- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Abstract – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Abstract

Research Paper Abstract is a brief summary of a research pape r that describes the study’s purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions . It is often the first section of the paper that readers encounter, and its purpose is to provide a concise and accurate overview of the paper’s content. The typical length of an abstract is usually around 150-250 words, and it should be written in a concise and clear manner.

Research Paper Abstract Structure

The structure of a research paper abstract usually includes the following elements:

- Background or Introduction: Briefly describe the problem or research question that the study addresses.

- Methods : Explain the methodology used to conduct the study, including the participants, materials, and procedures.

- Results : Summarize the main findings of the study, including statistical analyses and key outcomes.

- Conclusions : Discuss the implications of the study’s findings and their significance for the field, as well as any limitations or future directions for research.

- Keywords : List a few keywords that describe the main topics or themes of the research.

How to Write Research Paper Abstract

Here are the steps to follow when writing a research paper abstract:

- Start by reading your paper: Before you write an abstract, you should have a complete understanding of your paper. Read through the paper carefully, making sure you understand the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Identify the key components : Identify the key components of your paper, such as the research question, methods used, results obtained, and conclusion reached.

- Write a draft: Write a draft of your abstract, using concise and clear language. Make sure to include all the important information, but keep it short and to the point. A good rule of thumb is to keep your abstract between 150-250 words.

- Use clear and concise language : Use clear and concise language to explain the purpose of your study, the methods used, the results obtained, and the conclusions drawn.

- Emphasize your findings: Emphasize your findings in the abstract, highlighting the key results and the significance of your study.

- Revise and edit: Once you have a draft, revise and edit it to ensure that it is clear, concise, and free from errors.

- Check the formatting: Finally, check the formatting of your abstract to make sure it meets the requirements of the journal or conference where you plan to submit it.

Research Paper Abstract Examples

Research Paper Abstract Examples could be following:

Title : “The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Treating Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This meta-analysis examines the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in treating anxiety disorders. Through the analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials, we found that CBT is a highly effective treatment for anxiety disorders, with large effect sizes across a range of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Our findings support the use of CBT as a first-line treatment for anxiety disorders and highlight the importance of further research to identify the mechanisms underlying its effectiveness.

Title : “Exploring the Role of Parental Involvement in Children’s Education: A Qualitative Study”

Abstract : This qualitative study explores the role of parental involvement in children’s education. Through in-depth interviews with 20 parents of children in elementary school, we found that parental involvement takes many forms, including volunteering in the classroom, helping with homework, and communicating with teachers. We also found that parental involvement is influenced by a range of factors, including parent and child characteristics, school culture, and socio-economic status. Our findings suggest that schools and educators should prioritize building strong partnerships with parents to support children’s academic success.

Title : “The Impact of Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”

Abstract : This paper presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature on the impact of exercise on cognitive function in older adults. Through the analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials, we found that exercise is associated with significant improvements in cognitive function, particularly in the domains of executive function and attention. Our findings highlight the potential of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention to support cognitive health in older adults.

When to Write Research Paper Abstract

The abstract of a research paper should typically be written after you have completed the main body of the paper. This is because the abstract is intended to provide a brief summary of the key points and findings of the research, and you can’t do that until you have completed the research and written about it in detail.

Once you have completed your research paper, you can begin writing your abstract. It is important to remember that the abstract should be a concise summary of your research paper, and should be written in a way that is easy to understand for readers who may not have expertise in your specific area of research.

Purpose of Research Paper Abstract

The purpose of a research paper abstract is to provide a concise summary of the key points and findings of a research paper. It is typically a brief paragraph or two that appears at the beginning of the paper, before the introduction, and is intended to give readers a quick overview of the paper’s content.

The abstract should include a brief statement of the research problem, the methods used to investigate the problem, the key results and findings, and the main conclusions and implications of the research. It should be written in a clear and concise manner, avoiding jargon and technical language, and should be understandable to a broad audience.

The abstract serves as a way to quickly and easily communicate the main points of a research paper to potential readers, such as academics, researchers, and students, who may be looking for information on a particular topic. It can also help researchers determine whether a paper is relevant to their own research interests and whether they should read the full paper.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

How to Publish a Research Paper – Step by Step...

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

- Our History

- The Council

- Verna Wright Prize

- The Secretariat

- Key Documents and Policies

- 2024 Conference

- Abstract Submission Guidance 2024

- Past Conferences

- Past Keynote Speakers

- Courses and Lectures

- Co-Hosted Events

- External Events

- Research – Presenting Abstracts

- Research Projects

- Research Links

- Research Councils

- Qualitative Research Abstracts

- Fellowships, Studentships and Awards

- Published Abstracts

- Training Awards

- General Links

- Professional Organisations

- University and Research Vacancies

- Newsletters

- Council Reports and Society Forms

- SRR Membership

- Symposia Presentations

- Members Newsletter

- Business Minutes

- Search for:

GUIDANCE ON SUBMISSION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH ABSTRACTS

General guidance

Authors should refer to the general information and guidelines contained in the Society’s “Guidance for Submission of Abstracts”. The general guidance therein applies to qualitative research abstracts. This includes the maximum permitted limit of 250 words, and the instruction that abstracts should be structured. In keeping with all submissions to the Society, subsequent presentation must reflect and elaborate on the abstract. Research studies or findings not referred to in the abstract should not be presented.

This document contains specific guidance on the content of qualitative research abstracts.

How guidance on content is to be applied by authors and Council.

Council recognises that the nature of qualitative research makes its comprehensive communication within short abstracts a challenge. Therefore, whilst the key areas to be included within abstracts are set out below, it is recognised that emphasis on each area will vary in different cases, and that not every listed sub-area will be covered. Certain elements are likely to receive greater attention at the time of presentation than within the abstract. In particular, presentation of the paper should include sufficient empirical data to allow judgement of the conclusions drawn.

Content of abstracts

- Research question/objective and design: clear statement of the research question/objective and its relevance. Methodological or theoretical perspectives should be clearly outlined.

- Population and sampling: who the subjects were and what sampling strategies were used .

- Methods of data collection: clear exposition of data collection: access, selection, method of collection, type of data, relationship of researcher to subjects/setting (what data were collected, from where/whom, by whom)

- Quality of data and analysis: strategies to enhance quality of data analysis e.g. triangulation, respondent validation; and to enhance validity e.g. attention to negative cases, consideration of alternative explanations, team analysis, peer review panels

- Application of critical thinking to analysis: attention to the influence of the researcher on data collected and on analysis. Critical approach to the status of data collected

- Theoretical and empirical context: evidence that design and analysis take into account and add to previous knowledge

- Conclusions: justified in relation to data collected, sufficient original data presented to substantiate interpretations, reasoned consideration of transferability to groups/settings beyond those studied

Username or email address *

Password *

Remember me Log in

Lost your password?

Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Nursing, Umeå University, SE-90187, Umeå, Sweden. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Nursing, Umeå University, SE-90187, Umeå, Sweden.

- 3 Department of Nursing, Umeå University, SE-90187, Umeå, Sweden; Department of Health Sciences, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden.

- PMID: 32505813

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

Qualitative content analysis and other 'standardised' methods are sometimes considered to be technical tools used for basic, superficial, and simple sorting of text, and their results lack depth, scientific rigour, and evidence. To strengthen the trustworthiness of qualitative content analyses, we focus on abstraction and interpretation during the analytic process. To our knowledge, descriptions of these concepts are sparse; this paper therefore aims to elaborate on and exemplify the distinction and relation between abstraction and interpretation during the different phases of the process of qualitative content analysis. We address the relations between abstraction and interpretation when selecting, condensing, and coding meaning units and creating categories and themes on various levels. The examples used are based on our experiences of teaching and supervising students at various levels. We also highlight the phases of de-contextualisation and re-contextualisation in describing the analytic process. We argue that qualitative content analysis can be both descriptive and interpretative. When the data allow interpretations of the latent content, qualitative content analysis reveals both depth and meaning in participants' utterances.

Keywords: Abstraction; De-contextualisation; Interpretation; Qualitative content analysis; Re-contextualisation.

Copyright © 2020. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Publication types

- Abstracting and Indexing / methods*

- Data Analysis*

- Qualitative Research

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![abstract of qualitative research example “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![abstract of qualitative research example “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![abstract of qualitative research example “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

University Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Qualitative Data Analysis: Find Methods Examples

- Atlas.ti web

- R for text analysis

- Microsoft Excel & spreadsheets

- Other options

- Planning Qual Data Analysis

- Free Tools for QDA

- QDA with NVivo

- QDA with Atlas.ti

- QDA with MAXQDA

- PKM for QDA

- QDA with Quirkos

- Working Collaboratively

- Qualitative Methods Texts

- Transcription

- Data organization

- Example Publications

- Find Methods Examples

Locating Methods Examples

Find dissertations that cite a core methods work.

You can conduct a cited reference search in the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database.

Example Two Heading

Example Two Body

Example Three Heading

Example Three Body

- << Previous: Example Publications

- Last Updated: Jun 6, 2024 9:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/qualitative

Vignettes: an innovative qualitative data collection tool in Medical Education research

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sylvia Joshua Western ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4397-6746 1 ,

- Brian McEllistrem 1 ,

- Jane Hislop 1 ,

- Alan Jaap 1 &

- David Hope 1

This article describes how to make use of exemplar vignettes in qualitative medial education research. Vignettes are particularly useful in prompting discussion with participants, when using real-life case examples may breach confidentiality. As such, using vignettes allows researchers to gain insight into participants’ thinking in an ethically sensitive way.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Vignettes are written, visual, or oral stimuli portraying realistic events in a focussed manner, purposefully aligned with the research objectives and paradigms to elicit responses from research participants [ 1 ]. They have been used in qualitative research to explore physical, social, and mental health–related topics. Although clinical vignettes are widely used in teaching and assessment, vignettes are under-utilised as a research tool in medical education. In this article, we outline the ways in which we found vignettes to be helpful in addressing our research aims prompting a conversation on how they might be used in other medical education research contexts, particularly when working with sensitive issues.

We used vignettes within individual semi-structured interviews, to explore how medical educators interpreted different test-wise behaviours (“ skills and strategies that are not related to the construct being measured on the test but that facilitate an increased test score ”[ 2 ]). We opted to use vignettes for the following reasons:

Akin to clinical vignettes, they enable usage of anonymised and fictionalised version of real-life case studies, protecting the identity and confidentiality of the original individuals [ 3 ]. Vignettes retained the essence of the event but potential identifiers or personal information from the original were redacted or anonymized.

Realistic scenarios support the exploration of sensitive topics which can generate authentic ethical dilemmas. Instead of asking “Have you ever tried to trick your examiner into giving you more marks”? - a question which might cause distress or harm to participants, we could posit a vignette and ask our participants for a third-person perspective. Vignettes therefore promote participants’ psychological safety by providing an alternative non-confronting and safer avenue to discuss value-laden constructs [ 1 ].

When discussing complex ambiguous topics, they provide a focus to help participants orient to the specific matter at hand [ 3 ]. Vignettes help define and communicate the context, setting, character, and situation succinctly.

Using an established framework of Skilling & Stylianides [ 1 ], we constructed five vignettes portraying a spectrum of test-wise behaviours. We drew on informal conversations with stakeholders, online forums, our professional experience, academic literature, and knowledge of the local context to draft the vignettes. Our aim was to understand how people make meaning, what guided their decisions and reactions to test-wise behaviours. Following feedback from experts and several pilot interviews, we revised the vignettes. As such we found that the process of building vignettes was iterative, collaborative, and continuously evolving.

Using previous case studies employing vignettes for data collection, we reflected on the iterative process of constructing, peer and expert reviewing, piloting, and deploying vignettes to eight participants. Participants were staff and students at Edinburgh Medical School. By contemplating the decision-making pathway that aided vignette construction, studying the reflective notes of the interviewer, thematically analysing interview transcripts, and engaging in an ongoing discussion and feedback loops with our expert and supervisory panel, we identified eight factors making vignettes especially useful:

By controlling the age, sex, and ethnicity of subjects, we could explore how participants interpreted and reacted to different test-wise behaviours of different students.

Following discussion, participants commented on the realism of the vignettes, allowing for iteration of the vignettes over time.

Vignettes facilitated subjective interpretation of complex situations and allowed for intentional reflection on thoughts and actions.

Participants had the agency to discuss their own attitudes in relation to the vignettes and used them to explore their real-life experiences.

We tailored the frequency and type of vignette based on the participant’s role, and selected vignettes to explore issues under-discussed in previous interviews.

Criticising real actions and guidelines can be challenging. Discussing hypothetical vignettes allowed for openness, honesty, and pragmatic answers.

Exposing participants to novel vignettes helped the researchers compare their expectations and beliefs to participant views. Participants found the vignettes plausible, which suggested the researchers had a defensible understanding of the topic.

We can compare the interpretation of the same vignette by different individuals in different roles to understand the underlying rationale for their differing perspectives. Follow-up interviews allow for the exploration of changes over time.

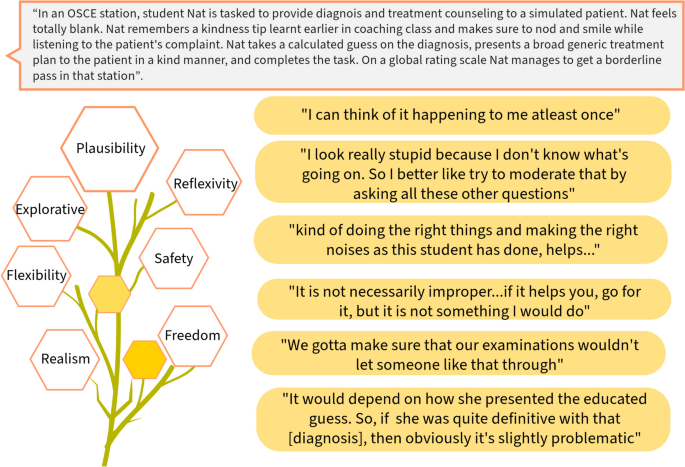

Figure 1 shows an exemplar vignette with excerpts of participant responses. Rather than ask how they would feel if an exam candidate used false empathy to conceal their lack of content knowledge, we used Nat vignette (in Fig. 1 ) as a realistic case study to facilitate discussion. The broader themes in the left side of the infographic (Fig. 1 ) speak to some of the factors identified previously, acting as a teaser facilitating the readers to think through the participant responses. For example, the snippet “I can think of it happening to me at least once” connects to plausibility and realism - the participant thinks that this is a plausible scene in their context, and it seems real to them.

Example vignette with excerpts of participant responses

Firstly, a challenge we faced pertained to participant engagement. While all participants found the example vignette (in Fig. 1 ) both plausible and relatable, the pattern of engagement varied among them. Some used it as a springboard to delve into their own real-life stories, while others found it challenging to reconcile the artificial and hypothetical nature of the vignette. The effectiveness of vignettes hinges on participant engagement. Drawing from our experience and the supporting literature, we found that vignettes must be relatable [ 3 ], plausible [ 3 ], and situated in context [ 1 ]. Participants must be oriented to the vignette method before interview and be given the vignettes at appropriate times during the interview. It is essential when using vignettes to gauge and promote engagement during the interview. Tailored questions and prompts are helpful strategies to promote such engagement. Secondly, we agree that however realistic vignettes are, they are “not real”, therefore participants’ responses to hypothetical vignettes might not perfectly align with their reactions to real-life situations, for instance, considering their underlying motivational relevance to the different contexts - research environment and real-life [ 3 ]. Researchers should remain aware of these challenges and interpret their findings with caution [ 3 ].

In conclusion, our use of vignettes was an innovative alternative to using high-stakes, confidential real-life case examples in qualitative research. Usage of vignette opens new possibilities in medical education research: they can be used within questionnaire surveys, individual and focus group interviews, or as ethnographic field notes. They offer a versatile approach to allow exploration of high-stakes, sensitive, and ethically contentious issues with participants in a safe way. Therefore, researchers can benefit significantly from applying vignettes in their own research.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Skilling K, Stylianides GJ. Using vignettes in educational research: a framework for vignette construction. Int J Res Method Educ. 2020;43(5):541–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1704243 .

Article Google Scholar

American Psychological Association. Testwise. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org/testwise . Updated April 19, 2018. Accessed 20 May 2024.

Jenkins N, Bloor MJ, Fischer J, Berney L, Neale J. Putting it in context: the use of vignettes in qualitative interviewing. Qual Res. 2010;10(2):175–98.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Sylvia Joshua Western, Brian McEllistrem, Jane Hislop, Alan Jaap & David Hope

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sylvia Joshua Western .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Western, S.J., McEllistrem, B., Hislop, J. et al. Vignettes: an innovative qualitative data collection tool in Medical Education research. Med.Sci.Educ. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02074-0

Download citation

Accepted : 10 May 2024

Published : 05 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-02074-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Medical education

- Data collection

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 06 June 2024

Flemish critical care nurses’ experiences regarding the influence of work-related demands on their health: a descriptive interpretive qualitative study

- Lukas Billiau ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0009-9563-0999 1 ,

- Larissa Bolliger 2 ,

- Els clays 2 ,

- Kristof Eeckloo 1 , 2 &

- Margo Ketels 2

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 387 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

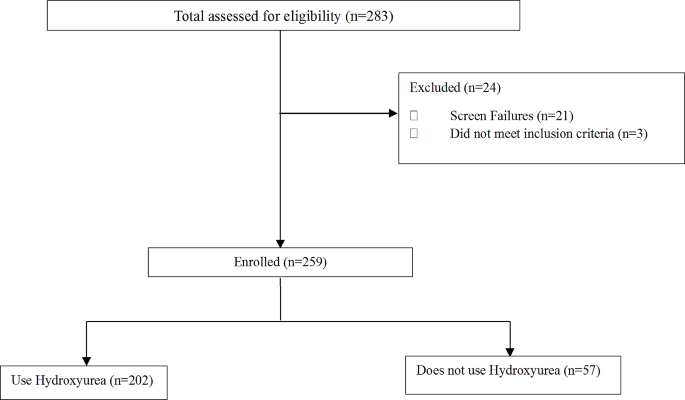

Critical care nurses (CCNs) around the globe face other health challenges compared to their peers in general hospital nursing. Moreover, the nursing workforce grapples with persistent staffing shortages. In light of these circumstances, developing a sustainable work environment is imperative to retain the current nursing workforce. Consequently, this study aimed to gain insight into the recalled experiences of CCNs in dealing with the physical and psychosocial influences of work-related demands on their health while examining the environments in which they operate. The second aim was to explore the complex social and psychological processes through which CCNs navigate these work-related demands across various CCN wards.

A qualitative study following Thorne’s interpretive descriptive approach was conducted. From October 2022 to April 2023, six focus groups were organised. Data from a diverse sample of 27 Flemish CCNs engaged in physically demanding roles from three CCN wards were collected. The Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven was applied to support the constant comparison process.

Participants reported being exposed to occupational physical activity, emotional, quantitative, and cognitive work-related demands, adverse patient behaviour, and poor working time quality. Exposure to these work-related demands was perceived as harmful, potentially resulting in physical, mental, and psychosomatic strain, as well as an increased turnover intention. In response to these demands, participants employed various strategies for mitigation, including seeking social support, exerting control over their work, utilising appropriate equipment, recognising rewards, and engaging in leisure-time physical activity.

Conclusions

CCNs’ health is challenged by work-related demands that are not entirely covered by the traditional quantitative frameworks used in research on psychologically healthy work. Therefore, future studies should focus on improving such frameworks by exploring the role of psychosocial and organisational factors in more detail. This study has important implications for workplace health promotion with a view on preventing work absenteeism and drop-out in the long run, as it offers strong arguments to promote sufficient risk management strategies, schedule flexibility, uninterrupted off-job recovery time, and positive management, which can prolong the well-being and sustainable careers of the CCN workforce.

Peer Review reports

Globally, the nursing profession is a strenuous occupation with high levels of work-related demands, leading to adverse health outcomes for nurses [ 1 ], reduced marital and life satisfaction [ 2 ], absenteeism, and high costs for society [ 3 ]. In addition, the nursing workforce has to address staffing shortages due to the reduced number of individuals entering the nursing profession [ 4 ], the ageing working population [ 5 ], and the increased number of nurses in premature retirement [ 6 , 7 ].

Especially critical care nurses (CCNs), who specialise in managing life-threatening diseases across all age groups, work in an exceptionally demanding environment [ 8 ]. Increasing evidence suggests that CCNs’ health is mainly challenged by five work-related demands, namely, occupational physical activity (OPA) [ 1 ], shiftwork [ 9 ], and quantitative [ 10 ], cognitive [ 11 ], and emotional work-related demands [ 12 ]. Among CCNs, OPA involves various physically demanding tasks, such as forward bending and isometric neck postures, heavy lifting, prolonged standing, and long-distance walking [ 1 , 9 ]. With continued exposure to OPA, musculoskeletal disorders can arise in terms of pain-related complaints of the wrists, back, thigh, knees, and feet [ 1 ]. However, many studies have reported that engaging in regular leisure-time physical activity has a beneficial influence on health, while OPA may have no beneficial, or even adverse, influence on health [ 13 ]. These conflicting health influences are indicated as the “physical activity health paradox” [ 13 ] and might be explained by differences in duration, intensity, recovery opportunities, and physiological responses [ 14 , 15 ].

In addition to OPA is shift work, which is the amount of time an individual works outside the typical nine AM to five PM schedule, known to impact CCNs’ health through circadian rhythm disruption, fatigue, and social isolation [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. First, circadian rhythm disruption induces the proliferation of dysfunctional immune cells and is likely to cause cancer [ 19 ], coronary heart disease [ 20 ], diabetes mellitus [ 21 ], and gastrointestinal disorders [ 18 , 22 ]. Second, fatigue may contribute to the development of cancer [ 16 ], coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal disorders [ 23 ], and psychological stress [ 18 , 24 ]. Finally, CCNs report experiencing social isolation because shift work makes it difficult for them to participate in leisure-time activities or family time, which can lead to depression [ 25 , 26 ].

Furthermore, CCNs face quantitative work-related demands regarding high workload, time pressure, and workflow interruptions [ 10 , 27 ]. These demands impair CCNs’ mental focus and increase the likelihood of developing prolonged fatigue and stress [ 10 ]. In addition, CCNs need to deal with high levels of cognitive work-related demands, which can be defined as: “burdens placed on the brain processes involved in information processing” [ 28 , p.1574]. These cognitive work-related demands above the acceptable threshold contribute to attention narrowing, psychological stress, and burnout [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Moreover, CCNs are exposed to emotional work-related demands that require them to exert effort to deal with the desired emotional responses [ 28 ]. These demands involve workplace violence and end-of-life care issues and can cause anxiety, fatigue, and depression [ 12 , 32 ].

Given the number of studies having postulated the adverse health effects of work-related demands, there is an increasing need for developing mitigating strategies to guarantee extended healthy working lives [ 33 ]. From a theoretical perspective, the Job Demand-Control-Support model [ 34 ] hypothesises job control and workplace social support as psychosocial moderators to mitigate the strenuous impact of work-related demands on health [ 35 ]. In particular, job control refers to: “a working individual’s potential control over his task and his conduct during the working day” [ 36 , pp. 289–290]. It has been argued that job control can reduce the physiological impact of work-related demands on employees’ health by allowing them to take a break if necessary [ 35 ]. Likewise, workplace social support can be considered as interpersonal relationships at work to cope with stressful situations by putting them into another perspective, thereby leading to less psychological stress [ 37 ]. Additionally, the Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 38 ] considers the prevention of adverse health outcomes by providing sufficient rewards in line with the performed efforts at work [ 39 ].

Numerous correlational studies are available which research the impact of work-related demands on nurses’ health [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. To our knowledge, no qualitative studies have comprehensively investigated how exposure to multiple work-related demands influences CCNs’ health, or the complex social and psychological processes through which CCNs navigate these work-related demands across various CCN wards. However, it is essential to identify new factors in the research of CCNs’ work-related health and to create a policy that prevents health complaints and their associated costs.

The aims and design of the study

This qualitative study was based on Thorne’s interpretive descriptive approach [ 43 ] and was part of the Flemish Employees’ Physical Activity study [ 44 ]. Thorne’s interpretive descriptive approach embraces the concept that reality is shaped by social constructs, acknowledging the existence of diverse constructed realities [ 43 ]. Thus, this approach was appropriate to gain insight into the recalled experiences of CCNs in dealing with the physical and psychological influence of work-related demands on their health, while also examining the environments in which they operate [ 43 ]. In addition, this approach was well suited to explore the complex social and psychological processes through which CCNs navigate these work-related hazards across various CCN wards [ 43 ].

Setting and participants

This study was conducted in a local hospital in Flanders (Belgium) with a capacity of 1046 beds. First, 18 CCNs were recruited between October 2022 and January 2023 by means of convenience sampling to ensure a wide range of experiences by posting recruitment flyers in the CCNs’ lockers and placing posters in the CCN wards. Moreover, an invitation mail with informed consent was sent to the head nurses, who then delivered this mail to their CCNs. However, the CCNs could also participate by directly expressing their willingness to engage by email to the research team. Eligibility criteria required CCNs to be employed for more than 50% in the emergency department (ED), intensive care unit (ICU), stroke unit, or the critical care mobile nursing team and to be Dutch speaking. Nurses of the critical care mobile nursing team were employed simultaneously in the ED, ICU, and stroke unit. CCNs in management positions were not included due to their potential impact on the reporting of their subordinates’ experiences [ 45 ].

According to the insights that emerged after the intermediate analysis of the first four focus groups, nine CCNs were purposively selected between January 2023 and April 2023 via a snowball sampling technique to deepen the understanding of the discussed topics from earlier focus groups [ 46 ]. For example, CCNs reported the detrimental influence of prehospital physician-staffed emergency care interventions on their health. Therefore, CCNs with similar and diverse experiences in prehospital physician-staffed emergency care interventions were recruited.

Data collection

Data collection methods.

Thorne’s interpretive descriptive approach was applied by conducting focus groups, which refer to a guided discussion with several people to explore ideas and perceptions about a specific topic from a multiplicity of views [ 47 ]. Conducting focus groups has several benefits, such as stimulating group dynamics, revealing deeper expressions of genuine feelings and beliefs, and enabling the acquisition of rich information in a cost-effective manner. Furthermore, the multiplicity of views during focus groups is useful to deepen the understanding of the complex social and psychological processes through which CCNs navigate their work-related demands, as these views could generate new ideas and perspectives that yield unexpected insights into the recalled experiences.

The research team consisting of experts in occupational health (EC, MK, and LBo), emergency nursing (LBi), and qualitative research (LBo) developed a semi-structured focus group guide (Table 1 ). This guide sought to explore the recalled experiences of CCNs in dealing with the physical and psychological influence of their work-related demands on their health and to identify strategies in which CCNs could mitigate this influence. The focus group guide used a deductive approach because of the preliminary exploration of the Job Demand-Control-Support model [ 34 ], the Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 38 ], and the Sixth European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) [ 48 ]. However, the focus groups were conducted with an open mind to identify new topics and to stimulate further questions that could contribute to the in-depth understanding of the CCNs’ recalled experiences [ 43 ]. As a result, the focus group guide became more focused when the transcripts were coded and preliminary ideas of the research team emerged [ 49 ].

Data collection procedure

Between October 2022 and April 2023, six focus groups were held in a comfortable meeting room after lunchtime at the local hospital in Flanders (Belgium). Each focus group consisted of four to five CCNs from the same CCN ward and lasted uninterrupted for a maximum of 90 minutes, with an average duration of 68.75 minutes. The first 60 minutes were during working time, and the rest could be accounted as overtime. All focus groups were conducted by one master’s student in nursing science (LBi). The data collection process was supervised by an experienced qualitative researcher in occupational health (LBo) who provided feedback on the interview style. The master’s student was known superficially at the ED in the local hospital due to his previous nursing student work, which helped in understanding and contextualising the complexities and subtleties of the CCNs’ experiences. The interviewer wore clothes from the hospital to reduce the risk of interviewer bias. No observer was present during the focus groups. Because the participants were encouraged to share their experiences freely, the focus group guide was only implemented when the participants discussed topics irrelevant to this study, when a participant was too dominant, or when the discussion needed stimulation [ 45 ]. The interviewer sought to obtain input from all participating CCNs by asking open-ended and probing questions to introvert participants to elicit in-depth views. All focus groups were audiotaped with a smartphone and tablet.

Data analysis

The audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and deleted afterwards. The data analysis process was based on the Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven, which guaranteed a cyclic process between data collection and data analysis to propose a conceptual framework [ 50 ]. The Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven consists of two crucial phases, namely, the preparation of the coding process by paper and pencil work and the actual coding process by using qualitative software [ 50 ].

First, two members of the research team (LBi and LBo) read the transcripts several times to obtain an in-depth understanding of the intricate details [ 18 ]. Second, both researchers wrote down memos and then developed a narrative focus group report for each focus group [ 50 ]. Third, concepts were drawn up to replace tangible or concrete experiences, which allowed the development of a conceptual scheme for each focus group. During this process, the same two researchers discussed and cross-checked the identified analytical and contextual concepts and sought to obtain a detailed understanding of the data [ 50 ]. This constant comparison process through inductive and interpretative reasoning allowed a within-case and across-case analysis to compare new concepts with earlier coded data so that similarities and differences in data could be identified and analysed [ 51 , 52 , 53 ]. Subsequently, the concepts were linked to relevant focus group fragments by using the QSR NVivo 12 software program. During this phase, data were further coded by combining concepts into groups of concepts based on emerging ideas and comparable meanings. These groups of concepts resulted in certain categories and were then divided into subcategories and main categories. The main categories were tested in the existing literature and rooted in the practical and theoretical knowledge of the research team after several intermediate meetings. Finally, the main categories were outlined in a conceptual framework, which represented the essential structure of the results. Data saturation was reached when no new dimensions or relationships emerged during the analysis, which was confirmed by conducting an additional focus group [ 52 ].

Trustworthiness

The confirmability of the data was improved by applying different strategies. During the iterative process, the interview style and the questions arising from the focus group guide that could contribute to the in-depth understanding of the CCNs’ recalled experiences were peer-reviewed by the research team. Next, investigator triangulation was applied by two researchers with prior experience in the nursing profession (LBi and LBo) who analysed the transcripts independently and discussed the inductive code tree continuously. These transcripts and inductive code tree were then peer-reviewed by the entire research team at several intermediate meetings.

In addition, an audit trail with detailed information about the decisions made by the research team throughout the research process was documented to enhance the dependability and confirmability of the study [ 45 ]. This audit trail included descriptive interview notes, reflexive notes, methodological notes, and analytical notes. The development of reflexive notes was encouraged by sustaining transparent communication with the research team, which was stimulated because one research member was not familiar with occupational health, two research members were not a nurse, and one research member only had experience in the nursing profession in Switzerland [ 52 ]. Furthermore, the interviewer with experience in emergency nursing reflected on his personal values, opinions, and experiences, which cultivated awareness [ 43 ]. The audit trail also included a thick description of the setting, sample, and observations, supporting the transferability of the results. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were implemented to enhance the quality of the reported data [ 54 ].

Participants

The sample consisted of 37 CCNs, of which 27 CCNs participated in one of the six focus groups and ten CCNs could not participate due to organisational difficulties. Of those 27 CCNs, six were male and 21 were female, with a mean age of 36.07 years. Most CCNs worked in the ED (55.55%), with 77.78% of all included CCNs working full-time. Further sociodemographic characteristics of the CCNs are shown in Table 2 .

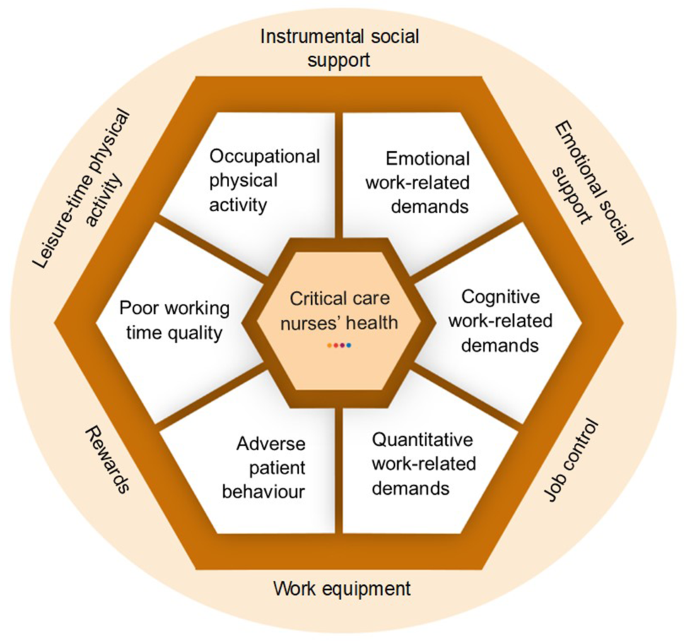

The interrelated categories

During iterative development, the influence of work-related demands on the participants’ health and mitigating strategies were identified. While being employed at a CCN ward, participants were continuously exposed to OPA, emotional, cognitive, and quantitative work-related demands, adverse patient behaviour, and poor working time quality. Exposure to such work-related demands was perceived as harmful and could lead to physical, mental, and psychosomatic complaints and increased turnover intention. Participants sought to mitigate the influence of work-related demands on their health by relying upon social support, job control, work equipment, rewards, and leisure-time physical activity. The results are outlined in the conceptual framework (Fig. 1 ). The central hexagon symbolises the consequences on CCNs’ health by surrounding work-related demands. The outer circle illustrates the applied strategies to mitigate adverse health outcomes.

Conceptual framework inspired by the Job Demand-Control-Support model [ 34 ], Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 38 ], and EWCS [ 48 ]

The structuring of the results was inspired by the Job Demand-Control-Support model [ 34 ], the Effort-Reward Imbalance model [ 38 ], and the EWCS [ 48 ], and supported with exemplar citations referring to the specific participants along with the focus groups they belonged to (FG-P) [ 46 ].

- Work-related demands

Participants experienced continuous exposure to OPA inside the hospital and during prehospital physician-staffed emergency care interventions. The included ED nurses were exposed to less OPA during the morning shift than ICU and stroke unit nurses. The most reported types of OPA were forward bending and isometric neck postures, prolonged standing, and long-distance walking. Forward bending and isometric neck postures were frequently required in various tasks performed, such as resuscitating, plastering, carrying heavy emergency coffers, tilling heavy patients in ambulance stretchers, and caring for intubated patients:

For example applying a plaster, holding up a leg with one arm and your back being curved, I have already had instances where the day after I thought: ‘I had to hold up a leg of 50 kilos which made my arm hurt the day after’. (FG3-P3)

Emotional work-related demands

Participants indicated the resuscitation of a child or family member, severe trauma victims, the announcement of cancer diagnosis to patients, and the high mortality rate as emotionally demanding:

I have seen things during the COVID that I never want to see again. I found that terrible… Yes (…), that feeling of powerlessness. You had to go through it. How many people died alone? I held their hands, but I stood there alone in my alien outfit. Then you have to call the family and tell them that you didn’t leave them alone. Those family members started to cry and I cried with them. I have apologised for that… I found that a very heavy period, those first two months of COVID. In addition, those older persons who arrived and said: ‘You do not have to give the oxygen to us, give it to the younger persons’, and after two hours they were dead. (FG4-P4)

In addition, the quality of management by supervisors was identified as a significant work-related demand among participants, as they reported feeling undervalued and unsupported, as well as experiencing a lack of empathy of their supervisors. Multiple CCNs claimed that the high number of telephone calls from their supervisors to provide shift coverage during off-job time contributed to this perceived poor management quality. FG1 and FG2 participants added that they felt the sense of being controlled by their supervisors via electronic patient records or checklists. The need for resilience, the changing work environment, and the lack of decision authority were further mentioned as significant demands in their role:

They ask for your opinion when it has already been determined. That is something that often happens to us. They already decided on something and then asked us for the show like: ‘How do you think about it?’, but our opinion does not matter anymore. (FG3-P3)

Furthermore, the adverse social behaviour from colleagues was cited as emotionally demanding by several participants. In particular, participating CCNs reported that interpersonal conflicts, such as working with nursing students, inexperienced colleagues or colleagues with whom the participants had a less good connection, contributed to an increased interdependency and the need to control the delivered care:

You have colleagues you get completely stressed out by… Yes, because the way of working is completely different, that you cannot relate to them, that you cannot do anything right for them, whereas you have other colleagues where you feel each other. (FG4-P1)

Finally, participants experienced a demand to perform without the ability to schedule a break and to be present at work during an illness because of their loyalty to colleagues:

Recently, a colleague arrived with a kidney stone. She sat in the kitchen with an infusion of analgesics and started to work an hour and a half later. (FG1-P4)

Cognitive work-related demands

Participants reported feeling highly vigilant throughout their shifts, especially when attending to unplanned care for critically ill patients. This required hypervigilance, combined with a lower presence of physicians, increasing their sense of responsibility. In addition, FG3 participants expressed being overwhelmed by the high amount of auditory stimulation they were exposed to:

In the ICU, I do have more stress because of the responsibility in comparison with the ED. In the ED, the emergency physicians will do many things by themselves, whereas in the ICU, I am expected to do it by myself. In the ICU, you also have a lot more critical patients than in the ED, because in the ED, sometimes you have a lot of geriatrics, but there is nothing critical about it. Whereas in the ICU, if you have an unstable patient, you have to think and reason continuously. Then, again, that is tougher, the psychological aspect. (FG4-2)

Quantitative work-related demands

Participants perceived the high work pace combined with telephone-related workflow interruptions, caused by managing the chaotic CCN ward and processing the high amount of medical orders, as harmful to their health. Furthermore, participating CCNs considered the need to carry out double work and inefficient work as significant demands in their role. As a consequence, multiple CCNs stated that more OPA was performed due to a lack of instrumental social support from colleagues:

Sometimes you feel like you are behind the times. You have to do this and that and that and that. You have continuously, you are faced with something that is not feasible of care as you have been taught. In practice, that is not feasible. This is then shifted on a maximum of pressure (…). (FG4-P3)

Adverse patient behaviour

Participants reported experiencing feelings of incongruence and dissatisfaction while providing care to self-referred non-urgent, dissatisfied, disrespectful, or aggressive patients:

I sometimes feel unsafe, yes. Especially in the ED, very unsafe… Yes, I am roused and stressed. I put it away. I do not show it externally because I do not want the patient to realise this. Internally, this is something that eats you up. I feel I am tachycardic then. (FG4-P2)

Poor working time quality

Participants highlighted the atypical working times as demanding due to working full-time in rotating shifts, on holidays, and during weekends:

Those mixed evening shifts, morning shifts, night shifts, and day shifts… Yes, I stopped working full-time here because I could no longer cope with it. (FG4-P3)

Furthermore, the highly commanded flexibility and poor working time arrangements were mentioned as significant work-related demands due to keeping up with all the refresher courses during off-job time, assisting in other nursing wards, dealing with unpredictable work schedules, and providing shift coverage when colleagues call in sick:

I got a call an hour later from my nursing supervisor asking if I could work another night shift. However, I said: ‘It is my non-working weekend and again it is during my non-working weekend that I have to do a night shift’. Again, I was justifying myself and I thought: ‘Why am I doing that?’. They know my weaknesses and you gave in to one [supervisor], but the other one [supervisor] is also trying because maybe you will also give in to him. (FG5-P1)

Consequences of work-related demands

Physical complaints.

Participants reported experiencing musculoskeletal disorders, particularly after increased exposure to OPA during busy shifts. Multiple CCNs mentioned the most intense pain in the lower and upper back, neck, shoulders, knees, hips, or bilateral wrists. FG2 and FG3 participants also experienced inflammation in their feet, lateral epicondylitis, and restless legs at a young age:

I have never, in the beginning, I did not suffer so much from that, but recently, I started having such restless legs from time to time <<< laughs>>>. In addition, then I think: ‘Oh so embarrassing because you are only 25 or 26 years old’. (FG3-P4)

However, several participants suggested that they had developed musculoskeletal disorders more easily due to OPA compared to leisure-time physical activity. This distinction was attributed to the fact that OPA involves prolonged exposure to less intense physical activity and leisure-time physical activity involves shorter exposure to more intense physical activity:

The physical work is more chronic (…), walking (…), or your arms or your back being strained… Whereas when you exercise that is very intense (…), your arms or your legs that you are training. (FG2-P3)

Furthermore, FG4 participants experienced an increased risk of developing urinary disorders in terms of urinary tract infections and kidney stones. This increased risk was attributed to the lack of opportunities to drink while working and unhealthy toileting behaviours, such as delayed voiding while facing a high work pace. Moreover, participants stated that their rotating shift work and atypical working times led to irregular and unhealthy eating patterns, resulting in unintentional weight gain:

I eat chips with a mandarin and a sandwich with chocolate, and minced meat. (FG3-P4)

Last, participants reported that they had developed impaired sleep quantity in terms of insomnia, shortened or prolonged sleep duration, and increased sleep disturbances, which were probably caused by circadian rhythm disruption due to shift work:

Yeah, especially if I had to switch from night to day rhythm. I was nauseous, intolerant, restless, rushed, unable to sleep, lying awake, not finding rest, being hungry when not being hungry. (FG4-P3) .

Mental complaints

Participants mentioned experiencing challenges in detaching mentally from patient-related stressful situations, particularly when children or family members were involved. Further difficulties in detaching from work were attributed to the high number of consecutive working days, the changing work environment, the challenging weekend schedule/shift, and the considerable level of flexibility required of CCNs. Participating CCNs expressed that this lack of detachment contributed to their impaired sleep health, emotional exhaustion, concentration disorders, work-family interference, and alcohol consumption:

I often need something like alcohol to just, truly, detach for a while <<< sighs>>>. My partner shares in the blows, but you are so overwhelmed at work and you come home with nine emails, a message from that one and a message from that one. On your day off again those emails, again those telephone calls, again… (FG5-P2)

In addition, participants reported that they experienced work-related stress and more intense perceptions of OPA due to poor management quality, adverse social behaviour from colleagues, and working with nursing students. Multiple CCNs added that the refresher courses during off-job time, adverse patient behaviour, and the reported shortcomings in providing the best possible care to patients contributed to their perceived work-related stress, likely resulting in personal dissatisfaction, moral distress, carry over into their personal lives, and increased turnover intention:

That satisfaction is completely overshadowed by the workload and the unsafe atmosphere at the ED. A stroke patient is located in the hallway and a person with epilepsy is located in the hallway, I am not satisfied when I come home. I just think: ‘No one died because of me in my care zone’. (FG5-P2)

Furthermore, participants tended to experience feelings of agitation during exclusion from the multidisciplinary decision-making processes and due to the lack of social support from physicians and the confrontation with dissatisfied patients:

We also do not understand why nurses were never involved in the development of patient rooms. I was part of the project group and when I measured everything and said it would not work for that, I got the reply: ‘Sorry, but it is too late, the rooms are already made and you cannot change that anymore’. (FG6-P4)

In addition, participants perceived emotional exhaustion, which could lead to personality changes and reduced marital and life satisfaction:

I do not know what all of you think about that, but everyone is sad at work. I feel that about myself too. (FG6-P2)

Moreover, participants reported experiencing work-family interference and attributed this to the considerable level of flexibility required, the nature of shift work, and the presence of patient-related stressors. Because of this continuous interference, the included CCNs were not able to take care of their children, perform tasks at home, and spend time with family. This work-family interference caused work-related stress, emotional exhaustion, concentration disorders, impaired marital satisfaction, and a reduced perceived work ability among participants:

So I also stopped working night shifts because of the work-life imbalance. From the moment I had my third child, I said: ‘This is no longer possible’. This caused tension in all possible areas, and then you have to make a choice and say that your private life comes first. It is almost not feasible to work full-time at the pace we work and in the circumstances we work. It is almost not feasible. (FG3-P1)

Finally, participants expressed being subject to social isolation as a result of their demanded flexibility, shift work, and unpredictable work schedules:

Yes, for example, I can no longer take dance classes because it is at a particular hour, and due to irregular shifts, I cannot guarantee that I can follow the class every week. So yes, too bad, but I cannot do my hobby anymore that I love to do. (FG3-P2)

Psychosomatic complaints

Participants stated that the experienced emotional exhaustion and work-related stress led to unintentional weight loss, increased muscle tension, and migraine:

I notice from myself that due to the emotional burden at work, I am starting to have physical complaints. For example, migraine, um yes, always being so tired, extremely losing weight, not being able to gain weight. (FG5-P1)

Moreover, multiple participants expressed the physical effort of OPA and leisure-time physical activity as comparable, but the lack of decision authority and satisfaction that comes with OPA increased their risk of developing prolonged fatigue and emotional exhaustion, contributing to physical exhaustion:

I can spend a whole day in my garden doing heavy work, then I come in [inside home] and I feel so energetic, fulfilled, and relaxed. However, when I come home from work, I feel so empty and drained of energy… The mindset here is already different. It [gardening] is also not an obligation. The work in the ED is an obligation… I can also feel that [physical activity during gardening] in my back and muscles, but still, I am not tired. (FG4-P3)

Furthermore, repetitive exposure to work-related stress was seen by the participants as a main factor in developing heart palpitations and tachycardia:

The moment I had tachycardia at triage due to enormous stress, no one cared from the physicians, except my two colleagues who then did take care of me. (FG5-P1)

Additionally, participants experienced reduced sleep quality, which was attributed to work-related stress, emotional exhaustion, and lack of detachment. In particular, the participating CCNs faced excessive daytime sleepiness and nightmares:

I went for a blood draw last week because my girlfriend said: ‘You should go for a blood draw because you are always tired, you always sleep around the clock and you would take another afternoon nap’. However, yes, everything was normal so the cause is probably my work. (FG5-P2)

Last, participants reported that they had developed concentration disorders likely caused by work-related stress, prolonged fatigue, emotional exhaustion, and lack of detachment, increasing their risk of traffic accidents:

I also nearly drove through a red light once. I had three to four prehospital physician-staffed emergency care interventions during one night and I was thinking of (…), anyways, I had to hit my brakes suddenly. (FG1-P1)

Turnover intention

Participants stated that they tended to leave their CCN ward due to the high work pace, unsafe working conditions, work-family interference, and lack of social support from their supervisors:

I have been in it [CCN profession] for more than 20 years now and I always said: ‘If it works out, I will stay in it until my retirement’… That you can stay employed until your retirement, I do not think that is possible anymore because of the current workload. (FG5-P5)

Mitigating strategies

Social support.

Participants reported instrumental social support from colleagues as a strategy to prevent the physical burden when dealing with OPA and to alleviate cognitive overload when coordinating a chaotic CCN ward: