic observations of the Satellite Site program—a low-threshold, peer-led harm reduction program operating within community spaces—frequently apartments—where people gather to buy, use, and sell drugs. The Satellite Site program hires PWUD to be Satellite Site workers (SSW), who are chosen because they are well-known in their communities, and want to work as a type of community-based harm reduction worker. To do so, they are trained to offer harm reduction services to other PWUD in their social networks, and work primarily from their own homes. The Satellite Sites become community access points for harm reduction equipment and information, overdose education, and naloxone distribution, and, in some sites, monitoring of drug consumption [ 16 , 17 ]. One of the unique elements of the Satellite Site program is that it works directly with people who may move into and out of drug selling; the result is that some of the SSWs are people who sell, or allow drugs to be sold within their sites. The Satellite Site program is an example of a safer environment intervention [ 18 , 19 ], where people who use and sometimes sell drugs are employed to deliver harm reduction equipment and education to their peers. The program aims to improve the health of PWUD by altering the socio-spatial relations within these closed spaces in the community where people gather to use drugs. In this paper, we focus on the practices of mutual aid and support—or practices of care—that were observed within the Satellite Sites. These practices of care circulate in the harm reduction work that occurs between SSWs and their clients, and were also observed during instances of drug selling and sharing. The existence of practices of care surrounding drug selling troubles popular conceptions of drug selling as always or solely predatory or deviant [ 20 , 21 , 22 ], and offers insights into how people who sell drugs might be integrated into harm reduction programs more broadly.

Drug selling and harm reduction

Focusing on drug selling within harm reduction programming is not a new idea. A key early example of this is provided by Grove [ 23 ], who argued that “real harm reduction” must focus on the key concerns of PWUD, which frequently revolve around availability of drugs, how to find enough money to buy good-quality drugs, and how to avoid detection by the police. “Real harm reduction” focuses on the harms caused to PWUD by drug prohibition, particularly the harms stemming from an unregulated drug market with no quality control or method of verifying the potency and composition of drugs, and where the risk of arrest and incarceration is ever present. These are major problems for PWUD, and Grove critiqued early public health interventions for completely ignoring them while also attempting to justify harm reduction by focusing solely on its ability to prevent HIV transmission among PWUD [ 23 ]. Highlighting that “drug use is profoundly normal”, Grove traces how prohibition and criminalization not only fail to dissuade drug use, but are also social policies that accentuate the harms associated with drug use [ 23 ]. He also highlights the drug user organizing that led to “shooting galleries” being early spaces of harm reduction, where PWUD are able to use drugs off the street and where they do not have to hurry to attempt to avoid law enforcement [ 23 ].

While many key components of public health interventions for PWUD (such as needle and syringe distribution programs) started out as survival strategies among PWUD, their uptake and operationalization by public health authorities (who may have little to no connection with communities of PWUD) can lead to services that are not accommodating nor reflective of the needs of people who use drug [ 24 ]. A prime example of this is the way in which public health interventions have almost completely ignored drug buying and selling except to prohibit it within formal programs and service offerings. Due to criminalization, drug selling represents a particularly contentious issue to be managed for organizations providing services to PWUD, necessitating an institutional focus on rules and regulations. This includes rules that prohibit the sharing or selling of drugs, or—within the context of supervised consumption services—that specify particular methods of drug administration and whether people can receive assistance with injections [ 25 , 26 ]. This focus on the enforcement of rules and regulations can alienate and exclude PWUD from accessing much-needed harm reduction services [ 25 , 27 , 28 ]. Unsanctioned and peer-run services that are designed to be “low-threshold” and function with fewer rules (or with behavioral guidelines that emerge organically from communities of PWUD) may attract more marginalized service users who would otherwise choose not to access or be excluded from accessing services [ 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 ].

