- Contributors

- Search Write + Enter --> -->

- The RSS feed for this twitter account is not loadable for the moment.

Follow @modescriticism on twitter.

Learning Design Histories for Design Futures: Speculative Histories and Reflective Practice

The conceptual frameworks that influence historical accounts also influence speculation about the future. In this respect, history and futurology share a subtle affinity. They are both children of the moving present (Buchanan, 2001, p. 73).

The affinity between histories and futures has always been a central concern of my teaching, research and practice. I might use different terms according to the context—heritage and innovation in museums or design history and design futuring in education—but I share with Richard Buchanan a desire for a robust design culture in the present that makes a sustainable contribution to humanity’s future. This essay takes the form of a reflection on my own practice as a design teacher, and discusses the value of speculative history for design students, as well as a recent example in practice. The educational case study is based on a paper I presented at the first Teaching Design History workshop organised by the Design History Society in 2010, which coincided with the launch of the Design History Reader (2010) by Grace Lees-Maffei. Having taught design history, criticism and theory for seven years in the Design Studies Department at the University of Otago in New Zealand, it was gratifying to see a relatively comprehensive published reader that bore some resemblance to the various readers I had compiled for undergraduate courses. However, talking to the design history teachers, I became aware for the first time about a tension that existed in the UK between the teaching of design history and its relationship to studio practice. Since being made compulsory in tertiary education in the UK in the 1970s, design history had grown to be an established discipline (or, at least, sub-discipline of history), but there was a perception amongst students that it lacked relevance to studio practice, or at least had become divorced from it due to different methods of delivery and outcomes (studio vs lecture, design vs essay). While this did not necessarily coincide with my own experience, it did make me consider the relationship of history and practice in tertiary design education.

The relationship of history, theory and criticism to practice is frequently debated in design, as it is in many other disciplines with demanding professional practices. However, design’s prescriptive, projective and prospective orientation often sees history relegated to educational outsider status, confined to the lecture theatre and excluded from the studio. In other words, there is a perception that too much emphasis on descriptive, critical and retrospective analysis of design hinders innovation, and so an artificial divide is maintained: History is the object of formal disciplined and critical study, not the subject of practice. History is dead and inevitable; design is alive and unpredictable. There are, however, many notable examples where this is not the case: Design Studies was initially proposed by Paul Rand during a visit to Carnegie Mellon in the 1970s as a series of courses to help students reflect on and understand the principles of design; Philip Meggs’ monumental History of Graphic Design (1983) was researched and designed with his students, and in New Zealand, typographer Kris Sowersby of Klim Type Foundry is amongst those type designers who make extensive use of 18th and 19th century type specimens to refine and develop his remarkable 21st century type designs.

Reflective Practice In my case, the primary motivations of design history still remain: to create an adequate critical history of design in New Zealand as both a contribution to national history and global histories of design. However, my primary role as a design historian is not to educate the next generation of design historians, but to educate critical, creative and reflective design practitioners, as well as to sustain research-informed design practice within an interdisciplinary Design Studies undergraduate programme. It is for these reasons that I introduce design history as a fundamental design research process. If students can master the basic methods of historical scholarship, they are prepared for more advanced design research methods.

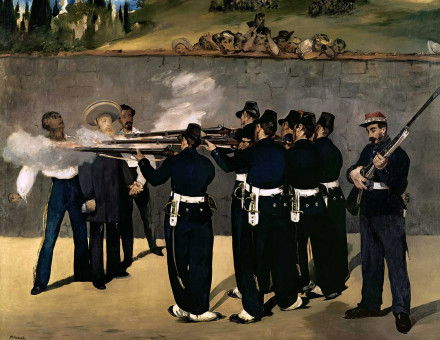

Speculative Histories Called by a number of different names—allohistory, counterfactuals, alternative, speculative or virtual histories—this particular method of design history proposes ‘what-if’ scenarios about the past. Anyone who has reviewed the finalists in a design competition after the winner has been announced will probably have begun such a speculation about what might have been. While the method gained academic credibility in the 1990s with the publication of Geoffrey Hawthorn’s Plausible Worlds (1991) and Niall Ferguson’s Virtual History (1997), many historians argue that considering alternative course of action available to historical actors at a given historical moment has always been a tacit part of historical analysis. In order for historians to develop arguments why certain decisions were made, they had to consider what other options were open to the historical agents. In practice, this means the basic research question changes from ‘What happened and why?’ to ‘What might have happened and why it did not?’, or in cases of individual design ‘could someone have acted differently?’

This mode of inquiry is premised on the idea that history is dynamic and contingent, and very few human decisions are inevitable. It also has the effect of returning a sense of agency to historical actors and facilitates empathy and deeper understanding of the historical choices made, as well as ethical consideration of consequences. However, it is important that the imaginative premise is supported by empirical means, and that some form of hypothesis has to be developed and tested against contemporary evidence of what alternatives were actually considered at a given historical moment. This entails identifying key decisions and turning points in the past, taking account of prevailing conditions, and providing plausible explanations for alternative courses of action. It is therefore a disciplined creativity that supports critical analysis and consideration of narrative structure. Steven Weber has also described speculative histories as “mind-set changers” (Weber, 1996, p. 270) in that they encourage open-mindedness to alternative historical interpretations and the implications of historical events.

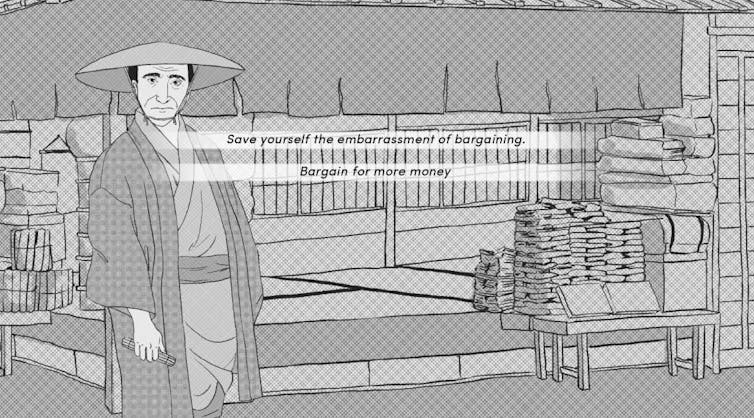

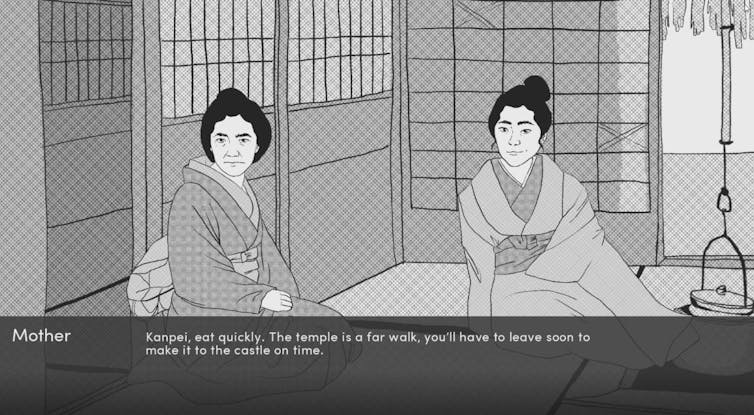

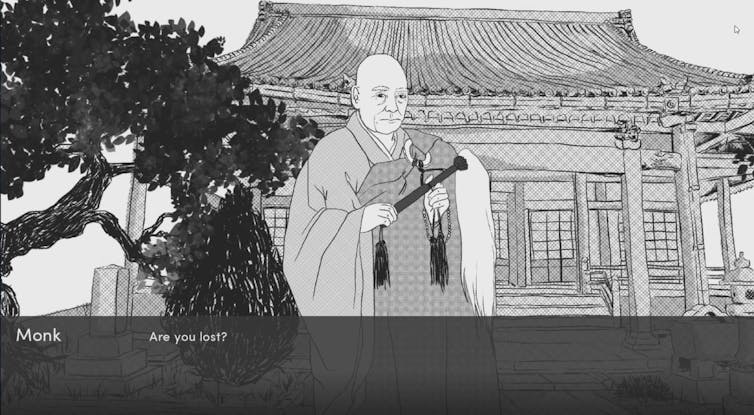

Speculative Histories in Teaching Practice To some degree my motivation in introducing speculative histories to design education was to change students’ perception about the value and relevance of history and its methods. The method explicitly introduces a creative element into critical inquiry, encouraging students to consider and develop alternative interpretations. At a more fundamental level, reconstituting history in this way encourages students to reframe problems in general and be critical of assumptions, especially historical ones. As well as reimagining the past, it also affords design opportunities to visually represent the alternative history.

In 2009, I changed the Foresight (futures) assignment to Allosight (the prefix allo- is from the Greek for ‘different, other’). Students had already completed a piece of design history research (Hindsight), and had applied the basic principles and methods of design history (as set out in John Walker’s Design History and the History of Design). They were then asked to select a significant design, decision, incident or event from two general histories of design and one New Zealand design history, and write a short factual summary of 500 words supported by a single photograph, before creating a speculative history of 1500 words. What struck me was the enthusiasm for, and extra effort into the assignment and the diversity of topics chosen. These ranged from changes to the design of the Berlin Wall, a reversal of results in the 1954 World Cup football final, Al Gore’s election as President, America without Bauhaus designers, and our local cityscape without a controversial sports stadium. Each considered the effects of change, including the effectiveness of the design of the Berlin Wall in separating people, the effect of sport championships on brand value, sustainability, American design education, and public funding of sports stadia. Many assignments redesigned artefacts and media from the past to simulate accurate historical communication of their alternative history. Two particularly notable student examples can be highlighted: architect Richard Neutra’s modernist public housing project for Elysian Park Heights in Chavez Ravine in Los Angeles, and the early death of fashion designer Christian Dior. The first student’s interest in Neutra was sparked from his previous Hindsight assignment of Neutra’s Case Study Houses (1945–1966). By considering the plans for Elysian Park Heights and its implementation, he discussed a plausible gentrification and displacement of people it had been intended for. The second student considered what if Christian Dior had lived past 1957, and her Allosight project lead to a fourth-year dissertation on the importance of succession planning in fashion brand identities built around a single name.

In his book Design Futuring (2009), Tony Fry states that “Looking back teaches ways to think about how to project forward. It can be a way to formulate key questions and to create ‘critical fictions’, enabling the contemplation of what would otherwise not be considered” (Fry, 2009, p. 39). From my experience, speculative history is a challenging and sophisticated method which encourages design students to reflect upon about the nature of history, question received interpretations, identify and empathise with challenges faced by historical figures, simulate alternatives and develop coherent narratives. Below are summarised some of its core learning benefits for those interested in incorporating the method within their design teaching:

· Supports critical research and tests deductive reasoning skills; · Challenges the assumption of the inevitability of history; · Supports understanding of the significance of human agency; · Provides an opportunity to apply graphic design to history; · Requires careful consideration of narrative formation; · Introduces scenario building into design history, the relationships of driving forces, and the importance of plausibility as a test of scenarios; · The exploration of the past, discovery of alternative interpretations, and prototyping alternative histories relates well to the three stages (Exploration, Discovery and Prototyping) of participatory design as set out by Spinuzzi (2005) · Identifies social issues and analyses the ethical consequences of decision-making; · Provides an opportunity for disciplined creativity. In terms of my teaching, the main challenge lay in defining and selecting topics that are supported by a breadth of secondary research while, for students, identifying key turning points and evidence of historically plausible alternatives requires careful attention to the literature. In my experience, the benefits outweighed these challenges and the results aligned well with the first two levels of Futures Literacy as set out by Miller (2007), awareness and discovery. Awareness consists of developing temporal and situational awareness ‘that change happens over time, that people do harbour expectations and values, and that choices matter’ (Miller, 2007, p. 348), while discovery involves ‘consistently distinguishing between possible, probable and preferable’ futures to encourage a ‘rigorous imagining’ (Miller, 2007, p. 350) of possible scenarios to inform strategic decision-making. What I saw in students who used speculative histories was a greater awareness of their present-day assumptions and a genuine pleasure in the nuanced process of discovery the method entailed.

Back to the Future In both theory and practice, speculative histories provide a healthy challenge to orthodox thinking. Speculative histories reveal an important aspect of creative thinking that informs historical research—the importance of inquiry-led discovery, the active possibility of human agency, and the potential for the reinterpretation of history—and, in my experience, its application by design students encourages a more active interest in design historical research and a clearer understanding of its relationship to, and potential for design practice. It also offers a safe historical laboratory in which to test out and critically evaluate hypothetical scenarios and their consequences which brings us back to the present needs of design education and, in the case of New Zealand, the future of that country’s flag.

— Bibliography Buchanan, R. (2001) Children of the Moving Present: The Ecology of Culture and the Search for Causes in Design. In: Design Issues 17.1, pp. 67–84. Ferguson, N. (ed.) (1997). Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals. London: Picador. Fry, T. (2008) Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice. Oxford: Berg. Gilson, E. (1938) The Unity of Philosophical Experience. London: Sheed & Ward. Hawthorn, G. (1991) Plausible Worlds: Possibility and Understanding in History and the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kaye, Simon T. (2010) Challenging Certainty: The Utility and History of Counter-factualism. In: History and Theory 49, pp. 38–57. Lebow, R. (2000) What’s So Different About A Counterfactual? In: World Politics 52, pp. 550–585. Levine, S. (ed.), (2006) New Zealand As It Might Have Been. Wellington: Victoria University Press. Levine, S. (ed.), (2010) New Zealand As It Might Have Been 2. Wellington: Victoria University Press. Miller, R. (2007) Futures Literacy: A Hybrid Strategic Scenario Method. In: Futures 39.4, pp. 341–362. Spinuzzi, C. (2005) The Methodology of Participatory Design. In: Technical Communication 52.2, pp. 163–74. Walker, J. A. (1989) Varieties of Design History. In: Design History and the History of Design. London: Pluto. pp. 99–152. Weber, S. (1996) Counterfactuals, Past and Future. In: Tetlock, P. & Belkin, A. (eds.), Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological, and Psychological Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 268–288.

— Essay originally published in Modes of Criticism 2 – Critique of Method (2016).

[ + ]

| 1 | The French philosopher and historian Étienne Gilson is widely attributed with saying “History is the only laboratory we have in which to test the consequences of thought.” |

| 2 | See: In: . |

| 3 | See: In: New Zealand Government. |

Click to Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 (page 8) p. 8 The historical evolution of design

- Published: June 2005

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The human capacity to design has remained constant even though its means and methods have altered, in parallel to technological, organizational, and cultural changes. ‘The historical evolution of design’ argues that design, although a unique and unchanging skill, has manifested itself in different ways throughout time. The diversity of concepts and practices in modern design is explained by the layered nature of the evolution of design. It is difficult to determine exactly when humans began to change their environment to a significant degree, or in other words to design. Whose interest will design serve in the future? How will design cope with challenges of operating in a more globalized space?

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 8 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 15 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 9 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 8 |

| August 2023 | 5 |

| September 2023 | 7 |

| October 2023 | 30 |

| November 2023 | 15 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 7 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 12 |

| April 2024 | 25 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline

(2 reviews)

Stephanie Cole, Arlington, Texas

Kimberly Breuer, Arlington, Texas

Scott W. Palmer, Arlington, Texas

ISBN 13: 9781648160066

Publisher: Mavs Open Press

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Ingo Heidbrink, Professor of History, Old Dominion University on 5/22/24

The book covers successfully the basic methods of historical research and writing. It has been prepared as a textbook for the methods classes at the University of Texas, Arlington (UTA) and therefore is focusing especially on methods that are of... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The book covers successfully the basic methods of historical research and writing. It has been prepared as a textbook for the methods classes at the University of Texas, Arlington (UTA) and therefore is focusing especially on methods that are of importance to the historical course offerings at UTA, but also provides a highly comprehensive overview of the standard methodology taught at any department of history throughout the US and around the globe. Overall, it discusses the complete process of historical research from source selection, critique and analysis to the process of historical writing and preparation of other means of communication of historical research to academic and non-academic audiences. It needs to be highlighted, that the book begins with an introduction to the different types of reading as a critical skill for all historical research, but also includes some brief chapters on the use of GIS systems, oral history, data-bases etc. and thus covers the standard set of methods most historians will use today. Nevertheless, it needs to be mentioned, that specialised methods like for example the whole range of quantitative methods typically used by economic historians are more or less completely neglected, but this seems to be very much acceptable, as the book is written as a basic textbook for students of history regardless of field of specialisation and not as a dedicated higher-level methods publication for a particular sub-field of historical research.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The description of methodology and writing practice follows the broadly accepted standards of historical research in the US. While the text is accurate, seems to be error-free, and unbiased, it needs to be mentioned, that all textbooks focusing on historical method will only present some but not all potential methods and that the selection of which methods are included or excluded is always depending on the authors and their take on historical research. But as the book is mainly dealing with the basic mechanics of historical research and writing on which nearly all historians agree, this is a minor issue.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

As the book is mainly dealing with the basic standard methodology of historical research and writing, the risk of the main parts of the book becoming outdated or obsolete is extremely low or to a certain degree not existing. After all, while historical method has improved substantially over the last decades, the fundamentals of reading, source critique and analysis, and historical writings remained valid. Some of the chapters dealing with specific methods like the use of GIS systems might become outdated at a certain time, but as they are presented as individual chapters, these chapters can easily be exchanged if needed. If the authors might decide that it would be useful to add additional chapters on other (new) methods, they can easily be integrated into the book and thus it is unlikely that the book will become outdated in the foreseeable future. When it comes to relevance at large, the book is covering a topic of utmost relevance, as it provides a comprehensive and easily accessible to the main methods and skills for any historian and thus a topic that is fundamental for the discipline and any student of history.

Clarity rating: 4

The book is written as a textbook with undergraduate students in mind as the target readership. Therefore it needs to be lauded that the amount of discipline specific jargon and/or discipline specific terminology is limited, but on the other hand, it can also be criticised that the amount of discipline specific terminology introduced in the book is limited. Analytical historical research regularly requires very precise wording and it would have been helpful if the book would have introduced more of the typical canon of terminology used by professional historians.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is consistent in terms of the terminology used throughout the book and it can be clearly seen that the authors and spend a lot of effort on generating this consistency.

Modularity rating: 5

The book has a certain degree of modularity and individual chapters can be easily assigned as a reading when using the book as a textbook. All individual chapters have a length that they can easily be assigned as a reading from one class session to the next. If the book might be assigned as an additional textbook in a thematic history course, individual chapters of the book that are of special relevance for this course can be easily assigned without the students needing to read anything beyond the chapter to understand the content that is required for that particular class.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The book is basically organised along the flow of historical research, which seems to be the most logical approach for any textbook on historical methods and historical writing.

Interface rating: 4

The text is largely free from interface issues, but the pdf version is suffering from some issues with the few pages in landscape format. Navigation within the book is basic but functional and appropriate

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

The text does not seem to contain any major grammatical errors

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

While the book is using some examples that are inclusive of races, ethnicities, and backgrounds, it needs to mentioned, that the book is highly US focused. On the one hand this is not a major issue as the examples chosen does not really matter when it comes to a discussion of methods, but it might limit the usability or at least the attractivenes of the book outside the US.

Having taught historical methods class for two decades, I never found a textbook that fulfilled all my needs and. thus worked mainly with individually assigned materials and texts instead of a textbook. Although this book is also not the perfect textbook for me, I'll consider introducing the book to my methods classes as it comes as an open textbook and thus without cost to the students. Furthermore, it seems to me that this book is a very solid example or base for the development of department specific historical method textbooks at individual departments of history throughout the US.

Reviewed by Ramon Jackson, Assistant Professor of History, Newberry College on 11/4/22

This textbook was developed for HIST 3300, a history research methods course at the University of Texas-Arlington. The course doubles as a substitute for UNIV 1101, the freshman "College Life" seminar. The authors offer useful, comprehensive... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This textbook was developed for HIST 3300, a history research methods course at the University of Texas-Arlington. The course doubles as a substitute for UNIV 1101, the freshman "College Life" seminar. The authors offer useful, comprehensive chapters on thinking, researching, writing, and performing historically as well as useful supplementary sections that offer tips for student success while in college. There are also excellent appendices that discuss how to develop and utilize databases in historical research. An issue is that the textbook was developed for UTA students which means that certain information will not apply to those outside of that university system.

How History is Made offers practical advice for undergraduate and graduate History students and continuing scholars alike. It accurately and concisely documents the evolution of the historical profession and outlines how students can utilize the training provided in History courses and programs as future professionals. The authors provide numerous examples of how race and ethnicity have shaped academic and Public History but sometimes fall short of providing readers with an understanding of how specific skills such as oral history may be more difficult to apply in Black and marginalized communities or the obstacles one may face as minorities within the profession.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Substantial sections of the information offered in this textbook are timeless, specifically the sections that instruct students about how to think, research, write, and perform historically. The chapters on "Digital History" and Public History may need to be revised later due to increased participation and innovation in these fields. Instructors outside of the UTA system will need to supplement the use of this book with their own research and writing activities and versions of parts VI-VIII to provide skills, resources, and advice for future graduates that best reflect conditions on their own campuses.

The authors did a fine job of providing readers with an accessible, concise, and useful textbook that examines the history of the historical profession and provides useful strategies, skills, and resources for success in the field. Minor grammatical errors and occasional formatting issues obstructed the flow of specific chapters but, overall, the authors made a compelling case for the value of historical thought, research, and writing among undergraduate students and future professionals in every discipline.

Consistency rating: 4

The text is consistent and avoids jargon, slang, and other unnecessary mistakes that would distract or confuse readers. How History is Made is accessible for undergraduate and graduate students in History and other disciplines.

Modularity rating: 4

How History is Made is easy to follow and would serve as an excellent course textbook for introductory, special topics, and upper-level History courses that emphasize critical thinking, research, and writing as key learning outcomes or assign research papers or "Un-Essay" projects as final projects. This book is also useful for "College 101" or "College/University Life" courses offered to provide study skills and knowledge to freshmen and sophomores. I definitely plan to use this book to scaffold the research and writing process in my special topics and upper-level History courses. Certain sections may even be useful for providing introductory level History students with an understanding of the origins and evolution of the historical profession and/or knowledge about how professional historians utilize a variety of sources to craft arguments, interpret the past, and offer compelling and profound narratives about the relevance of our shared history to contemporary life.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

How History Is Made is organized in a logical, clear fashion.

The pdf version of the book contains minor grammatical errors and a few charts and lists that could distract or confuse the reader.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

See the above comment.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

One issue with How History is Made is the authors' assertion that the historical discipline is different than "history that everyone owns." This seems to detract from their efforts to offer students from all disciplines the skills and knowledge related to "thinking historically." Additionally, there are moments where greater attention to the experiences of historians from Black and marginalized communities is warranted, specifically the sections on becoming a professional historian and the chapter on oral history. If you decide to use this book, it would be a good idea to pair it with studies and interviews featuring scholars from diverse backgrounds to challenge and complicate some of the assertions made about how history is written and performed. One size does not fit all. Practitioners of digital history may not find this book useful due to the brevity of the information provided.

I enjoyed reading this book and plan to use it as a main or supplementary text to help my students learn to think, research, write, and perform historically. I look forward to seeing if it helps them to improve as researchers and scholars.

Table of Contents

- About the Publisher

- About this Project

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- I. Thinking Historically

- II. Reading Historically

- III. Researching Historically

- IV. Writing Historically

- V. Performing Historically

- VI. Skills for Success

- VII. UTA Campus Resources

- VIII. Degree Planning and Beyond, Advice from the UTA History Department

- Bibliography

- Appendix A- Database Rules and Datatypes

- Appendix B - Working With Multiple Tables

- Appendix C- Database Troubleshooting and Coding

- Appendix D- Database Design and Parts of a Database

- Appendix E- Writing Criteria/ Example Rubric

- Image Credits

- Accessibility Rubric

- Errata and Versioning History

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Learn what it means to think like an historian! Units on “Thinking Historically,” “Reading Historically,” “Researching Historically,” and “Writing Historically” describe the essential skills of the discipline of history. “Performing Historically” offers advice on presenting research findings and describes some careers open to those with an academic training in history.

About the Contributors

Stephanie Cole received her PhD in History from the University of Flordia in 1994 and has taught the introduction to historical methods, as well as courses in women’s history, the history of work, history of sexuality and marriage and related topics at UT Arlington since 1996. Her most recent publication is the co-edited volume Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives (University of Georgia Press, 2015).

Kimberly Breuer received her PhD in History from Vanderbilt University in 2004 and has been at UT Arlington since 2004. She regularly teaches the introduction to historical methods, as well as courses in the history of science and technology and Iberian history. Her research centers on the relationship between student (team-based) creation of OER content, experiential learning, and student engagement; student mapped learning pathways and self-regulated learning; interactive and game-based learning.

Scott W. Palmer received his PhD in History from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign in 1997. From his arrival at UT Arlington in 2016 until Fall 2022, he served as Chair of the Department of History. He regularly teaches courses on Russian/Soviet History, Flight Culture and the Human Experience, and History of Video Games, along with upper level offerings in the History of Technology and Science.” “ He is author of Dictatorship of the Air: Aviation Culture and the Fate of Modern Russia (Cambridge University Press, 2006), co-editor of Science, Technology, Environment, and Medicine in Russia’s Great War and Revolution ( Slavica , 2022), and editor of the forthcoming c ollection Flight Culture and the Human Experience (Texas A&M University Press, 2023).

Contribute to this Page

Writing to Learn History: An Instructional Design Study

- Lieke Holdinga University of Amsterdam

- Jannet van Drie University of Amsterdam

- Tanja Janssen University of Amsterdam

- Gert Rijlaarsdam University of Amsterdam

This study reports on the design and evaluation of an instructional unit, aimed at improving secondary school students’ disciplinary writing in history. Central to this design was the replacement of conventional workbook exercises by evaluative source-based writing tasks which were co-developed with participating history teachers. Additionally, an instructional unit to teach students a discipline-specific reading-thinking-writing strategy based on previous research was designed. Two history teachers implemented the evaluative tasks and the strategy instruction in their 11th grade history classrooms in a trial intervention study with a switching panels design. Pre-, mid-, and post-testing consisted of evaluative writing tasks (ca. 200-300 words), which were analyzed on holistic quality, content quality, quality of structure, and text length. Results showed effects in the second panel for content quality.

In this paper we elaborate on the design of this strategy and the instructional design, as well as the design principles underpinning these. Based on the trial study, we present recommendations for redesign in order to optimize practicality and effectiveness of the instructional unit.

How to Cite

- Generic Style Rules for Linguistics

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2023 L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Make a Submission

Scopus CiteScore 2022:

https://www.scopus.com/sourceid/145569

84th percentile

- Published by

- In cooperation with

- Publication system

- ISSN: 1573-1731

- Privacy policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19 Standards of Historical Writing

In this chapter, you will learn the basic expectations for writing an undergrad history research paper. At this point in your college career, you’ve likely had a great deal of instruction about writing and you may be wondering why this chapter is here. There are at least three reasons:

- For some of you, those lessons about writing came before you were ready to appreciate or implement them. If you know your writing skills are weak, you should not only pay close attention to this chapter, but also submit early drafts of your work to the History Tutoring Center (at UTA) or another writing coach. Only practice and multiple drafts will improve those skills.

- Those of you who were paying attention in composition courses know the basics, but may lack a good understanding of the format and approach of scholarly writing in history. Other disciplines permit more generalities and relaxed associations than history, which is oriented toward specific contexts and (often, but not always) linear narratives. Moreover, because historians work in a subject often read by non-academics, they place a greater emphasis on clearing up jargon and avoiding convoluted sentence structure. In other words, the standards of historical writing are high and the guidelines that follow will help you reach them.

- Every writer, no matter how confident or experienced, faces writing blocks. Going back to the fundamental structures and explanations may help you get past the blank screen by supplying prompts to help you get started.

As you read the following guide, keep in mind that it represents only our perspective on the basic standards. In all writing, even history research papers, there is room for stylistic variation and elements of a personal style. But one of the standards of historical writing is that only those who fully understand the rules can break them successfully. If you regularly violate the rule against passive voice verb construction or the need for full subject-predicate sentences, you cannot claim the use of sentence fragments or passive voice verbs is “just your style.” Those who normally observe those grammatical rules, in contrast, might on occasion violate them for effect. The best approach is first to demonstrate to your instructor that you can follow rules of grammar and essay structure before you experiment or stray too far from the advice below.

Introductions

Introductions are nearly impossible to get right the first time. Thus, one of the best strategies for writing an introduction to your history essay is to keep it “bare bones” in the first draft, initially working only toward a version that covers the basic requirements. After you’ve written the full paper (and realized what you’re really trying to say, which usually differs from your initial outline), you can come back to the intro and re-draft it accordingly. However, don’t use the likelihood of re-writing your first draft to avoid writing one. Introductions provide templates not only for your readers, but also for you, the writer. A decent “bare bones” introduction can minimize writer’s block as a well-written thesis statement provides a road map for each section of the paper.

So what are the basic requirements? In an introduction, you must:

- Pose a worthwhile question or problem that engages your reader

- Establish that your sources are appropriate for answering the question, and thus that you are a trustworthy guide without unfair biases

- Convince your reader that they will be able to follow your explanation by laying out a clear thesis statement.

Engaging readers in an introduction

When you initiated your research, you asked questions as a part of the process of narrowing your topic (see the “Choosing and Narrowing a Topic” chapter for more info). If all went according to plan, the information you found as you evaluated your primary sources allowed you to narrow your question further, as well as arrive at a plausible answer, or explanation for the problem you posed. (If it didn’t, you’ll need to repeat the process, and either vary your questions or expand your sources. Consult your instructor, who can help identify what contribution your research into a set of primary sources can achieve.) The key task for your introduction is to frame your narrowed research question—or, in the words of some composition instructors, the previously assumed truth that your inquiries have destabilized—in a way that captures the attention of your readers. Common approaches to engaging readers include:

- Telling a short story (or vignette) from your research that illustrates the tension between what readers might have assumed before reading your paper and what you have found to be plausible instead.

- Stating directly what others believe to be true about your topic—perhaps using a quote from a scholar of the subject—and then pointing immediately to an aspect of your research that puts that earlier explanation into doubt.

- Revealing your most unexpected finding, before moving to explain the source that leads you to make the claim, then turning to the ways in which this finding expands our understanding of your topic.

What you do NOT want to do is begin with a far-reaching transhistorical claim about human nature or an open-ended rhetorical question about the nature of history. Grand and thus unprovable claims about “what history tells us” do not inspire confidence in readers. Moreover, such broadly focused beginnings require too much “drilling down” to get to your specific area of inquiry, words that risk losing readers’ interest. Last, beginning with generic ideas is not common to the discipline. Typical essay structures in history do not start broadly and steadily narrow over the course of the essay, like a giant inverted triangle. If thinking in terms of a geometric shape helps you to conceptualize what a good introduction does, think of your introduction as the top tip of a diamond instead. In analytical essays based on research, many history scholars begin with the specific circumstances that need explaining, then broaden out into the larger implications of their findings, before returning to the specifics in their conclusions—following the shape of a diamond.

Clear Thesis Statements

Under the standards of good scholarly writing in the United States—and thus those that should guide your paper—your introduction contains the main argument you will make in your essay. Elsewhere—most commonly in European texts—scholars sometimes build to their argument and reveal it fully only in the conclusion. Do not follow this custom in your essay. Include a well-written thesis statement somewhere in your introduction; it can be the first sentence of your essay, toward the end of the first paragraph, or even a page or so in, should you begin by setting the stage with a vignette. Wherever you place it, make sure your thesis statement meets the following standards:

A good thesis statement :

- Could be debated by informed scholars : Your claim should not be so obvious as to be logically impossible to argue against. Avoid the history equivalent of “the sky was blue.”

- Can be proven with the evidence at hand : In the allotted number of pages, you will need to introduce and explain at least three ways in which you can support your claim, each built on its own pieces of evidence. Making an argument about the role of weather on the outcome of the Civil War might be intriguing, given that such a claim questions conventional explanations for the Union’s victory. But a great deal of weather occurred in four years and Civil War scholars have established many other arguments you would need to counter, making such an argument impossible to establish in the length of even a long research paper. But narrowing the claim—to a specific battle or from a single viewpoint—could make such an argument tenable. Often in student history papers, the thesis incorporates the main primary source into the argument. For example, “As his journal and published correspondence between 1861 and 1864 reveal, Colonel Mustard believed that a few timely shifts in Tennessee’s weather could have altered the outcome of the war.”

- Is specific without being insignificant : Along with avoiding the obvious, stay away from the arcane. “Between 1861 and 1864, January proved to be the worst month for weather in Central Tennessee.” Though this statement about the past is debatable and possible to support with evidence about horrible weather in January and milder-by-comparison weather in other months, it lacks import because it’s not connected to knowledge that concerns historians. Thesis statements should either explicitly or implicitly speak to current historical knowledge—which they can do by refining, reinforcing, nuancing, or expanding what (an)other scholar(s) wrote about a critical event or person.

- P rovide s a “roadmap” to readers : Rather than just state your main argument, considering outlining the key aspects of it, each of which will form a main section of the body of the paper. When you echo these points in transitions between sections, readers will realize they’ve completed one aspect of your argument and are beginning a new part of it. To demonstrate this practice by continuing the fictional Colonel Mustard example above: “As his journal and published correspondence between 1861 and 1864 reveals, Colonel Mustard believed that Tennessee’s weather was critical to the outcome of the Civil War. He linked both winter storms and spring floods in Tennessee to the outcome of key battles and highlighted the weather’s role in tardy supply transport in the critical year of 1863.” Such a thesis cues the reader that evidence and explanations about 1) winter storms; 2) spring floods; and 3) weather-slowed supply transport that will form the main elements of the essay.

Thesis Statement Practice

More Thesis Statement Practice

The Body of the Paper

What makes a good paragraph.

While an engaging introduction and solid conclusion are important, the key to drafting a good essay is to write good paragraphs. That probably seems obvious, but too many students treat paragraphs as just a collection of a few sentences without considering the logic and rules that make a good paragraph. In essence, in a research paper such as the type required in a history course, for each paragraph you should follow the same rules as the paper itself. That is, a good paragraph has a topic sentence, evidence that builds to make a point, and a conclusion that ties the point to the larger argument of the paper. On one hand, given that it has so much work to do, paragraphs are three sentences , at a minimum . On the other hand, because paragraphs should be focused to making a single point, they are seldom more than six to seven sentences . Though rules about number of sentences are not hard and fast, keeping the guidelines in mind can help you construct tightly focused paragraphs in which your evidence is fully explained.

Topic sentences

The first sentence of every paragraph in a research paper (or very occasionally the second) should state a claim that you will defend in the paragraph . Every sentence in the paragraph should contribute to that topic. If you read back over your paragraph and find that you have included several different ideas, the paragraph lacks focus. Go back, figure out the job that this paragraph needs to do—showing why an individual is important, establishing that many accept an argument that you plan on countering, explaining why a particular primary source can help answer your research question, etc. Then rework your topic sentence until it correctly frames the point you need to make. Next, cut out (and likely move) the sentences that don’t contribute to that outcome. The sentences you removed may well help you construct the next paragraph, as they could be important ideas, just not ones that fit with the topic of the current paragraph. Every sentence needs to be located in a paragraph with a topic sentence that alerts the reader about what’s to come.

Transitions/Bridges/Conclusion sentences in paragraphs

All good writers help their readers by including transition sentences or phrases in their paragraphs, often either at the paragraph’s end or as an initial phrase in the topic sentence. A transition sentence can either connect two sections of the paper or provide a bridge from one paragraph to the next. These sentences clarify how the evidence discussed in the paragraph ties into the thesis of the paper and help readers follow the argument. Such a sentence is characterized by a clause that summarizes the info above, and points toward the agenda of the next paragraph. For example, if the current section of your paper focused on the negative aspects of your subject’s early career, but your thesis maintains he was a late-developing military genius, a transition between part one (on the negative early career) and part two (discussing your first piece of evidence revealing genius) might note that “These initial disastrous strategies were not a good predictor of General Smith’s mature years, however, as his 1841 experience reveals.” Such a sentence underscores for the reader what has just been argued (General Smith had a rough start) and sets up what’s to come (1841 was a critical turning point).

Explaining Evidence

Just as transitional sentences re-state points already made for clarity’s sake, “stitching” phrases or sentences that set-up and/or follow quotations from sources provide a certain amount of repetition. Re-stating significant points of analysis using different terms is one way you explain your evidence. Another way is by never allowing a quote from a source to stand on its own, as though its meaning was self-evident. It isn’t and indeed, what you, the writer, believes to be obvious seldom is. When in doubt, explain more.

For more about when to use a quotation and how to set it up see “How to quote” in the next section on Notes and Quotation.”

Conclusio ns

There exists one basic rule for conclusions: Summarize the paper you have written . Do not introduce new ideas, launch briefly into a second essay based on a different thesis, or claim a larger implication based on research not yet completed. This final paragraph is NOT a chance to comment on “what history tells us” or other lessons for humankind. Your conclusion should rest, more or less, on your thesis, albeit using different language from the introduction and evolved, or enriched, by examples discussed throughout the paper. Keep your conclusion relevant and short, and you’ll be fine.

For a checklist of things you need before you write or a rubric to evaluate your writing click here

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline Copyright © 2022 by Stephanie Cole; Kimberly Breuer; Scott W. Palmer; and Brandon Blakeslee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies and similar tracking technologies described in our privacy policy .

AHA Historical Collections

From its inception, the Association has been committed to the collection, preservation, and dissemination of historical documents. In keeping with that tradition, the AHA staff digitizes and posts essays, reports, and other materials from the Association’s past.

Presidential Addresses

Since the Association was founded in 1884, the Association’s presidents have addressed the annual meeting on a topic of interest or concern to the profession. Since there is no set topic, the subjects treated have ranged widely from the role of history in society to the best practices of historians as writers, teachers, and social scientists. Each in their unique way represents a microcosm of the interests and concerns of the profession in various stages of its development over the past century.

AHA Annual Reports

Each year the American Historical Association produces an annual report that includes reports from the editor of the American Historical Review , officers in the different divisions, and members of the different committees. Also included are the decisions of Council, minutes and resolutions from the business meeting, the association’s financial report, and more.

AHA Archives

The AHA has been issuing reports and statements since its founding in 1884. The materials in this section are offered only for their historical interest, not as statements of current policy or positions on specific historical topics today.

AHA Year in Review