- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- The Lit Hub Podcast

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)

The newly minted MacArthur fellow Valeria Luiselli’s four-part (but really six-part) essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions was inspired by her time spent volunteering at the federal immigration court in New York City, working as an interpreter for undocumented, unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Written concurrently with her novel Lost Children Archive (a fictional exploration of the same topic), Luiselli’s essay offers a fascinating conceit, the fashioning of an argument from the questions on the government intake form given to these children to process their arrivals. (Aside from the fact that this essay is a heartbreaking masterpiece, this is such a good conceit—transforming a cold, reproducible administrative document into highly personal literature.) Luiselli interweaves a grounded discussion of the questionnaire with a narrative of the road trip Luiselli takes with her husband and family, across America, while they (both Mexican citizens) wait for their own Green Card applications to be processed. It is on this trip when Luiselli reflects on the thousands of migrant children mysteriously traveling across the border by themselves. But the real point of the essay is to actually delve into the real stories of some of these children, which are agonizing, as well as to gravely, clearly expose what literally happens, procedural, when they do arrive—from forms to courts, as they’re swallowed by a bureaucratic vortex. Amid all of this, Luiselli also takes on more, exploring the larger contextual relationship between the United States of America and Mexico (as well as other countries in Central America, more broadly) as it has evolved to our current, adverse moment. Tell Me How It Ends is so small, but it is so passionate and vigorous: it desperately accomplishes in its less-than-100-pages-of-prose what centuries and miles and endless records of federal bureaucracy have never been able, and have never cared, to do: reverse the dehumanization of Latin American immigrants that occurs once they set foot in this country. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

In the essay “Meet Justin Bieber!” in Feel Free , Zadie Smith writes that her interest in Justin Bieber is not an interest in the interiority of the singer himself, but in “the idea of the love object”. This essay—in which Smith imagines a meeting between Bieber and the late philosopher Martin Buber (“Bieber and Buber are alternative spellings of the same German surname,” she explains in one of many winning footnotes. “Who am I to ignore these hints from the universe?”). Smith allows that this premise is a bit premise -y: “I know, I know.” Still, the resulting essay is a very funny, very smart, and un-tricky exploration of individuality and true “meeting,” with a dash of late capitalism thrown in for good measure. The melding of high and low culture is the bread and butter of pretty much every prestige publication on the internet these days (and certainly of the Twitter feeds of all “public intellectuals”), but the essays in Smith’s collection don’t feel familiar—perhaps because hers is, as we’ve long known, an uncommon skill. Though I believe Smith could probably write compellingly about anything, she chooses her subjects wisely. She writes with as much electricity about Brexit as the aforementioned Beliebers—and each essay is utterly engrossing. “She contains multitudes, but her point is we all do,” writes Hermione Hoby in her review of the collection in The New Republic . “At the same time, we are, in our endless difference, nobody but ourselves.” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick: And Other Essays (2019)

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an academic who has transcended the ivory tower to become the sort of public intellectual who can easily appear on radio or television talk shows to discuss race, gender, and capitalism. Her collection of essays reflects this duality, blending scholarly work with memoir to create a collection on the black female experience in postmodern America that’s “intersectional analysis with a side of pop culture.” The essays range from an analysis of sexual violence, to populist politics, to social media, but in centering her own experiences throughout, the collection becomes something unlike other pieces of criticism of contemporary culture. In explaining the title, she reflects on what an editor had said about her work: “I was too readable to be academic, too deep to be popular, too country black to be literary, and too naïve to show the rigor of my thinking in the complexity of my prose. I had wanted to create something meaningful that sounded not only like me, but like all of me. It was too thick.” One of the most powerful essays in the book is “Dying to be Competent” which begins with her unpacking the idiocy of LinkedIn (and the myth of meritocracy) and ends with a description of her miscarriage, the mishandling of black woman’s pain, and a condemnation of healthcare bureaucracy. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Thick confirms McMillan Cottom as one of our most fearless public intellectuals and one of the most vital. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Elif Batuman, The Possessed (2010)

In The Possessed Elif Batuman indulges her love of Russian literature and the result is hilarious and remarkable. Each essay of the collection chronicles some adventure or other that she had while in graduate school for Comparative Literature and each is more unpredictable than the next. There’s the time a “well-known 20th-centuryist” gave a graduate student the finger; and the time when Batuman ended up living in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for a summer; and the time that she convinced herself Tolstoy was murdered and spent the length of the Tolstoy Conference in Yasnaya Polyana considering clues and motives. Rich in historic detail about Russian authors and literature and thoughtfully constructed, each essay is an amalgam of critical analysis, cultural criticism, and serious contemplation of big ideas like that of identity, intellectual legacy, and authorship. With wit and a serpentine-like shape to her narratives, Batuman adopts a form reminiscent of a Socratic discourse, setting up questions at the beginning of her essays and then following digressions that more or less entreat the reader to synthesize the answer for herself. The digressions are always amusing and arguably the backbone of the collection, relaying absurd anecdotes with foreign scholars or awkward, surreal encounters with Eastern European strangers. Central also to the collection are Batuman’s intellectual asides where she entertains a theory—like the “problem of the person”: the inability to ever wholly capture one’s character—that ultimately layer the book’s themes. “You are certainly my most entertaining student,” a professor said to Batuman. But she is also curious and enthusiastic and reflective and so knowledgeable that she might even convince you (she has me!) that you too love Russian literature as much as she does. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist (2014)

Roxane Gay’s now-classic essay collection is a book that will make you laugh, think, cry, and then wonder, how can cultural criticism be this fun? My favorite essays in the book include Gay’s musings on competitive Scrabble, her stranded-in-academia dispatches, and her joyous film and television criticism, but given the breadth of topics Roxane Gay can discuss in an entertaining manner, there’s something for everyone in this one. This book is accessible because feminism itself should be accessible – Roxane Gay is as likely to draw inspiration from YA novels, or middle-brow shows about friendship, as she is to introduce concepts from the academic world, and if there’s anyone I trust to bridge the gap between high culture, low culture, and pop culture, it’s the Goddess of Twitter. I used to host a book club dedicated to radical reads, and this was one of the first picks for the club; a week after the book club met, I spied a few of the attendees meeting in the café of the bookstore, and found out that they had bonded so much over discussing Bad Feminist that they couldn’t wait for the next meeting of the book club to keep discussing politics and intersectionality, and that, in a nutshell, is the power of Roxane. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (2016)

Generally, I find stories about the trials and tribulations of child-having to be of limited appeal—useful, maybe, insofar as they offer validation that other people have also endured the bizarre realities of living with a tiny human, but otherwise liable to drift into the musings of parents thrilled at the simple fact of their own fecundity, as if they were the first ones to figure the process out (or not). But Little Labors is not simply an essay collection about motherhood, perhaps because Galchen initially “didn’t want to write about” her new baby—mostly, she writes, “because I had never been interested in babies, or mothers; in fact, those subjects had seemed perfectly not interesting to me.” Like many new mothers, though, Galchen soon discovered her baby—which she refers to sometimes as “the puma”—to be a preoccupying thought, demanding to be written about. Galchen’s interest isn’t just in her own progeny, but in babies in literature (“Literature has more dogs than babies, and also more abortions”), The Pillow Book , the eleventh-century collection of musings by Sei Shōnagon, and writers who are mothers. There are sections that made me laugh out loud, like when Galchen continually finds herself in an elevator with a neighbor who never fails to remark on the puma’s size. There are also deeper, darker musings, like the realization that the baby means “that it’s not permissible to die. There are days when this does not feel good.” It is a slim collection that I happened to read at the perfect time, and it remains one of my favorites of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Charlie Fox, This Young Monster (2017)

On social media as in his writing, British art critic Charlie Fox rejects lucidity for allusion and doesn’t quite answer the Twitter textbox’s persistent question: “What’s happening?” These days, it’s hard to tell. This Young Monster (2017), Fox’s first book,was published a few months after Donald Trump’s election, and at one point Fox takes a swipe at a man he judges “direct from a nightmare and just a repulsive fucking goon.” Fox doesn’t linger on politics, though, since most of the monsters he looks at “embody otherness and make it into art, ripping any conventional idea of beauty to shreds and replacing it with something weird and troubling of their own invention.”

If clichés are loathed because they conform to what philosopher Georges Bataille called “the common measure,” then monsters are rebellious non-sequiturs, comedic or horrific derailments from a classical ideal. Perverts in the most literal sense, monsters have gone astray from some “proper” course. The book’s nine chapters, which are about a specific monster or type of monster, are full of callbacks to familiar and lesser-known media. Fox cites visual art, film, songs, and books with the screwy buoyancy of a savant. Take one of his essays, “Spook House,” framed as a stage play with two principal characters, Klaus (“an intoxicated young skinhead vampire”) and Hermione (“a teen sorceress with green skin and jet-black hair” who looks more like The Wicked Witch than her namesake). The chorus is a troupe of trick-or-treaters. Using the filmmaker Cameron Jamie as a starting point, the rest is free association on gothic decadence and Detroit and L.A. as cities of the dead. All the while, Klaus quotes from Artforum , Dazed & Confused , and Time Out. It’s a technical feat that makes fictionalized dialogue a conveyor belt for cultural criticism.

In Fox’s imagination, David Bowie and the Hydra coexist alongside Peter Pan, Dennis Hopper, and the maenads. Fox’s book reaches for the monster’s mask, not really to peel it off but to feel and smell the rubber schnoz, to know how it’s made before making sure it’s still snugly set. With a stylistic blend of arthouse suavity and B-movie chic, This Young Monster considers how monsters in culture are made. Aren’t the scariest things made in post-production? Isn’t the creature just duplicity, like a looping choir or a dubbed scream? –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Elena Passarello, Animals Strike Curious Poses (2017)

Elena Passarello’s collection of essays Animals Strike Curious Poses picks out infamous animals and grants them the voice, narrative, and history they deserve. Not only is a collection like this relevant during the sixth extinction but it is an ambitious historical and anthropological undertaking, which Passarello has tackled with thorough research and a playful tone that rather than compromise her subject, complicates and humanizes it. Passarello’s intention is to investigate the role of animals across the span of human civilization and in doing so, to construct a timeline of humanity as told through people’s interactions with said animals. “Of all the images that make our world, animal images are particularly buried inside us,” Passarello writes in her first essay, to introduce us to the object of the book and also to the oldest of her chosen characters: Yuka, a 39,000-year-old mummified woolly mammoth discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2010. It was an occasion so remarkable and so unfathomable given the span of human civilization that Passarello says of Yuka: “Since language is epically younger than both thought and experience, ‘woolly mammoth’ means, to a human brain, something more like time.” The essay ends with a character placing a hand on a cave drawing of a woolly mammoth, accompanied by a phrase which encapsulates the author’s vision for the book: “And he becomes the mammoth so he can envision the mammoth.” In Passarello’s hands the imagined boundaries between the animal, natural, and human world disintegrate and what emerges is a cohesive if baffling integrated history of life. With the accuracy and tenacity of a journalist and the spirit of a storyteller, Elena Passarello has assembled a modern bestiary worthy of contemplation and awe. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (2019)

Esmé Weijun Wang’s collection of essays is a kaleidoscopic look at mental health and the lives affected by the schizophrenias. Each essay takes on a different aspect of the topic, but you’ll want to read them together for a holistic perspective. Esmé Weijun Wang generously begins The Collected Schizophrenias by acknowledging the stereotype, “Schizophrenia terrifies. It is the archetypal disorder of lunacy.” From there, she walks us through the technical language, breaks down the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual ( DSM-5 )’s clinical definition. And then she gets very personal, telling us about how she came to her own diagnosis and the way it’s touched her daily life (her relationships, her ideas about motherhood). Esmé Weijun Wang is uniquely situated to write about this topic. As a former lab researcher at Stanford, she turns a precise, analytical eye to her experience while simultaneously unfolding everything with great patience for her reader. Throughout, she brilliantly dissects the language around mental health. (On saying “a person living with bipolar disorder” instead of using “bipolar” as the sole subject: “…we are not our diseases. We are instead individuals with disorders and malfunctions. Our conditions lie over us like smallpox blankets; we are one thing and the illness is another.”) She pinpoints the ways she arms herself against anticipated reactions to the schizophrenias: high fashion, having attended an Ivy League institution. In a particularly piercing essay, she traces mental illness back through her family tree. She also places her story within more mainstream cultural contexts, calling on groundbreaking exposés about the dangerous of institutionalization and depictions of mental illness in television and film (like the infamous Slender Man case, in which two young girls stab their best friend because an invented Internet figure told them to). At once intimate and far-reaching, The Collected Schizophrenias is an informative and important (and let’s not forget artful) work. I’ve never read a collection quite so beautifully-written and laid-bare as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights (2019)

When Ross Gay began writing what would become The Book of Delights, he envisioned it as a project of daily essays, each focused on a moment or point of delight in his day. This plan quickly disintegrated; on day four, he skipped his self-imposed assignment and decided to “in honor and love, delight in blowing it off.” (Clearly, “blowing it off” is a relative term here, as he still produced the book.) Ross Gay is a generous teacher of how to live, and this moment of reveling in self-compassion is one lesson among many in The Book of Delights , which wanders from moments of connection with strangers to a shade of “red I don’t think I actually have words for,” a text from a friend reading “I love you breadfruit,” and “the sun like a guiding hand on my back, saying everything is possible. Everything .”

Gay does not linger on any one subject for long, creating the sense that delight is a product not of extenuating circumstances, but of our attention; his attunement to the possibilities of a single day, and awareness of all the small moments that produce delight, are a model for life amid the warring factions of the attention economy. These small moments range from the physical–hugging a stranger, transplanting fig cuttings–to the spiritual and philosophical, giving the impression of sitting beside Gay in his garden as he thinks out loud in real time. It’s a privilege to listen. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Terry Castle, The Professor and Other Writings (2010) · Joyce Carol Oates, In Rough Country (2010) · Geoff Dyer, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011) · Christopher Hitchens, Arguably (2011) · Roberto Bolaño, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Between Parentheses (2011) · Dubravka Ugresic, tr. David Williams, Karaoke Culture (2011) · Tom Bissell, Magic Hours (2012) · Kevin Young, The Grey Album (2012) · William H. Gass, Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts (2012) · Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey (2012) · Herta Müller, tr. Geoffrey Mulligan, Cristina and Her Double (2013) · Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams (2014) · Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable (2014) · Daphne Merkin, The Fame Lunches (2014) · Charles D’Ambrosio, Loitering (2015) · Wendy Walters, Multiply/Divide (2015) · Colm Tóibín, On Elizabeth Bishop (2015) · Renee Gladman, Calamities (2016) · Jesmyn Ward, ed. The Fire This Time (2016) · Lindy West, Shrill (2016) · Mary Oliver, Upstream (2016) · Emily Witt, Future Sex (2016) · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (2016) · Mark Greif, Against Everything (2016) · Durga Chew-Bose, Too Much and Not the Mood (2017) · Sarah Gerard, Sunshine State (2017) · Jim Harrison, A Really Big Lunch (2017) · J.M. Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (2017) · Melissa Febos, Abandon Me (2017) · Louise Glück, American Originality (2017) · Joan Didion, South and West (2017) · Tom McCarthy, Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish (2017) · Hanif Abdurraqib, They Can’t Kill Us Until they Kill Us (2017) · Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power (2017) · Samantha Irby, We Are Never Meeting in Real Life (2017) · Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (2018) · Alice Bolin, Dead Girls (2018) · Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here? (2018) · Lorrie Moore, See What Can Be Done (2018) · Maggie O’Farrell, I Am I Am I Am (2018) · Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk About Race (2018) · Rachel Cusk, Coventry (2019) · Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror (2019) · Emily Bernard, Black is the Body (2019) · Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard (2019) · Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations (2019) · Rachel Munroe, Savage Appetites (2019) · Robert A. Caro, Working (2019) · Arundhati Roy, My Seditious Heart (2019).

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

31 Of The Most Beautiful And Profound Passages In Literature You’ll Want To Read Over And Over Again

- https://thoughtcatalog.com/?p=493373

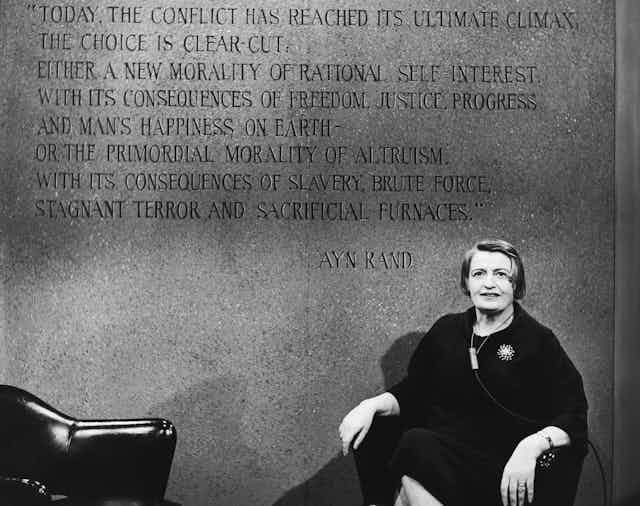

Whenever I’m feeling uninspired I look to a collection of my favorite literary quotes I keep in a document on my computer. Today was one of those days. As I was re-reading some of these and remembering why I love writing, reading, and the power of words and a good story, I thought perhaps someone somewhere out there might be feeling the same as me this morning. Here are 31 of the most beautiful passages in literature .

“Atticus said to Jem one day, “I’d rather you shot at tin cans in the backyard, but I know you’ll go after birds. Shoot all the blue jays you want, if you can hit ‘em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” That was the only time I ever heard Atticus say it was a sin to do something, and I asked Miss Maudie about it. “Your father’s right,” she said. “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing except make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corn cribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.” – Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

“i took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. i am, i am, i am.” – sylvia plath, the bell jar, “we believe that we can change the things around us in accordance with our desires—we believe it because otherwise we can see no favourable outcome. we do not think of the outcome which generally comes to pass and is also favourable: we do not succeed in changing things in accordance with our desires, but gradually our desires change. the situation that we hoped to change because it was intolerable becomes unimportant to us. we have failed to surmount the obstacle, as we were absolutely determined to do, but life has taken us round it, led us beyond it, and then if we turn round to gaze into the distance of the past, we can barely see it, so imperceptible has it become.” – marcel proust, in search of lost time, “the most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or touched, they are felt with the heart.” – antoine de saint-exupéry, the little prince, “hello babies. welcome to earth. it’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. it’s round and wet and crowded. on the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. there’s only one rule that i know of, babies-“god damn it, you’ve got to be kind.” – kurt vonnegut, god bless you, mr. rosewater, “why, sometimes i’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.” – lewis carroll, alice in wonderland, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” – oscar wilde, lady windermere’s fan, “i must not fear. fear is the mind-killer. fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. i will face my fear. i will permit it to pass over me and through me. and when it has gone past i will turn the inner eye to see its path. where the fear has gone there will be nothing. only i will remain.” – frank herbert, dune, “nolite te bastardes carborundorum.” (don’t let the bastards grind you down) – margaret atwood, the handmaid’s tale, “just remember that the things you put into your head are there forever, he said. you might want to think about that. you forget some things, dont you yes. you forget what you want to remember and you remember what you want to forget.” – cormac mccarthy, the road, “you can tell yourself that you would be willing to lose everything you have in order to get something you want. but it’s a catch-22: all of those things you’re willing to lose are what make you recognizable. lose them, and you’ve lost yourself.” – jodi picoult, handle with care, “the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.” – jack kerouac, on the road, “he allowed himself to be swayed by his conviction that human beings are not born once and for all on the day their mothers give birth to them, but that life obliges them over and over again to give birth to themselves.” ― gabriel garcía márquez, love in the time of cholera, “there is an idea of a patrick bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though i can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: i simply am not there.” – bret easton ellis, american psycho, “sometimes fate is like a small sandstorm that keeps changing directions. you change direction but the sandstorm chases you. you turn again, but the storm adjusts. over and over you play this out, like some ominous dance with death just before dawn. why because this storm isn’t something that blew in from far away, something that has nothing to do with you. this storm is you. something inside of you. so all you can do is give in to it, step right inside the storm, closing your eyes and plugging up your ears so the sand doesn’t get in, and walk through it, step by step. there’s no sun there, no moon, no direction, no sense of time. just fine white sand swirling up into the sky like pulverized bones. that’s the kind of sandstorm you need to imagine., and you really will have to make it through that violent, metaphysical, symbolic storm. no matter how metaphysical or symbolic it might be, make no mistake about it: it will cut through flesh like a thousand razor blades. people will bleed there, and you will bleed too. hot, red blood. you’ll catch that blood in your hands, your own blood and the blood of others., and once the storm is over you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. you won’t even be sure, in fact, whether the storm is really over. but one thing is certain. when you come out of the storm you won’t be the same person who walked in. that’s what this storm’s all about.” – haruki murakami, kafka on the shore, “a heart is not judged by how much you love; but by how much you are loved by others” – l. frank baum, the wonderful wizard of oz, “sometimes i can hear my bones straining under the weight of all the lives i’m not living.”- jonathan safran foer, extremely loud and incredibly close, “the most important things are the hardest to say. they are the things you get ashamed of, because words diminish them — words shrink things that seemed limitless when they were in your head to no more than living size when they’re brought out. but it’s more than that, isn’t it the most important things lie too close to wherever your secret heart is buried, like landmarks to a treasure your enemies would love to steal away. and you may make revelations that cost you dearly only to have people look at you in a funny way, not understanding what you’ve said at all, or why you thought it was so important that you almost cried while you were saying it. that’s the worst, i think. when the secret stays locked within not for want of a teller but for want of an understanding ear.” stephen king, different seasons, “i don’t have any problem understanding why people flunk out of college or quit their jobs or cheat on each other or break the law or spray-paint walls. a little bit outside of things is where some people feel each other. we do it to replace the frame of family. we do it to erase and remake our origins in their own images. to say, i too was here.” – lidia yuknavitch, the chronology of water, “i never believed in santa claus. none of us kids did. mom and dad refused to let us. they couldn’t afford expensive presents and they didn’t want us to think we weren’t as good as other kids who, on christmas morning, found all sorts of fancy toys under the tree that were supposedly left by santa claus. dad had lost his job at the gypsum, and when christmas came that year, we had no money at all. on christmas eve, dad took each one of us kids out into the desert night one by one., “pick out your favorite star”, dad said., “i like that one” i said., dad grinned, “that’s venus”, he said. he explained to me that planets glowed because reflected light was constant and stars twinkled because their light pulsed., “i like it anyway” i said., “what the hell,” dad said. “it’s christmas. you can have a planet if you want.” and he gave me venus., venus didn’t have any moons or satellites or even a magnetic field, but it did have an atmosphere sort of similar to earth’s, except it was super hot-about 500 degrees or more. “so,” dad said, “when the sun starts to burn out and earth turns cold, everyone might want to move to venus to get warm. and they’ll have to get permission from your descendants first., we laughed about all the kids who believed in the santa myth and got nothing for christmas but a bunch of cheap plastic toys. “years from now, when all the junk they got is broken and long forgotten,” dad said, “you’ll still have your stars.” – jeannette walls, the glass castle, “lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. my sin, my soul. lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. lo. lee. ta. she was lo, plain lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. she was lola in slacks. she was dolly at school. she was dolores on the dotted line. but in my arms she was always lolita. did she have a precursor she did, indeed she did. in point of fact, there might have been no lolita at all had i not loved, one summer, an initial girl-child. in a princedom by the sea. oh when about as many years before lolita was born as my age was that summer. you can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style. ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. look at this tangle of thorns.” vladimir nabokov, lolita, “you think because he doesn’t love you that you are worthless. you think that because he doesn’t want you anymore that he is right — that his judgement and opinion of you are correct. if he throws you out, then you are garbage. you think he belongs to you because you want to belong to him. don’t. it’s a bad word, ‘belong.’ especially when you put it with somebody you love. love shouldn’t be like that. did you ever see the way the clouds love a mountain they circle all around it; sometimes you can’t even see the mountain for the clouds. but you know what you go up top and what do you see his head. the clouds never cover the head. his head pokes through, beacuse the clouds let him; they don’t wrap him up. they let him keep his head up high, free, with nothing to hide him or bind him. you can’t own a human being. you can’t lose what you don’t own. suppose you did own him. could you really love somebody who was absolutely nobody without you you really want somebody like that somebody who falls apart when you walk out the door you don’t, do you and neither does he. you’re turning over your whole life to him. your whole life, girl. and if it means so little to you that you can just give it away, hand it to him, then why should it mean any more to him he can’t value you more than you value yourself.” – toni morrison, song of solomon, “…i think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. we forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. we forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.” ― joan didion, slouching towards bethlehem, “i don’t let anyone touch me,” i finally said. why not” why not because i was tired of men. hanging in doorways, standing too close, their smell of beer or fifteen-year-old whiskey. men who didn’t come to the emergency room with you, men who left on christmas eve. men who slammed the security gates, who made you love them then changed their minds. forests of boys, their ragged shrubs full of eyes following you, grabbing your breasts, waving their money, eyes already knocking you down, taking what they felt was theirs. (…) it was a play and i knew how it ended, i didn’t want to audition for any of the roles. it was no game, no casual thrill. it was three-bullet russian roulette.” – janet fitch, white oleander, “i wanted so badly to lie down next to her on the couch, to wrap my arms around her and sleep. not fuck, like in those movies. not even have sex. just sleep together in the most innocent sense of the phrase. but i lacked the courage and she had a boyfriend and i was gawky and she was gorgeous and i was hopelessly boring and she was endlessly fascinating. so i walked back to my room and collapsed on the bottom bunk, thinking that if people were rain, i was drizzle and she was hurricane.” ― john green, looking for alaska, “but i tried, didn’t i goddamnit, at least i did that.” – ken kesey, one flew over the cuckoo’s nest, “if you’re going to try, go all the way. otherwise, don’t even start. this could mean losing girlfriends, wives, relatives and maybe even your mind. it could mean not eating for three or four days. it could mean freezing on a park bench. it could mean jail. it could mean derision. it could mean mockery–isolation. isolation is the gift. all the others are a test of your endurance, of how much you really want to do it. and, you’ll do it, despite rejection and the worst odds. and it will be better than anything else you can imagine. if you’re going to try, go all the way. there is no other feeling like that. you will be alone with the gods, and the nights will flame with fire. you will ride life straight to perfect laughter. it’s the only good fight there is.” ― charles bukowski, factotum, “i will be very careful the next time i fall in love, she told herself. also, she had made a promise to herself that she intended on keeping. she was never going to go out with another writer: no matter how charming, sensitive, inventive or fun they could be. they weren’t worth it in the long run. they were emotionally too expensive and the upkeep was complicated. they were like having a vacuum cleaner around the house that broke all the time and only einstein could fix it. she wanted her next lover to be a broom.” ― richard brautigan, sombrero fallout, “usually we walk around constantly believing ourselves. “i’m okay” we say. “i’m alright”. but sometimes the truth arrives on you and you can’t get it off. that’s when you realize that sometimes it isn’t even an answer–it’s a question. even now, i wonder how much of my life is convinced.” ― markus zusak, the book thief, “i love you without knowing how, or when, or from where. i love you simply, without problems or pride: i love you in this way because i do not know any other way of loving but this, in which there is no i or you, so intimate that your hand upon my chest is my hand, so intimate that when i fall asleep your eyes close.” ― pablo neruda, 100 love sonnets, “it doesn’t interest me what you do for a living. i want to know what you ache for, and if you dare to dream of meeting your heart’s longing., it doesn’t interest me how old you are. i want to know if you will risk looking like a fool for love, for your dream, for the adventure of being alive., it doesn’t interest me what planets are squaring your moon. i want to know if you have touched the center of your own sorrow, if you have been opened by life’s betrayals or have become shriveled and closed from fear of further paini want to know if you can sit with pain, mine or your own, without moving to hide it or fade it, or fix it., i want to know if you can be with joy, mine or your own, if you can dance with wildness and let the ecstasy fill you to the tips of your fingers and toes without cautioning us to be careful, to be realistic, to remember the limitations of being human., it doesn’t interest me if the story you are telling me is true. i want to know if you can disappoint another to be true to yourself; if you can bear the accusation of betrayal and not betray your own soul; if you can be faithless and therefore trustworthy., i want to know if you can see beauty even when it’s not pretty, every day,and if you can source your own life from its presence., i want to know if you can live with failure, yours and mine, and still stand on the edge of the lake and shout to the silver of the full moon, “yes”, it doesn’t interest me to know where you live or how much money you have. i want to know if you can get up, after the night of grief and despair, weary and bruised to the bone, and do what needs to be done to feed the children., it doesn’t interest me who you know or how you came to be here. i want to know if you will stand in the center of the fire with me and not shrink back., it doesn’t interest me where or what or with whom you have studied. i want to know what sustains you, from the inside, when all else falls away., i want to know if you can be alone with yourself and if you truly like the company you keep in the empty moments.”, ― oriah mountain dreamer, the invitation.

About the author

Koty Neelis

Former senior staff writer and producer at Thought Catalog.

More From Thought Catalog

You Are More Than Your Addiction

7 Spy Thrillers That Turn Up The Romance

12 Of The Biggest Revelations From Hulu’s Documentary ‘Child Star’

3 Ways To Celebrate ‘Challengers’ Now Streaming Online

42 Things To Do In Your 20s Besides Chase After Love

The True Reason Why Breakups Are Emotionally Devastating

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

187 College Essay Examples for 11 Schools + Expert Analysis

College Admissions , College Essays

The personal statement might just be the hardest part of your college application. Mostly this is because it has the least guidance and is the most open-ended. One way to understand what colleges are looking for when they ask you to write an essay is to check out the essays of students who already got in—college essays that actually worked. After all, they must be among the most successful of this weird literary genre.

In this article, I'll go through general guidelines for what makes great college essays great. I've also compiled an enormous list of 100+ actual sample college essays from 11 different schools. Finally, I'll break down two of these published college essay examples and explain why and how they work. With links to 187 full essays and essay excerpts , this article is a great resource for learning how to craft your own personal college admissions essay!

What Excellent College Essays Have in Common

Even though in many ways these sample college essays are very different from one other, they do share some traits you should try to emulate as you write your own essay.

Visible Signs of Planning

Building out from a narrow, concrete focus. You'll see a similar structure in many of the essays. The author starts with a very detailed story of an event or description of a person or place. After this sense-heavy imagery, the essay expands out to make a broader point about the author, and connects this very memorable experience to the author's present situation, state of mind, newfound understanding, or maturity level.

Knowing how to tell a story. Some of the experiences in these essays are one-of-a-kind. But most deal with the stuff of everyday life. What sets them apart is the way the author approaches the topic: analyzing it for drama and humor, for its moving qualities, for what it says about the author's world, and for how it connects to the author's emotional life.

Stellar Execution

A killer first sentence. You've heard it before, and you'll hear it again: you have to suck the reader in, and the best place to do that is the first sentence. Great first sentences are punchy. They are like cliffhangers, setting up an exciting scene or an unusual situation with an unclear conclusion, in order to make the reader want to know more. Don't take my word for it—check out these 22 first sentences from Stanford applicants and tell me you don't want to read the rest of those essays to find out what happens!

A lively, individual voice. Writing is for readers. In this case, your reader is an admissions officer who has read thousands of essays before yours and will read thousands after. Your goal? Don't bore your reader. Use interesting descriptions, stay away from clichés, include your own offbeat observations—anything that makes this essay sounds like you and not like anyone else.

Technical correctness. No spelling mistakes, no grammar weirdness, no syntax issues, no punctuation snafus—each of these sample college essays has been formatted and proofread perfectly. If this kind of exactness is not your strong suit, you're in luck! All colleges advise applicants to have their essays looked over several times by parents, teachers, mentors, and anyone else who can spot a comma splice. Your essay must be your own work, but there is absolutely nothing wrong with getting help polishing it.

And if you need more guidance, connect with PrepScholar's expert admissions consultants . These expert writers know exactly what college admissions committees look for in an admissions essay and chan help you craft an essay that boosts your chances of getting into your dream school.

Check out PrepScholar's Essay Editing and Coaching progra m for more details!

Links to Full College Essay Examples

Some colleges publish a selection of their favorite accepted college essays that worked, and I've put together a selection of over 100 of these.

Common App Essay Samples

Please note that some of these college essay examples may be responding to prompts that are no longer in use. The current Common App prompts are as follows:

1. Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story. 2. The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience? 3. Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. What prompted your thinking? What was the outcome? 4. Reflect on something that someone has done for you that has made you happy or thankful in a surprising way. How has this gratitude affected or motivated you? 5. Discuss an accomplishment, event, or realization that sparked a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others. 6. Describe a topic, idea, or concept you find so engaging that it makes you lose all track of time. Why does it captivate you? What or who do you turn to when you want to learn more?

7. Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you've already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one of your own design.

Now, let's get to the good stuff: the list of 187 college essay examples responding to current and past Common App essay prompts.

Connecticut college.

- 12 Common Application essays from the classes of 2022-2025

Hamilton College

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2026

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2022

- 7 Common Application essays from the class of 2018

- 8 Common Application essays from the class of 2012

- 8 Common Application essays from the class of 2007

Johns Hopkins

These essays are answers to past prompts from either the Common Application or the Coalition Application (which Johns Hopkins used to accept).

- 1 Common Application or Coalition Application essay from the class of 2026

- 6 Common Application or Coalition Application essays from the class of 2025

- 6 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2024

- 6 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2023

- 7 Common Application of Universal Application essays from the class of 2022

- 5 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2021

- 7 Common Application or Universal Application essays from the class of 2020

Essay Examples Published by Other Websites

- 2 Common Application essays ( 1st essay , 2nd essay ) from applicants admitted to Columbia

Other Sample College Essays

Here is a collection of essays that are college-specific.

Babson College

- 4 essays (and 1 video response) on "Why Babson" from the class of 2020

Emory University

- 5 essay examples ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) from the class of 2020 along with analysis from Emory admissions staff on why the essays were exceptional

- 5 more recent essay examples ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) along with analysis from Emory admissions staff on what made these essays stand out

University of Georgia

- 1 “strong essay” sample from 2019

- 1 “strong essay” sample from 2018

- 10 Harvard essays from 2024

- 10 Harvard essays from 2023

- 10 Harvard essays from 2022

- 10 Harvard essays from 2021

- 10 Harvard essays from 2020

- 10 Harvard essays from 2019

- 10 Harvard essays from 2018

- 6 essays from admitted MIT students

Smith College

- 6 "best gift" essays from the class of 2018

Books of College Essays

If you're looking for even more sample college essays, consider purchasing a college essay book. The best of these include dozens of essays that worked and feedback from real admissions officers.

College Essays That Made a Difference —This detailed guide from Princeton Review includes not only successful essays, but also interviews with admissions officers and full student profiles.

50 Successful Harvard Application Essays by the Staff of the Harvard Crimson—A must for anyone aspiring to Harvard .

50 Successful Ivy League Application Essays and 50 Successful Stanford Application Essays by Gen and Kelly Tanabe—For essays from other top schools, check out this venerated series, which is regularly updated with new essays.

Analyzing Great Common App Essays That Worked

I've picked two essays from the examples collected above to examine in more depth so that you can see exactly what makes a successful college essay work. Full credit for these essays goes to the original authors and the schools that published them.

Example 1: "Breaking Into Cars," by Stephen, Johns Hopkins Class of '19 (Common App Essay, 636 words long)

I had never broken into a car before.

We were in Laredo, having just finished our first day at a Habitat for Humanity work site. The Hotchkiss volunteers had already left, off to enjoy some Texas BBQ, leaving me behind with the college kids to clean up. Not until we were stranded did we realize we were locked out of the van.

Someone picked a coat hanger out of the dumpster, handed it to me, and took a few steps back.

"Can you do that thing with a coat hanger to unlock it?"

"Why me?" I thought.

More out of amusement than optimism, I gave it a try. I slid the hanger into the window's seal like I'd seen on crime shows, and spent a few minutes jiggling the apparatus around the inside of the frame. Suddenly, two things simultaneously clicked. One was the lock on the door. (I actually succeeded in springing it.) The other was the realization that I'd been in this type of situation before. In fact, I'd been born into this type of situation.

My upbringing has numbed me to unpredictability and chaos. With a family of seven, my home was loud, messy, and spottily supervised. My siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing—all meant my house was functioning normally. My Dad, a retired Navy pilot, was away half the time. When he was home, he had a parenting style something like a drill sergeant. At the age of nine, I learned how to clear burning oil from the surface of water. My Dad considered this a critical life skill—you know, in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed. "The water's on fire! Clear a hole!" he shouted, tossing me in the lake without warning. While I'm still unconvinced about that particular lesson's practicality, my Dad's overarching message is unequivocally true: much of life is unexpected, and you have to deal with the twists and turns.

Living in my family, days rarely unfolded as planned. A bit overlooked, a little pushed around, I learned to roll with reality, negotiate a quick deal, and give the improbable a try. I don't sweat the small stuff, and I definitely don't expect perfect fairness. So what if our dining room table only has six chairs for seven people? Someone learns the importance of punctuality every night.

But more than punctuality and a special affinity for musical chairs, my family life has taught me to thrive in situations over which I have no power. Growing up, I never controlled my older siblings, but I learned how to thwart their attempts to control me. I forged alliances, and realigned them as necessary. Sometimes, I was the poor, defenseless little brother; sometimes I was the omniscient elder. Different things to different people, as the situation demanded. I learned to adapt.

Back then, these techniques were merely reactions undertaken to ensure my survival. But one day this fall, Dr. Hicks, our Head of School, asked me a question that he hoped all seniors would reflect on throughout the year: "How can I participate in a thing I do not govern, in the company of people I did not choose?"

The question caught me off guard, much like the question posed to me in Laredo. Then, I realized I knew the answer. I knew why the coat hanger had been handed to me.

Growing up as the middle child in my family, I was a vital participant in a thing I did not govern, in the company of people I did not choose. It's family. It's society. And often, it's chaos. You participate by letting go of the small stuff, not expecting order and perfection, and facing the unexpected with confidence, optimism, and preparedness. My family experience taught me to face a serendipitous world with confidence.

What Makes This Essay Tick?

It's very helpful to take writing apart in order to see just how it accomplishes its objectives. Stephen's essay is very effective. Let's find out why!

An Opening Line That Draws You In

In just eight words, we get: scene-setting (he is standing next to a car about to break in), the idea of crossing a boundary (he is maybe about to do an illegal thing for the first time), and a cliffhanger (we are thinking: is he going to get caught? Is he headed for a life of crime? Is he about to be scared straight?).

Great, Detailed Opening Story

More out of amusement than optimism, I gave it a try. I slid the hanger into the window's seal like I'd seen on crime shows, and spent a few minutes jiggling the apparatus around the inside of the frame.

It's the details that really make this small experience come alive. Notice how whenever he can, Stephen uses a more specific, descriptive word in place of a more generic one. The volunteers aren't going to get food or dinner; they're going for "Texas BBQ." The coat hanger comes from "a dumpster." Stephen doesn't just move the coat hanger—he "jiggles" it.

Details also help us visualize the emotions of the people in the scene. The person who hands Stephen the coat hanger isn't just uncomfortable or nervous; he "takes a few steps back"—a description of movement that conveys feelings. Finally, the detail of actual speech makes the scene pop. Instead of writing that the other guy asked him to unlock the van, Stephen has the guy actually say his own words in a way that sounds like a teenager talking.

Turning a Specific Incident Into a Deeper Insight

Suddenly, two things simultaneously clicked. One was the lock on the door. (I actually succeeded in springing it.) The other was the realization that I'd been in this type of situation before. In fact, I'd been born into this type of situation.

Stephen makes the locked car experience a meaningful illustration of how he has learned to be resourceful and ready for anything, and he also makes this turn from the specific to the broad through an elegant play on the two meanings of the word "click."

Using Concrete Examples When Making Abstract Claims

My upbringing has numbed me to unpredictability and chaos. With a family of seven, my home was loud, messy, and spottily supervised. My siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing—all meant my house was functioning normally.

"Unpredictability and chaos" are very abstract, not easily visualized concepts. They could also mean any number of things—violence, abandonment, poverty, mental instability. By instantly following up with highly finite and unambiguous illustrations like "family of seven" and "siblings arguing, the dog barking, the phone ringing," Stephen grounds the abstraction in something that is easy to picture: a large, noisy family.

Using Small Bits of Humor and Casual Word Choice

My Dad, a retired Navy pilot, was away half the time. When he was home, he had a parenting style something like a drill sergeant. At the age of nine, I learned how to clear burning oil from the surface of water. My Dad considered this a critical life skill—you know, in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed.

Obviously, knowing how to clean burning oil is not high on the list of things every 9-year-old needs to know. To emphasize this, Stephen uses sarcasm by bringing up a situation that is clearly over-the-top: "in case my aircraft carrier should ever get torpedoed."

The humor also feels relaxed. Part of this is because he introduces it with the colloquial phrase "you know," so it sounds like he is talking to us in person. This approach also diffuses the potential discomfort of the reader with his father's strictness—since he is making jokes about it, clearly he is OK. Notice, though, that this doesn't occur very much in the essay. This helps keep the tone meaningful and serious rather than flippant.

An Ending That Stretches the Insight Into the Future

But one day this fall, Dr. Hicks, our Head of School, asked me a question that he hoped all seniors would reflect on throughout the year: "How can I participate in a thing I do not govern, in the company of people I did not choose?"

The ending of the essay reveals that Stephen's life has been one long preparation for the future. He has emerged from chaos and his dad's approach to parenting as a person who can thrive in a world that he can't control.

This connection of past experience to current maturity and self-knowledge is a key element in all successful personal essays. Colleges are very much looking for mature, self-aware applicants. These are the qualities of successful college students, who will be able to navigate the independence college classes require and the responsibility and quasi-adulthood of college life.

What Could This Essay Do Even Better?

Even the best essays aren't perfect, and even the world's greatest writers will tell you that writing is never "finished"—just "due." So what would we tweak in this essay if we could?

Replace some of the clichéd language. Stephen uses handy phrases like "twists and turns" and "don't sweat the small stuff" as a kind of shorthand for explaining his relationship to chaos and unpredictability. But using too many of these ready-made expressions runs the risk of clouding out your own voice and replacing it with something expected and boring.

Use another example from recent life. Stephen's first example (breaking into the van in Laredo) is a great illustration of being resourceful in an unexpected situation. But his essay also emphasizes that he "learned to adapt" by being "different things to different people." It would be great to see how this plays out outside his family, either in the situation in Laredo or another context.

Example 2: By Renner Kwittken, Tufts Class of '23 (Common App Essay, 645 words long)

My first dream job was to be a pickle truck driver. I saw it in my favorite book, Richard Scarry's "Cars and Trucks and Things That Go," and for some reason, I was absolutely obsessed with the idea of driving a giant pickle. Much to the discontent of my younger sister, I insisted that my parents read us that book as many nights as possible so we could find goldbug, a small little golden bug, on every page. I would imagine the wonderful life I would have: being a pig driving a giant pickle truck across the country, chasing and finding goldbug. I then moved on to wanting to be a Lego Master. Then an architect. Then a surgeon.

Then I discovered a real goldbug: gold nanoparticles that can reprogram macrophages to assist in killing tumors, produce clear images of them without sacrificing the subject, and heat them to obliteration.

Suddenly the destination of my pickle was clear.

I quickly became enveloped by the world of nanomedicine; I scoured articles about liposomes, polymeric micelles, dendrimers, targeting ligands, and self-assembling nanoparticles, all conquering cancer in some exotic way. Completely absorbed, I set out to find a mentor to dive even deeper into these topics. After several rejections, I was immensely grateful to receive an invitation to work alongside Dr. Sangeeta Ray at Johns Hopkins.

In the lab, Dr. Ray encouraged a great amount of autonomy to design and implement my own procedures. I chose to attack a problem that affects the entire field of nanomedicine: nanoparticles consistently fail to translate from animal studies into clinical trials. Jumping off recent literature, I set out to see if a pre-dose of a common chemotherapeutic could enhance nanoparticle delivery in aggressive prostate cancer, creating three novel constructs based on three different linear polymers, each using fluorescent dye (although no gold, sorry goldbug!). Though using radioactive isotopes like Gallium and Yttrium would have been incredible, as a 17-year-old, I unfortunately wasn't allowed in the same room as these radioactive materials (even though I took a Geiger counter to a pair of shoes and found them to be slightly dangerous).

I hadn't expected my hypothesis to work, as the research project would have ideally been led across two full years. Yet while there are still many optimizations and revisions to be done, I was thrilled to find -- with completely new nanoparticles that may one day mean future trials will use particles with the initials "RK-1" -- thatcyclophosphamide did indeed increase nanoparticle delivery to the tumor in a statistically significant way.

A secondary, unexpected research project was living alone in Baltimore, a new city to me, surrounded by people much older than I. Even with moving frequently between hotels, AirBnB's, and students' apartments, I strangely reveled in the freedom I had to enjoy my surroundings and form new friendships with graduate school students from the lab. We explored The Inner Harbor at night, attended a concert together one weekend, and even got to watch the Orioles lose (to nobody's surprise). Ironically, it's through these new friendships I discovered something unexpected: what I truly love is sharing research. Whether in a presentation or in a casual conversation, making others interested in science is perhaps more exciting to me than the research itself. This solidified a new pursuit to angle my love for writing towards illuminating science in ways people can understand, adding value to a society that can certainly benefit from more scientific literacy.

It seems fitting that my goals are still transforming: in Scarry's book, there is not just one goldbug, there is one on every page. With each new experience, I'm learning that it isn't the goldbug itself, but rather the act of searching for the goldbugs that will encourage, shape, and refine my ever-evolving passions. Regardless of the goldbug I seek -- I know my pickle truck has just begun its journey.

Renner takes a somewhat different approach than Stephen, but their essay is just as detailed and engaging. Let's go through some of the strengths of this essay.

One Clear Governing Metaphor

This essay is ultimately about two things: Renner’s dreams and future career goals, and Renner’s philosophy on goal-setting and achieving one’s dreams.

But instead of listing off all the amazing things they’ve done to pursue their dream of working in nanomedicine, Renner tells a powerful, unique story instead. To set up the narrative, Renner opens the essay by connecting their experiences with goal-setting and dream-chasing all the way back to a memorable childhood experience:

This lighthearted–but relevant!--story about the moment when Renner first developed a passion for a specific career (“finding the goldbug”) provides an anchor point for the rest of the essay. As Renner pivots to describing their current dreams and goals–working in nanomedicine–the metaphor of “finding the goldbug” is reflected in Renner’s experiments, rejections, and new discoveries.

Though Renner tells multiple stories about their quest to “find the goldbug,” or, in other words, pursue their passion, each story is connected by a unifying theme; namely, that as we search and grow over time, our goals will transform…and that’s okay! By the end of the essay, Renner uses the metaphor of “finding the goldbug” to reiterate the relevance of the opening story: