- An Ordinary Man, His Extraordinary Journey

- Hours/Admission

- Nearby Dining and Lodging

- Information

- Library Collections

- Online Collections

- Photographs

- Harry S. Truman Papers

- Federal Records

- Personal Papers

- Appointment Calendar

- Audiovisual Materials Collection

- President Harry S. Truman's Cabinet

- President Harry S. Truman's White House Staff

- Researching Our Holdings

- Collection Policy and Donating Materials

- Truman Family Genealogy

- To Secure These Rights

- Freedom to Serve

- Events and Programs

- Featured programs

- Civics for All of US

- Civil Rights Teacher Workshop

- High School Trivia Contest

- Teacher Lesson Plans

- Truman Library Teacher Conference 2024

- National History Day

- Student Resources

- Truman Library Teachers Conference

- Truman Presidential Inquiries

- Student Research File

- The Truman Footlocker Project

- Truman Trivia

- The White House Decision Center

- Three Branches of Government

- Electing Our Presidents Teacher Workshop

- National History Day Workshops from the National Archives

- Research grants

- Truman Library History

- Contact Staff

- Volunteer Program

- Internships

- Harry S. Truman

- Educational Resources

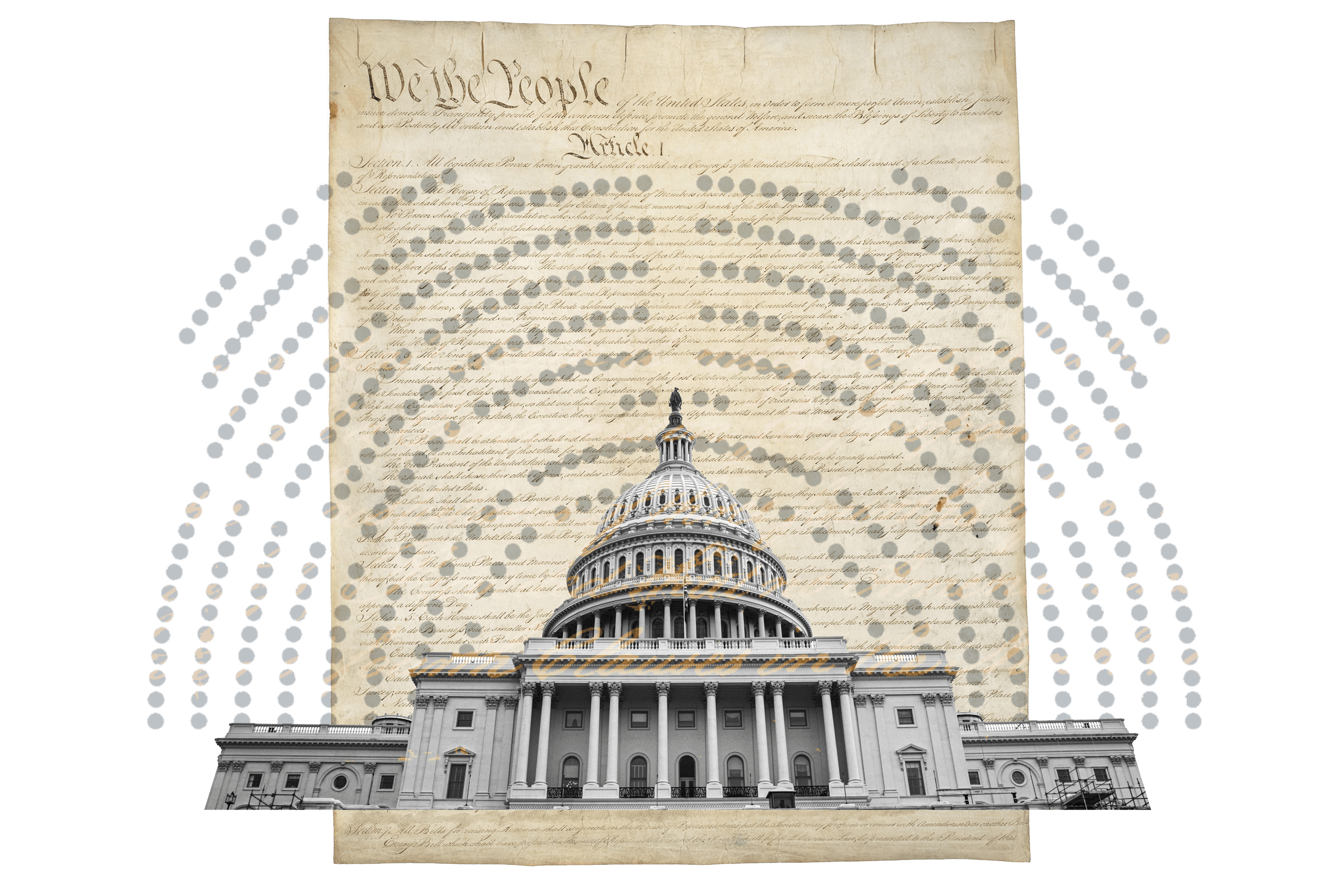

The Amendment Process

Adding a New Amendment to the United States Constitution

Not an Easy Task!

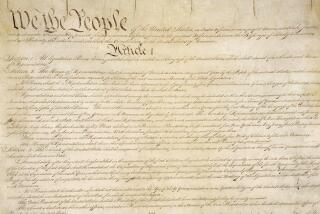

The United States Constitution was written "to endure for ages to come" Chief Justice John Marshall wrote in the early 1800s. To ensure it would last, the framers made amending the document a difficult task. That difficulty was obvious recently when supporters of congressional term limits and a balanced budget amendment were not successful in getting the new amendments they wanted.

The Constitution has been amended only 27 times since it was drafted in 1787, including the first 10 amendments adopted four years later as the Bill of Rights.

Not just any idea to improve America deserves an amendment. The idea must be one of major impact affecting all Americans or securing rights of citizens.

Recently, an amendment to outlaw flag burning may be gathering steam and President Clinton has endorsed the idea of a crime victims' rights amendment. Other amendment proposals that are popular with some congressional leaders would allow voluntary school prayer, make English the country's official language, and abolish the Electoral College.

Among amendments adopted this century are those that gave women the right to vote; enacted and repealed Prohibition; abolished poll taxes; and lowered the minimum voting age from 21 to 18.

The amendment process is very difficult and time consuming: A proposed amendment must be passed by two-thirds of both houses of Congress, then ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the states. The ERA Amendment did not pass the necessary majority of state legislatures in the 1980s. Another option to start the amendment process is that two-thirds of the state legislatures could ask Congress to call a Constitutional Convention.

A new Constitutional Convention has never happened, but the idea has its backers. A retired federal judge, Malcolm R. Wilkey, called a few years ago for a new convention. "The Constitution has been corrupted by the system which has led to gridlock, too much influence by interest groups, and members of Congress who focus excessively on getting reelected," Wilkey said in a published series of lectures.

But Richard C. Leone, president of the New York-based Twentieth Century Fund, a nonpartisan research group, says recent efforts to amend the Constitution go too far. "I think we're overreacting to some people's dissatisfaction with the government," Leone said. His organization hopes to balance the argument by publishing The New Federalist Papers, taking the name from the original Federalist Papers which were written to promote ratification of the Constitution.

Polsby, the Northwestern law professor, said the number of proposed amendments is not uncommon. But he agreed that political fixes do not necessarily belong in the Constitution - with Prohibition being the prime example.

Information Resource: Amendment Fever Grips Washington: by Laurie Asseo © Associated Press - edited for html by Robert Hedges

Office of the Federal Register (OFR)

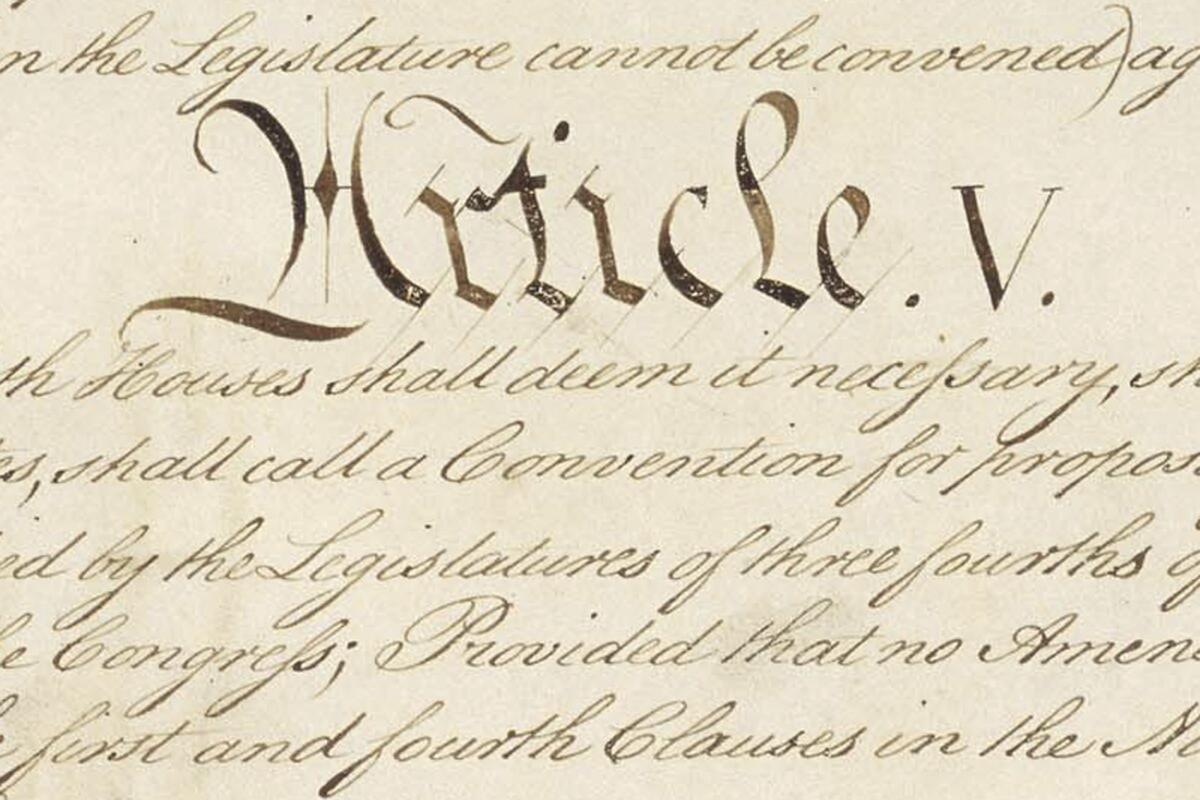

Constitutional Amendment Process

The authority to amend the Constitution of the United States is derived from Article V of the Constitution . After Congress proposes an amendment, the Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), is charged with responsibility for administering the ratification process under the provisions of 1 U.S.C. 106b . The Archivist has delegated many of the ministerial duties associated with this function to the Director of the Federal Register. Neither Article V of the Constitution nor section 106b describe the ratification process in detail. The Archivist and the Director of the Federal Register follow procedures and customs established by the Secretary of State, who performed these duties until 1950, and the Administrator of General Services, who served in this capacity until NARA assumed responsibility as an independent agency in 1985.

The Constitution provides that an amendment may be proposed either by the Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. None of the 27 amendments to the Constitution have been proposed by constitutional convention. The Congress proposes an amendment in the form of a joint resolution. Since the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, the joint resolution does not go to the White House for signature or approval. The original document is forwarded directly to NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for processing and publication. The OFR adds legislative history notes to the joint resolution and publishes it in slip law format. The OFR also assembles an information package for the States which includes formal "red-line" copies of the joint resolution, copies of the joint resolution in slip law format, and the statutory procedure for ratification under 1 U.S.C. 106b.

The Archivist submits the proposed amendment to the States for their consideration by sending a letter of notification to each Governor along with the informational material prepared by the OFR. The Governors then formally submit the amendment to their State legislatures or the state calls for a convention, depending on what Congress has specified. In the past, some State legislatures have not waited to receive official notice before taking action on a proposed amendment. When a State ratifies a proposed amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy of the State action, which is immediately conveyed to the Director of the Federal Register. The OFR examines ratification documents for facial legal sufficiency and an authenticating signature. If the documents are found to be in good order, the Director acknowledges receipt and maintains custody of them. The OFR retains these documents until an amendment is adopted or fails, and then transfers the records to the National Archives for preservation.

A proposed amendment becomes part of the Constitution as soon as it is ratified by three-fourths of the States (38 of 50 States). When the OFR verifies that it has received the required number of authenticated ratification documents, it drafts a formal proclamation for the Archivist to certify that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large and serves as official notice to the Congress and to the Nation that the amendment process has been completed.

In a few instances, States have sent official documents to NARA to record the rejection of an amendment or the rescission of a prior ratification. The Archivist does not make any substantive determinations as to the validity of State ratification actions, but it has been established that the Archivist's certification of the facial legal sufficiency of ratification documents is final and conclusive.

In recent history, the signing of the certification has become a ceremonial function attended by various dignitaries, which may include the President. President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments as a witness, and President Nixon similarly witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment along with three young scholars. On May 18, 1992, the Archivist performed the duties of the certifying official for the first time to recognize the ratification of the 27th Amendment, and the Director of the Federal Register signed the certification as a witness.

Links to Constitutional Amendment Information in the Treasures of Congress Exhibit

- The Bill of Rights (Amendments 1-10 and 27)

- The 13th Amendment (Prohibiting Slavery)

- The 17th Amendment (Direct Election of Senators)

- The 19th Amendment (Granting Women the Right to Vote)

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Constitution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Constitution of the United States established America’s national government and fundamental laws, and guaranteed certain basic rights for its citizens.

It was signed on September 17, 1787, by delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Under America’s first governing document, the Articles of Confederation, the national government was weak and states operated like independent countries. At the 1787 convention, delegates devised a plan for a stronger federal government with three branches—executive, legislative and judicial—along with a system of checks and balances to ensure no single branch would have too much power.

The Preamble to the U.S. Constitution

The Preamble outlines the Constitution's purpose and guiding principles. It reads:

The Bill of Rights were 10 amendments guaranteeing basic individual protections, such as freedom of speech and religion, that became part of the Constitution in 1791. To date, there are 27 constitutional amendments.

Articles of Confederation

America’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation , was ratified in 1781, a time when the nation was a loose confederation of states, each operating like independent countries. The national government was comprised of a single legislature, the Congress of the Confederation; there was no president or judicial branch.

The Articles of Confederation gave Congress the power to govern foreign affairs, conduct war and regulate currency; however, in reality these powers were sharply limited because Congress had no authority to enforce its requests to the states for money or troops.

Did you know? George Washington was initially reluctant to attend the Constitutional Convention. Although he saw the need for a stronger national government, he was busy managing his estate at Mount Vernon, suffering from rheumatism and worried that the convention wouldn't be successful in achieving its goals.

Soon after America won its independence from Great Britain with its 1783 victory in the American Revolution , it became increasingly evident that the young republic needed a stronger central government in order to remain stable.

In 1786, Alexander Hamilton , a lawyer and politician from New York , called for a constitutional convention to discuss the matter. The Confederation Congress, which in February 1787 endorsed the idea, invited all 13 states to send delegates to a meeting in Philadelphia.

Forming a More Perfect Union

On May 25, 1787, the Constitutional Convention opened in Philadelphia at the Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence had been adopted 11 years earlier. There were 55 delegates in attendance, representing all 13 states except Rhode Island , which refused to send representatives because it did not want a powerful central government interfering in its economic business. George Washington , who’d become a national hero after leading the Continental Army to victory during the American Revolution, was selected as president of the convention by unanimous vote.

The delegates (who also became known as the “framers” of the Constitution) were a well-educated group that included merchants, farmers, bankers and lawyers. Many had served in the Continental Army, colonial legislatures or the Continental Congress (known as the Congress of the Confederation as of 1781). In terms of religious affiliation, most were Protestants. Eight delegates were signers of the Declaration of Independence, while six had signed the Articles of Confederation.

At age 81, Pennsylvania’s Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) was the oldest delegate, while the majority of the delegates were in their 30s and 40s. Political leaders not in attendance at the convention included Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and John Adams (1735-1826), who were serving as U.S. ambassadors in Europe. John Jay (1745-1829), Samuel Adams (1722-1803) and John Hancock (1737-93) were also absent from the convention. Virginia’s Patrick Henry (1736-99) was chosen to be a delegate but refused to attend the convention because he didn’t want to give the central government more power, fearing it would endanger the rights of states and individuals.

