Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

119 Fishing Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Fishing is a timeless pastime that has been enjoyed by people all over the world for generations. Whether you are an experienced angler or a beginner looking to learn more about the sport, there are countless topics related to fishing that can be explored through essays. In this article, we will provide you with 119 fishing essay topic ideas and examples to help inspire your writing.

- The history of fishing

- The benefits of fishing for mental health

- Fishing techniques for beginners

- The impact of climate change on fishing

- The best fishing spots around the world

- The cultural significance of fishing in different countries

- How to properly care for and clean fishing equipment

- The role of fishing in conservation efforts

- The ethics of catch and release fishing

- The economic impact of the fishing industry

- The health benefits of eating fish

- The importance of fishing regulations and limits

- The art of fly fishing

- The dangers of overfishing

- The role of technology in modern fishing practices

- The best bait for different types of fish

- The psychology of fishing: why do people enjoy it?

- The impact of pollution on fish populations

- The challenges facing small-scale fishermen

- The history of commercial fishing

- The impact of invasive species on native fish populations

- The benefits of fishing for children

- The best fishing gear for different types of fishing

- The role of fishing in sustainable food systems

- The connection between fishing and spirituality

- The impact of dams and other man-made structures on fish habitats

- The cultural traditions of fishing in indigenous communities

- The future of fishing: how will it evolve in the coming years?

- The benefits of fishing as a form of exercise

- The impact of recreational fishing on fish populations

- The best fishing destinations for a family vacation

- The environmental benefits of fishing

- The role of fishing in local economies

- The impact of overfishing on marine ecosystems

- The best fishing techniques for catching different types of fish

- The benefits of fishing for stress relief

- The impact of commercial fishing on local communities

- The role of fishing in sustainable seafood sourcing

- The best fishing apps for anglers

- The impact of climate change on fish migration patterns

- The benefits of catch and release fishing

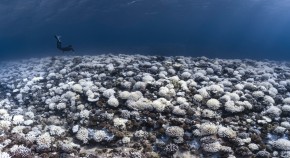

- The impact of fishing on coral reefs

- The best fishing techniques for catching trophy fish

- The benefits of fishing for physical health

- The impact of fishing on endangered species

- The role of fishing in wildlife conservation efforts

- The best fishing destinations for a solo trip

- The impact of fishing on river ecosystems

- The benefits of fishing for team building

- The impact of fishing on water quality

- The role of fishing in disaster relief efforts

- The best fishing techniques for catching fish in different seasons

- The benefits of fishing for community engagement

- The impact of fishing on coastal communities

- The role of fishing in traditional medicine

- The best fishing destinations for a romantic getaway

- The impact of fishing on aquatic plants

- The benefits of fishing for personal growth

- The role of fishing in cultural celebrations

- The impact of fishing on bird populations

- The best fishing techniques for catching fish in different weather conditions

- The benefits of fishing for team bonding

- The impact of fishing on aquatic insects

- The role of fishing in disaster preparedness

- The best fishing destinations for a weekend getaway

- The impact of fishing on freshwater ecosystems

- The benefits of fishing for mental resilience

- The role of fishing in historical events

- The impact of fishing on amphibian populations

- The best fishing techniques for catching fish in different types of water bodies

- The benefits of fishing for personal fulfillment

- The impact of fishing on reptile populations

- The role of fishing in religious ceremonies

- The impact of fishing on mammal populations

- The best fishing destinations for a budget-friendly trip

- The benefits of fishing for social connection

- The impact of fishing on invertebrate populations

- The role of fishing in cultural preservation

- The impact of fishing on plant populations

- The best fishing techniques for catching fish in different types of habitats

- The benefits of fishing for environmental awareness

- The role of fishing in historical preservation

- The impact of fishing on aquatic ecosystems

- The benefits of fishing for mental well-being

- The impact of fishing on aquatic food chains

- The role of fishing in community building

- The impact of fishing on aquatic biodiversity

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Fisheries articles from across Nature Portfolio

Fisheries are social, biological and geographical objects involved in producing fish for human consumption. They are usually united by a common geographical area, catch technique and/or target species, and fisheries science is the study of factors affecting catch and stock sustainability.

Latest Research and Reviews

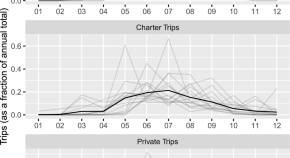

Resident marine sportfishing effort in the United States varied non-monotonically with COVID policy stringency

- Alexander Gordan

- David Carter

- Christopher Liese

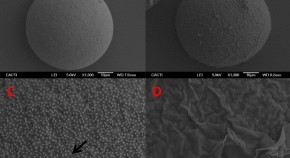

Ultrastructural examination of cryodamage in Paracentrotus lividus eggs during cryopreservation

- J. Troncoso

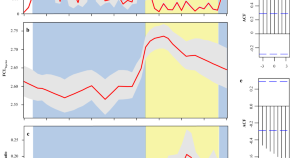

Anchovy boom and bust linked to trophic shifts in larval diet

A characteristic of costal-pelagic fishes is their large population size fluctuations, yet the drivers remain elusive. Here, the authors analyze a 45-year timeseries of nitrogen stable isotopes measured in larvae of Northern Anchovy and find that high energy transfer efficiency from the base of the food web up to young larvae confers high survival and recruitment to the adult population.

- Rasmus Swalethorp

- Michael R. Landry

- Andrew R. Thompson

Nursery origin of yellowfin tuna in the western Atlantic Ocean: significance of Caribbean Sea and trans-Atlantic migrants

- Jay R. Rooker

- Michelle Zapp Sluis

- R. J. David Wells

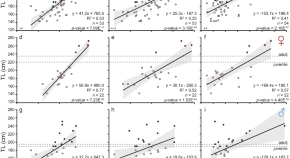

Shark teeth zinc isotope values document intrapopulation foraging differences related to ontogeny and sex

Sex- and ontogeny-related differences in diet and habitat use of endangered sand tiger sharks from Delaware Bay revealed by analysis of shark teeth zinc isotope values.

- Jeremy McCormack

- Molly Karnes

- Sora L. Kim

Artificial reefs reduce the adverse effects of mud and transport stress on behaviors of the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus

- Fangyuan Hu

- Huiyan Wang

News and Comment

How my research is putting blue crab on the menu in Croatia

Neven Iveša investigates the invasive species in the Adriatic Sea, and works out how to lessen its impact.

- Jack Leeming

China’s Yangtze fish-rescue plan is a failure, study says

Researchers have debated the best management plan for highly endangered fish species since the 1980s.

- Xiaoying You

Seafood access in Kiribati

- Annisa Chand

Climate policy must integrate blue energy with food security

- Jiangning Zeng

Forecast warns when sea life will get tangled in nets — one year in advance

Computational model uses sea surface temperatures to predict when whales and turtles are likely to get stuck in fishing gear.

- Carissa Wong

With the arrival of El Niño, prepare for stronger marine heatwaves

Record-high ocean temperatures, combined with a confluence of extreme climate and weather patterns, are pushing the world into uncharted waters. Researchers must help communities to plan how best to reduce the risks.

- Alistair J. Hobday

- Michael T. Burrows

- Thomas Wernberg

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Lifestyle & Interests — Fishing

Essays on Fishing

Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, fishing that's more rhan a sport: the reel sisters, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Life, Fishing and Friendship: a Review of The Reel Sisters

The main knowledge about trout fishing, the reel sisters: fly fishing that brings people together, personal narrative essay: fishing with my idol scott martin, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Benefits of Fishing for College Students

Relevant topics.

- Bucket List

- Being a Good Person

- Comfort Zone

- Watching TV

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Advertisement

Fishing as a livelihood, a way of life, or just a job: considering the complexity of “fishing communities” in research and policy

- Original Research

- Published: 10 August 2022

- Volume 33 , pages 265–280, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Claudia E. Delgado-Ramírez 1 ,

- Yoshitaka Ota 2 &

- Andrés M. Cisneros-Montemayor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4132-5317 3

1275 Accesses

3 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

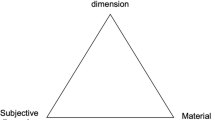

In the scientific literature on fisheries, the concept of community is often used broadly to indicate a place-based group whose members are dedicated to fisheries and have relatively homogeneous economic, social, and cultural interests. However, this categorical perspective to scope a “fishing community” is not necessarily an insightful approach to explore diverse social relationships with the marine environment, fishwork, and management in a practical context, and risks mismatches with science-based recommendations for management and policy. Drawing from ethnographic work, we highlight different historical and cultural dynamics from four case studies from fisheries in northwest Mexico. We identify key factors that help contextualize fishwork relationships, related to the importance of fishing practices on worldviews, daily routines, and income. These are used to derive three configurations (livelihood, way of life, and job) that describe and give analytical content to the notion of these fishing communities. Our use of a typology is not intended to generalize them or provide universal categories, but rather to convey to a broad range of fisheries scientists the importance of considering social contexts in the places in which we work and learn, and a set of guiding questions that may help in this regard. Contextualizing the importance of historical and cultural factors in scoping community units beyond occupational or geographical characteristics is essential for identifying and addressing (in)equitable processes and outcomes in fisheries sectors, research, and management.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social wellbeing, values, and identity among Caiçara small-scale fishers in southeastern Brazil

Reflections on Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries: Implications for Research, Policy and Management

The Socio-Cultural Impact of Industry Restructuring: Fishing Identities in Northeast Scotland

Data availability.

The information generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Amit, V. (2002). Realizing community. Concepts, social relationships and sentiments (V. Amit (Ed.); 1a ed.). Taylor & Francis e-Library

Ayers A, Kittinger J (2014) Emergence of co-management governance for Hawai‘i coral reef fisheries. Glob Environ Chang 28:251–262

Article Google Scholar

Basurto X (2006) Commercial diving and the Callo de Hacha fishery in seri territory. J Southwest 2(Summer):189–209

Google Scholar

Beaudreau AH, Levin PS (2014) Advancing the use of local ecological knowledge for assessing data-poor species in coastal ecosystems. Ecol Appl 24(2):244–256

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Blázquez AP, Palacios FF (2016) Participación de las mujeres en la pesca: nuevos roles de género, ingresos económicos y doble jornada. Sociedad y Ambiente 1(9):121–141

Brookfield K, Gray T, Hatchard J (2005) The concept of fisheries-dependent communities: a comparative analysis of four UK case studies: Shetland, Peterhead, North Shields and Lowestoft. Fish Res 72(1):55–69

Carter C, Garaway C (2014) Shifting tides, complex lives: the dynamics of fishing and tourism livelihoods on the Kenyan Coast. Soc Nat Resour 27(6):573–587

Cisneros-Montemayor A, Cisneros-Mata M (2018) A medio siglo de manejo pesquero pesquero en el noroeste de México, el futuro de la pesca como sistema socioecológico. Relaciones Estudios De Historia y Sociedad 153:99–127

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Zetina-Rejón MJ, Espinosa-Romero MJ, Cisneros-Mata MA, Singh GG, Melo FFR (2020) Evaluating ecosystem impacts of data-limited artisanal fisheries through ecosystem modelling and traditional fisher knowledge. Ocean Coast Manag 195:105291

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Moreno-Báez M, Reygondeau G, Cheung WWL, Crosman KM, González-Espinosa PC, Lam VWY, Oyinlola MO, Singh GG, Swartz W, Zheng CW, Ota Y (2021) Enabling conditions for an equitable and sustainable blue economy. Nature 591:396–401

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Clay PM, Olson J (2008) Olson defining “fishing communities”: vulnerability and the Magnuson-Stevens fishery conservation and management act. Hum Ecol Rev 15(2):143–160

Cline TJ, Schindler DE, Hilborn R (2017) Fisheries portfolio diversification and turnover buffer Alaskan fishing communities from abrupt resource and market changes. Nat Commun 8(1):14042

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

De La Torre-Valdez HC, Sandoval-Godoy SA (2015) Ciencia Pesquera Resiliencia socio-ecológica de las comunidades ribereñas en la zona Kino-Tastiota del Golfo de California Estudios socioeconómicos. Ciencia Pesquera 23(1):53–71

Delgado, C., Ota, Y., & Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M. (in press). La pesca artesanal en América Latina y el Caribe: hallazgos a la luz de una revisión documental

Delgado, C. (2009). Los pescadores seri, yaqui y kineños: un estudio comparativo sobre la inserión del capitalismo en tres comunidades pesqueras del Golfo de California. Chihuahua: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia. https://www.scribd.com./doc/30647558/TESIS-CLAUDIA-DELGADO#scribd

Delgado, C. (2019). Buceando erizo de mar. Etnografía biocultural de un sistema de manejo pesquero en Baja California. (1a ed.). Secretaría de Cultura, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, EAHNM

Delgado, C. (2021). Entre jaiba, camarón, sardina y erizo: mujeres en la producción pesquera y la reproducción social en el noroeste de México. Revista Latinoamericana de Antropología del Trabajo, No. 12, CEIL, CONICET, CIESAS, http://id.caicyt.gov.ar/ark:/s25912755/29ldpf9rj

Espinoza, A., Bravo, L., Serrano, S., Ronsón, J., Ahumada, M., Cervantes, P., Robles, E., Fuentes, P., Guerra, R. & Gallardo, M. (2011). La diversidad étnica como factor de planeación pesquera artesanal: chontales, huaves y zapotecas del Istmo de Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, México. Pescadores en América Latina y El Caribe. Espacio, Población, Producción y Política; Alcalá, G. (Edit.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Facultad de Ciencias. Unidad de Multidisciplinaría de Docencia e Investigación Social, pp. 167–216

Fernández-Rivera Melo F, Suárez-Castillo A, Amador-Castro I, Gastélum-Nava E, Espinosa-Romero M, Torre J (2018) Bases para el ordenamiento de la pesca artesanal con la participación del sector productivo en la Región de las Grandes Islas, Golfo de California. Ciencia Pesquera, Aviso De Arribo 26(1):81–100

Finkbeiner EM, Bennett NJ, Frawley TH, Mason JG, Briscoe DK, Brooks CM, Ng CA, Ourens R, Seto K, Switzer Swanson S, Urteaga J (2017) Reconstructing overfishing: moving beyond Malthus for effective and equitable solutions. Fish Fish 18(6): 1180–1191

El Correo Fronterizo. 2018. Entrevista con la Dra. Araceli Almaraz. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. https://www.colef.mx/estemes/historia-embargo-atunero-y-actividades-pesqueras-en ensenada/#:~:text=consecuencias%20para%20Ensenada%3F,Dra.,para%20la%20regi%C3%B3n%20de%20Ensenada.

Geertz C (2003) La Interpretación de las Culturas. Gedisa, Barcelona, p 387

Grey J (2002) Community as place-making. Ram auctions in the Scottish borderland. In: Amit V (ed) Realizing Community. Concepts, social relationships and sentiments. Routledge, United Kingdom

Hanh TTH (2021) Why are fisheries agencies unable to facilitate the development of alternative livelihoods in small-scale fisheries and aquaculture in the global South? A case study of the Tam Giang lagoon, Viet Nam. Mar Policy 133:104778

Hernández, M. (2018). El pueblo comca’ac y su proyecto de futuro. La Jornada del Campo, No. 133, México. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2018/10/20/cam-pueblo.html

INEGI (2020). Censo de Población y Vivienda. México

Jentoft S, Chuenpagdee R (2009) Fisheries and coastal governance as a wicked problem. Mar Policy 33:553–560

Jentoft S, Chuenpagdee R, Barragán-Paladines M, Franz N (2017) The small-scale fisheries guidelines: global implementation. Springer, New York, NY

Book Google Scholar

Jiménez V, López-Sagástegui C, Cota J, Mascareñas I (2018) Comunidades costeras del noroeste mexicano haciendo ciencia. Relaciones Estudios De Historia y Sociedad 153:129–165

Lavin MF, Marinone SG (2003) An overview of the physical oceanography of the Gulf of California. In: Velasco-Fuentes OU, Sheinbaum J, Ochoa J (eds) Nonlinear processes in geophysical fluid dynamics. Springer, Cham, pp 173–204

Chapter Google Scholar

Luque, D. & Doode, S. (2009). Los comcáac (seri): hacia una diversidad biocultural del Golfo de California y estado de Sonora, México. Estudios Sociales (Hermosillo, Son.), 17(SPE.), pp 273–301

Marsvati A (2004) Qualitative research in sociology. An introduction. SAGE Publications, London, p 169

Mollett S (2014) A modern paradise: Garifuna land, labor, and displacement-in-place. Lat Am Perspect 41(6):27–45

Ochoa, A. (1988). Antropología de la gente de mar: Los pescadores de sardina en Ensenada, Baja California. (1a ed.). Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia - INAH

Ota Y, Just R (2008) Fleet sizes, fishing effort and the ‘hidden’ factors behind statistics: an anthropological study of small-scale fisheries in UK. Mar Policy 32(3):301–308

Padilla L (2016) Diversificación sectorial y proyección internacional del municipio de Ensenada, México. Revista Transporte y Territorio 15:241–273. https://doi.org/10.34096/rtt.i15.2860

Palacios-Abrantes J, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Cisneros-Mata MA, Rodríguez L, Arreguín-Sánchez F, Aguilar V, Domínguez-Sánchez S, Fulton S, López-Sagástegui R, Reyes-Bonilla H, Rivera-Campos R (2019) A metadata approach to evaluate the state of ocean knowledge: Strengths, limitations, and application to Mexico. PLoS One 14(6): e0216723

Pinkerton E (2017) Hegemony and resistance: disturbing patterns and hopeful signs in the impact of neoliberal policies on small-scale fisheries around the world. Mar Policy 80:1–9

Power NG, Norman ME, Dupré K (2014) “The fishery went away” The impacts of long-term fishery closures on young people’s experience and perception of fisheries employment in Newfoundland coastal communities. Ecol Soc 19(3):6

Sahlins M (1972) Stone age economics. Aldine de Gruyter, New York

Schuhbauer A, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Chuenpagdee R, Sumaila U (2019) Assessing the economic viability of small-scale fisheries: an example from Mexico. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 617–618:365–376

Sene-Harper A, Matarrita-Cascante D, Larson LR (2019) Leveraging local livelihood strategies to support conservation and development in West Africa. Environ Dev 29:16–28

Singh GG, Harden-Davies H, Allison EH, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Swartz W, Crosman KM, Ota Y (2021) Will understanding the ocean lead to “the ocean we want”? Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(5):e2100205118

Song A, Scholtens J, Barclay K, Bush S, Fabinyi M, Adhuri D, Haughton M (2020) Collateral damage? Small-scale fisheries in the global fight against IUU fishing. Fish Fish 21:831–843

Syed S, Borit M, Spruit M (2018) Narrow lenses for capturing the complexity of fisheries: a topic analysis of fisheries science from 1990 to 2016. Fish Fish 19:643–661

Tjora, A. & Scambler, G. (2020). Communal Forms. A Sociological Exploration of Concepts of Community (1a ed.). Routledge

Trápaga I (2018) La Comunidad, una revisión al concepto antropológico. Revista De Antropología y Sociología, Virajes 20(2):161–182. https://doi.org/10.17151/rasv.2018.20.2.9

Velázquez C (2007) Japoneses y pesca en la península californiana, 1912–1941. México y La Cuenca Del Pacífico 29:73–90. https://doi.org/10.32870/mycp.v10i29.310

Yin RK (1994) Investigación sobre Estudios de Casos. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, Diseño y Métodos, p 35

Zapata F (1977) Enclaves y sistemas de relaciones industriales en América Latina. Rev Mex Sociol 39(2):719. https://doi.org/10.2307/3539782

Download references

Acknowledgements

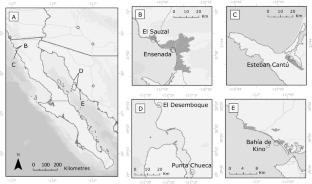

The authors acknowledge support from the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center at EarthLab, University of Washington. We thank Dr. Pedro González-Espinosa for his help preparing Figure 1 .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Anthropology and History of Northern Mexico, National Institute of Anthropology and History, Chihuahua, Mexico

Claudia E. Delgado-Ramírez

Ocean Nexus, School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, University of Washington, Seattle, USA

Yoshitaka Ota

Ocean Nexus, School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada

Andrés M. Cisneros-Montemayor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, and Writing of the Original and Revised Manuscript; CEDR performed the Investigation; AMCM and YO contributed to Supervision, Project Administration, and Funding Acquisition.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrés M. Cisneros-Montemayor .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Delgado-Ramírez, C.E., Ota, Y. & Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M. Fishing as a livelihood, a way of life, or just a job: considering the complexity of “fishing communities” in research and policy. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 33 , 265–280 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09721-y

Download citation

Received : 06 February 2022

Accepted : 20 July 2022

Published : 10 August 2022

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-022-09721-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Artisanal fisheries

- Local communities

- Indigenous communities

- Livelihoods

- Social-ecological systems

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Writing Prompts about Fishing

- 🗃️ Essay topics

- ❓ Research questions

- 📝 Topic sentences

- 🪝 Essay hooks

- 📑 Thesis statements

- 🔀 Hypothesis examples

- 🧐 Personal statements

🔗 References

🗃️ essay topics about fishing.

- The benefits of fishing for mental health and stress reduction.

- The impact of climate change on fishing communities.

- The ethics of catch and release fishing.

- The economic importance of recreational fishing.

- The history of fly fishing and its evolution.

- The impact of overfishing on marine ecosystems.

- The role of fishing in traditional cultural practices.

- Fishing industry: the fight for gender equality.

- The impact of fishing regulations on the fishing industry.

- The benefits of fishing for physical health and wellness.

- The future of sustainable fishing practices.

- The science of fish behavior and how it informs fishing techniques.

- The cultural significance of fishing in different regions of the world.

- The importance of fishing as a means of food security.

- The impact of commercial fishing on the environment.

- The role of fishing in coastal tourism.

- The evolution of fishing gear and technology.

- The benefits and challenges of freshwater vs. saltwater fishing.

- The role of fishing in conservation efforts.

- The cultural and environmental impact of sport fishing tournaments.

- The impact of fishing on endangered species and biodiversity conservation.

❓ Fishing Essay Questions

- How does climate change affect fish populations and fishing communities?

- What is the impact of commercial fishing on the marine ecosystem?

- How can fishing regulations be designed to balance economic and environmental interests?

- What are the benefits of catch-and-release fishing for fish populations and ecosystems?

- What are the best practices for sustainable fishing in different regions of the world?

- How do fishing technologies, such as fish finders and underwater cameras, affect fish behavior and fishing success rates?

- What role does fishing play in food security for coastal communities?

- What are the economic benefits of recreational fishing for local communities?

- What is the relationship between fish consumption and human health?

- How can fishery management be improved to ensure the survival of endangered species and protect biodiversity?

- What are the ethical considerations involved in sport fishing tournaments?

- How does fishing culture vary across different regions of the world?

- How can traditional fishing practices be preserved and integrated into modern fishing practices?

- What impact do fishing regulations have on the cultural practices of fishing communities?

- How can fishing tourism be managed to balance economic development with environmental protection?

📝 Fishing Topic Sentences

- Fishing is not just a sport or hobby, but a valuable source of livelihood for millions of people around the world.

- The health benefits of fishing are numerous, ranging from stress reduction to physical exercise to improved nutrition.

- The impact of overfishing on marine ecosystems is a pressing concern that requires global cooperation and sustainable management practices.

🪝 Hooks for Fishing Paper

📍 anecdotal hooks on fishing for essay.

- I once caught a fish so big, I had to use my entire body weight to reel it in. I’m pretty sure the fish won the battle, but my friends still claim it was a tree branch.

- As a kid, my dad took me on my first fishing trip and I was so excited to finally catch something. I ended up catching a rubber boot and a plastic bottle. My dad said it was a good haul for environmental clean-up.

📍 Autobiography Hooks for Essay on Fishing

- As a young child, I would spend countless hours fishing with my grandfather, and those memories of time spent on the water continue to inspire my love for the sport today.

- From the first time I cast my line into the water as a teenager, I knew that fishing would become a lifelong passion and a source of solace during the most challenging moments of my life.

📍 Statistical Hooks on Fishing

- According to a recent study, the recreational fishing industry generates over $125 billion in economic output and supports over 800,000 jobs in the United States alone.

- Overfishing has led to a decline in global fish stocks, with approximately 34.2% of fish stocks being overexploited, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

📑 Top Fishing Thesis Statements

✔️ argumentative thesis examples about fishing.

- Despite its popularity as a leisure activity, recreational fishing can have negative impacts on fish populations and ecosystems and therefore should be subject to strict regulations to ensure sustainability.

- The global fishing industry has a responsibility to prioritize sustainable practices and conservation efforts in order to protect the health of our oceans and ensure the survival of fish species for generations to come.

✔️ Analytical Thesis on Fishing

- Although fishing can be a sustainable source of food and income for communities, overfishing and irresponsible fishing practices have led to the depletion of fish populations and the destruction of marine ecosystems, necessitating more responsible and sustainable management practices.

- The cultural significance of fishing varies across regions and communities, and understanding these cultural practices is crucial for designing effective fishing regulations and sustainable management practices that balance economic, environmental, and social interests.

✔️ Informative Thesis Samples about Fishing

- Recreational fishing is not only a popular pastime, but also an important source of economic growth and employment, and its sustainable management is crucial for the future of the industry.

- Overfishing is a pressing global issue that has led to the decline of fish populations and disrupted marine ecosystems, and effective conservation measures and sustainable fishing practices are necessary to mitigate its impact.

🔀 Fishing Hypothesis Examples

- Increased fishing regulations, such as size limits and catch quotas, will lead to improved fish populations and more sustainable fishing practices.

- The use of artificial lures in fishing will result in higher catch rates compared to natural bait due to their ability to mimic real prey and attract fish more effectively.

🔂 Null & Alternative Hypothesis about Fishing

- Null hypothesis: There is no significant difference in the catch rates of fish between anglers who use live bait and those who use artificial lures.

- Alternative hypothesis: Anglers who use artificial lures catch more fish than those who use live bait.

🧐 Examples of Personal Statement on Fishing

- Fishing has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember. It’s not just about catching fish, but also about being in nature and enjoying the peace and quiet. I’ve learned patience, respect for the environment, and the importance of sustainable practices through my experiences with fishing.

- Growing up near the coast, fishing has been an integral part of my life and family traditions. It has instilled in me a deep respect for the environment and a passion for sustainability, as I have witnessed the impact of overfishing on the marine ecosystem.

- The Fishing Industry as a Complex System

- The cross-national association between institutional imbalance, national culture, and illegal fishing

- Cruelty to Human and Nonhuman Animals in the Wild-Caught Fishing Industry

- Sustainability: A flawed concept for fisheries management?

- Safety risk assessment of fishing schemes

Cite this page

Select a referencing style

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

AssignZen. (2023, June 9). Writing Prompts about Fishing. https://assignzen.com/writing-prompts/fishing-essay-ideas/

"Writing Prompts about Fishing." AssignZen , 9 June 2023, assignzen.com/writing-prompts/fishing-essay-ideas/.

1. AssignZen . "Writing Prompts about Fishing." June 9, 2023. https://assignzen.com/writing-prompts/fishing-essay-ideas/.

Bibliography

AssignZen . "Writing Prompts about Fishing." June 9, 2023. https://assignzen.com/writing-prompts/fishing-essay-ideas/.

AssignZen . 2023. "Writing Prompts about Fishing." June 9, 2023. https://assignzen.com/writing-prompts/fishing-essay-ideas/.

AssignZen . (2023) 'Writing Prompts about Fishing'. 9 June.

Essays on Fishing

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Current advances and challenges in fisheries and aquaculture science.

Conflicts of Interest

- Cordova-de la Cruz, S.; Riesco, M.; Martínez-Bautista, G.; Calzada-Ruiz, D.; Martínez-Burguete, T.; Peña-Marín, E.; Álvarez-Gonzalez, C.; Fernández, I. Larval Development in Tropical Gar ( Atractosteus tropicus ) Is Dependent on the Embryonic Thermal Regime: Ecological Implications under a Climate Change Context. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- McBaine, K.; Hallerman, E.; Angermeier, P. Direct and Molecular Observation of Movement and Reproduction by Candy Darter, Etheostoma osburni , an Endangered Benthic Stream Fish in Virginia, USA. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sikora, L.; Mrnak, J.; Henningsen, R.; Van De Hey, J.; Sass, G. Demographic and Life History Characteristics of Black Bullheads Ameiurus melas in a North Temperate USA Lake. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mallet, D.; Olivry, M.; Ighiouer, S.; Kulbicki, M.; Wantiez, L. Nondestructive Monitoring of Soft Bottom Fish and Habitats Using a Standardized, Remote and Unbaited 360° Video Sampling Method. Fishes 2021 , 6 , 50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Miqueleiz, I.; Miranda, R.; Ariño, A.; Ojea, E. Conservation-Status Gaps for Marine Top-Fished Commercial Species. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 2. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rodríguez-Viera, L.; Martí, I.; Martínez, R.; Perera, E.; Estrada, M.; Mancera, J.; Martos-Sitcha, J. Feed Supplementation with the GHRP-6 Peptide, a Ghrelin Analog, Improves Feed Intake, Growth Performance and Aerobic Metabolism in the Gilthead Sea Bream Sparus aurata . Fishes 2022 , 7 , 31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Basto-Silva, C.; García-Meilán, I.; Couto, A.; Serra, C.; Enes, P.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Capilla, E.; Guerreiro, I. Effect of Dietary Plant Feedstuffs and Protein/Carbohydrate Ratio on Gilthead Seabream ( Sparus aurata ) Gut Health and Functionality. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 59. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Martínez-Antequera, F.; Barranco-Ávila, I.; Martos-Sitcha, J.; Moyano, F. Solid-State Hydrolysis (SSH) Improves the Nutritional Value of Plant Ingredients in the Diet of Mugil cephalus . Fishes 2022 , 7 , 4. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Batista, R.; Nobrega, R.; Schleder, D.; Pettigrew, J.; Fracalossi, D. Aurantiochytrium sp. Meal Improved Body Fatty Acid Profile and Morphophysiology in Nile Tilapia Reared at Low Temperature. Fishes 2021 , 6 , 45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Safari, O.; Sarkheil, M.; Shahsavani, D.; Paolucci, M. Effects of Single or Combined Administration of Dietary Synbiotic and Sodium Propionate on Humoral Immunity and Oxidative Defense, Digestive Enzymes and Growth Performances of African Cichlid (Labidochromis lividus ) Challenged with Aeromonas hydrophila . Fishes 2021 , 6 , 63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Hallerman, E.; Esteban, M.A.; Baldisserotto, B. Current Advances and Challenges in Fisheries and Aquaculture Science. Fishes 2022 , 7 , 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7020087

Hallerman E, Esteban MA, Baldisserotto B. Current Advances and Challenges in Fisheries and Aquaculture Science. Fishes . 2022; 7(2):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7020087

Hallerman, Eric, Maria Angeles Esteban, and Bernardo Baldisserotto. 2022. "Current Advances and Challenges in Fisheries and Aquaculture Science" Fishes 7, no. 2: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes7020087

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Fishing - Free Essay Examples and Topic Ideas

Fishing is an outdoor activity that involves catching fish using different techniques such as angling, netting, trapping or hand gathering. It can be done in various water bodies such as rivers, lakes, oceans, and even ponds. Fishing can be a leisure activity, a sport, or a means of livelihood. It is also a popular pastime that is enjoyed by people of all ages and skill levels. Fishing requires patience, concentration, and knowledge about different fish species, their habitats, and feeding habits. It is also a way of connecting with nature, enjoying the peacefulness of the environment and spending time outdoors.

- 📘 Free essay examples for your ideas about Fishing

- 🏆 Best Essay Topics on Fishing

- ⚡ Simple & Fishing Easy Topics

- 🎓 Good Research Topics about Fishing

- ❓ Questions and Answers

Essay examples

Essay topic.

Save to my list

Remove from my list

- Strombidae Protected Fisheries

- Fishing on the Susquehanna

- Hunting and Fishing

- Case Study, Nigeria. What are critical resources that has given Nigerian exporters a positional advantage?

- Alaska and The Decrease in The Number of Commercial Fishing-related Deaths

- Importance of Fishing

- Fishing trip

- Wintering Out and “Bye-Child” by Heaney

- Young’s Modulus of Fishing Lines

- New Zealand Ag Paper : Clint Jenks

- The Loss of the Aral Sea

- Anticipatory Socialization In Work

- North Korea

- Hunting vs. Fishing

- Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing

- Low Developed Regions

- Coastal Security of India and the Gom Recommendations International

- Never Forget Event in My Life

- An Automatically Learning andDiscovering Human Fishing

- The Effects of Illegal Fishing

- Pros and Cons of the Fishing Market

- Overfishing: When Humans Exhaust the Oceans

- Avi Bhaya Intro to Sociology Professor Colin Jerolmack

- The Narrator’s Quest for Trout Fishing in America

- The Sun Also Rises: the Fishing Trip

- Pro’s and Con’s to Exploitation of Natural Resources

- Ornamental Fishing in India

FAQ about Fishing

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Animals (Basel)

“But It’s Just a Fish”: Understanding the Challenges of Applying the 3Rs in Laboratory Aquariums in the UK

Simple summary.

Fish are widely used in research and some species have become important model organisms in the biosciences. Despite their importance, their welfare has usually been less of a focus of public interest or regulatory attention than the welfare of more familiar terrestrial and mammalian laboratory animals; indeed, the use of fish in experiments has often been viewed as ethically preferable or even neutral. Adopting a social science perspective and qualitative methodology to address stakeholder understandings of the problem of laboratory fish welfare, this paper examines the underlying social factors and drivers that influence thinking, priorities and implementation of fish welfare initiatives and the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) for fish. Illustrating the case with original stakeholder interviews and experience of participant observation in zebrafish facilities, this paper explores some key social factors influencing the take up of the 3Rs in this context. Our findings suggest the relevance of factors including ambient cultural perceptions of fish, disagreements about the evidence on fish pain and suffering, the language of regulators, and the experiences of scientists and technologists who develop and put the 3Rs into practice. The discussion is focused on the UK context, although the main themes will be pertinent around the world.

Adopting a social science perspective and qualitative methodology on the problem of laboratory fish welfare, this paper examines some underlying social factors and drivers that influence thinking, priorities and implementation of fish welfare initiatives and the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) for fish. Drawing on original qualitative interviews with stakeholders, animal technologists and scientists who work with fish—especially zebrafish—to illustrate the case, this paper explores some key social factors influencing the take up of the 3Rs in this context. Our findings suggest the relevance of factors including ambient cultural perceptions of fish, disagreements about the evidence on fish pain and suffering, the discourse of regulators, and the experiences of scientists and animal technologists who develop and put the 3Rs into practice. The discussion is focused on the UK context, although the main themes will be pertinent around the world.

1. Introduction

The relevance of human-animal interactions, relationships and bonds to laboratory animal welfare, robust animal-dependent science and ethics is widely acknowledged by practitioners, e.g., [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. How these are embedded in and reflective of wider social processes, relations and structures is also increasingly a matter of interest to social scientists, historians and ethicists, many of whom are also concerned to better understand how such broader societal issues shape the implementation and development of public policy and associated ethical frameworks, e.g., [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], including the 3Rs [ 12 , 13 ]. There is also thriving literature on the role of public opinion concerning the use of laboratory animals, much of which illustrates an interest in how species differences can mediate social attitudes and potentially structure policy priorities, e.g., [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. The case of the use of fish in regulated scientific research is a good example of this, but has seldom before been addressed for some partial exceptions, see [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Using the 3Rs as a point of entry, this paper adopts a qualitative social scientific perspective, highlighting social drivers that could be influencing thinking on, prioritization of and implementation of laboratory fish welfare.

In the United Kingdom and many other countries, fish have not historically qualified for sympathy because they were deemed too dissimilar to humans [ 22 ] (p. 177). Times have changed: following rising concerns about food fish sustainability, oceanic health, and the industrialization of both wild-capture fisheries and aquaculture, the ethics of human-fish relations in their different forms and locations have slowly become topics of both popular (e.g., [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]) and academic (e.g., [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]) criticism. Additionally, there has been an explosion of scientific interest in the cognitive abilities of fish and their capacity for emotional experiences, topics which tend to have a close association with debates about welfare, ethics and the controversy about fish pain, e.g., [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Fish welfare has also risen slowly up the agenda of animal welfare charities and campaign groups. Following the steep rise of finfish aquaculture in the global North, the websites of most of the large, multi-campaign issue organizations now feature dedicated pages to fish farming and humane slaughter. There are also a growing number of online campaign groups dedicated specifically to raising awareness about suffering in fisheries and advocating for fish sentience—Fish Feel, Let Fish Live, and fishcount.org are prominent examples see [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Via the European Union in particular, regulators have made attempts at entrenching the legal recognition of fish as sentient beings in practice, and have been active in areas including humane slaughter regulations and the harmonizing of husbandry standards for farmed fish, e.g., [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. These and other developments (notably welfare-motivated restrictions on recreational angling in Switzerland and Germany) have recently led some fisheries biologists to wonder what the developing welfare agenda means for the future of aquaculture, angling, commercial fishing and research? [ 43 ].

However, the (re)emergence of discussions around contested moralities of recreational angling [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ], welfare in the context of wild-capture fisheries [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ], the ethics of dietary trends (pescetarianism) [ 54 , 55 ], and the putative demands amongst consumers in some countries for higher welfare farmed fish [ 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 ], all suggest that there remain stubborn, sometimes intractable, challenges in all of these areas. Growth in the number of commentators does not necessarily reflect serious changes in policy and practice. It is also not yet clear whether recent interest by the news media in scientific work exploring the mental and emotional capacities of some fish species—including for example their capacity to feel pain [ 62 ], pass the mirror test of putative self-awareness [ 63 ], or “pine” for their mates and get depressed [ 64 , 65 ]—either reflect or have provoked substantial changes in public attitude. What people make of such information is open to debate. The film Finding Nemo, with its positive and engaging portrayal of one the ocean’s most charismatic fish species and its famous line “fish are friends—not food”, was predicted to have caused a ripple effect in public sentiment towards fish and the aquatic world. However, ironically, when the geographer Driessen [ 66 ] investigated this, he discovered that the film had, in fact, become a popular name for cafés specializing in fish and chips. With one café already adopting it as a name, the same appears set to be true of Blue Planet II, David Attenborough’s hugely popular documentary, which has been credited with kick-starting debate about the state of the planet’s oceans, and showed the world footage of sophisticated and surprising fish behaviors, including tool use [ 67 , 68 ].

This wider social and cultural context is important when approaching the welfare situation of laboratory fish and the 3Rs. The intensification of fish use in laboratory research generally—and the rise to prominence of zebrafish models in particular—have likewise provoked higher levels of interest in the issue of fish welfare in the sector in the UK and internationally. This includes an emergence of reflections on different ethical issues associated with the use of fish in research specifically [ 21 , 69 , 70 ]. There has also been a growing willingness to consider, develop and implement 3Rs initiatives focused on fish amongst animal technologists, scientists, veterinarians and policy makers, and both the UK and pan-European laboratory animal welfare and veterinary organizations have all played different roles in highlighting fish welfare amongst their constituencies, e.g., [ 71 , 72 , 73 ]. Furthermore, there are direct links between developments in laboratory fish welfare and other sectors. In the UK, intensive aquaculture and the laboratory aquarium are connected via personnel, technology and knowledge transfer. For example, via links between forums such as the Fish Veterinary Society and the Laboratory Animal Veterinary Society (both subsections of the British Veterinary Society), or notable colloquiums organized by organizations like the National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement and Reduction of Animals in Research (NC3Rs) and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS).

Yet, again, there remains a widespread sense amongst those who work with fish or who regulate fish-based science that the degree of attention that fish of any species receive is not yet commensurate with the quantities in which they are used, their importance to science, nor—if much recent behavioral and neuroscientific evidence is accepted—their possible levels of suffering. As the authors’ have often heard in the course of their research, this sense is quite widely shared amongst scientists, technologists and others who work with fish (including zebrafish) in the UK. This can filter through and be reflected in efforts to prioritize 3Rs and other welfare-relevant interventions that benefit fish. By discussing challenges to the 3Rs with reference to wider context, this paper sets out to stimulate discussion and reflection by proposing that developments (or lack thereof) in this field are connected to a variety of interlinked social drivers, and scientific, institutional and regulatory viewpoints.

2. Materials and Methods

Within the social sciences, qualitative methods offer an effective and insightful means of understanding the intersection of the broader (largely utilitarian) ethical frameworks which shape animal research, and the more individualized moral convictions, beliefs and practices of those who work closely with laboratory animals and who are often tasked with implementing policy. Interviews and participant observation, alongside the analysis of key literatures, policy documents and archival materials, have formed the basis of several landmark studies in the field, e.g., [ 9 , 74 ], and have proved highly effective in developing understandings of how ethics and the 3Rs are “put into practice” in the field of animal research [ 75 ]. Adopting a similar approach, this paper seeks to energise debate on fish and the 3Rs by drawing on the authors’ experiences of participant observation in UK zebrafish facilities, participation in professional events and conferences, as well as interviews with stakeholders. It is not intended to be a technical review of 3Rs initiatives and related welfare issues for zebrafish (of these there are a growing number, see e.g., [ 21 , 69 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 ]). The objective here is to gain insights into how people who work with laboratory fish understand and explain their practices and their relationships to the humans and animals they work with, and also to the wider field of animal research. In other words, we are offering an account of the ways in which people talk about: (i) whether or not they (and others) care about fish (attitudes towards); and (ii) how this shapes their ability to care for them (husbandry practices). By relating these to wider literatures, policy documents and other textual sources we can begin to build up a picture of the key social norms and discourses in and around laboratory zebrafish research, the possible implications of these for fish welfare, and hopefully shed light on barriers to implementing and developing the 3Rs initiatives for from a sociological, rather than technical, point of view.

The arguments presented in this paper are derived from a larger body of ongoing research into the species and spaces of contemporary animal research in the UK, performed as a part of the collaborative research project “The Animal Research Nexus” project (see www.animalresearchnexus.org ). This project seeks to understand the factors that have shaped and continue to underpin the social contract on which animal research in the UK rest, better understand emergent issues and challenges, and contribute positively to cultures of communication across the sector. This paper draws on data and insights developed in one sub-strand of this wider project. This strand of work focused on understanding the care and welfare work of animal technologists, the managers of aquarium facilities and scientists who work with fish, asking how their understandings of their work relate to wider ethical and legal frameworks. As a part of this, we also engaged with other stakeholders, including veterinary professionals and the regulators of animal research in the UK—in particular, Home Office Inspectors—as well as animal welfare organisations.

This study adopts a mixed method approach, drawing on a combination of in-depth interviews, participant observation and documentary analyses. Firstly, in order to gain an insight into how fish welfare is put into practice, the first author has taken part in two one-week-long stints as a participant-observer in two different zebrafish aquariums in the UK, conducted repeat visits to a facility to see how they introduced a new zebrafish room, and participated in a professional training course for researchers and technicians who work with zebrafish. Secondly, we have reviewed publicly available documentation and relevant professional literature. Thirdly, we conducted in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews with 27 individuals (two interviews involved more than one participant being interviewed at a time), including scientists, animal technologists, facility managers, veterinary professionals, representatives of animal welfare charities, and regulators. Additionally, both authors have paid shorter visits to numerous fish facilities across the UK over the past seven years, as well as attended and participating in a variety of professional conferences and related forums and engaging in ongoing collaboration and dialogue with the wider animal research community and associated stakeholders, including both those supportive of and against animal research. While we have interviewed three scientists based at contract research organizations and pharmaceutical companies, and those who specialise in commercial regulatory testing, our focus has been on university-based bioscience research. This is because this is where the vast majority of fish research in the UK is conducted. This is additionally justified because there is already a disproportionate focus on toxicology research in the 3Rs literature [ 82 , 83 ]. Lasting, on average, around one and a half hours, interviews were conducted, where possible, at the place of work of the interviewee. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and analyzed thematically using the qualitative data analyses tool NVivo. A number of key themes were identified ( Table 1 ). A close reading of the relevant sections of text associated with each of these codes was then used to establish which of these themes are most pertinent to understanding the social and cultural barriers to implementing the 3Rs for zebrafish welfare, the topic of this paper—other themes identified, of course, relate more to emergent elements of the wider program. This was justified with primary reference to what participants themselves said about the 3Rs, our own experience of interacting with stakeholders and working in zebrafish facilities (participant observation), reference to themes in associated literature (discourse analysis), as well as in the light of secondary social science literature on the social organisation of animal science and the 3Rs.

Summary of main themes emerging from qualitative interviews.

| 1 | Human-animal relations\Relating to fish |

| 2 | Animal research identities and group relations\Animal technologist-scientist relations |

| 3 | Protected life stages\The 5 days’ post-fertilization rule |

| 4 | Organisational and regulatory processes\Regulatory issues\3Rs |

| 5 | Welfare debates\Enrichment |

| 6 | Social relations, people and politics\Participants backgrounds |

| 7 | Organizational and regulatory processes\Regulatory issues\Home Office Inspectors |

| 8 | Model organisms\Model selection and uses |

| 9 | Model organisms\”Good Science” and reproducibility |

| 10 | Participants backgrounds\Early life experiences |

| 11 | Human-animal relations\Reading animal bodies |

| 12 | Rodent/fish comparisons\Comparing attitudes towards fish vs. rodents |

| 13 | Rodent/fish comparisons\Rodents as “models” for fish welfare |

| 14 | Aquarium practices\welfare checking, screening and quarantine procedures |

| 15 | Human-animal relations\Animal technologist-animal relations |

| 16 | Organisational and regulatory processes\Management issues\Training |

| 17 | Developing welfare systems\Standardisation practices |

| 18 | Protected life stages\Larval sentience |

| 19 | Aquarium practices\Feeding |

| 20 | Management issues\Economics |

| 21 | Regulatory issues\Opinions about ASPA (UK legislation) |

| 22 | Animal capacities\Fish pain |

| 23 | Management issues\Staffing |

| 24 | Purpose of research\Regulatory testing |

| 25 | Aquarium practices\Culling\Experience of culling |

These themes represent the top 25 codes generated by the authors in the process of data analyses. They are reported in descending order, from most used to least frequently used. Codes and the themes they represent often overlap. The number of times a code is used can suggest the importance of the subject to both the speaker and analyst, but the frequency of use is not on its own a measure of importance or relevance to the present topic.

While a number of foci suggest themselves, some of which the authors’ explore in forthcoming work, we have thus restricted the discussion below to three key themes: “knowledge and consensus”, “attitudes and experiences”, and “institutional support and capacity”.

In keeping with the intentions of qualitative research of this kind, emphasis is placed on depth as opposed to breadth. The sample size is small, and the results selected for presented here are indicative of a wide range of themes and key issues that should be taken into account rather than thought of as being representative in any way. A logical next step may be to use some of the perceived issues and concerns raised here as a basis for a larger, quantitative study. Inevitably, we have also neglected to discuss a number of important social and scientific issues relevant to understanding the challenges to taking up 3Rs initiatives focused on zebrafish, or fish in general. These include, for example, generic concerns about the lower status of animal welfare science and 3Rs related research versus the attractions of other fields of biological research and the relative ghettoisation of 3Rs research as a distinct category [ 84 ] (p.128). It is also possible that if and when concerns about the reproducibility of much zebrafish-based science grows, so too will “neophobia” increase in prominence as a barrier to 3Rs interventions with zebrafish though is not something reflected in our data [ 85 ].

Due to the sensitive nature of the topic (animal research), a policy of anonymisation and decontextualisation has been applied to all transcripts in order to ensure the privacy of participants. All names used in this paper are pseudonyms. All interviews were conducted with the written consent of participants. This research has been granted ethical approval by the Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC) of the University of Oxford (Reference Number: SOGE 18A-7). By agreement with the Wellcome Trust and research participants, anonymised interview transcripts will be deposited in the UK Data Archive based at the University of Essex ( https://www.data-archive.ac.uk ) after a period of 10 years from the completion of the Animal Research Nexus Project in 2022, except in cases where participants have explicitly opted out of this arrangement.

Focusing on Zebrafish

This paper focuses on zebrafish because, over the last three decades, they have become by far the most prominent species of fish used in animal research. In 2018, zebrafish accounted for 12 percent of all procedures done on live animals (including creation and breeding of GA lines) in the UK. All other species of fish combined accounted for 2.6 percent of animals used [ 86 ]. The species’ relatively steep rise towards the apex of lab “supermodels” has often meant that those seeking to develop 3Rs and other welfare-relevant scientific and husbandry protocols have had to work hard to keep up with the pace of change whilst striving to improve [ 80 , 87 ]. At the same time, the rise of the zebrafish, in conjunction with other trends such the intensification of aquaculture production and related public anxieties about environmental externalities and food safety, have most likely served to cast light onto the issue of fish welfare more generally, e.g., [ 42 , 88 , 89 ]. To this extent, and remaining mindful of the extensive diversity of fish kinds, many of the points made in this paper will nevertheless also be relevant to other fish species.

A number of factors are regularly cited as key attractions of the zebrafish model for biologists. These include its hardiness in captivity, small size, short generation time, rapid development and large clutch size. These factors also make them relatively cheap to maintain in large numbers. In addition, the comparative simplicity of the zebrafish genome facilitated the application of various molecular technologies. In combination with the extraordinary optical accessibility of its embryos and young larvae (they are transparent and fertilized externally to the mother’s body), these features have made zebrafish a highly tractable model for other vertebrate animals, and useful in a wide range of fields. However, these very advantages of the organism for science can also contribute to the entrenchment of particular attitudes towards them, and towards fish generally. Moreover, they can raise 3Rs considerations in their own right. Ironically, their hardiness in captivity has proven a disincentive for refining their husbandry conditions [ 90 ] (p.141). Depending on local aquarium practices and pricing structures, the low costs of maintaining zebrafish in large numbers and the ease with which they can usually be bred can create an incentive to keep transgenic lines running even when they are not being used, and a disincentive to cryopreserve and regenerate on demand—strategies which would be seen as more consistent with a reduction in animal use. The fact that zebrafish models can be valuable surrogates for other vertebrates also tends to compound the view of them as “lower” on the so-called phylogenetic scale, contributing in turn to the view that the use of fish (as embryos or larvae, but also adults) represents a kind of “relative replacement” for other vertebrate animals [ 91 ] (p.274), which is to say, a means for achieving 3Rs (replacement or refinement) targets, as opposed to individuals to whom the 3Rs principles of refinement, reduction and replacement could be applied (see also [ 92 ]).

The scale at which zebrafish are maintained and the ease and rate at which they can be induced to reproduce can also all contribute to a sense of their replaceability, and underline the difficulty of forming a bond with them as individuals—even in comparison to other small, short-lived and relatively easily replaced laboratory vertebrates like mice [ 93 , 94 ]. Some people, especially animal technologists, attempt to think of fish as unique individual beings that deserve attention as such. At one facility, we know there is an informal motto that runs along the lines of: “they’re all a group of fish, but every fish is an individual” (interview with Eugenie, aquarium facility manager, 8 February 2018). However, at the same time, it is acknowledged that this requires effort to sustain, and successful and lasting individualisation is the exception, not the rule (see also [ 95 ]). For all these and other reasons—some of which will be explored in more detail below—it is common to hear the argument that the apparent lack of social or ethical concerns associated with the use of fish in experiments is in itself one of the advantages of using zebrafish-based model systems, e.g., [ 20 ] (p. 407–408). Fish in general, but zebrafish specifically, are indeed frequently viewed as the “easier ethical option”, as one participant in our study put it (interview with Helen, representative of an animal welfare organization, 9 January 2019). In sum, while similar things may be said about other fish species, there are good reasons to pay special attention to zebrafish.

3. Results and Discussion

Analyses of our interview data suggest the presence of three especially significant social norms or discourses about fish welfare in the laboratory context. For summary purposes, we have labelled these “knowledge and consensus”, “attitudes and experiences”, and “institutional support and capacity”. Each of these narratives is internally diverse in terms of the individual opinions expressed, as well as overlapping and mutually reinforcing. Key themes included in the discussions which follow include: (structural) enrichment, fish, regulatory attitudes with respect to fish and the public; views about fish, embryos and larvae from within the aquarium and the size and composition of the zebrafish community

3.1. Knowledge and Consensus

Appendix A of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS123) provides key guidelines for the accommodation and care of animals used in science across Europe. Speaking about the challenge of managing a number of expert working groups convened by Council of Europe during the process of revising Appendix A in the early 2000s, an ex-UK Home Office Inspector told us “ [It] was like herding cats—they would not agree on anything ” (interview with Colin, ex-Home Office Inspector, 26 June 2019). In his experience, the field of fish welfare has been characterised by a lot of disagreement, often underpinned by insufficient knowledge of fish/zebrafish welfare science and of the basic biology that informs it, at least in comparison to the knowledge of the other major laboratory animal species. Similarly, our research suggests that, amongst those involved in the worlds of zebrafish science, there is limited consensus on what best practice is in a number of important welfare and 3Rs-relevant areas. Debate rages on numerous topics, including stocking density, food and feeding regimes, methods of anesthesia, euthanasia, the need for analgesia, and the need for environmental enrichment, to name only a few. This is reflected, as Colin explained, in the relative paucity of official guidance available for fish at the EU level or the level of individual member states—even for zebrafish, which are the most studied and used species. This section therefore explores narratives about knowledge, consensus and disagreement, focusing on two different examples. Firstly, the question of environmental enrichment, and secondly variation in beliefs about the ability of fish to feel pain and suffer, both of which are clearly relevant to welfare generally and the 3Rs specifically.

3.1.1. “Putting Things in Tanks”

There exists a division in the zebrafish community in the UK between those who are in favor of environmental enrichment, and those who raise concerns about it (see also [ 96 ] p.586). To be specific, some facility managers and technologists—experienced husbandry professionals, some with backgrounds in relevant scientific disciplines—express doubts about the benefits of structural enrichment: the addition of plastic plants, substrates and so forth so as to provide cover and stimulation for fish who otherwise live in barren, clear plastic tanks. Some suggested that structural enrichment can encourage abnormal behavior, but the most common issue raised was that the welfare benefits of structural enrichment were not very clear. Felix, an experienced facility manager with a background in research, suggested there was a fashion for “putting things in tanks” (interview with Felix, aquarium facility manager, 1 November 2018). Felix, and others whom we have spoken to who share his point of view, are far from dismissive of enrichment for fish in general but worry that a focus on structural enrichments is a distraction from the factors they think are really more important for fish welfare and should be the focus of attention. Felix terms these more important factors the “subtle enrichments, your lighting, your temperatures, your feeding, your flows, those are a much more valuable asset than a plastic plant within a tank”.

People like Felix worry that the evidence base about the value of such structural enrichments for zebrafish is weak. An ex-Home Office inspector comments:

I think probably the biggest constraint is just actually the lack of good data and scientific knowledge about what an appropriate environment for the zebrafish might be. I think again there is quite a lot of anthropomorphic views on what a zebrafish actually requires. You put them into an empty tank and that must be bad for them so they then put in lots of substrate and weeds and various other things in as well, you know, but we don’t really know, I don’t know… [interview with Craig, ex-Home Office Inspector, 25 June 2019]

Another facility manager concurs, arguing the welfare benefits of this kind of enrichment are in her estimation “fairly unproven”:

[W]e can’t make that much more progress I personally don’t feel unless we can really say this is what is good for them in terms of like environmental enrichment, do we want divers in there with bubbles, and why would we want that, where do they ever see that, or plastic plants, would they see that in the wild? Is it appropriate? [interview with Fae, aquarium facility manager, 27 February 2018]

No one, of course, is suggesting the use of plastic divers and shipwrecks in academic research aquariums. The point being made is that the desire for objects in tanks is largely a human one: it satisfies our humane and aesthetic demands, rather than (so the suggestion goes) the real needs of the animals (as far as we know). Hence it has been pursued in the absence of evidence about its benefits. Fae and others in her position do not disagree that it is possible to observe certain behavioral changes on the introduction of an object like a plastic plant or simulated substrate, for example, which suggest a preference for occupying enriched parts of the tank. It is the interpretation of what these observed behavioral changes might actually mean for fish welfare that is questioned.

These kinds of concerns were echoed by animal technologists who work closely with fish. For example, Frank noted:

We can look at cortisone levels or whatever but you don’t really know if you’re actually helping them. Like with a plant, I mean on one hand you’re creating cover for them to hide in if they’re getting bullied or fighting, on the other hand, you’re creating something for someone to get territorial about and stressed about. [interview with Frank, senior animal technologist, 18 January 2018]

A Home Office inspector also noted that

[I]n terms of enrichment, for instance, we don’t actually know largely what fish want. […] And I think that--, that’s a significant challenge to get over some of the hurdles and show people how it can happen. [interview with Gail, Home Office Inspector, 15 May 2019]

While Gail sees this lack of knowledge as a barrier to acceptance, this does not feature in her discourse as a reason for being cautious about advocating their uptake in aquariums. Evidently, people operate with different ideas about what a sufficient evidential bar is. This reflects divisions in the field of laboratory animal welfare more generally as to whether the intuitions and experiences of the practices and protocols developed by technologists in individual facilities offer a strong enough evidence base for novel enrichment practices [ 75 ]. In this context, it is, of course, possible to cleave too bio-physiological measures of “health” only, in which the psychological and emotional factors usually comprehended within the wider term “welfare” are excluded. [ 44 ]. However, the latter, more encompassing and holistic outlook certainly seems to motivate managers and technologists who go out of their way to provide structural enrichments when they can. Sometimes this can be a real labor of love. One establishment found it could not afford to buy plastic plants from a hobby shop, so developed a way of making “plants” by fashioning them from plastic bags and weighing these down with marbles. This took six months of soaking the bags in a light bleach solution to stop the plastic leaching substances that may interfere with scientific results, and careful and time-consuming handwork by staff members to shape the fronds and attach the weights [RM, Field Notes,11 January 2018].

Advocates of structural enrichment do cite published evidence in favor of their opinions. A paper suggesting that zebrafish express a preference for substrates by positioning themselves over photographs of gravel is particularly often cited in the UK (see [ 97 ]). Those already inclined to enrichment tend to find such evidence a better reason to act than others who are not. An animal welfare policy expert felt that these results clearly “show that they [zebrafish] benefit from environmental enrichment”, but implied that this evidence was ignored (interview with Helen, representative of animal welfare organization, 9 January 2019). Others object to this interpretation of the meaning of fish preference behaviors or report having been told of (the referecne to hearsay is deliberate here) statistical or methodological weaknesses in papers about enrichment, and explain that people they know—others in the field—have taken these as a basis for inaction.