Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption: the role of trust as a cornerstone

- Muhammad Farrukh Shahzad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6578-4139 1 ,

- Shuo Xu 1 ,

- Weng Marc Lim 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Muhammad Faisal Hasnain 5 &

- Shahneela Nusrat 6

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 4 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

20 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Science, technology and society

Cryptocurrencies—i.e., digital or virtual currencies secured by cryptography based on blockchain technology, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum—have brought transformative changes to the global economic landscape. These innovative transaction methods have rapidly made their mark in the financial sector, reshaping the dynamics of the global economy. However, there remains a notable hesitation in its widespread acceptance and adoption, largely due to misconceptions and lack of proper guidance about its use. Such gaps in understanding create an opportunity to address these concerns. Using the technology acceptance model (TAM), this study develops a parsimonious model to explain the awareness, acceptance, and adoption of cryptocurrency. The model was assessed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with a sample of 332 participants aged 18 to 40 years. The findings suggest that cryptocurrency awareness plays a direct, positive, and significant role in shaping cryptocurrency adoption and that this positive relationship is mediated by factors that exemplify cryptocurrency acceptance, namely the ease of use and usefulness of cryptocurrency. The results also reveal that trust is a significant factor that strengthens these direct and mediating relationships. These insights emphasize the necessity of fostering an informed understanding of cryptocurrencies to accelerate their broader adoption in the financial ecosystem. By addressing the misconceptions and reinforcing factors like ease of use, usefulness, and trust, policymakers and financial institutions can better position themselves to integrate and promote cryptocurrency in mainstream financial systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

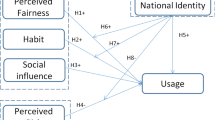

Extending UTAUT with national identity and fairness to understand user adoption of DCEP in China

Modeling innovation in the cryptocurrency ecosystem

Group norms and policy norms trigger different autonomous motivations for Chinese investors in cryptocurrency investment

Introduction.

Cryptocurrency has heralded a transformative shift in the global financial sector, offering a reimagined concept of money (Johar et al., 2021 ; Kakinaka and Umeno, 2022 ). Underpinned by blockchain and cryptography, cryptocurrency represents a novel class of digital or virtual currency. At its core, a blockchain serves as a decentralized ledger, chronicling every transaction across a distributed network of computers, assuring both transparency and permanence, whereas cryptography ensures that transactions are safeguarded against tampering and that participants’ identities remain confidential (Kumar et al., 2023 ; Sahoo et al., 2022 ). Popular examples of cryptocurrencies include Bitcoin and Ethereum. Unlike traditional currencies like the dollar or euro issued by central banks, cryptocurrencies function outside established financial systems. They are not tied to tangible assets like gold or governed by central financial institutions. Instead, they are created through a computational process called mining, which involves using computational power to solve complex mathematical problems, leading to the creation and verification of new transactions on a cryptocurrency network. While digital forms of money like Apple Pay or PayPal credits exist in the digital or online realm, they operate within the confines of traditional banking systems and lack the decentralized essence of blockchain (Jalan et al., 2023 ). On the other hand, cryptocurrencies, thanks to their inherent decentralized, transparent, and immutable nature, stand distinct and have ignited profound discussions in modern financial and technological arenas.

As per recent estimates, the aggregate value of transactions in digital payments is projected to reach US$9.46 trillion in 2023, with an expected annual increase of more than 11.8%, resulting in a total projection of US$14.78 trillion by 2027 (Siska, 2023 ). As the internet’s ubiquity grew, so did the shift from conventional cash payments to online transaction methods, reshaping global monetary systems (Sukumaran et al., 2022 ). Digital advancements and technological accessibility have also spurred an uptick in consumers engaging in online transactions via cryptocurrency (Kumar et al., 2021 ; Shin and Rice, 2022 ). For many, the allure of cryptocurrency lies in its borderless nature, simplicity, and speed (Galariotis and Karagiannis, 2020 ; Zafar et al., 2021 ). Indeed, cryptocurrency has reshaped the global financial infrastructure, compelling institutions to innovate in the digital transaction space (Khan et al., 2020 ). This momentum has spurred monetary systems to evolve, adapting and instituting policies that align with technological progress (Hasan et al., 2022 ).

A comprehensive understanding of cryptocurrencies is crucial in the current digital age (Uematsu and Tanaka, 2019 ). The growing popularity of cryptocurrencies is evident, especially as they herald transformative changes in global money markets (Tandon et al., 2021 ). Yet, adoption is tempered by challenges. While technology awareness can enhance acceptance, issues like limited technological know-how and understanding of online trading, legislative constraints, and security concerns act as deterrents (Albayati et al., 2020 ; Li et al., 2023 ; Rejeb et al., 2023 ). Moreover, while studies suggest that cryptocurrencies could promote financial inclusivity for underrepresented demographics, concerns remain about unequal wealth distribution among cryptocurrency holders (Abdul-Rahim et al., 2022 ; Allen et al., 2022 ). Recognizing the intricacies of cryptocurrency is crucial in today’s digital age, ensuring individuals stay abreast of technological advances (Yayla et al., 2023 ).

The present study argues that understanding cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption is imperative in today’s evolving digital financial landscape. As cryptocurrency positions itself at the forefront of financial innovation, comprehending the factors that drive or deter its acceptance can offer valuable insights into shaping future economic policies, strategies, and infrastructures. Awareness speaks to the extent of knowledge and understanding individuals have about cryptocurrency; acceptance gauges their openness to adopting it as a part of their financial behaviors; and adoption reflects the incorporation of cryptocurrency into their monetary transactions. Moreover, the role of trust as a moderator is especially crucial. Trust, or the lack thereof, can significantly influence an individual’s decision-making process concerning cryptocurrency. In an environment where transactions are decentralized and often lack traditional oversight, trust can be the linchpin that determines whether an individual engages with or shies away from cryptocurrency. By examining the moderating role of trust, we can better understand the psychological factors that play a pivotal role in cryptocurrency’s broader acceptance and usage in society.

Given the above, the goal of this study is to examine the relationships between cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption, as well as the moderating role of trust in these relationships. To do so, this study adopts the technology acceptance model (TAM) as a theoretical lens, wherein the technology in point is cryptocurrency. Essentially, TAM assumes that the acceptance of a technology could be understood by its ease of use and usefulness, which in turn shapes the adoption of that technology (Davis, 1989 ). Extending this theory, this study introduces (i) the concept of awareness, which is posited to exert a positive influence on consumers’ perception of the ease of use and usefulness of the technology on the basis that consumers are in a better position to form an opinion about a technology when they are knowledgeable about that technology, and (ii) the notion of trust, which is proposed to strengthen the relationship between awareness, acceptance, and adoption on the basis that trust acts as an enabler, mitigating potential fears and uncertainties associated with the adoption of new technologies, particularly in financial transactions where credibility and security and are paramount.

This study contributes to both theory and practice in several significant ways. Theoretically, by adopting and extending TAM to the realm of cryptocurrency, we strive to not only affirm the theoretical generalizability of the theory but also illuminate how awareness and trust play pivotal roles in the acceptance and adoption of such innovative financial technologies, which answered the call by past scholars such as (Farrukh et al., 2023 ; Kumar et al., 2021 ). By integrating the concept of awareness into TAM, this study posits that a heightened level of understanding can bolster consumers’ perceptions regarding the ease of use and usefulness of cryptocurrencies. In doing so, this research will enrich TAM by accounting for the influence of awareness in the adoption of emerging technologies. Furthermore, the introduction of trust as a moderating variable elucidates how confidence can amplify or mitigate the relationships between awareness, acceptance, and adoption of cryptocurrency. This presents a nuanced understanding of the psychological facets that underpin the decision-making processes surrounding technology adoption in financial contexts. The use of TAM as a foundational theoretical lens and the inclusion of new variables like awareness and trust into the model is in line with the recommendation of Lim ( 2018 ) for contributions amounting to theoretical generalizability and extension in relation to the theory. Practically, the findings of this study can guide policymakers, financial institutions, and tech developers in recognizing the crucial factors that drive or inhibit the mass adoption of cryptocurrency. By discerning the importance of awareness and trust, stakeholders can develop targeted educational campaigns and security measures, respectively, to bolster the public’s confidence and understanding of cryptocurrencies. In essence, this research offers strategic insights to industries and governments, enabling them to tailor their initiatives in promoting a more inclusive, transparent, and trustworthy digital financial landscape.

Theoretical background: technology acceptance model (TAM)

TAM is pivotal in predicting and explaining technology adoption behaviors. At its core, TAM posits two central constructs that determine one’s intention to accept and adopt a new technology: perceived ease of use (PEOU) and perceived usefulness (PU) (Davis, 1989 ). PEOU refers to the degree to which one believes that using a particular technology would be free from effort (Sagheer et al., 2022 ). Essentially, the simpler and more straightforward a technology is perceived, the more likely it is to be adopted. This is founded on the principle that individuals are naturally inclined to choose technologies that do not require significant effort or time (Siagian et al., 2022 ). Second, PU is centered on one’s belief that utilizing a particular technology will enhance their performance (Fagan et al., 2012 ). It captures the value proposition of the technology: if people deem a technology as beneficial and enhancing their productivity or efficiency, they are more inclined to use it (Lu et al., 2022 ). Through PEOU and PU, one’s intention toward technology adoption is kindled (Davis, 1989 ).

TAM is a robust theoretical framework that aids consumers in making informed decisions regarding the embrace of technological advancements (Lim, 2018 ). Our study underscores the relevance of TAM’s acceptance elements, specifically PEOU and PU, in gauging consumers’ intention towards adopting cryptocurrency. Evidently, past scholars have consistently utilized TAM as a cornerstone theory in assessing individual behavior concerning the uptake of novel technologies (Kumar et al., 2021 ; Sagheer et al., 2022 ; Shahzad et al., 2018 ; Yuen et al., 2021 ).

In the ever-evolving landscape of cryptocurrency, there remains a noticeable dearth of scholarly attention on its utilization as a medium of exchange (Khan et al., 2020 ). Addressing this gap, our study endeavors to craft a theoretical framework, firmly anchored in TAM, to shed light on the determinants of cryptocurrency adoption. It is imperative to acknowledge that intentions stand as potent precursors of actions, with these intentions being invariably shaped by an individual’s attitudes and perceptions toward a specific endeavor (Davis, 1989 ; Lim, 2018 ).

Conceptual background: cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency, fundamentally a digital or virtual form of currency utilizing cryptography for security, made its debut in 2008 through a white paper published by an individual or group under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto; this innovation was later introduced in 2009 (Tauni et al., 2015 ). These digital assets offer decentralized control as opposed to centralized banking systems, promoting financial autonomy and inclusivity.

As a testament to its transformative potential, recent research highlights its increasing influence in various sectors of life, from remittances to cross-border trade (Parate et al., 2023 ). Given its rising economic significance, numerous countries are gradually recognizing and shifting towards cryptocurrency. With its decentralized nature, individuals find appeal in the autonomy, privacy, and potential returns it promises, away from traditional banking systems (Bibi, 2023 ).

Cryptocurrency can be broken down into two components: ‘crypto’ and ‘currency’. While ‘crypto’ refers to cryptography that secures user information and transactions, ‘currency’ is simply a medium of exchange. Globally, cryptocurrency has initiated significant changes in the financial sector, especially in developing countries. Noteworthily, a distinct characteristic of certain cryptocurrencies is their limited supply, which, for some, offers a potential hedge against inflation. This contrasts with traditional fiat currencies, which can be influenced by central bank policies (Allen et al., 2022 ). With more individuals adopting cryptocurrency, there is potential for a shift in the demand for traditional banking services, subsequently influencing interest rates and banks’ profitability (Tandon et al., 2021 ). Put simply, cryptocurrency represents a digital equivalent of cash that promises quicker, more reliable, and cost-effective transactions than its government-issued counterparts (Entrialgo, 2017 ). Its popularity has surged in recent years, as evidenced by its prominence in trading indices (Kher et al., 2021 ). Hence, this study zeroes in on the individual intention to adopt cryptocurrency.

Yet, the path to widespread adoption of cryptocurrency is not without hurdles. Among the challenges, environmental concerns related to the energy-intensive mining processes of certain cryptocurrencies have sparked debates on their sustainability (Rejeb et al., 2023 ). With regulatory landscapes still maturing, many investors approach this technology with caution due to potential risks (Shahzad et al., 2018 ). Common barriers include the nascent stage of cryptocurrency development, restricted access to advanced technology, and marketplace challenges such as unstructured trading environments, undefined financial regulations, and heightened security risks (Aboalsamh et al., 2023 ). Addressing these concerns, this study seeks to provide insights into the potential digital evolution awaiting individuals. The significance of cryptocurrencies as a potential mainstay in global finance is undeniable (Granić and Marangunić, 2019 ).

Leading financial markets, including the U.S., are actively researching and considering integrating cryptocurrency into their financial ecosystems (Hasgül et al., 2023 ). The horizon seems promising, with evolving technological solutions aiming to address current challenges and projections hinting at an even more integrated role of cryptocurrencies in global finance.

Taking Pakistan as a case study, its largely cash-driven economy juxtaposes with its youthful population and growing internet accessibility—factors ripe for digital payment adoption. In this regard, cryptocurrency’s potential as a trusted financial instrument in developing countries like Pakistan is substantial. Historical data indicates a rising preference for virtual currencies over traditional payment methods in regions like this (Arpaci et al., 2023 ). In an exemplary move, El Salvador passed the Bitcoin law in June 2021, granting it legal tender status alongside the U.S. dollar. This step, intended to streamline daily transactions and reduce remittance costs, has been met with diverse reactions globally (Gaikwad and Mavale, 2021 ). Its long-term impact, especially in the domain of remittances, remains under scrutiny (Howson and de Vries, 2022 ).

Hypotheses development

Cryptocurrency awareness and adoption.

Awareness plays a pivotal role in the acceptance and adoption of new technologies. Tracing back to diffusion innovation theory, awareness is considered the initial phase, crucial for the success of subsequent adoption stages (Lu et al., 2022 ). Building on this foundational understanding, studies examining technology implementation have reaffirmed the positive association between awareness levels and attitudes toward novel technologies (Arpaci et al., 2023 ).

An individual’s awareness encapsulates their comprehension of its advantages, potential drawbacks, and practical methods for its utilization (Zou et al., 2023 ). Consequently, the depth of a person’s awareness often sways their perceptions and, more critically, their readiness to adopt. A compelling parallel can be found in behavioral intention, a metric that gauges the likelihood of users engaging in a specific action. This metric plays a decisive role in both the determination to integrate cryptocurrency into one’s financial portfolio (Li, 2023 ). Historically, a robust behavioral intention has been a harbinger of successful technology adoption, diminishing the risk of committing to unsuitable or inferior innovations (Mizanur and Sloan, 2017 ; Siagian et al., 2022 ).

Recent empirical evidence corroborates this relationship between awareness and adoption. For instance, (Kakinaka and Umeno, 2022 ) highlighted that heightened awareness invariably bolstered positive intentions toward technology adoption. This intrinsic connection between cognitive awareness and behavioral outcomes serves as a cornerstone of our investigation. Intriguingly, the association between self-conceptualized technology awareness and behavior is not merely anecdotal but is underpinned by empirical studies. For example, (Gupta and Arora, 2020 ) underscored how nuanced technology awareness could shape individuals’ propensity to assimilate cryptocurrency into their financial activities.

Given the increasing emphasis on behavioral intention as a reliable predictor of technology adoption (Nadeem et al., 2021 ) our research delves into the interplay between technology awareness and the predisposition toward digital assets like cryptocurrency. In light of the aforementioned discussion and supporting evidence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1 . Cryptocurrency awareness exerts a positive influence on cryptocurrency adoption.

