An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Value of Peer Learning in Undergraduate Nursing Education: A Systematic Review

Robyn stone, simon cooper.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Robyn Stone: [email protected]

Academic Editors: L. H. Beebe and M. M. Funnell

Received 2012 Dec 23; Accepted 2013 Feb 9; Collection date 2013.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The study examined various methods of peer learning and their effectiveness in undergraduate nursing education. Using a specifically developed search strategy, healthcare databases were systematically searched for peer-reviewed articles, with studies involving peer learning and students in undergraduate general nursing courses (in both clinical and theoretical settings) being included. The studies were published in English between 2001 and 2010. Both study selection and quality analysis were undertaken independently by two researchers using published guidelines and data was thematically analyzed to answer the research questions. Eighteen studies comprising various research methods were included. The variety of terms used for peer learning and variations between study designs and assessment measures affected the reliability of the study. The outcome measures showing improvement in either an objective effect or subjective assessment were considered a positive result with sixteen studies demonstrating positive aspects to peer learning including increased confidence, competence, and a decrease in anxiety. We conclude that peer learning is a rapidly developing aspect of nursing education which has been shown to develop students' skills in communication, critical thinking, and self-confidence. Peer learning was shown to be as effective as the conventional classroom lecture method in teaching undergraduate nursing students.

1. Introduction

Nursing education studies have often focused on traditional teaching methods such as classroom lecture learning, a behaviourism-based teaching method based on passive learning [ 1 ]. More effective student-centric learning methods are now being utilized to encourage active student participation and creative thinking [ 2 – 4 ]. One of these methods is peer learning, in which peers learn from one another, involving active student participation and where the student takes responsibility for their learning. Despite being used for many years, one of the barriers to advancement of peer learning is a lack of consistency in its definition [ 5 ]. It is known by different interchangeable titles such as “cooperative learning,” “mentoring,” “peer review learning,” “peer coaching,” “peer mentoring,” “problem-based learning,” and “team learning.”

Peer learning has been used in education to address critical thinking, psychomotor skills, cognitive development, clinical skills, and academic gains [ 6 – 9 ]. One type of peer learning is problem-based learning (PBL) which is characterized by students learning from each other and from independently sourced information [ 10 ]. It is student centered, utilizing group work with the analysis of case studies as a means of learning. Alternatively “peer tutoring” involves individuals from similar settings helping others to learn, which may occur one-on-one or as small group sessions [ 11 ]. In nursing, high student numbers increase pressures [ 12 ] whilst varied and innovative teaching methods are beneficial [ 13 ] with peer learning offering a strategy that may be advantageous.

The Oxford Dictionary (2009) defines a “peer” as someone of the same age or someone who was attending the same university. The term “peer” can also refer to people who have equivalent skills or a commonality of experiences [ 14 ]. Both these definitions suit the concept of peer learning described here. The current study aimed to address the following research questions: (i) do undergraduate nursing students benefit from peer learning? and (ii) what approaches to peer learning are the most effective?

Operational terms as shown in Table 1 were developed after consulting several studies. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. A search was conducted for peer-reviewed papers published in English between the years 2000 and 2010 that discussed any aspect of the curriculum for undergraduate or general nursing courses (e.g., clinical skills, communication, patient interaction, or theoretical knowledge).

Operational definitions.

Sources: [ 10 , 14 , 45 , 48 – 51 ].

The literature search was undertaken using the PICO algorithm of Participant, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome and guidelines from The Cochrane Handbook [ 15 ]. For this study the following terms were used:

participant—undergraduate nursing students,

intervention—peer learning,

comparison—classroom lecture learning,

outcome—improvement in theory results or results of practical assessment or personal feelings relating to comfort, confidence, or competence.

A systematic literature search of multiple databases and search engines was undertaken using the keywords and the search strategy described in the following. The keywords used were student nurse, undergraduate nurse, peer learning, peer tutoring, peer mentoring, education, and opinion leaders. Also used were variations and truncations of these words, for example, peer education, nurse education, and problem-based learning. Each of the key words was searched for individually and then in combination with all others.

In addition, a number of key nursing journals such as Journal of Advanced Nursing and Journal of Nursing Education were hand-searched between the years 2000 and 2010. Snowballing, identifying suitable articles from the references of the selected studies, was then conducted to locate further studies.

Studies with all levels of evidence that met the criteria were included because studies in peer learning tended towards quasiexperimental, observational, or case study designs which are all lower on the hierarchy of evidence [ 16 ].

Two reviewers conducted a quality analysis of each study using quality criteria for qualitative and quantitative studies of the Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (CASP) [ 17 ]. They assessed methodology, validity, sample type, selection method, level of evidence, and any attrition rate and its effect (including biases), to determine selection. Consensus was reached through discussion. Data extraction and thematic analysis were undertaken to synthesize the data. Meta-analysis was not undertaken due to the inconsistent definition of “peer” and potential for bias if different methods of peer learning were combined. Although the primary review was conducted by a single researcher, inclusion and exclusion criteria were adhered to, using a transparent reporting process to allow the search to be reproduced.

Data were extracted and summarized in separate tables: quantitative studies ( Table 2 ), qualitative studies ( Table 3 ), and mixed method studies ( Table 4 ). Drawing from this, data outcomes were collated into themes and subthemes; for example, the resources theme had three subthemes: faculty, students, and peers.

Summary of included studies.

PBL: problem-based learning, CLL: classroom lecture learning.

Quantitative studies.

Qualitative studies.

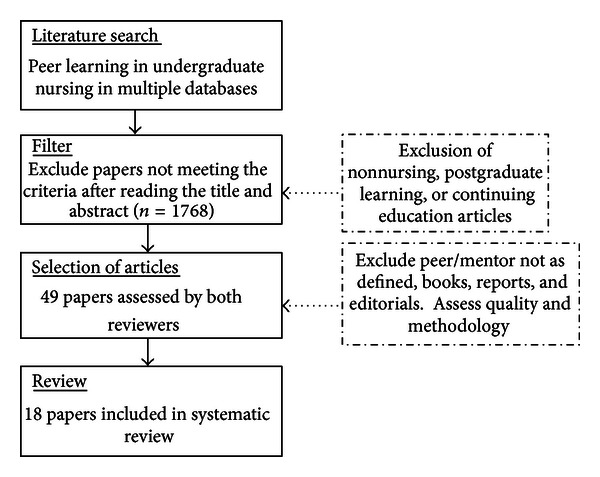

Initially, 1813 studies were screened using the aforementioned criteria and 18 studies were selected for review. A flow chart ( Figure 1 ) shows the selection process including number of studies excluded at each stage and the reason for exclusion.

Flow chart of the systematic review selection process.

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

Participants were undergraduate nursing students from first to final year. In line with nursing demography the majority of participants were females. Participant numbers and study duration varied, for example, 15 students over a three-year period [ 18 ] and 365 students over a two-year period [ 7 ]. A variety of peer learning terms and methods were used. These terms included “peer mentoring” [ 19 ], “peer tutoring” [ 7 , 20 – 23 ], “peer coaching” [ 24 ], “inquiry-based learning” [ 25 , 26 ], “problem-based learning” [ 27 – 31 ], and “team learning” [ 32 ].

Of these studies, eight used a qualitative method, six utilized a quantitative method, and four used mixed methods (see Table 2 ). The quantitative studies favoured scaling and rating approaches (e.g., Likert scales), applying valid tools including the Californian Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory [ 28 , 31 ], the Psychological Empowerment Scale [ 30 ], or the Nursing Ethical Discrimination Ability Scale [ 22 ] to collect data. The qualitative studies used a variety of collection methods such as participant observation [ 18 ], focus groups [ 19 , 20 , 25 , 26 , 33 ], individual interviews [ 23 ], and open ended short answer questions [ 27 ]. Combinations of these methods were used by the mixed method studies. In addition a variety of statistics software and applicable inferential statistics were used in the quantitative and mixed method studies, whilst the qualitative studies used applicable thematic approaches to analysis.

The analysis tools and tests used were presented (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , and 5 ) and considered as part of the quality analysis. Whilst quantitative studies give a definitive, measurable result, the use of qualitative studies in this paper examined how the participants felt about a different method of learning and how it impacted on them. These opinions would be important if peer learning was to gain acceptance from the students and peers. Qualitative studies had much smaller participant numbers and whilst larger numbers may have provided a more comprehensive sample, there were saturation and repetition of concepts even with the smaller samples.

Mixed method studies.

Experimental studies with the highest level of evidence, that is, random controlled trials (RCTs), were not a common method of evaluating peer learning as they may not reproduce the true situation in an educational setting [ 34 ].

Eight studies used a comparison group [ 21 , 22 , 27 – 31 , 35 ], and all except two [ 27 , 31 ] were quantitative studies. Valid tools were used by 9 of the 10 quantitative or mixed method studies. It was concluded that valid tools measured what the authors intended, and hence data were an accurate representation of what had occurred and were credible. However, one study [ 21 ] failed to report the number of control and intervention group participants who passed their course. The qualitative studies documented the research process clearly, and the findings were consistent with the data provided. The details in description of the research process and findings varied between studies, whilst within individual studies, sample size, location, and the subjects taught were all potentially limiting; for example, small sample size, specific location, or subject may have caused a bias in the results, hence affecting the transferability of results [ 24 , 31 ]. Publication bias was not evident as the included studies reported both the positive and negative results, for example, using comments from participants [ 26 ] or differences in means [ 35 ].

3.2. Effects of Peer Learning

Peer learning encouraged independent study, critical thinking, and problem solving skills. It could give students a sense of autonomy when they accepted responsibility for their own education. Peer learning was associated with increased levels of knowledge in a number of areas such as problem solving and communication [ 20 , 25 ]. Tiwari et al. [ 31 ] showed that critical thinking was improved in students using PBL ( P = 0.0048) whilst Daley et al. [ 20 ] reported that students showed improvement in cognitive and motor skills. An advantage of peer learning was that both groups learned and benefited from the interaction [ 23 , 24 ]. The benefits differed between the students and peers with the peers gaining experience in communication and leadership, reinforcing their prior learning and discovering what they were capable of achieving in the mentoring/teaching fields [ 19 , 24 ]. On the other hand, students gained confidence and experienced a decrease in anxiety when dealing with certain situations such as clinical placements. PBL was reported to be effective particularly in the theoretical learning component of education whilst peer tutoring, peer coaching, peer mentoring, and the use of role play as a form of peer learning were all effective, both in clinical and theoretical aspects of nursing education.

One negative aspect was related to anxiety levels. Group learning showed an increase in anxiety in both control and intervention groups [ 35 ], whilst other methods such as peer coaching showed a decrease in anxiety in the clinical setting [ 24 ]. The students indicated that having another person assist them decreased their anxiety levels which was pertinent when they were beginning their careers and were uncertain and anxious about what was expected of them [ 18 ]. Informal peer learning also benefited the students by providing them with “survival” skills that are not taught in lectures or text books, which in turn assisted in decreasing anxiety [ 18 ].

In addition to decreasing anxiety [ 24 ], many students showed an increase in satisfaction when peer learning was used [ 22 , 29 ], appreciating having to think for themselves, problem-solve, and work as a team [ 20 , 24 , 27 , 30 ]. The level of satisfaction is higher with peer learning [ 29 ] than the passive CLL method although some students still prefer CLL as it maybe better suited their individual learning style [ 22 ]. Whilst none of the studies in this paper directly investigated the link between course satisfaction and academic results, Higgins [ 21 ] noted a decrease in attrition rate but did not specify student satisfaction levels.

Four studies [ 20 , 23 – 25 ] examined confidence in students when utilizing peer learning. They showed a subjective increase in confidence levels when completing clinical skills, problem solving, and critical thinking. In addition, 11 studies indicated that students appreciated interactive learning sessions and the emphasis on active participation, which encouraged them to take ownership and responsibility for their own learning.

3.3. Utilization

Peer learning was utilized in multiple situations from teaching ethics [ 22 ] and critical thinking [ 31 ] to helping students deal with emotional situations [ 19 ] with patients. In clinical situations peer learning was successful and improved integration into the ward situations [ 18 ] and students' confidence when dealing with actual patients rather than a simulator [ 20 ]. Further, a number of studies identified outcome measures showing an improvement in either an objective or subjective assessment.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this research was to ascertain whether undergraduate nursing students benefit from peer learning. Sixteen of eighteen studies demonstrated positive aspects to peer learning with outcome measures showing improvement in either an objective effect or a subjective assessment (such as a self-rated increase in student confidence). Furthermore, learning from peers was shown to be acceptable to most students. Much of the research into peer learning concentrated on formal peer learning with the evidence supporting the concept that peer learning may be an equally, if not more, effective method of delivering information in undergraduate nursing education.

Peer learning can be utilized to pass information to large groups of students with less faculty member involvement. At a time when there is pressure to train more nurses and minimize costs [ 12 ], peer learning could utilize resources more effectively with students teaching and supervising more junior students, thus decreasing the demand on the responsible faculty members. Therefore it may have cost benefits for managing some aspects of nursing education; however this theory requires further investigation as it was not the focus of any of the papers mentioned in this paper.

Regardless of any decrease in active involvement by lecturers, the need for student supervision remains important. If peers are not knowledgeable or do not have the appropriate skills, then they cannot accurately pass information onto another student. The learning of inaccurate information could potentially cause issues for students when these inaccuracies were demonstrated in exams and on clinical placements. Without supervision, learning may not be effective as shown in an earlier study by Parkin [ 4 ] who found that observation and supervision were required in all peer learning to ensure that correct and current information was being exchanged.

4.1. Advantages and Disadvantages

Peer learning may result in information being more readily accepted by a student as individuals often turn to others who have similar experiences, for advice and guidance. This could decrease anxiety associated with learning due to familiarity of the peer with the student's issues. As noted in the results, anxiety may occur when individuals are exposed to new concepts, whether they are novice or proficient learners [ 36 ]. In prior research [ 37 ], peer learning helped to decrease the student's anxiety and assisted them to fit into a ward situation and feel like part of the team. This sense of belonging has social implications particularly when it is known that learning occurs more effectively when there is socialization [ 38 , 39 ].

Further, social interaction and collaboration between peer and student may have contributed to an increased learning curve and acquisition of further knowledge than would have occurred if students were studying independently. This was illustrated in this paper with students who had been in danger of failing and had received peer tutoring [ 21 ]. They gained additional knowledge and improved their academic result. This method may also allow junior students to problem-solve issues with their patients more independently and care for higher acuity patients, leading to an increase in their self-confidence. This concept was previously reported by Vygotsky [ 40 ], Aston and Molassiotis [ 41 ], and Secomb [ 5 ] who found that peer learning promoted self-confidence in junior students whilst assisting senior students with mentoring and teaching skills. Secomb [ 5 ] also showed that peer learning was an effective learning tool in clinical situations with both nursing and other health professionals. Peers perceived an increase in patient care competence when peer learning was utilized. Secomb [ 5 ] noted, however, that issues such as inappropriate pairing of students and peers should be addressed prior to the intervention.

Student satisfaction may play a part in scholastic achievement through acceptance of an active learning method such as peer learning. Four studies investigating this component [ 22 , 28 – 30 ] discovered that students were satisfied with peer learning as the educational method. This may be because the student takes more responsibility and actively participates in their education, giving them a sense of autonomy. Whilst Ozturk et al. [ 28 ] reported a higher satisfaction level with PBL but no significant difference in academic scores, previous studies have shown a positive association between student satisfaction and grades achieved [ 42 , 43 ].

Peer learning may also be more successful when peers are close in experience or stage of training as it provides a more relaxed, less intimidating, more “user friendly” learning experience than sessions conducted by registered nurses. Prior to the current study, El Ansari and Oskrochi [ 44 ], Eisen [ 45 ], and Secomb [ 5 ] also reported this finding whilst more recently Bensfield et al. [ 46 ] reported that first year students had comfortable learning with more experienced peers.

There is, however, a different perspective. Whilst peer learning has been used for years and might be becoming the norm, students may not be fully familiar with it and therefore be apprehensive about what it offers. Some students reported anxiety and apprehension when taking part in peer learning which was linked to feeling responsible for another's education [ 25 , 26 ], being underprepared [ 23 ] or concerned that their own grades would be negatively affected by group work or dynamics [ 25 , 26 , 32 ]. Further, it was reported that enforcing the educational role of a peer may lead to resentment, particularly if the nurse felt unprepared or unwilling to undertake the role [ 26 ]. Previously Bensfield et al. [ 46 ] showed that whilst nurses have a responsibility to teach others, many are reluctant to do so as they feel unprepared for the role. Due to these issues, students who are familiar and comfortable with CLL may continue to prefer this learning method over peer learning.

4.2. Confusing Terminology Used in Peer Learning

Finally, this paper raises issues around the confusing terminology used to refer to peer learning. As mentioned, multiple terms such as peer teaching, peer mentoring, and peer coaching were used interchangeably with debate about whether they meant the same thing or referred to subtle differences in meaning. A clearer definition of each of the terms is needed to increase the rigor of nursing education research, as was also raised by Secomb [ 5 ], Eisen [ 45 ], and McKenna and French [ 47 ] who found a lack of clarity as to what peer education entailed due to the interchanging of terminology. We suggest amalgamation of some of the terms, for example, team learning and cooperative learning or peer mentoring and peer coaching and having distinct differences in definitions between other terms.

5. Limitations

Some limitations of this study were recognized. Only studies published in English were included. Despite a rigorous search strategy, some relevant articles may have been omitted owing to the search terms used. The mix of study designs and various methods of reporting meant that direct comparison between studies was limited. Some studies were location- or topic-specific, and some studies collected data using indirect outcome measures. However, the collection and review of the diverse papers that were selected offered the best option for determining the overall impact of peer learning in education of nursing students.

6. Conclusion

Peer learning: learning from others who possess a similar level of knowledge, is becoming a part of nursing education. This study showed that undergraduate nursing students could benefit from peer learning, with an increase in confidence and competence and a decrease in anxiety. Their peers also gained skills to prepare them for their role as a registered nurse. Conduct of peer learning within the curriculum was shown to require adequate academic supervision to be effective. It was difficult to ascertain the most effective learning methods because of the inherent variation between study methodologies, terminology, subjects, and settings. Inconsistency terminology was identified as a problem that should be addressed in order to provide clarity in future research.

7. Further Research

Further research is needed to fully investigate peer learning with the use of larger samples, various targeted curricula, courses, and locations to increase the validity of studies. The cost effectiveness of peer learning should be further investigated and compared to that of CLL to ascertain how this option could impact nursing education in terms of resources, time management, and effectiveness.

- 1. Iwasiw CL, Goldenderg D, Andrusyszyn MA. Curriculum Development in Nursing Education. 2nd edition. Boston, Mass, USA: Jones & Bartlett; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Banning M. Approaches to teaching: current opinions and related research. Nurse Education Today. 2005;25(7):502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.03.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Paterson S, Stone R. Educational leadership beyond behaviourism, the lessons we have learnt from art education. Australian Art Education. 2006;29(1):76–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Parkin V. Peer education: the nursing experience. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2006;37(6):257–264. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20061101-04. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Secomb J. A systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(6):703–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01954.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Owens LD, Walden DJ. Peer instruction in the learning laboratory: a strategy to decrease student anxiety. Journal of Nursing Education. 2001;40(8):375–377. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20011101-11. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Goldsmith M, Stewart L, Ferguson L. Peer learning partnership: an innovative strategy to enhance skill acquisition in nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2006;26(2):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.08.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Blowers S, Ramsey P, Merriman C, Grooms J. Patterns of peer tutoring in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education. 2003;42(5):204–211. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20030501-06. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Yuan H, Williams BA, Fan L. A systematic review of selected evidence on developing nursing students’ critical thinking through problem-based learning. Nurse Education Today. 2008;28(6):657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.12.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Neville AJ. Problem-based learning and medical education forty years on: a review of its effects on knowledge and clinical performance. Medical Principles and Practice. 2008;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000163038. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Nestel D, Kidd J. Peer tutoring in patient-centred interviewing skills: experience of a project for first-year students. Medical Teacher. 2003;25(4):398–403. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000136752. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Allan HT, Smith PA, Lorentzon M. Leadership for learning: a literature study of leadership for learning in clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Management. 2008;16(5):545–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00817.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Shipman D, Hooten J. Without enough nurse educators there will be a continual decline in RNs and the quality of nursing care: contending with the faculty shortage. Nurse Education Today. 2008;28(5):521–523. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.03.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Green J. Peer education. Promotion & Education. 2001;8(2):65–68. doi: 10.1177/102538230100800203. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration. 2009. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- 16. The National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Additional Levels of Evidence and Grades for Recommendations for Developers of Guidelines. Stage 2 Consultation. Parkes ACT, Australia: The Australian Government; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Public Health Resource Unit. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Making sense of evidence, 10 questions to help you make sense of reviews. 2006. http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Doc_Links/S.Reviews%20Appraisal%20Tool.pdf .

- 18. Roberts D. Learning in clinical practice: the importance of peers. Nursing Standard. 2008;23(12):35–41. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.11.23.12.35.c6727. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Christiansen A, Bell A. Peer learning partnerships: exploring the experience of pre-registration nursing students. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(5-6):803–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02981.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Daley LK, Menke E, Kirkpatrick B, Sheets D. Partners in practice: a win-win model for clinical education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2008;47(1):30–32. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080101-01. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Higgins B. Relationship between retention and peer tutoring for at-risk students. Journal of Nursing Education. 2004;43(7):319–321. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20040701-01. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Lin CF, Lu MS, Chung CC, Yang CM. A comparison of problem-based learning and conventional teaching in nursing ethics education. Nursing Ethics. 2010;17(3):373–382. doi: 10.1177/0969733009355380. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Loke AY, Chow FLW. Learning partnership-the experience of peer tutoring among nursing students: a qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44(2):237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.028. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Broscious SK, Saunders DJ. Peer coaching. Nurse Educator. 2001;26(5):212–214. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200109000-00009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Horne M, Woodhead K, Morgan L, Smithies L, Megson D, Lyte G. Using enquiry in learning: from vision to reality in higher education. Nurse Education Today. 2007;27(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.03.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Morris D, Turnbull P. Using student nurses as teachers in inquiry-based learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;45(2):136–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02875.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Cooke M, Moyle K. Students’ evaluation of problem-based learning. Nurse Education Today. 2002;22(4):330–339. doi: 10.1054/nedt.2001.0713. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Ozturk C, Muslu GK, Dicle A. A comparison of problem-based and traditional education on nursing students’ critical thinking dispositions. Nurse Education Today. 2008;28(5):627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.10.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Rideout E, England-Oxford V, Brown B, et al. A comparison of problem-based and conventional curricula in nursing education. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2002;7(1):3–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1014534712178. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Siu HM, Spence Laschinger HK, Vingilis E. The effect of problem-based learning on nursing students’ perceptions of empowerment. Journal of Nursing Education. 2005;44(10):459–469. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20051001-04. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Tiwari A, Lai P, So M, Yuen K. A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking. Medical Education. 2006;40(6):547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02481.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Feingold CE, Cobb MD, Hernandez Givens R, Arnold J, Joslin S, Keller JL. Student perceptions of team learning in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education. 2008;47(5):214–222. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080501-03. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Christiansen B, Jensen K. Emotional learning within the framework of nursing education. Nurse Education in Practice. 2008;8(5):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2008.01.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Jolly B. Control and validity in medical educational research. Medical Education. 2001;35(10):920–921. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Hughes LC, Romick P, Sandor MK, et al. Evaluation of an informal peer group experience on baccalaureate nursing students’ emotional well-being and professional socialization. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2003;19(1):38–48. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2003.9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Adams LT. Nursing shortage solutions and America’s economic recovery. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2009;30(6):p. 349. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Benner P. Using the dreyfus model of skill acquisition to describe and interpret skill acquisition and clinical judgment in nursing practice and education. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society. 2004;24(3):188–199. [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Parr JM, Townsend MAR. Environments, processes, and mechanisms in peer learning. International Journal of Educational Research. 2002;37(5):403–423. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Wilkinson IAG. Peer influences on learning: where are they? International Journal of Educational Research. 2002;37(5):395–401. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Vygotsky LS. Biological and Social Factors in Education. Educational Psychology. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: St. Lucie Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Aston L, Molassiotis A. Supervising and supporting student nurses in clinical placements: the peer support initiative. Nurse Education Today. 2003;23(3):202–210. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(02)00215-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Sinclair B, Ferguson K. Integrating simulated teaching/learning strategies in undergraduate nursing education. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship. 2009;6(1):p. 7. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1676. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Casey PM, Magrane D, Lesnick TG. Improved performance and student satisfaction after implementation of a problem-based preclinical obstetrics and gynecology curriculum. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;193(5):1874–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.061. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. El Ansari W, Oskrochi R. What matters most? Predictors of student satisfaction in public health educational courses. Public Health. 2006;120(5):462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.12.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Eisen MJ. Peer-based professional development viewed through the lens of transformative learning. Holistic Nursing Practice. 2001;16(1):30–42. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200110000-00008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Bensfield L, Solari-Twadell PA, Sommer S. The use of peer leadership to teach fundamental nursing skills. Nurse Educator. 2008;33(4):155–158. doi: 10.1097/01.NNE.0000312193.59013.d4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. McKenna L, French J. A step ahead: teaching undergraduate students to be peer teachers. Nurse Education in Practice. 2011;11(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2010.10.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Nestel D, Kidd J. Peer assisted learning in patient-centred interviewing: the impact on student tutors. Medical Teacher. 2005;27(5):439–444. doi: 10.1080/01421590500086813. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Duggan R. A little help from your PALs. Nursing Standard. 2000;14(38):p. 55. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Duchscher JE. Peer learning: a clinical teaching strategy to promote active learning. Nurse Educator. 2001;26(2):59–60. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Dennison S. Peer mentoring: untapped potential. Journal of Nursing Education. 2010;49(6):340–342. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100217-04. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (629.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 18 November 2021

Effect of community-based education on undergraduate nursing students’ skills: a systematic review

- Arezoo Zeydani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5019-7161 1 ,

- Foroozan Atashzadeh-Shoorideh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6144-6001 2 ,

- Fatemeh Abdi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8338-166X 3 ,

- Meimanat Hosseini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3458-0491 4 ,

- Sima Zohari-Anboohi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-9420 5 &

- Victoria Skerrett 6

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 233 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

15 Citations

Metrics details

Community-based education, as an effective approach to strengthen nurses’ skills in response to society’s problems and needs has increased in nursing education programs. The aim of this study was to review the effect of community-based education on nursing students’ skills.

For this systematic review, ProQuest, EMBASE, Scopus, PubMed/ MEDLINE, Cochran Library, Web of Science, CINAHL and Google Scholar were searched up to February 2021. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Seventeen studies were included in this systematic review. Inclusion criteria included articles published in English and were original articles.

In all studies, undergraduate nursing students’ skills were improved by participation in a community-based education program. Community-based education enhances professional skills, communication skills, self-confidence, knowledge and awareness, and critical thinking skills and teamwork skills in undergraduate nursing students.

Conclusions

Community-based education should be used as an effective and practical method of training capable nurses to meet the changing needs of society, to improve nurses ‘skills and empower them to address problems in society.

The main mission of nursing education is to train competent and confident nurses with the knowledge, attitude and skills necessary to maintain and promote community health [ 1 , 2 ]. The main purpose of nursing education is to develop critical thinking, creative thinking, reflective learning, professional skills, time management, self-esteem and effective communication [ 3 ]. However, many nursing graduates do not have advanced skills in communication, creativity, critical and analytical thinking, problem solving, and decision making. Therefore, nurses should be empowered to meet the needs of society [ 1 , 4 ].

It has been proven that traditional teaching methods are not fully effective in improving the cognitive skills and abilities of nursing students [ 5 ], as this method does not address the needs, changes and problems of the society. Challenges such as increase in emerging diseases, increase in chronic diseases, aging population and advances in technology require nurses who not only have advanced knowledge but also have higher thinking skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and decision making [ 6 ]. Nurses have the potential to be a powerful resource for creating a healthy population and promoting economic and social development [ 7 ], and community nurse participation is central to this public health impact [ 8 ].

Several countries follow a community-based education program to cover the role of nurses in public health. Community-based education (CBE) has several definitions, but the core definition refers to learning that takes place in a setting outside the higher education institution. CBE refers to education in which trainees learn and acquire professional competencies in a community setting [ 9 ]. Internationally, changes to education have taken place. For example, the South African government called for a shift in health care education from a traditional content-based approach to a community-based approach so that students and educators could experience it [ 10 ]. UK health policy has emphasized community-based care in recent years because it has been shown to increase nurses’ competence and confidence [ 11 ]. In the United States, community-based education has also had a positive impact on students by improving their skills and increasing their understanding and responsibility [ 12 ]. In Iran, health care systems are changing to address the needs of stakeholders, cost-effective care requirements, quality improvement, and community health improvement [ 13 ].

The role and scope of nursing practice have evolved in response to the changing needs of individuals, communities and health services. The increasing aging of the population, the number of people with chronic conditions, and the emergence of new diseases have necessitated changes in service provision [ 14 ]. The role of health professionals is changing worldwide with the goal of “health for all” through “primary health care“[ 15 ].

Community-based education seems to be a promising approach to improve the relationship between education and the needs of the population. This education can increase students’ skills, as it is based on the philosophy of “primary health care”, Community-based education utilizes the community as a learning environment in which not only students, but also nursing educators, community members, and representatives from other sectors actively participate in the learning experience[ 15 ]. Community-based nursing education programs are necessary to prevent, maintain, and promote community health. At the same time, it promotes personal, social, psychological growth, and increases the skills of innovation, communication and critical thinking development in students as they see the context in which health and illness occur. It provides opportunities for nursing students to learn more about the socioeconomic, political, and cultural aspects of health and illness in society [ 16 ].

Given the importance of the role of nurses in meeting the needs of society and maintaining and promoting community health, it is important to train capable nurses with the necessary skills for society. Community-based education programs in nursing in Iran have received much attention recently [ 14 ], Several studies have been conducted on the effects of community-based education programs on nurses’ skills, but to date there has been no systematic review that comprehensively and separately examines the effects of community-based education on the undergraduate nursing students’ skills. This study comprises a systematic review of research on community-based education for nurses, the findings of which can be used to develop teaching programs. The aim of this review study was therefore to provide an accurate overview of the effect of community-based education on the undergraduate nursing students’ skills.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes (PRISMA) guidelines for the design and conduct of systematic reviews. The following steps were taken: a systematic literature search, organization of documents for review, data extraction and quality assessment of each study, synthesizing data, and writing of the report.

Search strategy

The keywords were “community-based”, “education”, “skills”, “nursing”, and “student”, which were searched individually and in combination with AND/OR (Table 1 ). The systematic literature search was performed in databases such as Scopus, PubMed / MEDLINE, ProQuest, Web of Sciences, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Cochran Library and EMBASE up to February 2021. Inclusion criteria included articles published in English and were original articles. The search terms were obtained from published studies, primary studies and via PubMed MeSH. According to the PICO framework for formulating clinical questions, the queries include four aspects: Patient-Problem (P), Intervention (I), Comparison (C) and Outcome (O). In this regard, Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes, Study Design (PICOS) criteria were used for this study: population (undergraduate nursing students), intervention (community-based education) and outcome (impact on skills).

Study selection

Identified reports were downloaded to a library database. First, the titles and abstracts of the articles and the studies under consideration were reviewed for the match with inclusion criteria. Two authors independently reviewed the full text of the articles and discussed discrepancies until agreement was reached. Study details were extracted from articles and charted in a table which was used to make a decision about study inclusion.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included a focus on nursing students’ skills, community-based education, and publication of articles in English. Due to the limited number of studies involving community-based education interventions, studies using quantitative, qualitative, and combined methods were considered.

Exclusion criteria

Articles relating to hospital education and articles presented at conferences, congresses, or in the form of books and letters to the editor were excluded.

Data extraction

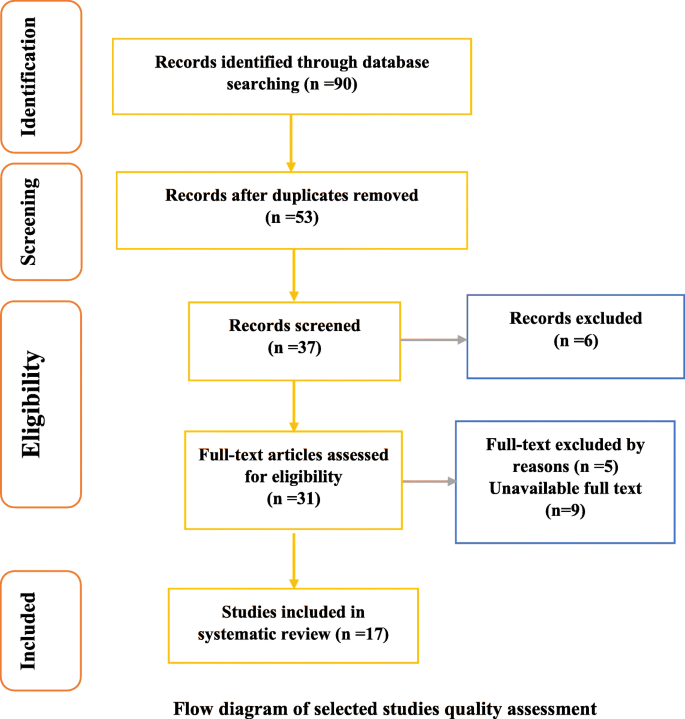

At this stage, 90 potential studies were listed. After 53 duplicates were removed, another researcher reviewed the remaining articles simultaneously and separately. Eleven studies were excluded because the title and content did not match the topic. In addition, nine studies were excluded from the study because access to the full text of the articles was not available. Seventeen articles were included in the analysis.

Quality assessment process

The methodological quality of the included studies assessed independently by two authors using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [ 17 ]. The MMAT was designed to assess various empirical studies in five categories, including qualitative studies, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative-descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies. This instrument consists of 5 items for each category, each of which could be marked as yes, no, or not known. The scoring system provides that the “yes” answer is scored as 1 and all other answers are scored as 0. A higher score indicates higher quality. When evaluating the final scores in terms of quality, scores above half (more than 50 %) were considered high quality [ 18 ] (Table 2 ). Finally, the data were analyzed by extracting the textual content of the articles in the context of the study question.

This systematic review was reported based on the PRISMA guidelines. The flowchart of the studies included in the review is shown in Fig. 1 . Seventeen articles published during 2004-2020 were included: including five quasi-experimental studies, three descriptive studies, four mixed method studies, and five qualitative studies [ 11 , 12 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The total number of participants was 1,866, ranging from 14 to 613 in each study. The procedure for selecting studies using PRISMA diagrams is shown in Fig. 1 .

Flow diagram of selected studies quality assessment

In all quasi-experimental studies, the main intervention was community-based education. Community-based settings in these studies included homes, aid agencies, community sites, clinics, schools, child-care centers, nursing homes (homes for the Aged), addiction treatment centers, care centers for the people with disabilities, dental centers, screening centers, care-centers for the homeless and rural and suburban areas. Studies explores participants were from different countries (United States, Taiwan, Africa, Singapore, United Kingdom, Australia, Indonesia and Iran). In addition, one of the combined studies included a community-based education intervention in a small portion of the study. In this type of study, students’ experiences of community-based education and their skills are examined. Qualitative studies also examined students’ experiences of community-based education.

Effect of community-based education

The quasi-experimental studies in this systematic review had a pretest and a posttest, but only the Nowak study had a control group and the other studies were single-group studies [ 19 ]. Their results were statistically significant ( p <0.05) [ 11 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 31 , 32 ]. In all studies, community-based education affected the skills of undergraduate nursing students. The main findings (Table 3 ) show that community-based education of undergraduate nursing students enhanced professional skills in eight studies. Six undergraduate nursing students participated in the Baglin study and experienced a variety of community-based practice placements. The results of interviews with students led to four topics. These include to students’ basic skills acquisition and practice, the development of their working relationships with educators, patients and others, the learning opportunities offered by practice placement and the effect of such a placements on their confidence to practice [ 11 ]. The Nowak study was a quasi- experimental study using one way RMANOVA. Group mean outcomes measures were compared in three time periods, before to the programs, immediately after the program and in two weeks. Normality of distribution, homogeneity of variance, and random allocation of both groups was established. The disaster preparedness skills scores were measured in both groups. The results of survey showed that a statistically significant skill improvement between the treatment group and control groups ( p <0.05) [ 19 ]. In the Lubber’s study, students assessed their confidence on 16 items. Paired t-tests were performed to compared students’ confidence in their pediatric knowledge and skills as assessed at pre-test and at post-test. When evaluating the full 16-item scale, students’ confidence increased significantly from pre-test (M =2.39, SD =0.65) to post-test (M = 4.13, SD = 0.37), ( p <0.01). Each of the four item sub-scales, knowledge, skills communication, and documentation showed significant increases in students’ confidence from pre-test to post-test. Four additional items of the perceived confidence in pediatric nursing knowledge and skills questionnaire addressed student satisfaction with learning. Student reported a high level of satisfaction (M = 4.36, SD = 0.50) with their simulation experience [ 20 ]. In the Higgins study, students’ oral health knowledge and skills improved after completing the learning unit. The average pretest knowledge score was 66 % and the average posttest score was 86 %. In addition, their perceptions of the importance of building collaborative relationships with dental health providers increased. 99 % of the students strongly agreed that the educational unit was an effective way to learn oral health content. 97 % felt better prepared for interprofessional practice. They described the learning opportunity as useful and stated that their nursing practice would change as a result of their new knowledge [ 22 ]. In the De Villiers study, 61 % of participants reported positive experiences with community-based education and indicating that the program was effective in improving their skills [ 24 ]. In the Mwanika study, the qualitative results from the focus group discussions are presented under major themes namely: management and coordination of community-based education and service educational program, community-based education and service contribution to development of confidence and competence as health workers, professionalism and teamwork, willingness to work in rural health facilities and practice of primary health care. In addition, the quantitative findings in the Mwanika study showed that community-based education and service impact on the student with respect to development of confidence, professionalism, sense of responsibility, willingness to work in rural areas and primary health care skills [ 27 ]. Findings from the Peters study interview were presented on four topics: autonomy in practice, working with highly skilled nurses, focusing on holistic care and showing genuine interest in educating students [ 31 ]. The Stricklin study found that student nurses perceived that they were able to achieve learning outcomes and competency in the maost of psychiatric mental health nursing skills through experiences provided in community-based clinical settings. Three themes emerged from the data: meeting the challenges of developing psychiatric mental health nursing skills, sharing multiple experiences of competency, and empowering all nurses through psychiatric mental health nursing skills [ 32 ].

In nine studies, community-based education improved communication skills with educators, patients, community members, children, adolescents, the elderly, people with disabilities, family, patient relatives, and other health professionals [ 11 , 12 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 33 ]. Nine studies mentioned increasing self-confidence [ 11 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 32 ] and five studies mentioned increasing knowledge and awareness [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 28 ]. Promoting teamwork skills was mentioned in four studies [ 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 ] and improving thinking skills through education was mentioned in three studies [ 11 , 23 , 25 ]. The content of the community-based curriculum and the strategy for its implementation varied across studies, but all studies were conducted in community-based settings. Educational programs included community-based learning projects, community-based simulated experiences, community-based pilot programs, and courses in clinical settings.

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the impact of community-based education on the undergraduate nursing students’ skills. After reviewing 17 selected articles from the United States (7 articles), United Kingdom (2 articles), Australia (2 articles), Africa (2 articles), Taiwan (1 article), Singapore (1 article), Indonesia (1 article), and Iran (1 article), the findings were summarized in relation to the impact of community-based education on nurses’ skills. Community-based education can be said to be as one of the most effective educational methods for improving the skills of undergraduate nursing students. The results of the present study were compared with those of other studies.

The findings of this systematic review indicate that community-based education promotes the development of professional skills in nursing students [ 11 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 31 , 32 ]. Research has shown that the use of community experiences in educational programs enhances professional skills [ 10 ]. Community-based education develops occupational competencies and skills such as problem-solving, leadership, and management [ 9 ]. In addition, community learning experiences promote competencies needed by students [ 15 ]. The findings of the present study are consistent with other studies [ 11 , 24 , 34 , 35 ].

Students in a community-based curriculum are exposed to a variety of challenging situations, such as home visits, school visits, visiting and caring for people with disabilities, and interacting with diverse people. Therefore, they develop their skills in dealing with diverse populations [ 36 ]. Students acquire the ability to identify health problems in the community, work with available resources in the community, and provide care that is appropriate to the context and culture of the community [ 34 ].

The results of this systematic review also indicate that community-based education was rated as useful by faculty, students, and clients. Providing community health services to work with students in the real context of society and among people increases their personal skills and abilities, including improving their communication skills with professors, instructors and the community [ 11 , 12 , 19 , 20 , 25 , 27 , 33 ]. The results of many studies are consistent with the findings of the present study [ 2 , 9 , 11 , 15 , 24 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Community-based education strengthens students’ communication skills when interacting with professionals and the community with clients and professionals. Communication skills and interpersonal relationships are important skills that are considered essential in order to practice an effective and efficient profession in society. In this program, students progressively develop their communication skills [ 9 ]. Communication and negotiation skills are necessary to build relationships in the community, to work effectively with the physician and other members of the medical team, and to educate patients. This high level of communication skills is the focus of these programs [ 40 ].

The results of the present systematic review suggest the use of community-based teaching enhances the confidence of undergraduate nursing students. Researchers found that engaging nursing students in the community and confronting their problems increased students’ confidence in caring for people in the community [ 11 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 32 ]. The findings of the present study are consistent with the findings of other studies. For example, in a study in South Africa and Uganda, a large percentage of nursing students reported that practicing skills in real-life communities increased their confidence [ 9 , 24 ]. These findings have also been confirmed in other studies [ 11 , 41 , 42 , 43 ], for example, that increasing the level of skills, awareness, and community involvement, working in interdisciplinary teams, and being self-reliant in this educational program increases students’ self-confidence [ 9 ].

The results of this systematic review have shown that community-based education is an effective way to raise awareness and provide necessary experiences for nursing students [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 28 ]. Being in the community greatly increases nursing students’ knowledge and understanding of the impact of health conditions on the population. As nursing students provide care to vulnerable groups, they gain many experiences interacting with diverse populations, which deepen their knowledge and awareness. Findings from other studies support the findings of the present study [ 9 , 15 , 24 , 39 , 40 ]. A community-based curriculum exposes nursing students to the impact of living conditions and other realities where students can relate theory to the real world. This makes learning more meaningful and strengthens their experiences and knowledge. Students become more aware of social problems and inequalities in health care and other factors that affect health [ 34 ].

Similar to other studies, the results of the present systematic review showed that community-based education improved teamwork skills in nursing students [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 ]. Nursing students considered this training program to be successful, and felt that it enhanced their group activities and teamwork skills. The results of other studies were consistent with the findings of the present study [ 15 , 38 ]. Nursing students often have limited opportunities on campus or in the clinic to participate in teamwork. The scope of community-based sites may provide students with opportunities to learn group work and inter-professional work so that students learn how to work effectively and efficiently in a professional team [ 35 ].

This systematic review shows that community-based education creates a real and interactive learning environment, and that students develop critical thinking skills during instructor-led activities [ 12 , 23 , 25 ]. community-based education has been shown to promote critical thinking in nursing students because of its characteristics, such as the emphasis on the learner exploration of problems and the use of evidence in problem solving [ 9 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. In this way, students interpret their diverse experiences based on what they encounter, hear, read and see [ 9 ].

Community-based education provides an opportunity for students to apply their theory and knowledge in a real and practical environment. Community-based education increases their self-confidence and satisfaction [ 20 ] and all students with different nursing roles ( Clinic nurse, school nurse, home care nurse, district nurse) get acquainted and gain different experiences, while those who are in one place are able to gain less experience [ 21 ]. As a result, students understand the importance of the program and make changes in their performance [ 22 ]. During the community-based training program, students receive feedback and reflection as well as work with different teams. This allows them to reflect and develop their critical thinking skills, communication skills and teamwork skills [ 23 ].

The studies presented had limitations. The quasi-experimental studies used convenience samples, and only one of them had a control group, and it is not certain whether the difference between pre-test and post-test was solely due to the training course. However, the validity and reliability of the questionnaires used in the studies were found to be high [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Limitations

In this systematic review there were restrictions on access to the original articles due to the sanctions in Iran, for example, access to the full text of 9 articles was not possible. Considering the findings and the positive impact of community-based education on undergraduate education, it is suggested that community-based education in clinical education in hospitals and clinics should also be reviewed.

In community-based education, students are confronted with the real life problems in the context of society. This enables them to deal with problems and gradually develops vocational skills, communication skills, critical thinking and teamwork skills. In addition, this type of education strengthens the learning process of students and leads them to gain experience and sound knowledge about health issues in the community, while increasing their self-confidence. According to the findings of the studies reviewed in this review on the effectiveness of community-based education on the undergraduate nursing students’ skills, community-based education can be used as an effective pedagogical approach in curriculum and program development. Since community-based education is an approach that has recently received special attention, it is clearly necessary to conduct community-based studies with appropriate methodology and stronger evidence to confirm the findings of the present study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Bahramnezhad F, Shahbazi B, Asgari P, Keshmiri F. Comparative study of the undergraduate nursing curricula among nursing schools of McMaster university of Canada, Hacettepe university of Turkey, and Tehran university of Iran. SDME. 2019;16(1):1–9.

Google Scholar

Edwards JB, Alley NM. Transition to community-based nursing curriculum: processes and outcomes. J Prof Nurs. 2002;18(2):78–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cheng SF, Kuo CL, Lin KC, Lee Hsieh J. Development and preliminary testing of a self-rating instrument to measure self-directed learning ability of nursing students. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(9):1152–8.

Thabet M, Taha E, Abood SA, Morsy SR. The effect of problem-based learning on nursing students’ decision making skills and styles. JNEP. 2017;7(6):108–16.

Article Google Scholar

Hsiao H-C, Chang J-C. A quasi-experimental study researching how a problem-solving teaching strategy impacts on learning outcomes for engineering students. World Trans Eng Technol Educ. 2003;2(3):391–4.

Temel S. The effects of problem-based learning on pre-service teachers’ critical thinking dispositions and perceptions of problem-solving ability. S Afr J Educ. 2014;34(1):1–20.

Kang S, Ho TTT, Nguyen TAP. Capacity development in an undergraduate nursing program in Vietnam. Front Public Health. 2018;6(146):1–8.

George CL, Wood-Kanupka J, Oriel KN. Impact of participation in community-based research among undergraduate and graduate students. J Allied Health. 2017;46(1):15E-24E.

Kaye DK, Muhwezi WW, Kasozi AN, Kijjambu S, Mbalinda SN, Okullo I, et al. Lessons learnt from comprehensive evaluation of community-based education in Uganda: a proposal for an ideal model community-based education for health professional training institutions. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):1–9.

Mtshali NG, Gwele NS. Community-based nursing education in South Africa: a grounded-middle range theory. JNEP. 2016;6(2):55–67.

Baglin M, Rugg S. Student nurses’ experiences of community-based practice placement learning: a qualitative exploration. Nurse Educ Pract. 2010;10(3):144–52.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ibrahim M. The use of community based learning in educating college students in Midwestern USA. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2010;2(2):392–6.

Mtshali N. Implementing community-based education in basic nursing education programs in South Africa. Curationis. 2009;32(1):25–32.

Randall S, Crawford T, Currie J, River J, Betihavas V. Impact of community based nurse-led clinics on patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, patient access and cost effectiveness: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;73:24–33.

Uys L, Gwele N. Curriculum development in nursing: Process and innovation. New Yok: Routledge; 2005.

Linda NS, Mtshali NG, Engelbrecht C. Lived experiences of a community regarding its involvement in a university community-based education programme. Curationis. 2013;36(1):1–13.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration Copyright. 2018;1148552:1–10.

Nowak M, Fitzpatrick J, Schmidt C, DeRanieri J. Community partnerships: teaching volunteerism, emergency preparedness and awarding Red Cross certificates in nursing school curricula. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2015;174:331–7.

Lubbers J, Rossman C. The effects of pediatric community simulation experience on the self-confidence and satisfaction of baccalaureate nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;39:93–8.

Lubbers J, Rossman C. Satisfaction and self-confidence with nursing clinical simulation: novice learners, medium-fidelity, and community settings. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;48:140–4.

Higgins K, Hawkins J, Horvath E. Improving oral health: integrating oral health content in advanced practice registered nurse education. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(5):394–7.

Cheng YC, Huang LC, Yang CH, Chang HC. Experiential learning program to strengthen self-reflection and critical thinking in freshmen nursing students during COVID-19: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5442.

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Villiers J, Joubert A, Bester C. Evaluation of clinical teaching and professional development in a problem and community-based nursing module. Curationis. 2004;27(1):82–93.

Wee LE, Yeo WX, Tay CM, Lee JJ, Koh GC. The pedagogical value of a student-run community-based experiential learning project: the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Public Health Screening. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2010;39(9):686–91.

Street KN, Eaton N, Clarke B, Ellis M, Young PM, Hunt L, et al. Child disability case studies: an interprofessional learning opportunity for medical students and paediatric nursing students. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):771–80.

Mwanika A, Okullo I, Kaye DK, Muhwezi W, Atuyambe L, Nabirye RC, et al. Perception and valuations of community-based education and service by alumni at Makerere university college of health sciences. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(1):1–8.

Parry YK, Hill P, Horsfall S. Assessing levels of student nurse learning in community based health placement with vulnerable families: knowledge development for future clinical practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;32:14–20.

Lestari E, Scherpbier A, Stalmeijer R. Stimulating students’ interprofessional teamwork skills through community-based education: a mixed methods evaluation. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1143–54.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bassi S. Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of service-learning through a school-based community project. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(3):162–7.

Peters K, McInnes S, Halcomb E. Nursing students’ experiences of clinical placement in community settings: a qualitative study. Collegian. 2015;22(2):175–81.

Stricklin SM. Achieving clinical competencies through community-based clinical experiences. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(4):291–301.

Fereidouni Z, Hatami M, Jeihooni AK, Kashfi H. Attitudes toward community-based training and internship of nursing students and professors: a qualitative study. Invest Educ Enferm. 2017;35(2):243–51.

Mtshali G. Conceptualisation of community-based basic nursing education in South Africa: a grounded theory analysis. Curationis. 2005;28(2):5–12.

Stubbs C, Schorn MN, Leavell JP, Espiritu EW, Davis G, Gentry CK, et al. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(5):652–5.

Zotti ME, Brown P, Stotts RC. Community-based nursing versus community health nursing: what does it all mean? Nurs Outlook. 1996;44(5):211–7.

Feenstra C, Gordon B, Hansen D, Zandee G. Managing community and neighborhood partnerships in a community-based nursing curriculum. J Prof Nurs. 2006;22(4):236–41.

Fichardt A, Viljoen M, Botma Y, Du Rand P. Adapting to and implementing a problem-and community-based approach to nursing education. Curationis. 2000;23(3):86–92.

Steffy ML. Community health learning experiences that influence RN to BSN students interests in community/public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2019;36(6):863–71.

Claramita M, Setiawati EP, Kristina TN, Emilia O, van der Vleuten C. Community-based educational design for undergraduate medical education: a grounded theory study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):258.

Howe A. Twelve tips for community-based medical education. Med Teach. 2002;24(1):9–12.

Daniels ZM, VanLeit BJ, Skipper BJ, Sanders ML, Rhyne RL. Factors in recruiting and retaining health professionals for rural practice. J Rural Health. 2007;23(1):62–71.

Lehmann U, Dieleman M, Martineau T. Staffing remote rural areas in middle-and low-income countries: a literature review of attraction and retention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):1–10.

Magzoub MEM, Schmidt HG. A taxonomy of community-based medical education. Acad Med. 2000;75(7):699–707.

Andrus NC, Bennett NM. Developing an interdisciplinary, community-based education program for health professions students: the Rochester experience. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):326–31.

Schmidt H, Magzoub M, Feletti G, Nooman Z, Vluggen P. Handbook of community-based education: theory and practices. The Netherlands: Network Publications; 2000.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Vice Chancellor for Research of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and all those who helped us with our research. The authors would like to thank Mrs. Victoria Skerrett who helped with the native language translation.

‘Not applicable’.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Arezoo Zeydani

Department of Psychiatric Nursing and Management, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Labbafinezhad Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Foroozan Atashzadeh-Shoorideh

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran

Fatemeh Abdi

Department of Community Health Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Meimanat Hosseini

Department of Medical Surgical-Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Sima Zohari-Anboohi

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK

Victoria Skerrett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception & Design; AZ, FAS, FA, MH, SZA, VS. Data analysis: AZ, FAS, FA, MH, SZA, VS. Interpretation of data; AZ, FAS, FA, VS. Draft and revising work AZ, FAS, FA, MH, SZA, VS. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Foroozan Atashzadeh-Shoorideh .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors had no conflict of interest in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zeydani, A., Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F., Abdi, F. et al. Effect of community-based education on undergraduate nursing students’ skills: a systematic review. BMC Nurs 20 , 233 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00755-4

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2021

Accepted : 03 November 2021

Published : 18 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00755-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community-based

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO