DAVID A. KLEIN, MD, MPH, SCOTT L. PARADISE, MD, AND EMILY T. GOODWIN, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(11):645-653

Related editorial: The Responsibility of Family Physicians to Our Transgender Patients

See related article from Annals of Family Medicine : Primary Care Clinicians' Willingness to Care for Transgender Patients

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Persons whose experienced or expressed gender differs from their sex assigned at birth may identify as transgender. Transgender and gender-diverse persons may have gender dysphoria (i.e., distress related to this incongruence) and often face substantial health care disparities and barriers to care. Gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation, sex development, and external gender expression. Each construct is culturally variable and exists along continuums rather than as dichotomous entities. Training staff in culturally sensitive terminology and transgender topics (e.g., use of chosen name and pronouns), creating welcoming and affirming clinical environments, and assessing personal biases may facilitate improved patient interactions. Depending on their comfort level and the availability of local subspecialty support, primary care clinicians may evaluate gender dysphoria and manage applicable hormone therapy, or monitor well-being and provide primary care and referrals. The history and physical examination should be sensitive and tailored to the reason for each visit. Clinicians should identify and treat mental health conditions but avoid the assumption that such conditions are related to gender identity. Preventive services should be based on the patient's current anatomy, medication use, and behaviors. Gender-affirming hormone therapy, which involves the use of an estrogen and antiandrogen, or of testosterone, is generally safe but partially irreversible. Specialized referral-based surgical services may improve outcomes in select patients. Adolescents experiencing puberty should be evaluated for reversible puberty suppression, which may make future affirmation easier and safer. Aspects of affirming care should not be delayed until gender stability is ensured. Multidisciplinary care may be optimal but is not universally available.

In the United States, approximately 150,000 youth and 1.4 million adults identify as transgender. 1 , 2 As sociocultural acceptance patterns evolve, clinicians will likely care for an increasing number of transgender persons. 3 However, data from a large observational study suggests that 24% of transgender persons report unequal treatment in health care environments, 19% report refusal of care altogether, and 33% do not seek preventive services. 4 Approximately one-half report that they have taught basic tenets of transgender care to their health care professional. 4

A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-oriented evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to https://www.aafp.org/afpsort .

eTable A provides definitions of terms used in this article. Transgender describes persons whose experienced or expressed gender differs from their sex assigned at birth. 5 , 6 Gender dysphoria describes distress or problems functioning that may be experienced by transgender and gender-diverse persons; this term should be used to describe distressing symptoms rather than to pathologize. 7 , 8 Gender incongruence, a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases , 11th revision (ICD-11), 9 describes the discrepancy between a person's experienced gender and assigned sex but does not imply dysphoria or a preference for treatment. 10 The terms transgender and gender incongruence generally are not used to describe sexual orientation, sex development, or external gender expression, which are related but distinct phenomena. 5 , 7 , 8 , 11 It may be helpful to consider the above constructs as culturally variable, nonbinary, and existing along continuums rather than as dichotomous entities. 5 , 8 , 12 , 13 For clarity, the term transgender will be used as an umbrella term in this article to indicate gender incongruence, dysphoria, or diversity.

Optimal Clinical Environment

It is important for clinicians to establish a safe and welcoming environment for transgender patients, with an emphasis on establishing and maintaining rapport ( Table 1 ) . 5 , 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 – 21 Clinicians can tell patients, “Although I have limited experience caring for gender-diverse persons, it is important to me that you feel safe in my practice, and I will work hard to give you the best care possible.” 22 Waiting areas may be more welcoming if transgender-friendly materials and displayed graphics show diversity. 5 , 12 , 14 , 15 Intake forms can be updated to include gender-neutral language and to use the two-step method (two questions to identify chosen gender identity and sex assigned at birth) to help identify transgender patients. 5 , 16 , 23 Training clinicians and staff in culturally sensitive terminology and transgender topics, as well as cultural humility and assessment of personal internal biases, may facilitate improved patient interactions. 5 , 21 , 24 Clinicians may also consider advocating for transgender patients in their community. 12 , 14 , 15 , 21

MEDICAL HISTORY

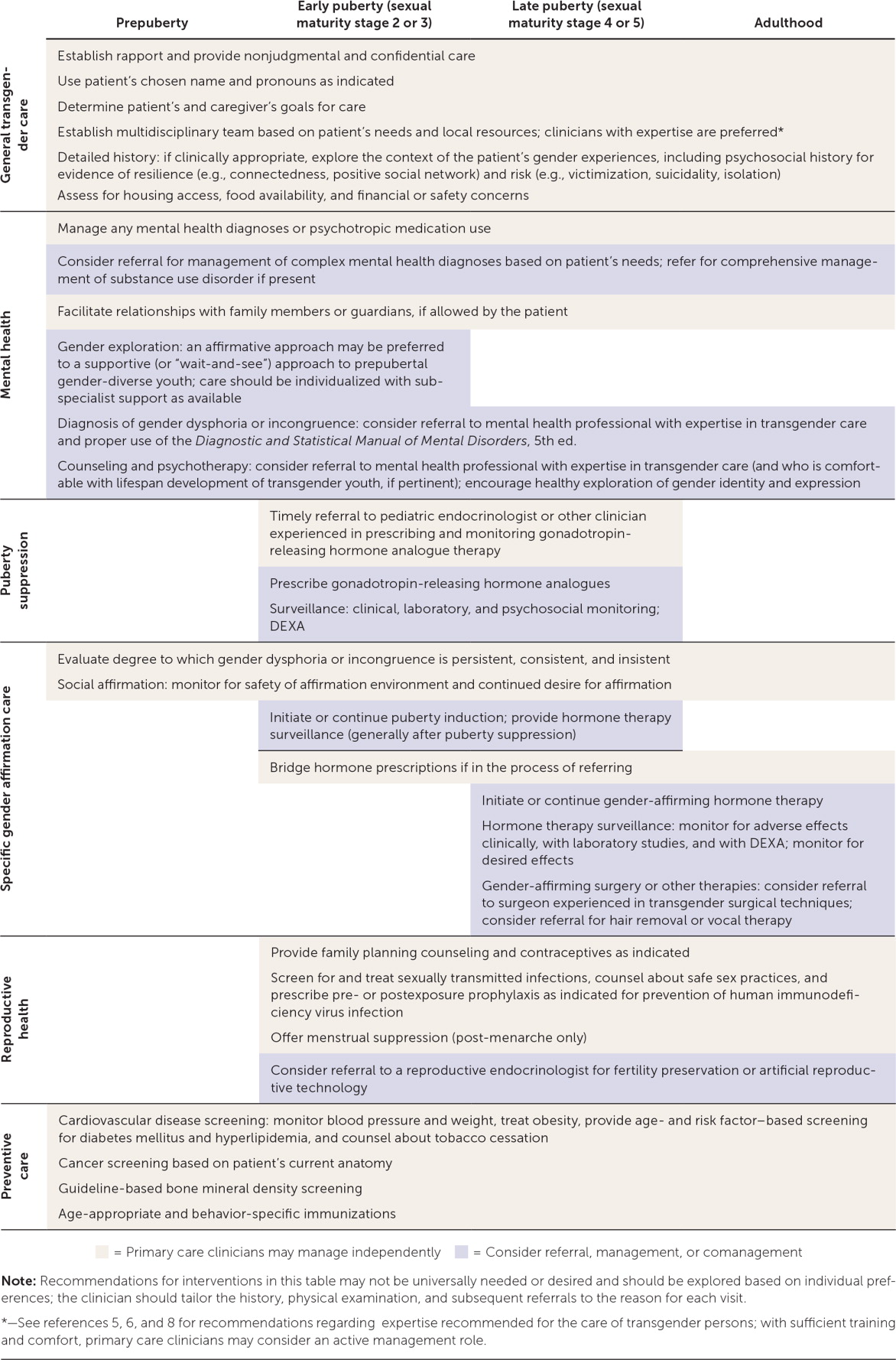

When assessing transgender patients for gender-affirming care, the clinician should evaluate the magnitude, duration, and stability of any gender dysphoria or incongruence. 8 , 12 Treatment should be optimized for conditions that may confound the clinical picture (e.g., psychosis) or make gender-affirming care more difficult (e.g., uncontrolled depression, significant substance use). 6 , 11 , 17 The support and safety of the patient's social environment also warrants evaluation as it pertains to gender affirmation. 6 , 8 , 11 This is ideally accomplished with multidisciplinary care and may require several visits to fully evaluate. 5 , 6 , 8 , 17 Depending on their comfort level and the availability of local subspecialty support, primary care clinicians may elect to take an active role in the patient's gender-related care by evaluating gender dysphoria and managing hormone therapy, or an adjunctive role by monitoring well-being and providing primary care and referrals ( Figure 1 ) . 5 , 6 , 8 , 11 – 15 , 17 , 19 , 21 , 22

Clinicians should not consider themselves gatekeepers of hormone therapy; rather, they should assist patients in making reasonable and educated decisions about their health care using an informed consent model with parental consent as indicated. 5 , 17 Based on expert opinion, the Endocrine Society recommends that clinicians who diagnose gender dysphoria or incongruence and who manage gender-affirming hormone therapy receive training in the proper use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed., and the ICD; have the ability to determine capacity for consent and to resolve psychosocial barriers to gender affirmation; be comfortable and knowledgeable in prescribing and monitoring hormone therapies; attend relevant professional meetings; and, if applicable, be familiar with lifespan development of transgender youth. 6

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Transgender patients may experience discomfort during the physical examination because of ongoing dysphoria or negative past experiences. 4 , 5 , 8 Examinations should be based on the patient's current anatomy and specific needs for the visit, and should be explained, chaperoned, and stopped as indicated by the patient's comfort level. 5 Differences of sex development are typically diagnosed much earlier than gender dysphoria or gender incongruence. However, in the absence of gender-affirming hormone therapy, an initial examination may be warranted to assess for sex characteristics that are incongruent with sex assigned at birth. Such findings may warrant referral to an endocrinologist or other subspecialist. 6 , 25

Mental Health

Transgender patients typically have high rates of mental health diagnoses. 11 , 18 However, it is important not to assume that a patient's mental health concerns are secondary to being transgender. 5 , 12 , 15 Primary care clinicians should consider routine screening for depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use, intimate partner violence, self-injury, bullying, truancy, homelessness, high-risk sexual behaviors, and suicidality. 5 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 19 , 26 – 29 Clinicians should be equipped to handle the basic mental health needs of transgender persons (e.g., first-line treatments for depression or anxiety) and refer patients to subspecialists when warranted. 5 , 8 , 15

Because of the higher prevalence of traumatic life experiences in transgender persons, care should be trauma-informed (i.e., focused on safety, empowerment, and trustworthiness) and guided by the patient's life experiences as they relate to their care and resilience. 5 , 15 , 30 Efforts to convert a person's gender identity to align with their sex assigned at birth—so-called gender conversion therapy—are unethical and incompatible with current guidelines and evidence, including policy from the American Academy of Family Physicians. 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 31

Health Maintenance

Preventive services are similar for transgender and cisgender (i.e., not transgender) persons. Nuanced recommendations are based on the patient's current anatomy, medication use, and behaviors. 5 , 6 , 32 Screening recommendations for hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, hypertension, and obesity are available from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). 33 Clinicians should be vigilant for signs and symptoms of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and metabolic disease because hormone therapy may increase the risk of these conditions. 5 , 6 , 34 Screening for osteoporosis is based on hormone use. 6 , 35

Cancer screening recommendations are determined by the patient's current anatomy. Transgender females with breast tissue and transgender males who have not undergone complete mastectomy should receive screening mammography based on guidelines for cisgender persons. 6 , 36 Screening for cervical and prostate cancers should be based on current guidelines and the presence of relevant anatomy. 5 , 6

Recommendations for immunizations (e.g., human papillomavirus) and screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (including human immunodeficiency virus) are provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and USPSTF based on sexual practices. 32 , 33 , 37 , 38 Pre- and postexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus infection should be considered for patients who meet treatment criteria. 32 , 38

Hormone Therapy

Feminizing and masculinizing hormone therapies are partially irreversible treatments to facilitate development of secondary sex characteristics of the experienced gender. 6 Not all gender-diverse persons require or seek hormone treatment; however, those who receive treatment generally report improved quality of life, self-esteem, and anxiety. 5 , 6 , 39 – 44 Patients must consent to therapy after being informed of the potentially irreversible changes in physical appearance, fertility potential, and social circumstances, as well as other potential benefits and risks.

Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogen and antiandrogens to decrease the serum testosterone level below 50 ng per dL (1.7 nmol per L) while maintaining the serum estradiol level below 200 pg per mL (734 pmol per L). 6 Therapy may reduce muscle mass, libido, and terminal hair growth, and increase breast development and fat redistribution; voice change is not expected. 5 , 6 The risk of VTE can be mitigated by avoiding formulations containing ethinyl estradiol, supraphysiologic doses, and tobacco use. 34 , 45 – 47 Additional risks include breast cancer, prolactinoma, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, cholelithiasis, and hypertriglyceridemia; however, these risks are rare (yet clinically significant), indolent, or incompletely studied. 5 , 6 , 36 , 48 Spironolactone use requires monitoring for hypotension, hyperkalemia, and changes in renal function. 5 , 6

Masculinizing hormone therapy includes testosterone to increase serum levels to 320 to 1,000 ng per dL (11.1 to 34.7 nmol per L). 6 Anticipated changes include acne, scalp hair loss, voice deepening, vaginal atrophy, clitoromegaly, weight gain, facial and body hair growth, and increased muscle mass. Patients receiving masculinizing hormone therapy are at risk of erythrocytosis, as determined by male-range reference values (e.g., hematocrit greater than 50%). 5 , 6 , 45 , 49 Data on patient-oriented outcomes (e.g., death, thromboembolic disease, stroke, osteoporosis, liver toxicity, myocardial infarction) are sparse. Despite possible metabolic effects, few serious events have been identified in meta-analyses. 6 , 34 , 35 , 45 , 46 , 49

Active hormone-sensitive malignancy is an absolute contraindication to gender-affirming hormone treatment. 5 Patients who are older, use tobacco, or have severe chronic disease, current or previous VTE, or a history of hormone-sensitive malignancy may benefit from individualized dosing regimens and subspecialty consultation. 5 The benefits and risks of treatment should be weighed against the risks of inaction, such as suicidality. 5 The use of low-dose transdermal estradiol-17 β (Climara) may reduce the risk of VTE. 5

Some patients without coexisting conditions may prefer a lower dose or individualized regimen. 5 All patients should be offered referral to discuss fertility preservation or artificial reproductive technology. 5 , 20 Table 2 5 , 6 , 17 , 22 , 50 and eTable B present surveillance guidelines and dosing recommendations for patients receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Surgery and Other Treatments

Gender-affirming surgical treatments may not be required to minimize gender dysphoria, and care should be individualized. 6 Mastectomy (i.e., chest reconstruction surgery) may be performed for transmasculine persons before 18 years of age, depending on consent, duration of applicable hormone treatment, and health status. 6 Breast augmentation for transfeminine persons may be timed to maximal breast development from hormone therapy. 5 , 6 Mastectomy or breast augmentation generally costs less than $10,000, and insurance coverage varies. 51 Patients may also request referral for facial and laryngeal surgery, voice therapy, or hair removal. 5 , 6 , 8

The Endocrine Society recommends that persons who seek fertility-limiting surgeries reach the legal age of majority, optimize treatment for coexisting conditions, and undergo social affirmation and hormone treatment (if applicable) continuously for 12 months. 6 Adherence to hormone therapy after gonadectomy is paramount for maintaining bone mineral density. 6 Despite associated costs, varying insurance coverage, potential complications, and the potential for prolonged recovery, 6 , 8 , 51 gender-affirming surgeries generally have high satisfaction rates. 6 , 42

Transgender Youth

Most, but not all, transgender adults report stability of their gender identity since childhood. 17 , 52 However, some gender-diverse prepubertal children subsequently identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual adolescents, or have other identities instead of transgender, 8 , 11 , 17 , 53 – 55 as opposed to those in early adolescence, when gender identity may become clearer. 5 , 8 , 11 , 17 , 43 , 44 , 53 , 55 There is no universally accepted treatment protocol for prepubertal gender-diverse children. 6 , 12 , 17 Clinicians may preferentially focus on assisting the child and family members in an affirmative care strategy that individualizes healthy exploration of gender identity (as opposed to a supportive, “wait-and-see” approach); this may warrant referral to a mental health clinician comfortable with the lifespan development of transgender youth. 6 , 12 , 13 , 21

Transgender adolescents should have access to psychological therapy for support and a safe means to explore their gender identity, adjust to socioemotional aspects of gender incongruence, and discuss realistic expectations for potential therapy. 6 , 8 , 12 , 17 The clinician should advocate for supportive family and social environments, which have been shown to confer resilience. 14 , 18 , 21 , 40 , 56 , 57 Unsupportive environments in which patients are bullied or victimized can have adverse effects on psychosocial functioning and well-being. 21 , 58 , 59

Transgender adolescents may experience distress at the onset of secondary sex characteristics. Clinicians should consider initiation of or timely referral for a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) to suppress puberty when the patient has reached stage 2 or 3 of sexual maturity. 5 , 6 , 8 , 17 , 21 , 40 , 44 This treatment is fully reversible, may make future affirmation easier and safer, and allows time to ensure stability of gender identity. 6 , 17 No hormonal intervention is warranted before the onset of puberty. 6 , 8 , 17

Consent for treatment with GnRH analogues should include information about benefits and risks 5 , 6 , 8 , 15 , 50 ( eTable B ) . Before therapy is initiated, patients should be offered referral to discuss fertility preservation, which may require progression through endogenous puberty. 5 , 6

Some persons prefer to align their appearance (e.g., clothing, hairstyle) or behaviors with their gender identity. The risks and benefits of social affirmation should be weighed. 5 , 6 , 8 , 13 , 17 , 56 Transmasculine postmenarcheal youth may undergo menstrual suppression, which typically provides an additional contraceptive benefit (testosterone alone is insufficient). 5 Breast binding may be used to conceal breast tissue but may cause pain, skin irritation, or skin infections. 5

Multiple studies report improved psychosocial outcomes after puberty suppression and subsequent gender-affirming hormone therapy. 39 – 42 , 44 , 60 Delayed treatment may potentiate psychiatric stress and gender-related abuse; therefore, withholding gender-affirming treatment in a wait-and-see approach is not without risk. 8 Additional resources for transgender persons, family members, and clinicians are presented in eTable C .

Data Sources: PubMed searches were completed using the MeSH function with the key phrases transgender, gender dysphoria, and gender incongruence. The reference lists of six cited manuscripts were searched for additional studies of interest, including three relevant reviews and guidelines by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health; the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California, San Francisco; and the Endocrine Society. Other queries included Essential Evidence Plus and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search dates: November 1, 2017, to September 18, 2018.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force; the Department of Defense; or the U.S. government.

Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):118-122.

Herman JL, Flores AR, Brown TN, Wilson BD, Conron KJ. Age of individuals who identify as transgender in the United States. January 2017. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/TransAgeReport.pdf . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):e1-e8.

Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2nd ed. June 17, 2016. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2018;103(2):699]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism. 2012;13(4):165-232.

World Health Organization. ICD-11: classifying disease to map the way we live and die. Coding disease and death. June 18, 2018. http://www.who.int/health-topics/international-classification-of-diseases . Accessed August 25, 2018.

Reed GM, Drescher J, Krueger RB, et al. Disorders related to sexuality and gender identity in the ICD-11: revising the ICD-10 classification based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations [published correction appears in World Psychiatry . 2017;16(2):220]. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):205-221.

Adelson SL American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):957-974.

American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70(9):832-864.

de Vries AL, Klink D, Cohen-Kettenis PT. What the primary care pediatrician needs to know about gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):1121-1135.

Levine DA Committee on Adolescence. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e297-e313.

Klein DA, Malcolm NM, Berry-Bibee EN, et al. Quality primary care and family planning services for LGBT clients: a comprehensive review of clinical guidelines. LGBT Health. 2018;5(3):153-170.

Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients—practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843-847.

Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171-176.

Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):943-951.

Marcell AV, Burstein GR Committee on Adolescence. Sexual and reproductive health care services in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20172858.

Klein DA, Berry-Bibee EN, Keglovitz Baker K, Malcolm NM, Rollison JM, Frederiksen BN. Providing quality family planning services to LGBTQIA individuals: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;97(5):378-391.

Rafferty J Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162.

Klein DA, Ellzy JA, Olson J. Care of a transgender adolescent. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(2):142-148.

Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. J Sex Res. 2013;50(8):767-776.

Keuroghlian AS, Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sex Health. 2017;14(1):119-122.

Lee PA, Nordenström A, Houk CP, et al. Global DSD Update Consortium. Global disorders of sex development update since 2006: perceptions, approach and care [published correction appears in Horm Res Paediatr 2016;85(3):180]. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85(3):158-180.

de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(11):1195-1202.

Olson J, Schrager SM, Belzer M, Simons LK, Clark LF. Baseline physiologic and psychosocial characteristics of transgender youth seeking care for gender dysphoria. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(4):374-380.

Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, et al. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173845.

Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of transgender adults in the U.S., 2014–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(3):336-344.

Richmond KA, Burnes T, Carroll K. Lost in translation: interpreting systems of trauma for transgender clients. Traumatology. 2012;18(1):45-57.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Reparative therapy. 2016. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/reparative-therapy.html . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Edmiston EK, Donald CA, Sattler AR, Peebles JK, Ehrenfeld JM, Eckstrand KL. Opportunities and gaps in primary care preventative health services for transgender patients: a systemic review. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):216-230.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. USPSTF A and B recommendations. June 2018. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/uspstf-a-and-b-recommendations . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Sex steroids and cardiovascular outcomes in transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3914-3923.

Singh-Ospina N, Maraka S, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Effect of sex steroids on the bone health of transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3904-3913.

Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191-198.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization schedules. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep . 2015;64(33):924]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

Costa R, Colizzi M. The effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on gender dysphoria individuals' mental health: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1953-1966.

de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):696-704.

Gómez-Gil E, Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Esteva I, et al. Hormone-treated transsexuals report less social distress, anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(5):662-670.

Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(2):214-231.

Steensma TD, Biemond R, de Boer F, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16(4):499-516.

de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2276-2283.

Meriggiola MC, Gava G. Endocrine care of transpeople part I. A review of cross-sex hormonal treatments, outcomes and adverse effects in transmen. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83(5):597-606.

Weinand JD, Safer JD. Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision; A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):55-60.

Asscheman H, T'Sjoen G, Lemaire A, et al. Venous thrombo-embolism as a complication of cross-sex hormone treatment of male-to-female transsexual subjects: a review. Andrologia. 2014;46(7):791-795.

Joint R, Chen ZE, Cameron S. Breast and reproductive cancers in the transgender population: a systematic review [published online ahead of print April 28, 2018]. BJOG . https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1471-0528.15258 . Accessed August 25, 2018.

Jacobeit JW, Gooren LJ, Schulte HM. Safety aspects of 36 months of administration of long-acting intramuscular testosterone undecanoate for treatment of female-to-male transgender individuals. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(5):795-798.

Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, et al. ; ESPE-LWPES GnRH Analogs Consensus Conference Group. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e752-e762.

Kailas M, Lu HM, Rothman EF, Safer JD. Prevalence and types of gender-affirming surgery among a sample of transgender endocrinology patients prior to state expansion of insurance coverage. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(7):780-786.

Landén M, Wålinder J, Lundström B. Clinical characteristics of a total cohort of female and male applicants for sex reassignment: a descriptive study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(3):189-194.

Steensma TD, McGuire JK, Kreukels BP, Beekman AJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(6):582-590.

Drummond KD, Bradley SJ, Peterson-Badali M, Zucker KJ. A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):34-45.

Wallien MS, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1413-1423.

Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2016;137(3):e20153223]. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153223.

Johns MM, Beltran O, Armstrong HL, Jayne PE, Barrios LC. Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: a systematic review by socioecological level. J Prim Prev. 2018;39(3):263-301.

Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(6):1580-1589.

de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT, VanderLaan DP, Zucker KJ. Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(6):579-588.

Chew D, Anderson J, Williams K, May T, Pang K. Hormonal treatment in young people with gender dysphoria: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173742.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

IMAGES

VIDEO