The mediating role of cryptocurrency ease of use

Ease of use stands as a pivotal factor in determining the adoption of new technologies (Lim, 2018 ). The more intuitive and straightforward a technology appears, the higher the likelihood of its widespread acceptance (Sagheer et al., 2022 ). As a technology’s usability becomes evident, individuals are more inclined to integrate it into their routine. This notion is central to TAM, which has been widely acknowledged in the tech domain (Sudzina et al., 2023 ).

The emphasis on ease of use stems from a need to create technologies that are accessible, responsive, and adaptable. When people find a technology to match these criteria, they are more inclined to adopt that technology. It is about meeting the needs of consumers without inundating them with unnecessary complexity (Nadeem et al., 2021 ). While over-simplification might occasionally deter usage, efficient tools that streamline processes generally receive consumers’ approval (Wibasuri, 2022 ).

Historical evidence suggests a strong association between ease of use and behavioral intentions toward the adoption of novel technologies. For instance, Albayati et al. ( 2020 ) and Treiblmaier and Sillaber ( 2021 ) explored this connection, though only Shahzad et al. ( 2018 ) provided particularly insightful findings. Current research builds on this foundation, investigating the belief that user-friendliness and efficiency in cryptocurrencies can enhance user experience and, consequently, adoption rates. Furthermore, this study aligns with past research (Siagian et al., 2022 ), emphasizing the connection between technology awareness and the intention to adopt the technology. It recognizes the vital role of ease of use as a bridge between these elements.

To this end, numerous studies have already highlighted the profound impact of ease of use on shaping intentions towards new technological integrations (Biswas et al., 2021 ; Chen and Aklikokou, 2020 ). With this context in mind, our research specifically delves into how bolstering ease of use can pave the way for broader cryptocurrency adoption. Based on the synthesis of the above discussions, we put forth:

H2 . Cryptocurrency ease of use significantly mediates the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness and adoption.

The mediating role of cryptocurrency usefulness

Usefulness reflects the consumers’ belief that embracing a novel technology will enhance their performance (Davis, 1989 ; Lim, 2018 ). Prior research underscores that consumers are more likely to embrace cryptocurrency if they deem it beneficial (Kim et al., 2021 ). Historically, usefulness has been a cornerstone determinant of TAM, underscoring its centrality in assessing technological innovations (Fagan et al., 2012 ; Salas, 2020 ). Its role in information systems, such as facilitating the ease of adoption of cryptocurrency, is indeed substantial (Albayati et al., 2020 ).

As digital platforms burgeon, consumers increasingly derive their understanding of a technology’s usefulness from these platforms. This sentiment aligns with our study’s emphasis: online platforms serve as a conduit through which people gauge the usefulness of cryptocurrency. The decision to engage with or refrain from technology often hinges on its utility (Theiri et al., 2022 ). Past research has ventured into examining the role of usefulness in influencing behavioral intentions, but the findings have been mixed, prompting further inquiry (Basuki et al., 2022 ). For instance, consumers frequently endorse applications that are skillful, user-friendly, and competent, as these qualities often correlate with the usefulness of the tool (Granić and Marangunić, 2019 ). Yet, factors such as changing regulatory landscapes or environmental uncertainties can modulate consumers’ perceptions of a technology’s usefulness (Stocklmayer and Gilbert, 2002 ). Some prior studies, interestingly, have highlighted that consumers’ inclinations were swayed more by entertainment values than sheer usefulness, illuminating the multifaceted nature of consumer engagement (Abdul-Rahim et al., 2022 ).

Literature has consistently underscored the symbiotic relationship between awareness of technology and its perceived usefulness in shaping behavioral intentions. Notably, Namahoot and Rattanawiboonsom ( 2022 ) contended that consumers found electronic payments, including those using cryptocurrency, useful. This assertion is buttressed by other studies that emphasize the direct impact of technological awareness on behavioral intention through the prism of usefulness (Almajali et al., 2022 ; Sagheer et al., 2022 ). Noteworthily, a survey by Chen and Aklikokou ( 2020 ) illuminated the mediating role of usefulness in amplifying adoption behavior. Delving deeper into this interplay Schaupp and Festa ( 2018 ) pondered the ease with which newcomers could adopt cryptocurrency, positing that those acquainted with digital currencies are naturally more receptive, given the usefulness they derive from it. This is further validated by research in China (Shahzad et al., 2018 ), which determined that usefulness was a positive determinant for cryptocurrency adoption. In light of the aforementioned insights and findings, our hypothesis is articulated as:

H3 . Cryptocurrency usefulness significantly mediates the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness and adoption.

The moderating role of cryptocurrency trust

Trust in the context of innovative technologies refers to a consumer’s comfort, confidence, and assurance in its utilization (Quan et al., 2023 ). It is a cornerstone of acceptance and adoption, determining whether individuals feel secure in embracing new innovations (Akther and Nur, 2022 ). Over time, the evolution of social relationships has underscored the importance of consistent trust when adopting new technologies (Matemba and Li, 2018 ). Studies, such as those by Hasan et al. ( 2022 ), emphasized that heightened trust typically amplifies the adoption rate of technologies, especially those in their nascent stages. By fostering trust in cryptocurrency, the present study seeks to pave the way for its broader acceptance and adoption.

In digital commerce, where intangibility is a given, trust is paramount. Such trust encourages users to engage safely, reducing uncertainties and reservations (Shin and Rice, 2022 ). Mutual trust between users and providers is essential. Trust solidifies user-provider relationships and ensures sustained confidence in new ventures (Sukumaran et al., 2022 ). Essentially, trustworthy entities reduce risks, propelling individuals to explore and adopt. Research has shown that those with a positive inclination towards digital technologies display a stronger affinity for acceptance, contingent upon factors like trust and associated security measures (Völter et al., 2021 ). This is corroborated by Utz et al. ( 2022 ) who posited that trust fortifies individuals’ intention to use blockchain, a technology in which cryptocurrency operates upon.

Moreover, trust safeguards consumers’ financial and personal information, symbolizing a heightened level of confidence in cryptocurrency adoption (Tan and Saraniemi, 2022 ). A significant observation from past research is that when user trust wanes, their risk aversion decreases, and they become more susceptible to pitfalls (Sukumaran et al., 2022 ). A pivotal point raised by researchers, such as McCloskey ( 2006 ), is that trust plays a determinative role in influencing a user’s perception of how easy and useful a technology is. Trust, therefore, emerges as a linchpin that shapes user behavior, especially concerning ease of use and usefulness of technology (Albayati et al., 2020 ; Deebak et al., 2022 ).

In the midst of the prevailing discourse on technology adoption, trust emerges as a crucial determinant. The current study delves into the moderating role of trust, examining its influence on the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance (ease of use, usefulness), and adoption. Our study seeks to clarify the nuances of this relationship, thereby enriching understanding and advancing the field. Specifically, trust in cryptocurrency is rooted in blockchain-based consensus protocols, such as proof of stake. This foundational trust enhances people’s confidence to adopt cryptocurrency, with TAM predictors serving as key indicators of this trust chain. In light of these considerations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a . Cryptocurrency trust significantly moderates the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness, ease of use, and adoption.

H4b . Cryptocurrency trust significantly moderates the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness, ease of use, and adoption.

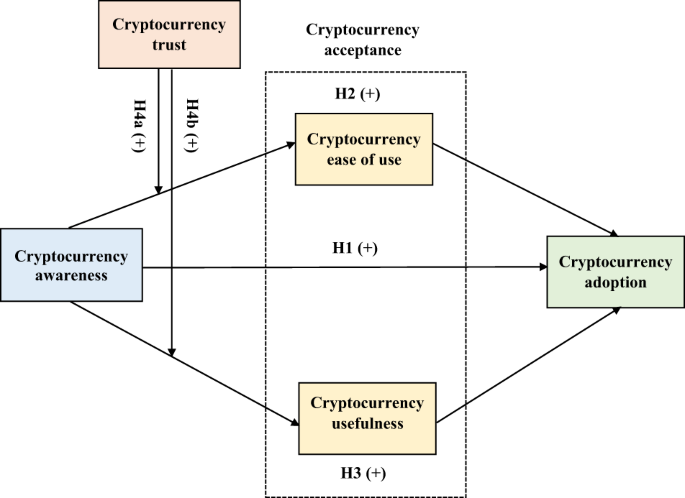

The conceptual framework, which depicts the hypothesized relationships, is presented in Fig. 1 . Essentially, cryptocurrency awareness is expected to shape cryptocurrency adoption positively, with the ease of use and usefulness of cryptocurrency mediating this relationship, and the trust in cryptocurrency strengthening these mediating relationships.

The cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption model.

Instrumentation

The study utilized a survey-based approach to gauge respondents’ awareness, acceptance, and adoption of cryptocurrency. Drawing from existing literature, a questionnaire was designed, ensuring that it is tailored to fit the scope and focus of this investigation (Shahzad et al., 2022 ). The items in the questionnaire were measured using a five-point Likert scale, with the following constructs:

Cryptocurrency awareness

This construct deals with an individual’s understanding of cryptocurrency. For this study, it was operationalized with eight items adopted from Sagheer et al. ( 2022 ).

Cryptocurrency ease of use

Addressing an individual’s perception regarding the simplicity of embracing cryptocurrency, six items from Chen and Aklikokou ( 2020 ) were used.

Cryptocurrency usefulness

Signifying an individual’s belief in how the adoption of cryptocurrency can augment their efficiency, this was gauged through six items, with references from Albayati et al. ( 2020 ).

Cryptocurrency trust

Critical to the acceptance process, trust helps potential adopters believe in the credibility and reliability of cryptocurrency. Trust was evaluated through five items based on the work of Shahzad et al. ( 2018 ).

Cryptocurrency adoption

Representing an individual’s projected likelihood of adopting cryptocurrency, this was defined through five items, also taken from Shahzad et al. ( 2018 ).

While the emerging acceptance of cryptocurrency can be witnessed across various age groups, this study specifically targeted individuals aged 18 to 40 years in Lahore, Pakistan. The choice of this sampling area, with its blend of institutions and vibrant economic activities, ensured the representation of various sub-groups including university students, government/private employees, and business owners (Shahzad et al., 2021 ).

The data collection process initiated with screening questions, determining the familiarity with digital tools and internet use, as these were pre-requisites of actual or potential adoption of cryptocurrency. This phase ensured that only the relevant participants, who met the established criteria, were considered.

A total of 551 questionnaires were distributed both physically and online to individuals who passed the screening criteria and voluntarily consented to participate in the cryptocurrency survey. After accounting for missing values, outliers, and other discrepancies, 332 responses were deemed suitable for further analysis, yielding a usable response rate of 60.2%. This number aligns with Roscoe et al. ( 1975 ), who recommend a sample size ranging between 30 and 500 for empirical investigations. Among these respondents, 100% were familiar with digital tools, and 39% reported spending over seven hours daily on the internet, indicating a tech-savvy sample. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses to ensure candidness in their answers.

Profile of participants

The sample for the study comprised a diverse group of participants spanning various demographics. Table 1 presents a comprehensive profile of the participants based on gender, age, education, and occupation.

Among the 332 respondents, the gender distribution was fairly balanced. Women represented a slight majority, accounting for 54% ( n : 178) of the sample, while men constituted 46% ( n : 154).

The age distribution revealed that a significant majority of the participants were relatively young. Those in the age group of 18 to 30 years formed the largest chunk, representing 71% ( n : 235) of the total sample. Respondents aged between 31 to 40 years constituted 29% ( n : 97).

Delving into educational qualifications, a significant portion of the participants held a bachelor’s degree, representing 45% ( n : 150) of the sample. Those with a master’s degree formed 35% ( n : 115) of the respondents. Participants with a diploma accounted for 16% ( n : 52), and a very small fraction held a doctoral degree, constituting 2% ( n : 8) of the sample. Other educational qualifications, which could include certifications from online courses, were held by 2% ( n : 7) of the participants.

In terms of the professional backgrounds of the participants, a predominant 66% ( n : 218) were students, which aligns with the age distribution. Business owners and private sector employees were equally represented at 13% each ( n : 45 and n : 44, respectively). Government employees made up a smaller portion of the sample at 8% ( n : 25).

Measurement model

To establish the appropriateness and accuracy of our measurement model, we employed the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) algorithm, a method extensively applied in related research. The assessment focused on three critical aspects: reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, each of which contributes significantly to the robustness of the model and its resultant interpretations (Farrukh et al., 2023 ). Table 2 delineates the main statistical indices—i.e., Cronbach’s alpha ( α ), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE)—associated with each construct of our measurement model.

For internal consistency, an evaluation criterion based on Cronbach’s alpha was utilized. Introduced by Lee Cronbach in 1951, this metric determines how closely related a set of items are to each other within a construct (Sarstedt et al., 2014 ). A value closer to 1 indicates a higher consistency among the items, with values above 0.7 being regarded as indicative of good internal reliability (Voorhees et al., 2016 ). As observed in Table 2 , all constructs exceeded this threshold, signaling a high degree of internal consistency. To supplement the insights gleaned from Cronbach’s alpha and address its limitations, composite reliability was employed. This metric evaluates the internal consistency of the variables based on outer loading values (Martins et al., 2023 ). Akin to our findings for Cronbach’s alpha, the CR values for all constructs, as depicted in Table 2 , comfortably exceeded the 0.7 benchmark.

Convergent validity, which underscores the degree to which items of a construct are positively correlated, was assessed using AVE. In line with the criteria proposed by Sarstedt et al. ( 2014 ), AVE values above 0.5 denote satisfactory convergent validity. As evidenced in Table 2 , all constructs not only met but often exceeded this criterion, pointing to strong convergent validity.

Discriminant validity measures the extent to which a construct is truly distinct from others in the model (Martins et al., 2023 ; Shahzad, Xu, Khan, et al., 2023 ; Shahzad, Xu, Rehman, et al., 2023 ). This distinctiveness ensures that the constructs do not overlap, adding credence to the model’s unique explanations for the observed phenomena (Martins et al., 2023 ). We employed the Fornell-Larcker ( 1981 ) criterion for this purpose. Essentially, for robust discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE for a given construct should exceed its highest correlation with any other construct (Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ). Table 3 provides a matrix depicting these values. The diagonal, representing the square root of AVE values, is consistently larger than the off-diagonal values in their respective rows and columns, which are the correlations between constructs.

Structural model

The structural model’s examination offers insights into the relationships between constructs and evaluates the hypothesized pathways (Farrukh et al., 2023 ). Using bootstrapping in PLS-SEM, we deciphered the direct, mediating, and moderating effects of the constructs concerning cryptocurrency adoption. Table 4 provides a summary of these findings.

Main effects

The hypothesis positing a relationship between cryptocurrency awareness and cryptocurrency adoption (H 1 ) displayed a β -value of 0.192, significant at the 0.05 level. This means that as cryptocurrency awareness increases, there is a corresponding increase in the likelihood of cryptocurrency adoption. This supports the notion that more knowledgeable or informed individuals about cryptocurrencies are more inclined to adopt them. The fact that H 1 is supported highlights the importance of educating and raising awareness among potential users to promote cryptocurrency adoption.

Other observations indicate that enhanced cryptocurrency awareness bolsters the perception of its ease of use ( β : 0.470, p < 0.01) and its overall usefulness ( β : 0.288, p < 0.001), and that the ease of use ( β : 0.220, p < 0.01) and usefulness ( β : 0.134, p < 0.05) of cryptocurrency are significant determinants of its adoption. Noteworthily, a heightened trust in cryptocurrency significantly augments its ease of use ( β : 0.224, p < 0.01) and usefulness ( β : 0.220, p < 0.01). Additionally, the R 2 values depict the proportion of variance in the dependent variable predicted by the independent variable(s). The current model elucidates 51.5% of the variance in cryptocurrency ease of use, 14.8% in cryptocurrency usefulness, and 18.9% in cryptocurrency adoption.

Mediation effects

The hypothesis suggesting that cryptocurrency awareness indirectly informs cryptocurrency adoption via its ease of use (H 2 ) is significant, with a β -value of 0.103 ( p < 0.01). As such, H 2 is supported. Similarly, the pathway from cryptocurrency awareness via its usefulness to its adoption (H 3 ) is corroborated with a significant β -value of 0.038 ( p < 0.05). As a result, H 3 is supported.

Noteworthily, mediating effects reveal the mechanism or process through which an independent variable influences a dependent variable. The positive β -value of 0.103 for H 2 indicates that an increase in cryptocurrency awareness boosts the perception of its ease of use, which subsequently amplifies the rate of cryptocurrency adoption. This finding emphasizes the importance of not only making potential users aware of cryptocurrencies but also ensuring that they find the technology easy to use. The easier a potential user perceives the use of cryptocurrencies, the higher the likelihood they will adopt it—especially when they are well-informed or aware. Similarly, the positive β -value of 0.038 for H 3 suggests that an enhanced awareness of cryptocurrency leads to an increased perception of its usefulness, consequently fostering its adoption. This points towards the value of positioning cryptocurrencies as not just a novel technology, but as a tool that has tangible benefits and applications in everyday life. An informed individual who perceives cryptocurrencies as beneficial or useful is more likely to embrace them.

Moderation effects

The hypothesis indicating that cryptocurrency trust moderates the pathway between cryptocurrency awareness, its ease of use, and subsequent adoption (H4a) is supported by a significant β -value of 0.164 ( p < 0.05). Trust also appears to play a moderating role between cryptocurrency awareness and its perceived usefulness, affecting its adoption (H4b). This is evidenced by a significant β -value of 0.117 ( p < 0.05), thus supporting H4b.

The positive β -values for the moderating effect of cryptocurrency trust on the relationships in H 4a and H 4b underscore the enhancing role trust plays in these relationships. For H 4a , with a β -value of 0.164, this suggests that as trust in cryptocurrency increases, the positive relationship between cryptocurrency awareness and its ease of use in predicting cryptocurrency adoption becomes even stronger. This can be interpreted as trust amplifying the effect of awareness on adoption through ease of use. It implies that when individuals have higher trust in cryptocurrency, the awareness they have about it becomes more effective in shaping their perceptions of its ease of use, subsequently leading to higher adoption rates. Similarly, for H 4b , the positive β -value of 0.117 implies that increased trust in cryptocurrency augments the relationship between cryptocurrency awareness and its usefulness in determining adoption. This indicates that the beneficial effect of being aware of cryptocurrency on its usefulness becomes more pronounced when individuals trust cryptocurrency. This elevated perception of usefulness, in turn, makes it more likely for them to adopt cryptocurrency.

In the digital age, with technological advancements creating ripples throughout every industry, the finance sector has also seen significant shifts. Cryptocurrency, a nascent financial instrument, has brought about a paradigm shift in the way we perceive and handle monetary transactions. These digital assets, from their inception, have not only prompted discussions around technological intricacies but have also spurred debates in relation to awareness, usability, and trust. Our study aims to add to this discourse by illuminating cryptocurrency awareness, acceptance, and adoption.

On cryptocurrency awareness as the main predictor

The current research confirms that a clear understanding or awareness of cryptocurrency plays a pivotal role in its adoption. This aligns with the intuitive idea that when people understand something, they are more likely to engage with it. This finding resonates with Gong et al. ( 2023 ) assertion that a person’s ability to recognize and comprehend the efficacy of a technological innovation, in this case, cryptocurrency, is crucial for its acceptance in the market. Essentially, the more informed an individual is about cryptocurrency, the more likely they are to venture into its use without apprehension.

On cryptocurrency, ease of use, and usefulness as mediators

The present study also illuminates the vital roles that cryptocurrency ease of use and usefulness play in the adoption process. These factors essentially dictate the user’s experience and the perceived tangible benefits of engaging with cryptocurrency.

On the one hand, cryptocurrency ease of use emphasizes the importance of user-friendly experiences in technology adoption, a sentiment resonant with Chen and Aklikokou ( 2020 ) research. If potential users perceive a technology as complicated or inaccessible, they are less likely to engage with it, even if they are aware of its existence.

On the other hand, cryptocurrency’s usefulness underscores the tangible benefits users derive from the technology. This aligns with Theiri et al. ( 2022 ) assertion that the perceived usefulness of technological innovation can heavily impact one’s intent to engage with it. For cryptocurrencies to become mainstream, platforms need to clearly elucidate not just the ‘how-to’ but also the ‘why’ of their technology.

On cryptocurrency trust as a moderator

The discussion on cryptocurrency adoption is incomplete without addressing cryptocurrency trust. Trust emerges as a significant moderator, bridging the gap between awareness and adoption. The research aligns with Zafar et al. ( 2021 ) stance that trust can significantly reduce the ambiguity and potential perceived risks associated with adopting new technologies. In the world of digital transactions, where tangible cash does not exchange hands, cryptocurrency trust becomes a linchpin ensuring the smooth transition from traditional to digital currencies.

Theoretical implications

The evolution of technology, especially in the realm of financial systems, necessitates a continuous reassessment and refinement of existing theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Cryptocurrencies, with their transformative potential and inherent complexities, present an opportune context for examining the adaptability and relevance of established theories. Against this backdrop, our exploration into the application and extension of TAM for understanding cryptocurrency adoption stands as a testimony to the model’s versatility and the necessity for its evolution in line with contemporary technological challenges. Delving deeper into the findings, several pivotal theoretical implications emerge, which are expounded upon below.

Extending TAM to cryptocurrencies

Since its inception, TAM has served as a linchpin in understanding technology acceptance across various domains (Lim, 2018 ). In expanding TAM’s purview to include cryptocurrencies, this study embarks on uncharted theoretical territory. The implications of this extension are manifold. Firstly, it attests to the dynamism and versatility of TAM as a model, proving its applicability even in contexts as nascent and volatile as cryptocurrency. Secondly, it allows for a structured analysis of an area that, despite its growing relevance, remains under-theorized. By providing a structured lens, the extended TAM offers a blueprint for future researchers to further investigate and understand the nuances of cryptocurrency adoption.

Incorporation of awareness in TAM

Awareness, as highlighted by this study, is not merely an ancillary factor but a core determinant in the adoption process, especially for emergent technologies like cryptocurrency. While traditional TAM constructs acknowledge the importance of prior experience (Shahzad et al., 2018 ), the explicit introduction of awareness propels it to the forefront of technology acceptance discussions. This enhancement suggests that for newer technologies, a foundational level of knowledge or awareness might be a pre-requisite before users can even begin to gauge the ease of use or usefulness. This research’s emphasis on awareness invites future theoretical explorations on how awareness is cultivated, its potential barriers, and its progressive influence on user acceptance as technologies evolve.

Introduction of trust in TAM

Trust, particularly in financial domains, is a multifaceted construct that encompasses cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. By weaving trust into the fabric of TAM as a moderating entity, this study illuminates the complexities between logic-driven usability concerns and emotionally charged trust issues. Recognizing trust as a moderator showcases the intricate balance consumers must strike when considering the adoption of financial technologies: while they may perceive cryptocurrencies as easy to use or useful, trust or lack thereof can significantly skew these perceptions and consequent behaviors. This enriched understanding of trust’s moderating role invites deeper dives into the nuances of trust—how it is established, maintained, and potentially restored—in the context of the technology adoption of cryptocurrency.

Responding to scholarly calls

Academic discourse thrives on the interconnectedness of scholarly pursuits. By heeding the calls of Kumar et al. ( 2021 ) and others, this study stands as a testament to the collaborative nature of academic advancement. Addressing gaps identified by predecessors not only strengthens the study’s relevance but also positions it as a responsive piece of scholarly work. It also sets the stage for potential reciprocal advancements, as future researchers might build upon these findings, leading to an iterative and collaborative expansion of knowledge in the domain, in this case, cryptocurrency.

