An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

China’s one child family policy

Ching y choi.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: P Kane.

China’s one child family policy, which was first announced in 1979, has remained in place despite the extraordinary political and social changes that have occurred over the past two decades. It emerged from the belief that development would be compromised by rapid population growth and that the sheer size of China’s population together with its young age structure presented a unique challenge.

Summary points

The one child family policy was developed and implemented in response to concerns about the social and economic consequences of continued rapid population growth

Implementation was more successful in urban areas than rural areas

Social and economic reforms have made rigorous implementation of the policy more difficult

The main criticism of the policy is its stimulus to discrimination against females, who may be aborted, abandoned, or unregistered

The policy has eased some of the pressures of rapid population increase on communities, reducing the population by at least 250 million

This article is based on experience from frequent field visits to China over the past 25 years and the authors’ collections of relevant Chinese and Western documents from the 1950s onwards. We also used references from the major demographic journals.

Population growth since 1953

Government family planning services became available as a contribution to maternal and child health in China from 1953. As the result of falling death rates, the population growth rate rose to 2.8%, leading to some 250 million additional people by 1970. After a century of rebellions, wars, epidemics, and the collapse of imperial authority, during which the annual population growth was probably no more than 0.3%, such an expansion was initially seen as part of China’s new strength. Mao Zedong quoted a traditional saying: “Of all things in the world, people are the most precious.” 1

Rapid growth, however, put considerable strain on the government’s efforts to meet the needs of its people. The fourth five year plan in 1970 included, for the first time, targets for population growth rate. Contraceptive and abortion services were extended into the rural areas, and there was extensive promotion of later marriage, longer intervals between births, and smaller families.

Within five years the population growth rate fell to around 1.8%, and the target set for 1980 was a growth rate of 1%. To achieve this, each administrative unit introduced its own target and discussed and, when necessary, attempted to modify its population’s fertility behaviour. At local level, collective incomes and allocation of funds—for health care, welfare, and schools, for example—made it possible for couples to understand the effect of their personal family choices on the community. They also made it possible for the community to exercise pressure on those who wished to have children outside the agreed plans.

Origins of one child policy

But even the 1980 target, let alone the more ambitious aim of reaching zero growth by the year 2000, was unattainable through a “later, longer, fewer” campaign. Population studies had been discontinued in China in the late 1950s in line with Marxist doctrine. Only in 1975 did new university departments begin to be established, staffed largely by statisticians. They quickly realised that with half of the population under the age of 21, further growth was inevitable even if each family was quite small. 2 By the time of the 1982 census there were already more than 1 billion people in China, and if current trends persisted, there could be 1.4 billion by the end of the century. Most population growth rate targets were abandoned in the early 1980s, and from 1985 the official goal was to keep the population at around 1.2 billion by 2000. 3

Elements of the policy

Details of what the one child policy involved and how it was to be implemented have varied at different times. 4 The essential elements are clear. The aim was to curtail population growth, perhaps to 1.1 billion and certainly to 1.2 billion, by the year 2000. It was hoped that third and higher order births could be eliminated and that about 30% of couples might agree to forgo a second child. The ideal of a one child family implied that the majority would probably never meet it. It was argued that the sacrifice of second or third children was necessary for the sake of future generations. People were to be encouraged to have only one child through a package of financial and other incentives, such as preferential access to housing, schools, and health services. Discouragement of larger families included financial levies on each additional child and sanctions which ranged from social pressure to curtailed career prospects for those in government jobs. Specific measures varied from province to province. 5 Minorities were excluded from the policy.

Early implementation

In some of the largest and most advanced cities like Shanghai, sizeable proportions of couples already chose to have only one child. Both adults worked full time with long hours; the housing allocation was only 3.6 m 2 per person in 1977; without conveniences such as refrigerators tasks like shopping and cooking were time consuming daily efforts. In most families, at least one member would be employed in the state sector and susceptible to government direction. As a result, it was not long before 90% of couples in urban areas were persuaded to restrict their families to a single child.

Rural families, however, were more difficult to convince. Peasants with limited savings and without pensions needed children to support them in old age. As married daughters moved into their husbands’ families, a son was essential—and preferably more than one. Infant mortality had fallen greatly, but in 1980 it was still around 53 per 1000 live births nationally and higher than that in rural areas. 6

Years of political upheaval had left many peasants cynical about government policies and their likely duration; it also left them adept at avoiding unpopular prescriptions. Local authorities were forced to rely on fines for higher order births. They also turned to stringent birth control campaigns, which in the policy’s earlier years resulted in considerable numbers of women being bullied into abortions and sterilisation. Village level family planning workers were caught between the state’s demands and the determination of their friends and neighbours. Gradually villagers developed a process of negotiation and compromise 7 which allowed a degree of flexibility within the policy. As a result, irrespective of the particular directives at any given time, the proportion of women with one child who went on to have a second (almost universal behaviour in the late 1970s) fell only to 90% by 1990. 8

Effect of reform process on implementation

The economic reforms of recent years in China had many—often unintended—consequences for the one child family policy. Possibly the most important has been the growth of internal migration. Tight restrictions on movement, especially rural-urban movement, were relaxed as the demand for labour in the towns and cities grew. Government efforts to regulate the migrants, or even to identify their numbers, have been only partially successful. Recent estimates suggest that up to 150 million Chinese—most of them adults in their 20s and 30s—form a floating population who leave their villages for longer or shorter periods. 9 Earning cash wages, living in makeshift accommodation, moving between jobs and between cities and their home villages, these people are seldom eligible for state provided services and see no reason to draw official attention through temporary registration.

One result has been declines in the reliability of population statistics, already compromised by the reluctance of family planning workers to admit their inability to achieve the results demanded of them. In 1991-2, perhaps a quarter of all births were missed. 10 As a result, although China’s official total fertility rate for 1990-5 was 1.92 children, 11 it may be more realistic to assume total fertility around the replacement level—that is, a little over two children per couple.

Although both male and female births are underreported, the birth of a girl is twice as likely to be ignored. 12 Underreporting is believed to account for about half to two thirds of the difference in infant sex ratios, which by the early 1990s had risen to 114 boys for every 100 girls. Unrecorded daughters may be left with relatives, adopted out, or abandoned to orphanages, 13 which are increasingly unable to cope with the influx. Sex ratios are further skewed by widespread abortion, after the illegal but lucrative use of ultrasound to identify fetal sex.

In many rural areas rising incomes make it possible to see the fine for an additional child as a feasible investment strategy. At the same time peasants are increasingly saving for old age through a variety of retirement schemes, some offered through non-government family planning associations. These family planning associations, besides promoting family planning and the one child policy, offer various social welfare benefits including training and income generating loans for rural women and basic maternal and child health screening and care. 14

The introduction of fees for health services has had severe consequences for poorer peasants, and many women are unable to access reproductive health services, including maternity care or even follow up for contraceptive problems. One recent provincial survey found that over 70% of diagnosed women in a random sample had at least one reproductive tract infection. 15

A long standing challenge to effective family planning had been the poor quality and limited choice of contraceptives, especially in rural areas reliant largely on intrauterine devices and sterilisation. With support from international agencies, especially the UN Population Fund, quality has been improved (manufacture of the unreliable steel ring intrauterine device ceased in 1994). A wider range of methods is becoming available, and despite the extra cost to the individual they are proving popular.

Urban dependence on the state for employment, housing, education, and other benefits, which facilitated compliance with the one child policy, is being progressively reduced. However, although some in lucrative private work may choose to ignore the policy, for most people the increased costs and greater insecurity which they now face probably contribute to caution in family building. Instead, incomes are channelled into buying better health care and education for the sole child and providing the desirable brand name toys and clothes now available. Concerns over spoilt “little emperors” are widespread, and some family planning associations now run parent education classes to counter parents’ overprotective behaviour.

Outcomes of one child policy

The one child policy has unquestionably imposed great costs on individuals, even if (as has been suggested 16 ) these costs have to be seen in the context of a Chinese tradition in which demographic decisions have never been individual. Most Chinese people seem prepared to make such a sacrifice if the pain is generally shared. 17 , 18 In 1993, the family planning associations were officially given a supervisory role in monitoring coercion and other abuses in implementing the policy. The complaints they receive almost invariably relate to unfair favourable treatment of cadres or other favoured individuals.

The main criticism of the policy, though, is undoubtedly its stimulus to sex discrimination. Faced with hard choices about overall numbers, the Chinese girl child has once again become expendable. Too many girls, if not aborted, face orphanages or second class lives concealed from the world and with reduced chances of schooling and health care. China has one of the world’s highest rates of suicide of women in the reproductive years. 19 Increased pressure to produce the desired child, and a perceived reduction in the value of females, can only have exacerbated the problems of rural women.

At the same time, the successes of the policy should not be underrated. In the context of rising costs and rising aspirations throughout China, there is increasing recognition among the four fifths of the population that is rural of the burden to the family of having a third child, and some are even willing to avoid a second. 20 Moreover, since its inception reductions in Chinese fertility have reduced the country’s (and the world’s) population growth by some 250 million. These reductions in fertility have eased at least some of the pressures on communities, state, and the environment in a country which still carries one fifth of the world’s people.

HARBIN: HEILONGJIANG SCIENTIFIC TECHNOLOGY PUBLISHING

From A Collection of Cartoons on Marriage and Children (Hun yu bai tai man hua ji) by NING Changhui, 1989.

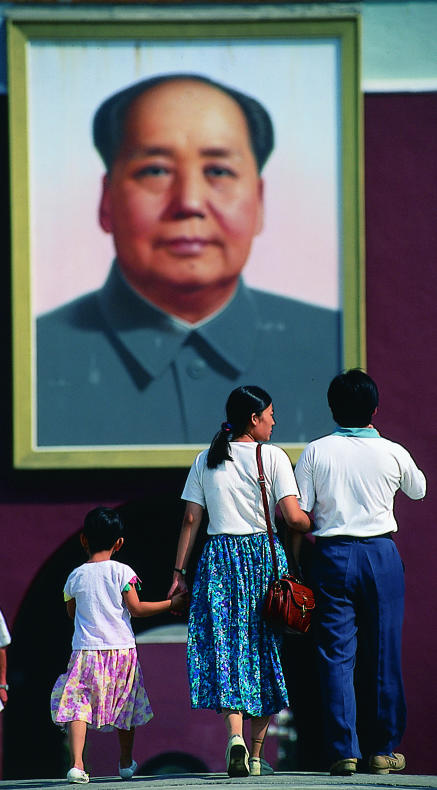

CHRIS STOWERS/PANOS PICTURES

One is ideal, said Mao

- 1. Kane P. The second billion: population and family planning in China. Ringwood: Penguin Books; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Liu Z. Population theory in China [ Tien HY, translator and editor]. New York: Croom Helm; 1980. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hao Y. China’s 1.2 billion population target for the year 2000: “within” or “beyond”? Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs. 1988;19/20:165–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Hull T. Recent population policy in China. Canberra: Australian International Development Assistance Bureau; 1991. (Development paper 2.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Feng G, Hao L. A summary of family planning regulations for 28 regions in China [in Chinese] Pop Res. 1992;4:28–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Banister J. China’s changing population. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Greenhalgh S. Negotiating birth control in village China. New York: Population Council; 1992. (Working paper 38.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Feeney G, Wang F. Parity progression and birth intervals in China. Pop Dev Rev. 1993;19:61–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Scharping T, editor. . Floating population and migration in China: the impact of economic reforms. Hamburg: Mittelungen des Instituts fur Asienkunde; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Zeng Y. Is fertility in China in 1992 far below replacement level? Pop Stud. 1996;50:27–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. United Nations. World population monitoring 1997. New York: United Nations; 1998. (ST/ESA/Ser.A/169.) [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Zeng Y, Tu P, Gu B, Xu Y, Li B, Li Y. Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratios at birth in China. Pop Dev Rev. 1993;19:283–302. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Johnson K. Chinese orphanages: saving China’s abandoned girls. Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs. 1993;30:61–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Kane P. The China handbook: regional handbooks of economic development: prospects into the 21st century. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn; 1997. Population policy. In Hudson C, ed. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Kaufman J, Zhang K, Fang J. Reproductive health financing, service availability and needs in rural China. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin. 1997;28:61–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Lee J, Wang F. Malthusian models and Chinese realities: China’s demographic system 1700-2000. Pop Dev Rev. 1999;25:33–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00033.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Milwertz CN. Accepting population control: urban Chinese women and the one-child family policy. Richmond: Curzon Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kane P. Population and family policies. In: Benewick R, Wingrove P, editors. China in the 1990s. Basingstoke: MacMillan; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Ruzicka L. Suicide in countries and areas of the ESCAP region. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1998;13:55–74. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Greenhalgh S, Zhu C, Li N. Restraining population growth in three Chinese villages. Pop Dev Rev. 1994;20:365–396. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (202.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES