- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

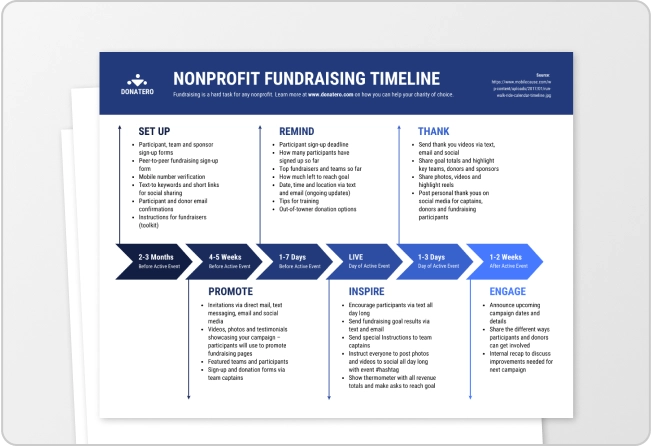

6. Timeline:

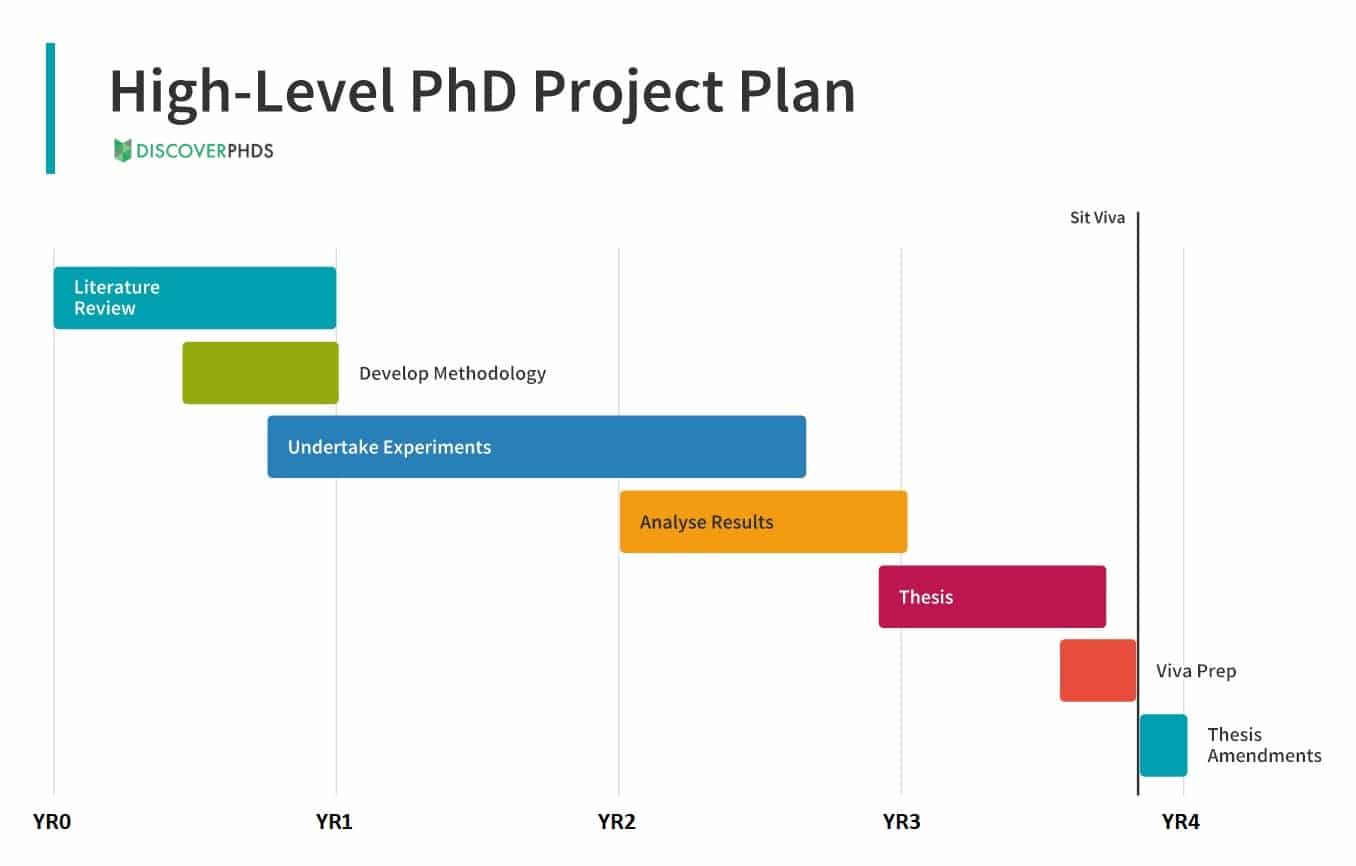

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .

Finally, the book Getting What You Came For (1992) by Robert Peters is not only an outstanding guide for anyone contemplating graduate school – from the application process onward – but it also includes several excellent chapters on planning and executing research, applicable across a wide variety of subject areas. It was an invaluable resource for me 25 years ago, and it remains in print with good reason; I recommend it to all my students, particularly Chapter 16 (‘The Thesis Topic: Finding It’), Chapter 17 (‘The Thesis Proposal’) and Chapter 18 (‘The Thesis: Writing It’).

Goals and motivation

How to do mental time travel

Feeling overwhelmed by the present moment? Find a connection to the longer view and a wiser perspective on what matters

by Richard Fisher

How to cope with climate anxiety

It’s normal to feel troubled by the climate crisis. These practices can help keep your response manageable and constructive

by Lucia Tecuta

Emerging therapies

How to use cooking as a form of therapy

No matter your culinary skills, spend some reflective time in the kitchen to nourish and renew your sense of self

by Charlotte Hastings

How to Write a PhD Research Proposal

- Applying to a PhD

- A research proposal summarises your intended research.

- Your research proposal is used to confirm you understand the topic, and that the university has the expertise to support your study.

- The length of a research proposal varies. It is usually specified by either the programme requirements or the supervisor upon request. 1500 to 3500 words is common.

- The typical research proposal structure consists of: Title, Abstract, Background and Rationale, Research Aims and Objectives, Research Design and Methodology, Timetable, and a Bibliography.

What is a Research Proposal?

A research proposal is a supporting document that may be required when applying to a research degree. It summarises your intended research by outlining what your research questions are, why they’re important to your field and what knowledge gaps surround your topic. It also outlines your research in terms of your aims, methods and proposed timetable .

What Is It Used for and Why Is It Important?

A research proposal will be used to:

- Confirm whether you understand the topic and can communicate complex ideas.

- Confirm whether the university has adequate expertise to support you in your research topic.

- Apply for funding or research grants to external bodies.

How Long Should a PhD Research Proposal Be?

Some universities will specify a word count all students will need to adhere to. You will typically find these in the description of the PhD listing. If they haven’t stated a word count limit, you should contact the potential supervisor to clarify whether there are any requirements. If not, aim for 1500 to 3500 words (3 to 7 pages).

Your title should indicate clearly what your research question is. It needs to be simple and to the point; if the reader needs to read further into your proposal to understand your question, your working title isn’t clear enough.

Directly below your title, state the topic your research question relates to. Whether you include this information at the top of your proposal or insert a dedicated title page is your choice and will come down to personal preference.

2. Abstract

If your research proposal is over 2000 words, consider providing an abstract. Your abstract should summarise your question, why it’s important to your field and how you intend to answer it; in other words, explain your research context.

Only include crucial information in this section – 250 words should be sufficient to get across your main points.

3. Background & Rationale

First, specify which subject area your research problem falls in. This will help set the context of your study and will help the reader anticipate the direction of your proposed research.

Following this, include a literature review . A literature review summarises the existing knowledge which surrounds your research topic. This should include a discussion of the theories, models and bodies of text which directly relate to your research problem. As well as discussing the information available, discuss those which aren’t. In other words, identify what the current gaps in knowledge are and discuss how this will influence your research. Your aim here is to convince the potential supervisor and funding providers of why your intended research is worth investing time and money into.

Last, discuss the key debates and developments currently at the centre of your research area.

4. Research Aims & Objectives

Identify the aims and objectives of your research. The aims are the problems your project intends to solve; the objectives are the measurable steps and outcomes required to achieve the aim.

In outlining your aims and objectives, you will need to explain why your proposed research is worth exploring. Consider these aspects:

- Will your research solve a problem?

- Will your research address a current gap in knowledge?

- Will your research have any social or practical benefits?

If you fail to address the above questions, it’s unlikely they will accept your proposal – all PhD research projects must show originality and value to be considered.

5. Research Design and Methodology

The following structure is recommended when discussing your research design:

- Sample/Population – Discuss your sample size, target populations, specimen types etc.

- Methods – What research methods have you considered, how did you evaluate them and how did you decide on your chosen one?

- Data Collection – How are you going to collect and validate your data? Are there any limitations?

- Data Analysis – How are you going to interpret your results and obtain a meaningful conclusion from them?

- Ethical Considerations – Are there any potential implications associated with your research approach? This could either be to research participants or to your field as a whole on the outcome of your findings (i.e. if you’re researching a particularly controversial area). How are you going to monitor for these implications and what types of preventive steps will you need to put into place?

6. Timetable

We’ve outlined the various stages of a PhD and the approximate duration of a PhD programme which you can refer to when designing your own research study.

7. Bibliography

Plagiarism is taken seriously across all academic levels, but even more so for doctorates. Therefore, ensure you reference the existing literature you have used in writing your PhD proposal. Besides this, try to adopt the same referencing style as the University you’re applying to uses. You can easily find this information in the PhD Thesis formatting guidelines published on the University’s website.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Questions & Answers

Here are answers to some of the most common questions we’re asked about the Research Proposal:

Can You Change a Research Proposal?

Yes, your PhD research proposal outlines the start of your project only. It’s well accepted that the direction of your research will develop with time, therefore, you can revise it at later dates.

Can the Potential Supervisor Review My Draft Proposal?

Whether the potential supervisor will review your draft will depend on the individual. However, it is highly advisable that you at least attempt to discuss your draft with them. Even if they can’t review it, they may provide you with useful information regarding their department’s expertise which could help shape your PhD proposal. For example, you may amend your methodology should you come to learn that their laboratory is better equipped for an alternative method.

How Should I Structure and Format My Proposal?

Ensure you follow the same order as the headings given above. This is the most logical structure and will be the order your proposed supervisor will expect.

Most universities don’t provide formatting requirements for research proposals on the basis that they are a supporting document only, however, we recommend that you follow the same format they require for their PhD thesis submissions. This will give your reader familiarity and their guidelines should be readily available on their website.

Last, try to have someone within the same academic field or discipline area to review your proposal. The key is to confirm that they understand the importance of your work and how you intend to execute it. If they don’t, it’s likely a sign you need to rewrite some of your sections to be more coherent.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write a Research Proposal as an Undergrad

As I just passed the deadline for my junior independent work (JIW), I wanted to explore strategies that could be helpful in composing a research proposal. In the chemistry department, JIW usually involves lab work and collecting raw data. However, this year, because of the pandemic, there is limited benchwork involved and most of the emphasis has shifted to designing a research proposal that would segue into one’s senior thesis. So far, I have only had one prior experience composing a research proposal, and it was from a virtual summer research program in my department. For this program, I was able to write a proposal on modifying a certain chemical inhibitor that could be used in reducing cancer cell proliferation. Using that experience as a guide, I will outline the steps I followed when I wrote my proposal. (Most of these steps are oriented towards research in the natural sciences, but there are many aspects common to research in other fields).

The first step is usually choosing a topic . This can be assigned to you by the principal investigator for the lab or a research mentor if you have one. For me, it was my research mentor, a graduate student in our lab, who helped me in selecting a field of query for my proposal. When I chose the lab I wanted to be part of for my summer project (with my JIW and senior thesis in mind) , I knew the general area of research I wanted to be involved in. But, usually within a lab, there are many projects that graduate students and post-docs work on within that specific area. Hence, it is important to identify a mentor with specific projects you want to be involved in for your own research. Once you choose a mentor, you can talk to them about formulating a research proposal based on the direction they plan to take their research in and how you can be involved in a similar project. Usually, mentors assign you one to three papers related to your research topic – a review paper that summarizes many research articles and one to two research articles with similar findings and methodology. In my case, the papers involved a review article on the role of the chemical inhibitor I was investigating along with articles on inhibitor design and mechanism of action.

The next step is to perform a literature review to broadly assess previous work in your research topic, using the articles assigned by your mentor. At this stage, for my proposal, I was trying to know as much about my research area from these papers as well as the articles cited in them. Here, it is helpful to use a reference management software such as Zotero and Mendeley to organize your notes along with all the articles you look into for a bibliography.

