It appears JavaScript is disabled. In order for this website to function correctly you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

In order to drive professionally you must also pass the driver CPC case study test (also known as the Driver CPC case study theory test - Step 2). Both the truck and the bus case study tests ask you to look at three real-life situations a professional driver might face.

Each case study test is computer-based and user-friendly, and works as follows:

- you will be asked 15 questions on each of three real-life driver situations

- to pass you must score at least 5 out of 15 in each situation and have an overall score of at least 28 out of 45.

You can prepare for the case study test by reading and learning the Rules of the Road. There are a wide range of official printed, digital and online learning materials available.

Case study test learning resources

To prepare for your case study test you should study the following:

- The Official driver theory test truck and bus book , available online or in most book shops

- The Rules of the Road

The RSA also has approved Driver CPC Trainers who can help you pass the CPC case study test.

How to book your case study test

If you want to become a category C (CPC truck) or category D (CPC bus) driver you must pass a case study test.

You must have passed the Driver CPC theory test (Step 1) in the relevant category before you can sit your case study test.

You have the option to sit it at any of the 40+ theory test centre locations nationwide.

If you're ready, you can go ahead and book your case study test online now.

/driver-theory-test.jpg)

Book your case study test

Book, reschedule or cancel a CPC theory (case study) test

Rescheduling or cancelling your case study test

You can reschedule or cancel your case study test online.

You must submit your cancellation or rescheduling request at least five days before your test booking. These five days must include three working days.

Your case study test result

When you complete your case study test you will be given a score report. This will tell you whether you have passed or failed your test.

If you've passed

When you pass the case study test you are issued with a driver CPC case study test certificate. This is valid for up to two years. You should apply for a learner permit within that time. After two years the certificate will no longer be valid and you will have to pay for and sit the case study test again.

If you're unsuccessful

If you're unsuccessful at your case study test, you'll get a score report with feedback telling you where you went wrong. Pay attention to these areas as they will help with your revision and give you a better chance of passing next time.

You can book another case study test straight away, but you can't take it for another three clear working days.

Frequently asked questions

Yes. But we would not recommend this as the multiple choice theory test can take up to 3 hours to complete (depending on which theory test you have applied for) and the case study test takes 1.5 hours to complete.

No. Once you have passed the theory test in the relevant category you can go ahead and apply for your learner permit straight away and take your case study test at a later time.

No, but you must pass the case study test before you can apply for and complete the CPC walk around test.

Have you tried our help section?

In Your Theory Test Exam You Will Be Asked 5 Case Studies Question, Practice Online Case Study Questions and Answers For Free. Let’s start case study a questions.

You’re one step closer to passing your official driving theory test

Your driving theory test is one of the most daunting parts of learning to drive. To help you, we have more than 25 theory tests for you to practice. The questions are very similar to what you can expect on the day. Pass your driving theory test first time with our top free tests.

Click here to find your local theory test center.

Click here to book your driving theory test.

Book your practical driving test

Change your address on UK Driver Licence For FREE

Case Study A

You plan to visit a friend who lives in a town a full day’s drive away.

Two weeks before your journey, you realise that your vehicle excise license (road tax) will expire while you’re away.

At the beginning of the journey, you reach a roundabout. Another car cuts in front of you, causing you to do an emergency stop.

Later, you join the motorway, where a red X is flashing above the outside lane.

While travelling along the motorway, you start to feel tired and stop at a service station.

It’s just after 11 pm when you park outside your friend’s house.

Why must you avoid using your horn when parked outside your friend's house?

What should you do at the roundabout, what should you do two weeks before you leave, what should you do at the service station, what must you do on the motorway.

Share your Results:

Highway Code PDF 2024

Highway Code PDF 2024 Manual Official Book (Augest 2019 changes) length of the burn cooling has modified from 10 to 20 minutes: “Cool the burn

Hazard Perception Test

Hazard Perception Test 2024 Practice and Guidance The multiple-choice section is the first section of your UK driving theory test. The next section is the

Top 5 Common Theory Test Quesions

Can You Answer 5 Common Theory Test Questions in 2023 Let’s take a look at 5 common theory test questions that everyone will have to

WHY PEOPLE FAIL THEORY TEST

Why people Fail Theory Test in UK updated article There are many reasons why people fail the theory test in the UK. Here

Test4Theory © 2018-2024 All rights Reserved.

Email: [email protected]

Terms and Conditions

Privacy policy.

- Practical Test Tutorials

- Theory Test Questions

- Hazard Perception Test

- Show Me, Tell Me Test

- UK Road Signs

- After The Test

- ADI Web Design

Theory Test Case Study

A case study represents a driving scenario. You will need to read the case study and then answer five questions based on it.

A case study represents a driving scenario. You will need to read the case study and then answer five questions based on it. The questions test whether you have truly understood and can apply the driving theory knowledge in a practical and typical driving situation.

Case Study Example

You are going to visit your cousin who lives in the next town. You have a road atlas in your car although you have been before and know the route really well. You also have your mobile phone and have promised to call your cousin if you get delayed. On the way you find that a country lane you usually travel on is flooded and decide to turn back.

Qu.1 You are on a country lane and see that it is flooded ahead. How can you judge the depth of water? Choose one answer.

A. park at the roadside and wait for another vehicle to drive through

B. drive through slowly and keep checking through the side window

C. look for a depth gauge at then roadside

D. get out of your vehicle and wade in

Correct answer: C

Qu.2 You find that you can't judge the depth of the water so you decide to turn around. The road is quite narrow. The best method of turning would be: Choose one answer.

A. to give a signal and make a quick U-turn

B. turn around in the road using forward and reverse gears

C. reverse back down the country lane until you find a farm entrance to turn into

D. drive slowly forward to a wider section of road to turn around in.

Correct answer: B

Qu.3 You have turned around on the narrow country lane because you can't follow your usual route. The best thing to do to find a new route would be to: Choose one answer.

A. call you cousin to ask for directions as you drive back towards the main road

B. drive on slowly whilst checking your road atlas

C. find a safe place to pull in and consult your road atlas

D. wait until you are back on the main road before calling your cousin for help

Qu.4 On the way back to the main road you are delayed by a slow-moving farm vehicle ahead. You are worried about being late and should: Choose one answer.

A. sound your horn so the driver of the farm vehicle will get out of your way

B. follow the farm vehicle closely so you can overtake at the earliest opportunity

C. pull out to overtake even though the road is very narrow

D. keep well back from the farm vehicle so you can see well ahead

Correct answer: D

Qu.5 You decide to let your cousin know that you will be late. You should: Choose one answer.

A. find a safe place to pull in and make a call on your mobile phone

B. rely on your hands-free kit to keep you safe whilst you make a call

C. stop and get out of your car to make the call

D. drive slowly and send a text message to your cousin

Correct answer: A

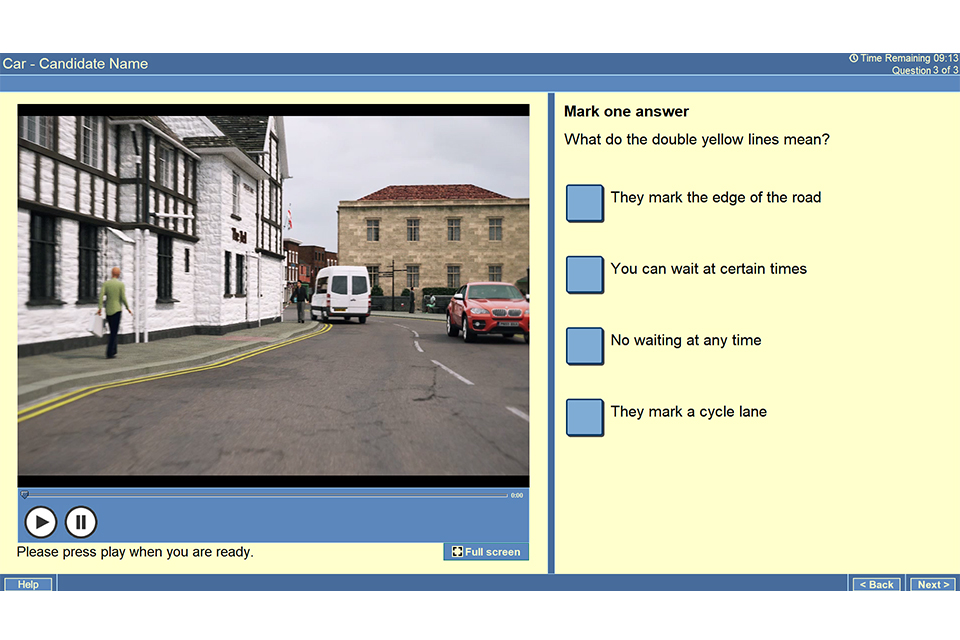

The image below shows you how the question will appear when you actually take the theory test.

- Latest Driving Test News

- Are You Ready To Drive

- Your Provisional License

- Instructor Code of Practice

- Your First Few Lessons

- Women Instructors

- Watch for Illegal Driving Instructors

- Learning with Family/Friends

- Driving an Automatic

- Driving Age Rumours

- History of the Driving Test

- Residential Courses

- Northern England

- Middle England

- Southern England

- Why we drive on the left

- Planning to Ride a Motorcycle

- Planning to drive a Lorry or Bus

- How to become a Driving Instructor

- Ways to Renew your licence at 70

- Theory Test FAQ

- Hazard Test FAQ

- What is HTP?

- 2Pass HTP Video Clip

- Ways to book your Theory Test

- Free Trial Hazard Perception Test

- Free Theory Test Question Samples

- Free Traffic Sign Test

- Free Motorway Test

- Theory Test PC Software

- Theory Test Instant Downloads

- Case Study Questions

- Overcome Your Test Nerves

- First Aid On The Road

- Theory Quizzes

- Tackle Recent Test Changes

- Practical Test FAQ

- Lots of Video Lessons

- Download Driving Test Routes

- Book Your Practical Test

- Practical Test Day

- Overcome Test Nerves

- Your Instructor On Test Day

- New Tell Me Questions

- New Show Questions

- Independent Driving on Test Day

- Your Driving Test in Bad Weather

- Driving Tests Around the World

- Situation Awareness

- Dashboard Warning Lights

- Cockpit Drill

- Changing Gears

- Hill Starts

- Pull up on the right and reverse

- The Turn In The Road

- Reverse Around Corner

- Parallel Parking

- Bay Parking

- Emergency Stops

- Roundabouts

- Approach 'T' Junctions

- Right Turns

- Pedestrian Crossings

- Box Juntions

- Stopping Distances

- Driving Alone

- Driving in Fog

- Driving in Snow

- Driving in Floods

- Driving on Motorways

- Aquaplaning

- Aggressive Drivers

- Road Accident

- Crash for Cash Scams

- Emergency Vehicles

- Test Nightmares

- Failures Top 10

- Eco-Driving

- Shoes for Driving

- 6 Penalty Points Law

- How to Stay Safe on the Road

- Using 'P' Plates

- Seat Belt Laws for Kids

- New Drivers Who Offend

- Advanced Driving

- Buying a Used Car

- Top 10 Cars for Sale

- Selling a Car

- Vehicle Data Check for £3

- Finance your first car

- Insurance Advice

- Cheap Insurance Quotes

- Breakdown and Recovery

- Purchasing a Number Plate

- Dealing with an Accident

- General Car Maintenance

- Learn to drive a Lorry / Bus

- Becoming an ADI

- Free Trial Online Theory Test

- Hazard Perception Test Download

- Car Theory Test Download

- Motorcycle Theory Test Download

- LGV/PCV Theory Test Download

- ADI Theory Test Download

- ------------------------

- Car online Revision

- Motorcycle online Revision

- LGV/PCV online Revision

- ADI/PDI online Revision

- eBooks (pdf format)

- Buy Learner Driver Insurance

- Insurance for Car Drivers

- Insurance for Motorcycle Riders

- Insurance for Van Drivers

- Temporary Car Insurance

- Bicycle Insurance

- Book your Theory Test

- Free Theory Test Samples - Car

- Free Theory Test Samples - Motorcycle

- Free Theory Test Samples - LGV/PCV

- Mock Traffic Sign Test

- Mock Motorway Test

- Free Mock Hazard Perception test

- Theory Test Software

- Theory Test Downloads

- Theory Test Books

- Theory Touchscreen Computer

Case Study Questions for the Theory Test

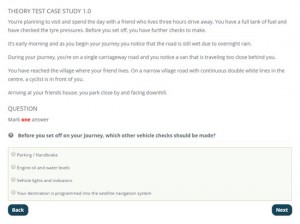

Are you ready for the new style theory test, the case study questions scenario below is no longer used on the theory test since 28th september 2020.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Theory test changes: 28 September 2020

From 28 September 2020, the car theory test will include 3 multiple-choice questions based on a short video you'll watch.

The way the theory test works in England, Scotland and Wales will change from 28 September 2020.

The same changes will apply in Northern Ireland .

The change will make the theory test more accessible, especially to people with a:

- reading difficulty (like dyslexia)

- learning disability

- developmental condition (like autism)

The change only applies to car theory tests to begin with.

This change was due to happen on 14 April 2020 but was postponed due to coronavirus.

How the theory test is changing to use video clips instead of written case studies

Currently, you have to read a case study and then answer 5 questions about it.

