School of Psychology

The School of Psychology at the University of Adelaide is home to world-class psychology researchers, educators, and practitioners. We seek to expand the capabilities of industry and improve the lives of Australians. We build on a long tradition of international excellence in our research and teaching to adapt to the big challenges facing the world.

Healthy Communities We contribute to improving the health and wellbeing of communities.

Human Cognition and Performance We work to enhance decision making and workplace performance.

Lifespan Development We strive to improve outcomes across the lifespan.

Education and Meta-Research We research our outstanding and innovative teaching practices.

Undergraduate Psychology

Postgraduate Psychology

Study Psychology with us

From the Bachelor of Psychological Science and Bachelor of Psychology (Advanced) (Honours) , to the Doctor of Philosophy and Master of Psychology options, we offer a range of high-quality undergraduate and postgraduate degrees .

At postgraduate level, we’re unique in South Australia in offering three professional master’s programs leading to registration as a psychologist (clinical, health, and organisation and human factors). You’ll also find the school has a vibrant PhD student body, with over 80 higher degree by research students studying across our various research areas.

Learn more about studying with us

Get hands-on experience in our teaching clinics

Master’s students develop real-world psychology skills at our affiliated Adelaide teaching clinics and practices: the Centre for the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression; and Ngartunna Wiltanendi.

Learn more about our teaching clinics

Psychology research

Our school’s research spans many fields of psychological inquiry but reflects particular strengths in the areas of health, disability and lifespan development, cognition and brain, and social and organisational psychology.

Learn more about our research in psychology

Learn from our talented staff

Working closely with our collaborators in the professional psychology field, they also train the next generation of psychologists at our teaching clinics and practices across Adelaide.

Learn more about our School of Psychology staff

Graduate Diploma in Psychology (GDipPsych)

Program Code GDPS

Program Faculty Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences

Academic Year 2020

These Program Rules should be read in conjunction with the University's policies ( https://www.adelaide.edu.au/policies ).

The Graduate Diploma in Psychology is a fully online offering designed for applicants who have already completed a three-year undergraduate degree at AQF Level 7 that may or may not have included psychology. Courses focus on contemporary research, theories and applications to develop critical and analytic thinking and research skills, providing broad foundational and advanced knowledge in the scientific discipline of psychology. The program is appropriate for people who want to develop knowledge and skills for enhancing their chosen career or who are preparing for further advanced studies in Psychology. The Graduate Diploma in Psychology is an AQF Level 8 qualification with a standard part-time duration of 1.7 years.

Academic Program Rules for Graduate Diploma in Psychology

There shall be a Graduate Diploma in Psychology.

Qualification Requirements

To qualify for the Graduate Diploma in Psychology, the student must complete satisfactorily a program of study consisting of 30 units, comprising: - Foundation courses to the value of 6 units - Core courses to the value of not less than 24 units.

Core Courses

To satisfy the requirements for Core Courses students must complete courses to the value of 30 units.

Foundation Courses

All of the following courses must be completed:

Published on: 12 March, 2024 | 12:26:05

DISCLAIMER: The information in this publication is current as at the date of printing and is subject to change. You can find updated information on our website at adelaide.edu.au With the aim of continual improvement the University of Adelaide is committed to regular reviews of the degrees, diplomas, certificates and courses on offer. As a result the specific programs and courses available will change from time to time. Please refer to adelaide.edu.au for the most up to date information or contact us on 1800 061 459. The University of Adelaide assumes no responsibility for the accuracy of information provided by third parties.

Australian University Provider Number PRV12105

CRICOS 00123M © The University of Adelaide.

Content generated from http://calendar.adelaide.edu.au

PSYCH 3002 - Research Methods in Psychology

- APA PsycInfo

- Google Scholar

- Find Cited Articles

- Find "Cited by" Articles

- Browsing Best Journals

- Psychology Journals

- Is it Peer Reviewed?

- Interlibrary Loan

The power of APA PsycInfo Subject Searching

To focus your searches using APA PsycInfo try the following commands:

Also consider using the NOT command which eliminates all results with the word that follows it.

e.g., the search "social media" AND Meta NOT "meta-analysis"

... returns results that contain both the phrase " social media " and Meta , but not the phrase " meta-analysis " The " N " command (proximity) only returns results where search terms appear within a specified number of words from each other:

e.g., the search: "social media" N4 algorithm ... returns results where the phrase social media is within four words of the word algorithm .

=== === === === === === ===

A powerful technique to use in APA PsycInfo is " subject " searching. If you perform a keyword search on "disabilities" and "reading". This search returns over 8,000 results - many not particularly focused on either "disabilities" or "reading".

However, if you look at the " Subjects " listing under search results that look promising you will find specific subject terms that are linked with that article e.g., Learning Disabilities, Reading, Reading Achievement, Reading Comprehension, Reading Development, Reading Disabilities, Reading Skills, Reading Speed, etc.

Each "Subject" heading such as Reading Disabilities indicates that an article is particularly focused on that concept - making subject searching much more powerful than keyword search (or Google Scholar searching).

So start with a keyword search in APA PsycInfo ... then identify some potentially useful subject terms ... and then repeat the PsycInfo search limiting to the subject heading by changing the dropdown menu to SU Subjects

Other Options

You might also try limiting your search terms to either AB Abstract or TI Title ... especially if there are no obvious or effective subject headings to choose from.

Before you search - you may wish to limit your search to “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals.”

To limit to “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” be sure to check the box labeled “Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals” farther down the search screen:

Finding Empirical or Experimental Research using APA PsycInfo

You can use APA PsycInfo to search specifically for empirical research - articles that report an actual experiment or study. To find research articles t ype in your search and then - using the " Methodology " option at the bottom of the search page - limit your search to the option " EMPIRICAL STUDY "

Limiting to More Specific Types of Empirical Research.

You can also use the Finding Empirical or Experimental Research using APA PsycInfo search option to focus on more specific types of research such as a Qualitative Study or Quantitative Study.

- Next: Google Scholar >>

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 7:11 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uni.edu/research-methods-in-psychology

- Decrease Font Size

- Increase Font Size

- Study At Adelaide

- Course Outlines

- PSYCHOL 1004

- Log-in

PSYCHOL 1004 - Research Methods in Psychology

North terrace campus - semester 1 - 2021, course details, course staff.

Course Coordinator: Professor Peter Strelan

Course Timetable

The full timetable of all activities for this course can be accessed from Course Planner .

Course Learning Outcomes

University graduate attributes.

This course will provide students with an opportunity to develop the Graduate Attribute(s) specified below:

Recommended Resources

Online learning, learning & teaching modes.

The information below is provided as a guide to assist students in engaging appropriately with the course requirements.

Learning Activities Summary

Small group discovery experience, assessment summary, assessment detail, course grading.

Grades for your performance in this course will be awarded in accordance with the following scheme:

Further details of the grades/results can be obtained from Examinations .

Grade Descriptors are available which provide a general guide to the standard of work that is expected at each grade level. More information at Assessment for Coursework Programs .

Final results for this course will be made available through Access Adelaide .

The University places a high priority on approaches to learning and teaching that enhance the student experience. Feedback is sought from students in a variety of ways including on-going engagement with staff, the use of online discussion boards and the use of Student Experience of Learning and Teaching (SELT) surveys as well as GOS surveys and Program reviews.

SELTs are an important source of information to inform individual teaching practice, decisions about teaching duties, and course and program curriculum design. They enable the University to assess how effectively its learning environments and teaching practices facilitate student engagement and learning outcomes. Under the current SELT Policy (http://www.adelaide.edu.au/policies/101/) course SELTs are mandated and must be conducted at the conclusion of each term/semester/trimester for every course offering. Feedback on issues raised through course SELT surveys is made available to enrolled students through various resources (e.g. MyUni). In addition aggregated course SELT data is available.

- Academic Integrity for Students

- Academic Support with Maths

- Academic Support with writing and study skills

- Careers Services

- International Student Support

- Library Services for Students

- LinkedIn Learning

- Student Life Counselling Support - Personal counselling for issues affecting study

- Students with a Disability - Alternative academic arrangements

- YouX Student Care - Advocacy, confidential counselling, welfare support and advice

This section contains links to relevant assessment-related policies and guidelines - all university policies .

- Academic Credit Arrangements Policy

- Academic Integrity Policy

- Academic Progress by Coursework Students Policy

- Assessment for Coursework Programs Policy

- Copyright Compliance Policy

- Coursework Academic Programs Policy

- Elder Conservatorium of Music Noise Management Plan

- Intellectual Property Policy

- IT Acceptable Use and Security Policy

- Modified Arrangements for Coursework Assessment Policy

- Reasonable Adjustments to Learning, Teaching & Assessment for Students with a Disability Policy

- Student Experience of Learning and Teaching Policy

- Student Grievance Resolution Process

Students are reminded that in order to maintain the academic integrity of all programs and courses, the university has a zero-tolerance approach to students offering money or significant value goods or services to any staff member who is involved in their teaching or assessment. Students offering lecturers or tutors or professional staff anything more than a small token of appreciation is totally unacceptable, in any circumstances. Staff members are obliged to report all such incidents to their supervisor/manager, who will refer them for action under the university's student’s disciplinary procedures.

The University of Adelaide is committed to regular reviews of the courses and programs it offers to students. The University of Adelaide therefore reserves the right to discontinue or vary programs and courses without notice. Please read the important information contained in the disclaimer .

- Copyright & Disclaimer

- Privacy Statement

- Freedom of Information

Information For

- Future Students

- International Students

- New Students

- Current Students

- Current Staff

- Future Staff

- Industry & Government

Information About

- The University

- Study at Adelaide

- Degrees & Courses

- Work at Adelaide

- Research at Adelaide

- Indigenous Education

- Learning & Teaching

- Giving to Adelaide

People & Places

- Faculties & Divisions

- Campuses & Maps

- Staff Directory

The University of Adelaide Adelaide , South Australia 5005 Australia Australian University Provider Number PRV12105 CRICOS Provider Number 00123M

Telephone: +61 8 8313 4455

Coordinates: -34.920843 , 138.604513

Study Online

Graduate Diploma in Psychology Online

1.7 years part-time

Eligible for Fee-HELP. Learn more

Course Overview

Our 100% online Graduate Diploma in Psychology is your first step in a rewarding career of connecting with others. The program and curriculum are accredited by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC) and covers all the foundational knowledge you need to start your journey towards becoming a registered psychologist.

Our smaller, intimate class sizes ensure you’re able to forge those one-on-one connections and get the most out of your study program and you'll be supported every step of the way by our dedicated and highly qualified staff. Start an application today and join South Australia's #1 university for graduate employability (QS, 2022).

Why study psychology with us?

100% online

Study around your commitments and access content and assessments 24/7.

Engaging content

Discover what makes people tick through short instructional videos, readings and interactive activities.

Research excellence

We were ‘above world standard’ in the 2018 Australian Research Council (ARC) Excellence in Research Australia report.

Trusted support

Our dedicated Student Success Advisors and PhD-qualified tutors provide one-on-one support.

Stay connected

Our smaller, intimate class sizes ensure that you’ll get the most out of your online psychology program.

Study pathway

Complete our Graduate Diploma in Psychology then seamlessly transition into our honours-equivalent program .

Accreditations and ranking

Make your mark amidst a rich history of excellence spanning more than 140 years.

Our online Graduate Diploma in Psychology is accredited by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC).

Group of Eight

Studying at one of Australia’s leading research-intensive universities guarantees an exceptional quality of learning and global recognition.

Global top 1%

We're in the top 1% of universities worldwide (Times Higher Education, 2023).

Flexible online learning

Studying psychology online allows you the flexibility to understand how the human brain works in your own time.

How long is each psychology subject?

What should I expect from the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology?

The ten online Graduate Diploma in Psychology courses cover the foundational knowledge you need to start your journey towards becoming a registered psychologist.

- weekly interactive webinar tutorials to ask questions and deepen your psychology knowledge

- weekend drop-in sessions with your tutors

- discussion forums with your peers and tutors

- course readings and guided psychology research

- three assessments over the six weeks.

The University of Adelaide has partnered with Pearson, the world’s leading global learning company, to deliver this degree 100% online. The Partnership has been established to deliver the very best experience and learning outcomes to all our students. Students will be awarded a University of Adelaide qualification and this degree meets the University's highest quality standards.

Request a brochure

What skills will I gain?

Upon successful completion of the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology, graduates will be able to:

- synthesise and critique psychological theory and contemporary knowledge

- apply psychological concepts to complex personal, social and societal issues

- formulate psychology research questions and design psychological research studies

- apply qualitative, quantitative and mixed methodology techniques to analyse psychological data

- produce reports and other materials in formats suitable for a variety of audiences and purposes

- reflect critically on the ethical issues, legislative requirements and evidence-based approaches underpinning psychological research and select areas of professional practice.

What our psychology students say

"All my tutors have been fantastic. They're always there to help if I need and check in regularly."

- Madison O'Brien, current online Graduate Diploma in Psychology student

What will my psychology assignments be?

Assessments will be real-world type assessments and will include but not limited to:

- small weekly psychology quizzes

- annotated bibliography

- literature review

- creative exercises

- group tasks

- reflective exercises

Download a Graduate Diploma in Psychology brochure to learn more about the online learning experience.

Contact us now

Get your questions answered

Hours: Monday – Thursday, 8.30am to 5pm (ACST/ACDT), Friday, 8.30am to 4.30pm (ACST/ACDT).

We can help you with:

- entry requirements

- curriculum

- key dates & intakes

- your unique situation

Psychology career paths and opportunities

- Registered psychologist

- People-centric roles

- Research and academia

Working as a registered psychologist is a deeply fulfilling and rewarding experience. There are many ways and settings in which you can help people and make a positive impact. From schools to hospitals, community organisations and research institutions; psychologists make invaluable contributions to individuals and societies across the globe.

The broad range of skills you will gain from the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology are also essential for many roles in health, business, sport and community organisations. Whether you want to shift your career trajectory, boost your current job, or brush up on your education – your new critical thinking and people-orientated skills will empower you to answer your calling.

For students who wish to become a researcher or academic, successful completion of the psychology study pathway will also help you meet the entry requirements for psychology PhD or a doctorate. People working in academic psychology deepen our understanding of human behaviour and cognition by conducting scientific and scholarly research or educating the next generation of psychologists.

- Fee information

- Entry Requirements

How to become a psychologist?

Before you can become a practicing or “registered psychologist”, you need to complete a sequence of both study and training psychology. This sequence is divided up into three steps. If you have a Bachelor’s degree but not in psychology, our Graduate Diploma in Psychology (GDP) is your first step.

Once you successfully complete our graduate diploma, you are then eligible to continue onto step two, which is a ‘4th-year’ psychology program. The University of Adelaide offers an online Graduate Diploma in Psychology (Advanced) (GDPA) which is a 4th-year equivalent psychology program, just like an on-campus honours program.

The final step is to complete one of the University of Adelaide's masters level study options below plus supervised practice before you can apply for general registration.

- Master of Psychology (Clinical)

- Master of Psychology (Health)

- Master of Psychology (Organisational and Human Factors)

What level of experience do the Graduate Diploma in Psychology program tutors have?

Our tutors have a wealth of academic and industry psychology experience and are well established in their fields with a minimum AQF Level of 9+.

Is the Graduate Diploma in Psychology online program APAC-accredited?

Yes. Earning an accreditation from the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC) means that the Graduate Diploma in Psychology has been formally and comprehensively examined and it meets the predetermined standards of education for psychologists. APAC also ensure the program formally provides the required sequence of subjects for students wishing to undertake further study in psychology and ongoing improvement of educational quality in psychology.

What are the entry requirements for the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology?

In order to apply for an online Graduate Diploma in Psychology, the applicant must have completed an undergraduate Bachelor's degree (of any discipline) with a passing grade, so long as it meets Aus Qual criteria .

What is the difference between a psychologist and a counsellor?

There is a big difference between a psychologist and a counsellor. Professional psychologists provide clinical mental health support, helping patients suffering from complex long-term mental health conditions, whereas counsellors usually help patients with specific short-term challenges. Psychologists must complete a specific educational criteria only becoming a registered psychologist once they have achieved the correct training. A counsellor does not require as much training but cannot provide medical advice.

Foundations of psychology - PSYCHOL 6500OL

This psychology course introduces foundational concepts and topics within the contemporary psychological field. You will learn about psychology research, theories, concepts and applications of psychological science in diverse topics such as:

- child development

- mental health

- personality and ability

- biological bases of behaviour

- memory and cognition

- motivation and emotion

These areas of study will provide a strong foundation for your future studies in psychology.

View the psychology course outline .

Learning and behaviour - PSYCHOL 6509OL

How do we learn from the environment around us? Study psychology and explore the theoretical foundations of learning and how they are supported by research while examining how this knowledge is applied to human and animal behaviour.

Research methods, design and analysis - PSYCHOL 6501OL

How do we make well-founded discoveries about the mind and behaviour? This online psychology course will uncover key techniques and tools used for research in psychology. Psychology students will develop the skills needed to critically evaluate and conduct psychology research into why people think and act the way they do.

View the Graduate Diploma in Psychology course outline .

Developmental psychology - PSYCHOL 6502OL

What is human development and does it ever stop? In what ways do people change and stay the same as they get older? This online psychology course will provide you with a multidimensional understanding of ageing and human development. You will be asked to consider established and emerging theories, along with contemporary research and applications in both child and adult development.

Psychological health and well-being - PSYCHOL 6503OL

What does it mean to be healthy? This online psychology course is structured as an introduction to evidence-based assessment, treatment and prevention. You will form a holistic view of behaviours and experiences from a biopsychosocial perspective to identify how psychological health can be enhanced or compromised. This online psychology course also covers select topics in clinical and health psychology.

View course outline .

Applying research methods in psychology - PSYCHOL 6504OL

How do we apply methodological and statistical concepts to real-world problems? This online psychology course builds on the foundation of research methods provided in PSYCHOL 6501OL. This psychology course will teach you to think critically about the process of conducting research, apply your knowledge of research methods to a variety of contexts, and further develop your understanding of common analyses.

Culture and context - PSYCHOL 6505OL

How much are you a product of your environment? In this online psychology course you will learn about the influence of cultural assumptions and values. The importance of understanding these issues in the context of working with indigenous people will be emphasised. You will also be provided with an understanding of how psychology can be used to improve work-related practices, job satisfaction and performance.

Social psychology - PSYCHOL 6506OL

Do you ever wonder why we behave differently in groups than when we’re on our own? This online psychology course will explore topics central to contemporary research in social psychology.

Cognitive Psychology - PSYCHOL 6507OL

Cognitive Psychology is the branch of Psychology focusing on how mental processes work. These mental processes include perception, attention, memory, language, and problem solving. In this course, students will be introduced to the research, theories, and debates within Cognitive Psychology regarding how these mental processes function, as well as the applications that research within the field have to everyday life and society.

Individual difference and assessment – PSYCHOL 6508OL

Are we all different or more similar than we think? Learn how and why people behave differently despite the broad similarities shared by all humankind. You will review major theories, research methods and findings and learn how these translate into practices in the fields of intelligence, personality, and psychological assessment.

What is the total cost?

$40,230* or $4,023 per course (2024 fees).

Find more information on fees for domestic students, including annual fees and fee increases, in the Fees (domestic students) section .

Is there FEE-HELP available?

Yes, Australian citizens are eligible for a HELP loan. You must also be enrolled in a program with the University of Adelaide by the enrolment deadline (census), and have not reached the HELP loan limit.

Once you have been offered a place in the University of Adelaide program, you will be able to apply for a HELP loan as a part of the enrolment process. Please see our FAQs section for further details.

Academic entry requirements

To be eligible for the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology, you will need an undergraduate Bachelor's degree (or equivalent) in any discipline.

English language requirements

In order to meet the English language proficiency requirements for our 100% online postgraduate programs , you must be able to demonstrate that you meet the minimum English Language requirements .

Typically, if English is your first language you will not be required to provide evidence of English language proficiency. You will also not be required to provide evidence of English language proficiency if you are an Australian citizen, Australian Permanent Resident (visa status) or hold a passport from one of the following countries: Canada (English-speaking provinces only), New Zealand, the Republic of Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

To learn more, visit the English Language Proficiency Requirements for detailed information about these requirements, including acceptable English language tests.

We also recommend that you speak to an Enrolment Advisor to discuss options that are specific to your circumstances. You can schedule a call here .

When can I start the Graduate Diploma in Psychology online?

There are six intakes into the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology degree throughout the year: January, March, May, July, August and October. Applications typically close four weeks before the online teaching period commences. See the important dates section for further details on studying psychology online.

Get in touch

Our Expert Advisors are available

Download a brochure now

Request a Graduate Diploma in Psychology brochure to learn more about:

- psychology study pathway

- Graduate Diploma in Psychology academic staff

- learning and psychology career outcomes

- complimentary support services

- application process

- psychology research project online

- assessments and more.

Create an account to start your application

Applying for the online Graduate Diploma in Psychology is a quick and easy process. Find out if your application was successful in as soon as 2-5 days.

Want to better understand the application process?

Book a 1:1 call now with our enrolment advisors and we can walk you through the application process — from how to meet the entry requirements through to enrolling in your first subject.

Read more on our blog

How to Become a Psychologist

Considering a career in psychology? There are many study pathways to choose from. Find out how to become a psychologist with the University of Adelaide.

Your guide to sport and performance psychology

Learn how to become a sport psychologist and how they help athletes reach their potential. Read all about sport psychology here.

Discover an online alternative to an honours in psychology

Take the next step towards becoming a registered psychologist & learn about studying an online honours-equivalent in psychology with the University of Adelaide.

The Key Concepts in Social Psychology

Discover the key concepts of social psychology to understand the influences behind human behaviour.

Study at Adelaide

Online Admissions

Student success, additional links.

This website uses cookies to give you the best, most relevant experience. Using this website means you agree to the use of cookies. You can change which cookies are set at anytime using your browser settings.

- Adelaide Research & Scholarship

- Honours and Coursework

- School of Psychology

Items in DSpace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2024

Procrastination, depression and anxiety symptoms in university students: a three-wave longitudinal study on the mediating role of perceived stress

- Anna Jochmann 1 ,

- Burkhard Gusy 1 ,

- Tino Lesener 1 &

- Christine Wolter 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 276 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

It is generally assumed that procrastination leads to negative consequences. However, evidence for negative consequences of procrastination is still limited and it is also unclear by which mechanisms they are mediated. Therefore, the aim of our study was to examine the harmful consequences of procrastination on students’ stress and mental health. We selected the procrastination-health model as our theoretical foundation and tried to evaluate the model’s assumption that trait procrastination leads to (chronic) disease via (chronic) stress in a temporal perspective. We chose depression and anxiety symptoms as indicators for (chronic) disease and hypothesized that procrastination leads to perceived stress over time, that perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time, and that procrastination leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time, mediated by perceived stress.

To examine these relationships properly, we collected longitudinal data from 392 university students at three occasions over a one-year period and analyzed the data using autoregressive time-lagged panel models.

Procrastination did lead to depression and anxiety symptoms over time. However, perceived stress was not a mediator of this effect. Procrastination did not lead to perceived stress over time, nor did perceived stress lead to depression and anxiety symptoms over time.

Conclusions

We could not confirm that trait procrastination leads to (chronic) disease via (chronic) stress, as assumed in the procrastination-health model. Nonetheless, our study demonstrated that procrastination can have a detrimental effect on mental health. Further health outcomes and possible mediators should be explored in future studies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

“Due tomorrow? Do tomorrow.”, might be said by someone who has a tendency to postpone tasks until the last minute. But can we enjoy today knowing about the unfinished task and tomorrow’s deadline? Or do we feel guilty for postponing a task yet again? Do we get stressed out because we have little time left to complete it? Almost everyone has procrastinated at some point when it came to completing unpleasant tasks, such as mowing the lawn, doing the taxes, or preparing for exams. Some tend to procrastinate more frequently and in all areas of life, while others are less inclined to do so. Procrastination is common across a wide range of nationalities, as well as socioeconomic and educational backgrounds [ 1 ]. Over the last fifteen years, there has been a massive increase in research on procrastination [ 2 ]. Oftentimes, research focuses on better understanding the phenomenon of procrastination and finding out why someone procrastinates in order to be able to intervene. Similarly, the internet is filled with self-help guides that promise a way to overcome procrastination. But why do people seek help for their procrastination? Until now, not much research has been conducted on the negative consequences procrastination could have on health and well-being. Therefore, in the following article we examine the effect of procrastination on mental health over time and stress as a possible facilitator of this relationship on the basis of the procrastination-health model by Sirois et al. [ 3 ].

Procrastination and its negative consequences

Procrastination can be defined as the tendency to voluntarily and irrationally delay intended activities despite expecting negative consequences as a result of the delay [ 4 , 5 ]. It has been observed in a variety of groups across the lifespan, such as students, teachers, and workers [ 1 ]. For example, some students tend to regularly delay preparing for exams and writing essays until the last minute, even if this results in time pressure or lower grades. Procrastination must be distinguished from strategic delay [ 4 , 6 ]. Delaying a task is considered strategic when other tasks are more important or when more resources are needed before the task can be completed. While strategic delay is viewed as functional and adaptive, procrastination is classified as dysfunctional. Procrastination is predominantly viewed as the result of a self-regulatory failure [ 7 ]. It can be understood as a trait, that is, as a cross-situational and time-stable behavioral disposition [ 8 ]. Thus, it is assumed that procrastinators chronically delay tasks that they experience as unpleasant or difficult [ 9 ]. Approximately 20 to 30% of adults have been found to procrastinate chronically [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Prevalence estimates for students are similar [ 13 ]. It is believed that students do not procrastinate more often than other groups. However, it is easy to examine procrastination in students because working on study tasks requires a high degree of self-organization and time management [ 14 ].

It is generally assumed that procrastination leads to negative consequences [ 4 ]. Negative consequences are even part of the definition of procrastination. Research indicates that procrastination is linked to lower academic performance [ 15 ], health impairment (e.g., stress [ 16 ], physical symptoms [ 17 ], depression and anxiety symptoms [ 18 ]), and poor health-related behavior (e.g., heavier alcohol consumption [ 19 ]). However, most studies targeting consequences of procrastination are cross-sectional [ 4 ]. For that reason, it often remains unclear whether an examined outcome is a consequence or an antecedent of procrastination, or whether a reciprocal relationship between procrastination and the examined outcome can be assumed. Additionally, regarding negative consequences of procrastination on health, it is still largely unknown by which mechanisms they are mediated. Uncovering such mediators would be helpful in developing interventions that can prevent negative health consequences of procrastination.

The procrastination-health model

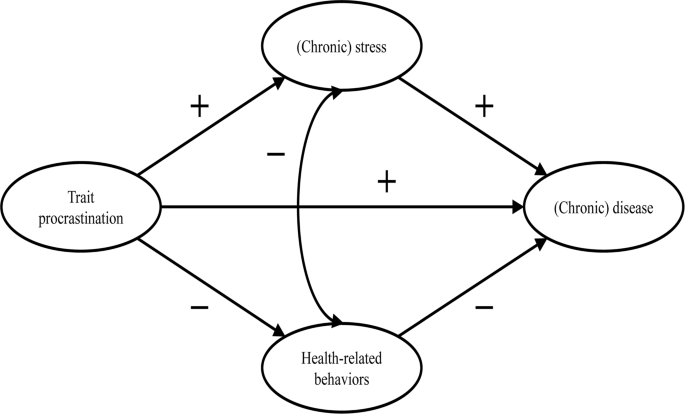

The first and only model that exclusively focuses on the effect of procrastination on health and the mediators of this effect is the procrastination-health model [ 3 , 9 , 17 ]. Sirois [ 9 ] postulates three pathways: An immediate effect of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease and two mediated pathways (see Fig. 1 ).

Adopted from the procrastination-health model by Sirois [ 9 ]

The immediate effect is not further explained. Research suggests that procrastination creates negative feelings, such as shame, guilt, regret, and anger [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. The described feelings could have a detrimental effect on mental health [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

The first mediated pathway leads from trait procrastination to (chronic) disease via (chronic) stress. Sirois [ 9 ] assumes that procrastination creates stress because procrastinators are constantly aware of the fact that they still have many tasks to complete. Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system, increases autonomic nervous system arousal, and weakens the immune system, which in turn contributes to the development of diseases. Sirois [ 9 ] distinguishes between short-term and long-term effects of procrastination on health mediated by stress. She believes that, in the short term, single incidents of procrastination cause acute stress, which leads to acute health problems, such as infections or headaches. In the long term, chronic procrastination, as you would expect with trait procrastination, causes chronic stress, which leads to chronic diseases over time. There is some evidence in support of the stress-related pathway, particularly regarding short-term effects [ 3 , 17 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. However, as we mentioned above, most of these studies are cross-sectional. Therefore, the causal direction of these effects remains unclear. To our knowledge, long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by (chronic) stress have not yet been investigated.

The second mediated pathway leads from trait procrastination to (chronic) disease via poor health-related behavior. According to Sirois [ 9 ], procrastinators form lower intentions to carry out health-promoting behavior or to refrain from health-damaging behavior because they have a low self-efficacy of being able to care for their own health. In addition, they lack the far-sighted view that the effects of health-related behavior only become apparent in the long term. For the same reason, Sirois [ 9 ] believes that there are no short-term, but only long-term effects of procrastination on health mediated by poor health-related behavior. For example, an unhealthy diet leads to diabetes over time. The findings of studies examining the behavioral pathway are inconclusive [ 3 , 17 , 26 , 28 ]. Furthermore, since most of these studies are cross-sectional, they are not suitable for uncovering long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by poor health-related behavior.

In summary, previous research on the two mediated pathways of the procrastination-health model mainly found support for the role of (chronic) stress in the relationship between trait procrastination and (chronic) disease. However, only short-term effects have been investigated so far. Moreover, longitudinal studies are needed to be able to assess the causal direction of the relationship between trait procrastination, (chronic) stress, and (chronic) disease. Consequently, our study is the first to examine long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by (chronic) stress, using a longitudinal design. (Chronic) disease could be measured by a variety of different indicators (e.g., physical symptoms, diabetes, or coronary heart disease). We choose depression and anxiety symptoms as indicators for (chronic) disease because they signal mental health complaints before they manifest as (chronic) diseases. Additionally, depression and anxiety symptoms are two of the most common mental health complaints among students [ 29 , 30 ] and procrastination has been shown to be a significant predictor of depression and anxiety symptoms [ 18 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Until now, the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model with depression and anxiety symptoms as the health outcome has only been analyzed in one cross-sectional study that confirmed the predictions of the model [ 35 ].

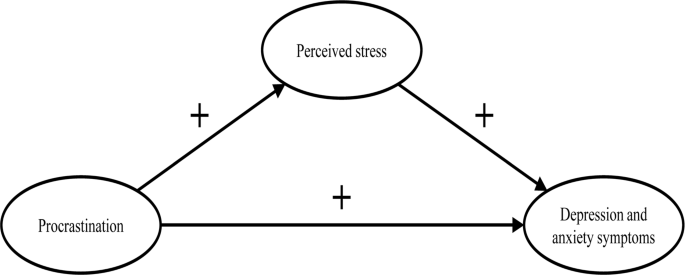

The aim of our study is to evaluate some of the key assumptions of the procrastination-health model, particularly the relationships between trait procrastination, (chronic) stress, and (chronic) disease over time, surveyed in the following analysis using depression and anxiety symptoms.

In line with the key assumptions of the procrastination-health model, we postulate (see Fig. 2 ):

Procrastination leads to perceived stress over time.

Perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time.

Procrastination leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time, mediated by perceived stress.

The section of the procrastination-health model we examined

Materials and methods

Our study was part of a health monitoring at a large German university Footnote 1 . Ethical approval for our study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the university’s Department of Education and Psychology. We collected the initial data in 2019. Two occasions followed, each at an interval of six months. In January 2019, we sent out 33,267 invitations to student e-mail addresses. Before beginning the survey, students provided their written informed consent to participate in our study. 3,420 students took part at the first occasion (T1; 10% response rate). Of these, 862 participated at the second (T2) and 392 at the third occasion (T3). In order to test whether dropout was selective, we compared sociodemographic and study specific characteristics (age, gender, academic semester, number of assessments/exams) as well as behavior and health-related variables (procrastination, perceived stress, depression and anxiety symptoms) between the participants of the first wave ( n = 3,420) and those who participated three times ( n = 392). Results from independent-samples t-tests and chi-square analysis showed no significant differences regarding sociodemographic and study specific characteristics (see Additional file 1: Table S1 and S2 ). Regarding behavior and health-related variables, independent-samples t-tests revealed a significant difference in procrastination between the two groups ( t (3,409) = 2.08, p < .05). The mean score of procrastination was lower in the group that participated in all three waves.

The mean age of the longitudinal respondents was 24.1 years ( SD = 5.5 years), the youngest participants were 17 years old, the oldest one was 59 years old. The majority of participants was female (74.0%), 7 participants identified neither as male nor as female (1.8%). The respondents were on average enrolled in the third year of studying ( M = 3.9; SD = 2.3). On average, the students worked about 31.2 h ( SD = 14.1) per week for their studies, and an additional 8.5 h ( SD = 8.5) for their (part-time) jobs. The average income was €851 ( SD = 406), and 4.9% of the students had at least one child. The students were mostly enrolled in philosophy and humanities (16.5%), education and psychology (15.8%), biology, chemistry, and pharmacy (12.5%), political and social sciences (10.6%), veterinary medicine (8.9%), and mathematics and computer science (7.7%).

We only used established and well evaluated instruments for our analyses.

- Procrastination

We adopted the short form of the Procrastination Questionnaire for Students (PFS-4) [ 36 ] to measure procrastination. The PFS-4 assesses procrastination at university as a largely stable behavioral disposition across situations, that is, as a trait. The questionnaire consists of four items (e.g., I put off starting tasks until the last moment.). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale ((almost) never = 1 to (almost) always = 5) for the last two weeks. All items were averaged, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency to procrastinate. The PFS-4 has been proven to be reliable and valid, showing very high correlations with other established trait procrastination scales, for example, with the German short form of the General Procrastination Scale [ 37 , 38 ]. We also proved the scale to be one-dimensional in a factor analysis, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Perceived stress

The Heidelberger Stress Index (HEI-STRESS) [ 39 ] is a three-item measure of current perceived stress due to studying as well as in life in general. For the first item, respondents enter a number between 0 (not stressed at all) and 100 (completely stressed) to indicate how stressed their studies have made them feel over the last four weeks. For the second and third item, respondents rate on a 5-point scale how often they feel “stressed and tense” and as how stressful they would describe their life at the moment. We transformed the second and third item to match the range of the first item before we averaged all items into a single score with higher values indicating greater perceived stress. We proved the scale to be one-dimensional and Cronbach’s alpha for our study was 0.86.

Depression and anxiety symptoms

We used the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) [ 40 ], a short form of the Patient Health Questionnaire [ 41 ] with four items, to measure depression and anxiety symptoms. The PHQ-4 contains two items from the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) [ 42 ] and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-2 (GAD-2) [ 43 ], respectively. It is a well-established screening scale designed to assess the core criteria of major depressive disorder (PHQ-2) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD-2) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). However, it was shown that the GAD-2 is also appropriate for screening other anxiety disorders. According to Kroenke et al. [ 40 ], the PHQ-4 can be used to assess a person’s symptom burden and impairment. We asked the participants to rate how often they have been bothered over the last two weeks by problems, such as “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”. Response options were 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = nearly every day. Calculated as the sum of the four items, the total scores range from 0 to 12 with higher scores indicating more frequent depression and anxiety symptoms. The total scores can be categorized as none-to-minimal (0–2), mild (3–5), moderate (6–8), and severe (9–12) depression and anxiety symptoms. The PHQ-4 was shown to be reliable and valid [ 40 , 44 , 45 ]. We also proved the scale to be one-dimensional in a factor analysis, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86.

Data analysis

To test our hypotheses, we performed structural equation modelling (SEM) using R (Version 4.1.1) with the package lavaan. All items were standardized ( M = 0, SD = 1). Due to the non-normality of some study variables and a sufficiently large sample size of N near to 400 [ 46 ], we used robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) for all model estimations. As recommended by Hu and Bentler [ 47 ], we assessed the models’ goodness of fit by chi-square test statistic, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI). A non-significant chi-square indicates good model fit. Since chi-square is sensitive to sample size, we also evaluated fit indices less sensitive to the number of observations. RMSEA and SRMR values of 0.05 or lower as well as TLI and CFI values of 0.97 or higher indicate good model fit. RMSEA values of 0.08 or lower, SRMR values of 0.10 or lower, as well as TLI and CFI values of 0.95 or higher indicate acceptable model fit [ 48 , 49 ]. First, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis for the first occasion, defining three factors that correspond to the measures of procrastination, perceived stress, and depression and anxiety symptoms. Next, we tested for measurements invariance over time and specified the measurement model, before testing our hypotheses.

Measurement invariance over time

To test for measurement invariance over time, we defined one latent variable for each of the three occasions, corresponding to the measures of procrastination, perceived stress, and depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively. As recommended by Geiser and colleagues [ 50 ], the links between indicators and factors (i.e., factor loadings and intercepts) should be equal over measurement occasions; therefore, we added indicator specific factors. A first and least stringent step of testing measurement invariance is configural invariance (M CI ). It was examined whether the included constructs (procrastination, perceived stress, depression and anxiety symptoms) have the same pattern of free and fixed loadings over time. This means that the assignment of the indicators to the three latent factors over time is supported by the underlying data. If configural invariance was supported, restrictions for the next step of testing measurement invariance (metric or weak invariance; M MI ) were added. This means that each item contributes to the latent construct to a similar degree over time. Metric invariance was tested by constraining the factor loadings of the constructs over time. The next step of testing measurement invariance (scalar or strong invariance; M SI ) consisted of checking whether mean differences in the latent construct capture all mean differences in the shared variance of the items. Scalar invariance was tested by constraining the item intercepts over time. The constraints applied in the metric invariance model were retained [ 51 ]. For the last step of testing measurement invariance (residual or strict invariance; M RI ), the residual variables were also set equal over time. If residual invariance is supported, differences in the observed variables can exclusively be attributed to differences in the variances of the latent variables.

We used the Satorra-Bentler chi-square difference test to evaluate the superiority of a more stringent model [ 52 ]. We assumed the model with the largest number of invariance restrictions – which still has an acceptable fit and no substantial deterioration of the chi-square value – to be the final model [ 53 ]. Following previous recommendations, we considered a decrease in CFI of 0.01 and an increase in RMSEA of 0.015 as unacceptable to establish measurement invariance [ 54 ]. If a more stringent model had a significant worse chi-square value, but the model fit was still acceptable and the deterioration in model fit fell within the change criteria recommended for CFI and RMSEA values, we still considered the more stringent model to be superior.

Hypotheses testing

As recommended by Dormann et al. [ 55 ], we applied autoregressive time-lagged panel models to test our hypotheses. In the first step, we specified a model (M 0 ) that only included the stabilities of the three variables (procrastination, perceived stress, depression and anxiety symptoms) over time. In the next step (M 1 ), we added the time-lagged effects from procrastination (T1) to perceived stress (T2) and from procrastination (T2) to perceived stress (T3) as well as from perceived stress (T1) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T2) and from perceived stress (T2) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T3). Additionally, we included a direct path from procrastination (T1) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T3). If this path becomes significant, we can assume a partial mediation [ 55 ]. Otherwise, we can assume a full mediation. We compared these nested models using the Satorra-Bentler chi-square difference test and the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The chi-square difference value should either be non-significant, indicating that the proposed model including our hypotheses (M 1 ) does not have a significant worse model fit than the model including only stabilities (M 0 ), or, if significant, it should be in the direction that M 1 fits the data better than M 0 . Regarding the AIC, M 1 should have a lower value than M 0 .

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha), and stabilities (correlations) of all study variables. The alpha values of procrastination, perceived stress, and depression and anxiety symptoms are classified as good (> 0.80) [ 56 ]. The correlation matrix of the manifest variables used for the analyses can be found in the Additional file 1: Table S3 .

We observed the highest test-retest reliabilities for procrastination ( r ≥ .74). The test-retest reliabilities for depression and anxiety symptoms ( r ≥ .64) and for perceived stress ( r ≥ .54) were a bit lower (see Table 1 ). The pattern of correlations shows a medium to large but positive relationship between procrastination and depression and anxiety symptoms [ 57 , 58 ]. The association between procrastination and perceived stress was small, the one between perceived stress and depression and anxiety symptoms very large (see Table 1 ).

Confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable to good fit (x 2 (41) = 118.618, p < .001; SRMR = 0.042; RMSEA = 0.071; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97). When testing for measurement invariance over time for each construct, the residual invariance models with indicator specific factors provided good fit to the data (M RI ; see Table 2 ), suggesting that differences in the observed variables can exclusively be attributed to differences of the latent variables. We then specified and tested the measurement model of the latent constructs prior to model testing based on the items of procrastination, perceived stress, and depression and anxiety symptoms. The measurement model fitted the data well (M M ; see Table 3 ). All items loaded solidly on their respective factors (0.791 ≤ β ≤ 0.987; p < .001).

To test our hypotheses, we analyzed the two models described in the methods section.

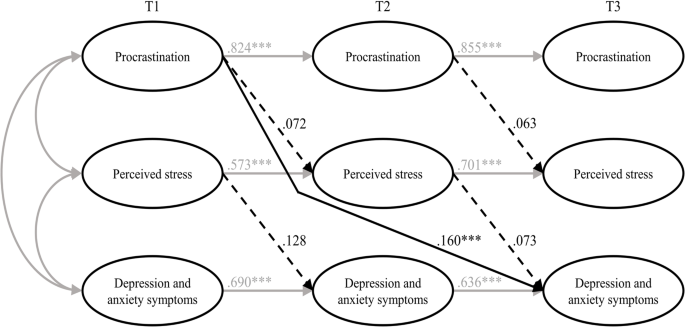

The fit of the stability model (M 0 ) was acceptable (see Table 3 ). Procrastination was stable over time, with stabilities above 0.82. The stabilities of perceived stress as well as depression and anxiety symptoms were somewhat lower, ranging from 0.559 (T1 -> T2) to 0.696 (T2 -> T3) for perceived stress and from 0.713 (T2 -> T3) to 0.770 (T1 -> T2) for depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively.

The autoregressive mediation model (M 1 ) fitted the data significantly better than M 0 . The direct path from procrastination (T1) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T3) was significant (β = 0.16; p < .001), however, none of the mediated paths (from procrastination (T1) to perceived stress (T2) and from perceived stress (T2) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T3)) proved to be substantial. Also, the time-lagged paths from perceived stress (T1) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T2) and from procrastination (T2) to perceived stress (T3) were not substantial either (see Fig. 3 ).

To examine whether the hypothesized effects would occur over a one-year period rather than a six-months period, we specified an additional model with paths from procrastination (T1) to perceived stress (T3) and from perceived stress (T1) to depression and anxiety symptoms (T3), also including the stabilities of the three constructs as in the stability model M 0 . The model showed an acceptable fit (χ 2 (486) = 831.281, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.048; SRMR = 0.091; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.95), but neither of the two paths were significant.

Therefore, our hypotheses, that procrastination leads to perceived stress over time (H1) and that perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time (H2) must be rejected. We could only partially confirm our third hypothesis, that procrastination leads to depression and anxiety over time, mediated by perceived stress (H3), since procrastination did lead to depression and anxiety symptoms over time. However, this effect was not mediated by perceived stress.

Results of the estimated model including all hypotheses (M 1 ). Note Non-significant paths are dotted. T1 = time 1; T2 = time 2; T3 = time 3. *** p < .001

To sum up, we tried to examine the harmful consequences of procrastination on students’ stress and mental health. Hence, we selected the procrastination-health model by Sirois [ 9 ] as a theoretical foundation and tried to evaluate some of its key assumptions in a temporal perspective. The author assumes that trait procrastination leads to (chronic) disease via (chronic) stress. We chose depression and anxiety symptoms as indicators for (chronic) disease and postulated, in line with the key assumptions of the procrastination-health model, that procrastination leads to perceived stress over time (H1), that perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time (H2), and that procrastination leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time, mediated by perceived stress (H3). To examine these relationships properly, we collected longitudinal data from students at three occasions over a one-year period and analyzed the data using autoregressive time-lagged panel models. Our first and second hypotheses had to be rejected: Procrastination did not lead to perceived stress over time, and perceived stress did not lead to depression and anxiety symptoms over time. However, procrastination did lead to depression and anxiety symptoms over time – which is in line with our third hypothesis – but perceived stress was not a mediator of this effect. Therefore, we could only partially confirm our third hypothesis.

Our results contradict previous studies on the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model, which consistently found support for the role of (chronic) stress in the relationship between trait procrastination and (chronic) disease. Since most of these studies were cross-sectional, though, the causal direction of these effects remained uncertain. There are two longitudinal studies that confirm the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model [ 27 , 28 ], but both studies examined short-term effects (≤ 3 months), whereas we focused on more long-term effects. Therefore, the divergent findings may indicate that there are short-term, but no long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by (chronic) stress.

Our results especially raise the question whether trait procrastination leads to (chronic) stress in the long term. Looking at previous longitudinal studies on the effect of procrastination on stress, the following stands out: At shorter study periods of two weeks [ 27 ] and four weeks [ 28 ], the effect of procrastination on stress appears to be present. At longer study periods of seven weeks [ 59 ], three months [ 28 ], six months, and twelve months, as in our study, the effect of procrastination on stress does not appear to be present. There is one longitudinal study in which procrastination was a significant predictor of stress symptoms nine months later [ 34 ]. The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, though, because the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic fell within the study period, which could have contributed to increased stress symptoms [ 60 ]. Unfortunately, Johansson et al. [ 34 ] did not report whether average stress symptoms increased during their study. In one of the two studies conducted by Fincham and May [ 59 ], the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak also fell within their seven-week study period. However, they reported that in their study, average stress symptoms did not increase from baseline to follow-up. Taken together, the findings suggest that procrastination can cause acute stress in the short term, for example during times when many tasks need to be completed, such as at the end of a semester, but that procrastination does not lead to chronic stress over time. It seems possible that students are able to recover during the semester from the stress their procrastination caused at the end of the previous semester. Because of their procrastination, they may also have more time to engage in relaxing activities, which could further mitigate the effect of procrastination on stress. Our conclusions are supported by an early and well-known longitudinal study by Tice and Baumeister [ 61 ], which compared procrastinating and non-procrastinating students with regard to their health. They found that procrastinators experienced less stress than their non-procrastinating peers at the beginning of the semester, but more at the end of the semester. Additionally, our conclusions are in line with an interview study in which university students were asked about the consequences of their procrastination [ 62 ]. The students reported that, due to their procrastination, they experience high levels of stress during periods with heavy workloads (e.g., before deadlines or exams). However, the stress does not last, instead, it is relieved immediately after these periods.

Even though research indicates, in line with the assumptions of the procrastination-health model, that stress is a risk factor for physical and mental disorders [ 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 ], perceived stress did not have a significant effect on depression and anxiety symptoms in our study. The relationship between stress and mental health is complex, as people respond to stress in many different ways. While some develop stress-related mental disorders, others experience mild psychological symptoms or no symptoms at all [ 67 ]. This can be explained with the help of vulnerability-stress models. According to vulnerability-stress models, mental illnesses emerge from an interaction of vulnerabilities (e.g., genetic factors, difficult family backgrounds, or weak coping abilities) and stress (e.g., minor or major life events or daily hassles) [ 68 , 69 ]. The stress perceived by the students in our sample may not be sufficient enough on its own, without the presence of other risk factors, to cause depression and anxiety symptoms. However, since we did not assess individual vulnerability and stress factors in our study, these considerations are mere speculation.

In our study, procrastination led to depression and anxiety symptoms over time, which is consistent with the procrastination-health model as well as previous cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence [ 18 , 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. However, it is still unclear by which mechanisms this effect is mediated, as perceived stress did not prove to be a substantial mediator in our study. One possible mechanism would be that procrastination impairs affective well-being [ 70 ] and creates negative feelings, such as shame, guilt, regret, and anger [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 62 , 71 ], which in turn could lead to depression and anxiety symptoms [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Other potential mediators of the relationship between procrastination and depression and anxiety symptoms emerge from the behavioral pathway of the procrastination-health model, suggesting that poor health-related behaviors mediate the effect of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease. Although evidence for this is still scarce, the results of one cross-sectional study, for example, indicate that poor sleep quality might mediate the effect of procrastination on depression and anxiety symptoms [ 35 ].

In summary, we found that procrastination leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time and that perceived stress is not a mediator of this effect. We could not show that procrastination leads to perceived stress over time, nor that perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time. For the most part, the relationships between procrastination, perceived stress, and depression and anxiety symptoms did not match the relationships between trait procrastination, (chronic) stress, and (chronic) disease as assumed in the procrastination-health model. Explanations for this could be that procrastination might only lead to perceived stress in the short term, for example, during preparations for end-of-semester exams, and that perceived stress may not be sufficient enough on its own, without the presence of other risk factors, to cause depression and anxiety symptoms. In conclusion, we could not confirm long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by (chronic) stress, as assumed for the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

In our study, we tried to draw causal conclusions about the harmful consequences of procrastination on students’ stress and mental health. However, since procrastination is a trait that cannot be manipulated experimentally, we have conducted an observational rather than an experimental study, which makes causal inferences more difficult. Nonetheless, a major strength of our study is that we used a longitudinal design with three waves. This made it possible to draw conclusions about the causal direction of the effects, as in hardly any other study targeting consequences of procrastination on health before [ 4 , 28 , 55 ]. Therefore, we strongly recommend using a similar longitudinal design in future studies on the procrastination-health model or on consequences of procrastination on health in general.

We chose a time lag of six months between each of the three measurement occasions to examine long-term effects of procrastination on depression and anxiety symptoms mediated by perceived stress. However, more than six months may be necessary for the hypothesized effects to occur [ 72 ]. The fact that the temporal stabilities of the examined constructs were moderate or high (0.559 ≤ β ≤ 0.854) [ 73 , 74 ] also suggests that the time lags may have been too short. The larger the time lag, the lower the temporal stabilities, as shown for depression and anxiety symptoms, for example [ 75 ]. High temporal stabilities make it more difficult to detect an effect that actually exists [ 76 ]. Nonetheless, Dormann and Griffin [ 77 ] recommend using shorter time lags of less than one year, even with high stabilities, because of other influential factors, such as unmeasured third variables. Therefore, our time lags of six months seem appropriate.

It should be discussed, though, whether it is possible to detect long-term effects of the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model within a total study period of one year. Sirois [ 9 ] distinguishes between short-term and long-term effects of procrastination on health mediated by stress, but does not address how long it might take for long-term effects to occur or when effects can be considered long-term instead of short-term. The fact that an effect of procrastination on stress is evident at shorter study periods of four weeks or less but in most cases not at longer study periods of seven weeks or more, as we mentioned earlier, could indicate that short-term effects occur within the time frame of one to three months, considering the entire stress-related pathway. Hence, it seems appropriate to assume that we have examined rather long-term effects, given our study period of six and twelve months. Nevertheless, it would be beneficial to use varying study periods in future studies, in order to be able to determine when effects can be considered long-term.

Concerning long-term effects of the stress-related pathway, Sirois [ 9 ] assumes that chronic procrastination causes chronic stress, which leads to chronic diseases over time. The term “chronic stress” refers to prolonged stress episodes associated with permanent tension. The instrument we used captures perceived stress over the last four weeks. Even though the perceived stress of the students in our sample was relatively stable (0.559 ≤ β ≤ 0.696), we do not know how much fluctuation occurred between each of the three occasions. However, there is some evidence suggesting that perceived stress is strongly associated with chronic stress [ 78 ]. Thus, it seems acceptable that we used perceived stress as an indicator for chronic stress in our study. For future studies, we still suggest the use of an instrument that can more accurately reflect chronic stress, for example, the Trier Inventory for Chronic Stress (TICS) [ 79 ].

It is also possible that the occasions were inconveniently chosen, as they all took place in a critical academic period near the end of the semester, just before the examination period began. We chose a similar period in the semester for each occasion for the sake of comparability. However, it is possible that, during this preparation periods, stress levels peaked and procrastinators procrastinated less because they had to catch up after delaying their work. This could have introduced bias to the data. Therefore, in future studies, investigation periods should be chosen that are closer to the beginning or in the middle of a semester.

Furthermore, Sirois [ 9 ] did not really explain her understanding of “chronic disease”. However, it seems clear that physical illnesses, such as diabetes or cardiovascular diseases, are meant. Depression and anxiety symptoms, which we chose as indicators for chronic disease, represent mental health complaints that do not have to be at the level of a major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder, in terms of their quantity, intensity, or duration [ 40 ]. But they can be viewed as precursors to a major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder. Therefore, given our study period of one year, it seems appropriate to use depression and anxiety symptoms as indicators for chronic disease. At longer study periods, we would expect these mental health complaints to manifest as mental disorders. Moreover, the procrastination-health model was originally designed to be applied to physical diseases [ 3 ]. Perhaps, the model assumptions are more applicable to physical diseases than to mental disorders. By applying parts of the model to mental health complaints, we have taken an important step towards finding out whether the model is applicable to mental disorders as well. Future studies should examine additional long-term health outcomes, both physical and psychological. This would help to determine whether trait procrastination has varying effects on different diseases over time. Furthermore, we suggest including individual vulnerability and stress factors in future studies in order to be able to analyze the effect of (chronic) stress on (chronic) diseases in a more differentiated way.

Regarding our sample, 3,420 students took part at the first occasion, but only 392 participated three times, which results in a dropout rate of 88.5%. At the second and third occasion, invitation e-mails were only sent to participants who had indicated at the previous occasion that they would be willing to participate in a repeat survey and provided their e-mail address. This is probably one of the main reasons for our high dropout rate. Other reasons could be that the students did not receive any incentives for participating in our study and that some may have graduated between the occasions. Selective dropout analysis revealed that the mean score of procrastination was lower in the group that participated in all three waves ( n = 392) compared to the group that participated in the first wave ( n = 3,420). One reason for this could be that those who have a higher tendency to procrastinate were more likely to procrastinate on filling out our survey at the second and third occasion. The findings of our dropout analysis should be kept in mind when interpreting our results, as lower levels of procrastination may have eliminated an effect on perceived stress or on depression and anxiety symptoms. Additionally, across all age groups in population-representative samples, the student age group reports having the best subjective health [ 80 ]. Therefore, it is possible that they are more resilient to stress and experience less impairment of well-being than other age groups. Hence, we recommend that future studies focus on other age groups as well.

It is generally assumed that procrastination leads to lower academic performance, health impairment, and poor health-related behavior. However, evidence for negative consequences of procrastination is still limited and it is also unclear by which mechanisms they are mediated. In consequence, the aim of our study was to examine the effect of procrastination on mental health over time and stress as a possible facilitator of this relationship. We selected the procrastination-health model as a theoretical foundation and used the stress-related pathway of the model, assuming that trait procrastination leads to (chronic) disease via (chronic) stress. We chose depression and anxiety symptoms as indicators for (chronic) disease and collected longitudinal data from students at three occasions over a one-year period. This allowed us to draw conclusions about the causal direction of the effects, as in hardly any other study examining consequences of procrastination on (mental) health before. Our results indicate that procrastination leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time and that perceived stress is not a mediator of this effect. We could not show that procrastination leads to perceived stress over time, nor that perceived stress leads to depression and anxiety symptoms over time. Explanations for this could be that procrastination might only lead to perceived stress in the short term, for example, during preparations for end-of-semester exams, and that perceived stress may not be sufficient on its own, that is, without the presence of other risk factors, to cause depression and anxiety symptoms. Overall, we could not confirm long-term effects of trait procrastination on (chronic) disease mediated by (chronic) stress, as assumed for the stress-related pathway of the procrastination-health model. Our study emphasizes the importance of identifying the consequences procrastination can have on health and well-being and determining by which mechanisms they are mediated. Only then will it be possible to develop interventions that can prevent negative health consequences of procrastination. Further health outcomes and possible mediators should be explored in future studies, using a similar longitudinal design.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

University Health Report at Freie Universität Berlin.

Abbreviations

Comparative fit index

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-2

Heidelberger Stress Index

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical

Robust maximum likelihood estimation

Short form of the Procrastination Questionnaire for Students

Patient Health Questionnaire-2

Patient Health Questionnaire-4

Root mean square error of approximation

Structural equation modeling

Standardized root mean square residual

Tucker-Lewis index

Lu D, He Y, Tan Y, Gender S, Status. Cultural differences, Education, family size and procrastination: a sociodemographic Meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.719425 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Yan B, Zhang X. What research has been conducted on Procrastination? Evidence from a systematical bibliometric analysis. Front Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809044 .

Sirois FM, Melia-Gordon ML, Pychyl TA. I’ll look after my health, later: an investigation of procrastination and health. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;35:1167–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00326-4 .

Article Google Scholar

Grunschel C. Akademische Prokrastination: Eine qualitative und quantitative Untersuchung von Gründen und Konsequenzen [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]: Universität Bielefeld; 2013.

Steel P. The Nature of Procrastination: a Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory failure. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Corkin DM, Yu SL, Lindt SF. Comparing active delay and procrastination from a self-regulated learning perspective. Learn Individ Differ. 2011;21:602–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.07.005 .

Balkis M, Duru E. Procrastination, self-regulation failure, academic life satisfaction, and affective well-being: underregulation or misregulation form. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2016;31:439–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0266-5 .

Schulz N. Procrastination und Planung – Eine Untersuchung zum Einfluss von Aufschiebeverhalten und Depressivität auf unterschiedliche Planungskompetenzen [Doctoral dissertation]: Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster; 2007.

Sirois FM. Procrastination, stress, and Chronic Health conditions: a temporal perspective. In: Sirois FM, Pychyl TA, editors. Procrastination, Health, and well-being. London: Academic; 2016. pp. 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802862-9.00004-9 .

Harriott J, Ferrari JR. Prevalence of procrastination among samples of adults. Psychol Rep. 1996;78:611–6. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1996.78.2.611 .

Ferrari JR, O’Callaghan J, Newbegin I. Prevalence of Procrastination in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia: Arousal and Avoidance delays among adults. N Am J Psychol. 2005;7:1–6.

Google Scholar

Ferrari JR, Díaz-Morales JF, O’Callaghan J, Díaz K, Argumedo D. Frequent behavioral Delay tendencies by adults. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2007;38:458–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107302314 .