Why education is the key to development

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Børge Brende

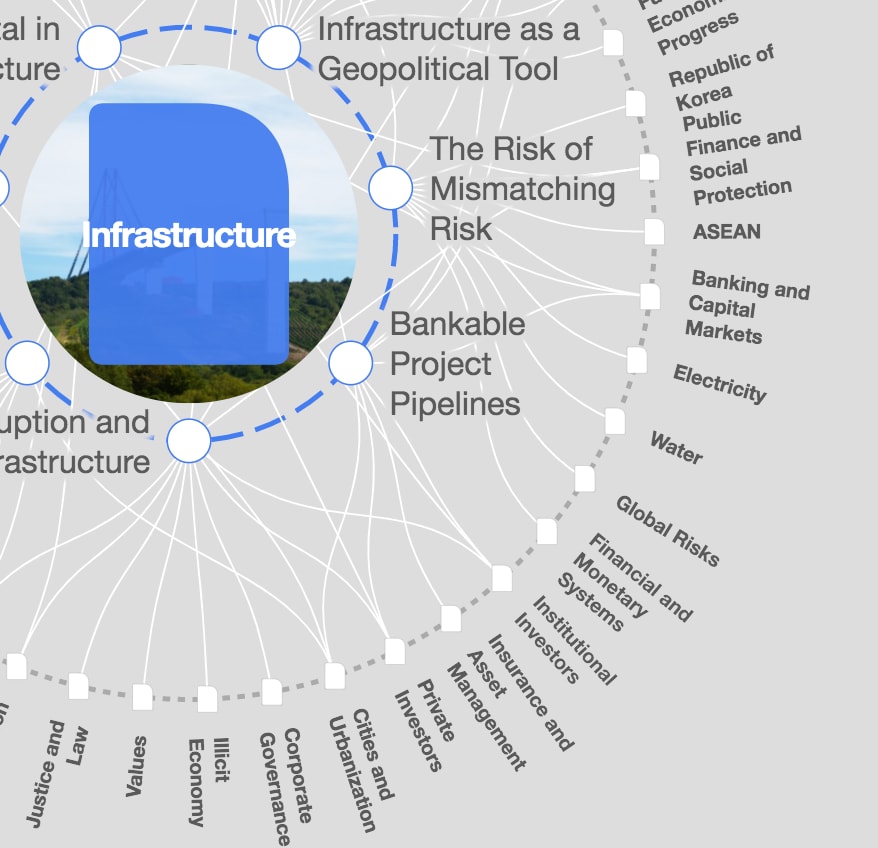

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Infrastructure is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, infrastructure.

Education is a human right. And, like other human rights, it cannot be taken for granted. Across the world, 59 million children and 65 million adolescents are out of school . More than 120 million children do not complete primary education.

Behind these figures there are children and youth being denied not only a right, but opportunities: a fair chance to get a decent job, to escape poverty, to support their families, and to develop their communities. This year, decision-makers will set the priorities for global development for the next 15 years. They should make sure to place education high on the list.

The deadline for the Millennium Development Goals is fast approaching. We have a responsibility to make sure we fulfill the promise we made at the beginning of the millennium: to ensure that boys and girls everywhere complete a full course of primary schooling.

The challenge is daunting. Many of those who remain out of school are the hardest to reach, as they live in countries that are held back by conflict, disaster, and epidemics. And the last push is unlikely to be accompanied by the double-digit economic growth in some developing economies that makes it easier to expand opportunities.

Nevertheless, we can succeed. Over the last 15 years, governments and their partners have shown that political will and concerted efforts can deliver tremendous results – including halving the number of children and adolescents who are out of school. Moreover, most countries are closing in on gender parity at the primary level. Now is the time to redouble our efforts to finish what we started.

But we must not stop with primary education. In today’s knowledge-driven economies, access to quality education and the chances for development are two sides of the same coin. That is why we must also set targets for secondary education, while improving quality and learning outcomes at all levels. That is what the Sustainable Development Goal on education, which world leaders will adopt this year, aims to do.

Addressing the fact that an estimated 250 million children worldwide are not learning the basic skills they need to enter the labor market is more than a moral obligation. It amounts to an investment in sustainable growth and prosperity. For both countries and individuals, there is a direct and indisputable link between access to quality education and economic and social development.

Likewise, ensuring that girls are not kept at home when they reach puberty, but are allowed to complete education on the same footing as their male counterparts, is not just altruism; it is sound economics. Communities and countries that succeed in achieving gender parity in education will reap substantial benefits relating to health, equality, and job creation.

All countries, regardless of their national wealth, stand to gain from more and better education. According to a recent OECD report , providing every child with access to education and the skills needed to participate fully in society would boost GDP by an average 28% per year in lower-income countries and 16% per year in high-income countries for the next 80 years.

Today’s students need “twenty-first-century skills,” like critical thinking, problem solving, creativity, and digital literacy. Learners of all ages need to become familiar with new technologies and cope with rapidly changing workplaces.

According to the International Labour Organization, an additional 280 million jobs will be needed by 2019. It is vital for policymakers to ensure that the right frameworks and incentives are established so that those jobs can be created and filled. Robust education systems – underpinned by qualified, professionally trained, motivated, and well-supported teachers – will be the cornerstone of this effort.

Governments should work with parent and teacher associations, as well as the private sector and civil-society organizations, to find the best and most constructive ways to improve the quality of education. Innovation has to be harnessed, and new partnerships must be forged.

Of course, this will cost money. According to UNESCO, in order to meet our basic education targets by 2030, we must close an external annual financing gap of about $22 billion. But we have the resources necessary to deliver. What is lacking is the political will to make the needed investments.

This is the challenge that inspired Norway to invite world leaders to Oslo for a Summit on Education for Development , where we can develop strategies for mobilizing political support for increasing financing for education. For the first time in history, we are in the unique position to provide education opportunities for all, if only we pull together. We cannot miss this critical opportunity.

To be sure, the responsibility for providing citizens with a quality education rests, first and foremost, with national governments. Aid cannot replace domestic-resource mobilization. But donor countries also have an important role to play, especially in supporting least-developed countries. We must reverse the recent downward trend in development assistance for education, and leverage our assistance to attract investments from various other sources. For our part, we are in the process of doubling Norway’s financial contribution to education for development in the period 2013-2017.

Together, we need to intensify efforts to bring the poorest and hardest to reach children into the education system. Education is a right for everyone. It is a right for girls, just as it is for boys. It is a right for disabled children, just as it is for everyone else. It is a right for the 37 million out-of-school children and youth in countries affected by crises and conflicts. Education is a right regardless of where you are born and where you grow up. It is time to ensure that the right is upheld.

This article is published in collaboration with Project Syndicate . Publication does not imply endorsement of views by the World Economic Forum.

To keep up with the Agenda subscribe to our weekly newsletter .

Author: Erna Solberg is Prime Minister of Norway. Børge Brende is Norway’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Image: Students attend a class at the Oxford International College in Changzhou. REUTERS/Aly Song.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Growth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Eurozone recovery begins and other economics stories to read

Kate Whiting

May 17, 2024

The ZiG: Zimbabwe rolls out world’s newest currency. Here’s what to know

Spencer Feingold

Why companies who pay a living wage create wider societal benefits

Sanda Ojiambo

May 14, 2024

The economic challenges and opportunities for MENA, according to experts at #SpecialMeeting24

May 13, 2024

UK leaves recession with fastest growth in 3 years, and other economics stories to read

May 10, 2024

How a pair of reading glasses could increase your income

Emma Charlton

May 8, 2024

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 94 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

Education is a human right, a powerful driver of development, and one of the strongest instruments for reducing poverty and improving health, gender equality, peace, and stability. It delivers large, consistent returns in terms of income, and is the most important factor to ensure equity and inclusion.

For individuals, education promotes employment, earnings, health, and poverty reduction. Globally, there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling . For societies, it drives long-term economic growth, spurs innovation, strengthens institutions, and fosters social cohesion. Education is further a powerful catalyst to climate action through widespread behavior change and skilling for green transitions.

Developing countries have made tremendous progress in getting children into the classroom and more children worldwide are now in school. But learning is not guaranteed, as the 2018 World Development Report (WDR) stressed.

Making smart and effective investments in people’s education is critical for developing the human capital that will end extreme poverty. At the core of this strategy is the need to tackle the learning crisis, put an end to Learning Poverty , and help youth acquire the advanced cognitive, socioemotional, technical and digital skills they need to succeed in today’s world.

In low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty (that is, the proportion of 10-year-old children that are unable to read and understand a short age-appropriate text) increased from 57% before the pandemic to an estimated 70% in 2022.

However, learning is in crisis. More than 70 million more people were pushed into poverty during the COVID pandemic, a billion children lost a year of school , and three years later the learning losses suffered have not been recouped . If a child cannot read with comprehension by age 10, they are unlikely to become fluent readers. They will fail to thrive later in school and will be unable to power their careers and economies once they leave school.

The effects of the pandemic are expected to be long-lasting. Analysis has already revealed deep losses, with international reading scores declining from 2016 to 2021 by more than a year of schooling. These losses may translate to a 0.68 percentage point in global GDP growth. The staggering effects of school closures reach beyond learning. This generation of children could lose a combined total of US$21 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value or the equivalent of 17% of today’s global GDP – a sharp rise from the 2021 estimate of a US$17 trillion loss.

Action is urgently needed now – business as usual will not suffice to heal the scars of the pandemic and will not accelerate progress enough to meet the ambitions of SDG 4. We are urging governments to implement ambitious and aggressive Learning Acceleration Programs to get children back to school, recover lost learning, and advance progress by building better, more equitable and resilient education systems.

Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024

The World Bank’s global education strategy is centered on ensuring learning happens – for everyone, everywhere. Our vision is to ensure that everyone can achieve her or his full potential with access to a quality education and lifelong learning. To reach this, we are helping countries build foundational skills like literacy, numeracy, and socioemotional skills – the building blocks for all other learning. From early childhood to tertiary education and beyond – we help children and youth acquire the skills they need to thrive in school, the labor market and throughout their lives.

Investing in the world’s most precious resource – people – is paramount to ending poverty on a livable planet. Our experience across more than 100 countries bears out this robust connection between human capital, quality of life, and economic growth: when countries strategically invest in people and the systems designed to protect and build human capital at scale, they unlock the wealth of nations and the potential of everyone.

Building on this, the World Bank supports resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone. We do this by generating and disseminating evidence, ensuring alignment with policymaking processes, and bridging the gap between research and practice.

The World Bank is the largest source of external financing for education in developing countries, with a portfolio of about $26 billion in 94 countries including IBRD, IDA and Recipient-Executed Trust Funds. IDA operations comprise 62% of the education portfolio.

The investment in FCV settings has increased dramatically and now accounts for 26% of our portfolio.

World Bank projects reach at least 425 million students -one-third of students in low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank’s Approach to Education

Five interrelated pillars of a well-functioning education system underpin the World Bank’s education policy approach:

- Learners are prepared and motivated to learn;

- Teachers are prepared, skilled, and motivated to facilitate learning and skills acquisition;

- Learning resources (including education technology) are available, relevant, and used to improve teaching and learning;

- Schools are safe and inclusive; and

- Education Systems are well-managed, with good implementation capacity and adequate financing.

The Bank is already helping governments design and implement cost-effective programs and tools to build these pillars.

Our Principles:

- We pursue systemic reform supported by political commitment to learning for all children.

- We focus on equity and inclusion through a progressive path toward achieving universal access to quality education, including children and young adults in fragile or conflict affected areas , those in marginalized and rural communities, girls and women , displaced populations, students with disabilities , and other vulnerable groups.

- We focus on results and use evidence to keep improving policy by using metrics to guide improvements.

- We want to ensure financial commitment commensurate with what is needed to provide basic services to all.

- We invest wisely in technology so that education systems embrace and learn to harness technology to support their learning objectives.

Laying the groundwork for the future

Country challenges vary, but there is a menu of options to build forward better, more resilient, and equitable education systems.

Countries are facing an education crisis that requires a two-pronged approach: first, supporting actions to recover lost time through remedial and accelerated learning; and, second, building on these investments for a more equitable, resilient, and effective system.

Recovering from the learning crisis must be a political priority, backed with adequate financing and the resolve to implement needed reforms. Domestic financing for education over the last two years has not kept pace with the need to recover and accelerate learning. Across low- and lower-middle-income countries, the average share of education in government budgets fell during the pandemic , and in 2022 it remained below 2019 levels.

The best chance for a better future is to invest in education and make sure each dollar is put toward improving learning. In a time of fiscal pressure, protecting spending that yields long-run gains – like spending on education – will maximize impact. We still need more and better funding for education. Closing the learning gap will require increasing the level, efficiency, and equity of education spending—spending smarter is an imperative.

- Education technology can be a powerful tool to implement these actions by supporting teachers, children, principals, and parents; expanding accessible digital learning platforms, including radio/ TV / Online learning resources; and using data to identify and help at-risk children, personalize learning, and improve service delivery.

Looking ahead

We must seize this opportunity to reimagine education in bold ways. Together, we can build forward better more equitable, effective, and resilient education systems for the world’s children and youth.

Accelerating Improvements

Supporting countries in establishing time-bound learning targets and a focused education investment plan, outlining actions and investments geared to achieve these goals.

Launched in 2020, the Accelerator Program works with a set of countries to channel investments in education and to learn from each other. The program coordinates efforts across partners to ensure that the countries in the program show improvements in foundational skills at scale over the next three to five years. These investment plans build on the collective work of multiple partners, and leverage the latest evidence on what works, and how best to plan for implementation. Countries such as Brazil (the state of Ceará) and Kenya have achieved dramatic reductions in learning poverty over the past decade at scale, providing useful lessons, even as they seek to build on their successes and address remaining and new challenges.

Universalizing Foundational Literacy

Readying children for the future by supporting acquisition of foundational skills – which are the gateway to other skills and subjects.

The Literacy Policy Package (LPP) consists of interventions focused specifically on promoting acquisition of reading proficiency in primary school. These include assuring political and technical commitment to making all children literate; ensuring effective literacy instruction by supporting teachers; providing quality, age-appropriate books; teaching children first in the language they speak and understand best; and fostering children’s oral language abilities and love of books and reading.

Advancing skills through TVET and Tertiary

Ensuring that individuals have access to quality education and training opportunities and supporting links to employment.

Tertiary education and skills systems are a driver of major development agendas, including human capital, climate change, youth and women’s empowerment, and jobs and economic transformation. A comprehensive skill set to succeed in the 21st century labor market consists of foundational and higher order skills, socio-emotional skills, specialized skills, and digital skills. Yet most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development.

The World Bank is supporting countries through efforts that address key challenges including improving access and completion, adaptability, quality, relevance, and efficiency of skills development programs. Our approach is via multiple channels including projects, global goods, as well as the Tertiary Education and Skills Program . Our recent reports including Building Better Formal TVET Systems and STEERing Tertiary Education provide a way forward for how to improve these critical systems.

Addressing Climate Change

Mainstreaming climate education and investing in green skills, research and innovation, and green infrastructure to spur climate action and foster better preparedness and resilience to climate shocks.

Our approach recognizes that education is critical for achieving effective, sustained climate action. At the same time, climate change is adversely impacting education outcomes. Investments in education can play a huge role in building climate resilience and advancing climate mitigation and adaptation. Climate change education gives young people greater awareness of climate risks and more access to tools and solutions for addressing these risks and managing related shocks. Technical and vocational education and training can also accelerate a green economic transformation by fostering green skills and innovation. Greening education infrastructure can help mitigate the impact of heat, pollution, and extreme weather on learning, while helping address climate change.

Examples of this work are projects in Nigeria (life skills training for adolescent girls), Vietnam (fostering relevant scientific research) , and Bangladesh (constructing and retrofitting schools to serve as cyclone shelters).

Strengthening Measurement Systems

Enabling countries to gather and evaluate information on learning and its drivers more efficiently and effectively.

The World Bank supports initiatives to help countries effectively build and strengthen their measurement systems to facilitate evidence-based decision-making. Examples of this work include:

(1) The Global Education Policy Dashboard (GEPD) : This tool offers a strong basis for identifying priorities for investment and policy reforms that are suited to each country context by focusing on the three dimensions of practices, policies, and politics.

- Highlights gaps between what the evidence suggests is effective in promoting learning and what is happening in practice in each system; and

- Allows governments to track progress as they act to close the gaps.

The GEPD has been implemented in 13 education systems already – Peru, Rwanda, Jordan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Islamabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sierra Leone, Niger, Gabon, Jordan and Chad – with more expected by the end of 2024.

(2) Learning Assessment Platform (LeAP) : LeAP is a one-stop shop for knowledge, capacity-building tools, support for policy dialogue, and technical staff expertise to support student achievement measurement and national assessments for better learning.

Supporting Successful Teachers

Helping systems develop the right selection, incentives, and support to the professional development of teachers.

Currently, the World Bank Education Global Practice has over 160 active projects supporting over 18 million teachers worldwide, about a third of the teacher population in low- and middle-income countries. In 12 countries alone, these projects cover 16 million teachers, including all primary school teachers in Ethiopia and Turkey, and over 80% in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

A World Bank-developed classroom observation tool, Teach, was designed to capture the quality of teaching in low- and middle-income countries. It is now 3.6 million students.

While Teach helps identify patterns in teacher performance, Coach leverages these insights to support teachers to improve their teaching practice through hands-on in-service teacher professional development (TPD).

Our recent report on Making Teacher Policy Work proposes a practical framework to uncover the black box of effective teacher policy and discusses the factors that enable their scalability and sustainability.

Supporting Education Finance Systems

Strengthening country financing systems to mobilize resources for education and make better use of their investments in education.

Our approach is to bring together multi-sectoral expertise to engage with ministries of education and finance and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective and efficient public financial management systems; build capacity to monitor and evaluate education spending, identify financing bottlenecks, and develop interventions to strengthen financing systems; build the evidence base on global spending patterns and the magnitude and causes of spending inefficiencies; and develop diagnostic tools as public goods to support country efforts.

Working in Fragile, Conflict, and Violent (FCV) Contexts

The massive and growing global challenge of having so many children living in conflict and violent situations requires a response at the same scale and scope. Our education engagement in the Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV) context, which stands at US$5.35 billion, has grown rapidly in recent years, reflecting the ever-increasing importance of the FCV agenda in education. Indeed, these projects now account for more than 25% of the World Bank education portfolio.

Education is crucial to minimizing the effects of fragility and displacement on the welfare of youth and children in the short-term and preventing the emergence of violent conflict in the long-term.

Support to Countries Throughout the Education Cycle

Our support to countries covers the entire learning cycle, to help shape resilient, equitable, and inclusive education systems that ensure learning happens for everyone.

The ongoing Supporting Egypt Education Reform project , 2018-2025, supports transformational reforms of the Egyptian education system, by improving teaching and learning conditions in public schools. The World Bank has invested $500 million in the project focused on increasing access to quality kindergarten, enhancing the capacity of teachers and education leaders, developing a reliable student assessment system, and introducing the use of modern technology for teaching and learning. Specifically, the share of Egyptian 10-year-old students, who could read and comprehend at the global minimum proficiency level, increased to 45 percent in 2021.

In Nigeria , the $75 million Edo Basic Education Sector and Skills Transformation (EdoBESST) project, running from 2020-2024, is focused on improving teaching and learning in basic education. Under the project, which covers 97 percent of schools in the state, there is a strong focus on incorporating digital technologies for teachers. They were equipped with handheld tablets with structured lesson plans for their classes. Their coaches use classroom observation tools to provide individualized feedback. Teacher absence has reduced drastically because of the initiative. Over 16,000 teachers were trained through the project, and the introduction of technology has also benefited students.

Through the $235 million School Sector Development Program in Nepal (2017-2022), the number of children staying in school until Grade 12 nearly tripled, and the number of out-of-school children fell by almost seven percent. During the pandemic, innovative approaches were needed to continue education. Mobile phone penetration is high in the country. More than four in five households in Nepal have mobile phones. The project supported an educational service that made it possible for children with phones to connect to local radio that broadcast learning programs.

From 2017-2023, the $50 million Strengthening of State Universities in Chile project has made strides to improve quality and equity at state universities. The project helped reduce dropout: the third-year dropout rate fell by almost 10 percent from 2018-2022, keeping more students in school.

The World Bank’s first Program-for-Results financing in education was through a $202 million project in Tanzania , that ran from 2013-2021. The project linked funding to results and aimed to improve education quality. It helped build capacity, and enhanced effectiveness and efficiency in the education sector. Through the project, learning outcomes significantly improved alongside an unprecedented expansion of access to education for children in Tanzania. From 2013-2019, an additional 1.8 million students enrolled in primary schools. In 2019, the average reading speed for Grade 2 students rose to 22.3 words per minute, up from 17.3 in 2017. The project laid the foundation for the ongoing $500 million BOOST project , which supports over 12 million children to enroll early, develop strong foundational skills, and complete a quality education.

The $40 million Cambodia Secondary Education Improvement project , which ran from 2017-2022, focused on strengthening school-based management, upgrading teacher qualifications, and building classrooms in Cambodia, to improve learning outcomes, and reduce student dropout at the secondary school level. The project has directly benefited almost 70,000 students in 100 target schools, and approximately 2,000 teachers and 600 school administrators received training.

The World Bank is co-financing the $152.80 million Yemen Restoring Education and Learning Emergency project , running from 2020-2024, which is implemented through UNICEF, WFP, and Save the Children. It is helping to maintain access to basic education for many students, improve learning conditions in schools, and is working to strengthen overall education sector capacity. In the time of crisis, the project is supporting teacher payments and teacher training, school meals, school infrastructure development, and the distribution of learning materials and school supplies. To date, almost 600,000 students have benefited from these interventions.

The $87 million Providing an Education of Quality in Haiti project supported approximately 380 schools in the Southern region of Haiti from 2016-2023. Despite a highly challenging context of political instability and recurrent natural disasters, the project successfully supported access to education for students. The project provided textbooks, fresh meals, and teacher training support to 70,000 students, 3,000 teachers, and 300 school directors. It gave tuition waivers to 35,000 students in 118 non-public schools. The project also repaired 19 national schools damaged by the 2021 earthquake, which gave 5,500 students safe access to their schools again.

In 2013, just 5% of the poorest households in Uzbekistan had children enrolled in preschools. Thanks to the Improving Pre-Primary and General Secondary Education Project , by July 2019, around 100,000 children will have benefitted from the half-day program in 2,420 rural kindergartens, comprising around 49% of all preschool educational institutions, or over 90% of rural kindergartens in the country.

In addition to working closely with governments in our client countries, the World Bank also works at the global, regional, and local levels with a range of technical partners, including foundations, non-profit organizations, bilaterals, and other multilateral organizations. Some examples of our most recent global partnerships include:

UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: Coalition for Foundational Learning

The World Bank is working closely with UNICEF, UNESCO, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as the Coalition for Foundational Learning to advocate and provide technical support to ensure foundational learning. The World Bank works with these partners to promote and endorse the Commitment to Action on Foundational Learning , a global network of countries committed to halving the global share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 by 2030.

Australian Aid, Bernard van Leer Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canada, Echida Giving, FCDO, German Cooperation, William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, Conrad Hilton Foundation, LEGO Foundation, Porticus, USAID: Early Learning Partnership

The Early Learning Partnership (ELP) is a multi-donor trust fund, housed at the World Bank. ELP leverages World Bank strengths—a global presence, access to policymakers and strong technical analysis—to improve early learning opportunities and outcomes for young children around the world.

We help World Bank teams and countries get the information they need to make the case to invest in Early Childhood Development (ECD), design effective policies and deliver impactful programs. At the country level, ELP grants provide teams with resources for early seed investments that can generate large financial commitments through World Bank finance and government resources. At the global level, ELP research and special initiatives work to fill knowledge gaps, build capacity and generate public goods.

UNESCO, UNICEF: Learning Data Compact

UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank have joined forces to close the learning data gaps that still exist and that preclude many countries from monitoring the quality of their education systems and assessing if their students are learning. The three organizations have agreed to a Learning Data Compact , a commitment to ensure that all countries, especially low-income countries, have at least one quality measure of learning by 2025, supporting coordinated efforts to strengthen national assessment systems.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Learning Poverty Indicator

Aimed at measuring and urging attention to foundational literacy as a prerequisite to achieve SDG4, this partnership was launched in 2019 to help countries strengthen their learning assessment systems, better monitor what students are learning in internationally comparable ways and improve the breadth and quality of global data on education.

FCDO, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: EdTech Hub

Supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), in partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the EdTech Hub is aimed at improving the quality of ed-tech investments. The Hub launched a rapid response Helpdesk service to provide just-in-time advisory support to 70 low- and middle-income countries planning education technology and remote learning initiatives.

MasterCard Foundation

Our Tertiary Education and Skills global program, launched with support from the Mastercard Foundation, aims to prepare youth and adults for the future of work and society by improving access to relevant, quality, equitable reskilling and post-secondary education opportunities. It is designed to reframe, reform, and rebuild tertiary education and skills systems for the digital and green transformation.

Bridging the AI divide: Breaking down barriers to ensure women’s leadership and participation in the Fifth Industrial Revolution

Common challenges and tailored solutions: How policymakers are strengthening early learning systems across the world

Compulsory education boosts learning outcomes and climate action

Areas of focus.

Data & Measurement

Early Childhood Development

Financing Education

Foundational Learning

Fragile, Conflict & Violent Contexts

Girls’ Education

Inclusive Education

Skills Development

Technology (EdTech)

Tertiary Education

Initiatives

- Show More +

- Tertiary Education and Skills Program

- Service Delivery Indicators

- Evoke: Transforming education to empower youth

- Global Education Policy Dashboard

- Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel

- Show Less -

Collapse and Recovery: How the COVID-19 Pandemic Eroded Human Capital and What to Do About It

BROCHURES & FACT SHEETS

Flyer: Education Factsheet - May 2024

Publication: Realizing Education's Promise: A World Bank Retrospective – August 2023

Flyer: Education and Climate Change - November 2022

Brochure: Learning Losses - October 2022

STAY CONNECTED

Human Development Topics

Around the bank group.

Find out what the Bank Group's branches are doing in education

Global Education Newsletter - April 2024

What's happening in the World Bank Education Global Practice? Read to learn more.

Human Capital Project

The Human Capital Project is a global effort to accelerate more and better investments in people for greater equity and economic growth.

Impact Evaluations

Research that measures the impact of education policies to improve education in low and middle income countries.

Education Videos

Watch our latest videos featuring our projects across the world

Additional Resources

Education Finance

Higher Education

Digital Technologies

Education Data & Measurement

Education in Fragile, Conflict & Violence Contexts

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Why education matters for economic development

Harry a. patrinos.

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

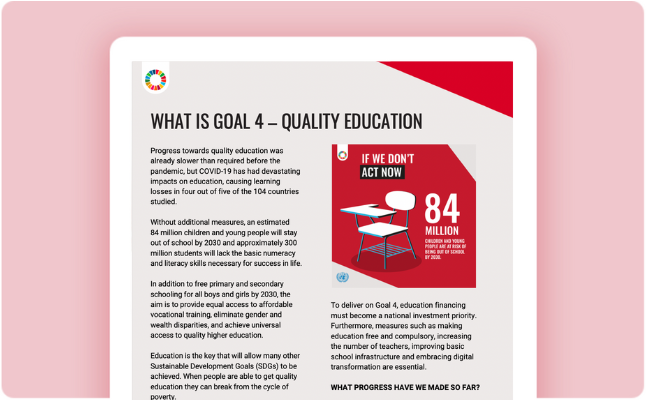

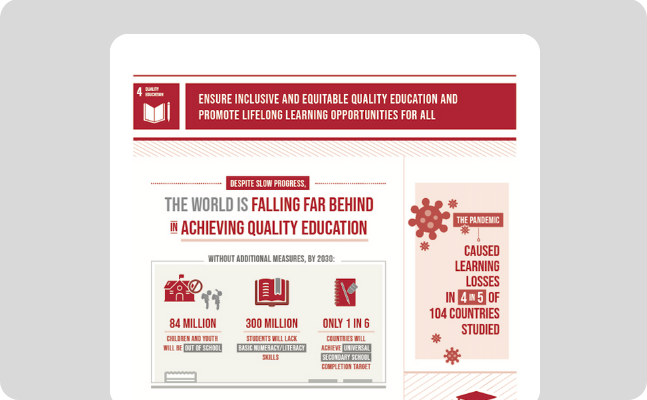

- Progress towards quality education was already slower than required before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has had devastating impacts on education, causing learning losses in four out of five of the 104 countries studied.

Without additional measures, an estimated 84 million children and young people will stay out of school by 2030 and approximately 300 million students will lack the basic numeracy and literacy skills necessary for success in life.

In addition to free primary and secondary schooling for all boys and girls by 2030, the aim is to provide equal access to affordable vocational training, eliminate gender and wealth disparities, and achieve universal access to quality higher education.

Education is the key that will allow many other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved. When people are able to get quality education they can break from the cycle of poverty.

Education helps to reduce inequalities and to reach gender equality. It also empowers people everywhere to live more healthy and sustainable lives. Education is also crucial to fostering tolerance between people and contributes to more peaceful societies.

- To deliver on Goal 4, education financing must become a national investment priority. Furthermore, measures such as making education free and compulsory, increasing the number of teachers, improving basic school infrastructure and embracing digital transformation are essential.

What progress have we made so far?

While progress has been made towards the 2030 education targets set by the United Nations, continued efforts are required to address persistent challenges and ensure that quality education is accessible to all, leaving no one behind.

Between 2015 and 2021, there was an increase in worldwide primary school completion, lower secondary completion, and upper secondary completion. Nevertheless, the progress made during this period was notably slower compared to the 15 years prior.

What challenges remain?

According to national education targets, the percentage of students attaining basic reading skills by the end of primary school is projected to rise from 51 per cent in 2015 to 67 per cent by 2030. However, an estimated 300 million children and young people will still lack basic numeracy and literacy skills by 2030.

Economic constraints, coupled with issues of learning outcomes and dropout rates, persist in marginalized areas, underscoring the need for continued global commitment to ensuring inclusive and equitable education for all. Low levels of information and communications technology (ICT) skills are also a major barrier to achieving universal and meaningful connectivity.

Where are people struggling the most to have access to education?

Sub-Saharan Africa faces the biggest challenges in providing schools with basic resources. The situation is extreme at the primary and lower secondary levels, where less than one-half of schools in sub-Saharan Africa have access to drinking water, electricity, computers and the Internet.

Inequalities will also worsen unless the digital divide – the gap between under-connected and highly digitalized countries – is not addressed .

Are there groups that have more difficult access to education?

Yes, women and girls are one of these groups. About 40 per cent of countries have not achieved gender parity in primary education. These disadvantages in education also translate into lack of access to skills and limited opportunities in the labour market for young women.

What can we do?

Ask our governments to place education as a priority in both policy and practice. Lobby our governments to make firm commitments to provide free primary school education to all, including vulnerable or marginalized groups.

Facts and figures

Goal 4 targets.

- Without additional measures, only one in six countries will achieve the universal secondary school completion target by 2030, an estimated 84 million children and young people will still be out of school, and approximately 300 million students will lack the basic numeracy and literacy skills necessary for success in life.

- To achieve national Goal 4 benchmarks, which are reduced in ambition compared with the original Goal 4 targets, 79 low- and lower-middle- income countries still face an average annual financing gap of $97 billion.

Source: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

4.1 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and Goal-4 effective learning outcomes

4.2 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and preprimary education so that they are ready for primary education

4.3 By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

4.4 By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

4.5 By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations

4.6 By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

4.7 By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

4.A Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, nonviolent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all

4.B By 2020, substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States and African countries, for enrolment in higher education, including vocational training and information and communications technology, technical, engineering and scientific programmes, in developed countries and other developing countries

4.C By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing states

UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UN Children’s Fund

UN Development Programme

Global Education First Initiative

UN Population Fund: Comprehensive sexuality education

UN Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth

Fast Facts: Quality Education

Infographic: Quality Education

Related news

‘Education is a human right,’ UN Summit Adviser says, urging action to tackle ‘crisis of access, learning and relevance’

Masayoshi Suga 2022-09-15T11:50:20-04:00 14 Sep 2022 |

14 September, NEW YORK – Education is a human right - those who are excluded must fight for their right, Leonardo Garnier, Costa Rica’s former education minister, emphasized, ahead of a major United Nations [...]

Showcasing nature-based solutions: Meet the UN prize winners

Masayoshi Suga 2022-08-13T22:16:45-04:00 11 Aug 2022 |

NEW YORK, 11 August – The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and partners have announced the winners of the 13th Equator Prize, recognizing ten indigenous peoples and local communities from nine countries. The winners, selected from a [...]

UN and partners roll out #LetMeLearn campaign ahead of Education Summit

Yinuo 2022-08-10T09:27:23-04:00 01 Aug 2022 |

New York, 1 August – Amid the education crisis exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations is partnering with children's charity Theirworld to launch the #LetMeLearn campaign, urging world leaders to hear the [...]

Related videos

Malala yousafzai (un messenger of peace) on “financing the future: education 2030”.

VIDEO: Climate education at COP22

From the football field to the classrooms of Nepal | UNICEF

Share this story, choose your platform!

- Student Outreach

- Research Support

- Executive Education

- News & Announcements

- Jobs & Opportunities

- Annual Reports

- Faculty Working Papers

- Building State Capability

- Colombia Education Initiative

- Evidence for Policy Design

- Reimagining the Economy

- Social Protection Initiative

- Past Programs

- Speaker Series

- Global Empowerment Meeting (GEM)

- NEUDC 2023 Conference

National Development Delivers: And How! And How?

In this section, national development delivers: and how and how , cid faculty working paper no. 398.

Lant Pritchett May 2021

Core dual ideas of early development economics and practice were that (a) national development was a four-fold transformation of countries towards: (i) a more productive economy, (ii) a more responsive state, (iii) more capable administration, and (iv) a shared identity and equal treatment of citizens and (b) this four-fold transformation of national development would lead to higher levels of human wellbeing. The second idea is strikingly correct: development delivers. National development is empirically necessary for high wellbeing (no country with low levels of national development has high human wellbeing) and also empirically sufficient (no country with high national development has low levels of human wellbeing). Three measures of national development: productive economy, capable administration, and responsive state, explain (essentially) all of the observed variation in an omnibus indicator of wellbeing, the Social Progress Index, which is based on 58 distinct non-economic indicators. How national development delivers on wellbeing varies, in three ways. One, economic growth is much more important for achieving wellbeing at low versus high levels of income. Two, economic growth matters more for “basic needs” than for other dimensions of wellbeing (like social inclusiveness or environmental quality). Three, state capability matters more for wellbeing outcomes that depend on public production than on private goods (and for some wellbeing indicators, like physical safety, for which growth doesn’t matter at all). While these findings may seem too common sense to be worth a paper, national development--and particularly economic growth—is, strangely, under severe challenge as an important and legitimate objective of action within the development industry.

Affiliated Program: Building State Capability

- ENVIRONMENT

- FOOD & RECIPES

- HOME IMPROVEMENT

The Role of Education in National Development

Education refers to the field of study that deals mainly with teaching and learning methods in schools. The primary aim of education is to promote a person’s overall development. It is also a source of its evident advantages for a more prosperous and happier existence.

Education has the potential to improve society as a whole. It helps create a community where individuals know their rights and responsibilities. Education is a learning and cultural process where people may acquire cognitive ability, physical abilities, and values and beliefs. These abilities enable us to be decent citizens.

National Development refers to a country’s ability to improve its citizens’ living standards. National development may be accomplished through meeting fundamental livelihood needs and providing work, among other things. Growth, progress, and good change are all part of the development process. Therefore, growth is a positive indicator.

One of the components of national development includes the development and urbanization of rural areas. Another is the increment in agricultural outputs to help eradicate poverty. Others include the enlargement of economic knowledge and proper growth handling in urban areas.

There are two elements to development-growth in the economy or a rise in people’s income:

Literacy, health, and the provision of public services are all examples of social development.

Education aids production by providing men and women with the latest scientific and technological information. To improve national income, education must link to productivity, the entire output of final products and services in real terms.

Making S.U.P.W. (Socially Useful Productive Work) and vocational education, especially at the secondary school level, an intrinsic element of general education to satisfy the demands of industry, agriculture, and commerce would help the national economy.

Education has also improved national development by enhancing university-level scientific and technical education and research, focusing on agriculture and related sciences.

Education has aided national development through talent and virtue development. The nurturing of abilities and practical qualities is the cornerstone of a nation’s development.

The indices of national growth include an awakened mind, correct information, advanced skills, and desired attitudes. Education aids in developing latent abilities or aptitudes to harness the process of national and personal growth.

Developing skills and values through an appropriate educational curriculum undoubtedly adds to a nation’s success. As a result, education is viewed as a tool for harnessing abilities and values for the overall development of a country.

Education helps nurture and improve students’ writing skills as they are taught to write in schools, which equips them with the necessary skills to be ardent writers, editors, and the like. Although, with the advent of technology, there are now websites where people can seek help with their writing projects, such as the best custom writing service .

Physical, cerebral, social, emotional, moral, spiritual, and aesthetic developments of the individual personality are all goals of education. National development is not feasible without personal growth. Individual development includes:

● The development of self-confidence. ● The development of scientific temperament. ● The attainment of self-sufficiency. ● A sense of duty. ● Discipline and decency. ● A sense of dedication. ● The promotion of social and ethical values. ● The cultivation of social efficiency. ● The promotion of social and moral values.

As a result, education aids individuals in creating and cultivating the attributes mentioned above, which are necessary for a nation’s revival and progress. Therefore, all sectors of the population should have access to education.

The royal route to national progress is supposed to be modernization. Education contributes to national development by instilling curiosity, suitable interests, attitudes, and values and developing necessary abilities such as independent study and the ability to analyze and evaluate correctly. It also assists by using new teaching techniques and altering the composition of the intelligentsia and educated individuals from all walks of life. Furthermore, it emphasizes vocational education, science-based education, and research as development catalysts. These, in turn, transform into the development of a country.

Internationalism is critical for national development, such as national integration. It can be encouraged through education by emphasizing diverse nations’ significant contributions to humanity’s progress and reinstating the right viewpoints in textbooks by removing malicious content about other civilizations.

It can also be achieved by assisting in developing a global outlook and eliminating negative attitudes among pupils toward different communities or races throughout the universe.

Therefore, education is crucial in achieving national development. Education is an excellent vehicle for attaining actual national development. A nation cannot remain oblivious to its role in education.

Trending Stocks: GameStop and AMC – The Market Phenomena

Creating a cohesive aesthetic: the role of lighting in home design, the benefits of automating corporate gifting, sex offender registration requirements in california, beat the odds: first aid do’s and don’ts for heart attacks.

- Privacy Policy

This site belongs to UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning

IIEP Learning Portal

Search form

- issue briefs

- Improve learning

School and learning readiness

The Education 2030 Framework for Action defines school readiness as ‘the achievement of developmental milestones across a range of domains, including adequate health and nutritional status, and age-appropriate language, cognitive, social and emotional development’ (UNESCO, 2016: 39). SDG Target 4.2 aims to ensure that all children have access to quality early childhood development, care, and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education. While early childhood care and family support play a critical role in preparing children for school, the present brief focuses on the organized learning component of early childhood development – that is, pre-primary or early childhood education (ECE).

What we know

Disparities in ECE enrolment are significant between countries and tend to be higher than for other education levels. National and regional data is mainly available for pre-primary formal education under the indicators ‘Participation rate in organized learning one year before official primary entry age’ (SDG indicator 4.2.2) and ‘School enrolment, pre-primary’. In terms of SDG 4.2.2, the enrolment rate at the global level stands at 67.2 per cent (2018); however, broken down at the regional level, the rate stands at just 42 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa but 96 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2020). Gender disparities in access are less common in ECE programmes than at other levels. According to the 2007 Global Monitoring Report, pre-primary gender disparities at the expense of girls are found mostly in countries with very low gross enrolment ratios (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006).

While access to pre-primary education has expanded, the quality of programmes has usually remained low. The universalization of primary education led to a drop in quality and this risk prevails for pre-primary education. When access is increased, children’s outcomes do not always improve. At times, efforts to increase access may exacerbate the problem of low quality (UNESCO, 2017). Findings suggest that high-quality ECE yields beneficial effects that last until secondary school, even when primary school is of mediocre quality, while poor pre-primary quality may even be harmful for brain development (UNESCO, 2015). The quality of ECE services depends mainly on a child-friendly and supportive learning environment, a developmentally appropriate play-based curriculum, sufficient learning materials, and, most importantly, well-trained and qualified teachers (IIEP, GPE, UNICEF, 2019)

One of the main determinants of quality pre-primary education is the quality of the education workforce; their level of education and participation in training is a better predictor of quality than factors such as child–staff ratios or group size (Putcha, 2018). While teachers are already in short supply, a significant increase in numbers is required as countries look to achieve universal pre-primary education (UNICEF, 2019). According to UIS 2019 data, the percentage of qualified teachers in pre-primary education is 80.5 per cent at the global level and only 60.5 per cent in low-income countries. The level of remuneration, working conditions, and status of the ECE workforce is often poor; this leads to recruitment challenges and high attrition rates (Putcha, 2018).

Costs and financing

Pre-primary education is underfunded compared to other education levels, with an investment gap of almost 90 per cent in low-income countries and 75 per cent in lower-middle-income countries. Globally, 38 per cent of countries invest less than 2 per cent of their education budgets in pre-primary education (UNICEF, 2019). The Education Commission (2016) estimates that providing universal access to pre-primary education in low- and lower-middle-income countries by 2030 would require an investment of $44 billion per year if countries pursue the guidelines that are often recommended. However, the benefits of ECE have been shown to far outweigh the costs, and it is argued that supporting early learning is a sound investment: ‘Every $1 invested in early childhood care and education can lead to a return of as much as $17 for the most disadvantaged children’ (Zubairi and Rose, 2017).

Impact on learning

Quality ECE is an investment for the immediate health and well-being of young children and for subsequent learning and development. A large body of research shows that ECE programme participation has a positive impact on primary school readiness. In turn, school readiness is linked to learning, school completion, later skill development, and acquisition of academic competencies and non-academic success (UNICEF, 2019).

Fourth-grade primary school children in Brazil who had attended day care and/or kindergarten scored higher in mathematics, compared to students who had not attended ECE services. First-grade children who had attended kindergarten in rural Guizhou, China, had literacy and mathematics scores significantly better than other children (UNESCO, 2012a), while children in rural areas of Mozambique who enrolled in preschool were 24 per cent more likely to attend primary school and to show improved understanding and behaviour (Zubairi and Rose, 2017).

By improving school readiness, participation in pre-primary makes enrolment in the first grade of primary school more likely reduces delayed enrolment, dropout, and grade repetition, and increases completion and achievement (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006). Quality preschool programmes can also help children to develop resilience to cope with traumatic and stressful situations, such as conflict and other emergencies (UNICEF, 2019).

Equity and inclusion

Despite the evidence on the potential of ECE, children from poor and migrant families or those living in rural areas more often miss out or are enrolled in ECE of poorer quality than their more affluent or urban peers (UNESCO, 2015). Children living in the poorest households are less likely to receive support for early learning at home and up to 10 times less likely to attend ECE programmes (UNICEF, 2019), further widening the early learning gap.

According to the 2018 World Development Report, children from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to exhibit learning deficits years before they start school, leaving them ill-prepared for the demands of formal education. These gaps are important predictors of performance throughout school and into early adulthood: ‘poor developmental foundations and lower preschool skills mean disadvantaged children arrive at school late and unprepared to benefit fully from learning opportunities. As these children get older, it becomes harder and harder for them to break out of lower learning trajectories’ (World Bank, 2018: 80).

Quality ECE programmes have the potential to compensate for disadvantage. They can also increase equity by promoting multilingual education, gender equality, and opportunities for disabled children and children in emergency or precarious circumstances. Evidence shows that disadvantaged students make the most dramatic gains from such programmes (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006).

Quality ECE can mean early identification and remediation of impairments and can aid transition into mainstream schools (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006). Earlier inclusion of children with disabilities to learn and play alongside their peers in mainstream ECE programmes promotes transition into primary school, reduces stigma and isolation for the child and their parents, and has positive socio-emotional and academic benefits for students of all abilities.

Quality ECE programmes can contribute to addressing stereotypes, in particular those related to gender. While curricula may emphasize gender equality, the programmes often promote gender-specific expectations, with teaching materials strengthening gender-specific roles, game-playing conforming to stereotype, and, even more importantly, teachers frequently not treating boys and girls the same (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006). Well-designed ECE programmes based on gender-neutral curricula can challenge these stereotypes, provided that they are accompanied by changes in teacher attitudes and behaviour.

Ensuring free access to quality ECE programmes for minority and disadvantaged children is important. ECE programmes can contribute to the inclusion of families from minority backgrounds, provided that they are culturally relevant, delivered in the local language, and use resources that come from within the community. To improve the access of minority parents to existing ECE and parental support programmes, initiatives should be culturally sensitive to parents’ child-rearing beliefs and practices and should integrate local identities and knowledge (UNESCO, 2012b; Naudeau et al., 2011). ECE programmes can also help children develop their self-esteem by using their mother tongue while acquiring a second (and sometimes a third) language (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006).

Challenges and policy options

Improving early childhood teacher training and recognition.

Improvements in programme quality and child outcomes are often correlated with better-educated and trained teachers, though it is difficult to identify the optimal duration and combination of initial education and professional development. Training strategies that promote a continuum of practitioner development, beginning with pre-service and continuing with ongoing in-service training that is maintained throughout the careers of ECE professionals, can be developed (Garcia, Pence, and Evans, 2008). Teachers’ competences and standards can increase the relevance of training and professional development, enhance the quality of monitoring and mentoring opportunities, support the professionalization of the workforce, and support workforce planning efforts (Putcha, 2018).

Mainstreaming ECE in education sector plans

ECE appears in most education sector plans, but its inclusion is usually insufficient to address the development of the subsector (IIEP, GPE, UNICEF, 2019.). Mainstreaming ECE throughout the education planning process can help ensure the provision of universal public pre-primary education and improve its integration in the education system. Comparative studies show that universal services can yield significantly higher enrolment rates among poor families than policies that target specifically the poor, and therefore the former have greater equalizing potential (UNESCO, 2015). However, specific measures to foster the participation of the most disadvantaged can help ensure they are not left behind. Education sector planning provides a mechanism to strengthen the pre-primary subsector and enhance its ability to deliver equitable and quality ECE to all children: ‘Credible education sector plans that integrate pre-primary provide the basis by which governments can provide an overall vision for the pre-primary subsector and guide decision-makers and implementers in the process of delivery of ECE’ (IIEP, GPE, UNICEF, 2019: 15). They also support the mobilization of the domestic and external resources needed for the subsector to expand.

Increased and more-efficient funding

The provision of funding for pre-primary education should not be seen as a loss of support for other subsectors of education, but rather as a core strategy for strengthening the entire education system. Responding to this financial need requires greater pooling of resources through coordinated cross-sector committees represented by education, health, family welfare, and other ECE-related services (UNICEF, 2019). In addition to increasing funding, resources need to be targeted at those at risk of not learning. Decision-makers should prioritize the most disadvantaged and early years where social returns are highest while minimizing household spending on basic education by the poor (Education Commission, 2016)

Cooperation with other ministries and coordination of non-state providers

Quality early childhood development programmes that go beyond education and tackle all relevant issues promoting children’s holistic development require a coordinated approach across the education, health, nutrition, and social protection sectors, from a range of actors, both public and non-public. Community-based organizations, NGOs, religious groups, and for-profit entities can support government efforts to expand, improve, and coordinate ECE provision (Education Commission, 2016). To create links among different policy areas affecting the lives of young children, several governments have recently begun to elaborate national early childhood policies that cover health, nutrition, education, water, hygiene, sanitation, and legal protection for young children (Global Education Monitoring Report Team, 2006).

- Measuring Early Learning Quality and Outcomes (MELQO) (UNESCO, 2017). This initiative aims to promote feasible, accurate, and useful measurement of children’s development and learning at the start of primary school, and of the quality of their pre-primary learning environments.

- International Development and Early Learning Assessment (IDELA) (Save the Children, 2017). This tool measures children’s early learning and development. It provides a holistic picture of children’s development and learning covering motor development, emergent language and literacy, emergent numeracy/problem solving, and social-emotional skills.

- Holistic Early Childhood Development Index (HECDI) Framework (UNESCO, 2014). The HECDI Framework provides a set of targets, sub-targets, and indicators for the holistic monitoring of young children’s well-being at both the national and international levels.

- SABER-Early Childhood Development (World Bank, 2016). This tool allows policymakers to take stock and analyse existing early childhood development policies and programmes, identifying gaps and areas needing policy attention.

Education Commission. 2016. The learning generation: Investing in education for a changing world.

Global Education Monitoring Report Team. 2006. Strong foundations: Early childhood care and education. EFA global monitoring report, 2007. UNESCO: Paris, France.

Global Education Monitoring Report Team. 2020. Inclusion and education: All means all. Global education monitoring report, 2020 . Paris: UNESCO.

Garcia, M.; Pence, A.; Evans, J.L. 2008. Africa’s future, Africa’s challenge: Early childhood care and development in sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

IIEP, GPE, UNICEF. 2019. Mainstreaming early childhood education into education sector planning. Course reader for module 1: The rationale for investing in pre-primary.

Naudeau, S.; Kataoka, N.; Valerio, A.; Neuman, M.J.; Elder, L.K. 2011. Investing in young children: An early childhood development guide for policy dialogue and project preparation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Putcha, V. 2018. Strengthening and supporting the early childhood workforce: Competences and standards . Washington, DC: Results for Development.

UNESCO. 2012a. Expanding equitable early childhood care and education is an urgent need. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. 2012b. Indigenous early childhood care and education (IECCE) curriculum framework for Africa: A focus on contexts and contents. UNESCO/International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa: Addis Ababa.

UNESCO. 2015. Investing against evidence: The global state of early childhood care and education. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. 2016. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO. 2017. Overview: MELQO: Measuring early learning quality and outcomes. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2019. A world ready to learn: Prioritizing quality early childhood education. New York: UNICEF.

World Bank. 2018. World development report, 2018: Learning to realize education’s promise. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zubairi, A.; Rose, P. 2017. Bright and early: How financing pre-primary education gives every child a fair start in life . London: Theirworld.

Related information

- Early Childhood Workforce Initiative

- Center for Education Innovations Early Learning Toolkit

- Early childhood care and education

- Early childhood education

- Pre-primary education

- Primary education

The importance of education

Harvey Mackay

About this time every year, millions of people graduate from all levels of education, excited to begin the next chapter of their lives. Most are relieved to be finished with formal classroom learning and ready to put their newly minted knowledge to work.

News flash: Their education in the real world is just beginning.

We can't put enough of a premium on the importance of education. Education can help avoid the high price we pay for experience. It's the great teacher that helps us gain knowledge and avoid making the same mistake again and again.

The only thing more expensive than education is ignorance. I have always told my children and grandchildren, "Before you get to the three R's, you've got to master the three L's — look, listen and learn."

I believe education is a cornerstone for success, both personally and professionally. It's not just about formal schooling, but also about the continuous pursuit of knowledge and skills throughout one's life. Education equips us with the tools to think critically, solve problems and adapt to change.

As Nelson Mandela said, "Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world."

Education is an investment and never an expense. Consider education a capital improvement. Don't be ashamed to borrow wisely, particularly to replenish your professional inventory. In fact, self-improvement is the one area in which you should really increase your spending, not decrease it.

Self-education and lifelong learning are vital in personal and professional development. In today's fast-paced world, where industries and technologies are constantly evolving, the pursuit of knowledge cannot stop at graduation. Continuous learning is the key to staying relevant and competitive.

Self-education demonstrates a strong personal initiative and a commitment to personal excellence. It helps to stay adaptable and able to pivot in response to changes in your industry or career.

Lifelong learning is crucial for enhancing existing skills and acquiring new ones. It fosters innovation by exposing you to new ideas and perspectives.

In my experience, the most successful individuals are those who are curious and never stop learning. They read books, attend workshops, listen to podcasts, ask substantive, in-depth questions and engage in networking to exchange knowledge. This not only enriches their lives but also provides them with a competitive edge in their careers.

Benjamin Franklin was once asked to describe the most pitiful sight he had ever seen. Franklin said, "The person who deserves most pity is a lonesome one on a rainy day who does not know how to read."

One little-known benefit of education: Statistics indicate that educated people live longer. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the mortality rate of Americans aged 25 to 64 who had not completed their high school education was twice as high as those who had. Also, the mortality rate of those who continued their education after high school was 79% less than those who earned only a high school diploma.

In today's job market, it's important to have several skill sets. As companies evolve to keep current, managers look for people who can roll with the times. Be prepared to respond to changing job requirements as needs demand.

Education comes in so many forms beyond the classroom. Opportunities are unlimited if you just pay attention. I've hired people whose skills included being able to talk about fishing or art or cars with customers, even though that had nothing to with the envelopes they were buying. We aren't just in the envelope business, we're in the people business.

Nothing impresses me more as a potential employer than someone who is out of work but still actively attending school. What excuse is there for not pursuing education of some kind when you're not employed? It's the true test of your determination to get into the workplace, to present an up-to-the-minute, trainable, quality package to a potential employer.

If you are fired or downsized, it's a great way to prove to yourself and others that you're capable of bouncing back after a setback. It's a real confidence builder.

It's also the best single thing you can do for yourself.

A mother once asked Albert Einstein how to raise a child to become a genius. Einstein's advice was to read fairy tales to the child.

"And after that?" the mother asked.

"Read the child more fairy tales," Einstein replied, adding that what a scientist most needs is a curious imagination.

Mackay's Moral: Invest in your education, and it will pay dividends for the rest of your life.

Harvey Mackay is the author of the New York Times bestseller "Swim With the Sharks Without Being Eaten Alive." He can be reached through his website, www.harveymackay.com , by emailing [email protected] or by writing him at MackayMitchell Envelope Co., 2100 Elm St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414.

Share This Story

- Search UNH.edu

- Search Carsey School of Public Policy

Commonly Searched Items:

- Academic Calendar

- Masters Programs

- Accelerated Masters

- Executive Education

- Continuing Education

- Grad Certificate Programs

- Changemaker Collaborative

- Student Experience

- Online Experience

- Application Checklist: How to Apply

- Paying For School

- Schedule a Campus Visit

- Concentrations & Tools

- Publications

- Carsey Policy Hour

- Coffee & Conversations Archive

- Communications

- Working With Us

What Is Civic Education and Why Is It Important?

In the United States, civic education is often focused on knowledge of government. Students are taught the many structures of government and the procedures within those structures. Their understanding of civics is evaluated based on whether they can name the three branches of government, their representatives in Congress, and their state governor. By these measurements, the current state of civic education is lacking.

Only 56% of Americans can name all three branches of government, according to the 2021 Annenberg Civics Knowledge Survey , and that’s up from a mere 26% in 2016. A 2018 Johns Hopkins survey found that a third of Americans couldn’t name their governor and that 80% couldn’t name their state legislator, among other information about state government.

It’s tempting to say the meaning of civic education is to teach information about government. Students must be informed about the structures of their government to understand it. If they don’t know who their leaders are, it seems natural that they also don’t know what those leaders are doing.