- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

performance art

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Art Story - Performance Art

- Art in Context - Performance Art – A Look at the Types of Performance Art

- Khan Academy - Performance Art: An Introduction

performance art , a time-based art form that typically features a live presentation to an audience or to onlookers (as on a street) and draws on such arts as acting , poetry , music , dance , and painting . It is generally an event rather than an artifact , by nature ephemeral , though it is often recorded on video and by means of still photography .

Performance art arose in the early 1970s as a general term for a multitude of activities—including Happenings , body art, actions, events, and guerrilla theatre . It can embrace a wide diversity of styles. In the 1970s and ’80s, performance art ranged from Laurie Anderson ’s elaborate media spectacles to Carolee Schneeman’s body ritual and from the camp glamour of the collective known as General Idea to Joseph Beuys ’s illustrated lectures. In the 1990s it ranged from Ron Athey’s AIDS activism to Orlan’s use of cosmetic surgery on her own body. And in the early 21st century, Marina Abramović rekindled a great interest in the medium through her re-creation of historical pieces.

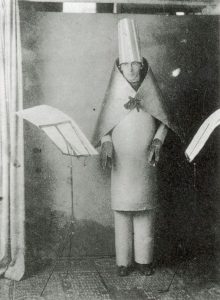

Performance art has its origins in the early 20th century, and it is closely identified with the progress of the avant-garde, beginning with Futurism . The Futurists’ attempt to revolutionize culture included performative evenings of poetry, music played on newly invented instruments, and a form of drastically distilled dramatic presentation. Such elements of Futurist events as simultaneity and noise-music were subsequently refined by artists of the Dada movement, which made great use of live art. Both Futurists and Dadaists worked to confound the barrier between actor and performer, and both capitalized on the publicity value of shock and outrage. An early theorist and practitioner in avant-garde theatre was the German artist Oskar Schlemmer , who taught at the Bauhaus from 1920 to 1929 and is perhaps best known for Das triadische Ballet (1916–22; “The Triadic Ballet”), which called for complex movements and elaborate costumes. Schlemmer presented his ideas in essays in a collective publication, Die Bühne im Bauhaus (1924; The Theater of the Bauhaus ), edited by Walter Gropius .

Subsequent important developments in performance art occurred in the United States after World War II . In 1952, at Black Mountain College (1933–57) in North Carolina , the experimental composer John Cage organized an event that included performances by the choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham , the poet Charles Olson , and the artist Robert Rauschenberg , among others. In its denial of traditional disciplinary boundaries, this influential event set a pattern for Happenings and Fluxus activities and provided an impetus for much of the live art of the following decade. In the 1960s and ’70s, performance art was characterized by improvisation , spontaneity, audience interaction, and political agitation. It also became a favourite strategy of feminist artists—such as the gorilla-masked Guerrilla Girls , whose mission was to expose sexism, racism, and corruption mainly in the art world—as well as of artists elsewhere in the world, such as the Chinese artist Zhang Huan . Popular manifestations of the genre can be seen in Blue Man Group and such events as the Burning Man festival, held annually in the Black Rock Desert , Nevada.

Performance Art

Summary of Performance Art

Performance is a genre in which art is presented "live," usually by the artist but sometimes with collaborators or performers. It has had a role in avant-garde art throughout the 20 th century, playing an important part in anarchic movements such as Futurism and Dada . Indeed, whenever artists have become discontented with conventional forms of art, such as painting and traditional modes of sculpture, they have often turned to performance as a means to rejuvenate their work. The most significant flourishing of performance art took place following the decline of modernism and Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s, and it found exponents across the world. Performance art of this period was particularly focused on the body, and is often referred to as Body art . This reflects the period's so-called "dematerialization of the art object," and the flight from traditional media. It also reflects the political ferment of the time: the rise of feminism , which encouraged thought about the division between the personal and political and anti-war activism, which supplied models for politicized art "actions." Although the concerns of performance artists have changed since the 1960s, the genre has remained a constant presence, and has largely been welcomed into the conventional museums and galleries from which it was once excluded.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The foremost purpose of performance art has almost always been to challenge the conventions of traditional forms of visual art such as painting and sculpture. When these modes no longer seem to answer artists' needs - when they seem too conservative, or too enmeshed in the traditional art world and too distant from ordinary people - artists have often turned to performance in order to find new audiences and test new ideas.

- Performance art borrows styles and ideas from other forms of art, or sometimes from other forms of activity not associated with art, like ritual, or work-like tasks. If cabaret and vaudeville inspired aspects of Dada performance, this reflects Dada's desire to embrace popular art forms and mass cultural modes of address. More recently, performance artists have borrowed from dance, and even sport.

- Some varieties of performance from the post-war period are commonly described as "actions." German artists like Joseph Beuys preferred this term because it distinguished art performance from the more conventional kinds of entertainment found in theatre. But the term also reflects a strain of American performance art that could be said to have emerged out of a reinterpretation of " action painting ," in which the object of art is no longer paint on canvas, but something else - often the artist's own body.

- The focus on the body in so much Performance art of the 1960s has sometimes been seen as a consequence of the abandonment of conventional mediums. Some saw this as a liberation, part of the period's expansion of materials and media. Others wondered if it reflected a more fundamental crisis in the institution of art itself, a sign that art was exhausting its resources.

- The performance art of the 1960s can be seen as just one of the many disparate trends that developed in the wake of Minimalism . Seen in this way, it is an aspect of Post-Minimalism , and it could be seen to share qualities of Process art , another tendency central to that umbrella style. If Process art focused attention on the techniques and materials of art production. Process art was also often intrigued by the possibilities of mundane and repetitive actions; similarly, many performance artists were attracted to task-based activities that were very foreign to the highly choreographed and ritualized performances in traditional theatre or dance.

Key Artists

Overview of Performance Art

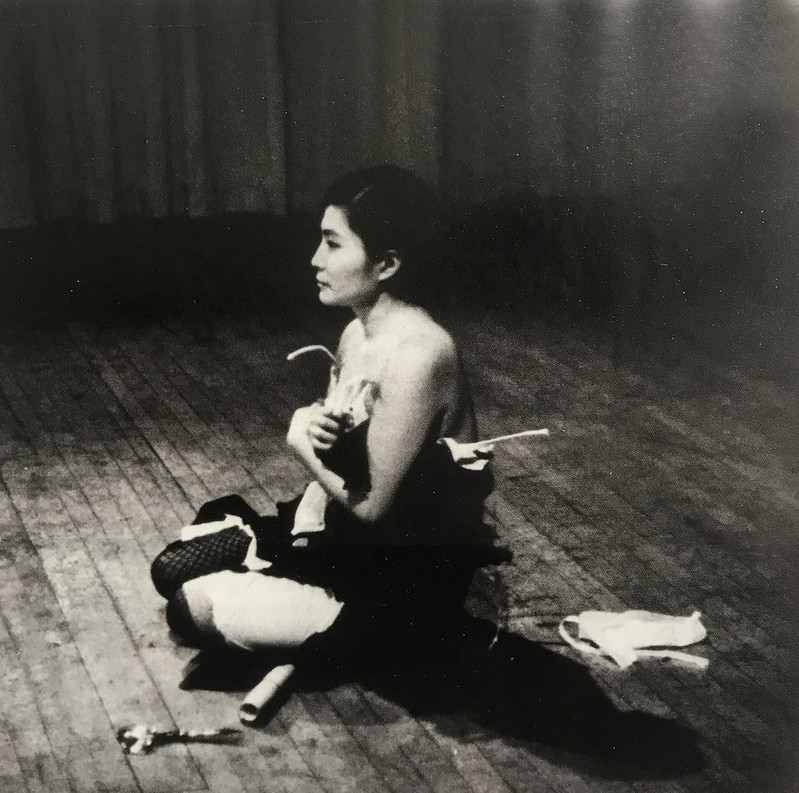

Yoko Ono said, “I thought art was a verb, rather than a noun,” and embodied the concept in her Cut Piece (1964) – pioneering Performance Art – where, holding a pair of scissors and kneeling on stage, she invited the audience to cut away pieces of her clothing.

Artworks and Artists of Performance Art

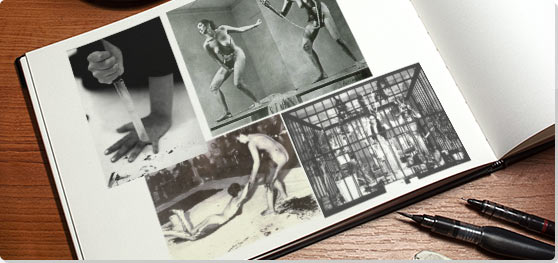

The Anthropometries of the Blue Period

Artist: Yves Klein

Although painting sat at the center of Yves Klein's practice, his approach to it was highly unconventional, and some critics have seen him as the paradigmatic neo-avant-garde artist of the post-war years. He initially became famous for monochromes - in particular for monochromes made with an intense shade of blue that Klein eventually patented. But he was also interested in Conceptual art and performance. For the Anthropometries , he painted actresses in blue paint and had them slather about on the floor to create body-shaped forms. In some cases, Klein made finished paintings from these actions; at other times he simply performed the stunt in front of finely dressed gallery audiences, and often with the accompaniment of chamber music. By removing all barriers between the human and the painting, Klein said, "[the models] became living brushes...at my direction the flesh itself applied the color to the surface and with perfect exactness." It has been suggested that the pictures were inspired by marks left on the ground in Hiroshima and Nagasaki following the atomic explosions in 1945.

Performed at Robert Godet's, Paris 1958 and at Galerie Internationale d'Art Contemporain, Paris 1960

Artist: Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece , first performed in 1964, was a direct invitation to an audience to participate in an unveiling of the female body much as artists had been doing throughout history. By creating this piece as a live experience, Ono hoped to erase the neutrality and anonymity typically associated with society’s objectification of women in art. For the work, Ono sat silent upon a stage as viewers walked up to her and cut away her clothing with a pair of scissors. This forced people to take responsibility for their voyeurism and to reflect upon how even passive witnessing could potentially harm the subject of perception. It was not only a strong feminist statement about the dangers of objectification, but became an opportunity for both artist and audience members to fill roles as both creator and artwork.

Performed at Yamaichi Concert Hall, Kyoto, Japan 1964

Artist: Chris Burden

In many of his early 1970s performance pieces, Burden put himself in danger, thus placing the viewer in a difficult position, caught between a humanitarian instinct to intervene and the taboo against touching and interacting with art pieces. To perform Shoot , Burden stood in front of a wall while one friend shot him in the arm with a .22 long rifle, and another friend documented the event with a camera. It was performed in front of a small, private audience. One of Burden's most notorious and violent performances, it touches on the idea of martyrdom, and the notion that the artist may play a role in society as a kind of scapegoat. It might also speak to issues of gun control and, in the context of the period, the Vietnam War.

Performed at F Space, Santa Ana, California

Artist: Vito Acconci

In Seedbed , 1972 Vito Acconci laid underneath a custom made ramp that extended from two feet up one wall of the Sonnabend Gallery and sloped down to the middle of the floor. For eight hours a day during the course of the exhibition, Acconci laid underneath the ramp masturbating as guest’s walked above his hidden niche. As he performed this illicit act he would utter fantasies and obscenities toward the gallery guests into a microphone, which became audibly piped out through the room for all to hear. The piece placed Acconci in a position that was both public and private. It also created a provocative intimacy between artist and audience that produced multiple levels of feeling. Participants were prone to shock, discomfort, or perhaps even arousal. By positioning himself in two roles, both as giver and receiver of pleasure, Acconci furthered body art’s dictum of artist and artwork merging as one. He also used his sperm as a medium within the piece.

Performed at Sonnabend Gallery in New York City 1972

Artist: Marina Abramović

In Rhythm 10 , Abramović uses a series of 20 knives to quickly stab at the spaces between her outstretched fingers. Every time she pierces her skin, she selects another knife from those carefully laid out in front of her. Halfway through, she begins playing a recording of the first half of the hour-long performance, using the rhythmic beat of the knives striking the floor, and her hand, to repeat the same movements, cutting herself at the same time. This piece exemplifies Abramović's use of ritual in her work, and demonstrates what the artist describes as the synchronicity between the mistakes of the past and those of the present.

Performed at a festival in Edinburgh

Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me

Artist: Joseph Beuys

For three consecutive days in May, 1974, Beuys enclosed himself in a gallery with a wild coyote. Having previously announced that he would not enter the United States while the Vietnam War proceeded, this piece was his first and only action in America, and Beuys was ferried between the airport and the gallery in an ambulance to ensure that his feet did not have to touch American soil. Coyote centered on ideas of America wild and tamed. In an attempt to connect with an idea of wild, pre-colonial America, Beuys lived with a coyote for several days, attempting to communicate with it. He organized a sequence of interactions that would repeat for the duration of the piece, such as cloaking himself in felt and using a cane as a "lightening rod," and following the coyote around the room, bent at the waist and keeping the cane pointed at the coyote. Copies of The Wall Street Journal arrived daily, and were used as a toilet by the coyote, as if to say, "everything that claims to be a part of America is part of my territory."

Performed at Rene Block Gallery, New York NY

Interior Scroll

Artist: Carolee Schneemann

Carolee Schneemann, who defines herself as a multi-disciplinary artist, working across a variety of media, first made an impact in the context of feminist art. Interior Scroll is one of her most famous works. To stage it, she smeared her nude body with paint, mounted a table, and began adopting some of the typical poses that models strike for artists in life class. Then she proceeded to extract a long coil of paper from her vagina, and began to read the text written on it. It was once thought that the text derived from her response to a male filmmaker's critique of her films (some of her most notable films of the time included imagery of the Vietnam War, and documentation of a performance entitled Meat Joy , involving nude bodies writhing about in meat). The filmmaker had apparently commented on her penchant for "personal clutter...persistence of feelings...[and] primitive techniques" - in effect, qualities that were deemed "feminine." But Schneemann has since said that the text came from a letter sent to a female art critic who found her films hard to watch. By using her physical body as both a site of performance and as the source for a text, Schneemann refused the fetishization of the genitals.

Performed in East Hampton, NY and at the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado

Art/Life: One Year Performance (a.k.a. Rope Piece)

Artist: Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh

For the length of this year long endurance piece, Montano and Hsieh were bound to each other by an 8-foot piece of rope. They existed in the same space, but never touched. In Hsieh's original idea, the rope represented the struggle of humans with one another and their problems with social and physical connection. As the work evolved, the rope took on more meanings. It controlled, yet expanded the patterns of both of the artists' lives, becoming a visual symbol of the relationship between two people. The 365-day length of the work was critical, as it heightened the piece from performance to life. Life and art could not be separated within a work where living was the art. Hsieh explained that if the piece was only one or two weeks, it would be more like a performance, but a year, "has real experience of time and life."

Performed in New York City

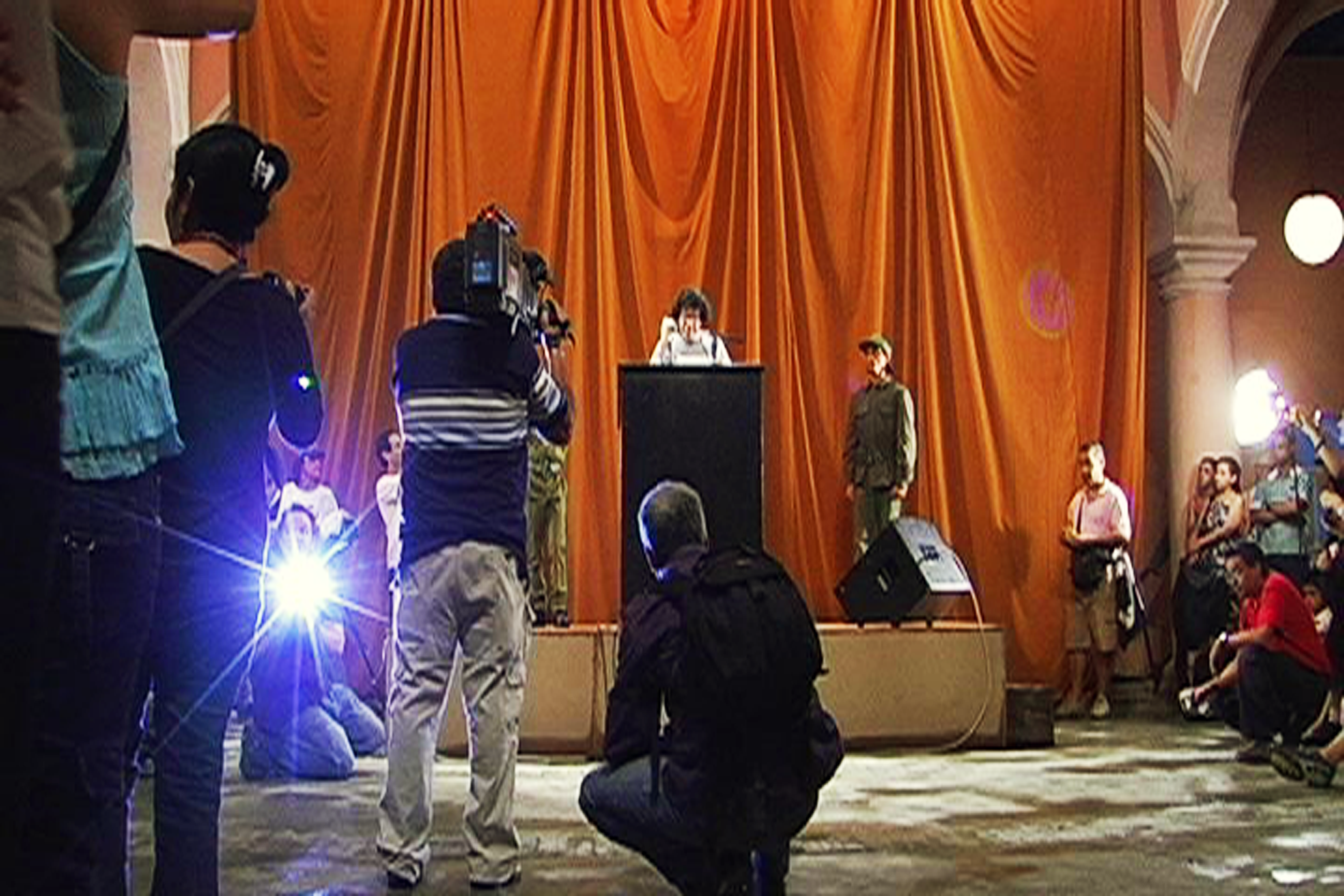

Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Buenos Aires

Artist: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gomez-Pena

Dressed in ridiculous costume, engaged in stereotypical "native" tasks and enclosed in a cage, Fusco and Gomez-Pena addressed the practice of human displays, and fetishization of the "other." Fusco wore several different looks, including hair braids, a grass skirt and a leopard skin bra, while Gomez-Pena sported an Aztec style breastplate. The two ate bananas, performed "native dances" and other "traditional rituals" and were led to the bathroom by museum guards on leashes. The piece was first performed at Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, as a part of the Edge '92 Biennial, which was organized in commemoration of Columbus's voyage to the New World. It was intended as a satirical comedy, yet half of the viewers thought that the fictitious Amerindian specimens were real.

Performed at Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, and performed in various international venues until 1994

Beginnings of Performance Art

Early avant-gardes utilize performance.

20 th century performance art has its roots in early avant-gardes such as Futurism , Dada and Surrealism . Before the Italian Futurists ever exhibited any paintings they held a series of evening performances during which they read their manifestoes. And, similarly, the Dada movement was ushered into existence by a series of events at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. These movements often orchestrated events in theatres that borrowed from the styles and conventions of vaudeville and political rallies. However, they generally did so in order to address themes that were current in the sphere of visual art; for instance, the very humorous performances of the Dada group served to express their distaste for rationalism, a current of thought that had recently surged from the Cubism movement.

Post-war Performance Art

The origins of the post-war performance art movement can be traced to several places. The presence of composer John Cage and dancer Merce Cunningham at North Carolina's Black Mountain College did much to foster performance at this most unconventional art institution. It also inspired Robert Rauschenberg , who would become heavily involved with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cage's teaching in New York also shaped the work of artists such as George Brecht , Yoko Ono , and Allan Kaprow , who formed part of the impetus behind the Fluxus movement and the birth of " happenings ," both of which placed performance at the heart of their activities.

In the late 1950s, performance art in Europe began to develop alongside the work being done in the United States. Still affected by the fallout from World War II, many European artists were frustrated by the apolitical nature of Abstract Expressionism, the prevalent movement of the time. They looked for new styles of art that were bold and challenging. Fluxus provided one important focus for Performance art in Europe, attracting artists such as Joseph Beuys. In the next few years, major European cities such as Amsterdam, Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Paris were the sites of ambitious performance gatherings.

Actionism, Gutai, Art Corporel, and Auto-Destructive Art

Other manifestations included the work of collectives bound together by similar philosophes like the Viennese Actionists , who characterized the movement as "not only a form of art, but above all an existential attitude." The Actionists' work borrowed some ideas from American action painting, but transformed them into a highly ritualistic theatre that sought to challenge the perceived historical amnesia and return to normalcy in a country that had so recently been an ally of Adolph Hitler. The Actionists also protested governmental surveillance and restrictions of movement and speech, and their extreme performances led to their arrest several times.

In France, art corporel , or body art, compiled an avant-garde set of practices that brought body language to the center of artistic practice.

In Japan, the Gutai became the first post-war artistic group to reject traditional art styles and adopt performative immediacy as a rule. They staged large-scale multimedia environments and theatrical productions that focused on the relationship between body and matter.

In Britain, artists such as Gustav Metzger pioneered an approach described as "Auto-Destructive art," in which objects were violently destroyed in public performances that reflected on the Cold War and the threat of nuclear destruction.

The Emergence of Feminist and Performance Art in the U.S.

American Performance art in the 1960s and 1970s coincided with the rise of second-wave feminism. Women artists turned to performance as a confrontational new medium that encouraged the release of frustrations at social injustice and the ownership of discussion about women's sexuality. This permitted rage, lust, and self-expression in art by women, allowing them to speak and be heard as never before. Women performers seized an opportune moment to build performance art for themselves, rather than breaking into other already established, male-dominated forms. They frequently dealt with issues that had not yet been undertaken by their male counterparts, bringing fresh perspectives to art. For example, Hannah Wilke criticized Christianity's traditional suppression of women in Super-t-art (1974), where she represented herself as a female Christ. During and since the beginning of the movement, women have made up a large percentage of performance artists.

The Vietnam War also provided significant material for performance artists during this era. Artists such as Chris Burden and Joseph Beuys , both of whom made work in the early 1970s, rejected US imperialism and questioned political motivations. Performance art also developed a major presence in Latin America, where it played a role in the Neoconcretist movement.

Performance Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Instead of seeking entertainment, the audience for performance art often expects to be challenged and provoked. Viewers may be asked to question their own definitions of art, and not always in a comfortable or pleasant manner. As regards style, many performance artists do not easily fall into any identified stylistic category, and many more still refuse their work to be categorized into any specific sub-style. The movement produced a variety of common and overlapping approaches, which might be identified as actions, Body art, happenings, Endurance art, and ritual. Although all these can be described and generalized, their definitions, like the constituents of performance art as a movement, are continuously evolving. And some artists have made work that falls into different categories. Yves Klein , for instance, staged some performances that relate to the Fluxus movement, and have qualities of rituals and happenings, yet his Anthropometries (1958) also relate to Body art.

The term "action" constitutes one of the earliest styles within modern performance art. In part, it serves to distinguish the performance from traditional forms of entertainment, but it also highlights an aspect of the way performers viewed their activities. Some saw their performances as related to the kind of dramatic encounter between painter and painting that critic Harold Rosenberg talked of in his essay 'The American Action Painters' (1952). Others liked the word action for its open-endedness, its suggestion than any kind of activity could constitute a performance. For example, early conceptual actions by Yoko Ono consisted of a set of proposals that the participant could undertake, such as, "draw an imaginary map...go walking on an actual street according to the map..."

Body Art diffused the veil between artist and artwork by placing the body front and center as actor, medium, performance, and canvas amplifying the idea of authentic first person perspective. In the post-1960's atmosphere of changing social mores and thawed attitudes toward nudity, the body became a perfect tool to make the political personal. Feminist art burgeoned in this realm as artists such as Carolee Schneemann , VALIE EXPORT , and Hannah Wilke turned their bodies into tools for bashing the disconnect between historical portrayals of the female experience and a newly empowered reality. Some artists like Ana Mendieta and Rebecca Horn questioned the body’s relationship to the world at large, including its limitations. Other artists, like Marina Abramović, Chris Burden and Gina Pane, performed shocking acts of violence toward their own bodies, which provoked audiences to question their own participation, in all its permutations, as voyeurs.

Happenings were a popular mode of performance that arose in the 1960s, and which took place in all kinds of unconventional venues. Heavily influenced by Dada, they required a more active participation from viewers/spectators, and were often characterized by an improvisational attitude. While certain aspects of the performance were generally planned, the transitory and improvisational nature of the event attempted to stimulate a critical consciousness in the viewer and to challenge the notion that art must reside in a static object.

A number of prominent performance artists have made endurance an important part of their practice. They may involve themselves in rituals that border on torture or abuse, yet the purpose is less to test what the artist can survive than to explore such issues as human tenacity, determination, and patience. Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh has been one important exponent of this approach; Marina Abramović offers other examples. Allan Kaprow was perhaps the most influential figure in the happenings movement, though others who were involved include Claes Oldenburg , who would later be associated with Pop art .

Ritual has often been an important part of some performance artists' work. For example, Marina Abramović has used ritual in much of her work, making her performances seem quasi-religious. This demonstrates that while some aspects of the performance art movement have been aimed at demystifying art, bringing it closer to the realms of everyday life, some elements in the movement have sought to use it as a vehicle for re -mystifying art, returning to it some sense of the sacred that art has lost in modern times.

Later Developments - After Performance Art

After the success performance art experienced in the 1970s, it seemed that this new and exciting movement would continue in popularity. However, the market boom of the 1980s, and the return of painting, represented a significant challenge. Galleries and collectors now wanted something material that could be physically bought and sold. As a result, performance fell from favor, but it did not disappear entirely. Indeed, the American performer Laurie Anderson rose to considerable prominence in this period with dramatic stage shows that engaged new media and directly addressed the period's changing issues.

Women performance artists were particularly unwilling to give up their newfound forms of expression, and continued to be prolific. In 1980, there was enough material to produce the exhibition A Decade of Women's Performance Art , at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. Organized by Mary Jane Jacob, Moira Roth, and Lucy R. Lippard, the exhibition was a broad survey of works done in the United States during the 1970s, and included documentations of performances in photographs and texts.

And in Eastern Europe throughout the 1980s, performance art was frequently used to express social dissent.

Moving into the 1990s, Western countries began to embrace multiculturalism, helping to propel Latin American performance artists to new fame. Guillermo Gomez-Pena and Tania Bruguera were two such artists who took advantage of the new possibilities afforded by large biennials with international reach, and they presented work about oppression, poverty, and immigration in Cuba and Mexico. In 1991 and 1992, Next Wave festivals at the Brooklyn Academy of Music reflected these trends with works from the American-Indian group Spider Woman Theater, Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, and Urban Bush Women dance company.

Performance art is a movement that thrives in moments of social strife and political unrest. At the beginning of the 1990s, performance art once again grew in popularity, this time fueled by new artists and audiences; issues of race, immigration, queer identities, and the AIDS crisis began to be addressed. However, this work often caused controversy, indeed it came to be at the center of the so-called Culture Wars of the 1990s, when artists Karen Finley , Tim Miller , John Fleck and Holly Hughes passed a peer review board to receive funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, only to have it withdrawn by the NEA on the basis of its content, which related to sexuality.

Today's performance artists continue to employ a wide variety of mediums and styles, from installation to painting and sculpture. British artist Tris Vonna-Michell mixes narrative, performance and installation. Tino Sehgal blends ideas borrowed from dance and politics in performances that sometimes take the form of conversations engaged in by the audience themselves; no conventional staged performance takes place, and no documentation remains of the events. Sehgal's solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2010 is a sign of how close the genre has now come to being accepted by mainstream art institutions.

Useful Resources on Performance Art

- Performance Art: From Futurism to Present Our Pick By Roselee Goldberg

- Performance: Live Art Since the '60s Our Pick By Roselee Goldberg, Laurie Anderson

- Body Art/Performing the Subject By Amelia Jones

- The Amazing Decade: Women and Performance Art in America, 1970-1980 By Moira Roth

- Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas By Coco Fusco

- Performance Art in China By Thomas Berghuis

- Performa 11 - Visual Art Performance Biennial Information on previous 2011 exhibition, and future events

- In the Naked Museum: Talking, Thinking, Encountering By Holland Cotter / The New York Times / January 31, 2010

- Marina Abramović: An Interview By David Ebony / Art in America / May 5, 2009

- Performance Art Gets Its Biennial By Roberta Smith / The New York Times / November 4, 2005

- Preserve Performance Art? Can You Preserve the Wind? By John Rockwell / The New York Times / April 30, 2004

- Marina Abramović: Live at MoMA

- The Couple in the Cage by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gomez-Pena

- The Act: A Performance Art Journal (Archive)

- Live Action Goteborg: International Performance Art Festival

- Hemispheric Instutute of Performance and Politics

- UbuWeb: Film & Video Our Pick Extensive Database for Videos of Performance Art

Similar Art

Reciting the Sound Poem "Karawane" (1916)

Yard (1961)

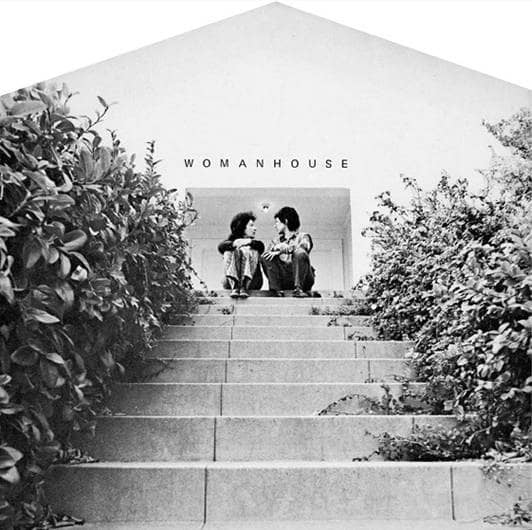

Womanhouse (1972)

Related artists, related movements & topics.

Content compiled and written by Anne Marie Butler

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

- Corrections

What Is Performance Art and Why Does It Matter?

Performance art might be one of the most radical art forms in existence, ranging from extreme endurance tests to acts of political protest.

Of all the art forms that exist in the contemporary world, performance art must surely be one of the most daring, subversive and experimental. From covering naked bodies in paint and wrestling with a wild coyote, to hiding under the floorboards of the gallery or rolling in raw meat , performance artists have pushed the boundaries of acceptability, and tested the breadth of human endurance, challenging us to ask questions about the nature of art, and our bodily relationship with it. We look through some of the key ideas around performance art, and the reasons why it matters so much today.

1. Performance Art Focuses on Live Events

Performance art is undoubtedly a broad ranging and diverse style of art that involves some kind of acted out event. Some performance art is a live experience that can only happen in front of an active audience, such as Marina Abramovic ’s hugely controversial Rhythm 0, 1974, in which she laid out a series of objects and asked audience members to inflict harm on her body. Other artists record their performances, suspending them forever in time, such as Paul McCarthy ’s Painter, 1995, in which the artist acts out the exaggerated role of an expressionist painter in a mock-studio, while wearing prosthetic body parts. Both artists, in different ways, challenge us to think about the body’s relationship to the work of art.

2. Performance Art Is One of the Most Radical Art Forms

From its earliest days, performance art has been one of the most radical and boundary-pushing art forms. The history of performance art is often traced back to Dadaism and Futurism in early 20 th century Europe, when artists began staging anarchic, violent performances aimed at shocking audiences awake in the aftermath of war. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that performance art became recognized as an artform in its own right.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Black Mountain College in North Carolina is widely recognized as the birthplace of performance art. Led by the revolutionary musician John Cage , teachers and students collaborated on a series of multi-disciplinary events merging music, dance, painting, poetry and more into a singular whole, expanding their practices in new and unprecedented ways through acts of playful collaboration. They called these experimental events ‘Happenings’, and they gave rise to performance art throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

3. Performance Art Has Close Ties with Feminism

During the 1960s Performance art was a particularly popular artform amongst Feminist artists, including Carolee Schneemann , Yoko Ono , Hannah Wilke, Linda Montano and Tehching Hsieh. For many Feminist artists, performance art was a chance to reclaim their bodies from centuries of male objectification, and to express their rage and frustration at systems of oppression. For example, in Gestures, 1974, Wilke pushes, pulls and stretches the skin on her face, reclaiming her skin as her own playground.

4. It Breaks Down Barriers Between Art Forms

Performance art is one of the more inclusive art forms, inviting multi-disciplinary ways of making art, and encouraging artists from different disciplines to collaborate. Acts of cross-pollination and sharing of ideas have opened up a whole new wealth of creative possibilities, as seen in Marvin Gaye Chetwynd ’s lavish and all-encompassing events that merge the spectacle of theatre and costume with sculpture and dance.

Some artists also invite the audience to play an active role in the performance, such as Dan Graham’s Performer, Audience, Mirror, 1975, in which he recorded himself performing in front of a mirror, while being watched by a captive crowd.

5. It Tests Human Endurance

One of the most fascinating, yet disturbing aspects of performance art is when artists push their bodies into extreme life or death situations, testing the strength of human endurance. Joseph Beuys played with danger in his legendary 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me , by closing himself in a gallery for three days with a wild coyote. Here the coyote became a symbol for the wild, pre-colonial terrain of America, which Beuys argued is still an untamable force of nature. Beuys protected himself against the coyote by wrapping his body in a felt blanket and holding a hooked cane.

6. It Is Often a Form of Political Protest

Many artists have blurred the boundaries between performance art and political protest, staging controversial events that stir up uncomfortable truths about the climate in which they are living. One of the most high-profile, politicized acts of performance art was Pussy Riot ‘s Punk Prayer, 2012. Three members of the group performed a “Punk Prayer” in Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow, criticizing the oppressive nature of Russian authorities and their dubious links with the Catholic church, while wearing their trademark brightly colored clothes and balaclavas. Although Russian authorities arrested and imprisoned the artists, their influence on artist-activists has been profound, demonstrating how performance art can be a powerful tool of self-expression during the most challenging of times.

Yves Klein and His Use of Blue: How These 5 Facts Made Him Famous

By Rosie Lesso MA Contemporary Art Theory, BA Fine Art Rosie is a contributing writer and artist based in Scotland. She has produced writing for a wide range of arts organizations including Tate Modern, The National Galleries of Scotland, Art Monthly, and Scottish Art News, with a focus on modern and contemporary art. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from the University of Edinburgh and a BA in Fine Art from Edinburgh College of Art. Previously she has worked in both curatorial and educational roles, discovering how stories and history can really enrich our experience of art.

Frequently Read Together

Who Was Carolee Schneemann? 8 Facts About the Legendary Performance Artist

Rhythm 0: A Scandalous Performance by Marina Abramović

What Is Contemporary Art?

Performance art

Performance art differs from traditional theater in its rejection of a clear narrative, use of random or chance-based structures, and direct appeal to the audience.

c. 1960 - present

videos + essays

We're adding new content all the time!

Raphael Montañez Ortiz, Duncan Terrace Piano Destruction Concert: The Landesmans’ Homage to “Spring can really hang you up the most”

What makes a destroyed piano a work of art?

Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was a highly influential school founded in North Carolina, USA, in 1933 where teaching was experimental and committed to an interdisciplinary approach

Shiraga Kazuo, Challenging Mud (Doro ni idomu)

A single dramatic overhead shot captures the artist covered in a viscous mud, struggling to free his left leg from the thickly piled muck atop which he lies.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting

Gordon Matta-Clark’s interventions explored modernist architecture and urban decay.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside (July 23, 1973)

The artist asks us if maintaining can be as important as creating.

The Case for Performance Art

Inserting live bodies into artworks unsettles the delusion that a universal perspective exists.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present

Is staring into the eyes of one of the world’s most renowned performance artists scary? Transcendent? Boring?

Vito Acconci, Following Piece

In this stalkery piece, Acconci questions space, time, and the human body on the streets of New York.

Performance art, an introduction

What happens when art intersects with life?

Selected Contributors

Dr. Virginia B. Spivey

Rebecca Taylor

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

12 Performance Art

An art of action.

This chapter focuses on performance from the 1960s to today. Like their avant-garde predecessors, discussed in the Introduction to New Media Art chapter, the performance artists examined here create work that redefines traditional art-making practices. Frequently relying on direct audience interaction and participation, modern and contemporary performance artists explore the body, examine process, and further break down boundaries between art and life. Performance, as we’ll see, is also time-based and ephemeral, often captured and made “permanent” through photography, film, and video. After watching and reading some background information, the examples throughout this chapter are presented as thematic case studies.

Watch & Consider: The Case for Performance Art

For a brief historical overview discussing the significance of performance art, please watch the primer, embedded below, from PBS Studio’s The Art Assignment, “ The Case for Performance Art ” (9:09 minutes).

Read & Reflect: Performance Art

The reading from Smarthistory, linked to below, focuses on how performance artists seek to locate new forms of expression as alternatives to traditional media. It also discussed the importance of the viewer and places performance in historical context.

- “ Performance Art: An Introduction ” (Smarthistory)

The Basics: What is Performance Art?

As we’ve seen in previous chapters, non-traditional art-making materials and methods, like dance and music, have been used by artists since the early 20th century. In fact, performance art has its roots in early 20th century avant-garde movements such as Dada and Futurism . Dada performances, such as Hugo Ball’s (1866-1927) recitation of Karawane at the Cabaret-Voltaire, demonstrate an interest in incorporating non-traditional art-making materials and methods into performance art, as well as the enduring quality of ephemerality .

Italian Futurists also used performance to express their dissatisfaction with the status quo, staging disruptive performances called serata , which reconfigured the artist as a confrontational performer in the public sphere. These evenings incited audience participation and interaction, often even ending in brawls.

Despite their extreme ideological differences, both Dada and Futurist artists were concerned with making art that interacted, at times viscerally, with life, rather than in creating a lasting art object removed from the messiness of living, meant for veneration on a museum’s walls. We can still see the influence of these movements in performance today.

In the United States, performance art emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, against the backdrop of war (in Korea and Vietnam), developing social and racial justice movements for civil rights and equality, and technological advancements, such as the television.

Using their body as medium, performance artists question the definition of art, explore the role of art in society, and critique how art is valued. Through the often intermedia qualities of their works, performance artists also consider how traditional concepts of art (e.g., painting or sculpture) can be given renewed relevance through new technologies.

Perhaps because it confronts the viewer, takes place in real time, and uses the artist’s own body as medium, performance has, historically, occupied a less privileged place in art history than conventional media. As you review the works featured in this chapter, watch for instances of intermedia , a critical cross-disciplinary strategy of New Media artists that encourages mixing materials and embraces new technologies.

A Two-Way Exchange: Audience & Performance Art

As mentioned above, performance artists are interested in breaking down boundaries between art and life, creating a new context for a work of art. What barriers exist between art and life? First, think of where you would traditionally view a work of art. You might have thought about the museum or gallery space as a primary venue for seeing art. While performance can (and does) exist in the museum or gallery space, historically performance artists sought to present work outside of traditional art-viewing venues. They did this both to engage more directly with the viewer in the public space and to separate their work from the value systems imposed by the art world.

Performance artists also blur the boundaries between art and life by using everyday, or non-art, materials in their works. In this chapter, you’ll examine performances by artists who use meat, dirt, snow, and their own clothes, among other non-art materials, in their works.

We’ve already learned about Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) in the context of Dada. Duchamp argued that both the artist and the viewer are necessary to complete a work of art. In “ The Creative Act ” (1957), Duchamp said, “All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

Let’s think about this quote for a minute. How do you interpret Duchamp’s statement? You might consider how Duchamp’s words attempt to dissolve the distance between artist and viewer, or spectator. If the viewer is responsible for bringing “the work in contact with the external world” then they are necessary to complete the work of art. This helps equalize the relationship between artist and audience and encourages a more active role for the viewer.

Questions to Consider: Performance Art

As we move through the examples presented in this chapter, let’s consider the following questions:

- How does performance continue to shift the relationship between artist and viewer? Can you think of ways performance helps reinvent this relationship?

- How does soliciting active involvement from the viewer challenge their historically more passive role? How does direct viewer participation break down traditional or conventional barriers between artists, the artwork, and the viewer?

- Finally, when artists engage and collaborate with audiences to create or complete a work of art, do you think it’s hard for them to relinquish some control over the work’s outcome? Why or why not?

Additionally, throughout the chapter, look for examples where artists:

- Perform and present work outside the traditional venues (e.g., museums or galleries),

- Engage the audience directly, or

- Use everyday (non-art) materials.

These terms are presented in bold throughout the chapter. When you encounter one, be sure to note the definition. You may see these terms used elsewhere in the textbook; here they are discussed in the context of performance art, specifically.

- Behavior Art (associated with Tania Bruguera)

- Collaboration

- Conceptual Art

- Durational Performance

- Happenings (associated with Allan Kaprow)

- Kinetic Theater

- Participatory

- Performalist Self-Portraits (associated with Hannah Wilke)

- Social Body

- Street Action (associated with David Hammons)

Performance Artists & Artworks

As we’ll see through the example discussed in this chapter, performance art is diverse and often interdisciplinary. As you review each work, keep in mind that performance is defined by an individual work of art, rather than by an artist’s entire career. In other words, someone who sculpts or paints can also create a performance, and an artist who makes a performance can also be a sculptor. What these pieces have in common is that they are centered on an action carried out, or arranged, by an artist. They are also time-based and ephemeral, rather than permanent artistic gesture with a specific beginning and an end. Since we are viewing these works now as photographs or videos, you can see how documentation of the performance might live on forever, but the performance itself is a fleeting moment in time.

Focus: 1960s: The Impact of Fluxus

The early examples of performance discussed in this first section are connected to Fluxus . As you learned in the introduction , Fluxus is an international art movement led by George Maciunas (1931-1978) that emphasizes chance, the unity of art and life, and the ephemeral moment. Without a single defining style, Fluxus sought to democratize art and art-making by creating event scores to be enacted by anyone. An event refers to a Fluxus performance, while a score is the set of directions the Fluxus performer follows and interprets. Fluxus events were anti-commercial as they were not intended to result in an object that could be purchased or collected. Collaboration and intermedia methods were encouraged in order to create art that was directly participatory .

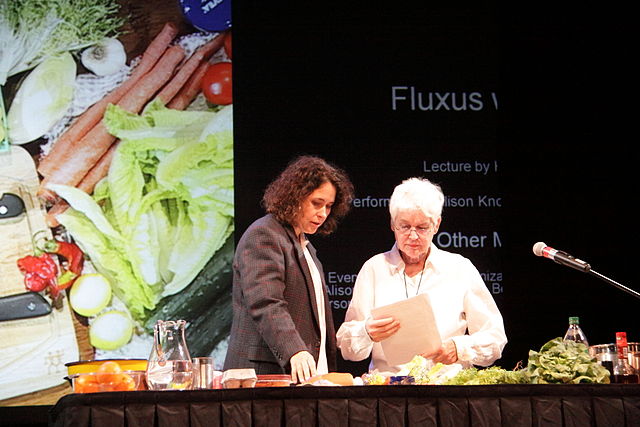

While all four artists discussed in this section, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, Alison Knowles, and Benjamin Patterson, have a connection to Fluxus early in their careers, Ono and Schneemann distanced themselves from the movement (Schneemann after Meat Joy , specifically).

Elements of New Media Art

As you review the examples discussed below, think about how each illustrates specific qualities of a Fluxus art. Also, consider how performance in general connects to New Media art. You might reflect on how performance:

- Dismantles the boundaries between art and life.

- Employs chance .

- Engages the viewer as a participant .

- Focuses on the process or the act of creating, not the outcome.

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece , 1964

The Japanese artist Yoko Ono (born 1933) debuted Cut Piece in Kyoto, Japan, in 1964, and has since performed it in Tokyo, New York, London, and Paris. The performance is the realization of a score, or a set of participatory instructions that result in the creation of the Fluxus event. A member of the Fluxus movement, Yoko Ono’s work challenges the viewer to become an active participant in the performance by asking them to cut off pieces of her clothing, as she sits motionless on the stage.

Read Yoko Ono’s score for Cut Piece :

“Cut Piece First version for single performer: Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage—one at a time—to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. Piece ends at the performer’s option.”

In a second version, Ono amended the instructions slightly, indicating that, “members of the audience may cut each other’s clothing. The audience may cut as long as they wish.”

(The above score is excerpted from MoMA’s website , quoted from Kevin Concannon, “Yoko Ono’s CUT PIECE: From Text to Performance and Back Again,” Imagine Peace .)

Watch & Reflect: Cut Piece

Watch this excerpt from Yoko Ono’s performance of Cut Piece:

Questions to Consider:

- What do you notice about the performance? Where is the artist? Where is the audience? What role does the audience assume in this work? How is Yoko Ono’s score reflected in the actions of the performance?

- Read this excerpt from a MoMA audio guide where Ono reflects on her experience performing Cut Piece .

- How does Ono’s piece reflect Fluxus ideology?

- After learning more about Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece , how do you think you would have experienced her work as a viewer? Would you have participated in the event? Why or why not?

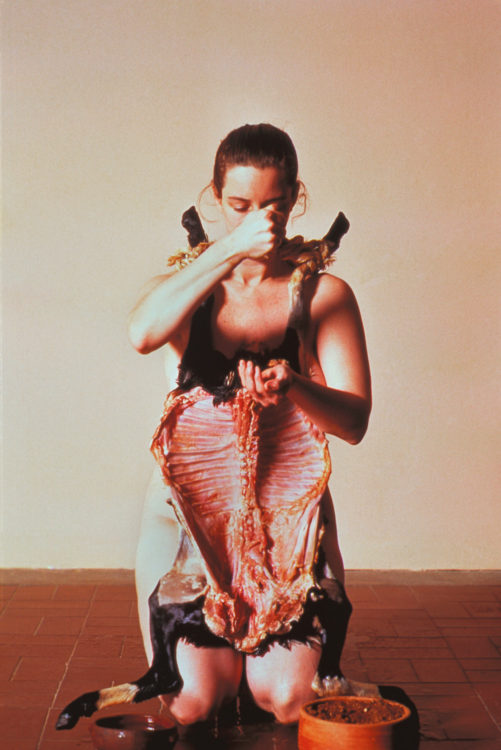

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy , 1964 (re-edited 2010)

Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) was an American multidisciplinary artist and an incredibly important figure in performance and feminist art. She is known for her explorations of gender, sexuality, and sexism in art history, through work that encompasses painting, performance, film, installation, and video art.

In Meat Joy , a group of dancers (including Schneemann) wear feather-lined bikinis and briefs, as they move in both choreographed and spontaneous ways atop a plastic sheet. They rub raw fish, chicken, and sausages over their bodies, and cover themselves in wet paint and scraps of paper. The result is a tactile experience and an honoring of flesh in many forms. Though not directly participatory, the audience could see the movement and hear the sounds of the dancer’s bodies, and smell the mixing of meat, paper, and paint. Later, Schneemann pieced together bits of footage from various performances of Meat Joy and set it to music with a voice-over, adding yet another sensory layer.

In More Than Meat Joy , Schneenmann writes of the performance:

The focus is never on the self, but on the materials, gestures & actions which involve us. Sense that we become what we see, what we touch. A certain tenderness (empathy) is pervasive – even to the most violent actions: say, cutting, chopping, throwing chickens. (Schneemann, 253).

Schneemann referred to her work as kinetic theater because it creates “an immediate, sensuous environment on which a shifting scale of tactile, plastic, physical encounters can be realized. The nature of these encounters exposes and frees us from a range of aesthetic and cultural conventions” (Youngblood, 366). As Schneemann describes, kinetic theater fosters an intermedia experience between dance and performance where touch and physicality are explored and celebrated in various forms. Kinetic theater relates to Fluxus because of the way the body is staged in a social space. Even though this performance is not directly participatory, we can consider the ways in which it embraces the use of everyday, non-art materials and creates a sense of immediacy and intimacy.

After viewing Meat Joy and reading Schneemann’s statement about her work, consider its historical context. First performed in Paris in 1964, and then later that same year in London and New York, we might think about Schneemann’s performance as an act of resistance. In 1964, the Vietnam War is raging and Black Americans, women, and people with disabilities are fighting for equal rights (the Civil Rights Act has only just been signed into law in 1964). By choreographing a piece that openly and publicly explores the body as a site for both sensuality and violence, Schneemann creates a performance that transgresses societal norms.

Stop & Reflect: Meat Joy

Watch Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy , 1964 (re-edited 2010), filmed performance, 10:33 minutes, color, sound, 16 mm film on video (you will have to click through to view on YouTube). You can also listen to Carolee Schneemann discuss the sensuality of Meat Joy (2:00 minutes).

- What materials does Meat Joy use? How is this work an example of an intermedia approach?

- Can you think of ways Schneemann’s performance rejects the traditional “dismissive” approach to female sexuality prevalent in western art history?

Alison Knowles, Make a Salad , 1962

Alison Knowles (born 1933) is an American artist and a founding member of Fluxus. She is known for her use of ordinary, non-art materials, and scores that celebrate the everyday. In Make a Salad the participants are instructed via a Fluxus score to….make a salad! The process of making the salad, from selecting the ingredients, to mixing in the dressing, to serving it, will vary. The salad you make will be your salad and will be entirely dependent on what you have on hand and how you interpret the score.

The piece also has a vital auditory component: close your eyes and imagine the noise made by the chopping of vegetables and the rustling of lettuce leaves. What sound does the bowl make as you mix your ingredients together? What about when you bite down on a piece of lettuce or a cucumber? This is considered music, as if one was listening to actual instruments performing a symphony. This idea of the “in-between” moments of everyday life being as important as a set of carefully composed notes has its roots in the scores of the American avant-garde composer John Cage (1912-1992), whose work inspired many Fluxus artists, though he was never a member of the group.

Stop & Reflect: Make a Salad

First, to see this work and the process in action, watch Alison Knowles – ‘I’m Making a Giant Salad’ | TateShots about Knowles’ 2008 event at the Tate in London (3:47 minutes):

Then, for additional context, watch this video of Knowles discussing Fluxus more broadly, Alison Knowles: Fluxus Event Scores (2:57 minutes):

- How does Knowles involve the viewer as participants in her event?

- In 2008, Knowles performed this piece in front of a large audience at the Tate; how would this work be different if you performed it at home? How would it remain the same?

- What other everyday moments could be celebrated through a score? What would you perform?

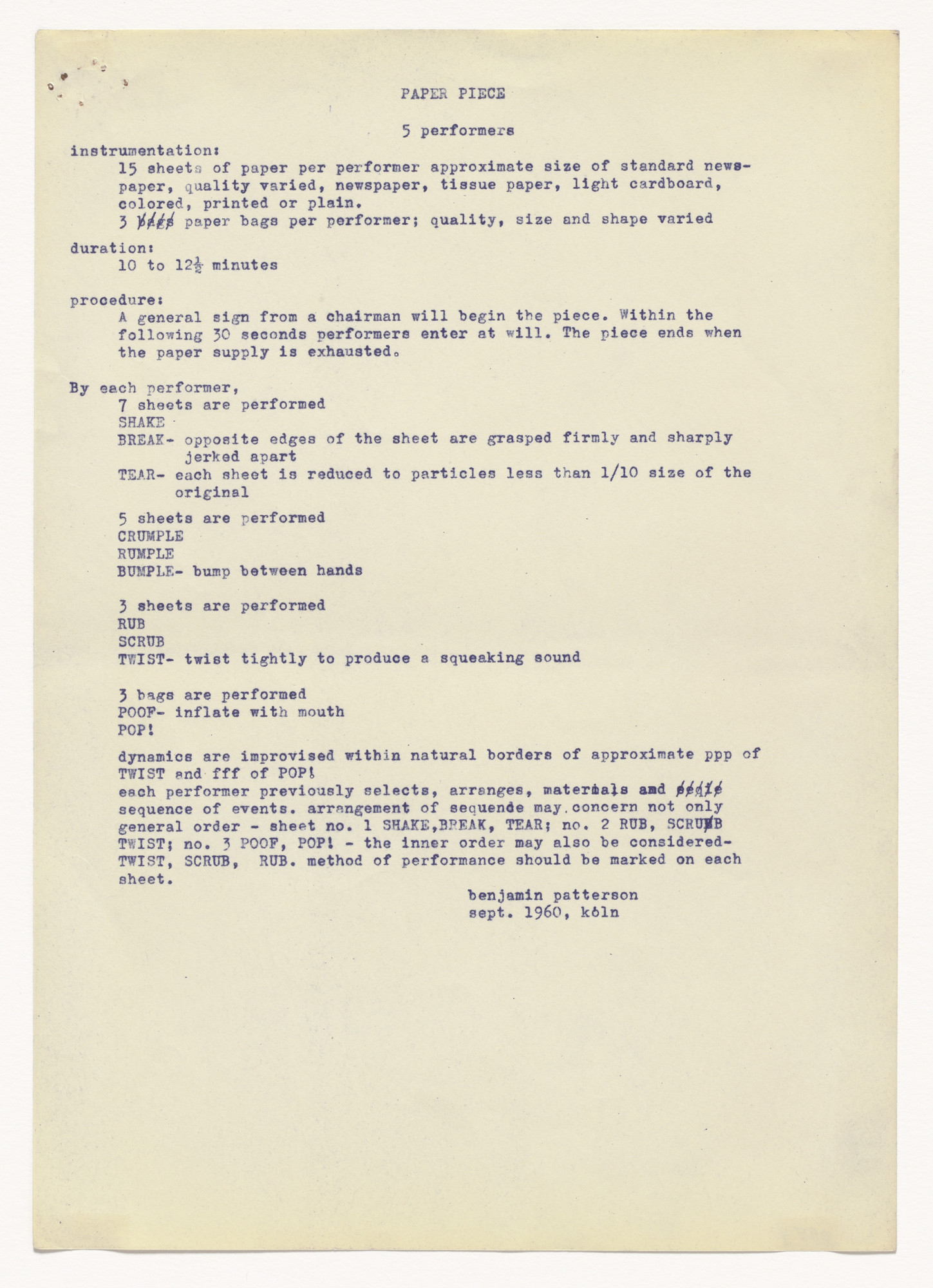

Benjamin Patterson, Paper Piece , 1960

A founding member of Fluxus, Benjamin Patterson (1934-2016) was a classically trained double bassist who connected his experimental musical scores with audience participation to create what he called compositions for actions . Interested in the democratization of art and music, Patterson’s focus on indeterminacy was influenced by a meeting (and, later, a performance) with John Cage in 1960, while both composers were in Cologne, Germany. The first version of Patterson’s Paper Piece , was actually part of letter he mailed home to his parent a Christmas present to them, since he wouldn’t be home to celebrate.

A joyful celebration of everyday movements and sound, Paper Piece asked the audience to “crumple,” “rumple,” and “bumple” sheets of paper. See the video below of the Ensemble for Experimental Music and Theatre performing Patterson’s score in 2013 (YouTube, 9:58 minutes):

Stop & Reflect: Fluxus

- What are some ways you would describe a Fluxus Event Score?

- What are some differences between attending a traditional play in a theater vs. participating in a Fluxus Event Score?

- In what ways do Fluxus Event Scores challenge traditional ways of viewing art in a gallery?

- How do Event Scores expand what it means to be an audience member or viewer?

- How do Event Scores pieces expand what it means to be an artist?

- In what ways does Fluxus blur the lines between art and life? Fluxus Event Scores are different than other approaches to Performance Art discussed below. Consider some of these differences as you continue to work through this chapter.

Focus: 1970s: Body Art

Optional Video: Can My Body be Art? How Art Became Active (Tate, 4:05 minutes)

Body Art is a type of performance that developed in the 1960s and 1970s. As its name implies, Body Art uses the body, usually but not always the artist’s, as a basis for the artwork. Endurance is often central to Body Art, such in the examples by Chris Burden and Hannah Wilke discussed below. Body Art can also negotiate issues of identity, gender, and sexuality. Ana Mendieta’s work, for example, explores feelings of displacement related to her identity as an exiled Cuban artist living in the United States. It’s important to note that Carolee Schneemann’s work, discussed in the previous section, is also considered Body Art; remember that, especially in New Media, boundaries are fluid and artworks will belong to more than one category.

Chris Burden, Shoot , 1971

The American artist, Chris Burden (1946-2015), performed Shoot at a Santa Ana, CA gallery called F Spot in 1971; the artist was 25 years old. Standing in front of a small audience of mostly friends, Burden’s friend shot him with a .22 long rifle from a distance of 13 feet. The bullet, meant to graze Burden’s arm, actually hit him, causing the artist to be taken to the hospital. You can see still images from the performance at Media Art Net .

This work is an example of Body Art. As discussed above, Body Art is a type of performance that explicitly uses the body, often pushed to its extremes, to address the relationship of the body to society. Shoot , like many examples of Body Art is transgressive, meaning it pushes the boundaries of what’s comfortable or acceptable (this also applies to Meat Joy ). In Burden’s work, he engages in an acute action in order to shock the viewers, forcing them into an immediate, emotional response.

Staged when the United States was embroiled in the controversial Vietnam War (1955-1975), Burden’s performance can be interpreted as a way to process images of violence seen by many on the nightly news during this “televised” war.

Stop & Reflect: Shoot

Watch: “ Shot in the Name of Art ” (Op Docs, the New York Times via YouTube, 4:39 minutes) Content Warning: A person being shot with a gun.

- How does Shoot comment on the public’s growing desensitization to violence?

- Does the viewer of a violent act become complicit in the artist putting his body at risk?

- Can you compare and contrast Burden’s use of his body with one other artist discussed in this chapter?

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) , 1974

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) , 1974, performance on video (1:20 minutes); clip is 1:13. See a video still and read about Mendieta’s performance at the Reina Sophia Museum website .

Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) was a Cuban-born cross-disciplinary artist living in exile in the United States. Forced to leave Cuba when she was just 12 years old, due to her father’s involvement with a counterrevolutionary group, Mendieta and her sister were separated from her mother and younger brother, and sent to live in Iowa via Operation Pedro Pan . She would not reunite with her whole family for another 18 years.

In much of her practice, Mendieta used her body to address a sense of dislocation and express the trauma of violence against women. In Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) we watch as the artist, dressed in white and cream, approaches a white wall. She raises her arms, placing them against the wall. She then begins to kneel, slowly dragging her arms down the wall. Mendieta rises and walks out of the frame, leaving behind two red lines, marks made by her forearms, which were covered with animal blood.

The lines create a shape reminiscent of a tree trunk and serve as a reminder of the ephemerality of the artist’s body, which is no longer present. Untitled (Blood Sign #2/Body Tracks) also ties into Mendieta’s Silueta series (1973-1978) in which the artist photographs and films her body, both its presence and absence, in nature.

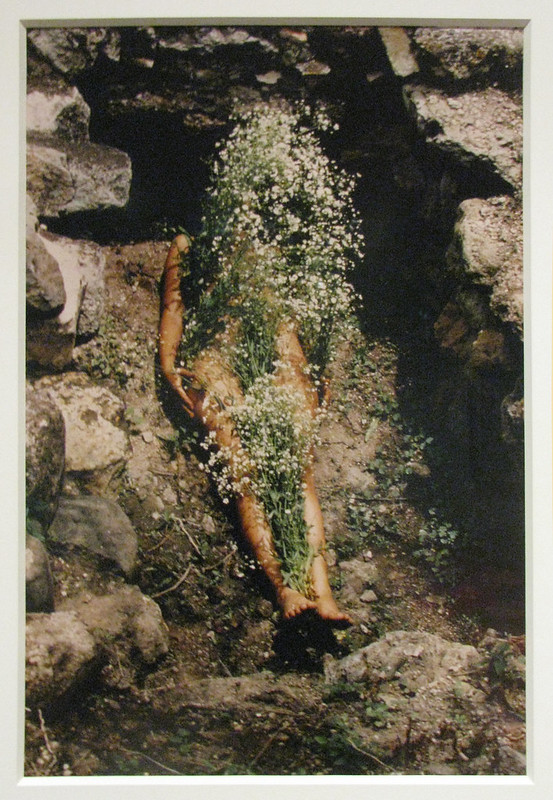

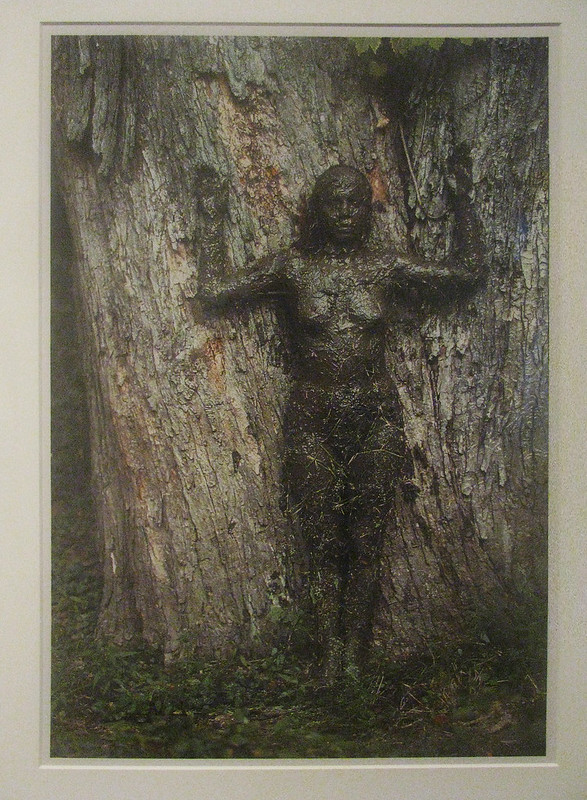

Ana Mendieta, Silueta , 1973-1978

Mendieta began work on the Silueta series in 1973 while on a trip to Oaxaca, Mexico, with her classmates in the Intermedia program at the University of Iowa and their instructor, Hans Breder. Mendieta was fascinated by Mexico, in part because the country reminded her of Cuba, and she continued the series when she returned to Iowa. The photographs and films she took serve to document her performances in the land and are a type of performance that Mendieta called earth-body works. These works align Mendieta with both performance, land, and feminist art.

In one Silueta , pictured above, we see a photograph of Mendieta laying naked in a Zapotec tomb. White flowers lay over her body, obscuring it. The flowers seem to grow from her, connecting her visually and symbolically with the land. We might think of the cycles of life and death when examining Mendieta’s work. Since she was uprooted from her home in Cuba as a child, many art historians interpret her Silueta series as seeking to re-root the body in place.

In The Tree of Life , pictured below, Mendieta covered herself completely with mud, fully incorporating her body into the landscape, her form making a raised impression against a tree. Making her body part of the earth, and allowing the There is a sense of intimacy in the scale of Mendieta’s performances; highlighted by the relationship between the artist’s body, the land, and the viewer.

Mendieta went on to create more than one hundred Silueta in Mexico, Iowa, and Cuba (where she returned to visit in 1981) covering her body with a wide range of substances, including rocks, blood, sticks, sand, and cloth. Or, she’d make an impression right in the earth, letting it fill up with water or sometimes red pigment. There is a relationship between Mendieta’s series and Santería , which is an African diasporas religion a commonly practiced in Cuba. Santería’s use of natural symbols, such as earth, blood, water, and fire, are echoed in Mendieta’s practice.

Through her performances, Mendieta is considered important to feminist art history. Like other women discussed in this chapter, Mendieta controls the presentation of her own body, taking an active role in how the viewer sees her (or doesn’t). She also takes a non-invasive approach to the land, rather than altering it, she becomes a part of it by gently and temporarily transforming it through her presence. Finally, Mendieta’s work mediates feelings of displacement and indeterminacy; this sense of ephemerality and vulnerability arguably helps her work transcend her individual identity and biography by questioning the physical experience of being a part of the world.

In Her Own Words: Ana Mendieta’s Artist Statement

Artists write statements to describe their work and their interests. Read Mendieta’s statements below to better understand her aims. (Excerpts are from Olga Viso, Unseen Mendieta: The Unpublished Works of Ana Mendieta , Munich, Berlin, London and New York 2008.)

“The first part of my life was spent in Cuba, where a mixture of Spanish and African culture makes up the heritage of the people. The Roman Catholic Church and “Santeria”—a cult of the African divinities represented with the Catholic saints and magical powers—are the prevalent religions of the nation. For the past five years, I have been working out in nature, exploring the relationship between myself, the earth, and art. Using my body as a reference in the creation of the works, I am able to transcend myself in a voluntary submersion and total identification with nature. Through my art, I want to express the immediacy of life and the eternity of nature.” (Ana Mendieta, 1978)

“I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures I become one with the earth … I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body. This obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is really the reactivation of primeval beliefs … [in] an omnipresent female force, the after-image of being encompassed within the womb.” (Ana Mendieta, 1981)

“For the last twelve years, I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body. Having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence, I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast out from the womb (Nature). My art is the way I reestablish the bonds that unite me to the Universe. It is a return to the maternal source. These obsessive acts of reasserting my ties with the earth are really a manifestation of my thirst for being. In essence, my works are the reactivation of primeval beliefs at work within the human psyche.” (Ana Mendieta, 1983)

Stop & Reflect: Ana Mendieta

- How do you think Mendieta’s exile from Cuba influenced her artwork? How are feelings of displacement and dislocation explored in her works?

- What aspects of home resonate with you on a sensory level?

- What materials does Mendieta use to create her work?

- Can you describe the role of the body in her artwork?

- How are life and nature intertwined in Mendieta’s work?

- How do the works in the Silueta series suggest the fragility of the human being in relation to the forces of nature?

Hannah Wilke, Gestures , 1974

Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) was an American artist whose intermedia works combined performance, film, sculpture, painting, and photography. Gestures is a recorded, durational performance that shows the artist manipulating her face with her hands for the length of the video (about 35 minutes). She pushes, pinches, smooshes, and pulls at her face, stretching and contorting it like clay, a material she often worked with before creating her first video work. These gestures ask the viewer to question standards of conventional beauty. Referring to these explorations as performalist self-portraits , Wilke used her body to play with ideas of abstraction and representation, and to call attention to how women’s bodies are objectified.

Using her hands, her face transforms, interrupting the viewer’s gaze, and calling attention to the commodification of the female body. Wilke, like Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann, and Ana Mendieta, uses her own body in an effort to reclaim it and define it herself, within a patriarchal society. She says, “I made myself into a work of art. That gave me back my control as well as dignity.” (Wilke, quoted in Montano, p. 139).(You can read more about Gestures in the Early Video Art chapter.)

Stop & Reflect: Hannah Wilke

Hannah Wilke, Gestures, 1974, video (black and white, sound), 35:30 minutes. (Excerpt included below is just 0:58.)

- Wilke’s work addresses female objectification through the exploration and transformation of her own face and body. Why do you think self-representation is important to Wilke?

- How does Gestures compare to Schneemann and Mendieta’s use of their bodies in examples examined earlier in this chapter?

Focus: 1980s: Ritual Space

The artists presented in this section create space for performance outside the traditional museum or gallery setting. Allan Kaprow and Tehching Hsieh explore patience and time through their durational performances , while David Hammons reclaims space for Black bodies through his ephemeral performances.

Allan Kaprow, Trading Dirt , 1982/83-1985

An early practitioner of participatory art, Allan Kaprow (1927-2006) valued the performative possibilities of all forms of art. Known for developing the Happening in the late 1950s, Kaprow’s later work included meditative performances, such as Trading Dirt . This durational performance, dematerialized the art object, while at the same time, it ritualized the mundane process of moving dirt from one person and place to another. Trading Dirt began in 1982 or 1983 when the artist was studying at the Zen Center in San Diego, California and represents a shift from his earlier Happenings of the 1960s, to a more intimate and time-based work.

Trading Dirt is referred to as a durational performance because the passage of time is an essential element to the work. The work unfolds sporadically over a number of years, whenever Kaprow felt like initiating the process, ending in about 1985. Kaprow begins the performance by trading buckets filled with dirt from the Zen Center for dirt from his own backyard. He then trades soil with friends, farmers, and others. The act of trading dirt, especially with strangers, led to spontaneous actions and conversations that become a part of the work. You can watch Kaprow tell a story about the process and his motivations for Trading Dirt in a video from Media Art Services linked here (14:36 minutes).

Influenced by composer John Cage’s emphasis on the sounds between the notes (See his 4’33” for example. You can also find a further discussion of Cage’s influence in the chapter on Social Practices.), Kaprow was interested in the human interactions and chance encounters between the act of trading dirt.

Of Trading Dirt , Kaprow writes, “The dirt trading and the stories went on for three years. It had no real beginning or end. The stories began to add up to a very long story, and with each retelling they changed. When I stopped being interested in the process (it coincided with my wife and I having to move after our rental property was sold), I put the last bucket of dirt back into the garden.” ( Trading Dirt , 1982/83-1985) (Kaprow, 1993)

Stop & Reflect: Allan Kaprow

- Kaprow wrote, “‘Life is much more interesting than art. The line between art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible” (Kaprow, Untitled , p. 709). How does work, like Trading Dirt , exemplify this quote?

- How does Kaprow’s work honor chance encounters and lend significance to everyday events?

- Can you relate Happenings back to what you’ve learned about Dada and Fluxus?

- As we’ve noted, many of the artists discussed in this text make work that is difficult to categorize and can be understood through multiple lenses. Read about Allan Kaprow’s Happenings in the Social Practice chapter , if you have not already done so. What are some differences between the way his work is contextualized in that chapter vs. the way his work is contextualized in the history of performance art?

- Why do you think Happenings fit into both categories?

Tehching Hsieh, Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980-1981) , 1980-81

Another example of a durational performance is Tiwanese American artist, Tehching Hsieh’s (born 1950) Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980-1981) . Durational performances can express an artist’s endurance because they happen over a long period of time. Hsieh’s performance everyday, for a full year, also explores our relationship to time by revealing it as a precondition for all life .

Scholar Ash Dilkes discusses Hsieh’s interest in collapsing boundaries between “art time” and “life time.” In a durational performance, lines between art and life are ultimately blurred as Hsieh must wake himself up every hour to punch a time clock, which he has installed inside his studio, for the duration of the yearlong performance. The process of documentation became so a part of Hsieh’s daily routine that he only missed 133 punches out of 8,760 (Dilkes). His life is the performance; art and life are experienced simultaneously, reflecting a culmination of a central goal of Performance Art as the boundaries between art and life are dissolved.

Stop & Reflect: Tehching Hsieh

Watch the following 2 videos on Tehching Hsieh and his performance practices (2:36 and 3:38 minutes):

Next, watch the artist and curator Nina Miall discuss Tehching Hsieh’s Time Clock Piece (the second of his one-year performances). (Das Platforms Multimedia Projects, 9:05 minutes):

- Watch the stop motion embedded above. How is the passage of time reflected in Hsieh’s self-portraits?

- Consider the role of process in Hsieh’s performance. Do you think the artist’s experience of creating the work is more important than any objects or records that are the outcome of the process? Why or why not?

- What do the installation views of the performance reveal to the viewer about Hsieh’s performance and process?

- Especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, can you describe a moment from your own life that helps you relate to the repetitive quality of Hsieh’s work?

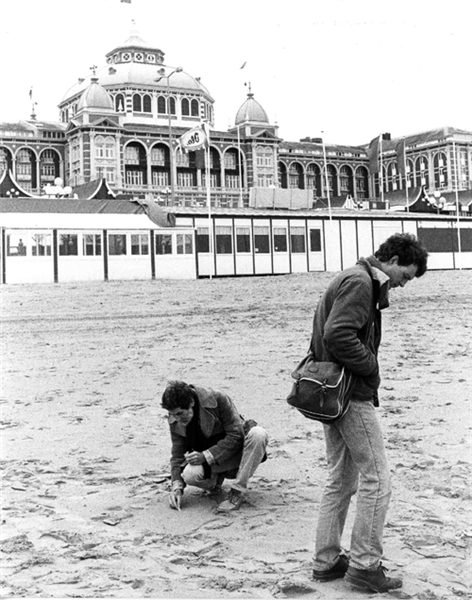

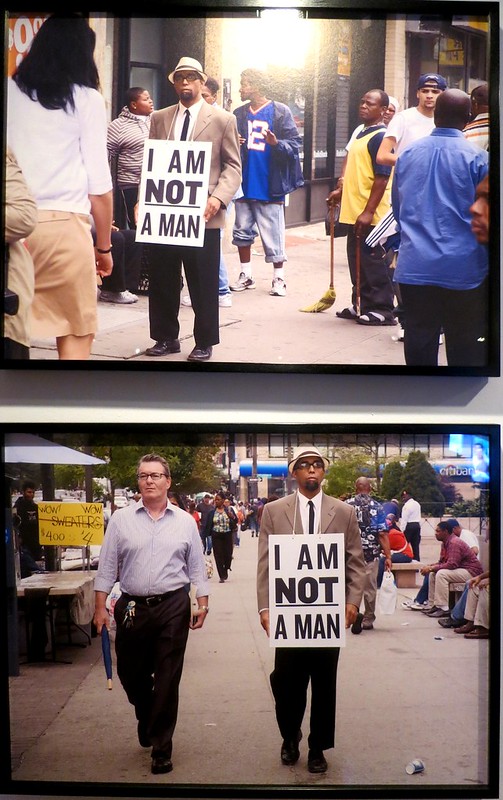

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale , 1983

David Hammons (born 1943) is a sculptor, printmaker, performance, and installation artist known for his ephemeral public performances and installations. Remaining intentionally elusive to the museum and gallery systems, Hammons’ work explores and critiques systemic racism in the United States. In David Hammons: Bliz-aard Ball Sale , author Elena Filipovic writes:

“You cannot think of these works or of Hammons’ street actions in general without reckoning with what blackness meant (and means still) in public space. Or without acknowledging that by putting himself out on a street corner with his wares, Hammons may well have been playing with racist stereotypes associated with blacks (homeless vagrant, street hustler, drug pusher) and at the same time undercutting them through his calm, serious stance and willfully elegant style. The adage “the white man’s ice is colder” speaks for the sort of internalized racism that causes black Americans to believe that businesses, products and services offered by whites are better, more reliable. Turning the expression on its head, Hammons’ act implicitly suggested that although you could easily make your own snowball, this black man’s ice was worthy of purchase; it was perhaps colder, even.”

Documented through photographs, Hammons performed Bliz-aard Ball Sale on a New York City street near Cooper Square in 1983. He laid out a woven rug and set out his snowballs, carefully arranging them in descending order, according to size. Each snowball was crafted using spherical molds, so they have a perfectly round shape, something you couldn’t as easily achieve if you formed each snowball by hand.

In addition to evaluating Hammons’ street actions as a reflection on his experience as a Black American, another way to interpret Bliz-aard Ball Sale is as a critique of the art market and the value attributed to artworks by galleries and auction houses. The snowballs Hammons hawked were, by their very nature, ephemeral objects that he seemingly sought to profit from. They are also commonplace (especially in New York in December), so by assigning value to them, Hammons draws attention to the arbitrary nature of the art market, presenting a contrast between the art world and the more tenuous financial position of the street vendor.

Stop & Reflect: David Hammons

- In an interview, when asked whether or not he thought is work is political, Hammons replied, “I don’t know. I don’t know what my work is. I have to wait and hear that from someone.” So, what do you think? What is an argument for Hammons’ work as political? If not, what do you think his work is about?

- In what ways would being presented in a museum or gallery space change the meaning of Blizz-ard Ball Sale ? Why is site important to Hammons’ performance?

Focus: 1990s: The Social Body

In this next section, we’ll turn to three artists whose performances address politics and identity. For our case studies, we’ll review a performance by the Chinese artist Zhang Huan whose work about the human condition pushes his own body to extremes, often under the watchful and suspicious eye of the Chinese authorities. We’ll also study work by Tania Bruguera, a Cuban artist who conceptualizes performances critical of the Cuban government and of authoritarianism more broadly. She has had her passport confiscated and her works banned in her home country. Finally, we’ll look at Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian performance, multimedia, and installation artist whose piece, Roadworks (Performance Stills) , investigates how individuals struggle under authoritarian control.

Zhang Huan, 12 Square Meters, 1994