- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Assessing student writing, what does it mean to assess writing.

- Suggestions for Assessing Writing

Means of Responding

Rubrics: tools for response and assessment, constructing a rubric.

Assessment is the gathering of information about student learning. It can be used for formative purposes−−to adjust instruction−−or summative purposes: to render a judgment about the quality of student work. It is a key instructional activity, and teachers engage in it every day in a variety of informal and formal ways.

Assessment of student writing is a process. Assessment of student writing and performance in the class should occur at many different stages throughout the course and could come in many different forms. At various points in the assessment process, teachers usually take on different roles such as motivator, collaborator, critic, evaluator, etc., (see Brooke Horvath for more on these roles) and give different types of response.

One of the major purposes of writing assessment is to provide feedback to students. We know that feedback is crucial to writing development. The 2004 Harvard Study of Writing concluded, "Feedback emerged as the hero and the anti-hero of our study−powerful enough to convince students that they could or couldn't do the work in a given field, to push them toward or away from selecting their majors, and contributed, more than any other single factor, to students' sense of academic belonging or alienation" (http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~expos/index.cgi?section=study).

Source: Horvath, Brooke K. "The Components of Written Response: A Practical Synthesis of Current Views." Rhetoric Review 2 (January 1985): 136−56. Rpt. in C Corbett, Edward P. J., Nancy Myers, and Gary Tate. The Writing Teacher's Sourcebook . 4th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000.

Suggestions for Assessing Student Writing

Be sure to know what you want students to be able to do and why. Good assessment practices start with a pedagogically sound assignment description and learning goals for the writing task at hand. The type of feedback given on any task should depend on the learning goals you have for students and the purpose of the assignment. Think early on about why you want students to complete a given writing project (see guide to writing strong assignments page). What do you want them to know? What do you want students to be able to do? Why? How will you know when they have reached these goals? What methods of assessment will allow you to see that students have accomplished these goals (portfolio assessment assigning multiple drafts, rubric, etc)? What will distinguish the strongest projects from the weakest?

Begin designing writing assignments with your learning goals and methods of assessment in mind.

Plan and implement activities that support students in meeting the learning goals. How will you support students in meeting these goals? What writing activities will you allow time for? How can you help students meet these learning goals?

Begin giving feedback early in the writing process. Give multiple types of feedback early in the writing process. For example, talking with students about ideas, write written responses on drafts, have students respond to their peers' drafts in process, etc. These are all ways for students to receive feedback while they are still in the process of revising.

Structure opportunities for feedback at various points in the writing process. Students should also have opportunities to receive feedback on their writing at various stages in the writing process. This does not mean that teachers need to respond to every draft of a writing project. Structuring time for peer response and group workshops can be a very effective way for students to receive feedback from other writers in the class and for them to begin to learn to revise and edit their own writing.

Be open with students about your expectations and the purposes of the assignments. Students respond better to writing projects when they understand why the project is important and what they can learn through the process of completing it. Be explicit about your goals for them as writers and why those goals are important to their learning. Additionally, talk with students about methods of assessment. Some teachers have students help collaboratively design rubrics for the grading of writing. Whatever methods of assessment you choose, be sure to let students in on how they will be evaluated.

Do not burden students with excessive feedback. Our instinct as teachers, especially when we are really interested in students´ writing is to offer as many comments and suggestions as we can. However, providing too much feedback can leave students feeling daunted and uncertain where to start in terms of revision. Try to choose one or two things to focus on when responding to a draft. Offer students concrete possibilities or strategies for revision.

Allow students to maintain control over their paper. Instead of acting as an editor, suggest options or open-ended alternatives the student can choose for their revision path. Help students learn to assess their own writing and the advice they get about it.

Purposes of Responding We provide different kinds of response at different moments. But we might also fall into a kind of "default" mode, working to get through the papers without making a conscious choice about how and why we want to respond to a given assignment. So it might be helpful to identify the two major kinds of response we provide:

- Formative Response: response that aims primarily to help students develop their writing. Might focus on confidence-building, on engaging the student in a conversation about her ideas or writing choices so as to help student to see herself as a successful and promising writer. Might focus on helping student develop a particular writing project, from one draft to next. Or, might suggest to student some general skills she could focus on developing over the course of a semester.

- Evaluative Response: response that focuses on evaluation of how well a student has done. Might be related to a grade. Might be used primarily on a final product or portfolio. Tends to emphasize whether or not student has met the criteria operative for specific assignment and to explain that judgment.

We respond to many kinds of writing and at different stages in the process, from reading responses, to exercises, to generation or brainstorming, to drafts, to source critiques, to final drafts. It is also helpful to think of the various forms that response can take.

- Conferencing: verbal, interactive response. This might happen in class or during scheduled sessions in offices. Conferencing can be more dynamic: we can ask students questions about their work, modeling a process of reflecting on and revising a piece of writing. Students can also ask us questions and receive immediate feedback. Conference is typically a formative response mechanism, but might also serve usefully to convey evaluative response.

- Written Comments on Drafts

- Local: when we focus on "local" moments in a piece of writing, we are calling attention to specifics in the paper. Perhaps certain patterns of grammar or moments where the essay takes a sudden, unexpected turn. We might also use local comments to emphasize a powerful turn of phrase, or a compelling and well-developed moment in a piece. Local commenting tends to happen in the margins, to call attention to specific moments in the piece by highlighting them and explaining their significance. We tend to use local commenting more often on drafts and when doing formative response.

- Global: when we focus more on the overall piece of writing and less on the specific moments in and of themselves. Global comments tend to come at the end of a piece, in narrative-form response. We might use these to step back and tell the writer what we learned overall, or to comment on a pieces' general organizational structure or focus. We tend to use these for evaluative response and often, deliberately or not, as a means of justifying the grade we assigned.

- Rubrics: charts or grids on which we identify the central requirements or goals of a specific project. Then, we evaluate whether or not, and how effectively, students met those criteria. These can be written with students as a means of helping them see and articulate the goals a given project.

Rubrics are tools teachers and students use to evaluate and classify writing, whether individual pieces or portfolios. They identify and articulate what is being evaluated in the writing, and offer "descriptors" to classify writing into certain categories (1-5, for instance, or A-F). Narrative rubrics and chart rubrics are the two most common forms. Here is an example of each, using the same classification descriptors:

Example: Narrative Rubric for Inquiring into Family & Community History

An "A" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, engaging readers throughout. The form and structure are appropriate for the purpose(s) and audience(s) of the piece. The final product is virtually error-free. The piece seamlessly weaves in several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial draft - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "B" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, and usually engages readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s) of the piece, though the organization may not be tight in a couple places. The final product includes a few errors, but these do no interfere with readers' comprehension. The piece effectively, if not always seamlessly, weaves several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. One area of research may not be as strong as the other two. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial drafts - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "C" project demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows audience awareness, sometimes engaging readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s), but the organization breaks down at times. The piece includes several, apparent errors, which at times compromises the clarity of the piece. The piece incorporates other voices, drawn from at least two kinds of research, but in a generally forced or awkward way. There is unevenness in the quality and appropriateness of the research. Drafts - at least one beyond the initial draft - show some evidence of revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter show some reflection and growth in awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "D" project discusses a public event and a family/community, but the connections may not be clear. It shows little audience awareness. The form and structure is poorly chosen or poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, which regularly compromise the comprehensibility of the piece. There is an attempt to incorporate other voices, but this is done awkwardly or is drawn from incomplete or inappropriate research. There is little evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show little reflection or growth.

An "F" project is not responsive to the prompt. It shows little or no audience awareness. The purpose is unclear and the form and structure are poorly chosen and poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, compromising the clarity of the piece throughout. There is little or no evidence of research. There is little or no evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show no reflection or growth.

Chart Rubric for Community/Family History Inquiry Project

All good rubrics begin (and end) with solid criteria. We always start working on rubrics by generating a list - by ourselves or with students - of what we value for a particular project or portfolio. We generally list far more items than we could use in a single rubric. Then, we narrow this list down to the most important items - between 5 and 7, ideally. We do not usually rank these items in importance, but it is certainly possible to create a hierarchy of criteria on a rubric (usually by listing the most important criteria at the top of the chart or at the beginning of the narrative description).

Once we have our final list of criteria, we begin to imagine how writing would fit into a certain classification category (1-5, A-F, etc.). How would an "A" essay differ from a "B" essay in Organization? How would a "B" story differ from a "C" story in Character Development? The key here is to identify useful descriptors - drawing the line at appropriate places. Sometimes, these gradations will be precise: the difference between handing in 80% and 90% of weekly writing, for instance. Other times, they will be vague: the difference between "effective revisions" and "mostly effective revisions", for instance. While it is important to be as precise as possible, it is also important to remember that rubric writing (especially in writing classrooms) is more art than science, and will never - and nor should it - stand in for algorithms. When we find ourselves getting caught up in minute gradations, we tend to be overlegislating students´- writing and losing sight of the purpose of the exercise: to support students' development as writers. At the moment when rubric-writing thwarts rather than supports students' writing, we should discontinue the practice. Until then, many students will find rubrics helpful -- and sometimes even motivating.

Center for Teaching

Assessing student learning.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

Assessment is more than grading, assessment plans, methods of student assessment, generative and reflective assessment, teaching guides related to student assessment, references and additional resources.

Student assessment is, arguably, the centerpiece of the teaching and learning process and therefore the subject of much discussion in the scholarship of teaching and learning. Without some method of obtaining and analyzing evidence of student learning, we can never know whether our teaching is making a difference. That is, teaching requires some process through which we can come to know whether students are developing the desired knowledge and skills, and therefore whether our instruction is effective. Learning assessment is like a magnifying glass we hold up to students’ learning to discern whether the teaching and learning process is functioning well or is in need of change.

To provide an overview of learning assessment, this teaching guide has several goals, 1) to define student learning assessment and why it is important, 2) to discuss several approaches that may help to guide and refine student assessment, 3) to address various methods of student assessment, including the test and the essay, and 4) to offer several resources for further research. In addition, you may find helfpul this five-part video series on assessment that was part of the Center for Teaching’s Online Course Design Institute.

What is student assessment and why is it Important?

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning” (2001, p. 5). An intentional and thorough assessment of student learning is vital because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction — “Backward Design”— that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggins and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course goals. Assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred (2005, p. 18). Their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, p. 18). [1]

Not only does effective assessment provide us with valuable information to support student growth, but it also enables critically reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, argues that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students (1995). Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the intentional and meaningful development of one’s teaching philosophy and practices. According to Brookfield, referencing higher education faculty, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 17). One important lens through which we may reflect on our teaching is our student evaluations and student learning assessments. This reflection allows educators to determine where their teaching has been effective in meeting learning goals and where it has not, allowing for improvements. Student assessment, then, both develop the rationale for pedagogical choices, and enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching.

The scholarship of teaching and learning discusses two general forms of assessment. The first, summative assessment , is one that is implemented at the end of the course of study, for example via comprehensive final exams or papers. Its primary purpose is to produce an evaluation that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful for communicating final evaluations of student achievement, it does so without providing opportunities for students to reflect on their progress, alter their learning, and demonstrate growth or improvement; nor does it allow instructors to modify their teaching strategies before student learning in a course has concluded (Maki, 2002).

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning at intermediate points before any summative form. Its fundamental purpose is to help students during the learning process by enabling them to reflect on their challenges and growth so they may improve. By analyzing students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies” (Maki, 2002, p. 11). Pat Hutchings refers to as “assessment behind outcomes”: “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, p. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes all manner of coursework with feedback, discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves (Brown and Knight, 1994).

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed below) can either be summative or formative depending on when and how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in Assessing Learners in Higher Education caution against a conflation of the method (e.g., an essay) with the goal (formative or summative): “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback” (1994, p. 17). If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, but he or she does not take the requisite time or effort to provide extensive feedback to students, the assessment effectively functions as a summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions (Brown and Knight, 1994). Indeed, feedback and discussion are critical factors that distinguish between formative and summative assessment; formative assessment is only as good as the feedback that accompanies it.

It is not uncommon to conflate assessment with grading, but this would be a mistake. Student assessment is more than just grading. Assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to students and instructors about learning and teaching, respectively. Grading, on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. (2001) merely involves affixing a number or letter to an assignment, giving students only the most minimal indication of their performance relative to a set of criteria or to their peers: “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest” (Stassen et al., 2001, p. 6). Grades are only the broadest of indicators of achievement or status, and as such do not provide very meaningful information about students’ learning of knowledge or skills, how they have developed, and what may yet improve. Unfortunately, despite the limited information grades provide students about their learning, grades do provide students with significant indicators of their status – their academic rank, their credits towards graduation, their post-graduation opportunities, their eligibility for grants and aid, etc. – which can distract students from the primary goal of assessment: learning. Indeed, shifting the focus of assessment away from grades and towards more meaningful understandings of intellectual growth can encourage students (as well as instructors and institutions) to attend to the primary goal of education.

Barbara Walvoord (2010) argues that assessment is more likely to be successful if there is a clear plan, whether one is assessing learning in a course or in an entire curriculum (see also Gelmon, Holland, and Spring, 2018). Without some intentional and careful plan, assessment can fall prey to unclear goals, vague criteria, limited communication of criteria or feedback, invalid or unreliable assessments, unfairness in student evaluations, or insufficient or even unmeasured learning. There are several steps in this planning process.

- Defining learning goals. An assessment plan usually begins with a clearly articulated set of learning goals.

- Defining assessment methods. Once goals are clear, an instructor must decide on what evidence – assignment(s) – will best reveal whether students are meeting the goals. We discuss several common methods below, but these need not be limited by anything but the learning goals and the teaching context.

- Developing the assessment. The next step would be to formulate clear formats, prompts, and performance criteria that ensure students can prepare effectively and provide valid, reliable evidence of their learning.

- Integrating assessment with other course elements. Then the remainder of the course design process can be completed. In both integrated (Fink 2013) and backward course design models (Wiggins & McTighe 2005), the primary assessment methods, once chosen, become the basis for other smaller reading and skill-building assignments as well as daily learning experiences such as lectures, discussions, and other activities that will prepare students for their best effort in the assessments.

- Communicate about the assessment. Once the course has begun, it is possible and necessary to communicate the assignment and its performance criteria to students. This communication may take many and preferably multiple forms to ensure student clarity and preparation, including assignment overviews in the syllabus, handouts with prompts and assessment criteria, rubrics with learning goals, model assignments (e.g., papers), in-class discussions, and collaborative decision-making about prompts or criteria, among others.

- Administer the assessment. Instructors then can implement the assessment at the appropriate time, collecting evidence of student learning – e.g., receiving papers or administering tests.

- Analyze the results. Analysis of the results can take various forms – from reading essays to computer-assisted test scoring – but always involves comparing student work to the performance criteria and the relevant scholarly research from the field(s).

- Communicate the results. Instructors then compose an assessment complete with areas of strength and improvement, and communicate it to students along with grades (if the assignment is graded), hopefully within a reasonable time frame. This also is the time to determine whether the assessment was valid and reliable, and if not, how to communicate this to students and adjust feedback and grades fairly. For instance, were the test or essay questions confusing, yielding invalid and unreliable assessments of student knowledge.

- Reflect and revise. Once the assessment is complete, instructors and students can develop learning plans for the remainder of the course so as to ensure improvements, and the assignment may be changed for future courses, as necessary.

Let’s see how this might work in practice through an example. An instructor in a Political Science course on American Environmental Policy may have a learning goal (among others) of students understanding the historical precursors of various environmental policies and how these both enabled and constrained the resulting legislation and its impacts on environmental conservation and health. The instructor therefore decides that the course will be organized around a series of short papers that will combine to make a thorough policy report, one that will also be the subject of student presentations and discussions in the last third of the course. Each student will write about an American environmental policy of their choice, with a first paper addressing its historical precursors, a second focused on the process of policy formation, and a third analyzing the extent of its impacts on environmental conservation or health. This will help students to meet the content knowledge goals of the course, in addition to its goals of improving students’ research, writing, and oral presentation skills. The instructor then develops the prompts, guidelines, and performance criteria that will be used to assess student skills, in addition to other course elements to best prepare them for this work – e.g., scaffolded units with quizzes, readings, lectures, debates, and other activities. Once the course has begun, the instructor communicates with the students about the learning goals, the assignments, and the criteria used to assess them, giving them the necessary context (goals, assessment plan) in the syllabus, handouts on the policy papers, rubrics with assessment criteria, model papers (if possible), and discussions with them as they need to prepare. The instructor then collects the papers at the appropriate due dates, assesses their conceptual and writing quality against the criteria and field’s scholarship, and then provides written feedback and grades in a manner that is reasonably prompt and sufficiently thorough for students to make improvements. Then the instructor can make determinations about whether the assessment method was effective and what changes might be necessary.

Assessment can vary widely from informal checks on understanding, to quizzes, to blogs, to essays, and to elaborate performance tasks such as written or audiovisual projects (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight (1994) that are important to consider.

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style (1980). The American Association of Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) also has found that intensive writing is a “high impact” teaching practice likely to help students in their engagement, learning, and academic attainment (Kuh 2008).

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them.

- Essays encompass a wide array of narrative forms and lengths, from short descriptive essays to long analytical or creative ones. Shorter essays are often best suited to assess student’s understanding of threshold concepts and discrete analytical or writing skills, while longer essays afford assessments of higher order concepts and more complex learning goals, such as rigorous analysis, synthetic writing, problem solving, or creative tasks.

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments. Students need performance criteria and prompts that urge them to go beyond mere memorization and comprehension, but encourage the highest levels of learning on Bloom’s Taxonomy . This may open the possibility for essay assignments that go beyond the common summary or descriptive essay on a given topic, but demand, for example, narrative or persuasive essays or more creative projects.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is sometimes not the case. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist, or provide students to resources that will enhance their writing skills. Faculty may also encourage students to attend writing workshops at university writing centers, such as Vanderbilt University’s Writing Studio .

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been a gold standard of assessment, particularly in post-secondary education. Many educators prefer them because they can be highly effective, they can be standardized, they are easily integrated into disciplines with certification standards, and they are efficient to implement since they can allow for less labor-intensive feedback and grading. They can involve multiple forms of questions, be of varying lengths, and can be used to assess multiple levels of student learning. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams typically focus on the assessment of students’ knowledge of facts, figures, and other discrete information crucial to a course. While they can involve questioning that demands students to engage in higher order demonstrations of comprehension, problem solving, analysis, synthesis, critique, and even creativity, such exams often require more time to prepare and validate.

- Exam questions can be multiple choice, true/false, or other discrete answer formats, or they can be essay or problem-solving. For more on how to write good multiple choice questions, see this guide .

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and therefore can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. Further, when exams are offered infrequently, or when they have high stakes by virtue of their heavy weighting in course grade schemes or in student goals, they may accompany violations of academic integrity.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well on the exam? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgment and the capacities for critical meta-cognition – to learn how to learn. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both the processes and products of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student self-assessment in the classroom ensures students evaluate their performance and the process of learning that led to it. Self-assessment thus provides a sense of student ownership of their learning and can lead to greater investment and engagement. It also enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process with their peers.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is not self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor]” (1994, p. 52). Self-assessment can involve self-grading, but instructors of record retain the final authority to determine and assign grades.

- To accurately and thoroughly self-assess, students require clear learning goals for the assignment in question, as well as rubrics that clarify different performance criteria and levels of achievement for each. These rubrics may be instructor-designed, or they may be fashioned through a collaborative dialogue with students. Rubrics need not include any grade assignation, but merely descriptive academic standards for different criteria.

- Students may not have the expertise to assess themselves thoroughly, so it is helpful to build students’ capacities for self-evaluation, and it is important that they always be supplemented with faculty assessments.

- Students may initially resist instructor attempts to involve themselves in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work, or possibly because of habituation to more passive roles in the learning process. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance (1994).

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as unique as the instructor or the course. Common forms of self-assessment involve written or oral reflection on a student’s own work, including portfolio, logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, post-test reflections, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and, in return, have their own work evaluated as well. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken” (Brown and Knight, 1994, p. 52). However, it also provides students with other models of performance (e.g., different styles or narrative forms of writing), as well as the opportunity to teach, which can enable greater preparation, reflection, and meta-cognitive organization.

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Similar to self-assessment, students benefit from clear and specific learning goals and rubrics. Again, these may be instructor-defined or determined through collaborative dialogue.

- Also similar to self-assessment, it is important to not conflate peer assessment and peer grading, since grading authority is retained by the instructor of record.

- While student peer assessments are most often fair and accurate, they sometimes can be subject to bias. In competitive educational contexts, for example when students are graded normatively (“on a curve”), students can be biased or potentially game their peer assessments, giving their fellow students unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, in more cooperative teaching environments or in cases when they are friends with their peers, students may provide overly favorable evaluations. Also, other biases associated with identity (e.g., race, gender, or class) and personality differences can shape student assessments in unfair ways. Therefore, it is important for instructors to encourage fairness, to establish processes based on clear evidence and identifiable criteria, and to provide instructor assessments as accompaniments or correctives to peer evaluations.

- Students may not have the disciplinary expertise or assessment experience of the instructor, and therefore can issue unsophisticated judgments of their peers. Therefore, to avoid unfairness, inaccuracy, and limited comments, formative peer assessments may need to be supplemented with instructor feedback.

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor when possible, improves the reliability of the assessment data. It also ensures that students with diverse aptitudes and abilities can be assessed accurately and have equal opportunities to excel. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret and mis-evaluate student learning. Ultimately, they caution that, when multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement (Brown and Knight, 1994).

These are only a few of the many forms of assessment that one might use to evaluate and enhance student learning (see also ideas present in Brown and Knight, 1994). To this list of assessment forms and methods we may add many more that encourage students to produce anything from research papers to films, theatrical productions to travel logs, op-eds to photo essays, manifestos to short stories. The limits of what may be assigned as a form of assessment is as varied as the subjects and skills we seek to empower in our students. Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching has an ever-expanding array of guides on creative models of assessment that are present below, so please visit them to learn more about other assessment innovations and subjects.

Whatever plan and method you use, assessment often begins with an intentional clarification of the values that drive it. While many in higher education may argue that values do not have a role in assessment, we contend that values (for example, rigor) always motivate and shape even the most objective of learning assessments. Therefore, as in other aspects of assessment planning, it is helpful to be intentional and critically reflective about what values animate your teaching and the learning assessments it requires. There are many values that may direct learning assessment, but common ones include rigor, generativity, practicability, co-creativity, and full participation (Bandy et al., 2018). What do these characteristics mean in practice?

Rigor. In the context of learning assessment, rigor means aligning our methods with the goals we have for students, principles of validity and reliability, ethics of fairness and doing no harm, critical examinations of the meaning we make from the results, and good faith efforts to improve teaching and learning. In short, rigor suggests understanding learning assessment as we would any other form of intentional, thoroughgoing, critical, and ethical inquiry.

Generativity. Learning assessments may be most effective when they create conditions for the emergence of new knowledge and practice, including student learning and skill development, as well as instructor pedagogy and teaching methods. Generativity opens up rather than closes down possibilities for discovery, reflection, growth, and transformation.

Practicability. Practicability recommends that learning assessment be grounded in the realities of the world as it is, fitting within the boundaries of both instructor’s and students’ time and labor. While this may, at times, advise a method of learning assessment that seems to conflict with the other values, we believe that assessment fails to be rigorous, generative, participatory, or co-creative if it is not feasible and manageable for instructors and students.

Full Participation. Assessments should be equally accessible to, and encouraging of, learning for all students, empowering all to thrive regardless of identity or background. This requires multiple and varied methods of assessment that are inclusive of diverse identities – racial, ethnic, national, linguistic, gendered, sexual, class, etcetera – and their varied perspectives, skills, and cultures of learning.

Co-creation. As alluded to above regarding self- and peer-assessment, co-creative approaches empower students to become subjects of, not just objects of, learning assessment. That is, learning assessments may be more effective and generative when assessment is done with, not just for or to, students. This is consistent with feminist, social, and community engagement pedagogies, in which values of co-creation encourage us to critically interrogate and break down hierarchies between knowledge producers (traditionally, instructors) and consumers (traditionally, students) (e.g., Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009, p. 10; Weimer, 2013). In co-creative approaches, students’ involvement enhances the meaningfulness, engagement, motivation, and meta-cognitive reflection of assessments, yielding greater learning (Bass & Elmendorf, 2019). The principle of students being co-creators of their own education is what motivates the course design and professional development work Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching has organized around the Students as Producers theme.

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one and may be of assistance as you consider all of the factors that shape your assessment plan.

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

- Classroom Response Systems

- How People Learn

- Service-Learning and Community Engagement

- Syllabus Construction

- Teaching with Blogs

- Test-Enhanced Learning

- Assessing Student Learning (a five-part video series for the CFT’s Online Course Design Institute)

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Bandy, Joe, Mary Price, Patti Clayton, Julia Metzker, Georgia Nigro, Sarah Stanlick, Stephani Etheridge Woodson, Anna Bartel, & Sylvia Gale. Democratically engaged assessment: Reimagining the purposes and practices of assessment in community engagement . Davis, CA: Imagining America, 2018. Web.

Bass, Randy and Heidi Elmendorf. 2019. “ Designing for Difficulty: Social Pedagogies as a Framework for Course Design .” Social Pedagogies: Teagle Foundation White Paper. Georgetown University, 2019. Web.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ;Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31. Print.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Gelmon, Sherril B., Barbara Holland, and Amy Spring. Assessing Service-Learning and Civic Engagement: Principles and Techniques. Second Edition . Stylus, 2018. Print.

Kuh, George. High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter , American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2008. Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. Print.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Walvoord, Barbara. Assessment Clear and Simple: A Practical Guide for Institutions, Departments, and General Education. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010. Print.

Weimer, Maryellen. Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2013. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria,

VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our teaching guide here .

Photo credit

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Resources ›

- For Educators ›

- Tips & Strategies ›

Creating and Scoring Essay Tests

FatCamera / Getty Images

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Essay tests are useful for teachers when they want students to select, organize, analyze, synthesize, and/or evaluate information. In other words, they rely on the upper levels of Bloom's Taxonomy . There are two types of essay questions: restricted and extended response.

- Restricted Response - These essay questions limit what the student will discuss in the essay based on the wording of the question. For example, "State the main differences between John Adams' and Thomas Jefferson's beliefs about federalism," is a restricted response. What the student is to write about has been expressed to them within the question.

- Extended Response - These allow students to select what they wish to include in order to answer the question. For example, "In Of Mice and Men , was George's killing of Lennie justified? Explain your answer." The student is given the overall topic, but they are free to use their own judgment and integrate outside information to help support their opinion.

Student Skills Required for Essay Tests

Before expecting students to perform well on either type of essay question, we must make sure that they have the required skills to excel. Following are four skills that students should have learned and practiced before taking essay exams:

- The ability to select appropriate material from the information learned in order to best answer the question.

- The ability to organize that material in an effective manner.

- The ability to show how ideas relate and interact in a specific context.

- The ability to write effectively in both sentences and paragraphs.

Constructing an Effective Essay Question

Following are a few tips to help in the construction of effective essay questions:

- Begin with the lesson objectives in mind. Make sure to know what you wish the student to show by answering the essay question.

- Decide if your goal requires a restricted or extended response. In general, if you wish to see if the student can synthesize and organize the information that they learned, then restricted response is the way to go. However, if you wish them to judge or evaluate something using the information taught during class, then you will want to use the extended response.

- If you are including more than one essay, be cognizant of time constraints. You do not want to punish students because they ran out of time on the test.

- Write the question in a novel or interesting manner to help motivate the student.

- State the number of points that the essay is worth. You can also provide them with a time guideline to help them as they work through the exam.

- If your essay item is part of a larger objective test, make sure that it is the last item on the exam.

Scoring the Essay Item

One of the downfalls of essay tests is that they lack in reliability. Even when teachers grade essays with a well-constructed rubric, subjective decisions are made. Therefore, it is important to try and be as reliable as possible when scoring your essay items. Here are a few tips to help improve reliability in grading:

- Determine whether you will use a holistic or analytic scoring system before you write your rubric . With the holistic grading system, you evaluate the answer as a whole, rating papers against each other. With the analytic system, you list specific pieces of information and award points for their inclusion.

- Prepare the essay rubric in advance. Determine what you are looking for and how many points you will be assigning for each aspect of the question.

- Avoid looking at names. Some teachers have students put numbers on their essays to try and help with this.

- Score one item at a time. This helps ensure that you use the same thinking and standards for all students.

- Avoid interruptions when scoring a specific question. Again, consistency will be increased if you grade the same item on all the papers in one sitting.

- If an important decision like an award or scholarship is based on the score for the essay, obtain two or more independent readers.

- Beware of negative influences that can affect essay scoring. These include handwriting and writing style bias, the length of the response, and the inclusion of irrelevant material.

- Review papers that are on the borderline a second time before assigning a final grade.

- How to Study Using the Basketball Review Game

- Creating Effective Fill-in-the-Blank Questions

- Teacher Housekeeping Tasks

- 4 Tips for Effective Classroom Management

- Dealing With Trips to the Bathroom During Class

- Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time

- Collecting Homework in the Classroom

- Why Students Cheat and How to Stop Them

- Planning Classroom Instruction

- Using Cloze Tests to Determine Reading Comprehension

- 10 Strategies to Boost Reading Comprehension

- Taking Daily Attendance

- How Scaffolding Instruction Can Improve Comprehension

- Field Trips: Pros and Cons

- Assignment Biography: Student Criteria and Rubric for Writing

- 3 Poetry Activities for Middle School Students

Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

The Ultimate Essay Test Guide: Achieve Top Grades With Ease

An essay test, a fundamental tool in academic assessment, measures a student's ability to express, argue, and structure their thoughts on a given subject through written words. This test format delves deeper into a student's critical thinking and writing skills unlike other conventional exam types.

What is an Essay Test?

An essay test is a type of assessment in which a student is prompted to respond to a question or a series of questions by writing an essay.

This form of test isn’t merely about checking a student’s recall or memorization skills , but more about gauging their ability to comprehend a subject, synthesize information, and articulate their understanding effectively.

Types of Essay Tests

Essay tests can be broadly classified into two categories: Restricted Response and Extended Response .

- Restricted Response tests focus on limited aspects, requiring students to provide short, concise answers.

- Extended Response tests demand more comprehensive answers, allowing students to showcase their creativity and analytical skills.

Advantages and Limitations of an Essay Test

Essay tests offer numerous benefits but also have certain limitations. The advantages of an essay test are :

- They allow teachers to evaluate students’ abilities to organize, synthesize, and interpret information.

- They help in developing critical thinking and writing skills among students.

- They provide an opportunity for students to exhibit their knowledge and understanding of a subject in a broader context.

And the limitations of an essay test are :

- They are time-consuming to both take and grade.

- They are subject to scoring inconsistencies due to potential subjective bias.

- They may cause the students who struggle with written expression may face difficulties, and these tests may not accurately reflect the full spectrum of a student’s knowledge or understanding.

Join over 90% of students getting better grades!

That’s a pretty good statistic. Download our free all-in-one learning app and start your most successful learning journey yet. Let’s do it!

Understanding the Structure of an Essay Test

Essay tests involve a defined structure to ensure organized, coherent, and comprehensive expression of thoughts. Adhering to a specific structure can enhance your ability to answer essay questions effectively .

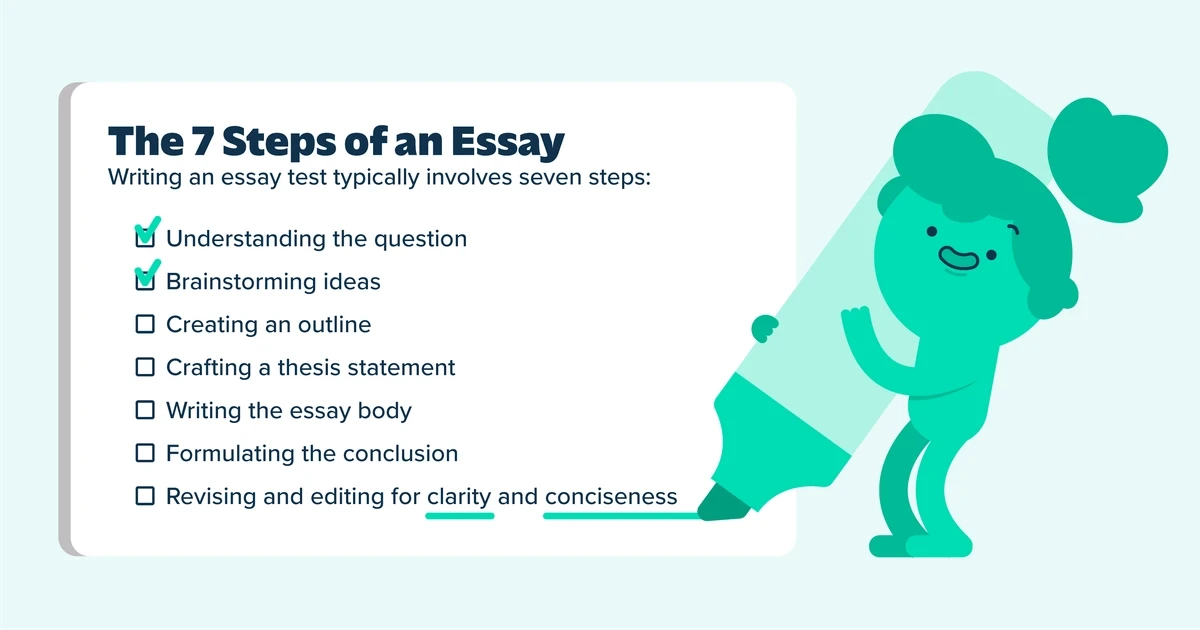

The 7 Steps of an Essay

Writing an essay test typically involves seven steps :

- Understanding the question

- Brainstorming ideas

- Creating an outline

- Crafting a thesis statement

- Writing the essay body

- Formulating the conclusion

- Revising and editing for clarity and conciseness

The First Sentence in an Essay

The initial sentence of an essay, often termed a hook , plays a crucial role.

It aims to grab the reader’s attention and provoke interest in the essay topic. It should be engaging, and relevant, and set the tone for the rest of the essay .

The 5-Paragraph Essay Format

The 5-paragraph essay format is commonly used in essay tests, providing a clear and organized approach for students to articulate their ideas. In this format, the introduction and the conclusion include 1 paragraph while the body of the essay includes 3 .

- Introduction : The introduction sets the stage, providing a brief overview of the topic and presenting the thesis statement – the central argument or point.

- Body : The body of the essay contains three paragraphs, each presenting a separate point that supports the thesis statement. Detailed explanations, evidence, and examples are included here to substantiate the points.

- Conclusion : The conclusion reiterates the thesis statement and summarizes the main points. It provides a final perspective on the topic, drawing the essay to a close.

How to Prepare for an Essay Test?

Preparing for an essay test demands a structured approach to ensure thorough understanding and effective response. Here are some strategies to make this task more manageable:

#1 Familiarize Yourself with the Terminology Used

Knowledge of key terminologies is essential. Understand the meaning of directives such as “describe”, “compare”, “contrast”, or “analyze”. Each term guides you on what is expected in your essay and helps you to answer the question accurately.

To make it easier, you can take advantage of AI technologies. While preparing for your exam, use similar essay questions as prompts and see how AI understands and evaluates the questions. If you are unfamiliar with AI, you can check out The Best Chat GPT Prompts For Essay Writing .

#2 Review and Revise Past Essays

Take advantage of past essays or essay prompts to review and revise your writing . Analyze your strengths and areas for improvement, paying attention to grammar , structure , and clarity . This process helps you refine your writing skills and identify potential pitfalls to avoid in future tests.

#3 Practice Timed Writing

Simulate test conditions by practicing timed writing . Set a specific time limit for each essay question and strive to complete it within that timeframe. This exercise builds your ability to think and write quickly , improving your efficiency during the actual test.

#4 Utilize Mnemonic Techniques

To aid in memorization and recall of key concepts or arguments, employ mnemonic techniques . These memory aids, such as acronyms, visualization, or association techniques, can help you retain important information and retrieve it during the test. Practice using mnemonics to reinforce your understanding of critical points.

Exam stress causing you sleepless nights?

Get a good night’s rest with our free teacher-verified study sets and a smart study planner to help you manage your studies effectively.

Strategies to Pass an Essay Test

Passing an essay test goes beyond understanding the topic; it also requires strategic planning and execution . Below are key strategies that can enhance your performance in an essay test.

- Read the exam paper thoroughly before diving into writing : read the entire exam paper thoroughly. Understand each question’s requirement and make a mental note of the points to be included in each response. This step will help in ensuring that no aspect of the question is overlooked.

- Answer in the First Sentence and Use the Language of the Question : Begin your essay by clearly stating your answer in the first sentence. Use the language of the question to show you are directly addressing the task. This approach ensures that your main argument is understood right from the start.

- Structure Your Essay : Adopt a logical essay structure , typically comprising an introduction, body, and conclusion. This helps in organizing your thoughts, making your argument clearer, and enhancing the readability of your essay.

- Answer in Point Form When Running Out of Time : If time is running short, present your answer in point form. This approach allows you to cover more points quickly, ensuring you don’t leave any questions unanswered.

- Write as Legibly as Possible : Your writing should be clear and easy to read. Illegible handwriting could lead to misunderstandings and may negatively impact your grades.

- Number Your Answers : Ensure your answers are correctly numbered. This helps in aligning your responses with the respective questions, making it easier for the examiner to assess your work, and reducing chances of confusion or error

- Time Yourself on Each Question : Time management is crucial in an essay test. Allocate a specific amount of time to each question, taking into account the marks they carry. Ensure you leave ample time for revising and editing your responses. Practicing this strategy can prevent last-minute rushes and result in a more polished essay.

Did you know that Vaia was rated best study app worldwide!

Frequently Asked Questions About Essay Tests

How do you answer an essay question, when taking an essay test what is the first step, what type of test is an essay test, what is the first sentence in an essay, what are the six elements of an essay.

Privacy Overview

Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

How to get started, best practices, moodle how-to guides.

Workshop Links:

- Workshop Recording (Spring 2024)

- Workshop Registration

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Holistic rubrics.

A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

Analytic/Descriptive Rubrics

An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubrics

A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of single point rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper.

Articulating thoughts through written communication— final paper.

- Above Average: The audience is able to easily identify the central message of the work and is engaged by the paper’s clear focus and relevant details. Information is presented logically and naturally. There are minimal to no distracting errors in grammar and spelling.

- Sufficient : The audience is easily able to identify the focus of the student work which is supported by relevant ideas and supporting details. Information is presented in a logical manner that is easily followed. The readability of the work is only slightly interrupted by errors.

- Developing : The audience can identify the central purpose of the student work without little difficulty and supporting ideas are present and clear. The information is presented in an orderly fashion that can be followed with little difficulty. Grammatical and spelling errors distract from the work.

- Needs Improvement : The audience cannot clearly or easily identify the central ideas or purpose of the student work. Information is presented in a disorganized fashion causing the audience to have difficulty following the author’s ideas. The readability of the work is seriously hampered by errors.

Single-Point Rubric

More examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Essay Rubric: Grading Students Correctly

- Icon Calendar 10 July 2024

- Icon Page 2897 words

- Icon Clock 14 min read

Lectures and tutors provide specific requirements for students to meet when writing essays. Basically, an essay rubric helps tutors to analyze an overall quality of compositions written by students. In this case, a rubric refers to a scoring guide used to evaluate performance based on a set of criteria and standards. As such, useful marking schemes make an analysis process simple for lecturers as they focus on specific concepts related to a writing process. Moreover, an assessment table lists and organizes all of the criteria into one convenient paper. In other instances, students use assessment tables to enhance their writing skills by examining various requirements. Then, different types of essay rubrics vary from one educational level to another. Essentially, Master’s and Ph.D. grading schemes focus on examining complex thesis statements and other writing mechanics. However, high school evaluation tables examine basic writing concepts. In turn, guidelines on a common format for writing a good essay rubric and corresponding examples provided in this article can help students to evaluate their papers before submitting them to their teachers.

General Aspects

An essay rubric refers to a way for teachers to assess students’ composition writing skills and abilities. Basically, an evaluation scheme provides specific criteria to grade assignments. Moreover, the three basic elements of an essay rubric are criteria, performance levels, and descriptors. In this case, teachers use assessment guidelines to save time when evaluating and grading various papers. Hence, learners must use an essay rubric effectively to achieve desired goals and grades, while its general example is:

What Is an Essay Rubric and Its Purpose

According to its definition, an essay rubric is a structured evaluation tool that educators use to grade students’ compositions in a fair and consistent manner. The main purpose of an essay rubric in writing is to ensure consistent and fair grading by clearly defining what constitutes excellent, good, average, and poor performance (DeVries, 2023). This tool specifies a key criteria for grading various aspects of a written text, including a clarity of a thesis statement, an overall quality of a main argument, an organization of ideas, a particular use of evidence, and a correctness of grammar and mechanics. Moreover, an assessment grading helps students to understand their strengths to be proud of and weaknesses to be pointed out and guides them in improving their writing skills (Taylor et al., 2024). For teachers, such an assessment simplifies a grading process, making it more efficient and less subjective by providing a clear standard to follow. By using an essay rubric, both teachers and students can engage in a transparent, structured, and constructive evaluation process, enhancing an overall educational experience (Stevens & Levi, 2023). In turn, the length of an essay rubric depends on academic levels, types of papers, and specific requirements, while general guidelines are:

High School

- Length: 1-2 pages

- Word Count: 300-600 words

- Length: 1-3 pages

- Word Count: 300-900 words

University (Undergraduate)

- Length: 2-4 pages

- Word Count: 600-1,200 words

Master’s

- Length: 2-5 pages

- Word Count: 600-1,500 words

- Length: 3-6 pages

- Word Count: 900-1,800 words

Note: Some elements of an essay rubric can be added, deled, or combined with each other because different types of papers, their requirements, and instructors’ choices affect a final assessment. To format an essay rubric, people create a table with criteria listed in rows, performance levels in columns, and detailed descriptors in each cell explaining principal expectations for each level of performance (Steven & Levi, 2023). Besides, the five main criteria in a rubric are thesis statement, content, organization, evidence and support, and grammar and mechanics. In turn, a good essay rubric is clear, specific, aligned with learning objectives, and provides detailed, consistent descriptors for each performance level.

Steps How to Write an Essay Rubric

In writing, the key elements of an essay rubric are clear criteria, defined performance levels, and detailed descriptors for each evaluation.

- Identify a Specific Purpose and Goals: Determine main objectives of an essay’s assignment and consider what skills and knowledge you want students to demonstrate.