Thomas Jefferson University

- Cost & scholarships

- Essay prompt

Want to see your chances of admission at Thomas Jefferson University?

We take every aspect of your personal profile into consideration when calculating your admissions chances.

Thomas Jefferson University’s 2023-24 Essay Prompts

Common app personal essay.

The essay demonstrates your ability to write clearly and concisely on a selected topic and helps you distinguish yourself in your own voice. What do you want the readers of your application to know about you apart from courses, grades, and test scores? Choose the option that best helps you answer that question and write an essay of no more than 650 words, using the prompt to inspire and structure your response. Remember: 650 words is your limit, not your goal. Use the full range if you need it, but don‘t feel obligated to do so.

Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.

The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?

Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. What prompted your thinking? What was the outcome?

Reflect on something that someone has done for you that has made you happy or thankful in a surprising way. How has this gratitude affected or motivated you?

Discuss an accomplishment, event, or realization that sparked a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others.

Describe a topic, idea, or concept you find so engaging that it makes you lose all track of time. Why does it captivate you? What or who do you turn to when you want to learn more?

Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you‘ve already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one of your own design.

What will first-time readers think of your college essay?

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thomas Jefferson University Requirements for Admission

Choose your test.

What are Thomas Jefferson University's admission requirements? While there are a lot of pieces that go into a college application, you should focus on only a few critical things:

- GPA requirements

- Testing requirements, including SAT and ACT requirements

- Application requirements

In this guide we'll cover what you need to get into Thomas Jefferson University and build a strong application.

School location: Philadelphia, PA

Admissions Rate: 87.5%

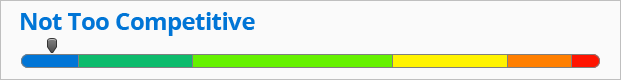

If you want to get in, the first thing to look at is the acceptance rate. This tells you how competitive the school is and how serious their requirements are.

The acceptance rate at Thomas Jefferson University is 87.5% . For every 100 applicants, 88 are admitted.

This means the school is lightly selective . The school will have their expected requirements for GPA and SAT/ACT scores. If you meet their requirements, you're almost certain to get an offer of admission. But if you don't meet Thomas Jefferson University's requirements, you'll be one of the unlucky few people who gets rejected.

We can help. PrepScholar Admissions is the world's best admissions consulting service. We combine world-class admissions counselors with our data-driven, proprietary admissions strategies . We've overseen thousands of students get into their top choice schools , from state colleges to the Ivy League.

We know what kinds of students colleges want to admit. We want to get you admitted to your dream schools.

Learn more about PrepScholar Admissions to maximize your chance of getting in.

Thomas Jefferson University GPA Requirements

Many schools specify a minimum GPA requirement, but this is often just the bare minimum to submit an application without immediately getting rejected.

The GPA requirement that really matters is the GPA you need for a real chance of getting in. For this, we look at the school's average GPA for its current students.

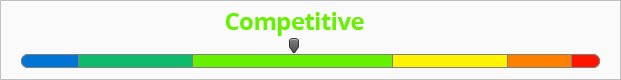

Average GPA: 3.74

The average GPA at Thomas Jefferson University is 3.74 .

(Most schools use a weighted GPA out of 4.0, though some report an unweighted GPA.

With a GPA of 3.74, Thomas Jefferson University requires you to be above average in your high school class. You'll need at least a mix of A's and B's, with more A's than B's. You can compensate for a lower GPA with harder classes, like AP or IB classes. This will show that you're able to handle more difficult academics than the average high school student.

SAT and ACT Requirements

Each school has different requirements for standardized testing. Only a few schools require the SAT or ACT, but many consider your scores if you choose to submit them.

Thomas Jefferson University hasn't explicitly named a policy on SAT/ACT requirements, but because it's published average SAT or ACT scores (we'll cover this next), it's likely test flexible. Typically, these schools say, "if you feel your SAT or ACT score represents you well as a student, submit them. Otherwise, don't."

Despite this policy, the truth is that most students still take the SAT or ACT, and most applicants to Thomas Jefferson University will submit their scores. If you don't submit scores, you'll have one fewer dimension to show that you're worthy of being admitted, compared to other students. We therefore recommend that you consider taking the SAT or ACT, and doing well.

Thomas Jefferson University ACT Requirements

Many schools say they have no ACT score cutoff, but the truth is that there is a hidden ACT requirement. This is based on the school's average score.

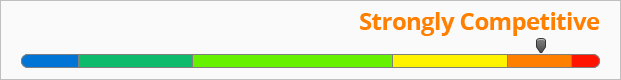

Average ACT: 29

The average ACT score at Thomas Jefferson University is 29. This score makes Thomas Jefferson University Moderately Competitive for ACT scores.

The 25th percentile ACT score is 26, and the 75th percentile ACT score is 31. In other words, a 26 places you below average, while a 31 will move you up to above average.

ACT Score Sending Policy

If you're taking the ACT as opposed to the SAT, you have a huge advantage in how you send scores, and this dramatically affects your testing strategy.

Here it is: when you send ACT scores to colleges, you have absolute control over which tests you send. You could take 10 tests, and only send your highest one. This is unlike the SAT, where many schools require you to send all your tests ever taken.

This means that you have more chances than you think to improve your ACT score. To try to aim for the school's ACT requirement of 26 and above, you should try to take the ACT as many times as you can. When you have the final score that you're happy with, you can then send only that score to all your schools.

ACT Superscore Policy

By and large, most colleges do not superscore the ACT. (Superscore means that the school takes your best section scores from all the test dates you submit, and then combines them into the best possible composite score). Thus, most schools will just take your highest ACT score from a single sitting.

We weren't able to find the school's exact ACT policy, which most likely means that it does not Superscore. Regardless, you can choose your single best ACT score to send in to Thomas Jefferson University, so you should prep until you reach our recommended target ACT score of 26.

Download our free guide on the top 5 strategies you must be using to improve your score. This guide was written by Harvard graduates and ACT perfect scorers. If you apply the strategies in this guide, you'll study smarter and make huge score improvements.

SAT/ACT Writing Section Requirements

Currently, only the ACT has an optional essay section that all students can take. The SAT used to also have an optional Essay section, but since June 2021, this has been discontinued unless you are taking the test as part of school-day testing in a few states. Because of this, no school requires the SAT Essay or ACT Writing section, but some schools do recommend certain students submit their results if they have them.

Thomas Jefferson University considers the SAT Essay/ACT Writing section optional and may not include it as part of their admissions consideration. You don't need to worry too much about Writing for this school, but other schools you're applying to may require it.

Final Admissions Verdict

Because this school is lightly selective, you have a great shot at getting in, as long as you don't fall well below average . Aim for a 26 ACT or higher, and you'll almost certainly get an offer of admission. As long as you meet the rest of the application requirements below, you'll be a shoo-in.

But if you score below our recommended target score, you may be one of the very few unlucky people to get rejected.

Admissions Calculator

Here's our custom admissions calculator. Plug in your numbers to see what your chances of getting in are. Pick your test: ACT

- 80-100%: Safety school: Strong chance of getting in

- 50-80%: More likely than not getting in

- 20-50%: Lower but still good chance of getting in

- 5-20%: Reach school: Unlikely to get in, but still have a shot

- 0-5%: Hard reach school: Very difficult to get in

How would your chances improve with a better score?

Take your current SAT score and add 160 points (or take your ACT score and add 4 points) to the calculator above. See how much your chances improve?

At PrepScholar, we've created the leading online SAT/ACT prep program . We guarantee an improvement of 160 SAT points or 4 ACT points on your score, or your money back.

