Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on October 26, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

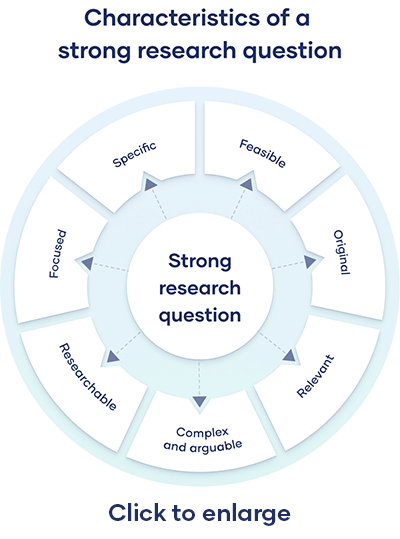

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, using sub-questions to strengthen your main research question, research questions quiz, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

| Research question formulations | |

|---|---|

| Describing and exploring | |

| Explaining and testing | |

| Evaluating and acting | is X |

Using your research problem to develop your research question

| Example research problem | Example research question(s) |

|---|---|

| Teachers at the school do not have the skills to recognize or properly guide gifted children in the classroom. | What practical techniques can teachers use to better identify and guide gifted children? |

| Young people increasingly engage in the “gig economy,” rather than traditional full-time employment. However, it is unclear why they choose to do so. | What are the main factors influencing young people’s decisions to engage in the gig economy? |

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Focused on a single topic | Your central research question should work together with your research problem to keep your work focused. If you have multiple questions, they should all clearly tie back to your central aim. |

| Answerable using | Your question must be answerable using and/or , or by reading scholarly sources on the to develop your argument. If such data is impossible to access, you likely need to rethink your question. |

| Not based on value judgements | Avoid subjective words like , , and . These do not give clear criteria for answering the question. |

Feasible and specific

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Answerable within practical constraints | Make sure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific. |

| Uses specific, well-defined concepts | All the terms you use in the research question should have clear meanings. Avoid vague language, jargon, and too-broad ideas. |

| Does not demand a conclusive solution, policy, or course of action | Research is about informing, not instructing. Even if your project is focused on a practical problem, it should aim to improve understanding rather than demand a ready-made solution. If ready-made solutions are necessary, consider conducting instead. Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as it is solved. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. |

Complex and arguable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cannot be answered with or | Closed-ended, / questions are too simple to work as good research questions—they don’t provide enough for robust investigation and discussion. |

| Cannot be answered with easily-found facts | If you can answer the question through a single Google search, book, or article, it is probably not complex enough. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation prior to providing an answer. |

Relevant and original

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Addresses a relevant problem | Your research question should be developed based on initial reading around your . It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline. |

| Contributes to a timely social or academic debate | The question should aim to contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on. |

| Has not already been answered | You don’t have to ask something that nobody has ever thought of before, but your question should have some aspect of originality. For example, you can focus on a specific location, or explore a new angle. |

Chances are that your main research question likely can’t be answered all at once. That’s why sub-questions are important: they allow you to answer your main question in a step-by-step manner.

Good sub-questions should be:

- Less complex than the main question

- Focused only on 1 type of research

- Presented in a logical order

Here are a few examples of descriptive and framing questions:

- Descriptive: According to current government arguments, how should a European bank tax be implemented?

- Descriptive: Which countries have a bank tax/levy on financial transactions?

- Framing: How should a bank tax/levy on financial transactions look at a European level?

Keep in mind that sub-questions are by no means mandatory. They should only be asked if you need the findings to answer your main question. If your main question is simple enough to stand on its own, it’s okay to skip the sub-question part. As a rule of thumb, the more complex your subject, the more sub-questions you’ll need.

Try to limit yourself to 4 or 5 sub-questions, maximum. If you feel you need more than this, it may be indication that your main research question is not sufficiently specific. In this case, it’s is better to revisit your problem statement and try to tighten your main question up.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (“ x affects y because …”).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses . In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, 10 research question examples to guide your research project, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Module 1: Research and the Writing Process

Steps in developing a research proposal, learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content”.) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?”.) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2”, write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3”. Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

- Successful Writing Section 11.2, Steps in Developing a Research Proposal. Authored by : Anonymous. Located at : http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/successful-writing/s15-02-steps-in-developing-a-research.html . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

PHILO-notes

Free Online Learning Materials

How to Write the Background of the Study in Research (Part 1)

Background of the Study in Research: Definition and the Core Elements it Contains

Before we embark on a detailed discussion on how to write the background of the study of your proposed research or thesis, it is important to first discuss its meaning and the core elements that it should contain. This is obviously because understanding the nature of the background of the study in research and knowing exactly what to include in it allow us to have both greater control and clear direction of the writing process.

So, what really is the background of the study and what are the core elements that it should contain?

The background of the study, which usually forms the first section of the introduction to a research paper or thesis, provides the overview of the study. In other words, it is that section of the research paper or thesis that establishes the context of the study. Its main function is to explain why the proposed research is important and essential to understanding the main aspects of the study.

The background of the study, therefore, is the section of the research paper or thesis that identifies the problem or gap of the study that needs to addressed and justifies the need for conducting the study. It also articulates the main goal of the study and the thesis statement, that is, the main claim or argument of the paper.

Given this brief understanding of the background of the study, we can anticipate what readers or thesis committee members expect from it. As we can see, the background of the study should contain the following major points:

1) brief discussion on what is known about the topic under investigation; 2) An articulation of the research gap or problem that needs to be addressed; 3) What the researcher would like to do or aim to achieve in the study ( research goal); 4) The thesis statement, that is, the main argument or contention of the paper (which also serves as the reason why the researcher would want to pursue the study); 5) The major significance or contribution of the study to a particular discipline; and 6) Depending on the nature of the study, an articulation of the hypothesis of the study.

Thus, when writing the background of the study, you should plan and structure it based on the major points just mentioned. With this, you will have a clear picture of the flow of the tasks that need to be completed in writing this section of your research or thesis proposal.

Now, how do you go about writing the background of the study in your proposed research or thesis?

The next lessons will address this question.

How to Write the Opening Paragraphs of the Background of the Study?

To begin with, let us assume that you already have conducted a preliminary research on your chosen topic, that is, you already have read a lot of literature and gathered relevant information for writing the background of your study. Let us also assume that you already have identified the gap of your proposed research and have already developed the research questions and thesis statement. If you have not yet identified the gap in your proposed research, you might as well go back to our lesson on how to identify a research gap.

So, we will just put together everything that you have researched into a background of the study (assuming, again, that you already have the necessary information). But in this lesson, let’s just focus on writing the opening paragraphs.

It is important to note at this point that there are different styles of writing the background of the study. Hence, what I will be sharing with you here is not just “the” only way of writing the background of the study. As a matter of fact, there is no “one-size-fits-all” style of writing this part of the research or thesis. At the end of the day, you are free to develop your own. However, whatever style it would be, it always starts with a plan which structures the writing process into stages or steps. The steps that I will share with below are just some of the most effective ways of writing the background of the study in research.

So, let’s begin.

It is always a good idea to begin the background of your study by giving an overview of your research topic. This may include providing a definition of the key concepts of your research or highlighting the main developments of the research topic.

Let us suppose that the topic of your study is the “lived experiences of students with mathematical anxiety”.

Here, you may start the background of your study with a discussion on the meaning, nature, and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety”. The reason for this is too obvious: “mathematical anxiety” is a highly technical term that is specific to mathematics. Hence, this term is not readily understandable to non-specialists in this field.

So, you may write the opening paragraph of your background of the study with this:

“Mathematical anxiety refers to the individual’s unpleasant emotional mood responses when confronted with a mathematical situation.”

Since you do not invent the definition of the term “mathematical anxiety”, then you need to provide a citation to the source of the material from which you are quoting. For example, you may now say:

“Mathematical anxiety refers to the individual’s unpleasant emotional mood responses when confronted with a mathematical situation (Eliot, 2020).”

And then you may proceed with the discussion on the nature and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety”. You may say:

“Lou (2019) specifically identifies some of the manifestations of this type of anxiety, which include, but not limited to, depression, helplessness, nervousness and fearfulness in doing mathematical and numerical tasks.”

After explaining to your readers the meaning, nature, and dynamics (as well as some historical development if you wish to) of the term “mathematical anxiety”, you may now proceed to showing the problem or gap of the study. As you may already know, the research gap is the problem that needs to be addressed in the study. This is important because no research activity is possible without the research gap.

Let us suppose that your research problem or gap is: “Mathematical anxiety can negatively affect not just the academic achievement of the students but also their future career plans and total well-being. Also, there are no known studies that deal with the mathematical anxiety of junior high school students in New Zealand.” With this, you may say:

“If left unchecked, as Shapiro (2019) claims, this problem will expand and create a total avoidance pattern on the part of the students, which can be expressed most visibly in the form of cutting classes and habitual absenteeism. As we can see, this will negatively affect the performance of students in mathematics. In fact, the study conducted by Luttenberger and Wimmer (2018) revealed that the outcomes of mathematical anxiety do not only negatively affect the students’ performance in math-related situations but also their future career as professionals. Without a doubt, therefore, mathematical anxiety is a recurring problem for many individuals which will negatively affect the academic success and future career of the student.”

Now that you already have both explained the meaning, nature, and dynamics of the term “mathematical anxiety” and articulated the gap of your proposed research, you may now state the main goal of your study. You may say:

“Hence, it is precisely in this context that the researcher aims to determine the lived experiences of those students with mathematical anxiety. In particular, this proposed thesis aims to determine the lived experiences of the junior high school students in New Zealand and identify the factors that caused them to become disinterested in mathematics.”

Please note that you should not end the first paragraph of your background of the study with the articulation of the research goal. You also need to articulate the “thesis statement”, which usually comes after the research goal. As is well known, the thesis statement is the statement of your argument or contention in the study. It is more of a personal argument or claim of the researcher, which specifically highlights the possible contribution of the study. For example, you may say:

“The researcher argues that there is a need to determine the lived experiences of these students with mathematical anxiety because knowing and understanding the difficulties and challenges that they have encountered will put the researcher in the best position to offer some alternatives to the problem. Indeed, it is only when we have performed some kind of a ‘diagnosis’ that we can offer practicable solutions to the problem. And in the case of the junior high school students in New Zealand who are having mathematical anxiety, determining their lived experiences as well as identifying the factors that caused them to become disinterested in mathematics are the very first steps in addressing the problem.”

If we combine the bits and pieces that we have written above, we can now come up with the opening paragraphs of your background of the study, which reads:

As we can see, we can find in the first paragraph 5 essential elements that must be articulated in the background of the study, namely:

1) A brief discussion on what is known about the topic under investigation; 2) An articulation of the research gap or problem that needs to be addressed; 3) What the researcher would like to do or aim to achieve in the study (research goal); 4) The thesis statement , that is, the main argument or claim of the paper; and 5) The major significance or contribution of the study to a particular discipline. So, that’s how you write the opening paragraphs of your background of the study. The next lesson will talk about writing the body of the background of the study.

How to Write the Body of the Background of the Study?

If we liken the background of the study to a sitting cat, then the opening paragraphs that we have completed in the previous lesson would just represent the head of the cat.

This means we still have to write the body (body of the cat) and the conclusion (tail). But how do we write the body of the background of the study? What should be its content?

Truly, this is one of the most difficult challenges that fledgling scholars faced. Because they are inexperienced researchers and didn’t know what to do next, they just wrote whatever they wished to write. Fortunately, this is relatively easy if they know the technique.

One of the best ways to write the body of the background of the study is to attack it from the vantage point of the research gap. If you recall, when we articulated the research gap in the opening paragraphs, we made a bold claim there, that is, there are junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety. Now, you have to remember that a “statement” remains an assumption until you can provide concrete proofs to it. This is what we call the “epistemological” aspect of research. As we may already know, epistemology is a specific branch of philosophy that deals with the validity of knowledge. And to validate knowledge is to provide concrete proofs to our statements. Hence, the reason why we need to provide proofs to our claim that there are indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety is the obvious fact that if there are none, then we cannot proceed with our study. We have no one to interview with in the first. In short, we don’t have respondents.

The body of the background of the study, therefore, should be a presentation and articulation of the proofs to our claim that indeed there are junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety. Please note, however, that this idea is true only if you follow the style of writing the background of the study that I introduced in this course.

So, how do we do this?

One of the best ways to do this is to look for literature on mathematical anxiety among junior high school students in New Zealand and cite them here. However, if there are not enough literature on this topic in New Zealand, then we need to conduct initial interviews with these students or make actual classroom observations and record instances of mathematical anxiety among these students. But it is always a good idea if we combine literature review with interviews and actual observations.

Assuming you already have the data, then you may now proceed with the writing of the body of your background of the study. For example, you may say:

“According to records and based on the researcher’s firsthand experience with students in some junior high schools in New Zealand, indeed, there are students who lost interest in mathematics. For one, while checking the daily attendance and monitoring of the students, it was observed that some of them are not always attending classes in mathematics but are regularly attending the rest of the required subjects.”

After this sentence, you may insert some literature that will support this position. For example, you may say:

“As a matter of fact, this phenomenon is also observed in the work of Estonanto. In his study titled ‘Impact of Math Anxiety on Academic Performance in Pre-Calculus of Senior High School’, Estonanto (2019) found out that, inter alia, students with mathematical anxiety have the tendency to intentionally prioritize other subjects and commit habitual tardiness and absences.”

Then you may proceed saying:

“With this initial knowledge in mind, the researcher conducted initial interviews with some of these students. The researcher learned that one student did not regularly attend his math subject because he believed that he is not good in math and no matter how he listens to the topic he will not learn.”

Then you may say:

“Another student also mentioned that she was influenced by her friends’ perception that mathematics is hard; hence, she avoids the subject. Indeed, these are concrete proofs that there are some junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. As already hinted, “disinterest” or the loss of interest in mathematics is one of the manifestations of a mathematical anxiety.”

If we combine what we have just written above, then we can have the first two paragraphs of the body of our background of the study. It reads:

“According to records and based on the researcher’s firsthand experience with students in some junior high schools in New Zealand, indeed there are students who lost interest in mathematics. For one, while checking the daily attendance and monitoring of the students, it was observed that some of them are not always attending classes in mathematics but are regularly attending the rest of the required subjects. As a matter of fact, this phenomenon is also observed in the work of Estonanto. In his study titled ‘Impact of Math Anxiety on Academic Performance in Pre-Calculus of Senior High School’, Estonanto (2019) found out that, inter alia, students with mathematical anxiety have the tendency to intentionally prioritize other subjects and commit habitual tardiness and absences.

With this initial knowledge in mind, the researcher conducted initial interviews with some of these students. The researcher learned that one student did not regularly attend his math subject because he believed that he is not good in math and no matter how he listens to the topic he will not learn. Another student also mentioned that she was influenced by her friends’ perception that mathematics is hard; hence, she avoids the subject. Indeed, these are concrete proofs that there are some junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. As already hinted, “disinterest” or the loss of interest in mathematics is one of the manifestations of a mathematical anxiety.”

And then you need validate this observation by conducting another round of interview and observation in other schools. So, you may continue writing the body of the background of the study with this:

“To validate the information gathered from the initial interviews and observations, the researcher conducted another round of interview and observation with other junior high school students in New Zealand.”

“On the one hand, the researcher found out that during mathematics time some students felt uneasy; in fact, they showed a feeling of being tensed or anxious while working with numbers and mathematical problems. Some were even afraid to seat in front, while some students at the back were secretly playing with their mobile phones. These students also show remarkable apprehension during board works like trembling hands, nervous laughter, and the like.”

Then provide some literature that will support your position. You may say:

“As Finlayson (2017) corroborates, emotional symptoms of mathematical anxiety involve feeling of helplessness, lack of confidence, and being nervous for being put on the spot. It must be noted that these occasionally extreme emotional reactions are not triggered by provocative procedures. As a matter of fact, there are no personally sensitive questions or intentional manipulations of stress. The teacher simply asked a very simple question, like identifying the parts of a circle. Certainly, this observation also conforms with the study of Ashcraft (2016) when he mentions that students with mathematical anxiety show a negative attitude towards math and hold self-perceptions about their mathematical abilities.”

And then you proceed:

“On the other hand, when the class had their other subjects, the students show a feeling of excitement. They even hurried to seat in front and attentively participating in the class discussion without hesitation and without the feeling of being tensed or anxious. For sure, this is another concrete proof that there are junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety.”

To further prove the point that there indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety, you may solicit observations from other math teachers. For instance, you may say:

“The researcher further verified if the problem is also happening in other sections and whether other mathematics teachers experienced the same observation that the researcher had. This validation or verification is important in establishing credibility of the claim (Buchbinder, 2016) and ensuring reliability and validity of the assertion (Morse et al., 2002). In this regard, the researcher attempted to open up the issue of math anxiety during the Departmentalized Learning Action Cell (LAC), a group discussion of educators per quarter, with the objective of ‘Teaching Strategies to Develop Critical Thinking of the Students’. During the session, one teacher corroborates the researcher’s observation that there are indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who have mathematical anxiety. The teacher pointed out that truly there were students who showed no extra effort in mathematics class in addition to the fact that some students really avoided the subject. In addition, another math teacher expressed her frustrations about these students who have mathematical anxiety. She quipped: “How can a teacher develop the critical thinking skills or ability of the students if in the first place these students show avoidance and disinterest in the subject?’.”

Again, if we combine what we have just written above, then we can now have the remaining parts of the body of the background of the study. It reads:

So, that’s how we write the body of the background of the study in research . Of course, you may add any relevant points which you think might amplify your content. What is important at this point is that you now have a clear idea of how to write the body of the background of the study.

How to Write the Concluding Part of the Background of the Study?

Since we have already completed the body of our background of the study in the previous lesson, we may now write the concluding paragraph (the tail of the cat). This is important because one of the rules of thumb in writing is that we always put a close to what we have started.

It is important to note that the conclusion of the background of the study is just a rehashing of the research gap and main goal of the study stated in the introductory paragraph, but framed differently. The purpose of this is just to emphasize, after presenting the justifications, what the study aims to attain and why it wants to do it. The conclusion, therefore, will look just like this:

“Given the above discussion, it is evident that there are indeed junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing mathematical anxiety. And as we can see, mathematical anxiety can negatively affect not just the academic achievement of the students but also their future career plans and total well-being. Again, it is for this reason that the researcher attempts to determine the lived experiences of those junior high school students in New Zealand who are experiencing a mathematical anxiety.”

If we combine all that we have written from the very beginning, the entire background of the study would now read:

If we analyze the background of the study that we have just completed, we can observe that in addition to the important elements that it should contain, it has also addressed other important elements that readers or thesis committee members expect from it.

On the one hand, it provides the researcher with a clear direction in the conduct of the study. As we can see, the background of the study that we have just completed enables us to move in the right direction with a strong focus as it has set clear goals and the reasons why we want to do it. Indeed, we now exactly know what to do next and how to write the rest of the research paper or thesis.

On the other hand, most researchers start their research with scattered ideas and usually get stuck with how to proceed further. But with a well-written background of the study, just as the one above, we have decluttered and organized our thoughts. We have also become aware of what have and have not been done in our area of study, as well as what we can significantly contribute in the already existing body of knowledge in this area of study.

Please note, however, as I already mentioned previously, that the model that I have just presented is only one of the many models available in textbooks and other sources. You are, of course, free to choose your own style of writing the background of the study. You may also consult your thesis supervisor for some guidance on how to attack the writing of your background of the study.

Lastly, and as you may already know, universities around the world have their own thesis formats. Hence, you should follow your university’s rules on the format and style in writing your research or thesis. What is important is that with the lessons that you learned in this course, you can now easily write the introductory part of your thesis, such as the background of the study.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.23(2); 2008 Apr

How to prepare a Research Proposal

Health research, medical education and clinical practice form the three pillars of modern day medical practice. As one authority rightly put it: ‘Health research is not a luxury, but an essential need that no nation can afford to ignore’. Health research can and should be pursued by a broad range of people. Even if they do not conduct research themselves, they need to grasp the principles of the scientific method to understand the value and limitations of science and to be able to assess and evaluate results of research before applying them. This review paper aims to highlight the essential concepts to the students and beginning researchers and sensitize and motivate the readers to access the vast literature available on research methodologies.

Most students and beginning researchers do not fully understand what a research proposal means, nor do they understand its importance. 1 A research proposal is a detailed description of a proposed study designed to investigate a given problem. 2

A research proposal is intended to convince others that you have a worthwhile research project and that you have the competence and the work-plan to complete it. Broadly the research proposal must address the following questions regardless of your research area and the methodology you choose: What you plan to accomplish, why do you want to do it and how are you going to do it. 1 The aim of this article is to highlight the essential concepts and not to provide extensive details about this topic.