This tests your knowledge and understanding of road rules.

This will change if you take your test from 28 September 2020. You’ll watch one video clip instead of reading a case study, and answer 3 questions about it.

How using a video clip will work

You’ll watch a short, silent, video clip and answer 3 multiple-choice questions about it.

You can watch the video clip as many times as you like during the multiple-choice part of the theory test.

Example You can watch the video, answer a question, and then watch the video again before you answer the next question.

What the video clip will look like

The video clip will show a situation, such as driving through a town centre, or driving on a country road.

Car theory test video clips from 28 September 2020: example clip

The type of questions you’ll answer about the video clip

You’ll answer questions like these:

- Why are motorcyclists considered vulnerable road users?

- Why should the driver, on the side road, look out for motorcyclists at junctions?

- In this clip, who can cross the chevrons to overtake other vehicles, when it’s safe to do so?

For each of the 3 questions, you’ll have to choose the correct answer from 4 possible answers.

What the screen will look like

The left-hand side of the screen will show the video clip, with controls to:

- play the video

- pause the video

- move to a specific part of the video on a progress bar

- watch the video using the full screen

The right-hand side of the screen will show the question and 4 possible answers.

Who this change will affect

All car theory tests will use video clips from 28 September 2020.

This includes if:

- you fail a test before then and retake if from 28 September 2020

- your test is cancelled or moved for any reason, and your new test date is from 28 September 2020

What’s not changing

You’ll still need to study the same books and software to prepare for your theory test.

You’ll still need to:

- answer 50 multiple-choice questions within 57 minutes

- get 43 out of the 50 questions right to pass the multiple-choice part of the test

The hazard perception part of the test is not changing. This is where you watch video clips to spot developing hazards.

Tests that are not changing

The change does not yet apply to these types of theory tests:

- bus or coach

- approved driving instructor (ADI) part 1

Other support for people with a reading difficulty, disability or health condition

You can have reasonable adjustments made to your theory test if you have a:

- reading difficulty

- health condition

These include:

- extra time to take the test

- someone to read what’s on the screen and record your answers

- someone to reword the questions for you

Share this page

The following links open in a new tab

- Share on Facebook (opens in new tab)

- Share on Twitter (opens in new tab)

Updates to this page

Related content, is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

PCV CPC Module 2 Case Studies

Grace, a driver of a city transit bus in the UK, regularly transports a diverse group of passengers. She has received basic first aid training and is familiar with the first aid kit on her bus. Grace knows the importance of quickly and safely responding to medical emergencies, such as falls, sudden illnesses, or injuries among passengers. She is prepared to assess danger, provide first aid using the ‘DR ABC’ approach, and handle specific situations like shock, burns, and electric shock, maintaining passenger safety until professional medical help arrives.

PCV CPC Case Study 171

There are 7 multiple choice questions in this PCV CPC case study. Read this carefully and ensure you fully understand the scenario before starting the test. You need to score 6 out of 7 to pass.

Sign up to keep track of your progress

Your Progress

You're doing well! Carry on practising to make sure you're prepared for your test. You'll soon see your scores improve!

Tests Taken

Average Score

Do you wish to proceed?

2605 votes - average 4.8 out of 5

PCV CPC Case Studies

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Usability testing

Run remote usability tests on any digital product to deep dive into your key user flows

- Product analytics

Learn how users are behaving on your website in real time and uncover points of frustration

- Research repository

A tool for collaborative analysis of qualitative data and for building your research repository and database.

- Trymata Blog

How-to articles, expert tips, and the latest news in user testing & user experience

- Knowledge Hub

Detailed explainers of Trymata’s features & plans, and UX research terms & topics

- Plans & Pricing

Get paid to test

- User Experience (UX) testing

- User Interface (UI) testing

- Ecommerce testing

- Remote usability testing

- Plans & Pricing

- Customer Stories

How do you want to use Trymata?

Conduct user testing, desktop usability video.

You’re on a business trip in Oakland, CA. You've been working late in downtown and now you're looking for a place nearby to grab a late dinner. You decided to check Zomato to try and find somewhere to eat. (Don't begin searching yet).

- Look around on the home page. Does anything seem interesting to you?

- How would you go about finding a place to eat near you in Downtown Oakland? You want something kind of quick, open late, not too expensive, and with a good rating.

- What do the reviews say about the restaurant you've chosen?

- What was the most important factor for you in choosing this spot?

- You're currently close to the 19th St Bart station, and it's 9PM. How would you get to this restaurant? Do you think you'll be able to make it before closing time?

- Your friend recommended you to check out a place called Belly while you're in Oakland. Try to find where it is, when it's open, and what kind of food options they have.

- Now go to any restaurant's page and try to leave a review (don't actually submit it).

What was the worst thing about your experience?

It was hard to find the bart station. The collections not being able to be sorted was a bit of a bummer

What other aspects of the experience could be improved?

Feedback from the owners would be nice

What did you like about the website?

The flow was good, lots of bright photos

What other comments do you have for the owner of the website?

I like that you can sort by what you are looking for and i like the idea of collections

You're going on a vacation to Italy next month, and you want to learn some basic Italian for getting around while there. You decided to try Duolingo.

- Please begin by downloading the app to your device.

- Choose Italian and get started with the first lesson (stop once you reach the first question).

- Now go all the way through the rest of the first lesson, describing your thoughts as you go.

- Get your profile set up, then view your account page. What information and options are there? Do you feel that these are useful? Why or why not?

- After a week in Italy, you're going to spend a few days in Austria. How would you take German lessons on Duolingo?

- What other languages does the app offer? Do any of them interest you?

I felt like there could have been a little more of an instructional component to the lesson.

It would be cool if there were some feature that could allow two learners studying the same language to take lessons together. I imagine that their screens would be synced and they could go through lessons together and chat along the way.

Overall, the app was very intuitive to use and visually appealing. I also liked the option to connect with others.

Overall, the app seemed very helpful and easy to use. I feel like it makes learning a new language fun and almost like a game. It would be nice, however, if it contained more of an instructional portion.

All accounts, tests, and data have been migrated to our new & improved system!

Use the same email and password to log in:

Legacy login: Our legacy system is still available in view-only mode, login here >

What’s the new system about? Read more about our transition & what it-->

What is a Case Study? Definition, Research Methods, Sampling and Examples

Conduct End-to-End User Testing & Research

What is a Case Study?

A case study is defined as an in-depth analysis of a particular subject, often a real-world situation, individual, group, or organization.

It is a research method that involves the comprehensive examination of a specific instance to gain a better understanding of its complexities, dynamics, and context.

Case studies are commonly used in various fields such as business, psychology, medicine, and education to explore and illustrate phenomena, theories, or practical applications.

