This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

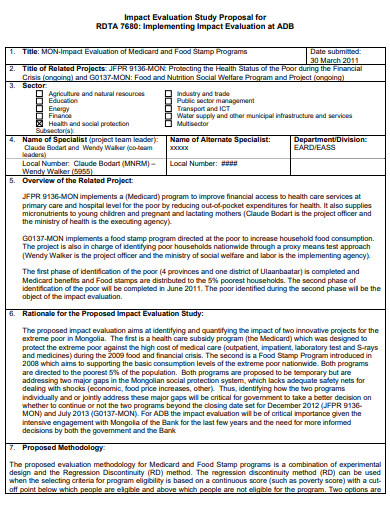

Impact evaluation

An impact evaluation provides information about the observed changes or 'impacts' produced by an intervention.

These observed changes can be positive and negative, intended and unintended, direct and indirect. An impact evaluation must establish the cause of the observed changes. Identifying the cause is known as 'causal attribution' or 'causal inference'.

If an impact evaluation fails to systematically undertake causal attribution, there is a greater risk that the evaluation will produce incorrect findings and lead to incorrect decisions. For example, deciding to scale up when the programme is actually ineffective or effective only in certain limited situations or deciding to exit when a programme could be made to work if limiting factors were addressed.

1. What is impact evaluation?

An impact evaluation provides information about the impacts produced by an intervention.

The intervention might be a small project, a large programme, a collection of activities, or a policy.

Many development agencies use the definition of impacts provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee :

"Positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended." (OECD-DAC 2010)

This definition implies that impact evaluation:

- goes beyond describing or measuring impacts that have occurred to seeking to understand the role of the intervention in producing these (causal attribution);

- can encompass a broad range of methods for causal attribution; and,

- includes examining unintended impacts.

2. Why do impact evaluation?

An impact evaluation can be undertaken to improve or reorient an intervention (i.e., for formative purposes) or to inform decisions about whether to continue, discontinue, replicate or scale up an intervention (i.e., for summative purposes).

While many formative evaluations focus on processes, impact evaluations can also be used formatively if an intervention is ongoing. For example, the findings of an impact evaluation can be used to improve implementation of a programme for the next intake of participants by identifying critical elements to monitor and tightly manage.

Most often, impact evaluation is used for summative purposes. Ideally, a summative impact evaluation does not only produce findings about ‘what works’ but also provides information about what is needed to make the intervention work for different groups in different settings.

3. When to do impact evaluation?

An impact evaluation should only be undertaken when its intended use can be clearly identified and when it is likely to be able to produce useful findings, taking into account the availability of resources and the timing of decisions about the intervention under investigation. An evaluability assessment might need to be done first to assess these aspects.

Prioritizing interventions for impact evaluation should consider: the relevance of the evaluation to the organisational or development strategy; its potential usefulness; the commitment from senior managers or policy makers to using its findings; and/or its potential use for advocacy or accountability requirements.

It is also important to consider the timing of an impact evaluation. When conducted belatedly, the findings come too late to inform decisions. When done too early, it will provide an inaccurate picture of the impacts (i.e., impacts will be understated when they had insufficient time to develop or overstated when they decline over time).

What are the intended uses and timings?

Impact evaluation might be appropriate when there is scope to use the findings to inform decisions about future interventions

It might not be appropriate when there are no clear intended uses or intended users. For example, if decisions have already been made on the basis of existing credible evidence, or if decisions need to be made before it is possible to undertake a credible impact evaluation

What is the current focus?

Impact evaluation might be appropriate when there is a need to understand the impacts that have been produced.

It might not be appropriate when the priority at this stage is to understand and improve the quality of the implementation.

Are there adequate resources to do the job?

Impact evaluation might be appropriate when there are adequate resources to undertake a sufficiently comprehensive and rigorous impact evaluation, including the availability of existing, good quality data and additional time and money to collect more.

It might not be appropriate when existing data are inadequate and there are insufficient resources to fill gaps with new, good quality data collection.

Is it relevant to current strategies and priorities?

Impact evaluation might be appropriate when it is clearly linked to the strategies and priorities of an organisation, partnership and/or government.

It might not be appropriate when it is peripheral to the strategies and priorities of an organisation, partnership and/or government.

4. Who to engage in the evaluation process?

Regardless of the type of evaluation, it is important to think through who should be involved, why and how they will be involved in each step of the evaluation process to develop an appropriate and context-specific participatory approach. Participation can occur at any stage of the impact evaluation process: in deciding to do an evaluation, in its design, in data collection, in analysis, in reporting and, also, in managing it.

Being clear about the purpose of participatory approaches in an impact evaluation is an essential first step towards managing expectations and guiding implementation. Is the purpose to ensure that the voices of those whose lives should have been improved by the programme or policy are central to the findings? Is it to ensure a relevant evaluation focus? Is it to hear people’s own versions of change rather than obtain an external evaluator’s set of indicators? Is it to build ownership of a donor-funded programme? These, and other considerations, would lead to different forms of participation by different combinations of stakeholders in the impact evaluation.

The underlying rationale for choosing a participatory approach to impact evaluation can be either pragmatic or ethical, or a combination of the two. Pragmatic because better evaluations are achieved (i.e. better data, better understanding of the data, more appropriate recommendations, better uptake of findings); ethical because it is the right thing to do (i.e. people have a right to be involved in informing decisions that will directly or indirectly affect them, as stipulated by the UN human rights-based approach to programming).

Participatory approaches can be used in any impact evaluation design. In other words, they are not exclusive to specific evaluation methods or restricted to quantitative or qualitative data collection and analysis.

The starting point for any impact evaluation intending to use participatory approaches lies in clarifying what value this will add to the evaluation itself as well as to the people who would be closely involved (but also including potential risks of their participation). Three questions need to be answered in each situation:

(1) What purpose will stakeholder participation serve in this impact evaluation?;

(2) Whose participation matters, when and why?; and,

(3) When is participation feasible?

Only after addressing these, can the issue of how to make impact evaluation more participatory be addressed.

Read more on who to engage in the evaluation process:

- The BetterEvaluation Rainbow Framework provides a good overview of the key stages in the evaluation process during which the question ‘Who is best involved?’ can be asked. These stages involve: managing the impact evaluation, defining and framing the evaluation focus, collecting data on impacts, explaining impacts, synthesising findings, and reporting on and supporting the use of the evaluation findings.

- Understand and engage stakeholders

- Participatory Evaluation

- UNICEF Brief 5. Participatory Approaches

5. How to plan and manage an impact evaluation?

Like any other evaluation, an impact evaluation should be planned formally and managed as a discrete project, with decision-making processes and management arrangements clearly described from the beginning of the process.

Planning and managing include:

- Describing what needs to be evaluated and developing the evaluation brief

- Identifying and mobilizing resources

- Deciding who will conduct the evaluation and engaging the evaluator(s)

- Deciding and managing the process for developing the evaluation methodology

- Managing development of the evaluation work plan

- Managing implementation of the work plan including development of reports

- Disseminating the report(s) and supporting use

Determining causal attribution is a requirement for calling an evaluation an impact evaluation. The design options (whether experimental, quasi-experimental, or non-experimental) all need significant investment in preparation and early data collection, and cannot be done if an impact evaluation is limited to a short exercise conducted towards the end of intervention implementation. Hence, it is particularly important that impact evaluation is addressed as part of an integrated monitoring, evaluation and research plan and system that generates and makes available a range of evidence to inform decisions. This will also ensure that data from other M&E activities such as performance monitoring and process evaluation can be used, as needed.

Read more on how to plan and manage an impact evaluation:

- Plan and manage an evaluation

- Establish decision making processes

- Determine and secure resources

- Document management processes and agreements

- UNICEF Brief 1. Overview of impact evaluation

6. What methods can be used to do impact evaluation?

Framing the boundaries of the impact evaluation.

The evaluation purpose refers to the rationale for conducting an impact evaluation. Evaluations that are being undertaken to support learning should be clear about who is intended to learn from it, how they will be engaged in the evaluation process to ensure it is seen as relevant and credible, and whether there are specific decision points around where this learning is expected to be applied. Evaluations that are being undertaken to support accountability should be clear about who is being held accountable, to whom and for what.

Evaluation relies on a combination of facts and values (i.e., principles, attributes or qualities held to be intrinsically good, desirable, important and of general worth such as ‘being fair to all’) to judge the merit of an intervention (Stufflebeam 2001). Evaluative criteria specify the values that will be used in an evaluation and, as such, help to set boundaries.

Many impact evaluations use the standard OECD-DAC criteria (OECD-DAC accessed 2015):

- Relevance : The extent to which the objectives of an intervention are consistent with recipients’ requirements, country needs, global priorities and partners’ policies.

- Effectiveness : The extent to which the intervention’s objectives were achieved, or are expected to be achieved, taking into account their relative importance.

- Efficiency : A measure of how economically resources/inputs (funds, expertise, time, equipment, etc.) are converted into results.

- Impact : Positive and negative primary and secondary long-term effects produced by the intervention, whether directly or indirectly, intended or unintended.

- Sustainability : The continuation of benefits from the intervention after major development assistance has ceased. Interventions must be both environmentally and financially sustainable. Where the emphasis is not on external assistance, sustainability can be defined as the ability of key stakeholders to sustain intervention benefits – after the cessation of donor funding – with efforts that use locally available resources.

The OECD-DAC criteria reflect the core principles for evaluating development assistance (OECD-DAC 1991) and have been adopted by most development agencies as standards of good practice in evaluation. Other, commonly used evaluative criteria are about equity, gender equality, and human rights. And, some are used for particular types of development interventions such humanitarian assistance such as: coverage, coordination, protection, coherence. In other words, not all of these evaluative criteria are used in every evaluation, depending on the type of intervention and/or the type of evaluation (e.g., the criterion of impact is irrelevant to a process evaluation).

Evaluative criteria should be thought of as ‘concepts’ that must be addressed in the evaluation. They are insufficiently defined to be applied systematically and in a transparent manner to make evaluative judgements about the intervention. Under each of the ‘generic’ criteria, more specific criteria such as benchmarks and/or standards* – appropriate to the type and context of the intervention – should be defined and agreed with key stakeholders.

The evaluative criteria should be clearly reflected in the evaluation questions the evaluation is intended to address.

*A benchmark or index is a set of related indicators that provides for meaningful, accurate and systematic comparisons regarding performance; a standard or rubric is a set of related benchmarks/indices or indicators that provides socially meaningful information regarding performance.

Defining the key evaluation questions (KEQs) the impact evaluation should address

Impact evaluations should be focused around answering a small number of high-level key evaluation questions (KEQs) that will be answered through a combination of evidence. These questions should be clearly linked to the evaluative criteria. For example:

- KEQ1: What was the quality of the intervention design/content? [ assessing relevance, equity, gender equality, human rights ]

- KEQ2: How well was the intervention implemented and adapted as needed? [ assessing effectiveness, efficiency ]

- KEQ3: Did the intervention produce the intended results in the short, medium and long term? If so, for whom, to what extent and in what circumstances? [ assessing effectiveness, impact, equity, gender equality ]

- KEQ4: What unintended results – positive and negative – did the intervention produce? How did these occur? [ assessing effectiveness, impact, equity, gender equality, human rights ]

- KEQ5: What were the barriers and enablers that made the difference between successful and disappointing intervention implementation and results? [ assessing relevance, equity, gender equality, human rights ]

- KEQ6: How valuable were the results to service providers, clients, the community and/or organizations involved? [ assessing relevance, equity, gender equality, human rights ]

- KEQ7: To what extent did the intervention represent the best possible use of available resources to achieve results of the greatest possible value to participants and the community? [ assessing efficiency ]

- KEQ8: Are any positive results likely to be sustained? In what circumstances? [ assessing sustainability, equity, gender equality, human rights ]

A range of more detailed (mid-level and lower-level) evaluation questions should then be articulated to address each evaluative criterion in detail. All evaluation questions should be linked explicitly to the evaluative criteria to ensure that the criteria are covered in full.

The KEQs also need to reflect the intended uses of the impact evaluation. For example, if an evaluation is intended to inform the scaling up of a pilot programme, then it is not enough to ask ‘Did it work?’ or ‘What were the impacts?’. A good understanding is needed of how these impacts were achieved in terms of activities and supportive contextual factors to replicate the achievements of a successful pilot. Equity concerns require that impact evaluations go beyond simple average impact to identify for whom and in what ways the programmes have been successful.

Within the KEQs, it is also useful to identify the different types of questions involved – descriptive, causal and evaluative.

- Descriptive questions ask about how things are and what has happened, including describing the initial situation and how it has changed, the activities of the intervention and other related programmes or policies, the context in terms of participant characteristics, and the implementation environment.

- Causal questions ask whether or not, and to what extent, observed changes are due to the intervention being evaluated rather than to other factors, including other programmes and/or policies.

- Evaluative questions ask about the overall conclusion as to whether a programme or policy can be considered a success, an improvement or the best option.

Read more on defining the key evaluation questions (KEQs) the impact evaluation should address:

- Specify key evaluation questions

- UNICEF Brief 3. Evaluative Criteria

Defining impacts

Impacts are usually understood to occur later than, and as a result of, intermediate outcomes. For example, achieving the intermediate outcomes of improved access to land and increased levels of participation in community decision-making might occur before, and contribute to, the intended final impact of improved health and well-being for women. The distinction between outcomes and impacts can be relative, and depends on the stated objectives of an intervention. It should also be noted that some impacts may be emergent, and thus, cannot be predicted.

Read more on defining impacts:

- Use measures, indicators or metrics

- UNICEF Brief 11. Developing and Selecting Measures of Child Well-Being

Defining success to make evaluative judgements

Evaluation, by definition, answers evaluative questions, that is, questions about quality and value. This is what makes evaluation so much more useful and relevant than the mere measurement of indicators or summaries of observations and stories.

In any impact evaluation, it is important to define first what is meant by ‘success’ (quality, value). One way of doing so is to use a specific rubric that defines different levels of performance (or standards) for each evaluative criterion, deciding what evidence will be gathered and how it will be synthesized to reach defensible conclusions about the worth of the intervention.

At the very least, it should be clear what trade-offs would be appropriate in balancing multiple impacts or distributional effects. Since development interventions often have multiple impacts, which are distributed unevenly, this is an essential element of an impact evaluation. For example, should an economic development programme be considered a success if it produces increases in household income but also produces hazardous environmental impacts? Should it be considered a success if the average household income increases but the income of the poorest households is reduced?

To answer evaluative questions, what is meant by ‘quality’ and ‘value’ must first be defined and then relevant evidence gathered. Quality refers to how good something is; value refers to how good it is in terms of the specific situation, in particular taking into account the resources used to produce it and the needs it was supposed to address. Evaluative reasoning is required to synthesize these elements to formulate defensible (i.e., well-reasoned and well-evidenced) answers to the evaluative questions.

Evaluative reasoning is a requirement of all evaluations, irrespective of the methods or evaluation approach used.

An evaluation should have a limited set of high-level questions which are about performance overall. Each of these KEQs should be further unpacked by asking more detailed questions about performance on specific dimensions of merit and sometimes even lower-level questions. Evaluative reasoning is the process of synthesizing the answers to lower- and mid-level questions into defensible judgements that directly answer the high-level questions.

Read more on defining success to make evaluative judgements:

- Determine what success looks like

- Evaluation rubrics: How to ensure transparent and clear assessment that respects diverse lines of evidence

- UNICEF Brief 4. Evaluative Reasoning

Using a theory of change

Evaluations produce stronger and more useful findings if they not only investigate the links between activities and impacts but also investigate links along the causal chain between activities, outputs, intermediate outcomes and impacts. A ‘theory of change’ that explains how activities are understood to produce a series of results that contribute to achieving the ultimate intended impacts, is helpful in guiding causal attribution in an impact evaluation.

A theory of change should be used in some form in every impact evaluation. It can be used with any research design that aims to infer causality, it can use a range of qualitative and quantitative data, and provide support for triangulating the data arising from a mixed methods impact evaluation.

When planning an impact evaluation and developing the terms of reference, any existing theory of change for the programme or policy should be reviewed for appropriateness, comprehensiveness and accuracy, and revised as necessary. It should continue to be revised over the course of the evaluation should either the intervention itself or the understanding of how it works – or is intended to work – change.

Some interventions cannot be fully planned in advance, however – for example, programmes in settings where implementation has to respond to emerging barriers and opportunities such as to support the development of legislation in a volatile political environment. In such cases, different strategies will be needed to develop and use a theory of change for impact evaluation (Funnell and Rogers 2012). For some interventions, it may be possible to document the emerging theory of change as different strategies are trialled and adapted or replaced. In other cases, there may be a high-level theory of how change will come about (e.g., through the provision of incentives) and also an emerging theory about what has to be done in a particular setting to bring this about. Elsewhere, its fundamental basis may revolve around adaptive learning, in which case the theory of change should focus on articulating how the various actors gather and use information together to make ongoing improvements and adaptations.

A theory of change can support an impact evaluation in several ways. It can identify:

- specific evaluation questions, especially in relation to those elements of the theory of change for which there is no substantive evidence yet

- relevant variables that should be included in data collection

- intermediate outcomes that can be used as markers of success in situations where the impacts of interest will not occur during the time frame of the evaluation

- aspects of implementation that should be examined

- potentially relevant contextual factors that should be addressed in data collection and in analysis, to look for patterns.

The evaluation may confirm the theory of change or it may suggest refinements based on the analysis of evidence. An impact evaluation can check for success along the causal chain and, if necessary, examine alternative causal paths. For example, failure to achieve intermediate results might indicate implementation failure; failure to achieve the final intended impacts might be due to theory failure rather than implementation failure. This has important implications for the recommendations that come out of an evaluation. In cases of implementation failure, it is reasonable to recommend actions to improve the quality of implementation; in cases of theory failure, it is necessary to rethink the whole strategy to achieve impact.

Read more on using a theory of change:

- Develop programme theory/ theory of change

- UNICEF Brief 2. Theory of Change

Deciding the evaluation methodology

The evaluation methodology sets out how the key evaluation questions (KEQs) will be answered. It specifies designs for causal attribution, including whether and how comparison groups will be constructed, and methods for data collection and analysis.

Strategies and designs for determining causal attribution

Causal attribution is defined by OECD-DAC as:

“Ascription of a causal link between observed (or expected to be observed) changes and a specific intervention.” (OECD_DAC 2010)

This definition does not require that changes are produced solely or wholly by the programme or policy under investigation (UNEG 2013). In other words, it takes into consideration that other causes may also have been involved, for example, other programmes/policies in the area of interest or certain contextual factors (often referred to as ‘external factors’).

There are three broad strategies for causal attribution in impact evaluations:

- estimating the counterfactual (i.e., what would have happened in the absence of the intervention, compared to the observed situation)

- checking the consistency of evidence for the causal relationships made explicit in the theory of change

- ruling out alternative explanations, through a logical, evidence-based process.

Using a combination of these strategies can usually help to increase the strength of the conclusions that are drawn.

There are three design options that address causal attribution:

- Experimental designs – which construct a control group through random assignment.

- Quasi-experimental designs – which construct a comparison group through matching, regression discontinuity, propensity scores or another means.

- Non-experimental designs – which look systematically at whether the evidence is consistent with what would be expected if the intervention was producing the impacts, and also whether other factors could provide an alternative explanation.

Some individuals and organisations use a narrower definition of impact evaluation, and only include evaluations containing a counterfactual of some kind. These different definitions are important when deciding what methods or research designs will be considered credible by the intended user of the evaluation or by partners or funders.

Read more on strategies and designs for determining causal attribution:

- Understand causes

- Compare results to the counterfactual

- Randomised controlled trial

- Better use of case studies in evaluation

- UNICEF Brief 6. Overview: Strategies for Causal Attribution

- UNICEF Brief 7. Randomized Controlled Trials

- UNICEF Brief 8. Quasi-experimental Designs and Methods

- UNICEF Brief 13. Modelling

- UNICEF Brief 9. Comparative Case Studies

Data collection, management and analysis approach

Well-chosen and well-implemented methods for data collection and analysis are essential for all types of evaluations. Impact evaluations need to go beyond assessing the size of the effects (i.e., the average impact) to identify for whom and in what ways a programme or policy has been successful. What constitutes ‘success’ and how the data will be analysed and synthesized to answer the specific key evaluation questions (KEQs) must be considered upfront as data collection should be geared towards the mix of evidence needed to make appropriate judgements about the programme or policy. In other words, the analytical framework – the methodology for analysing the ‘meaning’ of the data by looking for patterns in a systematic and transparent manner – should be specified during the evaluation planning stage. The framework includes how data analysis will address assumptions made in the programme theory of change about how the programme was thought to produce the intended results. In a true mixed methods evaluation, this includes using appropriate numerical and textual analysis methods and triangulating multiple data sources and perspectives in order to maximize the credibility of the evaluation findings.

Start the data collection planning by reviewing to what extent existing data can be used. After reviewing currently available information, it is helpful to create an evaluation matrix (see below) showing which data collection and analysis methods will be used to answer each KEQ and then identify and prioritize data gaps that need to be addressed by collecting new data. This will help to confirm that the planned data collection (and collation of existing data) will cover all of the KEQs, determine if there is sufficient triangulation between different data sources and help with the design of data collection tools (such as questionnaires, interview questions, data extraction tools for document review and observation tools) to ensure that they gather the necessary information.

There are many different methods for collecting data. Although many impact evaluations use a variety of methods, what distinguishes a ’mixed methods evaluation’ is the systematic integration of quantitative and qualitative methodologies and methods at all stages of an evaluation (Bamberger 2012). A key reason for mixing methods is that it helps to overcome the weaknesses inherent in each method when used alone. It also increases the credibility of evaluation findings when information from different data sources converges (i.e., they are consistent about the direction of the findings) and can deepen the understanding of the programme/policy, its effects and context (Bamberger 2012).

Good data management includes developing effective processes for: consistently collecting and recording data, storing data securely, cleaning data, transferring data (e.g., between different types of software used for analysis), effectively presenting data and making data accessible for verification and use by others.

The particular analytic framework and the choice of specific data analysis methods will depend on the purpose of the impact evaluation and the type of KEQs that are intrinsically linked to this.

For answering descriptive KEQs, a range of analysis options is available, which can largely be grouped into two key categories: options for quantitative data (numbers) and options for qualitative data (e.g., text).

For answering causal KEQs, there are essentially three broad approaches to causal attribution analysis: (1) counterfactual approaches; (2) consistency of evidence with causal relationship; and (3) ruling out alternatives (see above). Ideally, a combination of these approaches is used to establish causality.

For answering evaluative KEQs, specific evaluative rubrics linked to the evaluative criteria employed (such as the OECD-DAC criteria) should be applied in order to synthesize the evidence and make judgements about the worth of the intervention (see above).

Read more on data collection, management and analysis approach

- Collect and/or Retrieve Data

- Manage Data

- Analyse Data

- Combine Qualitative and Quantitative Data

- UNICEF Brief 10. Overview: Data Collection and Analysis Methods in Impact Evaluation

- UNICEF Brief 12. Interviewing

7. How can the findings be reported and their use supported?

The evaluation report should be structured in a manner that reflects the purpose and KEQs of the evaluation.

In the first instance, evidence to answer the detailed questions linked to the OECD-DAC criteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability, and considerations of equity, gender equality and human rights should be presented succinctly but with sufficient detail to substantiate the conclusions and recommendations.

The specific evaluative rubrics should be used to ‘interpret’ the evidence and determine which considerations are critically important or urgent. Evidence on multiple dimensions should subsequently be synthesized to generate answers to the high-level evaluative questions.

The structure of an evaluation report can do a great deal to encourage the succinct reporting of direct answers to evaluative questions, backed up by enough detail about the evaluative reasoning and methodology to allow the reader to follow the logic and clearly see the evidence base.

The following recommendations will help to set clear expectations for evaluation reports that are strong on evaluative reasoning:

The executive summary must contain direct and explicitly evaluative answers to the KEQs used to guide the whole evaluation.

Explicitly evaluative language must be used when presenting findings (rather than value-neutral language that merely describes findings). Examples should be provided.

Use of clear and simple data visualization to present easy-to-understand ‘snapshots’ of how the intervention has performed on the various dimensions of merit.

Structuring of the findings section using KEQs as subheadings (rather than types and sources of evidence, as is frequently done).

There must be clarity and transparency about the evaluative reasoning used, with the explanations clearly understandable to both non-evaluators and readers without deep content expertise in the subject matter. These explanations should be broad and brief in the main body of the report, with more detail available in annexes.

If evaluative rubrics are relatively small in size, these should be included in the main body of the report. If they are large, a brief summary of at least one or two should be included in the main body of the report, with all rubrics included in full in an annex.

Read more on how can the findings be reported and their use supported?

- Develop reporting media

- Visualise data

Page contributors

The content for this page was compiled by: Greet Peersman

The content is based on ‘UNICEF Methodological Briefs for Impact Evaluation’, a collaborative project between the UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, BetterEvaluation, RMIT University and the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie).The briefs were written by (in alphabetical order): E. Jane Davidson, Thomas de Hoop, Delwyn Goodrick, Irene Guijt, Bronwen McDonald, Greet Peersman, Patricia Rogers, Shagun Sabarwal, Howard White.

Overviews/introductions to impact evaluation

This paper, written by Patricia Rogers for UNICEF, outlines the basic ideas and principles of impact evaluation. It includes a discussion of the different elements and options for the different stages of conducting an impact evaluation.

Discussion Papers

This paper provides a summary of debates about measuring and attributing impacts.

This special edition of the IDS Bulletin presents contributions from the event 'Impact Innovation and Learning: Towards a Research and Practice Agenda for the Future', organised by IDS in March 2013.

This paper, written by Sandra Nutley, Alison Powell and Huw Davies for the Alliance for Useful Evidence, discusses the risks of using a hierarchy of evidence and suggests an alternative in which more complex matrix approaches for identifying evidence qu

- InterAction Impact Evaluation Guidance Notes and Webinar Series

Rogers P (2012). Introduction to Impact Evaluation. Impact Evaluation Notes No. 1 . Washington DC: InterAction. – This guidance note outlines the basic principles and ideas of Impact Evaluation including when, why, how and by whom it should be done.

Perrin B (2012). Linking Monitoring and Evaluation to Impact Evaluation. Impact Evaluation Notes No.2. Washington DC: InterAction. – This guidance note outlines how monitoring and evaluation (M&E) activities can support meaningful and valid impact evaluation.

Bamberger M (2012). Introduction to Mixed Methods in Impact Evaluation. Guidance Note No. 3. Washington DC: InterAction. – This guidance note provides an outline of a mixed methods impact evaluation with particular reference to the difference between this approach and qualitative and quantitative impact evaluation designs.

Bonbright D (2012). Use of Impact Evaluation Results. Guidance Note No. 4. Washington DC: InterAction. – This guidance note highlights three themes that are crucial for effective utilization of evaluation results.

Realist impact evaluation is an approach to impact evaluation that emphasises the importance of context for programme outcomes.

“Gender affects everyone, all of the time. Gender affects the way we see each other, the way we interact, the institutions we create, the ways in which those institutions operate, and who benefits or suffers as a result of this.” (Fletcher 2015: 19)

This document provides an overview of the utility of and specific guidance and a tool for implementing an evaluability assessment before an impact evaluation is undertaken.

Many development programme staff have had the experience of commissioning an impact evaluation towards the end of a project or programme only to find that the monitoring system did not provide adequate data about implementation, context, baselines or in

- Additional guidance documents can be found here

Over recent decades, governments everywhere have increased their scrutiny of public spending, and public universities have not escaped this scrutiny.

International development is fixated with impact. But how do we know we’re all talking about the same thing?

This blog post by Simon Hearn (ODI) was originally posted by Action to Research.

This week, EvalPartners will be launching EvalGender+, the global partnership for equity-focused and gender-responsive evaluations. The launch is part of the Global Evaluation Week in Kathmandu to celebrate the International Year of Evaluation.

Impact evaluation, like many areas of evaluation, is under-researched. Doing systematic research about evaluation takes considerable resources, and is often constrained by the availability of information about evaluation practice.

Nikola Balvin, Knowledge Management Specialist at the UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, presents new resources on impact evaluation and discusses how they can be used to support managers who commission impact evaluations.

Designating something a “best practice” is a marketing ploy, not a scientific conclusion. Calling something “best” is a political and ideological assertion dressed up in research-sounding terminology.

In development, government and philanthropy, there is increasing recognition of the potential value of impact evaluation.

Bamberger M (2012). Introduction to Mixed Methods in Impact Evaluation. Guidance Note No. 3. Washington DC: InterAction. See: https://www.interaction.org/blog/impact-evaluation-guidance-note-and-webinar-series/

Funnell S and Rogers P (2012). Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Logic Models and Theories of Change . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

OECD-DAC (1991). Principles for Evaluation of Development Assistance. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC). See: http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/50584880.pdf

OEDC-DAC (2010). Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management . Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee (OEDC-DAC). See: http://www.oecd.org/development/peer-reviews/2754804.pdf

OECD-DAC (accessed 2015). Evaluation of development programmes. DAC Criteria for Evaluating Development Assistance. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC). See: http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm

Stufflebeam D (2001). Evaluation values and criteria checklist. Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University Checklist Project. See: https://www.dmeforpeace.org/resource/evaluation-values-and-criteria-checklist/

UNEG (2013). Impact Evaluation in UN Agency Evaluation Systems: Guidance on Selection, Planning and Management . Guidance Document . New York: United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) . See: http://www.uneval.org/papersandpubs/documentdetail.jsp?doc_id=1434

Expand to view all resources related to 'Impact evaluation'

- Introduction to impact evaluation

- Linking monitoring and evaluation to impact evaluation

- Sinopsis de la evaluación de impacto

- Addressing gender in impact evaluation

- Assessing rural transformations: Piloting a qualitative impact protocol in Malawi and Ethiopia

- Attributing development impact: The qualitative impact protocol (QuIP) case book

- Bath social & developmental research ltd. (BSDR) website

- Broadening the range of designs and methods for impact evaluations

- Case study: QuIP & RCT to evaluate a cash transfer and gender training programme in Malawi

- Cases in outcome harvesting

- Causal link monitoring brief

- Clearing the fog: New tools for improving the credibility of impact claims

- Como elaborar modelo lógico:roteiro para formular programas e organizar avaliação

- Comparative case studies

- Comparing QuIP with thirty other approaches to impact evaluation

- Contribution analysis in policy work: Assessing advocacy’s influence

- Contribution analysis: A promising method for assessing advocacy's impact

- Designing impact evaluations: Different perspectives

- Designing quality impact evaluations under budget, time and data constraints

- Developing and selecting measures of child well-being

- Diseño de evaluaciones de impacto: Perspectivas diversas

- Does our theory match your theory? Theories of change and causal maps in Ghana

- Estudo de caso: a avaliação externa de um programa

- Evaluability assessment for impact evaluation

- Evaluations that make a difference

- Evaluative criteria

- Evaluative reasoning

- Finding and using causal hotspots: A practice in the making

- From narrative text to causal maps: QuIP analysis and visualisation

- Impact evaluation in practice

- Impact evaluation toolkit

- Impact evaluation: A guide for commissioners and managers

- Impact evaluation: How to institutionalize evaluation

- Impact evaluations and development

- Institutionalizing evaluation: A review of international experience

- Interviewing

- Introducción a la evaluación de impacto

- Introduction to mixed methods in impact evaluation

- Introduction to randomized control trials

- Introduction à l’évaluation d’impact

- Learning through and about contribution analysis for impact evaluation

- Méthodologie de l’évaluation d’impact : présentation de différentes approches

- O sistema de monitoramento e avaliação dos programas de promoção e proteção social do Brasil

- Overview of impact evaluation

- Overview: Data collection and analysis methods in impact evaluation

- Overview: Strategies for causal attribution

- Participatory approaches

- Participatory impact assessment: A design guide

- Process tracing and contribution analysis: A combined approach to generative causal inference for impact evaluation

- Prosaic or profound? The adoption of systems ideas by impact evaluation

- Présentation de l'évaluation d’impact

- Présentation des méthodes de collecte et d'analyse de données dans l'évaluation d'impact

- Présentation des stratégies d'attribution causale

- QuIP and the Yin/Yang of Quant and Qual: How to navigate QuIP visualisations

- QuIP used as part of an evaluation of the impact of the UK Government Tampon Tax Fund (TTF)

- QuIP: Understanding clients through in-depth interviews

- Qualitative impact assessment protocol (QuIP)

- Quantitative and qualitative methods in impact evaluation and measuring results

- Quasi-experimental design and methods

- Quasi-experimental methods for impact evaluations

- Randomised control trials for the impact evaluation of development initiatives: a statistician's point of view

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) video guide

- Realist impact evaluation: An introduction

- Sinopsis: estrategias de atribución causal

- Sinopsis: métodos de recolección y análisis de datos en la evaluación de impacto

- Systematic reviews

- The importance of a methodologically diverse approach to impact evaluation

- The theory of change

- Theory of change

- Tools and tips for implementing contribution analysis

- UNICEF Impact Evaluation series

- UNICEF webinar: Comparative case studies

- UNICEF webinar: Overview of data collection and analysis methods in Impact Evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Overview of impact evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Overview: strategies for causal inference

- UNICEF webinar: Participatory approaches in impact evaluation

- UNICEF webinar: Quasi-experimental design and methods

- UNICEF webinar: Randomized controlled trials

- UNICEF webinar: Theory of change

- Using evidence to inform policy

- What is impact evaluation?

- مقدمة لتقييم الأثر

- 关于影响评估的设计: 不同的视角

'Impact evaluation' is referenced in:

- 52 weeks of BetterEvaluation: Week 44: How can monitoring data support impact evaluations?

- Impact evaluation: challenges to address

Framework/Guide

- Rainbow Framework : Investigate possible alternative explanations

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

Designing an impact evaluation work plan: a step-by-step guide

May 4, 2021.

This article is the second part of our 2-part series on impact evaluation. In the first article, “ Impact evaluation: overview, benefits, types and planning tips,” we introduced impact evaluation and some helpful steps for planning and incorporating it into your M&E plan.

In this blog, we will walk you through the next steps in the process – from understanding the core elements of an impact evaluation work plan to designing your own impact evaluation to identify the real difference your interventions are making on the ground . Elements in the work plan include but are not limited to – the purpose, scope and objectives of the evaluation, key evaluation questions, designs and methodologies and more. Stay with us as we deep dive into each element of the impact evaluation work plan!

Key elements in an impact evaluation work plan

Developing an appropriate evaluation design and work plan is critically important in impact evaluation. Evaluation work plans are also called terms of reference (ToR) in some organisations. While the format of an evaluation design may vary on a case by case basis, it must always include some essential elements, including:

- Background and context

- The purpose, objectives and scope of the evaluation

- Theory of change (ToC)

- Key evaluation questions the evaluation aims to answer

- Proposed designs and methodologies

- Data collection methods

- Specific deliverables and timelines

1. Background and context

This section provides information on the background of the intervention to be evaluated. The description should be concise and kept under one page and focus only on the issues pertinent for the evaluation – the intended objectives of the intervention, the timeframe and the progress achieved at the moment of the evaluation, key stakeholders involved in the intervention, organisational, social, political and economic factors which may have an influence on the intervention’s implementation etc.

2. Defining impact evaluation purpose, objectives and scope

Consultation with the key stakeholders is vital to determine the purpose, objectives and scope of the evaluation and identify some of its other important parameters.

The evaluation purpose refers to the rationale for conducting an impact evaluation. Evaluations that are being undertaken to support learning should be clear about who is intended to learn from it, how they will be engaged in the evaluation process to ensure it is seen as relevant and credible, and whether there are specific decision points around where this learning is expected to be applied. Evaluations that are being undertaken to support accountability should be clear about who is being held accountable, to whom and for what.

The objective of impact evaluation reflects what the evaluation aims to find out. It can be to measure impact and to analyse the mechanisms producing the impact. It is best to have no more than 2-3 objectives, that way the team can explore few issues in depth rather than examine a broader set superficially.

The scope of the evaluation includes the time period, the geographical and thematic coverage of the evaluation, the target groups and the issues to be considered. The scope of the evaluation must be realistic given the time and resources available. Specifying the evaluation scope enables clear identification of the implementing organisation’s expectations and of the priorities that the evaluation team must focus on in order to avoid wasting its resources on areas of secondary interest. The central scope is usually specified in the work plan or the terms of reference (ToR) and the extended scope in the inception report.

3. Theory of change (ToC)

Theory of change (ToC) or project framework is a vital building block for any evaluation work and every evaluation should begin with one. A ToC may also be represented in the form of a logic model or a results framework. It illustrates project goals, objectives, outcomes and assumptions underlying the theory and explains how project activities are expected to produce a series of results that contribute to achieving the intended or observed project objectives and impacts.

A ToC also identifies which aspects of the interventions should be examined, what contextual factors should be addressed, what the likely intermediate outcomes will be and how the validity of the assumptions will be tested. Plus, a ToC explains what data should be gathered and how it will be synthesized to reach justifiable conclusions about the effectiveness of the intervention. Alternative causal paths and major external factors influencing outcomes may also be identified in a project theory.

A ToC also helps to identify gaps in logic or evidence that the evaluation should focus on, and provides the structure for a narrative about the value and impact of an intervention. All in all, a ToC helps the project team to determine the best impact evaluation methods for their intervention. ToCs should be reviewed and revised on a regular basis and kept up to date at all stages of the project lifecycle – be this at project design, implementation, delivery, or close.

More on the theory of change, logic model and results framework.

4. Key impact evaluation questions

Impact evaluations should be focused on key evaluation questions that reflect the intended use of the evaluation. Impact evaluation will generally answer three types of questions: descriptive, causal or evaluative. Each type of question can be answered through a combination of different research designs and data collection and analysis mechanisms.

- Descriptive questions ask about how things were and how they are now and what changes have taken place since the intervention.

- Causal questions ask what produced the changes and whether or not, and to what extent, observed changes are due to the intervention rather than other factors.

- Evaluative questions ask about the overall value of the intervention, taking into account intended and unintended impacts. It determines whether the intervention can be considered a success, an improvement or the best option.

Examples of key evaluation questions for impact evaluation based on the OECD-DAC evaluation criteria.

5. Impact evaluation design and methodologies

Measuring direct causes and effects can be quite difficult, therefore, the choice of methods and designs for impact evaluation of interventions is not straightforward, and comes with a unique set of challenges. There is no one right way to undertake an impact evaluation, discussing all the potential options and using a combination of different methods and designs that suit a particular situation must be considered.

Generally, the evaluation methodology is designed on the basis of how the key descriptive, causal and evaluative evaluation questions will be answered, how data will be collected and analysed, the nature of the intervention being evaluated, the available resources and constraints and the intended use of the evaluation.

The choice of the methods and designs also depend on causal attribution, including whether there is a need to form comparison groups and how it will be constructed. In some cases, quantifying the impacts of interventions requires estimating the counterfactual – meaning, estimating what would have happened to the beneficiaries in the absence of the intervention? But in most cases, mixed-method approaches are recommended as they build on qualitative and quantitative data and make use of several methodologies for analysis.

In all types of evaluations, it is important to dedicate sufficient time to develop a sound evaluation design before any data collection or analysis begins. The proposed design must be reviewed at the beginning of the evaluation and it must be updated on a regular basis – this helps to manage the quality of evaluation throughout the entire project cycle. Plus, engaging with a broad range of stakeholders and following established ethical standards and using the evaluation reference group to review evaluation design and draft reports all contribute to ensuring the quality of evaluation.

Descriptive Questions

In most cases, an effective combination of quantitative and qualitative data will provide a more comprehensive picture of what changes have taken place since the intervention. Data collection options include, but are not limited to interviews, questionnaires, structured or unstructured and participatory or non-participatory observations recorded through notes, photos or video; biophysical measurements or geographical information and existing documents and data, including existing data sets, official statistics, project records, social media data and more.

Causal Questions

Answering causal questions require a research design that addresses “attribution” and “contribution.” Attribution means the changes observed are entirely caused by the intervention and contribution means that the intervention partially caused or contributed to the changes. In practice, it is quite complex for an organisation to fully claim attribution to a change, this is because changes within the community are likely to be the result of a mix of different factors besides just the effects of the intervention, such as changes in economic and social environments, national policy etc.

The design for answering causal questions could be ‘experimental,’ ‘quasi-experimental’ or ‘non-experimental.’ Let’s take a look at each design separately:

Experimental: involves the construction of a control group through random assignment of participants. Experimental designs can produce highly credible impact estimates but are often expensive and for certain interventions, difficult to implement. Examples of experimental designs include:

- Randomized controlled trial (RCT) – In this type of experiment, two groups, a treatment group and a comparison group are created and participants for each group are picked randomly. The two groups are statistically identical, in terms of both observed and unobserved factors before the intervention but the group receiving treatment will gradually show changes as the project progresses. Outcome data for comparison and treatment groups and baseline data and background variables are helpful in determining the change.

Quasi experimental: unlike experimental design, quasi experimental design involves construction of a valid comparison group through matching, regression discontinuity, propensity scores or other statistical means to control and measure the differences between the individuals treated with the intervention being evaluated and those not treated. Examples of quasi-experimental designs include,

- Difference-in-differences: this measures improvement or change over time of an intervention’s participants relative to the improvement or change of non-participants.

- Propensity score matching: Individuals in the treatment group are matched with non-participants who have similar observable characteristics. The average difference in outcomes between matched individuals is the estimated impact. This method is based on the assumption that there is no unobserved difference in the treatment and comparison group.

- Matched comparisons: this design compares the differences between participants of an intervention being evaluated with the non participants after the intervention is completed.

- Regression discontinuity: in this design, individuals are ranked based on specific, measurable criteria. There is usually a cut-off point to determine who is eligible to participate. Impact is measured by comparing outcomes of participants and non-participants close to the cutoff line. Outcomes as well as data of ranking criteria, e.g. age, index, etc. and data on socioeconomic background variables are used.

Non-experimental: when experimental and quasi-experimental designs are not possible, we can conduct non-experimental designs for impact evaluation. This design takes a systematic look at whether the evidence is consistent with what would be expected if the intervention was producing the impacts, and also whether other factors could provide an alternative explanation.

- Hypothetical and logical counterfactuals : it is basically an estimate of what would have happened in the absence of an intervention. It involves consulting with key informants to identify either a hypothetical counterfactual, meaning what they think would have happened in the absence of an intervention or a logical counterfactual, meaning what would logically have happened in its absence.

- Qualitative comparative analysis: this design is particularly useful where there are a number of different ways of achieving positive impacts, and where data can be iteratively gathered about a number of cases to identify and test patterns of success.

Evaluative Questions

To answer these questions one needs to identify criteria against which to judge the evaluation results and decide how well the intervention performed overall or how successful or unsuccessful an intervention was. This includes determining what level of impact from the intervention will count as significant. Once the appropriate data are gathered, the results will be judged against the evaluative criteria.

For this type of evaluation, you should have a clear understanding of what indicates ‘success’ – is it represented as improvement in quality or value? One way to find out is by using a specific rubric that defines different levels of performance for each evaluative criterion, deciding what evidence will be gathered and how it will be synthesized to reach defensible conclusions about the worth of the intervention.

These are just a handful of commonly used impact evaluation methodologies in international development, to explore more methodologies, check out the Australian Government’s guidelines on “Choosing Appropriate Designs and Methods for Impact Evaluation.“

6. Data collection methods for impact evaluation

According to BetterEvaluation, well-chosen and well-implemented methods for data collection and analysis are essential for all types of evaluations and must be specified during the evaluation planning stage. One should have a clear understanding of the objectives and assumptions of the intervention, what baseline data exist and are available for use and what new data needs to be collected, how frequently, in what form, and what data do the beneficiaries need to deliver etc.

Reviewing the key evaluation questions can help to determine which data collection and analysis method can be used to answer each question and which data collection tools can be leveraged to gather all the necessary information. Sources for data can be stakeholder interviews, project documents, survey data, meeting minutes, and statistics, among others.

However, many outcomes of a development intervention are complex and multidimensional and may not be captured with just one method. Therefore, using a combination of both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, which is also called a mixed-methods approach is highly recommended as it allows us to combine the strengths and counteract the weaknesses of both qualitative and quantitative evaluation tools, allowing for a stronger evaluation design overall and provides a better understanding of the dynamics and results of the intervention.

But how do you know which method is right for you?

It is a good idea to consider all possible impact evaluation methods and to carefully weigh advantages and disadvantages before making a choice(s). The methods you select must be credible, useful and cost effective in producing the information that is important for your intervention. As mentioned above, many impact evaluation uses mixed methods, which is a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. Each method’s shortcomings can be fulfilled by using it in combination with other methods. Using a combination of different methods also helps to increase the credibility of evaluation findings as information from different data sources are converged, likewise, it can also help the team to gain a deeper understanding of the intervention, its effects and context.

7. Impact evaluation deliverables and timelines

Deliverables include an ‘inception report,’ a ‘ draft report’ and the ‘final evaluation report’ but in case of complex evaluations, ‘monthly progress reports’ might also be required. These reports contain detailed descriptions of the methodology that will be used to answer the evaluation questions, as well as the proposed source of information and data collection procedure. These reports must also indicate the detailed schedule for the tasks to be undertaken, the activities to be implemented and the deliverables, plus, clarification on the role and responsibilities of each member of the evaluation team.

We hope you found this article helpful. Our intention behind the 2-part series was to explain impact evaluations and its key components in a simple manner so that you can plan and implement your own impact evaluation more accurately and effectively.

Before we sign off, just a quick reminder that this list is not all-inclusive but rather a list of few key elements that many organisations choose to include in their impact evaluation work plan or ToR. If you know of any additional elements that are included in an evaluation work plan in your organisation then do reach out to us and we’d be happy to add them here.

This article is partly based on the Methodological brief “Overview of Impact Evaluation,” by Patricia Rogers at UNICEF, 2014.

Additional Resources:

- Outline of Principles of Impact Evaluation – OECD

- Technical Note on Impact Evaluation – USAID

- Impact Evaluation – BetterEvaluation

By Chandani Lopez Peralta, Content Marketing Manager at TolaData.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Data Collection

- Data Management

- Indicator Tracking

- Indicator Aggregation

- Custom Solutions

- IATI Reporting

- TolaData Partners

- Client Testimonials

- Help Center

- Quick Start Guide

- Knowledge Base

- Release Notes

- Case Studies

- Feature Focus

© TolaData 2024

Register and start your 14-day free trial.

(no credit card needed)

Subscribe to our newsletter.

The TolaBrief Newsletter

A monthly round-up of news and useful links on the digitisation of the sustainable development sector, from the team at TolaData

Tips for writing Impact Evaluation Grant Proposals

David mckenzie.

Recently I’ve done more than my usual amount of reviewing of grant proposals for impact evaluation work – both for World Bank research funds and for several outside funders. Many of these have been very good, but I’ve noticed a number of common issues which have cropped up in reviewing a number of them – so thought I’d share some pet peeves/tips/suggestions for people preparing these types of proposals.

First, let me note that writing these types of proposals is a skill that takes work and practice. One thing I lacked as an assistant professor at Stanford was experienced senior colleagues to encourage and give advice on grant proposals- and it took a few attempts before I was successful in getting funding. Here are some things I find a lot of proposals lack:

· Sufficient detail about the intervention – details matter both for understanding whether this is an impact evaluation that is likely to be of broader interest, as well as for understanding what the right outcomes to be measuring are and what the likely channels of influence are. So don’t just say you are evaluating a cash transfer program – I want to know what the eligibility criteria are, what the payment levels are, the duration of the program, etc.

· Clearly stating the main equations to be estimated – including what the main outcomes are, and what your key hypotheses are.

· Sufficient detail about measurement of key outcomes – especially true if your outcomes are indices or outcomes where multiple alternate measures are possible. E.g. if female empowerment is an outcome, you need to tell us how this will be measured. If you want to look at treatment heterogeneity by risk aversion, how will you measure this?

· How will you know why it hasn’t worked if it doesn’t work – a.k.a. spelling out mechanisms and a means to test them – e.g. if you are looking at a business training program, you might not find an effect because i) people don’t attend; ii) they attend but don’t learn anything; iii) they learn material but then don’t implement it in their businesses; iv) they implement practices in their businesses but implementing these practices has no effect; etc. While we all hope our interventions have big detectable effects, we also want impact evaluations to be able to explain why it didn’t work if somehow there is no effect.

· Discussion of timing of follow-up: are you planning multiple follow-up rounds? If only one round, why did you choose one year as the follow-up survey date – is this really the most important follow-up period of interest for policy and theory?

· Discuss what you expect survey response rates to be, and what you will do about attrition. Do you have evidence from other similar surveys of what likely response rates are like? Do you have some administrative data you can use to provide more details on attritors, or will you be using a variety of different survey techniques to reduce attrition? If so, what will these be?

· Power calculations: it is not enough to say “power calculations suggest a sample of 800 in each group will be sufficient” – you should provide sufficient detail on assumed means and standard deviations, assumed autocorrelations (and for cluster trials, intra-cluster correlations) that a reviewer should be able to replicate these power calculations and test their sensitivity to different assumptions.

· A detailed budget narrative: Don’t just say survey costs are $200,000, travel is $25,000. Price out flights etc, describe the per survey costs and explain why this budget is reasonable.

· Tell the reviewers why it is likely you will succeed. There is a lot to do to successfully pull off all the steps in a successful impact evaluation, and even if researchers do everything they can, it is inherently a risky business trying to evaluate policies that are subject to so many external forces. So researchers who have a track record of taking previous impact evaluations through to completion and publication should make clear this experience. But if this is your first impact evaluation, you need to provide some detail for the reviewers as to what makes it likely you will succeed – have you previously done fieldwork as an RA? Have you attended some course or clinic to help you design an evaluation? Do you have some senior mentors attached to your project? Are you asking first for money for a small pilot to prove you can at least carry out some key step? Make the case that you know what you are doing. Note this shouldn’t just be lines on a C.V., but some description in the proposal itself of the qualifications of your team.

Note I haven’t commented above about links to policy or explicit tests of theory. Obviously you should discuss both, but depending on the funder and their interests, one or the other becomes relatively more important. One concern I have with several grant agencies is how they view policy impact – I’m sympathetic to the view that what may be most useful for informing policy in many cases is not to test the policies themselves but to test underlying mechanisms behind their policies (see a post on this here ). So this might involve funding researchers to conduct interventions that are never themselves going to be implemented as policies, but which tell us a lot about how certain policies might or might not work. I think such studies should be scored just as strongly on policy criteria as some studies which look at explicit programs.

For those interested in seeing some examples of good proposals, 3ie has several successful proposals in the right menu here. Anyone else got any pet-peeves they come across when reviewing proposals, or must dos? Those on the grant preparation side, any questions or puzzles you would like to see if our readership has answers for?

Lead Economist, Development Research Group, World Bank

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Impact Evaluation in Practice - Second Edition

The second edition of the Impact Evaluation in Practice handbook is a comprehensive and accessible introduction to impact evaluation for policymakers and development practitioners. First published in 2011, it has been used widely across the development and academic communities. The book incorporates real-world examples to present practical guidelines for designing and implementing impact evaluations. Readers will gain an understanding of impact evaluation and the best ways to use impact evaluations to design evidence-based policies and programs. The updated version covers the newest techniques for evaluating programs and includes state-of-the-art implementation advice, as well as an expanded set of examples and case studies that draw on recent development challenges. It also includes new material on research ethics and partnerships to conduct impact evaluation. The handbook is divided into four sections: Part One discusses what to evaluate and why; Part Two presents the main impact evaluation methods; Part Three addresses how to manage impact evaluations; Part Four reviews impact evaluation sampling and data collection. Case studies illustrate different applications of impact evaluations. The book links to complementary instructional material available online, including an applied case as well as questions and answers. The updated second edition will be a valuable resource for the international development community, universities, and policymakers looking to build better evidence around what works in development.

Editor’s Note: The PowerPoints referenced in the book are unfortunately unavailable.

This book is a product of the World Bank Group and the Inter-American Development Bank .

DOWNLOAD IMPACT EVALUATION IN PRACTICE

- The Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund (SIEF)

Book Content

- Show More +

- Chapter 8: Matching

- Chapter 9: Addressing Methodological Challenges

- Chapter 10: Evaluating Multifaceted Programs

- Chapter 11: Choosing an Impact Evaluation Method

- Chapter 12: Managing an Impact Evaluation

- Chapter 13: The Ethics and Science of Impact Evaluation

- Chapter 14: Disseminating Results and Achieving Policy Impact

- Chapter 15: Choosing a Sample

- Chapter 16: Finding Adequate Sources of Data

- Chapter 17: Conclusion

- Show Less -

Email for further questions. Email

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. A lock ( ) or https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Keyboard Navigation

- Agriculture and Food Security

- Anti-Corruption

- Conflict Prevention and Stabilization

- Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance

- Economic Growth and Trade

- Environment, Energy, and Infrastructure

- Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment

- Global Health

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Innovation, Technology, and Research

- Water and Sanitation

- Burkina Faso

- Central Africa Regional

- Central African Republic

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- East Africa Regional

- Power Africa

- Republic of the Congo

- Sahel Regional

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Southern Africa Regional

- West Africa Regional

- Afghanistan

- Central Asia Regional

- Indo-Pacific

- Kyrgyz Republic

- Pacific Islands

- Philippines

- Regional Development Mission for Asia

- Timor-Leste

- Turkmenistan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- North Macedonia

- Central America and Mexico Regional Program

- Dominican Republic

- Eastern and Southern Caribbean

- El Salvador

- Middle East Regional Platform

- West Bank and Gaza

- Dollars to Results

- Data Resources

- Strategy & Planning

- Budget & Spending

- Performance and Financial Reporting

- FY 2023 Agency Financial Report

- Records and Reports

- Budget Justification

- Our Commitment to Transparency

- Policy and Strategy

- How to Work with USAID

- Find a Funding Opportunity

- Organizations That Work With USAID

- Resources for Partners

- Get involved

- Business Forecast

- Safeguarding and Compliance

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility

- Mission, Vision and Values

- News & Information

- Operational Policy (ADS)

- Organization

- Stay Connected

- USAID History

- Video Library

- Coordinators

- Nondiscrimination Notice and Civil Rights

- Collective Bargaining Agreements

- Disabilities Employment Program

- Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey

- Reasonable Accommodations

- Urgent Hiring Needs

- Vacancy Announcements

- Search Search Search

Impact Evaluation Designs

ADS 201 requires that each Mission and Washington OU must conduct an impact evaluation, if feasible, of any new, untested approach that is anticipated to be expanded in scale or scope through U.S. Government foreign assistance or other funding sources (i.e., a pilot intervention). Pilot interventions should be identified during project or activity design, and the impact evaluation should be integrated into the design of the project or activity. If it is not feasible to effectively undertake an impact evaluation, the Mission or Washington OU must conduct a performance evaluation and document why an impact evaluation wasn’t feasible.

Missions initially identify which of their evaluations during a CDCS period will be impact evaluations and which will be performance evaluations in their PMP. This toolkit’s page on the decision to undertake and impact evaluation is located in that section and may be worth reviewing as Mission’s prepare more detailed Project MEL plans.

USAID Evaluation Policy encourages Missions to undertake prospective impact evaluations that involve the identification of a comparison group or area, and the collection of baseline data, prior to the initiation of the project intervention. This type of impact evaluation can potentially be employed whenever an intervention is delivered to some but not all members of a population, i.e., some but not all firms engaged in exporting, or some but not all farms that grow a particular crop. This type of design may also be feasible when USAID projects introduce an intervention on a phased basis.

The identification of a valid comparison group is critical for impact evaluations. In principle, the group or area that receives an intervention should be equivalent to the group or area that does not. The more certain we are that groups are equivalent at the start, the more confident we can be in claiming that any post-intervention difference is due to the project being evaluated. For this reason, USAID evaluation policy prefers a method for selecting a comparison group that is called randomized assignment, as this method for constructing groups that do and do not receive an intervention is more effective than any other when it comes to ensuring that groups are equivalent on a pre-intervention basis.