- Journal home

- About the journal

- J-STAGE home

- The Journal of Studies on Educ ...

- Volume 20 (2018-2019) Issue 2

- Article overview

Graduate School of Education, The University of Tokyo [Japan] Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [Japan]

Corresponding author

2019 Volume 20 Issue 2 Pages 27-39

- Published: 2019 Received: - Available on J-STAGE: May 08, 2021 Accepted: - Advance online publication: - Revised: -

(compatible with EndNote, Reference Manager, ProCite, RefWorks)

(compatible with BibDesk, LaTeX)

Homework can have both positive and negative effects on student learning. To overcome the negative effects and facilitate the positive ones, it is important for teachers to understand the underlying mechanisms of homework and how it relates to learning so that they can use the most effective methods of instruction and guidance. To provide a useful guide, this paper reviewed previous research studies and considered the roles of homework and effective instructional strategies from three psychological perspectives: behavioral, information-processing, and social constructivism. From a behavioral perspective, homework can be viewed as increasing opportunities for the repeated practice of knowledge and skills, whereas the information processing perspective places greater importance on the capacity of homework to promote deeper understanding and metacognition. Viewed from a social constructivist perspective, homework can promote the establishment of connections in the learning that occurs in school, at home, and in the wider community. Studies have shown that each of these roles of homework can contribute to the facilitation of meaningful learning and the support of students toward becoming self-initiated learners. However, there are some crucial challenges that remain in applying this knowledge to the actual school setting. This paper’s conclusion discusses possible directions for much-needed future research and suggests potential solutions.

- Add to favorites

- Additional info alert

- Citation alert

- Authentication alert

Register with J-STAGE for free!

Already have an account? Sign in here

Are homework purposes and student achievement reciprocally related? A longitudinal study

- Published: 09 September 2019

- Volume 40 , pages 4945–4956, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Meilu Sun 1 ,

- Jianxia Du 2 &

- Jianzhong Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0269-4590 3

1295 Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

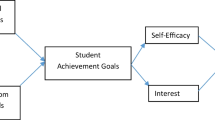

The current study examines reciprocal influences of homework purposes (approval-seeking, self-regulatory, and academic) and math achievement, using data from 1365 students in grade 8 at two measurement points. Results indicated there were positive reciprocal influences of (a) academic purpose and achievement, and (b) academic purpose and self-regulatory purpose. Results further revealed that prior achievement had a positive effect on later self-regulatory purpose. Meanwhile, prior approval-seeking purpose had a negative effect on later achievement. Taken together, the present study advance extant research, by differentiating three types of homework purposes using models of reciprocal influences, and by showing their respective relationships with math achievement over time.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Homework goal orientation, interest, and achievement: testing models of reciprocal effects

Math homework purpose scale for preadolescents: a psychometric evaluation

A multifactorial model of intrinsic / environmental motivators, personal traits and their combined influences on math performance in elementary school

Adachi, P., & Willoughby, T. (2015). Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12 , 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2014.963549 .

Article Google Scholar

Bempechat, J. (2019). The case for (quality) homework. Education Next, 19 (1).

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14 , 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834 .

Chen, C., & Stevenson, H. W. (1989). Homework: A cross-cultural examination. Child Development, 60 , 551–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130721 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9 , 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 .

Cheung, C. S.-S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2012). Why does parents’ involvement enhance children’s achievement? The role of parent-oriented motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 820–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027183 .

Cooper, H. (1989). Homework . White Plains: Longman.

Book Google Scholar

Cooper, M. L. (1994). Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor-model. Psychological Assessment, 6 , 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117 .

Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework: Common ground for administrators, teachers, and parents (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. J., Nye, B., & Greathouse, S. (1998). Relationships among attitudes about homework, amount of homework assigned and completed, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 , 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.1.70 .

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 , 1–62. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001001 .

Cooper, M. L., Kuntsche, E., Levitt, A., Barber, L., & Wolf, S. (2016). A motivational perspective on substance use: Review of theory and research. In K. J. Sher (Ed.), Oxford handbook of substance use disorders (pp. 375–421). New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Corno, L. (1996). Homework is a complicated thing. Educational Researcher, 25 (8), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X025008027 .

Corno, L. (2000). Looking at homework differently. Elementary School Journal, 100 , 529–548. https://doi.org/10.1086/499654 .

Corno, L., & Xu, J. (2004). Doing homework as the job of childhood. Theory Into Practice, 43 , 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4303_9 .

Costa-Giomi, E., Flowers, P. J., & Sasaki, W. (2005). Piano lessons of beginning students who persist or drop out: Teacher behavior, student behavior, and lesson progress. Journal of Research in Music Education, 53 , 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242940505300305 .

Coutts, P. M. (2004). Meanings of homework and implications for practice. Theory Into Practice, 43 , 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4303_3 .

Dai, D. Y. (2001). A comparison of gender differences in academic self-concept and motivation between high-ability and average Chinese adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 13 , 22–32. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2001-361 .

Desa, D. (2014). Evaluating measurement invariance of TALIS 2013 complex scales: Comparison between continuous and categorical multiple-group confirmatory factor analyses. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jz2kbbvlb7k-en .

Dettmers, S., Trautwein, U., Ludtke, O., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., & Pekrun, R. (2011). Students' emotions during homework in mathematics: Testing a theoretical model of antecedents and achievement outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36 , 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.001 .

Dowson, M., & McInerney, D. M. (2001). Psychological parameters of students’ social and work avoidance goals: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93 , 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.35 .

Dowson, M., & McInerney, D. M. (2003). What do students say about their motivational goals? Towards a more complex and dynamic perspective on student motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28 , 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-476X(02)00010-3 .

Du, J., Zhou, M., Xu, J., & Lei, S. S. (2016). African American female students in online collaborative learning activities: The role of identity, emotion, and peer support. Computers in Human Behavior, 63 , 948–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.021 .

Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic choice: Origins and changes. In J. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 87–134). San Francisco: Freeman.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents' achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 , 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003 .

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 , 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 .

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis . New York: Guilford Press.