Reporters and other visitors were barred from the convention sessions, which were held in secret to avoid outside pressures. However, Virginia’s James Madison (1751-1836) kept a detailed account of what transpired behind closed doors. (In 1837, Madison’s widow Dolley sold some of his papers, including his notes from the convention debates, to the federal government for $30,000.)

Debating the Constitution

The delegates had been tasked by Congress with amending the Articles of Confederation; however, they soon began deliberating proposals for an entirely new form of government. After intensive debate, which continued throughout the summer of 1787 and at times threatened to derail the proceedings, they developed a plan that established three branches of national government–executive, legislative and judicial. A system of checks and balances was put into place so that no single branch would have too much authority. The specific powers and responsibilities of each branch were also laid out.

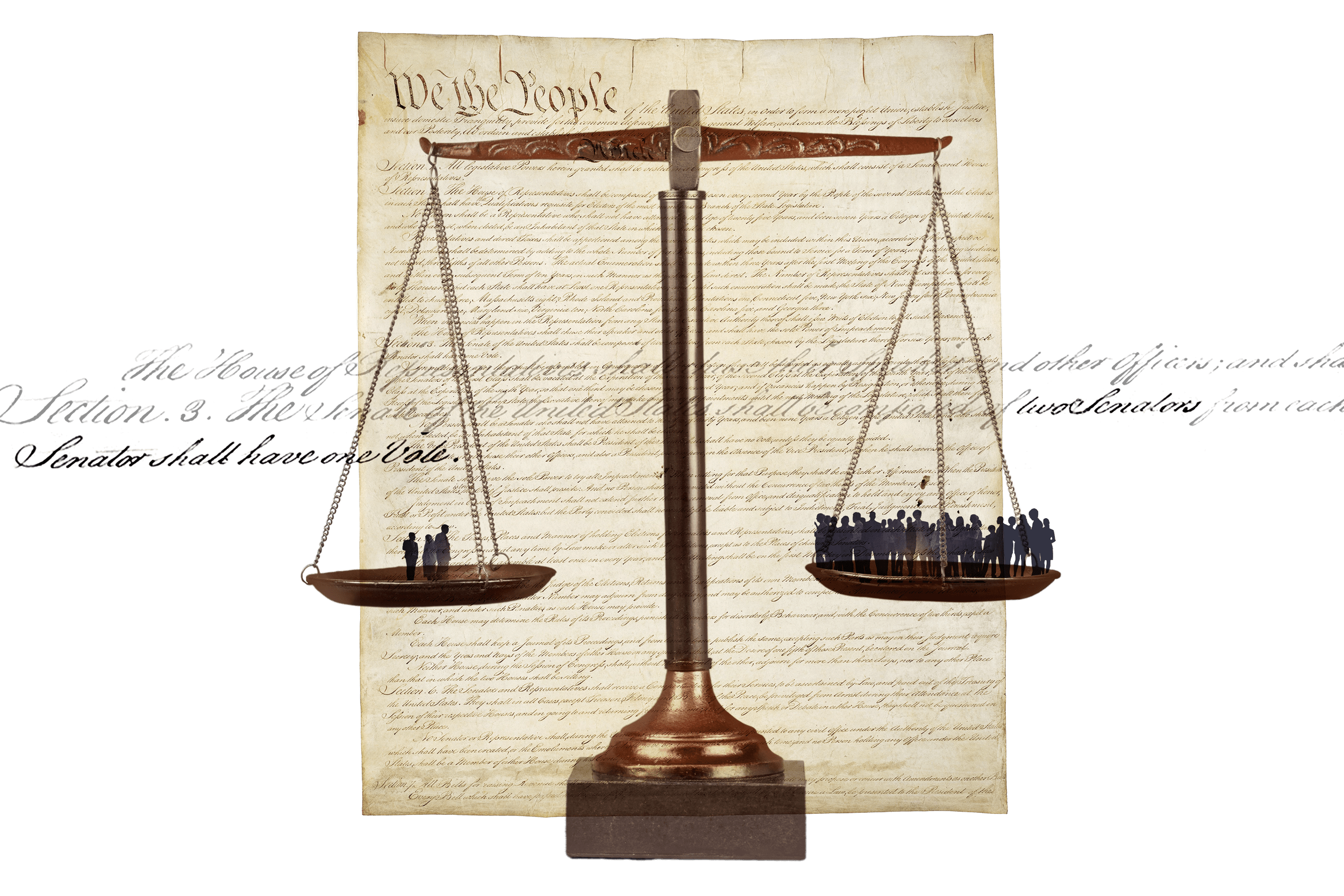

Among the more contentious issues was the question of state representation in the national legislature. Delegates from larger states wanted population to determine how many representatives a state could send to Congress, while small states called for equal representation. The issue was resolved by the Connecticut Compromise, which proposed a bicameral legislature with proportional representation of the states in the lower house ( House of Representatives ) and equal representation in the upper house (Senate).

Another controversial topic was slavery. Although some northern states had already started to outlaw the practice, they went along with the southern states’ insistence that slavery was an issue for individual states to decide and should be kept out of the Constitution. Many northern delegates believed that without agreeing to this, the South wouldn’t join the Union. For the purposes of taxation and determining how many representatives a state could send to Congress, it was decided that enslaved people would be counted as three-fifths of a person. Additionally, it was agreed that Congress wouldn’t be allowed to prohibit the slave trade before 1808, and states were required to return fugitive enslaved people to their owners.

Ratifying the Constitution

By September 1787, the convention’s five-member Committee of Style (Hamilton, Madison, William Samuel Johnson of Connecticut, Gouverneur Morris of New York, Rufus King of Massachusetts ) had drafted the final text of the Constitution, which consisted of some 4,200 words. On September 17, George Washington was the first to sign the document. Of the 55 delegates, a total of 39 signed; some had already left Philadelphia, and three–George Mason (1725-92) and Edmund Randolph (1753-1813) of Virginia , and Elbridge Gerry (1744-1813) of Massachusetts–refused to approve the document. In order for the Constitution to become law, it then had to be ratified by nine of the 13 states.

James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, with assistance from John Jay, wrote a series of essays to persuade people to ratify the Constitution. The 85 essays, known collectively as “The Federalist” (or “The Federalist Papers”), detailed how the new government would work, and were published under the pseudonym Publius (Latin for “public”) in newspapers across the states starting in the fall of 1787. (People who supported the Constitution became known as Federalists, while those opposed it because they thought it gave too much power to the national government were called Anti-Federalists.)

Beginning on December 7, 1787, five states– Delaware , Pennsylvania, New Jersey , Georgia and Connecticut–ratified the Constitution in quick succession. However, other states, especially Massachusetts, opposed the document, as it failed to reserve un-delegated powers to the states and lacked constitutional protection of basic political rights, such as freedom of speech, religion and the press.

In February 1788, a compromise was reached under which Massachusetts and other states would agree to ratify the document with the assurance that amendments would be immediately proposed. The Constitution was thus narrowly ratified in Massachusetts, followed by Maryland and South Carolina . On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the document, and it was subsequently agreed that government under the U.S. Constitution would begin on March 4, 1789. George Washington was inaugurated as America’s first president on April 30, 1789. In June of that same year, Virginia ratified the Constitution, and New York followed in July. On February 2, 1790, the U.S. Supreme Court held its first session, marking the date when the government was fully operative.

Rhode Island, the last holdout of the original 13 states, finally ratified the Constitution on May 29, 1790.

The Bill of Rights

In 1789, Madison, then a member of the newly established U.S. House of Representatives , introduced 19 amendments to the Constitution. On September 25, 1789, Congress adopted 12 of the amendments and sent them to the states for ratification. Ten of these amendments, known collectively as the Bill of Rights , were ratified and became part of the Constitution on December 10, 1791. The Bill of Rights guarantees individuals certain basic protections as citizens, including freedom of speech, religion and the press; the right to bear and keep arms; the right to peaceably assemble; protection from unreasonable search and seizure; and the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury. For his contributions to the drafting of the Constitution, as well as its ratification, Madison became known as “Father of the Constitution.”

To date, there have been thousands of proposed amendments to the Constitution. However, only 17 amendments have been ratified in addition to the Bill of Rights because the process isn’t easy–after a proposed amendment makes it through Congress, it must be ratified by three-fourths of the states. The most recent amendment to the Constitution, Article XXVII, which deals with congressional pay raises, was proposed in 1789 and ratified in 1992.

The Constitution Today

In the more than 200 years since the Constitution was created, America has stretched across an entire continent and its population and economy have expanded more than the document’s framers likely ever could have envisioned. Through all the changes, the Constitution has endured and adapted.

The framers knew it wasn’t a perfect document. However, as Benjamin Franklin said on the closing day of the convention in 1787: “I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such, because I think a central government is necessary for us… I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution.” Today, the original Constitution is on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Constitution Day is observed on September 17, to commemorate the date the document was signed.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

How to Amend the Constitution

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Legal System

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

Amending the Constitution was never meant to be simple. Although thousands of amendments have been discussed since the original document was approved in 1788, there are now only 27 amendments in the Constitution.

Though its framers knew the Constitution would have to be amended, they also knew it should never be amended frivolously or haphazardly. Clearly, their process for amending the Constitution has succeeded in meeting that goal.

Constitutional amendments are intended to improve, correct, or otherwise revise the original document. The framers knew it would be impossible for the Constitution they were writing to address every situation that might come along.

Ratified in December 1791, the first 10 amendments— The Bill of Rights —list and vow to protect certain rights and freedoms granted to the American people and speak to the demands of the Anti-Federalists among the Founding Fathers by limiting the power of the national government.

Ratified 201 years later, in May 1992, the most recent amendment—the 27th Amendment —prohibited members of Congress from raising their own salaries .

Considering how rarely it has been amended during its over 230-year history, it is interesting to note that Thomas Jefferson firmly believed the Constitution should be amended at regular intervals. In a famous letter, Jefferson recommended that we should “provide in our constitution for its revision at stated periods.” “Each generation” should have the “solemn opportunity” to update the constitution “every nineteen or twenty years,” thus allowing it to “be handed on, with periodical repairs, from generation to generation, to the end of time.”

However, the father of the Constitution, James Madison rejected Jefferson’s rash idea of a new constitution every 20 years. In Federalist 62 , Madison denounced volatility of the laws, writing, “Great injury results from an unstable government. The want of confidence in the public councils damps every useful undertaking, the success, and profit of which may depend on a continuance of existing arrangements.”

The difficulty of amending the Constitution has far from frozen the document in stone. The process of changing the Constitution by means other than the formal amendment process has historically taken place and will continue to take place. For example, the Supreme Court, in many of its decisions effectively modifies the Constitution. Similarly, the framers gave Congress, through the legislative process , the power to enact laws that expand the Constitution as needed to respond to unforeseen future events. cIn the 1819 Supreme Court case of McCulloch v. Maryland , Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that the Constitution was intended to endure for the ages and to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.

Two Methods

Article V of the Constitution itself establishes the two ways in which it may be amended:

"The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate."

In simple terms, Article V prescribes that amendments may be proposed either by the U.S. Congress or by a constitutional convention when and if demanded by two-thirds of the legislatures of the states.

Method 1: Congress Proposes an Amendment

An amendment to the Constitution may be proposed by any member of the House of Representatives or the Senate and will be considered under the standard legislative process in the form of a joint resolution.

In addition, as ensured by the First Amendment , all American citizens are free to petition Congress or their state legislatures to amend the Constitution.

To be approved, the amending resolution must be passed by a two-thirds supermajority vote in both the House and the Senate.

Given no official role in the amendment process by Article V, the president of the United States is not required to sign or otherwise approve the amending resolution. Presidents, however, typically express their opinion of proposed amendments and may attempt to persuade Congress to vote for or against them.

States Ratify the Amendment

If approved by Congress, the proposed amendment is sent to the governors of all 50 states for their approval, called “ratification.” Congress will have specified one of two ways by which the states should consider ratification:

- The governor submits the amendment to the state legislature for its consideration; or

- The governor convenes a state ratifying convention.

If the amendment is ratified by three-fourths (currently 38) of the state legislatures or ratifying conventions, it becomes part of the Constitution.

Congress has passed six amendments that never received ratification by the states. The most recent was to give full voting rights to the District of Columbia, which expired unratified in 1985.

Resurrecting ERA?

Clearly, this method of amending the Constitution can be lengthy and time-consuming. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has stated that ratification must be completed within “some reasonable time after the proposal.”

Beginning with the 18th Amendment granting women the right to vote , it has been customary for Congress to set a maximum time period for ratification.

This is why many have felt the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is dead, even though it now needs only one more state to ratify it to achieve the required 38 states.

The ERA was passed by Congress in 1972, and 35 states had ratified it by its extended deadline of 1985. However, in 2017 and 2018, two more states ratified it, concerned about the constitutionality of setting those deadlines.

An effort in Virginia to become the 38th state to ratify the ERA failed by a single vote in February 2019. Pundits expected a battle to ensue in Congress over whether to accept the "late" ratifications had Virginia succeeded.

Method 2: The States Demand a Constitutional Convention

Under the second method of amending the Constitution prescribed by Article V, if two-thirds (currently 34) of the state legislatures vote to demand it, Congress is required to convene a full constitutional convention.

Just as in the Constitutional Convention of 1787 , delegates from every state would attend this so-called “Article V Convention” for the purpose of proposing one or more amendments.

Though this more momentous method has never been used, the number of states voting to demand a constitutional amending convention has come close to the required two-thirds on several occasions. The mere threat of being forced to surrender its control of the constitutional amendment process to the states has often prompted Congress to preemptively propose amendments itself.

Although not specifically mentioned in the document, there are five unofficial yet legal ways of changing the Constitution used more often—and sometimes even more controversially—than the Article V amendment process. These include legislation, presidential actions, federal court rulings, actions of the political parties, and simple custom.

Can Amendments Be Repealed?

Any existing constitutional amendment can be repealed but only by the ratification of another amendment. Because repealing amendments must be proposed and ratified by one of the same two methods of regular amendments, they are very rare.

In the history of the United States, only one constitutional amendment has been repealed. In 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment—better known as “prohibition”—banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the United States.

Though neither has ever come close to happening, two other amendments have been the subject of repeal discussion over the years: the 16th Amendment establishing the federal income tax and the 22nd Amendment limiting the president to serving only two terms.

Most recently, the Second Amendment has come under critical scrutiny. In his opinion piece appearing in The New York Times on March 27, 2018, former Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens controversially called for the repeal of the Bill of Rights amendment, which guarantees “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Stevens argued that it would give more power to people's desire to stop gun violence than the National Rifle Association.

- " The Constitutional Amendment Process " The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. November 17, 2015.

- Huckabee, David C. Ratification of Amendments to the U.S. Constitution Congressional Research Service reports. Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress.

- Neale, Thomas H. The Article V Convention to Propose Constitutional Amendments: Contemporary Issues for Congress Congressional Research Service.

- The U.S. Constitution

- Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution

- Fast Facts About the U.S. Constitution

- The Original Bill of Rights Had 12 Amendments

- The 17th Amendment to the US Constitution: Election of Senators

- The Corwin Amendment, Enslavement, and Abraham Lincoln

- Why No Term Limits for Congress? The Constitution

- 5 Ways to Change the US Constitution Without the Amendment Process

- Which States Have Ratified the Equal Rights Amendment?

- Equal Rights Amendment

- The 18th Amendment

- Overview of the 27th Amendment

- Supermajority Vote in US Congress

- 12th Amendment: Fixing the Electoral College

- The 16th Amendment: Establishing Federal Income Tax

- The 22nd Amendment Sets Presidential Term Limits

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

Let’s fix how we fix the constitution.

Illustration by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

Sanford Levinson on the ‘enduring dysfunctionality’ of Article V

Part of the fixing the constitution series.

Many analysts and citizens believe that the Constitution, more than 230 years old, is out of touch with contemporary America. We asked five scholars to isolate the problem they’d attack first.

Sanford Levinson is a professor at the University of Texas Law School and currently a visiting professor at Harvard Law School.

We have a radically defective Constitution in many different respects. My wife and I co-authored a book, “Fault Lines in the Constitution,” that elaborates no fewer than 20 such fault lines; like their geological counterparts, they can create political earthquakes and tsunamis that would wreak further havoc on an already problematic political system established in 1787 and left remarkably unchanged since. But my task is to name only one shortcoming, which I assume should be a feature of truly enduring import.

So, for enduring dysfunctionality, I easily pick Article V , which structures the process of formal amendment to the Constitution, i.e., the adding to (or, for that matter, the subtraction from) the written text. There have been only 27 such changes to the text in our entire history, with the first 10 in effect accompanying the ratification process. The U.S. Constitution is by far the least-amended such document, especially if one takes account of its age, in the world. Importantly, “the world” in this case includes America’s other constitutions, the much-too-ignored separate constitutions of the 50 states. All have been frequently amended and many have in fact been supplanted over time by brand-new iterations. Each of the 50 states has had an average of just short of three separate foundational constitutions. Massachusetts continues to be formally governed by its constitution of 1780, drafted by John Adams, but it has been amended (so far) a total of 119 times.

“We are trapped inside a constitutional ‘iron cage’ whose bars seem impervious to relaxation even when a majority of the country might agree that change is needed.”

It is absurd to believe that the Constitution is not in need of change. That was certainly not the view of the Framers themselves, who rightly criticized the Articles of Confederation for making amendment far too difficult inasmuch as it required the unanimous consent of all 13 state legislatures. The Philadelphia Convention simply ignored this, realizing that compliance would have doomed the project of achieving necessary change and replacing what Alexander Hamilton described as an “imbecilic” political system. And the Framers believed that Article V established a workable amendment system, including even the possibility of a brand-new constitutional convention.

As with many of their assumptions, they were wrong.

As a practical matter, the hurdles set up by Article V, including the need for two-thirds support in both the House and the Senate and then ratification by the separate legislative houses in 38 states (a minimum of 75 such houses, including Nebraska’s Unicameral), make it nearly impossible to imagine that anything truly controversial could surmount them. We are trapped inside a constitutional “iron cage” whose bars seem impervious to relaxation even when a majority of the country might agree that change is needed.

What contributes to this imprisonment is a grotesquely exaggerated veneration for the Constitution. This is almost completely absent with regard to state constitutions; they are ruthlessly evaluated as to their adequacy to meet contemporary challenges. There is no “cult of the Framers” of state constitutions or an almost mystical belief that assumptions that made sense 200 years ago necessarily do so today. But the combination of veneration and the sheer difficulty of change have led to a dangerous reversal of the maxim “If it isn’t broken, it doesn’t need fixing.” Instead, we seem to operate on the presumption that if, as a practical matter, it can’t be fixed, then it really isn’t broken. Denial reigns (and reins us in). Unfortunately, the Constitution is broken, and it does need fixing. But whether we can surmount the barriers established by Article V remains an open question.

— As told to Christina Pazzanese/Harvard Staff Writer

Share this article

Also in this series:.

Amendments should start with states

U.S. needs to smooth process without lowering high bar for constitutional change, says Stephen Sachs

Change the Senate

Disproportionate influence of smaller states creates ‘significant democratic deficit,’ Vicki Jackson argues

Enshrine an affirmative right to vote

Amendment would demonstrate ‘absolute commitment’ to full participation in U.S. democracy, argues Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Let the House grow!

A better Electoral College requires a Congress as elastic and flexible as the drafters of the Constitution intended, says Danielle Allen

You might like

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

- भाषा : हिंदी

- Classroom Courses

- Our Selections

- Student Login

- About NEXT IAS

- Director’s Desk

- Advisory Panel

- Faculty Panel

- General Studies Courses

- Optional Courses

- Interview Guidance Program

- Postal Courses

- Test Series

- Current Affairs

- Student Portal

- Pre Cum Mains Foundation Courses

- GS + CSAT Pre cum Main Foundation Course

- GS Pre cum Main Foundation Course

- GS + CSAT + Optional

- GS + Optional

- Prelims Courses

- Current Affairs Course for CSE 2025

- CSAT Course

- Current Affairs for Prelims (CAP)-2024

- Mains Courses

- Mains Advance Course (MAC)

- Essay Course Cum Test Series

- First Step — NCERT Based Course

- Optional Foundation Courses

- Mathematics

- Anthropology

- Political Science and International Relations (PSIR)

- Optional Advance Courses (Optional Through Questions)

- Civil Engineering

- Electrical Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

- Interview Guidance Programme / Personality Test Training Program

- GS + CSAT Postal Courses

- Current Affairs Magazine – Annual Subscription

- GS+CSAT Postal Study Course

- First Step Postal Course

- Postal Study Course for Optional Subjects

- Prelims Test Series for CSE 2024 (Offline/Online)

- General Studies

- GS Mains Test Series for CSE 2024

- Mains Test Series (Optional)

- Paarth PSIR

- PSIR Answer Writing Program

- PSIR PRO Plus Test Series

- Mathematics Year Long Test Series (MYTS) 2024

- Indian Economic Services

- Anubhav (All India Open Mock Test)

- Prelims (GS + CSAT)

- Headlines of the Day

- Daily Current Affairs

- Editorial Analysis

- Monthly MCQ Compilation

- Monthly Current Affairs Magazine

- Previous Year Papers

- Down to Earth

- Kurukshetra

- Union Budget

- Economic Survey

- NIOS Study Material

- Beyond Classroom

Amendment of the Constitution: Meaning, Types, Procedure & Limitations

The Constitution of India , as the supreme law of the land , should be responsive to changing needs and situations. The provision for amendment of the Constitution of India under Article 368 accommodates this requirement. This article of Next IAS aims to explain the meaning of the amendment of the Constitution, its procedure, types, significance, limitations, and more.

Meaning of the Amendment of the Constitution

The Amendment of the Constitution refers to the process of making changes such as the addition, variation, or repeal of any provision of the Constitution in accordance with the procedure laid down for the purpose. The purpose of Constitutional Amendments is to ensure that the Constitution remains a living document capable of adapting to changing circumstances while upholding its fundamental principles and values.

Provisions of Amendment of Indian Constitution

The Indian Constitution, being a living document, provides for its amendment. The detailed provisions regarding the Amendment of the Constitution of India are contained in Article 368 in Part XX of the Indian Constitution . These provisions define the process and scope of amending the Constitution.

Various aspects of the Amendment of the Constitution of India are dealt with in detail in the sections that follow.

Procedure for Amendment to the Indian Constitution

- A bill for the amendment of the Constitution can be introduced only in either house of the Parliament, not in the State Legislatures.

- The bill can be introduced either by a minister or by a private member and does not require prior permission of the President.

- The bill must be passed in each House by a Special Majority , that is, a majority (more than 50 percent) of the total membership of the House and a majority of two-thirds of the members of the House present and voting.

- Each House must pass the bill separately. In case of a disagreement between the two Houses, there is no provision for holding a joint sitting of the two Houses for deliberation and passage of the bill.

- If the bill seeks to amend the federal provisions of the Constitution, it must also be ratified by the legislatures of half of the states by a Simple Majority , that is, a majority of the members of the House present and voting.

- After duly passed by both Houses of Parliament and ratified by the State Legislatures, where necessary, the bill is presented to the President for his/her assent.

- The President must give his assent to the bill. He can neither withhold his assent to the bill nor return the bill for reconsideration by the Parliament.

- After the President’s assent, the bill becomes an Act (i.e. a Constitutional Amendment Act) , and the Constitution stands amended as per the changes made by the Act.

Types of Amendments in Indian Constitution

- By a Special Majority of Parliament (50% of the total membership of the House + 2/3rd of the members present and voting),

- By a Special Majority of Parliament plus ratification of 1/2 of the states by a Simple Majority,

- However, these amendments are not deemed to be amendments for the purpose of Article 368.

- Amendment by a simple majority of the Parliament,

- Amendment by a special majority of the Parliament, and

- Amendment by a special majority of the Parliament and the ratification of half of the State Legislatur es.

- The process and scope of each type of amendment are discussed in detail below.

By Simple Majority of Parliament

- Several provisions in the Indian Constitution can be amended by a Simple Majority i.e. 50 percent of members present and voting.

- It is to be noted that these amendments fall outside the scope of Article 368.

- Admission or establishment of new states,

- Formation of new states and alteration of areas, boundaries, or names of existing states,

- Abolition or creation of Legislative Councils in states, etc.

By Special Majority of Parliament

- The majority of the provisions in the Constitution can be amended only by a Special Majority (more than 50 percent of the total membership of the House and a majority of two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting).

- Fundamental Rights,

- Directive Principles of State Policy,

- All other provisions that are not covered by the first and third categories.