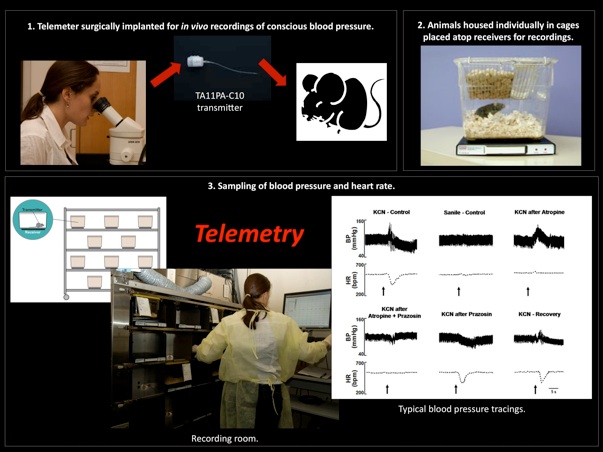

After going through your literature review, you can start thinking about identifying questions that remain to be answered in that field. For my JIW, I found some good ideas in the discussion section of the papers I had read where authors discussed what could be done in future research projects. One discussion section, for example, suggested ways to complement in-vitro experiments (outside of a living organism) with in-vivo ones (inside a living organism) . Reviewing the discussion section is a relatively straightforward way to formulate your own hypothesis. Alternatively, you could look at the papers’ raw data and find that the authors’ conclusions need to be revisited (this might require a critical review of the paper and the supplementary materials) or you could work on improving the paper’s methodology and optimizing its experiments. Furthermore, you might think about combining ideas from different papers or trying to reconcile differing conclusions reached by them.

The next step is developing a general outline ; deciding on what you want to cover in your proposal and how it is going to be structured. Here, you should try hard to limit the scope of your proposal to what you can realistically do for your senior thesis. As a junior or a senior, you will only be working with your mentor for a limited amount of time. Hence, it is not possible to plan long term experiments that would be appropriate for graduate students or post-docs in the lab. (For my summer project, there was not a follow up experiment involved, so I was able to think about possible experiments without the time or equipment constraints that would need to be considered for a JIW). Thus, your proposal should mostly focus on what you think is feasible given your timeline.

Below are two final considerations. It is important that your research proposal outlines how you plan to collect your own data , analyze it and compare it with other papers in your field. For a research project based on a proposal, you need only establish if your premises/hypotheses are true or false. To do that, you need to formulate questions you can answer by collecting your own data, and this is where experiments come in. My summer project had three specific aims and each one was in the form of a question.

It is important to keep in mind in your proposal the experiments you can perform efficiently on your own – the experimental skills you want to master as an undergraduate. In my view, it is better to learn one to two skills very well than having surface-level knowledge of many. This is because the nature of research has been very specialized in each field that there is limited room for broad investigations. This does not mean your proposal should be solely based on things you can test by yourself (although it might be preferable to put more emphasis there). If your proposal involves experiments beyond what you can learn to do in a year or two, you can think of asking for help from an expert in your lab.

A research proposal at the undergraduate level is an engaging exercise on coming up with your own questions on your chosen field. There is much leeway as an undergraduate to experiment within your field and think out of the box. In many ways, you will learn how to learn and how to formulate questions for any task you encounter in the future. Whether or not you want to be involved in research, it is an experience common to all Princeton students that you take with you after graduation.

In this post, I have described the basic elements of a natural science research proposal and my approach to writing one. Although the steps above are not comprehensive, I am hopeful they offer guidance you can adapt when you write your own proposal in the future.

— Yodahe Gebreegziabher, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

How to write your research proposal

A key part of your application is your research proposal. Whether you are applying for a self-funded or studentship you should follow the guidance below.

If you are looking specifically for advice on writing your PhD by published work research proposal, read our guide .

You are encouraged to contact us to discuss the availability of supervision in your area of research before you make a formal application, by visiting our areas of research .

What is your research proposal used for and why is it important?

- It is used to establish whether there is expertise to support your proposed area of research

- It forms part of the assessment of your application

- The research proposal you submit as part of your application is just the starting point, as your ideas evolve your proposed research is likely to change

How long should my research proposal be?

It should be 2,000–3,500 words (4-7 pages) long.

What should be included in my research proposal?

Your proposal should include the following:

- your title should give a clear indication of your proposed research approach or key question

2. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

You should include:

- the background and issues of your proposed research

- identify your discipline

- a short literature review

- a summary of key debates and developments in the field

3. RESEARCH QUESTION(S)

You should formulate these clearly, giving an explanation as to what problems and issues are to be explored and why they are worth exploring

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

You should provide an outline of:

- the theoretical resources to be drawn on

- the research approach (theoretical framework)

- the research methods appropriate for the proposed research

- a discussion of advantages as well as limits of particular approaches and methods

5. PLAN OF WORK & TIME SCHEDULE

You should include an outline of the various stages and corresponding time lines for developing and implementing the research, including writing up your thesis.

For full-time study your research should be completed within three years, with writing up completed in the fourth year of registration.

For part-time study your research should be completed within six years, with writing up completed by the eighth year.

6. BIBLIOGRAPHY

- a list of references to key articles and texts discussed within your research proposal

- a selection of sources appropriate to the proposed research

Related pages

Fees and funding.

How much will it cost to study a research degree?

Research degrees

Find out if you can apply for a Research Degree at the University of Westminster.

Research degree by distance learning

Find out about Research Degree distance learning options at the University of Westminster.

We use cookies to ensure the best experience on our website.

By accepting you agree to cookies being stored on your device.

Some of these cookies are essential to the running of the site, while others help us to improve your experience.

Functional cookies enable core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility.

Analytics cookies help us improve our website based on user needs by collecting information, which does not directly identify anyone.

Marketing cookies send information on your visit to third parties so that they can make their advertising more relevant to you when you visit other websites.

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Business How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

How to Write a Research Proposal: A Step-by-Step

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Nov 29, 2023

A research proposal is a structured outline for a planned study on a specific topic. It serves as a roadmap, guiding researchers through the process of converting their research idea into a feasible project.

The aim of a research proposal is multifold: it articulates the research problem, establishes a theoretical framework, outlines the research methodology and highlights the potential significance of the study. Importantly, it’s a critical tool for scholars seeking grant funding or approval for their research projects.

Crafting a good research proposal requires not only understanding your research topic and methodological approaches but also the ability to present your ideas clearly and persuasively. Explore Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates to begin your journey in writing a compelling research proposal.

What to include in a research proposal?

In a research proposal, include a clear statement of your research question or problem, along with an explanation of its significance. This should be followed by a literature review that situates your proposed study within the context of existing research.

Your proposal should also outline the research methodology, detailing how you plan to conduct your study, including data collection and analysis methods.

Additionally, include a theoretical framework that guides your research approach, a timeline or research schedule, and a budget if applicable. It’s important to also address the anticipated outcomes and potential implications of your study. A well-structured research proposal will clearly communicate your research objectives, methods and significance to the readers.

How to format a research proposal?

Formatting a research proposal involves adhering to a structured outline to ensure clarity and coherence. While specific requirements may vary, a standard research proposal typically includes the following elements:

- Title Page: Must include the title of your research proposal, your name and affiliations. The title should be concise and descriptive of your proposed research.

- Abstract: A brief summary of your proposal, usually not exceeding 250 words. It should highlight the research question, methodology and the potential impact of the study.

- Introduction: Introduces your research question or problem, explains its significance, and states the objectives of your study.

- Literature review: Here, you contextualize your research within existing scholarship, demonstrating your knowledge of the field and how your research will contribute to it.

- Methodology: Outline your research methods, including how you will collect and analyze data. This section should be detailed enough to show the feasibility and thoughtfulness of your approach.

- Timeline: Provide an estimated schedule for your research, breaking down the process into stages with a realistic timeline for each.

- Budget (if applicable): If your research requires funding, include a detailed budget outlining expected cost.

- References/Bibliography: List all sources referenced in your proposal in a consistent citation style.

How to write a research proposal in 11 steps?

Writing a research proposal template in structured steps ensures a comprehensive and coherent presentation of your research project. Let’s look at the explanation for each of the steps here:

Step 1: Title and Abstract Step 2: Introduction Step 3: Research objectives Step 4: Literature review Step 5: Methodology Step 6: Timeline Step 7: Resources Step 8: Ethical considerations Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance Step 10: References Step 11: Appendices

Step 1: title and abstract.

Select a concise, descriptive title and write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology and expected outcomes. The abstract should include your research question, the objectives you aim to achieve, the methodology you plan to employ and the anticipated outcomes.

Step 2: Introduction

In this section, introduce the topic of your research, emphasizing its significance and relevance to the field. Articulate the research problem or question in clear terms and provide background context, which should include an overview of previous research in the field.

Step 3: Research objectives

Here, you’ll need to outline specific, clear and achievable objectives that align with your research problem. These objectives should be well-defined, focused and measurable, serving as the guiding pillars for your study. They help in establishing what you intend to accomplish through your research and provide a clear direction for your investigation.

Step 4: Literature review

In this part, conduct a thorough review of existing literature related to your research topic. This involves a detailed summary of key findings and major contributions from previous research. Identify existing gaps in the literature and articulate how your research aims to fill these gaps. The literature review not only shows your grasp of the subject matter but also how your research will contribute new insights or perspectives to the field.

Step 5: Methodology

Describe the design of your research and the methodologies you will employ. This should include detailed information on data collection methods, instruments to be used and analysis techniques. Justify the appropriateness of these methods for your research.

Step 6: Timeline

Construct a detailed timeline that maps out the major milestones and activities of your research project. Break the entire research process into smaller, manageable tasks and assign realistic time frames to each. This timeline should cover everything from the initial research phase to the final submission, including periods for data collection, analysis and report writing.

It helps in ensuring your project stays on track and demonstrates to reviewers that you have a well-thought-out plan for completing your research efficiently.

Step 7: Resources

Identify all the resources that will be required for your research, such as specific databases, laboratory equipment, software or funding. Provide details on how these resources will be accessed or acquired.

If your research requires funding, explain how it will be utilized effectively to support various aspects of the project.

Step 8: Ethical considerations

Address any ethical issues that may arise during your research. This is particularly important for research involving human subjects. Describe the measures you will take to ensure ethical standards are maintained, such as obtaining informed consent, ensuring participant privacy, and adhering to data protection regulations.

Here, in this section you should reassure reviewers that you are committed to conducting your research responsibly and ethically.

Step 9: Expected outcomes and significance

Articulate the expected outcomes or results of your research. Explain the potential impact and significance of these outcomes, whether in advancing academic knowledge, influencing policy or addressing specific societal or practical issues.

Step 10: References

Compile a comprehensive list of all the references cited in your proposal. Adhere to a consistent citation style (like APA or MLA) throughout your document. The reference section not only gives credit to the original authors of your sourced information but also strengthens the credibility of your proposal.

Step 11: Appendices

Include additional supporting materials that are pertinent to your research proposal. This can be survey questionnaires, interview guides, detailed data analysis plans or any supplementary information that supports the main text.

Appendices provide further depth to your proposal, showcasing the thoroughness of your preparation.

Research proposal FAQs

1. how long should a research proposal be.

The length of a research proposal can vary depending on the requirements of the academic institution, funding body or specific guidelines provided. Generally, research proposals range from 500 to 1500 words or about one to a few pages long. It’s important to provide enough detail to clearly convey your research idea, objectives and methodology, while being concise. Always check

2. Why is the research plan pivotal to a research project?

The research plan is pivotal to a research project because it acts as a blueprint, guiding every phase of the study. It outlines the objectives, methodology, timeline and expected outcomes, providing a structured approach and ensuring that the research is systematically conducted.

A well-crafted plan helps in identifying potential challenges, allocating resources efficiently and maintaining focus on the research goals. It is also essential for communicating the project’s feasibility and importance to stakeholders, such as funding bodies or academic supervisors.

Mastering how to write a research proposal is an essential skill for any scholar, whether in social and behavioral sciences, academic writing or any field requiring scholarly research. From this article, you have learned key components, from the literature review to the research design, helping you develop a persuasive and well-structured proposal.

Remember, a good research proposal not only highlights your proposed research and methodology but also demonstrates its relevance and potential impact.

For additional support, consider utilizing Venngage’s Proposal Maker and Research Proposals Templates , valuable tools in crafting a compelling proposal that stands out.

Whether it’s for grant funding, a research paper or a dissertation proposal, these resources can assist in transforming your research idea into a successful submission.

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Choosing a Topic for a Research Paper or Presentation

- How Long Should Research Take?

- Getting Started

- Assigned topic?

- Choosing Resources to Support your Topic

Director for Research & Instruction

How Long Does Research Take?

How long the research process takes varies by:

- the nature of the assignment, how well the topic is covered in 'the literature'* (i.e., books, journals and other sources),

- what materials are available in our library or online,

- the length of time allotted for the assignment and

- the expertise of the researcher (i.e., what you know about the topic).

Things to keep in mind:

Start early so that you can revise your strategy or your paper if necessary. Some topics will have a huge amount of material available, while some will have little. If you need background material, subject encyclopedias may give more specific detail. Conducting research normally takes longer than you expect.

Frustration and backtracking are a normal part of the process. However, reference librarians can show you strategies that can save you time and can help you do your research more effectively.

Ask at the Help Desk, through Ask-us (chat), text to 479-385-0803 or email [email protected] for assistance.

You can use the Research Paper Wizard to help plan the sequence and find sources.

subject encyclopedias

Research Paper Wizard

*This is the published material about the topic. It is not "literature" as in fiction or drama, although there is literature about the field of literature, too.

- << Previous: Choosing Resources to Support your Topic

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/choosetopic

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.18(6); 2022 Jun

Ten simple rules for good research practice

Simon schwab.

1 Center for Reproducible Science, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2 Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Perrine Janiaud

3 Department of Clinical Research, University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Michael Dayan

4 Human Neuroscience Platform, Fondation Campus Biotech Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Valentin Amrhein

5 Department of Environmental Sciences, Zoology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Radoslaw Panczak

6 Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Patricia M. Palagi

7 SIB Training Group, SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Lausanne, Switzerland

Lars G. Hemkens

8 Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS), Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America

9 Meta-Research Innovation Center Berlin (METRIC-B), Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany

Meike Ramon

10 Applied Face Cognition Lab, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Nicolas Rothen

11 Faculty of Psychology, UniDistance Suisse, Brig, Switzerland

Stephen Senn

12 Statistical Consultant, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Leonhard Held

This is a PLOS Computational Biology Methods paper.

Introduction

The lack of research reproducibility has caused growing concern across various scientific fields [ 1 – 5 ]. Today, there is widespread agreement, within and outside academia, that scientific research is suffering from a reproducibility crisis [ 6 , 7 ]. Researchers reach different conclusions—even when the same data have been processed—simply due to varied analytical procedures [ 8 , 9 ]. As we continue to recognize this problematic situation, some major causes of irreproducible research have been identified. This, in turn, provides the foundation for improvement by identifying and advocating for good research practices (GRPs). Indeed, powerful solutions are available, for example, preregistration of study protocols and statistical analysis plans, sharing of data and analysis code, and adherence to reporting guidelines. Although these and other best practices may facilitate reproducible research and increase trust in science, it remains the responsibility of researchers themselves to actively integrate them into their everyday research practices.

Contrary to ubiquitous specialized training, cross-disciplinary courses focusing on best practices to enhance the quality of research are lacking at universities and are urgently needed. The intersections between disciplines offer a space for peer evaluation, mutual learning, and sharing of best practices. In medical research, interdisciplinary work is inevitable. For example, conducting clinical trials requires experts with diverse backgrounds, including clinical medicine, pharmacology, biostatistics, evidence synthesis, nursing, and implementation science. Bringing researchers with diverse backgrounds and levels of experience together to exchange knowledge and learn about problems and solutions adds value and improves the quality of research.

The present selection of rules was based on our experiences with teaching GRP courses at the University of Zurich, our course participants’ feedback, and the views of a cross-disciplinary group of experts from within the Swiss Reproducibility Network ( www.swissrn.org ). The list is neither exhaustive, nor does it aim to address and systematically summarize the wide spectrum of issues including research ethics and legal aspects (e.g., related to misconduct, conflicts of interests, and scientific integrity). Instead, we focused on practical advice at the different stages of everyday research: from planning and execution to reporting of research. For a more comprehensive overview on GRPs, we point to the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council’s guidelines [ 10 ] and the Swedish Research Council’s report [ 11 ]. While the discussion of the rules may predominantly focus on clinical research, much applies, in principle, to basic biomedical research and research in other domains as well.

The 10 proposed rules can serve multiple purposes: an introduction for researchers to relevant concepts to improve research quality, a primer for early-career researchers who participate in our GRP courses, or a starting point for lecturers who plan a GRP course at their own institutions. The 10 rules are grouped according to planning (5 rules), execution (3 rules), and reporting of research (2 rules); see Fig 1 . These principles can (and should) be implemented as a habit in everyday research, just like toothbrushing.

GRP, good research practices.

Research planning

Rule 1: specify your research question.

Coming up with a research question is not always simple and may take time. A successful study requires a narrow and clear research question. In evidence-based research, prior studies are assessed in a systematic and transparent way to identify a research gap for a new study that answers a question that matters [ 12 ]. Papers that provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research in the field are particularly helpful—for example, systematic reviews. Perspective papers may also be useful, for example, there is a paper with the title “SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions.” However, a systematic assessment of research gaps deserves more attention than opinion-based publications.

In the next step, a vague research question should be further developed and refined. In clinical research and evidence-based medicine, there is an approach called population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and time frame (PICOT) with a set of criteria that can help framing a research question [ 13 ]. From a well-developed research question, subsequent steps will follow, which may include the exact definition of the population, the outcome, the data to be collected, and the sample size that is required. It may be useful to find out if other researchers find the idea interesting as well and whether it might promise a valuable contribution to the field. However, actively involving the public or the patients can be a more effective way to determine what research questions matter.

The level of details in a research question also depends on whether the planned research is confirmatory or exploratory. In contrast to confirmatory research, exploratory research does not require a well-defined hypothesis from the start. Some examples of exploratory experiments are those based on omics and multi-omics experiments (genomics, bulk RNA-Seq, single-cell, etc.) in systems biology and connectomics and whole-brain analyses in brain imaging. Both exploration and confirmation are needed in science, and it is helpful to understand their strengths and limitations [ 14 , 15 ].

Rule 2: Write and register a study protocol

In clinical research, registration of clinical trials has become a standard since the late 1990 and is now a legal requirement in many countries. Such studies require a study protocol to be registered, for example, with ClinicalTrials.gov, the European Clinical Trials Register, or the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Similar effort has been implemented for registration of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). Study registration has also been proposed for observational studies [ 16 ] and more recently in preclinical animal research [ 17 ] and is now being advocated across disciplines under the term “preregistration” [ 18 , 19 ].

Study protocols typically document at minimum the research question and hypothesis, a description of the population, the targeted sample size, the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the study design, the data collection, the data processing and transformation, and the planned statistical analyses. The registration of study protocols reduces publication bias and hindsight bias and can safeguard honest research and minimize waste of research [ 20 – 22 ]. Registration ensures that studies can be scrutinized by comparing the reported research with what was actually planned and written in the protocol, and any discrepancies may indicate serious problems (e.g., outcome switching).

Note that registration does not mean that researchers have no flexibility to adapt the plan as needed. Indeed, new or more appropriate procedures may become available or known only after registration of a study. Therefore, a more detailed statistical analysis plan can be amended to the protocol before the data are observed or unblinded [ 23 , 24 ]. Likewise, registration does not exclude the possibility to conduct exploratory data analyses; however, they must be clearly reported as such.

To go even further, registered reports are a novel article type that incentivize high-quality research—irrespective of the ultimate study outcome [ 25 , 26 ]. With registered reports, peer-reviewers decide before anyone knows the results of the study, and they have a more active role in being able to influence the design and analysis of the study. Journals from various disciplines increasingly support registered reports [ 27 ].

Naturally, preregistration and registered reports also have their limitations and may not be appropriate in a purely hypothesis-generating (explorative) framework. Reports of exploratory studies should indeed not be molded into a confirmatory framework; appropriate rigorous reporting alternatives have been suggested and start to become implemented [ 28 , 29 ].

Rule 3: Justify your sample size

Early-career researchers in our GRP courses often identify sample size as an issue in their research. For example, they say that they work with a low number of samples due to slow growth of cells, or they have a limited number of patient tumor samples due to a rare disease. But if your sample size is too low, your study has a high risk of providing a false negative result (type II error). In other words, you are unlikely to find an effect even if there truly was an effect.

Unfortunately, there is more bad news with small studies. When an effect from a small study was selected for drawing conclusions because it was statistically significant, low power increases the probability that an effect size is overestimated [ 30 , 31 ]. The reason is that with low power, studies that due to sampling variation find larger (overestimated) effects are much more likely to be statistically significant than those that happen to find smaller (more realistic) effects [ 30 , 32 , 33 ]. Thus, in such situations, effect sizes are often overestimated. For the phenomenon that small studies often report more extreme results (in meta-analyses), the term “small-study effect” was introduced [ 34 ]. In any case, an underpowered study is a problematic study, no matter the outcome.

In conclusion, small sample sizes can undermine research, but when is a study too small? For one study, a total of 50 patients may be fine, but for another, 1,000 patients may be required. How large a study needs to be designed requires an appropriate sample size calculation. Appropriate sample size calculation ensures that enough data are collected to ensure sufficient statistical power (the probability to reject the null hypothesis when it is in fact false).

Low-powered studies can be avoided by performing a sample size calculation to find out the required sample size of the study. This requires specifying a primary outcome variable and the magnitude of effect you are interested in (among some other factors); in clinical research, this is often the minimal clinically relevant difference. The statistical power is often set at 80% or larger. A comprehensive list of packages for sample size calculation are available [ 35 ], among them the R package “pwr” [ 36 ]. There are also many online calculators available, for example, the University of Zurich’s “SampleSizeR” [ 37 ].

A worthwhile alternative for planning the sample size that puts less emphasis on null hypothesis testing is based on the desired precision of the study; for example, one can calculate the sample size that is necessary to obtain a desired width of a confidence interval for the targeted effect [ 38 – 40 ]. A general framework to sample size justification beyond a calculation-only approach has been proposed [ 41 ]. It is also worth mentioning that some study types have other requirements or need specific methods. In diagnostic testing, one would need to determine the anticipated minimal sensitivity or specificity; in prognostic research, the number of parameters that can be used to fit a prediction model given a fixed sample size should be specified. Designs can also be so complex that a simulation (Monte Carlo method) may be required.

Sample size calculations should be done under different assumptions, and the largest estimated sample size is often the safer bet than a best-case scenario. The calculated sample size should further be adjusted to allow for possible missing data. Due to the complexity of accurately calculating sample size, researchers should strongly consider consulting a statistician early in the study design process.