Epstein, J. L., & Van Voorhis, F. L. (2001). More than minutes: Teachers’ roles in designing homework. Educational Psychologist, 36 , 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_4 .

Epstein, J., & Van Voorhis, F. (2012). The changing debate: From assigning homework to designing homework. In S. Suggate & E. Reese (Eds.), Contemporary debates in child development and education (pp. 263–273). London: Routledge.

Fan, H., Xu, J., Cai, Z., He, J., & Fan, X. (2017). Homework and students' achievement in math and science: A 30-year meta-analysis, 1986-2015. Educational Research Review, 20 , 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.003 .

Fernández-Alonso, R., Álvarez-Díaz, M., Woitschach, P., Suárez-Álvarez, J., & Cuesta, M. (2017). Parental involvement and academic performance: Less control and more communication. Psicothema, 29 , 453–461. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.181 .

Gao, X., Barkhuizen, G., & Chow, A. (2011). ‘Nowadays, teachers are relatively obedient’: Understanding primary school English teachers’ conceptions of and drives for research in China. Language Teaching Research, 15 , 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810383344 .

Hagger, M. S., Sultan, S., Hardcastle, S. J., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2015). Perceived autonomy support and autonomous motivation toward mathematics activities in educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41 , 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.002 .

Hall, E. T. (1984). The dance of life: The other dimension of time . Garden City: Anchor Press.

Hong, S., Malik, M. L., & Lee, M. K. (2003). Testing configural, metric, scalar, and latent mean invariance across genders in sociotropy and autonomy using a non-Western sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 636–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403251332 .

Hong, E., Peng, Y., & Rowell, L. L. (2009). Homework self-regulation: Grade, gender, and achievement-level differences. Learning and Individual Differences, 19 , 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.11.009 .

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36 , 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5 .

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6 , 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 .

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self-competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73 , 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00421 .

Keith, T. Z. (1986). Homework . West Lafayette: Kappa Delta Pi.

King, R. B., & McInerney, D. M. (2016). Culture and motivation: The road travelled and the way ahead. In K. R. Wentzel & D. B. Miele (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 287–311). New York: Routledge.

King, R. B., Ganotice, F. A., & Watkins, D. A. (2014). A cross-cultural analysis of achievement and social goals among Chinese and Filipino students. Social Psychology of Education, 17 , 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9251-0 .

Leondari, A., & Gonida, E. (2007). Predicting academic self-handicapping in different age groups: The role of personal achievement goals and social goals. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77 , 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X128396 .

Li, J. (2001). Chinese conceptualization of learning. Ethos, 29 , 111–137. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.2001.29.2.111 .

Li, H., & Li, N. (2018). Features and characteristics of Chinese new century mathematics textbooks. In Y. Cao & F. K. S. Leung (Eds.), The 21st century mathematics education in China (pp. 171–192). Berlin: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1 , 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 .

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., Guo, J., Arens, A. K., & Murayama, K. (2016). Breaking the double-edged sword of effort/trying hard: Developmental equilibrium and longitudinal relations among effort, achievement, and academic self-concept. Developmental Psychology, 52 , 1273–1290. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000146 .

Meeuwisse, M., Born, M. P., & Severiens, S. E. (2013). Academic performance differences among ethnic groups: Do the daily use and management of time offer explanations? Social Psychology of Education, 16 , 599–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9231-9 .

Moroni, S., Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Niggli, A., & Baeriswyl, F. (2015). The need to distinguish between quantity and quality in research on parental involvement: The example of parental help with homework. Journal of Educational Research, 108 , 417–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.901283 .

Newsom, J. T. (2015). Longitudinal structural equation modeling: A comprehensive introduction . New York: Routledge.

Niepel, C., Brunner, M., & Preckel, F. (2014). The longitudinal interplay of students’ academic self-concepts and achievements within and across domains: Replicating and extending the reciprocal internal/external frame of reference model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 , 1170–1191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036307 .

Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Boredom and academic achievement: Testing a model of reciprocal causation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 , 696–710. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036006

Phillipson, S. (2006). Cultural variability in parent and child achievement attributions: A study from Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 26 , 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500390772 .

Raftery, J. N., Grolnick, W. S., & Flamm, E. S. (2012). Families as facilitators of student engagement: Towards a home-school partnership. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 343–364). New York: Springer.

Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., Nunes, T., Cunha, J., Fuentes, S., & Valle, A. (2018). Homework purposes, homework behaviors, and academic achievement. Examining the mediating role of students’ perceived homework quality. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53 , 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.04.001 .

Rosário, P., Cunha, J., Nunes, A. R., Moreira, T., Núñez, J. C., & Xu, J. (2019). “Did you do your homework?” Mathematics teachers’ homework follow-up practices at middle school level. Psychology in the Schools, 56 , 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22198 .

Saban, A. İ. (2013). A study of the validity and reliability study of the homework purpose scale: A psychometric evaluation. Measurement, 46 , 4306–4312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2013.08.027 .

Salili, F. Zhou, H., & Hoosain, R. (2003). Adolescent education in Hong Kong and mainland China: Effects of culture and context of learning on Chinese adolescents. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Adolescence and education , Vol. III : International perspectives on adolescence (pp. 277–302). Greenwich: Information Age.

Selig, J. P., & Little, T. D. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data. In B. Laursen, T. D. Little, & N. A. Card (Eds.), Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). New York: Gilford Press.

Strandberg, M. (2013). Homework–is there a connection with classroom assessment? A review from Sweden. Educational Research, 55 , 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.844936 .

Sun, M., Du, J., & Xu, J. (in press). Math homework purpose scale for preadolescents: A psychometric evaluation. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9870-2 .

Tao, V. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (2014). When academic achievement is an obligation: Perspectives from social-oriented achievement motivation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45 , 110–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113490072 .

Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9 , 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740 .

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2004). Reflecting on the homework ritual: Assignments and designs. Theory Into Practice, 43 , 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4303_6 .

Vatterott, C. (2011). Making homework central to learning. Educational Leadership, 69 (3), 60–64.

Warton, P. M. (2001). The forgotten voices in homework: Views of students. Educational Psychologist, 36 , 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_2 .

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Social, emotional, and personality development . Volume 3 of the Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., pp. 933-1002). Editors-in-Chief: W. Damon & R. M. Lerner. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Fredricks, J. A., Simpkins, S., Roeser, R. W., & Schiefele, U. (2015). Development of achievement motivation and engagement. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science , Vol. 3. Socioemotional processes (7th ed., pp. 657-700). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Willoughby, T., Heffer, T., & Hamza, C. A. (2015). The link between nonsuicidal self-injury and acquired capability for suicide: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124 , 1110–1115. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000104 .

Xu, J. (2005). Purposes for doing homework reported by middle and high school students. Journal of Educational Research, 99 , 46–55. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.1.46-55 .

Xu, J. (2006). Gender and homework management reported by high school students. Educational Psychology, 26 , 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410500341023 .

Xu, J. (2008). Models of secondary students’ interest in homework: A multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 45 , 1180–1205. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208323276 .

Xu, J. (2010). Homework purpose scale for high school students: A validation study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70 , 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409344517 .

Xu, J. (2013). Why do students have difficulties completing homework? The need for homework management. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1 (1), 98–105.

Xu, J. (2016). A study of the validity and reliability of the teacher homework involvement scale: A psychometric evaluation. Measurement, 93 , 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2016.07.012 .

Xu, J. (2018). Reciprocal effects of homework self-concept, interest, effort, and math achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 55 , 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.09.002 .

Xu, J., & Corno, L. (1998). Case studies of families doing third-grade homework. Teachers College Record, 100 , 402–436.

Xu, J., & Yuan, R. (2003). Doing homework: Listening to students’, parents’, and teachers’ voices in one urban middle school community. School Community Journal, 13 (2), 25–44.

Xu, J., Du, J., & Fan, X. (2013). "finding our time": Predicting students' time management in online collaborative groupwork. Computers & Education, 69 , 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.012 .

Xu, J., Du, J., Wu, S., Ripple, H., & Cosgriff, A. (2018). Reciprocal effects among parental homework support, effort, and achievement? An empirical investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 2334. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02334 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Younger, M., & Warrington, M. (1996). Differential achievement of girls and boys at GCSE: Some observations from the perspective of one school. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 17 , 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/014256996017030 .

Zhou, N., Lam, S. F., & Chan, K. C. (2012). The Chinese classroom paradox: A cross-cultural comparison of teacher controlling behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 1162–1174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027609 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

University of Macau, Macau, China

Department of Counseling, Educational Psychology, and Foundations, Mississippi State University, P.O. Box 9727, Mississippi State, MS, 39762, USA

Jianzhong Xu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jianzhong Xu .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares no conflict of interest.

Human Studies

All procedures were compliant with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the present investigation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sun, M., Du, J. & Xu, J. Are homework purposes and student achievement reciprocally related? A longitudinal study. Curr Psychol 40 , 4945–4956 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00447-y

Download citation

Published : 09 September 2019

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00447-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Achievement

- Approval-seeking

- Homework purpose

- Longitudinal study

- Self-regulated learning

- Self-regulation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Home » Tips for Teachers » 7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

In recent years, the question of why students should not have homework has become a topic of intense debate among educators, parents, and students themselves. This discussion stems from a growing body of research that challenges the traditional view of homework as an essential component of academic success. The notion that homework is an integral part of learning is being reevaluated in light of new findings about its effectiveness and impact on students’ overall well-being.

The push against homework is not just about the hours spent on completing assignments; it’s about rethinking the role of education in fostering the well-rounded development of young individuals. Critics argue that homework, particularly in excessive amounts, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout, and a diminished love for learning. Moreover, it often disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating educational inequities. The debate also highlights the importance of allowing children to have enough free time for play, exploration, and family interaction, which are crucial for their social and emotional development.

Checking 13yo’s math homework & I have just one question. I can catch mistakes & help her correct. But what do kids do when their parent isn’t an Algebra teacher? Answer: They get frustrated. Quit. Get a bad grade. Think they aren’t good at math. How is homework fair??? — Jay Wamsted (@JayWamsted) March 24, 2022

As we delve into this discussion, we explore various facets of why reducing or even eliminating homework could be beneficial. We consider the research, weigh the pros and cons, and examine alternative approaches to traditional homework that can enhance learning without overburdening students.

Once you’ve finished this article, you’ll know:

- Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts →

- 7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework →

- Opposing Views on Homework Practices →

- Exploring Alternatives to Homework →

Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts: Diverse Perspectives on Homework

In the ongoing conversation about the role and impact of homework in education, the perspectives of those directly involved in the teaching process are invaluable. Teachers and education industry experts bring a wealth of experience and insights from the front lines of learning. Their viewpoints, shaped by years of interaction with students and a deep understanding of educational methodologies, offer a critical lens through which we can evaluate the effectiveness and necessity of homework in our current educational paradigm.

Check out this video featuring Courtney White, a high school language arts teacher who gained widespread attention for her explanation of why she chooses not to assign homework.

Here are the insights and opinions from various experts in the educational field on this topic:

“I teach 1st grade. I had parents ask for homework. I explained that I don’t give homework. Home time is family time. Time to play, cook, explore and spend time together. I do send books home, but there is no requirement or checklist for reading them. Read them, enjoy them, and return them when your child is ready for more. I explained that as a parent myself, I know they are busy—and what a waste of energy it is to sit and force their kids to do work at home—when they could use that time to form relationships and build a loving home. Something kids need more than a few math problems a week.” — Colleen S. , 1st grade teacher

“The lasting educational value of homework at that age is not proven. A kid says the times tables [at school] because he studied the times tables last night. But over a long period of time, a kid who is drilled on the times tables at school, rather than as homework, will also memorize their times tables. We are worried about young children and their social emotional learning. And that has to do with physical activity, it has to do with playing with peers, it has to do with family time. All of those are very important and can be removed by too much homework.” — David Bloomfield , education professor at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York graduate center

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’” — John Hattie , professor

”Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll – psychologically and in many other ways too. We see kids getting up hours before school starts just to get their homework done from the night before… While homework may give kids one more responsibility, it ignores the fact that kids do not need to grow up and become adults at ages 10 or 12. With schools cutting recess time or eliminating playgrounds, kids absorb every single stress there is, only on an even higher level. Their brains and bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.” — Pat Wayman, teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com

7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Let’s delve into the reasons against assigning homework to students. Examining these arguments offers important perspectives on the wider educational and developmental consequences of homework practices.