The elements of a research proposal are highlighted below:

1. Title: It should be concise and descriptive. It must be informative and catchy. An effective title not only prick’s the readers interest, but also predisposes him/her favorably towards the proposal. Often titles are stated in terms of a functional relationship, because such titles clearly indicate the independent and dependent variables. 1 The title may need to be revised after completion of writing of the protocol to reflect more closely the sense of the study. 3

2. Abstract: It is a brief summary of approximately 300 words. It should include the main research question, the rationale for the study, the hypothesis (if any) and the method. Descriptions of the method may include the design, procedures, the sample and any instruments that will be used. 1 It should stand on its own, and not refer the reader to points in the project description. 3

3. Introduction: The introduction provides the readers with the background information. Its purpose is to establish a framework for the research, so that readers can understand how it relates to other research. 4 It should answer the question of why the research needs to be done and what will be its relevance. It puts the proposal in context. 3

The introduction typically begins with a statement of the research problem in precise and clear terms. 1

The importance of the statement of the research problem 5 : The statement of the problem is the essential basis for the construction of a research proposal (research objectives, hypotheses, methodology, work plan and budget etc). It is an integral part of selecting a research topic. It will guide and put into sharper focus the research design being considered for solving the problem. It allows the investigator to describe the problem systematically, to reflect on its importance, its priority in the country and region and to point out why the proposed research on the problem should be undertaken. It also facilitates peer review of the research proposal by the funding agencies.

Then it is necessary to provide the context and set the stage for the research question in such a way as to show its necessity and importance. 1 This step is necessary for the investigators to familiarize themselves with existing knowledge about the research problem and to find out whether or not others have investigated the same or similar problems. This step is accomplished by a thorough and critical review of the literature and by personal communication with experts. 5 It helps further understanding of the problem proposed for research and may lead to refining the statement of the problem, to identify the study variables and conceptualize their relationships, and in formulation and selection of a research hypothesis. 5 It ensures that you are not "re-inventing the wheel" and demonstrates your understanding of the research problem. It gives due credit to those who have laid the groundwork for your proposed research. 1 In a proposal, the literature review is generally brief and to the point. The literature selected should be pertinent and relevant. 6

Against this background, you then present the rationale of the proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing.

4. Objectives: Research objectives are the goals to be achieved by conducting the research. 5 They may be stated as ‘general’ and ‘specific’.

The general objective of the research is what is to be accomplished by the research project, for example, to determine whether or not a new vaccine should be incorporated in a public health program.

The specific objectives relate to the specific research questions the investigator wants to answer through the proposed study and may be presented as primary and secondary objectives, for example, primary: To determine the degree of protection that is attributable to the new vaccine in a study population by comparing the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. 5 Secondary: To study the cost-effectiveness of this programme.

Young investigators are advised to resist the temptation to put too many objectives or over-ambitious objectives that cannot be adequately achieved by the implementation of the protocol. 3

5. Variables: During the planning stage, it is necessary to identify the key variables of the study and their method of measurement and unit of measurement must be clearly indicated. Four types of variables are important in research 5 :

a. Independent variables: variables that are manipulated or treated in a study in order to see what effect differences in them will have on those variables proposed as being dependent on them. The different synonyms for the term ‘independent variable’ which are used in literature are: cause, input, predisposing factor, risk factor, determinant, antecedent, characteristic and attribute.

b. Dependent variables: variables in which changes are results of the level or amount of the independent variable or variables.

Synonyms: effect, outcome, consequence, result, condition, disease.

c. Confounding or intervening variables: variables that should be studied because they may influence or ‘mix’ the effect of the independent variables. For instance, in a study of the effect of measles (independent variable) on child mortality (dependent variable), the nutritional status of the child may play an intervening (confounding) role.

d. Background variables: variables that are so often of relevance in investigations of groups or populations that they should be considered for possible inclusion in the study. For example sex, age, ethnic origin, education, marital status, social status etc.

The objective of research is usually to determine the effect of changes in one or more independent variables on one or more dependent variables. For example, a study may ask "Will alcohol intake (independent variable) have an effect on development of gastric ulcer (dependent variable)?"

Certain variables may not be easy to identify. The characteristics that define these variables must be clearly identified for the purpose of the study.

6. Questions and/ or hypotheses: If you as a researcher know enough to make prediction concerning what you are studying, then the hypothesis may be formulated. A hypothesis can be defined as a tentative prediction or explanation of the relationship between two or more variables. In other words, the hypothesis translates the problem statement into a precise, unambiguous prediction of expected outcomes. Hypotheses are not meant to be haphazard guesses, but should reflect the depth of knowledge, imagination and experience of the investigator. 5 In the process of formulating the hypotheses, all variables relevant to the study must be identified. For example: "Health education involving active participation by mothers will produce more positive changes in child feeding than health education based on lectures". Here the independent variable is types of health education and the dependent variable is changes in child feeding.

A research question poses a relationship between two or more variables but phrases the relationship as a question; a hypothesis represents a declarative statement of the relations between two or more variables. 7

For exploratory or phenomenological research, you may not have any hypothesis (please do not confuse the hypothesis with the statistical null hypothesis). 1 Questions are relevant to normative or census type research (How many of them are there? Is there a relationship between them?). Deciding whether to use questions or hypotheses depends on factors such as the purpose of the study, the nature of the design and methodology, and the audience of the research (at times even the outlook and preference of the committee members, particularly the Chair). 6

7. Methodology: The method section is very important because it tells your research Committee how you plan to tackle your research problem. The guiding principle for writing the Methods section is that it should contain sufficient information for the reader to determine whether the methodology is sound. Some even argue that a good proposal should contain sufficient details for another qualified researcher to implement the study. 1 Indicate the methodological steps you will take to answer every question or to test every hypothesis illustrated in the Questions/hypotheses section. 6 It is vital that you consult a biostatistician during the planning stage of your study, 8 to resolve the methodological issues before submitting the proposal.

This section should include:

Research design: The selection of the research strategy is the core of research design and is probably the single most important decision the investigator has to make. The choice of the strategy, whether descriptive, analytical, experimental, operational or a combination of these depend on a number of considerations, 5 but this choice must be explained in relation to the study objectives. 3

Research subjects or participants: Depending on the type of your study, the following questions should be answered 3 , 5

- - What are the criteria for inclusion or selection?

- - What are the criteria for exclusion?

- - What is the sampling procedure you will use so as to ensure representativeness and reliability of the sample and to minimize sampling errors? The key reason for being concerned with sampling is the issue of validity-both internal and external of the study results. 9

- - Will there be use of controls in your study? Controls or comparison groups are used in scientific research in order to increase the validity of the conclusions. Control groups are necessary in all analytical epidemiological studies, in experimental studies of drug trials, in research on effects of intervention programmes and disease control measures and in many other investigations. Some descriptive studies (studies of existing data, surveys) may not require control groups.

- - What are the criteria for discontinuation?

Sample size: The proposal should provide information and justification (basis on which the sample size is calculated) about sample size in the methodology section. 3 A larger sample size than needed to test the research hypothesis increases the cost and duration of the study and will be unethical if it exposes human subjects to any potential unnecessary risk without additional benefit. A smaller sample size than needed can also be unethical as it exposes human subjects to risk with no benefit to scientific knowledge. Calculation of sample size has been made easy by computer software programmes, but the principles underlying the estimation should be well understood.

Interventions: If an intervention is introduced, a description must be given of the drugs or devices (proprietary names, manufacturer, chemical composition, dose, frequency of administration) if they are already commercially available. If they are in phases of experimentation or are already commercially available but used for other indications, information must be provided on available pre-clinical investigations in animals and/or results of studies already conducted in humans (in such cases, approval of the drug regulatory agency in the country is needed before the study). 3

Ethical issues 3 : Ethical considerations apply to all types of health research. Before the proposal is submitted to the Ethics Committee for approval, two important documents mentioned below (where appropriate) must be appended to the proposal. In additions, there is another vital issue of Conflict of Interest, wherein the researchers should furnish a statement regarding the same.

The Informed consent form (informed decision-making): A consent form, where appropriate, must be developed and attached to the proposal. It should be written in the prospective subjects’ mother tongue and in simple language which can be easily understood by the subject. The use of medical terminology should be avoided as far as possible. Special care is needed when subjects are illiterate. It should explain why the study is being done and why the subject has been asked to participate. It should describe, in sequence, what will happen in the course of the study, giving enough detail for the subject to gain a clear idea of what to expect. It should clarify whether or not the study procedures offer any benefits to the subject or to others, and explain the nature, likelihood and treatment of anticipated discomfort or adverse effects, including psychological and social risks, if any. Where relevant, a comparison with risks posed by standard drugs or treatment must be included. If the risks are unknown or a comparative risk cannot be given it should be so stated. It should indicate that the subject has the right to withdraw from the study at any time without, in any way, affecting his/her further medical care. It should assure the participant of confidentiality of the findings.

Ethics checklist: The proposal must describe the measures that will be undertaken to ensure that the proposed research is carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical research involving Human Subjects. 10 It must answer the following questions:

- • Is the research design adequate to provide answers to the research question? It is unethical to expose subjects to research that will have no value.

- • Is the method of selection of research subjects justified? The use of vulnerable subjects as research participants needs special justification. Vulnerable subjects include those in prison, minors and persons with mental disability. In international research it is important to mention that the population in which the study is conducted will benefit from any potential outcome of the research and the research is not being conducted solely for the benefit of some other population. Justification is needed for any inducement, financial or otherwise, for the participants to be enrolled in the study.

- • Are the interventions justified, in terms of risk/benefit ratio? Risks are not limited to physical harm. Psychological and social risks must also be considered.

- • For observations made, have measures been taken to ensure confidentiality?

Research setting 5 : The research setting includes all the pertinent facets of the study, such as the population to be studied (sampling frame), the place and time of study.

Study instruments 3 , 5 : Instruments are the tools by which the data are collected. For validated questionnaires/interview schedules, reference to published work should be given and the instrument appended to the proposal. For new a questionnaire which is being designed specifically for your study the details about preparing, precoding and pretesting of questionnaire should be furnished and the document appended to the proposal. Descriptions of other methods of observations like medical examination, laboratory tests and screening procedures is necessary- for established procedures, reference of published work cited but for new or modified procedure, an adequate description is necessary with justification for the same.

Collection of data: A short description of the protocol of data collection. For example, in a study on blood pressure measurement: time of participant arrival, rest for 5p. 10 minutes, which apparatus (standard calibrated) to be used, in which room to take measurement, measurement in sitting or lying down position, how many measurements, measurement in which arm first (whether this is going to be randomized), details of cuff and its placement, who will take the measurement. This minimizes the possibility of confusion, delays and errors.

Data analysis: The description should include the design of the analysis form, plans for processing and coding the data and the choice of the statistical method to be applied to each data. What will be the procedures for accounting for missing, unused or spurious data?

Monitoring, supervision and quality control: Detailed statement about the all logistical issues to satisfy the requirements of Good Clinical Practices (GCP), protocol procedures, responsibilities of each member of the research team, training of study investigators, steps taken to assure quality control (laboratory procedures, equipment calibration etc)

Gantt chart: A Gantt chart is an overview of tasks/proposed activities and a time frame for the same. You put weeks, days or months at one side, and the tasks at the other. You draw fat lines to indicate the period the task will be performed to give a timeline for your research study (take help of tutorial on youtube). 11

Significance of the study: Indicate how your research will refine, revise or extend existing knowledge in the area under investigation. How will it benefit the concerned stakeholders? What could be the larger implications of your research study?

Dissemination of the study results: How do you propose to share the findings of your study with professional peers, practitioners, participants and the funding agency?

Budget: A proposal budget with item wise/activity wise breakdown and justification for the same. Indicate how will the study be financed.

References: The proposal should end with relevant references on the subject. For web based search include the date of access for the cited website, for example: add the sentence "accessed on June 10, 2008".

Appendixes: Include the appropriate appendixes in the proposal. For example: Interview protocols, sample of informed consent forms, cover letters sent to appropriate stakeholders, official letters for permission to conduct research. Regarding original scales or questionnaires, if the instrument is copyrighted then permission in writing to reproduce the instrument from the copyright holder or proof of purchase of the instrument must be submitted.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.