If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- Beginning of World War II

- 1940 - Axis gains momentum in World War II

- 1941 Axis momentum accelerates in WW2

- Pearl Harbor

- FDR and World War II

Japanese internment

- American women and World War II

- 1942 Tide turning in World War II in Europe

- World War II in the Pacific in 1942

- 1943 Axis losing in Europe

- American progress in the Pacific in 1944

- 1944 - Allies advance further in Europe

- 1945 - End of World War II

- The Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb

- The United Nations

- The Second World War

- Shaping American national identity from 1890 to 1945

- President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 resulted in the relocation of 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast into internment camps during the Second World War.

- Japanese Americans sold their businesses and houses for a fraction of their value before being sent to the camps. In the process, they lost their livelihoods and much of their lifesavings.

- In Korematsu v. United States (1944) the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of internment. In 1988, the United States issued an official apology for internment and compensated survivors.

Executive Order 9066

Korematsu v. united states (1944), aftermath and redress, what do you think.

- On internment, see Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and The Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2013), 339; Roger Daniels, Sandra C. Taylor, Harry H.L. Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991); Wendy L. Ng, Japanese American Internment during World War II: A History and Reference Guide (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002).

- See David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 754.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 756.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 757.

- “Abyss of racism . . .” quoted in Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 335. “I dissent . . .” quoted in Otis Stephens and John Scheb, American Constitutional Law , v. 1 (Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2008), 224.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 759.

- Kennedy, Freedom from Fear , 760.

- William Yoshino and John Tateishi, " The Japanese American Incarceration: The Journey to Redress ," excerpted from Human Rights , American Bar Association, Spring 2000.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Japanese Internment Camps

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 17, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

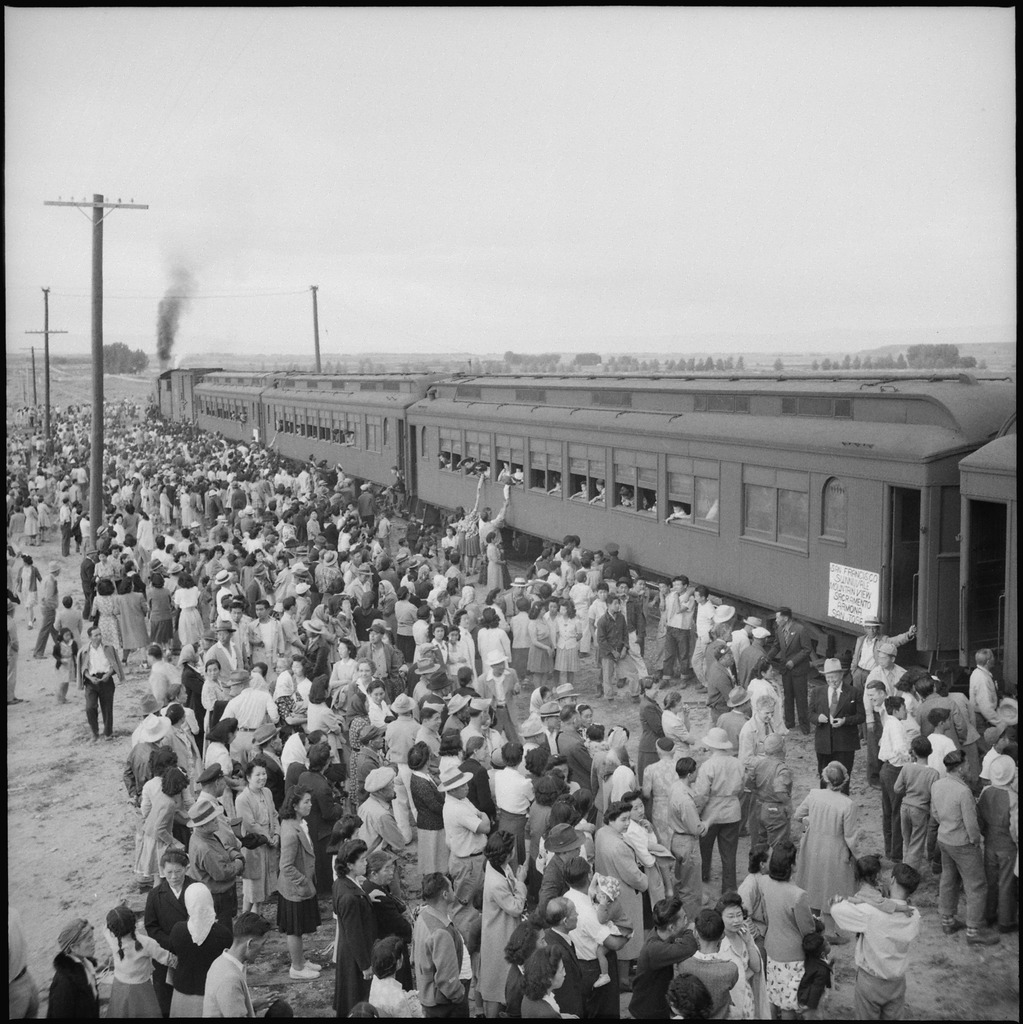

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066 . From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, would be incarcerated in isolated camps. Enacted in reaction to the Pearl Harbor attacks and the ensuing war, the incarceration of Japanese Americans is considered one of the most atrocious violations of American civil rights in the 20th century.

Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the stated intention of preventing espionage on American shores.

Military zones were created in California, Washington and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Executive Order 9066 affected the lives about 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens.

Canada soon followed suit, forcibly removing 21,000 of its residents of Japanese descent from its west coast. Mexico enacted its own version, and eventually 2,264 more people of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from Peru, Brazil, Chile and Argentina to the United States.

Anti-Japanese American Activity

Weeks before the order, the Navy removed citizens of Japanese descent from Terminal Island near the Port of Los Angeles.

On December 7, 1941, just hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI rounded-up 1,291 Japanese American community and religious leaders, arresting them without evidence and freezing their assets.

In January, the arrestees were transferred to prison camps in Montana, New Mexico and North Dakota, many unable to inform their families and most remaining for the duration of the war.

Concurrently, the FBI searched the private homes of thousands of Japanese American residents on the West Coast, seizing items considered contraband.

One-third of Hawaii’s population was of Japanese descent. In a panic, some politicians called for their mass incarceration. Japanese-owned fishing boats were impounded.

Some Japanese American residents were arrested and 1,500 people—one percent of the Japanese population in Hawaii—were sent to prison camps on the U.S. mainland.

Photos of Japanese American Relocation and Incarceration

John DeWitt

Lt. General John L. DeWitt, leader of the Western Defense Command, believed that the civilian population needed to be taken control of to prevent a repeat of Pearl Harbor.

To argue his case, DeWitt prepared a report filled with known falsehoods, such as examples of sabotage that were later revealed to be the result of cattle damaging power lines.

DeWitt suggested the creation of the military zones and Japanese detainment to Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Attorney General Francis Biddle. His original plan included Italians and Germans, though the idea of rounding-up Americans of European descent was not as popular.

At Congressional hearings in February 1942, a majority of the testimonies, including those from California Governor Culbert L. Olson and State Attorney General Earl Warren , declared that all Japanese should be removed.

Biddle pleaded with the president that mass incarceration of citizens was not required, preferring smaller, more targeted security measures. Regardless, Roosevelt signed the order.

War Relocation Authority

After much organizational chaos, about 15,000 Japanese Americans willingly moved out of prohibited areas. Inland state citizens were not keen for new Japanese American residents, and they were met with racist resistance.

Ten state governors voiced opposition, fearing the Japanese Americans might never leave, and demanded they be locked up if the states were forced to accept them.

A civilian organization called the War Relocation Authority was set up in March 1942 to administer the plan, with Milton S. Eisenhower from the Department of Agriculture to lead it. Eisenhower only lasted until June 1942, resigning in protest over what he characterized as incarcerating innocent citizens.

Relocation to 'Assembly Centers'

Army-directed removals began on March 24. People had six days notice to dispose of their belongings other than what they could carry.

Anyone who was at least 1/16th Japanese was evacuated, including 17,000 children under age 10, as well as several thousand elderly and disabled residents.

Japanese Americans reported to "Assembly Centers" near their homes. From there they were transported to a "Relocation Center" where they might live for months before transfer to a permanent "Wartime Residence."

Assembly Centers were located in remote areas, often reconfigured fairgrounds and racetracks featuring buildings not meant for human habitation, like horse stalls or cow sheds, that had been converted for that purpose. In Portland, Oregon , 3,000 people stayed in the livestock pavilion of the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Facilities.

The Santa Anita Assembly Center, just several miles northeast of Los Angeles, was a de-facto city with 18,000 incarcerated, 8,500 of whom lived in stables. Food shortages and substandard sanitation were prevalent in these facilities.

Life in 'Assembly Centers'

Assembly Centers offered work to prisoners with the policy that they should not be paid more than an Army private. Jobs ranged from doctors to teachers to laborers and mechanics. A couple were the sites of camouflage net factories, which provided work.

Over 1,000 incarcerated Japanese Americans were sent to other states to do seasonal farm work. Over 4,000 of the incarcerated population were allowed to leave to attend college.

Conditions in 'Relocation Centers'

There were a total of 10 prison camps, called "Relocation Centers." Typically the camps included some form of barracks with communal eating areas. Several families were housed together. Residents who were labeled as dissidents were forced to a special prison camp in Tule Lake, California.

Two prison camps in Arizona were located on Native American reservations, despite the protests of tribal councils, who were overruled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Each Relocation Center was its own "town," and included schools, post offices and work facilities, as well as farmland for growing food and keeping livestock. Each prison camp "town" was completely surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

Net factories offered work at several Relocation Centers. One housed a naval ship model factory. There were also factories in different Relocation Centers that manufactured items for use in other prison camps, including garments, mattresses and cabinets. Several housed agricultural processing plants.

Violence in Prison Camps

Violence occasionally occurred in the prison camps. In Lordsburg, New Mexico , prisoners were delivered by trains and forced to march two miles at night to the camp. On July 27, 1942, during a night march, two Japanese Americans, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot and killed by a sentry who claimed they were attempting to escape. Japanese Americans testified later that the two elderly men were disabled and had been struggling during the march to Lordsburg. The sentry was found not guilty by the army court martial board.

On August 4, 1942, a riot broke out in the Santa Anita Assembly Center, the result of anger about insufficient rations and overcrowding. At California's Manzanar War Relocation Center , tensions resulted in the beating of Fred Tayama, a Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) leader, by six men. JACL members were believed to be supporters of the prison camp's administration.

Fearing a riot, police tear-gassed crowds that had gathered at the police station to demand the release of Harry Ueno. Ueno had been arrested for allegedly assaulting Tayama. James Ito was killed instantly and several others were wounded. Among those injured was Jim Kanegawa, 21, who died of complications five days later.

At the Topaz Relocation Center , 63-year-old prisoner James Hatsuki Wakasa was shot and killed by military police after walking near the perimeter fence. Two months later, a couple was shot at for strolling near the fence.

In October 1943, the Army deployed tanks and soldiers to Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California to crack down on protests. Japanese American prisoners at Tule Lake had been striking over food shortages and unsafe conditions that had led to an accidental death in October 1943. At the same camp, on May 24, 1943, James Okamoto, a 30-year-old prisoner who drove a construction truck, was shot and killed by a guard.

Fred Korematsu

In 1942, 23-year-old Japanese-American Fred Korematsu was arrested for refusing to relocate to a Japanese prison camp. His case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where his attorneys argued in Korematsu v. United States that Executive Order 9066 violated the Fifth Amendment .

Korematsu lost the case, but he went on to become a civil rights activist and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998. With the creation of California’s Fred Korematsu Day, the United States saw its first U.S. holiday named for an Asian American. But it took another Supreme Court decision to halt the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Mitsuye Endo

The prison camps ended in 1945 following the Supreme Court decision, Ex parte Mitsuye Endo . In this case, justices ruled unanimously that the War Relocation Authority “has no authority to subject citizens who are concededly loyal to its leave procedure.”

The case was brought on behalf of Mitsuye Endo, the daughter of Japanese immigrants from Sacramento, California. After filing a habeas corpus petition, the government offered to free her, but Endo refused, wanting her case to address the entire issue of Japanese incarceration.

One year later, the Supreme Court made the decision, but gave President Truman the chance to begin camp closures before the announcement. One day after Truman made his announcement, the Supreme Court revealed its decision.

Reparations

The last Japanese internment camp closed in March 1946. President Gerald Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 in 1976, and in 1988, Congress issued a formal apology and passed the Civil Liberties Act awarding $20,000 each to over 80,000 Japanese Americans as reparations for their treatment.

Japanese Relocation During World War II . National Archives . Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. J. Burton, M. Farrell, F. Lord and R. Lord . Lordsburg Internment POW Camp. Historical Society of New Mexico . Smithsonian Institute .

Watch the documentary event, FDR . Available to stream now.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Japanese american internment - research guide, getting started, finding background information, off-campus access to library resources.

- Books/Media

- Articles - Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Bancroft Library

- Research Help

1. Use reference sources (see below) to learn basic facts about your topic, including dates, places, names of individuals and organizations, titles of specific publications, etc.

2. Find and read secondary sources (see Books/Media tab for sample searches to use in UC Library Search and the Articles tab for examples of searches to use in the America: History and Life database).

Make sure you look through the bibliographies of secondary sources, which can lead you to other secondary sources and to primary sources.

3. Search for primary sources (see Primary Sources tab).

More about the writing of papers:

- The Craft of Research (e-book)

This classic book on writing a college research paper is easily skimmed or deep enough for the truly obsessed researcher, explains the whole research process from initial questioning, through making an argument, all the way to effectively writing your paper.

Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students Professor Patrick Rael [a Berkeley PhD] has written a comprehensive but easy to skim web guide to writing history papers. Recommended by History Dept faculty.

There are two ways to connect to library resources from off-campus using the new library proxy:

- Links to online resources on library websites, such as UC Library Search, will allow you to login with CalNet directly.

- To access library resources found via non-UCB sites, such as Google or Google Scholar, you can add the EZproxy bookmarklet to your browser. Then, whenever you land on a licensed library resource, select your EZproxy bookmarklet to enable CalNet login.

More information is on the EZproxy guide .

The campus VPN provides an alternate method for off-campus access.

- Next: Books/Media >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 2:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/internment

Home — Essay Samples — History — American History — Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice

- Categories: American History

About this sample

Words: 749 |

Published: Sep 1, 2023

Words: 749 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical context: fear and paranoia, experiences in internment camps: resilience amid adversity, enduring impact on communities: seeking justice, lessons for the present and future, conclusion: remembering the past, shaping a just future.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1123 words

3 pages / 1356 words

1 pages / 445 words

6 pages / 2599 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American History

The Declaration of Independence, a foundational document in American history, serves as a beacon of freedom and democracy. This essay delves into the historical context surrounding the Declaration and explores how it was [...]

Throughout its history, the United States has engaged in various forms of imperialism, extending its influence and territorial control beyond its borders. American imperialism occurred during different periods, such as the late [...]

In the annals of American history, few individuals have a legacy as intricate and profound as George Mason. As one of the founding fathers, Mason’s contributions to the shaping of American democracy and the establishment of [...]

America, a nation marked by its continual evolution, has witnessed profound transformations in its history. This essay embarks on how America has changed over time, spanning political, social, and economic domains. It delves [...]

Shortly after the horrific events of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the lives of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Japenese people, both aliens and Citizens of the United States, would be changed in some major ways. Executive [...]

America’s history with drugs can be traced back to the 1800’s when opium surged in popularity following the American Civil War. Drugs were an integral part of American life with heroin being used medicinally to treat respiratory [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Japanese Internment in the US During World War II Research Paper

Intolerance demonstrated in the event, impact of racism on relocation, economic impact, works cited.

A country becomes exposed to multiple threats from other nations at times of war. As a result, the government takes any necessary measures that it perceives to be vital in promoting the national security of the nation, including subordination of the constitutional rights of certain individuals for the collective safety of the population.

In the United States, one of the key functions of the government is to provide equal protection for the constitutional rights of all citizens. Issues are therefore, raised during a wartime, with regard to individual liberty and collective security (Daniels 12).

Some questions were raised due to the temporary sacrifice of a particular group of people, the Japanese, with the intention of national survival. The issues raised were a result of the attack by Japanese aircraft against Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. These questions were associated with two cases brought to the U.S. Supreme Court within the context of World War II: Hirabayashi v. United States and Korematsu v. United States (Okihiro 62).

The American naval forces on Hawaii were devastated by the Japanese attack on pearl harbour. Some of the damage caused by the Japanese included the destruction of five American battleships and three cruisers, as well as the death of over 2,200 and injuries on over 1,100 military personnel. The then president was Franklin D. Roosevelt, who re-assured the public that the US would retaliate against the Japanese, which led to their entry in to the World War II (Robinson 29).

The Japanese moved fast to occupy the territories previously in the hands of the US, and the more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry in the west coast raised issues for the president’s cabinet. As a result, general DeWitt wanted to relocate all of them to the interior of the country, where they could be kept from getting in touch with the enemy (Irons 22).

The then U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle urged caution, since he believed that forcible relocation of the Japanese Americans would violate their due process rights under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. However, most of the Presidential advisers emphasized the importance of military necessity and national survival.

As a result, “President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, providing authority for military commanders to establish special zones from which civilians might be excluded for reasons of national defence, On February 22, 1942” (Robinson 33). The President based his order on the Espionage Act of 1918 and statutes enacted by Congress in 1940 and 1941 to enhance the chief executive’s wartime powers (Robinson 33).

On March 18, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9102 to establish the War Relocation Authority. This executive agency was empowered to relocate the people identified by military commanders under the provisions of the previously issued Executive Order 9066. More than 110,000 Japanese were commanded to abandon their dwellings in places that the military had identified as sensitive parts of the West Coast. Anti-Japanese frenzy in the United States since the beginning of the century fueled calls for removal (Unk 1).

About 45,000 Japanese nationals and 75,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry were deprived of liberty and property without criminal charges or even a trial, in the period between 1942 and 1946 (Okihiro 64).

Due to their ancestry, all people of Japanese ancestry were expelled from their homes, and confined in inland detention camps; this did not apply to American citizens of German or Italian ancestry, who were on the same side as the Japanese during the war. The events that occurred marked one of the greatest blows to constitutional liberties on the American citizens (Okihiro 65).

There had been many previous instances of hostility upon the Japanese and other Asian immigration for many decades before the forceful eviction after the attack at pearl harbour. The attitude of the public was emphasized after the attack, during World War II. The reason why the west coast public was not sympathetic with the Japanese Americans is because the National Guard units from eleven western states were fighting in the Philippines, where they were tortured and starved by their Japanese captors (Daniels 17).

During the war, one of the key attributes in the policy of evacuation and resettlement was to protect the Japanese-Americans from population rage. There were many causes for the evacuation that had little to do with racism.

Peter Irons wrote level-headedly about this in 1983: “To cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were present, merely confuses the issue. Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race…He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire….” (24).

There are a few Japanese Americans who lost their property during the mass eviction, to unscrupulous people, though the army tried to safeguard the evacuees’ property. For those who had crops, the yields were harvested and sold at favourable prices. The gains were then put in their bank accounts, for their access.

The fury directed at the Japanese Americans started in the nineteenth century, when the first immigrants arrived during the California Gold Rush (Unk 1). The discovery of gold in California led to a scramble for control of the gold mines and ultimately for control of the Territory of California.

About 25 percent of the miners in California during the Gold Rush came from China. The English speaking newcomers who had previously established dominance over the native, Spanish, and Mexican Californians were in no mood to tolerate further competition. Using acts of terrorism (e.g., mass murder and arson) the white newcomers drove the Chinese out of the mining areas (Unk 1).

The Japanese Americans were conditionally released, that is about 33% of them, between 1943 and 1944. College students were allowed to attend school, though they had to report to government officials. The young men and women were also released for military duty. The remaining 67% were not allowed to leave the camps for the whole duration of the war. The fathers lost their role as breadwinners, and the families fell apart since the children were controlled by the military.

The uncertainties of the situation that the Japanese Americans found themselves in led to some committing suicide (Murray and Daniels 53). Others died due to the harsh environment, and the lack of medical facilities. Communication channels were monitored by the camp administration, the Japanese language was banned at public meetings, and Buddhist religious practices were suppressed (Irons 24).

Other extreme measures like deportation, sterilization or stripping off the citizenship of the Japanese Americans were not pursued, though the events that took place had a lot to do with racism, and the attacks on pearl harbour provided the Americans with an opportunity to get rid of the Japanese Americans, and they went for it, going as far as offering them for exchange with American prisoners of war (Murray and Daniels 60).

Daniels, Roger. The Politics of Prejudice. New York: Atheneum, 1970. Print.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Murray, Alice Yang and Roger Daniels. What Did the Internment of Japanese Americans Mean? Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000.

Okihiro, Gary Y. Whispered Silences: Japanese Americans and World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Unk. The Exclusion of the Ethnic Japanese from the US West Coast in 1942. 1998. Web.

- Minidoka and Kooskia Japanese-American Internment Camps

- Newspaper Coverage of Japan-America Internment in WW2 and the Civil Rights Movement

- Friday Harbour Resort: Offerings, Target, and Prices

- Sexual Harassment: Tail Hook-Scandal

- Politics in the 1960s: Vietnam War, Bay of Pigs Invasion, Berlin Wall

- Twentieth Century President

- The Three Main Causes of Great Depression

- To what extent did the text promote socialism?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, June 11). Japanese Internment in the US During World War II. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-internment-in-the-us-during-world-war-ii/

"Japanese Internment in the US During World War II." IvyPanda , 11 June 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-internment-in-the-us-during-world-war-ii/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Japanese Internment in the US During World War II'. 11 June.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Japanese Internment in the US During World War II." June 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-internment-in-the-us-during-world-war-ii/.

1. IvyPanda . "Japanese Internment in the US During World War II." June 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-internment-in-the-us-during-world-war-ii/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Japanese Internment in the US During World War II." June 11, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-internment-in-the-us-during-world-war-ii/.

Photo Essay: Japanese Americans Return to the West Coast After WWII Incarceration

January 2, 2020

The exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast during WWII came to an official end on January 2, 1945. By the end of the year, nine of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps had been shut down — although Japanese American “renunciants” and Japanese Latin Americans slated for deportation to Japan remained imprisoned even after the war’s end. On the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the end of Japanese American incarceration, we take a look back at some of the images from this moment in history.

By 1945, many Japanese Americans, particularly college- and working-age Nisei, had already left the camps to “resettle” in Midwest and East Coast hubs, which meant that the majority of those who remained were elders and families with young children for whom another forced move was a significant hardship. Incarcerees were ordered to leave and given just $25 and a one-way ticket home — but many had nothing to come back to.

Most returned to the West Coast without serious incident, but well-publicized discriminatory and terrorist actions greeted many returnees. Against this backdrop, Japanese Americans struggled to find housing and employment, and many turned to overcrowded hostels and government-run trailer parks as a last resort.

The extreme hardships of the immediate return to the West Coast eased for many over the next decade. By 1950, the Nikkei population on the West Coast was well over 80% of what it had been before the war, and before long Japanese Americans came to be seen as a “model minority” — although that image ignored the many, particularly Issei, who never recovered, as well as long-term cultural losses and psychological effects . As Brian Niiya writes in the Densho Encyclopedia , “Incarceration had not killed Japanese American communities—and Japanese American identity—but it had changed it in ways that wouldn’t be understood for many years.”

Adapted from Brian Niiya’s Densho Encyclopedia article “Return to the West Coast.” Read more: http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Return%20to%20West%20Coast/

[Header photo: Original caption: “Last of the residents of the Amache Relocation Center board the train at Granada for the journey to the west coast or to new homes elsewhere in the country.” Photo by Hikaru Iwasaki, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Categories: after camp , anniversary , photo essay

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Japan

Japanese Internment Essays Examples

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Japan , Internment , America , Americans , Military , War , Family , Order

Words: 1100

Published: 03/08/2023

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

Introduction

The Japanese attacked the Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, prompted the United States to immediately declare war against Japan. The Pearl Harbor assault and the eventual participation of the US in the Second World War have a widespread impact, and this includes a detrimental effect on the lives of the Japanese Americans in the United States. A few weeks after both countries declared war against each other, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, with the directive to designate some parts of the West Coast under military jurisdiction. The Executive Order did not specifically mention the internment of the Japanese Americans, but it nevertheless gave the military the power to exclude the Japanese from the area.

The Directive for Relocation

The Executive Order granted an extensive power to the Secretary of War and military officials who did not hesitate to use it according to their own prerogative. Further, it also gave the military the authority to evacuate the people given a reasonable justification. Thus, after the passage of the EO, the War Department administered the extraction of the Japanese Americans from the West Coast, according to what they referred to as the necessities of military wartime. Accordingly, the power of EO 9066 was used to exclude all people of Japanese ancestry from the entire region of the West Coast. The reason for the eventual internment of people of Japanese ancestry can be traced from intelligence reports that was taken as an evidence of espionage activity among members of the Japanese community. While the report was said to be false, and was fabricated by people who have anti-Japanese sentiments, the Japanese remained to be the focus of the executive order. According to studies, some of the prejudices against the Japanese during that time were not generally related to the ongoing war. There were selfish reasons why the Japanese were singled out and interned; a portion of a letter sent to Congressman John Anderson indicated that white Americans thought that there is no way for the Japanese to assimilate with the white race. Some of them saw the war as an opportunity to eventually get rid of the Japanese, whom they thought as competitors in many aspects. Other primary documents indicated that some Americans did not like the Japanese and have hoped to get rid of them after the war. Nevertheless, some found it sensible to extract the Japanese Americans from the West Coast because of security risk should the Japanese military attack the American mainland. Upon learning about the order to evacuate, many Japanese Americans sold their properties, and the urgency of the order resulted to massive economic loss on the part of families who were forced to sell their belongings at a much cheaper price. At first, the Japanese people were requested to voluntarily comply with the order, but the military leaders thought it better to be in full control and made the order compulsory. The Japanese men were rounded up by the military, while the women were forced to sell their properties in just a few days. Many of the Japanese stayed in temporary relocation sites until he completion of ten internment camps in the more remote places of the country.

Life at the Internment Camps

The life in the internment camps was difficult, as families were packed to share tar-papered barracks. The relocation was described as cruel and harsh; about four to five families share a barrack, and a common area for their necessities. Children comprised a large number of the interned population, and some would later recount how soldiers, with their rifles marched them towards the internment camps. There was insufficient medical care at the camps, and some of the internees died due to inadequate medical attention and the stressed associated with being camped and watched by the military. Moreover, the incarcerees did not only contend with the inadequate housing and facilities, but they also have to deal with the extreme climate in the relocation sites. While medical personnels were assigned in the camps, overcrowding and the unsanitary conditions contributed to the increased number of diseases among the internees. While they were expected to live their lives normally, such as the demand to allow their children to go to school, it was difficult for the families to adjust to life in the internment camps. The American government expected the Japanese people to be self-sufficient, but starting life with little support and in an arid place like the relocation sites was not easy for the families who have nothing with them except a few basic possessions. Men were forced to accept menial tasks despite low wages, and women have to deal with the shame associated with sharing commodes that exposed them to others. The internment camp brought havoc to the traditional Japanese families, for example, family members no longer share their meals such that men shared meal times with other men while the mothers were left with the children. Sometime in 1943, the internees were required to prove their allegiance to the United States by requiring adults to answer the loyalty questionnaire. Those who were found to be disloyal were confined in separate a separate site in Tule Lake, in addition to other forms of discrimination.

Life After the Internment

It was in 1944 when the EO 9066 was finally rescinded, and those who were forced to confinement were to assimilate back into the society. Some Japanese Americans who felt resentment of their undue treatment relinquished their American citizenship, still others went back to integrate. Fresh from being confined and closely monitored by the military, the Japanese found it difficult to regain the economic loss associated with their more than two years of confinement. Moreover, it was found that it was only about more than ten years when the United States government started to provide reparation of the economic loss of the Japanese during their confinement. In 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act as an expression of apology to the internees.

Significance of the Internment

After many years of examination, it was found that the internment of the Japanese Americans during WWII was unjustifiable. For one, the allegation of Japanese espionage was never validated, and many of the internees were people who have already proven their allegiance to the country before the war. Nevertheless, the internment of the Japanese during that time shall serve as a lesson for all people and governments to ponder. Several studies were conducted to examine the merits of the forced confinement, and the compulsory internment of the Japanese Americans will serve as a basis to understand the roots, and consequences of such events.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 2498

This paper is created by writer with

ID 285920420

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Free argumentative essay on sociology, example of essay on native americans, chi square test essay examples, example of essay on shell v rw sturge ltd, a response to language by martin heidegger critical thinking sample, research paper on punishment in early and contemporary psychology, nutrition and weight status essay sample, importance of having laws and the current criminal system in place research paper example, potential security vulnerability report, tay sachs disease research paper examples, two kinds an analysis of the perspectives essay, term paper on french enlightenment philosophical notes by voltaire and dalemberts dream by diderot, free essay on writer chose, product essay example, essay on creation stories in world religions, comparison of the laws essay examples, free essay on self assessment, good example of what is rock n roll essay, methodology thesis proposals, salary thesis proposals, america thesis proposals, revolution thesis proposals, gossip research papers, sponsorship research papers, cockpit research papers, shore research papers, bandwidth research papers, decoration research papers, retreat research papers, sailing research papers, prey research papers, infinite research papers, panic disorder essays, panic attack essays, jubilation essays, cardinality essays, balance of trade essays, indenture essays, sunscreen essays, stoicism essays, growing essays, regulating essays, penal code essays.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

BUY THIS BOOK

2006 --> 2006 392 pages. $70.00

Hardcover ISBN: 9780804751476

Honorable Mention in the 2006 AAAS Book Award, sponsored by the Association for Asian American Studies.

This is a collection of the last essays by Yuji Ichioka, the foremost authority on Japanese-American history, who passed away two years ago. The essays focus on Japanese Americans during the interwar years and explore issues such as the nisei (American-born generation) relationship toward Japan, Japanese-American attitudes toward Japan's prewar expansionism in Asia, and the meaning of "loyalty" in a racist society—all controversial but central issues in Japanese-American history.

Ichioka draws from original sources in Japanese and English to offer an unrivaled picture of Japanese Americans in these years. Also included in this volume are an introductory essay by editor Eiichiro Azuma that places Ichioka's work in Japanese-American historiography, and a postscript by editor Chang reflecting on Ichioka's life-work.

About the authors

The late Yuji Ichioka was the founding father of the scholarly study of Japanese-American history. His book on the immigrant generation in America, The Issei: The World of the First-Generation Japanese Immigrants, 1885-1924 (1988), is considered a classic. He invented the term Asian American, and trained many of the scholars now teaching Asian American history at colleges and universities.

— H-Net Reviews

"Ichioka's ability to comprehend the complexity of the situation raises many fresh, thought-provoking quesitons in a field that appeared near saturation point." Japanese Studies

The Peculiar Afterlife of Slavery

Caroline H. Yang

Mandarin Brazil

Ana Paulina Lee

Transpacific Reform and Revolution

Zhongping Chen

Nisei Naysayer

James Matsumoto Omura Edited by Arthur A. Hansen

Citizens, Immigrants, and the Stateless

Michael R. Jin

Minor Transpacific

David S. Roh

Here, There, and Elsewhere

Tahseen Shams

Mary Kitagawa

Karen M. Inouye

Performing Chinatown

William Gow

The Chinese and the Iron Road

Edited by Gordon H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin

Koreatown, Los Angeles

Shelley Lee

Inscrutable Belongings

Stephen Hong Sohn

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Jamelle Bouie

Trump’s Taste for Tyranny Finds a Target

By Jamelle Bouie

Opinion Columnist

Among the worst episodes in American history are those moments when the federal government deploys the full weight of its power against the most vulnerable people in the country: the Trail of Tears and the Fugitive Slave Act in the 19th century and Japanese internment in the middle of the 20th, to name three.

If he is granted a second term in the White House, Donald Trump hopes to add his own entry to this ignominious book of national shame.

Trump’s signature promise, during the 2016 presidential election, was that he would build a wall on the U.S. border with Mexico. His signature promise, this time around, is that he’ll use his power as president to deport as many as 20 million people from the United States.

“Following the Eisenhower model ,” he told a crowd in Iowa last September, “we will carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.”

It cannot be overstated how Trump’s deportation plan would surely rank as one of the worst crimes perpetrated by the federal government on the people of this country. Most of the millions of unauthorized and undocumented immigrants in the United States are essentially permanent residents. They raise families, own homes and businesses, pay taxes and contribute to their communities. For the most part, they are as embedded in the fabric of this nation as native-born and naturalized American citizens are.

What Trump and his aide Stephen Miller hope to do is to tear those lives apart, rip those communities to shreds and fracture the entire country in the process.

“The Trump immigration plan,” notes Radley Balko , a journalist who writes primarily on civil liberties, in his Substack newsletter, “would be the second-largest forced displacement of human beings in human history, on par with Britain’s disastrous partition of India, and second only to total forced displacement during World War II.”

What is the plan, exactly? It begins, as Miller explained in an interview with Turning Point USA’s Charlie Kirk last year, with creating a national deportation force consisting of agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Border Patrol and other federal agencies, as well as the National Guard and local law enforcement officials. The administration would empower this deportation force to scour the country for unauthorized and undocumented immigrants. It would move from state to state, city to city, neighborhood to neighborhood and, finally, house to house, looking for people who, according to Trump and Miller, do not belong. This deportation force would raid workplaces and stage public roundups, to create a climate of fear and intimidation.

Of course, in the heat of the moment, it isn’t actually all that easy to determine who may be an unauthorized or undocumented immigrant. But these won’t be selective apprehensions. How could they be? Instead, what we’ll see in practice is an indiscriminate roundup of anyone who might appear to be an immigrant — a mass campaign of racial and ethnic profiling.

Because it would be beyond the capacity of the federal government to immediately return detainees to their “home” countries, the Trump team also plans to build “vast holding facilities that would function as staging centers” for immigrants on land near the Texas border. Internment camps, essentially.

It is worth remembering here that in addition to its wanton cruelty, Trump’s policy of child separation was also noteworthy for the poor conditions suffered by separated families living in government facilities. Child detainees lacked adequate food , water and sanitation. There were also reports of mistreatment , as in the case of the Border Patrol agents who were accused of telling detained women to drink out of toilet bowls.

Now, imagine the conditions that might prevail for hundreds of thousands of people crammed into hastily constructed camps, the targets of a vicious campaign of demonization meant to build support for their detention and deportation. If undocumented immigrants really are, as Trump says, “ poisoning the blood of our country ,” then how do we respond? What do we do about poison? Well, we neutralize it.

There are roughly 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States, according to a recent estimate by the Pew Research Center. Trump’s number of “probably 15 million and maybe as many as 20 million” is pulled from nowhere — an assumption based on the inchoate sense that the official numbers are wrong and there must be more “illegals” to apprehend than anyone truly realizes.

To reach this goal, Miller and Trump would almost certainly have to round up citizens as well. But that is also part of the plan. On the first day of his second term, the campaign has let it be known, Trump will sign an executive order “to withhold passports, Social Security numbers and other government benefits from children of undocumented immigrants born in the United States.”

Neither Trump nor Miller appears to have made any distinction between the undocumented children of undocumented immigrants and the native-born children of undocumented immigrants, which fits their opposition to the Constitution’s guarantee of birthright citizenship through the 14th Amendment. Under the Trump deportation plan, citizenship will not save those who have the wrong background.

The Trump campaign’s promise to detain and deport millions of immigrants, along with many American citizens, is a promise to plunge the country into an authoritarian nightmare. It is also a promise of strife and pervasive civil conflict.

It wouldn’t be the first time that Americans responded to an effort of this sort with violence. With the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which essentially deputized all authorities and private citizens in free states as slave catchers required to return all escaped slaves to their enslavers, came widespread, armed resistance to efforts to carry out the law. You did not have to be sympathetic to the plight of the enslaved to be outraged by the notion that you could be dragooned into acting as a bounty hunter for state-sanctioned human traffickers.

The political consequence of the Fugitive Slave Act, to the dismay of Southern lawmakers, was to radicalize countless Northerners against the so-called Slave Power and raise sectional tensions to a point of almost no return. The law did not cause the Civil War, but it was the provocation that set the stage for a decade of conflict that led, inexorably, to war.

Do we not think that a mass deportation program, with roving bands of armed agents, would result in similar upheaval? Do we not think that there would be violent resistance to agents storming homes, churches and businesses to seize and detain people? And do we not think that a Trump who wanted, during his first term, to shoot protesters would see this as an opportunity to do so — a hoped-for chance to invoke the Insurrection Act, mobilize the military and crush his political opponents?

We talk often, these days, of illiberalism. It is has become a bit of a buzzword. Often the focus is illiberalism in elite spaces, usually the classrooms and common areas of selective colleges. Sometimes the focus is on particular politicians. But what we are seeing here from Trump isn’t simply a distaste for liberal values; it is a taste for genuine tyranny and bona fide despotism, one that complements his endless praise for dictators and strongmen.

Rhetoric matters, and what candidates say is not simply for show. At every opportunity, Trump has placed the mass deportation of millions of people at the center of his campaign. It is a promise. And the promises a presidential candidate makes while on the trail are the promises a president tries to keep.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here's our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Jamelle Bouie became a New York Times Opinion columnist in 2019. Before that he was the chief political correspondent for Slate magazine. He is based in Charlottesville, Va., and Washington. @ jbouie

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Between 1942 and 1945 a total of 10 camps were opened, holding approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans for varying periods of time in California, Arizona, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Arkansas. Japanese American internment, the forced relocation by the U.S. government of thousands of Japanese Americans to detention camps during World War II.

President Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 resulted in the relocation of 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast into internment camps during the Second World War. Japanese Americans sold their businesses and houses for a fraction of their value before being sent to the camps. In the process, they lost their livelihoods ...

Basically, the Japanese American communities' internment during WW2 was justified by the American government that classified it as a military necessity. The period was characterized by an indiscriminate roundup of Japanese and Japanese Americans who lived in the states considered a security threat since the main foes of the then America was ...

In the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack, over 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in internment camps, ostensibly for national security reasons. This essay will critically examine the argument that Japanese internment was justified, focusing on the historical context, the legal and moral implications, and the ...

In an effort to curb potential Japanese espionage, Executive Order 9066 approved the relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps. At first, the relocations were completed on a voluntary basis. Volunteers to relocate were minimal, so the executive order paved the way for forced relocation of Japanese-Americans living on the west coast.

Japanese internment camps were established during World War II by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through his Executive Order 9066. From 1942 to 1945, it was the policy of the U.S. government that ...

Essays include: - A short narrative history of the Japanese in America before World War II - The evacuation - Life within barbed wire-the assembly and relocation centers - The question of loyalty-Japanese Americans in the military and draft resisters - Legal challenges to the evacuation and internment - After the war-resettlement and redress A ...

Japanese Internment Camps: Tragedy and Injustice. One of the most lamentable episodes in American history is the forced internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, revealing the dark underbelly of prejudice and fear during times of crisis. This essay delves into the historical context that led to this tragic event, the harrowing ...

Dec. 7, 2017. The day after the early-morning surprise assault on Pearl Harbor, on Dec. 7, 1941, the United States formally declared war on Japan and entered World War II. Over the next few months ...

All Japanese in Military Area 1 in California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona have been removed into Army custody. December 17, 1944 Relocation orders are revoked and exclusion is lifted, effective January 2, 1945.

Journalism, Behind Barbed Wire For these journalists, the assignment was like no other: Create newspapers to tell the story of their own families being forced from their homes, to chronicle the hardships and heartaches of life behind barbed wire for Japanese-Americans held in World War II internment camps.

Japanese Americans were finally free to return to their homes on December 17, 1944. Their homes were marked by the vigilante violence and agitation of pressure group. Most of the internment camps did not close until October 1946. The U.S. government enacted the Civil Liberties Act.

This research paper, "Japanese Internment in the US During World War II" is published exclusively on IvyPanda's free essay examples database. You can use it for research and reference purposes to write your own paper.

Ultimately, the internment of Japanese Americans during the Pacific War stemmed from American fears of a possible Japanese assault on the US west coast and specifically impacted the Nisei community. On February 19, 1942, during World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, leading to the relocation of Japanese Americans to ...

January 2, 2020. The exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast during WWII came to an official end on January 2, 1945. By the end of the year, nine of the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps had been shut down — although Japanese American "renunciants" and Japanese Latin Americans slated for deportation to Japan remained imprisoned even after the war's end.

Argumentative Essay On Japanese American Internment Camps. In 1942 many Japanese Americans were faced with a problem that most Americans will never experience. They were ripped of their American lives and rights and placed in Internment camps. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that was put in place "to prescribe ...

Introduction. The Japanese attacked the Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, prompted the United States to immediately declare war against Japan. The Pearl Harbor assault and the eventual participation of the US in the Second World War have a widespread impact, and this includes a detrimental effect on the lives of the Japanese Americans in the United States.

The Internment Of Japanese Americans. were dropped on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the American people's fear of the Japanese grew dramatically, especially for those Japanese living in America. Almost every Japanese American was seen as a threat to the country. On February 19th, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was issued by President ...

This is a collection of the last essays by Yuji Ichioka, the foremost authority on Japanese-American history, who passed away two years ago. The essays focus on Japanese Americans during the interwar years and explore issues such as the nisei (American-born generation) relationship toward Japan, Japanese-American attitudes toward Japan's prewar expansionism in Asia, and the meaning of loyalty ...

Japanese Internment Essay. 975 Words4 Pages. Lilly Mulhern Mr. Skea Social Studies May 26, 2023 Japanese Internment Japanese American internment was not a good solution that the United States had gone with. The Attack on Pearl Harbor was December 7, 1941, and the Japanese military did a surprise attack on the United States Naval Base at Pearl ...

Japanese Internment Camps Are a Dark Period. PAGES 2 WORDS 553. Japanese internment camps are a dark period of American history. The forced incarceration of Americans of Japanese descent was based solely on racism and a culture of fear. During World War II, Americans also counted Italians and Japanese as their archrivals but of these groups, it ...

Throughout World War II, Japanese internment camps was considered unjust because of the conditions of the relocation and the aftermath that followed. The process of relocating people of Japanese descent was unmerited. For example, Japanese-Americans had twenty-four hours to sell their homes and businesses in 1942 ('Japanese Internment in ...

There are roughly 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States, according to a recent estimate by the Pew Research Center. Trump's number of "probably 15 million and maybe as many ...