An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Levels, antecedents, and consequences of critical thinking among clinical nurses: a quantitative literature review

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding email: [email protected]

Received 2020 Aug 12; Accepted 2020 Sep 7; Collection date 2020.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The purpose of this study was to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of critical thinking within the clinical nursing context. In this review, we addressed the following specific research questions: what are the levels of critical thinking among clinical nurses?; what are the antecedents of critical thinking?; and what are the consequences of critical thinking? A narrative literature review was applied in this study. Thirteen articles published from July 2013 to December 2019 were appraised since the most recent scoping review on critical thinking among nurses was conducted from January 1999 to June 2013. The levels of critical thinking among clinical nurses were moderate or high. Regarding the antecedents of critical thinking, the influence of sociodemographic variables on critical thinking was inconsistent, with the exception that levels of critical thinking differed according to years of work experience. Finally, little research has been conducted on the consequences of critical thinking and related factors. The above findings highlight the levels, antecedents, and consequences of critical thinking among clinical nurses in various settings. Considering the significant association between years of work experience and critical thinking capability, it may be effective for organizations to deliver tailored education programs on critical thinking for nurses according to their years of work experience.

Keywords: Nurses, Critical thinking, Literature review

Introduction

As the healthcare environment has become more complicated and detail-oriented and health professions have become more advanced, more nursing professionalism has been expected in recent years. To be more competent, nurses should be critical thinkers who can effectively cope with advancing technologies, human resource limitations, and the high level of acuity required in diverse healthcare settings. Critical thinking (CT) is considered to be a crucial element for clinical decision-making by nurses, and improved empowerment to engage in CT is considered to be a core program outcome in nursing education. However, recent studies have reported difficulties in applying CT to nursing practice [ 1 , 2 ], moderately low levels of CT among nurses [ 3 ], and differences in the understanding of the meaning of CT among nursing educators and scholars [ 4 ].

Since CT was emphasized as an essential component of the nursing process in the 1970s, numerous nursing scholars have attempted to define the concept of CT for nursing [ 5 ]. During the introductory period of CT, intellectual or cognitive skills were mostly emphasized. A decade later, affective disposition was also noted as an important component of CT in the context of a caring relationship [ 6 ]. Emotional involvement enables nurses to genuinely feel the suffering and pain that patients experience [ 7 ]. In 2000, Scheffer and Rubenfeld [ 8 ] identified essential components of CT, including 10 affective habits of the mind and 7 cognitive skills, by using the Delphi method to arrive at a consensus on an acceptable definition of CT. In recent years, nurses have been increasingly expected to develop both CT affective dispositions and CT cognitive skills [ 9 ]. Affective dispositions such as being open-minded, inquisitive, and seeking truth can stimulate an individual towards using CT through a reasoning process [ 10 ]. Meanwhile, cognitive skills may help nurses analyze their inferences, explain their interpretations, and evaluate their analyses [ 11 ]. Knowledge is also necessary to strengthen and support the cognitive process of CT [ 3 , 10 ].

To our knowledge, the most recent scoping review on the concept of CT in the nursing field was reported in 2015 [ 5 ]; according to this comprehensive review [ 5 ], there was growing interest in the study of the concepts and dimensions of CT experienced by nurses and nursing students, as well as in the development of training strategies for both students and professionals. However, a direction for further research into CT among clinical nurses was to specifically focus on its features or tendencies and changes in the CT phenomenon as time goes by, because confusing perspectives and poor knowledge of CT among nurse-educators can threaten the nursing profession [ 12 ]. Furthermore, an extensive review of quantitative research findings on CT among nurses is lacking, since only a scoping review was published in 2015 [ 5 ]. Thus, it is necessary to better understand how clinical nurses exercise CT to cultivate their clinical decision-making skills by reflecting on the contemporary nursing context.

The purpose of this study was to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of CT in the clinical nursing context. In this review, we specifically addressed the following research questions: what are the levels of CT among clinical nurses?; what are the antecedents of CT?; and, what are the consequences of CT?

Ethics statement

This study did not have human subjects; therefore, neither institutional review board approval nor informed consent was required.

Study design

A narrative literature review was used. We followed the methodologies described by the Center for Reviews and Dissemination for undertaking reviews [ 13 ] and by Petticrew and Roberts [ 14 ], who addressed the practical guide as an alternative to systematic reviews in the social sciences, since our major goal was to synthesize the individual studies narratively and not to evaluate the efficacy and safety of interventions or programs.

Materials and/or subjects

Information sources.

In this study, CT in clinical nursing was analyzed using a narrative review design to provide an overview of CT among nurses. We conducted an extensive search in the MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Ovid databases for articles published from July 2013 to December 2019 on CT among nurses, since Zuriguel Pérez et al. [ 5 ] comprehensively conducted a scoping review of articles on this topic that included research published from January 1999 to June 2013.

The following keywords were used: “critical thinking,” “professional judgment,” “clinical judgment,” and “clinical competence.” We also used the snowball method to identify additional studies. Titles and abstracts were screened, and studies were included if they presented empirical research on CT among clinical nurses, published in English from July 2013 to December 2019. Publications were excluded if they were reviews, case studies, or unpublished dissertations, or if CT was only studied among nursing students.

Search outcomes

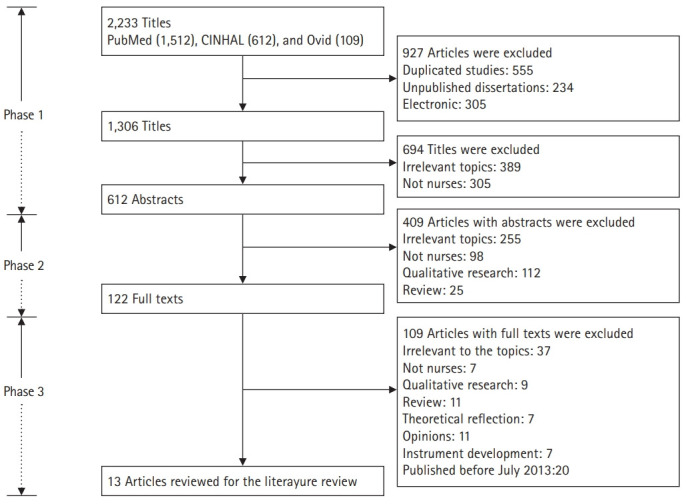

Both researchers (Y.L. and Y.O.) carried out the literature search to ensure that all relevant articles would be identified. The search produced a total of 2,233 articles. Candidate articles were screened by title. Titles that both researchers agreed were irrelevant to the aim of this review, as well as duplicates, were excluded. All other articles (612) were assessed as potentially relevant to the topic, and those for which consensus was reached between the authors were forwarded to the next phase ( Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram of the process of identifying and including articles for this review.

All abstracts from the articles selected during phase 1 were evaluated by reading them and checking whether they met the inclusion criteria. All studies that met the criteria proceeded to the next phase of the search process. If no consensus was reached for a particular article, the article was also forwarded to the next phase. All other studies (490) were excluded ( Fig. 1 ).

In the final phase of the search process, a total of 122 articles from phase 2 were read and evaluated in light of the inclusion criteria. Of these, articles with text irrelevant to the study (109) were excluded, as the papers did not focus on CT or nurses, did not employ quantitative research design, or were published before July 2013. A final number of 13 articles were included ( Fig. 1 ).

Quality appraisal

We evaluated the included studies using assessment sheets prepared and tested by Hawker et al. [ 15 ], who developed an instrument that is capable of appraising methodologically heterogeneous studies. The data extraction sheet explores 9 components in detail: title and abstract, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, results, transferability or generalizability, and implications and usefulness. In our review, each of these areas was assessed using the criteria developed by Hawker et al. [ 15 ] and rated on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 4 (very good). The scores for each assessment were then summed to obtain an overall score and rating, which ranged from very poor (9) to very good (36). Any article scoring less than 18 was considered to be of poor to very poor quality.

Using the assessment described above, the selected studies had scores ranging from 23 to 33 out of 36. Hence, all studies were included in the review ( Table 1 ). All studies mentioned either a research question or an objective. In each article, the study design was described. Procedures or interventions were described in all studies, including three quasi-experimental studies [ 16 - 18 ]. Random sampling and purposive sampling were most commonly employed. Some studies, however, failed to state their sampling methods. Five studies determined the sample size by using power analysis [ 16 , 19 , 20 ], the Raosoft sample size calculator [ 21 ], or Solvin’s formula [ 22 ]. All studies addressed ethical considerations except for 1 study [ 23 ]; however, no studies described or elaborated on whether the researchers had received permission to use an original or translated version of the research instruments.

Studies included in the literature review

RR, response rate; CT, critical thinking; RN, registered nurse; IRB, institutional review board.

Data abstraction and synthesis

The data abstraction and synthesis process consisted of re-reading, isolating, comparing, categorizing, and relating relevant data. Included articles were read repeatedly to obtain an overall understanding of the material. Relevant data were gathered and classified into 3 categories: levels of CT, antecedents of CT, and consequences of CT.

Study selection

Our review included 13 publications ( Table 1 ). The studies were conducted in 7 different countries: Korea and the United States (n=3, for each country), Spain and Taiwan (n=2, for each country); and Malaysia, Turkey, and Egypt (n=1, for each country). The research settings were hospitals (n=6), intensive or critical care units (n=3), acute care units (n=2), and psychiatric care units (n=1). One study included nurses working in critical care and emergency units [ 24 ]. In all studies, the sample consisted of only nurses.

Study characteristics

The methodological features of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 . Twelve studies implemented quantitative research to examine the phenomenon of CT, while 1 study used a mixed-methods research approach [ 18 ]. Six of the included studies implemented a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effect of their programs on CT among clinical nurses [ 16 - 18 , 23 - 25 ]. All included studies described institutional review board approval, except for 3 studies, which either stated that researchers verbally obtained the consent of the participants to be included in the research [ 22 , 26 ] or did not mention this issue [ 23 ].

CT was evaluated employing the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory [ 21 , 22 , 24 , 26 ], Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory [ 18 , 19 ], Critical Thinking Disposition [ 17 , 20 ], Nursing Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice Questionnaire [ 27 , 28 ], Clinical Critical Thinking Skill Test [ 16 ], Health Sciences Reasoning Test (HSRT) [ 25 ], or a self-evaluation tool to measure 5 key indicators of the development of CT [ 23 ]. All studies, except for 1, utilized a validated version of the original instruments in the appropriate language or validated the instruments in their research [ 22 ]. All studies except for 3 reported internal consistency reliability [ 22 , 23 , 25 ].

Levels of critical thinking

All studies measured the levels of CT among nurses, except for 1 study [ 20 ] ( Table 1 ). Clinical nurses in 4 studies reported low [ 26 ], moderate [ 22 , 27 ], and high [ 21 ] levels of CT. Chen et al. [ 19 ] reported that experienced nurses, with an average of 18.38 years of work experience, had higher CT scores than novice registered nurses did. Similarly, Zuriguel-Perez et al. [ 28 ] reported that the level of CT among more experienced nurse managers was higher than among other nurses.

Five studies showed that their developed programs significantly improved the levels of CT among nurses in the experimental group compared to nurses in the control group [ 16 - 18 , 23 , 24 ]. One study presented a significant increase in the mean overall CT score for the HSRT on the posttest using a 1-group pretest-posttest design [ 25 ]. In particular, 5 programs—a work-based critical reflection program [ 16 ], a scenario-based simulation training program [ 17 ], case studies with videotaped vignettes [ 25 ], and concept mapping [ 23 ]—had positive effects on CT levels among novice nurses. Zori et al. [ 24 ] reported significant effects of a reflective journaling exercise to strengthen CT dispositions among nurses with diverse work experience. Hung et al. [ 18 ] developed a problem-based learning program for mental health care nurses for 3 hours every week, for a total of 5 weeks (15 hours total).

Antecedents of critical thinking

Seven studies reported inconsistent findings regarding the influence of 1 or more sociodemographic variables on CT ( Table 1 ). According to these studies, there were significant differences in CT across sociodemographic variables, including age [ 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 ], gender [ 21 ], ethnicity [ 21 ], years of experience [ 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 ], and educational level [ 21 , 28 ]. In 3 studies, older nurses, those with more clinical experience, or those with higher levels of education had higher levels of CT [ 19 , 21 , 28 ]. Although Ludin [ 21 ] reported significant differences in the levels of CT according to gender, ethnicity, and educational level, detailed information was not provided. In contrast, Mahmoud and Mohamed [ 22 ] reported that none of the sociodemographic variables or job characteristics had statistically significant relationships with the total CT disposition and, in 2 studies, there were no significant relationships between CT levels and educational level [ 26 , 27 ], years of experience [ 26 ], gender [ 27 ], or work units [ 27 ]. Nurses had higher levels of CT when they had higher levels of self-reflection [ 19 ] and lower levels of perception of barriers to research use [ 20 ].

Consequences of critical thinking

Only 1 study investigated the consequences of CT [ 20 ], and found that CT disposition of nurses positively influenced evidence-based practice ( Table 1 ). In this study, Kim et al. [ 20 ] found that the relationship between barriers to research use and evidence-based practice was mediated by CT disposition.

Methodological issues

Studies from 6 different countries were included. Most of the studies were done in Asian countries; only 2 of the studies were conducted in Europe. Synthesizing and integrating data from different countries and cultures is a complex and challenging task [ 29 ], especially since differences in cultural attitudes on CT extend beyond our expertise. The restricted professional autonomy perceived by nurses, which impeded CT, may be different for each culture or country. For instance, several studies in Asia have reported that nurses lack or have limited authority in providing care for their patients [ 30 , 31 ]; furthermore, while CT allows nurses to generate new ideas quickly, become more flexible, and act independently and confidently, the scope of their action is still ultimately limited by the physician’s clinical decisions [ 10 ]. Thus, several Asian nursing scholars have stressed the growth of professional autonomy among nurses through exercising higher levels of CT as an area that needs support to improve nurses’ clinical competence.

In the studies we reviewed, 7 different instruments were used. Due to this diversity of instruments, it was difficult to compare and integrate quantitative data. In addition, some studies utilized instruments without testing reliability and validity; thus, it is recommended to validate CT assessment instruments used in future research to ensure their reliability. A large range in sample sizes and response rates, possible non-responder bias, and validation of the instruments restricted to small populations limited the representativeness of our study results.

Substantive findings

Although the assessment tools used to measure the level of CT varied across the studies reviewed, the level of CT was mostly moderate or high among the nurses evaluated. This may be partly due to the emphasis of CT in nursing education in recent years; furthermore, CT is now recognized as an essential competency among nurses and is required for the accreditation of nursing education [ 9 , 32 ]. However, this result contrasts with other research that reported a low level of CT among nursing students [ 33 ]. Further research is needed to verify the differences between nurses and nursing students according to factors influencing CT disposition and skills.

Our review complements the results of a previous review that scoped the concept of CT in the nursing field [ 5 ]. For instance, as antecedents of CT, the association between sociodemographic variables and CT can only be revealed by quantitative studies. It is necessary to examine the relationships between them in the future since the influence of sociodemographic variables on CT was found to be inconsistent in our study, except for years of work experience, which showed a consistent association with CT capacity. This finding may be associated with the significant experience gained by more senior nurses, which complements their theoretical knowledge and clinical decision-making [ 34 ] and enables them to be capable of better reflecting on past experiences, which may foster a deeper understanding of the situation [ 19 ]. On the contrary, less-experienced nurses had difficulties in exercising CT because of their perceptions of a gap between theory and practice with reference to their education and the real workplace setting [ 16 ]. Thus, it can be useful for senior nurses to share and reflect on their successful experiences of applying CT for patient care through group discussions; meanwhile, for novice nurses, a clear and detailed approach on exercising CT to reduce the gap between theories and the clinical setting may be beneficial. For this reason, a tailored education program on CT should be developed according to nurses’ years of work experience.

Self-reflection was also significantly related to CT among nurses in our review. This finding can be explained in terms of genuine self-reflection which can help them develop their CT dispositions and skills by balancing a lack of confidence and professional autonomy [ 34 ]. CT encourages nurses to generate new ideas quickly, be flexible, and act independently and confidently [ 29 ]. In contrast, nurses’ CT becomes more limited when they are more dependent on physicians’ clinical decisions. Meanwhile, expert nurses are not confined to or constrained by theoretical knowledge and are able to interpret situations by actively utilizing their nursing care experiences with past patients through exercising CT in their decision-making process [ 9 , 40 ]. To promote and encourage CT, nurses need to be more independent, confident, and responsible. As nurses’ autonomy develops, the need to think critically is further promoted [ 29 , 33 ]. However, nurses in some nursing environments have reported limited or restricted professional autonomy due to existing rigid and hierarchical cultures, as well as physician-centered paradigms in hospitals, which can hinder nurses from exercising CT [ 35 - 38 ]. More research is required regarding autonomy and CT among nurses in relation to their perceptions of the organizational atmosphere.

Our review revealed that there is limited empirical research on the consequences of CT, since only 1 of the included studies investigated the consequences of CT. CT stimulates nurses to explore related knowledge and establish priorities for solving patients` clinical problems [ 39 ]. As a method of assessing, planning, implementing, reevaluating, and reconstructing nursing care, a CT approach encourages nurses to challenge established theory and practice [ 5 , 9 ]. In addition, good clinical judgement results from exercising CT by advancing nursing competence in contemporary healthcare environments, where the complexity of data and amount of newly developed knowledge increases daily [ 10 ]. Papathanasiou et al. [ 9 ] emphasized that nurses’ ability to find specific solutions to certain problems is easily achieved when creativity and CT work together. Nevertheless, an integrated review found no relationship between CT and clinical decision-making in nursing [ 40 ]. Further research is recommended to explore the consequences of CT in nursing.

Limitations

Despite complementing the findings of a previous scoping review [ 5 ], our review has 2 major limitations. First, a more synthesized approach should be attempted, including both quantitative and qualitative studies, in order to facilitate a more in-depth examination of our research topic. Second, access to all resources via electronic databases was not possible and only studies written in English were included in our review.

Our review highlighted the levels, antecedents, and consequences of CT among clinical nurses in various settings. Further quantitative studies are recommended using representative sample sizes and validated instruments with high and stable reliability to enhance our knowledge of this issue through optimal methodologies. Considering the significant association between years of work experience and CT capability, it would be helpful and effective for organizations to deliver a tailored education program on CT developed according to years of work experience to enhance CT among nurses when providing care for their patients. To make progress towards this goal, however, further research is needed to clarify the antecedents of CT and to explore its consequences.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: YL, YO. Data curation: YL, YO. Formal analysis: YL, YO. Funding acquisition: YO. Methodology: YL, YO. Project administration: YO. Visualization: YO. Writing–original draft: YL, YO. Writing–review & editing: YL, YO.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

This work was supported by the Hallym University Research Fund, 2020 (HRF-202007-014).

Data availability

Supplementary materials

Supplement 1. Audio recording of the abstract.

- 1. Missen K, McKenna L, Beauchamp A, Larkins JA. Qualified nurses’ rate new nursing graduates as lacking skills in key clinical areas. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2134–2143. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13316. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Lang GM, Beach NL, Patrician PA, Martin C. A cross-sectional study examining factors related to critical thinking in nursing. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2013;29:8–15. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e31827d08c8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Gezer N, Yildirim B, Ozaydin E. Factors in the critical thinking disposition and skills of intensive care nurses. J Nurs Care. 2017;6:1000390. doi: 10.4172/2167-1168.1000390. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Price B. Applying critical thinking to nursing. Nurs Stand. 2015;29:49–58. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.51.49.e10005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Zuriguel Perez E, Lluch Canut MT, Falco Pegueroles A, Puig Llobet M, Moreno Arroyo C, Roldan Merino J. Critical thinking in nursing: scoping review of the literature. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:820–830. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12347. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Tanner CA. Spock would have been a terrible nurse (and other issues related to critical thinking in nursing) J Nurs Educ. 1997;36:3–4. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19970101-03. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Gastmans C. Dignity-enhancing nursing care: a foundational ethical framework. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20:142–149. doi: 10.1177/0969733012473772. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Scheffer BK, Rubenfeld MG. A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39:352–359. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001101-06. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Papathanasiou IV, Kleisiaris CF, Fradelos EC, Kakou K, Kourkouta L. Critical thinking: the development of an essential skill for nursing students. Acta Inform Med. 2014;22:283–286. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.283-286. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Von Colln-Appling C, Giuliano D. A concept analysis of critical thinking: a guide for nurse educators. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Chan ZC. A systematic review of critical thinking in nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Yue M, Zhang M, Zhang C, Jin C. The effectiveness of concept mapping on development of critical thinking in nursing education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;52:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.02.018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . York (PA): University of York NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; 2008. p. 336. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1284–1299. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238251. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Kim YH, Min J, Kim SH, Shin S. Effects of a work-based critical reflection program for novice nurses. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:30. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1135-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Jung D, Lee SH, Kang SJ, Kim JH. Development and evaluation of a clinical simulation for new graduate nurses: a multi-site pilot study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hung TM, Tang LC, Ko CJ. How mental health nurses improve their critical thinking through problem-based learning. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2015;31:170–175. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000167. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chen FF, Chen SY, Pai HC. Self-reflection and critical thinking: the influence of professional qualifications on registered nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2019;55:59–70. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2019.1590154. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Kim SA, Song Y, Sim HS, Ahn EK, Kim JH. Mediating role of critical thinking disposition in the relationship between perceived barriers to research use and evidence-based practice. Contemp Nurse. 2015;51:16–26. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1095053. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ludin SM. Does good critical thinking equal effective decision-making among critical care nurses?: a cross-sectional survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.06.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Mahmoud AS, Mohamed HA. Critical thinking disposition among nurses working in puplic hospitals at port-said governorate. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.02.006. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Wahl SE, Thompson AM. Concept mapping in a critical care orientation program: a pilot study to develop critical thinking and decision-making skills in novice nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44:455–460. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20130916-79. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Zori S, Kohn N, Gallo K, Friedman MI. Critical thinking of registered nurses in a fellowship program. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44:374–380. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20130603-03. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Hooper BL. Using case studies and videotaped vignettes to facilitate the development of critical thinking skills in new graduate nurses. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2014;30:87–91. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Yurdanur D. Critical thinking competence and dispositions among critical care nurses: a descriptive study. Int J Caring Sci. 2016;9:489–495. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Zuriguel-Perez E, Falco-Pegueroles A, Agustino-Rodriguez S, Gomez-Martin MD, Roldan-Merino J, Lluch-Canut MT. Clinical nurses’s critical thinking level according to sociodemographic and professional variables (phase II): a correlational study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;41:102649. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102649. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Zuriguel-Perez E, Lluch-Canut MT, Agustino-Rodriguez S, Gomez-Martin MD, Roldan-Merino J, Falco-Pegueroles A. Critical thinking: a comparative analysis between nurse managers and registered nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26:1083–1090. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12640. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kim M, Oh Y, Kong B. Ethical conflicts experienced by nurses in geriatric hospitals in South Korea: “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen”. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4442. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124442. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Mousavi SR, Amini K, Ramezani-badr F, Roohani M. Correlation of happiness and professional autonomy in Iranian nurses. J Res Nurs. 2019;24:622–632. doi: 10.1177/1744987119877421. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Park IS, Suh YO, Park HS, Kang SY, Kim KS, Kim GH, Choi YH, Kim HJ. Item development process and analysis of 50 case-based items for implementation on the Korean Nursing Licensing Examination. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2017;14:20. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.20. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Kaya H, Şenyuva E, Bodur G. Developing critical thinking disposition and emotional intelligence of nursing students: a longitudinal research. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;48:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Jacob E, Duffield C, Jacob D. Development of an Australian nursing critical thinking tool using a Delphi process. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2241–2247. doi: 10.1111/jan.13732. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Aeschbacher R, Addor V. Institutional effects on nurses’ working conditions: a multi-group comparison of public and private non-profit and for-profit healthcare employers in Switzerland. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0324-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Gallego G, Dew A, Lincoln M, Bundy A, Chedid RJ, Bulkeley K, Brentnall J, Veitch C. Should I stay or should I go?: exploring the job preferences of allied health professionals working with people with disability in rural Australia. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:53. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0047-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Asif M, Jameel A, Hussain A, Hwang J, Sahito N. Linking transformational leadership with nurse-assessed adverse patient outcomes and the quality of care: assessing the role of job satisfaction and structural empowerment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132381. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Bvumbwe T. Perceptions of nursing students trained in a new model teaching ward in Malawi. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:53. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.53. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Chang SO, Kong ES, Kim CG, Kim HK, Song MS, Ahn SY, Lee YW, Cho MO, Choi KS, Kim NC. Exploring nursing education modality for facilitating undergraduate students’ critical thinking: focus group interview analysis. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2013;25:125–135. doi: 10.7475/kjan.2013.25.1.125. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Lee DS, Abdullah KL, Subramanian P, Bachmann RT, Ong SL. An integrated review of the correlation between critical thinking ability and clinical decision-making in nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4065–4079. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13901. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (785.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Critical thinking competence and disposition of clinical nurses in a medical center

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Nursing, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan, ROC.

- PMID: 20592653

- DOI: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181dda6f6

Background: Critical thinking is essential in nursing practice. Promoting critical thinking competence in clinical nurses is an important way to improve problem solving and decision-making competence to further improve the quality of patient care. However, using an adequate tool to test nurses' critical thinking competence and disposition may provide the reference criteria for clinical nurse characterization, training planning, and resource allocation for human resource management.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to measure the critical thinking competence and critical thinking disposition of clinical nurses as well as to explore the related factors of critical thinking competence.

Methods: Clinical nurses from four different clinical ladders selected from one medical center were stratified randomly. All qualified subjects who submitted valid questionnaires were included in the study. A Taiwan version of the modified Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal and Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was developed to measure the critical thinking competence and critical thinking disposition of clinical nurses. Validity was evaluated using the professional content test (content validity index = .93). Reliability was assessed with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of .85. Data were analyzed using the SPSS for Windows (Version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results: Results showed that competence of interpretation was the highest critical thinking competence factor. Inference was the lowest, and reflective thinking as a critical thinking disposition was more positive. In addition, age, years of nursing experience, and experiences in other hospitals significantly influenced critical thinking competence (p < .05). Factors of age, years of experience, and nurses clinical ladder were shown to affect critical thinking disposition scores. Clinical ladder N4 nurses had the highest scores in both competence and disposition. A significant relationship was found between critical thinking competence and disposition scores, with 29.3% of the variance in critical thinking competence potentially explained by total years of nurse hospital experience. Clinical ladder and age were predictive factors for critical thinking disposition. Commonality was 27.9%.

Conclusions and implications for practice: Nursing experience and clinical ladders positively affect critical thinking competence and disposition. Issues of critical thinking competence increasingly need to be measured. Therefore, appropriate tools for nursing professions should be further developed and explored for specific areas of practice.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Nurses / psychology*

- Professional Competence*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2023

Effectiveness of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators: a pilot study

- Sujin Shin 1 ,

- Inyoung Lee 2 ,

- Jeonghyun Kim 3 ,

- Eunyoung Oh 4 &

- Eunmin Hong 1

BMC Nursing volume 22 , Article number: 69 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

9 Citations

Metrics details

Critical reflection is an effective learning strategy that enhances clinical nurses’ reflective practice and professionalism. Therefore, training programs for nurse educators should be implemented so that critical reflection can be applied to nursing education. This study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

A pilot study was conducted using a pre- and post-test control-group design. Participants were clinical nurse educators recruited using a convenience sampling method. The program was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. The effectiveness of the developed program was verified by analyzing pre- and post-test results of 26 participants in the intervention group and 27 participants in the control group, respectively. The chi-square test, independent t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and analysis of covariance with age as a covariate were conducted.

The critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of the intervention group improved after the program, and the differences between the control and intervention groups were statistically significant (F = 14.751, p < 0.001; F = 11.047, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the change in nursing reflection competency between the two groups (F = 2.674, p = 0.108).

The critical reflection competency program was effective in improving the critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. Therefore, it is necessary to implement the developed program for nurse educators to effectively utilize critical reflection in nursing education.

Peer Review reports

The critical thinking of clinical nurses is essential for identifying the needs of patients and providing safe care through prompt and accurate judgment [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Critical thinking can be practiced through critical reflection [ 4 ], a dynamic process in which nurses reflect on their nursing behavior to improve their perspective on a situation and change future nursing practices in a desirable direction [ 5 ]. Through critical reflection, nurses grasp the contextual meaning of a situation and reconstruct their experiences to apply their learning in practice, thereby identifying the meaning of nursing [ 3 ]. In other words, critical reflection can help nurses convert their experiences into practical knowledge [ 6 ]. Thus, critical reflection may be an effective learning strategy linking theory and practice in clinical nursing education [ 7 ].

Studies have reported that critical reflection is effective in improving nurses’ reflective practices and professionalism. Teaching methods that use critical reflection can improve nurses’ knowledge, communication skills, and critical thinking abilities [ 1 , 8 , 9 ]. These methods can be effective in improving clinical judgment and problem-solving abilities by providing new nurses with opportunities to apply their theoretical knowledge in clinical practice [ 10 , 11 ]. In addition, critical reflection has positive effects on the professionalism of new graduate nurses and reduces reality shock during the transition from university to clinical practice [ 12 ]. These advantages have led to the increasing application of critical reflection in training programs for new graduate nurses, including nursing residency programs [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

In order to facilitate new nurses’ reflective thinking and practice by clinical nurse educators, educators must be trained to strengthen their critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy competency. Educators help new nurses adapt and develop their expertise in clinical settings [ 16 , 17 ]. Moreover, continuing education for nurses to improve their teaching competency relates to the satisfaction of learners and nurse educators, which improves the quality of clinical nursing education [ 18 ]. Therefore, opportunities for nurse educators to develop teaching competency for critical reflection in education should be provided [ 19 ] and educational support for nurse educators to improve critical reflection competency is needed.

However, although there have been studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of the educational interventions concerning critical reflection to new nurses, few studies have been conducted on educational interventions on the critical reflection competencies of clinical nurse educators in charge of educating new nurses. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

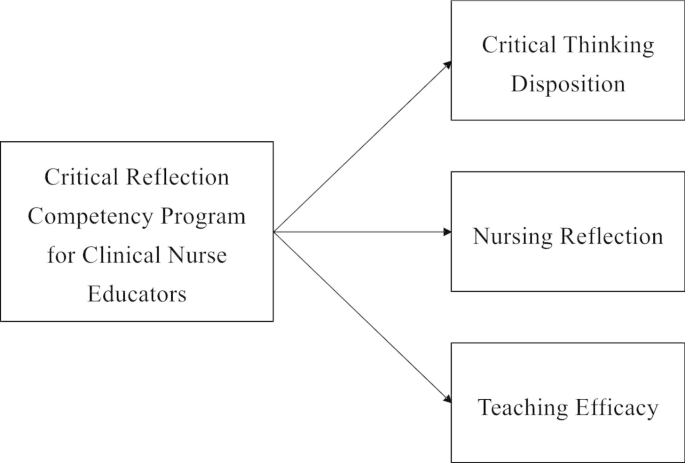

Study design

A pilot study was conducted with a pre- and post-test control group design to investigate the effects of the critical reflection competency program on the critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. The conceptual framework in this study was proposed that the critical reflection competency program will improve critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection, and teaching efficacy of clinical nurse educators [Fig. 1 ].

Conceptual Framework

Participants were clinical nurse educators in hospitals who were recruited using a convenience sampling method. Nurse educators were eligible to participate if they had dedicated nursing education in a clinical setting. They dedicated to nursing education focused on staff development of current nurses, especially the education for new nurses. They also included those who completed all four sessions of the program and participated in the data collection before and after the program. A recruitment document was sent to hospitals to recruit the participants, hospitals were selected with concerning role of clinical nurse educators. Participants were recruited from two hospitals of different sizes and the number of participants differed for each hospital, and they were allocated according to the order of registration.

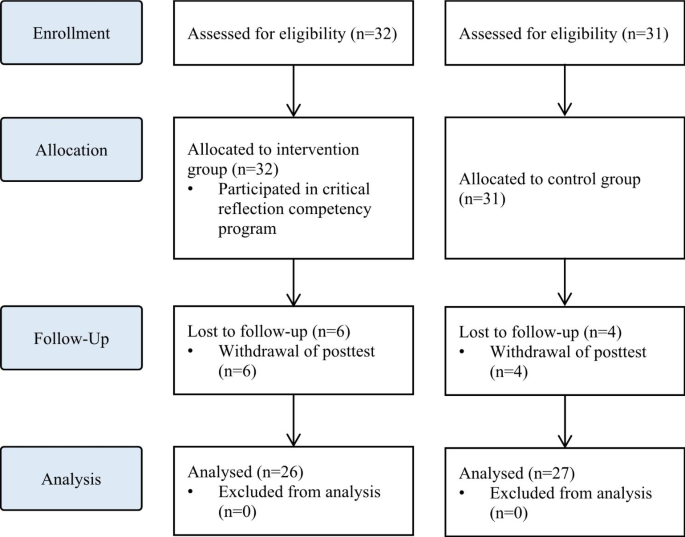

The sample size required for the analysis was calculated using the G* Power 3.1.9.4. program with an effect size of 0.80, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80, following the literature [ 20 ]. By applying a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses [ 20 ], we calculated the effect size as large. Both the intervention and control groups required 26 participants. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, a total of 63 participants, including 32 in the intervention group and 31 in the control group, were recruited. From the intervention group, six participants who participated in the pre-test and completed all programs, but did not participate in the post-test, were excluded. In the control group, four participants who participated in the pre-test but not in the post-test were excluded. Thus, 26 and 27 participants in the intervention and control groups, respectively, were included in the final analysis [Fig. 2 ]. The pre-test for both groups was conducted in May 2021. Post-tests for the two groups were performed four weeks after the pre-test.

Flowchart of the study

Intervention

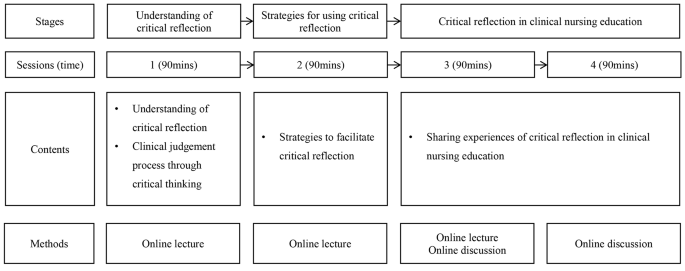

The intervention was developed and delivered by the first author, who has more than 15 years of teaching experience in nursing education, including critical reflection. The intervention was conducted between May 2021 and June 2021. Following previous studies that applied critical reflection in medical education [ 21 , 22 ], the intervention was conducted once a week for 90 min, with a total of four sessions. Owing to COVID-19, real-time online sessions were used to minimize contact between participants working in medical institutions. Every week before the sessions, the contents of the session, schedule, and Uniform Resource Locator (URL) were sent to participants via e-mail.

The intervention consisted of the following three steps in four sessions: (1) understanding critical reflection, (2) strategies to use critical reflection, and (3) practical uses of critical reflection [Fig. 3 ]. Synchronous online lectures were conducted in the first and second sessions. The contents of the first session included understanding of critical reflection and the clinical judgment process through critical reflection. Based on the content of the first session, the second outlined educational strategies using critical reflection in nursing education and the direction of critical reflection. In the third and fourth sessions, clinical nurses with experience of critically reflecting on themselves were invited as guest speakers to share their experiences and facilitate online discussions. Online discussions were also conducted in real time, and feedback from guest speakers and the author was immediately provided.

Critical reflection program for clinical nurse educators

Online self-report surveys were conducted before and after the program to assess the program’s effects. In both pre- and post-tests, critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy were assessed, as well as information about participants, such as gender, age, experience in nursing education, and the type of institution and the number of beds they affiliated with.

Critical thinking disposition was measured using Yoon’s Critical Thinking Disposition Scale [ 23 ]. This scale comprises 27 items: 5 on “intellectual eagerness/curiosity,” 4 on “prudence,” 4 on “self-confidence,” 3 on “systematicity,” 4 on “intellectual fairness,” 4 on “healthy skepticism,” and 3 on “objectivity.” The items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”); a higher score indicated greater critical thinking disposition. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Nursing reflection competency was assessed using the Nursing-Reflection Questionnaire, developed by Lee et al. [ 24 ]. This scale comprises four factors with 15 items, including 6 items on “review and analysis nursing behavior,” 5 on “development-oriented deliberative engagement,” 2 on “objective self-awareness,” and 2 on “contemplation of behavioral change.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater nursing reflection competency. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Teaching efficacy was evaluated using the Teaching Efficacy Scale developed by Park and Suh [ 25 ] to evaluate clinical nursing instructors. This scale consisted of six sub-factors with 42 items, including 12 items on “student instruction,” 9 on “teaching improvement,” 7 on “application of teaching and learning,” 7 on “interpersonal relationship and communication,” 4 on “clinical judgment,” and 3 on “clinical skill instruction.” Each item was evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (one point for “strongly disagree” to five points for “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating greater teaching efficacy. The scale has good reliability as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97 at the time of the development versus the reliability of the scale in this study was Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University (IRB no. ewha-202105-0022-02). The need of written informed consent was exempted by IRB of Ewha Womans University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A description of the study, including its purpose, methods, and procedures, was posted on an online pre-test survey. Only those participants who agreed to participate were allowed to complete the questionnaire. The participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that the data of withdrawn participants would not be included in the final analysis. After the survey was completed, a mobile gift voucher was provided to those who agreed to provide their mobile phone number. Data were collected by researchers who did not participate in the program.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 28.0). Non-normally distributed data were analyzed using non-parametric tests. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation of participants’ general and institutional characteristics. Chi-square, independent t-, and Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to test the homogeneity of the general characteristics and pre-test scores. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to test the normality of the data. To test the difference between the pre- and post-tests for each group, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. As there was a significant difference in age between the intervention and control groups, an ANCOVA with age as a covariate was conducted for the difference in changes in test scores between the pre- and post-test.

Homogeneity test of general characteristics and dependent variables

All participants were female, with a mean nursing education experience of 27 and 23 months in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The homogeneity test of general and institutional characteristics, such as gender, nursing education experience, affiliated institution types, and the number of beds, were not statistically significant. However, the age differed significantly between the two groups. In the test for homogeneity of the pre-intervention scores, there were no significant differences in critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, or teaching efficacy between the two groups, suggesting homogeneity of the dependent variables between the groups [Table 1 ].

Effects of critical reflection competency program

The effects of the critical reflection competency program are shown in Table 2 .

In the post-intervention phase, scores of critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy all improved compared to the pre-intervention phase, and were higher in the experimental group than in the control group. The critical thinking disposition scores before and after the intervention were 3.61 ± 0.26 vs. 3.87 ± 0.04 in the intervention group and 3.76 ± 0.21 vs. 3.77 ± 0.04 in the control group, respectively. The nursing reflection competency scores before and after the intervention were 57.00 ± 3.42 vs. 60.86 ± 0.95 in the intervention group and 59.63 ± 5.24 vs. 59.04 ± 0.89 in the control group. The teaching efficacy scores before and after the intervention were 157.04 ± 10.60 vs. 171.98 ± 2.54 in the intervention group and 161.59 ± 14.77 vs. 160.48 ± 2.46 in the control group.

Age, which was significantly different between the intervention and control groups, was treated as a covariate to conduct the ANCOVA. The changes in critical thinking disposition (F = 14.751, p < 0.001) and teaching efficacy (F = 11.047, p < 0.001) scores were significantly different between the two groups. However, there was no significant difference in the change in the nursing reflection competency (F = 2.674, p = 0.108) score between the two groups.

Reflective practice is crucial to clinical nurses’ professionalism. Reflective practice enables positive learning experiences through deep and meaningful learning, and is essential for integrating theory and practice. It also enables nurses to implement what they have learned into practice, understand their expertise, and develop clinical competencies [ 26 ]. In this respect, it is important for clinical nursing educators to have critical reflection competencies and promote experiential learning among new nurses. In this study, a critical reflection competency program was developed to enhance clinical nurse educators’ critical thinking and teaching competency.

This program was effective in improving critical thinking disposition. In interventions for critical reflection, various aspects, including the introduction of critical reflection and guidelines to promote critical reflection, such as small group discussions and feedback, can be considered [ 27 ]. The program reflected these aspects and helped improve participants’ critical thinking disposition. In the third and fourth sessions, synchronous discussions on sharing experiences of critical reflection were effective. This is consistent with previous studies in which discussions improved reflective competencies [ 21 , 28 ]. Therefore, sharing experiences in the discussion section should be a key element of future educational interventions for critical reflection competency.

Furthermore, the program was effective in improving teaching efficacy. Teaching efficacy is the instructor’s belief in one’s own ability to organize and implement teaching [ 29 ], and is closely related to age, clinical experience, educational experience, professional development, and teaching competency [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Nurses who are more clearly aware of their roles as instructors tend to exhibit higher confidence in their teaching abilities [ 33 , 34 ]. That is, the participants in this study were clearly aware of their roles and developed confidence by sharing their educational experiences about critical reflection.

However, the program did not have a significant effect on nursing reflection competencies. In a previous study [ 10 ], reflective practitioners (RPs) received four weeks of critical reflection training and trained new nurses for six months. During training, new nurses wrote critical reflective journals and RPs provided feedback and shared their experiences. In this study, it seems that the methods and frequency of using critical reflection in nursing education varied for each participant, resulting in insignificant results for nursing reflection competency. It is necessary to provide educational materials or guidelines so that nurse educators can use critical reflection in nursing education.

In this pilot study, the program was found to be effective in improving critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy. The results show that the program can enhance the critical thinking disposition of nurse educators and help them develop teaching competency by critically reflecting on their educational experiences as instructors [ 35 , 36 ]. Therefore, various educational programs and training systems related to critical reflection are required [ 37 ]. However, many medical institutions find it difficult to provide sufficient educational support to nurses because of limited costs, time, and physical space [ 38 ]. Online real-time lectures and case-based discussions of the developed program can be useful alternatives to overcome barriers to nursing education support. Additionally, more effective educational content and platforms using e-learning can be developed based on the results of this study.

In this study, the critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators was developed and conducted. The program was an educational intervention to improve the critical reflection competency of clinical nurse educators in real time online. Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the present findings. The developed program did not affect nursing reflection competencies. Further, the post-test was conducted shortly after program completion. Therefore, there may be limitations to evaluating whether the developed program improves the quality of nursing education. In addition, the participants in this study were allocated regardless of their hospital’s characteristics. Considering variables such as the size of the hospitals, the number of new nurses, and the number of participants per hospital, it is necessary to assign nurse educators the intervention and control groups and to verify the effects of the program. Future studies should consider improving the study design to measure the long-term effects of the program and randomize the participants.

The effects of the program on critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy were assessed. The results showed that the program was effective in improving the critical thinking disposition and teaching efficacy of nurse educators. However, there was no significant difference in nursing reflection competency, but it may vary depending on the methods or time of using critical reflection in nursing education. Therefore, it is necessary to provide the critical reflection utilization strategies that can be used by clinical nurse educators in the clinical settings. In addition, further research, such as evaluating the reflective practice of new nurses trained by clinical nurse educators, is needed. This suggests that the critical reflection competency program should be expanded in the future for nurse educators. It is necessary to develop e-learning content and educational platforms to expand the program, and it should be possible to share the experience of critical reflection in various forms. Also, sufficient support for competency improvement of nurse educators is needed to effectively use critical reflection in nursing education. Nursing leaders in hospital and healthcare settings should recognize the importance of using critical reflection in clinical practice and improving the competency of clinical nursing educators who educate new nurses, and make efforts to improve the quality of nursing education through support for these. Lastly, based on the results of this study, we recommend further longitudinal and randomized studies to evaluate additional effects of the program.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Kim YH, Min J, Kim SH, Shin S. Effects of a work-based critical reflection program for novice nurses. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1135-0 .

Article Google Scholar

Alfaro-LeFevre R. Critical thinking in nursing: a practical approach. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1995.

Google Scholar

Do J, Shin S, Lee I, Jung Y, Hong E, Lee MS. Qualitative content analysis on critical reflection of clinical nurses. J Qual Res. 2021;22:86–96. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2021.22.86 .

Burrell LA. Integrating critical thinking strategies into nursing curricula. Teach Learn Nurs. 2014;9:53–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2013.12.005 .

Lee M, Jang K. Reflection-related research in korean nursing: a literature review. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2019;25:83–96. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2019.25.2 .

Cox K. Planning bedside teaching. Med J Aust. 1993;158:280–2. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137586.x .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Klaeson K, Berglund M, Gustavsson S. The character of nursing students’ critical reflection at the end of their education. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2017;7:55–61. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v7n5p55 .

Pangh B, Jouybari L, Vakili MA, Sanagoo A, Torik A. The effect of reflection on nurse-patient communication skills in emergency medical centers. J Caring Sci. 2019;8:75–81. https://doi.org/10.15171/jcs.2019.011 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Liu K, Ball AF. Critical reflection and generativity: toward a framework of transformative teacher education for diverse learners. Rev Res Educ. 2019;43:68–105. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18822806 .

Shin S, Kim SH. Experience of novice nurses participating in critical reflection program. J Qual Res. 2019;20:60–7. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2018.20.1.60 .

Lee M, Jang K. The significance and application of reflective practice in nursing practice. J Nurs Health Issues. 2018;23:1–8.

Monagle JL, Lasater K, Stoyles S, Dieckmann N. New graduate nurse experiences in clinical judgment: what academic and practice educators need to know. Nurs Educ Pers. 2018;39:201–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000336 .

Bull R, Shearer T, Youl L, Campbell S. Enhancing graduate nurse transition: report of the evaluation of the clinical honors program. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2018;49:348–55. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180718-05 .

Cadmus E, Salmond SW, Hassler LJ, Black K, Bohnarczyk N. Creating a long-term care new nurse residency model. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2016;47:234–40. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20160419-10 .

Johansson A, Berglund M, Kjellsdotter A. Clinical nursing introduction program for new graduate nurses in Sweden: study protocol for a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ open. 2021;11:e042385. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042385 .

Salminen L, Minna S, Sanna K, Jouko K, Helena LK. The competence and the cooperation of nurse educators. Nurse Educ Today., 2013;33:1376–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.09.008 .

Zlatanovic T, Havnes A, Mausethagen S. A research review of nurse teachers’ competencies. Vocations Learn. 2017;10:201 − 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9169-0 .

Shinners JS, Franqueiro T. Preceptor skills and characteristics: considerations for preceptor education. J Cont Educ Nurs. 2015;46:233–6. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20150420-04 .

Sheppard-Law S, Curtis S, Bancroft J, Smith W, Fernandez R. Novice clinical nurse educator’s experience of a self-directed learning, education and mentoring program: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurs. 2018;54:208–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2018.1482222 .

Kang HJ, Bang KS. Development and evaluation of a self-reflection program for intensive care unit nurses who have experienced the death of pediatric patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2017;47:392-405. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2017.47.3.392 .

Hayton A, Kang I, Wong R, Loo LK. Teaching medical students to reflect more deeply. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:410-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2015.1077124 .

Spampinato CM, Wittich CM, Beckman TJ, Cha SS, Pawlina W. Safe Harbor”: evaluation of a professionalism case discussion intervention for the gross anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:191–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yoon J. Development of an instrument for the measurement of critical thinking disposition: In nursing[dissertation]. Seoul: Catholic University; 2004.

Lee H. Development and psychometric evaluation of nursing-reflection questionnaire [dissertation]. Seoul: Korea University; 2020.

Park I, Suh YO. Development of teaching efficacy scale to evaluate clinical nursing instructors. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;30:18–29. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2018.30.1.18 .

Froneman K, du Plessis E, van Graan AC. Conceptual model for nurse educators to facilitate their presence in large class groups of nursing students through reflective practices: a theory synthesis. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01095-7 .

Uygur J, Stuart E, De Paor M, Wallace E, Duffy S, O’Shea M, Smith S, Pawlikowska T. A best evidence in medical education systematic review to determine the most effective teaching methods that develop reflection in medical students. BEME Guide No 51 Med Teach. 2019;41:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1505037 .

McEvoy M, Pollack S, Dyche L, Burton W. Near-peer role modeling: can fourth-year medical students, recognized for their humanism, enhance reflection among second-year students in a physical diagnosis course? Med Educ Online. 2016;21:31940. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.31940 .

Poulou M. Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: student teachers’ perceptions. Educ Psychol. 2007;27:191–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601066693 .

Klopfer BC, Piech EM. Characteristics of effective nurse educators. Sigma Theta Tau International: Leadership Connection 2016; 2016.

Dozier AL. An investigation of nursing faculty teacher efficacy in nursing schools in Georgia. ABNF J. 2019;30:50–7.

Kim EK, Shin S. Teaching efficacy of nurses in clinical practice education: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;54:64–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.017 .

Wu XV, Chi Y, Selvam UP, Devi MK, Wang W, Chan YS, Wee FC, Zhao S, Sehgal V, Ang NKE. A clinical teaching blended learning program to enhance registered nurse preceptors’ teaching competencies: Pretest and posttest study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e18604. https://doi.org/10.2196/18604 .

Larsen R, Zahner SJ. The impact of web-delivered education on preceptor role self-efficacy and knowledge in public health nurses. Public Health Nurs. 2011;28:349–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00933.x .

Armstrong DK, Asselin ME. Supporting faculty during pedagogical change through reflective teaching practice: an innovative approach. Nurs Educ Pers. 2017;38:354–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000153 .

Raymond C, Profetto-McGrath J, Myrick F, Strean WB. Balancing the seen and unseen: nurse educator as role model for critical thinking. Nurse Educ Prac. 2018;31:41–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.04.010 .

Parrish DR, Crookes K. Designing and implementing reflective practice programs–key principles and considerations. Nurse Educ Prac. 2014;14:265–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.002 .

Glogowska M, Young P, Lockyer L, Moule P. How ‘blended’ is blended learning?: students’ perceptions of issues around the integration of online and face-to-face learning in a continuing professional development (CPD) health care context. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:887–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.02.003 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A1057096).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Nursing, Ewha Womans University, 52 Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, 03760, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Sujin Shin & Eunmin Hong

Department of Nursing, Dongnam Health University, 50, Cheoncheon-ro 74beon-gil, Jangan-gu, Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Inyoung Lee

College of Nursing, Catholic University of Pusan, 57 Oryundae-ro, Geumjeong-gu, 46252, Busan, Republic of Korea

Jeonghyun Kim

Department of Nursing, Nursing Administration Education Team Leader, Catholic University of Korea Bucheon ST. Mary’s Hospital, 327, Sosa-ro, 14647, Bucheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

Eunyoung Oh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Project administration. IL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EO: Data curation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eunmin Hong .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University (IRB no. ewha-202105-0022-02). The need of written informed consent was exempted by IRB of Ewha Womans University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shin, S., Lee, I., Kim, J. et al. Effectiveness of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators: a pilot study. BMC Nurs 22 , 69 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01236-6

Download citation

Received : 12 December 2022

Accepted : 07 March 2023

Published : 16 March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01236-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Education professional

- Nursing education research

- Program evaluation

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

COMMENTS

Results: The clinical nurses surveyed showed a positive inclination to general critical thinking but reported an overall low level of nursing research competence. A moderate degree of positive correlation was found between critical thinking disposition and research competence among clinical nurses.

Open in a new tab. Critical thinking dispositions among newly graduated nurses in Norway (n = 614). Per cent of respondents (y -axis) with high and low scores for subscales* and total score † (x -axis) are shown graphically. *High critical thinking subscale scores i.e.strong disposition >50 and positive inclination 40–50, and low critical ...

In this review, we addressed the following specific research questions: what are the levels of critical thinking among clinical nurses?; what are the antecedents of critical thinking?; and what are the consequences of critical thinking?

Promoting critical thinking competence in clinical nurses is an important way to improve problem solving and decision-making competence to further improve the quality of patient care.

Based on existing findings, we theorized that hospital ethical climate and nursing task performance may be related in a pathway through critical thinking disposition among nurses with one year of experience in a clinical setting.

Participants completed a modified version of the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory, designed to measure the following characteristics of critical thinking: inquisitiveness, systematic analytical approach, open mindedness, and reflective thinking.

Promoting critical thinking competence in clinical nurses is an important way to improve problem solving and decision-making competence to further improve the quality of patient care.

The ability to clinically reason develops over time and is based on knowledge and experience. Inductive and deductive reasoning are important critical thinking skills. They help the nurse use clinical judgment when implementing the nursing process. Effective thinking in nursing involves the integration of clinical knowledge and critical ...

This study aimed to investigate the effects of a critical reflection competency program for clinical nurse educators on improving critical thinking disposition, nursing reflection competency, and teaching efficacy.

The critical thinking disposition of clinical nurses is positively related to their research competence. Relevance to clinical practice. Nurses with a passion for nursing research should pay attention to improving their critical thinking dispositions.