- Career Blog

Creating a Career Portfolio: A Step-by-Step Guide

In today’s competitive job market, having a solid career portfolio is no longer optional—it’s a necessity. A career portfolio is an organized collection of evidence that showcases your professional skills, accomplishments, and qualifications.

But what exactly is a career portfolio? A career portfolio can include a variety of items such as a resume, cover letters, reference letters, certifications, awards, and sample work. It is a visual representation of your career that goes beyond a simple resume to demonstrate to potential employers the depth and breadth of your experience.

So why is having a career portfolio so important? For starters, a career portfolio can help you stand out in the job market by showcasing your unique set of skills and accomplishments. It can also help you prepare for job interviews by giving you a comprehensive understanding of your own strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, a career portfolio can help you stay organized and focused on your career goals.

This article will provide you with a step-by-step guide on how to create a career portfolio that will help you stand out from other job applicants. Throughout the article, we will cover the following topics:

- Gathering materials for your career portfolio

- Choosing the right format for your career portfolio

- How to structure your career portfolio

- Tips for presenting your career portfolio

- Updating your career portfolio

By the end of this article, you will have a comprehensive understanding of what goes into creating a career portfolio, how to present it effectively, and how to keep it up to date.

Investing time in creating a career portfolio is an investment in your career. Not only will it help you land your dream job, but it will also help you stay focused on your professional goals and set you up for long-term success. So, let’s get started on creating your own career portfolio.

Step 1: Identify Your Goals and Target Audience

As you embark on the journey to create a career portfolio, the first step is to identify your goals and target audience. This is essential because it sets the tone for the entire portfolio creation process.

Importance of Setting Clear Career Goals

The first step in identifying your goals is to have a clear understanding of what you want to achieve professionally. Setting career goals allows you to focus on what you really want and how you can achieve it. Without clear career goals, you may find yourself wandering aimlessly without a clear direction or purpose.

When setting career goals, it is important to consider your long-term aspirations and map out a feasible path to achieving them. Make sure your career goals are ambitious yet attainable, and most importantly, align with your skills, interests, and values.

Identifying Your Target Audience for the Portfolio

Once you have identified your career goals, the next step is to determine your target audience for the portfolio. This will ultimately influence the tone, language, and content of your portfolio.

Your target audience may vary depending on your career aspirations. Are you a job seeker looking to land your dream job? Are you a freelancer aiming to attract clients and showcase your skills? Or are you a working professional seeking career advancement opportunities? Understanding your target audience will guide you to create a portfolio that speaks directly to their needs and interests.

Examples of Effective Goals and Target Audiences

To illustrate the importance of setting clear career goals and identifying your target audience, let’s look at some examples.

Career Goal: To become a freelance writer and build a successful writing business

Target Audience: Potential clients who are in need of high-quality content for their businesses

In this scenario, the portfolio should showcase the writer’s writing samples, testimonials from satisfied clients, and a clear strategy on how the writer can provide value to potential clients.

Career Goals: To become a marketing manager for a major corporation

Target Audience: Hiring managers and recruiters at major corporations

The portfolio should highlight the marketing manager’s past achievements, demonstrate their leadership skills, and highlight successful campaign strategies.

Identifying your career goals and target audience is a crucial first step in creating a career portfolio. By setting clear goals and understanding your audience, you can create a portfolio that effectively showcases your skills and accomplishments, and ultimately supports your professional aspirations.

Step 2: Choose Your Format and Style

Your career portfolio is a representation of your work and accomplishments, and as such, it should be presented in a format and style that reflects your personality and professionalism. When choosing the right format and style for your portfolio, there are a few considerations you need to keep in mind.

Considerations when choosing a portfolio format

Firstly, think about the purpose of your portfolio. What is it that you want to communicate to potential employers or clients? Are you showcasing your skills, experience, or both? Once you have a clear understanding of your portfolio’s purpose, you can then choose a format that will best highlight your achievements.

Another thing to consider is your audience. Who are you trying to reach with your portfolio? Understanding your audience can help you choose a format that will appeal to them. For example, if you are targeting a creative industry, you may want to consider a more visual and interactive format, such as a website or a video portfolio.

Different types of portfolio formats and their advantages and disadvantages

There are several types of portfolio formats to choose from, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages. Here are some of the most common formats:

Traditional print portfolio : This is a physical portfolio that is usually presented in a binder or folder. It is a great format if you want to showcase your print designs, such as brochures, posters, or flyers. However, it can be bulky and difficult to transport.

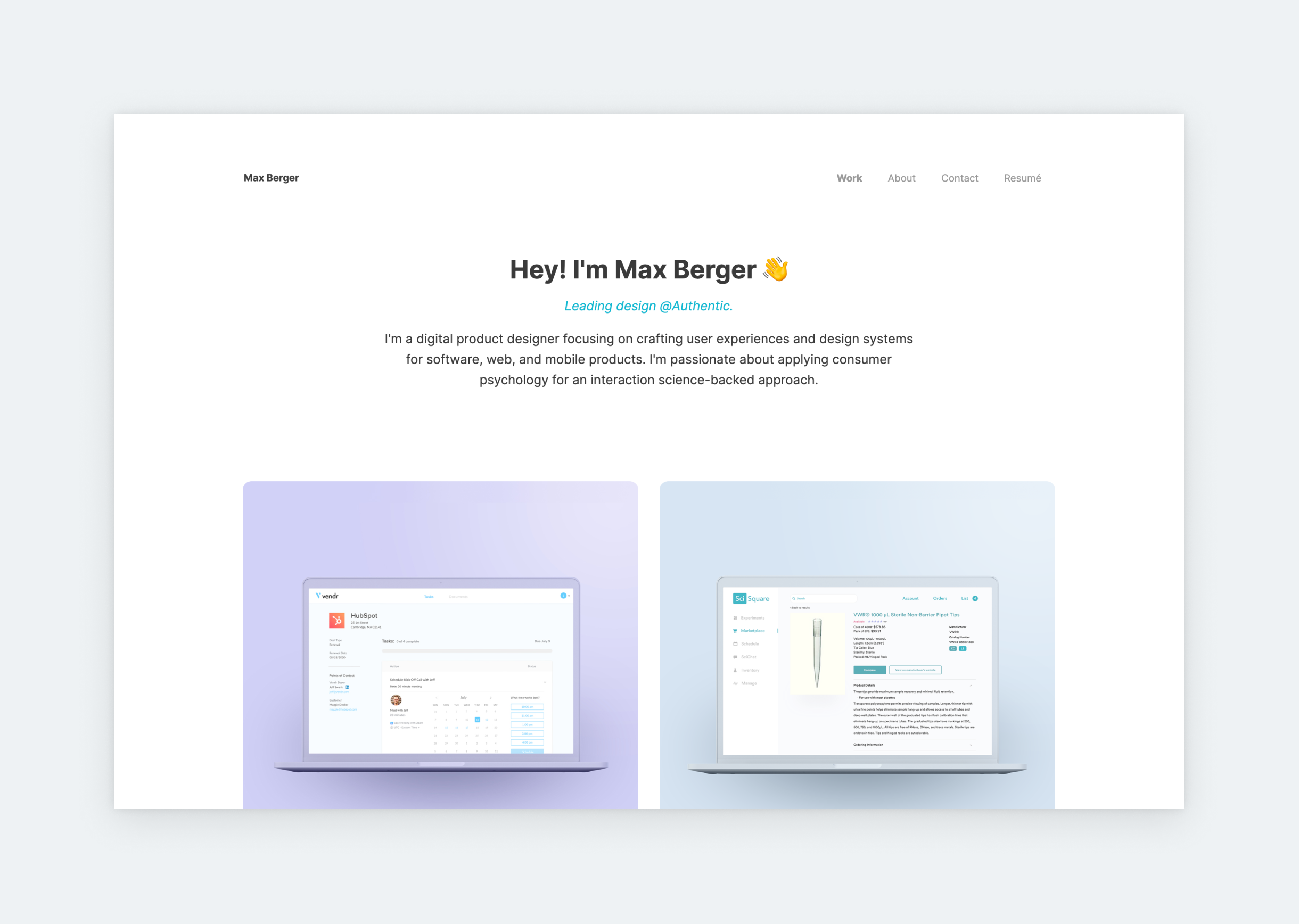

Digital portfolio : This is a portfolio that is stored digitally and can be accessed online. A digital portfolio allows you to showcase multimedia projects, such as videos, animations, and interactive designs. It is easy to update and share with potential employers or clients. However, it can be challenging to present your work in a cohesive and organized way.

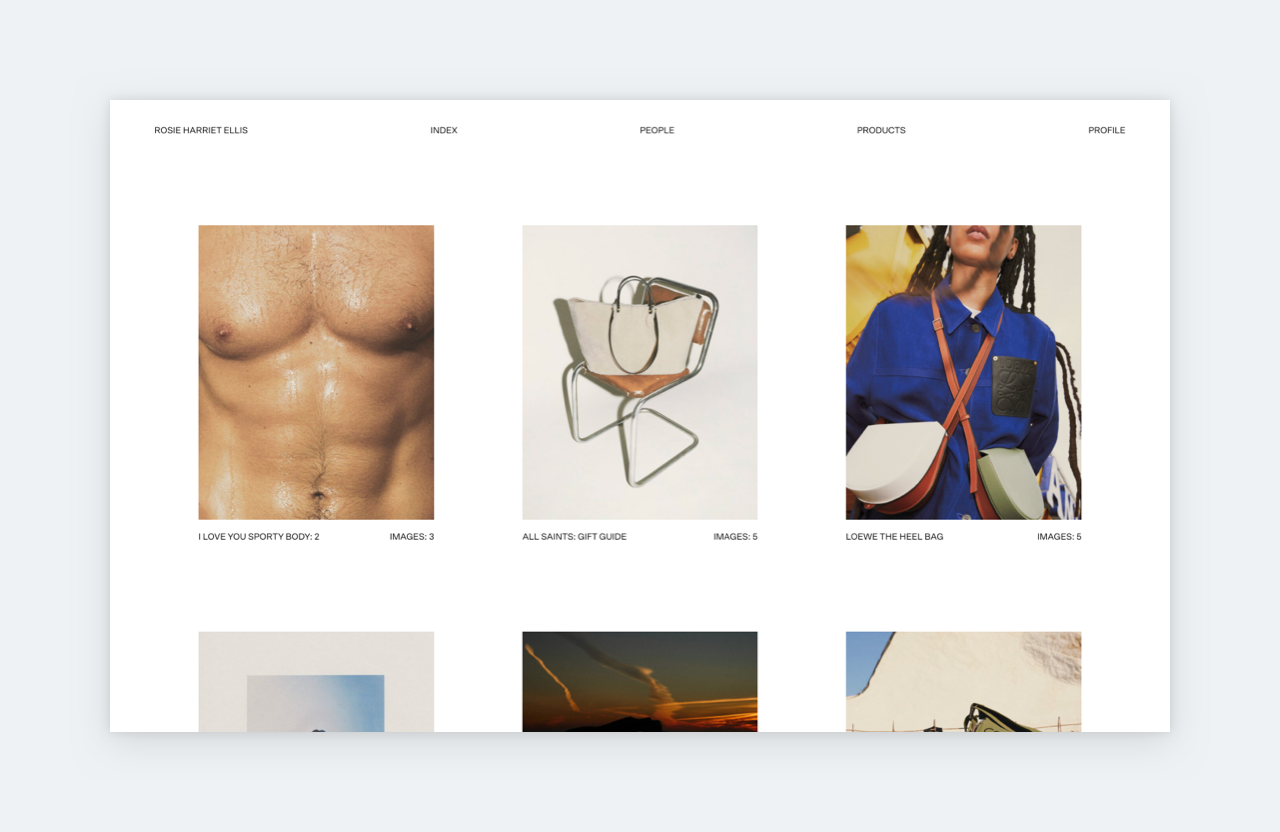

Website portfolio : This is a type of digital portfolio that is hosted on a website. It is a great format if you want to showcase your web design or development skills. A website portfolio allows you to showcase your work in a visually appealing way and provides a professional online presence. However, it requires technical skills to create and maintain.

Tips for choosing a style that aligns with your goals and target audience

Once you have chosen a portfolio format, you need to think about the style of your portfolio. Your portfolio’s style should reflect your personality, goals, and target audience. Here are some tips for choosing a style that aligns with your goals and target audience:

Choose a color scheme : A color scheme can help create a cohesive and attractive visual presentation. Pick colors that align with your branding or industry.

Use high-quality images : Your portfolio should contain high-quality images that showcase your work in the best possible way. Make sure your images are properly lit, in focus, and high resolution.

Step 3: Collect and Organize Your Best Work

One of the essential aspects of creating a career portfolio is showcasing your best work. Your portfolio must showcase the skills you have developed over time and highlight the quality of your work. In this section, we will discuss the importance of showcasing your most exceptional work and provide tips for choosing which work to include in your portfolio. Additionally, we will provide strategies for organizing your work effectively to make it more compelling for potential employers.

Importance of Showcasing Your Best Work

Showcasing your best work is essential because it demonstrates your abilities and expertise to potential employers. Your portfolio serves as a platform to showcase your achievements, the value you bring to the table and how you can help an organization. It provides tangible evidence of your skills and accomplishments, which helps to differentiate you from others vying for the same position.

Tips for Choosing Which Work to Include in Your Portfolio

The first step in creating a portfolio is to choose which work to include. Here are some tips to help you make informed decisions:

- Choose your most recent work

- Select work that highlights your skills and expertise

- Select projects worked on that are relevant to the position

- Ask for feedback from other professionals

- Include work that shows versatility, demonstrating the ability to work on diverse projects.

Strategies for Organizing Your Work Effectively

Organizing your work is critical in creating an effective career portfolio. Here are some strategies to follow:

- Categorize your work by project type or industry

- Provide context around each piece of work, describing your role and responsibilities

- Include a brief description of the project and the client or employer

- Use high-quality visuals, including images and infographics

- Highlight key results and accomplishments.

By following these strategies, you can make sure that your portfolio stands out and showcases your skills in the best possible way. Remember that the portfolio serves as an extension of you and should demonstrate your skills and experience. Therefore, take the time to collect and organize your best work to make a positive impression on potential employers.

Step 4: Create Your Portfolio Sections and Pages

After identifying your career goals and gathering relevant materials, it’s time to create the sections and pages of your portfolio. In this step, you’ll need to decide which sections to include and how to present them in an effective way. Here are some things to consider:

Overview of different portfolio sections to include

The sections you choose to include in your career portfolio will depend on your industry and career goals. Generally, portfolios should include sections such as:

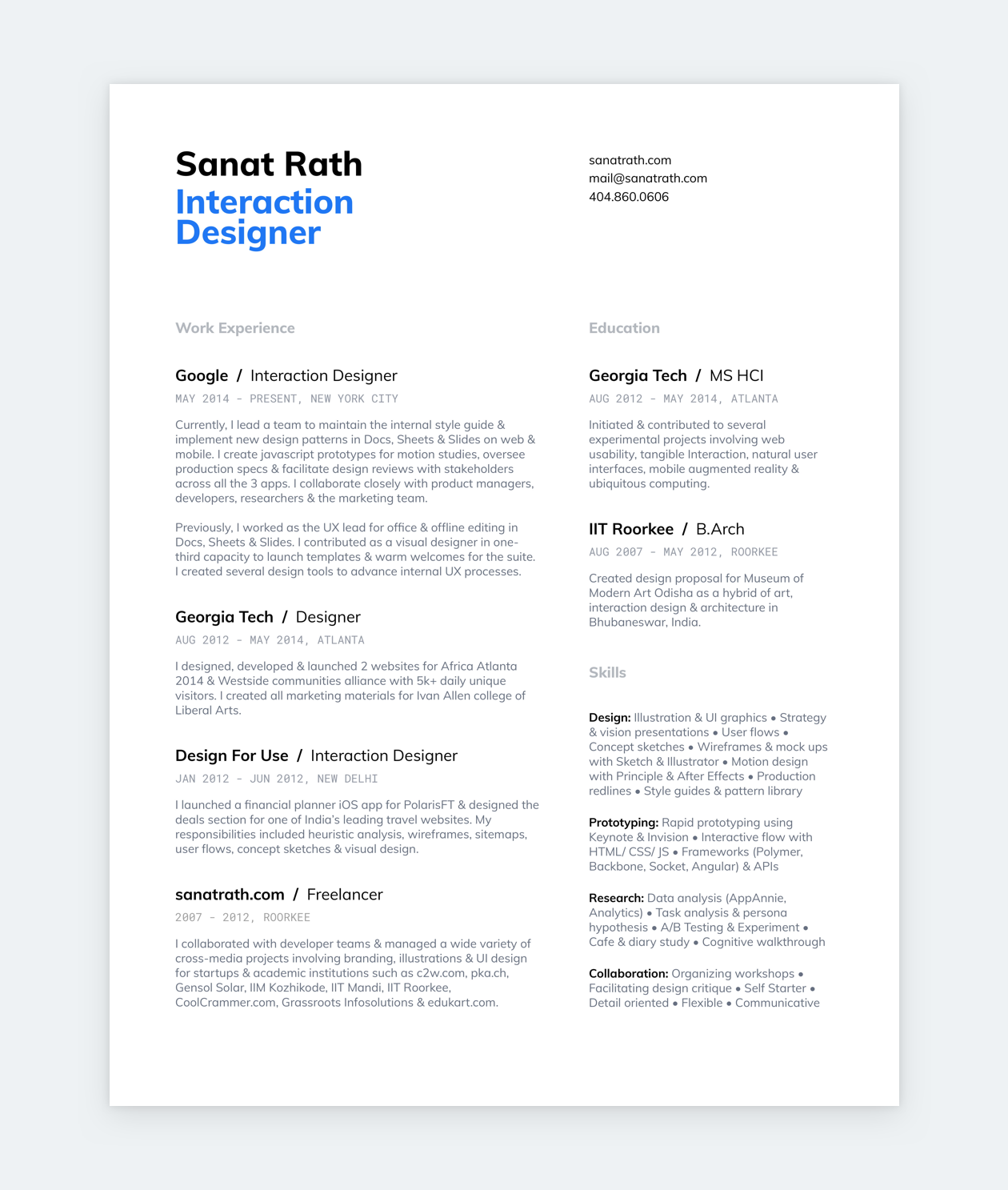

- Introduction: a brief statement about yourself and your career objectives

- Resume: a summary of your work experience and skills

- Samples of work: evidence of your skills and accomplishments, such as writing samples, design projects, or marketing campaigns

- Testimonials: recommendations and feedback from past clients or supervisors

- Certifications: proof of any professional qualifications or licenses you’ve obtained

- Contact information: how potential employers or clients can reach you

Strategies for designing effective portfolio pages

When designing your portfolio pages, keep these strategies in mind:

- Keep it simple: use a clean, easy-to-read design that doesn’t distract from your content

- Show your best work first: lead with your strongest samples and projects

- Organize by topic: group similar samples together to make it easy for viewers to find what they’re interested in

- Include context: provide a brief description of each sample to give viewers an idea of what it represents

- Use visuals: include images or other visuals to make your portfolio more engaging and memorable

Examples of effective portfolio layouts

There is no one right way to design a career portfolio, but here are a few examples of effective layouts:

- Chronological: organize your work samples in order of when they were completed, starting with the most recent

- Categorical: group your samples by topic or project type, such as writing, design, or social media campaigns

- Minimalist: use a simple and clean design with plenty of white space to draw attention to your content

- Bold and colorful: use bright colors, bold fonts, and eye-catching graphics to make your portfolio stand out

Whatever design you choose, make sure it reflects your personal brand and showcases your best work. With a well-designed career portfolio, you’ll be one step closer to landing your dream job or attracting new clients.

Step 5: Write Strong Headlines and Descriptions

When it comes to creating a career portfolio, writing strong headlines and descriptions is a crucial step. These elements are what draw the reader’s attention and entice them to learn more about your work. Here’s everything you need to know about crafting compelling headlines and descriptions:

Importance of Writing Compelling Headlines and Descriptions

Your career portfolio is your chance to showcase your skills and accomplishments to potential employers. However, if your headlines and descriptions are lackluster, you risk losing the reader’s attention before they even get to the meat of your portfolio. Compelling headlines and descriptions are your chance to make a great first impression and demonstrate your value.

Tips for Crafting Effective Headlines and Descriptions

- Keep it concise – you only have a few seconds to grab the reader’s attention, so make every word count.

- Use active language – action verbs are more engaging than passive voice.

- Be specific – give the reader a clear idea of what they can expect to see in your portfolio.

- Highlight your unique selling points – what sets you apart from other candidates?

Examples of Effective Headlines and Descriptions

Here are some examples of effective headlines and descriptions:

- “Award-winning graphic designer specializing in digital media”

- “Experienced project manager skilled in leading cross-functional teams”

- “Sales executive with a proven track record of driving revenue growth”

- “Innovative software engineer leveraging cutting-edge technology to create impactful solutions”

In each of these examples, the headline grabs the reader’s attention with a specific skill or accomplishment, while the description provides more detail about what the candidate can offer. By following these tips and examples, you can craft compelling headlines and descriptions that make your career portfolio stand out.

Step 6: Use Multimedia to Enhance Your Portfolio

A portfolio is a crucial tool for job seekers to showcase their skills and experience to potential employers. In today’s digital age, incorporating multimedia into your portfolio can greatly enhance its effectiveness by capturing the attention of recruiters and making your work stand out. Here are some benefits of using multimedia in your portfolio:

Benefits of Incorporating Multimedia into Your Portfolio

- Increased engagement: Multimedia content such as videos, infographics, and images can help capture the attention of recruiters and make your portfolio more engaging.

- Better representation of your work: Multimedia can help showcase your work in a way that text simply can’t. For example, a video can demonstrate your public speaking skills or a before-and-after image can showcase your design abilities.

- Ability to convey complex information: Multimedia can help simplify complex ideas and data, making it easier for recruiters to understand your work.

- Demonstration of technical skills: Incorporating multimedia into your portfolio can demonstrate your proficiency with various tools and technologies.

Types of Multimedia to Include and How to Use Them Effectively

When selecting multimedia for your portfolio, it is important to choose wisely. Here are some types of multimedia to consider:

- Videos: Include videos of yourself speaking or presenting, or showcasing your work in action.

- Infographics and charts: Use infographics and charts to demonstrate your ability to convey complex information in a clear and effective way.

- Images: Use images to showcase your design skills, or to demonstrate specific projects you have worked on.

- Interactive content: Consider including interactive demos or simulations to show off your technical skills.

It’s important to use multimedia effectively in your portfolio. Here are some tips for doing so:

- Be strategic: Choose multimedia that best demonstrates your skills and aligns with your target industry.

- Keep it relevant: Ensure that the multimedia content you include is relevant to the job or industry you are applying for.

- Maintain consistency: Make sure that the multimedia content is consistent with your brand and messaging.

- Provide context: Always provide context for the multimedia, including explanations of what the content represents and its relevance to the job or industry.

Tips for Ensuring Accessibility and Usability of Multimedia Content

It’s important to make sure that your multimedia content is accessible and usable to all potential recruiters. Here are some tips for doing so:

- Use alt text: Ensure that all multimedia content has alt text that describes the content for individuals with visual impairments.

- Provide transcripts: If you include videos or audio content, provide transcripts for individuals who may have difficulty hearing.

- Keep file sizes small: Keep file sizes small to ensure that your portfolio loads quickly, even on slower connections.

- Test for compatibility: Check that your multimedia content is compatible with all types of devices and browsers.

Step 7: Proofread and Edit Your Portfolio

Your career portfolio is a representation of your best work as a professional. It showcases your expertise, skills, and accomplishments. It is essentially a reflection of who you are as a professional, and it is essential that it is error-free and polished before presenting it to prospective employers.

