- Our Professionals

- Our Insights

- Your Finnegan

- Articles & Books

- Ad Law Buzz Blog

- At the PTAB Blog

- European IP Blog

- Federal Circuit IP Blog

- INCONTESTABLE® Blog

- IP Health Blog

- Prosecution First Blog

- Events & Webinars

- Unified Patent Court (UPC) Hub

Granting or Recording a Security Interest in a Patent at the USPTO Does Not Deprive the Patent Owner of the Ability to Enforce the Patent

October 6, 2020

LES Insights

By John C. Paul ; D. Brian Kacedon ; Anthony D. Del Monaco; Umber Aggarwal

A patentee did not lose the ability to bring a patent infringement lawsuit when it entered into a security interest agreement covering all of its intellectual property and the agreement was recorded at the USPTO

Raffel, a manufacturer of electronic controls for the seating, bedding and industrial marketplaces, entered into an “Intellectual Property Security Agreement” with two different banks granting the banks a security interest in all of its intellectual property. The banks filed notices of their security interests with the USPTO. Shortly thereafter, Raffel sued Man Wah for patent infringement and other causes of actions. In response, Man Wah moved to dismiss Raffel’s patent infringement claims arguing that Raffel lacked the right to sue for infringement because the security agreements transferred title of Raffel’s intellectual property to the banks.

Trial Court’s Decision

Lenders take security interests in a debtor’s intellectual property and other assets to protect themselves if the debtor defaults on a loan. In some instances, the lender demands that the security agreement transfer the ownership in the intellectual property until the loan is repaid.

The trial court found the act of granting a security interest in intellectual property and recording that security interest at the USPTO did not transfer title of the patents from Raffel to the banks, and, therefore, Raffel retained the right to enforce the patents.

To have the ability or “standing” to sue for patent infringement, an entity must satisfy the requirements of the U.S. constitution as well as the patent statute. To have constitutional standing, a plaintiff must possess exclusionary rights in the patent such as the right to prevent others from making, using, selling, or offering to sell the patented invention. Statutory standing further requires that the plaintiff have “all substantial rights” to the asserted patents through being the original patentee, an assignee, or an exclusive licensee of all such rights. If an entity has “exclusionary rights” in the patent but lacks “all substantial rights,” it typically must join the owner of the patent in any infringement suit.

Man Wah argued that Raffel’s grant of a security interest and the subsequent recording of that security interest transferred title to the banks and thus, deprived Raffel of “standing” to sue. In support, Man Wah relied on a Supreme Court case from 1891, Waterman v. Mackenzie , which supported the principle that recording a security interest in patents was equivalent to transferring title. The court noted, however, that Waterman was decided prior to the enactment of the Uniform Commercial Code (“UCC”) in 1952, which fundamentally changed the way a security interest is perfected. After the enactment of the UCC in 1952, transfer of title was unnecessary to perfect a security interest.

Man Wah asserted that state UCC laws provide only one way for a party to perfect security interests and are preempted by the Patent Act and Waterman when they conflict. Specifically, Man Wah argued that, under the Patent Act and Waterman , a security interest is created through transfer of the patent when it is recorded at the USPTO. Man Wah asserted that this preempts perfecting a security interest through the UCC which does not transfer title. The court rejected the preemption argument citing numerous cases showing the Patent Act does not address perfection in security interests, but only assignments of title, and, thus, does not preempt state regulation of security interests in patents.

In looking at the actual agreements with the banks, the court confirmed that “[n]othing in the Intellectual Property Security Agreements states that Raffel is assigning title of the patents to the banks; rather, the agreements specifically state that Raffel is granting a ‘security interest’ in its intellectual property.” Thus, Raffel never transferred title and maintained standing. The court, therefore, denied the motion to dismiss.

Strategy and Conclusion

A party receiving a security interest in a patent may record the security agreement with the USPTO to protect itself against and give notice to subsequent bona fide purchasers or mortgagees. Standard security agreements that do not include language assigning title of the patents, however, will not prevent a patentee from bringing a patent infringement lawsuit. This case demonstrates the value of drafting the security agreement in a way that does not transfer ownership of intellectual property to the lender while the loan is pending.

The Raffel decision can be found here .

Related Practices

Enforcement and Litigation

Related Industries

Communications

Financial Services and Business Systems

Related Offices

Washington, DC

Related Professionals

Education Center

Security Interests in Intellectual Property in the United States: Are They Really Secure?

by Scott J. Lebson 1

I. Introduction II. The Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.) – ARTICLE 9

A. Application of Article 9 B. Components of a Security Interest

III. The Problem of Preemption

A. Federal v. State Law

IV. Creation of a Security Interest

A. Security Agreement B. Attachment

V. Perfection of a Security Interest

A. Public Notice

VI. Perfection under the U.C.C.

A. Where to Perfect B. How to Perfect

VII. Perfection of Security Interests in Trademarks

A. Limitations upon Assignment and Relevance to Perfection B. U.C.C. Filing Required C. Dual Filings Recommended D. Intent-to-Use Applications

VIII. Perfection of Security Interests in Patents

Ix. perfection of security interests in copyrights.

A. Federally Registered Copyrights B. Unregistered Copyrights

X. Perfection of Security Interests in Domain Names

XI. International Creation and Perfection of Security Interests

A. Local Requirements B. Madrid Agreement and Protocol

XII. Future Perfection Schemes and Pending Legislation

Xiii. conclusion, i. introduction.

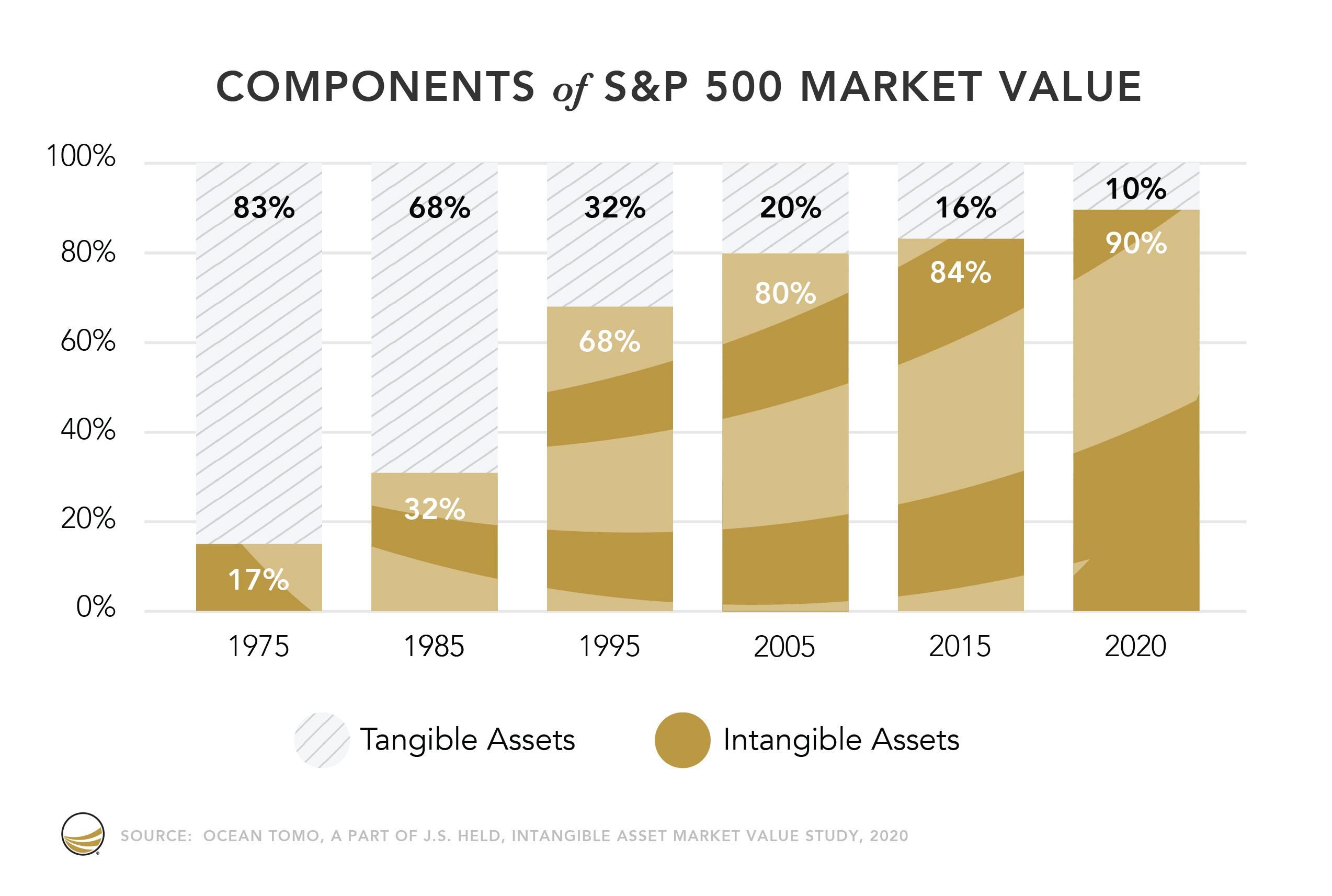

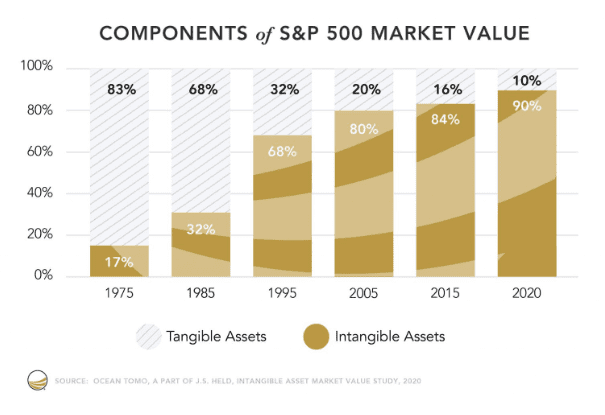

Intellectual property assets are particularly valuable because they enable companies to create and hold monopoly power on unique products and services. Key intellectual property rights can provide owners with significant business advantages by allowing, for example, the creation of specialized goods that are capable of generating high profit margins. This situation contrasts with competitors that can produce only standardized products selling at much lower margins. In fact, the driving force behind a majority of mergers and acquisitions completed during the past decade has been the acquirer’s desire to obtain the target’s intellectual property assets. However, the full financial potential of intellectual property cannot be realized unless it can be readily used as a source of funding to facilitate other commercial transactions. Lenders and other professionals in the investment community have come to recognize that a company’s intellectual property is its most valuable asset. Secured transactions are a preferred method in which the true value of intellectual property rights can be realized. This paper will discuss the creation, perfection and enforcement of security interests in the United States and touch briefly upon certain aspects of security interests in intellectual property abroad.

While the law with respect to the creation of security interests is fairly uniform across the 50 states of the United States under the Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.), the law surrounding the perfection of security interests in intellectual property remains quite unsettled.2 Companies who offer their intellectual property as collateral, and, in particular, lenders and other secured parties and their counsel, should be wary of the potential pitfalls which currently exist in the intellectual property securitization process.

II. The Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.) – ARTICLE 9

A. Application of Article 9.

Although intellectual property rights, in particular, patents, trademarks and copyrights, are often viewed as creatures of federal law, especially those used in interstate commerce, the creation (as opposed to perfection) of a security interest in intellectual property is governed by state law. Article 9 of the U.C.C. explicitly provides that it applies to any transaction, regardless of its form, that creates a security interest in personal property or fixtures by contract. 4 Section 9-109(a)(1) provides:

Except as otherwise provided in Subsection (c) and (d), this Article applies to:

(1) a transaction, regardless of its form, that creates a security interest in personal property or fixtures by contract…

More specifically, Article 9 of the U.C.C. governs security interests in “general intangibles”5 and general intangibles are considered personal property for purposes of U.C.C. interpretation. Section 9-102(42) of the U.C.C. defines “general intangibles” as “any personal property , including things in action, other than accounts, chattel paper, commercial tort claims, deposit accounts, documents, goods, instruments, investment property, letter of credit rights, money and oil, gas, or other minerals before extraction. The terms include payment intangibles and software.” 6

While reference to patents, trademarks and copyrights are not mentioned specifically in Section 9-102, the Official Comment uses the catch-all term “ intellectual property ” as an example of a general intangible7 and it is well-settled that patents, trademarks and copyrights fall within the definition of intellectual property.

B. Components of a Security Interest:

While it may seem initially that Article 9 would be the sole body of law that governs the securitization of intellectual property rights, there are three different components in the securitization process. These three components are:

1. creation;

2. perfection ; and

3. enforcement/release.

Difficulties stemming from preemption by federal law are encountered when secured parties are seeking to perfect their liens so as to obtain priority and make certain their rights are protected and enforceable if foreclosure is subsequently necessary.

A. Federal v. State Law:

Section 9-109(c)(1) of the U.C.C. states:

This article does not apply to the extent that:

(1) a statute, regulation or treaty of the United States preempts this article. 8

For intellectual property rights which are governed exclusively by state law, such as common law trademarks used in intra-state commerce and trade secrets, Article 9 is clear that no federal rules need to be followed or federal filings made. The creation, perfection and enforcement of intellectual property security interests in these common law properties are governed by state law. The issue becomes less clear when discussing perfection of intellectual property rights governed by federal law, such as patents, copyrights and trademarks that are used in interstate commerce. However, with respect to the creation of a security interest only, unless and until such time as there is a federal statute governing the creation of security interests in intellectual property, the choice of state law designated by a security agreement will determine whether a security interest has been properly created.9

IV. Creation of a Security Interest

A. security agreement:.

Section 9-201 (a) of the U.C.C. provides:

Except as otherwise provided in this chapter, a security agreement is effective according to its terms between the parties, against purchasers of the collateral and against creditors.

Although the U.C.C. provides that it will respect the terms of the security agreement, Article 9 sets forth certain basic requirements that must be met in order to create a valid security interest. Article 9-203 states that:

A security interest attaches to collateral when it becomes enforceable against the debtor with respect to the collateral, unless an agreement expressly postpones the time of attachment.10

B. Attachment:

The term “attachment” generally means “enforceable against the debtor”. 11 In order to be “ enforceable against the debtor”, Article 9 sets forth three basic requirements for creating an enforceable security interest in collateral. Article 9-203(b) states:

Except as otherwise provided….a security interest is enforceable only if:

(1) value has been given;

(2) the debtor has rights in the collateral or the power to transfer rights in the collateral to a secured party; and

(3)(A) the debtor has authenticated a security agreement that provides a description of the collateral…

A description of personal or real property is considered sufficient, whether or not it is specific, if it reasonably identifies what is described.12 When all three elements above exist, that is: value, debtor’s rights in the collateral and a signed agreement with an evidentiary requirement (the “description”), a valid security interest has been created between the parties and attaches to the collateral.13

V. Perfection of a Security Interest

A. public notice:.

After the creation of a security interest, perfection is of critical importance in that a secured party with a perfected security interest has greater rights than those of an unperfected secured or unsecured party.14 This is especially true in the event of bankruptcy. To “perfect” a security interest, the secured party must provide public notice of the existence of such interest by filing a lien notice with the applicable local, state or federal agency. The applicable jurisdiction and law depends upon the type of intellectual property involved.

In order to properly perfect a security interest under the U.C.C., a secured party must first determine:

1) where to perfect; and

2) how to perfect.

A. Where to Perfect :

The general rule under the U.C.C. discussing where security interests should be perfected is stated in Section 9-301, which provides:

Except as otherwise provided in this section, while a debtor is located in a jurisdiction, the local law of that jurisdiction governs perfection, the effect of perfection or non-perfection and the priority of a security interest in collateral. 15

Filing under the law of the debtor’s location is the general rule governing the perfection of security interests in both tangible and intangible collateral.16 This, of course, includes security interests against intellectual property. If the debtor has more than one “place of business”17, its location for purposes of perfection shall be considered its chief executive office.18 If the debtor’s location changes, the security interest is considered perfected for a period of four months, after which a new financing statement must be filed in the debtor’s new location.19 The filing generally takes place in either the Secretary of State’s Office where the debtor is located or in the county clerk’s office.20 It is recommended that dual filing at the state and local levels be made.

B. How to Perfect:

With respect to general intangibles, perfection cannot take place automatically, such as in the case of a purchase money security interest or by simply handing over possession. Rather, in order to perfect a security interest in general intangibles, this must take place by filing what is known as a “financing statement.”21 The financing statement must adequately describe the collateral which is the subject of a lien.22 If only certain intellectual property is serving as collateral, then that collateral must be separately identified.23 If, however, all general intangibles are to serve as collateral, there is no requirement under the U.C.C. that they be separately identified.24 Language to the effect of “all general intangibles now owned or hereinafter acquired by the debtor” is considered a sufficient statement.25

However, in the case of In re 199Z, Inc., a California bankruptcy court held that where the description of collateral merely referred to “general intangibles”, such description was wholly insufficient and the security interest was not properly perfected. 26 Unfortunately, for the defendant/creditor in this case, their attempt to perfect with the USPTO was also deemed insufficient and they were relegated to unsecured creditor status.27

As will be discussed in more detail herein, there are certain exceptions to perfection by filing under the U.C.C. The most notable exception regarding intellectual property is found in U.C.C. 9-310(b)(3) and 9-311(a)(1), which provide:

the filing of a financing statement is not necessary to perfect a security interest in property subject to a statute, regulation or treaty of the United States whose requirements for a security interest’s obtaining priority over the rights of a lien creditor with respect to the property preempt Section 9-310(a).

This subsection exempts from the filing provisions of Article 9 those instances where a system of federal filing has been established under federal law. This subsection makes clear that when such a system exists, perfection of a relevant security interest can be achieved only through compliance with that federal system, i.e., filing under Article 9 is not a permissible alternative.28

A. Limitations upon Assignment and Relevance to Perfection:

In order to consider how a security interest in a trademark is perfected, it is first necessary to discuss certain limitations upon trademark transfers, which have a secondary effect upon the creation of a security interest. Unlike most assets, including patents and copyrights, special statutory restrictions exist on the form that a transfer of a trademark may take.29 Section 1060 of the Lanham Act provides that:

A registered mark or a mark for which an application to register has been filed shall be assignable with the good will of the business in which the mark is used, or with that part of the good will of the business connected with the use of and symbolized by the mark.30

Trademarks function to identify and distinguish the owner’s goods from those of others and to indicate the source of those goods.31 As such, they cannot exist separate and apart from the ongoing business with which they have become associated.32 If a mark were separated from that business, it could no longer function to identify the source of the goods to which it was attached. It would therefore cease to be a trademark.33 The situation sought to be avoided is customer deception resulting from abrupt and radical changes in the nature and quality of the goods or services after assignment of the mark.34

Merely taking a security interest will not in and of itself violate the rule against an assignment “in-gross”, or without goodwill, inasmuch as a security interest is not an assignment.35 If, however, the debtor defaults and the creditor tries to take title to the mark pursuant to the security agreement, the prohibition against assignments “in-gross” may be triggered.36 Therefore, taking a security interest in a trademark without the associated goodwill could result in the trademark being voided upon foreclosure if the subsequent assignment also takes place without goodwill.37 In order to avoid this consequence, secured parties are advised to take a lien on other related assets associated with the products marketed under the trademark, such as accounts receivable, to make certain that in the event of foreclosure, the mere act of assignment would not in and of itself destroy the value of the collateral.38 The secured party need only acquire those assets necessary to ensure that a mark will continue to be connected with substantially the same products with which it has become associated.39

B. U.C.C. Filing Required:

The law with respect to perfection of security interests in trademarks is not settled. Perfection of a security interest in a trademark can be accomplished under Article 9 as a general intangible. Although the U.C.C. provides that any federal filing scheme would preempt its provisions, unlike Section 205 of the Copyright Act discussed later herein, Section 1060 of the Lanham Act currently only addresses the issue of assignment of trademarks, not liens on federally registered marks. 40 There is no specific mention or reference to mortgages, hypothecation, collateralization or any other synonym associated with taking a security interest. In In re 199Z Inc. , the defendant/creditor argued that its security interest could not be voided because it had perfected its security interest at the state level under the U.C.C. and at the federal level at the USPTO.41 The bankruptcy court held that an assignment of a trademark is an absolute transfer of the entire right, title and interest to the trademark and the grant of a security interest is not such a transfer.42 It is merely what the term suggests, namely, a device to secure indebtedness. It is a mere agreement to assign in the event of default by the debtor. Since a security interest in a trademark is not equivalent to an assignment, the filing of a security interest is not covered by the Lanham Act.43 Much to the dismay of the defendant/creditor, the court also held that its security interest was not properly perfected under the U.C.C. due to an insufficient description of collateral.44

Furthermore, in Trimarchi v. Together Development Corp. , a Massachusetts bankruptcy court rejected the notion that the Lanham Act created an exemption to state and local filing requirements under the Supremacy Clause45 and did not preempt the U.C.C.’s filing requirements to perfect a security interest.46 Additionally, the filing of a security interest was not the equivalent of an assignment and the Lanham Act makes no specific mention of security interests in its recording statute.47 It has been repeatedly held that for federal law to supersede the U.C.C., the federal statute itself must provide a method for perfecting the security interest.48

C. Dual Filings Recommended:

Without an express federal statute, the case law to date would suggest that the proper method of perfection of a security interest in federally registered trademarks is governed by the U.C.C. Interestingly, however, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) will accept and record security interests in trademarks. Thus, it has become common knowledge and common practice for secured parties to file and record such security interests with the USPTO. This, in turn, has led to the common misconception that recording with the USPTO will be sufficient. This misconception has caused confusion among secured parties who believe that they have taken the appropriate measures to properly protect their interests. Several courts have noted the dichotomy in how this area of the law has developed, which has been referred to by one judge as a “trap for the unwary”.49

Notwithstanding the foregoing, even though filing with the USPTO will have no legal effect in and of itself, it is still advisable to make such a filing. While filing with the USPTO will not perfect the lien, the filing will serve as notice to a subsequent purchaser, who in the course of due diligence, would be well advised to search the USPTO records for security interest recordals. Any purchaser who has notice of an unperfected lien would take the property subject to such lien.50 Accordingly, a defect in perfection under the U.C.C. may still allow the creditor to later enforce its lien against a subsequent purchaser.

D. Intent-to-Use Applications:

In the context of use-based trademarks, a trademark owner acquires common law rights in a trademark before it is entitled to registration of that mark under federal law. However, with the introduction of the “intent-to-use” (ITU) application, a trademark owner may acquire “inchoate” federal trademark rights before acquiring common law rights through actual use.51 Under the Article 9 concept of “rights in the collateral”, the secured party could claim an attached interest in the debtor’s rights in the mark protected under an ITU application before the mark gives rise to any rights under common law.52 However, Section 10 of the Lanham Act provides that no ITU application shall be assignable prior to the filing of an amendment to allege use or a verified statement of use unless the assignee succeeds to all or part of the assignor’s business.53

In Clorox v. Chemical Bank , the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board held that an outright pre-use assignment of an ITU application to a lender as part of a security agreement was prohibited.54 The Board subsequently invalidated the debtor’s trademark.55 However, the Board observed that the grant of a mere Article 9 security interest in a mark would not be considered an assignment and would not provoke a penalty for trademark trafficking.56 This would suggest that ITU applications can properly be taken as collateral, properly attached under Article 9 and presumably, made safe against the strong-arm powers of a bankruptcy trustee.57 Whether an ITU mark can be assigned to a creditor will depend upon whether commercial use has actually been made.

Although not specifically provided for in the Patent Act, liens on patents historically have been perfected by filing with the USPTO. Section 261 of the Patent Act provides:

Subject to the provisions of this title, patents shall have the attributes of personal property. Applications for patent, patents, or any interest therein, shall be assignable in law by an instrument in writing. 58

Similar to the Lanham Act, the patent assignment provision does not specifically address the issue of perfection of security interests in patents. The practice of filing with the USPTO stems from the Supreme Court case of Waterman v. McKenzie. 59 The Court in Waterman held that a recorded lien on a patent was tantamount to a delivery of possession, thereby permitting the secured party to sue for infringement. 60 The Court opined that:

A patent right is incorporeal property, not susceptible of actual delivery or possession; and the recording of a mortgage thereof in the Patent Office, is equivalent to a delivery of possession, and makes the title of the mortgagee complete towards all other persons, as well as against the mortgagor 61

Of course, while Waterman provided that perfection under the USPTO was proper, it could not specifically exclude the U.C.C. method of perfection since the U.C.C. did not exist in the 1890’s. Subsequent to Waterman and with the advent of the U.C.C., there has been a divergence in the lower courts as to whether U.C.C. perfection is proper. Leading this divergence are cases emerging from the bankruptcy courts. In In re Cybernetics, Inc. , the Ninth Circuit Court held that state U.C.C. recording requirements are not preempted by Section 261 of the Patent Act concerning assignments in that the Patent Act does not speak specifically to “security interests” and, therefore, recordal at the USPTO is not required in order to properly perfect.62 Therefore, the bankruptcy trustee as a hypothetical lien creditor could not avoid a lien on a patent that had been perfected under the U.C.C., but not with a federal filing.63 In the case of In re Transportation Design , the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of California entertained the question of whether a mere filing of a U.C.C.-1 Financing Statement was sufficient to perfect the security interest in a patent. In finding that the recordal at the USPTO was not required, the Court reasoned that with the advent of the U.C.C., it is no longer necessary to create a security interest by an assignment or transfer of title.64 The issue remains somewhat unsettled to this day, although dual filings under the U.C.C. and at the USPTO are still advisable.

A. Federally Registered Copyrights :

Of the three most prominent forms of intellectual property, namely, patents, trademarks and copyrights, only the Copyright Act currently provides for a federal perfection scheme. Section 205 of the Copyright Act provides:

Any transfer of copyright ownership or other document pertaining to a copyright may be recorded in the Copyright Office if the document filed for recordation bears the actual signature of the person who executed it, or if it is accompanied by a sworn or official certification that it is a true copy of the original, signed document. 65

At first glance, Section 205 does not appear to discuss securitization of copyrights in any manner whatsoever. However, upon closer scrutiny of the Copyright Act, the definition of a “transfer of copyright ownership” is defined under Section 101 as:

[A]n assignment, mortgage, exclusive license, or any other conveyance, alienation, or hypothecation of a copyright or of any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, whether or not it is limited in time or place of effect, but not including a nonexclusive license. 66

Case law under this section, including the leading case in this area, In re Peregrine Entertainment , has emphatically rejected any notion that federally registered copyrights are properly perfected under the U.C.C. or that a U.C.C. filing is an acceptable alternative method.67 The Peregrine court opined that even in the absence of express language, federal regulation will preempt state law if it is so pervasive as to indicate that Congress left no room for supplementary state regulation.68 In view of the comprehensive scope of the Copyright Act’s recording provisions, along with the unique federal interests they implicate, the Peregrine court held the view that federal law preempts state law in the context of registered copyrights.

B. Unregistered Copyrights :

Although security interests in registered copyrights can only be properly perfected by recording with United States Copyright Office, it has been held in cases such as In re World Auxiliary Power Co. that a bank’s security interest in unregistered copyrights was properly perfected pursuant to Article 9 of the U.C.C., as no other way existed for a secured creditor to preserve priority in an unregistered copyright.69 In In re World Auxiliary Power , whereby the Ninth Circuit rejected the notion that Peregrine could be extended to unregistered copyrights, the court stated that the effect of such an extension would be to make registration of copyrights a necessary prerequisite of perfecting a security interest.70 The court continued that such a requirement would effectively render unregistered copyrights useless as collateral, which was not the intent of the statute.71 On the other hand, other cases decided subsequent to Peregrine have extended Peregrine’s holdings to include unregistered copyrights as well, finding that only a federal fling with the Copyright Office was the proper method and if registration was required, then this was a necessary prerequisite to perfection.72 In In re AEG Acquisition Corp. and In re Avalon Software, Inc. , both courts held that perfection could only be obtained by first registering the copyrights and thereafter recording the security interest with the Copyright Office. A prudent creditor/secured party may want to insist on registration and recordal at the Federal level while simultaneously recording at the U.C.C. level against any unregistered rights.

X. Perfection of security interests in Domain Names:

To date, there have been no statutes, regulations or case law to suggest that the creation and perfection of security interests in domain names cannot be achieved under the U.C.C. under the rules set forth for general intangibles. The filing of a financing statement setting forth a description of the domain names to be used as collateral should ensure proper perfection. However, there is a split in both legal authority and among legal scholars and practitioners as to whether domain names are in fact a type of “property”. Many argue that a domain name is not property and that the registrant of a domain name receives only the conditional contractual right to the exclusive association of the registered domain name for the term of the registrations.73 The registrant does not, through its contract with the registry, obtain any rights against any other person other than the consequent exclusivity resulting from the fact that an identical domain name cannot be used during the term of registration.74 The legal status of domain names has been characterized by analogy to that of telephone numbers.75

On the other hand, The Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) authorizes in rem civil action against a domain name, suggesting that a domain name is a form of intangible property, especially since in rem actions are brought specifically against property. 76 Cases decided under the ACPA have held that Congress intended for domain names to be treated as property, at least with respect to the ACPA.77 Notwithstanding the split in legal thinking as to whether domain names are considered a form of property, domain names have nonetheless routinely been made subject to security interests created and perfected under the U.C.C.

A. Local Requirements:

As the value of intellectual property rights are more widely recognized now more than ever before and companies are placing a premium on the protection of these rights, the creation and perfection of security interests in intellectual property are becoming more common. Companies with substantial worldwide intellectual property portfolios are offering not only their domestic intellectual property rights as security to finance a transaction, but increasingly, their international rights as well. Towards that end, secured parties would be well advised to seek perfection of these security interests at the relevant registries in several, if not all, of the jurisdictions in which the intellectual property security interest has been granted. However, not all jurisdictions recognize the creation of security interests in intellectual property and, at the same time, offer a mechanism for perfection of same at the relevant intellectual property registry. Recordal of security interests in intellectual property may need to take place on the local level as well as at the relevant intellectual property registry and local counsel may need to be consulted in this regard.

Subsequent to identifying those jurisdictions which offer a mechanism for perfecting a security interest in intellectual property, it is critical to determine whether the security agreement will be accepted for recordal. While some jurisdictions will accept a standard security agreement, it may be necessary to effect certain amendments to the security agreement in order to create a valid security interest under local law. A common example of this would be changing the “governing law” provisions to that of the jurisdiction under which perfection is sought. In many instances, it may be necessary for the parties to execute several new security agreements tailored specifically for creating and perfecting liens in certain jurisdictions. Local counsel may need to be engaged to determine whether the security agreement will suffice for purposes of creating and perfecting a valid intellectual property security interest under local law.

In order to make certain that the secured party is not blindly undertaking the ministerial act of perfecting the security interest, it may be worthwhile to obtain a formal opinion letter of local counsel discussing some or all of the following points:

(1) whether any prior liens or encumbrances have been recorded against the rights;

(2) whether a valid security interest is created by the security agreement under local law;

(3) whether the security interest is capable of being perfected at the local Patent, Trademark or Copyright Registry; and

(4) subsequent to perfection, whether the security interest is capable of being enforced against third parties.

Simply determining which jurisdictions recognize perfection of security interests and identifying what supplemental documentation would be needed is not enough. A thorough cost-assessment of the value of the rights subject to the security interest may be worthwhile. In the end, it may not be worthwhile to proceed in a jurisdiction where sales or use does not exist. Factors to consider in this determination are:

(1) the number of IP rights subject to the security interest;

(2) the government fees in perfecting the security interest;

(3) local counsel fees in preparing an amended or new security agreement, supplemental documentation, opinion letters and handling the perfection of the security interests;

(4) the value of the rights as determined by notoriety and/or sales in the products;

(5) the sophistication of the jurisprudence in a particular jurisdiction; and

(6) other standard valuation benchmarks in determining the value of intellectual property rights.

In addition to cost considerations, time is also a factor when considering perfection of security interests abroad. While certain jurisdictions can typically record the security interest at the relevant Registry within 3-6 months, there are still many jurisdictions which typically require several years before recordal is officially reflected on the register. Therefore, in terms of obtaining the benefits of perfection by providing notice to third parties, proceeding in some of these jurisdictions may not be worthwhile.

In the event of a default, a secured party should be aware of what steps must be taken in order to enforce the security interest and foreclose on the intellectual property rights. If the defaulting party is unwilling to assign rights back to the secured party, the secured party may need to bring a court action under local commercial law.

B. Madrid Agreement and Protocol:

A registrant who furnishes their International Registration as security may notify the national Trademark Office of the jurisdiction in question to inform WIPO or inform WIPO directly, which will then record the security interest in the WIPO Register. It should be noted, however, that a security interest in a trademark may not be recognized under the laws of some of the national jurisdictions to which an International Registration has been extended, even if WIPO records the security interest effective against all designated jurisdictions.78 As a result, the national laws of the particular jurisdictions to which the International Registration has been extended should be reviewed.79

In view of the unsettled nature with respect to the perfection of security interests in intellectual property, considerable risk still exists with respect to exploiting the full financial potential of intellectual property. In recognition of this fact, several bills have been proposed in Congress to address this lack of uniformity. Proposals submitted within the last few years include the Intellectual Property Security Interest Coordination Act and the Intellectual Property Security Act. Both bills were very similar in that they recognized the shortcomings in the current system and the unsettled nature of the law in this area. Predictability and uniformity in the treatment of security interests on a federal level would help minimize the risk of loss or impairment of rights and make intellectual property collateral more valuable and useful than before. However, these bills were not passed and parties to commercial transactions should continue to look to the current state of the law for guidance in the financing and securitization of intellectual property.

In today’s rapidly changing global economy, intellectual property has been cast in a new and dynamic role in commercial lending transactions. The legal confusion stemming from preemption results in increased transaction costs and additional risks. Uncertainty with respect to priority of interests in secured transactions can reduce the value of intellectual property and, in some cases, foreclose access by intellectual property owners to much needed capital. Intellectual property owners, lenders and potential purchasers would all benefit from a uniform, dependable method for perfecting and tracking security interests in intellectual property.

1 Scott J. Lebson, a partner in the New York office of the intellectual property law firm Ladas & Parry LLP, has written and lectured extensively on intellectual property issues. Mr. Lebson can be reached at [email protected] .

2 karl llewellyn led development of the u.c.c. in the 1930’s and 1940’s. congress formalized and adopted the u.c.c. in 1952. since then the u.c.c. has been adopted by the 50 states and the district of columbia and has undergone several revisions. in new york and several other states, the most recent revisions to article 9 became effective on july 1, 2001., 3 all references to the uniform commercial code (u.c.c.) are to that version enacted by new york state, which is fairly typical of the u.c.c. provisions of most of the 50 states., 4 see u.c.c. 9-109(a)(1)., 5 see u.c.c. 9-102(42)., 7 see official comment, 9-102(d) providing that “general intangible is the residual category of personal property, including things in action, that is not included in the other defined types of collateral. examples are various categories of intellectual property and the right to payment of a loan that is not evidenced by chattel paper or an instrument. as used in the definition of “general intangible” “things in action” includes rights that arise under a license of intellectual property, including the right to exploit the intellectual property without liability for infringement., 8 see official comment, 9-109(c)(1), official comment 8, providing that subsection (c) (1) recognizes explicitly that this “article defers to federal law only when and to the extent that it must – i.e., when federal law preempts it”., 9 see u.c.c. 9-201(a)., 10 see u.c.c. 9-203(a)., 12 see u.c.c. 9-108(a). see also section 9-108(b) for specific examples of what is considered a reasonable identification., 13 see u.c.c. 9-203, official comment., 14 see baila h. celedonia, intellectual property in secured transactions, trademarks in business transactions, 108, 2002., 15 see u.c.c. 9-301(a)., 16 see u.c.c. 9-301. official comment (4)., 17 see u.c.c. 9-307(a) where a “place of business” is defined as “the place where a debtor conducts its affairs”., 18 see u.c.c. 9-307(b)(3)., 19 see u.c.c. 9-316(a)(2)., 20 see u.c.c. 9-501., 21 see u.c.c. 9-310(a)., 22 see u.c.c. 9-502(a)(3). see also baila h. celedonia, intellectual property in secured transactions, trademarks in business transactions forum, at 109, 2002., 23 see baila h. celedonia, at 109., 24 see id at 109., 26 see in re 199z, inc. v. valencia, inc., 137 b.r. 778 (c.d. cal. 1992)., 27 see id. as discussed later herein, trademarks are not properly perfected at the uspto, although there may be benefits to such recordal., 28 see u.c.c. 9-311(a)(1); official comment (2)., 29 see stuart m. riback, intellectual property licenses: the impact of bankruptcy, october 27, 2000., 30 see 15 u.s.c. §1060., 31 see melvin simensky, howard a. gootkin, “liberating untapped millions for investment collateral: the arrival of security interests in intangible assets” from intellectual property in the global marketplace, melvin simensky & lanning bryer, at 29.25., 32 see id. at 29.25., 33 see id. see also 1 j.t. mccarthy, trademarks and unfair competition, §18.01(2) at 18-5., 34 see id. at 18-16. see simensky at 29.25., 36 see e.g., haymaker sports, inc. v. turian, 581 f.2d. 257 (c.c.p.a.1978). the united states court of customs and patent appeals (now known as the u.s. court of appeals for the federal circuit) noted that the assignees never played an active role in the assignor’s business, never used the mark themselves, and never acquired any tangible assets or goodwill of the assignor. therefore, the court concluded that the assignment was invalid as an assignment-in-gross., 37 see marshak v. green, 746 f.2d 927 (2d cir. 1984); clark & freeman corp. v. heartland co. ltd., 811 f. supp. 137 (s.d.n.y. 1993)., 38 see riback, id. at 16. see matter of roman cleanser co., 802 f.2d (6th cir. 1986)., 39 see simensky, id. at 29.25., 40 see matter of roman cleanser co., 43 b.r. 940 (bankr. e.d. mich 1984) aff’d, 802 f.2d 207 (6 th cir. 1986); in re together dev. corp. , 227 b.r. 439, 441 ( d. mass. 1998); in re 199z, inc. , 137 b.r. 778 (bankr. c.d. cal. 1992). lanham act §1060 provides: “an assignment shall be void against any subsequent purchaser for valuable consideration without notice, unless the prescribed information reporting the assignment is recorded in the patent and trademark office within 3 months after the date of the assignment or prior to the assignment”., 41 see in re 199z, inc., 137 b.r. 778, 782., 45 see u.s. const. art.vi., cl.2., 46 see trimarchi v. together development corp., 255 b.r. 606 (d. mass. 2000)., 48 see in re america’s hobby center v. hudson united bank, 223 s.d.n.y. 275, 286 (1998). see also roman cleanser v. national acceptance, 43 b.r. 940, 944 (e.d. mich. 1984) (finding that the lanham act only covered assignments of trademarks and not security interests and holding that a security interest in a trademark is governed by article 9 of the u.c.c.; creditors committee v. capital bank, 41 b.r. 128, 131 (bankr. c.d. cal. 1984) (finding that it was not the purpose or intent of congress in enacting the lanham act to provide a method for the perfection of security interests in trademarks, trade names or applications for the registration of same)., 49 see in re together dev. corp., supra, 227 b.r. at 439., 50 see u.c.c. 9-301(1)(d)., 51 see 15 u.s.c. §1051(b). see also intellectual property as collateral, the journal of law and technology, franklin pierce law center, 41 idea 481 (2002). the term “inchoate” generally refers to an impartial or imperfect right. for example, in patent law, the right of an inventor to his invention while his patent application is pending is inchoate, until such time as the patent issues and the right matures as a full property right . see mullins mfg. co. v. booth, 125 f.2d 660, 664 (6 th cir. 1942)., 53 see id. see also 15 u.s.c. §1060., 54 see 40 u.s.p.q. 2d 1098 (1996)., 56 see id., 57 see intellectual property as collateral, the journal of law and technology, franklin pierce law center, 41 idea 481 (2002, 58 see 35 u.s.c. §261., 59 see waterman v. mckenzie, 138 u.s. 252 (1891)., 61 see waterman, at 138., 62 see in re cybernetic services, inc. , 252 f.3d 1039 (9th cir. 2001 ), cert. denied, 534 u.s. 1130 (u.s. 2002). see also in re pasteurized eggs corp. , 296 b.r. 283 (bankr. d.n.h.2003) holding that “the patent act does not contain any language regarding security interests, and therefore does not preempt state law. as such, perfection of a security interest in a patent requires filing a ucc-1 in accordance with state law. filing a security agreement with the pto does not perfect the security interest”., 63 see in re cybernetic services, inc., 252 f.3d 1039 (9th cir. 2001), cert. denied, 534 u.s. 1130 (u.s. 2002); see also in re transportation design & tech. , inc., 48 b.r. 635 (bankr. s.d. cal 1985); city bank & trust v. otto fabric, inc. 83 b.r. 780 (d.kan. 1988)., 64 see in re transportation design, 48 b.r. at 639., 65 see 17 u.s.c. §205., 66 see 17 u.s.c. §101., 67 see in re peregrine entertainment, ltd., 116 b.r.194 (c.d. cal. 1990)., 68 see id. at 199. see also hillsborough county v. automated medical laboratories, inc., 471 u.s. 707 (u.s. 1985)., 69 see in re world auxiliary power co., 303 f.3d 1120, 1128 (9th cir. 2002)., 70 see id. at 1130., 71 see id., 72 see aeg acquisition corp. 127 b.r. 34 (bankr. c.d. cal 1991), aff’d 161 b.r. 50 (9th cir. bap 1993); in re avalon, 209 b.r. 517 (bankr. d. ariz. 1997)., 73 see sheldon burshtein, a domain name is not intellectual property, world e-commerce & ip report, november, 2002, at 9. see also dorer v. arel, 60 f.supp. 2d 558 (e.d.va. 1999)., 74 see id at 9., 76 see id. at 10. see also 15 u.s.c. §1125(d)., 77 see id. at 10. see also porsche cars north america v. porsche.net, 302 f.3d 248 (4th cir. 2002)., 78 see ian jay kaufman & lanning g. bryer, worldwide trademark transfers, montgomery & taylor, at iii.d.8. (2002)..

Patent Assignment: Everything You Need to Know

A patent assignment is an irrevocable agreement for a patent owner to sell, give away, or transfer interest to an assignee, who can enforce the patent. 6 min read updated on November 05, 2020

Patent Assignment: What Is It?

A patent assignment is a part of how to patent an idea and is an irrevocable agreement for a patent owner to sell, give away, or transfer his or her interest to an assignee, who can benefit from and enforce the patent. The assignee receives the original owner's interest and gains exclusive rights to intellectual property. He or she can sue others for making or selling the invention or design.

There are four types of patent assignments:

Assignment of Rights - Patent Issued: This is for patents that have already been issued.

Assignment of Rights - Patent Application : This is for patents still in the application process. After filing this form, the assignee can be listed as the patent applicant.

Assignment of Intellectual Property Rights - No Patent Issued or Application Filed: This is for unregistered inventions with no patent.

Exclusive Rights

Advantages of a Patent Assignment

Assignees don't create a unique invention or design. They also don't go through the lengthy patent process. They simply assume exclusive rights to intellectual property.

Profit Potential

Many patents cover intellectual property that can earn the owner money. A patent owner can charge a lump sum sale price for a patent assignment. After the transfer, the assignee can start to earn profits from the patent. Both original owners and assignees can benefit from this business arrangement.

Disadvantages of a Patent Assignment

Too Many or Not Enough Inventors

Patents can have multiple owners who invented the product or design. Sometimes patents list too many or not enough inventors. When this happens, owners can argue about an incorrect filing. This kind of dispute can make a patent assignment impossible.

Limited Recourse

Older patents may already have many infringements. Not all patent assignments include the right to sue for past infringements. This is known as the right to causes of action. This can cost the assignee a lot of potential profit.

Examples of What Happens When You File a Patent Assignment vs. When You File a Patent License

When You File a Patent Assignment

The patent owner changes permanently. You file the paperwork with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Information about the new owner is available to the public.

Many owners charge a one-time fee for a patent assignment. The original owner doesn't receive additional payments or profits in the future. The new owner receives future profits.

When You File a Patent License

The patent owner doesn't change permanently. Most licenses have a time limit. At the end of the period, the original owner takes control again. Licensing information isn't always available through an online USPTO search. Contact the recordation office directly to get information about patent licenses.

The licensee can assign rights to another person or company. This adds another layer of ownership over the intellectual property.

Many owners charge royalties for a patent license. The licensee pays royalty fees throughout the license period. If the royalty fees are high and the license period is long, a patent assignment may be a better choice for earning the new owner more money.

Common Mistakes

Not Filing an Assignment Document

A verbal agreement is not official. File a patent assignment to change patent ownership.

Taking Action Before Filing

The assignee shouldn't make or sell the invention before the patent assignment is official. If an error or another problem happens, this could be patent infringement .

Making a Filing Error

Patent assignments are official documents. The assignee's name must be legal and correct. Before filing, check the spelling of the assignee name. If the assignee is a business, confirm the legal name. Many patents have more than one owner. List all names on the assignment.

Misidentifying the Patent

Include as much information about the patent as you can. List the patent number and title. Describe the intellectual property completely.

Not Searching for Security Interests

Patents can be collateral. A bank or another party can file a security interest in a patent, and this can limit how much an assignee can earn from a patent. Check for security interests before filing a patent assignment.

Not Filing a Proprietary Information Agreement

Many businesses file patents, as this is part of a business plan , and it's especially common for startup businesses. Inventorship problems can happen if employees file patents instead of the business.

Often, employees have an obligation to assign inventions to a company. This is true if they developed the invention on the job.

To avoid confusion, require employees to sign a proprietary information agreement. This automatically assigns inventions and designs to the business. Other options include signing an automatic assignment or an explicit assignment. These all clarify patent ownership.

Not Being Notarized

Make sure all official documents concerning your patent are notarized. There is a huge legal advantage to being notarized. It makes it so that your documents will be accepted as correct until it is proven otherwise. If you can't get your documents notarized, gather two witnesses. Have them attest to the signatures.

You have to file a patent assignment within three months of signing the form. If you don't, the assignee could lose ownership rights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Do I Record a Patent Assignment?

If you have a U.S. patent, record your patent assignment with the USPTO. If you have a foreign patent, file with the correct national patent offices.

I Can't Get a Signature from the Inventor. What Happens Now?

First, it needs to be officially established that:

- Whoever is pursuing the application has the right to do so.

- The inventor cannot be reached.

In order to establish this, the patent office will need a copy of the following:

- the employee agreement

- the assignment

- other evidence of the rights

After that, the patent office will continue as if the signature has been obtained, even though it hasn't.

If the inventor has died, the patent office will try to contact the person in charge of managing the deceased's estate or the heir. If the invented refuses to sign or is missing, the patent office will ask for a declaration from the person who is trying to contact them. They will also look at the following items that have been sent to the inventor:

- Do I Have to File a Patent Assignment if the Owner's Name Changed?

No, you don't need a patent assignment if only the person's or company's name changed. If the company merged with another, you may need a patent assignment.

What if I Make a Mistake on My Patent Assignment?

You can't correct a patent assignment. You have to assign it back to the original owner. Then you have to reassign with the correct information.

How Much Does a Patent Assignment Cost?

The patent assignment fee is $25. Filing electronically doesn't cost extra. You do have to pay an additional $40 fee if you file on paper.

Should I Hire a Lawyer?

Yes, you should get a lawyer to help with a patent assignment. A lawyer will make sure there are no filing errors. A lawyer knows how to describe the patent correctly. Errors and bad descriptions can limit the power of a patent assignment. This could cost the assignee a lot of money in future profits and legal fees.

Steps to File a Patent Assignment

1. Fill Out a Recordation Form Cover Shee t

The Recordation Form Cover Sheet is an official USPTO document. This includes the names of the assignor(s) and the assignee(s). It also includes the patent title and number.

2. Complete a Patent Assignment Agreement

The patent assignment agreement should list the assignor(s) and the assignee(s). It should state that the assignor has the right to assign the patent. It should also describe the intellectual property clearly and completely. It should also explain any financial or other transactions that have to take place. This includes a description of the lump sum payment.

3. Sign the Patent Assignment Agreement

All patent owners and assignees must sign the patent assignment agreement.

4. Submit the Patent Assignment

Finally, submit the patent assignment with the USPTO. You have to pay the assignment fee at this time.

If you need help with patent assignments, you can post your question or concern on UpCounsel's marketplace . UpCounsel accepts only the top 5 percent of lawyers to its site. Lawyers on UpCounsel come from law schools such as Harvard Law and Yale Law and average 14 years of legal experience, including work with or on behalf of companies like Google, Menlo Ventures, and Airbnb.

Hire the top business lawyers and save up to 60% on legal fees

Content Approved by UpCounsel

- Brookfield Patent Lawyers

- Jackson Patent Lawyers

- Katy Patent Lawyers

- Kokomo Patent Lawyers

- Providence Patent Lawyers

- Reno Patent Lawyers

- Southaven Patent Lawyers

- How to Sell a Patent

- Patent Assignment Database

- Patent Companies

- Patent Pending Infringement

- Patent Rights

- Patent Attorney

- What Does a Patent Do

- How to File a Patent

- When Can You Say Patent Pending? Everything You Need to Know

- Atlanta Patent Lawyers

- Austin Patent Lawyers

- Boston Patent Lawyers

- Chicago Patent Lawyers

- Dallas Patent Lawyers

- Houston Patent Lawyers

- Los Angeles Patent Lawyers

- New York Patent Lawyers

- Philadelphia Patent Lawyers

- San Francisco Patent Lawyers

- Seattle Patent Lawyers

- Charlotte Patent Lawyers

- Denver Patent Lawyers

- Jacksonville Patent Lawyers

- Las Vegas Patent Lawyers

- Phoenix Patent Lawyers

- Portland Patent Lawyers

- San Antonio Patent Lawyers

- San Diego Patent Lawyers

- San Jose Patent Lawyers

- View All Patent Lawyers

The IP Law Blog

How to perfect a security interest in intellectual property (copyrights, trademarks and patents).

When a creditor provides a loan to a debtor, the debtor will often grant to the creditor a security interest in the debtor’s collateral, including the debtor’s intellectual property. A creditor who receives a security interest in the debtor’s intellectual property, usually by a security agreement, must perfect the security interest so that subsequent purchasers and creditors are on notice of the creditor’s security interest in the collateral. Rules relating to the creation, attachment, perfection and priority of security interests in personal property, including “general intangibles” which include intellectual property, are governed by Division 9 (Secured Transactions) of the California Uniform Commercial Code (“Article 9”), unless federal law preempts Article 9. In order to determine where to perfect a security interest for each type of intellectual property, and since copyrights, trademarks, and patents are all governed by different statutes and case law, it is important to review and analyze not only Article 9 but also the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et. seq. (the “Copyright Act”), the Lanham Trademark Act of 1946, 15 § 1051 et. seq. (the “Lanham Act”), and the Patent Act of 1952, 35 U.S.C. § 101 et. seq . (the “Patent Act”).

1. Article 9 (Secured Transactions – California Uniform Commercial Code)

Article 9, which provides a comprehensive scheme for the regulation of security interests in personal property and fixtures, applies to “a transaction, regardless of its form, that creates a security interest in personal property or fixtures by contract.” California Uniform Commercial Code (“U.C.C.”) §§ 9109(a)(1), 9101 cmt. 1. However, Article 9 does not apply to the extent that a statute, regulation, or treaty of the United States preempts it. Id . § 9109(c)(1). Also, the filing of a financing statement is “not necessary or effective” to perfect a security interest in personal property subject to a “statute, regulation, or treaty of the United States” which provides a national filing system for the perfection of security interests. U.C.C. §§ 9310(b)(3), 9311(a)(1), 9311 cmt. 2. Before analyzing whether the Copyright Act, the Lanham Act, or the Patent Act preempt Article 9 with respect to perfecting a security interest in a copyright, trademark or a patent, as the case may be, it is necessary to review the provisions contained in Article 9 for the creation, attachment, perfection and prioritization of security interests.

- Creation of Security Interest.

A “security interest”—which is an interest in personal property or fixtures which secures payment or performance of an obligation—is created by a “security agreement.” U.C.C. §§ 1201(b)(35), 9102(a)(73). The parties need not draft a separate document entitled “security agreement.” See Komas v. Future Systems , 71 Cal.App.3d 809, 814, 816 (1977). A security agreement is effective according to its terms between the parties, against purchasers of the collateral, and against creditors. U.C.C. § 9201(a). A “security interest” can be created in any “collateral,” which is defined as the property subject to a security interest, including the proceeds to which a security interest attaches. Id . § 9102(a)(12). “General intangibles” is a type of collateral and means any personal property, including things in action, other than types of collateral specifically exempted. Id . § 9202(a)(42). General intangibles include “various categories of intellectual property.” U.C.C. § 9102 Assem. Comm. cmt 5(d).

The security agreement which creates a security interest must sufficiently describe the collateral subject to the security interest, for evidentiary reasons. U.C.C. §§ 9108, 9203, 9108 Assem. Comm. cmt 1. A description of personal or real property in a security agreement is sufficient, whether or not it is specific, if it “reasonably identifies what is described.” U.C.C. § 9108(a). A description of collateral reasonably identifies the collateral if it identifies the collateral by any of the following: (1) specific listing; (2) category; (3) by type of collateral defined throughout the U.C.C., such as general intangibles; (4) quantity; (5) computational or allocational formula or procedure; or (6) any other method, so long as the identity of the collateral is “objectively determinable,” and the description of collateral does not merely state “all the debtor’s assets” or “all the debtor’s personal property.” Id . § 9108(b)-(e). The description of the collateral must “make possible the identification of the collateral described.” Id . §§ 9108, 9108 Assem. Comm. cmt. 2. A security agreement may also create or provide for a security interest in “after-acquired collateral” without requiring the creditor to take any further action—i.e., a “continuing general lien” or “floating lien.” U.C.C. §§ 9204(a), § 9204 cmt. 2.

- Attachment of Security Interest

In order to perfect a security interest in a collateral, the security interest must first attach to the collateral. U.C.C. § 9308(a). A security interest attaches to collateral when it becomes “enforceable against the debtor with respect to the collateral.” Id . § 9203(a). A security interest is enforceable against the debtor and third parties with respect to the collateral only if: (1) value has been given; (2) the debtor has rights in the collateral or the power to transfer rights in the collateral to a secured party, and, (3) the debtor has authenticated (i.e., executed) a security agreement that sufficiently provides a description of the collateral. Id . §§ 9203(b), 9102(a)(7).

- Perfection of Security Interest

Under Article 9, the law of the jurisdiction of the debtor’s location governs the perfection of security interests in both tangible and intangible collateral, whether perfected by filing, automatically (through attachment), possession, or otherwise. U.C.C. §§ 9301, 9301 cmt. 4. A debtor who is an individual is located at the individual’s principal residence. Id . § 9307(b)(1). A registered organization, such as a corporation or a limited liability company, is located in the state under whose law it was organized. Id . §§ 9307(e), 9101 cmt. 4(c). A security interest is perfected if it has attached and if other requirements are met, including the possible filing of a financing statement. Id . §§ 9308(a), 9310(a). However, a financing statement does not need to be filed for security interests that are automatically perfected upon attachment, such as a purchase money security interest in consumer goods, or a sale of a promissory note. Id . §§ 9310(a)(1), 9309(1),(4). Further, a creditor may perfect a security interest in tangible negotiable documents, goods, instruments, money, or tangible chattel paper by taking possession. Id . §§ 9313(a), 9310(a)(6). In fact, a security interest in money may be perfected only by taking possession. Id . § 9312(b)(3). More importantly to this article, the filing of a financing statement is “not necessary or effective” to perfect a security interest in personal property subject to a “statute, regulation, or treaty of the United States whose requirements for a security interest’s obtaining priority over the rights of a lien creditor with respect to the property preempt” the filing provisions contained in Article 9 (i.e., because the federal law provides a national filing system). U.C.C. §§ 9310(b)(3), 9311(a)(1), 9311 cmt. 2. If federal law preempts Article 9 with respect to perfection of a security interest, then a financing statement would not be filed and the creditor would need to record the security interest with the appropriate federal office—i.e., the United States Copyright Office (“Copyright Office”) for filings related to copyrights, and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) for filings related to patents and trademarks. Case law analyzing whether any of the federal statutes preempts Article 9 with respect to perfection of a security interest in a particular intellectual property is discussed below.

i. Financing Statement

If federal law does not preempt Article 9 with re spect to perfecting a security interest in a particular intellectual property, a financing statement must be filed in the office of the Secretary of State, unless the collateral is real-estate-related, in which case a filing should generally be made with the county recorder’s office. U.C.C. § 9501. A financing statement must: (1) provide the name of the debtor; (2) provide the name of the secured party or a representative of the secured party; and (3) indicate the collateral covered by the financing statement. Id . § 9502(a)(1)-(3). The financing statement need not be signed by the debtor. Id . § 9502, cmt. 3. A financing statement sufficiently indicates the collateral that it covers if it provides either (1) a description of the collateral similar to that found in the security agreement as set forth above, or (2) an indication that the financing statement “covers all assets or all personal property.” Id . § 9504. A financing statement is effective for a period of 5 years after the date of filing, unless its effectiveness is continued or terminated. Id . §§ 9513, 9515(a).

ii. Priority

When more than one perfected security interest exists, the security interests rank according to priority in time of filing or perfection. U.C.C. § 9322(a)(1). A perfected security interest has priority over an unperfected security interest. Id . § 9322(a)(2). With respect to unperfected security interests, the first security interest to attach has priority. Id . § 9322(a)(3).

2. Perfecting a Security Interest in Intellectual Property

As a preliminary matter, it should be noted that most courts which have analyzed the proper place to record and perfect a security interest with respect to various types of intellectual property have conducted their analysis under (1) former U.C.C. § 9-104(a) (whether the federal statute governed the rights of parties affected by transactions) and (2) former U.C.C. § 9-302(3)(a) (whether the federal statute provided for national registration or specified a place of filing for a security interest different from that in the former U.C.C.). Under the revised Article 9, the analysis turns to whether the relevant federal statute (1) preempts Article 9 with respect to perfecting a security interest, as set forth in U.C.C. § 9109(c)(1), and (2) provides a national filing system for perfecting security interests, as set forth in U.C.C. § 9311(a)(1)—similar though not entirely the same analysis as was done in the former Article 9. Nonetheless, cases that have been published after the revised Article 9 went into effect have for the most part mirrored their analysis to the former Article 9 standards, and many of the cases have conflated the two issues set forth above into one issue or just analyzed both issues at the same time.

Under the Copyright Act, “copyright protection subsists . . . in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, ” including literary works, musical works, dramatic works, motion pictures and sound recordings. 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The Copyright Act confers upon copyright owners the exclusive rights to reproduce the copyrighted work, prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work and distribute copies of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership. Id . § 106(1)-(3).

The Copyright Act provides that any “ transfer of copyright ownership or other document pertaining to a copyright” may be recorded in the Copyright Office, and further defines a “transfer of copyright ownership” as “an assignment, mortgage, exclusive license, or any other conveyance, alienation, or hypothecation of a copyright or of any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright.” 17 U.S.C. §§ 101, 205(a) (emphasis added). A “hypothecation” means the “‘pledging of something as security without delivery of title or possession.’” Moldo v. Matsco, Inc. ( In re Cybernetic Servs., Inc. ), 252 F.3d 1039, 1056 (9th Cir. 2001), cert. denied , 534 U.S. 1130 (2002) ( quoting Black’s Law Dictionary 747 (7 th ed. 1999)).

Because 17 U.S.C. § 205(a) covers assignments and hypothecations of copyrights (i.e., security interests), it establishes a uniform method for recording security interests in copyrights and preempts Article 9 with respect to perfecting security interests in registered copyrights. Nat’l Peregrine, Inc. v. Capitol Fed. Sav. & Loan ( In re Peregrine Entm’t, Ltd .), 116 B.R. 194, 200-204 (C.D. Cal. 1990). Accordingly, the proper method for perfecting a security interest in a registered copyright is recording the security interest with the Copyright Office in order to give “all persons constructive notice of the facts stated in the recorded document,” rather than filing a financing statement under Article 9. Id . (quoting 17 U.S.C. § 205(c)); see also Aerocon Eng’g, Inc. v. Silicon Valley Bank ( In re World Auxiliary Power Co. ), 303 F.3d 1120, 1128 (9 th Cir. 2002); Morgan Creek Prods., Inc. v. Franchise Pictures LLC ( In re Franchise Pictures LLC ), 389 B.R. 131, 142 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 2008); In re Avalon Software Inc. , 209 B.R. 517 (Bankr. D. Ariz. 1997). However, the perfection of an unregistered copyright must be done by filing a financing statement with the Secretary of State pursuant to Article 9—not by recording the security interest in the unregistered copyright with the Copyright Office. In re: World Auxiliary Power Company , 303 F.3d at 1128.

The Lanham Act defines a trademark to mean “any word, name, symbol, or device or any combination thereof” used by any person “to identify and distinguish his or her goods . . . from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods.” 15 U.S.C. § 1127. The Lanham Act also provides registered trademark owners protection against any person who, without the trademark holder’s consent, uses the mark in connection with the sale, distribution or advertising of any goods or services, where such use is likely to cause confusion, mistake, or deception. Id . §§ 1125(a), 1141(1).

The Lanham Act provides that an “assignment shall be void against any subsequent purchaser for valuable consideration without notice, unless the prescribed information reporting the assignment is recorded in the United States Patent and Trademark Office within 3 months after the date of the assignment or prior to the subsequent purchase.” 15 U.S.C. § 1060(a)(4). Unlike the Copyright Act—which governs filings both with respect to assignments and transfer of security interests—the Lanham Act provides only for the recording of an assignment of a trademark with the USPTO, which does not include pledges, mortgages or hypothecation of trademarks. Joseph v. Valencia, Inc. ( In re 199Z, Inc .), 137 B.R. 778, 782 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 1992) ; 15 U.S.C. § 1060(a)(4).

Trademark cases distinguish between security interests and assignments. Roman Cleanser Co. v. Nat’l Acceptance Co. of Am. ( In re Roman Cleanser Co .), 43 B.R. 940, 944 (Bankr. E.D. Mich. 1984), aff’d , 802 F.2d 207 (6th Cir. 1986) . While a trademark assignment is an absolute transfer of the entire right, title and interest in and to the trademark, the grant of a security interest is not such a transfer. Id . Rather, the grant of a security interest is merely “a device to secure an indebtedness,” or “a mere agreement to assign in the event of a default by the debtor.” Id . Given that the Lanham Act only covers assignments of trademarks and the fact that a security interest in a trademark is not equivalent to an assignment, the filing of a security interest is not covered by the Lanham Act. Id . Thus, the Lanham Act does not preempt Article 9 and the manner of perfecting a security interest in trademarks is governed by Article 9, which means that the secured creditor must file a financing statement with the Secretary of State to perfect the security interest in the trademark. E.g., In re Roman Cleanser Co ., 43 B.R. at 944; In re 199Z, Inc., 137 B.R. at 782 (holding that secured party cannot perfect security interest in trademark by recording with the USTPO); Trimarchi v. Together Dev. Corp ., 255 B.R. 606, 610-11 (D. Mass. 2000) (holding that the Lanham Act does not preempt Article 9); In re Together Dev. Corp ., 227 B.R. 439 (holding that filing of security interest with the USPTO failed to perfect security interest); I n re Chattanooga Choo-Choo Co., 98 B.R. 792 (Bankr. E.D. Tenn. 1989) (holding that the U.C.C., not the Lanham Act, governs recordation of security interests in trademarks); Creditors’ Comm. of TR-3 Indus., Inc. v. Capital Bank ( In re TR-3 Indus .), 41 B.R. 128 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 1984) . Arguably, if Congress intended to provide a means for recording security interests in registered trademarks—in addition to recording assignments of trademarks—it would have done so, as it did in the Copyright Act with respect to recording security interests in registered copyrights . In re Roman Cleanser Co ., 43 B.R. at 944; In re 199Z, Inc., 137 B.R. at 782.

Nonetheless, although cases uniformly suggest that a security interest in a trademark must be perfected by filing a financing statement with the Secretary of State of the state in which the debtor is located, it is recommended that a recording or filing also be made with the USPTO, especially since the USPTO has no authority to refuse to record a filed document on the ground that it is not a valid assignment. In re Ellison Publications, Inc. , 182 U.S.P.Q. 498, 1974 WL 19944 (Comm’r Pat. & Trademarks 1974). Filing a financing statement with the Secretary of State and recording the security interest with the USPTO will ensure that lien creditors and subsequent lenders and purchasers are all on notice of the security interests.

On a related note, when recording an assignment of a trademark in the USPTO, a creditor should make sure that the trademark is assigned together “with the goodwill of the business in which the mark is used.” 15 U.S.C. § 1060. Because a trademark is merely a symbol of goodwill and it has no independent significance apart from the goodwill it symbolizes, it cannot be sold or assigned apart from the goodwill it symbolizes. Marshak v. Green, 746 F.2d 927 (2d Cir. 1984). A sale of a trademark without its goodwill is an “assignment in gross” and is not a valid assignment. 1 J.

Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition , § 18:3 (4th ed. 1996).

The Patent Act grants inventors and discoverers of “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” the right to obtain a patent, which must be novel and nonobvious. 35 U.S.C. §§ 101-103. The Patent Act protects the inventor or discoverer of the patent who applies for and pursues the patent from infringers who use or sell the patented invention without authority. 35 U.S.C. § 271(a).