When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

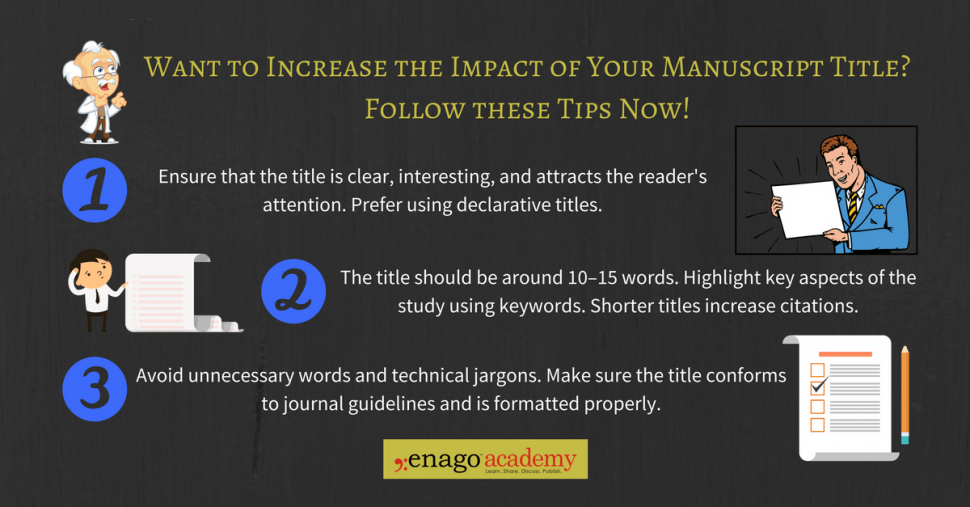

- How to Write a Great Title

Maximize search-ability and engage your readers from the very beginning

Your title is the first thing anyone who reads your article is going to see, and for many it will be where they stop reading. Learn how to write a title that helps readers find your article, draws your audience in and sets the stage for your research!

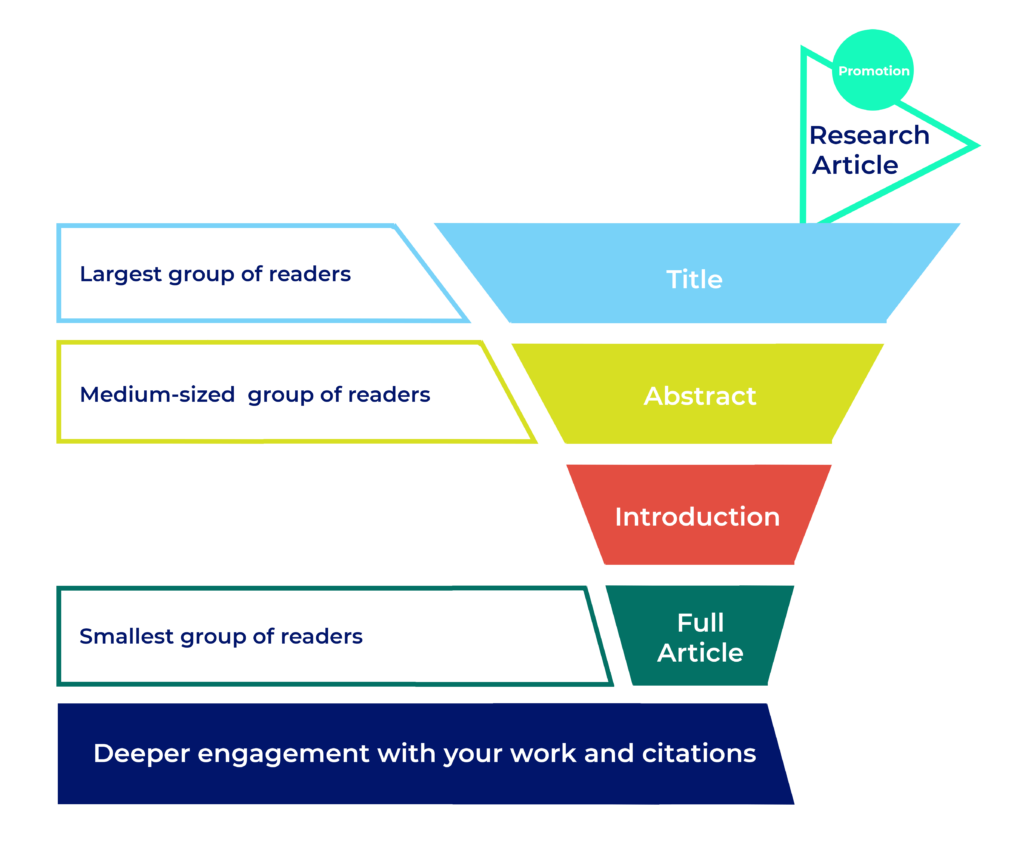

How your title impacts the success of your article

Researchers are busy and there will always be more articles to read than time to read them. Good titles help readers find your research, and decide whether to keep reading. Search engines use titles to retrieve relevant articles based on users’ keyword searches. Once readers find your article, they’ll use the title as the first filter to decide whether your research is what they’re looking for. A strong and specific title is the first step toward citations, inclusion in meta-analyses, and influencing your field.

What to include in a title

Include the most important information that will signal to your target audience that they should keep reading.

Key information about the study design

Important keywords

What you discovered

Writing tips

Getting the title right can be more difficult than it seems, and researchers refine their writing skills throughout their career. Some journals even help editors to re-write their titles during the publication process!

- Keep it concise and informative What’s appropriate for titles varies greatly across disciplines. Take a look at some articles published in your field, and check the journal guidelines for character limits. Aim for fewer than 12 words, and check for journal specific word limits.

- Write for your audience Consider who your primary audience is: are they specialists in your specific field, are they cross-disciplinary, are they non-specialists?

- Entice the reader Find a way to pique your readers’ interest, give them enough information to keep them reading.

- Incorporate important keywords Consider what about your article will be most interesting to your audience: Most readers come to an article from a search engine, so take some time and include the important ones in your title!

- Write in sentence case In scientific writing, titles are given in sentence case. Capitalize only the first word of the text, proper nouns, and genus names. See our examples below.

Don’t

- Write your title as a question In most cases, you shouldn’t need to frame your title as a question. You have the answers, you know what you found. Writing your title as a question might draw your readers in, but it’s more likely to put them off.

- Sensationalize your research Be honest with yourself about what you truly discovered. A sensationalized or dramatic title might make a few extra people read a bit further into your article, but you don’t want them disappointed when they get to the results.

Examples…

Format: Prevalence of [disease] in [population] in [location]

Example: Prevalence of tuberculosis in homeless women in San Francisco

Format: Risk factors for [condition] among [population] in [location]

Example: Risk factors for preterm births among low-income women in Mexico City

Format (systematic review/meta-analysis): Effectiveness of [treatment] for [disease] in [population] for [outcome] : A systematic review and meta-analysis

Example: Effectiveness of Hepatitis B treatment in HIV-infected adolescents in the prevention of liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Format (clinical trial): [Intervention] improved [symptoms] of [disease] in [population] : A randomized controlled clinical trial

Example: Using a sleep app lessened insomnia in post-menopausal women in southwest United States: A randomized controlled clinical trial

Format (general molecular studies): Characterization/identification/evaluation of [molecule name] in/from [organism/tissue] (b y [specific biological methods] )

Example: Identification of putative Type-I sex pheromone biosynthesis-related genes expressed in the female pheromone gland of Streltzoviella insularis

Format (general molecular studies): [specific methods/analysis] of organism/tissue reveal insights into [function/role] of [molecule name] in [biological process]

Example: Transcriptome landscape of Rafflesia cantleyi floral buds reveals insights into the roles of transcription factors and phytohormones in flower development

Format (software/method papers): [tool/method/software] for [what purpose] in [what research area]

Example: CRISPR-based tools for targeted transcriptional and epigenetic regulation in plants

Tip: How to edit your work

Editing is challenging, especially if you are acting as both a writer and an editor. Read our guidelines for advice on how to refine your work, including useful tips for setting your intentions, re-review, and consultation with colleagues.

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Make a Research Paper Title with Examples

What is a research paper title and why does it matter?

A research paper title summarizes the aim and purpose of your research study. Making a title for your research is one of the most important decisions when writing an article to publish in journals. The research title is the first thing that journal editors and reviewers see when they look at your paper and the only piece of information that fellow researchers will see in a database or search engine query. Good titles that are concise and contain all the relevant terms have been shown to increase citation counts and Altmetric scores .

Therefore, when you title research work, make sure it captures all of the relevant aspects of your study, including the specific topic and problem being investigated. It also should present these elements in a way that is accessible and will captivate readers. Follow these steps to learn how to make a good research title for your work.

How to Make a Research Paper Title in 5 Steps

You might wonder how you are supposed to pick a title from all the content that your manuscript contains—how are you supposed to choose? What will make your research paper title come up in search engines and what will make the people in your field read it?

In a nutshell, your research title should accurately capture what you have done, it should sound interesting to the people who work on the same or a similar topic, and it should contain the important title keywords that other researchers use when looking for literature in databases. To make the title writing process as simple as possible, we have broken it down into 5 simple steps.

Step 1: Answer some key questions about your research paper

What does your paper seek to answer and what does it accomplish? Try to answer these questions as briefly as possible. You can create these questions by going through each section of your paper and finding the MOST relevant information to make a research title.

| “What is my paper about?” | |

| “What methods/techniques did I use to perform my study? | |

| “What or who was the subject of my study?” | |

| “What did I find?” |

Step 2: Identify research study keywords

Now that you have answers to your research questions, find the most important parts of these responses and make these your study keywords. Note that you should only choose the most important terms for your keywords–journals usually request anywhere from 3 to 8 keywords maximum.

| -program volume -liver transplant patients -waiting lists -outcomes | |

| -case study | |

-US/age 20-50 -60 cases | |

-positive correlation between waitlist volume and negative outcomes |

Step 3: Research title writing: use these keywords

“We employed a case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years to assess how waiting list volume affects the outcomes of liver transplantation in patients; results indicate a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and negative prognosis after the transplant procedure.”

The sentence above is clearly much too long for a research paper title. This is why you will trim and polish your title in the next two steps.

Step 4: Create a working research paper title

To create a working title, remove elements that make it a complete “sentence” but keep everything that is important to what the study is about. Delete all unnecessary and redundant words that are not central to the study or that researchers would most likely not use in a database search.

“ We employed a case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years to assess how the waiting list volume affects the outcome of liver transplantation in patients ; results indicate a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis after transplant procedure ”

Now shift some words around for proper syntax and rephrase it a bit to shorten the length and make it leaner and more natural. What you are left with is:

“A case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcome of transplantation and showing a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis” (Word Count: 38)

This text is getting closer to what we want in a research title, which is just the most important information. But note that the word count for this working title is still 38 words, whereas the average length of published journal article titles is 16 words or fewer. Therefore, we should eliminate some words and phrases that are not essential to this title.

Step 5: Remove any nonessential words and phrases from your title

Because the number of patients studied and the exact outcome are not the most essential parts of this paper, remove these elements first:

“A case study of 60 liver transplant patients around the US aged 20-50 years assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcomes of transplantation and showing a positive correlation between increased waiting list volume and a negative prognosis” (Word Count: 19)

In addition, the methods used in a study are not usually the most searched-for keywords in databases and represent additional details that you may want to remove to make your title leaner. So what is left is:

“Assessing the impact of waiting list volume on outcome and prognosis in liver transplantation patients” (Word Count: 15)

In this final version of the title, one can immediately recognize the subject and what objectives the study aims to achieve. Note that the most important terms appear at the beginning and end of the title: “Assessing,” which is the main action of the study, is placed at the beginning; and “liver transplantation patients,” the specific subject of the study, is placed at the end.

This will aid significantly in your research paper title being found in search engines and database queries, which means that a lot more researchers will be able to locate your article once it is published. In fact, a 2014 review of more than 150,000 papers submitted to the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF) database found the style of a paper’s title impacted the number of citations it would typically receive. In most disciplines, articles with shorter, more concise titles yielded more citations.

Adding a Research Paper Subtitle

If your title might require a subtitle to provide more immediate details about your methodology or sample, you can do this by adding this information after a colon:

“ : a case study of US adult patients ages 20-25”

If we abide strictly by our word count rule this may not be necessary or recommended. But every journal has its own standard formatting and style guidelines for research paper titles, so it is a good idea to be aware of the specific journal author instructions , not just when you write the manuscript but also to decide how to create a good title for it.

Research Paper Title Examples

The title examples in the following table illustrate how a title can be interesting but incomplete, complete by uninteresting, complete and interesting but too informal in tone, or some other combination of these. A good research paper title should meet all the requirements in the four columns below.

| Advantages of Meditation for Nurses: A Longitudinal Study | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Why Focused Nurses Have the Highest Nursing Results | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| A Meditation Study Aimed at Hospital Nurses | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Mindfulness on the Night Shift: A Longitudinal Study on the Impacts of Meditation on Nurse Productivity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Injective Mindfulness: Quantitative Measurements of Medication on Nurse Productivity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Tips on Formulating a Good Research Paper Title

In addition to the steps given above, there are a few other important things you want to keep in mind when it comes to how to write a research paper title, regarding formatting, word count, and content:

- Write the title after you’ve written your paper and abstract

- Include all of the essential terms in your paper

- Keep it short and to the point (~16 words or fewer)

- Avoid unnecessary jargon and abbreviations

- Use keywords that capture the content of your paper

- Never include a period at the end—your title is NOT a sentence

Research Paper Writing Resources

We hope this article has been helpful in teaching you how to craft your research paper title. But you might still want to dig deeper into different journal title formats and categories that might be more suitable for specific article types or need help with writing a cover letter for your manuscript submission.

In addition to getting English proofreading services , including paper editing services , before submission to journals, be sure to visit our academic resources papers. Here you can find dozens of articles on manuscript writing, from drafting an outline to finding a target journal to submit to.

What Makes a Good Research Article Title?

What-makes-a-good-research-article-title.

Helen Eassom, Copywriter, Wiley

November 16, 2017

Your title is your first opportunity to draw in readers, so you must ensure that it makes an impact. Compared to the work you put in to the full paper, the title may feel like an afterthought, but creating a good title is essential to maximizing the reach of your article.

Your final title should do several things to draw readers into your article. Consider these basics of title creation to come up with a few ideas:

- Limit yourself to 10 to 20 substantial words.

- Devise a phrase or ask a question.

- Make a positive impression of the article.

- Use current terminology in your field of study.

- Stimulate reader interest.

A good research article title offers a brief explanation of the article before you delve into specifics. Before you get to a final title, you can start with a working title that gives you a main idea of what to focus on throughout your piece. Then you can come back to revise the title when you finish the article.

The Writing Process

As you write your research article, it can be useful to make a list of the questions that your article answers. For a broad topic, your article may answer 20 questions. If your subject is very narrow, you might come up with two or three questions. You can then use these questions to inform your research title.

Your article subject or hypothesis may also give you an idea for the final title, but so can your conclusion. As you write your research article from beginning to end, you draw several conclusions before answering your main idea or hypothesis. There's nothing wrong with using your conclusion as a title because your readers want to know how you derived the solution. A good research article title may actually be a spoiler, but that's a good thing. Once you have a draft title, you’ll need to take care of a few details to keep it interesting.

The Details

Take out any unnecessary words (such as ‘A Study of’, or ‘An Investigation of’) which don’t contribute any real meaning or value to your title. Avoid words or phrases that don't help your readers understand the context of your work, and ensure that your title gets to the real point of your article.