The difficulties in ensuring that the institutional rules and regulations that surround the delivery of harm reduction services are low threshold and reflect the local culture among PWUD are amplified in any attempt to work with people who sell drugs, despite the frequent acknowledgment that engaging in low-level drug selling is common for people with high frequency or daily drug use [ 1 , 2 ]. Alternate framings of drug selling remain rare. Research has documented how PWUD frequently engage in “helping” and mutual aid behaviors—such as procuring and sharing drugs with each other—that are technically drug distribution or trafficking offences under drug laws [ 31 , 32 ]. Previous research has also documented how the mutual aid that emerges from social ties between PWUD can be protective in cases where people cannot secure an adequate supply of drugs for themselves, and must rely on other PWUD to supply them with opioids as they attempt to avoid opioid withdrawal [ 33 , 34 ]. Programs that formally and explicitly engage with people who sell, share, or exchange drugs (activities that are frequently and often interchangeably referred to as “drug dealing”) in pursuit of harm reduction or public health goals are rarely documented. Framings of people who sell or supply drugs as predatory and morally reprehensible remain popular and enduring [ 20 , 35 ]. This renders it difficult to explore the practices of mutual aid and support—or practices of care—that surround drug selling and sharing in communities of PWUD.

Practices of care in harm reduction

This paper explores the practices of care that SSWs engage in as part of their harm reduction work, with a focus on the practices of care that circulate around drug selling. Drawing on Foucault’s ethics as well as more recent work on pleasure in drug use [ 36 ], Duff examines how “drug users cultivate and sustain practices of care in contexts of social and economic disadvantage” [ 37 ], (p83). Here, “practices of care” refers both to the practices used by PWUD to care for the self within larger social and economic contexts that remain hostile to drug use, as well as the ways in which people care for others, emphasizing the often relational character of practices of care [ 37 ]. Research on the practices of care surrounding drug use has emerged from a concern that the experience of pleasure has been neglected in research on illicit drug use [ 38 , 39 ]. Instead, a focus on the risks and harms associated with drug use has reinforced the “pathologizing tendencies” of research on drug use, with drug policy and programming reflecting this view of drug use as almost exclusively harmful [ 36 , 40 ]. In contrast, “thinking with” pleasure in drug use may provide a way to counter this tendency towards pathologization, allowing for examinations of the pragmatic ways people use drugs to manage illness or pain, and to experience pleasurable sensations and states of consciousness, in addition to the oft-documented negative effects of drug use [ 38 , 41 ]. Nuancing drug use in this way may hold potential to counter stigma and moral judgment against PWUD, and open space to explore how practices of care circulate among PWUD [ 37 ].

Much of the concern with care stems from the work of feminist scholars in science and technology studies, and stems from the feminist concern with devalued labor [ 42 ]. Here, the concept of “care” carries multiple and often interwoven meanings, including care as indicative of paying attention to something in a careful or watchful manner, “caring about” as a state of being emotionally attached to something, and “caring for” as a way of providing for or looking after someone as part of a social relationship [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. We focus on “practices of care” to reflect care as an active practice, a moment of active “doing” of care that engages practitioners in their worlds [ 42 , 43 ]. However, it is also important to note that care is a contested concept, and that practices of care are not neutral or uniformly positive acts of affection or attachment [ 46 ]. Instead, the concept of care is constrained by uneven and asymmetrical power relations that dictate which practices of care are worthy of attention and to “count” as care [ 46 ]. Practices of care are often embroiled in a complex politics that determines which practices, people, and phenomena are recognized as caring or worthy of care and which are excluded from recognition or analysis [ 43 ]. Acknowledging this contested “politics of care” highlights how attention to care is selective, where some lives and phenomena are included and attended to, while others are neglected and excluded from consideration or analysis—particularly those marginalized by drug use and related social inequities [ 43 , 47 ]. Focusing on “real harm reduction” [ 23 ] by listening to the expressed needs of PWUD around the centrality of drug buying in their lives, and developing interventions that take seriously the practices of care among people who sell drugs, provides recognition of the practices of care among a marginalized group of people that are frequently ignored.

Practices of care in harm reduction proliferate, yet have only recently begun to be described as such. Examining the practices of care among PWUD builds off research that has repeatedly documented the mutual aid among PWUD. This includes the ways that PWUD (whether formally employed as “peer workers” or not) support others within harm reduction programs and overdose prevention sites, with more recent research exploring their experiences reversing overdoses in housing and community settings [ 17 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. Practices of care range from the provision of sterile injection equipment to the administration of naloxone to reverse a life-threatening opioid overdose. For example, Fraser describes the “ethos of community care” that inspires people to maintain large supplies of sterile injection equipment on hand so that they can engage in secondary distribution of this equipment—a practice of care—to people in need [ 52 ]. Similarly, the way in which the expansion of take-home naloxone programs has allowed new practices of care to develop between a person administering naloxone and a person who is overdosing, has been explored to describe how people will use naloxone to gently reverse overdose, in an attempt to avoid the harms of precipitated withdrawal from more forceful naloxone administration [ 47 ].

Increased attention is being paid to how a strong focus on risk and harm in research on drug use may obscure the wide variety of drug use experiences [ 37 , 38 , 40 ]. However, such nuance is lacking when examining drug selling. People who sell drugs are routinely framed not only as uncaring, but as actively predatory towards others [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Many studies of drug selling and drug markets focus on the aggression, theft, and violence that can occur around drug selling and buying within unregulated drug markets [ 3 , 53 , 54 ]. Without ignoring the existence of these important issues, we attempt to broaden the discussion of what constitutes “care” within harm reduction practice by exploring the variety of practices of care that people are engaging in related to drug selling and drug sharing. Starting with Grove’s insight that “real harm reduction” must attend to the primacy of drug buying and selling in the lives of PWUD [ 23 ], in this paper we explore the practices of care that surround drug procurement, buying, and selling. Exploring the practices of care that exist among people who use and sell drugs opens the possibility for a reconceptualization of some aspects of drug selling more generally, and for imagining a place for the broader participation of people who sell drugs in harm reduction programs specifically.

This research was conducted with the “Satellite Site” program, implemented in Toronto, Canada. The Satellite Site program started informally in 1999, as an outgrowth of a peer-developed and peer-run harm reduction program operating inside a community health center. The founder of the program, who ran the harm reduction program at the community health center and who openly identified as a person who injected drugs, began to provide home delivery of sterile injection equipment to increase access for community members outside the hours of operation at the community health center. Noticing that many people maintained communal spaces where people gathered to use illicit drugs, he began asking the people running these spaces if they wanted to keep extra harm reduction supplies around for others who might need them; this was the beginning of the Satellite Site program [ 16 ]. The Satellite Sites were based on a secondary syringe exchange model, where PWUD would distribute sterile injection equipment obtained from formal harm reduction programs to other people who inject drugs out in the community [ 55 , 56 , 57 ]. Since he was familiar with the sites and had spent time observing their operation firsthand, the program founder was able to choose Satellite Sites deliberately, and was able to assess potential Satellite Site workers for their suitability and privilege choosing spaces that were already engaged in high-volume needle and syringe distribution and disposal. Due to his close connections with the community, the program founder was also able to verify that the people running the sites were interested in working within a harm reduction philosophy and were not formally associated with any criminal organizations. He also ensured that SSWs were well-connected to the community health center so that they could provide referrals to the center for healthcare and social service needs. In 2010, the Satellite Site program adopted a more formal model when the program received external funding [ 16 ]. This allowed for the SSWs—who were previously in a volunteer role—to be employed as paid staff, receiving a modest salary of $250 a month and cellular telephone. During the study period, there were 9 Satellite Sites in operation, and each distributed and disposed of, on average, approximately 1500 needles and syringes a month.

Data collection