Labor Exploitation: Case Study of Top Glove

By londra ademaj.

This case study examines the allegations of forced labor in the manufacturing process of gloves by Top Glove, a prominent Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer. Malaysia, a diverse Southeast Asian country situated on the Malay Peninsula, serves as the home of this multinational corporation. Founded in 1991 by Tan Sri Dr. Lim Wee Chai in Malaysia, Top Glove Corporation Bhd has emerged as the global leader in rubber glove manufacturing, making a profound impact on the industry. Starting as a small local enterprise with just one factory and a single glove production line, Top Glove has experienced rapid expansion, solidifying its position as a global leader in the glove manufacturing industry (Top Glove). The case study explores the factors behind Top Glove’s success, examines the labor exploitation allegations that tarnished its reputation, considers the ethics regarding worker treatment, and details the responsibilities of corporations and governments.

Unravelling Top Glove’s Path to a Distinguished Status

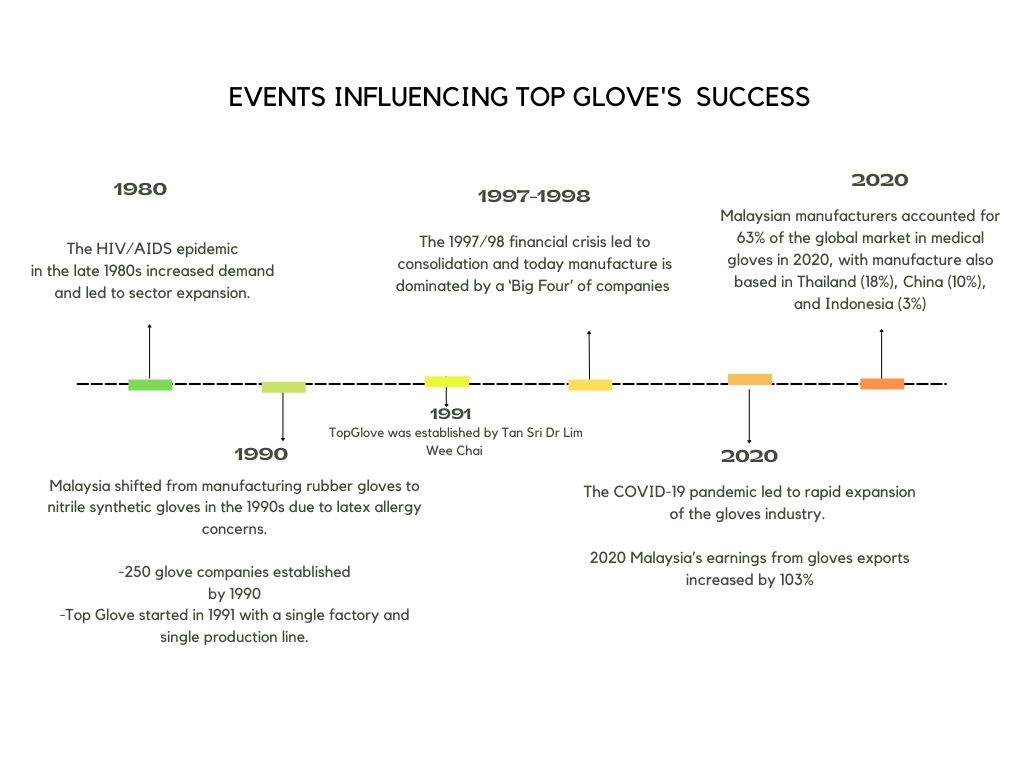

Figure 1 – Data sourced from (Hughes et al.)

The growth of multinational corporations like Top Glove in the rubber glove industry is heavily influenced by the contextual factors at play. The diagram presented below serves as a visual representation of the pivotal events that have played a significant role in contributing to its global success [Figure 1].

Remarkably, the expansion of Top Glove can be traced back to a series of unforeseen events, which carried both positive and negative consequences for the company. Although these events may not have been favorable for the overall economy, they played a pivotal role in propelling Top Glove’s ascent into the realm of a multinational corporation:

- In 1980, the demand for rubber gloves surged due to the HIV and AIDS epidemic. However, Top Glove was not established until 11 years later when regulatory changes mandated the transition from latex to synthetic nitrile gloves to address latex allergies. This move placed Top Glove in a highly competitive market, with approximately 250 other glove companies already operating by 1990 (Hughes et al.) Product differentiation was minimal, and competition was fierce.

- The Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 brought about an unexpected shift in the industry. Glove manufacturers collaborated, resulting in the formation of an oligopoly market where a few dominant players, known as the “big four,” controlled the industry (Hughes et al.). Since this development, the demand for gloves has remained stable over time due to their essential nature in hospitals and healthcare settings. This inelastic demand has provided a foundation for Top Glove’s continued expansion. This market structure presented an opportunity for Top Glove to consolidate its position and experience growth on an international scale.

- Since the Asian financial crisis, the COVID pandemic emerged as the next significant global event. The growth during the pandemic was significant, prompting Top Glove to expand its product line by manufacturing face masks. In 2020, Malaysian manufacturers, including Top Glove, captured a substantial 63% share of the global medical glove market, truly cementing their international presence. (Hughes et al.).

While the journey of Top Glove in the glove industry may seem remarkable, it is important to critically assess the factors that have contributed to its growth. Regulatory changes, financial crises, and the recent pandemic have all played a role in shaping Top Glove’s fortunes. The company has capitalized on market opportunities and adapted to changing circumstances. Yet, there exists broader implications, including the potential for labour exploitation to occur.

Labor exploitation can be challenging to define precisely. Marxists view exploitation as the unequal exchange of labor for goods (Roemer 30–65), while Adam Smith argues that it stems from the private property system, making worker justice unattainable under capitalism, particularly with profit-driven multinational corporations (Fairlamb 193–223). In the context of this case study, labor exploitation contains an element of criminal offences of forced labor or human trafficking which themselves constitute modern slavery.

Behind The Scenes: Top Glove

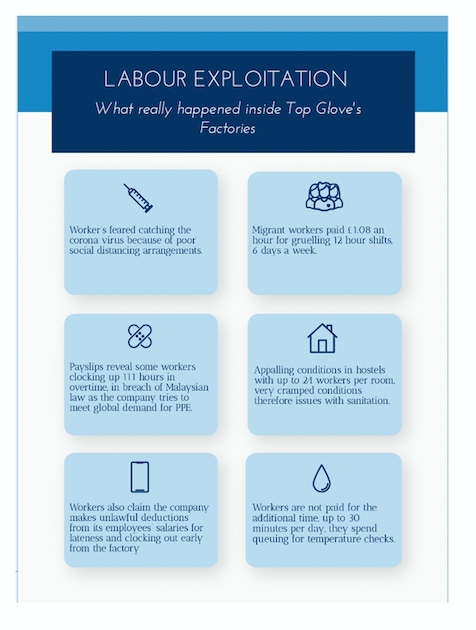

Top Glove has faced significant criticism and scrutiny regarding its labor practices. In 2020, the company came under the spotlight for alleged labor exploitation and poor working conditions (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre). Reports revealed mistreatment of migrant workers, excessive overtime, low wages, cramped living quarters, and other labor rights violations. These revelations raised concerns about the ethical practices and social responsibility of Top Glove, leading to international backlash and investigations by various organizations and authorities.

The allegations first emerged in 2018 through the diligent efforts of investigative journalists. The British Department of Health treated these accusations with utmost seriousness, recognizing the immediate need for further investigations (Marmo and Bandiera). As the investigations progressed, the shocking reality of illicit and inhumane practices resembling modern-day slavery became apparent. Top Glove, a prominent industry player, found itself implicated in a range of exploitative activities, including debt bondage, and forced labour (Marmo and Bandiera). For a more comprehensive understanding of the specific incidents that unfolded within the Top Glove factories, please refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2- Data Sourced from Marmo and Bandiera

Understanding the Roots of Labor Exploitation

Top Glove, Hartalega, and Kossan, the major Malaysian players in this industry, collectively employ nearly 34,000 workers (Zaugg). A significant proportion of these workers are recruited from abroad, primarily from countries like Indonesia, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar. This recruitment pattern is driven by the limited job opportunities available in their home countries, further intensifying their dependence on securing a job within these renowned Malaysian manufacturing companies.

The dependence on specific factories for employment creates an unjust power imbalance between employers and workers, leading to a range of adverse consequences. Employers are aware of the desperate need for jobs among workers, leaving the latter susceptible to exploitation. In their fear of unemployment and with limited options , workers may be compelled to accept unfavorable conditions such as low wages, long working hours, and inadequate safety measures. This power asymmetry perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage and erodes workers’ rights and well-being . Low wages not only impede their ability to meet basic needs but also hinder social mobility and trap them in a cycle of poverty. At the same time, workers are frequently subjected to long working hours without sufficient rest or breaks, leading to physical and mental exhaustion. This unfortunate outcome compromises their health and overall well-being.

Moreover, the absence of proper safety measures within these factories exposes workers to a multitude of significant risks and hazards inherent in the glove manufacturing process. Accidental exposure to toxins is a grave concern, as workers may come into contact with harmful chemicals and allergens during various stages of production (Boersma). Due to a lack of proper training and limited access to personal protective equipment (PPE), workers are exposed to the risk of developing occupational illnesses and enduring long-term health consequences. The improper handling of chemicals without adequate precautions can lead to immediate injuries, such as burns or skin irritations. The manufacturing industry for latex gloves is known to carry a high level of risk due to the presence of carcinogens, acids, strong alkalis, and dangerous drugs, posing significant health hazards (Yari et al.).

The lack of resources became apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic when groups of workers contracted the virus. Despite engaging in a global effort to supply protective equipment for the coronavirus, the company experienced a troubling situation. While enjoying record profits from shipping gloves worldwide, critics argue the company’s low-paid workers in Malaysia faced a severe outbreak of Covid-19 due to inadequate protections provided by the company(Beech).

Furthermore, the rubber glove industry operates under an oligopoly market structure, exacerbating the problem of exploitation. In the Malaysian market, Top Glove reigns as the dominant force, holding an impressive 26% share of the world market (Top Glove), ironically, keeping their position at the “top”. During the pandemic, the market control of Top Glove was further intensified as there was a significant increase in global demand. To meet production targets, labour had to operate beyond maximum capacity.

Making the situation worse, Top Glove introduced a scheme called “Heroes for COVID-19,” where workers were requested to voluntarily work up to 4 additional hours on their day off to package gloves. However, this scheme has been criticized for bypassing labor regulations and coercing workers into working 7 days a week (Marmo and Bandiera). The intention was to portray these workers as heroes for those hospitalized by COVID-19, but in reality, it was merely a ploy to lure in workers. The harsh reality is that over 5,000 Top Glove workers tested positive for COVID-19, and tragically, one worker lost their life, making Top Glove facilities responsible for Malaysia’s largest cluster of COVID-19 cases(Marmo and Bandiera).

Labor exploitation allegations predate the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating that it was not solely caused by the health crisis. However, the pandemic acted as a catalyst, making labor exploitation more noticeable and drawing attention to the issue. It is important to understand that labor exploitation may have been an ongoing problem before the pandemic, extending beyond its time frame. Top Glove’s dominant position in the industry often leads to cost-cutting measures, including the minimization of labor costs. Unfortunately, this strategy results in the exploitation of workers to maintain competitive pricing and maximize profits. Surprisingly, despite its monopoly power, Top Glove’s operating profit margin of 12.3% indicates inefficiencies in operating costs. These relatively small profit margins may directly contribute to labor exploitation, particularly when compared to competitors like Riverstone Holdings Limited, which enjoys a higher operating profit margin of 39.3% (Gek).

Exploring the Factors that Keep Workers in Harsh Conditions

Migrant workers are issued with a Visit Pass Temporary Employment (VP TE) for Malaysia. The VP TE enables a stay of 12 months after which it must be renewed if the worker remains in employment. Unfortunately, the Immigration Regulations prohibit a change of employer or employment, meaning a migrant worker’s VP TE is tied to a single employer and workers are unable to move elsewhere (Hughes et al). This means labor is de facto [la1] immobile, and individuals cannot work elsewhere unless in illicit forms of employment.

As the reliance on foreign labor has increased, there has been a corresponding rise in concerns regarding working and living conditions faced by workers. Consider the labor laws and regulations in Malaysia, Thailand, China, and Vietnam, where these manufacturing facilities are located. While these countries have labor laws in place to protect workers’ rights, the effectiveness of implementation and enforcement can vary. Large corporations, including glove manufacturers, may take advantage of loopholes and weaknesses in the system, exploiting leeway’s in laws and regulations. Additionally, inadequate labor inspection systems and limited regulatory oversight further compound the issue. Notably, Malaysian law allows for working hours that exceed the widely accepted maximum of 60 hours per week and permits work on designated rest days (Lee et al.). This highlights how labor exploitation is more likely to occur when labor laws are inadequate or lacking in their protective measures.

Global Impact of Labor Exploitation

As investigations delved deeper into working conditions within the factories, the impact of these extends far beyond national borders, making waves in the international trading market. In response to the distressing revelations, many countries took swift action by imposing bans on Malaysia’s exports of medical gloves, starting with the USA in 2020.

This sudden shift cast Malaysia as the focal point of forced labor issues, attracting attention and concern from around the globe. Rosey Hurst, and the founder of Impactt, a London-based ethical trade consultancy, succinctly expressed, “Malaysia has become the poster child” for these pressing labor concerns (Lee et al.).

The ban on US imports on July 2020 was triggered by a tragic incident at Top Glove, where an employee succumbed to Covid-19. The virus rapidly spread throughout the company’s factories and worker dormitories, leading Malaysian authorities to describe the conditions as overcrowded, uncomfortable, and lacking proper ventilation. Subsequent measures were implemented to contain the outbreak (Palma). As a result, the US Customs and Border Protection took decisive action by ordering the seizure of Top Glove’s products upon arrival at American ports, citing allegations of forced labor. The consequences of such a reputation are not confined to public perception but also manifest in tangible economic damage. This development had a significant impact on the reputation of one of the world’s largest corporate beneficiaries during the pandemic (Palma). It contributed to double-digit declines in revenue and net profit. Revenue and profit fell 22% and 29% respectively (Kumar). It is a stark reminder of how labor exploitation can have profound and far-reaching implications, impacting not just individuals but also international trade dynamics (Lee et al.)

Around the time the ban was introduced, Top Glove released a press statement firmly denying all allegations and emphasizing their unwavering dedication to labor governance. In their official communication, the company asserted (Alam):

- “Top Glove’s workers do not perform excessive overtime and are given rest day in line with the Malaysia labor law requirement, which is 104 hours of overtime per month and one (1) rest day per week, respectively. “

- “Maximum allowable overtime is 4 hours per working day and solely on a voluntary basis.”

- “To ensure compliance with Malaysian labor law requirements, Top Glove has implemented a digital monitoring exercise.”

Just a few months after the press release, there came a significant development as the United States decided to lift the import ban on Malaysia’s Top Glove. As a testament to their ongoing efforts, Top Glove published a comprehensive improvement report, detailing the actions taken since the allegations surfaced, despite consistently refuting any involvement in exploitative practices. In this report, they highlighted significant improvements in several areas, including (Top Glove):

1.Fair Recruitment Practices of Foreign Workers 2. Continuous Improvement of Workers’ Accommodation 3. Fair Working and Wages of Workers 4. Continued Safety and Health of Our Workforce 5. More Stringent Safety Measures to Safeguard Our Workforce Post COVID 19

Not only did Top Glove make information about its standards available, but other leading companies also contributed by sharing their assessments. Amfori, a prominent global business association focused on open and sustainable trade, recently conducted a social audit of Top Glove. In this assessment, Top Glove was proudly awarded an ‘A’ rating, signifying their dedication to upholding exemplary social standards. This recognition from Amfori highlights Top Glove’s commitment to transparency and responsible business practices (Jaafar).

Top Glove’s ‘A’ rating was the outcome of a comprehensive social audit conducted from June 23 to 26. The audit results reflected 12 areas assessed as “very good ” and one area as “good,” showcasing some improvements. It is worth noting that Top Glove engaged with various organizations to enhance its social compliance and performance (Jaafar).

Because of these improvements, the bans on Top Glove’s products were lifted, causing an initial boost in the market. Top Glove shares rose by as much as 10% during early trading, although they later experienced a decline. With the ban lifted, Top Glove can now proceed with their previously disrupted plan of a $1 billion dual listing in Hong Kong, which was postponed due to the import ban (Ruehl and Langley).

Bengtsen argues that the import ban on Top Glove achieved what decades of voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts by the global medical sector and actions by Malaysia’s labor inspectorate failed to accomplish. He suggests that the ban’s effectiveness was due to its direct impact on the company’s revenues, making it a crucial aspect to consider (Fanou).

These unfolding events give rise to critical questions regarding accountability and necessitate an examination of potential challenges within Malaysia. It raises the question of whether the responsibility should solely rest on Top Glove as a multinational corporation or if there is a larger systemic issue at play. The absence of appropriate legislation and the presence of exploitative practices indicate the need to scrutinize the wider labor landscape and regulatory framework within Malaysia (Palma).

The initial lack of response from Malaysia’s labor department regarding potential changes to the country’s labor laws, and the trade ministry’s silence on inquiries about potential investment losses, raises concerns about addressing labor rights issues (Lee et al.). However, as time progressed, the labor department in Malaysia has charged Top Glove with 10 counts of failing to provide worker accommodation that meets the minimum standards of the labor department in 2021. (Lee) Despite this, an independent consultant, Impactt, said it “no longer” found any indication of systemic forced labor at Top Glove, which was making progress on some indicators, such as living conditions (Lee).

These observations emphasize the need for greater attention and efforts from both multinational corporations and government bodies involved in the industry to address and mitigate labor exploitation.

It calls for a deeper understanding of the challenges that allow labor exploitation to persist and raises the urgency to address them to ensure the well-being and dignity of workers for a more equitable and just society.

Ethics Evaluation

The emergence and growth of Top Glove, coupled with the allegations of labor exploitation, raise intricate ethical considerations that demand in-depth examination. The treatment of workers within the company’s operations reveals a troubling disregard for their fundamental rights and well-being.

One of the fundamental ethical considerations centers around the principle of human dignity. Human dignity is crucial as it forms the foundation for justifying and upholding human rights .

At its core, the concept of human dignity asserts that every individual possesses inherent worth and value solely by virtue of being human. This belief is reflected in Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which proclaims that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” (Soken-Huberty)

The idea of human rights is as simple as it is powerful: that people have a right to be treated with dignity. Human rights are inherent in all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status (Heard).

The alleged mistreatment of workers, including excessive working hours, low wages, and inadequate living conditions, violates their inherent dignity as individuals. Such practices strip workers of their basic rights, compromise their physical and mental well-being, and perpetuate a cycle of exploitation. Upholding the principle of human dignity is crucial in ensuring fair and equitable treatment of all individuals within the workforce.

Transparency and accountability are also critical ethical dimensions. Corporations like Top Glove have a moral obligation to operate transparently and be held accountable for their actions. The alleged labor exploitation within the company brings to light concerns regarding corporate responsibility, corporate governance, and supply chain management. Holding corporations accountable for their actions is crucial in fostering a culture of ethical behavior and ensuring labor rights are upheld.

Today, human rights have taken on a profound significance, akin to a form of religion. They serve as a powerful moral compass, guiding us in evaluating how a government treats its people (Heard). When it comes to addressing the ethical concerns surrounding labor exploitation, a multifaceted approach becomes crucial.

The approach entails a commitment from corporations to prioritize the well-being and rights of workers, regulatory bodies to enforce and strengthen labor standards, and society at large to raise awareness and demand ethical practices. By fostering a culture of ethics and social responsibility within the industry, it becomes possible to create a labor environment that upholds the dignity and rights of all workers.

The United Nations’ “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” framework serves as a global standard for preventing and addressing the potential negative impact on human rights associated with business activities (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights). This framework consists of three pillars:

- The duty of the state to protect human rights.

- The responsibility of corporations to respect human rights.

- The necessity for enhanced access to remedies for victims of human rights abuses linked to business practices.

While international human rights treaties generally do not impose direct legal obligations on businesses, the International Bill of Human Rights, and the core conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) provide fundamental guidelines for businesses to comprehend the essence of human rights, how their own operations may influence them, and how to ensure proactive measures are in place to prevent or mitigate potential adverse impacts (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights).

While recognizing challenges in ensuring strong protections for human rights and labor rights in Malaysia, significant efforts have been made to improve the situation.

For instance, the Bureau of International Labour Affairs collaborated with the Malaysian government on projects aimed at enhancing labor rights and enforcement. These initiatives have included assisting the national government in drafting laws, decrees, and regulations to strengthen labor protections. Efforts have also been focused on providing information and guidance to employers regarding these regulations, promoting compliance and awareness (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Additionally, there have been endeavors to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of labor administration in Malaysia. This involves initiatives such as strengthening labor inspections to ensure that legal instruments are enforced. The labor ministry or relevant authorities play a key role in overseeing and conducting these inspections (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Mechanisms for resolving labor disputes have been established to provide workers in Malaysia with accessible avenues to seek justice and find resolution in case of rights violations. These measures aim to ensure that workers’ rights are upheld and protected in the country (Bureau of International Labour Affairs).

Labor rights involve not just corporations and the state, but civil society as well, playing a vital role. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) focusing on social and economic rights are particularly instrumental in providing direct services to individuals who have suffered human rights violations.

These services offered by NGOs can take various forms, such as providing humanitarian assistance to those in need, offering protection for vulnerable individuals, or facilitating training programs to empower individuals with new skills. In cases where labour rights are legally protected, NGOs may engage in legal advocacy, offering advice and guidance on how to present claims or seek legal recourse. (Council of Europe)

The involvement of civil society organizations adds an essential dimension to the overall effort in promoting and safeguarding labor rights. Their direct services and support help bridge the gap between human rights violations and the necessary assistance needed by those affected. Through their dedicated work, NGOs contribute to creating a more just and inclusive society where individuals can assert their labor rights and access the support they require. (Council of Europe)

In Malaysia, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have played a significant role in combating labor exploitation across various industries. Notably, Transparentem has emerged as a prominent NGO dedicated to bringing about transformation in the industry by shedding light on uncomfortable realities.

Transparentem’s primary objective is to uncover and disclose hidden truths, ultimately driving positive change within industries. By exposing the harsh realities and working conditions, the organization aims to raise awareness and prompt necessary action to address labor exploitation.

Transparentem’s leaders have learned from past experiences that when investigators reveal appalling conditions in Asia, embarrassed Western customers tend to hastily terminate their relationships with suppliers but make little effort to rectify the abuses (Greenhouse). To avoid this pattern, Transparentem takes a different approach. When they uncover serious problems, instead of rushing to publicize them and expose the factories’ Western customers, the organization discreetly informs these companies and urges them to collaborate with the factories to address the issues. The underlying understanding is that Transparentem will eventually disclose its investigative findings and how companies have responded. Western companies are aware that their reputation will be tarnished if they fail to take appropriate action (Greenhouse).

In conclusion, the case study of Top Glove, a Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer, highlights both the remarkable success achieved by the company and the concerning allegations of labor exploitation that have marred its reputation. The growth of Top Glove within the global industry can be attributed to various factors such as regulatory changes, financial crises, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The revelations of labor exploitation shed light on the ethical considerations and responsibilities that corporations and governments must address. Upholding human dignity, ensuring transparency and accountability, and fostering a culture of ethics and social responsibility help create a good labor environment.

Works Cited

Alam, Shah. “Press Release.” Www.topglove.com , 2020, www.topglove.com/single-press-release-en?id=98&title=top-glove-remains-firm-on-its-labour-governance .

Beech, Hannah. “A Company Made P.P.E. For the World. Now Its Workers Have the Virus.” The New York Times , 20 Dec. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/12/20/world/asia/top-glove-ppe-covid-malaysia-workers.html .

Boersma, Martijn. “Do No Harm ? Procurement of Medical Goods by Australian Companies and Government.” Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation & the Australia Institute , Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11024.61443 .

Bureau of International Labor Affairs. “Support for Labor Law and Industrial Relations Reform in Malaysia.” DOL , www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/support-labor-law-and-industrial-relations-reform-malaysia.

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. “Malaysia: Top Glove Denies Migrant Workers Producing PPE Are Exposed to Abusive Labour Practices & COVID-19 Risk; Incl. Responses from Auditing Firms.” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre , 2020, www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/malaysia-top-glove-denies-migrant-workers producing-ppe-are-exposed-to-abusive-labour-practices-covid-19-risk-incl-responses-from-auditing-firms/ .

Council of Europe. “Human Rights Activism and the Role of NGOs.” Council of Europe , 2012, www.coe.int/en/web/compass/human-rights-activism-and-the-role-of-ngos.

Fairlamb, Horace L. Adam Smith’s Other Hand: A Capitalist Theory of Exploitation . 2nd ed., vol. 22, Florida State University Department of Philosophy, 1996, pp. 193–223, www.jstor.com/stable/23560336 .

Fanou, Temisan. Literature Review: Forced Labour Import Bans . 2023, gflc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Forced-Labour-Import-Bans.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2023.

Gek, Tay Peck. “Among Glove Makers, Riverstone Has Most Attractive Margins.” The Business Times , 2022, www.businesstimes.com.sg/companies-markets/among-glove-makers-riverstone-has-most-attractive-margins .

Greenhouse, Steven. “NGO’s Softly-Softly Tactics Tackle Labor Abuses at Malaysia Factories.” The Guardian , 22 June 2019, www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jun/22/ngos-softly-softly-tactics-tackle-labor-abuses-at-malaysia-factories.

Heard, Andrew. “Introduction to Human Rights Theories.” Www.sfu.ca , 2019, www.sfu.ca/~aheard/intro.html.

Hughes, Alex, et al. “Global Value Chains for Medical Gloves during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Confronting Forced Labour through Public Procurement and Crisis.” Global Networks , vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12360 .

Jaafar, Syahirah S. “Top Glove Accorded ‘A’ Rating in Recent Social Audit by Amfori.” The Edge Malaysia , theedgemalaysia.com/article/top-glove%C2%A0accorded%C2%A0-rating-%C2%A0recent-social-audit-amfori.

Kumar, P. Prem. “Malaysia’s Top Glove Q3 Earnings Dented by US Import Ban.” Nikkei Asia , June 2021, asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Malaysia-s-Top-Glove-Q3-earnings-dented-by-US-import-ban.

Lee, Liz, et al. “Analysis: Malaysia’s Labour Abuse Allegations a Risk to Export Growth Model.” Reuters , 22 Dec. 2021, www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysias-labour-abuse-allegations-risk-export-growth-model-2021-12-21/ .

Lee, Liz “Malaysia Charges Top Glove over Poor Quality of Worker Housing.” Www.zawya.com , 2021, www.zawya.com/en/legal/malaysia-charges-top-glove-over-poor-quality-of-worker-housing-q1xsk52r. Accessed 8 July 2023.

Marmo, Marinella, and Rhiannon Bandiera. “Modern Slavery as the New Moral Asset for the Production and Reproduction of State-Corporate Harm.” Journal of White Collar and Corporate Crime , vol. 3, no. 2, June 2021, p. 2631309X2110209.

Miller, Jonathan. “Revealed: Shocking Conditions in PPE Factories Supplying UK.” Channel 4 News , 16 June 2020, www.channel4.com/news/revealed-shocking-conditions-in-ppe-factories-supplying-uk .

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. “The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights- an Interpretive Guide.” OHCHR , 2012, www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/publications/hr.puB.12.2_en.pdf.

Roemer, John. Should Marxists Be Interested in Exploitation? Wiley, 1985, pp. 30–65, www.jstor.org/stable/2265236 .

Ruehl, Mercedes, and William Langley. “US Lifts Import Ban on Malaysia’s Top Glove over Alleged Forced Labour.” Financial Times , 10 Sept. 2021, www.ft.com/content/6e46bde0-355e-46fb-920b-f059fc5b84b5 .

Soken-Huberty, Emmaline. “What Is Human Dignity? Common Definitions.” Human Rights Careers , 7 Apr. 2020, www.humanrightscareers.com/issues/definitions-what-is-human-dignity/ .

Top Glove. “Continuous Improvement Report .” Www.topglove.com , www.topglove.com/continuous-improvement-report.

Palma, Stefania. “US Import Ban Bursts Top Glove Bubble .” Financial Times , 17 June 2021, www.ft.com/content/1f0634c0-8916-442b-a06a-ecde5507d2ea.

Top Glove. “The World’s Largest Manufacturer of Glove.” Www.topglove.com , 2023, www.topglove.com/corporate-profile#:~:text=Top%20Glove%20Corporation%20Bhd%20was .

Yari, Saeed, et al. “Assessment of Semi-Quantitative Health Risks of Exposure to Harmful Chemical Agents in the Context of Carcinogenesis in the Latex Glove Manufacturing Industry.” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention , vol. 17, no. sup3, June 2016, pp. 205–11, https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.s3.205 .

Zaugg, Julie. “The World’s Top Suppliers of Disposable Gloves Are Thriving because of the Pandemic. Their Workers Aren’t.” CNN , 2020, edition.cnn.com/2020/09/11/business/malaysia-top-glove-forced-labor-dst-intl-hnk/ index .html.

Image courtesy of Top Glov

- Exploitation

- Responsibility

- Well-being/welfarism

- Name First Last

- Your Message

Advertisement

Supported by

A Company Made P.P.E. for the World. Now Its Workers Have the Virus.

Top Glove, the world’s largest rubber glove maker, has enjoyed record profits in the pandemic, even as thousands of its low-paid workers in Malaysia suffer from a large outbreak of Covid-19.

- Share full article

By Hannah Beech

BANGKOK — Day after day, as the pandemic gathered force, Yam Narayan Chaudhary stood sentry for 13.5-hour shifts at Top Glove, the Malaysian company that is the world’s largest disposable glove maker. Thousands of foreign workers, many from Nepal like Mr. Chaudhary, lined up as he checked their temperatures and waved them through to the factory.

Top Glove, which controls roughly a quarter of the global rubber glove market, was operating in overdrive, part of a frenzied effort to supply the world with protective equipment for the coronavirus. But as the company shipped gloves all over the world and enjoyed record profits, its low-paid workers in Malaysia began to suffer from a ferocious outbreak of Covid-19, the result of its own inadequate protections, critics say.

In interviews with The New York Times, five current and former Top Glove employees described working with masks soaked in sweat, sweltering in crowded hostels, taking Covid tests for which they were never given results and enduring week after week of overtime shifts that may have left them more vulnerable to the disease.

On Dec. 12, Mr. Chaudhary, 29, died of Covid-19 complications at a hospital in the Malaysian state of Selangor. His friends said he had to wait three days to be admitted to the hospital, even as his breathing deteriorated. The workers say the decision to check into a hospital depends on Top Glove management.

“Our whole family was very much shocked when we heard my brother is no more,” said Bhabindra Chaudhary, who lives in a village in western Nepal where his family are subsistence farmers. “We feel it’s Top Glove’s failure that they are not able to protect their workers.”

Manufacturers in Malaysia have provided essential products during the pandemic, supplying about 60 percent of the world’s disposable gloves. But these companies’ reliance on low-paid migrants laboring without proper protection means that the virus’s victims often come from their own ranks.

About 5,700 of Top Glove’s 11,215 employees in just one of its manufacturing complexes in Malaysia have tested positive for the coronavirus since November, making that cluster of factories the largest active Covid hot spot in Malaysia, according to Ministry of Health statistics.

The outbreak came even as workers and labor activists had warned for months that social distancing rules were not being followed. One whistle-blower said he was recently fired from Top Glove, creating a culture of fear in which few foreign workers dare come forward lest they share the same fate.

“Some challenges arise due to the surge of global demands on gloves considering the pandemic,” Top Glove said in a statement to The Times. “We have mitigation plans to address the challenges to ensure our employees can work in a safe working environment to deliver the lifesaving gloves to those who need it the most.”

The company said that more than 10,000 employees had been tested as of Dec. 16, and that 93 percent of those who had contracted the virus had recovered. Top Glove would not say how many of its workers had tested positive.

Across the world, frontline workers such as meatpackers or farmers are often particularly exposed to Covid-19, even as they are subjected to long hours and paltry compensation.

In Singapore, which neighbors Malaysia, almost half of the city-state’s low-wage migrant workers living in high-density dormitories have been infected with the coronavirus, the government announced last week . While there have been few deaths from the virus in Singapore, nearly 153,000 foreign laborers contracted it, compared with fewer than 4,000 cases in the rest of the population, an indicator of how quickly the disease spreads in crowded quarters.

Touring Top Glove hostels last month, M. Saravanan, Malaysia’s minister of human resources, called the living conditions “terrible.”

“This is a matter of life and death of vulnerable workers,” he said.

This month, the Malaysian Labor Department opened 19 investigations to determine whether Top Glove had violated labor standards in five states. The Labor Department says it expects to file charges soon, and Top Glove was ordered to suspend operations in some of its factories for two weeks.

At Top Glove and other disposable glove makers in Malaysia, workers say their employers regularly ignore social distancing and other pandemic strictures even as these companies grow richer amid a production boom. From September to November, Top Glove’s net profits rose more than 20 times compared with the same period last year.

At the urging of European and other governments, Top Glove was given a special exemption to continue operations during Malaysia’s lockdown earlier this year.

“Top Glove is seriously embarking on corrective measures toward improving the accommodations of our workers nationwide,” the company said. “We have taken the lessons learned from the outbreak among our workers and are aware that there are areas that require better adherence for the safety and well-being of our workers and the communities we serve.”

The workers, most of whom spoke with The Times on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal, described being given only one face mask a day, which was drenched with sweat within an hour because of the lack of air-conditioning. In their hostels, they said, at least 20 people shared a single room outfitted with metal bunk beds. Company employees churn out as many as 220 million disposable gloves a day for roughly $300 a month in salary.

As a quality assessor for Top Glove, Yubaraj Khadka, an eight-year veteran from Nepal, said he was unnerved by the lack of pandemic precautions. In May, he took a few photos on his phone of workers lining up for their shifts without adhering to social distancing. He passed the photos to labor activists, in contravention of Top Glove’s rules.

Mr. Khadka said his snapshots were responsible for his dismissal in September, after months during which Top Glove investigated whether he was the source of the leak and used CCTV footage to confirm their suspicions. When the company fired him, they confiscated his mobile phone and scoured it for photographs of the company, he said.

“The Top Glove management’s mentality is that migrant laborers are very low,” Mr. Khadka said. “If I could talk to the bosses, I would say, ‘Treat us better, like humans.’”

Top Glove would not comment on the specifics of Mr. Khadka’s case but said that “the worker left the company on the grounds of misconduct.”

The fate of Mr. Khadka, who has returned to Nepal, has spooked the current workers at Top Glove, who describe an atmosphere of fear in which they worry they will be fired for exposing poor conditions.

This month, a half-dozen Top Glove employees said they were tested for Covid-19 but weren’t given the results. One South Asian worker said he was hospitalized for six days, but Top Glove refused to confirm whether he had contracted the virus.

Top Glove’s troubles predate the surge of coronavirus infections among its ranks. In July, the United States Customs and Border Protection issued an import ban on products from two Top Glove subsidiaries because of suspected forced labor. The workers said that to secure a job at Top Glove and other glove makers in Malaysia, they had to pay agents fees that averaged $5,000. Paying back the recruitment fees can take months or even years, a plight that the International Labor Organization considers to be debt bondage.

At the time, Mr. Saravanan, the minister of human resources, decried the American import ban. “It is unfair to come into a country and just ban the industry,” he said. But later, after touring Top Glove’s living quarters, he said he was appalled by the conditions.

Top Glove’s minority shareholders include state pension funds from Malaysia and Norway. BlackRock, the American investment management firm, is a minor shareholder. BlackRock representatives have met three times this year with Top Glove to discuss the manufacturer’s labor standards.

“Our stewardship team recognized early on that the pandemic amplifies the social and economic risks associated with how businesses treat their people,” BlackRock said in a statement. “We continuously engage with companies to determine how they monitor and manage their broader impacts on employees, clients and communities.”

Labor watchdogs say that while Top Glove’s treatment of its workers is poor, the conditions are worse at smaller Malaysian glove makers whose operations receive less scrutiny.

“Across the Malaysian glove industry, many companies continue to provide no remediation for extortionate recruitment fees that keep their workers firmly in forced labor through debt bondage,” said Andy Hall, a labor rights campaigner. “Workers live in terrible, unsanitary and crowded accommodations; they work long working hours without a rest day in dangerous, dirty and demanding conditions.”

Last week, Kossan, another Malaysian rubber glove maker, told its investors that 427 of its employees had tested positive for the virus in the same state of Selangor as the Top Glove cluster. As of Saturday, the company’s workers said they still had not been given any information about the outbreak. A third glove maker, Hartalega, has also confirmed cases.

In Nepal, the family of Mr. Chaudhary, the security guard who died after contracting Covid-19, said they had not heard from Top Glove. No condolences or information about how to receive his remains have been provided. Mr. Chaudhary left a wife and a baby son whom he never met because he was working in Malaysia.

“He always told us not to be worried about him since this is a global pandemic,” Mr. Chaudhary’s brother, Bhabindra, said. “He always tried to assure us that he is quite young and healthy, so nothing could happen to him with Covid.”

Hannah Beech has been the Southeast Asia bureau chief since 2017, based in Bangkok. Before joining The Times, she reported for Time magazine for 20 years from bases in Shanghai, Beijing, Bangkok and Hong Kong. More about Hannah Beech

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

How the world’s largest maker of rubber gloves is coping with Covid

- How the world’s largest maker of rubber gloves is coping with Covid on x (opens in a new window)

- How the world’s largest maker of rubber gloves is coping with Covid on facebook (opens in a new window)

- How the world’s largest maker of rubber gloves is coping with Covid on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- How the world’s largest maker of rubber gloves is coping with Covid on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Stefania Palma

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As the founder and chairman of the world’s largest rubber glove manufacturer, Lim Wee Chai was not new to health crises when coronavirus struck this year. In its three-decade history, his company Top Glove has responded to outbreaks of H1N1 influenza, Sars and Ebola as well as the HIV/Aids epidemic.

But Covid-19 has spread so far and so fast that it is unlike any other pathogen Lim has ever seen. “This time with Covid-19 the scale is much bigger,” says the 62-year-old billionaire from Top Glove’s Kuala Lumpur headquarters in an FT interview over Zoom. “The whole world has been affected by this pandemic . . . This virus is very strong, very smart . . . Human beings have to think of a better way to overcome the problem”.

While most companies around the globe have been hit by national lockdowns, plunging sales and deep recession, Malaysia-based Top Glove is one of the fortunate few to be making products that are now in the highest demand.

The company’s main challenge has been to keep its 44 factories around the world running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to meet soaring orders for medical gloves from 195 countries, practically every state on the planet.

“Before Covid-19 our production capacity was running at about 85 per cent,” says Lim. “Because of good demand it [has] now increased to 100 per cent. In fact we are also building more new lines, more capacity”.

Even so, Top Glove’s lead time for orders has increased almost 10 times, from 30-40 days to nearly 300 days. Prices are rising as well as output, even as rival rubber glove makers in Malaysia and key Chinese competitors manufacturing from vinyl expand volumes to meet global annual demand now seen as far exceeding last year’s 290bn pieces.

Top Glove’s share price has risen more than 250 per cent this year, giving it a market value of about $10bn in early June. With a 27 per cent stake, Lim himself is now worth about $2.6bn, according to Forbes, the US business media group, putting him among Asia’s 778 billionaires.

His success in the midst of a pandemic is only the latest reminder of south-east Asia’s rising economic and financial clout, with ambassadors from the developed world, including Japan, Australia and the Netherlands, beating a path to his door to help solve supply crises on which their citizens’ health depends.

Top Glove — which claims to account for 26 per cent of the world market for rubber gloves — is an example of the kind of added-value own-brand production the Malaysian government has long sought to help lift the nation from middle-income status into the ranks of advanced economies.

Lim’s personal history reflects this modernisation drive, which has seen an economy based on commodities industrialise and diversify. His ethnic Chinese parents went into business as traders and rubber plantation owners when the country was still emerging from the British empire.

Lim’s early life coincided with the tumultuous early years of Malaysia’s independence, which were marked by tensions between the majority ethnic Malays and the smaller, but largely wealthier, Chinese community, culminating in race riots in 1969. The Malay-dominated government eased the conflict by developing pro-Malay policies which still left scope for Chinese families to succeed, principally in business.

Before founding Top Glove, Lim worked in sales at OYL Industries, a Malaysian air conditioner manufacturer later acquired by Japan’s Daikin, and then went to study in the US, completing an MBA at Sul Ross State University in Texas. He started Top Glove in 1991 with a single production line in a factory in Meru, near Kuala Lumpur, and 100 employees. The company was floated in Kuala Lumpur in 2001 and listed in Singapore, on the region’s most international exchange, in 2016.

Lim’s hands-on business style is widely seen as the source of his success. In rising to commercial prominence, and now in tackling coronavirus, he takes one step at a time. “Every day we have so many problems: marketing problems, supplier problems, production problems . . . every day we solve. If no problem, it’s not a business,” he says.

“You could call him a real industrialist,” says Rizal Ishak, a consultant to Malaysia’s glove manufacturers, citing a strict management culture focused on ensuring seamless production and that “everything is funded well . . . He runs a very tight shop, no question”.

Among the “chairman philosophies” listed on Top Glove’s website is a call on staff to clean, eat, work, exercise and sleep well to achieve “reverse ageing”, accompanied by a photo of Lim playing badminton. Another section lists four types of learners: fast, slow, non-learner or wrong learner. “The choice is yours. What will you choose?” the chairman asks.

The down-to-earth approach is serving the company well with Covid-19. Lim expects sales in the year to August to grow 30 per cent to more than 6bn Malaysian ringgit (US$1.4bn) from RM4.8bn in the last financial year. That compares with a compound annual growth rate of 21 per cent in the last 19 years. CIMB, a Malaysian bank, forecasts Top Glove’s net profit to more than double from RM368m in 2019 to RM864m this year and RM1.2bn by 2021.

Every day we have so many problems: marketing, suppliers, production . . . every day we solve Lim Wee Chai

The overwhelming demand, which has seen desperate governments leapfrogging each other to buy protective gear for health workers, has allowed glove manufacturers to raise prices. Lim says the price of his gloves has grown about 10 per cent per month since February while the “spot” price, for immediate delivery, has doubled. “But 90 per cent [of our glove output] is sold to our regular customers. Ten per cent may be [sold at the] spot price”.

He says the company did what it could to fill orders coming from around the world and to answer the foreign diplomats’ appeals. “They asked us to help. We did our best to try to fulfil their requirements,” says Lim, adding he also recently received inquiries from the World Health Organization on behalf of less developed countries in Africa and elsewhere.

Top Glove is well placed to benefit commercially. Walter Aw, a senior analyst at CIMB, says that among its Malaysian competitors, “Top Glove is in a prime position to benefit because they’re the largest glove maker in terms of capacity [and they have] the largest distribution network.”

Ramping up production amid global supply chain glitches and closed borders has not been easy. Malaysia itself imposed a near-total lockdown from mid-March, which only started to ease earlier this month.

Top Glove’s suppliers, mainly located in Malaysia, which accounts for the bulk of its output alongside plants in Thailand and China, shut down for about a fortnight. But with the company typically holding two weeks’ stock of raw materials, Lim says production did not suffer. “If suppliers [had] continued to delay our stock for one month then we’d be in trouble,” he adds.

Lim says that avoiding coronavirus contagion among his workforce has been a challenge, but that employing doctors, nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists and dentists on site has helped Top Glove manage the risks.

The company, with 19,000 employees, is also facing labour shortages as it looks to increase its 12,000-strong production floor staff to ensure it runs at full capacity.

While foreign workers account for about 60 per cent of Top Glove’s personnel, mainly from Nepal and Bangladesh, Malaysia’s closing of its borders in March forced the company to focus on hiring locally. “[We] still have some shortage . . . but we should be able to get enough workers from companies that are retrenching and reducing their workforce,” he says.

Difficulties recruiting labour, even from abroad, have landed the industry in controversy over claims that employers have exploited migrant workers. In December 2018, The Guardian newspaper reported allegations from 16 foreign workers employed at Top Glove in Malaysia that they were required to work long hours for low pay. They also claimed that they had had their passports held by the company and were unable to get them back. Labour activists regard this practice as coercive as it can hinder a worker’s freedom of movement.

Top Glove told The Guardian at the time that it was working to address excessive overtime working. It said it met “local labour law requirements” and had “a zero-tolerance policy with any regard to the abuse” of human rights. Asked for comment by the FT for this article, Top Glove denied any wrongdoing, citing its 2019 annual report in which it said the Guardian report was “highly inaccurate” and set out detailed changes in labour policies. The annual report says the company had “revised” its safekeeping policy on foreign workers’ passports and “workers now have full custody of their passports”. Top Glove told the FT that the policy was changed in December 2018.

The annual report also refers to steps the company has taken to tackle another problem often linked with migrant labour — heavy recruitment charges imposed by employment agents on workers. The Top Glove report says that in January 2019, the company implemented a “zero recruitment fee policy” under which it bears “all the recruitment fees and costs associated with accommodation, medical check-ups and travelling”.

It did not answer an FT question about who paid the recruitment fees before the policy change but said “we continuously improve and strengthen” our policies and it had ended relationships with recruitment agents who failed to meet its standards.

In the longer term, Malaysian glove makers face structural challenges. While the industry is now in the limelight, its products are low-added-value goods, selling for low prices (outside a pandemic). By value, medical and non-sterile gloves represent only 1.3 per cent of Malaysia’s total exports of goods and services.

Richard Record, lead economist for Malaysia at the World Bank, says productivity remains a concern for a sector that relies heavily on labour-intensive manufacturing. So if Malaysia wants to fulfil its aspiration of becoming a high-income country, “it will be key to focus more on building the quality of workforce skills, promoting quality investments, and intensifying technology adoption across all sectors of the economy to boost competitiveness, including in the manufacture of protective medical equipment,” he adds.

If he is right, the glove makers’ problems in hiring low-cost labour will only multiply. So will the challenges for the rubber producers, who have in recent years abandoned plantations because prices have been too low.

And even though Malaysia is the world’s third-largest rubber grower, it is also the third-biggest importer, as demand far exceeds local supply. The glove makers source two-thirds of their needs for latex — a semi-processed material made from rubber — via imports, mainly from other south-east Asian states.

In its annual report, Top Glove says its financial performance is susceptible to commodity price fluctuations, particularly in latex. But Aw, the CIMB analyst, is not worried given that an oversupply of latex is keeping it cheap while rubber glove prices are rising.

Lim remains optimistic about the future. Top Glove will overcome the current global recession “because we are in the right industry and we have the right team of people,” he says. “We have overcome five epidemics over the past 30 years. That’s why we must have a good foundation.”

The company is investing in new products, including biodegradable gloves, self-cleaning gloves, low-allergy gloves and moisturising gloves. It has diversified into condoms, dental products and latex tourniquets.

Looking ahead, he is clear about Top Glove’s objectives. He wants his company to join the Fortune Global 500 by 2040, which will involve increasing the company’s revenues 30-fold and expanding to 500 factories. “If we put enough effort I’m sure we can achieve our target in 20 years,” he says.

As for personal goals, Lim is determined to live until he is 120 years old by following the principles of healthy living he has enshrined at Top Glove. “I am still very young . . . it’s just started”.

This article is part of FT Wealth , a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment.

Promoted Content

Follow the topics in this article.

- Retail & Consumer industry Add to myFT

- Health Add to myFT

- Coronavirus Add to myFT

- Top Glove Corporation Berhad Add to myFT

- FT Wealth Add to myFT

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Yubaraj Khadka, a worker in Malaysia for Top Glove Corp (TPGC.KL), took two photos in May of fellow employees crowding into a factory of the world's biggest maker of medical-grade latex gloves.

In conclusion, the case study of Top Glove, a Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer, highlights both the remarkable success achieved by the company and the concerning allegations of labor exploitation that have marred its reputation. The growth of Top Glove within the global industry can be attributed to various factors such as regulatory changes ...

"Top Glove's 'Covid-19 heroes' scheme 'underpays' gloves workers who toil 7 days a week", 1 May 2020. Glove manufacturer Top Glove is "unethically" skirting labour laws by launching a scheme to get workers to work seven days a week on a "voluntary basis", for a sum much lower than the standard wage, labour activists believe.

Top Glove admitted the incident took place but called it "an isolated case" and said the supervisor involved was dismissed. Auditors also found evidence of physical abuse at Kossan and ...

In June 2020, a Channel 4 investigation exposed evidence of migrant worker exploitation - including low wages, excessive overtime, illegal deductions from workers' salaries, extortionate recruitment fees, poor living conditions and lack of social distancing arrangements - at Top Glove factories in Malaysia. Top Glove is the world's largest manufacturer of medical gloves and has reported ...

Malaysia: Hidden cameras reveal poor working & living conditions at Top Glove factory, fuelling forced labour concerns in glove industry; incl. company comments Date: 19 Jan 2021 Content Type: Article; Malaysia: Gov't moves to close 28 Top Glove factories as COVID-19 infections linked to operations reach 2,524 Date: 23 Nov 2020 Content Type ...

A volunteer delivers food to Top Glove workers at a hostel after it was locked down. The world's largest maker of latex gloves will shut more than half of its factories after almost 2,500 ...

Dec. 20, 2020. BANGKOK — Day after day, as the pandemic gathered force, Yam Narayan Chaudhary stood sentry for 13.5-hour shifts at Top Glove, the Malaysian company that is the world's largest ...

Before founding Top Glove, Lim worked in sales at OYL Industries, a Malaysian air conditioner manufacturer later acquired by Japan's Daikin, and then went to study in the US, completing an MBA ...

The United States on Friday allowed imports from Malaysia's Top Glove Corp , after customs authorities lifted a year-long ban imposed for alleged forced labour found at the world's largest medical ...