Your title needs to grab readers’ interest, so don't fear putting a little style into your article title. You can still avoid a boring title while getting to the point.

Don't make your title too short. The words "South American Politics" are clearly much too broad and don’t say what your research article entails. Rather, expand a bit to include more detail. Examine the title "South American Politics and Venezuelan Oil Clash with Brazil's Rain Forest Conservation Efforts”. The second title has more substance, keywords and enough meat to build interest.

Final Thoughts

Ask yourself a few questions that get to the heart of your article. What is the purpose of the research? What's the narrative tone of the article? What methods do you use to write the article? The purpose of your article provides the perfect lead-in to your conclusion. Meanwhile, your narrative tone depends on the point you make, such as delivering results of a paradigm-shifting study, breaking news of some major story or making a startling conclusion that no one expected.

A good article title represents the first impression people see of your work, so make sure you give your research the title it deserves!

How do you determine the title of your research article? Share your thoughts in the comments below .

Image Credit: Niklebedev/Shutterstock

Watch our Webinar to help you get published

Please enter your Email Address

Please enter valid email address

Please Enter your First Name

Please enter your Last Name

Please enter your Questions or Comments.

Please enter the Privacy

Please enter the Terms & Conditions

Your Guide to Publishing

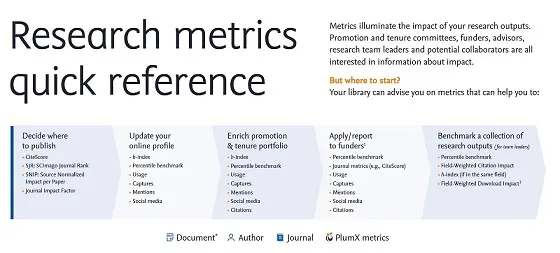

3 article-level metrics to understand your work’s impact

How to write a clinical case report

How to Write A Lay Summary for Your Research

Think. Check. Submit your way to the right journal

10 Ways to Reduce the Word Count of Your Research Paper

Writing for Publication- How Can a Structured Writing Retreat Help?

Infographic: 6 Steps for Writing a Literature Review

How to turn your dissertation into journal articles

How to Choose Effective SEO Keywords for Your Research Article | How to Write a Journal Article

Related articles.

Wiley supports you throughout the manuscript preparation process,

Get a quick understanding of the metrics that matter for your research, what they can show you, and where to find them.

Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Case Reports, Charles Young, discusses what makes a good case report.

Late with a review report? Find out how to handle the situation in this blog post from Andrew Moore, Editor-in-Chief of Bioessays.

Find out more about "Think.Check.Submit", a cross-industry initiative designed to support researchers on the road to publication.

Do you need some guidance on writing concisely? This presentation, originally published on Editage Insights, offers some quick tips to help you keep to your desired word count in academic writing.

Professor Rowena Murray looks back on a recent writing retreat and discusses how such retreats can help overcome writer's block.

This infographic sets out six simple steps to set you on your way to writing a successful and well thought out literature review.

Guidance for PhD students planning to turn dissertations into published journal articles.

Find 5 helpful tips about using keywords in your research article to help journals, and your article, be found more easily by researchers.

Helping authors to bypass article formatting headaches

Improving the author's experience with a simpler submission process and fewer formatting requirements. Release of the pilot program, free format submission.

Get Published: Your How-to Guide

Your how-to guide to get an in-depth understanding of the publishing journey.

FOR INDIVIDUALS

FOR INSTITUTIONS & BUSINESSES

WILEY NETWORK

ABOUT WILEY

Corporate Responsibility

Corporate Governance

Leadership Team

Cookie Preferences

Copyright @ 2000-2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., or related companies. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Rights & Permissions

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

Getting the title right

The title is the first thing you write. It is the moment you decide what is the purpose, focus and message of your article.

The title is also the first thing we will see of your published article. Whether we decide to click and read the abstract, or download the full article depends – at least, partly - on this first impression.

In this blogpost, I share some thoughts on what makes a good title, and how to come up with one. Even if you can´t find a great title for your article, what you can definitely do is avoid a bad one. I start with tips on what to avoid, proceed with properties and examples of good titles and finish with an illustration of how to get a decent title for a paper.

Five big ‘No’s.

A good title should be informative, argumentative and intriguing. And that’s all - any extra words that do not inform us or intrigue us about the argument, question, hypothesis or contribution of your article are redundant.

While it is difficult to come up with strong titles, you can start by avoiding bad ones!

Never do the following (disclosure - I’ve done all five of them):

Don't tell us in the title what is it that you are doing (‘a study of’, ‘lessons from’, ‘insights on’, ‘the case of’, ‘a comparison of’, ‘exploring’, ‘investigating’, ‘assessing’, ‘evaluating’, ‘measuring’). We know that this is a research paper. Go ahead and tell us what you found, not what you did.

Do not add dead words or words that are too general, such as: ‘beyond’, ‘from … to …’, ‘towards a’.

Avoid clichés and platitudes (‘exploring the contradictions of’, ‘integrating the’, ‘revealing the complexity of’). We know that research objects are complex (we wouldn’t study them if they were not), that causal relations in the real world are contradictory, or that integrating is better than separating.

Don´t tell us the method you are using or the approach you are following (‘a survey of’, ‘an econometric panel data analysis of’, ‘a case study of’, ‘an interdisciplinary perspective’). Exception: do it if the innovation of your paper is the method itself - but then tell us what your innovation is, not the name of your method.

Don’t try too hard to be witty. I’ve seen one too many papers that are ‘a tale of two’ .. islands, rivers, case-studies, ethnographies or surveys. I am sure there are also papers that are ‘gone with the wind’, or worst, ‘gone with the sea’.

Ashamed of past sins

Consider this title of an early paper of mine. “The EU water framework directive: measures and implications” .

Terrible. Boring as hell. I don’t want to read this paper and I am the one who wrote it.

What is wrong with this title?

First, it does not inform the reader about the purpose of my research or my argument. The reader only learns that I am analysing a legislative piece called the Water Framework Directive.

Second, ‘measures’ and ‘implications’ are descriptive, redundant terms. I am analysing a legislation, so of course I will describe its measures and talk about its implications.

The reader does not learn what is interesting or new about my analysis – no hint of what I found or what I will argue. I do not intrigue you to read the paper (unless you are a serious water nerd).

The three elements of a good title

What makes a great title?

Let me repeat.

A good title is informative: the core variables, phenomena or concepts you are contributing to, are there. The purpose of your paper is clear.

A better title is also argumentative: your (hypo)thesis, core finding, or politically-relevant conclusion is there. Ideally, this may include the process that connects your core variables, or the empirical pattern you demonstrate for your phenomenon.

A great title is also intriguing (without being cheesy): it attracts the attention of the reader, it promises something interesting and a new argument or explanation that the reader has not encountered before.

Most of us can write good titles. Titles that inform about the research we did (e.g. my “Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts, and valuation languages” ). The challenge is to go the extra mile and write great titles – titles that let the reader know not only what you researched, but also what you found. Titles that intrigue the reader to read your paper.

Learn from the champs

Consider two of the most cited titles in environmental studies.

‘ Limits to growth ’. It can´t get better than that. In just three words, the title informs you what this work is about: growth and its limits. The thesis, novelty and contribution are clear: unlike what others claim, this piece will argue that there are limits to growth – unlike others studying the causes of growth, this work studies the limits to growth. And this makes it intriguing.

Or Garett Hardin’s four-worded ‘tragedy of the commons’ . By reading the title you know what it is about: the commons. You also get the process, or hypothesis, Hardin is going to demonstrate and explain – the collapse of the commons.

The argument is intriguing: commons end up in tragedy. Written at the height of the Cold War, Hardin’s paper had an underlying political message: commons (shorthand for communism) end up in tragedy and there is a scientific reason why this is so. Like or dislike his conclusion, you are curious to read his paper and you want to engage with the argument, to support it or refute it.

My own In defence of degrowth tries something similar. It is short. It is politically provocative. And it is informative: the reader knows this paper is going to be about growth and degrowth.

But it lacks something that the limits or tragedy titles have: they make an argument. They have a thesis. My title does not say why or how I defend degrowth. (I could add a subtitle to capture this, but then some of the intrigue would be lost – see further on about subtitles and title length).

This is fine. We can´t be perfect. Rules can be broken. If your title is informative and intriguing enough, I think you can excuse yourself if you cannot capture also the thesis within the title.

Create some suspense with a question

Good research papers have good research questions. And good questions can be effective titles. Question titles lack an argument, but they intrigue with suspense.

Consider Daron Acemoglu’s and James Robinson’s ‘Why nations fail’ . You sure want to know why nations fail!

The book deals with the study of so-called ‘state failure’ – corruption and the collapse of government institutions. Instead of using this academic terminology, it uses simple language that speaks to everyone, while hinting to academics what it is about.

Another good question-title my ex-classmate Nathan McClintock came up with is ‘Why farm the city?’

I’ve seen scores of recent articles on urban agriculture (or urban gardening). I would never read one called ‘Beyond existing explanations of urban agriculture: lessons and contradictions’. But I am intrigued to learn why so many people suddenly farm in cities.

Often a subtitle follows a main, shorter title. ´Why nations fail´ for example, is followed by ‘The origins of power, prosperity and poverty´. ‘Why farm the city’ is followed by the more esoteric ‘Theorizing urban agriculture through the lens of metabolic rift’.

A subtitle explains or provides context to a shorter main title, it sets the place and time under study or the method used, and adds substance if your main title is a catchy visual cue, verbal quote or open question.

If you can avoid a subtitle, and your title is powerful enough on its own, I would say avoid it. Hardin did. Adding the place, time or method of your research weakens the generality of your claim – the reader will find this information in the abstract or the paper anyway. Darwin did not have to explain that his study of the origin of species covered millions of years and was based on specimens collected in England and the Galapagos.

Too short or too long?

One reason I am sceptical of subtitles is because very long headings tend to be confusing. As a rule of thumb, a title, including the subtitle, should be between 5 and 15 words.

I am personally fan of ‘short is beautiful’. If you can say it in three or four words, go for it!

Why nations fail? Why farm the city? The tragedy of the commons. The origin of species. You don’t need to say more than that.

Fair enough: you may feel you are not Darwin yet. A longer title with many dead words diminishes your claim to contribution and makes you feel safer. But time to get out of your comfort zone and stake the relevance of your research. If it is not relevant, why did you do it? And why do you want us to read it?

Lively titles

A common title structure used in the social sciences is “Lively cue: informative title”.

The lively cue takes the form of a visual cue, a metaphor, a pun, a literary reference or a quote from something someone said.

As I wrote, if you have to try hard to be witty, then don’t. Do it only if the cue comes naturally to you and only if it is your thesis.

Consider Robert Putnam’s ‘Bowling alone: America's declining social capital’ .

The thesis, and core finding of the book - that social bonds are weakening in the U.S. - is in the title for you to see: a person bowling alone. The subtitle informs you about the phenomenon studied, ‘social capital’ - and the process that is demonstrated empirically: the ‘decline’ of social capital. This is the perfect use of the cue: it really drives home the message of what this book is about, with a visual metaphor that speaks to all of us. The subtitle explains and asserts scientific credibility: make no mistake this is not a book about bowling.

Consider instead the title I chose with my friends Christos Zografos and Erik Gomez for our paper ‘To value or not to value? That is not the question’ .

The paper deals with the monetary valuation of nature: should we try to calculate the worth of a river? Our Shakespearean hint points to the quasi-existential dimension of this dilemma among ecological economists, the audience of this particular article. ‘That is not the question’ summarises our conclusion: the terms of the debate are wrong.

Looking back at it, I find our title somewhat pompous. The rest of the article is an esoteric debate on methods of monetary valuation with arcane academic language. The comparison to a Shakespearean drama makes us good candidates to be covered by the Onion .

My advice: use wit with caution and only if you are 100% sure that you can pull it off. Like an airplane cockpit, journal articles are not the place to be funny - titles even less so. Be aware of the risk when you use literary or other references. You might seem to be exaggerating the importance of your own work (we are the Shakespeares of ecological economics) – not a good idea, more so if you are a starting researcher.

Same principles apply to quotes from interviews. Don’t do it unless the quote is your thesis. Consider a title like “‘Let them die alone’: homelessness and social exclusion in downtown New York” (I imagined this).

‘Let them die alone’ could be a phrase that an officer, businessman or an angry neighbour told you the researcher. If the core thesis of your article is that there is an intentional abandonment of homeless people, and as a result they die, then this quotation is impactful.

If however your article is about something different, say increasing numbers of homelessness and unfair housing policies, or if you touch only peripherally on questions of intentional neglect, then the phrase is just sensational and distractive.

If you end up using a quote, make sure that it is grammatically correct, and that its meaning is crystal clear to everyone. Using quotes in the title is risky if you are not a native speaker. Many of my students are not (I am not either). Translating quotes from interviews they took in Spanish or Greek often times do not make sense in English.

Let’s do this!

You know what your article is going to be about. It's time to baptise it! I have created a workbook with a three step process to help you create better titles. Click on the image below to access the workbook.

If you tried any of this and it worked or didn't work let me know in the comments below. And if you have other tips to share, please let us know!

Written by Giorgos Kallis

Giorgos Kallis is an ICREA professor of environmental science at ICTA in Barcelona. Giorgos has degrees in Chemistry, Economics, Environmental Engineering and Environmental Policy and Planning. Before coming to Barcelona, he was a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of California at Berkeley.

- October 2017

- January 2018

- February 2018

- September 2018

- October 2018

- November 2018

- February 2019

- September 2019

Contribute to the blog

Are you interested in submitting a guest post on the site? Learn more about what we are looking for and next steps by reading our contributor’s guide .

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry.

| ORCID | |

| First Name | |

| Last Name | |

| Country | |

| Organisation | |

| City | |

| State/Region | |

| Role Title |

Download history

Article titles: the do's and don'ts.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 25 April, 2017

- Academic Writing Skills

Article Titles: The Do's and Don’ts

Selecting a good title for this article seemed much more important than usual so we hesitated for quite some time to find one that might set a good example. If you have any feedback, please see links below!

So, how did we eventually decide on this heading?

Choosing a title – ours as an example

Firstly, we wrote down the topic: article titles.

Next, we thought about the purpose of the article: explaining what to do and what not to do when selecting an article title.

Finally, we used statistics from previous studies to format the title with a colon.

Charlesworth Author Services published an article last year about the importance of selecting a good title for your research paper, and it is such an important topic that we decided to publish another one to discuss some recent research on the matter. To see our previous article, please visit http://cwauthors.com/article/ChoosingTitleAcademicResearchPaper .

It goes without saying that the title is the first thing that readers will see: journals will use it to judge whether the article is likely to be a viable submission and researchers will use it to judge whether the article will be useful to read. Recently, however, studies have confirmed quite how important titles really are.

Findings from Research Trends

Over the course of five years (2006–2010), Research Trends conducted a study on the impact of titles on the success of research articles. [1]

It was found that the length of the title did not correlate entirely to the number of citations, but that “papers with titles between 31 and 40 characters were cited the most”. [2]

Interestingly, results of the study also showed that “titles containing a comma or colon were cited more” than those containing a question mark. [3] By contrast, of the articles included in the study, the top 10 most cited contained no punctuation at all.

Findings from Research Excellence Framework

A more recent study based on 150,000 papers submitted to the Research Excellence Framework database in 2014 corroborated many of the earlier findings. For example, “citations increased with titles that used colons, and declined with the use of question marks”. [4]

The report, published in Scientometrics, was also examined in Nature Index. Analyses suggest that title length is affected by subject area, and so longer titles are more acceptable in certain fields, namely Public Health and Clinical Medicine, while in other disciplines there are, on average, fewer characters in a title: Philosophy, Economics. [5]

Both the above studies found that humorous titles were cited less, so there is no need to agonize over a pun to attract readers.

Expert advice

According to BioScience Writers, some journals may only consider the title and abstract when selecting articles for publication. So, to create a positive impression titles should contain the following three elements: [6]

1. Key words and key phrases: Describe the topic of your article so that it can be found when searching by

subject.

2. Emphasis: Clarify the most important features of your article.

3. Impact: Draw readers’ attention to your article by explaining how your results or methods are novel or

innovative.

Similarly, Columbia University advises researchers to be specific in their titles, and claims that outlining the results is sometimes more effective: “Students who smoke get lower grades”. [7]

Summary points on choosing a title:

· Try to create a clear and concise title

· Reflect on title length of articles which are highly cited in your field of research

· Include novel or innovative results or methods

· If your title requires punctuation to aid reader understanding, consider using a colon or commas

· Avoid using question marks and semi-colons

· Avoid humor

Ultimately, however, as all cited resources mention, a good title cannot compensate for a poor paper! What it can do, though, is help to promote all your hard work by promoting the content of your paper and drawing in readers.

Please see the following websites for more information about the studies and for further advice on writing article titles:

· http://cwauthors.com/article/ChoosingTitleAcademicResearchPaper

· https://www.researchtrends.com/issue24-september-2011/heading-for-success-or-how-not-to-title-your-paper/

· http://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-research-paper-titles-can-make-or-break

· http://www.columbia.edu/cu/biology/ug/research/paper.html

Additional help and support

Any questions? Charlesworth Author Services can advise you on your editing needs. Please contact us at [email protected] or [email protected] .

[1] https://www.researchtrends.com/issue24-september-2011/heading-for-success-or-how-not-to-title-your-paper/ Accessed 10 April 2017

[2] https://www.researchtrends.com/issue24-september-2011/heading-for-success-or-how-not-to-title-your-paper/ Accessed 10 April 2017

[3] https://www.researchtrends.com/issue24-september-2011/heading-for-success-or-how-not-to-title-your-paper/ Accessed 10 April 2017

[4] http://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-research-paper-titles-can-make-or-break Accessed 10 April 2017

[5] http://www.natureindex.com/news-blog/how-research-paper-titles-can-make-or-break Accessed 10 April 2017

[6] http://www.biosciencewriters.com/Writing-Strong-Titles-for-Research-Manuscripts.aspx Accessed 10 April 2017

[7] http://www.columbia.edu/cu/biology/ug/research/paper.html Accessed 10 April 2017

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

Choosing a title for your academic research paper

Charlesworth Author Services 03/08/2017 00:00:00

Getting the title of your research article right

Charlesworth Author Services 17/08/2020 00:00:00

Writing a strong Methods section

Charlesworth Author Services 12/03/2021 00:00:00

How to write an Introduction to an academic article

Recommended webinars.

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 6: Choose great titles and write strong abstracts

Charlesworth Author Services 05/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 8: Write a strong methods section

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 9:Write a strong results and discussion section

Writing a compelling results and discussion section

How to respond to negative, unexpected data and results

Charlesworth Author Services 14/12/2020 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 7: Write a strong theoretical framework section

Bitesize Webinar: How to write and structure your academic article for publication: Module 10: Enhance your paper with visuals

- Peer-review Process

- Conflicts of Interest

- Open Access Policy

- Guidelines for Editors

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Publishing Ethics

- Corrections and Retractions

- Plagiarism Policy

- Misconduct Allegation Policy

- Subscription

- Author Guidelines

- Technology Journals

- Environment Science & Technology

- Management Journals

- MCA Journals

- Medical Journals

- Nursing Journals

- Pharmacy Journals

- Science Journals

- Social Science Journals

- Society Journals

How to Create the Best Title for Your Article

The title is the first part of an article to be published in journals of scientific journal publishers ; however, it is better to be written at the end when you are done with writing your article. An article may need several months of research and, meanwhile, you may come up with new ideas that may change the direction of your study. Hence, it is suggested to note down all your ideas as a draft and when your article has taken a final shape, think of drafting the title.

The title indicates the main idea of the article. It is the part of the article that is read first; it catches the eye and arouses interest in the article.

Types of titles

You may choose any of the three types of title for your journal article: declarative, descriptive, and interrogative.

- A declarative title presents a summary of key findings and results. This type of title provides the most insight into the contents of the paper and is commonly used for research articles.

- A descriptive title is the most common type of title and describes the topic of study but excludes results and conclusion.

- An interrogative title presents the topic of study as a question. It is generally used in review articles.

Characteristics of an effective title

To create an effective title, you should:

- write the main topic and subtopic separated by a colon (title: subtitle).

- indicate accurately the topic and scope of the study.

- use 10 to 20 words; though the length of the title may depend on your subject of interest (in peer-reviewed and open-access medical journal , article titles are longer than in Mathematics journals).

- use common words and current nomenclature in your field of study.

- Try to add keywords so that your readers may search easily.

- use the colon if you would like to use a subtitle (subtitle provides additional information).

- spell out abbreviations in the title.

- use simple and common words and avoid jargon.

- scientific names of organisms should be italicized.

- spell out numbers.

- use a comma, if required, and parenthesis but avoid semicolon.

Finally, the title and abstract should match the rest of the article. Also, check that you have adhered to the guidelines of the journal to which you are going to submit your article.

Keep it short

Too long a title may create an aversion in the reader and some readers may even avoid opening the article. The title should include as much information about the article as possible in the fewest words.

I certainly thank you for writing this article well, hopefully it will become a reference in journals or other scientific writings and can help many people. thanks.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Titles in research articles

Ken Hyland , Hang (Joanna) Zou

- School of Education & Lifelong Learning

- Language in Education

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Article number | 101094 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 56 |

| Early online date | 4 Feb 2022 |

| DOIs | |

| Publication status | Published - Mar 2022 |

- Academic writing

- Corpus analysis

- Disciplinary differences

- Research articles

Access to Document

- 10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101094 Licence: CC BY

- Hyland_Zou_2022_JoEfAP Final published version, 887 KB Licence: CC BY

Other files and links

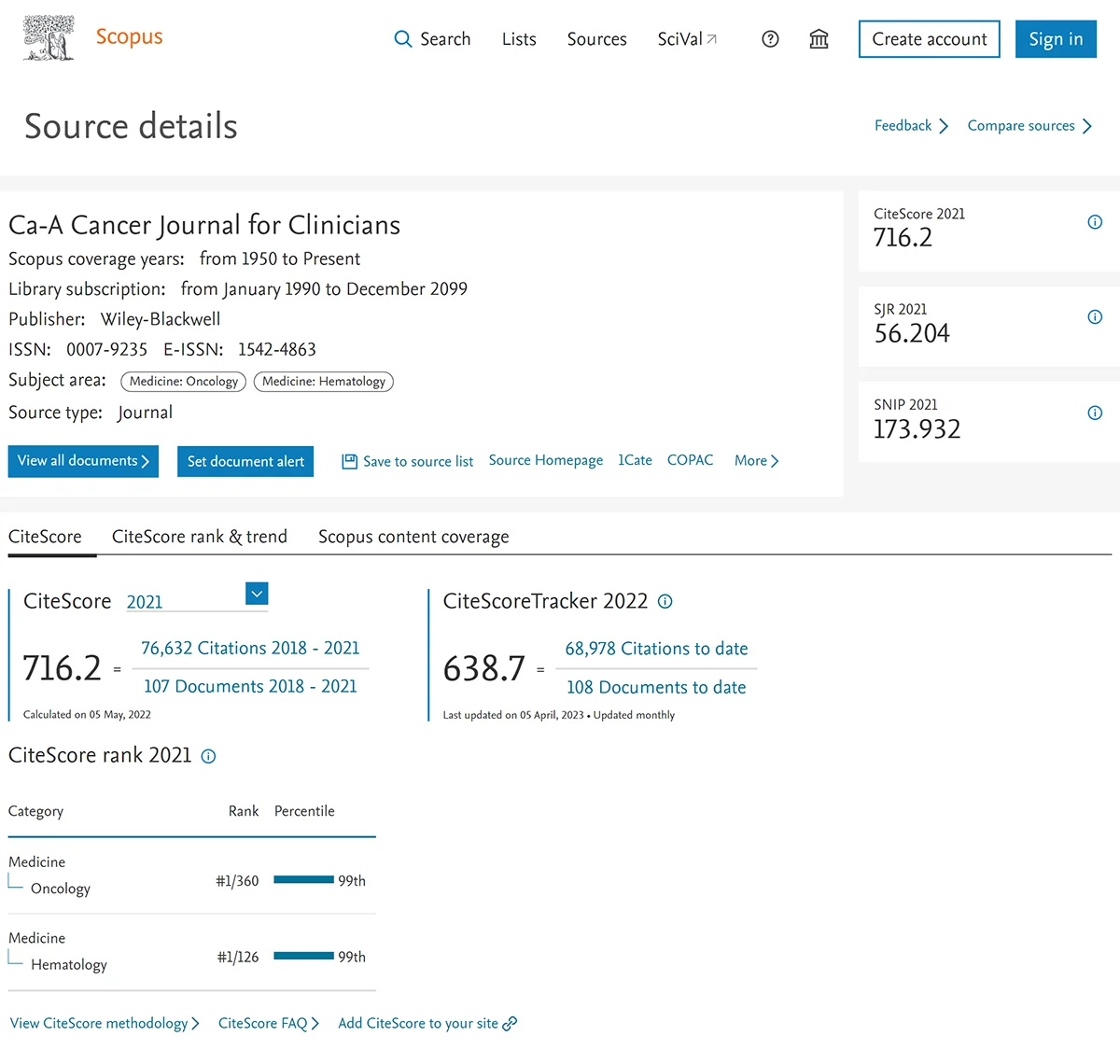

- Link to publication in Scopus

Titles in research articles. / Hyland, Ken ; Zou, Hang (Joanna) .

T1 - Titles in research articles

AU - Hyland, Ken

AU - Zou, Hang (Joanna)

PY - 2022/3

Y1 - 2022/3

N2 - Titles are a key part of every academic genre and are particularly important in research papers. Today, online searches are overwhelmingly based on articles rather than journals which means that writers must, more than ever, make their titles both informative and appealing to attract readers who may go on to read, cite and make use of their research. In this paper we explore the key features of 5070 titles in the leading journals of six disciplines in the human and physical sciences to identify their typical structural patterns and content foci. In addition to proposing a model of title patterns, we show there are major disciplinary differences which can be traced to different characteristics of the fields and of the topics of the articles themselves. Our findings have important implications for EAP and ERPP teachers working with early career academic writers.

AB - Titles are a key part of every academic genre and are particularly important in research papers. Today, online searches are overwhelmingly based on articles rather than journals which means that writers must, more than ever, make their titles both informative and appealing to attract readers who may go on to read, cite and make use of their research. In this paper we explore the key features of 5070 titles in the leading journals of six disciplines in the human and physical sciences to identify their typical structural patterns and content foci. In addition to proposing a model of title patterns, we show there are major disciplinary differences which can be traced to different characteristics of the fields and of the topics of the articles themselves. Our findings have important implications for EAP and ERPP teachers working with early career academic writers.

KW - Academic writing

KW - Corpus analysis

KW - Disciplinary differences

KW - Research articles

KW - Titles

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85124107194&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101094

DO - 10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101094

M3 - Article

JO - Journal of English for Academic Purposes

JF - Journal of English for Academic Purposes

SN - 1475-1585

M1 - 101094

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Saudi J Anaesth

- v.13(Suppl 1); 2019 Apr

Writing the title and abstract for a research paper: Being concise, precise, and meticulous is the key

Milind s. tullu.

Department of Pediatrics, Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

This article deals with formulating a suitable title and an appropriate abstract for an original research paper. The “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” of a research article, and hence they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, and meticulously. Often both of these are drafted after the full manuscript is ready. Most readers read only the title and the abstract of a research paper and very few will go on to read the full paper. The title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper and should be pleasant to read. The “title” should be descriptive, direct, accurate, appropriate, interesting, concise, precise, unique, and should not be misleading. The “abstract” needs to be simple, specific, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, stand-alone, complete, scholarly, (preferably) structured, and should not be misrepresentative. The abstract should be consistent with the main text of the paper, especially after a revision is made to the paper and should include the key message prominently. It is very important to include the most important words and terms (the “keywords”) in the title and the abstract for appropriate indexing purpose and for retrieval from the search engines and scientific databases. Such keywords should be listed after the abstract. One must adhere to the instructions laid down by the target journal with regard to the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.

Introduction

This article deals with drafting a suitable “title” and an appropriate “abstract” for an original research paper. Because the “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” or the “face” of a research article, they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, meticulously, and consume time and energy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Often, these are drafted after the complete manuscript draft is ready.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] Most readers will read only the title and the abstract of a published research paper, and very few “interested ones” (especially, if the paper is of use to them) will go on to read the full paper.[ 1 , 2 ] One must remember to adhere to the instructions laid down by the “target journal” (the journal for which the author is writing) regarding the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.[ 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 12 ] Both the title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper – for editors (to decide whether to process the paper for further review), for reviewers (to get an initial impression of the paper), and for the readers (as these may be the only parts of the paper available freely and hence, read widely).[ 4 , 8 , 12 ] It may be worth for the novice author to browse through titles and abstracts of several prominent journals (and their target journal as well) to learn more about the wording and styles of the titles and abstracts, as well as the aims and scope of the particular journal.[ 5 , 7 , 9 , 13 ]

The details of the title are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the title

When a reader browses through the table of contents of a journal issue (hard copy or on website), the title is the “ first detail” or “face” of the paper that is read.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 13 ] Hence, it needs to be simple, direct, accurate, appropriate, specific, functional, interesting, attractive/appealing, concise/brief, precise/focused, unambiguous, memorable, captivating, informative (enough to encourage the reader to read further), unique, catchy, and it should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] It should have “just enough details” to arouse the interest and curiosity of the reader so that the reader then goes ahead with studying the abstract and then (if still interested) the full paper.[ 1 , 2 , 4 , 13 ] Journal websites, electronic databases, and search engines use the words in the title and abstract (the “keywords”) to retrieve a particular paper during a search; hence, the importance of these words in accessing the paper by the readers has been emphasized.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 , 14 ] Such important words (or keywords) should be arranged in appropriate order of importance as per the context of the paper and should be placed at the beginning of the title (rather than the later part of the title, as some search engines like Google may just display only the first six to seven words of the title).[ 3 , 5 , 12 ] Whimsical, amusing, or clever titles, though initially appealing, may be missed or misread by the busy reader and very short titles may miss the essential scientific words (the “keywords”) used by the indexing agencies to catch and categorize the paper.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 9 ] Also, amusing or hilarious titles may be taken less seriously by the readers and may be cited less often.[ 4 , 15 ] An excessively long or complicated title may put off the readers.[ 3 , 9 ] It may be a good idea to draft the title after the main body of the text and the abstract are drafted.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]

Types of titles

Titles can be descriptive, declarative, or interrogative. They can also be classified as nominal, compound, or full-sentence titles.

Descriptive or neutral title

This has the essential elements of the research theme, that is, the patients/subjects, design, interventions, comparisons/control, and outcome, but does not reveal the main result or the conclusion.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ] Such a title allows the reader to interpret the findings of the research paper in an impartial manner and with an open mind.[ 3 ] These titles also give complete information about the contents of the article, have several keywords (thus increasing the visibility of the article in search engines), and have increased chances of being read and (then) being cited as well.[ 4 ] Hence, such descriptive titles giving a glimpse of the paper are generally preferred.[ 4 , 16 ]

Declarative title

This title states the main finding of the study in the title itself; it reduces the curiosity of the reader, may point toward a bias on the part of the author, and hence is best avoided.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ]

Interrogative title

This is the one which has a query or the research question in the title.[ 3 , 4 , 16 ] Though a query in the title has the ability to sensationalize the topic, and has more downloads (but less citations), it can be distracting to the reader and is again best avoided for a research article (but can, at times, be used for a review article).[ 3 , 6 , 16 , 17 ]

From a sentence construct point of view, titles may be nominal (capturing only the main theme of the study), compound (with subtitles to provide additional relevant information such as context, design, location/country, temporal aspect, sample size, importance, and a provocative or a literary; for example, see the title of this review), or full-sentence titles (which are longer and indicate an added degree of certainty of the results).[ 4 , 6 , 9 , 16 ] Any of these constructs may be used depending on the type of article, the key message, and the author's preference or judgement.[ 4 ]

Drafting a suitable title

A stepwise process can be followed to draft the appropriate title. The author should describe the paper in about three sentences, avoiding the results and ensuring that these sentences contain important scientific words/keywords that describe the main contents and subject of the paper.[ 1 , 4 , 6 , 12 ] Then the author should join the sentences to form a single sentence, shorten the length (by removing redundant words or adjectives or phrases), and finally edit the title (thus drafted) to make it more accurate, concise (about 10–15 words), and precise.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 ] Some journals require that the study design be included in the title, and this may be placed (using a colon) after the primary title.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 14 ] The title should try to incorporate the Patients, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcome (PICO).[ 3 ] The place of the study may be included in the title (if absolutely necessary), that is, if the patient characteristics (such as study population, socioeconomic conditions, or cultural practices) are expected to vary as per the country (or the place of the study) and have a bearing on the possible outcomes.[ 3 , 6 ] Lengthy titles can be boring and appear unfocused, whereas very short titles may not be representative of the contents of the article; hence, optimum length is required to ensure that the title explains the main theme and content of the manuscript.[ 4 , 5 , 9 ] Abbreviations (except the standard or commonly interpreted ones such as HIV, AIDS, DNA, RNA, CDC, FDA, ECG, and EEG) or acronyms should be avoided in the title, as a reader not familiar with them may skip such an article and nonstandard abbreviations may create problems in indexing the article.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] Also, too much of technical jargon or chemical formulas in the title may confuse the readers and the article may be skipped by them.[ 4 , 9 ] Numerical values of various parameters (stating study period or sample size) should also be avoided in the titles (unless deemed extremely essential).[ 4 ] It may be worthwhile to take an opinion from a impartial colleague before finalizing the title.[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] Thus, multiple factors (which are, at times, a bit conflicting or contrasting) need to be considered while formulating a title, and hence this should not be done in a hurry.[ 4 , 6 ] Many journals ask the authors to draft a “short title” or “running head” or “running title” for printing in the header or footer of the printed paper.[ 3 , 12 ] This is an abridged version of the main title of up to 40–50 characters, may have standard abbreviations, and helps the reader to navigate through the paper.[ 3 , 12 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good title

Table 1 gives a checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 ] Table 2 presents some of the titles used by the author of this article in his earlier research papers, and the appropriateness of the titles has been commented upon. As an individual exercise, the reader may try to improvise upon the titles (further) after reading the corresponding abstract and full paper.

Checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper

| The title needs to be simple and direct |

| It should be interesting and informative |

| It should be specific, accurate, and functional (with essential scientific “keywords” for indexing) |

| It should be concise, precise, and should include the main theme of the paper |

| It should not be misleading or misrepresentative |

| It should not be too long or too short (or cryptic) |

| It should avoid whimsical or amusing words |

| It should avoid nonstandard abbreviations and unnecessary acronyms (or technical jargon) |

| Title should be SPICED, that is, it should include Setting, Population, Intervention, Condition, End-point, and Design |

| Place of the study and sample size should be mentioned only if it adds to the scientific value of the title |

| Important terms/keywords should be placed in the beginning of the title |

| Descriptive titles are preferred to declarative or interrogative titles |

| Authors should adhere to the word count and other instructions as specified by the target journal |

Some titles used by author of this article in his earlier publications and remark/comment on their appropriateness

| Title | Comment/remark on the contents of the title |

|---|---|

| Comparison of Pediatric Risk of Mortality III, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2, and Pediatric Index of Mortality 3 Scores in Predicting Mortality in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | Long title (28 words) capturing the main theme; site of study is mentioned |

| A Prospective Antibacterial Utilization Study in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit of a Tertiary Referral Center | Optimum number of words capturing the main theme; site of study is mentioned |

| Study of Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | The words “study of” can be deleted |

| Clinical Profile, Co-Morbidities & Health Related Quality of Life in Pediatric Patients with Allergic Rhinitis & Asthma | Optimum number of words; population and intervention mentioned |

| Benzathine Penicillin Prophylaxis in Children with Rheumatic Fever (RF)/Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD): A Study of Compliance | Subtitle used to convey the main focus of the paper. It may be preferable to use the important word “compliance” in the beginning of the title rather than at the end. Abbreviations RF and RHD can be deleted as corresponding full forms have already been mentioned in the title itself |

| Performance of PRISM (Pediatric Risk of Mortality) Score and PIM (Pediatric Index of Mortality) Score in a Tertiary Care Pediatric ICU | Abbreviations used. “ICU” may be allowed as it is a commonly used abbreviation. Abbreviations PRISM and PIM can be deleted as corresponding full forms are already used in the title itself |

| Awareness of Health Care Workers Regarding Prophylaxis for Prevention of Transmission of Blood-Borne Viral Infections in Occupational Exposures | Slightly long title (18 words); theme well-captured |

| Isolated Infective Endocarditis of the Pulmonary Valve: An Autopsy Analysis of Nine Cases | Subtitle used to convey additional details like “autopsy” (i.e., postmortem analysis) and “nine” (i.e., number of cases) |

| Atresia of the Common Pulmonary Vein - A Rare Congenital Anomaly | Subtitle used to convey importance of the paper/rarity of the condition |

| Psychological Consequences in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Survivors: The Neglected Outcome | Subtitle used to convey importance of the paper and to make the title more interesting |

| Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: Clinical Profile of 550 patients in India | Number of cases (550) emphasized because it is a large series; country (India) is mentioned in the title - will the clinical profile of patients with rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease vary from country to country? May be yes, as the clinical features depend on the socioeconomic and cultural background |

| Neurological Manifestations of HIV Infection | Short title; abbreviation “HIV” may be allowed as it is a commonly used abbreviation |

| Krabbe Disease - Clinical Profile | Very short title (only four words) - may miss out on the essential keywords required for indexing |

| Experience of Pediatric Tetanus Cases from Mumbai | City mentioned (Mumbai) in the title - one needs to think whether it is required in the title |

The Abstract

The details of the abstract are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the abstract

The abstract is a summary or synopsis of the full research paper and also needs to have similar characteristics like the title. It needs to be simple, direct, specific, functional, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, self-sufficient, complete, comprehensive, scholarly, balanced, and should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 ] Writing an abstract is to extract and summarize (AB – absolutely, STR – straightforward, ACT – actual data presentation and interpretation).[ 17 ] The title and abstracts are the only sections of the research paper that are often freely available to the readers on the journal websites, search engines, and in many abstracting agencies/databases, whereas the full paper may attract a payment per view or a fee for downloading the pdf copy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 ] The abstract is an independent and stand-alone (that is, well understood without reading the full paper) section of the manuscript and is used by the editor to decide the fate of the article and to choose appropriate reviewers.[ 2 , 7 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] Even the reviewers are initially supplied only with the title and the abstract before they agree to review the full manuscript.[ 7 , 13 ] This is the second most commonly read part of the manuscript, and therefore it should reflect the contents of the main text of the paper accurately and thus act as a “real trailer” of the full article.[ 2 , 7 , 11 ] The readers will go through the full paper only if they find the abstract interesting and relevant to their practice; else they may skip the paper if the abstract is unimpressive.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] The abstract needs to highlight the selling point of the manuscript and succeed in luring the reader to read the complete paper.[ 3 , 7 ] The title and the abstract should be constructed using keywords (key terms/important words) from all the sections of the main text.[ 12 ] Abstracts are also used for submitting research papers to a conference for consideration for presentation (as oral paper or poster).[ 9 , 13 , 17 ] Grammatical and typographic errors reflect poorly on the quality of the abstract, may indicate carelessness/casual attitude on part of the author, and hence should be avoided at all times.[ 9 ]

Types of abstracts

The abstracts can be structured or unstructured. They can also be classified as descriptive or informative abstracts.

Structured and unstructured abstracts

Structured abstracts are followed by most journals, are more informative, and include specific subheadings/subsections under which the abstract needs to be composed.[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] These subheadings usually include context/background, objectives, design, setting, participants, interventions, main outcome measures, results, and conclusions.[ 1 ] Some journals stick to the standard IMRAD format for the structure of the abstracts, and the subheadings would include Introduction/Background, Methods, Results, And (instead of Discussion) the Conclusion/s.[ 1 , 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] Structured abstracts are more elaborate, informative, easy to read, recall, and peer-review, and hence are preferred; however, they consume more space and can have same limitations as an unstructured abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 18 ] The structured abstracts are (possibly) better understood by the reviewers and readers. Anyway, the choice of the type of the abstract and the subheadings of a structured abstract depend on the particular journal style and is not left to the author's wish.[ 7 , 10 , 12 ] Separate subheadings may be necessary for reporting meta-analysis, educational research, quality improvement work, review, or case study.[ 1 ] Clinical trial abstracts need to include the essential items mentioned in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) guidelines.[ 7 , 9 , 14 , 19 ] Similar guidelines exist for various other types of studies, including observational studies and for studies of diagnostic accuracy.[ 20 , 21 ] A useful resource for the above guidelines is available at www.equator-network.org (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research). Unstructured (or non-structured) abstracts are free-flowing, do not have predefined subheadings, and are commonly used for papers that (usually) do not describe original research.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 10 ]

The four-point structured abstract: This has the following elements which need to be properly balanced with regard to the content/matter under each subheading:[ 9 ]

Background and/or Objectives: This states why the work was undertaken and is usually written in just a couple of sentences.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] The hypothesis/study question and the major objectives are also stated under this subheading.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ]

Methods: This subsection is the longest, states what was done, and gives essential details of the study design, setting, participants, blinding, sample size, sampling method, intervention/s, duration and follow-up, research instruments, main outcome measures, parameters evaluated, and how the outcomes were assessed or analyzed.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Results/Observations/Findings: This subheading states what was found, is longer, is difficult to draft, and needs to mention important details including the number of study participants, results of analysis (of primary and secondary objectives), and include actual data (numbers, mean, median, standard deviation, “P” values, 95% confidence intervals, effect sizes, relative risks, odds ratio, etc.).[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Conclusions: The take-home message (the “so what” of the paper) and other significant/important findings should be stated here, considering the interpretation of the research question/hypothesis and results put together (without overinterpreting the findings) and may also include the author's views on the implications of the study.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

The eight-point structured abstract: This has the following eight subheadings – Objectives, Study Design, Study Setting, Participants/Patients, Methods/Intervention, Outcome Measures, Results, and Conclusions.[ 3 , 9 , 18 ] The instructions to authors given by the particular journal state whether they use the four- or eight-point abstract or variants thereof.[ 3 , 14 ]

Descriptive and Informative abstracts

Descriptive abstracts are short (75–150 words), only portray what the paper contains without providing any more details; the reader has to read the full paper to know about its contents and are rarely used for original research papers.[ 7 , 10 ] These are used for case reports, reviews, opinions, and so on.[ 7 , 10 ] Informative abstracts (which may be structured or unstructured as described above) give a complete detailed summary of the article contents and truly reflect the actual research done.[ 7 , 10 ]

Drafting a suitable abstract

It is important to religiously stick to the instructions to authors (format, word limit, font size/style, and subheadings) provided by the journal for which the abstract and the paper are being written.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] Most journals allow 200–300 words for formulating the abstract and it is wise to restrict oneself to this word limit.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22 ] Though some authors prefer to draft the abstract initially, followed by the main text of the paper, it is recommended to draft the abstract in the end to maintain accuracy and conformity with the main text of the paper (thus maintaining an easy linkage/alignment with title, on one hand, and the introduction section of the main text, on the other hand).[ 2 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] The authors should check the subheadings (of the structured abstract) permitted by the target journal, use phrases rather than sentences to draft the content of the abstract, and avoid passive voice.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 12 ] Next, the authors need to get rid of redundant words and edit the abstract (extensively) to the correct word count permitted (every word in the abstract “counts”!).[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] It is important to ensure that the key message, focus, and novelty of the paper are not compromised; the rationale of the study and the basis of the conclusions are clear; and that the abstract is consistent with the main text of the paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ] This is especially important while submitting a revision of the paper (modified after addressing the reviewer's comments), as the changes made in the main (revised) text of the paper need to be reflected in the (revised) abstract as well.[ 2 , 10 , 12 , 14 , 22 ] Abbreviations should be avoided in an abstract, unless they are conventionally accepted or standard; references, tables, or figures should not be cited in the abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 ] It may be worthwhile not to rush with the abstract and to get an opinion by an impartial colleague on the content of the abstract; and if possible, the full paper (an “informal” peer-review).[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 17 ] Appropriate “Keywords” (three to ten words or phrases) should follow the abstract and should be preferably chosen from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) list of the U.S. National Library of Medicine ( https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/search ) and are used for indexing purposes.[ 2 , 3 , 11 , 12 ] These keywords need to be different from the words in the main title (the title words are automatically used for indexing the article) and can be variants of the terms/phrases used in the title, or words from the abstract and the main text.[ 3 , 12 ] The ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; http://www.icmje.org/ ) also recommends publishing the clinical trial registration number at the end of the abstract.[ 7 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good abstract

Table 3 gives a checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ]

Checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper

| The abstract should have simple language and phrases (rather than sentences) |

| It should be informative, cohesive, and adhering to the structure (subheadings) provided by the target journal. Structured abstracts are preferred over unstructured abstracts |

| It should be independent and stand-alone/complete |

| It should be concise, interesting, unbiased, honest, balanced, and precise |

| It should not be misleading or misrepresentative; it should be consistent with the main text of the paper (especially after a revision is made) |

| It should utilize the full word capacity allowed by the journal so that most of the actual scientific facts of the main paper are represented in the abstract |

| It should include the key message prominently |

| It should adhere to the style and the word count specified by the target journal (usually about 250 words) |

| It should avoid nonstandard abbreviations and (if possible) avoid a passive voice |

| Authors should list appropriate “keywords” below the abstract (keywords are used for indexing purpose) |

Concluding Remarks

This review article has given a detailed account of the importance and types of titles and abstracts. It has also attempted to give useful hints for drafting an appropriate title and a complete abstract for a research paper. It is hoped that this review will help the authors in their career in medical writing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr. Hemant Deshmukh - Dean, Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, for granting permission to publish this manuscript.

- Open access

- Published: 21 October 2014

Title and Abstract Screening and Evaluation in Systematic Reviews (TASER): a pilot randomised controlled trial of title and abstract screening by medical students

- Lauren Ng 1 ,

- Veronica Pitt 2 ,

- Kit Huckvale 3 ,

- Ornella Clavisi 2 ,

- Tari Turner 1 , 4 ,

- Russell Gruen 2 &

- Julian H Elliott 5 , 6