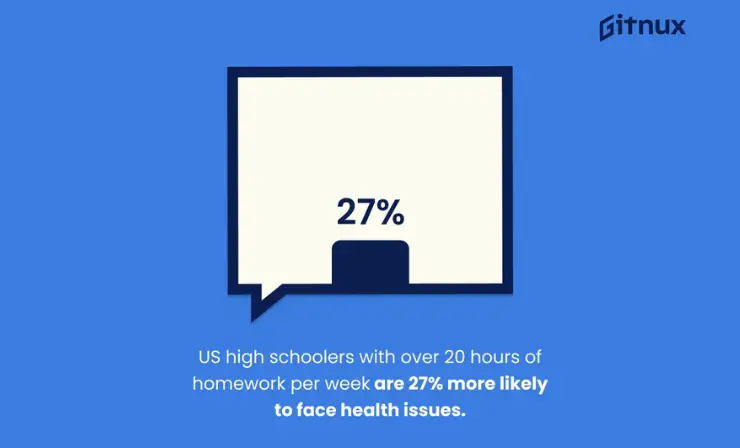

1. Elevated Stress and Health Consequences

The ongoing debate about homework often focuses on its educational value, but a vital aspect that cannot be overlooked is the significant stress and health consequences it brings to students. In the context of American life, where approximately 70% of people report moderate or extreme stress due to various factors like mass shootings, healthcare affordability, discrimination, racism, sexual harassment, climate change, presidential elections, and the need to stay informed, the additional burden of homework further exacerbates this stress, particularly among students.

Key findings and statistics reveal a worrying trend:

- Overwhelming Student Stress: A staggering 72% of students report being often or always stressed over schoolwork, with a concerning 82% experiencing physical symptoms due to this stress.

- Serious Health Issues: Symptoms linked to homework stress include sleep deprivation, headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems.

- Sleep Deprivation: Despite the National Sleep Foundation recommending 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep for healthy adolescent development, students average just 6.80 hours of sleep on school nights. About 68% of students stated that schoolwork often or always prevented them from getting enough sleep, which is critical for their physical and mental health.

- Turning to Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Alarmingly, the pressure from excessive homework has led some students to turn to alcohol and drugs as a way to cope with stress.

This data paints a concerning picture. Students, already navigating a world filled with various stressors, find themselves further burdened by homework demands. The direct correlation between excessive homework and health issues indicates a need for reevaluation. The goal should be to ensure that homework if assigned, adds value to students’ learning experiences without compromising their health and well-being.

By addressing the issue of homework-related stress and health consequences, we can take a significant step toward creating a more nurturing and effective educational environment. This environment would not only prioritize academic achievement but also the overall well-being and happiness of students, preparing them for a balanced and healthy life both inside and outside the classroom.

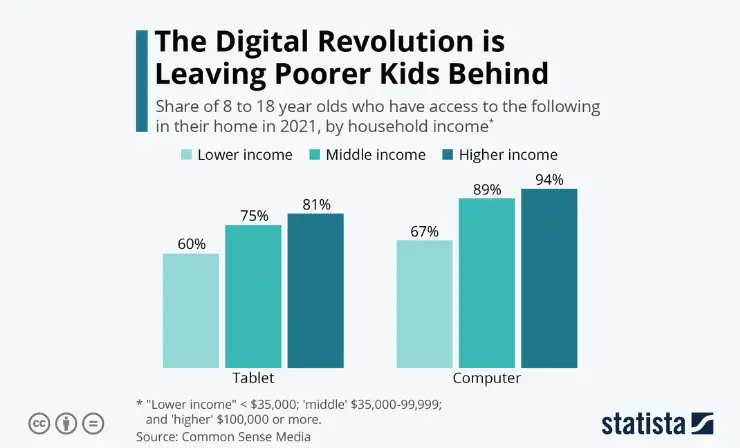

2. Inequitable Impact and Socioeconomic Disparities

In the discourse surrounding educational equity, homework emerges as a factor exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, particularly affecting students from lower-income families and those with less supportive home environments. While homework is often justified as a means to raise academic standards and promote equity, its real-world impact tells a different story.

The inequitable burden of homework becomes starkly evident when considering the resources required to complete it, especially in the digital age. Homework today often necessitates a computer and internet access – resources not readily available to all students. This digital divide significantly disadvantages students from lower-income backgrounds, deepening the chasm between them and their more affluent peers.

Key points highlighting the disparities:

- Digital Inequity: Many students lack access to necessary technology for homework, with low-income families disproportionately affected.

- Impact of COVID-19: The pandemic exacerbated these disparities as education shifted online, revealing the extent of the digital divide.

- Educational Outcomes Tied to Income: A critical indicator of college success is linked more to family income levels than to rigorous academic preparation. Research indicates that while 77% of students from high-income families graduate from highly competitive colleges, only 9% from low-income families achieve the same . This disparity suggests that the pressure of heavy homework loads, rather than leveling the playing field, may actually hinder the chances of success for less affluent students.

Moreover, the approach to homework varies significantly across different types of schools. While some rigorous private and preparatory schools in both marginalized and affluent communities assign extreme levels of homework, many progressive schools focusing on holistic learning and self-actualization opt for no homework, yet achieve similar levels of college and career success. This contrast raises questions about the efficacy and necessity of heavy homework loads in achieving educational outcomes.

The issue of homework and its inequitable impact is not just an academic concern; it is a reflection of broader societal inequalities. By continuing practices that disproportionately burden students from less privileged backgrounds, the educational system inadvertently perpetuates the very disparities it seeks to overcome.

3. Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

Homework, a staple of the educational system, is often perceived as a necessary tool for academic reinforcement. However, its impact extends beyond the realm of academics, significantly affecting family dynamics. The negative repercussions of homework on the home environment have become increasingly evident, revealing a troubling pattern that can lead to conflict, mental health issues, and domestic friction.

A study conducted in 2015 involving 1,100 parents sheds light on the strain homework places on family relationships. The findings are telling:

- Increased Likelihood of Conflicts: Families where parents did not have a college degree were 200% more likely to experience fights over homework.

- Misinterpretations and Misunderstandings: Parents often misinterpret their children’s difficulties with homework as a lack of attention in school, leading to feelings of frustration and mistrust on both sides.

- Discriminatory Impact: The research concluded that the current approach to homework disproportionately affects children whose parents have lower educational backgrounds, speak English as a second language, or belong to lower-income groups.

The issue is not confined to specific demographics but is a widespread concern. Samantha Hulsman, a teacher featured in Education Week Teacher , shared her personal experience with the toll that homework can take on family time. She observed that a seemingly simple 30-minute assignment could escalate into a three-hour ordeal, causing stress and strife between parents and children. Hulsman’s insights challenge the traditional mindset about homework, highlighting a shift towards the need for skills such as collaboration and problem-solving over rote memorization of facts.

The need of the hour is to reassess the role and amount of homework assigned to students. It’s imperative to find a balance that facilitates learning and growth without compromising the well-being of the family unit. Such a reassessment would not only aid in reducing domestic conflicts but also contribute to a more supportive and nurturing environment for children’s overall development.

4. Consumption of Free Time

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices has raised concerns about the excessive burden of homework on students, emphasizing how it consumes their free time and impedes their overall well-being. The issue is not just the quantity of homework, but its encroachment on time that could be used for personal growth, relaxation, and family bonding.

Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish , in their book “The Case Against Homework,” offer an insightful window into the lives of families grappling with the demands of excessive homework. They share stories from numerous interviews conducted in the mid-2000s, highlighting the universal struggle faced by families across different demographics. A poignant account from a parent in Menlo Park, California, describes nightly sessions extending until 11 p.m., filled with stress and frustration, leading to a soured attitude towards school in both the child and the parent. This narrative is not isolated, as about one-third of the families interviewed expressed feeling crushed by the overwhelming workload.

Key points of concern:

- Excessive Time Commitment: Students, on average, spend over 6 hours in school each day, and homework adds significantly to this time, leaving little room for other activities.

- Impact on Extracurricular Activities: Homework infringes upon time for sports, music, art, and other enriching experiences, which are as crucial as academic courses.

- Stifling Creativity and Self-Discovery: The constant pressure of homework limits opportunities for students to explore their interests and learn new skills independently.

The National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA) recommend a “10 minutes of homework per grade level” standard, suggesting a more balanced approach. However, the reality often far exceeds this guideline, particularly for older students. The impact of this overreach is profound, affecting not just academic performance but also students’ attitudes toward school, their self-confidence, social skills, and overall quality of life.

Furthermore, the intense homework routine’s effectiveness is doubtful, as it can overwhelm students and detract from the joy of learning. Effective learning builds on prior knowledge in an engaging way, but excessive homework in a home setting may be irrelevant and uninteresting. The key challenge is balancing homework to enhance learning without overburdening students, allowing time for holistic growth and activities beyond academics. It’s crucial to reassess homework policies to support well-rounded development.

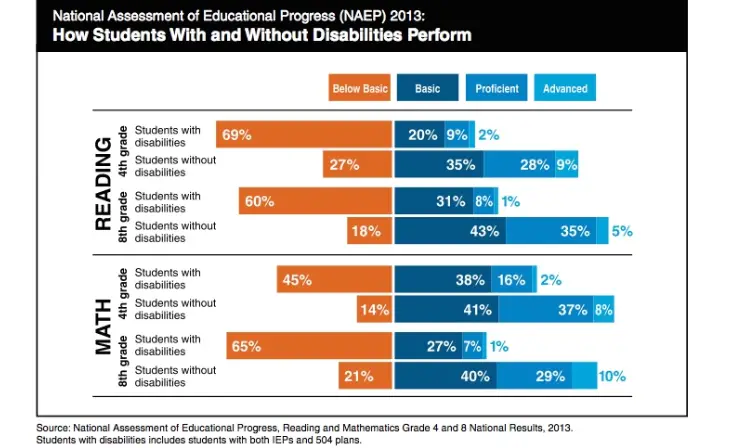

5. Challenges for Students with Learning Disabilities

Homework, a standard educational tool, poses unique challenges for students with learning disabilities, often leading to a frustrating and disheartening experience. These challenges go beyond the typical struggles faced by most students and can significantly impede their educational progress and emotional well-being.

Child psychologist Kenneth Barish’s insights in Psychology Today shed light on the complex relationship between homework and students with learning disabilities:

- Homework as a Painful Endeavor: For students with learning disabilities, completing homework can be likened to “running with a sprained ankle.” It’s a task that, while doable, is fraught with difficulty and discomfort.

- Misconceptions about Laziness: Often, children who struggle with homework are perceived as lazy. However, Barish emphasizes that these students are more likely to be frustrated, discouraged, or anxious rather than unmotivated.

- Limited Improvement in School Performance: The battles over homework rarely translate into significant improvement in school for these children, challenging the conventional notion of homework as universally beneficial.

These points highlight the need for a tailored approach to homework for students with learning disabilities. It’s crucial to recognize that the traditional homework model may not be the most effective or appropriate method for facilitating their learning. Instead, alternative strategies that accommodate their unique needs and learning styles should be considered.

In conclusion, the conventional homework paradigm needs reevaluation, particularly concerning students with learning disabilities. By understanding and addressing their unique challenges, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. This approach not only aids in their academic growth but also nurtures their confidence and overall development, ensuring that they receive an equitable and empathetic educational experience.

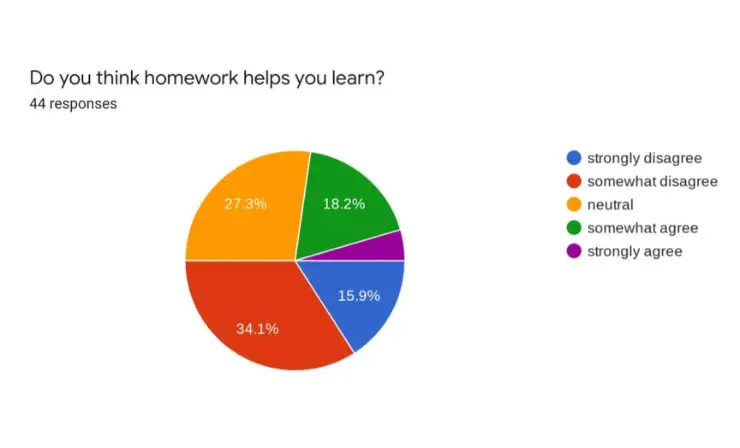

6. Critique of Underlying Assumptions about Learning

The longstanding belief in the educational sphere that more homework automatically translates to more learning is increasingly being challenged. Critics argue that this assumption is not only flawed but also unsupported by solid evidence, questioning the efficacy of homework as an effective learning tool.

Alfie Kohn , a prominent critic of homework, aptly compares students to vending machines in this context, suggesting that the expectation of inserting an assignment and automatically getting out of learning is misguided. Kohn goes further, labeling homework as the “greatest single extinguisher of children’s curiosity.” This critique highlights a fundamental issue: the potential of homework to stifle the natural inquisitiveness and love for learning in children.

The lack of concrete evidence supporting the effectiveness of homework is evident in various studies:

- Marginal Effectiveness of Homework: A study involving 28,051 high school seniors found that the effectiveness of homework was marginal, and in some cases, it was counterproductive, leading to more academic problems than solutions.

- No Correlation with Academic Achievement: Research in “ National Differences, Global Similarities ” showed no correlation between homework and academic achievement in elementary students, and any positive correlation in middle or high school diminished with increasing homework loads.

- Increased Academic Pressure: The Teachers College Record published findings that homework adds to academic pressure and societal stress, exacerbating performance gaps between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

These findings bring to light several critical points:

- Quality Over Quantity: According to a recent article in Monitor on Psychology , experts concur that the quality of homework assignments, along with the quality of instruction, student motivation, and inherent ability, is more crucial for academic success than the quantity of homework.

- Counterproductive Nature of Excessive Homework: Excessive homework can lead to more academic challenges, particularly for students already facing pressures from other aspects of their lives.

- Societal Stress and Performance Gaps: Homework can intensify societal stress and widen the academic performance divide.

The emerging consensus from these studies suggests that the traditional approach to homework needs rethinking. Rather than focusing on the quantity of assignments, educators should consider the quality and relevance of homework, ensuring it truly contributes to learning and development. This reassessment is crucial for fostering an educational environment that nurtures curiosity and a love for learning, rather than extinguishing it.

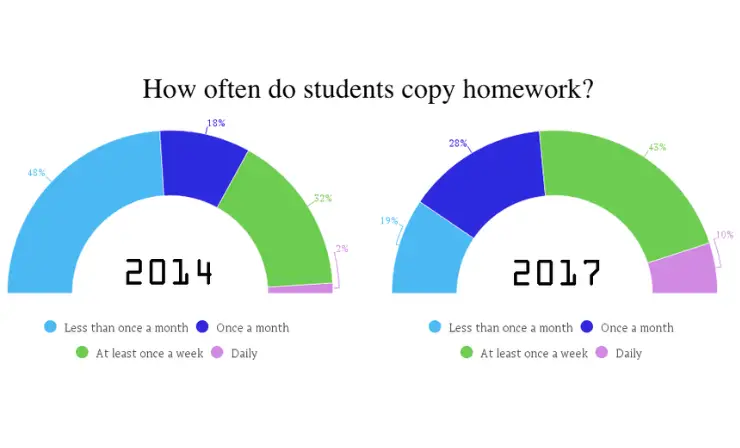

7. Issues with Homework Enforcement, Reliability, and Temptation to Cheat

In the academic realm, the enforcement of homework is a subject of ongoing debate, primarily due to its implications on student integrity and the true value of assignments. The challenges associated with homework enforcement often lead to unintended yet significant issues, such as cheating, copying, and a general undermining of educational values.

Key points highlighting enforcement challenges:

- Difficulty in Enforcing Completion: Ensuring that students complete their homework can be a complex task, and not completing homework does not always correlate with poor grades.

- Reliability of Homework Practice: The reliability of homework as a practice tool is undermined when students, either out of desperation or lack of understanding, choose shortcuts over genuine learning. This approach can lead to the opposite of the intended effect, especially when assignments are not well-aligned with the students’ learning levels or interests.

- Temptation to Cheat: The issue of cheating is particularly troubling. According to a report by The Chronicle of Higher Education , under the pressure of at-home assignments, many students turn to copying others’ work, plagiarizing, or using creative technological “hacks.” This tendency not only questions the integrity of the learning process but also reflects the extreme stress that homework can induce.

- Parental Involvement in Completion: As noted in The American Journal of Family Therapy , this raises concerns about the authenticity of the work submitted. When parents complete assignments for their children, it not only deprives the students of the opportunity to learn but also distorts the purpose of homework as a learning aid.

In conclusion, the challenges of homework enforcement present a complex problem that requires careful consideration. The focus should shift towards creating meaningful, manageable, and quality-driven assignments that encourage genuine learning and integrity, rather than overwhelming students and prompting counterproductive behaviors.

Addressing Opposing Views on Homework Practices

While opinions on homework policies are diverse, understanding different viewpoints is crucial. In the following sections, we will examine common arguments supporting homework assignments, along with counterarguments that offer alternative perspectives on this educational practice.

1. Improvement of Academic Performance

Homework is commonly perceived as a means to enhance academic performance, with the belief that it directly contributes to better grades and test scores. This view posits that through homework, students reinforce what they learn in class, leading to improved understanding and retention, which ultimately translates into higher academic achievement.

However, the question of why students should not have homework becomes pertinent when considering the complex relationship between homework and academic performance. Studies have indicated that excessive homework doesn’t necessarily equate to higher grades or test scores. Instead, too much homework can backfire, leading to stress and fatigue that adversely affect a student’s performance. Reuters highlights an intriguing correlation suggesting that physical activity may be more conducive to academic success than additional homework, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach to education that prioritizes both physical and mental well-being for enhanced academic outcomes.

2. Reinforcement of Learning

Homework is traditionally viewed as a tool to reinforce classroom learning, enabling students to practice and retain material. However, research suggests its effectiveness is ambiguous. In instances where homework is well-aligned with students’ abilities and classroom teachings, it can indeed be beneficial. Particularly for younger students , excessive homework can cause burnout and a loss of interest in learning, counteracting its intended purpose.

Furthermore, when homework surpasses a student’s capability, it may induce frustration and confusion rather than aid in learning. This challenges the notion that more homework invariably leads to better understanding and retention of educational content.

3. Development of Time Management Skills

Homework is often considered a crucial tool in helping students develop important life skills such as time management and organization. The idea is that by regularly completing assignments, students learn to allocate their time efficiently and organize their tasks effectively, skills that are invaluable in both academic and personal life.

However, the impact of homework on developing these skills is not always positive. For younger students, especially, an overwhelming amount of homework can be more of a hindrance than a help. Instead of fostering time management and organizational skills, an excessive workload often leads to stress and anxiety . These negative effects can impede the learning process and make it difficult for students to manage their time and tasks effectively, contradicting the original purpose of homework.

4. Preparation for Future Academic Challenges

Homework is often touted as a preparatory tool for future academic challenges that students will encounter in higher education and their professional lives. The argument is that by tackling homework, students build a foundation of knowledge and skills necessary for success in more advanced studies and in the workforce, fostering a sense of readiness and confidence.

Contrarily, an excessive homework load, especially from a young age, can have the opposite effect . It can instill a negative attitude towards education, dampening students’ enthusiasm and willingness to embrace future academic challenges. Overburdening students with homework risks disengagement and loss of interest, thereby defeating the purpose of preparing them for future challenges. Striking a balance in the amount and complexity of homework is crucial to maintaining student engagement and fostering a positive attitude towards ongoing learning.

5. Parental Involvement in Education

Homework often acts as a vital link connecting parents to their child’s educational journey, offering insights into the school’s curriculum and their child’s learning process. This involvement is key in fostering a supportive home environment and encouraging a collaborative relationship between parents and the school. When parents understand and engage with what their children are learning, it can significantly enhance the educational experience for the child.

However, the line between involvement and over-involvement is thin. When parents excessively intervene by completing their child’s homework, it can have adverse effects . Such actions not only diminish the educational value of homework but also rob children of the opportunity to develop problem-solving skills and independence. This over-involvement, coupled with disparities in parental ability to assist due to variations in time, knowledge, or resources, may lead to unequal educational outcomes, underlining the importance of a balanced approach to parental participation in homework.

Exploring Alternatives to Homework and Finding a Middle Ground

In the ongoing debate about the role of homework in education, it’s essential to consider viable alternatives and strategies to minimize its burden. While completely eliminating homework may not be feasible for all educators, there are several effective methods to reduce its impact and offer more engaging, student-friendly approaches to learning.

Alternatives to Traditional Homework

- Project-Based Learning: This method focuses on hands-on, long-term projects where students explore real-world problems. It encourages creativity, critical thinking, and collaborative skills, offering a more engaging and practical learning experience than traditional homework. For creative ideas on school projects, especially related to the solar system, be sure to explore our dedicated article on solar system projects .

- Flipped Classrooms: Here, students are introduced to new content through videos or reading materials at home and then use class time for interactive activities. This approach allows for more personalized and active learning during school hours.

- Reading for Pleasure: Encouraging students to read books of their choice can foster a love for reading and improve literacy skills without the pressure of traditional homework assignments. This approach is exemplified by Marion County, Florida , where public schools implemented a no-homework policy for elementary students. Instead, they are encouraged to read nightly for 20 minutes . Superintendent Heidi Maier’s decision was influenced by research showing that while homework offers minimal benefit to young students, regular reading significantly boosts their learning. For book recommendations tailored to middle school students, take a look at our specially curated article .

Ideas for Minimizing Homework

- Limiting Homework Quantity: Adhering to guidelines like the “ 10-minute rule ” (10 minutes of homework per grade level per night) can help ensure that homework does not become overwhelming.

- Quality Over Quantity: Focus on assigning meaningful homework that is directly relevant to what is being taught in class, ensuring it adds value to students’ learning.

- Homework Menus: Offering students a choice of assignments can cater to diverse learning styles and interests, making homework more engaging and personalized.

- Integrating Technology: Utilizing educational apps and online platforms can make homework more interactive and enjoyable, while also providing immediate feedback to students. To gain deeper insights into the role of technology in learning environments, explore our articles discussing the benefits of incorporating technology in classrooms and a comprehensive list of educational VR apps . These resources will provide you with valuable information on how technology can enhance the educational experience.

For teachers who are not ready to fully eliminate homework, these strategies offer a compromise, ensuring that homework supports rather than hinders student learning. By focusing on quality, relevance, and student engagement, educators can transform homework from a chore into a meaningful component of education that genuinely contributes to students’ academic growth and personal development. In this way, we can move towards a more balanced and student-centric approach to learning, both in and out of the classroom.

Useful Resources

- Is homework a good idea or not? by BBC

- The Great Homework Debate: What’s Getting Lost in the Hype

- Alternative Homework Ideas

The evidence and arguments presented in the discussion of why students should not have homework call for a significant shift in homework practices. It’s time for educators and policymakers to rethink and reformulate homework strategies, focusing on enhancing the quality, relevance, and balance of assignments. By doing so, we can create a more equitable, effective, and student-friendly educational environment that fosters learning, well-being, and holistic development.

- “Here’s what an education expert says about that viral ‘no-homework’ policy”, Insider

- “John Hattie on BBC Radio 4: Homework in primary school has an effect of zero”, Visible Learning

- HowtoLearn.com

- “Time Spent On Homework Statistics [Fresh Research]”, Gitnux

- “Stress in America”, American Psychological Association (APA)

- “Homework hurts high-achieving students, study says”, The Washington Post

- “National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report”, National Library of Medicine

- “A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools”, Frontiers

- “The Digital Revolution is Leaving Poorer Kids Behind”, Statista

- “The digital divide has left millions of school kids behind”, CNET

- “The Digital Divide: What It Is, and What’s Being Done to Close It”, Investopedia

- “COVID-19 exposed the digital divide. Here’s how we can close it”, World Economic Forum

- “PBS NewsHour: Biggest Predictor of College Success is Family Income”, America’s Promise Alliance

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, Taylor & Francis Online

- “What Do You Mean My Kid Doesn’t Have Homework?”, EducationWeek

- “Excerpt From The Case Against Homework”, Penguin Random House Canada

- “How much homework is too much?”, neaToday

- “The Nation’s Report Card: A First Look: 2013 Mathematics and Reading”, National Center for Education Statistics

- “Battles Over Homework: Advice For Parents”, Psychology Today

- “How Homework Is Destroying Teens’ Health”, The Lion’s Roar

- “ Breaking the Homework Habit”, Education World

- “Testing a model of school learning: Direct and indirect effects on academic achievement”, ScienceDirect

- “National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling”, Stanford University Press

- “When school goes home: Some problems in the organization of homework”, APA PsycNet

- “Is homework a necessary evil?”, APA PsycNet

- “Epidemic of copying homework catalyzed by technology”, Redwood Bark

- “High-Tech Cheating Abounds, and Professors Bear Some Blame”, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “Homework and Family Stress: With Consideration of Parents’ Self Confidence, Educational Level, and Cultural Background”, ResearchGate

- “Kids who get moving may also get better grades”, Reuters

- “Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987–2003”, SageJournals

- “Is it time to get rid of homework?”, USAToday

- “Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework”, Stanford

- “Florida school district bans homework, replaces it with daily reading”, USAToday

- “Encouraging Students to Read: Tips for High School Teachers”, wgu.edu

- Recent Posts

Simona Johnes is the visionary being the creation of our project. Johnes spent much of her career in the classroom working with students. And, after many years in the classroom, Johnes became a principal.

- 22 Essential Strategies to Check for Understanding: Enhancing Classroom Engagement and Learning - May 20, 2024

- 24 Innovative and Fun Periodic Table Project Ideas to Engage and Inspire Students in Chemistry Learning - May 9, 2024

- 28 Exciting Yarn Crafts for Preschool Kids: Igniting Creativity and Fine Motor Skills - April 29, 2024

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

(1996). The Impact of Purposeful Homework on Learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas: Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 346-348.

By creating a homework culture that emphasizes quality, provides timely feedback, and considers student circumstances, educators can optimize the positive impact of homework on student learning ...

Published 1 August 1996. Education. The Clearing House. (1996). The Impact of Purposeful Homework on Learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas: Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 346-348. View via Publisher. Save to Library. Create Alert.

Highschool homework as an integral part of the study skills benefits students' learning outcomes significantly. Consistency of completing homework contributes to rising scores in any given assignment such as quizzes, regular tests, standardized tests, etc. The purpose of homework aims at different targets and it is designed for specific groups

Studies have shown that each of these roles of homework can contribute to the facilitation of meaningful learning and the support of students toward becoming self-initiated learners. However, there are some crucial challenges that remain in applying this knowledge to the actual school setting. This paper's conclusion discusses possible ...

Fifty-four characteristics of treatments, contexts, conditions, validity, and outcomes were coded for each study. About 85% of the effect sizes favored the homework groups. The mean effect size is .36 (probability less than .0001). Homework that was graded or contained teachers' comments produced stronger ef.

optimize the positive impact of homework on student learning and academic performance. KEYWORDS: ... First, homework assignments should be purposeful, clearly aligned with instructional goals, and ...

Abstract. In this day of standards-based learning goals and differentiated curricula, effective homework practices must be purposefully defined, educationally defensible, and thoughtfully designed ...

Semantic Scholar extracted view of "Homework as a Learning Experience. What Research Says to the Teacher. Third Edition." by M. A. Doyle et al. ... The Impact of Purposeful Homework on Learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas: Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 346-348. 27.

Recently, Rosário et al. (2015a) found that homework assignments with the purpose of promoting the transfer of learning (i.e. extension) had a stronger positive impact on 6th graders' mathematics achievement than homework with the purpose of practice or preparation.

3. Homework that is linked to classroom work tends to be more effective. In particular, studies that included feedback on homework had higher impacts on learning. 4. It is important to make the purpose of homework clear to pupils (e.g. to increase a specific area of knowledge, or to develop fluency in a particular area).

The current study examines reciprocal influences of homework purposes (approval-seeking, self-regulatory, and academic) and math achievement, using data from 1365 students in grade 8 at two measurement points. Results indicated there were positive reciprocal influences of (a) academic purpose and achievement, and (b) academic purpose and self-regulatory purpose. Results further revealed that ...

Homework provides children with time and homework for its value in reinforcing daily learn-. experience to develop positive beliefs about ing and fostering the development of study achievement, as well as strategies for coping with a backlash against the practice has been mistakes, difficulties, and setbacks. This article since the 1990s.

Cathy Vatterott (2010) identified five fundamental characteristics of good homework: purpose, efficiency, ownership, competence, and aesthetic appeal. Purpose: all homework assignments are meaningful & students must also understand the purpose of the assignment and why it is important in the context of their academic experience (Xu, 2011).

Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and ...

The Impact of Purposeful Homework on Learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas: Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 346-348. 27. Save. The effects of practice and working-practice homework on the math achievement of elementary school students showing varying levels of math performance.

Ramdass and Zimmerman (2011) note that homework enhances students' self-regulation which. promotes students' motivation, cognitive, and metacognitive skills in language learning. This makes ...

Particularly for younger students, excessive homework can cause burnout and a loss of interest in learning, counteracting its intended purpose. ... However, the impact of homework on developing these skills is not always positive. For younger students, especially, an overwhelming amount of homework can be more of a hindrance than a help. ...