Importance of Editing and Proofreading Your Portfolio

Editing and proofreading are essential steps in the portfolio creation process. They ensure that your portfolio is free of errors, typos, and formatting issues, while also making sure that the overall presentation is polished and professional.

A portfolio with errors and mistakes will give the impression that you lack attention to detail, which can be detrimental to your job search. Therefore, it is crucial to take the time to thoroughly edit and proofread your portfolio to ensure that it is flawless and ready to impress.

Strategies for Identifying and Correcting Errors

Proofreading is a critical phase to identify and correct any errors in your portfolio. It can be challenging to pinpoint your own mistakes, so it’s advisable to have another person review your portfolio.

You can also try reading your portfolio aloud to yourself or using proofreading tools like Grammarly, Hemingway Editor, or ProWritingAid. These tools will help you identify errors in grammar, tone, and syntax.

In addition, having a checklist of the critical components in your portfolio can help. This can include checking for consistency in formatting, proper use of heading and subheadings, and proper citation of sources.

Tips for Ensuring the Overall Quality of Your Portfolio

To ensure the overall quality of your portfolio, you need to do more than just proofread. There are certain things you can do to ensure that your portfolio stands out from the rest.

Start by choosing items that are relevant to the job you are applying to. It is best to tailor your portfolio for each job you apply for rather than have a generic one.

Also, ensure that your portfolio has a consistent look, feel, and tone. This means that you should use the same font, colour scheme, and design throughout the portfolio.

Lastly, your portfolio should comprise your best works. Showcase your achievements, projects, and accolades rather than every single work you’ve done. This not only helps with focus but also with creating an impressive and memorable portfolio.

Proofreading and editing your portfolio is essential in creating a polished and professional presentation of your best work. Use these strategies and tips to ensure that your portfolio is flawless, consistent, and stands out from the rest.

Step 8: Share and Promote Your Portfolio

As a professional, showcasing your accomplished works can go a long way in establishing your credibility and creating opportunities for career growth. In today’s digital age, doing so has never been easier – all thanks to the internet and its role in the democratization of information. However, creating a great portfolio is only half the battle – sharing and promoting it is equally important.

Importance of sharing and promoting your portfolio

Sharing and promoting your portfolio offers several benefits, the most obvious of which is the increased visibility it provides. A well-curated portfolio is like a window through which your target audience can see your skills and capabilities. It helps you to present your work in the best light and enables potential employers or clients to gauge your qualifications better. Further, it also allows you to cement your brand and position yourself as an expert in your chosen field. Sharing your portfolio gives you the chance to network and connect with like-minded professionals, foster relationships, and boost your chances of career advancement.

Strategies for sharing your portfolio with your target audience

The first step in sharing your portfolio is to identify your target audience. You want to share your content with people who will appreciate and benefit from it the most. Once you’ve determined who your target audience is, the next step is to choose the right platform. Sharing your portfolio on your website is a great start, but you can also leverage social media platforms like LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to put your content in front of a broader audience. Email marketing is another option that works well for freelancers who want to reach out to potential clients directly.

Another strategy for sharing your portfolio is by collaborating with professionals in your field. You can offer to contribute guest posts for industry blogs, participate in forums or online communities, and team up with influencers to expand your reach. Alternatively, you can seek to have your work featured in relevant publications, news outlets, or podcasts. The key is to identify platforms that align with your brand and target audience and use them to your advantage.

Tips for promoting your portfolio on social media and other channels

When promoting your portfolio on social media and other channels, it’s essential to ensure that your content is visually appealing and professionally done. Use high-quality images, videos, and graphics to showcase your work better. Make sure that your portfolio is easily accessible and includes a call-to-action that guides your audience to take the next step, whether it’s hiring you or contacting you for more information.

You can also leverage social media algorithms to promote your portfolio by using relevant hashtags, tagging influencers in your niche, and asking your followers to share your content. Other strategies include creating ads, giveaways, or contests that will help you to increase your reach and audience engagement. Collaborating with other professionals and industry thought leaders can also help you to expand your professional network and generate new business leads.

Step 9: Maintain and Update Your Portfolio Regularly

A career portfolio is an essential tool for showcasing your skills, accomplishments, and professional growth to potential employers or clients. However, creating a successful portfolio is not a one-time task. It requires regular maintenance and updates to reflect your professional progress and stay relevant in today’s job market.

Importance of Maintaining and Updating Your Portfolio

Maintaining and updating your portfolio is essential because it allows you to showcase your latest and best work. By updating your portfolio regularly, you can demonstrate your current skills, knowledge, and expertise. Additionally, an updated portfolio that reflects your professional growth can help you stand out from other candidates and position yourself as a serious candidate for the job or project.

A well-maintained portfolio can also help you track your achievements, set career goals, and identify areas for improvement. It can serve as a valuable tool for self-evaluation and continuous learning, helping you to stay motivated and focused on your career.

Strategies for Keeping Your Portfolio Up-to-date and Relevant

There are several strategies you can use to keep your portfolio up-to-date and relevant:

Regularly add new projects, work samples, and accomplishments to your portfolio. Make sure to highlight your latest and relevant experiences to showcase your current expertise.

Remove outdated or irrelevant content from your portfolio to keep it streamlined and focused on your current professional goals.

Keep your portfolio well-organized, easy to navigate, and visually appealing. Use a layout and design that best showcases your work samples and accomplishments.

Use language that emphasizes your skills and accomplishments, rather than just your job duties. Focus on outcomes and results rather than just tasks performed.

Incorporate feedback and testimonials from clients, employers, and colleagues to showcase your strengths and validate your achievements.

Use industry-specific keywords and trends in your portfolio that help you stand out in keyword searches and demonstrate your knowledge of industry trends.

Tips for Ensuring That Your Portfolio Reflects Your Career Progress

To ensure that your portfolio reflects your career progress, you should:

Regularly review your portfolio to ensure that it is up-to-date and aligned with your career goals.

Identify gaps in your portfolio that may be hindering your professional growth and proactively work to fill those gaps.

Use your portfolio to track your career milestones and set career goals for the future.

Continuously improve your portfolio by seeking feedback from mentors, colleagues, and industry experts.

Maintaining and updating your career portfolio is critical to showcasing your skills, expertise, and professional growth to potential employers or clients. By following the above strategies and tips, you can keep your portfolio up-to-date and relevant, demonstrate your current strengths and achievements, and stay competitive in today’s job market.

Related Articles

- Expert IT Consultant Resume Samples

- Discovering Career Paths: Full Guide for Every Personality

- Panel Interview: Top Questions and Answers

- Technical Project Manager Resume: Examples and Writing Tips

- Theater Resume Writing Tips and Samples

Rate this article

1 / 5. Reviews: 42

More from ResumeHead

- EXPLORE CAREERS

- APPOINTMENTS

- CAREER GUIDES

Showcase Your Experience with a Career Portfolio

A career portfolio can be used in the job search as a creative alternative to the standard resume and cover letter. Popularly used in areas such as advertising, public relations, and education, the career portfolio is useful with employers in other areas as well.

Rather than simply listing your skills, activities, interests, education and experience, a career portfolio allows you to enhance the presentation of your skills by including examples of work such as writing samples, class papers, class projects, awards, transcripts, photographs, certificates, etc.

Understanding the Career Portfolio

Why create a career portfolio.

- A career portfolio can help illustrate your professional accomplishments, talents, abilities, activities, and attitudes to prospective employers.

- The career portfolio also serves as a marketing tool, offering employers a preview of your performance as a potential employee.

How Can a Career Portfolio Help in the Job Search?

- Displays your capabilities

- Documents the quality and quantity of your professional accomplishments

- Demonstrates prior work or learning experience

- Sets you apart from other candidates for the job

- Illustrates proficiencies during or after an interview

- Helps you document your accomplishments and results

- Creates a personal database

How to Develop a Portfolio

Step 1: know yourself.

An effective portfolio needs to represent you and your strengths and should illustrate your skills, abilities and personal characteristics relevant to the job you want.

As you begin, ask yourself:

- What do I do well?

- How do I accomplish the tasks that I do well?

- In what tasks do I want to take part?

- Who do I want to review my portfolio?

- Why am I creating a portfolio?

- How can I demonstrate my skills, abilities, and knowledge to my reviewer?

Step 2: Filtering the Materials

Only include items that are necessary to your career pursuits. Consider tailoring your portfolio directly to a desired job. If the job asks for teamwork, public speaking, computer and communication skills, then only include items that prove you possess those skills.

Step 3: Production

The presentation of the portfolio is important. Include a table of contents, tabs, captions, and whatever else you would like in order for it to appear organized, reader-friendly, and versatile. Possible portfolio holders include binders, artist portfolio cases, and zipper cases. Clear sleeves to protect the materials can be purchased separately. Captions should be included in order to clearly state importance of the item for the reader.

You can make your portfolio stand out by adding a reflective essay in which you summarize the contents of the portfolio. This essay may include a stated purpose of the portfolio, an explanation behind the relation of educational and career goals to content of portfolio, and a reflection on what was learned from creating the portfolio, as well as what you plan to achieve in the future.

Step 4: Final Review

Check for typos, spelling, grammar, and formatting problems. Review the sections of your portfolio with your career counselor/educator, thinking about which parts you may elaborate on in an interview. If you plan to leave the portfolio with an employer, make sure that it is readable and self-explanatory.

Step 5: Sharing the Portfolio

If a portfolio is not requested prior to an interview, you can take it with you and offer it for viewing near the end of the meeting. It can also be displayed during the interview. However, leave the viewing option up to the employer so that he/she can either view it with you or after you leave.

Creating a scaled down version of a portfolio is another option. You can leave copies with the interviewer to keep. Make sure the copies are of good quality. Also, keep your portfolio items relevant to the position you are seeking.

Electronic portfolios on the internet are popular due to the convenient viewing and sharing of items.

Portfolio Tips

- Select and tailor the items you include to match each job for which you apply

- Choose only the best examples of your work

- Design pages to have impact and to be easy to read

- Select documentation that present concrete evidence of your skills

- Label each item for easy identification

- Make your portfolio unique and creative

- Make sure it is professional and typo-free

1.8 Portfolio: Tracing Writing Development

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Reflect on the development of composing processes.

- Reflect on how those composing processes affect your work.

The Portfolio: And So It Begins . . .

In simplest terms, a writing portfolio is a collection of your writing contained within a single binder or folder. This writing may have been done over a number of weeks, months, or even years. It may be organized chronologically, thematically, or according to quality. A private writing portfolio may contain writing that you wish to keep only for yourself. In this case, you decide what is in it and what it looks like. However, a writing portfolio assigned for a class will contain writing to be shared with an audience to demonstrate the growth of your writing and reasoning abilities. One kind of writing portfolio, accumulated during a college course, presents a record of your work over a semester, and your instructor may be use it to assign a grade. Another type of portfolio presents a condensed, edited story of your semester’s progress in a more narrative form.

The most common type of portfolio assigned in a writing course combines the cumulative work collected over the semester, plus a cover letter in which you explain the nature and value of these papers. Sometimes you will be asked to assign yourself a grade on the basis of your own assessment. The following suggestions may help you prepare a course portfolio:

- Make your portfolio speak for you. If your course portfolio is clean, complete, and carefully organized, that is how it will be judged. If it is unique, colorful, creative, and imaginative, that, too, is how it will be judged. Similarly, your folder will be judged more critically if it is messy, incomplete, and haphazardly put together. Before giving your portfolio to somebody else for evaluation, consider whether it reflects how you want to be presented.

- Include exactly what is asked for. If an instructor wants three finished papers and a dozen sample journal entries, that is the minimum your course portfolio should contain. Sometimes you can include more than what is asked for, but never include less.

- Add supplemental material judiciously. Course portfolios are among the most flexible means of presenting yourself. If you believe that supplemental writing will show you in a better light, include that too, but only after the required material. If you include extra material, attach a memo to explain why it is there and what you think it adds to your portfolio. Supplemental writing might include journals, letters, sketches, or diagrams that suggest other useful dimensions of your thinking.

- Include perfect final drafts. At least make them as close to perfect as you can. Show that your own standard for finished work is high. Check spelling, grammar, citation, formatting, and font sizes and types. You should go over your work carefully and be able to find the smallest errors. In addition, if you are asked for a hard copy of your portfolio, final drafts should be double-spaced and printed on only one side of high-quality paper, unless another format is requested. And, of course, your work should be carefully proofread and should follow the language and genre conventions appropriate to the task.

- Demonstrate growth. This is a tall order, but course portfolios, unlike most other assessment instruments, can show positive change. The primary value of portfolios in writing classes is that they allow you to demonstrate how a finished paper came into being. Consequently, instructors frequently ask for early drafts to be attached to final drafts of each paper, the most recent on top, so they can see how you followed revision suggestions, how much effort you invested, how many drafts you wrote, and how often you took risks and tried to improve. To build such a record of your work, make sure the date of every draft is clearly marked on each one, and keep it in a safe place (and backed up electronically).

- Demonstrate work in progress. Course portfolios allow writers to present partially finished work that suggests future directions and intentions. Both instructors and potential employers may find such preliminary drafts or outlines as valuable as some of your finished work. When you include a tentative draft, be sure to attach a memo or note explaining why you still believe it has merit and in which direction you plan to take your next revisions.

- Attach a table of contents. For portfolios containing more than three papers, attach a separate table of contents. For those containing only a few papers, embed your table of contents in the cover letter.

- Chronological order : Writing is arranged in order, beginning with the first week of class and ending with the last week, with all drafts, papers, journal entries, letters, and such fitting in place according to the date written. Only the cover letter is out of chronological order, appearing at the beginning and serving as an introduction to what follows. This method allows you to show the evolution of growth most clearly, with your latest writing (presumably the best) presented at the end.

- Reverse chronological order : The most recent writing is up front, and the earliest writing at the back. In this instance, the most recent written document—the cover letter—is in place at the beginning of the portfolio. This method features your latest (presumably the best) work up front and allows readers to trace the history of how it got there.

- Best-first order : You place your strongest writing up front and your weakest in back. Organizing a portfolio this way suggests that the work you consider strongest should count most heavily in evaluating the semester’s work.

With each completed chapter in this textbook, you will add to this portfolio. As you work through the chapters and complete the assignments, save each one on your computer or in the cloud, unless your instructor asks you to print your work and arrange it in a binder. Each assignment becomes an artifact that will form a piece of your portfolio. Depending on your preference or your instructor’s approach, you may write a little about each assignment as you add to the portfolio. As you compile your portfolio, take some time to read the assignments—drafts and finished products—carefully. Undoubtedly, you will see improvement in your writing over a short amount of time. Be sure to make note of this improvement because it will prove useful moving forward.

Reflective Task: The Freedom of Freewriting

As you begin your portfolio with the addition of your critical response, compose an accompanying freewrite , sometimes called a quick write . In this case, you will be responding to your own text—a powerful tool in your intellectual development. To begin, write quickly and without stopping about the process of composing your critical response and the finished product. See where your thoughts go, a process that often helps you clarify your own thoughts about the subject—your own text and its creation. When you freewrite, write to yourself in your own natural style, without worrying about sentence structure, grammar, spelling, or punctuation. The purpose is to help you tie together the ideas from your writing process, your assignment, and other thoughts and experiences in your mind. One future value of freewriting is that the process tends to generate questions at random, capture them, and leave the answering for a later task or assignment. Another bonus of freewriting is that you will build confidence with writing and become more disciplined when you have to write. In other words, the more you write, the more confidence you will have in your voice and your writing.

By now you may have realized that writing, whether on social media platforms or in the classroom, is a conversation. The conversation may take place with yourself (freewriting), with your instructor and classmates (assignment), or with the world (social media). You have learned how people like Selena Gomez and others use simple and effective strategies, such as vulnerability , understanding, analysis, and evaluation, to engage in such conversations. Now adopt these same processes—try them on for size, practice them, and learn to master them. As you move through the remainder of this course and text, compose with intention by keeping in mind the limits and freedoms of a particular defined rhetorical situation.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-8-portfolio-tracing-writing-development

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.2: The Research Portfolio/Narrative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6539

- Steven D. Krause

- Eastern Michigan University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

A “research portfolio” is a collection of writing you’ve done in the process of completing your research. Of course, the details about what is included in this portfolio will vary based on the class assignments. However, if you’ve been following through the exercises in Part Two of this textbook, chances are your portfolio will consist of some combination of these projects:

- The topic proposal exercise

- The critique exercise

- The antithesis exercise

- The categorization and evaluation exercise

- The annotated bibliography exercise

A research portfolio might also include your work on some of the various exercises in The Process of Research Writing and other assignments given to you from your teacher.

The goal of the exercises in Part II of this book is to help you work through the process of research writing, and to help you write an essay along the lines of what I describe in Chapter Ten, “The Research Essay.” However, as an alternative to using this previous work to write a research essay, you could write an essay about these exercises to tell the story of researching your topic.

This project, “The Research Portfolio/Narrative Essay” is similar to a more conventional research essay in that the writer uses cited evidence to support the point exemplified in a working thesis. However, it is different in that the writer focuses on the process of researching his topic, a narrative about how he developed and explored the working thesis.

The Assignment

Write a seven to ten page narrative essay about the process of working through the previously assigned exercises in the class. Be sure to explain to your audience-- your teacher, classmates, and other readers interested in your topic-- the steps you took to first develop and then work through your research project.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Why You Should Build a “Career Portfolio” (Not a “Career Path”)

- April Rinne

A “career portfolio” is a new way to think about, talk about, and craft your professional future.

Up until this point, we have lacked the language necessary to design our careers in ways that veer from the traditional script. But now there is hope. A new vocabulary is emerging. At the heart of it is a shift from pursuing a “career path” to creating your “career portfolio.”

- Whereas a career path tends to be a singular pursuit (climb the ladder in one direction and focus on what is straight ahead), a career portfolio is a never-ending source of discovery and fulfillment.

- It represents your vast and diverse professional journey, including the various twists and turns, whether made by choice or by circumstance.

- While your portfolio can include traditional paid jobs, don’t limit it to that. Think bigger. Your portfolio is created by you, rather than determined for you by someone else (like a bunch of hiring managers).

- It reflects your professional identity and potential. It includes your unique combination of skills, experiences, and talents that can be mixed, matched, and blended in different ways.

- In a world of uncertainty, talent that can expand their thinking beyond boxes, silos, or sectors will be in demand.

- Those who make an effort to build a career portfolio now will be more prepared to pitch themselves for (and even create) new opportunities, as they will be well-practiced at making creative connections between their various skills and the skills required of the jobs they most wish to pursue.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Every four years, something inside me shifts. I get restless and want to learn something new or apply my skills in a new way. It’s as though I shed a professional skin and start over, fresh.

- April Rinne is a World Economic Forum Young Global Leader and ranked one of the “50 Leading Female Futurists” in the world by Forbes. She is a change navigator who helps individuals and organizations rethink and reshape their relationships with change, uncertainty, and a world in flux. She’s a trusted advisor, speaker, investor, adventurer (100+ countries), insatiable handstander , and author of Flux: 8 Superpowers for Thriving in Constant Change .

Partner Center

- Search entire site

- Search for a course

- Browse study areas

Analytics and Data Science

- Data Science and Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Courses

- Business Research Programs

- Undergraduate Business Programs

- Entrepreneurship

- MBA Programs

- Postgraduate Business Programs

Communication

- Animation Production

- Business Consulting and Technology Implementation

- Digital and Social Media

- Media Arts and Production

- Media Business

- Media Practice and Industry

- Music and Sound Design

- Social and Political Sciences

- Strategic Communication

- Writing and Publishing

- Postgraduate Communication Research Degrees

Design, Architecture and Building

- Architecture

- Built Environment

- DAB Research

- Public Policy and Governance

- Secondary Education

- Education (Learning and Leadership)

- Learning Design

- Postgraduate Education Research Degrees

- Primary Education

Engineering

- Civil and Environmental

- Computer Systems and Software

- Engineering Management

- Mechanical and Mechatronic

- Systems and Operations

- Telecommunications

- Postgraduate Engineering courses

- Undergraduate Engineering courses

- Sport and Exercise

- Palliative Care

- Public Health

- Nursing (Undergraduate)

- Nursing (Postgraduate)

- Health (Postgraduate)

- Research and Honours

- Health Services Management

- Child and Family Health

- Women's and Children's Health

Health (GEM)

- Coursework Degrees

- Clinical Psychology

- Genetic Counselling

- Good Manufacturing Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Speech Pathology

- Research Degrees

Information Technology

- Business Analysis and Information Systems

- Computer Science, Data Analytics/Mining

- Games, Graphics and Multimedia

- IT Management and Leadership

- Networking and Security

- Software Development and Programming

- Systems Design and Analysis

- Web and Cloud Computing

- Postgraduate IT courses

- Postgraduate IT online courses

- Undergraduate Information Technology courses

- International Studies

- Criminology

- International Relations

- Postgraduate International Studies Research Degrees

- Sustainability and Environment

- Practical Legal Training

- Commercial and Business Law

- Juris Doctor

- Legal Studies

- Master of Laws

- Intellectual Property

- Migration Law and Practice

- Overseas Qualified Lawyers

- Postgraduate Law Programs

- Postgraduate Law Research

- Undergraduate Law Programs

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Postgraduate Science Programs

- Science Research Programs

- Undergraduate Science Programs

Transdisciplinary Innovation

- Creative Intelligence and Innovation

- Diploma in Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Degree

- Transdisciplinary Learning

Developing an academic portfolio

A portfolio supports you in your role as an academic by creating a record of your reflection, development and achievements over time. You may like to use aspects of your portfolio to provide evidence for formal probation review, progression or promotion processes.

What is an academic portfolio and what should it include?

An Academic Portfolio is an organised record of your academic experiences, achievements and professional development. It consists of a collection of documents which illustrate the variety and quality of work that you do, along with your reflections on these documents and on your development over time.

There are three major areas of academic work that you should include in your portfolio:

- teaching and educational development

- scholarship and the advancement of knowledge and its applications

- contributions to the university and the community.

You should include some evidence of your participation and reflection in each of these areas, although at any point in your academic career your work is likely to have a greater focus on some areas than on others. If your appointment is at level B (lecturer) or higher, you would consider a fourth aspect, that of leadership within the university. As well as including these areas of academic work, try to include an overview section where you reflect on and review your activities in relation to your overall goals and career plans.

These guidelines suggest ways that you can develop your Portfolio to encompass the major areas of academic practice. Each academic's experience and context will be different, so there is no expectation that all Portfolios will be similar. Rather they should contain evidence of individual academic achievements and experiences, with reflections on these experiences.

Getting Started

Developing a portfolio is an ongoing process. As your portfolio develops over time, you will include documents which provide evidence of a wide range of activities and achievements, along with your r eflections on these documents. Getting started means beginning to create a framework and sections for your portfolio which you find useful and can continue to use, then adding one or two items at a time as you engage with different aspects of your work.

Try to add to your documents and reflections on a regular basis, both to assist your professional development and so that your portfolio will be up to date for occasions when you discuss your academic progress with your supervisor or are planning an application for promotion.

Example 1: Alison's portfolio

| Alison is a new Associate Lecturer whose immediate goals include learning to teach effectively in tutorials and lectures, and commencing a PhD. This is what her portfolio contains by the end of her first session: |

Example 2: Dimitri's portfolio

| Dimitri is a new Lecturer who has come to UTS after two years as an academic in another university. His goals are to build his research and publication profile and further develop his teaching with the aim of applying for promotion within three years. Some of the supporting evidence he collects in his portfolio in the first session includes:

|

The private and public faces of the portfolio

It is quite reasonable to keep some aspects of the academic portfolio private. There are likely to be some reflections or documents which are important for your development but which you do not wish to show to others.

A well developed academic portfolio would be too much to present for either your discussions with your academic supervisor or for a promotion committee. It would be more appropriate to include an extract with descriptions of and reflections on your major achievements and references to other documentation.

Suggested sections for the portfolio

The following guidelines provide advice on developing different sections of your portfolio. For each of the three major areas of academic work (teaching and educational development, scholarship and the advancement of knowledge and its applications, contributions to the university and the community) we have included some advice on:

- describing what that aspect of your work means to you, including possible questions for reflection

- sources of evidence you could include in documenting that aspect of your work

- questions for making a self evaluation of your achievements and development.

The ideas described are suggestions. Your portfolio will be individual and is likely to have more emphasis in some areas than in others. Remember that an effective portfolio will include both documentary evidence and reflection, eg. a subject outline that you have developed with a reflection on the effectiveness of the outline in terms of student learning and the changes you may make as a result.

Teaching and educational development

Many academics, especially those at Associate Lecturer and Lecturer level, spend a great deal of time preparing for teaching, teaching and assessing their students' learning. We hope that developing this section of the portfolio will enable you to improve your practice as a teacher through reflection and self evaluation.

Imagine that you are trying to give someone else a picture of your teaching - what you do and why you do it that way. Your portfolio should create a picture that illustrates some of the complexity and variety of what you do and why. At minimum, your portfolio would include a statement outlining your own teaching philosophy, and an overview of your teaching experience: the range of subjects and classes you have taught, postgraduate supervision etc. It would then include some items documenting different aspects of your teaching.

What teaching means to you

Describe your own understanding of teaching and the way in which you see the relationship between teaching and learning. In this way you will have a record of your thoughts on teaching and learning as you commence your career as an academic at UTS. You will be able to return to your initial ideas from time to time and consider the development and changes that have occurred as you have developed your expertise. This section could be private to begin with, but later you might develop a description of your teaching philosophy to include in the portfolio extract that you would show to others.

Possible questions for reflection about teaching and educational devlopment

- What are your overall teaching goals and the goals that you have for your students' learning?

- How does your teaching encourage student learning? Consider your subject objectives, teaching approaches, learning tasks for students, assessment and feedback.

- How do you know whether your teaching has encouraged student learning?

- How confident and comfortable do you feel about your teaching and what helps you to develop confidence?

- How have your experiences helped you to develop or change your understanding of teaching and learning?

Supporting evidence

Examples that could be used to support or give evidence for your teaching over time may include:

- A series of subject outlines for a subject you have taught for several years, with a reflection on why you made the changes you did

- A reading list that you give to students, with reflections on how students responded to the references chosen

- Case studies developed from your class room experiences. This could be in the form of a description of the experience and then a reflection about the experience followed by recommendations for continued development or change, eg. an outline of a lecture or tutorial, with your reflection on why the session was conducted that way, how it went and any proposed changes

- A description of and reflection on an innovative teaching approach, why the approach was chosen, whether it achieved its intentions and any suggested changes for next time

- An interview with a student about her/his approach to learning in your lectures, with your reflection on whether this matched your expectations

- Examples of assessment tasks, with your reflection on the appropriateness of those tasks

- Examples of student work, with your feedback attached, and a reflection on your response to the student's work

- A peer evaluation of a teaching session, with a reflection on your response

- Student evaluations of the subject, with a reflection on how consistent they are with your self-evaluation and what changes you have made as a result

- Description of and reflection on a supervision session with a postgraduate student, highlighting your intentions and contribution, and discussing this in relation to your views on supervision

- Excerpts from a good student project, with a reflection on how you helped the student to develop ideas

- A flyer describing a workshop on teaching you attended, with a reflection on the impact this had on your teaching.

Questions for self evaluation

- To what extent have your personal goals for teaching been met?

- How do you know whether you have been teaching well, and what evidence do you have of good teaching?

- What are your main achievements in teaching and what evidence do you have for these?

- What is your progress towards achieving the teaching goals that you have negotiated with your supervisor?

- What support have you received to develop your teaching and what would you need to develop further as a teacher?

Scholarship and the advancement of knowledge and its applications

Scholarship can be defined in several ways according to your academic context. In UTS documentation such as promotion guidelines, 'scholarship' is described as the distillation and integration of knowledge. Scholarship of this type would be expected in most areas of academic work, including teaching, research, consultancy and many types of service to the community. In reflecting on scholarship, you are encouraged to think about how you keep up to date in your field and continue to distil and integrate knowledge, both in your research and in your teaching, both in terms of content and process.

'Advancement of knowledge' includes activities which might commonly be referred to as research. The Academic Portfolio could be used to enable you to reflect upon the nature of research in your discipline, the research process and how you see yourself as a researcher. It could enable you to reflect upon your own development as a scholar and/or researcher and provide evidence of research development and contribution.

What scholarship and the advancement of knowledge means to you

At the beginning of this section it might be useful to describe how you see scholarship in your discipline. Describe what it means to distil and integrate knowledge in your discipline area, what sources of knowledge are important and how you engage in scholarship in the different parts of your work, including your teaching.

Now describe what 'advancement of knowledge' or research means in your discipline, and how this relates to your own research interests and your development as a researcher. In some disciplines (eg the physical sciences) describing what research means might be fairly straightforward, in others (eg design or production studies) it might be more difficult to define and include aspects such as original creative contributions. It might be helpful to talk to one or two senior colleagues about the nature of research in your field and then reflect on their ideas.

Questions for reflection about scholarship

- How do you keep up to date in your discipline area? What sources do you use to do this?

- In what ways is your work scholarly?

- How would you describe scholarship in teaching, and how do you apply it to your own teaching?

- In what ways do you enable your students to engage with current ideas in your discipline area? This could include thinking about how you relate your research to your teaching.<

Questions for reflection about the advancement of knowledge

- What are your personal research interests?

- What are your research goals or intentions?

- How does your research interests fit into the interests of your academic department?

- In what ways can your research make a contribution to your discipline?

- How do you find out about sources of funding and resources which could support your research?

- How have your experiences helped you to develop or change your understanding of research and scholarship in your discipline?

- A reading log showing the journals and other publications which you read on a regular basis

- Notes and reflections on research seminars you have attended in your School/Department or discussions with your colleagues

- Notes you have kept in the process of working with a mentor, with your reflection on what you are learning from the process

- Copies of contributions of a scholarly kind made to computer based research discussion groups or listserves

- An up to date publications list, with separate headings for refereed journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, contributions to other materials etc, along with reflections on what you see as your most important publications

- Copies of referees' reports on your writings and letters of acceptance from journals

- Invitations to referee papers for journals in your field

- Copies of publications which cite your research

- Copies of grant applications

- Invitations to present your research at seminars.

- To what extent have your personal goals for scholarship and the advancement of knowledge been met?

- What evidence do you have that you are contributing to the advancement of knowledge in your field or developing the potential to do so?

- What are your main achievements in research and scholarship and what evidence do you have for these?

- What is your progress towards achieving the research goals that you have negotiated with your supervisor?

- What support have you received to develop your research and scholarship and what would you need to develop further as a researcher?

Contributions to the university and the community

The university expects all academics to make ongoing contributions to the university and to the role of the university in the community, at a level appropriate for their level of appointment. Activities which constitute a minimum contribution to the university will generally be part of your normal duties. This would involve reliable performance of your administrative responsibilities, contributions to policy development at a level appropriate for your level of appointment and for some academics the initiation or maintenance of links between the University and external groups (see promotions policies).

The nature of other contributions to the university and the community can vary markedly between individual academics according to their interests, abilities, discipline area, opportunities and level of appointment. Contributions to the university from level A or B academics could include active participation in Faculty or university committees or working parties, organisation or management of particular functions or events in your Faculty or taking on a role such as Academic Liaison Officer. Contributions to the community could include: involvement in professional societies or community groups relevant to your discipline area; organisation of public events, exhibitions, forums or meetings; membership of policy advisory or expert groups.

Some opportunities to contribute occur fortuitously but others may need to be planned for, initiated or deliberately sought. This is an area where your supervisor should be able to assist you, for example, by suggesting activities appropriate to your expertise and interests, suggesting your name for membership of committees or by referring you to colleagues or contacts within the university or elsewhere.

Include a statement about the nature of your contributions to the university and the community.

It could be helpful to describe the contributions which are expected of you in your academic unit, and outline your understanding of the kinds of contributions which are most commonly made in your discipline area. Then describe the expertise and interests that you have which might be most relevant to making further scholarly contributions to the university and community.

Questions for reflection about your contributions

- What administrative responsibilities are expected in your position?

- What contributions to the university are expected of academics at your level in your academic unit?

- How are you developing your knowledge and understanding of the university so that you can identify opportunities for making useful contributions?

- What opportunities might there be for you to make an active scholarly contribution outside the university?

- Up-to-date lists of memberships of committees and professional societies

- A description of a specific contribution you have made to the work of a committee and reflections on the effects or impact of your contribution

- A description of your participation in working groups with a reflection on your main contributions

- Copies of publicity or other materials from events that you have organised with a reflection on your contribution

- Letters of thanks for your work from professional bodies or community groups

- Invitations to address public meetings or make contributions.

- What have been your most important contributions to the university and the community, and what evidence do you have of these contributions?

- How far has your involvement reflected your intentions and your academic unit's expectations?

- How has your contribution enhanced the quality of the university or community's work?

- What is your progress towards achieving the goals that you have negotiated with your supervisor?

- What support have you received to develop your contributions in this area and what would you need to develop your contributions further?

Academic Leadership

Academics at levels A and B are not usually required to perform leadership roles, however you may have opportunities to demonstrate leadership potential, for example by taking a leading role in a teaching development or research initiative. Promotion to Senior Lecturer requires that the applicant provide indications of a capacity for academic leadership within the university and promotion to Associate Professor requires that the applicant demonstrate leadership capacity. It would be wise to give some thought to the development of your leadership skills and qualities, and to document activities where you believe you have demonstrated a capacity for leadership.

Personal Academic Plans and Goals

It may be helpful to consider how the activities above fit with your personal goals and plans, or what kind of pattern they show when looked at together.

This final section of the portfolio could be private, but you might want to share aspects of it in discussion with your supervisor or mentor. Although the promotion, tenure and probation planning processes include consideration of broad goals, there are some other issues that could be very important to assist you to develop an on going plan for the future.

Questions for reflection

- What gives me the most satisfaction as an academic?

- What causes frustration and is there anything I can do about it?

- Where would I really like to be in my career in a year's time, five year's time, ten year's time?

- Do I have any particular goals that I would like to achieve?

- How consistent is what I am doing now in my work with my answers to the above questions?

- Are my goals and career plans consistent with the goals negotiated with my supervisor, or should I consider some re-negotiation?

- Who could help my career at present?

UTS acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation, the Bidiagal people and the Gamaygal people, upon whose ancestral lands our university stands. We would also like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.

- Portfolio Tips

- Career Tips

- Portfolio Examples

- Get UXfolio!

How to Make an Impressive Career Portfolio? Your One-step Guide with Examples

You have to stand out as a candidate – but it’s easier said than done. In a landscape as fiercely competitive as today’s, doing the expected might not be enough anymore. So, after polishing your resumé and cover letter, you might want to make a career portfolio to highlight your achievements, expertise, range, and growth. Now the only question is how. And that’s where this guide enters the picture. You’ll learn:

What is a career portfolio?

- The difference between a career portfolio and a resumé?

- What to include in your career portfolio?

- What not to include in your career portfolio?

- The must-have parts of a career portfolio

How to build a career portfolio?

A career portfolio is a collection of your professional achievements presented in the form of categorized samples, galleries, or case studies, and bound together in a document or a website.

Professional achievements cover previous work experience, education, pro-bono projects, and even passion projects. The form of presentation depends on the nature of your work:

- Highly visual fields, such as photography or makeup artistry, tend to use galleries.

- Other fields mix visuals with text in the form of case studies.

A career portfolio can be a document (PDF), or a website. Nowadays, portfolio websites are more popular, because of their availability and ease of use. What’s more, with modern portfolio and website builders , anybody can create one on their own.

What to include in a career portfolio?

You can include anything in a career portfolio that’s relevant to your profession . However, it’s best to approach your career portfolio with a strategy in mind. There’s a common saying in design circles: “you’ll be judged based on your worst work.”

If you present something mediocre (or worse) in your portfolio, it can actually decrease your chances of succeeding. Therefore, you should present only your best work in your portfolio. There’s no quota to hit. One brilliant presentation is better than 3 mediocre ones. But how can you identify your best work?

Your best work shows your experience, expertise, as well as willingness to learn and grow. It’s the “willingness to learn and grow” part that many professionals forget about. Most companies are looking for professionals who can evolve in their profession. Your portfolio can prove that you are capable of this. Here’s how you can prove this in your portfolio:

Unlike your resumé, your portfolio is an empty canvas with limitless space. This allows you to describe your thinking process through real-life experiences or – if you’re from a visual field – to show a varied range of samples.

Showing your process and range

If you’re writing a case study , you can present how you’ve changed direction throughout a project for better outcomes, you can list what you’ve learned through a certain project, or you can go into details about what you’ve been doing differently since a certain project.

If your portfolio is visual , show diversity to prove your range. Maybe some of your work is not necessarily your style, but that doesn’t mean it’s not quality work. It’ll show that you’re willing to get out of your comfort zone when it’s required and still do an amazing job.

As you can see, sometimes your best work is not what first comes to mind. Make sure to spend some time thinking about the projects that made you a better professional. While at it, you can also think of what sells. If you have something that’s tried-and-true in your field run with it. Attempting to be different for the sake of being different can backfire, making you look standoffish or out of the loop.

So let’s go through these points again:

- Pick your best and most relevant work only.

- Your best work showcases your experience, expertise, range and willingness to grow.

- Don’t try to be forcefully different for no reason.

What not to include in your portfolio?

Now you know what to include in your career portfolio, but it can be helpful to go through a few things that you should definitely leave out:

Outdated work has no place in your portfolio. You’re better off without projects that were made a decade ago, unless they’re still in use or won you an award. Instead, add work that’s recent, using the newest techniques mixed with the gold-standards.

Irrelevant work will clutter up your portfolio. If you’re an editorial photographer, including your hobby graphic design projects will only cause confusion and make your portfolio look amateurish. Keep things focused.

It doesn’t matter how you present it, work that’s below your standards will reflect bad on you. There’s no quota. Don’t add things to your portfolio that you’re not proud of or sure of. Here’s a good pointer: if you have to think too much about it, you’re better off without it.

Let’s say, with all this considered you’re left with only a very few projects. In that case, you can add passion projects or do some pro-bono work for material. Just because you don’t get paid for something it’s not less valid than other work.

How to present your projects in a career portfolio?

Now that you’ve assembled your projects it’s time to add them to your portfolio. We’ve already mentioned that there are two common ways to present your work: through categorized examples or through case studies. Let’s see how you can do

Categorized examples or galleries are best for visual portfolios, such as photography, makeup, interior design, and graphic design . Your only job is to find the common thread that ties separate pieces of your work together – a theme, or a project, a color story, and whatnot – group them together and add them to your portfolio.

Case studies allow you to describe singular projects. They are best for professions where pictures can’t do all the talking, such as marketing, UX design, or teaching. If you go with this format, you should dedicate a separate section or page for each case study.

Projects to the center stage

Regardless of the format you’re presenting your projects, you must allow them to take center stage. While your personality matters a lot for company culture, it’s your work that’s most important when it comes to the hiring process. So make sure that your projects are easily accessible. Preferably, you should link to them from your home page, using stunning and descriptive thumbnails. Easy access to projects is key.

Before getting to work, you have to decide on the platform of your portfolio. You have two options:

- Portfolio as a document.

- Portfolio as a website.