What Works In Schools : Sexual Health Education

CDC’s What Works In Schools Program improves the health and well-being of middle and high school students by:

- Improving health education,

- Connecting young people to the health services they need, and

- Making school environments safer and more supportive.

What is sexual health education?

Quality provides students with the knowledge and skills to help them be healthy and avoid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), sexually transmitted infections (STI) and unintended pregnancy.

A quality sexual health education curriculum includes medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, and culturally relevant content and skills that target key behavioral outcomes and promote healthy sexual development. 1

The curriculum is age-appropriate and planned across grade levels to provide information about health risk behaviors and experiences.

Sexual health education should be consistent with scientific research and best practices; reflect the diversity of student experiences and identities; and align with school, family, and community priorities.

Quality sexual health education programs share many characteristics. 2-4 These programs:

- Are taught by well-qualified and highly-trained teachers and school staff

- Use strategies that are relevant and engaging for all students

- Address the health needs of all students, including the students identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ)

- Connect students to sexual health and other health services at school or in the community

- Engage parents, families, and community partners in school programs

- Foster positive relationships between adolescents and important adults.

How can schools deliver sexual health education?

A school health education program that includes a quality sexual health education curriculum targets the development of functional knowledge and skills needed to promote healthy behaviors and avoid risks. It is important that sexual health education explicitly incorporate and reinforce skill development.

Giving students time to practice, assess, and reflect on skills taught in the curriculum helps move them toward independence, critical thinking, and problem solving to avoid STIs, HIV, and unintended pregnancy. 5

Quality sexual health education programs teach students how to: 1

- Analyze family, peer, and media influences that impact health

- Access valid and reliable health information, products, and services (e.g., STI/HIV testing)

- Communicate with family, peers, and teachers about issues that affect health

- Make informed and thoughtful decisions about their health

- Take responsibility for themselves and others to improve their health.

What are the benefits of delivering sexual health education to students?

Promoting and implementing well-designed sexual health education positively impacts student health in a variety of ways. Students who participate in these programs are more likely to: 6-11

- Delay initiation of sexual intercourse

- Have fewer sex partners

- Have fewer experiences of unprotected sex

- Increase their use of protection, specifically condoms

- Improve their academic performance.

In addition to providing knowledge and skills to address sexual behavior , quality sexual health education can be tailored to include information on high-risk substance use * , suicide prevention, and how to keep students from committing or being victims of violence—behaviors and experiences that place youth at risk for poor physical and mental health and poor academic outcomes.

*High-risk substance use is any use by adolescents of substances with a high risk of adverse outcomes (i.e., injury, criminal justice involvement, school dropout, loss of life). This includes misuse of prescription drugs, use of illicit drugs (i.e., cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, or ecstasy), and use of injection drugs (i.e., drugs that have a high risk of infection of blood-borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis).

What does delivering sexual health education look like in action?

To successfully put quality sexual health education into practice, schools need supportive policies, appropriate content, trained staff, and engaged parents and communities.

Schools can put these four elements in place to support sex ed.

- Implement policies that foster supportive environments for sexual health education.

- Use health content that is medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, culturally inclusive, and grounded in science.

- Equip staff with the knowledge and skills needed to deliver sexual health education.

- Engage parents and community partners.

Include enough time during professional development and training for teachers to practice and reflect on what they learned (essential knowledge and skills) to support their sexual health education instruction.

By law, if your school district or school is receiving federal HIV prevention funding, you will need an HIV Materials Review Panel (HIV MRP) to review all HIV-related educational and informational materials.

This review panel can include members from your School Health Advisory Councils, as shared expertise can strengthen material review and decision making.

For More Information

Learn more about delivering quality sexual health education in the Program Guidance .

Check out CDC’s tools and resources below to develop, select, or revise SHE curricula.

- Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (HECAT), Module 6: Sexual Health [PDF – 70 pages] . This module within CDC’s HECAT includes the knowledge, skills, and health behavior outcomes specifically aligned to sexual health education. School and community leaders can use this module to develop, select, or revise SHE curricula and instruction.

- Developing a Scope and Sequence for Sexual Health Education [PDF – 17 pages] .This resource provides an 11-step process to help schools outline the key sexual health topics and concepts (scope), and the logical progression of essential health knowledge, skills, and behaviors to be addressed at each grade level (sequence) from pre-kindergarten through the 12th grade. A developmental scope and sequence is essential to developing, selecting, or revising SHE curricula.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool, 2021 , Atlanta: CDC; 2021.

- Goldfarb, E. S., & Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: The case for comprehensive sex education. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 13-27.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum .

- Pampati, S., Johns, M. M., Szucs, L. E., Bishop, M. D., Mallory, A. B., Barrios, L. C., & Russell, S. T. (2021). Sexual and gender minority youth and sexual health education: A systematic mapping review of the literature. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (6), 1040-1052.

- Szucs, L. E., Demissie, Z., Steiner, R. J., Brener, N. D., Lindberg, L., Young, E., & Rasberry, C. N. (2023). Trends in the teaching of sexual and reproductive health topics and skills in required courses in secondary schools, in 38 US states between 2008 and 2018. Health Education Research , 38 (1), 84-94.

- Coyle, K., Anderson, P., Laris, B. A., Barrett, M., Unti, T., & Baumler, E. (2021). A group randomized trial evaluating high school FLASH, a comprehensive sexual health curriculum. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (4), 686-695.

- Marseille, E., Mirzazadeh, A., Biggs, M. A., Miller, A. P., Horvath, H., Lightfoot, M.,& Kahn, J. G. (2018). Effectiveness of school-based teen pregnancy prevention programs in the USA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 19(4), 468-489.

- Denford, S., Abraham, C., Campbell, R., & Busse, H. (2017). A comprehensive review of reviews of school-based interventions to improve sexual-health. Health psychology review, 11(1), 33-52.

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med 2012;42(3):272–94.

- Mavedzenge SN, Luecke E, Ross DA. Effective approaches for programming to reduce adolescent vulnerability to HIV infection, HIV risk, and HIV-related morbidity and mortality: A systematic review of systematic reviews. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:S154–69.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- Confidentiality in the Care of Adolescents: Policy Statement

- Confidentiality in the Care of Adolescents: Technical Report

- AAP Policy Offers Recommendations to Safeguard Teens’ Health Information

- One-on-One Time with the Pediatrician

- American Academy of Pediatrics Releases Guidance on Maintaining Confidentiality in Care of Adolescents

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Early Relational Health

- Early Childhood Health & Development

- Safe Storage of Firearms

- Promoting Firearm Injury Prevention

- Mental Health Education & Training

- Practice Tools & Resources

- Policies on Mental Health

- Mental Health Resources for Families

The Importance of Access to Comprehensive Sex Education

Comprehensive sex education is a critical component of sexual and reproductive health care.

Developing a healthy sexuality is a core developmental milestone for child and adolescent health.

Youth need developmentally appropriate information about their sexuality and how it relates to their bodies, community, culture, society, mental health, and relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners.

AAP supports broad access to comprehensive sex education, wherein all children and adolescents have access to developmentally appropriate, evidence-based education that provides the knowledge they need to:

- Develop a safe and positive view of sexuality.

- Build healthy relationships.

- Make informed, safe, positive choices about their sexuality and sexual health.

Comprehensive sex education involves teaching about all aspects of human sexuality, including:

- Cyber solicitation/bullying.

- Healthy sexual development.

- Body image.

- Sexual orientation.

- Gender identity.

- Pleasure from sex.

- Sexual abuse.

- Sexual behavior.

- Sexual reproduction.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- Abstinence.

- Contraception.

- Interpersonal relationships.

- Reproductive coercion.

- Reproductive rights.

- Reproductive responsibilities.

Comprehensive sex education programs have several common elements:

- Utilize evidence-based, medically accurate curriculum that can be adapted for youth with disabilities.

- Employ developmentally appropriate information, learning strategies, teaching methods, and materials.

- Human development , including anatomy, puberty, body image, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

- Relationships , including families, peers, dating, marriage, and raising children.

- Personal skills , including values, decision making, communication, assertiveness, negotiation, and help-seeking.

- Sexual behavior , including abstinence, masturbation, shared sexual behavior, pleasure from esx, and sexual dysfunction across the lifespan.

- Sexual health , including contraception, pregnancy, prenatal care, abortion, STIs, HIV and AIDS, sexual abuse, assault, and violence.

- Society and culture , including gender roles, diversity, and the intersection of sexuality and the law, religion, media, and the arts.

- Create an opportunity for youth to question, explore, and assess both personal and societal attitudes around gender and sexuality.

- Focus on personal practices, skills, and behaviors for healthy relationships, including an explicit focus on communication, consent, refusal skills/accepting rejection, violence prevention, personal safety, decision making, and bystander intervention.

- Help youth exercise responsibility in sexual relationships.

- Include information on how to come forward if a student is being sexually abused.

- Address education from a trauma-informed, culturally responsive approach that bridges mental, emotional, and relational health.

Comprehensive sex education should occur across the developmental spectrum, beginning at early ages and continuing throughout childhood and adolescence :

- Sex education is most effective when it begins before the initiation of sexual activity.

- Young children can understand concepts related to bodies, gender, and relationships.

- Sex education programs should build an early foundation and scaffold learning with developmentally appropriate content across grade levels.

- AAP Policy outlines considerations for providing developmentally appropriate sex education throughout early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

Most adolescents report receiving some type of formal sex education before age 18. While sex education is typically associated with schools, comprehensive sex education can be delivered in several complementary settings:

- Schools can implement comprehensive sex education curriculum across all grade levels

- The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) provides guidelines for providing developmentally appropriate comprehensive sex education across grades K-12.

- Pediatric health clinicians and other health care providers are uniquely positioned to provide longitudinal sex education to children, adolescents, and young adults.

- Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents outlines clinical considerations for providing comprehensive sex education at all developmental stages, as a part of preventive health care.

- Research suggests that community-based organizations should be included as a source for comprehensive sexual health promotion.

- Faith-based communities have developed sex education curricula for their congregations or local chapters that emphasize the moral and ethical aspects of sexuality and decision-making.

- Parents and caregivers can serve as the primary sex educators for their children, by teaching fundamental lessons about bodies, development, gender, and relationships.

- Many factors impact the sex education that youth receive at home, including parent/caregiver knowledge, skills, comfort, culture, beliefs, and social norms.

- Virtual sex education can take away feelings of embarrassment or stigma and can allow for more youth to access high quality sex education.

Comprehensive sex education provides children and adolescents with the information that they need to:

- Understand their body, gender identity, and sexuality.

- Build and maintain healthy and safe relationships.

- Engage in healthy communication and decision-making around sex.

- Practice healthy sexual behavior.

- Understand and access care to support their sexual and reproductive health.

Comprehensive sex education programs have demonstrated success in reducing rates of sexual activity, sexual risk behaviors, STIs, and adolescent pregnancy and delaying sexual activity. Many systematic reviews of the literature have indicated that comprehensive sex education promotes healthy sexual behaviors:

- Reduced sexual activity.

- Reduced number of sexual partners.

- Reduced frequency of unprotected sex.

- Increased condom use.

- Increased contraceptive use.

However, comprehensive sex education curriculum goes beyond risk-reduction, by covering a broader range of content that has been shown to support social-emotional learning, positive communication skills, and development of healthy relationships.

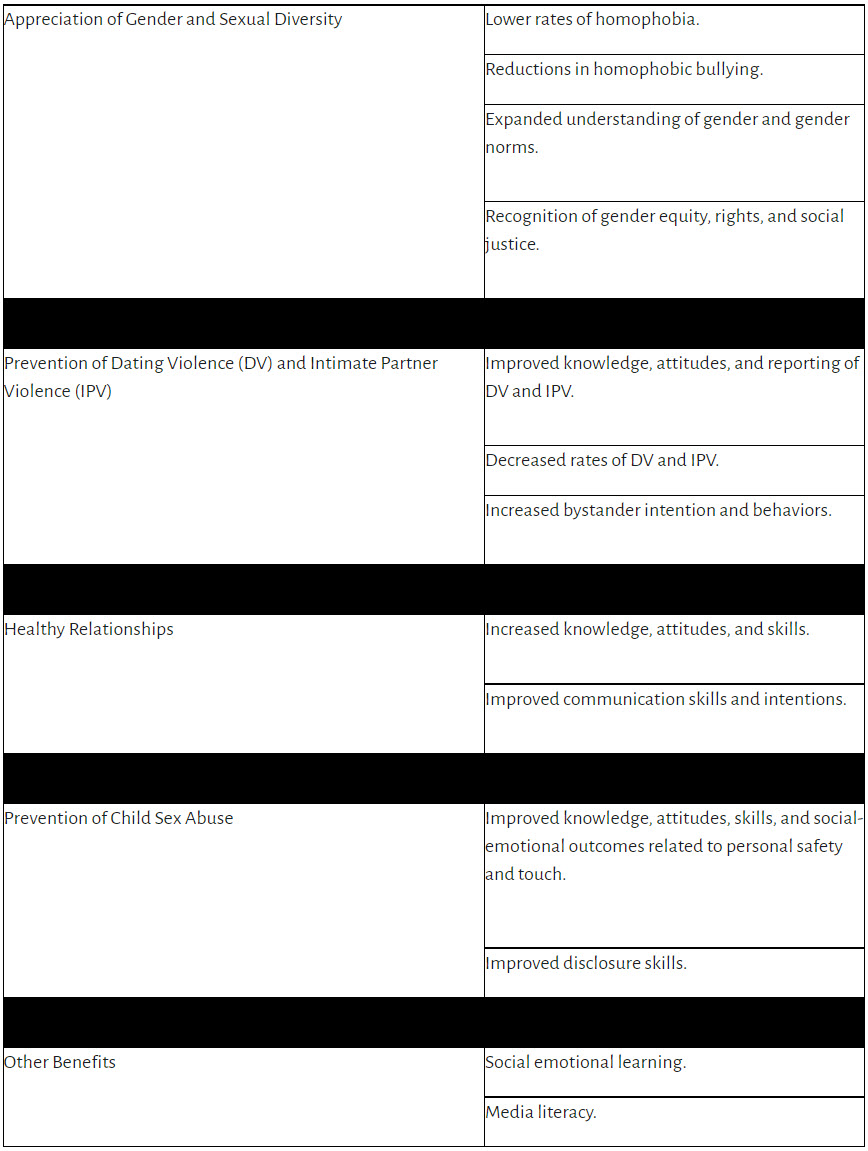

A 2021 review of the literature found that comprehensive sex education programs that use a positive, affirming, and inclusive approach to human sexuality are associated with concrete benefits across 5 key domains:

Benefits of comprehensive sex education programs

When children and adolescents lack access to comprehensive sex education, they do not get the information they need to make informed, healthy decisions about their lives, relationships, and behaviors.

Several trends in sexual health in the US highlight the need for comprehensive sex education for all youth.

Education about condom and contraceptive use is needed:

- 55% of US high school students report having sexual intercourse by age 18 .

- Self-reported condom use has decreased significantly among high school students.

- Only 9% of sexually active high school students report using both a condom for STI-prevention and a more effective form of birth control to prevent pregnancy .

STI prevention is needed:

- Adolescents and young adults are disproportionately impacted by STIs.

- Cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are rising rapidly among young people.

- When left untreated , these infections can lead to infertility, adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, and increased risk of acquiring new STIs.

- Youth need comprehensive, unbiased information about STI prevention, including human papillomavirus (HPV) .

Continued prevention of unintended pregnancy is needed:

- Overall US birth rates among adolescent mothers have declined over the last 3 decades.

- There are significant geographic disparities in adolescent pregnancy rates, with higher rates of pregnancy in rural counties and in southern and southwestern states.

- Social drivers of health and systemic inequities have caused racial and ethnic disparities in adolescent pregnancy rates.

- Eliminating disparities in adolescent pregnancy and birth rates can increase health equity, improve health and life outcomes, and reduce the economic impact of adolescent parenting.

Misinformation about sexual health is easily available online:

- Internet use is nearly universal among US children and adolescents.

- Adolescents report seeking sexual health information online .

- Sexual health websites that adolescents visit can contain inaccurate information .

Prevention of sex abuse, dating violence, and unhealthy relationships is needed:

- Child sexual abuse is common: 25% of girls and 8% of boys experience sexual abuse during childhood .

- Youth who experience sexual abuse have long-term impacts on their physical, mental, and behavioral health.

- 1 in 11 female and 1 in 14 male students report physical DV in the last year .

- 1 in 8 female and 1 in 26 male students report sexual DV in the last year .

- Youth who experience DV have higher rates of anxiety, depression, substance use, antisocial behaviors, and suicide risk.

The quality and content of sex education in US schools varies widely.

There is significant variation in the quality of sex education taught in US schools, leading to disparities in attitudes, health information, and outcomes. The majority of sex education programs in the US tend to focus on public health goals of decreasing unintended pregnancies and preventing STIs, via individual behavior change.

There are three primary categories of sex educational programs taught in the US :

- Abstinence-only education , which teaches that abstinence is expected until marriage and typically excludes information around the utility of contraception or condoms to prevent pregnancy and STIs.

- Abstinence-plus education , which promotes abstinence but includes information on contraception and condoms.

- Comprehensive sex education , which provides medically accurate, age-appropriate information around development, sexual behavior (including abstinence), healthy relationships, life and communication skills, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

State laws impact the curriculum covered in sex education programs. According to a report from the Guttmacher Institute :

- 26 US states and Washington DC mandate sex education and HIV education.

- 18 states require that sex education content be medically accurate.

- 39 states require that sex education programs provide information on abstinence.

- 20 states require that sex education programs provide information on contraception.

US states have varying requirements on sex education content related to sexual orientation :

- 10 states require sex education curriculum to include affirming content on LGBTQ2S+ identities or discussion of sexual health for youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- 7 states have sex education curricular requirements that discriminate against individuals who are LGBTQ2S+.Youth who live in these states may face additional barriers to accessing sexual health information.

Abstinence-only sex education programs do not meet the needs of children and adolescents.

While abstinence is 100% effective in preventing pregnancy and STIs, research has conclusively shown that abstinence-only sex education programs do not support healthy sexual development in youth.

Abstinence-only programs are ineffective in reaching their stated goals, as evidenced by the data below:

- Abstinence-only programs are unsuccessful in delaying sex until marriage .

- Abstinence-only sex education programs do not impact the rates of pregnancy, STIs, or HIV in adolescents .

- Youth who take a “virginity pledge” as part of abstinence-only education programs have the same rates of premarital sex as their peers who do not take pledges, but are less likely to use contraceptives .

- US states that emphasize abstinence-only education have higher rates of adolescent pregnancy and birth .

Abstinence-only programs can harm the healthy sexual and mental development of youth by:

- Withholding information or providing inaccurate information about sexuality and sexual behavior .

- Contributing to fear, shame, and stigma around sexual behaviors .

- Not sharing information on contraception and barrier protection or overstating the risks of contraception .

- Utilizing heteronormative framing and stigma or discrimination against students who are LGBTQ2S+ .

- Reinforcing harmful gender stereotypes .

- Ignoring the needs of youth who are already sexually active by withholding education around contraception and STI prevention.

Abstinence-plus sex education programs focus solely on decreasing unintended pregnancy and STIs.

Abstinence-plus sex education programs promote abstinence until marriage. However, these programs also provide information on contraception and condom use to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs.

Research has demonstrated that abstinence-plus programs have an impact on sexual behavior and safety, including:

- HIV prevention.

- Increase in condom use .

- Reduction in number of sexual partners .

- Delay in initiation of sexual behavior .

While these programs add another layer of education, they do not address the broader spectrum of sexuality, gender identity, and relationship skills, thus withholding critical information and skill-building that can impact healthy sexual development.

AAP and other national medical and public health associations support comprehensive sex education for youth.

Given the evidence outlined above, AAP and other national medical organizations oppose abstinence-only education and endorse comprehensive sex education that includes both abstinence promotion and provision of accurate information about contraception, STIs, and sexuality.

National medical and public health organizations supporting comprehensive sex education include:

- American Academy of Pediatrics .

- American Academy of Family Physicians.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists .

- American Medical Association .

- American Public Health Association .

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine .

Pediatric clinics provide a unique opportunity for comprehensive sex education.

Pediatric health clinicians typically have longitudinal care relationships with their patients and families, and thus have unique opportunities to address comprehensive sex education across all stages of development.

The clinical visit can serve as a useful adjunct to support comprehensive sex education provided in schools, or to fill gaps in knowledge for youth who are exposed to abstinence-only or abstinence-plus curricula.

AAP policy and Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents provide recommendations for comprehensive sex education in clinical settings, including:

- Encouraging parent-child discussions on sexuality, contraception, and internet/media use.

- Understanding diverse experiences and beliefs related to sexuality and sex education and meeting the unique needs of individual patients and families.

- Including discussions around healthy relationships, dating violence, and intimate partner violence in clinical care.

- Discussing methods of contraception and STI/HPV prevention prior to onset of sexual intercourse.

- Providing proactive and developmentally appropriate sex education to all youth, including children and adolescents with special health care needs.

Perspective

Karen Torres, Youth activist

There were two cardboard bears, and a person explained that one bear wears a bikini to the beach and the other bear wears shorts – that is the closest thing I ever got to sex ed throughout my entire K-12 education. I often think about that bear lesson because it was the day our institutions failed to teach me anything about my body, relationships, consent, and self-advocacy, which became even more evident after I was sexually assaulted at 16 years old. My story is not unique, I know that many young people have been through similar traumas, but many of us were also subjected to days, months, and years of silence and embarrassment because we were never given the knowledge to know how to spot abuse or the language to ask for help. Comprehensive sex ed is so much more than people make it out to be, it teaches about sex but also about different types of experiences, how to respect one another, how to communicate in uncomfortable situations, how to ask for help and an insurmountable amount of other valuable lessons.

From these lessons, people become well-rounded, people become more empathetic to other experiences, and people become better. I believe comprehensive sex ed is vital to all people and would eventually work as a part to build more compassionate communities.

Many US children and adolescents do not receive comprehensive sex education; and rates of formal sex education have declined significantly in recent decades.

Barriers to accessing comprehensive sex education include:

Misinformation, stigma, and fear of negative reactions:

- Misinformation and stigma about the content of sex education curriculum has been the primary barrier to equitable access to comprehensive sex education in schools for decades .

- Despite widespread parental support for sex education in schools, fears of negative public/parent reactions have led school administrators to limit youth access to the information they need to make healthy decisions about their sexuality for nearly a half-century.

- In recent years, misinformation campaigns have spread false information about the framing and content of comprehensive sex education programs, causing debates and polarization at school board meetings .

- Nearly half of sex education teachers report that concerns about parent, student, or administrator responses are a barrier to provision of comprehensive sex education.

- Opponents of comprehensive sex education often express concern that this education will lead youth to have sex; however, research has demonstrated that this is not the case . Instead, comprehensive sex ed is associated with delays in initiation of sexual behavior, reduced frequency of sexual intercourse, a reduction in number of partners, and an increase in condom use.

- Some populations of youth lack access to comprehensive sex education due to a societal belief that they are asexual, in need of protection, or don’t need to learn about sex. This barrier particularly impacts youth with disabilities or special health care needs .

- Sex ed curricula in some schools perpetuate gender/sex stereotypes, which could contribute to negative gender stereotypes and negative attitudes towards sex .

Inconsistencies in school-based sex education:

- There is significant variation in the content of sex education taught in schools in the US, and many programs that carry the same label (eg, “abstinence-plus”) vary widely in curriculum.

- While decisions about sex education curriculum are made at the state level, the federal government has provided funding to support abstinence-only education for decades , which incentivizes schools to use these programs.

- Since 1996, more than $2 billion in federal funds have been spent to support abstinence-only sex education in schools.

- 34 US states require schools to use abstinence-only curriculum or emphasize abstinence as the main way to avoid pregnancy and STIs.

- Only 16 US states require instruction on condoms or contraception.

- It is not standard to include information on how to come forward if a student is being sexually abused, and many schools do not have a process for disclosures made.

- Because of this, abstinence-only programs are commonly used in US schools, despite overwhelming evidence that they are ineffective in delaying sexual behavior until marriage, and withhold critical information that youth need for healthy sexual and relationship development.

Need for resources and training:

- Integration of comprehensive sex education into school curriculum requires financial resources to strengthen and expand evidence-based programs.

- Successful implementation of comprehensive sex education requires a trained workforce of teachers who can address the curriculum in age-appropriate ways for students in all grade-levels.

- Education, training, and technical assistance are needed to support pediatric health clinicians in addressing comprehensive sex education in clinical settings, as a complement to school-based education.

Lack of diversity and cultural awareness in curricula:

- A history of systemic racism, discrimination, and long-standing health, social and systemic inequities have created racial and ethnic disparities in access to sexual health services and representation in sex education materials. The legacy of intergenerational trauma in the medical system should be acknowledged in sex education curricula.

- Sex education curriculum is often centered on a white audience, and does not address or reflect the role of systemic racism in sexuality and development .

- Traditional abstinence-focused sex education programs have a heteronormative focus and do not address the unique needs of youth who are LGBTQ2S+ .

- Sex education programs often do not address reproductive body diversity, the needs of those with differences in sex development, and those who identify as intersex .

- Sex education programs often do not reflect the unique needs of youth with disabilities or special health care needs .

- Sex education programs are often not tailored to meet the religious considerations of faith communities.

- There is a need for sex education programs designed to help youth navigate sexual health and development in the context of their own culture and community .

Disparities in access to comprehensive sex education.

The barriers listed above limit access to comprehensive sex education in schools and communities. While these barriers impact youth across the US, there are some populations who are less likely to have access to comprehensive to sex education.

Youth who are LGBTQ2S+:

- Only 8% of students who are LGBTQ2S+ report having received sexual education that was inclusive .

- Students who are LGBTQ2S+ are 50% more likely than their peers who are heterosexual to report that sex education in their schools was not useful to them .

- Only 13% of youth who are bisexual+ and 10% of youth who are transgender and gender expansive report receiving sex education in schools that felt personally relevant.

- Only 20% of youth who are Black and LGBTQ2S+ and 13% of youth who are Latinx and LGBTQ2S+ report receiving sex education in schools that felt personally relevant.

- Only 10 US states require affirming content on LGBTQ2S+ relationships in sex education curriculum.

Youth with disabilities or special health care needs:

- Youth with disabilities or special health care needs have a particular need for comprehensive sex education, as these youth are less likely to learn about sex or sexuality form their parents , healthcare providers , or peer groups .

- In a national survey, only half of youth with disabilities report that they have participated in sex education .

- Typical sex education may not be sufficient for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder, and special methods and curricula are necessary to match their needs .

- Lack the desire or maturity for romantic or sexual relationships.

- Are not subject to sexual abuse.

- Do not need sex education.

- Only 3 states explicitly include youth with disabilities within their sex education requirements.

Youth from historically underserved communities:

- Students who are Black in the US are more likely than students who are white to receive abstinence-only sex education , despite significant support from parents and students who are Black for comprehensive sex education.

- Youth who are Black and female are less likely than peers who are white to receive education about where to obtain birth control prior to initiating sexual activity.

- Youth who are Black and male and Hispanic are less likely than their peers who are white to receive formal education on STI prevention or contraception prior to initiating sexual activity.

- Youth who are Hispanic and female are less likely to receive instruction about waiting to have sex than youth of other ethnicities.

- Tribal health educators report challenges in identifying culturally relevant sex education curriculum for youth who are American Indian/Alaska Native.

- In a 2019 study, youth who were LGBTQ2S+ and Black, Latinx, or Asian reported receiving inadequate sex education due to feeling unrepresented, unsupported, stigmatized, or bullied.

- In survey research, many young adults who are Asian American report that they received inadequate sex education in school.

Youth from rural communities:

- Adolescents who live in rural communities have faced disproportionate declines in formal sex education over the past two decades, compared with peers in urban/suburban areas.

- Students who live in rural communities report that the sex education curriculum in their schools does not serve their needs .

Youth from communities and schools that are low-income:

- Data has shown an association between schools that are low-resource and lower adolescent sexual health knowledge, due to a combination of fewer school resources and higher poverty rates/associated unmet health needs in the student body.

- Youth with family incomes above 200% of the federal poverty line are more likely to receive education about STI prevention, contraception, and “saying no to sex,” than their peers below 200% of the poverty line.

Youth who receive sex education in some religious settings:

- Most adolescents who identify as female and who attended church-based sex education programs report instructions on waiting until marriage for sex, while few report receiving education about birth control.

- Young people who received sex education in religious schools report that education focused on the risks of sexual behavior (STIs, pregnancy) and religious guilt; leading to them feeling under-equipped to make informed decisions about sex and sexuality later in life.

- Youth and teachers from religious schools have identified a need for comprehensive sex education curriculum that is tailored to the needs of faith communities .

Youth who live in states that limit the topics that can be covered in sex education:

- Students who live in the 34 states that require sex education programs to stress abstinence are less likely to have access to critical information on STI prevention and contraception.

- Prohibitions on addressing abortion in sex education or mandates that sex education curricula include medically inaccurate information on abortion designed to dissuade youth from terminating a pregnancy.

- Limitations on the types of contraception that can be covered in sex education curricula.

- Requirements that sex education teachers promote heterosexual, monogamous marriage in sex education.

- Lack of requirements to address healthy relationships and communication skills.

- Lack of requirements for teacher training or certification.

Comprehensive sex education has significant benefits for children and adolescents.

Youth who are exposed to comprehensive sex education programs in school demonstrate healthier sexual behaviors:

- Increased rates of contraception and condom use.

- Fewer unplanned pregnancies.

- Lower rates of STIs and HIV.

- Delayed initiation of sexual behavior.

More broadly, comprehensive sexual education impacts overall social-emotional health , including:

- Enhanced understanding of gender and sexuality.

- Lower rates of homophobia and related bullying.

- Lower rates of dating violence, intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and child sexual abuse.

- Healthier relationships and communication skills.

- Understanding of reproductive rights and responsibilities.

- Improved social-emotional learning, media literacy, and academic achievement.

Comprehensive sex education curriculum goes beyond risk reduction, to ensure that youth are supported in understanding their identity and sexuality and making informed decisions about their relationships, behaviors, and future. These benefits are critical to healthy sexual development.

Impacts of a lack of access to comprehensive sex education.

When youth are denied access to comprehensive sex education, they do not get the information and skill-building required for healthy sexual development. As such, they face unnecessary barriers to understanding their gender and sexuality, building positive interpersonal relationships, and making informed decisions about their sexual behavior and sexual health.

Impacts of a lack of comprehensive sex education for all youth can include :

- Less use of condoms, leading to higher risk of STIs, including HIV.

- Less use of contraception, leading to higher risk of unplanned pregnancy.

- Less understanding and increased stigma and shame around the spectrum of gender and sexual identity.

- Perpetuated stigma and embarrassment related to sex and sexual identity.

- Perpetuated gender stereotypes and traditional gender roles.

- Higher rates of youth turning to unreliable sources for information about sex, including the internet, the media, and informal learning from peer networks.

- Challenges in interpersonal communication.

- Challenges in building, maintaining, and recognizing safe, healthy peer and romantic relationships.

- Lower understanding of the importance of obtaining and giving enthusiastic consent prior to sexual activity.

- Less awareness of appropriate/inappropriate touch and lower reporting of child sexual abuse.

- Higher rates of dating violence and intimate partner violence, and less intervention from bystanders.

- Higher rates of homophobia and homophobic bullying.

- Unsafe school environments.

- Lower rates of media literacy.

- Lower rates of social-emotional learning.

- Lower recognition of gender equity, rights, and social justice.

In addition, the lack of access to comprehensive sex education can exacerbate existing health disparities, with disproportionate impacts on specific populations of youth.

Youth who identify as women, youth from communities of color, youth with disabilities, and youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are particularly impacted by inequitable access to comprehensive sex education, as this lack of education can impact their health, safety, and self-identity. Examples of these impacts are outlined below.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm young women.

- Female bodies are more prone to STI infection and more likely to experience complications of STI infection than male bodies.

- Female bodies are disproportionately impacted by long-term health consequences of STIs , including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.

- Female bodies are less likely to have or recognize symptoms of certain STI infections .

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common STI in young women , and can cause long-term health consequences such as genital warts and cervical cancer.

- Women bear the health and economic effects of unplanned pregnancy.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing medically-accurate, evidence based information on effective strategies to prevent STI infections and unplanned pregnancy.

- Students who identify as female are more likely to experience sexual or physical dating violence than their peers who identify as male. Some of this may be attributed to underreporting by males due to stigma.

- Students who identify as female are bullied on school property more often than students who identify as male.

- Young women ages 16-19 are at higher risk of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault than the general population.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by guiding the development of healthy self-identities, challenging harmful gender norms, and building the skills required for respectful, equitable relationships.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth from communities of color.

- Youth of color benefit from seeing themselves represented in sex education curriculum.

- Sex education programs that use a framing of diversity, equity, rights, and social justice , informed by an understanding of systemic racism and discrimination, have been found to increase positive attitudes around reproductive rights in all students.

- There is a critical need for sex education programs that reflect youth’s cultural values and community .

- Comprehensive sex education can address these needs by developing curriculum that is inclusive of diverse communities, relationships, and cultures, so that youth see themselves represented in their education.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in STI and HIV infection.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in unplanned pregnancy and births among adolescents.

- Nearly half of youth who are Black ages 13-21 report having been pressured into sexual activity .

- Adolescent experience with dating violence is most prevalent among youth who are American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial.

- Adolescents who are Latinx are more likely than their peers who are non-Latinx to report physical dating violence .

- Youth who are Black and Latinx and who experience bullying are more likely to suffer negative impacts on academic performance than their white peers.

- Students who are Asian American and Pacific Islander report bullying and harassment due to race, ethnicity, and language.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by guiding the development of healthy self-identities, challenging harmful stereotypes, and building the skills required for respectful, equitable relationships.

- Young people of color—specifically those from Black , Asian-American , and Latinx communities– are often hyper-sexualized in popular media, leading to societal perceptions that youth are “older” or more sexually experienced than their white peers.

- Young men of color—specifically those from Black and Latinx communities—are often portrayed as aggressive or criminal in popular media, leading to societal perceptions that youth are dangerous or more sexually aggressive or experienced than white peers.

- These media portrayals can lead to disparities in public perceptions of youth behavior , which can impact school discipline, lost mentorship and leadership opportunities, less access to educational opportunities afforded to white peers, and greater involvement in the juvenile justice system.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by including positive representations of diverse youth in curriculum, challenging harmful stereotypes, and building the skills required for respectful relationships.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth with disabilities or special health care needs.

- Youth with disabilities need inclusive, developmentally-appropriate, representative sex education to support their health, identity, and development .

- Youth with special health care needs often initiate romantic relationships and sexual behavior during adolescence, similar to their peers.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs benefit from seeing themselves represented in sex education to access the information and skills to build healthy identities and relationships.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses this need by including positive representation of youth with disabilities and special health care needs in curriculum and providing developmentally-appropriate sex education to all youth.

- When youth with disabilities and special health care needs do not get access to the comprehensive sex education that they need, they are at increased risk of sexual abuse or being viewed as a sexual offender.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs are more likely than peers without disabilities to report coercive sex, exploitation, and sexual abuse.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs report more sexualized behavior and victimization online than their peers without disabilities.

- Youth with disabilities are at greater risk of bullying and have fewer friend relationships than their peers.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing education on healthy relationships, consent, communication, and bodily autonomy.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- Most sex education curriculum is not inclusive or representative of LGBTQ2S+ identities and experiences.

- Because school-based sex education often does not meet their needs, youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are more likely to seek sexual health information online , and thus are more likely to come across misinformation.

- The majority of parents support discussion of sexual orientation in sex education classes.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by including positive representation of LGBTQ2S+ individuals, romantic relationships, and families.

- Sex education curriculum that overlooks or stigmatizes youth who are LGBTQ2S+ contributes to hostile school environments and harms the healthy sexual and mental development .

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ face high levels of discrimination at school and are more likely to miss school because of bullying or victimization .

- Ongoing experiences with stigma, exclusion, and harassment negatively impact the mental health of youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- Comprehensive sex education provides inclusive curriculum and has been shown to improve understanding of gender diversity, lower rates of homophobia, and reduce homophobic bullying in schools.

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are more likely than their heterosexual peers to report not learning about HIV/STIs in school .

- Lack of education on STI prevention leaves LGBTQ2S+ youth without the information they need to make informed decisions, leading to discrepancies in condom use between LGBTQ2S+ and heterosexual youth.

- Some LGBTQ2S+ populations carry a disproportionate burden of HIV and other STIs: these disparities begin in adolescence , when youth who are LGBTQ2S+ do not receive sex education that is relevant to them.

- Comprehensive sex education provides the knowledge and skills needed to make safe decisions about sexual behavior , including condom use and other forms of STI and HIV prevention.

- Youth who are LBGTQ2S+ or are questioning their sexual identity report higher rates of dating violence than their heterosexual peers.

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ or are questioning their sexual identity face higher prevalence of bullying than their heterosexual peers.

- Comprehensive sex education teaches youth healthy relationship and communication skills and is associated with decreases in dating violence and increases in bystander interventions .

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth who are in foster care.

- More than 70% of children in foster care have a documented history of child abuse and or neglect.

- More than 80% of children in foster care have been exposed to significant levels of violence, including domestic violence.

- Youth in foster care are racially diverse, with 23% of youth identifying as Black and 21% of identifying as Latinx, who will have similar experiences as those highlighted in earlier sections of this report.

- Removal is emotionally traumatizing for almost all children. Lack of consistent/stable placement with a responsive, nurturing caregiver can result in poor emotional regulation, impulsivity, and attachment problems.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing evidence-based, culturally appropriate information on healthy relationships, consent, communication, and bodily autonomy.

Sex education is often the first experience that youth have with understanding and discussing their gender and sexual health.

Youth deserve to a strong foundation of developmentally appropriate information about gender and sexuality, and how these things relate to their bodies, community, culture, society, mental health, and relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners.

Decades of data have demonstrated that comprehensive sex education programs are effective in reducing risk of STIs and unplanned pregnancy. These benefits are critical to public health. However, comprehensive sex education goes even further, by instilling youth with a broad range of knowledge and skills that are proven to support social-emotional learning, positive communication skills, and development of healthy relationships.

Last Updated

American Academy of Pediatrics

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

School Based Sex Education and HIV Prevention in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, International Health Department, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

Affiliation Medical University of South Carolina, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Charleston, South Carolina, United States of America

- Virginia A. Fonner,

- Kevin S. Armstrong,

- Caitlin E. Kennedy,

- Kevin R. O'Reilly,

- Michael D. Sweat

- Published: March 4, 2014

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692

- Reader Comments

School-based sex education is a cornerstone of HIV prevention for adolescents who continue to bear a disproportionally high HIV burden globally. We systematically reviewed and meta-analyzed the existing evidence for school-based sex education interventions in low- and middle-income countries to determine the efficacy of these interventions in changing HIV-related knowledge and risk behaviors.

We searched five electronic databases, PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and Sociological Abstracts, for eligible articles. We also conducted hand-searching of key journals and secondary reference searching of included articles to identify potential studies. Intervention effects were synthesized through random effects meta-analysis for five outcomes: HIV knowledge, self-efficacy, sexual debut, condom use, and number of sexual partners.

Of 6191 unique citations initially identified, 64 studies in 63 articles were included in the review. Nine interventions either focused exclusively on abstinence (abstinence-only) or emphasized abstinence (abstinence-plus), whereas the remaining 55 interventions provided comprehensive sex education. Thirty-three studies were able to be meta-analyzed across five HIV-related outcomes. Results from meta-analysis demonstrate that school-based sex education is an effective strategy for reducing HIV-related risk. Students who received school-based sex education interventions had significantly greater HIV knowledge (Hedges g = 0.63, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.49–0.78, p<0.001), self-efficacy related to refusing sex or condom use (Hedges g = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.14–0.36, p<0.001), condom use (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.18–1.52, p<0.001), fewer sexual partners (OR = 0.75, 95% CI:0.67–0.84, p<0.001) and less initiation of first sex during follow-up (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.54–0.83, p<0.001).

Conclusions

The paucity of abstinence-only or abstinence-plus interventions identified during the review made comparisons between the predominant comprehensive and less common abstinence-focused programs difficult. Comprehensive school-based sex education interventions adapted from effective programs and those involving a range of school-based and community-based components had the largest impact on changing HIV-related behaviors.

Citation: Fonner VA, Armstrong KS, Kennedy CE, O'Reilly KR, Sweat MD (2014) School Based Sex Education and HIV Prevention in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 9(3): e89692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692

Editor: Sten H. Vermund, Vanderbilt University, United States of America

Received: May 20, 2013; Accepted: January 27, 2014; Published: March 4, 2014

Copyright: © 2014 Fonner et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This research was supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health, Grants R01 MH090173 and RC1 MH088950. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Worldwide, young people aged 15–24 accounted for almost half of all new HIV infections among individuals aged 15 and older in 2010 [1] . School-based sex education is an intervention that has been promoted to increase HIV-related knowledge and shape safer sexual behaviors to help prevent new infections among this vulnerable group. As sexual debut is common in adolescence, so are the associated risks of engaging in transactional sex, having multiple concurrent partnerships, and experiencing sexual violence and coercion, all of which increase HIV-related risk [2] . School-based interventions are logistically well-suited to educate youth about sexual activity given their ability to reach large numbers of young people in an environment already equipped to facilitate educational lessons and group learning [3] .

Contentious debates have raged in the past decade regarding whether abstinence-only or comprehensive sexual education interventions are effective and appropriate. Abstinence-only interventions promote delaying sex until marriage with little to no information provided about contraceptives or condom use, whereas comprehensive sexual education provides information on abstinence as well as information on how to engage in safer sex and prevent pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In the 1990s various groups in the United States invested in abstinence-only education, and with the creation of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2004, money was earmarked for “ABC” programs (abstain, be faithful, use condoms), with a heavy emphasis on the “A” component, to be implemented in low- and middle-income countries most impacted by HIV [4] . Critics of abstinence-only education claim that it violates human rights by withholding potentially life-saving information from people about other means to protect themselves from HIV, such as condom use [5] . Others argue that abstinence is only a viable option for those who are able to choose when, how, and with whom to have sex, which is not always the case for many young women [6] . Additionally, promoting abstinence until marriage excludes gay children and adolescents who have no option for marriage in most countries. As an alternative, comprehensive school-based sex education programs present participants with all prevention options, including condom use and partner reduction. Abstinence-plus interventions present prevention options as hierarchical with abstinence being presented as the only strategy that completely eliminates HIV/STI risk.

Previous research has been conducted on the effectiveness of youth-oriented HIV prevention and sex education interventions in school settings. A review of 35 school-based sex education programs by Kirby and Coyle [7] found that abstinence based programs had no significant effect on delaying sexual debut, while some comprehensive programs were effective in reducing certain sexual risk behaviors. Gallant and Maticka-Tyndale [3] reviewed 11 school-based HIV education programs in Africa and concluded that most studies had an effect on either increasing HIV-related knowledge or changing attitudes or behaviors relating to sexual risk. Paul-Ebhohimhen et al. [8] systematically reviewed 10 school-based sex education studies implemented in sub-Saharan Africa and noted that interventions were more likely to report changes in knowledge as opposed to changes in sexual behavior. Speizer et al. [9] reviewed 41 adolescent reproductive health interventions in developing countries, including 22 based in schools, and found that the majority of school-based interventions (17/21) demonstrated improved HIV-related knowledge. Chin et al. [10] conducted parallel systematic reviews and meta-analyses of comprehensive and abstinence-only educational interventions and found that comprehensive sex education programs significantly reduced HIV, STI, and unintended pregnancies, but results for the abstinence-only review were inconclusive.

However, few reviews have attempted to quantitatively synthesize the effects of school-based interventions on HIV-related risk behaviors across studies, and no review to date has attempted to compare the effectiveness of abstinence-only or abstinence plus interventions with comprehensive sex education in low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, the current review seeks to address this gap by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of school-based sex education interventions, including abstinence-only/abstinence-plus and comprehensive sex education programs, in changing HIV-related knowledge and risk behaviors in low- and middle-income countries. This review sought to answer the following research question: Does participating in school-based sex education vs. not participating in school-based sex education reduce HIV-related risk behaviors among youth in low- and middle-income countries?

This review is part of a large systematic review and meta-analysis project, called The Evidence Project, which is a joint collaboration between investigators at the Medical University of South Carolina and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The Evidence Project reviews the efficacy of behavioral HIV prevention interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Other reviews published with this project include topics such as voluntary counseling and testing [11] , [12] , provider-initiated testing and counseling [13] , condom social marketing [14] , behavioral interventions for people living with HIV [15] , peer education [16] , psychosocial support [17] , mass media [18] , and treatment as prevention [19] . This review used standardized data abstraction forms and procedures that have been employed in all reviews published as part of The Evidence Project, although no standalone protocol has been published specifically for this review. Additionally, we followed standard systematic review and meta-analysis procedures set forth in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20] .

Definition and Inclusion Criteria

School-based sex education was defined as programs designed to encourage sexual risk reduction strategies for HIV prevention delivered in school settings. This definition allowed for the inclusion of abstinence-only, abstinence-plus, and comprehensive sex education programs. Studies included in the review had to meet the following criteria: conducted in a low- or middle-income country as defined by the World Bank [21] ; published in a peer-reviewed journal from January 1, 1990 to June 16, 2010; presented results of pre-post or multi-arm experimental design and analysis of outcome(s) of interest; and involved an HIV prevention intervention administered in a school setting that encouraged one or more sexual risk reduction strategies, including abstinence, condom use, or partner reduction.

There were no restrictions on language; eligible non-English articles were translated by consultants fluent in English and the language in which the article was written. Participant age was also not restricted. Therefore, studies across a variety of educational settings, from primary schools through college and vocational schools, were included. Additionally, in order to include as many studies as possible, a wide range of study designs were eligible for inclusion: randomized controlled trials (both individual and cluster-randomized, i.e., school or classroom), non-randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohorts, time-series, before-after, case-control, cross-sectional, and serial cross-sectional studies.

Search strategy

Our search strategy involved three methods. First, five electronic databases, including PubMed, PsycInfo, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Sociological Abstracts, were searched using a combination of terms for sex education, schools/youth, and HIV or AIDS (full list available from the authors upon request). The search was limited to a date range of January 1, 1990 to June 16, 2010. We also searched the table of contents of AIDS , AIDS Care , AIDS and Behavior , and AIDS Education and Prevention for relevant citations. Finally, we searched the reference lists of all included studies for additional eligible studies. This process was iterative and continued until no additional studies were identified.

Trained research assistants conducted an initial screening of all citations and excluded studies clearly not relevant to school-based sex education. Two senior study staff members then independently screened all remaining citations and categorized studies as eligible for inclusion, not eligible for inclusion, or questionable. Discrepancies in categorization were resolved through consensus. Full article texts were obtained and discussed by senior researchers to ascertain eligibility if questionable. Articles were retained and included as background studies if they failed to meet the inclusion criteria but still contained information relevant to school-based sex education in low- and middle-income countries, including prior reviews, cost-effectiveness analyses, and qualitative studies.

Data Abstraction

The following data were abstracted from each eligible study using standardized forms: location, year(s) of study implementation, study setting, study population, sample size, study design, sampling frame and sampling methods, description of the intervention, composition of intervention and control groups (if applicable), length of follow-up, description of outcomes, effect sizes, confidence intervals, statistical tests employed, and study limitations. Two trained research assistants independently abstracted data from each study; any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Data were double entered into EpiData version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) and later exported to an SPSS database (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY).

We also evaluated the methodological rigor of studies to assess risk of bias based on the following criteria: whether the study 1) included a cohort of participants, 2) had a control and experimental/intervention group, 3) compared baseline demographic equivalence of control and intervention groups, 4) compared outcome measures between control and intervention groups at baseline (if applicable), 5) contained both pre- and post-intervention data, 6) randomly selected participants for assessment (i.e. sampling strategy), 7) randomly assigned participants to the intervention, and 8) maintained a follow-up rate of greater than 80%.

Selection of outcomes

Outcomes were chosen for meta-analysis based on relevance to HIV prevention and frequency in available studies. The five most commonly reported outcomes across studies were: HIV knowledge, condom use, self-efficacy related to HIV prevention (e.g., confidence in refusing sex or confidence in using condoms during sex), initiation of first sex, and number of sexual partners. All outcomes were based on self-report. Studies containing at least one of these outcomes were included in meta-analysis if they met the following criteria:

- Provided an estimate of effect size and its variance, or provided statistics needed to calculate an effect size and variance. If enough information was not provided to calculate an effect size, study authors were contacted for clarification or additional statistics. If study authors did not provide this information after one month, the study was removed from the analysis.

- Presented pre-post or multi-arm results comparing either participants who received the intervention to those who did not, or comparing outcomes before and after the intervention. If results of a repeated measures analysis were reported, authors needed to provide the correlation between pre-post measurements or provide enough information to calculate the correlation between measurements. If these statistics were not available, either in publication or after request, and the study was a controlled design, an effect size was generated using post-intervention statistics provided groups were similar at baseline with respect to the outcome of interest and other relevant covariates.

- Presented an outcome of interest that was measured in such a way as to be comparable to outcomes assessed by other studies. In other words, outcomes needed to be similar enough to synthesize across studies.

- Presented data based on an individual unit of analysis (studies presenting classroom- or school-level data only were excluded from meta-analysis).

Meta-analysis

Using standard meta-analytic methods [22] , we standardized effect sizes as either Hedges' g (for continuous outcomes) or odds ratios (for dichotomous outcomes). For several outcomes, including HIV knowledge, self-efficacy, and number of sexual partners, both continuous and dichotomous effect sizes were combined in meta-analysis. In these instances, Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) was used to either convert the standard mean difference into an odds ratio when transforming the effect size from continuous to dichotomous or vice versa using methods developed by Hasselblad and Hedges [23] . This transformation assumes that the outcome under study involves an underlying continuous trait with a logistic distribution [24] and that outcomes are measured in relatively similar terms, regardless of whether they are presented dichotomously or continuously. For example, several studies reported number of sexual partners as a dichotomous outcome, such as having two or more partners in the past 6 months, whereas others reported a mean number of partners. The same logic holds for outcomes such as knowledge, where some studies presented knowledge outcomes on a continuous scale whereas others created a cut-off for “high” and “low” knowledge scores and presented results as a proportion. Combining both dichotomous and continuous effect sizes allowed us to utilize all available data.

CMA V.2.2 was used for all analyses [25] . Random effects models were used as included studies contained considerable heterogeneity of effects, and the purpose of the analysis was to generate inferences beyond the set of included studies [26] .

When possible, data were analyzed in several ways per outcome. Stratifications by age, gender, instructor (e.g., teacher, peer, or health care professional), intervention type (abstinence vs. comprehensive sex education), and length of follow-up were made when three or more studies could be retained per category. Additionally, when possible, we investigated the role of certain characteristics of the data itself, including comparing differences between continuous and dichotomous effect sizes and whether the effect size was based on data collected pre-post intervention or post-only. Mixed effects meta-regression techniques were used to compare effect sizes across strata when possible. The I 2 statistic and its confidence interval were calculated for each meta-analysis to describe inconsistencies in effect sizes across studies [24] , [27] . When possible adjusted effect sizes were used in the pooled analyses; however, outcomes were most frequently reported in unadjusted terms, thus the analyses contain both adjusted and unadjusted effect sizes. Potential bias across studies, such as publication bias and selective reporting, was assessed for the HIV-related knowledge outcome by constructing a funnel plot. Funnel plots were not constructed for the remaining meta-analyses because there were too few studies to interpret the dispersion of effect sizes across the range of standard errors.

Description of studies

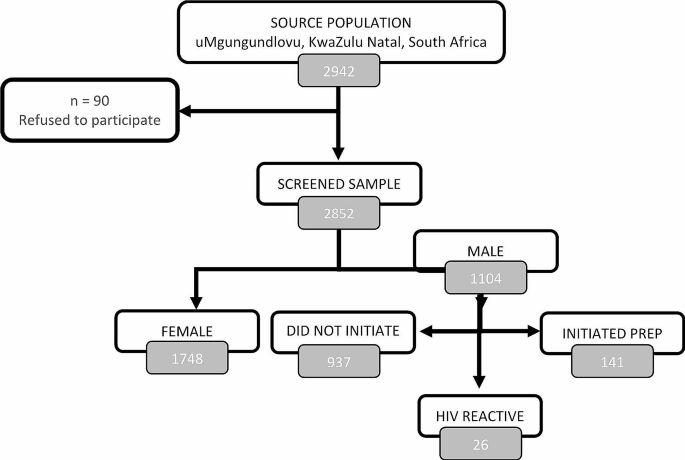

Of 6191 studies initially identified, 64 studies in 63 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review ( Figure 1 ). In five cases, more than one article presented data from the same study [28] – [39] . If articles from the same study presented different outcomes or follow-up times, both articles were retained and included in the review as one study [30] , [31] , [37] , [38] . If both articles presented similar data, such as by providing an update with longer follow-up, the most recent article or the article with the largest sample size was chosen for inclusion [28] , [33] , [36] , [39] .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692.g001

Table 1 provides descriptions of included studies. The majority of studies took place in sub-Saharan Africa (n = 29, 45.3%). Studies also took place in East Asia/Pacific (n = 15, 23.4%), Europe/Central Asia (n = 2, 3.1%), Latin American/Caribbean (n = 16, 25.0%), and South Asia (n = 4, 6.3%). The most commonly used study design was a group randomized trial (n = 21), with schools or classrooms as the unit of randomization. Other study designs included individual randomized controlled trials (n = 4), before-after studies (n = 14), non-randomized individual trials (n = 2), non-randomized group trials (n = 12), serial cross-sectional studies (n = 4), cross-sectional studies (n = 5), and two studies utilized a study design classified as “other” which involved a hybrid of eligible study designs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692.t001

Table 2 presents the methodological rigor assessment for included studies. Regarding methodological rigor, forty-seven studies used a control group, but only 18 studies reported whether intervention and control groups were equivalent on socio-economic variables at baseline, and only 14 reported whether intervention and control groups were equivalent on outcome measures at baseline.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089692.t002

Most studies included both male and female participants; three studies evaluated school based sex education for girls only [40] , [42] . Most studies (n = 56) took place among primary or secondary school students, five studies were implemented among university students [43] – [47] , two involved secondary and university students [36] , [48] , one study involved student nurses [49] , and another involved teacher trainees [50] . Ages of study participants ranged from 9, for an intervention among 4 th graders in Mexico [51] , to 38, for an intervention among university students in Malaysia [44] . Of the 27 studies reporting a mean age of study participants, the average age was 16.5 (SD = 2.7). Many studies included study populations with a wide range of ages. The age range in six studies spanned 10 years or more [52] – [55] . Generally, in studies measuring sexual risk behaviors, only a small portion of students in the study population were sexually active, thus substantially reducing the sample size for these outcomes.

Content of interventions.

Nine studies either taught abstinence-only or emphasized abstinence or delay of sexual debut over other risk reduction strategies among in-school youth [29] , [33] , [40] , [41] , [55] – [60] . The remaining studies provided comprehensive sex education.

Many studies reported using a variety of instructional formats to convey information and generate discussion. For example, 35 studies used lectures, 34 employed interactive discussions, 30 incorporated role-plays, and 21 utilized skill-based sessions, such as learning the steps involved in correct condom use. Use of media such as videos and audio tapes was also common. Two studies relied on drama, including creating plays and skits, for the bulk of the intervention [61] , [62] and one study used a comic book to impart information [63] . Two studies were internet-based [36] , [64] and involved students completing online modules during school hours at their own pace. Thirty three interventions reported basing their intervention on theory. Theories commonly referenced were Social Cognitive Theory, Health Belief Model, and Theory of Reasoned Action.