Here's a summary of why we're so much more effective than other prep programs:

- PrepScholar customizes your prep to your strengths and weaknesses . You don't waste time working on areas you already know, so you get more results in less time.

- We guide you through your program step-by-step so that you're never confused about what you should be studying. Focus all your time learning, not worrying about what to learn.

- Our team is made of national SAT/ACT experts . PrepScholar's founders are Harvard graduates and SAT perfect scorers . You'll be studying using the strategies that actually worked for them.

- We've gotten tremendous results with thousands of students across the country. Read about our score results and reviews from our happy customers .

There's a lot more to PrepScholar that makes it the best SAT/ACT prep program. Click to learn more about our program , or sign up for our 5-day free trial to check out PrepScholar for yourself:

Application Requirements

Every school requires an application with the bare essentials - high school transcript and GPA, application form, and other core information. Many schools, as explained above, also require SAT and ACT scores, as well as letters of recommendation, application essays, and interviews. We'll cover the exact requirements of Thomas Jefferson University here.

Application Requirements Overview

- Common Application Not accepted

- Electronic Application Not available

- Essay or Personal Statement Required for all freshmen

- Letters of Recommendation 2

- Interview Not required

- Application Fee $50

- Fee Waiver Available? Available

- Other Notes

Testing Requirements

- SAT or ACT Considered if submitted

- SAT Essay or ACT Writing Optional

- SAT Subject Tests

- Scores Due in Office July 1

Coursework Requirements

- Subject Required Years

- Foreign Language

- Social Studies

Deadlines and Early Admissions

- Offered? Deadline Notification

- Yes July 31 December 3

- Yes November 1 December 3

Admissions Office Information

- Address: 1020 Philadelphia, PA 19107

- Phone: (215) 955-6000

- Fax: (215) 951-2907

- Email: [email protected]

Other Schools For You

If you're interested in Thomas Jefferson University, you'll probably be interested in these schools as well. We've divided them into 3 categories depending on how hard they are to get into, relative to Thomas Jefferson University.

Data on this page is sourced from Peterson's Databases © 2023 (Peterson's LLC. All rights reserved.) as well as additional publicly available sources.

If You Liked Our Advice...

Our experts have written hundreds of useful articles on improving your SAT score and getting into college. You'll definitely find something useful here.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get FREE strategies and guides sent to your email. Learn how to ace the SAT with exclusive tips and insights that we share with our private newsletter subscribers.

You should definitely follow us on social media . You'll get updates on our latest articles right on your feed. Follow us on all of our social networks:

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

Quick links.

- About Founders Online

- Major Funders

- Search Help

- How to Use This Site

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Teaching Resources

About the Papers of Thomas Jefferson

Begun in 1943 as a partnership between Princeton University and Princeton University Press, the Papers of Thomas Jefferson was the first modern historical documentary edition. The project includes not only the letters and other documents that Jefferson wrote, but also those he received. Founding editor Julian P. Boyd designed an edition that would provide accurate texts with accompanying historical context. With the publication of the first volume in 1950 and the first volume of the Retirement Series in 2004, these volumes print, summarize, note, or otherwise account for virtually every document Jefferson wrote and received. Today, the project regularly publishes two volumes a year under the leadership of General Editor James P. McClure at Princeton University and J. Jefferson Looney, the Daniel P. Jordan Editor of the Jefferson Retirement Series at Monticello. A team of historians at each location transcribes, verifies, annotates, and indexes documents copied from over nine hundred repositories and collections worldwide, maintaining the high standards crafted by Boyd and continued by his successors Charles T. Cullen, John Catanzariti, and Barbara B. Oberg. The edition includes a topically arranged Second Series of volumes arranged by topic, one title of which, Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826, edited by James A. Bear, Jr., and Lucia C. Stanton, is available through Founders Online. Distinguished advisory committees assist both the Princeton group and the editors at Monticello .

The Jefferson Papers at Princeton received its initial funding from the New York Times. Since then, support has been provided by Princeton University, private donors, major foundations, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Retirement Series, sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and located at Monticello, began with a generous grant from the Pew Charitable Trusts, and has been supported by leading gifts from Richard Gilder, Mrs. Martin S. Davis, and Thomas A. Saunders III, as well as subsequent generous gifts from Janemarie D. and Donald A. King, Jr., Alice Handy and Peter Stoudt, Harlan Crow, Mr. and Mrs. E. Charles Longley, Jr., and the Abby S. and Howard P. Milstein Foundation.

The volumes published by Princeton University Press provide the foundation of the Jefferson electronic edition sponsored by the University of Virginia Press and appearing through Founders Online. For more information, visit the websites for the main series and the Retirement Series .

See a complete list of Jefferson Papers volumes included in Founders Online, with links to the documents.

The letterpress edition of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson is available from Princeton University Press .

Copyright © by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Founding of Thomas Jefferson's University

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Darcy R Fryer, The Founding of Thomas Jefferson's University, Journal of American History , Volume 107, Issue 3, December 2020, Pages 747–748, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaaa382

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Late in life, Thomas Jefferson turned his thoughts to the role of education in a young republic—and he was sufficiently proud of his insights and innovations to make “father of the University of Virginia” the culmination of his epitaph. But how distinctive was Jefferson's university? The Founding of Thomas Jefferson's University , which sprang from a pair of conferences held by the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies and the American Philosophical Society in the spring of 2018, commemorates the bicentenary of the University of Virginia with essays that explore Jefferson's educational thought, the University of Virginia's architecture, curriculum, and student body, and the wider culture of pedagogy in the early republic.

The volume is ambitiously envisioned but awkwardly constructed, perhaps a bit like the young University of Virginia. Readers will long for a fuller initial description of the university's structure, curriculum, and academic culture; the most academically oriented essays, Carolyn Eastman's on oratory and Johann N. Neem's on Jefferson's philosophy of liberal education, stand at the end of the book. Intriguingly, the collection features among its contributors a diverse array of experts, including librarians, architects, and a professor of medicine, as well as historians. One section of the book explores the values embedded in the university's architecture and layout of the campus. Two essays on libraries, and a third essay on legal education that deals extensively with the books from which students “read” law, offer some of the freshest and most vivid insights into how early University of Virginia students learned. At the same time, they highlight how rigid and controlling Jefferson could be in pursuit of republican ideals. As Endrina Tay recounts, the library was originally open for only one hour per week, and students were permitted to check out library books only with the specific permission of faculty members.

Organization of American Historians members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2020 | 13 |

| January 2021 | 6 |

| February 2021 | 4 |

| March 2021 | 3 |

| May 2021 | 2 |

| June 2021 | 8 |

| August 2021 | 2 |

| September 2021 | 2 |

| October 2021 | 1 |

| November 2021 | 3 |

| February 2022 | 3 |

| March 2022 | 5 |

| May 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 1 |

| September 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 2 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Help inform the discussion

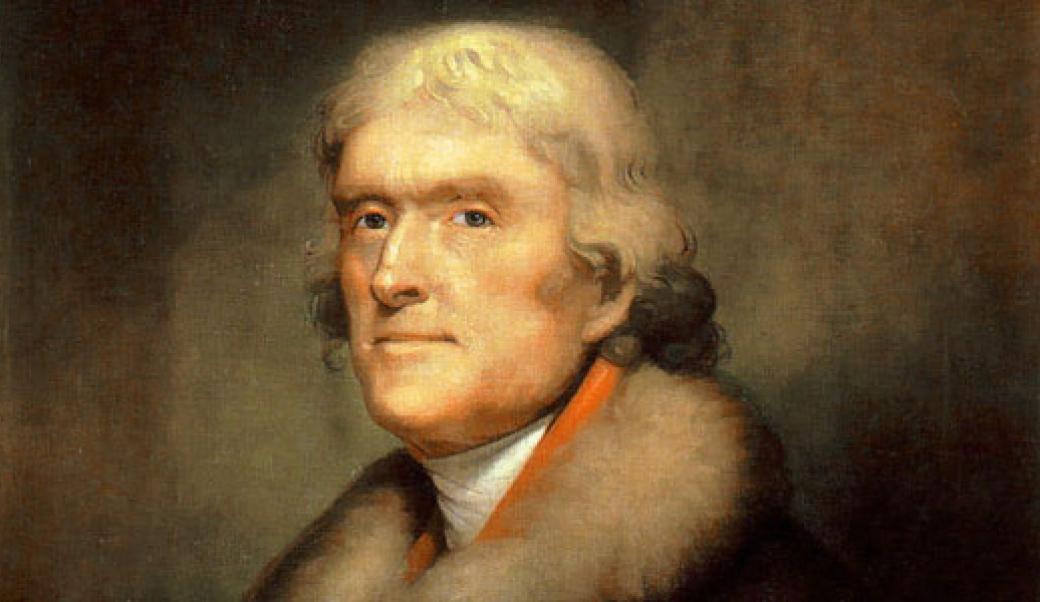

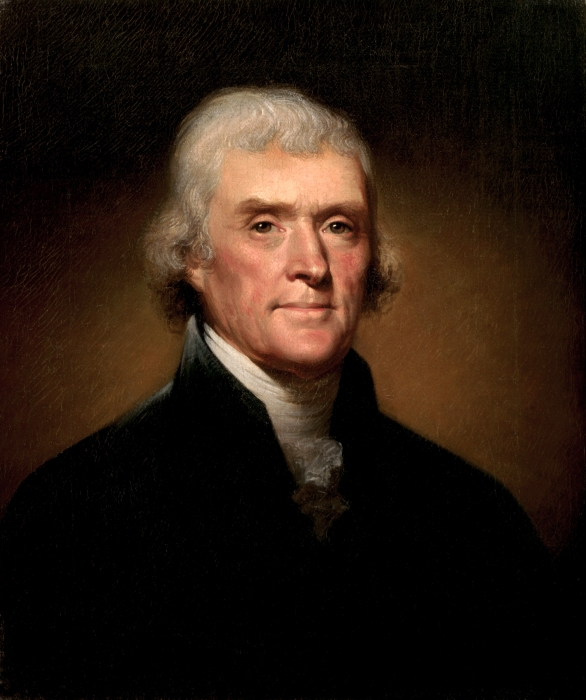

U.S. Presidents / Thomas Jefferson

1743 - 1826

Thomas jefferson.

…some honest men fear that a republican government can not be strong, that this Government is not strong enough; but would the honest patriot…abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm…? I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest Government on earth. First Inaugural Address

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, spent his childhood roaming the woods and studying his books on a remote plantation in the Virginia Piedmont. Thanks to the prosperity of his father, Jefferson had an excellent education. After years in boarding school, where he excelled in classical languages, Jefferson enrolled in William and Mary College in his home state of Virginia, taking classes in science, mathematics, rhetoric, philosophy, and literature. He also studied law, and by the time he was admitted to the Virginia bar in April 1767, many considered him to have one of the nation's best legal minds.

Life In Depth Essays

- Life in Brief

- Life Before the Presidency

- Campaigns and Elections

- Domestic Affairs

- Foreign Affairs

- Life After the Presidency

- Family Life

- The American Franchise

- Impact and Legacy

Chicago Style

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Thomas Jefferson.” Accessed May 31, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/jefferson.

Professor of History

Professor Peter Onuf is the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia.

- -The Mind of Thomas Jefferson

- -Jefferson's Empire: The Language of American Nationhood

- -Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture (editor…

Featured Insights

US Presidents and Slavery

Before the Civil War, many US presidents, including Jefferson, owned enslaved people, and all of them had to deal with slavery as a political issue

Thomas Jefferson’s electoral revolution of 1800

Alan Taylor, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia, talks about the transfer of power to President Jefferson during the election of 1800

Thomas Jefferson and the problem of Union

History professors Gary Gallagher and Peter Onuf discuss Thomas Jefferson as part of the Miller Center’s Historical Presidency series

American Gospel: God, the founding fathers, and the making of a nation

Jon Meacham discusses America's ongoing struggle between politics and religion and looks at how our founding fathers' views on faith shaped religion's place in American public life

March 4, 1801: First Inaugural Address

June 20, 1803: instructions to captain lewis, december 6, 1805: special message to congress on foreign policy, featured video.

Redeeming Thomas Jefferson?

This American Forum episode examines Thomas Jefferson with two of America’s most esteemed Jefferson scholars.

Featured Publications

- Secondary Essay Prompts

Secondary Essay Prompts – Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Secondary Essay Prompts for the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University

Below are the secondary essay prompts for the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, PA.

2020 – 2021

- Do you have any additional information that hasn’t been covered? (4000 Characters)

- Explain any impact that COVID-19 may have had on your educational/research/volunteering or employment plans. (2500 characters)

- Jefferson is also asking for SAT/ACT scores.

2019 – 2020

- If there is any additional information you would like to provide please include it in the box below.

- Limit to 4000 characters.

2016 – 2017

Secondary essay webcast with Dr. Jessica Freedman, founder and president of MedEdits Medical Admissions. Read more about Dr. Freedman.

Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College

Topics covered in this presentation:

- When should I submit my secondary essays?

- Pay attention to the word/character limits.

- Can I recycle secondary essay prompts for multiple schools?

- Identify topics that you left out of your primary application.

- And, much more.

Below are the secondary essay prompts for the Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College.

2017 – 2018.

- The Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College strives to ensure that its students become respectful physicians who embrace all dimensions of caring for the whole person. Please describe how your personal characteristics or life experiences will contribute to the Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College community and bring educational benefits to our student body. (1000 characters)

- Is there any further information that you would like the Committee on Admissions to be aware of when reviewing your file that you were not able to notate in another section of this or the AMCAS Application? (1000 characters)

- Why have you chosen to apply to the Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College and how do you think your education at Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College will prepare you to become a physician for the future? (1 page, formatted at your discretion, upload as PDF)

Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Medical College Admissions Requirements

Learn more about this school:

Secondary Essay Prompts for Other Schools

Do you want to see secondary essay prompts for other medical schools?

Select a school below:

Secondary Essay Prompts By School

*Data collected from MSAR 2022-2023, 2022 Osteopathic Medical College Information Book, and institution website.

Disclaimer: The information on this page was shared by students and/or can be found on each medical school’s website. MedEdits does not guarantee it’s accuracy or authenticity.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Secondary Essay Prompts – Baylor College of Medicine

Secondary Essay Prompts – University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Secondary Essay Prompts – University of Miami Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine

Secondary Essay Prompts – Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Secondary Essay Prompts – Mayo Medical School, Rochester, MN

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Website Disclaimer

- Terms and Conditions

- MedEdits Privacy Policy

National Historical Publications & Records Commission

The Papers of Thomas Jefferson

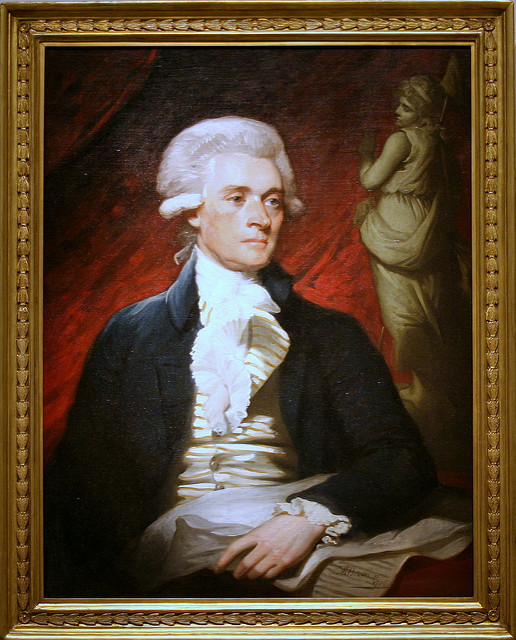

Miniature of Thomas Jefferson, 1788 by John Trumbull. Courtesy Monticello.

Princeton University and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello

Additional information at: https://jeffersonpapers.princeton.edu/

The Rotunda site contains a searchable database of all thirty-six volumes published through 2009 into one searchable online resource. In addition, it includes the first four volumes of the Retirement Series sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which documents the time between Jefferson’s return to private life and his death in 1826. The Retirement Series is creating the definitive edition of Thomas Jefferson’s letters and papers covering the period from 1809 to 1826 in both letterpress and digital form. More information is available at https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/project-description and via Rotunda at http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/TSJN.html

The Jefferson Papers are also part of Founders Online at founders.archives.gov

A comprehensive edition of the papers of Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826), third President of the United States. Jefferson was a lawyer, delegate to the Virginia House of Burgesses, and landowner, before beginning his political career in 1775. At age 33, he was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence. At the beginning of the American Revolution he served in the Continental Congress representing Virginia and then served as a wartime Governor of Virginia (1779–1781). Just after the war ended, from mid-1784 Jefferson served as a diplomat, stationed in Paris. Under President Washington, Jefferson was the first United States Secretary of State (1790–1793) and was elected Vice President in 1796. Elected president in 1800, he oversaw the purchase of the vast Louisiana Territory from France (1803), and sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) to explore the new west. He was the founder of the University of Virginia. The NHPRC also supported a microfilm edition of Jefferson’s Papers at the University of Virginia, 1732-1828. Ten reels.

Forty-three completed volumes of a planned 60-volume edition.

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

Top of page

Collection Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606 to 1827

American sphinx: the contradictions of thomas jefferson.

An essay by historian Joseph Ellis from the November-December 1994 issue of Civilization: The Magazine of the Library of Congress .

American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. This essay was originally published in the November-December 1994 issue of Civilization: The Magazine of the Library of Congress and bears a slightly different title from the book that followed it. This essay may not be reprinted in any other form or by any other source. For more recent writings by Ellis and others, see the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation's Jefferson Web site, Monticello: The Home of Thomas Jefferson External , including discussion of Sally Hemings and the Hemings family External .

A Reincarnated Jefferson

The idea clicked into full consciousness one cold evening in November of 1993, in a large brick church in Worcester, Massachusetts. It was election night, and the streets of Worcester were clotted with drivers heading for the polls. The occasion that lured me into this morass was the public appearance of Thomas Jefferson. Or rather, the performance of an impersonator named Clay Jenkinson, who portrayed a reincarnated Jefferson, alive among us in the late 20th century.

I figured that a maximum of 40 or 50 hardy souls would show up. After all, this was a semischolarly affair, designed to bring Jefferson to life without fanfare or patriotic pageantry. Maybe down in Charlottesville or Richmond you could pack them in by murmuring, "Jefferson lives," but this was New England, which has a long outstanding suspicion of Virginia grandees.

As it turned out, about 400 enthusiastic New Englanders crowded into the church. Jenkinson began talking in the languid cadence of the Tidewater about Jefferson's early days at the College of William and Mary, his thoughts on the American Revolution, his love of French wine and French ideas, his accomplishments and frustrations as a political leader and president, his obsession with education, his elegiac correspondence with John Adams, his bottomless hope in America's democratic prospects. Jenkinson obviously knew his stuff. He was delivering an elegantly disguised history lecture that drew upon modern Jefferson scholarship quite deftly. The audience was entranced.

At the end, still in character and costume, Jenkinson took questions. What would you do about the health-care problem, Mr. Jefferson. Who is your favorite modern-day American president? Should we do something about the atrocities in Bosnia? Sprinkled into this mixture were several questions about American history and Jefferson's life: Why did you never remarry? What did you mean by "pursuit of happiness" in the Declaration of Independence? Why did you own slaves? This last question was the only one with a sharp edge, and Jenkinson handled it carefully. Slavery was a moral travesty, he said, an institution clearly at odds with the values of the American Revolution. He has tried his best to persuade his countrymen to end the slave trade and gradually end slavery itself. But he had failed. As for his own slaves, he treated them benevolently, as the fellow human beings they were. He concluded with a question of his own: What else would you have wanted me to do?

This seemed to satisfy the audience. But I was struck by the fact that when Jenkinson-as- Jefferson volunteered information on his less admirable features--his accommodation with slavery, his stiffbacked formality toward women, his tendency to gloss over complex social problems with felicitous language--the audience did not follow up. That's not what they had come to hear. If Jefferson was America's Mona Lisa, they had come to see him smiling.

Even so, I was surprised that no one asked a question about Sally Hemings, the young mulatto slave who was reputed to be Jefferson's lover and the mother of four of his children. My own experience as a college teacher suggested that most students could be counted on to know two things about Jefferson--that he wrote the Declaration of Independence and that he had been accused of an affair with Sally Hemings. This piece of scandalous gossip first surfaced when Jefferson was president, in 1802, and subsequently affixed itself to his reputation like a tin can that then rattled through the pages of history. A best-selling biography of Jefferson by Fawn Brodie, published in 1974, revived the old rumor for the modern generation, although in Brodie's version Jefferson and Sally loved each other, transforming the story of rape and subjugation (itself probably untrue) into a tragic but touching romance (an utter fabrication).

Jenkinson surprised me. He was neither historian nor an actor. A late-thirty-ish Midwesterner somewhat shorter than Jefferson's 6 feet 2 1/2 inches, he had graduated from the University of Minnesota and gone on to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar to study English literature. Currently on the faculty of the University of Nevada at Reno, he began assuming Jefferson's identity in 1984, when he helped found "the Great Plains Chautauqua," which was described as "a traveling humanities tent show" based in Bismark, North Dakota.

Jenkinson, who called himself a "scholar-impersonator," had somehow made Jefferson his own. Several state legislatures, scores of college and university audiences, and an even larger number of public gatherings like the one at Worcester had found his renderings of Jefferson impressive. A few months after I saw him, Jenkinson was the star attraction at a gala Jefferson celebration hosted by President Clinton, where he won the hearts of the White House staff by saying that Jefferson would have dismissed the entire Whitewater investigation as "absolutely nobody's business."

I met Jenkinson earlier that evening at a dinner put on by the American Antiquarian Society. The room was full of local business leaders, school superintendents and state politicians. Also present were two filmmaking groups. From Florentine Films came Camilla Rockwell, who told me that Ken Burns, the leading documentary filmmaker in the country, was planning to do a major project on Jefferson for public television. And from the Jefferson Legacy Foundation came Bud Leeds and Chip Stokes, who had recently launched a campaign to raise funds for a big-budget commercial film on Jefferson. Leeds and Stokes were flying out to Los Angeles the next morning to confer with Francis Ford Coppola and other Hollywood luminaries about scripts and actors. Their entourage also included an Iranian millionaire who told me that he had fallen in love with Jefferson soon after escaping the persecution of Islamic fundamentalists, an experience that made him appreciate the Jeffersonian belief in religious freedom and the separation of church and state.

I found myself wondering what other prominent historical figure could generate this kind of turnout. Certainly not George Washington. He has the biggest monument on the Mall, and the capital city itself carries his name, but he is just too patriarchal, too distant. Jefferson is Jesus, who came to live among us. Washington is Jehovah, aloof and alone in heaven.

Maybe Lincoln, usually the winner whenever polls try to measure public opinion on great American presidents, would draw such a crowd. Ordinary citizens tend to know as much about the Gettysburg Address as about the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln is magical too, but his is a different kind of magic, a more somber magic with a tragic dimension. Jefferson is light, graceful, inspiring. Lincoln is heavy, biblical, burdened. Lincoln is more respected, but Jefferson more loved.

That, at least, was what I was thinking as I drove home from Worcester that November evening. I even conjured up a picture of Jefferson atop some American version of Mount Olympus, dismissing competitors for the summit with a flick of that famous wrist, the one that wrote the Declaration of Independence--and that never healed properly after he broke it vaulting over a fountain in Paris while rushing to meet Maria Cosway, the object of his affections.

A silly thought, to be sure, but just the kind of extravagant enthusiasm that seemed to flower in the popular imagination wherever and whenever the Jefferson myth got planted. At the center of the silliness, however, is an idea that I had half-known but never fully appreciated until that night: Jefferson is America's special addiction, and something is going on out there in the minds and hearts of ordinary Americans at this moment in our national history to make that addiction particularly powerful. It is as if the American citizenry harbors some worrisome questions about the state of the republic and looks to him as America's oracle to provide reassuring answers.

Jefferson as "America's Everyman"

Once such an interpretive pattern lodges itself in the mind, of course, it quickly pulls half-forgotten odds and ends of one's memory and aligns them within the new grid-work. What came to my mind was a thesis advanced 30 years ago by Merrill Peterson in The Jefferson Image in the American Mind .

Peterson discovered that Jefferson had become America's Everyman, the cult hero for wildly divergent and often antagonistic political movements throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The term Peterson used was "Protean Jefferson," which gave a respectably classical sound to what others might regard as Jefferson's disarming ideological promiscuity. Southern secessionists loved him; Northern abolitionists worshiped him; Gilded Age moguls echoed his warnings about federal power; Populists adored his advice about the evils of a banking conspiracy and the superiority of agrarian values. In the 1925 Scopes trial, both William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow were sure that Jefferson agreed with their positions on evolution. Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt both claimed him as their guide to the problems of the Great Depression. In the 1930s isolationists and interventionists cited him as their spiritual mentor.

At some point, as this Jeffersonian procession passed by, I began to wonder whether there was anything Jefferson did not stand for. Was he a real historical person who once lived "back there" in time? Or was he a free-floating Rorschach test we carried around with us "up here" in the present?

These questions had ominous implication for anyone who harbored the traditional assumption that the quest to understand historical figures was a scholarly affair that would, albeit incrementally and gradually, contribute to the popular understanding of who they were and what they stood for. It seemed that Jefferson was simply too resonant, too interactive, too inherently elusive for that. The people who had gathered in Worcester carried assumptions about what Jefferson stood for that were infinitely more powerful than any set of historical facts. America's greatest historians and biographers could labor for decades to produce the most authoritative and sophisticated studies of Thomas Jefferson--Peterson, in fact, had proceeded to do precisely that--and their findings would bounce off the popular image of Jefferson without making a dent. Jefferson was not just a uniquely powerful touchstone, not just a seductively enigmatic historical hero. He was the Great Sphinx of American history. Coming to terms with Jefferson meant coming to terms with the most cherished convictions and contested truths in contemporary American culture.

My emerging hypothesis--that we are in the midst of a resurgent love affair with Jefferson that speaks, in some mysterious way, to our current ideological condition--evidently was shared by the political maestros at the White House, whose overnight polls provided up-to-the-minute readings of the American pulse. The week of his inauguration, Bill Clinton retraced Jefferson's trip from Monticello to Washington. And the White House staff made a point of apprizing the press that the new president was reading an advance copy of a soon-to-be-published popular biography of Jefferson by Willard Sterne Randall.

Clinton had also contributed, if unintentionally, to this interest in Jefferson during the presidential campaign. Allegations that Clinton was a womanizer prompted a flurry of newspaper and television reports on the sexual improprieties of past presidents, especially John F. Kennedy and Franklin D. Roosevelt. During the very month of the presidential election, The Atlantic Monthly put Thomas Jefferson on its cover and featured an essay by Douglas Wilson, a distinguished Jeffersonian scholar, titled "Thomas Jefferson and the Character Issue."

A month or two later, I received a letter from Mary Jo Salter, a good friend who also happens to be one of America's most respected poets. Mary Jo was in Paris, where she was continuing to perform her duties as poetry editor of The New Republic and completing a volume of new poems. The longest poem in the collection, it turned out, focused on none other than the ubiquitous Mr. Jefferson.

This seemed too coincidental. Could it be that politicians, propagandists, poets and impersonators were all plugged into the same cultural grid, which somehow had its main power source buried beneath the mountain at Monticello? Mary Jo said that she wanted me to suggest some books and articles about Jefferson and his time. I responded with a list of books, most of which she had already read. What I wanted in return was an answer to the simple question: Why Jefferson?

For a poet of Mary Jo's sensibility, it was clearly not a question of politics, at least in the customary sense of the term. She is not one to slide her mind into comfortable ideological grooves or sing patriotic hymns about freedom and democracy. Like any serious poet, she tends to defy trends, listen to her own internal voice, make her own music.

And that was just the kind of answer she gave to my question. "I knew I had the first part of a poem when I ran across a mention somewhere of TJ buying a thermometer on July 4, 1776--and recording a peak temperature of 76 degrees," Mary Jo recalled in a letter. It was a coincidence that caught her eye, a detail with poetic possibilities. Then she encountered one of history's eeriest coincidences--the deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the same day, July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. For Mary Jo, it was perfect springboard for her imagination. As she put it, these coincidences were "poignant and eminently visual events."

Finally, she said that she was attracted to Jefferson's accessible complexity, what she called his "variousness." This was quite similar to Merrill Peterson's image of Protean Jefferson, but with a difference. Peterson emphasized the many meanings that posterity has imposed on Jefferson. Mary Jo was emphasizing the various and varied personae that actually existed inside Jefferson. "We love the fact that our favorite politician was a writer and a farmer and a scientists and an aesthete and a violinist," she wrote, "partly because we all wish to squeeze more out of our own 24-hour days...." Her Jefferson was a fascinating bundle of selves that beckoned to our modern sense of multiple identities. The poet, so it seemed to me, was getting closer to the essential appeal of Jefferson than were the biographers and historians.

The 250th Anniversary of Jefferson's Birth: Evocations

Meanwhile, the Jeffersonian flood was reaching new heights. During the year-long celebration of the 250th anniversary of Jefferson's birth, it seemed that every publishing house in America brought out a book on some aspect of his career or character. In addition to the full-length biography by Willard Sterne Randall, there were 17 new books with Jefferson's name in the title published in 1993. One of them, a novel by Max Byrd ( Jefferson ), offered an utterly captivating depiction of Jefferson's French phase and an evocation of his layered personality that rivaled Mary Jo's account in its imaginative power. (Byrd's novel supported my hunch that one needed the leeway provided by fiction or poetry to handle Jefferson's character compellingly.) Meanwhile, a major exhibition on "The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello" attracted upwards of 600,000 visitors to Monticello last year (Elvis' Graceland just barely surpassed this figure.) And from Paris, Mary Jo wrote to say that James Ivory and Ismail Merchant had set up production there for a film called "Jefferson in Paris," focusing on the romantic interlude with Maria Cosway and, so I learned later, starring Nick Nolte in the title role.

Nothing like this had accompanied the 250th birthday of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin or John Adams. Nor had Lincoln's 150th birthday generated anything like this popular outpouring. It was as if one had attended a Fourth of July fireworks display and, instead of the usual rockets and sparklers, witnessed the detonation of a 2-megaton bomb.

As a cultural phenomenon, the Jeffersonian explosion was not a movement controlled or shaped by scholars or professional historians. Jefferson was part of the public domain, with daring power outside the academic world. The folks who ran publishing houses, produced films and mounted exhibitions, as well as the foundation directors who gave away money for worthy causes, obviously regarded Jefferson as a sure bet. The market for things Jeffersonian was wide and deep and strikingly diverse. It was--well, what other word fit so nicely?--democratic, in the Jeffersonian sense of the term.

The admiration for Jefferson was as much a psychological as a political phenomenon. In the hands of a poet like Salter or a novelist like Byrd, Jefferson became not Everyman but Postmodern Man, a series of overlapping and interacting personae that talked to us but not to each other. He could walk past the slave quarters on Mulberry Row at Monticello without qualms or guilt while daydreaming about the rights of man with utter sincerity. He could purchase the finest and most expensive art and furniture for his many residences, all the while idealizing the pastoral virtues of the sturdy farmer. He could fall in love with beautiful women in fits of rhapsodic passion but never allow the deepest secrets of his soul to be shared with any living creature. He was, like us, layered and conflicted but, as we wish to be, always in control, the perfect model for his beloved ideal of "self-government."

Historians Rethink Jefferson

In the academic world, the winds were gusting in a different direction. Not that scholars had ignored Jefferson or consigned him to some second tier of historical significance. Far from it. The number of scholarly books and articles focusing on Jefferson or some aspect of his long career continued to grow at a geometric rate; it requires two full volumes just to list all the Jefferson scholarship, much of it coming in the last quarter century. The central scholarly project, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson , continues to appear from Princeton University Press at the stately pace of one volume every two years or so (25 volumes had appeared by 1993). And Dumas Malone's authoritative biography, Jefferson and His Time , is an equally stately six-volume behemoth that, thanks to introductory offers from the Book-of-the-Month Club and History Book Club, graces the libraries and coffee tables of countless American homes.

The problem, then, was not a lack of academic interest or scholarly attention. The problem was a lowered academic opinion of the man and his accomplishments. Jefferson's captivating contradictions had come to be seen by many historians as massive hypocrisies, his elegant articulations of the American creed as platitudinous nonsense. The love affair with Jefferson that flourishes in the public domain had finally turned sour in the academic world. Once the symbol of all that is right with America, Jefferson had become the symbol of much that is wrong.

You could look back and, with the advantage of hindsight--which is, after all, the historian's crucial intellectual asset--locate the moment when the tide began to turn. In 1968 Winthrop Jordan published White over Black , a magisterial reappraisal of race relations in early America that featured a section on Jefferson. Jordan's book, which won the major prizes, offered a subtle and psychologically sophisticated assessment of Jefferson's attitudes toward slavery and blacks, suggesting that he was emblematic of white American society in the way his deep-seated racist values were hidden within folds of his personality.

White over Black was hardly a heavy-handed indictment of Jefferson. Jordan's major point was that racism had infiltrated the American soul very early in our history and that Jefferson simply provided the most resonant example of the virulence of racist values and the commingling of racial and sexual drives. Jordan's interpretation adopted an agnostic attitude toward the allegations of a sexual liaison with Sally Hemings. It is one of those intriguing pieces of gossip that can never be proved or disproved. Regardless of his relationship with Hemings, Jordan argued, Jefferson's deepest feelings toward blacks had their origins in primal urges that, like the sex drive, came from deep within his subconscious. Many other scholarly books and articles soon took up related themes, but Jordan's account set the terms of the debate about the centrality of race and slavery in any appraisal of Jefferson. And once that became a chief measure of Jefferson's character, his stock was fated to fall.

Another symptom of imminent decline--again, all this in retrospect--was a 1970 essay by Eric McKitrick, a professor of history at Columbia University, in the New York Review of Books . McKitrick was reviewing the recent biographies of Jefferson by Dumas Malone and Merrill Peterson, who were not only experts on Jefferson but the avowed ringleaders of what has been called the "Charlottesville Mafia," scholarly keepers of the Jefferson flame. In the course of a fair-minded assessment, McKitrick had the temerity to ask whether it might not be time to declare a moratorium on the generally benign and gentlemanly posture toward Monticello Man that was the hallmark of Malone's and Peterson's works. "What about those traits of character that aren't heroic from an angle?" asked McKitrick, mentioning Jefferson's accommodation and dependence upon slavery as well as "the frequent smugness, the covert vindictiveness, ...the hand-washing, the downright hypocrisy." What about his very un-Churchillian performance as governor of Virginia during the American Revolution, when he failed to mobilize the militia and had to flee Monticello on horseback ahead of the marauding British army? What about the fiasco of his American Embargo in 1807, when he clung to the illusion that economic sanctions would keep us out of war with England, even after it was clear that they only devastated the American economy?

The list of critical questions went on, effectively making the general point that interpretations of the man guided by Jefferson's own world view, what McKitrick called "the view from Jefferson's camp," had just about exhausted their explanatory power. What we obviously needed from the next generation of Jeffersonian scholars were some less fastidious and less friendly biographers who did not have their hearts or headquarters at Charlottesville.

The 1992 "Jeffersonian Legacies" Conference

Rather amazingly, it was in Charlottesville that the scholarly reassessment of Jefferson reached a crescendo. It happened in October 1992, when the University of Virginia convened a conference to commemorate its founder under the apparently harmless rubric of "Jeffersonian Legacies." The result was an intellectual free-for-all that went on for six days and nights. The conference spawned a collection of 15 essays published in record time by the University Press of Virginia, an hour-long videotape of the proceedings shown on PBS, and a series of newspaper stories in the Richmond papers and The Washington Post . Advertised as a scholarly version of a birthday party, the conference assumed the character of a public trial, with Jefferson--and the version of American history he symbolized--cast in the role of defendant.

The chief argument for the prosecution was delivered by Paul Finkelman, a hard-charging historian from Virginia Tech. "Because he was the author of the Declaration of Independence," said Finkelman, "the test of Jefferson's position on slavery is not whether he was better than the worst of his generation, but whether he was the leader of the best." The answer had the clear ring of an indictment: "Jefferson fails the test." For Finkelman, historians like Malone and Peterson had been mesmerized by the "d-word," Jefferson as the apostle of democracy. The more appropriate d-words were dissimulation, duplicity and denial.

According to Finkelman, Jefferson was an out-and-out racist who believed that blacks were inherently inferior to whites and who rejected the possibility that blacks and whites could ever live together on an equal basis. Moreover, his several attempts to end the slave trade or restrict the expansion of slavery beyond the South were halfhearted, as was his contemplation of a program of gradual emancipation. His beloved Monticello and personal extravagances were possible only because of slave labor. Finkelman argued that it was misguided--worse, it was positively sickening--to celebrate Jefferson as the father of freedom. In Finkelman's view, Jefferson was the ultimate symbol of the discrepancy (another d-word) between American rhetoric and American reality.

If Finkelman was the chief prosecutor, the star witness for the prosecution was Robert Cooley, a middle-aged black man who claimed to be a direct descendant of Jefferson and Sally Hemings. Cooley offered himself as "living proof" that the story of Jefferson's sexual relationship with one of his slaves was true. No matter what the Charlottesville Mafia or the tour guides at Monticello said, several generations of blacks living in Ohio and Illinois were certain they had Jefferson's blood in their veins. Scholars always talk about the absence of documentation and hard evidence, but how could such evidence exist? "We couldn't write then," Cooley explained. "We were slaves." And Jefferson's white children had destroyed all written records of the relationship soon after his death. Cooley essentially pitted the oral tradition of the black community against the scholarly tradition of professional historians. Cooley's version of history might not have had the bulk of the hard evidence on its side, but it clearly had the political leverage. Whether or not Jefferson had an affair with Sally Hemings, he was guilty of so many other moral crimes that it hardly made any difference. The Hemings story was either true literally or true metaphorically. The Washington Post reporter covering the conference caught the mood: "What tough times these are for icons!"

If the historical profession had any final words of wisdom to offer in the wake of what was being called "the cacophony at Charlottesville," they came from Gordon Wood, generally regarded as the leading historian of the Revolutionary era. Wood, a conference participant, was asked to review the published collection of essays for The New York Review of Books .

Wood called for a halt to the appropriation of prominent historical figures like Jefferson to serve as rallying points for modern-day political constituencies on the left or right. "We Americans make a great mistake in idolizing...and making symbols of authentic historical figures," warned Wood, "who cannot and should not be ripped out of their own time and place." And Jefferson had been especially abused: "By turning Jefferson into the kind of transcendent moral hero that no authentic historically situated human being could ever be, we leave ourselves demoralized by the time-bound weaknesses of this eighteenth-century slaveholder." In effect, the canonization of Jefferson as our preeminent political saint, Wood was suggesting, virtually assured his eventual slide into the status of villain. Why? Because we know too much about him. And what we know would always undercut his saintly and heroic status, leaving us disappointed and then angry, much like a starry-eyed fan who makes the mistake of actually getting to know his idol. We invested too much in Jefferson. The core of the problem is not his inevitable flaws but our unrealistic expectations.

Coming from a historian of Wood's reputation, who had no special affection for Jefferson and no special ties with the Charlottesville Mafia, the assessment had the realistic ring of common sense, a welcome note of sobriety amid a band of shrill partisans. It was rooted in the sound scholarly recognition that the late 18th century is a foreign country with a separate culture of its own. The historian's job is not so much to protect Jefferson's reputation as to protect the integrity of the past from modern-day raiding parties with obvious ideological agendas.

All of which makes complete scholarly sense but absolutely no practical difference. Jefferson is not like most other historical subjects--dead, forgotten and nonchalantly entrusted to historians, who presumably serve as the gravekeepers for buried memories no one really cares about anymore. Jefferson has risen from the dead. Lots of Americans care about the meaning of his memory. Historians could not control his legacy because it has escaped from the past, which they oversee, and is living in the present, a foreign country for most of them.

Evidence of Jefferson's natural tendency to surge out of the past and into the present kept popping up in the press in the months after the Charlottesville conference. In The New York Review of Books , Garry Wills used his review of the exhibition at Monticello to paint an unflattering portrait of Jefferson as a compulsive consumer of expensive French wines, art and furniture, an indulged aristocrat whose exorbitant tastes belied his rustic rhetoric about yeoman farmers and republican virtue. A few months later, The New York Times reported on a mock trial of Jefferson by the Bar Association of New York City, presided over by none other than Chief Justice William Rehnquist. The indictment consisted of the following three counts: that he subverted the independence of the federal judiciary; that he lived in the lavish manner of Louis XIV (Wills' charge); and that he frequently violated the Bill of Rights. Though Jefferson was found not guilty on all charges, the salient fact was that he had been moved off his pedestal and into the witness box.

The "Jeffersonian Surge"

Whether the most appropriate command was "back to the future" or "forward to the past," many of the professional historians with whom I spoke were relieved when the 250th anniversary of Jefferson's birth was over. It meant that they could reclaim the historical Jefferson and "get on with their own work," free of the anachronistic questions about relevance and legacies. When I asked my academic colleagues about the phenomenon I was now calling the Jeffersonian Surge, most of them expressed bemused indifference. It was all hype, they observed, like one of the feeding frenzies in the contemporary talk-show culture--Jefferson as the historical equivalent of Michael Jackson or Tonya Harding. Or it could be explained pragmatically: Jefferson had managed to get himself institutionalized with a mansion at Monticello, a university at Charlottesville and a memorial on the Tidal Basin in Washington, so there were several permanent constituencies poised to plug his birthday for self-interested reasons. For a professional historian, the thing to do when confronted with this kind of loony sensationalism is to stand still, close one's eyes and wait for it to pass.

One exception to this general pattern was Peter Onuf, the successor to Merrill Peterson as Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia. Onuf predicted that scholarly criticism of Jefferson would seep into popular thinking, as the idealization of racial and ethnic diversity became an essential measure of America's dedication to equality. In effect, the democratic revolution Jefferson helped launch had now expanded to include a form of human equality--racial equality and integration--that Jefferson clearly could never have countenanced or even imagined. The next generation of Americans was not likely to raze the Jefferson Memorial or chip his face off Mount Rushmore, but the scholarly trend boded badly for Jefferson's reputation with posterity. As more Americans became aware of Jefferson as a slave-owning white racist, Onuf suggested, this flaw had the potential to trump all his virtues. The critical, even hostile, judgement of scholars was a preview of coming attractions in the larger popular culture.

In the October 1993 issue of The William and Mary Quarterly , the leading journal of early-American historians, Onuf suggested that the fascination with Jefferson's psychological complexity was gradually changing to frustration. The famous paradoxes that so intrigued poets, novelists and devotees of the "postmodern Jefferson" were beginning to look more like outright contradictions. The most glaring contradiction, his words in the Declaration of Independence as opposed to his lifelong ownership of slaves, was merely the most obvious disjunction between Jeffersonian rhetoric and Jeffersonian reality. Onuf described the emerging scholarly portrait of Jefferson as "a monster of self-deception," a man whose felicitous style was a bit too felicitous, concealing often incompatible ideals or dressing up platitudes as pieces of political wisdom that, as Onuf put it,"now circulate as the debased coin of our democratic culture." For Onuf, the multiple personalities of Jefferson were looking less like different facets of a Renaissance man and more like the artful disguises of a confidence man.

It occurred to me that the scholarly frustration Onuf described might derive from the realization that Jefferson's enigmatic character was never going to yield to conventional biographical or historical techniques (if, after all this time and effort, he remained the American Sphinx, well then, to hell with him). Onuf's point, on the other hand, was that a deconstructed Jefferson, a Jefferson divided into several disjoined selves that flickered into focus whenever convenient, then faded away whenever accountability was required, was hardly the stuff of a national hero. At some point, obliviousness stops looking like serenity and starts looking like hypocrisy.

With Jefferson, however, just when you think you have him cornered in an escape-proof room and are about to make an arrest, a trapdoor always seems to appear out of nowhere and he slips away to another adventure. The same week that I wrote the preceding paragraph, my eye came upon the following statement in boldface type in The New York Times Book Review : "Is your self shattered, your life riddled with inconsistency? Cheer up. That means you are resilient, postmodern."

This tongue-in-cheek observation was part of a serious review of a new book by Robert Jay Lifton called The Protean Self . The title echoed Merrill Peterson's description of Protean Jefferson, but with a new twist on its positive implications. Apparently Lifton, a prominent psychiatrist, was announcing that the new psychological ideal for the postmodern world was, in the reviewer's words, "a shapeshifter capable of assuming multiple identities without pathological fragmentation." In a world of jarring, unpredictable change, a world lacking clear borders between illusion and reality, with no shared sense of truth or morality, a premium was put on the ability to keep on the move inside yourself. The emerging psychological model was the "willful eclectic" who could live comfortably with contradictions.

This, of course, is a perfect description of Jefferson, or at least the version of Jefferson that scholars find so frustrating and, if Onuf is right, so reprehensible. But if Lifton is right, hypocrisy is an outmoded concept and Jefferson's disjointed personality is becoming the role model for postmodern society. (The trapdoor was opening again.) At any rate, I was grateful for Lifton's intriguing thesis because it helped me to understand what I meant when I used the term "postmodern." It also helped explain why poets, novelists and filmmakers are more favorably disposed toward Jefferson than scholars. They are more patient with and fascinated by Protean Jefferson because as artists they are more attuned to the interchangeable identities of the postmodern world.

Jefferson Today, A "Free-Floating Icon"

In the end, however, my thoughts returned to the faces of those ordinary Americans who had gathered at Worcester to celebrate Jefferson as their favorite Founding Father. They had absolutely no interest in deconstructing Jefferson or worshiping the disassembled parts of some engagingly incoherent hero. They were somewhat vulnerable, I suspect, to criticism of their idol as a racist. If the mounting scholarly case against Jefferson did filter down to the broader populace, it could do damage. But it seems clear to me that the deep reservoir of instinctive affection for Jefferson will probably remain intact. In its own way, the apparently unconditional love for Jefferson is every bit as mysterious as the enigmatic character of the man himself. Like a splendid sunset or a woman's beauty, it is simply there. It is the ultimate energy source for the Jeffersonian Surge.

Grass-roots Jeffersonianism, what we might also call Jeffersonian fundamentalism, has a long history of its own, but for our purposes its most instructive feature is the change in its character over the past 50 years. For most of American history, Jefferson was cast in the lead role in the dramatic clash between democracy and aristocracy, with Alexander Hamilton usually playing the opposite lead. If this dramatic formulation often had the suspicious odor of a soap opera, it also had the decided advantage of fitting neatly into the mainstream political categories and parties: It was the people against the interests, agrarians against the industrialists, the West against the East, Democrats against Republicans. Jefferson was one-half the American political dialogue, the liberal voice of "the many" holding forth against the conservative voice of "the few."

This version of American history always had the semifictional quality of an imposed plot line, but it stopped making much sense at all by the New Deal era, when Franklin Roosevelt invoked Hamiltonian methods (i.e., government intervention) to achieve Jeffersonians goals (i.e., economic equality). After the New Deal, most historians abandoned the Jefferson-Hamilton distinction altogether and most politicians stopped yearning for a Jeffersonian utopia free of all government influence. The disintegration of the old categories meant the demise of Jefferson as the symbolic leader of liberal partisans fighting valiantly against the entrenched interests. In a sense, what happened was that Jefferson ceased to function as the liberal half of the American political dialogue and became instead the presiding presence who stood above all political conflicts and parties.

And this, of course, is where he resides today, a kind of free-floating icon who hovers over the American political scene much like one of those dirigibles cruising above the Super Bowl, flashing words of encouragement to both teams. Formerly the property of liberal crusaders, he is now claimed by Democrats and Republicans alike. In fact, the most effective articulator of Jeffersonian rhetoric in the last half of the 20th century has been Ronald Reagan, the most conservative president since Calvin Coolidge, whose belief in less government, individual freedoms and American destiny came straight out of the Jeffersonian lexicon. Jefferson is not just an essential ingredient in the American political tradition, but the essence itself.

If you really press the issue, if you edit out all the extraneous voices and get to the core of Jefferson's thinking, the primal stuff consists of a single sentence of 35 simple words:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness .

These are the magic words of American history. To question them is to commit some combination of sacrilege and treason. Actually, they are not quite the words Jefferson first composed in June of 1776. His original draft, the pure Jeffersonian version of the message before editorial changes were made by the Continental Congress, makes it even clearer that Jefferson intended to express an essentially moral or spiritual vision:

We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness .

Two monumental claims are being made here, one explicit and the other implicit. The explicit claim is that the individual is the sovereign unit in society. His natural state is freedom and equality with all other individuals. This is the natural order of things. All restrictions on this natural order are illegal and immoral transgressions, violations of what God intended. The implicit claim is that the removal of those artificial and arbitrary restraints on individual freedom will release unprecedented amounts of energy into the world. The liberated individual will, in effect, interact with his fellows in a harmonious scheme that recovers the natural order and allows for the fullest realization of human potential.

Now if you say that these claims are wildly unrealistic and utopian, the kind of news that is just too good to be true, you would be completely correct. Jefferson was not a profound political thinker. As John Adams and James Madison sometimes tried to tell him, his efforts at political philosophy were often embarrassingly superficial and sometimes downright juvenile. But Jefferson was less a cogent or logical political thinker than a brilliant political theologian and visionary. The genius of his vision is first to propose that our deepest personal yearnings are in fact achievable, then to articulate opposing principles in a way that conceals their irreconcilability. Jefferson guards the American creed at an inspirational level, where all of us can congregate as individual Americans regardless of race, class or gender and speak the magic words together.

Here is the point where being a scholar and being an American divide. The natural instinct of the scholar is to pull Jefferson down from the high ground, to document the many ways that Jefferson himself failed to accept the full implications of his vision--slavery, racism and sexism are chief offenses--and to expose the inherent contradictions embedded within the creed.

The overwhelming feeling of ordinary Americans, however, is quite the opposite. That gathering of citizens in the Worcester church is illustrative. As they sat together in Jefferson's presence, they could simultaneously embrace the following propositions: that abortion is a woman's right, and than an unborn child cannot be killed; that health care for all Americans is a moral imperative, and that the government bureaucracies required to oversee health care (or welfare, or environmental protection) stifle individual freedom; that blacks and women (and gays and lesbians) cannot be denied their rights as citizens, and that affirmative-action programs are misguided violations of the egalitarian principle.

The Jeffersonian magic works because we permit it to function at a rarefied rhetorical level where real-world choices do not have to be made. As we segregate ourselves into a bewildering variety of racial, ethnic, gender and class categories, all defending our respective territories under the multicultural banner, there are precious few plots of common ground on which we can come together as Americans. Jefferson provides that space, which is actually not common ground at all, but a midair location floating above all the battle lines. In this Jefferson space we become, at least for a moment, an American chorus instead of an American cacophony.

What William James said about religious experience is also true for the Jeffersonian experience: If you have not had it, no one can explain it to you. But you do not need to be an American to feel the spirit move. In fact, the Jeffersonian Surge is probably stronger in parts of Central Europe than anywhere else. You could give a party for Jefferson in contemporary Gdansk, Prague or St. Petersburg and be pretty certain that an enthusiastic band of celebrants would show up seeking the same inspiration as those Worcester residents.