By Special Majority of the Parliament and Consent of Half States

- The provisions of the Constitution that are related to the federal structure of the Indian polity require for their amendment a Special Majority of the Parliament along with the consent of half of the state legislatures by a Simple Majority.

- It does not require that all the states give their consent to the bill. The moment half of the states give their consent, the formality is completed and the bill is passed.

- The constitution has not prescribed any time limit within which the states should give their consent to the bill.

- Election of the President and its manner,

- Extent of the executive power of the Union and the States,

- Provisions related to the Supreme Court and High courts, etc.

Basic Structure of the Constitution

- The Basic Structure of the Indian Constitution refers to a set of core principles deemed essential, which cannot be destroyed or altered through amendments by the Parliament. This concept, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, was established by the Supreme Court in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case (1973).

- The Doctrine of Basic Structure is a check on the amending power of the Parliament and ensures that the fundamental ethos, principles, and the underlying framework of the Constitution remain intact, preserving its spirit.

Significance of the Constitutional Amendment

The provision for amendment of the Indian Constitution carries multifarious significance as listed below:

- Adaptability in Governance : The Constitution lays down fundamental principles of governance. A diverse and constantly evolving country like India cannot be governed by a set of fixed rules. The amendment of the constitution enables to bring changes in governance as per needs and situations.

- Accommodating New Rights : With rising awareness, various sections of society are becoming assertive of their rights . For example, of late, the LGBT community has been demanding their rights. The amendment enables providing for such rights.

- Evolution of New Rights : New interpretations of the Constitution led to the evolution of new rights . For example, a new interpretation of the Right to Life and Personal Liberty gave rise to the Right to Privacy. The amendment enables accommodating such rights.

- Addressing Emerging Issues : It enables addressing new emerging trends like bans, vigilantism, etc.

- Bringing Social Reform : It enables the eradication of outdated socio-cultural practices to usher in modernity.

Criticism of the Amendment Procedure

The procedure for amendment of the Indian constitution has been criticized on the following grounds:

- There is no provision for a special body for amending the Constitution such as the Constitutional Convention or Constitutional Assembly . The constituent power is vested in the Legislative Body itself i.e. the Parliament and the State Legislatures (in a few cases).

- There is no provision for a special process for amending the Constitution. Except for the requirement of Special Majority, the process of amendment is similar to that of a legislative process.

- The power to initiate an amendment lies only with the Parliament. The states have no such powers (except for passing a resolution to create or abolish state legislative councils).

- A major part of the Constitution can be amended by the Parliament alone. Only in a few cases, the consent of the state legislatures is required, and that too, only half of them.

- Lack of provision for holding a joint sitting of both Houses of Parliament for a constitutional amendment bill, sometimes, leads to the situation of a deadlock.

- The provisions relating to the amendment procedure, being too sketchy, leave a wide scope for creating disputes and taking the matters to the judiciary.

The process of amending the constitution is a crucial aspect of maintaining the relevance and adaptability of India’s legal framework to changing societal needs and circumstances. These constitutional amendments have played a significant role in shaping the country’s governance and legal framework. It ensures that the Constitution remains a living document, reflective of its people’s aspirations, challenges, and evolving societal values, ensuring its relevance and efficacy for generations to come.

Important Amendments in the Indian Constitution

Frequently asked questions (faqs), what is a constitutional amendment.

The Constitutional Amendment refers to the process of making changes such as the addition, variation, or repeal of any provision of the Constitution in accordance with the procedure laid down for the purpose.

Who has the power to amend the Constitution?

The Parliament alone has the power to amend the Constitution.

What is Simple Majority?

A Simple Majority refers to a majority of more than 50% of the members present and voting in the House.

What is Special Majority?

As per Article 368, Special Majority refers to the majority of 50% of the total strength of the House and a majority of 2/3rd of the members present and voting in the House.

What is Absolute Majority?

Absolute Majority refers to the majority of more than 50% of the total membership of the House.

What is Effective Majority?

It refers to the majority of more than 50% of the effective strength of the house which does not include the vacant seats of the total strength of the House.

What is Article 368?

Article 368 of the Indian Constitution pertains to the procedure for amending the Constitution of India.

Which part of the Constitution deals with amendment?

Article 368 of Part XX deals with the Amendment Procedure of the Indian Constitution.

Can Article 32 be amended?

Article 32 can be amended like any other provision of the Constitution without affecting the Basic Structure established by the Supreme Court of India in the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati vs. the State of Kerala Case (1973).

How many times was the Preamble of the Constitution amended?

The Preamble of the Indian Constitution has been amended only once so far.

What is the latest amendment in the Indian Constitution?

The latest amendment in the Indian Constitution was the 106th Amendment Act, passed in 2023. This amendment deals with women’s reservation in Lok Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies, and the Legislative Assembly of the National Capital Territory of Delhi. It reserves one-third of all seats for women, including those already reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

National emergency (article 352), emergency provisions in indian constitution, sessions of parliament, sovereignty of parliament, roles, powers and functions of parliament, state council of ministers (com), leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Featured Post

NEXT IAS (Old Rajinder Nagar)

- 27-B, Pusa Road, Metro Pillar no. 118, Near Karol Bagh Metro, New Delhi-110060

NEXT IAS (Mukherjee Nagar)

- 1422, Main Mukherjee Nagar Road. Near Batra Cinema New Delhi-110009

NEXT IAS (Bhopal)

- Plot No. 46 Zone - 2 M.P Nagar Bhopal - 462011

- 8827664612 ,

NEXT IAS (Jaipur)

- NEXT IAS - Plot No - 6 & 7, 3rd Floor,Sree Gopal Nagar, Gopalpura Bypass, Above Zudio Showroom Jaipur (Rajasthan) - 302015

NEXT IAS (Prayagraj)

- 31/31, Sardar Patel Marg, Civil Lines, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh - 211001

Advocate General of the State (AGS)

The United States’ Unamendable Constitution

How our inability to change America’s most important document is deforming our politics and government.

Illustrations by Ben Hickey

W hen the U.S. Constitution was written, in 1787, it was a startling political novelty, even in an age of constitution-making . Before the Constitutional Convention, James Madison made a study of “ ancient and modern confederacies ,” but written constitutions were so new that he had hardly any to read. Also, no one had any real idea how long a written constitution would last, or could, or should. Thomas Jefferson thought that nineteen years might be about right. He wasn’t far wrong: around the world, written constitutions turn out to have lasted, on average, only seventeen years before being scrapped. Not the U.S. Constitution. It’s lasted more than two hundred years and hasn’t been amended in any meaningful way since 1971, more than half a century ago.

Laws govern people; constitutions govern governments. Lately, American democracy has begun to wobble, leaning on a constitution that’s grown brittle. How far can a constitution bend before it breaks? The study of written constitutions has become a lot more sophisticated since Madison’s day. A project called Constitute has collected and analyzed every national constitution ever enacted. “Constitutions are designed to stabilize and facilitate politics,” the project’s founders write. “But, there is certainly the possibility that constitutions can outlive their utility and create pathologies in the political process that distort democracy.” Could that be happening in the United States?

The question is urgent, the answer elusive. There are a few different ways to tackle it. One is to investigate the history of efforts to amend the Constitution, a subject that’s been surprisingly little studied. Working closely with Constitute, I head a project called Amend —an attempt to assemble a comprehensive archive of every effort to amend the U.S. Constitution.

Another approach is to query the public. In July, 2022, the nonprofit organizations More in Common and YouGov collaborated with Constitute and Amend to conduct a national survey. It asked a sample of two thousand Americans questions about whether the Constitution is still working, and, if it’s not, how to fix it.

In this piece, The New Yorker will be asking you some of the same questions. More than two centuries on, does the U.S. Constitution need mending?

Which statement comes closest to your view of the U.S. Constitution?

Public-opinion surveys have been asking Americans this question for a long time, as the political scientist Zachary Elkins has demonstrated. In 1937, when asked “Should the Constitution be easier to amend?,” twenty-eight per cent of those surveyed said yes, and sixty per cent said no. A half century later, in 1987, another survey asked more or less the same question, and got more or less the same answer: twenty per cent of respondents said that the Constitution was too hard to amend, and sixty per cent said that amending it was about as hard as it ought to be.

This era of contentment appears to have come to an end. In 2022, forty-one per cent of respondents said that the Constitution should be more frequently reviewed and amended, and another seven per cent that it should be entirely rewritten and replaced. Those are the over-all numbers. But the results are strikingly polarized. Seventy-two per cent of Republicans think that the Constitution is basically fine as is; seventy-two per cent of Democrats disagree.

In 1787, the men who wrote the Constitution added a provision for amendment—Article V—knowing that changing circumstances would demand revision. To amend meant, at the time, to correct, to repair, and to remedy; it especially implied moral progress, of the sort that you indicate when you say you’re making amends or mending your ways. The idea for an amendment clause, a constitutional fail-safe, came from the states, where people demanded that their constitutions be revisable, “to rectify the errors that will creep in through lapse of time, or alteration of situation,” as one town meeting put it. No single article of the Constitution is more important, the Framers believed, because, if you couldn’t revise a constitution, you’d have no way to change the government except by revolution.

W ithout Article V, the Constitution would not have been ratified. But, from the start, most amendments failed, and were meant to. Amending the Constitution requires a double supermajority: an amendment introduced in Congress has to pass both houses by a two-thirds vote, and then must be approved by the legislatures of three-quarters of the states. Also, a lot of proposed amendments are horrible. In March, 1861, weeks before shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Congress passed a doomed amendment intended to stop the secession of Southern states: “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” Others have been silly, like the amendment, proposed in 1893, that would have renamed the country the United States of the Earth. And plenty have been perfectly reasonable but turned out to be unnecessary. The Child Labor Amendment proposed to give Congress the “power to limit, regulate, and prohibit the labor of persons under eighteen years of age.” It passed Congress in 1924 and went to the states for ratification, where it failed; later, child labor was abolished under the terms of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

More than ten thousand amendments have been introduced into Congress. Many more never made it that far. Only twenty-seven have ever been ratified and become part of the Constitution. Looking at them all at once, straight off, you can see patterns. Most successful amendments involve a constitutional settlement in the aftermath of a political revolution. Ratifications have come, mostly, in flurries: first during the struggle over the Constitution itself, when its critics secured ratification of amendments one through ten, the Bill of Rights; then during the Civil War and Reconstruction, a second founding, marked by the ratification of amendments thirteen through fifteen; and, finally, during the Progressive Era, when reformers achieved amendments sixteen through nineteen. Scattered amendments have been ratified since, notably the Twenty-fifth, which established a procedure in the event of Presidential debility, and the Twenty-sixth, which lowered the voting age to eighteen. The Twenty-seventh Amendment, concerning congressional salaries, was ratified in 1992, but it was first proposed in 1789. All of these have been one-offs, rather than part of efforts to constitutionalize political revolutions.

Amending the Constitution

Since 1789, members of Congress have introduced more than ten thousand proposals to amend the Constitution. Nonetheless, only twenty-seven amendments have ever been ratified, giving the United States one of the lowest amendment rates in the world. The rest are “discards,” amendments that failed. In this time line, amendment proposals are grouped by congressional session and ordered by the year they were introduced as bills.

It’s always been hard to amend the Constitution. But, in the past half century, it’s become much harder—so hard that people barely bother trying anymore. Between 1789 and 1804—fifteen years—the Constitution was amended twelve times. Between 1805 and 2022—two hundred and seventeen years—it’s been amended only fifteen times, and since 1971 only once. The Framers did not anticipate two developments that have made the double supermajority required of Article V almost impossible to achieve: the emergence of the first political parties, which happened in the seventeen-nineties, and the establishment of a stable two-party system, in place by the eighteen-twenties. As John Adams complained, in 1808, “the Principle Seems to be established on both Sides that the Nation is never to be governed by the Nation: but the whole is to be exclusively governed by a Party.” This state of affairs raised the bar for amending the Constitution. The current era of party polarization, which began in the early nineteen-seventies, has raised the bar much, much higher.

How high? Political scientists talk about the “amendment rate”—the number of amendments to any given constitution, per year. Divide twenty-seven ratified amendments by two hundred and thirty-three years and you get 0.12, the U.S. amendment rate. It is one of the lowest rates in the world.

What effect is that having on American politics and government? Consider the Electoral College . Proposals to reform or abolish the Electoral College have been introduced in Congress more than seven hundred times since 1800, and electing the President by popular vote has enjoyed a great deal of popular support for the past half century or so. In 1967, sixty-five per cent of Americans were in favor of it. And support has remained at about the same level ever since—with the exception of a notable dip in 2016.

What do you think?

As you may know, Presidents are chosen not by direct popular vote but by the Electoral College system, in which each state receives electoral votes based on its population. In the 2016 election, for example, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote, and Donald Trump won the Electoral College vote. Would you favor passing a constitutional amendment that would determine the winner of future Presidential elections by popular vote, or would you rather continue the current system, which determines the winner by Electoral College votes?

The More in Common/YouGov 2022 survey suggests that, if a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College were a matter of public opinion, it would win, forty-seven per cent to thirty-five. Support, however, varies by party: seventy-three per cent of Democrats want to abolish the Electoral College, and sixty-three per cent of Republicans want to keep it. Such an amendment doesn’t seem to lie in the realm of the possible. Accordingly, most people interested in this reform have sought instead to increase the size of the House of Representatives, and to admit Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia , and Guam to statehood—both measures that would alter the number of delegates to the Electoral College. Meanwhile, domestic tranquillity remains elusive. In two of the past six Presidential elections, 2000 and 2016, the winner of the popular vote has lost the Presidency; in the aftermath of the 2020 election, supporters of the loser staged an armed insurrection at the Capitol.

A n unamendable constitution is not an American tradition. U.S. state constitutions are much easier to amend than the federal Constitution. The average amendment rate of a U.S. state is 1.23; Alabama’s constitution has an amendment rate of 8.07. A high amendment rate is generally not a sign of political well-being, though, since it comes at the cost of stability. Also, it can be disastrous in states where constitutions can be amended by a popular referendum: research suggests that the language of ballot initiatives is so mealy-mouthed that many voters, confused or misled, end up casting votes that go against their actual preferences. It’s a Goldilocks problem. You don’t want your constitution to be too hard to amend, but you don’t want it to be too easy, either.

Making the Constitution easier to amend would itself require a constitutional amendment, which means it’s not going to happen. But what if it could? The most radical way to make amending easier would be to drop the supermajority requirements, allowing Congress to pass proposed amendments by a simple majority, and then sending them not to state legislatures for ratification but to the whole of the people, by way of a national popular referendum. I’m not proposing this. No one is, not even the far-right movement—a descendant of the Tea Party—that calls for a second Constitutional Convention. Still, it’s a worthwhile thought experiment. Would the eighty-five per cent of liberals who would like to make the Constitution easier to amend be happy with the results?

Consider, for instance, the hot-button issue of immigration. Amendments to repeal birthright citizenship—a guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment—have been introduced into Congress at least twenty times since 1991. Red states whose governors have taken strong anti-immigration positions—including Greg Abbott of Texas and Ron DeSantis of Florida—might well support amendments to their state constitutions limiting the rights of immigrants. And it’s easy to imagine a national initiative.

Would you favor or oppose the following? A constitutional amendment that would deny the children of undocumented immigrants, tourists, and temporary residents automatic U.S. citizenship?

Terrifyingly, using a referendum-based system, a federal constitutional amendment ending birthright citizenship would be only very narrowly defeated, forty-nine per cent to fifty-one, according to the poll conducted by More in Common and YouGov.

You could ask the same question of abortion. This summer, Kansas voters struck down a proposed state constitutional amendment banning all abortions. This November, voters in California, Michigan, and Vermont will vote on amendments to their state constitutions guaranteeing a right to abortion. What would be the result if abortion were put to a national popular referendum?

Would you favor or oppose the following? A constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to access abortion.

Surveys aren’t binding. They’re not even especially reliable. But this 2022 survey offers at least a glimpse of what might happen if a slate of constitutional amendments were voted on in a nationwide referendum this year. A constitutional amendment to restrict abortion would likely be ratified, fifty-one to forty-nine—and yet, paradoxically, a constitutional amendment to guarantee a right to abortion would also be ratified, fifty-seven to forty-three.

Under the current rules, no federal abortion amendment could possibly be ratified. No proposal, in either direction, is going to earn a two-thirds majority in both houses. But that doesn’t mean that the Constitution isn’t being changed on this question. Instead, it’s undergoing a massive change by way of constitutional interpretation, in the hands of the Supreme Court.

“N othing new can be put into the Constitution except through the amendatory process,” Justice Felix Frankfurter declared, in 1956, and “nothing old can be taken out without the same process.” That’s not strictly true. The Constitution has become unamendable, but it has not become unchangeable. Its meaning can be altered by the nine people who serve on the Supreme Court. They can’t rewrite it, but they can reread it.

The Framers did not design or even anticipate this method of altering the Constitution. They didn’t plan for judicial review (the power exercised by the Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of legislation), and they thought they’d protected against the possibility of judicial supremacy (the inability of any other branch of government to check the Court’s power).

As with the filibuster, whether you like judicial supremacy generally depends on whether your party’s in power or out. The Court is the least democratic branch of government. But it also has the ability to protect the rights of minorities against a majority. In the nineteen-fifties, because Jim Crow laws meant that Blacks in the South could not vote, it proved impossible to end segregation through electoral politics or a constitutional amendment; instead, the N.A.A.C.P. sought to end it by bringing Brown v. Board of Education to the Supreme Court. Since then, the Court has implemented all sorts of constitutional changes: it has secured the rights of criminal defendants; established rights to contraception, abortion, and same-sex marriage; declared corporate campaign donations to be free speech; and interpreted the Second Amendment as restricting the government’s ability to regulate firearms. Which of these you believe to be bad decisions and which good depends on your position on all manner of things. But, unlike a constitutional amendment, every decision the Court makes it can reverse, the way that, this year, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization , it overturned Roe v. Wade, from 1973. (You can reverse a constitutional amendment, but only with another one: that’s how Prohibition ended.)

In 2002, Congress considered a proposed amendment that read, “Marriage in the United States shall consist only of the union of a man and a woman.” Introduced again and again in subsequent congressional sessions, it went nowhere. Instead, in 2015, in Obergefell v. Hodges , the Supreme Court determined that same-sex marriage is constitutionally guaranteed under the equal-protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Given the direction the Court is headed , will that ruling be enough to protect that right? Alternatively, if this question, too, were submitted to a national popular vote, how would Americans lean?

Would you favor or oppose the following? A constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to marry of any two adult citizens, regardless of sex or gender.

Much depends on how survey questions are phrased. But the survey data suggest that, in a referendum, a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage would be defeated, thirty-five per cent to sixty-five, while a constitutional amendment guaranteeing same-sex marriage would be ratified, sixty-two to thirty-eight.

Reversing Roe v. Wade did not require a constitutional amendment (even though many were proposed). Instead, it required something even more extraordinary: a wholly new mode of constitutional interpretation. Roe built on a 1965 case, Griswold v. Connecticut, which protected access to contraception under a right to privacy. After Griswold, conservative critics of the Court began to devise an approach to constitutional interpretation custom-built to defeat it: the jurisprudence of originalism. Robert Bork first proposed its framework in 1971, in an essay in which he argued against Griswold. Originalism undergirds one of the most radical constitutional reversals in recent American history: the reinterpretation of the Second Amendment as protecting an individual right to bear arms, as opposed to the right of the people to form militias. (Bork himself disagreed with this reinterpretation, which has been advanced by the N.R.A.) This spring, in the Bruen case , the Court reinforced its N.R.A.-informed interpretation of the Second Amendment. What would happen if the Second Amendment were put to a referendum?

The Second Amendment currently reads as follows: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Which revised version, if any, would be closest to your preference?

There’s a good reason that American constitutional amendments are not decided through national referendums. (Consider, after all, that Brexit was decided by a national popular referendum.) “A nation of philosophers is as little to be expected as the philosophical race of kings wished for by Plato,” Madison wrote, in Federalist No. 49. “The danger of disturbing the public tranquillity by interesting too strongly the public passions, is a still more serious objection against a frequent reference of constitutional questions to the decision of the whole society.” If the question of whether the government can regulate the possession of firearms were put to the people, and the people were evenly divided, what would be the consequence? Madison worried that putting constitutional matters to the people directly was an experiment “of too ticklish a nature to be unnecessarily multiplied.” Then again, plainly the people ought to have a greater role than they have when no amendments are any longer even sent to the states.

All sorts of ideas are floating around for how to shake things loose. Constitutional populists—Tea Partiers, Trumpists, and other conservatives, from Rick Santorum to Greg Abbott—have rallied around a proposal to revise the Constitution by way of a provision in Article V that’s never been used, and which holds that the country, “on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments.” Nineteen state legislatures have made some version of that application; thirty-four are required. Since 2013, this effort has been headed by the Convention of States project, funded in part by the Koch brothers. A new book, “ The Constitution in Jeopardy ,” co-authored by the former Democratic senator Russ Feingold, warns that, if Republicans win a few more state legislatures in this year’s midterms, a convention that could gut the Constitution, or at least the federal government, is around the corner.

If you could fix Article V, how would you do it? In 2020, the National Constitution Center asked three teams of experts—constitutional lawyers, mostly, divided into teams of libertarians, conservatives, and progressives—to draft a new constitution. The libertarians, who joked that “all we needed to do was to add ‘and we mean it’ at the end of every clause,” left Article V alone. The conservatives decided to make their constitution easier to amend (“but not too much easier”) by lowering the voting requirement in Congress from two-thirds to three-fifths, and in the states from three-fourths to two-thirds. And the progressives came up with a plan under which amendments could be proposed “not just by two-thirds of members of each House (or two thirds of states) but by Members of each House (or states, for constitutional conventions) representing two-thirds of the U.S population.” Think of it as an amendment caucus; if an amendment succeeded in Congress, it could then be ratified either by three-quarters of the states (the way things are now) or “by states representing three-fourths of the population.” No one is calling for constitutional amendment by national referendum.

A mericans aren’t going to amend Article V anytime soon because we’re not going to amend any part of the Constitution anytime soon. In the end, the really interesting question isn’t what would happen if the people could amend the Constitution by popular vote but what actually happened, in the first place, to cripple Article V, and give the Supreme Court superpowers.

The Constitution became effectively unamendable in the early nineteen-seventies, just when originalism began its slow, steady rise. The Twenty-sixth Amendment, which was ratified in 1971 and lowered the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen, an antiwar-movement objective, turned out to be the only amendment that constitutionalized an aim of one of the political revolutions of the sixties—the women’s movement, the civil-rights movement, the gay-rights movement, and the environmental-rights movement. People did not see that coming: they expected those movements to result in amendments.

In 1970, the civil-rights activist, constitutional theorist, and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the passage of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment, barring discrimination on the basis of sex, was essential to ending what Murray referred to as Jane Crow, and to inaugurating a new and better era in the history of the nation’s constitutional democracy:

The adoption of the Equal Rights Amendment and its ratification by the several States could well usher in an unprecedented Golden Age of human relations in our national life and help our country to become an example of the practical ideal that the sole purpose of governments is to create the conditions under which the uniqueness of each individual is cherished and is encouraged to fulfill his or her highest creative potential.

That, of course, did not come to pass. No golden age ever does. In 1972, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment and sent it to the states, where most observers expected that it would secure quick ratification. But, in 1973, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Roe v. Wade. And conservatives began a decades-long campaign to advance originalism, reverse Roe, and defeat the E.R.A. by arguing, as Phyllis Schlafly did, that “the E.R.A. means abortion.” Every significant amendment attempted since has failed. And, although efforts are ongoing to revive the E.R.A., so far they haven’t succeeded, either.

Polarization weakened Article V. But the Constitution really snapped when it became too brittle to guarantee equal rights to women. Liberals gave up on constitutional amendment; conservatives abandoned it in favor of advancing originalism. Still, nothing’s broken that can’t be mended. It’s a question, now, of how. ♦

Funding for Amend has been provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Harvard Data Science Initiative, and the Inequality in America Initiative. Special thanks to Zachary Elkins and Constitute and to the Comparative Constitutions Project and More in Common . Research assistance has been provided by Mia Hazra, Henry Haimo, Samuel Lowry, Imaan Mirza, Tobias Resch, Fawwaz Shoukfeh, Jonathan Schneiderman, and Meimei Xu.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Kyle Chayka

By Zadie Smith

By Eric Lach

By Susan B. Glasser

Column: The U.S. Constitution is flawed. But a constitutional convention to fix it is downright scary

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The U.S. Constitution is flawed and ought to be changed.

Here’s where I’d start: