- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety

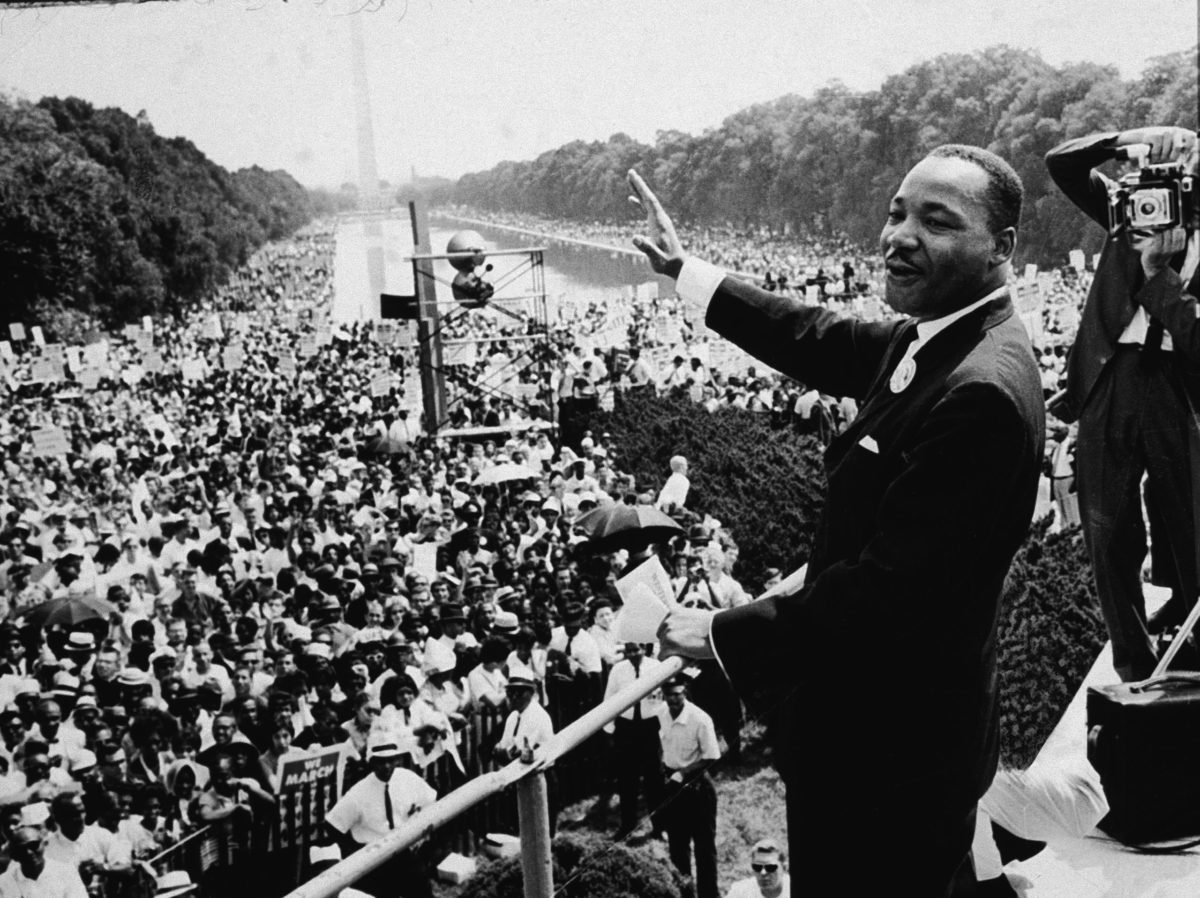

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington.

Monday marks Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Below is a transcript of his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. NPR's Talk of the Nation aired the speech in 2010 — listen to that broadcast at the audio link above.

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders gather before a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. National Archives/Hulton Archive via Getty Images hide caption

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

Code Switch

The power of martin luther king jr.'s anger.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

Martin Luther King is not your mascot

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

Civil rights protesters march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Kurt Severin/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

Throughline

Bayard rustin: the man behind the march on washington (2021).

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

How The Voting Rights Act Came To Be And How It's Changed

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

People clap and sing along to a freedom song between speeches at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Express Newspapers via Getty Images hide caption

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

Nikole Hannah-Jones on the power of collective memory

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

Correction Jan. 15, 2024

A previous version of this transcript included the line, "We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now." The correct wording is "We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now."

The 1963 March on Washington

A quarter million people and a dream.

On August 28, 1963, more than a quarter million people participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, gathering near the Lincoln Memorial.

More than 3,000 members of the press covered this historic march, where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the exalted "I Have a Dream" speech.

Originally conceived by renowned labor leader A. Phillip Randolph and Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, the March on Washington evolved into a collaborative effort amongst major civil rights groups and icons of the day.

Stemming from a rapidly growing tide of grassroots support and outrage over the nation's racial inequities, the rally drew over 260,000 people from across the nation.

Celebrated as one of the greatest — if not the greatest — speech of the 20th century, Dr. King's celebrated speech, "I Have a Dream," was carried live by television stations across the country. You can read the full speech and watch a short film, below.

A March 20 Years in the Making

In 1941, A. Phillip Randolph first conceptualized a "march for jobs" in protest of the racial discrimination against African Americans from jobs created by WWII and the New Deal programs created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The march was stalled, however, after negotiations between Roosevelt and Randolph prompted the establishment of the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) and an executive order banning discrimination in defense industries.

The FEPC dissolved just five years later, causing Randolph to revive his plans. He looked to the charismatic Dr. King to breathe new life into the march.

NAACP and SCLC Center the March on Civil Rights

By the late 1950s, Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) were also planning to march on Washington, this time to march for freedom.

As the years passed on, the Civil Rights Act was still stalled in Congress, and equality for Americans of color still seemed like a far-fetched dream.

Randolph, his chief aide, Bayard Rustin, and Dr. King all decided it would be best to combine the two causes into one mega-march, the March for Jobs and Freedom.

NAACP, headed by Roy Wilkins, was called upon to be one of the leaders of the march.

As one of the largest and most influential civil rights groups at the time, our organization harnessed the collective power of its members, organizing a march that was focused on the advancement of civil rights and the actualization of Dr. King's dream.

The Big Six

A quarter-million people strong, the march drew activists from far and wide.

Leaders of the six prominent civil rights groups at the time joined forces in organizing the march.

The group included Randolph, leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP; Dr. King, Chairman of the SCLC; James Farmer, founder of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); John Lewis, President of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); and Whitney Young, Executive Director of the National Urban League.

Dr. King, originally slated to speak for 4 minutes, went on to speak for 16 minutes, giving one of the most iconic speeches in history.

"I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood." – I Have a Dream, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

It didn't take long for King's dream to come to fruition — the legislative aspect of the dream, that is.

After a decade of continued lobbying of Congress and the President led by the NAACP, plus other peaceful protests for civil rights, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One year later, he signed the National Voting Rights Act of 1965 .

Together, these laws outlawed discrimination against blacks and women, effectively ending segregation, and sought to end disenfranchisement by making discriminatory voting practices illegal.

Ten years after King joined the civil rights fight, the campaign to secure the enactment of the 1964 Civil Rights Act had achieved its goal – to ensure that black citizens would have the power to represent themselves in government.

2020 March on Washington

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered this iconic 'I Have a Dream' speech at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. See entire text of King's speech below.

I Have a Dream

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

So we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was the promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds."

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we have come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now.

This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy; now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice; now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood; now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.

This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content, will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the worn threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy, which has engulfed the Negro community, must not lead us to a distrust of all white people. For many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of Civil Rights, "When will you be satisfied?"

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality; we can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities; we cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one; we can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating "For Whites Only"; we cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote, and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No! no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until "justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.

You have been the veterans of creative suffering.

Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi. Go back to Alabama. Go back to South Carolina. Go back to Georgia. Go back to Louisiana. Go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama — with its vicious racists, with its Governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification — one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low. The rough places will be plain and the crooked places will be made straight, "and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together."

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.

With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brother-hood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning, "My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my father died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring." And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire; let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York; let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania; let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado; let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that.

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia; let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee; let freedom ring from every hill and mole hill of Mississippi. "From every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

"Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last."

Source: Martin Luther King, Jr., I Have A Dream: Writings and Speeches that Changed the World (San Francisco: Harper, 1986) via Teaching America History.

Meet other heroes who advanced racial justice

The voices of these visionaries shape our present and inform our future.

Join the fight

You are critical to the hard, complex work of ending racial inequality.

Give Monthly To Keep Advancing

You can become a Champion for Change and receive a t-shirt with your monthly gift of $19 a month or more right now.

Make a Difference - Donate

"I Have a Dream"

August 28, 1963

Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom , synthesized portions of his previous sermons and speeches, with selected statements by other prominent public figures.

King had been drawing on material he used in the “I Have a Dream” speech in his other speeches and sermons for many years. The finale of King’s April 1957 address, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” envisioned a “new world,” quoted the song “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” and proclaimed that he had heard “a powerful orator say not so long ago, that … Freedom must ring from every mountain side…. Yes, let it ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado…. Let it ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let it ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let it ring from every mountain and hill of Alabama. From every mountain side, let freedom ring” ( Papers 4:178–179 ).

In King’s 1959 sermon “Unfulfilled Hopes,” he describes the life of the apostle Paul as one of “unfulfilled hopes and shattered dreams” ( Papers 6:360 ). He notes that suffering as intense as Paul’s “might make you stronger and bring you closer to the Almighty God,” alluding to a concept he later summarized in “I Have a Dream”: “unearned suffering is redemptive” ( Papers 6:366 ; King, “I Have a Dream,” 84).

In September 1960, King began giving speeches referring directly to the American Dream. In a speech given that month at a conference of the North Carolina branches of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , King referred to the unexecuted clauses of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution and spoke of America as “a dream yet unfulfilled” ( Papers 5:508 ). He advised the crowd that “we must be sure that our struggle is conducted on the highest level of dignity and discipline” and reminded them not to “drink the poisonous wine of hate,” but to use the “way of nonviolence” when taking “direct action” against oppression ( Papers 5:510 ).

King continued to give versions of this speech throughout 1961 and 1962, then calling it “The American Dream.” Two months before the March on Washington, King stood before a throng of 150,000 people at Cobo Hall in Detroit to expound upon making “the American Dream a reality” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 70). King repeatedly exclaimed, “I have a dream this afternoon” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 71). He articulated the words of the prophets Amos and Isaiah, declaring that “justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream,” for “every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 72). As he had done numerous times in the previous two years, King concluded his message imagining the day “when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing with the Negroes in the spiritual of old: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” (King, Address at Freedom Rally , 73).

As King and his advisors prepared his speech for the conclusion of the 1963 march, he solicited suggestions for the text. Clarence Jones offered a metaphor for the unfulfilled promise of constitutional rights for African Americans, which King incorporated into the final text: “America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned” (King, “I Have a Dream,” 82). Several other drafts and suggestions were posed. References to Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation were sustained throughout the countless revisions. King recalled that he did not finish the complete text of the speech until 3:30 A.M. on the morning of 28 August.

Later that day, King stood at the podium overlooking the gathering. Although a typescript version of the speech was made available to the press on the morning of the march, King did not merely read his prepared remarks. He later recalled: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point … the audience response was wonderful that day…. And all of a sudden this thing came to me that … I’d used many times before.... ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here … I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it” (King, 29 November 1963).

The following day in the New York Times, James Reston wrote: “Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile” (Reston, “‘I Have a Dream …’”).

Carey to King, 7 June 1955, in Papers 2:560–561.

Hansen, The Dream, 2003.

King, Address at the Freedom Rally in Cobo Hall, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, “I Have a Dream,” Address Delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, Interview by Donald H. Smith, 29 November 1963, DHSTR-WHi .

King, “The Negro and the American Dream,” Excerpt from Address at the Annual Freedom Mass Meeting of the North Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP, 25 September 1960, in Papers 5:508–511.

King, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” Address Delivered at St. Louis Freedom Rally, 10 April 1957, in Papers 4:167–179.

King, Unfulfilled Hopes, 5 April 1959, in Papers 6:359–367.

James Reston, “‘I Have a Dream…’: Peroration by Dr. King Sums Up a Day the Capital Will Remember,” New York Times , 29 August 1963.

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech in Its Entirety

Speech by the Rev. Martin Luther King at the “March on Washington” on August 28, 1963:

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree is a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later the life of the Negro is still badly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men‚ would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children. It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality—1963 is not an end but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright days of justice emerge.

And that is something that I must say to my people who stand on the worn threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

They have come to realized that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children ar stripped of their adulthood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating “For Whiles Only.”

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and the Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulation. Some of you come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering.

Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, though, even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream…I have a dream that one day in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today…I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low. The rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight. And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning. “My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountain side, let freedom ring.” And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that. Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia,. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi, from every mountain side. Let freedom ring…

When we allow freedom to ring‚when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-mighty, We are free at last.”

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 28, 1963 ce: martin luther king jr. gives "i have a dream" speech.

On August 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington, a large gathering of civil rights protesters in Washington, D.C., United States.

Social Studies, Civics, U.S. History

Loading ...

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., took the podium at the March on Washington and addressed the gathered crowd, which numbered 200,000 people or more. His speech became famous for its recurring phrase “I have a dream.” He imagined a future in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners" could "sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” a future in which his four children are judged not "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." King's moving speech became a central part of his legacy. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, in 1929. Like his father and grandfather, King studied theology and became a Baptist pastor . In 1957, he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ( SCLC ), which became a leading civil rights organization. Under King's leadership, the SCLC promoted nonviolent resistance to segregation, often in the form of marches and boycotts. In his campaign for racial equality, King gave hundreds of speeches, and was arrested more than 20 times. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his "nonviolent struggle for civil rights ." On April 4, 1968, King was shot and killed while standing on a balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 4, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : August 28

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Martin Luther King Jr. delivers “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. , the African American civil rights movement reaches its high-water mark when Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his " I Have a Dream " speech to about 250,000 people attending the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The demonstrators—Black and white, poor and rich—came together in the nation’s capital to demand voting rights and equal opportunity for African Americans and to appeal for an end to racial segregation and discrimination.

The peaceful rally was the largest assembly for a redress of grievances that the capital had ever seen, and King was the last speaker. With the statue of Abraham Lincoln —the Great Emancipator—towering behind him, King used the rhetorical talents he had developed as a Baptist preacher to show how, as he put it, the “Negro is still not free.” He told of the struggle ahead, stressing the importance of continued action and nonviolent protest. Coming to the end of his prepared text (which, like other speakers that day, he had limited to seven minutes), he was overwhelmed by the moment and launched into an improvised sermon.

He told the hushed crowd, “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia , go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.” Continuing, he began the refrain that made the speech one of the best known in U.S. history, second only to Lincoln’s 1863 “Gettysburg Address” :

“I have a dream,” he boomed over the crowd stretching from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument , “that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’ I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.”

King had used the “I have a dream” theme before, in a handful of stump speeches, but never with the force and effectiveness of that hot August day in Washington. He equated the civil rights movement with the highest and noblest ideals of the American tradition, allowing many to see for the first time the importance and urgency of racial equality. He ended his stirring, 16-minute speech with his vision of the fruit of racial harmony:

“When we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!'”

In the year after the March on Washington, the civil rights movement achieved two of its greatest successes: the ratification of the 24th Amendment to the Constitution , which abolished the poll tax and thus a barrier to poor African American voters in the South; and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 , which prohibited racial discrimination in employment and education and outlawed racial segregation in public facilities. In October 1964, Martin Luther King Jr., was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. On April 4, 1968, he was shot to death while standing on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee—he was 39 years old. The gunman was escaped convict James Earl Ray .

Same Date, 8 Years Apart: From Emmett Till’s Murder to ‘I Have a Dream,’ in Photos

Eight years to the day after Till’s death, some 250,000 people gathered in the nation’s capital for the iconic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

John Lewis – Civil Rights Leader

Inspired by Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis joined the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. Lewis was a Freedom Rider, spoke at 1963’s March on Washington and led the demonstration that became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Quotes from 7 of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Most Notable Speeches

From 'I Have a Dream' to 'Beyond Vietnam,' revisit the words and messages of the legendary civil rights leader.

Also on This Day in History August | 28

Britney Spears and Madonna kiss at the VMAs

Hiv‑positive ray brothers' home burned down.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on August 28

Protests at democratic national convention in chicago.

Emmett Till is murdered

Zulu king captured.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Charles and Diana divorce

Mass slaughter in ukraine, president woodrow wilson picketed by women suffragists, three leave powell’s grand canyon expedition, mahalia jackson prompts martin luther king jr. to improvise "i have a dream" speech, air‑show accident burns spectators, murdered students are discovered at the university of florida, "red scare" dominates american political news, st. elizabeth born in new york city.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

I Have a Dream, speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., that was delivered on August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington. A call for equality and freedom, it became one of the defining moments of the civil rights movement and one of the most iconic speeches in American history. March on Washington Civil rights supporters at the March on ...

AFP via Getty Images. Monday marks Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Below is a transcript of his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial ...

I Have a Dream. delivered 28 August 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington D.C. ... the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at ...

I Have a Dream, August 28, 1963; 61 years ago (August 28, 1963) , Educational Radio Network [1] " I Have a Dream " is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister [2] Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called for civil ...

The “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. before a crowd of some 250,000 people at the 1963 March on Washington, remains one of the most famous speeches in history.

On August 28, 1963, more than a quarter million people participated in the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, gathering near the Lincoln Memorial. More than 3,000 members of the press covered this historic march, where Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the exalted "I Have a Dream" speech.

August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, synthesized portions of his previous sermons and speeches, with selected statements by other prominent public figures. King had been drawing on material he used in the “I Have a Dream” speech ...

Speech by the Rev. Martin Luther King at the “March on Washington” on August 28, 1963: I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., took the podium at the March on Washington and addressed the gathered crowd, which numbered 200,000 people or more. His speech became famous for its recurring phrase “I have a dream.”. He imagined a future in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners" could "sit down ...

On the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the African American civil rights movement reaches its high-water mark when Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his "I Have a Dream" speech to ...