In a typical case study, researchers collect and analyze a rich array of qualitative and/or quantitative data, including interviews, observations, documents, and other relevant sources. The goal is to provide a nuanced and holistic perspective on the subject under investigation.

The information gathered here is used to generate insights, draw conclusions, and often to inform broader theories or practices within the respective field.

Case studies offer a valuable method for researchers to explore real-world phenomena in their natural settings, providing an opportunity to delve deeply into the intricacies of a particular case. They are particularly useful when studying complex, multifaceted situations where various factors interact.

Additionally, case studies can be instrumental in generating hypotheses, testing theories, and offering practical insights that can be applied to similar situations. Overall, the comprehensive nature of case studies makes them a powerful tool for gaining a thorough understanding of specific instances within the broader context of academic and professional inquiry.

Key Characteristics of Case Study

Case studies are characterized by several key features that distinguish them from other research methods. Here are some essential characteristics of case studies:

- In-depth Exploration: Case studies involve a thorough and detailed examination of a specific case or instance. Researchers aim to explore the complexities and nuances of the subject under investigation, often using multiple data sources and methods to gather comprehensive information.

- Contextual Analysis: Case studies emphasize the importance of understanding the context in which the case unfolds. Researchers seek to examine the unique circumstances, background, and environmental factors that contribute to the dynamics of the case. Contextual analysis is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions and generalizing findings to similar situations.

- Holistic Perspective: Rather than focusing on isolated variables, case studies take a holistic approach to studying a phenomenon. Researchers consider a wide range of factors and their interrelationships, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of the case. This holistic perspective helps in providing a more complete understanding of the subject.

- Qualitative and/or Quantitative Data: Case studies can incorporate both qualitative and quantitative data, depending on the research question and objectives. Qualitative data often include interviews, observations, and document analysis, while quantitative data may involve statistical measures or numerical information. The combination of these data types enhances the depth and validity of the study.

- Longitudinal or Retrospective Design: Case studies can be designed as longitudinal studies, where the researcher follows the case over an extended period, or retrospective studies, where the focus is on examining past events. This temporal dimension allows researchers to capture changes and developments within the case.

- Unique and Unpredictable Nature: Each case study is unique, and the findings may not be easily generalized to other situations. The unpredictable nature of real-world cases adds a layer of authenticity to the study, making it an effective method for exploring complex and dynamic phenomena.

- Theory Building or Testing: Case studies can serve different purposes, including theory building or theory testing. In some cases, researchers use case studies to develop new theories or refine existing ones. In others, they may test existing theories by applying them to real-world situations and assessing their explanatory power.

Understanding these key characteristics is essential for researchers and practitioners using case studies as a methodological approach, as it helps guide the design, implementation, and analysis of the study.

Key Components of a Case Study

A well-constructed case study typically consists of several key components that collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation. Here are the key components of a case study:

- Provide an overview of the context and background information relevant to the case. This may include the history, industry, or setting in which the case is situated.

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define what the study aims to achieve and the questions it seeks to answer.

- Clearly identify the subject of the case study. This could be an individual, a group, an organization, or a specific event.

- Define the boundaries and scope of the case study. Specify what aspects will be included and excluded from the investigation.

- Provide a brief review of relevant theories or concepts that will guide the analysis. This helps place the case study within the broader theoretical context.

- Summarize existing literature related to the subject, highlighting key findings and gaps in knowledge. This establishes the context for the current case study.

- Describe the research design chosen for the case study (e.g., exploratory, explanatory, descriptive). Justify why this design is appropriate for the research objectives.

- Specify the methods used to gather data, whether through interviews, observations, document analysis, surveys, or a combination of these. Detail the procedures followed to ensure data validity and reliability.

- Explain the criteria for selecting the case and any sampling considerations. Discuss why the chosen case is representative or relevant to the research questions.

- Describe how the collected data will be coded and categorized. Discuss the analytical framework or approach used to identify patterns, themes, or trends.

- If multiple data sources or methods are used, explain how they complement each other to enhance the credibility and validity of the findings.

- Present the key findings in a clear and organized manner. Use tables, charts, or quotes from participants to illustrate the results.

- Interpret the results in the context of the research objectives and theoretical framework. Discuss any unexpected findings and their implications.

- Provide a thorough interpretation of the results, connecting them to the research questions and relevant literature.

- Acknowledge the limitations of the study, such as constraints in data collection, sample size, or generalizability.

- Highlight the contributions of the case study to the existing body of knowledge and identify potential avenues for future research.

- Summarize the key findings and their significance in relation to the research objectives.

- Conclude with a concise summary of the case study, its implications, and potential practical applications.

- Provide a complete list of all the sources cited in the case study, following a consistent citation style.

- Include any additional materials or supplementary information, such as interview transcripts, survey instruments, or supporting documents.

By including these key components, a case study becomes a comprehensive and well-rounded exploration of a specific subject, offering valuable insights and contributing to the body of knowledge in the respective field.

Sampling in a Case Study Research

Sampling in case study research involves selecting a subset of cases or individuals from a larger population to study in depth. Unlike quantitative research where random sampling is often employed, case study sampling is typically purposeful and driven by the specific objectives of the study. Here are some key considerations for sampling in case study research:

- Criterion Sampling: Cases are selected based on specific criteria relevant to the research questions. For example, if studying successful business strategies, cases may be selected based on their demonstrated success.

- Maximum Variation Sampling: Cases are chosen to represent a broad range of variations related to key characteristics. This approach helps capture diversity within the sample.

- Selecting Cases with Rich Information: Researchers aim to choose cases that are information-rich and provide insights into the phenomenon under investigation. These cases should offer a depth of detail and variation relevant to the research objectives.

- Single Case vs. Multiple Cases: Decide whether the study will focus on a single case (single-case study) or multiple cases (multiple-case study). The choice depends on the research objectives, the complexity of the phenomenon, and the depth of understanding required.

- Emergent Nature of Sampling: In some case studies, the sampling strategy may evolve as the study progresses. This is known as theoretical sampling, where new cases are selected based on emerging findings and theoretical insights from earlier analysis.

- Data Saturation: Sampling may continue until data saturation is achieved, meaning that collecting additional cases or data does not yield new insights or information. Saturation indicates that the researcher has adequately explored the phenomenon.

- Defining Case Boundaries: Clearly define the boundaries of the case to ensure consistency and avoid ambiguity. Consider what is included and excluded from the case study, and justify these decisions.

- Practical Considerations: Assess the feasibility of accessing the selected cases. Consider factors such as availability, willingness to participate, and the practicality of data collection methods.

- Informed Consent: Obtain informed consent from participants, ensuring that they understand the purpose of the study and the ways in which their information will be used. Protect the confidentiality and anonymity of participants as needed.

- Pilot Testing the Sampling Strategy: Before conducting the full study, consider pilot testing the sampling strategy to identify potential challenges and refine the approach. This can help ensure the effectiveness of the sampling method.

- Transparent Reporting: Clearly document the sampling process in the research methodology section. Provide a rationale for the chosen sampling strategy and discuss any adjustments made during the study.

Sampling in case study research is a critical step that influences the depth and richness of the study’s findings. By carefully selecting cases based on specific criteria and considering the unique characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation, researchers can enhance the relevance and validity of their case study.

Case Study Research Methods With Examples

- Interviews:

- Interviews involve engaging with participants to gather detailed information, opinions, and insights. In a case study, interviews are often semi-structured, allowing flexibility in questioning.

- Example: A case study on workplace culture might involve conducting interviews with employees at different levels to understand their perceptions, experiences, and attitudes.

- Observations:

- Observations entail direct examination and recording of behavior, activities, or events in their natural setting. This method is valuable for understanding behaviors in context.

- Example: A case study investigating customer interactions at a retail store may involve observing and documenting customer behavior, staff interactions, and overall dynamics.

- Document Analysis:

- Document analysis involves reviewing and interpreting written or recorded materials, such as reports, memos, emails, and other relevant documents.

- Example: In a case study on organizational change, researchers may analyze internal documents, such as communication memos or strategic plans, to trace the evolution of the change process.

- Surveys and Questionnaires:

- Surveys and questionnaires collect structured data from a sample of participants. While less common in case studies, they can be used to supplement other methods.

- Example: A case study on the impact of a health intervention might include a survey to gather quantitative data on participants’ health outcomes.

- Focus Groups:

- Focus groups involve a facilitated discussion among a group of participants to explore their perceptions, attitudes, and experiences.

- Example: In a case study on community development, a focus group might be conducted with residents to discuss their views on recent initiatives and their impact.

- Archival Research:

- Archival research involves examining existing records, historical documents, or artifacts to gain insights into a particular phenomenon.

- Example: A case study on the history of a landmark building may involve archival research, exploring construction records, historical photos, and maintenance logs.

- Longitudinal Studies:

- Longitudinal studies involve the collection of data over an extended period to observe changes and developments.

- Example: A case study tracking the career progression of employees in a company may involve longitudinal interviews and document analysis over several years.

- Cross-Case Analysis:

- Cross-case analysis compares and contrasts multiple cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences.

- Example: A comparative case study of different educational institutions may involve analyzing common challenges and successful strategies across various cases.

- Ethnography:

- Ethnography involves immersive, in-depth exploration within a cultural or social setting to understand the behaviors and perspectives of participants.

- Example: A case study using ethnographic methods might involve spending an extended period within a community to understand its social dynamics and cultural practices.

- Experimental Designs (Rare):

- While less common, experimental designs involve manipulating variables to observe their effects. In case studies, this might be applied in specific contexts.

- Example: A case study exploring the impact of a new teaching method might involve implementing the method in one classroom while comparing it to a traditional method in another.

These case study research methods offer a versatile toolkit for researchers to investigate and gain insights into complex phenomena across various disciplines. The choice of methods depends on the research questions, the nature of the case, and the desired depth of understanding.

Best Practices for a Case Study in 2024

Creating a high-quality case study involves adhering to best practices that ensure rigor, relevance, and credibility. Here are some key best practices for conducting and presenting a case study:

- Clearly articulate the purpose and objectives of the case study. Define the research questions or problems you aim to address, ensuring a focused and purposeful approach.

- Choose a case that aligns with the research objectives and provides the depth and richness needed for the study. Consider the uniqueness of the case and its relevance to the research questions.

- Develop a robust research design that aligns with the nature of the case study (single-case or multiple-case) and integrates appropriate research methods. Ensure the chosen design is suitable for exploring the complexities of the phenomenon.

- Use a variety of data sources to enhance the validity and reliability of the study. Combine methods such as interviews, observations, document analysis, and surveys to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Clearly document and describe the procedures for data collection to enhance transparency. Include details on participant selection, sampling strategy, and data collection methods to facilitate replication and evaluation.

- Implement measures to ensure the validity and reliability of the data. Triangulate information from different sources to cross-verify findings and strengthen the credibility of the study.

- Clearly define the boundaries of the case to avoid scope creep and maintain focus. Specify what is included and excluded from the study, providing a clear framework for analysis.

- Include perspectives from various stakeholders within the case to capture a holistic view. This might involve interviewing individuals at different organizational levels, customers, or community members, depending on the context.

- Adhere to ethical principles in research, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality, and addressing any potential conflicts of interest.

- Conduct a rigorous analysis of the data, using appropriate analytical techniques. Interpret the findings in the context of the research questions, theoretical framework, and relevant literature.

- Offer detailed and rich descriptions of the case, including the context, key events, and participant perspectives. This helps readers understand the intricacies of the case and supports the generalization of findings.

- Communicate findings in a clear and accessible manner. Avoid jargon and technical language that may hinder understanding. Use visuals, such as charts or graphs, to enhance clarity.

- Seek feedback from colleagues or experts in the field through peer review. This helps ensure the rigor and credibility of the case study and provides valuable insights for improvement.

- Connect the case study findings to existing theories or concepts, contributing to the theoretical understanding of the phenomenon. Discuss practical implications and potential applications in relevant contexts.

- Recognize that case study research is often an iterative process. Be open to revisiting and refining research questions, methods, or analysis as the study progresses. Practice reflexivity by acknowledging and addressing potential biases or preconceptions.

By incorporating these best practices, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their case studies, making valuable contributions to the academic and practical understanding of complex phenomena.

Interested in learning more about the fields of product, research, and design? Search our articles here for helpful information spanning a wide range of topics!

Mobile Application Testing Process for Better User Experience

How to write a case study after usability testing, case study advantages and disadvantages in usability testing, transforming usability testing through case study interview.

- Sign into My Research

- Create My Research Account

- Company Website

- Our Products

- About Dissertations

- Español (España)

- Support Center

Select language

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português (Brasil)

- Português (Portugal)

Welcome to My Research!

You may have access to the free features available through My Research. You can save searches, save documents, create alerts and more. Please log in through your library or institution to check if you have access.

Translate this article into 20 different languages!

If you log in through your library or institution you might have access to this article in multiple languages.

Get access to 20+ different citations styles

Styles include MLA, APA, Chicago and many more. This feature may be available for free if you log in through your library or institution.

Looking for a PDF of this document?

You may have access to it for free by logging in through your library or institution.

Want to save this document?

You may have access to different export options including Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive and citation management tools like RefWorks and EasyBib. Try logging in through your library or institution to get access to these tools.

- Document 1 of 1

- More like this

- Scholarly Journal

Theory Testing Using Case Studies

No items selected.

Please select one or more items.

Select results items first to use the cite, email, save, and export options

Abstract: The appropriateness of case studies as a tool for theory testing is still a controversial issue, and discussions about the weaknesses of such research designs have previously taken precedence over those about its strengths. The purpose of the paper is to examine and revive the approach of theory testing using case studies, including the associated research goal, analysis, and generalisability. We argue that research designs for theory testing using case studies differ from theory-building case study research designs because different research projects serve different purposes and follow different research paths.

Keywords: Case studies, theory testing, research paths

1. Introduction

Research based on case studies can take many forms. Case study research can depart in a positivist or interpretivist approach, it can be deductive or inductive, and it can rely on qualitative or quantitative methods. It can also be a mix of these extremes (Cavaye 1996). Using case studies is, however, still perceived as a less conventional manner of testing theories in many research communities (Cavaye 1996). This is so regardless of the fact that research capacities already in the 1970s made the following propositions: '[c]ase studies... are valuable at all stages of the theory building process, but most valuable at that stage of theory building where least value is generally attached to them: the stage at which candidate theories are "tested"' (Eckstein 1975: 80); and that case studies are useful 'particularly to examine a single exception that shows the hypothesis to be false' (Stake 1978: 7).

Today, we propose that case studies are still an overlooked source of theory refinement and development. Extending the value of case studies to that of theory development within a larger research programme is regrettably still a contested issue.

A research design based on case studies as a means for testing theories has not previously been examined comprehensively. Often the weaknesses of such research designs have taken precedence over reflections about its strengths. In this paper, we approach the debate from a different stance, arguing that case studies can indeed be a valuable tool for testing theories.

Thus, the purpose of the paper is to examine theory testing using case studies, including the associated research goal, analysis, and generalisability. In this respect, it is argued that the research design for theory testing using case studies differs from the design of theory building using case studies because different research projects serve different purposes and follow different research paths.

To promote the argument, we revitalise the notions of both 'testing' and 'theories' in a wider sense than is usually done. We suggest two specific research paths that serve as structured and legitimate frameworks for thinking about case research designs for theory testing. Finally, we elaborate on what consequences theory testing using case studies has on different elements of a research design, in particular the generalisability issues.

2. Theoretical Research Paths for Case Studies

Research based on a case study focuses on a single setting or unit that is spatially and temporally bounded (Eisenhardt 1989, Van Maanen 1979). Sometimes it can be difficult to specify where the case ends and the environment begins, but here boundedness, contexts, and experience can be useful concepts (Stake 2006).

Overall, the advantage of a case study is that it 'can "close-in" on real-life situations and test views directly in relation to phenomena as they unfold in practice' (Flyvbjerg 2004: 428).

Each case can contain embedded cases (Yin 2014). The essence of a case study is the case, understood as the choice of study object(s) and the framing of these (Stake 2000). In principle, any technique for collecting data is applicable, even if case studies are often mistakenly presented as a qualitative method (Eisenhardt 1989).

Case studies may serve different research goals (Maxwell 2005). For instance, Eisenhardt (1989) specifies three such goals: description, theory testing, and theory generation. The connection between elements in the research design is ensured by a research strategy (Maxwell 2005), which becomes 'a way of linking ideas and evidence to produce a representation of some aspect of social life' (Ragin 1994: 48).

Brinberg and McGrath (1985) suggest that research paths progress through three different domains: a substantive 'real-world' domain (S), a conceptual domain (C), and a methodological domain (M). Each domain can be a starting point for conducting research, and any study covers all three domains. Mapping out a research strategy thus starts with the choice of the primary domain of interest, then the second domain, and, finally, the third domain. The domains are interrelated and the researcher works iteratively between them, so the presentation in the following is a representation and not a cookbook recipe. Being clear about a study's starting point benefits researchers because it promotes the understanding of the study itself and gives an overview, as well as helps in expressing its results and contributions to a research programme.

For our purpose, we are interested in the type of research path that Brinberg and McGrath (1985) identify as a theoretical path leading to an end product of tested hypotheses. While many case studies take their starting point in the substantive domain, a theoretical research path also describes a situation where a study focuses on the conceptual domain and in which the cases are instrumental to the theoretical contribution. Theoretical paths are thus either concept-driven or system-driven (Brinberg and McGrath 1985). While we focus mainly on concept-driven paths in the following, the outcome of the two paths may appear similar, cf. Figure 1.

Concept-driven theoretical paths focus on understanding the explanation(s) underlying a phenomenon (Brinberg and McGrath 1985). Such a research path matches a research design built on, for instance, rival theories, a design in which multiple theories are compared in order to assess their relative value in terms of strengths, weaknesses, boundaries, and other relevant dimensions. Examples of research questions to this path could be 'Is the original theory correct? Does the original theory fit other circumstances? Are there additional categories or relationships?' (Crabtree and Miller 1999: 7).

System-driven theoretical paths focus on understanding an empirical system (Brinberg and McGrath 1985). For a system-driven theoretical path, we suggest a matching theory-testing case study research design using multiple theories to examine the system from different angles (triangulation).

Similar conceptualisations have been denoted analytic induction (Patton 2002) and explanatory case studies (Yin 2014). However, analytic induction builds on cross-case analyses, and explanatory studies examine how a particular situation or event may be explained by one or more theories. Only to a lesser degree does the latter focus on the theory as such, and therefore explanatory studies represent system-driven theoretical study paths. We argue that both types are subsets of theory-testing studies.

The line between system-driven and concept-driven case studies is blurred and several purposes may be served within the same study. A classic example from political science is the advent of revolutions and wars (George and Bennett 2005). Here the variables come partly from the cases and partly from prior theoretical explanations.

3. The Role of Theory for Theoretical Research Paths

In order to discuss the role of theories for theoretical research paths (c.f. Brinberg and McGrath 1985), of which theory testing using case studies is an example, we need to define both the concept of theory and theory-testing.

In the literature theory is defined more or less accurately (Andersen and Kragh 2010) and is often mistakenly refered to as models and propositions (Sutton and Staw 1995). Doty and Click (1994) define theory as 'a series of logical arguments that specifies a set of relationships among concepts, constructs, or variables'. Such a definition allows for theories to be conceptualised at different levels - for instance, conceptual, construct, and variable levels. The purpose of theories is to explain why (Sutton and Staw 1995) - which again explains how. So, theories are explanations.

Theories as explanations are important for case studies in several ways (c.f. Walsham 1995). First, they are always present as the researcher's implicit and explicit understanding of what is going on with the studied phenomenon. With minor differences, this role of theory is referred to as 'conceptual context' (Maxwell 2005), 'conceptual domain' (Brinberg and McGrath 1985), or 'analytical frames' (Ragin 1994).

Second, theories explicitly provide analytical guidelines and serve as 'a heuristic for collecting and organising data' (Colville et al. 1999). In a theory-testing case study, the researcher specifies a priori to data collection the types and content of data to be collected. These a priori-specified data requirements are the minimum amount of data satisfying the analytical needs. Theories are a useful tool for handling the large amounts of data in case studies because '[scanning all variables is not the same as including all variables' (Lijphart 1971: 690).

Third, theories as an object of interest can be developed, modified, and tested using case studies and thus serve as both input and output to the study (Campbell 1975, Eckstein 1975, Yin 2014). Theories-as-object is the special focus when case studies are used for theory testing, which distinguishes them from other types of case studies.

In this sense, theories allow for a focus on key variables, leading to the required parsimony of analysis. Thus, when the purpose of a case study is theory testing, not only in-depth knowledge of the case(s) and the methods is needed, but also knowledge of the theories involved.

Consider the meaning and implications of the terms 'test' and 'testing'. Many researchers seem to think of testing in a narrow sense: a specified and near-conclusive procedure for falsification or verification. We rely on a more inclusive definition. For instance, Crabtree and Miller specifically state that the goal of theory testing is 'to test explanatory theory by evaluating it in different contexts' (1999: 7). Likewise, Yin (2014) argues that theory testing is a matter of external validity and can be seen as the replication of case studies with the purpose of identifying whether previous results extend to new cases.

When a researcher conducts a theory test, then propositions, i.e., logical conclusions or predictions, are derived from the theory and are compared to observations, or data, in the case (Cavaye 1996). The more often and the more conclusively the theory is confirmed, the more faith in that the theory reflects reality (Cavaye 1996).

Theory testing is in contrast to theory-building case studies, where the latter are defined as 'the process through which researchers seek to make sense of the observable world by conceptualizing, categorizing and ordering relationships among observed elements' (Andersen and Kragh 2010). The case plays a different role whether it is used for theory testing or theory building, c.f. Figure 2. In theory testing using case studies, propositions are selected and articulated beforehand, as well as used dynamically in all other phases of the research process. The role of the case thus becomes instrumental, meaning that '[t]he case is of secondary interest, it plays a supportive role, and it facilitates our understanding of something else' (Stake 2000: 437).

The contributions from theory testing case studies can be diverse '...to strengthen or reduce support for a theory, narrow or extend the scope conditions of a theory, or determine which of two or more theories best explains a case, type, or general phenomenon' (George and Bennett 2005: 109). The classical study of theory testing using a case study is Allison's (1971) application of three different decision-making perspectives in the analysis of the Cuban Missile Crisis, but we find other types where case studies have been used for theory testing (e.g., Argyris 1979, Pinfield 1986, Jobber and Lucas 2000, Trochim 1985, Jauch et al. 1980, Brown 1999, Lee et al. 1996).

4. Theory Testing Case Study Design

When a researcher decides on theory testing using case studies, it affects different elements of a research design, as summarised in Table 1. A researcher doing a theory testing case study spends relatively more time preparing for data collection and analysis, making extant theories explicit and setting up the analytical framework.

4.1 Research goals

Consistent with the concept-driven theoretical path, testing of competing theories may be a research goal in itself. The competing perspectives approach aims to rule out less effective explanations, often looking for the one explanation that best explains a phenomenon, or to establish the boundaries of a theory's application.

The system-driven theoretical path is equivalent to theory triangulation. Comparing complementary theories is a form of triangulation (Brinberg and McGrath 1985): 'The point... is to understand how differing assumptions and premises affect findings and interpretations' (Patton 2002: 562). The complementary perspective thus sees each theory as contributing to understanding.

Identifying the relevant theories to include in a case study is a selection process: In some cases, the choice of theories to be included is unproblematic. In other instances, it may be difficult to distinguish distinct theories within a field, especially when a research field is emerging and everybody is trying to break new ground. Such diversity is one reason why theory testing using case studies is relevant, since the literature must be systematised prior to data collection.

4.2 Pre-data collection work on theories

Prior to data collection, theories are 'operationalised' in terms of the minimum data requirements and propositions to be matched with empirical data, thus addressing construct validity. Several levels and elements of the same theory, or rather the pattern that the theory constitutes, can be evaluated through multiple propositions and multiple theories because of the amount of data from the case study (Campbell 1975).

4.3 Analysis

Analytically, in-depth knowledge of theories facilitates moving from emic to etic accounts of a phenomenon. Ernie conceptualisations are those given by case informants, while etic conceptualisations are researchers' interpretations (Maxwell 2005). In terms of specific analytical techniques, Campbell (1975) suggested degrees- of-freedom analysis, which has been exemplified by, for example, Wilson and Woodside (1999). Ragin and co- workers (Ragin 1994) have developed techniques for analysing both crisp and fuzzy case data sets. Knowledge of prior theory also has potential risks. If, for instance, a researcher is too emotionally attached to certain explanations, (s)he runs the risk of ignoring conflicting information. Rival explanations might be a way of mitigating such a risk. However, knowledge of prior theory can also be argued to free 'mental' resources to look for alternative explanations and elements. Researchers will have excess information processing capacity to include additional thought experiments and iterations between theory and data (c.f. Campbell 1975), because familiar information can be processed faster and with less basic analytical work.

4.4 Validity and generalisation

The majority of the methodological literature describes quantitative and qualitative studies as associated with generalisation and particularisation, respectively. The result is that notions of theory testing, which are associated with generalisation purposes, in small-N studies, which are associated with particularisation purposes, are controversial topics in many research communities. Such scepticism includes theory testing using case studies. In a case study design, however, the methods applied for data collection do not determine whether the purpose is generalisation or particularisation. Therefore, the assumption that case studies cannot be applied for generalisation purposes is questionable.

Still, there are different views as to whether generalisations from case studies are possible. Some claim that inference is possible (e.g., Yin), whereas others reject this (e.g., Stake, Kennedy, Lincoln & Cuba) and argue that readers of case study reports are themselves responsible for whether there can be a 'transferability' of findings from one situation to another (Gomm et al. 2000).

Yin (2014) considers the case as an experiment and claims that case studies can lead to analytic generalisations, Le., a generalisation on a conceptual higher level than the case. Such analytical generalisation is based on 'a) corroborating, modifying, rejecting, or otherwise advancing theoretical concepts that you referenced in designing your case study or b) new concepts that arose upon the completion of your case study' (Yin 2014: 40). Thus, according to Yin, a case study is generalisable to theoretical propositions and not populations (Swanborn 2010: 66). Analytical generalisations involve a judgement about whether the findings of one study can be a guide to what occurs in another situation and include a comparison of the two situations (Brinkman and Kvale 2015).

Stake rejects a scientific induction from case studies but talks about a naturalistic generalizability which is developed within people based on their experience (Stake 1978, 1995). Often these generalisations are not predictions, but rather lead to expectations (Stake 1978). 'They may become verbalized, passing of course from tacit knowledge to propositional; but they have not yet passed the empirical and logical tests that characterize formal (scholarly, scientific) generalizations' (Gomm et al. 2000).

Kennedy (1979) claims that generalisation is a judgment of degree. The researcher should produce and share the information, and after this the receiver judges whether the findings can be generalised to the receiver's situation. Here it is of course essential that the researcher makes a detailed description of the specific case characteristics, because s(he) does not know who the receivers are (Kennedy 1979).

The logic behind theory testing supports the idea of generalisation from prior studies and their outcomes to an actual study, and from an actual study to theories (Lee and Baskerville 2003, Yin 2014). Two assumptions are present here. First, verification in the sense of 'ultimately true' is not possible except for trivial facts (Lakatos 1970). Second, verification and falsification are not opposites. The opposite of falsification is confirmation or corroboration-words that more accurately denote the outcome, namely an ongoing process of theory testing and theory development.

In terms of internal validity, rival explanations can be included because: 'the more rivals that your analysis addresses and rejects, the more confidence you can place in your findings' (Yin 2003: 113). Explicit consideration of alternative explanations for findings increases the credibility of a study, and here we use the entire range of rival explanations, not just theories (see Yin 2000, 2003).

The pursuit of generalisations typically goes together with a search for causes (Stake 2006). It is often claimed that case studies contribute by giving the opportunity of identifying causalities because cases are examined deeply and longitudinal (Gomm et al. 2000). Unlike an experiment, cases 'investigate causal processes "in the real world" rather than in artificially created settings' (Gomm et al. 2000).

However, we know that case studies are useful when the phenomenon under investigation is complex. Such complexity has many faces and can be seen, for instance, when phenomena interrelate, occur at multiple levels of analysis (e.g., span individual and group levels), or when they can only be understood as embedded in a larger context.

If the phenomenon being studied is too complex, a search for 'simple' causalities, however, becomes hopeless.

Nevertheless, cases can be seen as manifestations of more general phenomena and therefore embody the essence of those phenomena (c.f. Becker 1998, Gerring 2004).

4.4.1 Sampling

Generalisation in theory-testing case studies is closely related to the issue of sampling. It is, however, not merely a function of the number of cases observed, but rather the range of characteristics of the units and the range of conditions occurred under observation (Kennedy 1979). 'The range of characteristics included in a sample increases the range of population characteristics to which generalization is possible' (Kennedy 1979).

In line with this, we suggest that the number of cases is considered from what is added from each new case in terms of analytical benefits. Figure 3 outlines the relationship between the number of theories and the number of cases. When the number of theories and their propositions or 'variables' to be tested is small, multiple case studies are an obvious choice to investigate the boundaries of those theories in different settings. As the number of theories to be evaluated grows, a single case study may yield more credibility in the findings, because all theories are evaluated against the same material. The 'efficiency boundary' represents the interaction points where a thorough analysis is feasible and credible. It may be shifted outwards if more researchers are involved in a study, or if a researcher has special skills, experience, or insights with respect to the cases or the theories, because the pooled information processing capacity is increased and more relationships between theory and data can be handled.

Besides choosing the number of cases, strategic or purposeful case selection is essential for generalisation (Flyvbjerg 2004). Theory testing using case studies relies by definition on theoretical sampling where cases are chosen on the basis of theoretical criteria (Eisenhardt 1989, Patton 2002, Wilson and Vlosky 1997). In addition, we rely on information-oriented selection where '[cjases are selected on the basis of expectations about their information content' (Flyvbjerg 2004: 426), i.e., their potential for learning (Stake 2000: 446). Diverging ideas prevail regarding the benefits of one or multiple cases relative to generalisation. Yin argues that more cases provide stronger conclusions (2014), while Stake claims 'conclusions from differences between any two cases are less to be trusted than conclusions about one' and argues that comparisons might impede learning from the particular (Stake 2000: 444). In short, the number and type of cases relative to generalisability depends upon research questions and goals.

5. Theory Development

Case studies contribute to the development and refinement of research programmes along with other types of research. Much methodological literature seems to favour the use of cases for descriptive and explorative purposes, that is, early in the development of a research field or a study. Case studies are, however, sources of learning throughout the progress of a larger research programme (Campbell 1975, Eckstein 1975). For instance, case studies add depth to understanding that may arise from completed large-N studies (Patton 2002), they illuminate mechanisms and relations (Gerring 2004), and, of course, they are unique for learning from the particular (Stake 2000).

Research programmes 'connect' researchers through series of related theories and have a 'hard core' of assumptions which are not questioned and a protective belt of auxiliary hypotheses (Lakatos 1970). Findings in theory testing using case studies will often be related to the protective belt, but as fundamentally different ('paradigmatic') theories are evaluated, outcomes may also be related to the hard core.

Critiques have been made against case studies for 'having a bias towards verification, understood as a tendency to confirm the researcher's preconceived notions' (Flyvbjerg 2004: 428). The risk of confirming existing ideas and beliefs does not, however, seem to be an observed problem in case study research. Researchers often report that they change or discharge their original ideas as they gain additional insights during a case study (c.f. Campbell 1975, Flyvbjerg 2004, Lee and Baskerville 2003).

So rather than seeing one piece of counterevidence (or one case) as falsification, we use Lakatos' distinction between naïve and sophisticated falsification. Lakatos (1970: 120) suggests: 'falsification is not simply a relation between a theory and the empirical basis, but a multiple relation between competing theories, the original "empirical basis", and the empirical growth resulting from the competition'.

Lakatos nuances the issue of falsification by introducing the notion of sophisticated falsification, in which 'a theory is "acceptable" or "scientific" only if it has corroborated excess empirical content over its predecessor (or rival), that is, only if it leads to the discovery of novel facts' (Lakatos 1970:116).

In comparison, naïve falsificationists, following a Popperian argument, claim that a theory can be falsified by an 'observational' conflicting statement. To sophisticated falsificationists, a theory is falsified if another theory is proposed, fulfilling the requirements mentioned. Naïve falsification is therefore not a sufficient condition for eliminating a theory: 'in spite of hundreds of known anomalies we do not regard it as falsified (that is, eliminated) until we have a better one' (Lakatos 1970: 121).

When results in case studies indicate falsification or anomalies, we have two options: Either to suggest a new theory within a different research programme (abandon the hard core), or to explain anomalies using auxiliary hypotheses (modify the protective belt). In this sense theory testing using case studies is valuable at any stage in the theory development process as long as it has a positive and progressive effect on a research programme.

6. Concluding Remarks