Theoretical generalizability and extension

As Lim ( 2018 ) emphasized, the true strength of a theory lies not just in its foundational tenets but also in its adaptability to new contexts and challenges. By demonstrating TAM’s applicability in the cryptocurrency arena and further enhancing it with new constructs, this study magnifies the theory’s robustness. This act of both generalizing and extending underscores the importance of continually revisiting and refining theoretical models, ensuring they remain relevant and reflective of evolving technological landscapes.

Practical implications

The findings of this research, while deeply embedded in academic exploration, carry profound implications for real-world applications, especially for policymakers, financial institutions, and technology developers. As the digital world becomes increasingly intertwined with daily life, understanding the determinants that shape the adoption of emerging financial technologies such as cryptocurrencies is of paramount importance.

Nurturing cryptocurrency awareness

Our study emphasizes the centrality of awareness in the adoption process. For policymakers and institutions keen on promoting cryptocurrencies, it becomes imperative to first ensure that the general populace has a foundational understanding of what these digital currencies entail. This does not just mean superficial knowledge but a deeper comprehension of how cryptocurrencies work, their benefits, potential risks, and the broader implications for the financial landscape. Financial institutions, educational institutions, and governments can collaborate to create awareness campaigns, host workshops, or develop educational modules tailored to different demographic groups. Such initiatives can demystify the concept of cryptocurrencies and potentially accelerate their mainstream acceptance.

Strengthening trust in cryptocurrency

The inherent nature of cryptocurrency, with its foundation in cryptographic algorithms and blockchain technology, already provides a level of security and transparency that is unparalleled in many traditional financial systems. Blockchain’s decentralized and immutable ledger ensures that transactions are transparent and resistant to tampering. However, trust in cryptocurrency goes beyond the mere technological facets.

To begin, while blockchain and cryptography form the core of the technology, the platforms, wallets, exchanges, and interfaces that users interact with are not infallible. These can be susceptible to hacking, mismanagement, or fraudulent schemes, as has been evidenced by numerous high-profile cryptocurrency thefts and exchange failures. To address these concerns, tech developers and financial institutions should continuously invest in enhancing the security of these peripheral platforms. This can include multi-factor authentication, cold storage solutions, and regular security audits.

Next, for many potential adopters, the complex technicalities of blockchain and cryptography can be overwhelming. They might not fully grasp the intricacies of how these technologies bolster security, leading to hesitations in adoption. To mitigate this, there is a need for transparent communication that demystifies these concepts for the average user. Educational initiatives that simplify and explain the technological underpinnings can foster trust among users who might be on the fence due to a lack of understanding.

Lastly, the regulatory landscape plays a pivotal role in shaping trust. In the absence of clear regulatory guidelines, the cryptocurrency market can become a wild west of sorts, with potential risks for investors and users. Policymakers can help cultivate trust by introducing balanced regulations that protect users without stifling innovation. This could involve setting standards for cryptocurrency exchanges, mandating transparency in initial coin offerings (ICOs), or establishing a legal framework for the resolution of disputes in the crypto domain.

Tailoring education and outreach initiatives

The interplay between awareness, ease of use, and usefulness suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach to cryptocurrency education might be suboptimal. Different demographic groups might have varied levels of technological proficiency and financial literacy. Policymakers and institutions should consider these nuances when designing outreach programs. For instance, younger demographics might be more receptive to digital workshops or mobile apps that educate about cryptocurrencies, while older groups might benefit from traditional seminars or literature.

Informed policy making

Our research equips policymakers with insights into the multifaceted factors that influence cryptocurrency adoption. With a nuanced understanding of the role of awareness and trust, governments can make informed decisions when crafting policies around cryptocurrency regulation. For example, by recognizing the importance of trust, policymakers might emphasize transparency and accountability in cryptocurrency transactions, mandating periodic audits or setting up regulatory bodies specifically for monitoring cryptocurrency-related activities.

In a rapidly evolving digital landscape, the role of cryptocurrencies has emerged as a significant paradigm shift in our understanding of finance and monetary transactions. This study, through its adoption and extension of TAM to the realm of cryptocurrency, has cast light upon the intricate dynamics underpinning the acceptance and adoption of such innovative financial technologies.

The findings suggest that awareness is a foundational element in the acceptance process. A heightened level of understanding substantially bolsters consumers’ perceptions regarding the ease of use and usefulness of cryptocurrencies. Noteworthily, the established constructs of ease of use and usefulness in TAM remain significant predictors for cryptocurrency adoption, emphasizing the robustness of the model even in novel contexts. More importantly, trust acts as a pivotal moderating variable. While the inherent cryptographic nature and blockchain foundations of cryptocurrency provide a baseline of trust, it is the additional psychological facets of confidence and reliability that influence adoption.

Theoretically, our findings serve as a testament to the generalizability and versatility of TAM, affirming its applicability even in complex, relatively nascent domains like cryptocurrency. By integrating the pivotal variables of awareness and trust into the model, this research has not only enriched TAM but has also provided a nuanced understanding of how individuals perceive, trust, and ultimately decide to use or abstain from using cryptocurrencies. Our study underscores that while technological advancements like cryptography and blockchain lay the groundwork, the human factors of awareness and trust become instrumental in the decision-making processes surrounding technology adoption in financial contexts.

Practically, our findings carry profound implications for policymakers, financial institutions, and tech developers. The recognition that awareness and trust are cardinal in driving cryptocurrency adoption means stakeholders have a roadmap for fostering a more inclusive and transparent digital financial ecosystem. Whether it is through comprehensive educational campaigns, fortified security measures, or sensible regulation, the path to bolstering public confidence and understanding in cryptocurrencies has been delineated.

As with all explorations, our study opens the doors to numerous avenues for future research. Questions regarding the long-term sustainability of cryptocurrencies, the evolving regulatory landscape, or the potential integration of other behavioral and societal factors into the adoption model all warrant further investigation. Additionally, as the world of cryptocurrency continues to evolve with the introduction of new technologies and platforms, continuous assessment of user acceptance and trust will be paramount.

Despite the important contributions this study offers, several limitations exist that provide avenues for future research endeavors to delve deeper into the underlying problem. One salient limitation is the focus on a demographic predominantly consisting of graduates, whose perspectives and lifestyles might differ considerably from those who are less educated. Their propensity to be more liberal, technologically advanced, and quicker to engage with novel concepts might influence their receptiveness to cryptocurrencies. Future studies could benefit from exploring different demographic variables and diverse population samples.

Another constraint is the geographical scope of the study. The data were predominantly drawn from respondents in Lahore, Pakistan. Expanding this to other prominent cities like Faisalabad, Multan, Islamabad, and Karachi could present a more comprehensive picture of cryptocurrency acceptance across different urban contexts in the country. Moreover, an international comparison of cryptocurrency adaptability, contrasting Pakistan with both developed and developing nations, might provide intriguing insights.

Furthermore, while this research has prioritized awareness as a central variable, there are other pertinent variables left uncharted. Aspects such as government support, societal influences, and even technological design could be examined within the framework of TAM in subsequent studies.

Moreover, it is important to note the specificity of the variables explored. This research primarily centered on adoption-centric variables of cryptocurrencies. Expansive variables, such as the long-term sustainability of cryptocurrencies and facets like Bitcoin mining, warrant examination in future research endeavors.

Last but not least, a procedural limitation arises from the methodology employed: data collection at a single point in time using an adapted questionnaire. It would be invaluable for future researchers to embrace a longitudinal research approach, which would lend robustness and ensure the consistency and validity of findings over time.

In closing, this study underscores the transformative potential of cryptocurrencies in reshaping our financial future. However, for this potential to be fully realized, understanding and addressing the intricacies of user awareness, acceptance, and adoption, as delineated in this research, will be pivotal. We remain hopeful that our findings will serve as a cornerstone for both academic and practical endeavors in the realm of cryptocurrency, propelling us towards a more inclusive, transparent, and trustworthy digital financial landscape.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be made available by the corresponding author(s) upon reasonable request.

