Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

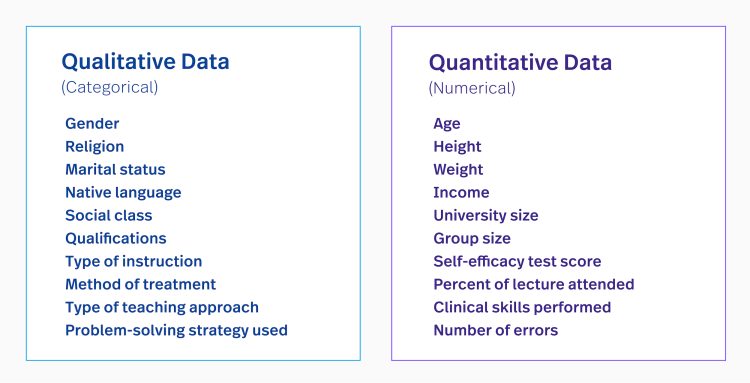

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

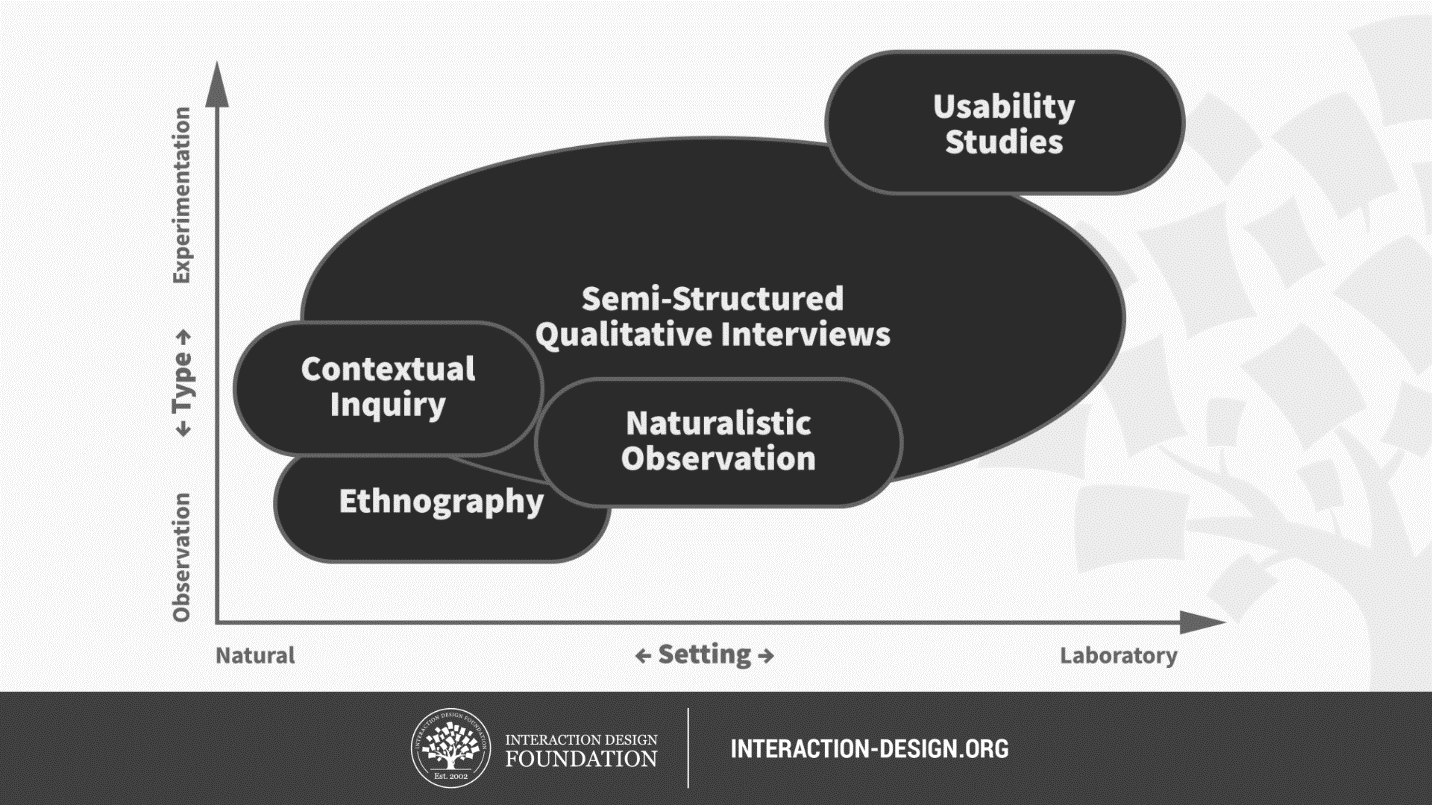

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

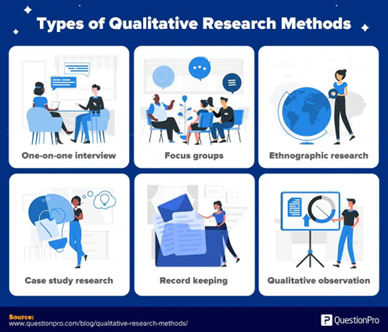

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

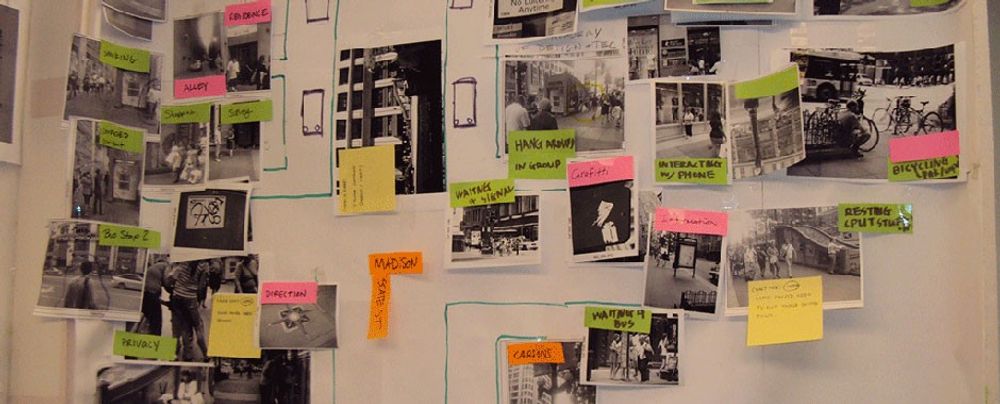

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

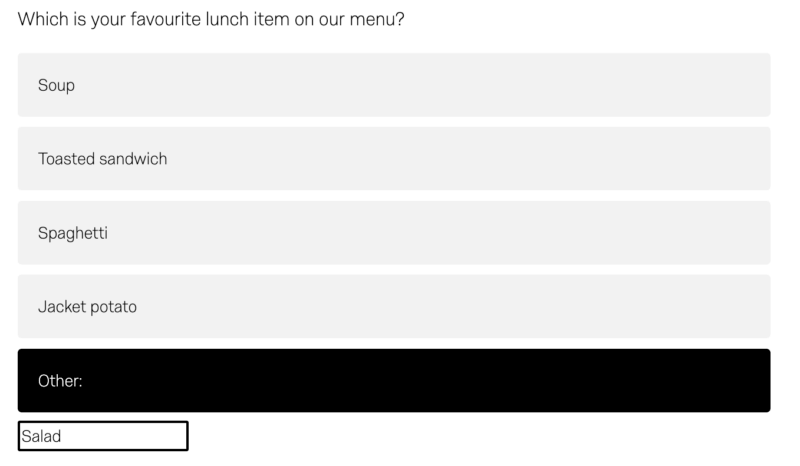

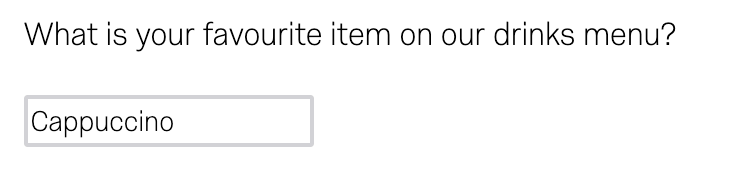

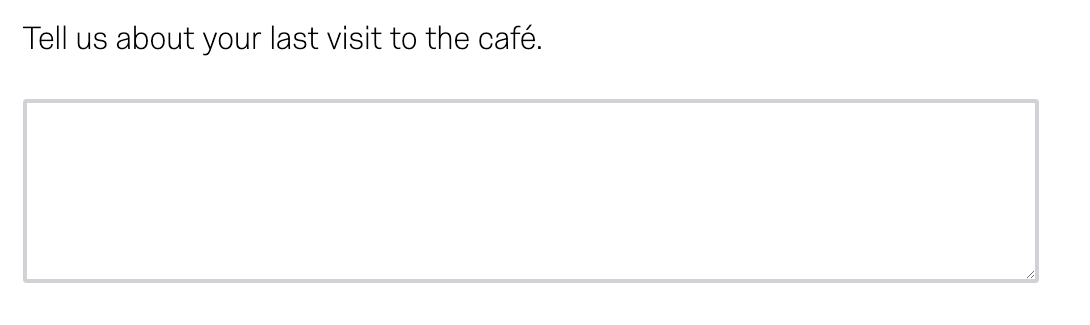

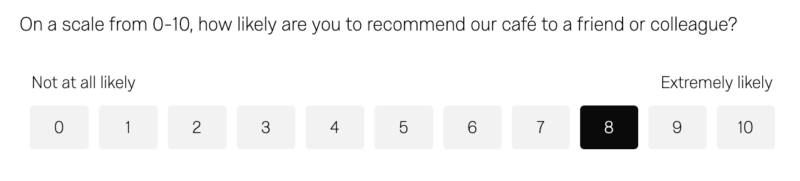

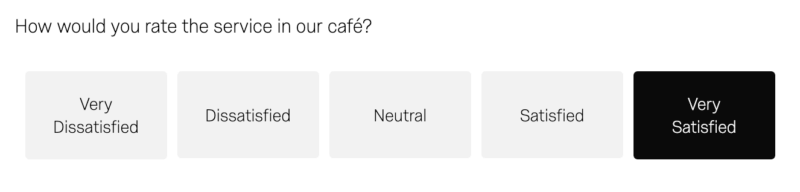

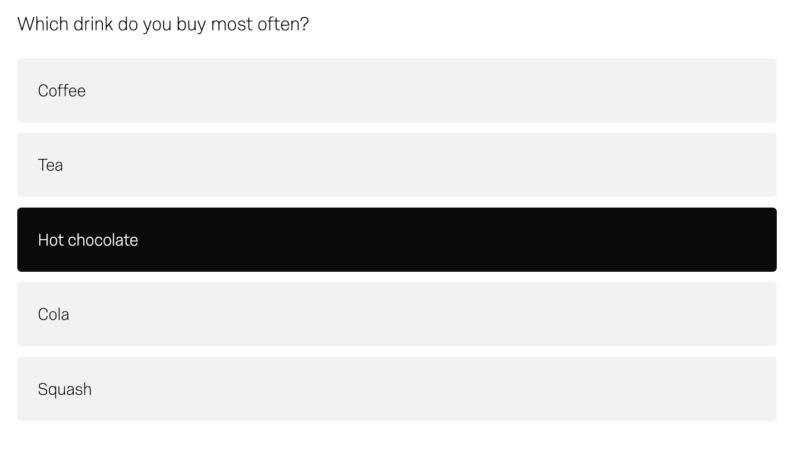

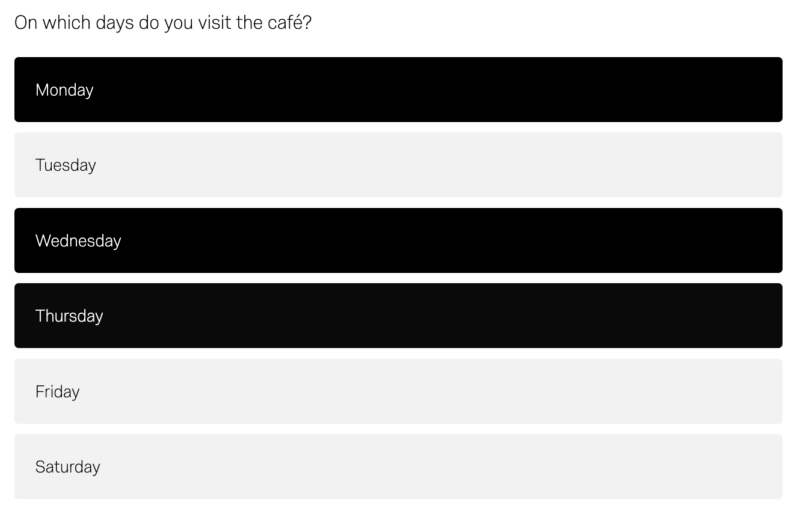

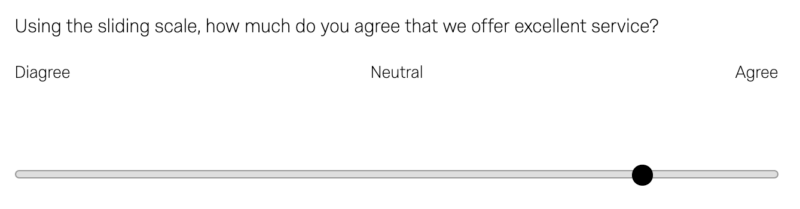

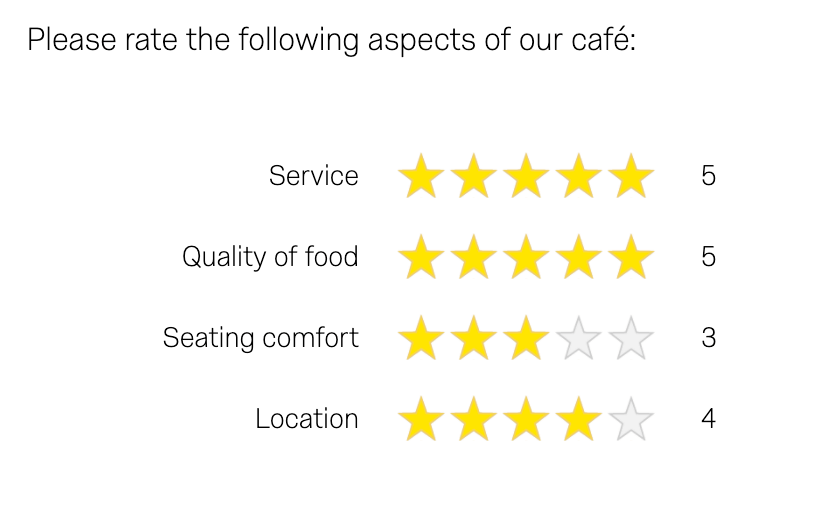

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

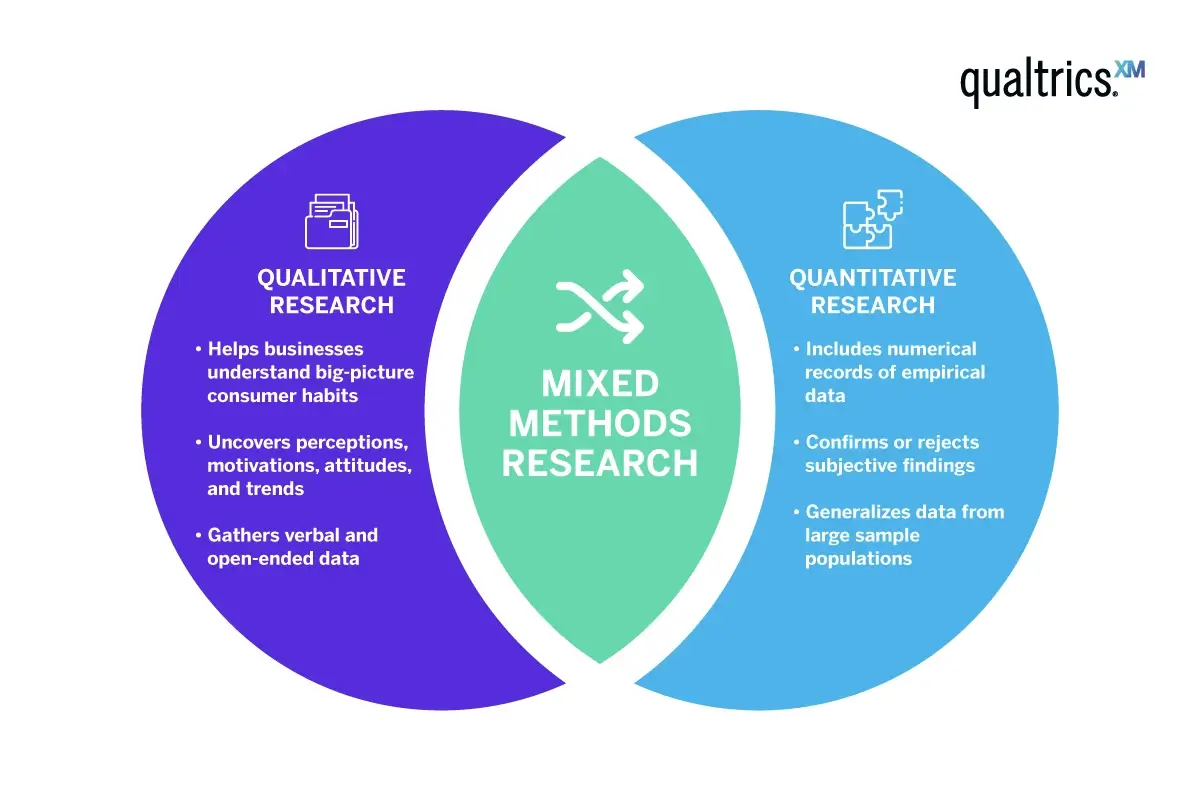

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

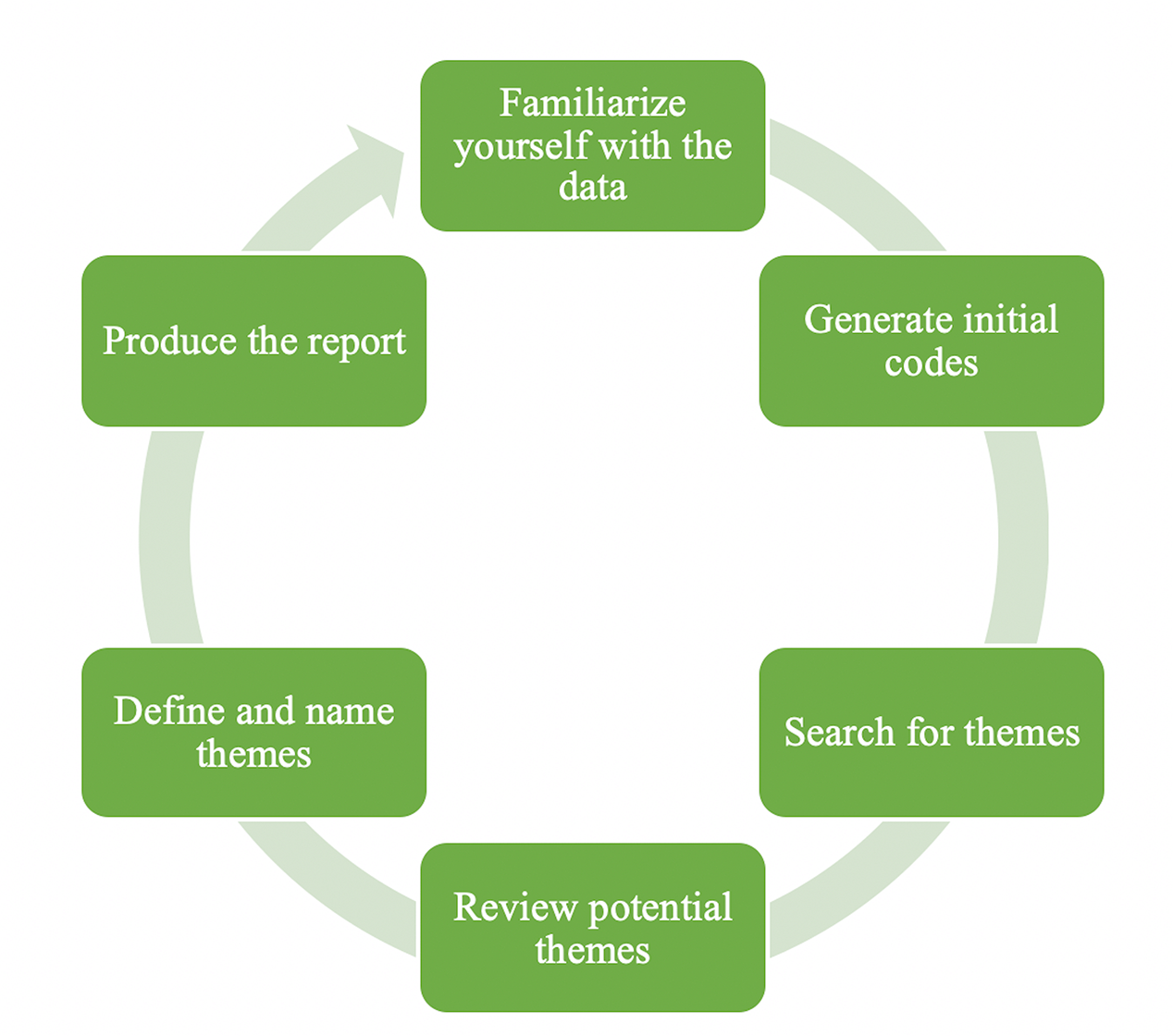

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

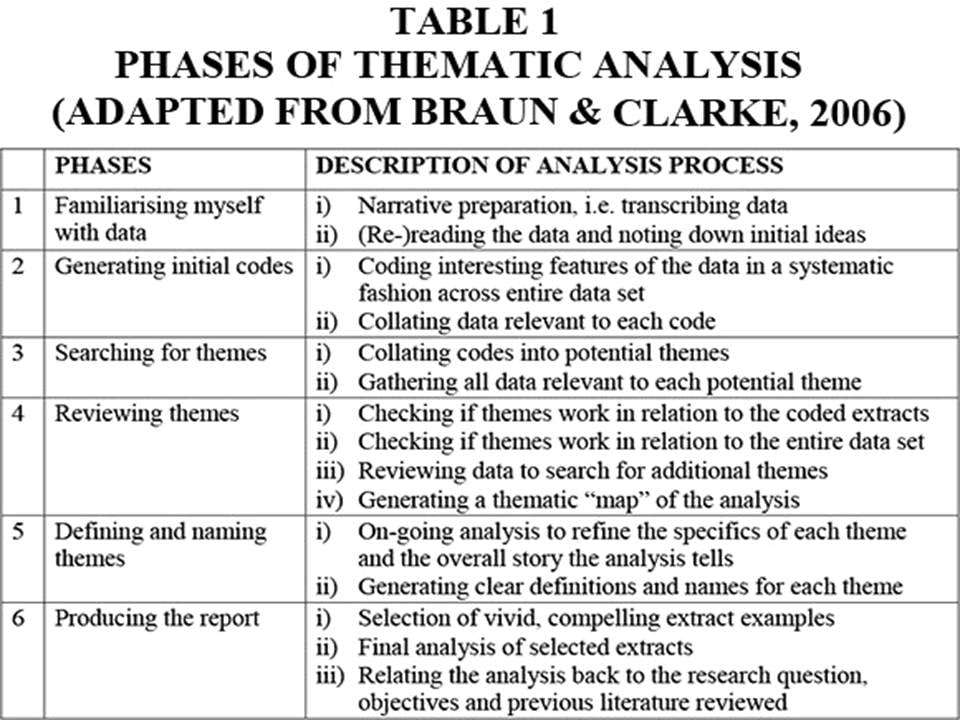

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

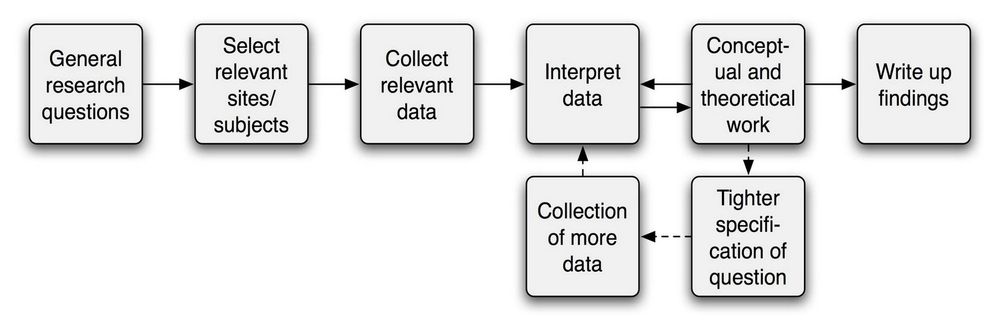

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analysing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analysing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalisability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalisable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labour-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organisation to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, January 30). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/introduction-to-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Qualitative Research? Methods, Types, Approaches and Examples

Qualitative research is a type of method that researchers use depending on their study requirements. Research can be conducted using several methods, but before starting the process, researchers should understand the different methods available to decide the best one for their study type. The type of research method needed depends on a few important criteria, such as the research question, study type, time, costs, data availability, and availability of respondents. The two main types of methods are qualitative research and quantitative research. Sometimes, researchers may find it difficult to decide which type of method is most suitable for their study. Keeping in mind a simple rule of thumb could help you make the correct decision. Quantitative research should be used to validate or test a theory or hypothesis and qualitative research should be used to understand a subject or event or identify reasons for observed patterns.

Qualitative research methods are based on principles of social sciences from several disciplines like psychology, sociology, and anthropology. In this method, researchers try to understand the feelings and motivation of their respondents, which would have prompted them to select or give a particular response to a question. Here are two qualitative research examples :

- Two brands (A & B) of the same medicine are available at a pharmacy. However, Brand A is more popular and has higher sales. In qualitative research , the interviewers would ideally visit a few stores in different areas and ask customers their reason for selecting either brand. Respondents may have different reasons that motivate them to select one brand over the other, such as brand loyalty, cost, feedback from friends, doctor’s suggestion, etc. Once the reasons are known, companies could then address challenges in that specific area to increase their product’s sales.

- A company organizes a focus group meeting with a random sample of its product’s consumers to understand their opinion on a new product being launched.

Table of Contents

What is qualitative research? 1

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data. The findings of qualitative research are expressed in words and help in understanding individuals’ subjective perceptions about an event, condition, or subject. This type of research is exploratory and is used to generate hypotheses or theories from data. Qualitative data are usually in the form of text, videos, photographs, and audio recordings. There are multiple qualitative research types , which will be discussed later.

Qualitative research methods 2

Researchers can choose from several qualitative research methods depending on the study type, research question, the researcher’s role, data to be collected, etc.

The following table lists the common qualitative research approaches with their purpose and examples, although there may be an overlap between some.

| Narrative | Explore the experiences of individuals and tell a story to give insight into human lives and behaviors. Narratives can be obtained from journals, letters, conversations, autobiographies, interviews, etc. | A researcher collecting information to create a biography using old documents, interviews, etc. |

| Phenomenology | Explain life experiences or phenomena, focusing on people’s subjective experiences and interpretations of the world. | Researchers exploring the experiences of family members of an individual undergoing a major surgery. |

| Grounded theory | Investigate process, actions, and interactions, and based on this grounded or empirical data a theory is developed. Unlike experimental research, this method doesn’t require a hypothesis theory to begin with. | A company with a high attrition rate and no prior data may use this method to understand the reasons for which employees leave. |

| Ethnography | Describe an ethnic, cultural, or social group by observation in their naturally occurring environment. | A researcher studying medical personnel in the immediate care division of a hospital to understand the culture and staff behaviors during high capacity. |

| Case study | In-depth analysis of complex issues in real-life settings, mostly used in business, law, and policymaking. Learnings from case studies can be implemented in other similar contexts. | A case study about how a particular company turned around its product sales and the marketing strategies they used could help implement similar methods in other companies. |

Types of qualitative research 3,4

The data collection methods in qualitative research are designed to assess and understand the perceptions, motivations, and feelings of the respondents about the subject being studied. The different qualitative research types include the following:

- In-depth or one-on-one interviews : This is one of the most common qualitative research methods and helps the interviewers understand a respondent’s subjective opinion and experience pertaining to a specific topic or event. These interviews are usually conversational and encourage the respondents to express their opinions freely. Semi-structured interviews, which have open-ended questions (where the respondents can answer more than just “yes” or “no”), are commonly used. Such interviews can be either face-to-face or telephonic, and the duration can vary depending on the subject or the interviewer. Asking the right questions is essential in this method so that the interview can be led in the suitable direction. Face-to-face interviews also help interviewers observe the respondents’ body language, which could help in confirming whether the responses match.

- Document study/Literature review/Record keeping : Researchers’ review of already existing written materials such as archives, annual reports, research articles, guidelines, policy documents, etc.

- Focus groups : Usually include a small sample of about 6-10 people and a moderator, to understand the participants’ opinion on a given topic. Focus groups ensure constructive discussions to understand the why, what, and, how about the topic. These group meetings need not always be in-person. In recent times, online meetings are also encouraged, and online surveys could also be administered with the option to “write” subjective answers as well. However, this method is expensive and is mostly used for new products and ideas.

- Qualitative observation : In this method, researchers collect data using their five senses—sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. This method doesn’t include any measurements but only the subjective observation. For example, “The dessert served at the bakery was creamy with sweet buttercream frosting”; this observation is based on the taste perception.

Qualitative research : Data collection and analysis

- Qualitative data collection is the process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research.

- The data collected are usually non-numeric and subjective and could be recorded in various methods, for instance, in case of one-to-one interviews, the responses may be recorded using handwritten notes, and audio and video recordings, depending on the interviewer and the setting or duration.

- Once the data are collected, they should be transcribed into meaningful or useful interpretations. An experienced researcher could take about 8-10 hours to transcribe an interview’s recordings. All such notes and recordings should be maintained properly for later reference.

- Some interviewers make use of “field notes.” These are not exactly the respondents’ answers but rather some observations the interviewer may have made while asking questions and may include non-verbal cues or any information about the setting or the environment. These notes are usually informal and help verify respondents’ answers.

2. Qualitative data analysis

- This process involves analyzing all the data obtained from the qualitative research methods in the form of text (notes), audio-video recordings, and pictures.

- Text analysis is a common form of qualitative data analysis in which researchers examine the social lives of the participants and analyze their words, actions, etc. in specific contexts. Social media platforms are now playing an important role in this method with researchers analyzing all information shared online.

There are usually five steps in the qualitative data analysis process: 5

- Prepare and organize the data

- Transcribe interviews

- Collect and document field notes and other material

- Review and explore the data

- Examine the data for patterns or important observations

- Develop a data coding system

- Create codes to categorize and connect the data

- Assign these codes to the data or responses

- Review the codes

- Identify recurring themes, opinions, patterns, etc.

- Present the findings

- Use the best possible method to present your observations

The following table 6 lists some common qualitative data analysis methods used by companies to make important decisions, with examples and when to use each. The methods may be similar and can overlap.

| Content analysis | To identify patterns in text, by grouping content into words, concepts, and themes; that is, determine presence of certain words or themes in some text | Researchers examining the language used in a journal article to search for bias |

| Narrative analysis | To understand people’s perspectives on specific issues. Focuses on people’s stories and the language used to tell these stories | A researcher conducting one or several in-depth interviews with an individual over a long period |

| Discourse analysis | To understand political, cultural, and power dynamics in specific contexts; that is, how people express themselves in different social contexts | A researcher studying a politician’s speeches across multiple contexts, such as audience, region, political history, etc. |

| Thematic analysis | To interpret the meaning behind the words used by people. This is done by identifying repetitive patterns or themes by reading through a dataset | Researcher analyzing raw data to explore the impact of high-stakes examinations on students and parents |

Characteristics of qualitative research methods 4

- Unstructured raw data : Qualitative research methods use unstructured, non-numerical data , which are analyzed to generate subjective conclusions about specific subjects, usually presented descriptively, instead of using statistical data.

- Site-specific data collection : In qualitative research methods , data are collected at specific areas where the respondents or researchers are either facing a challenge or have a need to explore. The process is conducted in a real-world setting and participants do not need to leave their original geographical setting to be able to participate.

- Researchers’ importance : Researchers play an instrumental role because, in qualitative research , communication with respondents is an essential part of data collection and analysis. In addition, researchers need to rely on their own observation and listening skills during an interaction and use and interpret that data appropriately.

- Multiple methods : Researchers collect data through various methods, as listed earlier, instead of relying on a single source. Although there may be some overlap between the qualitative research methods , each method has its own significance.

- Solving complex issues : These methods help in breaking down complex problems into more useful and interpretable inferences, which can be easily understood by everyone.

- Unbiased responses : Qualitative research methods rely on open communication where the participants are allowed to freely express their views. In such cases, the participants trust the interviewer, resulting in unbiased and truthful responses.

- Flexible : The qualitative research method can be changed at any stage of the research. The data analysis is not confined to being done at the end of the research but can be done in tandem with data collection. Consequently, based on preliminary analysis and new ideas, researchers have the liberty to change the method to suit their objective.

When to use qualitative research 4

The following points will give you an idea about when to use qualitative research .

- When the objective of a research study is to understand behaviors and patterns of respondents, then qualitative research is the most suitable method because it gives a clear insight into the reasons for the occurrence of an event.

- A few use cases for qualitative research methods include:

- New product development or idea generation

- Strengthening a product’s marketing strategy

- Conducting a SWOT analysis of product or services portfolios to help take important strategic decisions

- Understanding purchasing behavior of consumers

- Understanding reactions of target market to ad campaigns

- Understanding market demographics and conducting competitor analysis

- Understanding the effectiveness of a new treatment method in a particular section of society

A qualitative research method case study to understand when to use qualitative research 7

Context : A high school in the US underwent a turnaround or conservatorship process and consequently experienced a below average teacher retention rate. Researchers conducted qualitative research to understand teachers’ experiences and perceptions of how the turnaround may have influenced the teachers’ morale and how this, in turn, would have affected teachers’ retention.

Method : Purposive sampling was used to select eight teachers who were employed with the school before the conservatorship process and who were subsequently retained. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with these teachers. The questions addressed teachers’ perspectives of morale and their views on the conservatorship process.

Results : The study generated six factors that may have been influencing teachers’ perspectives: powerlessness, excessive visitations, loss of confidence, ineffective instructional practices, stress and burnout, and ineffective professional development opportunities. Based on these factors, four recommendations were made to increase teacher retention by boosting their morale.

Advantages of qualitative research 1

- Reflects real-world settings , and therefore allows for ambiguities in data, as well as the flexibility to change the method based on new developments.

- Helps in understanding the feelings or beliefs of the respondents rather than relying only on quantitative data.

- Uses a descriptive and narrative style of presentation, which may be easier to understand for people from all backgrounds.

- Some topics involving sensitive or controversial content could be difficult to quantify and so qualitative research helps in analyzing such content.

- The availability of multiple data sources and research methods helps give a holistic picture.

- There’s more involvement of participants, which gives them an assurance that their opinion matters, possibly leading to unbiased responses.

Disadvantages of qualitative research 1

- Large-scale data sets cannot be included because of time and cost constraints.

- Ensuring validity and reliability may be a challenge because of the subjective nature of the data, so drawing definite conclusions could be difficult.

- Replication by other researchers may be difficult for the same contexts or situations.

- Generalization to a wider context or to other populations or settings is not possible.

- Data collection and analysis may be time consuming.

- Researcher’s interpretation may alter the results causing an unintended bias.

Differences between qualitative research and quantitative research 1

| Purpose and design | Explore ideas, formulate hypotheses; more subjective | Test theories and hypotheses, discover causal relationships; measurable and more structured |

| Data collection method | Semi-structured interviews/surveys with open-ended questions, document study/literature reviews, focus groups, case study research, ethnography | Experiments, controlled observations, questionnaires and surveys with a rating scale or closed-ended questions. The methods can be experimental, quasi-experimental, descriptive, or correlational. |

| Data analysis | Content analysis (determine presence of certain words/concepts in texts), grounded theory (hypothesis creation by data collection and analysis), thematic analysis (identify important themes/patterns in data and use these to address an issue) | Statistical analysis using applications such as Excel, SPSS, R |

| Sample size | Small | Large |

| Example | A company organizing focus groups or one-to-one interviews to understand customers’ (subjective) opinions about a specific product, based on which the company can modify their marketing strategy | Customer satisfaction surveys sent out by companies. Customers are asked to rate their experience on a rating scale of 1 to 5 |

Frequently asked questions on qualitative research

Q: how do i know if qualitative research is appropriate for my study .

A: Here’s a simple checklist you could use:

- Not much is known about the subject being studied.

- There is a need to understand or simplify a complex problem or situation.

- Participants’ experiences/beliefs/feelings are required for analysis.

- There’s no existing hypothesis to begin with, rather a theory would need to be created after analysis.

- You need to gather in-depth understanding of an event or subject, which may not need to be supported by numeric data.

Q: How do I ensure the reliability and validity of my qualitative research findings?

A: To ensure the validity of your qualitative research findings you should explicitly state your objective and describe clearly why you have interpreted the data in a particular way. Another method could be to connect your data in different ways or from different perspectives to see if you reach a similar, unbiased conclusion.

To ensure reliability, always create an audit trail of your qualitative research by describing your steps and reasons for every interpretation, so that if required, another researcher could trace your steps to corroborate your (or their own) findings. In addition, always look for patterns or consistencies in the data collected through different methods.

Q: Are there any sampling strategies or techniques for qualitative research ?

A: Yes, the following are few common sampling strategies used in qualitative research :

1. Convenience sampling

Selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

2. Purposive sampling

Participants are grouped according to predefined criteria based on a specific research question. Sample sizes are often determined based on theoretical saturation (when new data no longer provide additional insights).

3. Snowball sampling

Already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.

4. Quota sampling

While designing the study, the researchers decide how many people with which characteristics to include as participants. The characteristics help in choosing people most likely to provide insights into the subject.

Q: What ethical standards need to be followed with qualitative research ?

A: The following ethical standards should be considered in qualitative research:

- Anonymity : The participants should never be identified in the study and researchers should ensure that no identifying information is mentioned even indirectly.

- Confidentiality : To protect participants’ confidentiality, ensure that all related documents, transcripts, notes are stored safely.

- Informed consent : Researchers should clearly communicate the objective of the study and how the participants’ responses will be used prior to engaging with the participants.

Q: How do I address bias in my qualitative research ?

A: You could use the following points to ensure an unbiased approach to your qualitative research :

- Check your interpretations of the findings with others’ interpretations to identify consistencies.

- If possible, you could ask your participants if your interpretations convey their beliefs to a significant extent.

- Data triangulation is a way of using multiple data sources to see if all methods consistently support your interpretations.

- Contemplate other possible explanations for your findings or interpretations and try ruling them out if possible.

- Conduct a peer review of your findings to identify any gaps that may not have been visible to you.

- Frame context-appropriate questions to ensure there is no researcher or participant bias.

We hope this article has given you answers to the question “ what is qualitative research ” and given you an in-depth understanding of the various aspects of qualitative research , including the definition, types, and approaches, when to use this method, and advantages and disadvantages, so that the next time you undertake a study you would know which type of research design to adopt.

References:

- McLeod, S. A. Qualitative vs. quantitative research. Simply Psychology [Accessed January 17, 2023]. www.simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html

- Omniconvert website [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://www.omniconvert.com/blog/qualitative-research-definition-methodology-limitation-examples/

- Busetto L., Wick W., Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice [Accessed January 19, 2023] https://neurolrespract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42466-020-00059

- QuestionPro website. Qualitative research methods: Types & examples [Accessed January 16, 2023]. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/qualitative-research-methods/

- Campuslabs website. How to analyze qualitative data [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://baselinesupport.campuslabs.com/hc/en-us/articles/204305675-How-to-analyze-qualitative-data

- Thematic website. Qualitative data analysis: Step-by-guide [Accessed January 20, 2023]. https://getthematic.com/insights/qualitative-data-analysis/

- Lane L. J., Jones D., Penny G. R. Qualitative case study of teachers’ morale in a turnaround school. Research in Higher Education Journal . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1233111.pdf

- Meetingsnet website. 7 FAQs about qualitative research and CME [Accessed January 21, 2023]. https://www.meetingsnet.com/cme-design/7-faqs-about-qualitative-research-and-cme

- Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Khoury College of Computer Sciences. Northeastern University. https://course.ccs.neu.edu/is4800sp12/resources/qualmethods.pdf

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Researcher.Life All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 21+ years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

What is Research? Definition, Types, Methods, and Examples

Turabian Format: A Beginner’s Guide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed, qualitative study, affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Disclosure: Steven Tenny declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Janelle Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Grace Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Similar articles

- Public sector reforms and their impact on the level of corruption: A systematic review. Mugellini G, Della Bella S, Colagrossi M, Isenring GL, Killias M. Mugellini G, et al. Campbell Syst Rev. 2021 May 24;17(2):e1173. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1173. eCollection 2021 Jun. Campbell Syst Rev. 2021. PMID: 37131927 Free PMC article. Review.

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, Moraleda C, Rogers L, Daniels K, Green P. Crider K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1;2(2022):CD014217. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014217. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36321557 Free PMC article.

- Suicidal Ideation. Harmer B, Lee S, Rizvi A, Saadabadi A. Harmer B, et al. 2024 Apr 20. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. 2024 Apr 20. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 33351435 Free Books & Documents.

- Evidence Brief: The Effectiveness Of Mandatory Computer-Based Trainings On Government Ethics, Workplace Harassment, Or Privacy And Information Security-Related Topics [Internet]. Peterson K, McCleery E. Peterson K, et al. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2014 May. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2014 May. PMID: 27606391 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Macromolecular crowding: chemistry and physics meet biology (Ascona, Switzerland, 10-14 June 2012). Foffi G, Pastore A, Piazza F, Temussi PA. Foffi G, et al. Phys Biol. 2013 Aug;10(4):040301. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/10/4/040301. Epub 2013 Aug 2. Phys Biol. 2013. PMID: 23912807

- Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: Introduction. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017 Dec;23(1):271-273. - PMC - PubMed

- Cleland JA. The qualitative orientation in medical education research. Korean J Med Educ. 2017 Jun;29(2):61-71. - PMC - PubMed

- Foley G, Timonen V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015 Aug;50(4):1195-210. - PMC - PubMed

- Devers KJ. How will we know "good" qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;34(5 Pt 2):1153-88. - PMC - PubMed

- Huston P, Rowan M. Qualitative studies. Their role in medical research. Can Fam Physician. 1998 Nov;44:2453-8. - PMC - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in PubMed

- Search in MeSH

- Add to Search

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- NCBI Bookshelf

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- I NEED TO . . .

- What is Quantitative Research?

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Quantitative vs Qualitative

- Step 1: Accessing CINAHL

- Step 2: Create a Keyword Search

- Step 3: Create a Subject Heading Search

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Second Concept

- Step 5: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Quantitative Terms

- Step 6: Combining All Searches

- Step 7: Adding Limiters

- Step 8: Save Your Search!

- What Kind of Article is This?

- More Research Help This link opens in a new window

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a process of naturalistic inquiry that seeks an in-depth understanding of social phenomena within their natural setting. It focuses on the "why" rather than the "what" of social phenomena and relies on the direct experiences of human beings as meaning-making agents in their every day lives. Rather than by logical and statistical procedures, qualitative researchers use multiple systems of inquiry for the study of human phenomena including biography, case study, historical analysis, discourse analysis, ethnography, grounded theory, and phenomenology.

University of Utah College of Nursing, (n.d.). What is qualitative research? [Guide] Retrieved from https://nursing.utah.edu/research/qualitative-research/what-is-qualitative-research.php#what

The following video will explain the fundamentals of qualitative research.

- << Previous: What is Quantitative Research?

- Next: Quantitative vs Qualitative >>

- Last Updated: Jun 12, 2024 8:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/quantitative_and_qualitative_research

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility