Study Population

- Reference work entry

- pp 6412–6414

- Cite this reference work entry

3446 Accesses

1 Citations

Study population is a subset of the target population from which the sample is actually selected. It is broader than the concept sample frame . It may be appropriate to say that sample frame is an operationalized form of study population. For example, suppose that a study is going to conduct a survey of high school students on their social well-being . High school students all over the world might be considered as the target population. Because of practicalities, researchers decide to only recruit high school students studying in China who are the study population in this example. Suppose there is a list of high school students of China, this list is used as the sample frame .

Description

Study population is the operational definition of target population (Henry, 1990 ; Bickman & Rog, 1998 ). Researchers are seldom in a position to study the entire target population, which is not always readily accessible. Instead, only part of it—respondents who are both eligible for the study...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Babbie, E. R. (2010). The practice of social research . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Bickman, L., & Rog, D. J. (1998). Handbook of applied social research methods . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Friedman, L. M., Furberg, C. D., & DeMets, D. L. (2010). Fundamentals of clinical trials . New York: Springer.

Gerrish, K., & Lacey, A. (2010). The research process in nursing . West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Henry, G. T. (1990). Practical sampling . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners . London: Sage Publications Limited.

Riegelman, R. K. (2005). Studying a study and testing a test: How to read the medical evidence . Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sociology Department, National University of Singapore, 11 Arts Link, 117570, Singapore, Singapore

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shu Hu .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC, Canada

Alex C. Michalos

(residence), Brandon, MB, Canada

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Hu, S. (2014). Study Population. In: Michalos, A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2893

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2893

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-007-0752-8

Online ISBN : 978-94-007-0753-5

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Unraveling Research Population and Sample: Understanding their role in statistical inference

Research population and sample serve as the cornerstones of any scientific inquiry. They hold the power to unlock the mysteries hidden within data. Understanding the dynamics between the research population and sample is crucial for researchers. It ensures the validity, reliability, and generalizability of their findings. In this article, we uncover the profound role of the research population and sample, unveiling their differences and importance that reshapes our understanding of complex phenomena. Ultimately, this empowers researchers to make informed conclusions and drive meaningful advancements in our respective fields.

Table of Contents

What Is Population?

The research population, also known as the target population, refers to the entire group or set of individuals, objects, or events that possess specific characteristics and are of interest to the researcher. It represents the larger population from which a sample is drawn. The research population is defined based on the research objectives and the specific parameters or attributes under investigation. For example, in a study on the effects of a new drug, the research population would encompass all individuals who could potentially benefit from or be affected by the medication.

When Is Data Collection From a Population Preferred?

In certain scenarios where a comprehensive understanding of the entire group is required, it becomes necessary to collect data from a population. Here are a few situations when one prefers to collect data from a population:

1. Small or Accessible Population

When the research population is small or easily accessible, it may be feasible to collect data from the entire population. This is often the case in studies conducted within specific organizations, small communities, or well-defined groups where the population size is manageable.

2. Census or Complete Enumeration

In some cases, such as government surveys or official statistics, a census or complete enumeration of the population is necessary. This approach aims to gather data from every individual or entity within the population. This is typically done to ensure accurate representation and eliminate sampling errors.

3. Unique or Critical Characteristics

If the research focuses on a specific characteristic or trait that is rare and critical to the study, collecting data from the entire population may be necessary. This could be the case in studies related to rare diseases, endangered species, or specific genetic markers.

4. Legal or Regulatory Requirements

Certain legal or regulatory frameworks may require data collection from the entire population. For instance, government agencies might need comprehensive data on income levels, demographic characteristics, or healthcare utilization for policy-making or resource allocation purposes.

5. Precision or Accuracy Requirements

In situations where a high level of precision or accuracy is necessary, researchers may opt for population-level data collection. By doing so, they mitigate the potential for sampling error and obtain more reliable estimates of population parameters.

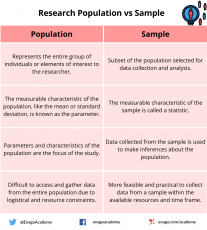

What Is a Sample?

A sample is a subset of the research population that is carefully selected to represent its characteristics. Researchers study this smaller, manageable group to draw inferences that they can generalize to the larger population. The selection of the sample must be conducted in a manner that ensures it accurately reflects the diversity and pertinent attributes of the research population. By studying a sample, researchers can gather data more efficiently and cost-effectively compared to studying the entire population. The findings from the sample are then extrapolated to make conclusions about the larger research population.

What Is Sampling and Why Is It Important?

Sampling refers to the process of selecting a sample from a larger group or population of interest in order to gather data and make inferences. The goal of sampling is to obtain a sample that is representative of the population, meaning that the sample accurately reflects the key attributes, variations, and proportions present in the population. By studying the sample, researchers can draw conclusions or make predictions about the larger population with a certain level of confidence.

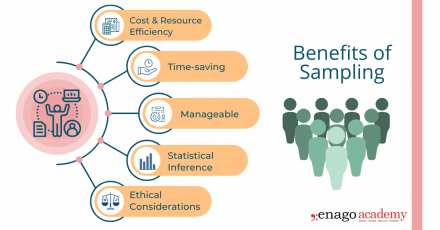

Collecting data from a sample, rather than the entire population, offers several advantages and is often necessary due to practical constraints. Here are some reasons to collect data from a sample:

1. Cost and Resource Efficiency

Collecting data from an entire population can be expensive and time-consuming. Sampling allows researchers to gather information from a smaller subset of the population, reducing costs and resource requirements. It is often more practical and feasible to collect data from a sample, especially when the population size is large or geographically dispersed.

2. Time Constraints

Conducting research with a sample allows for quicker data collection and analysis compared to studying the entire population. It saves time by focusing efforts on a smaller group, enabling researchers to obtain results more efficiently. This is particularly beneficial in time-sensitive research projects or situations that necessitate prompt decision-making.

3. Manageable Data Collection

Working with a sample makes data collection more manageable . Researchers can concentrate their efforts on a smaller group, allowing for more detailed and thorough data collection methods. Furthermore, it is more convenient and reliable to store and conduct statistical analyses on smaller datasets. This also facilitates in-depth insights and a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

4. Statistical Inference

Collecting data from a well-selected and representative sample enables valid statistical inference. By using appropriate statistical techniques, researchers can generalize the findings from the sample to the larger population. This allows for meaningful inferences, predictions, and estimation of population parameters, thus providing insights beyond the specific individuals or elements in the sample.

5. Ethical Considerations

In certain cases, collecting data from an entire population may pose ethical challenges, such as invasion of privacy or burdening participants. Sampling helps protect the privacy and well-being of individuals by reducing the burden of data collection. It allows researchers to obtain valuable information while ensuring ethical standards are maintained .

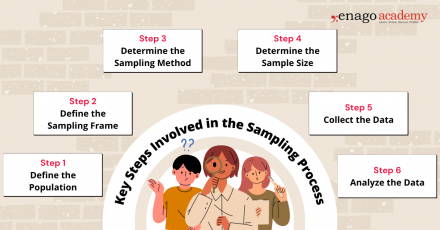

Key Steps Involved in the Sampling Process

Sampling is a valuable tool in research; however, it is important to carefully consider the sampling method, sample size, and potential biases to ensure that the findings accurately represent the larger population and are valid for making conclusions and generalizations. While the specific steps may vary depending on the research context, here is a general outline of the sampling process:

1. Define the Population

Clearly define the target population for your research study. The population should encompass the group of individuals, elements, or units that you want to draw conclusions about.

2. Define the Sampling Frame

Create a sampling frame, which is a list or representation of the individuals or elements in the target population. The sampling frame should be comprehensive and accurately reflect the population you want to study.

3. Determine the Sampling Method

Select an appropriate sampling method based on your research objectives, available resources, and the characteristics of the population. You can perform sampling by either utilizing probability-based or non-probability-based techniques. Common sampling methods include random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, and convenience sampling.

4. Determine Sample Size

Determine the desired sample size based on statistical considerations, such as the level of precision required, desired confidence level, and expected variability within the population. Larger sample sizes generally reduce sampling error but may be constrained by practical limitations.

5. Collect Data

Once the sample is selected using the appropriate technique, collect the necessary data according to the research design and data collection methods . Ensure that you use standardized and consistent data collection process that is also appropriate for your research objectives.

6. Analyze the Data

Perform the necessary statistical analyses on the collected data to derive meaningful insights. Use appropriate statistical techniques to make inferences, estimate population parameters, test hypotheses, or identify patterns and relationships within the data.

Population vs Sample — Differences and examples

While the population provides a comprehensive overview of the entire group under study, the sample, on the other hand, allows researchers to draw inferences and make generalizations about the population. Researchers should employ careful sampling techniques to ensure that the sample is representative and accurately reflects the characteristics and variability of the population.

Research Study: Investigating the prevalence of stress among high school students in a specific city and its impact on academic performance.

Population: All high school students in a particular city

Sampling Frame: The sampling frame would involve obtaining a comprehensive list of all high schools in the specific city. A random selection of schools would be made from this list to ensure representation from different areas and demographics of the city.

Sample: Randomly selected 500 high school students from different schools in the city

The sample represents a subset of the entire population of high school students in the city.

Research Study: Assessing the effectiveness of a new medication in managing symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with the specific medical condition.

Population: Patients diagnosed with a specific medical condition

Sampling Frame: The sampling frame for this study would involve accessing medical records or databases that include information on patients diagnosed with the specific medical condition. Researchers would select a convenient sample of patients who meet the inclusion criteria from the sampling frame.

Sample: Convenient sample of 100 patients from a local clinic who meet the inclusion criteria for the study

The sample consists of patients from the larger population of individuals diagnosed with the medical condition.

Research Study: Investigating community perceptions of safety and satisfaction with local amenities in the neighborhood.

Population: Residents of a specific neighborhood

Sampling Frame: The sampling frame for this study would involve obtaining a list of residential addresses within the specific neighborhood. Various sources such as census data, voter registration records, or community databases offer the means to obtain this information. From the sampling frame, researchers would randomly select a cluster sample of households to ensure representation from different areas within the neighborhood.

Sample: Cluster sample of 50 households randomly selected from different blocks within the neighborhood

The sample represents a subset of the entire population of residents living in the neighborhood.

To summarize, sampling allows for cost-effective data collection, easier statistical analysis, and increased practicality compared to studying the entire population. However, despite these advantages, sampling is subject to various challenges. These challenges include sampling bias, non-response bias, and the potential for sampling errors.

To minimize bias and enhance the validity of research findings , researchers should employ appropriate sampling techniques, clearly define the population, establish a comprehensive sampling frame, and monitor the sampling process for potential biases. Validating findings by comparing them to known population characteristics can also help evaluate the generalizability of the results. Properly understanding and implementing sampling techniques ensure that research findings are accurate, reliable, and representative of the larger population. By carefully considering the choice of population and sample, researchers can draw meaningful conclusions and, consequently, make valuable contributions to their respective fields of study.

Now, it’s your turn! Take a moment to think about a research question that interests you. Consider the population that would be relevant to your inquiry. Who would you include in your sample? How would you go about selecting them? Reflecting on these aspects will help you appreciate the intricacies involved in designing a research study. Let us know about it in the comment section below or reach out to us using #AskEnago and tag @EnagoAcademy on Twitter , Facebook , and Quora .

Thank you very much, this is helpful

Very impressive and helpful and also easy to understand….. Thanks to the Author and Publisher….

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Trending Now

- Understanding Ethics

Understanding the Impact of Retractions on Research Integrity – A global study

As we reach the midway point of 2024, ‘Research Integrity’ remains one of the hot…

- Diversity and Inclusion

The Silent Struggle: Confronting gender bias in science funding

In the 1990s, Dr. Katalin Kariko’s pioneering mRNA research seemed destined for obscurity, doomed by…

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Addressing Barriers in Academia: Navigating unconscious biases in the Ph.D. journey

In the journey of academia, a Ph.D. marks a transitional phase, like that of a…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Introduction to Population Demographics

A population is defined as a group of individuals of the same species living and interbreeding within a given area. Members of a population often rely on the same resources, are subject to similar environmental constraints, and depend on the availability of other members to persist over time. Scientists study a population by examining how individuals in that population interact with each other and how the population as a whole interacts with its environment. As a tool for objectively studying populations, population ecologists rely on a series of statistical measures, known as demographic parameters , to describe that population (Lebreton et al . 1992). The field of science interested in collecting and analyzing these numbers is termed population demographics, also known as demography.

Broadly defined, demography is the study of the characteristics of populations. It provides a mathematical description of how those characteristics change over time. Demographics can include any statistical factors that influence population growth or decline, but several parameters are particularly important: population size, density, age structure, fecundity (birth rates), mortality (death rates), and sex ratio (Dodge 2006). We introduce each of these in turn.

Population Size

Populations display distinctive behaviors based on their size. Small populations face a greater risk of extinction (Caughley 1994). Individuals in these populations can have a hard time finding quality mates so, fewer individuals mate and those that do risk inbreeding (Hamilton 1967). Additionally, individuals in small population are more susceptible to random deaths. Events like fire, floods, and disease have a greater chance of killing all individuals in the population.

Large populations experience their own problems. As they approach the maximum sustainable population size, known as carrying capacity, large populations show characteristic behavior. Populations nearing their carrying capacity experience greater competition for resources, shifts in predator-prey relationships , and lowered fecundity. If the population grows too large, it may begin to exceed the carrying capacity of the environment and degrade available habitat (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Swarms of locusts exceed carrying capacity with huge population sizes. These short-lived spikes in population size produce swarms capable of destroying farms as they move across the agricultural landscapes, eating everything in their path. Photo courtesy of Compton Tucker/NASA GSFC.

Population Density

A more complete description of a population's size includes the population density — the size of a population in relation to the amount of space that it occupies. Density is usually expressed as the number of individuals per unit area or volume (Lebreton et al . 1992). For example: the number of crows per square kilometer or the number of plankton per liter (Andren 1992, Sterner 1986). Like all population properties, density is a dynamic characteristic that changes over time as individuals are added to or removed from the population. Closely related species of Gannet birds will maintain very different densities (Figure 2 ). Birth and immigration — the influx of new individuals from other areas — can increase a population's density, while death and emigration — the movement of individuals out of a population to other areas — can decrease its density (Lebreton et al . 1992).

Figure 2: Gannets can persist at very high densities. They have developed exaggerated territorial behavior as an adaptation to sustain these densely packed colonies. Photo courtesy of Follash via Wikimedia Commons.

Similar to population size, population density displays distinctive characteristics at both high and low values. Density-dependent factors , including competition, predation , migration and disease, intensify within populations as density increases. In contrast, density-independent factors , such as weather, fire regimes, and flooding, impact populations regardless of their specific densities (Lebreton et al . 1992).

Age Structure

Age structure can be represented graphically with a population pyramid (Figure 3). Although a population's age structure is not always pyramidal in shape, most populations have younger cohorts that are larger than older cohorts. For example, Sherman and Morton's studies of the Tioga Pass Belding's ground squirrels revealed birth cohorts larger than 300 individuals and less than 10 individuals in cohorts over the age of six (Sherman & Morton 1984).

While maximum fecundity is a constant for populations, realized fecundity varies over time based on the size, density, and age structure of the population. External conditions, such as food and habitat availability, can also influence fecundity. Density-dependent regulation provides a negative feedback if the population grows too large, by reducing birth rates and halting population growth through a host of mechanisms (Lebreton et al . 1992). In white-footed mice, for example, populations regulate their reproductive rate via a stress hormone . As population densities increase, so do aggressive interactions between individuals (even when food and shelter are unlimited). High population densities lead to frequent aggressive encounters, triggering a stress syndrome in which hormonal changes delay sexual maturation , cause reproductive organs to shrink, and depress the immune system (Krohne 1984).

To visualize mortality and fecundity within a population, ecologists create life tables to display age-specific statistical summaries of a population's survival patterns. First developed by Roman actuaries, life tables were used to estimate how long individuals of a particular age category were expected to live in order to value life insurance products (Trenerry 1926). Raymond Pearl (1928) first introduced the life table to biology when he applied it to laboratory studies of the fruit fly, Drosophila . Life tables are particularly useful for species with discrete developmental stages and mortality rates that vary widely from one stage to the next (Figure 5).

Nezara viridula ) assumes different body forms through metamorphosis between different discrete life stages." /> Figure 5: The Green Stink Bug ( Nezara viridula ) assumes different body forms through metamorphosis between different discrete life stages. Photo courtesy of Jovo26 via Wikimedia Commons

Interestingly, sex ratio is not always random but can be manipulated at birth by environmental or physiological mechanisms. All crocodiles and many reptiles utilize a strategy called environmental sex determination, wherein incubation temperature determines the sex of each individual (Delmas et al . 2008). For example, low temperatures will produce males and high temperatures will produce females. In times of limited resources or high population densities, females can manipulate the sex ratios of their clutch by spending more or less time incubating their eggs (Girondot et al . 2004).

age-specific : The age of the individual is important for statistical purposes.

clutch size : The number of offspring one female produces in one reproductive cycle.

cohort : Group of all individuals sharing a statistical factor (such as age or developmental stage)

density-dependent factors : Depending on the local density of the population

density-independent factors : Not linked to the local density of the population

discrete developmental stages : Non-overlapping and structurally distinct growth stages. E.g. tadpoles are one discrete developmental stage and adult frogs are another.

ecosystem : A natural system including the interaction of all living and non-living elements.

extinction : No longer existing.

extrapolating : Estimating an unknown value by assuming that a known value can translate (without distortion) to the scale of the unknown value.

growth rate : The rate of change of population size over time.

inbreeding : Breeding of closely related individuals, often with negative genetic consequences.

incubated : Provided with a heat source during embryonic development.

life tables : Specific format of statistical summary of demographic parameters.

migration : Populations moving from one geographic location to another.

objectively : To study without bias and by measurable and repeatable metrics.

offspring : The individual produced from the reproduction of its parents.

parameter : A value in an equation that does not vary. These values can change between different equations of similar form.

predator-prey relationships : How populations of predators are interacting with populations of prey.

predation : The act of killing another living organism for food.

physiological : The parts and functions of living organisms.

reproductive organs : Specialized collection of cells used to exchange gametes between sexually reproducing organisms.

rates : A mathematical term for the number of things or events happening in a given amount of time.

rearing : To invest energy in the growth and development of offspring after they are born.

subjectively designated geographic range : A parcel of land, the size of which is chosen without using standardized criteria. Picked at the discretion of the researcher.

sustainable : System able to be maintained itself indefinitely without supplement.

sexual maturation : An individual reaching a stage of development where it is able to sexually reproduce.

stress hormone : Chemical compounds synthesized in the body to chemically communicate a stress reaction to various systems within that organism.

statistic : A number acting as a description for more numbers.

References and Recommended Reading

Andren, H. Corvid density and nest predation in relation to forest fragmentation: A landscape perspective. Ecology 73, 794-804 (1992).

Bull, J. Evolution of environmental sex determination from genotypic sex determination. Heredity 47, 173-184 (1981).

Caughley, G. Directions in conservation biology. Journal of Animal Ecology 63, 215-244 (1994).

Delmas, V., Pieau, C. & Girondot, M. A mechanistic model of temperature-dependent sex determination in a chelonian, the European pond turtle. Functional Ecology 22, 84-93 (2008).

Dodge, Y. The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Benrey, B & Denno, R. F. The slow-growth-high-mortality hypothesis: A test using the cabbage butterfly. Ecology 78, 987-999 (1997).

Girondot, M. et al . "Implications of temperature-dependent sex determination for population dynamics," Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Vertebrates , 148-155, eds. N. Valenzuela & V. Lance. Smithsonian Books, 2004.

Hamilton, W. D. Extraordinary sex ratios. Science 156, 477-488 (1967).

Harcombe, P. A. Tree life tables. BioScience 37, 557-568 (1987).

Hutchinson, G. E. Population studies: Animal ecology and demography. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 53, 193-213 (1991).

Jiguet, F. et al . Bird population trends are linearly affected by climate change along species thermal ranges. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277, 3601-3608 (2010).

Krohne, D. T., Dubbs, B. A. & Baccus, R. An analysis of dispersal in an unmanipulated population of Peromyscus leucopus. American Midland Naturalist 112, 146-156 (1984).

Lebreton, J-D. et al . Modeling survival and testing biological hypotheses using marked animals: A unified approach with case studies. Ecological Monographs 62, 67-118 (1992).

Martin, T. E. Avian life history evolution in relation to nest site, nest predation, and food. Ecological Monographs 65, 101-127 (1995).

Pearl, R. The Rate of Living, Being an Account of Some Experimental Studies on the Biology of Life Duration . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928.

Stearns, S. C. Life history tactics: A review of the ideas. The Quarterly Review of Biology 51, 3-47 (1976).

Sterner, R. Herbivores' direct and indirect effects on algal populations. Science 231, 605-607 (1986).

Trenerry, C. F. The Origin and Early History of Insurance, Including the Contract of Bottomry. London, UK: P. S. King & Son, 1926.

Flag Inappropriate

Email your Friend

- | Lead Editor:

Within this Subject (22)

- Basic (12)

- Intermediate (5)

- Advanced (5)

Other Topic Rooms

- Ecosystem Ecology

- Physiological Ecology

- Population Ecology

- Community Ecology

- Global and Regional Ecology

- Conservation and Restoration

- Animal Behavior

- Teach Ecology

- Earth's Climate: Past, Present, and Future

- Terrestrial Geosystems

- Marine Geosystems

- Scientific Underpinnings

- Paleontology and Primate Evolution

- Human Fossil Record

- The Living Primates

© 2014 Nature Education

- Press Room |

- Terms of Use |

- Privacy Notice |

Visual Browse

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

Research Population

All research questions address issues that are of great relevance to important groups of individuals known as a research population.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Non-Probability Sampling

- Convenience Sampling

- Random Sampling

- Stratified Sampling

- Systematic Sampling

Browse Full Outline

- 1 What is Sampling?

- 2.1 Sample Group

- 2.2 Research Population

- 2.3 Sample Size

- 2.4 Randomization

- 3.1 Statistical Sampling

- 3.2 Sampling Distribution

- 3.3.1 Random Sampling Error

- 4.1 Random Sampling

- 4.2 Stratified Sampling

- 4.3 Systematic Sampling

- 4.4 Cluster Sampling

- 4.5 Disproportional Sampling

- 5.1 Convenience Sampling

- 5.2 Sequential Sampling

- 5.3 Quota Sampling

- 5.4 Judgmental Sampling

- 5.5 Snowball Sampling

A research population is generally a large collection of individuals or objects that is the main focus of a scientific query. It is for the benefit of the population that researches are done. However, due to the large sizes of populations, researchers often cannot test every individual in the population because it is too expensive and time-consuming. This is the reason why researchers rely on sampling techniques .

A research population is also known as a well-defined collection of individuals or objects known to have similar characteristics. All individuals or objects within a certain population usually have a common, binding characteristic or trait.

Usually, the description of the population and the common binding characteristic of its members are the same. "Government officials" is a well-defined group of individuals which can be considered as a population and all the members of this population are indeed officials of the government.

Relationship of Sample and Population in Research

A sample is simply a subset of the population. The concept of sample arises from the inability of the researchers to test all the individuals in a given population. The sample must be representative of the population from which it was drawn and it must have good size to warrant statistical analysis.

The main function of the sample is to allow the researchers to conduct the study to individuals from the population so that the results of their study can be used to derive conclusions that will apply to the entire population. It is much like a give-and-take process. The population “gives” the sample, and then it “takes” conclusions from the results obtained from the sample.

Two Types of Population in Research

Target population.

Target population refers to the ENTIRE group of individuals or objects to which researchers are interested in generalizing the conclusions. The target population usually has varying characteristics and it is also known as the theoretical population.

Accessible Population

The accessible population is the population in research to which the researchers can apply their conclusions. This population is a subset of the target population and is also known as the study population. It is from the accessible population that researchers draw their samples.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Explorable.com (Nov 15, 2009). Research Population. Retrieved Sep 07, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/research-population

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Want to stay up to date? Follow us!

Save this course for later.

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim

- v.44(4); 2016 Aug

What is Scientific Research and How Can it be Done?

Scientific researches are studies that should be systematically planned before performing them. In this review, classification and description of scientific studies, planning stage randomisation and bias are explained.

Research conducted for the purpose of contributing towards science by the systematic collection, interpretation and evaluation of data and that, too, in a planned manner is called scientific research: a researcher is the one who conducts this research. The results obtained from a small group through scientific studies are socialised, and new information is revealed with respect to diagnosis, treatment and reliability of applications. The purpose of this review is to provide information about the definition, classification and methodology of scientific research.

Before beginning the scientific research, the researcher should determine the subject, do planning and specify the methodology. In the Declaration of Helsinki, it is stated that ‘the primary purpose of medical researches on volunteers is to understand the reasons, development and effects of diseases and develop protective, diagnostic and therapeutic interventions (method, operation and therapies). Even the best proven interventions should be evaluated continuously by investigations with regard to reliability, effectiveness, efficiency, accessibility and quality’ ( 1 ).

The questions, methods of response to questions and difficulties in scientific research may vary, but the design and structure are generally the same ( 2 ).

Classification of Scientific Research

Scientific research can be classified in several ways. Classification can be made according to the data collection techniques based on causality, relationship with time and the medium through which they are applied.

- Observational

- Experimental

- Descriptive

- Retrospective

- Prospective

- Cross-sectional

- Social descriptive research ( 3 )

Another method is to classify the research according to its descriptive or analytical features. This review is written according to this classification method.

I. Descriptive research

- Case series

- Surveillance studies

II. Analytical research

- Observational studies: cohort, case control and cross- sectional research

- Interventional research: quasi-experimental and clinical research

- Case Report: it is the most common type of descriptive study. It is the examination of a single case having a different quality in the society, e.g. conducting general anaesthesia in a pregnant patient with mucopolysaccharidosis.

- Case Series: it is the description of repetitive cases having common features. For instance; case series involving interscapular pain related to neuraxial labour analgesia. Interestingly, malignant hyperthermia cases are not accepted as case series since they are rarely seen during historical development.

- Surveillance Studies: these are the results obtained from the databases that follow and record a health problem for a certain time, e.g. the surveillance of cross-infections during anaesthesia in the intensive care unit.

Moreover, some studies may be experimental. After the researcher intervenes, the researcher waits for the result, observes and obtains data. Experimental studies are, more often, in the form of clinical trials or laboratory animal trials ( 2 ).

Analytical observational research can be classified as cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies.

Firstly, the participants are controlled with regard to the disease under investigation. Patients are excluded from the study. Healthy participants are evaluated with regard to the exposure to the effect. Then, the group (cohort) is followed-up for a sufficient period of time with respect to the occurrence of disease, and the progress of disease is studied. The risk of the healthy participants getting sick is considered an incident. In cohort studies, the risk of disease between the groups exposed and not exposed to the effect is calculated and rated. This rate is called relative risk. Relative risk indicates the strength of exposure to the effect on the disease.

Cohort research may be observational and experimental. The follow-up of patients prospectively is called a prospective cohort study . The results are obtained after the research starts. The researcher’s following-up of cohort subjects from a certain point towards the past is called a retrospective cohort study . Prospective cohort studies are more valuable than retrospective cohort studies: this is because in the former, the researcher observes and records the data. The researcher plans the study before the research and determines what data will be used. On the other hand, in retrospective studies, the research is made on recorded data: no new data can be added.

In fact, retrospective and prospective studies are not observational. They determine the relationship between the date on which the researcher has begun the study and the disease development period. The most critical disadvantage of this type of research is that if the follow-up period is long, participants may leave the study at their own behest or due to physical conditions. Cohort studies that begin after exposure and before disease development are called ambidirectional studies . Public healthcare studies generally fall within this group, e.g. lung cancer development in smokers.

- Case-Control Studies: these studies are retrospective cohort studies. They examine the cause and effect relationship from the effect to the cause. The detection or determination of data depends on the information recorded in the past. The researcher has no control over the data ( 2 ).

Cross-sectional studies are advantageous since they can be concluded relatively quickly. It may be difficult to obtain a reliable result from such studies for rare diseases ( 2 ).

Cross-sectional studies are characterised by timing. In such studies, the exposure and result are simultaneously evaluated. While cross-sectional studies are restrictedly used in studies involving anaesthesia (since the process of exposure is limited), they can be used in studies conducted in intensive care units.

- Quasi-Experimental Research: they are conducted in cases in which a quick result is requested and the participants or research areas cannot be randomised, e.g. giving hand-wash training and comparing the frequency of nosocomial infections before and after hand wash.

- Clinical Research: they are prospective studies carried out with a control group for the purpose of comparing the effect and value of an intervention in a clinical case. Clinical study and research have the same meaning. Drugs, invasive interventions, medical devices and operations, diets, physical therapy and diagnostic tools are relevant in this context ( 6 ).

Clinical studies are conducted by a responsible researcher, generally a physician. In the research team, there may be other healthcare staff besides physicians. Clinical studies may be financed by healthcare institutes, drug companies, academic medical centres, volunteer groups, physicians, healthcare service providers and other individuals. They may be conducted in several places including hospitals, universities, physicians’ offices and community clinics based on the researcher’s requirements. The participants are made aware of the duration of the study before their inclusion. Clinical studies should include the evaluation of recommendations (drug, device and surgical) for the treatment of a disease, syndrome or a comparison of one or more applications; finding different ways for recognition of a disease or case and prevention of their recurrence ( 7 ).

Clinical Research

In this review, clinical research is explained in more detail since it is the most valuable study in scientific research.

Clinical research starts with forming a hypothesis. A hypothesis can be defined as a claim put forward about the value of a population parameter based on sampling. There are two types of hypotheses in statistics.

- H 0 hypothesis is called a control or null hypothesis. It is the hypothesis put forward in research, which implies that there is no difference between the groups under consideration. If this hypothesis is rejected at the end of the study, it indicates that a difference exists between the two treatments under consideration.

- H 1 hypothesis is called an alternative hypothesis. It is hypothesised against a null hypothesis, which implies that a difference exists between the groups under consideration. For example, consider the following hypothesis: drug A has an analgesic effect. Control or null hypothesis (H 0 ): there is no difference between drug A and placebo with regard to the analgesic effect. The alternative hypothesis (H 1 ) is applicable if a difference exists between drug A and placebo with regard to the analgesic effect.

The planning phase comes after the determination of a hypothesis. A clinical research plan is called a protocol . In a protocol, the reasons for research, number and qualities of participants, tests to be applied, study duration and what information to be gathered from the participants should be found and conformity criteria should be developed.

The selection of participant groups to be included in the study is important. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study for the participants should be determined. Inclusion criteria should be defined in the form of demographic characteristics (age, gender, etc.) of the participant group and the exclusion criteria as the diseases that may influence the study, age ranges, cases involving pregnancy and lactation, continuously used drugs and participants’ cooperation.

The next stage is methodology. Methodology can be grouped under subheadings, namely, the calculation of number of subjects, blinding (masking), randomisation, selection of operation to be applied, use of placebo and criteria for stopping and changing the treatment.

I. Calculation of the Number of Subjects

The entire source from which the data are obtained is called a universe or population . A small group selected from a certain universe based on certain rules and which is accepted to highly represent the universe from which it is selected is called a sample and the characteristics of the population from which the data are collected are called variables. If data is collected from the entire population, such an instance is called a parameter . Conducting a study on the sample rather than the entire population is easier and less costly. Many factors influence the determination of the sample size. Firstly, the type of variable should be determined. Variables are classified as categorical (qualitative, non-numerical) or numerical (quantitative). Individuals in categorical variables are classified according to their characteristics. Categorical variables are indicated as nominal and ordinal (ordered). In nominal variables, the application of a category depends on the researcher’s preference. For instance, a female participant can be considered first and then the male participant, or vice versa. An ordinal (ordered) variable is ordered from small to large or vice versa (e.g. ordering obese patients based on their weights-from the lightest to the heaviest or vice versa). A categorical variable may have more than one characteristic: such variables are called binary or dichotomous (e.g. a participant may be both female and obese).

If the variable has numerical (quantitative) characteristics and these characteristics cannot be categorised, then it is called a numerical variable. Numerical variables are either discrete or continuous. For example, the number of operations with spinal anaesthesia represents a discrete variable. The haemoglobin value or height represents a continuous variable.

Statistical analyses that need to be employed depend on the type of variable. The determination of variables is necessary for selecting the statistical method as well as software in SPSS. While categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages, numerical variables are represented using measures such as mean and standard deviation. It may be necessary to use mean in categorising some cases such as the following: even though the variable is categorical (qualitative, non-numerical) when Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) is used (since a numerical value is obtained), it is classified as a numerical variable: such variables are averaged.

Clinical research is carried out on the sample and generalised to the population. Accordingly, the number of samples should be correctly determined. Different sample size formulas are used on the basis of the statistical method to be used. When the sample size increases, error probability decreases. The sample size is calculated based on the primary hypothesis. The determination of a sample size before beginning the research specifies the power of the study. Power analysis enables the acquisition of realistic results in the research, and it is used for comparing two or more clinical research methods.

Because of the difference in the formulas used in calculating power analysis and number of samples for clinical research, it facilitates the use of computer programs for making calculations.

It is necessary to know certain parameters in order to calculate the number of samples by power analysis.

- Type-I (α) and type-II (β) error levels

- Difference between groups (d-difference) and effect size (ES)

- Distribution ratio of groups

- Direction of research hypothesis (H1)

a. Type-I (α) and Type-II (β) Error (β) Levels

Two types of errors can be made while accepting or rejecting H 0 hypothesis in a hypothesis test. Type-I error (α) level is the probability of finding a difference at the end of the research when there is no difference between the two applications. In other words, it is the rejection of the hypothesis when H 0 is actually correct and it is known as α error or p value. For instance, when the size is determined, type-I error level is accepted as 0.05 or 0.01.

Another error that can be made during a hypothesis test is a type-II error. It is the acceptance of a wrongly hypothesised H 0 hypothesis. In fact, it is the probability of failing to find a difference when there is a difference between the two applications. The power of a test is the ability of that test to find a difference that actually exists. Therefore, it is related to the type-II error level.

Since the type-II error risk is expressed as β, the power of the test is defined as 1–β. When a type-II error is 0.20, the power of the test is 0.80. Type-I (α) and type-II (β) errors can be intentional. The reason to intentionally make such an error is the necessity to look at the events from the opposite perspective.

b. Difference between Groups and ES

ES is defined as the state in which statistical difference also has clinically significance: ES≥0.5 is desirable. The difference between groups is the absolute difference between the groups compared in clinical research.

c. Allocation Ratio of Groups

The allocation ratio of groups is effective in determining the number of samples. If the number of samples is desired to be determined at the lowest level, the rate should be kept as 1/1.

d. Direction of Hypothesis (H1)

The direction of hypothesis in clinical research may be one-sided or two-sided. While one-sided hypotheses hypothesis test differences in the direction of size, two-sided hypotheses hypothesis test differences without direction. The power of the test in two-sided hypotheses is lower than one-sided hypotheses.

After these four variables are determined, they are entered in the appropriate computer program and the number of samples is calculated. Statistical packaged software programs such as Statistica, NCSS and G-Power may be used for power analysis and calculating the number of samples. When the samples size is calculated, if there is a decrease in α, difference between groups, ES and number of samples, then the standard deviation increases and power decreases. The power in two-sided hypothesis is lower. It is ethically appropriate to consider the determination of sample size, particularly in animal experiments, at the beginning of the study. The phase of the study is also important in the determination of number of subjects to be included in drug studies. Usually, phase-I studies are used to determine the safety profile of a drug or product, and they are generally conducted on a few healthy volunteers. If no unacceptable toxicity is detected during phase-I studies, phase-II studies may be carried out. Phase-II studies are proof-of-concept studies conducted on a larger number (100–500) of volunteer patients. When the effectiveness of the drug or product is evident in phase-II studies, phase-III studies can be initiated. These are randomised, double-blinded, placebo or standard treatment-controlled studies. Volunteer patients are periodically followed-up with respect to the effectiveness and side effects of the drug. It can generally last 1–4 years and is valuable during licensing and releasing the drug to the general market. Then, phase-IV studies begin in which long-term safety is investigated (indication, dose, mode of application, safety, effectiveness, etc.) on thousands of volunteer patients.

II. Blinding (Masking) and Randomisation Methods

When the methodology of clinical research is prepared, precautions should be taken to prevent taking sides. For this reason, techniques such as randomisation and blinding (masking) are used. Comparative studies are the most ideal ones in clinical research.

Blinding Method

A case in which the treatments applied to participants of clinical research should be kept unknown is called the blinding method . If the participant does not know what it receives, it is called a single-blind study; if even the researcher does not know, it is called a double-blind study. When there is a probability of knowing which drug is given in the order of application, when uninformed staff administers the drug, it is called in-house blinding. In case the study drug is known in its pharmaceutical form, a double-dummy blinding test is conducted. Intravenous drug is given to one group and a placebo tablet is given to the comparison group; then, the placebo tablet is given to the group that received the intravenous drug and intravenous drug in addition to placebo tablet is given to the comparison group. In this manner, each group receives both the intravenous and tablet forms of the drug. In case a third party interested in the study is involved and it also does not know about the drug (along with the statistician), it is called third-party blinding.

Randomisation Method

The selection of patients for the study groups should be random. Randomisation methods are used for such selection, which prevent conscious or unconscious manipulations in the selection of patients ( 8 ).

No factor pertaining to the patient should provide preference of one treatment to the other during randomisation. This characteristic is the most important difference separating randomised clinical studies from prospective and synchronous studies with experimental groups. Randomisation strengthens the study design and enables the determination of reliable scientific knowledge ( 2 ).

The easiest method is simple randomisation, e.g. determination of the type of anaesthesia to be administered to a patient by tossing a coin. In this method, when the number of samples is kept high, a balanced distribution is created. When the number of samples is low, there will be an imbalance between the groups. In this case, stratification and blocking have to be added to randomisation. Stratification is the classification of patients one or more times according to prognostic features determined by the researcher and blocking is the selection of a certain number of patients for each stratification process. The number of stratification processes should be determined at the beginning of the study.

As the number of stratification processes increases, performing the study and balancing the groups become difficult. For this reason, stratification characteristics and limitations should be effectively determined at the beginning of the study. It is not mandatory for the stratifications to have equal intervals. Despite all the precautions, an imbalance might occur between the groups before beginning the research. In such circumstances, post-stratification or restandardisation may be conducted according to the prognostic factors.

The main characteristic of applying blinding (masking) and randomisation is the prevention of bias. Therefore, it is worthwhile to comprehensively examine bias at this stage.

Bias and Chicanery

While conducting clinical research, errors can be introduced voluntarily or involuntarily at a number of stages, such as design, population selection, calculating the number of samples, non-compliance with study protocol, data entry and selection of statistical method. Bias is taking sides of individuals in line with their own decisions, views and ideological preferences ( 9 ). In order for an error to lead to bias, it has to be a systematic error. Systematic errors in controlled studies generally cause the results of one group to move in a different direction as compared to the other. It has to be understood that scientific research is generally prone to errors. However, random errors (or, in other words, ‘the luck factor’-in which bias is unintended-do not lead to bias ( 10 ).

Another issue, which is different from bias, is chicanery. It is defined as voluntarily changing the interventions, results and data of patients in an unethical manner or copying data from other studies. Comparatively, bias may not be done consciously.

In case unexpected results or outliers are found while the study is analysed, if possible, such data should be re-included into the study since the complete exclusion of data from a study endangers its reliability. In such a case, evaluation needs to be made with and without outliers. It is insignificant if no difference is found. However, if there is a difference, the results with outliers are re-evaluated. If there is no error, then the outlier is included in the study (as the outlier may be a result). It should be noted that re-evaluation of data in anaesthesiology is not possible.

Statistical evaluation methods should be determined at the design stage so as not to encounter unexpected results in clinical research. The data should be evaluated before the end of the study and without entering into details in research that are time-consuming and involve several samples. This is called an interim analysis . The date of interim analysis should be determined at the beginning of the study. The purpose of making interim analysis is to prevent unnecessary cost and effort since it may be necessary to conclude the research after the interim analysis, e.g. studies in which there is no possibility to validate the hypothesis at the end or the occurrence of different side effects of the drug to be used. The accuracy of the hypothesis and number of samples are compared. Statistical significance levels in interim analysis are very important. If the data level is significant, the hypothesis is validated even if the result turns out to be insignificant after the date of the analysis.

Another important point to be considered is the necessity to conclude the participants’ treatment within the period specified in the study protocol. When the result of the study is achieved earlier and unexpected situations develop, the treatment is concluded earlier. Moreover, the participant may quit the study at its own behest, may die or unpredictable situations (e.g. pregnancy) may develop. The participant can also quit the study whenever it wants, even if the study has not ended ( 7 ).

In case the results of a study are contrary to already known or expected results, the expected quality level of the study suggesting the contradiction may be higher than the studies supporting what is known in that subject. This type of bias is called confirmation bias. The presence of well-known mechanisms and logical inference from them may create problems in the evaluation of data. This is called plausibility bias.

Another type of bias is expectation bias. If a result different from the known results has been achieved and it is against the editor’s will, it can be challenged. Bias may be introduced during the publication of studies, such as publishing only positive results, selection of study results in a way to support a view or prevention of their publication. Some editors may only publish research that extols only the positive results or results that they desire.

Bias may be introduced for advertisement or economic reasons. Economic pressure may be applied on the editor, particularly in the cases of studies involving drugs and new medical devices. This is called commercial bias.

In recent years, before beginning a study, it has been recommended to record it on the Web site www.clinicaltrials.gov for the purpose of facilitating systematic interpretation and analysis in scientific research, informing other researchers, preventing bias, provision of writing in a standard format, enhancing contribution of research results to the general literature and enabling early intervention of an institution for support. This Web site is a service of the US National Institutes of Health.

The last stage in the methodology of clinical studies is the selection of intervention to be conducted. Placebo use assumes an important place in interventions. In Latin, placebo means ‘I will be fine’. In medical literature, it refers to substances that are not curative, do not have active ingredients and have various pharmaceutical forms. Although placebos do not have active drug characteristic, they have shown effective analgesic characteristics, particularly in algology applications; further, its use prevents bias in comparative studies. If a placebo has a positive impact on a participant, it is called the placebo effect ; on the contrary, if it has a negative impact, it is called the nocebo effect . Another type of therapy that can be used in clinical research is sham application. Although a researcher does not cure the patient, the researcher may compare those who receive therapy and undergo sham. It has been seen that sham therapies also exhibit a placebo effect. In particular, sham therapies are used in acupuncture applications ( 11 ). While placebo is a substance, sham is a type of clinical application.

Ethically, the patient has to receive appropriate therapy. For this reason, if its use prevents effective treatment, it causes great problem with regard to patient health and legalities.

Before medical research is conducted with human subjects, predictable risks, drawbacks and benefits must be evaluated for individuals or groups participating in the study. Precautions must be taken for reducing the risk to a minimum level. The risks during the study should be followed, evaluated and recorded by the researcher ( 1 ).

After the methodology for a clinical study is determined, dealing with the ‘Ethics Committee’ forms the next stage. The purpose of the ethics committee is to protect the rights, safety and well-being of volunteers taking part in the clinical research, considering the scientific method and concerns of society. The ethics committee examines the studies presented in time, comprehensively and independently, with regard to ethics and science; in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and following national and international standards concerning ‘Good Clinical Practice’. The method to be followed in the formation of the ethics committee should be developed without any kind of prejudice and to examine the applications with regard to ethics and science within the framework of the ethics committee, Regulation on Clinical Trials and Good Clinical Practice ( www.iku.com ). The necessary documents to be presented to the ethics committee are research protocol, volunteer consent form, budget contract, Declaration of Helsinki, curriculum vitae of researchers, similar or explanatory literature samples, supporting institution approval certificate and patient follow-up form.

Only one sister/brother, mother, father, son/daughter and wife/husband can take charge in the same ethics committee. A rector, vice rector, dean, deputy dean, provincial healthcare director and chief physician cannot be members of the ethics committee.

Members of the ethics committee can work as researchers or coordinators in clinical research. However, during research meetings in which members of the ethics committee are researchers or coordinators, they must leave the session and they cannot sign-off on decisions. If the number of members in the ethics committee for a particular research is so high that it is impossible to take a decision, the clinical research is presented to another ethics committee in the same province. If there is no ethics committee in the same province, an ethics committee in the closest settlement is found.

Thereafter, researchers need to inform the participants using an informed consent form. This form should explain the content of clinical study, potential benefits of the study, alternatives and risks (if any). It should be easy, comprehensible, conforming to spelling rules and written in plain language understandable by the participant.

This form assists the participants in taking a decision regarding participation in the study. It should aim to protect the participants. The participant should be included in the study only after it signs the informed consent form; the participant can quit the study whenever required, even when the study has not ended ( 7 ).

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - C.Ö.Ç., A.D.; Design - C.Ö.Ç.; Supervision - A.D.; Resource - C.Ö.Ç., A.D.; Materials - C.Ö.Ç., A.D.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - C.Ö.Ç., A.D.; Literature Search - C.Ö.Ç.; Writing Manuscript - C.Ö.Ç.; Critical Review - A.D.; Other - C.Ö.Ç., A.D.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A population is a complete set of people with specified characteristics, while a sample is a subset of the population. 1 In general, most people think of the defining characteristic of a population in terms of geographic location. However, in research, other characteristics will define a population.

Methods. In this article, I review the current conventional definitions of, and historical debates over, the meaning(s) of "population," trace back the contemporary emphasis on populations as statistical rather than substantive entities to Adolphe Quetelet's powerful astronomical metaphor, conceived in the 1830s, of l'homme moyen (the average man), and argue for an alternative definition ...

Population and Target Population in Research Methodology

Context: The idea of "population" is core to the population sciences but is rarely defined except in statistical terms. Yet who and what defines and makes a population has everything to do with whether population means are meaningful or meaningless, with profound implications for work on population health and health inequities.

Learn how to define the target population, select a representative sample, and ensure the generalizability of research findings. This article covers the key aspects of population in scientific research, such as probability and non-probability sampling methods, sample size, diversity, and bias.

Learn how to identify and select the study population for answering a research question in clinical and translational studies. Compare different sampling methods, sample frames, and sample sizes based on the target population characteristics and event rates.

Learn the difference between target population, accessible population, and sample in research, and how to describe them clearly in manuscripts. The editorial also explains why the target population is important for evaluating the credibility and generalizability of the research findings.

Learn the definitions and importance of population and sample in research, and how to select a representative sample to draw valid conclusions. See examples of population and sample in teaching and learning research, and how to calculate the sample size and generalize the findings.

Study population is a subset of the target population from which the sample is selected. Learn how to define, operationalize, and generalize study population in survey research, clinical trial, and other special designs.

This article explores the historical and current debates over the meaning of "population" in population sciences, especially in relation to health outcomes and social injustice. It argues for a relational and dynamic view of population, rather than a statistical or static one, and provides examples of how this perspective can inform research and policy.

A population is a complete set of people with a specialized set of characteristics, and a sample is a subset of the population. The usual criteria we use in defining population are geographic, for example, "the population of Uttar Pradesh". In medical research, the criteria for population may be clinical, demographic and time related.

Abstract. After defining the research question, a study must identify the study population to assess. Study populations can include a whole target population (i.e., census); however, most studies include sampling, in which the sample represents a subset of the target population. When deciding to sample, an important consideration is the sample ...

Learn the concepts of population and sample in research, and how to select a representative sample for data collection and statistical inference. Compare the advantages and disadvantages of sampling and population-level data collection, and understand the key steps in the sampling process.

(PDF) CONCEPT OF POPULATION AND SAMPLE

design, population of interest, study setting, recruit ment, and sampling. Study Design. The study design is the use of e vidence-based. procedures, protocols, and guidelines that provide the ...

Population demographics is the study of the characteristics and dynamics of populations. Learn about population size, density, age structure, fecundity, mortality, and sex ratio, and how they ...

A research population is a large group of individuals or objects that are the focus of a scientific study. Learn about the two types of population (target and accessible) and how they relate to sampling techniques and conclusions.

The truth table depicted in Table 1 gauged the strengths and weaknesses of the four different existing CTSC lists against the emerging definition of what constituted a member of the new fifth "Affiliated" (shaded far right-hand column on Table 1) study population list. The three authors had 17 combined years of experience in working with ...

Abstract. Population Studies advances research on fertility, mortality, family, migration, methods, policy, and beyond, yet it lacks a recent, rigorous review. We examine all papers published between 1947 and 2020 (N = 1,901) and their authors, using natural language processing, social network analysis, and mixed methods that combine unsupervised machine learning with qualitative coding.

The second edition of An Introduction to Population provides a clear, well-written and informative introductory text-book for population studies, particularly for students from other disciplinary backgrounds taking options in population studies, many of whom will have no prior knowledge of the subject. To engage students' interest in population studies, the authors are primarily concerned ...

The study depicts how the research goal, contexts and assumptions can dictate the content and concentration of the target and accessible population in qualitative inquiry.

Understanding and Evaluating Survey Research - PMC

What is Scientific Research and How Can it be Done? - PMC