An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Poverty and Health Disparities: What Can Public Health Professionals Do?

Affiliations.

- 1 1 University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA.

- 2 2 Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA.

- 3 3 University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

- PMID: 29363333

- DOI: 10.1177/1524839918755143

More than a tenth of the U.S. population (13% = 41 million people) is currently living in poverty. In this population, the socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions have detrimental health effects such as higher rates of chronic diseases, communicable illnesses, health risk behaviors, and premature mortality. People living in poverty are also deprived of social, psychological, and political power, leading to continuation of worsening health and chronic deprivation over generations. The health of individuals living in poverty poses greater challenges from policy, practice, and research standpoints. Public health professionals are poised uniquely to be advocates for the marginalized, be the resource persons for health education, implement health promotion programs, and conduct research to understand health effects of poverty and design tailored and targeted public health interventions. In this article, we summarize the opportunities for public health practice with individuals living in poverty.

Keywords: health disparities; poverty; public health policies; social determinants of health; social policy.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Structural approaches to health promotion: what do we need to know about policy and environmental change? Lieberman L, Golden SD, Earp JA. Lieberman L, et al. Health Educ Behav. 2013 Oct;40(5):520-5. doi: 10.1177/1090198113503342. Health Educ Behav. 2013. PMID: 24048612

- Shaping public policy and population health in the United States: why is the public health community missing in action? Raphael D. Raphael D. Int J Health Serv. 2008;38(1):63-94. doi: 10.2190/HS.38.1.d. Int J Health Serv. 2008. PMID: 18341123

- Reducing Premature Mortality in the Mentally Ill Through Health Promotion Programs. Price JH, Khubchandani J, Price JA, Whaley C, Bowman S. Price JH, et al. Health Promot Pract. 2016 Sep;17(5):617-22. doi: 10.1177/1524839916656146. Epub 2016 Jun 14. Health Promot Pract. 2016. PMID: 27307394

- A Critical Exploration of Migraine as a Health Disparity: the Imperative of an Equity-Oriented, Intersectional Approach. Befus DR, Irby MB, Coeytaux RR, Penzien DB. Befus DR, et al. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018 Oct 5;22(12):79. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0731-3. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018. PMID: 30291549 Review.

- Disparities in health, poverty, incarceration, and social justice among racial groups in the United States: a critical review of evidence of close links with neoliberalism. Nkansah-Amankra S, Agbanu SK, Miller RJ. Nkansah-Amankra S, et al. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(2):217-40. doi: 10.2190/HS.43.2.c. Int J Health Serv. 2013. PMID: 23821903 Review.

- Miracle friends and miracle money in California: a mixed-methods experiment of social support and guaranteed income for people experiencing homelessness. Henwood BF, Kim BE, Stein A, Corletto G, Suthar H, Adler KF, Mazzocchi M, Ip J, Padgett DK. Henwood BF, et al. Trials. 2024 Apr 29;25(1):290. doi: 10.1186/s13063-024-08109-6. Trials. 2024. PMID: 38685123 Free PMC article.

- Self-reported Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Economic Inflation on the Well-being of Low-income U.S. Veterans. Tsai J, Hird R, Collier A. Tsai J, et al. J Community Health. 2023 Dec;48(6):970-974. doi: 10.1007/s10900-023-01267-9. Epub 2023 Aug 21. J Community Health. 2023. PMID: 37605100

- Diversity in maintaining health of populations. Nsibandze BS. Nsibandze BS. Health SA. 2022 Dec 13;27:2137. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v27i0.2137. eCollection 2022. Health SA. 2022. PMID: 36570092 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Chasing the Youth Dividend in Nigeria, Malawi and South Africa: What Is the Role of Poverty in Determining the Health and Health Seeking Behaviour of Young Women? Mkwananzi S, Baruwa OJ. Mkwananzi S, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Oct 30;19(21):14189. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114189. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 36361068 Free PMC article.

- Perceptions of Barriers: An Examination of Public Health Practice in Kansas. Eppler M, Brock K, Brunkow C, Mulcahy ER. Eppler M, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 1;19(9):5513. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095513. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35564905 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 59, Issue 4

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Center for Research on Population and Health, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

- Correspondence to: Dr M Khawaja Center for Research on Population and Health, American University of Beirut, Beirut 1107 2020, Lebanon; mk36aub.edu.lb

This glossary addresses the complex nature of poverty and raises some conceptual and measurement issues related to poverty in the public health literature, with a focus on poor countries.

- community health

- social exclusion

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.022822

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Linked Articles

- In this issue Is epidemiology popular enough? Carlos Alvarez-Dardet John R Ashton Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2005; 59 253-253 Published Online First: 14 Mar 2005.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality

- 1 Chief population health officer of New York City Health + Hospitals, and clinical associate professor of population health and medicine at the New York University School of Medicine

The health of people with low incomes historically has been a driver of public health advances in the United States. For example, in New York City, cholera deaths during outbreaks in 1832 and 1854 concentrated among the poor helped push forward the Metropolitan Health Law, which allowed for regulation of sanitary conditions in the city. The law was an exemplar for other municipalities across the United States, saving countless lives during subsequent cholera epidemics as well as from typhus, dysentery, and smallpox.

Health inequality persists today, though our public health response—our modern Metropolitan Health Laws—must address more insidious causes and conditions of illness. There is a robust literature linking income inequality to health disparities —and thus widening income inequality is cause for concern. US Census data show a steady increase in summary measures of income inequality over the past 50 years. The association between income and life expectancy, already well established, was detailed in a landmark 2016 JAMA study by Raj Chetty, PhD, of Stanford University, and colleagues. This study found a gap in life expectancy of about 15 years for men and 10 years for women when comparing the most affluent 1% of individuals with the poorest 1%. To put this into perspective, the 10-year life expectancy difference for women is equal to the decrement in longevity from a lifetime of smoking.

Probing the Income-Health Relationship

In an editorial that accompanied the article by Chetty et al, Angus Deaton, PhD, of Princeton University, commented on the study’s geographical findings: “It is as if the top income percentiles belong to one world of elite, wealthy US adults, whereas the bottom income percentiles each belong to separate worlds of poverty, each unhappy and unhealthy in its own way.” Prior research had tried to identify these separate worlds, describing “ Eight Americas ” defined by sociodemographic characteristics, such as low-income white people in Appalachia and the Mississippi Valley, Western Native Americans, and Southern low-income rural black people. To improve health, interventions may need to account for starkly different lived experiences across different geographic contexts.

Educational attainment, sex, and race interact with and complicate the income-health relationship. Two additional dimensions add complexity: thinking beyond income to wealth and thinking beyond mortality to morbidity. Wealth refers to the total value of assets (and debts) possessed by an individual, not just the flow of money defined as income. Wealth is even more unequally divided than income : while the top 10% of the income distribution received a little more than half of all income, the top 10% of the wealth distribution held more than three-quarters of all wealth. This matters because it is one way that inequities persist over time —through, for instance, legacy effects of Jim Crow laws or discriminatory housing policy that affect family wealth and health over generations .

Studies on inequality and mortality may garner the most attention, but disparities in morbidity and quality of life are also evident. Low-income adults are more than 3 times as likely to have limitations with routine activities (like eating, bathing, and dressing) due to chronic illness, compared with more affluent individuals. Children living in poverty are more likely to have risk factors such as obesity and elevated blood lead levels, affecting their future health prospects.

Inequality or Inequity?

Is it the role of physicians and other health professionals to address poverty? Is it a “modifiable” risk factor, or should we focus on more proximate causes of illness, such as health behaviors? Our answers to these questions determine whether wealth gradients lead only to health inequality—or whether they contribute to health inequity , which is inequality that is avoidable and unfair.

Two arguments favor paying attention to income and wealth distributions as part of advancing health equity. First, health care spending—the realm of medical professionals—can worsen income inequality, at both individual and systemic levels. Individually, poor people have to spend a much greater proportion of their income on health care than richer people do. In 2014, medical outlays lowered the median income for the poorest decile of US individuals by 47.6% vs 2.7% for the wealthiest decile. Systemically, medical spending can crowd out other government spending on social services , drawing resources away from education and environmental improvement, for example. Taken together, this supports the case that “first do no harm” must extend to the financial impact of delivering health care. Clinicians who care about the social determinants of health must also pay heed to the cost (and opportunity cost) of health care.

Second, we are in a period when declines in key public health indicators may be wrought by policies that ostensibly have little to do with health—such as tax policy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that average life expectancy decreased for the second year in a row in 2016. But mean mortality changes may obscure the full picture , which is more about increasing mortality being concentrated in lower-income groups. Meanwhile, the recent Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is likely to exacerbate income inequality. This is particularly true if the tax cuts trigger cuts in government spending , as Republican leaders have signaled. Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as food stamps) are 2 programs for low-income individuals that are likely to be targeted for cuts. Even if Medicare and Social Security are spared, life expectancy differences by income means that more affluent US adults can expect to claim those benefits over a longer lifespan.

What would be today’s analog to the Metropolitan Health Law of 1866? Addressing the root causes of health inequity requires interrupting the vicious cycle of poverty leading to illness leading to poverty—what Jacob Bor, ScD, and Sandro Galea, MD, of Boston University School of Health, have termed a “21st century health-poverty trap.” Although there are many root causes to address, perhaps the place to begin is the health of children. For instance, economic policy like the Earned Income Tax Credit has been associated with decreases in low birth weight.

Congress’ recent reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program offers a glimmer of hope for such bipartisan paths toward health equity nationally. Focusing on resources to support children—such as nurse home visits to pregnant women, prekindergarten programs, and adolescent mental health care— can directly improve health while influencing intergenerational economic mobility. The city of Philadelphia offers a concrete example of how to do this: a tax on sugary drinks was used to fund prekindergarten, social services in neighborhood schools, and parks and libraries. In this way, health might lead to economic opportunity, leading to better health.

Corresponding Author: Dave A. Chokshi, MD, MSc ( [email protected] ).

Published Online: February 21, 2018, at https://newsatjama.jama.com/category/the-jama-forum/ .

Disclaimer: Each entry in The JAMA Forum expresses the opinions of the author but does not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of JAMA, the editorial staff, or the American Medical Association.

Additional Information: Information about The JAMA Forum, including disclosures of potential conflicts of interest, is available at https://newsatjama.jama.com/about/ .

Note: Source references are available through embedded hyperlinks in the article text online.

See More About

Chokshi DA. Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1312–1313. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.2521

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Advertisement

Climate change, poverty and child health inequality: evidence from Vietnam’s provincial analysis

- Published: 09 September 2024

- Volume 57 , article number 163 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Cong Minh Huynh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8169-5665 1 &

- Bao Khuyen Tran 1

This paper investigates how climate change and poverty affect child health inequality across 63 provinces in Vietnam from 2006 to 2023. By examining deaths and economic losses from storms and floods, we assess climate change’s impact; while, infant mortality rate (IMR) and under-5 mortality rate (U5MR) serve as indicators of child health inequality. Findings reveal that climate change directly worsens child health inequality and exacerbates it indirectly by increasing poverty. Notably, the effects on U5MR are more pronounced than on IMR. Additionally, child vaccinations, healthcare infrastructure, and access to clean water are vital in reducing health disparities and mitigating climate change’s harmful effects on child health.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

See more at: http://ccdpc.gov.vn/default.aspx

See more at: https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/homepage/

See more at: https://papi.org.vn/eng/

Ahmed A, Asabere SB, Adams EA, Abubakari Z (2023) Patterns and determinants of multidimensional poverty in secondary cities: implications for urban sustainability in African cities. Habitat Int 134:102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102775

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed SA, Diffenbaugh NS, Hertel TW, Lobell DB, Ramankutty N, Rios AR, Rowhani P (2011) Climate volatility and poverty vulnerability in Tanzania. Glob Environ Chang 21(1):46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.10.003

Alaba OA, Hongoro C, Thulare A, Lukwa AT (2021) Leaving No Child Behind: Decomposing Socioeconomic Inequalities in Child Health for India and South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(13):7114. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137114

Anser MK, Yousaf SU, Usman B, Azam K, Bandar NFA, Jambari H, Sriyanto S, Zaman K (2023) Beyond climate change: Examining the role of environmental justice, agricultural mechanization, and social expenditures in alleviating rural poverty. Sustain Futures 6:100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2023.100130

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Azzarri C, Signorelli S (2020) Climate and poverty in Africa South of the Sahara. World Dev 125:104691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104691

Bango M, Ghosh S (2023) Reducing infant and child mortality: assessing the social inclusiveness of child health care policies and programmes in three states of India. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15812-7

Benevolenza MA, DeRigne L (2019) The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: a systematic review of literature. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 29(2):266–281

Bennett CM, Friel S (2014) Impacts of climate change on inequities in child health. Children 1(3):461–473

Billah MA, Khan MMA, Hanifi SMA, Islam MM, Khan MN (2023) Spatial pattern and influential factors for early marriage: evidence from Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey 2017–18 data. BMC Women’s Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02469-y

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet 371(9608):243–260

Blank RM (2000) Distinguished lecture on economics in government—fighting poverty: lessons from recent US history. J Econ Perspect 14(2):3–20

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econ 87(1):115–143

Bunyavanich S, Landrigan CP, McMichael AJ, Epstein PR (2003) The impact of climate change on child health. Ambul Pediatr 3(1):44–52

Bureau USC (2009) Statistical abstract of the United States. US Government Printing Office, Washington

Google Scholar

Callander EJ, Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN (2012) Multiple disadvantages among older citizens: what a multidimensional measure of poverty can show. J Aging Soc Policy 24(4):368–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2012.735177

Cermeño AL, Palma N, Pistola R (2023) Stunting and wasting in a growing economy: biological living standards in Portugal during the twentieth century. Econ Human Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2023.101267

Chersich MF, Pham MD, Areal A, Haghighi MM, Manyuchi A, Swift CP, Wernecke B, Robinson M, Hetem R, Boeckmann M et al (2020) Associations between high temperatures in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirths: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3811

Clemens V, von Hirschhausen E, Fegert JM (2020) Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:701–713

Ebaidalla EM (2023) Inequality of opportunity in child health in Sudan: across-region study. J Econ Dev 48(1):59–83

Ebi KL, Vanos J, Baldwin JW, Bell JE, Hondula DM, Errett NA, Hayes K, Reid CE, Saha S, Spector J et al (2021) Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annu Rev Public Health 42(1):293–315

Fagbamigbe AF, Lawal TV, Atoloye KA (2023) Evaluating the performance of different Bayesian count models in modelling childhood vaccine uptake among children aged 12–23 months in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16155-z

Filho WL, Taddese H, Balehegn M, Nzengya D, Debela N, Abayineh A, Mworozi E, Osei S, Ayal DY, Nagy GJ, Yannick N, Kimu S, Balogun A-L, Alemu EA, Li C, Sidsaph H, Wolf F (2020) Introducing experiences from African pastoralist communities to cope with climate change risks, hazards and extremes: Fostering poverty reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 50:101738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101738

Gentle P, Maraseni TN (2012) Climate change, poverty and livelihoods: adaptation practices by rural mountain communities in Nepal. Environ Sci Policy 21:24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.03.007

Goldhagen JL, Shenoda S, Oberg C, Mercer R, Kadir A, Raman S, Waterston T, Spencer NJ (2020) Rights, justice, and equity: a global agenda for child health and wellbeing. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4(1):80–90

Gould W (1993) Quantile regression with bootstrapped standard errors. Stata Tech Bull 2(9):1–28

Göran D, Whitehead M (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Background document to WHO - Strategy paper for Europe, Arbetsrapport 2007:14, Institute for Futures Studies

Hallegatte S, Fay M, Barbier EB (2018) Poverty and climate change: Introduction. Environ Dev Econ 23(3):217–233

Hamilton PB, Hutchinson SJ, Patterson RT, Galloway JM, Nasser NA, Spence C, Palmer MJ, Falck H (2021) Late-Holocene diatom community response to climate driven chemical changes in a small, subarctic lake, Northwest Territories. Canada Holocene 31(7):1124–1137. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596836211003214

Hao Y, Evans GW, Farah MJ (2023) Pessimistic cognitive biases mediate socioeconomic status and children’s mental health problems. Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32482-y

Helldén D, Andersson C, Nilsson M, Ebi KL, Friberg P, Alfvén T (2021) Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet Health 5(3):e164–e175

Hertel TW, Rosch SD (2010) Climate change, agriculture, and poverty. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 32(3):355–385

Hoang HH, Huynh CM (2020) Climate change, economic growth and growth determinants: Insights from Vietnam’s coastal south central region. J Asian Afr Stud 56(3):693–704

Hoechle D (2007) Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. Stata Journal 7(3):281–312

Hope KR (2009) Climate change and poverty in Africa. Int J Sust Dev World 16(6):451–461

Huynh CM (2023) Climate change and agricultural productivity in Asian and Pacific countries: how does research and development matter? J Econ Stud 51:712–729

Khanal U, Wilson C, Rahman S, Lee BL, Hoang V-N (2021) Smallholder farmers’ adaptation to climate change and its potential contribution to UN’s sustainable development goals of zero hunger and no poverty. J Clean Prod 281:124999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124999

Kistin EJ, Fogarty J, Pokrasso RS, McCally M, McCornick PG (2010) Climate change, water resources and child health. Arch Dis Child 95(7):545–549

Kota K, Chomienne M-H, Geneau R, Yaya S (2023) Socio-economic and cultural factors associated with the utilization of maternal healthcare services in Togo: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-023-01644-6

Liu M, Ge Y, Hu S, Stein A, Ren Z (2022) The spatial–temporal variation of poverty determinants. Spatial Statistics 50:100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spasta.2022.100631

Magunda A, Ononge S, Balaba D, Waiswa P, Okello D, Kaula H, Keller B, Felker-Kantor E, Mugerwa Y, Bennett C (2023) Maternal and newborn healthcare utilization in Kampala urban slums: perspectives of women, their spouses, and healthcare providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05643-0

Masson-Delmotte VP, Zhai P, Pirani SL, Connors C, Péan S, Berger N, Caud Y, Chen L, Goldfarb MI, Scheel Monteiro PM (2021). Ipcc, 2021: Summary for policymakers. In: Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. contribution of working group i to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change

Memirie ST, Verguet S, Norheim OF, Levin C, Johansson KA (2016) Inequalities in utilization of maternal and child health services in Ethiopia: the role of primary health care. BMC Health Serv Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1296-7

Mosley LM (2015) Drought impacts on the water quality of freshwater systems; review and integration. Earth Sci Rev 140:203–214

Moyo E, Nhari LG, Moyo P, Murewanhema G, Dzinamarira T (2023) Health effects of climate change in Africa: a call for an improved implementation of prevention measures. Eco-Environ Health 2(2):74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eehl.2023.04.004

Mujica OJ, Sanhueza A, Carvajal-Velez L, Vidaletti LP, Costa JC, Barros AJD, Victora CG (2023) Recent trends in maternal and child health inequalities in Latin America and the Caribbean: analysis of repeated national surveys. Int J Equity Health 22:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01932-4

Muzindutsi P-F (2018) A comparative analysis of income- and asset-based poverty measures of households in a township in South Africa. Int J Econ Financ Stud 10(1):184–202

Ngu NH, Tan NQ, Non DQ, Dinh NC, Nhi PTP (2023) Unveiling urban households’ livelihood vulnerability to climate change: an intersectional analysis of Hue City. Vietnam Environ Sustain Indic 19:100269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2023.100269

Olayide OE, Alabi T (2018) Between rainfall and food poverty: Assessing vulnerability to climate change in an agricultural economy. J Clean Prod 198:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.221

Onyimadu CO (2023) Climate change adaptation and wellbeing among smallholder women farmers in Gwagwalada and Kokona. Nigeria Futures 153:103238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2023.103238

Pham T (2022) The child education and health ethnic inequality consequences of climate shocks in Vietnam. Econ Educ Rev 90:102311

Pollock EA, Gennuso KP, Givens ML, Kindig D (2021) Trends in infants born at low birthweight and disparities by maternal race and education from 2003 to 2018 in the United States. BMC Public Health 21(1):1117

Reeves R, Rodrigue E, Kneebone E (2016) Five evils: multidimensional poverty and race in America. Econ Stud Brook Rep 1:1–22

Ruggeri Laderchi C, Saith R, Stewart F (2003) Does it matter that we do not agree on the definition of poverty? A comparison of four approaches. Oxf Dev Stud 31(3):243–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360081032000111698

Rupasingha A, Goetz SJ (2007) Social and political forces as determinants of poverty: a spatial analysis. J Soc Econ 36(4):650–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2006.12.021

Rylander C, Øyvind Odland J, Manning Sandanger T (2013) Climate change and the potential effects on maternal and pregnancy outcomes: an assessment of the most vulnerable–the mother, fetus, and newborn child. Glob Health Action 6(1):19538

Samanta S, Hazra S, French JR, Nicholls RJ, Mondal PP (2023) Exploratory modelling of the impacts of sea-level rise on the Sundarbans mangrove forest West Bengal India. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166624

Shiferaw N, Regassa N (2023) Levels and trends in key socioeconomic inequalities in childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopia demographic and health surveys 2000–2019. Discov Soc Sci Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44155-023-00034-4

da Silva ICM, França GV, Barros AJD, Amouzou A, Krasevec J, Victora CG (2018) Socioeconomic inequalities persist despite declining stunting prevalence in low-and middle-income countries. J Nutr 148(2):254–258

Teka AM, Temesgen Woldu G, Fre Z (2019) Status and determinants of poverty and income inequality in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities: household-based evidence from Afar Regional State Ethiopia. World Dev Perspect 15:100123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.100123

Trani J-F, Zhu Y, Park S, Khuram D, Azami R, Fazal MR, Babulal GM (2023) Multidimensional poverty is associated with dementia among adults in Afghanistan. Eclin Med 58:101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101906

United Nations (1992). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change . https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf

Wickham S, Anwar E, Barr B, Law C, Taylor-Robinson D (2016) Poverty and child health in the UK: using evidence for action. Arch Dis Child 101(8):759–766

Wooldridge G, Murthy S (2020) Pediatric critical care and the climate emergency: our responsibilities and a call for change. Front Pediatr 8:472

Woronko C, Merry L, Uckun S, Cuerrier A, Li P, Hille J, Van Hulst A (2023) Prevalence and determinants of overweight and obesity among preschool-aged children from migrant and socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts in Montreal Canada. Prev Med Rep 36:102397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102397

Wossen T, Berger T (2015) Climate variability, food security and poverty: agent-based assessment of policy options for farm households in Northern Ghana. Environ Sci Policy 47:95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.11.009

Zhou X, Chen J, Li Z, Wang G, Zhang F (2017) Impact assessment of climate change on poverty reduction: A global perspective. Phys Chem Earth Parts a/b/c 101:214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2017.06.011

Download references

This research is funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number 502.01–2021.48. There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Becamex Business School, Eastern International University, Nam Ky Khoi Nghia St, Hoa Phu Ward, Thu Dau Mot, Binh Duong, Vietnam

Cong Minh Huynh & Bao Khuyen Tran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cong Minh Huynh .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Huynh, C.M., Tran, B.K. Climate change, poverty and child health inequality: evidence from Vietnam’s provincial analysis. Econ Change Restruct 57 , 163 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-024-09743-5

Download citation

Received : 01 February 2024

Accepted : 22 August 2024

Published : 09 September 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-024-09743-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Climate change

- Child health inequality

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Poverty and Health - The Family Medicine Perspective (Position Paper)

Introduction

Poverty is a complex and insidious determinant of health caused by systemic factors that can persist for generations in a family. Beginning before birth and continuing throughout an individual’s life, poverty can significantly impact health and health outcomes. The vision of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) is to transform health care to achieve optimal health for everyone. Primary care physicians and public health professionals continue to collaborate on a shared vision of improving population health. As the integration of primary care and public health continues, this shared vision becomes even more relevant, focused, and clear. Success in this new era means achieving better outcomes by transforming health care to overcome obstacles related to the social, environmental, and community determinants of health – including poverty. 1,2,3,4

Family physicians have a unique perspective on local population’s health challenges because we serve generations of families and follow individual patients through different life stages. We are privileged to share the complex stories of individuals and families in sickness and health over long periods and across different care settings. Rather than viewing a single snapshot of a patient during an episode of illness, we know the patient’s whole story. We know the environmental, patient, and family factors that lead to illness and disease – and the patient’s need to manage their condition effectively. As lifelong collaborators in care, family physicians are well-positioned to understand each patient’s unique obstacles to better health and help overcome them.

Call to Action

The AAFP urges its members to become informed about the impact of poverty on health. Achieving the vision of optimal health for everyone requires a culturally proficient care team and a well-resourced medical neighborhood that supplies readily accessible solutions. Family physicians play a critical role in community health and can contribute through bold efforts in many areas. When these solutions are incorporated seamlessly into everyday practice workflows, family physicians and care teams can be true to the AAFP’s vision by achieving positive change for individuals, families, and communities, and improve population health.

The AAFP calls for action in the following areas:

Physician Level

- Become more informed about the impact of the social determinants of health (SDoH) and identify tangible next steps you can take to address and reduce health inequities

- Be aware of, and sensitive to, your patient’s specific circumstances to help them achieve their health goals

Practice Level

- Identify critical factors that impact patient health, leveraging The EveryONE Project and data collection on SDoH in electronic health records (EHRs)

- Understand each patient’s unique challenges and coping strategies and know what community resources are available

Community-Leadership Level

- Promote alignment with other private and public community resources to help advance the integration of primary care and public health

- Partner with other health care and social service organizations to connect directly to resources that mitigate poverty’s effect on health

Educational Level

- Drive change in undergraduate and graduate medical education to ensure future physicians are adequately prepared to prevent and address disparities caused by SDoH

Advocacy Level

- Work with local, state, and national governments to adopt a Health in All Policies approach that prioritizes health within goals and agenda-setting

- Advocate for regulatory frameworks and economic incentives to ensure public health and population health are critical to individual health care efforts

Understanding Poverty and Low-income Status

Poverty occurs when an individual or family lacks the resources to provide life necessities, such as food, clean water, shelter, and clothing. It also includes a lack of access to such resources as health care, education, and transportation. 5 In the United States, federal poverty is expressed as an annual pre-tax income level indexed by the size of household and age of household members. For example, in 2020, the federal poverty income level was $12,760 for an individual younger than 65 years and $26,200 for a family of four. 6 In 2019, approximately 10.5% of Americans were living below the poverty line. While overall poverty rates had been declining in the past several years, inequalities remain by SDoH, including race and racism, ethnicity, educational attainment, and disability status. 7

The term “low income” generally describes individuals and families whose annual income is less than 130-150% of the federal poverty income level. For example, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is available to individuals with a gross monthly income of 130% of the federal poverty income level. 8 Medicaid is open to families with an income of 138% of the poverty income level. 9

Poverty and low-income status are associated with various adverse health outcomes, including shorter life expectancy, higher infant mortality rates, and higher death rates for the 14 leading causes of death. 10,11 Individual- and community-level mechanisms mediate these effects. 12 For individuals, poverty restricts the resources used to avoid risks and adopt healthy behaviors. 13 Poverty also affects the built environment (i.e., the human-made physical parts of the places where people live, work, and play, including buildings, open spaces, and infrastructure), services, culture, and communities’ reputation, all of which have independent effects on health outcomes. 14

Location matters, and there are often dramatic differences in health care delivery and health outcomes between communities that are only a few miles apart. For example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) found a 25-year difference in average life expectancy in New Orleans, LA, between inner city and suburban neighborhoods. Similarly, there is a 14-year difference in average life expectancy between two Kansas City, MO, neighborhoods that are roughly three miles apart. 15

A study by The Commonwealth Fund assessed 30 indicators of access, prevention, quality, potentially avoidable hospital use, and health outcomes. The study found that populations with low-income status suffer disparities in every state. However, it also identified significant differences among states’ performances. For top-performing states, many health care measures of populations with low income were better than average and better than those for individuals with higher income or more education in lagging states. These findings indicate that low-income status does not have to determine poor health or poor care experience. Interventions seen in top-performing states, such as expanded insurance coverage, access, and coordination of social and medical services, can help mitigate poverty’s effects on health. 16

Poverty and Health

SDoH are the conditions under which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and include factors such as socioeconomic status, education, employment, social support networks, and neighborhood characteristics. 4 These social factors have a more significant collective impact on health and health outcomes than health behavior, health care, and the physical environment. 17,18 SDoH, especially poverty, structural racism, and discrimination, are the primary drivers of health inequities. 19,20

Economic prosperity can provide individuals access to resources to avoid or buffer exposure to health risks. 21 Research shows that individuals with higher incomes consistently experience better health outcomes than individuals with low incomes and those living in poverty. 22 Poverty affects health by limiting access to proper nutrition and healthy foods; shelter; safe neighborhoods to learn, live, and work; clean air and water; utilities; and other elements that define an individual’s standard of living. Individuals who live in low-income or high-poverty neighborhoods are likely to experience poor health due to a combination of these factors. 23,24

Violence is also more prevalent in areas with greater poverty. From 2008 to 2012, individuals in households at or below the poverty level experienced more than double the rate of violent victimization than individuals in high-income households. 25 This pattern of victimization by violent behavior was consistent for both Black and white individuals. It significantly impacts the victim’s family and perpetrator’s family (through incarceration).

Because they intersect with so many SDoH, poverty and low-income status dramatically affects life expectancy. 26 Education and its socioeconomic status correlate to income and wealth. These have powerful associations with life expectancy for both sexes and all races at all ages. Students from families with low income are five times more likely to drop out of high school than students from families with high income. 27 In 2008, the life expectancy among U.S. adult men and women with fewer than 12 years of education was not much better than the life expectancy among all adults in the 1950s and 1960s. 28

Poverty affects individuals insidiously in other ways that we are just beginning to understand. Mental illness, chronic health conditions, and substance use disorders are all more prevalent in populations with low income. 29 Poor nutrition, toxic exposures (e.g., lead), and elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol are factors associated with poverty that may have lasting effects on children beginning before birth and continuing after birth. These effects, which can influence cognitive development and chronic disease development, are dose-dependent (i.e., the duration of exposure matters). 30,31,32 For example, the greater the number of years a child spends living in poverty, the more elevated the child’s overnight cortisol level and the more dysregulated the child’s cardiovascular response to acute stressors. 31 Impaired development of the nervous system affects cognitive and socioemotional development and increases the risk of behavioral challenges, adverse health behaviors, and poor school performance. 31,32 Recent studies have even identified a strong association between pediatric suicide and county-level poverty rates. 33

However, the effects of poverty are not predictably uniform. Longitudinal studies of health behavior describe positive (e.g., tobacco use cessation) and negative (e.g., decrease in physical activity) health behavior trends in populations with lower and higher socioeconomic status. However, there is a socioeconomic gradient in health improvement. In other words, populations with lower socioeconomic status lag behind populations with higher socioeconomic status in positive gains from health behavior trends. Health behaviors are important in that they account for differences in mortality. 34 The fact that positive changes in health behaviors are possible despite the challenges of poverty points to the importance of developing and implementing interventions that promote healthy behaviors in populations with low income.

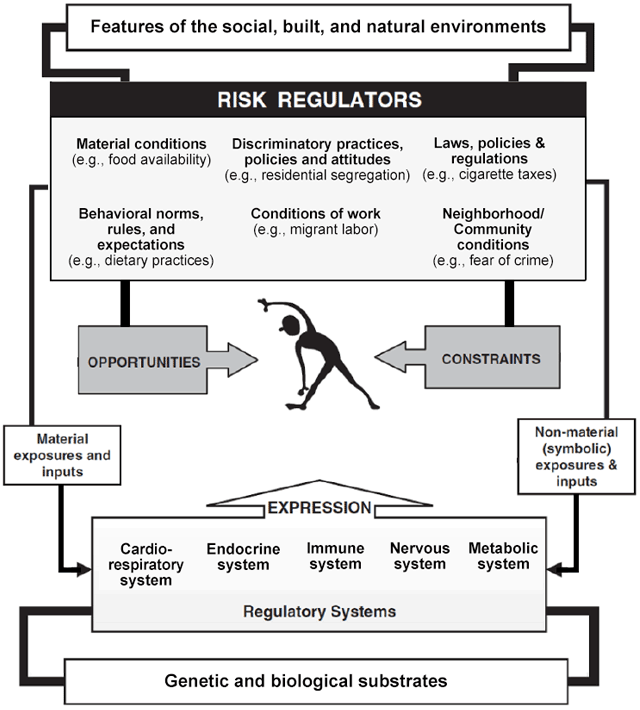

Risk Regulators and Intervention

Poverty affects health in many different ways through complex mechanisms that we are just beginning to understand and describe. Living in poverty does not necessarily predetermine poor health. 35 Poverty will not “cause” a disease. Instead, poverty affects both the likelihood that an individual will have risk factors for disease and its ability and opportunity to prevent and manage disease. An individual’s health outcomes (a physiologic expression) ultimately will be influenced by genetic and environmental factors, as well as health behaviors – all of which may be affected by poverty. Material conditions, discriminatory practices, neighborhood conditions, behavioral norms, work conditions, as well as laws, policies, and regulations associated with poverty make it a “risk regulator.” 35 This means that poverty functions as a control parameter at a system level to influence the probability of exposure to key risk factors (e.g., behaviors, environmental risks) that lead to disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1: An Illustration of Risk Regulators in Social and Biological Context

Reprinted with permission from Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1650-1671.

Thinking of poverty as a risk regulator rather than a rigid determinant of health allows family physicians to relinquish the feeling of helplessness when providing medical care to families and individuals with low income.

Family physicians are uniquely positioned to devise solutions to mitigate the development of risk factors that lead to disease and the conditions unique to populations with low income that interfere with effective disease prevention and management. They can boost an individual or family’s “host resistance” to the health effects of poverty and tap into a growing array of aligned resources that provide patients and families with tangible solutions so that health maintenance can be a realistic goal.

Role of the Family Physician

Community-Oriented Primary Care (COPC)

Strong primary care teams are critical in the care of patients with low income. These populations often have higher rates of chronic disease and difficulty navigating health care systems. They benefit from care coordination and team-based care that addresses medical and socioeconomic needs.

In the United States, there is a move toward increased payment from government and commercial payers to offset the cost of providing coordinated and team-based care. Some payment models provide shared savings or care coordination payments in addition to traditional fee-for-service reimbursement. The practice transformations from COPC and payment models based on targets and meaningful use alter how we approach patient panels and communities. 36 The rationale behind alternative payment models – particularly regarding the care of lower socioeconomic populations – is that significant cost savings can be realized when care moves toward prevention and self-management and away from crisis-driven, fragmented care provided in the emergency department or a hospital setting. By recognizing and treating disease earlier – and actively partnering with local public health services like health educators, community health workers, and outreach services – family physicians can help prevent costly, avoidable complications and reduce the total cost of care.

Community Responsive Care

Care team members can positively affect the health of patients with low income by creating a welcoming, nonjudgmental environment that supports a long-standing therapeutic relationship built on trust. Familiarity with the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care can prepare practices and institutions to provide care in a manner that promotes health equity. 37

Patients with low income may be unintentionally shamed by the care team when their behaviors are seen as evidence of being “noncompliant” (e.g., missing appointments, not adhering to a medical regimen, not getting tests done). These patients may not be comfortable sharing information about the challenges that lead to their “noncompliant” behaviors. For example, a patient with low income may arrive 15 minutes late to an appointment because they have to rely on someone else for transportation. A patient may not take prescribed medication because it is too expensive. A patient may not get tests done because their employer will not allow time off from work. A patient may not understand printed care instructions because of low-literacy skills. Such patients may be turned away by staff because their tardiness disrupts the schedule, or they may even be dismissed from the practice altogether because of repeated noncompliance. Physicians and care team members should learn why the patient was noncompliant and promote an atmosphere of tolerance and adaptation.

Patients with low socioeconomic status and other marginalized populations rarely respond well to dictation from health care professionals. Instead, interventions that rely on peer-to-peer storytelling or coaching are more effective in overcoming cognitive resistance to positive health behavior changes. 38 Physicians and care team members can identify local groups that provide peer-to-peer support. Such activities are typically hosted by local hospitals, faith-based organizations, health departments, or senior centers.

Screen for Socioeconomic Challenges

Family physicians regularly screen for risk factors for disease. Screening to identify patients’ socioeconomic challenges and other SDoH can be incorporated into practices using EveryONE Project tools. Once socioeconomic challenges are identified, physicians and their care teams can work with patients to design achievable, sustainable treatment plans. The simple question, “Do you (ever) have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?” has a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 60% in predicting poverty. 39 A casual inquiry about the cost of a patient’s medications is another way to start a conversation about socioeconomic obstacles to care.

A patient’s home and neighborhood affect health. 40 The care team should ask the patient whether their home is adequate to support healthy behaviors. For example, crowding, infestations, and lack of utilities are all risk factors for disease. Knowing that a patient is homeless or has poor, inadequate housing will help guide care.

Set Priorities and Make a Realistic Plan of Action

Family physicians direct the therapeutic process by working with the patient and care team to identify priorities so treatment goals are clear and achievable. In many cases, suspending a “fix everything right now” agenda in favor of a treatment plan of small steps that incorporate shared decision making can help this process. It is likely that a patient with low income will not have the resources (e.g., on-demand transportation, forgiving work schedule, available child care) to comply with an ideal treatment plan. Formulating a treatment plan that makes sense for the patient’s life circumstances is vital to success.

For example, for a patient with limited means and multiple chronic conditions – including hypertension and diabetes – start by addressing these conditions. Colon cancer screening or a discussion about beginning statin therapy can come later. It may be easier for this patient to adhere to an insulin regimen involving vials and syringes instead of insulin pens, which are much more expensive. The “best” medication for a patient with low income is the one that the patient can afford and self-administer reliably. Celebrate success with each small step that takes a patient closer to disease control and improved self-management.

Help Newly Insured Patients Navigate the Health Care System

In many states, the expansion of Medicaid has allowed individuals and families with low income to become insured – perhaps for the first time. A newly insured individual with low income will not necessarily know how or when to make, keep, or reschedule an appointment; develop a relationship with a family physician; manage medication refills; or obtain referrals. They may be embarrassed to reveal this lack of knowledge to the care team. Physicians and care team members can help by providing orientation to newly insured patients within the practice. For example, ensure that all patients know where to pick up medication, how to take it and why, when to return for a follow-up visit and why, and how to follow their treatment plan from one appointment to the next. Without this type of compassionate intervention, patients may revert to an old pattern of seeking crisis-driven care often provided by the emergency department or a local hospital.

Provide Material Support to Families with Low Income

Resources that make it easier for busy physicians to provide support to families with low income include the following:

● Reach Out and Read is a program that helps clinicians provide books for parents to take home to read to their children. Studies have shown that Reach Out and Read improve children’s language skills. 41

● 2-1-1 is a free, confidential service that patients or staff can access 24 hours a day by phone. 2-1-1 is staffed by community resource specialists who can connect patients to resources such as food, clothing, shelter, utility bill relief, social services, and even employment opportunities. Follow-up calls are made to ensure clients connect successfully with the resource referrals.

● The National Domestic Violence Hotline is staffed 24 hours a day by trained advocates who provide confidential help and information to patients who are experiencing domestic violence.

Local hospitals, health departments, and faith-based organizations often are connected to community health resources that offer services such as installing safety equipment in homes; providing food resources; facilitating behavioral health evaluation and treatment; and providing transportation, vaccinations, and other benefits to individuals and families with low income.

Practices can make a resource folder of information about local community services that can be easily accessed when taking care of patients in need. This simple measure incorporates community resources into the everyday workflow of patient care, thus empowering the care team.

Participate in Research that Produces Relevant Evidence

Much of the research about the effects of poverty on health is limited to identifying health disparities. This is insufficient. Research that evaluates specific interventions is needed to gain insight into what effectively alleviates poverty’s effects on health care delivery and outcomes. Family physicians can serve a critical role in this research because we have close relationships with patients with low income. 42

Advocate on Behalf of Neighborhoods and Communities with Low Income

Family physicians are community leaders, so we can advocate effectively for initiatives that improve the quality of life in neighborhoods with low income. Some forms of advocacy are apparent, such as promoting a state’s expansion of Medicaid. Other efforts may be specific to the community served. For example, a vacant lot can be converted to a basketball court or soccer field. A community center can expand programs that involve peer-to-peer health coaching. A walking program can be started among residents in a public housing unit. Collaboration with local law enforcement agencies can foster the community’s trust and avoid the potential for oppression. 43

Family physicians have local partners in advocacy, so we do not have to act in isolation. As a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), nonprofit hospitals regularly report community needs assessments and work with local health departments to establish action plans that address identified needs. A Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) reflects a specific community’s perception of need, and each action plan outlines multi-sectoral solutions to meet local health needs. Local CHNAs are typically available online, as are the associated action plans. Family physicians can use information in the CHNA to access local health care leadership and join aligned forces in the communities we serve, thereby supporting the AAFP’s vision of achieving optimal health for everyone.

1. Sherin K, Adebanjo T, Jani A. Social determinants of health: family physicians’ leadership role. Am Fam Physician . 2019;99(8):476-477.

2. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation. Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization (WHO). Accessed March 22, 2021. www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/csdh_finalreport_2008.pdf

3. Kovach KA, Reid K, Grandmont J, et al. How engaged are family physicians in addressing the social determinants of health? A survey supporting the American Academy of Family Physician’s health equity environmental scan. Health Equity . 2019;3(1):449-457.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Advancing health equity by addressing the social determinants of health in family medicine (position paper). Accessed March 22, 2021.

5. World Vision. What is poverty? It’s not as simple as you think. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.worldvision.ca/stories/child-sponsorship/what-is-poverty#:~:text=1.-,What%20is%20the%20definition%20of%20poverty%3F,care%2C%20education%20and%20even%20transportation

6. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2020 poverty guidelines. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://aspe.hhs.gov/2020-poverty-guidelines

7. United States Census Bureau. Income, poverty and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2019. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/income-poverty.html

8. United States Department of Agriculture. SNAP special rules for the elderly or disabled. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligibility/elderly-disabled-special-rules

9. U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Federal poverty level (FPL). Accessed March 22, 2021. www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/

10. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav . 1995;Spec No:80-94.

11. Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. Future Child . 1997;7(2):55-71.

12. Berkman LF, Kawachi I. A historical framework for social epidemiology. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology . New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014.

13. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav . 2010;51 Suppl:S28-S40.

14. Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med . 2002;55(1):125-139.

15. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Mapping life expectancy. Short distances to large gaps in health. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2015/09/city-maps.html

16. Schoen C, Radley D, Riley P, et al. Health care in the two Americas. Findings from the Scorecard on State Health System Performance for Low-Income Populations, 2013. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2013_sep_1700_schoen_low_income_scorecard_full_report_final_v4.pdf

17. Booske BC, Athens JK, Kindig DA, Park H, Remington PL. County health rankings working paper. Different perspectives for assigning weights to determinants of health. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf

18. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. County Health Rankings model. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/county-health-rankings-model

19. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav . 2010;51 Suppl:S28-S40.

20. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Communities in action. Pathways to health equity. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.nap.edu/catalog/24624/communities-in-action-pathways-to-health-equity

21. Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The Community Guide’s model for linking the social environment to health. Am J Prev Med . 2003;24(3 Suppl):12-20.

22. Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology . New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000.

23. Riste L, Khan F, Cruickshank K. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in all ethnic groups, including Europeans, in a British inner city: relative poverty, history, inactivity, or 21st century Europe? Diabetes Care . 2001;24(8):1377-1383.

24. Healthy People 2030. Social determinants of health. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

25. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Household poverty and nonfatal violent victimization, 2008-2012. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5137

26. Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA . 2016;315(16):1750-1766.

27. National Center for Education Statistics. Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: 1972–2009. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2012/2012006.pdf

28. Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, et al. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1803-1813.

29. Walker ER, Druss BG. Cumulative burden of comorbid mental disorders, substance use disorders, chronic medical conditions, and poverty on health among adults in the United States. Psychol Health Med . 2017;22(6):727-735.

30. Evans GW, Kim P. Childhood poverty and health: cumulative risk exposure and stress dysregulation. Psychol Sci . 2007;18(11):953-957.

31. Lipina SJ, Colombo JA. Poverty and Brain Development During Childhood: An Approach from Cognitive Psychology and Neuroscience . Human Brain Development Series. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

32. Farah MJ, Noble KG, Hurt H. Poverty, privilege, and brain development: empirical findings and ethical implications. In: Illes J, ed. Neuroethics: Defining the Issues in Theory, Practice, and Policy . New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

33. Hoffmann JA, Farrell CA, Monuteaux MC, et al. Association of pediatric suicide with county-level poverty in the United States, 2007-2016. JAMA Pediatr . 2020;174(3):287-294.

34. Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA . 2010;303(12):1159-1166.

35. Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med . 2006;62(7):1650-1671.

36. American Academy of Family Physicians. Integration of primary care and public health (position paper). Accessed March 24, 2021. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/integration-primary-care.html

37. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National CLAS Standards. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas

38. Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, et al. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med . 2011;154(2):77-84.

39. Brcic V, Eberdt C, Kaczorowski J. Development of a tool to identify poverty in a family practice setting: a pilot study. Int J Family Med . 2011;2011:812182.

40. Braveman P, Dekker M, Egerter S, Sadegh-Nobari T, Pollack C. Housing and health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/mh/files/housingandhealth.pdf

41. Zuckerman B. Promoting early literacy in pediatric practice: twenty years of Reach Out and Read. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1660-1665.

42. O’Campo P, Dunn JR, eds. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Towards a Science of Change . New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

43. President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Interim report of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Office of Community-Oriented Policing Services. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://cdpsdocs.state.co.us/ccjj/meetings/2015/2015-03-13_CCJJ_Presidents-21CentCommPolicingTF-InterimReport.pdf

(2015 COD) (January 2022 COD)

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

Exploring the impact of housing insecurity on the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the United Kingdom: a qualitative systematic review

- Emma S. Hock 1 ,

- Lindsay Blank 1 ,

- Hannah Fairbrother 1 ,

- Mark Clowes 1 ,

- Diana Castelblanco Cuevas 1 ,

- Andrew Booth 1 ,

- Amy Clair 2 &

- Elizabeth Goyder 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 2453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

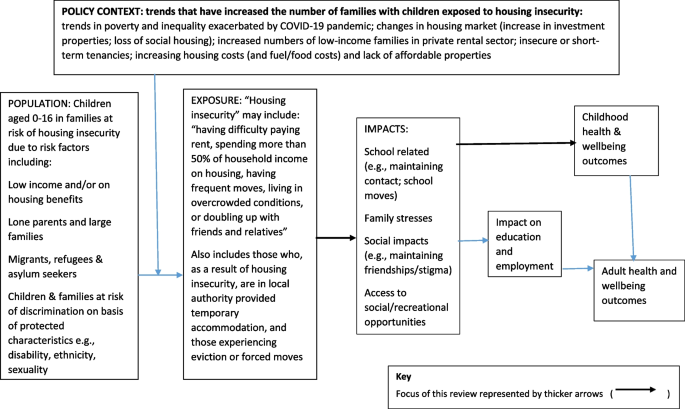

Housing insecurity can be understood as experiencing or being at risk of multiple house moves that are not through choice and related to poverty. Many aspects of housing have all been shown to impact children/young people’s health and wellbeing. However, the pathways linking housing and childhood health and wellbeing are complex and poorly understood.

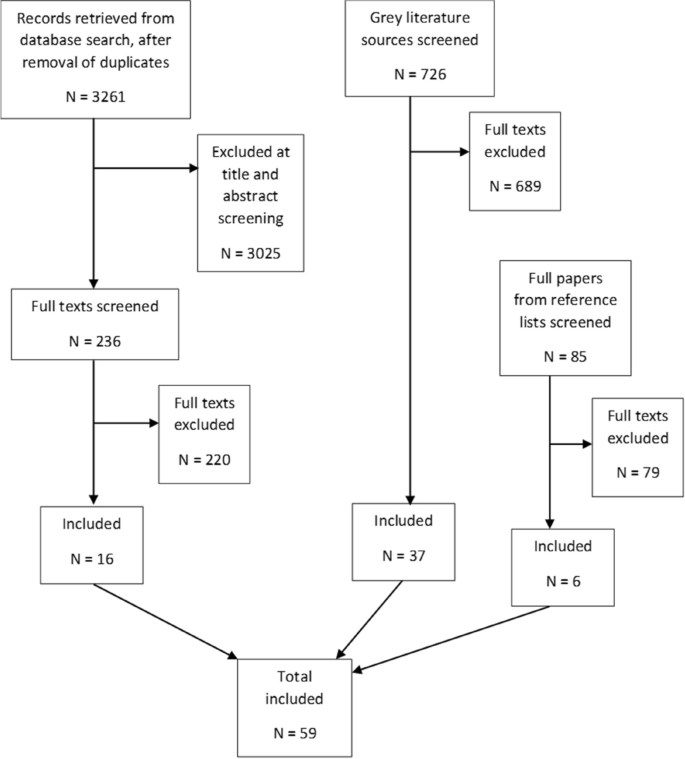

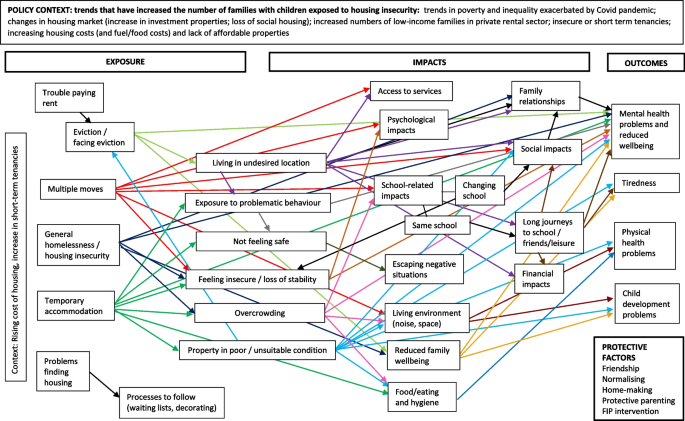

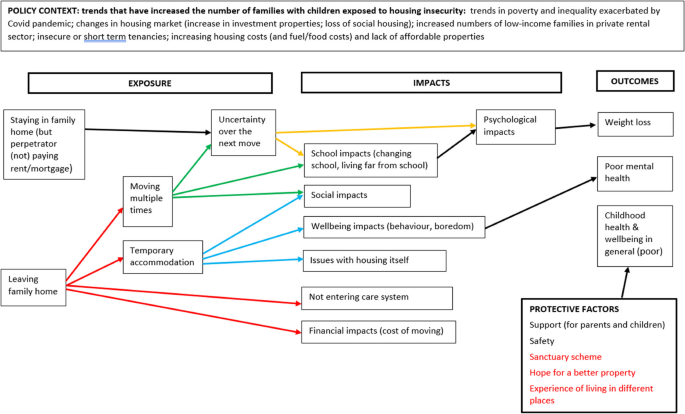

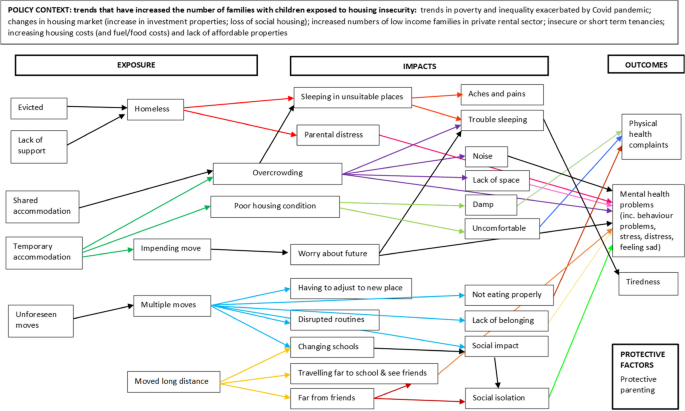

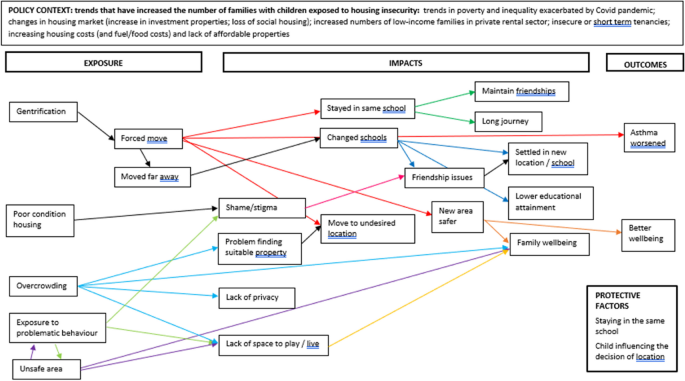

We undertook a systematic review synthesising qualitative data on the perspectives of children/young people and those close to them, from the United Kingdom (UK). We searched databases, reference lists, and UK grey literature. We extracted and tabulated key data from the included papers, and appraised study quality. We used best fit framework synthesis combined with thematic synthesis, and generated diagrams to illustrate hypothesised causal pathways.

We included 59 studies and identified four populations: those experiencing housing insecurity in general (40 papers); associated with domestic violence (nine papers); associated with migration status (13 papers); and due to demolition-related forced relocation (two papers). Housing insecurity took many forms and resulted from several interrelated situations, including eviction or a forced move, temporary accommodation, exposure to problematic behaviour, overcrowded/poor-condition/unsuitable property, and making multiple moves. Impacts included school-related, psychological, financial and family wellbeing impacts, daily long-distance travel, and poor living conditions, all of which could further exacerbate housing insecurity. People perceived that these experiences led to mental and physical health problems, tiredness and delayed development. The impact of housing insecurity was lessened by friendship and support, staying at the same school, having hope for the future, and parenting practices. The negative impacts of housing insecurity on child/adolescent health and wellbeing may be compounded by specific life circumstances, such as escaping domestic violence, migration status, or demolition-related relocation.

Housing insecurity has a profound impact on children and young people. Policies should focus on reducing housing insecurity among families, particularly in relation to reducing eviction; improving, and reducing the need for, temporary accommodation; minimum requirements for property condition; and support to reduce multiple and long-distance moves. Those working with children/young people and families experiencing housing insecurity should prioritise giving them optimal choice and control over situations that affect them.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The impacts of socioeconomic position in childhood on adult health outcomes and mortality are well documented in quantitative analyses (e.g., [ 1 ]). Housing is a key mechanism through which social and structural inequalities can impact health [ 2 ]. The impact of housing conditions on child health are well established [ 3 ]. Examining the wellbeing of children and young people within public health overall is of utmost importance [ 4 ]. Children and young people (and their families) who are homeless are a vulnerable group with particular difficulty in accessing health care and other services, and as such, meeting their needs should be a priority [ 5 ].

An extensive and diverse evidence base captures relationships between housing and health, including both physical and mental health outcomes. Much of the evidence relates to the quality of housing and specific aspects of poor housing including cold and damp homes, poorly maintained housing stock or inadequate housing leading to overcrowded accommodation [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. The health impacts of housing insecurity, together with the particular vulnerability of children and young people to the effects of not having a secure and stable home environment, continue to present a cause for increased concern [ 7 , 8 , 11 , 14 ]. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Reviews (PHR) Programme commissioned the current review in response to concerns about rising levels of housing insecurity and the impact of housing insecurity on the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the United Kingdom (UK).

Terminology and definitions related to housing insecurity

Numerous diverse terms are available to define housing insecurity, with no standard definition or validated instrument. For the purpose of our review, we use the terminology and definitions used by the Children’s Society, which are comprehensive and based directly on research with children that explores the relationship between housing and wellbeing [ 15 ]. They use the term “housing insecurity” for those experiencing and at risk of multiple moves that are (i) not through choice and (ii) related to poverty [ 15 ]. This reflects their observation that multiple moves may be a positive experience if they are by choice and for positive reasons (e.g., employment opportunities; moves to better housing or areas with better amenities). This definition also acknowledges that the wider health and wellbeing impacts of housing insecurity may be experienced by families that may not have experienced frequent moves but for whom a forced move is a very real possibility. The Children’s Society definition of housing insecurity encompasses various elements (see Table 1 ).

Housing insecurity in the UK today – the extent of the problem

Recent policy and research reports from multiple organisations in the UK highlight a rise in housing insecurity among families with children [ 19 , 22 , 23 ]. Housing insecurity has grown following current trends in the cost and availability of housing, reflecting in particular the rapid increase in the number of low-income families with children in the private rental sector [ 19 , 22 , 24 ], where housing tenures are typically less secure. The ending of a tenancy in the private rental sector was the main cause of homelessness given in 15,500 (27% of claims) of applications for homelessness assistance in 2017/18, up from 6,630 (15% of claims) in 2010/11 for example [ 25 ]. The increased reliance on the private rented sector for housing is partly due to a lack of social housing and unaffordability of home ownership [ 23 ]. The nature of tenure in the private rental sector and gap between available benefits and housing costs means even low-income families that have not experienced frequent moves may experience the negative impacts of being at persistent risk of having to move [ 26 ]. Beyond housing benefit changes, other changes to the social security system have been linked with increased housing insecurity. The roll-out of Universal Credit Footnote 1 , with its built-in waits for payments, has been linked with increased rent arrears [ 27 , 28 ]. The introduction of the benefit cap, which limits the amount of social security payments a household can receive, disproportionately affects housing support and particularly affecting lone parents [ 29 , 30 , 31 ].

The increase in families experiencing housing insecurity, including those living with relatives or friends (the ‘hidden homeless’) and those in temporary accommodation provided by local authorities, are a related consequence of the lack of suitable or affordable rental properties, which is particularly acute for lone parents and larger families. The numbers of children and young people entering the social care system or being referred to social services because of family housing insecurity contributes further evidence on the scale and severity of the problem [ 32 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated housing insecurity in the UK [ 24 ], with the impacts continuing to be felt. In particular, the pandemic increased financial pressures on families (due to loss of income and increased costs for families with children/young people at home). These financial pressures were compounded by a reduction in informal temporary accommodation being offered by friends and family due to social isolation precautions [ 24 ]. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the risks to health posed by poor housing quality (including overcrowding) and housing insecurity [ 24 , 33 ]. Recent research with young people in underserved communities across the country also highlighted their experience of the uneven impact of COVID-19 for people in contrasting housing situations [ 34 ].