Abdul-Rahim R, Bohari SA, Aman A, Awang Z (2022) Benefit–risk perceptions of fintech adoption for sustainability from bank consumers’ perspective: the moderating role of fear of COVID-19. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148357

Aboalsamh HM, Khrais LT, Albahussain SA (2023) Pioneering perception of green fintech in promoting sustainable digital services application within smart cities. Sustainability (Switz) 15(14):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411440

Article Google Scholar

Akther T, Nur T (2022) A model of factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: a synthesis of the theory of reasoned action, conspiracy theory belief, awareness, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. PLoS ONE 17(Jan):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261869

Article CAS Google Scholar

Albayati H, Kim SK, Rho JJ (2020) Accepting financial transactions using blockchain technology and cryptocurrency: a customer perspective approach. Technol Soc 62:101320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101320

Allen F, Gu X, Jagtiani J (2022) Fintech, cryptocurrencies, and CBDC: financial structural transformation in China. J Int Money Financ 124:102625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2022.102625

Almajali DA, Masa’Deh R, Dahalin ZMD (2022) Factors influencing the adoption of Cryptocurrency in Jordan: an application of the extended TRA model. Cogent Soc Sci 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2103901

Arpaci I, Bahari M (2023) A complementary SEM and deep ANN approach to predict the adoption of cryptocurrencies from the perspective of cybersecurity. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107678

Basuki R, Tarigan ZJH, Siagian H, Limanta LS, Setiawan D, Mochtar J (2022) The effects of perceived ease of use, usefulness, enjoyment and intention to use online platforms on behavioral intention in online movie watching during the pandemic era. Int J Data Netw Sci 6(1):253–262. https://doi.org/10.5267/J.IJDNS.2021.9.003

Bibi S (2023) Money in the time of crypto. Res Int Bus Financ 65:101964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.101964

Biswas A, Bhattacharya D, Kumar KA (2021) DeepFake detection using 3D-Xception net with discrete Fourier transformation. J Inf Syst Telecommun 9(35):161–168. https://doi.org/10.52547/jist.9.35.161

Chen L, Aklikokou AK (2020) Determinants of E-government Adoption: testing the mediating effects of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Int J Public Adm 43(10):850–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2019.1660989

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q: Manag Inf Syst 13(3):319–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Deebak BD, Memon FH, Dev K, Khowaja SA, Wang W, Qureshi NMF (2022) TAB-SAPP: a trust-aware blockchain-based seamless authentication for massive IoT-enabled industrial applications. IEEE Trans Ind Inform 19(1):243–250. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3159164

Entrialgo M (2017) Are the intentions to entrepreneurship of men and women shaped differently? The impact of entrepreneurial role-model exposure and entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Res J 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2017-0013

Fagan M, Kilmon C, Pandey V (2012) Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation: The role of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and personal innovativeness. Campus-Wide Inf Syst 29(2):117–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741211212368

Farrukh M, Xu S, Baheer R, Ahmad W (2023) Unveiling the role of supply chain parameters approved by blockchain technology towards firm performance through trust: the moderating role of government support. Heliyon 9(11):e21831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21831

Farrukh M, Xu S, Naveed W, Nusrat S (2023) Investigating the impact of artificial intelligence on human resource functions in the health sector of China: a mediated moderation model. Heliyon 9(11):e21818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21818

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gaikwad A, Mavale S (2021) The impact of cryptocurrency adoption as a legal tender in El salvador. Int J Eng Manag Res 11(6):112–115. https://doi.org/10.31033/ijemr.11.6.16

Galariotis E, Karagiannis K (2020) Cultural dimensions, economic policy uncertainty, and momentum investing: international evidence. Eur J Financ 0(0):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2020.1782959

Gong Y, Tang X, Chang EC (2023) Group norms and policy norms trigger different autonomous motivations for Chinese investors in cryptocurrency investment. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01870-0

Granić A, Marangunić N (2019) Technology acceptance model in educational context: a systematic literature review. Br J Educ Technol 50(5):2572–2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12864

Gupta K, Arora N (2020) Investigating consumer intention to accept mobile payment systems through unified theory of acceptance model: an Indian perspective. South Asian J Bus Stud 9(1):88–114. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-03-2019-0037

Hasan R, Miah MD, Hassan MK (2022) The nexus between environmental and financial performance: Evidence from gulf cooperative council banks. Bus Strategy Environ 31(7):2882–2907. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3053

Hasan SZ, Ayub H, Ellahi A, Saleem M (2022) A moderated mediation model of factors influencing intention to adopt cryptocurrency among university students. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2022:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9718920

Hasgül E, Karataş M, Pak Güre MD, Duyan V (2023) A perspective from Turkey on construction of the new digital world: analysis of emotions and future expectations regarding Metaverse on Twitter. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01958-7

Howson P, de Vries A (2022) Preying on the poor? Opportunities and challenges for tackling the social and environmental threats of cryptocurrencies for vulnerable and low-income communities. Energy Res Soc Sci 84(Aug):102394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102394

Jalan A, Matkovskyy R, Urquhart A, Yarovaya L (2023) The role of interpersonal trust in cryptocurrency adoption. J Int Financ Mark, Inst Money 83(Dec):101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2022.101715

Johar S, Ahmad N, Asher W, Cruickshank H, Durrani A (2021) Research and applied perspective to blockchain technology: a comprehensive survey. Appl Sci 11(14):6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11146252

Kakinaka S, Umeno K (2022) Cryptocurrency market efficiency in short- and long-term horizons during COVID-19: An asymmetric multifractal analysis approach. Financ Res Lett 46(PA):102319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102319

Khan MZ, Ali Y, Sultan HBin, Hasan M, Baloch S (2020) Future of currency: a comparison between traditional, digital fiat and cryptocurrency exchange mediums. Int J Blockchain Cryptocurrencies 1(2):206. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbc.2020.109003

Kher R, Terjesen S, Liu C (2021) Blockchain, Bitcoin, and ICOs: a review and research agenda. Small Bus Econ 56(4):1699–1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00286-y

Kim J, Merrill K, Collins C (2021) AI as a friend or assistant: the mediating role of perceived usefulness in social AI vs. functional AI. Telemat Inform 64(Aug):101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101694

Kumar S, Lim WM, Pandey N, Westland JC (2021) 20 years of electronic commerce research. In: Electronic Commerce Research (vol. 21, Issue 1). Springer, USA

Kumar S, Lim WM, Sivarajah U, Kaur J (2023) Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Integration in Business: Trends from A Bibliometric-content Analysis. Inf Syst Front 871–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10279-0

Li C, Khaliq N, Chinove L, Khaliq U, Popp J, Oláh J (2023) Cryptocurrency acceptance model to analyze consumers’ usage intention: evidence from Pakistan. SAGE Open 13(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231156360

Li J (2023) Predicting the demand for central bank digital currency: a structural analysis with survey data. J Monetary Econ 134:73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2022.11.007

Lim WM (2018). Dialectic antidotes to critics of the technology acceptance model: conceptual, methodological, and replication treatments for behavioural modelling in technology-mediated environments. 22, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v22i0.1651

Lu A, Deng R, Huang Y, Song T, Shen Y, Fan Z, Zhang J (2022) The roles of mobile app perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in app-based Chinese and English learning flow and satisfaction. Educ Inf Technol 27(7):10349–10370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11036-1

Martins JM, Shahzad MF, Javed I (2023) Assessing the impact of workplace harassment on turnover intention. Evid Bank Ind 7(5):1699–1722. https://doi.org/10.28991/ESJ-2023-07-05-016

Martins JM, Muhammad FS, Shuo X (2023) Examining the factors influencing entrepreneurial intention to initiate new ventures: Focusing on knowledge of entrepreneurial skills, ability to take risk and entrepreneurial innovativeness in open innovation business model. Res Sq 1125–1146. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2664778/v1

Martins JM, Shahzad MF, Xu S (2023) Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention to initiate new ventures: evidence from university students. J Innov Entrep. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-023-00333-9

Matemba ED, Li G (2018) Technology in society consumers ’ willingness to adopt and use WeChat wallet: an empirical study in South Africa. Technol Soc 53:55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.12.001

McCloskey DW (2006) The importance of ease of use, usefulness, and trust to online consumers: An examination of the technology acceptance model with older customers. J Organ End Use Comput (JOEUC) 18(3):47–65. https://doi.org/10.4018/joeuc.2006070103

Mizanur RM, Sloan TR (2017) User adoption of mobile commerce in Bangladesh: Integrating perceived risk, perceived cost and personal awareness with TAM. Int Technol Manag Rev 103–124. https://doi.org/10.2991/itmr.2017.6.3.4

Nadeem MA, Liu Z, Pitafi AH, Younis A, Xu Y (2021) Investigating the adoption factors of cryptocurrencies—a case of Bitcoin: empirical evidence from China. SAGE Open 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244021998704

Namahoot KS, Rattanawiboonsom V (2022) Integration of TAM model of consumers’ intention to adopt cryptocurrency platform in Thailand: the mediating role of attitude and perceived risk. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9642998

Parate S, Josyula HP, Reddi LT (2023) Digital identity verification: transforming KYC processes in banking through advanced technology and enhanced security measures. Int Res J Mod Eng Technol Sci 09:128–137. https://doi.org/10.56726/irjmets44476

Quan W, Moon H, Kim S (Sam), Han H(2023) Mobile, traditional, and cryptocurrency payments influence consumer trust, attitude, and destination choice: Chinese versus Koreans Int J Hospit Manag 108(Oct):103363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103363

Rejeb A, Rejeb K, Alnabulsi K, Zailani S (2023) Tracing knowledge diffusion trajectories in scholarly Bitcoin research: co-word and main path analyses. J Risk Financ Manag 16(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16080355

Roscoe AM, Lang D, Sheth JN (1975) Follow-up methods, questionnaire length, and market differences in mail surveys. J Mark 39(2):20. https://doi.org/10.2307/1250111

Sagheer N, Khan KI, Fahd S, Mahmood S, Rashid T, Jamil H (2022). Factors affecting adaptability of cryptocurrency: an application of technology acceptance model. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903473

Sahoo S, Kumar S, Sivarajah U, Lim WM, Westland JC, Kumar A (2022). Blockchain for sustainable supply chain management: trends and ways forward. In: Electronic Commerce Research (Issue 0123456789). Springer, USA

Salas A (2020) Literature review of faculty-perceived usefulness of instructional technology in classroom dynamics. Contemp Educ Technol 7(2):174–186. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/6170

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF (2014) PLS-SEM: looking back and moving forward. Long Range Plan 47(3):132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2014.02.008

Schaupp LC, Festa M (2018) Cryptocurrency adoption and the road to regulation. Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3209281.3209336

Shahzad F, Shahzad MF, Dilanchiev A, Irfan M (2022) Modeling the influence of paternalistic leadership and personality characteristics on alienation and organizational culture in the aviation industry of Pakistan: the mediating role of cohesiveness. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215473

Shahzad F, Xiu GY, Wang J, Shahbaz M (2018) An empirical investigation on the adoption of cryptocurrencies among the people of mainland China. Technol Soc 55(Jan):33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.05.006

Shahzad MF, Khan KI, Saleem S, Rashid T (2021) What factors affect the entrepreneurial intention to start-ups? The role of entrepreneurial skills, propensity to take risks, and innovativeness in open business models. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7030173

Shahzad MF, Xu S, Khan KI, Hasnain MF (2023) Effect of social influence, environmental awareness, and safety affordance on actual use of 5G technologies among Chinese students. Sci Rep 0123456789, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50078-4

Shahzad MF, Xu S, Rehman O, Javed I (2023) Impact of gamification on green consumption behavior integrating technological awareness, motivation, enjoyment and virtual CSR. Sci Rep 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48835-6

Shin D, Rice J (2022) Cryptocurrency: a panacea for economic growth and sustainability? A critical review of crypto innovation. Telemat Inform 71(Apr):101830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2022.101830

Siagian H, Tarigan ZJH, Basana SR, Basuki R (2022) The effect of perceived security, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness on consumer behavioral intention through trust in digital payment platform. Int J Data Netw Sci 6(3):861–874. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2022.2.010

Siska E (2023) Digital bank financial soundness analysis at PT Bank Jago Tbk. CAMEL Framew Approach 3(3):527–532. https://doi.org/10.47065/arbitrase.v3i3.700

Stocklmayer S, Gilbert JK (2002) New experiences and old knowledge: Towards a model for the personal awareness of science and technology. Int J Sci Educ 24(8):835–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690210126775

Sudzina F, Dobes M, Pavlicek A (2023) Towards the psychological profile of cryptocurrency early adopters: Overconfidence and self-control as predictors of cryptocurrency use. Curr Psychol 42(11):8713–8717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02225-1

Sukumaran S, Bee TS, Wasiuzzaman S (2022) Cryptocurrency as an investment: the Malaysian Context. Risks 10(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/risks10040086

Tan TM, Saraniemi S (2022) Trust in blockchain-enabled exchanges: future directions in blockchain marketing. J Acad Market Sci 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-022-00889-0

Tandon C, Revankar S, Parihar SS (2021) How can we predict the impact of the social media messages on the value of cryptocurrency? Insights from big data analytics. Int J Inf Manag Data Insights 1(2):100035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100035

Tauni MZ, Fang HX, Rao ZuR, Yousaf S (2015) The influence of Investor personality traits on information acquisition and trading behavior: evidence from Chinese futures exchange. Personal Individ Differ 87(Aug):248–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.026

Theiri S, Nekhili R, Sultan J (2022) Cryptocurrency liquidity during the Russia–Ukraine war: the case of Bitcoin and Ethereum. J Risk Financ 24(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-05-2022-0103

Treiblmaier H, Sillaber C (2021) The impact of blockchain on e-commerce: a framework for salient research topics. Electron Commer Res Appl 48(Apr):101054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2021.101054

Uematsu Y, Tanaka S (2019) High‐dimensional macroeconomic forecasting and variable selection via penalized regression. Econ J 22(1):34–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ectj.12117

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Utz M, Johanning S, Roth T, Bruckner T, Strüker J (2022) From ambivalence to trust: using blockchain in customer loyalty programs. Int J Inf Manag 68(Mar):102496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102496

Völter F, Urbach N, Padget J (2021) Trusting the trust machine: evaluating trust signals of blockchain applications. Int J Inf Manag 68(Sept). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102429

Voorhees CM, Brady MK, Calantone R, Ramirez E (2016) Discriminant validity testing in marketing: an analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J Acad Mark Sci 44(1):119–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0455-4

Wibasuri A (2022) Exploring the impact of relevant factors on the acceptance of cryptocurrency mobile apps: an extended technology acceptance model (TAM-3). 6(June). https://doi.org/10.29099/ijair.v6i1.1.971

Yayla A, Dincelli E, Parameswaran S (2023) A mining town in a digital land: browser-based cryptocurrency mining as an alternative to online advertising. Inf Syst Front 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-023-10386-6

Yuen KF, Cai L, Qi G, Wang X (2021) Factors influencing autonomous vehicle adoption: an application of the technology acceptance model and innovation diffusion theory. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 33(5):505–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1826423

Zafar S, Riaz S, Mahmood W (2021). Conducting the cashless revolution in Pakistan using enterprise integration. August, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijeme.2021.04.02

Zou Z, Liu X, Wang M, Yang X (2023) Insight into digital finance and fintech: a bibliometric and content analysis. Technol Soc 73(Oct):102221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102221

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant numbers 72074014 and 72174016.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China

Muhammad Farrukh Shahzad & Shuo Xu

Sunway Business School, Sunway University, Sunway, Selangor, Malaysia

Weng Marc Lim

School of Business, Law and Entrepreneurship, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia

Faculty of Business, Design and Arts, Swinburne University of Technology, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

Department of Chemistry, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

Muhammad Faisal Hasnain

College of Environment and Life Science, Beijing University of Technology, 100124, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Shahneela Nusrat

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization of study, data analysis, and original draft preparation, MFS; Preparation of data file, interpretation, results, and discussion, SN and MFH; Supervision, reviewing, and editing, WML; Project administration, and resource management, SX and MFS; Funding, SX. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author