Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Predicting everyday critical thinking: a review of critical thinking assessments.

1. Introduction

2. how critical thinking impacts everyday life, 3. critical thinking: skills and dispositions.

“the use of those cognitive skills and abilities that increase the probability of a desirable outcome. It is used to describe thinking that is purposeful, reasoned, and goal directed—the kind of thinking involved in solving problems, formulating inferences, calculating likelihoods, and making decisions” ( Halpern 2014, p. 8 ).

4. Measuring Critical Thinking

4.1. practical challenges, 4.2. critical thinking assessments, 4.2.1. california critical thinking dispositions inventory (cctdi; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.2. california critical thinking skills test (cctst; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.3. cornell critical thinking test (cctt; the critical thinking company n.d. ), 4.2.4. california measure of mental motivation (cm3; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.5. ennis–weir critical thinking essay test ( ennis and weir 2005 ), 4.2.6. halpern critical thinking assessment (hcta; halpern 2012 ), 4.2.7. test of everyday reasoning (ter; insight assessment, inc. n.d. ), 4.2.8. watson–glaser tm ii critical thinking appraisal (w-gii; ncs pearson, inc. 2009 ).

“Virtual employees, or employees who work from home via a computer, are an increasing trend. In the US, the number of virtual employees has increased by 39% in the last two years and 74% in the last five years. Employing virtual workers reduces costs and makes it possible to use talented workers no matter where they are located globally. Yet, running a workplace with virtual employees might entail miscommunication and less camaraderie and can be more time-consuming than face-to-face interaction”.

5. Conclusions

Institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Ali, Marium, and AJLabs. 2023. How Many Years Does a Typical User Spend on Social Media? Doha: Al Jazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/6/30/how-many-years-does-a-typical-user-spend-on-social-media (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Arendasy, Martin, Lutz Hornke, Markus Sommer, Michaela Wagner-Menghin, Georg Gittler, Joachim Häusler, Bettina Bognar, and M. Wenzl. 2012. Intelligenz-Struktur-Batterie (Intelligence Structure Battery; INSBAT) . Mödling: Schuhfried GmbH. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arum, Richard, and Josipa Roksa. 2010. Academically Adrift . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakshy, Eytan, Solomon Messing, and Lada Adamic. 2015. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348: 1130–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bart, William. 2010. The Measurement and Teaching of Critical Thinking Skills . Tokyo: Invited colloquium given at the Center for Research on Education Testing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruine de Bruin, Wandi, Andrew Parker, and Baruch Fischhoff. 2007. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 938–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Butler, Heather. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment predicts real-world outcomes of critical thinking. Applied Cognitive Psychology 26: 721–29. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, and Diane Halpern. 2020. Critical Thinking Impacts Our Everyday Lives. In Critical Thinking in Psychology , 2nd ed. Edited by Robert Sternberg and Diane Halpern. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, Chris Dwyer, Michael Hogan, Amanda Franco, Silvia Rivas, Carlos Saiz, and Leandro Almeida. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment and real-world outcomes: Cross-national applications. Thinking Skills and Creativity 7: 112–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Butler, Heather, Chris Pentoney, and Mabelle Bong. 2017. Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Thinking Skills and Creativity 24: 38–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ennis, Robert. 2005. The Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test . Urbana: The Illinois Critical Thinking Project. Available online: http://faculty.ed.uiuc.edu/rhennis/supplewmanual1105.htm (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Ennis, Robert, and Eric Weir. 2005. Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test . Seaside: The Critical Thinking Company. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1847582/The_Ennis_Weir_Critical_Thinking_Essay_Test_An_Instrument_for_Teaching_and_Testing (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Facione, Peter. 1990. California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory . Millbrae: The California Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Facione, Peter, Noreen Facione, and Kathryn Winterhalter. 2012. The Test of Everyday Reasoning—(TER): Test Manual . Millbrae: California Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Forsyth, Carol, Philip Pavlik, Arthur C. Graesser, Zhiqiang Cai, Mae-lynn Germany, Keith Millis, Robert P. Dolan, Heather Butler, and Diane Halpern. 2012. Learning gains for core concepts in a serious game on scientific reasoning. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Data Mining . Edited by Kalina Yacef, Osmar Zaïane, Arnon Hershkovitz, Michael Yudelson and John Stamper. Chania: International Educational Data Mining Society, pp. 172–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- French, Brian, Brian Hand, William Therrien, and Juan Valdivia Vazquez. 2012. Detection of sex differential item functioning in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 28: 201–7. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Frenkel, Sheera, and Mike Isaac. 2018. Facebook ‘Better Prepared’ to Fight Election Interference, Mark Zuckerberg Says . Manhattan: New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/technology/facebook-elections-mark-zuckerberg.html (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Gheorghia, Olimpiu. 2018. Romania’s Measles Outbreak Kills Dozens of Children: Some Doctors Complain They Don’t Have Sufficient Stock of Vaccines . New York: Associated Press. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/romania-s-measles-outbreak-kills-dozens-children-n882771 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Giancarlo, Carol, Stephen Bloom, and Tim Urdan. 2004. Assessing secondary students’ disposition toward critical thinking: Development of the California Measure of Mental Motivation. Educational and Psychological Measurement 64: 347–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halpern, Diane. 1998. Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist 53: 449–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halpern, Diane. 2012. Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment . Mödling: Schuhfried (Vienna Test System). Available online: http://www.schuhfried.com/vienna-test-system-vts/all-tests-from-a-z/test/hcta-halpern-critical-thinking-assessment-1/ (accessed on 13 January 2013).

- Halpern, Diane. 2014. Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking , 5th ed. New York: Routledge Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Halpern, Diane, Keith Millis, Arthur Graesser, Heather Butler, Carol Forsyth, and Zhiqiang Cai. 2012. Operation ARIES!: A computerized learning game that teaches critical thinking and scientific reasoning. Thinking Skills and Creativity 7: 93–100. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huber, Christopher, and Nathan Kuncel. 2015. Does college teach critical thinking? A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research 86: 431–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Insight Assessment, Inc. n.d. Critical Thinking Attribute Tests: Manuals and Assessment Information . Hermosa Beach: Insight Assessment. Available online: http://www.insightassessment.com (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Jain, Anjali, Jaclyn Marshall, Ami Buikema, Tim Bancroft, Jonathan Kelly, and Craig Newschaffer. 2015. Autism occurrence by MMR vaccine status among US children with older siblings with and without autism. Journal of the American Medical Association 313: 1534–40. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Klee, Miles, and Nikki McCann Ramirez. 2023. AI Has Made the Israel-Hamas Misinformation Epidemic Much, Much Worse . New York: Rollingstone. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/israel-hamas-misinformation-fueled-ai-images-1234863586/amp/?fbclid=PAAabKD4u1FRqCp-y9z3VRA4PZZdX52DTQEn8ruvHeGsBrNguD_F2EiMrs3A4_aem_AaxFU9ovwsrXAo39I00d-8NmcpRTVBCsUd_erAUwlAjw16x1shqeC6s22OCpSSx2H-w (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Klepper, David. 2022. Poll: Most in US Say Misinformation Spurs Extremism, Hate . New York: Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Available online: https://apnorc.org/poll-most-in-us-say-misinformation-spurs-extremism-hate/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Landis, Richard, and William Michael. 1981. The factorial validity of three measures of critical thinking within the context of Guilford’s Structure-of-Intellect Model for a sample of ninth grade students. Educational and Psychological Measurement 41: 1147–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liedke, Jacob, and Luxuan Wang. 2023. Social Media and News Fact Sheet . Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Lilienfeld, Scott, Rachel Ammirati, and Kristin Landfield. 2009. Giving debiasing away: Can psychological research on correcting cognitive errors promote human welfare? Perspective on Psychological Science 4: 390–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Michael, Joan, Roberta Devaney, and William Michael. 1980. The factorial validity of the Cornell Critical Thinking Test for a junior high school sample. Educational and Psychological Measurement 40: 437–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Health, United States, 2015, with Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities ; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- NCS Pearson, Inc. 2009. Watson-Glaser II Critical Thinking Appraisal: Technical Manual and User’s Guide . London: Pearson. Available online: http://www.talentlens.com/en/downloads/supportmaterials/WGII_Technical_Manual.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Stanovich, Keith, and Richard West. 2008. On the failure of cognitive ability to predict myside and one-sided thinking biases. Thinking & Reasoning 14: 129–67. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- The Critical Thinking Company. n.d. Critical Thinking Company. Available online: www.criticalthinking.com (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Tsipursky, Gleb. 2018. (Dis)trust in Science: Can We Cure the Scourge of Misinformation? New York: Scientific American. Available online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/dis-trust-in-science/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Walsh, Catherina, Lisa Seldomridge, and Karen Badros. 2007. California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory: Further factor analytic examination. Perceptual and Motor Skills 104: 141–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- World Health Organization. 2018. Europe Observes a 4-Fold Increase in Measles Cases in 2017 Compared to Previous Year . Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/sections/press-releases/2018/europe-observes-a-4-fold-increase-in-measles-cases-in-2017-compared-to-previous-year (accessed on 22 October 2023).

| CCTDI | CCTST | CCTT | CM3 | E-W | HCTA | TER | W-GII | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Disposition | Skills | Skills | Disposition | Skills | Skills | Skills | Skills |

| Respondent Age | 18+ | 18+ | 10+ | 5+ | 12+ | 18+ | Late childhood to adulthood | 18+ |

| Format(s) | Digital and paper | Digital | Paper | Digital and paper | paper | Digital | Digital and paper | Digital |

| Length | 75 items | 40 | 52–76 items | 25 items | 1 problem | 20–40 items | 35 items | 40 items |

| Administration Time | 30 min | 55 min | 50 min | 20 min | 40 min | 20–45 min | 45 min | 30 min |

| Response Format | Multiple-choice | Multiple-choice | Multiple-choice | Multiple-choice | Essay | Multiple-choice and short-answer | Dichotomous choice | Multiple-choice |

| Fee | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Evidence—Reliability | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Evidence—validity | no | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | None available | yes |

| Credential required for administration | yes | no | no | no | no | no | Developer scores | no |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Butler, H.A. Predicting Everyday Critical Thinking: A Review of Critical Thinking Assessments. J. Intell. 2024 , 12 , 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020016

Butler HA. Predicting Everyday Critical Thinking: A Review of Critical Thinking Assessments. Journal of Intelligence . 2024; 12(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020016

Butler, Heather A. 2024. "Predicting Everyday Critical Thinking: A Review of Critical Thinking Assessments" Journal of Intelligence 12, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020016

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Enhancing students’ critical thinking skills: is comparing correct and erroneous examples beneficial?

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 26 September 2021

- Volume 49 , pages 747–777, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lara M. van Peppen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1219-8267 1 nAff2 ,

- Peter P. J. L. Verkoeijen 1 , 3 ,

- Anita E. G. Heijltjes 3 ,

- Eva M. Janssen 4 &

- Tamara van Gog 4

13k Accesses

18 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

There is a need for effective methods to teach critical thinking (CT). One instructional method that seems promising is comparing correct and erroneous worked examples (i.e., contrasting examples). The aim of the present study, therefore, was to investigate the effect of contrasting examples on learning and transfer of CT-skills, focusing on avoiding biased reasoning. Students ( N = 170) received instructions on CT and avoiding biases in reasoning tasks, followed by: (1) contrasting examples, (2) correct examples, (3) erroneous examples, or (4) practice problems. Performance was measured on a pretest, immediate posttest, 3-week delayed posttest, and 9-month delayed posttest. Our results revealed that participants’ reasoning task performance improved from pretest to immediate posttest, and even further after a delay (i.e., they learned to avoid biased reasoning). Surprisingly, there were no differences in learning gains or transfer performance between the four conditions. Our findings raise questions about the preconditions of contrasting examples effects. Moreover, how transfer of CT-skills can be fostered remains an important issue for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Unraveling the effects of critical thinking instructions, practice, and self-explanation on students’ reasoning performance

The effects of learning from correct and erroneous examples in individual and collaborative settings, deliberate erring improves far transfer of learning more than errorless elaboration and spotting and correcting others’ errors.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Every day, we reason and make many decisions based on previous experiences and existing knowledge. To do so we often rely on a number of heuristics (i.e., mental shortcuts) that ease reasoning processes (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ). Usually, these decisions are inconsequential but sometimes they can lead to biases (i.e., deviating from ideal normative standards derived from logic and probability theory) with severe consequences. To illustrate, a forensic expert who misjudges fingerprint evidence because it verifies his or her preexisting beliefs concerning the likelihood of the guilt of a defendant, displays the so-called confirmation bias, which can result in a misidentification and a wrongful conviction (e.g., the Madrid bomber case; Kassin et al., 2013 ). Biases occur when people rely on heuristic reasoning (i.e., Type 1 processing) when that is not appropriate, do not recognize the need for analytical or reflective reasoning (i.e., Type 2 processing), are not willing to switch to Type 2 processing or unable to sustain it, or miss the relevant mindware to come up with a better response (e.g., Evans, 2003 ; Stanovich, 2011 ). Our primary tool for reasoning and making better decisions, and thus to avoid biases in reasoning and decision making, is critical thinking (CT), which is generally characterized as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations on which that judgment is based” (Facione, 1990 , p. 2).

Because CT is essential for successful functioning in one’s personal, educational, and professional life, fostering students’ CT has become a central aim of higher education (Davies, 2013 ; Halpern, 2014 ; Van Gelder, 2005 ). However, several large-scale longitudinal studies were quite pessimistic that this laudable aim would be realized merely by following a higher education degree program. These studies revealed that CT-skills of many higher education graduates are insufficiently developed (e.g., Arum & Roksa, 2011 ; Flores et al., 2012 ; Pascarella et al., 2011 ; although a more recent meta-analytic study reached the more positive conclusion that students’ do improve their CT-skills over college years: Huber & Kuncel, 2016 ). Hence, there is a growing body of literature on how to teach CT (e.g., Abrami et al., 2008 , 2014 ; Van Peppen et al., 2018 , 2021 ; Angeli & Valanides, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ; Tiruneh et al., 2014 , 2016 ).

However, there are different views on the best way to teach CT; the most well-known debate being whether CT should be taught in a general or content-specific manner (Abrami et al., 2014 ; Davies, 2013 ; Ennis, 1989 ; Moore, 2004 ). This debate has faded away during the last years, since most researchers nowadays commonly agree that CT can be seen in terms of both general skills (e.g., sound argumentation, evaluating statistical information, and evaluating the credibility of sources) and specific skills or knowledge used in the context of disciplines (e.g., diagnostic reasoning). Indeed, it has been shown that the most effective teaching methods combine generic instruction on CT with the opportunity to integrate the general principles that were taught with domain-specific subject matter. It is well established, for instance, that explicit teaching of CT combined with practice improves learning of CT-skills required for unbiased reasoning (e.g., Abrami et al., 2008 ; Heijltjes et al., 2014b ). However, while some effective teaching methods have been identified, it is as yet unclear under which conditions transfer of CT-skills across tasks or domains can be promoted, that is, the ability to apply acquired knowledge and skills to some new context of related materials (e.g., Barnett & Ceci, 2002 ).

Transfer has been described as existing on a continuum from near to far, with lower degrees of similarity between the initial and transfer situation along the way (Salomon & Perkins, 1989 ). Transferring knowledge or skills to a very similar situation, for instance problems in an exam of the same kind as practiced during the lessons, refers to ‘near’ transfer. By contrast, transferring between situations that share similar structural features but, on appearance, seem remote and alien to one another is considered ‘far’ transfer.

Previous research has shown that CT-skills required for unbiased reasoning consistently failed to transfer to novel problem types, i.e., far transfer, even when using instructional methods that proved effective for fostering transfer in various other domains (Van Peppen et al., 2018 , 2021 ; Heijltjes et al., 2014a , 2014b , 2015 , and this also applies to CT-skills more generally, see for example Halpern, 2014 ; Ritchhart & Perkins, 2005 ; Tiruneh et al., 2014 , 2016 ). This lack of transfer of CT-skills is worrisome because it would be unfeasible to train students on each and every type of reasoning bias they will ever encounter. CT-skills acquired in higher education should transfer to other domains and on-the-job and, therefore, it is crucial to acquire more knowledge on how transfer of these skills can be fostered (and this also applies to CT-skills more generally, see for example, Halpern, 2014 ; Beaulac & Kenyon, 2014 ; Lai, 2011 ; Ritchhart & Perkins, 2005 ). One instructional method that seems promising is comparing correct and erroneous worked examples (i.e., contrasting examples; e.g., Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ).

Benefits of studying examples

Over the last decades, a large body of research has investigated learning from studying worked examples as opposed to unsupported problem solving. Worked examples consist of a problem statement and an entirely and correctly worked-out solution procedure (in this paper referred to as correct examples; Renkl, 2014 ; Renkl et al., 2009 ; Sweller et al., 1998 ; Van Gog et al., 2019 ). Typically, studying correct examples is more beneficial for learning than problem-solving practice, especially in initial skill acquisition (for reviews, see Atkinson et al., 2003 ; Renkl, 2014 ; Sweller et al., 2011 ; Van Gog et al., 2019 ). Although this worked example effect has been mainly studied in domains such as mathematics and physics, it has also been demonstrated in learning argumentation skills (Schworm & Renkl, 2007 ), learning to reason about legal cases (Nievelstein et al., 2013 ) and medical cases (Ibiapina et al., 2014 ), and novices’ learning to avoid biased reasoning (Van Peppen et al., 2021 ).

The worked example effect can be explained by cognitive load imposed on working memory (Paas et al., 2003a ; Sweller, 1988 ). Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) suggests that—given the limited capacity and duration of our working memory—learning materials should be designed so as to decrease unnecessary cognitive load related to the presentation of the materials (i.e., extraneous cognitive load). Instead, learners’ attention should be devoted towards processes that are directly relevant for learning (i.e., germane cognitive load). When solving practice problems, novices often use general and weak problem-solving strategies that impose high extraneous load. During learning from worked examples, however, the high level of instructional guidance provides learners with the opportunity to focus directly on the problem-solving principles and their application. Accordingly, learners can use the freed up cognitive capacity to engage in generative processing (Wittrock, 2010 ). Generative processing involves actively constructing meaning from to-be-learned information, by mentally organizing it into coherent knowledge structures and integrating these principles with one’s prior knowledge (i.e., Grabowski, 1996 ; Osborne & Wittrock, 1983 ; Wittrock, 1974 , 1990 , 1992 , 2010 ). These knowledge structures in turn can aid future problem solving (Kalyuga, 2011 ; Renkl, 2014 ; Van Gog et al., 2019 ).

A recent study showed that the worked example effect also applies to novices’ learning to avoid biased reasoning (Van Peppen et al., 2021 Footnote 1 ): participants’ performance on isomorphic tasks on a final test improved after studying correct examples, but not after solving practice problems. However, studying correct examples was not sufficient to establish transfer to novel tasks that shared similar features with the isomorphic tasks, but on which participants had not acquired any knowledge during instruction/practice. The latter finding might be explained by the fact that students sometimes process worked examples superficially and do not spontaneously use the freed up cognitive capacity to engage in generative processing needed for successful transfer (Renkl & Atkinson, 2010 ). Another possibility is that these examples did not sufficiently encourage learners to make abstractions of the underlying principles and explore possible connections between problems (e.g., Perkins & Salomon, 1992 ). It seems that to fully take advantage of worked examples in learning unbiased reasoning, students should be encouraged to be actively involved in the learning process and facilitated to focus on the underlying principles (e.g., Van Gog et al., 2004 ).

The potential of erroneous examples

While most of the worked-example research focuses on correct examples, recent research suggests that students learn at a deeper level and may come to understand the principles behind solution steps better when (also) provided with erroneous examples (e.g., Adams et al., 2014 ; Barbieri & Booth, 2016 ; Booth et al., 2013 ; Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ; McLaren et al., 2015 ). In studies involving erroneous examples, which are often preceded by correct examples (e.g., Booth et al., 2015 ), students are usually prompted to locate the incorrect solution step and to explain why this step is incorrect or to correct it. This induces generative processing, such as comparison with internally represented correct examples and (self-)explaining (e.g., Chi et al., 1994 ; McLaren et al., 2015 ; Renkl, 1999 ). Students are encouraged to go beyond noticing surface characteristics and to think deeply about how erroneous steps differ from correct ones and why a solution step is incorrect (Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ). This might help them to correctly update schemas of correct concepts and strategies and, moreover, to create schemas for erroneous strategies (Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ; Große & Renkl, 2007 ; Siegler, 2002 ; Van den Broek & Kendeou, 2008 ; VanLehn, 1999 ), reducing the probability of recurring erroneous solutions in the future (Siegler, 2002 ).

However, erroneous examples are typically presented separately from correct examples, requiring learners to use mental resources to recall the gist of the no longer visible correct solutions (e.g., Große & Renkl, 2007 ; Stark et al., 2011 ). Splitting attention across time increases the likelihood that mental resources will be expended on activities extraneous to learning, which subsequently may hamper learning (i.e., temporal contiguity effect: e.g., Ginns, 2006 ). One could, therefore, argue that the use of erroneous examples could be optimized by providing them side by side with correct examples (e.g., Renkl & Eitel, 2019 ). This would allow learners to focus on activities directly relevant for learning, such as structural alignment and detection of meaningful commonalities and differences between the examples (e.g., Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ; Roelle & Berthold, 2015 ). Indeed, studies on comparing correct and erroneous examples revealed positive effects in math learning (Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ; Kawasaki, 2010 ; Loibl & Leuders, 2018 , 2019 ; Siegler, 2002 ).

The present study

We already indicated that it is still an important open question, which instructional strategy can be used to enhance transfer of CT skills. To reiterate, previous research demonstrated that practice consisting of worked example study was more effective for novices’ learning than practice problem solving, but it was not sufficient to establish transfer. Recent research has demonstrated the potential of erroneous examples, which are often preceded by correct examples. Comparing correct and erroneous examples (from here on referred to as contrasting examples) when presenting them side-by-side, seems to hold a considerable promise with respect to promoting generative processing and transfer. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to investigate whether contrasting examples of fictitious students’ solutions on ‘heuristics and biases tasks’ (a specific sub-category of CT skills: e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ) would be more effective to foster learning and transfer than studying correct examples only, studying erroneous examples only, or solving practice problems. Performance was measured on a pretest, immediate posttest, 3-week delayed posttest, and 9-month delayed posttest (for half of the participants due to practical reasons), to examine effects on learning and transfer.

Based on the literature presented above, we hypothesized that studying correct examples would impose less cognitive load (i.e., lower investment of mental effort during learning ) than solving practice problems (i.e., worked example effect: e.g., Van Peppen et al., 2021 ; Renkl, 2014 ; Hypothesis 1). Whether there would be differences in invested mental effort between contrasting examples, studying erroneous examples, and solving practice problems, however, is an open question. That is, it is possible that these instructional formats impose a similar level of cognitive load, but originating from different processes: while practice problem solving may impose extraneous load that does not contribute to learning, generative processing of contrasting or erroneous examples may impose germane load that is effective for learning (Sweller et al., 2011 ). As such, it is important to consider invested mental effort (i.e., experienced cognitive load) in combination with learning outcomes. Secondly, we hypothesized that students in all conditions would benefit from the CT-instructions combined with the practice activities, as evidenced by pretest to immediate posttest gains in performance on instructed and practiced items (i.e., learning : Hypothesis 2). Furthermore, based on cognitive load theory, we hypothesized that studying correct examples would be more beneficial for learning than solving practice problems (i.e., worked example effect: e.g., Van Peppen et al., 2021 ; Renkl, 2014 ). Based on the aforementioned literature, we expected that studying erroneous examples would promote generative processing more than studying correct examples. Whether that generative processing would actually enhance learning, however, is an open question. This can only be expected to be the case if learners can actually remember and apply the previously studied information on the correct solution, which arguably involves higher cognitive load (i.e., temporal contiguity effect) than studying correct examples or contrasting examples. As contrasting can help learners to focus on key information and thereby induces generative processes directly relevant for learning (e.g., Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ), we expected that contrasting examples would be most effective. Thus, we predict the following pattern of results regarding performance gains on learning items (Hypothesis 3): contrasting examples > correct examples > practice problems. As mentioned above, it is unclear how the erroneous examples condition would compare to the other conditions.

Furthermore, we expected that generative processing would promote transfer. Despite findings of previous studies in other domains (e.g., Paas, 1992 ), we found no evidence in a previous study that studying correct examples or solving practice problems would lead to a difference in transfer performance (Van Peppen et al., 2021 ). Therefore, we predict the following pattern of results regarding performance on non-practiced items of the immediate posttest (i.e., transfer , Hypothesis 4): contrasting examples > correct examples ≥ practice problems. Again, it is unclear how the erroneous examples condition would compare to the other conditions.

We expected these effects (Hypotheses 3 and 4) to persist on the delayed posttests. As effects of generative processing (relative to non-generative learning strategies) sometimes increase as time goes by (Dunlosky et al., 2013 ), they may be even greater after a delay. For a schematic overview of the hypotheses, see Table 1 .

We created an Open Science Framework (OSF) page for this project, where all materials, the dataset, and all script files of the experiment are provided (osf.io/8zve4/).

Participants and design

Participants were 182 first-year ‘Public Administration’ and ‘Safety and Security Management’ students of a Dutch university of applied sciences (i.e., higher professional education), both part of the Academy for Security and Governance. These students were approximately 20 years old ( M = 19.53, SD = 1.91) and most of them were male (120 male, 62 female). Before they were involved in these study programs, they completed secondary education (senior general secondary education: n = 122, pre-university: n = 7) or went to college (secondary vocational education: n = 28, higher professional education: n = 24, university education: n = 1).

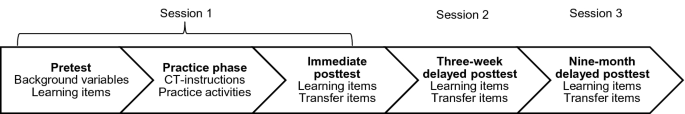

Of the 182 students (i.e., total number of students in these cohorts), 173 students (95%) completed the first experimental session (see Fig. 1 for an overview) and 158 students (87%) completed both the first and second experimental session. Additionally, 83 of these students (46%) of the Safety and Security Management program completed the 9-month delayed posttest during the first mandatory CT-lesson of their second study year (we had no access to another CT-lesson of the Public Administration program). The number of absentees during a lesson (about 15 in total) is quite common for mandatory lessons in these programs and often due to illness or personal circumstances. Students who were absent during the first experimental session and returned to the second experimental session could not participate in the study because they had missed the intervention phase.

Overview of the study design. The four conditions differed in practice activities during the practice phase

We defined a priori that participants would be excluded in case of excessively fast reading speed. Considering that even fast readers can read no more than 350 words per minute (e.g., Trauzettel-Klosinski & Dietz, 2012 ), and the text of our instructions additionally required understanding, we assumed that participants who spent < 0.17 s per word (i.e., 60 s/350 words) did not read the instructions seriously. These participants were excluded from the analyses. Due to drop-outs, we decided to split the analyses to include as many participants as possible. We had a final sample of 170 students ( M age = 19.54, SD = 1.93; 57 female) for the pretest to immediate posttest analyses, a subsample of 155 students for the immediate to 3-week delayed posttest analyses ( M age = 19.46, SD = 1.91; 54 female), and a subsample of 82 students (46%) for the 3-week delayed to 9-month delayed posttest ( M age = 19.27, SD = 1.79; 25 female). We calculated a power function of our analyses using the G*Power software (Faul et al., 2009 ) based on these sample sizes. The power for the crucial Practice Type × Test Moment interaction—under a fixed alpha level of 0.05 and with a correlation between measures of 0.3 (e.g., Van Peppen et al., 2018 )—for detecting a small (η p 2 = .01), medium (η p 2 = .06), and large effect (η p 2 = .14) respectively, is estimated at .42, > .99, and 1.00 for the pretest to immediate posttest analyses; .39, > .99, and 1.00 for the immediate to 3-week delayed posttest analyses; and .21, .90, and > .99 for the 3-week to 9-month delayed posttest. Thus, the power of our study should be sufficient to pick up medium-sized interaction effects.

Students participated in a pretest-intervention–posttest design (see Fig. 1 ). After completing the pretest on learning items (i.e., instructed and practiced during the practice phase), all participants received succinct CT instructions and two correct worked examples. Thereafter, they were randomly assigned to one of four conditions that differed in practice activities during the practice phase: they either (1) compared correct and erroneous examples (‘contrasting examples’, n = 41; n = 35; n = 20); (2) studied correct examples (i.e., step-by-step solutions to unbiased reasoning) and explained why these were right (‘correct examples’, n = 43; n = 40; n = 21); (3) studied erroneous examples (i.e., step-by-step incorrect solutions including biased reasoning) and explained why these were wrong (‘erroneous examples’, n = 43; n = 40; n = 18); or (4) solved practice problems and justified their answers (‘practice problems’, n = 43; n = 40; n = 23). A detailed explanation of the practice activities can be found in the CT-practice subsection below. Immediately after the practice phase and after a 3-week delay, participants completed a posttest on learning items (i.e., instructed and practiced during the practice phase) and transfer items (i.e., not instructed and practiced during the practice phase). Additionally, some students took a posttest after a 9-month delay. Further CT-instructions were given (in three lessons of approx. 90 min) in-between the second session of the experiment and the 9-month follow up. In these lessons, for example, the origins of the concept of CT, inductive and deductive reasoning, and the Toulmin model of argument were discussed. Thus, these data were exploratively analyzed and need to be interpreted with caution.

In the following paragraphs, the used learning materials, instruments and associated measures, and characteristics of the experimental conditions are described.

CT-skills tests

The CT-skills tests consisted of classic heuristics and biases tasks that reflected important aspects of CT. In all tasks, belief bias played a role, that is, when the conclusion aligns with prior beliefs or real-world knowledge but is invalid or vice versa (Evans et al., 1983 ; Markovits & Nantel, 1989 ; Newstead et al., 1992 ). These tasks require that one recognizes the need for analytical and reflective reasoning (i.e. based on knowledge and rules of logical reasoning and statistical reasoning) and switches to this type of reasoning. This is only possible when heuristic responses are successfully inhibited.

The pretest consisted of six classic heuristics and biases items, across two categories (see Online Appendix A for an example of each category): syllogistic reasoning (i.e., logical reasoning) and conjunction (i.e., statistical reasoning) items. Three syllogistic reasoning items measured students’ tendency to be influenced by the believability of a conclusion that is inferred from two premises when evaluating the logical validity of that conclusion (adapted from Evans, 2002 ). For instance, the conclusion that cigarettes are healthy is logically valid given the premises that all things you can smoke are healthy and that you can smoke cigarettes. Most people, however, indicate that the conclusion is invalid because it does not align with their prior beliefs or real-world knowledge (i.e., belief bias, Evans et al., 1983 ). Three conjunction items examined to what extent the conjunction rule ( P (A&B) ≤ P (B))—which states that the probability of multiple specific events both occurring must be lower than the probability of one of these events occurring alone—is neglected (Tversky & Kahneman, 1983 ). To illustrate, people have the tendency to judge two things with a causal or correlational link, for example advanced age and occurrence of heart attacks, as more probable than one of these on its own.

The posttests consisted of parallel versions (i.e., structurally equivalent but different surface features) of the six pretest items which were instructed and practiced and, thus, served to assess differences in learning outcomes. Additionally, the posttests contained six items across two non-practiced categories that served to assess differences in transfer performance (see Online Appendix A for an example of each category). Three Wason selection items measured students’ tendency to disprove a hypothesis by verifying rules rather than falsifying them (i.e., confirmation bias, adapted from Stanovich, 2011 ). Three base-rate items examined students’ tendency to incorrectly judge the likelihood of individual-case evidence (e.g., from personal experience, a single case, or prior beliefs) by not considering all relevant statistical information (i.e., base-rate neglect, adapted from Fong et al., 1986 ; Stanovich & West, 2000 ; Stanovich et al., 2016 ; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ). These transfer items shared similar features with the learning categories, namely, one category requiring knowledge and rules of logic (i.e., Wason selection tasks can be solved by applying syllogism rules) and one category requiring knowledge and rules of statistics (i.e., base-rate tasks can be solved by appropriate probability and data interpretation).

The cover stories of all test items were adapted to the domain of participants’ study program (i.e., Public Administration and Safety and Security Management). A multiple-choice (MC) format with different numbers of alternatives per item was used, with only one correct alternative for each item.

CT-instructions

All participants received a 12 min video-based instruction that started with emphasizing the importance of CT in general, describing the features of CT, and explaining which skills and attitudes are needed to think critically. Thereafter, explicit instructions on how to avoid biases in syllogistic reasoning and conjunction fallacies followed, consisting of two worked examples that showed the correct line of reasoning. The purpose of these explicit instructions was to provide students with knowledge on CT and to allow them to mentally correct initially incorrect responses on the items seen in the pretest.

CT-practice

Participants performed practice activities on the task categories that they were given instructions on (i.e., syllogistic reasoning and conjunction tasks). The CT-practice consisted of four practice tasks, two of each of the task categories. Each practice task was again adapted to the study domain and started with the problem statement (see Online Appendix B for an example of a practice task of each condition). Participants in the correct examples condition were provided with a fictitious student’s correct solution and explanation to the problem, including auxiliary representations, and were prompted to explain why the solution steps were correct. Participants in the erroneous examples condition received a fictitious student’s erroneous solution to the problem, again including auxiliary representations. They were prompted to indicate the erroneous solution step and to provide the correct solution themselves. In the contrasting examples , participants were provided fictitious students’ correct and erroneous solutions to the problem and were prompted to compare the two solutions and to indicate the erroneous solution and the erroneous solution step. Participants in the practice problems condition had to solve the problems themselves, that is, they were instructed to choose the best answer option and were asked to explain how the answer was obtained. Participants in all conditions were asked to read the practice tasks thoroughly. To minimize differences in time investment (i.e., the contrasting examples consisted of considerably more text), we have added self-explanation prompts in the correct examples, erroneous examples, and practice problem conditions.

Mental effort

After each test item and practice-task, participants were asked to report how much effort they invested in completing that task or item on a 9-point subjective rating scale ranging from (1) very, very low effort to (9) very, very high effort (Paas, 1992 ). This widely used scale in educational research (for overviews, see Paas et al., 2003b ; Van Gog & Paas, 2008 ), is assumed to reflect the cognitive capacity actually allocated to accommodate the demands imposed by the task or item (Paas et al., 2003a ).

The study was run during the first two lessons of a mandatory first-year CT-course in two, very similar, Security and Governance study programs. Participants were not given CT-instructions in between these lessons. They completed the study in a computer classroom at the participants’ university with an entire class of students, their teacher, and the experiment leader (first author) present. When entering the classroom, participants were instructed to sit down at one of the desks and read an A4-paper containing some general instructions and a link to the computer-based environment (Qualtrics platform). The first experimental session (ca. 90 min) began with obtaining written consent from all participants. Then, participants filled out a demographic questionnaire and completed the pretest. Next, participants entered the practice phase in which they first viewed the video-based CT-instructions and then were assigned to one of the four practice conditions. Immediately after the practice phase, participants completed the immediate posttest. Approximately 3 weeks later, participants took the delayed posttest (ca. 20 min) in their computer classrooms. Additionally, students of the Safety and Security Management program took the 9-month delayed posttest during the first mandatory CT-lesson of their second study year, Footnote 2 which was exactly the same as the 3-week delayed posttest. During all experimental sessions, participants could work at their own pace and were allowed to use scrap paper. Time-on-task was logged during all phase and participants had to indicate after each test item and practice-task how much effort they invested. Participants had to wait (in silence) until the last participants had finished before they were allowed to leave the classroom.

Data analysis

All test items were MC-only questions, except for one learning item and one transfer items with only two alternatives (conjunction item and base-rate item) that were MC-plus-motivation questions to prevent participants from guessing. Items were scored for accuracy, that is, unbiased reasoning; 1 point for each correct alternative on the MC-only questions or a maximum of 1 point (increasing in steps of 0.5) for the correct explanation for the MC-plus-motivation question using a coding scheme that can be found on our OSF-page. Because two transfer items (i.e., one Wason selection item and one base-rate item) appeared to substantially reduce the reliability of the transfer performance measure, presumably as a result of low variance due to floor effects, we decided to omit these items from our analyses. As a result, participants could attain a maximum total score of 6 on the learning items and a maximum score of 4 on the transfer items. For comparability, learning and transfer outcomes were computed as percentage correct scores instead of total scores. Participants’ explanations on the open questions of the tests were coded by one rater and another rater (the first author) coded 25% of the explanations of the immediate posttest. Intra-class correlation coefficients were 0.990 for the learning test items and 0.957 for the transfer test items. After the discrepancies were resolved by discussion, the primary rater’s codes were used in the analyses.

Cronbach’s alpha on invested mental effort ratings during studying correct examples, studying erroneous examples, contrasting examples, and solving practice problems, respectively, was .87, .76, .77, and .65. Cronbach’s alpha on the learning items was .21, .42, .58, and .31 on the pretest, immediate posttest, 3-week delayed posttest, and 9-month delayed posttest, respectively. The low reliability on the pretest might be explained by the fact that a lack of prior knowledge requires guessing of answers. As such, inter-item correlations are low, resulting in a low Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha on the transfer items was .31, .12, and .29 on the immediate, 3-week delayed, and 9-month delayed posttest, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha on the mental effort items belonging to the learning items was .73, .79, .81, and .76 on the pretest, immediate posttest, 3-week delayed posttest, and 9-month delayed posttest, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha on the mental effort items belonging to the transfer items was .71, .75, and .64 on the immediate posttest, 3-week delayed posttest, and 9-month delayed posttest, respectively. However, caution is required in interpreting the above values because sample sizes as in studies like this do not seem to produce sufficiently precise alpha coefficients (e.g. Charter, 2003 ). Cronbach’s alpha is a statistic and therefore subject to sample fluctuations. Hence, one should be careful with drawing firm conclusions about the precision of Cronbach’s alpha in the population (the parameter) based on small sample sizes (i.e., in reliability literature, samples of 300–400 are considered small, see for instance Charter, 2003 ; Nunally & Bernstein, 1994 ; Segall, 1994 ).

There was no significant difference on pretest performance between participants who stayed in the study and those who dropped out after the first session, t (172) = .38, p = .706, and those who dropped out after the second session, t (172) = − 1.46, p = .146. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in educational background between participants who stayed in the study and those who dropped out after the first session, r (172) = .13, p = .087, and those who dropped out after the second session, r (172) = − .01, p = .860. Finally, there was no significant difference in age between participants who stayed in the study and those who dropped out after the first session, t (172) = − 1.51, p = .134, but there was a difference between participants who stayed in the study and those who dropped out after the second session, t (172) = − 2.02, p = .045. However, age did not correlate significantly with learning performance (minimum p = .553) and was therefore not a confounding variable.

Additionally, participants’ performance during the practice phase was scored for accuracy, that is, unbiased reasoning. In each condition, participants could attain a maximum score of 2 points (increasing in steps of 0.5) for the correct answer on each problem (either MC-only answers or MC-plus-explanation answers), resulting in a maximum total score of 8. The explanations given during practice were coded for explicit relations to the principles that were communicated in the instructions (i.e., principle-based explanations; Renkl, 2014 ). For instance, participants earned the full 2 points if they explained in a conjunction task that the first statement is part of the second statement and that the first statement therefore can never be more likely than the two statements combined. Participants’ explanations were coded by the first author and another rater independently coded 25% of the explanations. Intra-class correlation coefficients were 0.941, 0.946, and 0.977 for performance in the correct examples, erroneous examples, and practice problems conditions respectively (contrasting examples consisted of MC-only questions). After a discussion between the raters about the discrepancies, the primary rater’s codes were updated and used in the exploratory analyses.

For all analyses in this paper, a p -value of .05 was used a threshold for statistical significance. Partial eta-squared (η p 2 ) is reported as an effect size for all ANOVAs (see Table 3 ) with η p 2 = .01, η p 2 = .06, and η p 2 = .14 denoting small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, 1988 ). Cramer’s V is reported as an effect size for chi-square tests with (having 2 degrees of freedom) V = .07, V = .21, and V = .35 denoting small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Preliminary analyses

Check on condition equivalence.

Before running any of the main analyses, we checked our conditions on equivalence. Preliminary analyses confirmed that there were no a-priori differences between the conditions in educational background, χ 2 (15) = 15.57, p = .411, V = .18; gender, χ 2 (3) = 1.21, p = .750, V = .08; performance on the pretest, F (3, 165) = 0.42, p = .739, η p 2 = .01; time spent on the pretest, F (3, 165) = 0.16, p = .926, η 2 < .01; and mental effort invested on the pretest, F (3, 165) = 0.80, p = .498, η 2 = .01. Further, we estimated two multiple regression models (learning and transfer) with practice type and performance on the pretest as explanatory variables, including the interaction between practice type and performance on the pretest. There was no evidence of an interaction effect (learning: R 2 = .07, F (1, 166) = .296, p = .587; transfer: R 2 = .07, F (1, 166) = .260, p = .611) and we can, therefore, conclude that the relationship between practice type and performance on the posttest does not depend on performance on the pretest.

Check on time-on-task

The Levene’s test for equality of variances was significant, F (3, 166) = 9.57, p < .001. Therefore, a Brown–Forsythe one-way ANOVA was conducted. This analysis revealed a significant time-on-task (in seconds) difference between the conditions during practice, F (3, 120.28) = 16.19, p < .001, η 2 = .22. Pairwise comparisons showed that time-on-task was comparable between erroneous examples ( M = 862.79, SD = 422.43) and correct examples ( M = 839.58, SD = 298.33) and between contrasting examples ( M = 512.29, SD = 130.21) and practice problems ( M = 500.41, SD = 130.21). However, time-on-task was significantly higher in the first two conditions compared to the latter two conditions (erroneous examples = correct examples > contrasting examples = practice problems), all p ’s < .001. This should be considered when interpreting the results on effort and posttest performance.

Main analyses

Descriptive and test statistics are presented in Table 2 , 3 , and 4 . Correlations between several variables are presented in Table 5 . It is important to realize that we measured mental effort as an indicator of overall experienced cognitive load. It is known, though, that the relation with learning depends on the origin of the experienced cognitive load. That is, if it originates mainly from germane processes that contribute to learning, high load would positively correlate with test performance, if it originates from extraneous processes, it would negatively correlate with test performance. Caution is warranted in interpreting these correlations, however, because of the exploratory nature of these correlation analyses, which makes it impossible to control for the probability of type 1 errors. We also exploratively analyzed invested mental effort and time-on-task data on the posttest; however, these analyses did not have much added value for this paper and, therefore, are not reported here but will be provided on our OSF-project page.

Performance during the practice phase

As each condition received different prompts during practice, performance during the practice phase could not be meaningfully compared between conditions and, therefore, we decided to report descriptive statistics only to describe the level of performance during the practice phase per condition (see Table 2 ). Descriptive statistics showed that participants earned more than half of the maximum total score while studying correct examples or engaging in contrasting examples. Participants who studied erroneous examples or solved practice problems performed worse during practice.

Mental effort during learning

A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Practice Type on mental effort invested in the practice tasks. Contrary to hypothesis 1, a Tukey post hoc test revealed that participants who solved practice problems invested significantly less effort ( M = 4.28, SD = 1.11) than participants who engaged in contrasting examples ( M = 5.08, SD = 1.29, p = .022) or studied erroneous examples ( M = 5.17, SD = 1.19, p = .008). There were no other significant differences in effort investment between conditions. Interestingly, invested mental effort during contrasting examples correlated negatively with pretest to posttest performance gains on learning items, indicating that the experienced load originated mainly from extraneous processes (see Table 5 ).

Test performance

The data on learning items were analyzed with two 2 × 4 mixed ANOVAs with Test Moment (pretest and immediate posttest/immediate posttest and 3-week delayed posttest) as within-subjects factor and Practice Type (correct examples, erroneous examples, contrasting examples, and practice problems) as between-subjects factor. Because transfer items were not included in the pretest, the data on transfer items were analyzed by a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA with Test Moment (immediate posttest and 3-week delayed posttest) as within-subjects factor and Practice Type (correct examples, erroneous examples, contrasting examples, and practice problems) as between-subjects factor.

Performance on learning items

In line with Hypothesis 2, the pretest-immediate posttest analysis showed a main effect of Test Moment on performance on learning items: participants’ performance improved from pretest ( M = 27.26, SE = 1.43) to immediate posttest ( M = 49.98, SE = 1.87). In contrast to Hypothesis 3, the results did not reveal a main effect of Practice Type, nor an interaction between Practice Type and Test Moment. The second analysis ( N = 154)—to test whether effects are still present after 3 weeks—showed a main effect of Test Moment: participants performed better on the delayed posttest ( M = 55.54, SE = 2.16) compared to the immediate posttest ( M = 50.95, SE = 2.00). Again, contrary to our hypothesis, there was no main effect of Practice Type, nor an interaction between Practice Type and Test Moment.

Performance on transfer items

The results revealed no main effect of Test Moment. Moreover, in contrast to Hypothesis 4, the results did not reveal a main effect of Practice Type, nor an interaction between Practice Type and Test Moment. Footnote 3

Exploratory analyses

Participants from one of the study programs were tested again after a 9-month delay. Regarding performance on learning items, a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA with Test Moment (3-week delayed posttest or 9-month delayed posttest) as within-subjects factor and Practice Type (correct examples, erroneous examples, contrasting examples, and practice problems) as between-subjects factor revealed a main effect of Test Moment (see Table 2 ): participants’ performance improved from 3-week delayed posttest ( M = 53.30, SE = 2.69) to 9-month delayed posttest ( M = 63.00, SE = 2.24). The results did not reveal a main effect of Practice Type, nor an interaction between Practice Type and Test Moment.

Regarding performance on transfer items , a 2 × 4 mixed ANOVA with Test Moment (3-week delayed posttest and 9-month delayed posttest) as within-subjects factor and Practice Type (correct examples, erroneous examples, contrasting examples, and practice problems) as between-subjects factor revealed a main effect of Test Moment (see Table 2 ): participants performed lower on the 3-week delayed test ( M = 19.25, SE = 1.60) than the 9-month delayed test ( M = 24.84, SE = 1.67). The results did not reveal a main effect of Practice Type, nor an interaction between Practice Type and Test Moment.

Previous research has demonstrated that providing students with explicit instructions combined with practice on domain-relevant tasks was beneficial for learning to reason in an unbiased manner (Heijltjes et al., 2014a , 2014b , 2015 ), and that practice consisting of worked example study was more effective for novices’ learning than practice problem solving (Van Peppen et al., 2021 ). However, this was not sufficient to establish transfer to novel tasks. With the present study, we aimed to find out whether contrasting examples—which has been proven effective for promoting transfer in other learning domains—would promote learning and transfer of reasoning skills.

Findings and implications

Our results corroborate the finding of previous studies (e.g., Heijltjes et al., 2015 ; Van Peppen et al., 2018 , 2021 ) that providing students with explicit instructions and practice activities is effective for learning to avoid biased reasoning (Hypothesis 1), since we found considerable pretest to immediate posttest gains on practiced items. Moreover, our results revealed that participants’ performance improved even further after a 3-week and a 9-month delay, although the latter finding could also be attributed to the further instructions that were given in courses in-between the 3-week and 9-month follow up. That students improved in the longer term seems to indicate that our instructional intervention triggered active and deep processing and contributed to storage strength. Hence, our findings provide further evidence that a relatively brief instructional intervention including explicit instructions and practice opportunities is effective for learning of CT-skills, which is promising for educational practice.

In contrast to our expectations, however, we did not find any differences among conditions on either learning or transfer (Hypothesis 3). It is surprising that the present study did not reveal a beneficial effect of studying correct examples as opposed to practicing with problems, as this worked example effect has been demonstrated with many different tasks (Renkl, 2014 ; Van Gog et al., 2019 ), including heuristics-and-biases tasks (Van Peppen et al., 2021 ).

Given that most studies on the worked example effect use pure practice conditions or give minimal instructions prior to practice (e.g., Van Gog et al., 2019 ), whereas the current study was preceded by instructions including two worked examples, one might wonder whether this contributed to the lack of effect. That is, the effects are usually not investigated in a context in which elaborate processing of instructions precedes practice, as in the current (classroom) study, and this may have affected the results. It seems possible that the CT-instructions already had a substantial effect on learning unbiased reasoning, making it difficult to find differential effects of different types of practice activities. This suggestion, however, contradicts the relatively low performance during the practice phase. Moreover, one could argue that if these instructions would lead to higher prior knowledge, it should render the correct worked examples less useful (cf. research on the ‘expertise reversal effect’) and should help those in the other practice conditions perform better on the practice problems, but we did not find that either. Furthermore, these instructions were also provided in a previous study in which a worked example effect was found in two experiments (Van Peppen et al., 2021 ). A major difference between that prior study and this one, however, is that in the present study, participants were prompted to self-explain while studying examples or solving practice problems. Prompting self-explanations, however, seems to encourage students to engage in deep processing during learning (Chi et al., 1994 ), especially for students with sufficient prior knowledge (Renkl & Atkinson, 2010 ). In the present study, this might have interfered with the usual worked-example effect. However, the quality of the self-explanations was higher in the correct example condition than in the problem-solving condition (i.e., performance during the practice phase scores), making the absence of a worked example effect even more remarkable. Given that the worked example effect mainly occurs for novices, one could argue that participants in the current study had more prior knowledge than participants in that prior study; however, it concerned a similar group of students and descriptive statistics showed that students performed comparable on average in both studies.

Another potential explanation might lie in the number of practice tasks, which differed between the prior study (nine tasks: Van Peppen et al., 2021 ) and present study (four tasks), and which might moderate the effect of worked examples. The mean scores on the pretests as well as the performance progress in the practice problem condition was comparable with the previous study, but the progress of the worked example condition was considerably smaller. As it is crucial for a worked example effect that the worked-out solution procedures are understood, it might be that the effect did not emerge in the present study because participants did not get sufficient worked examples during practice.

This might perhaps also explain why contrasting examples did not benefit learning or transfer in the present study. Possibly, students first need to gain a better understanding of the subject matter with heuristics-and-biases tasks before they are able to benefit from aligning the examples (Rittle-Johnson et al., 2009 ). In particular the lack of transfer effects might be related to the duration or extensiveness of the practice activities; even though students learned to solve reasoning tasks, their subject knowledge may have been insufficient to solve novel tasks. As such, it can be argued that establishing transfer needs longer or more extensive practice. Contrasting examples seem to help students extend and refine their knowledge and skills through engaging in comparing activities and analyzing errors, that is, they seem to help them to correctly update schemas of correct concepts and strategies and to create schemas for erroneous strategies reducing the probability of recurring erroneous solutions in the future. However, more attention may need to be paid to the acquisition of the new knowledge and integration with wat students already know (see the Dimensions of Learning framework; Marzano et al., 1993 ). Potentially, having contrasting examples preceded by a more extensive instruction phase to guarantee a better understanding of logical and statistical reasoning would enhance learning and establish transfer. Another possibility would be to provide more guidance in the contrasting examples, as has been done in previous studies by explicitly marking the erroneous examples as incorrect and prompting students to reflect or elaborate on the examples (e.g., Durkin & Rittle-Johnson, 2012 ; Loibl & Leuders, 2018 , 2019 ). It should be noted though, that the lower time on task in the contrasting condition might also be indicative of a motivational problem; whereas the side-by-side presentation was intended to encourage deep processing, it might have had the opposite effect that students might have engaged in superficial processing, just scanning to see where differences in the examples lay, without thinking much about the underlying principles. This idea is confirmed by the finding that invested mental effort during comparing correct and erroneous examples correlated negatively with performance gains on learning items, indicating that the experienced load originated mainly from extraneous processes. It would be interesting in future research to manipulate knowledge gained during instruction to investigate whether prior knowledge indeed moderates the effect of contrasting examples and to examine the interplay between contrasting examples, reflection/elaboration prompts, and final test performance.

Another possible explanation for the lack of a beneficial effect of contrasting examples might be related to the self-explanations prompts that were provided in the correct examples, erroneous examples, and practice problems conditions. Although the prompts differ, it is important to note that the explicit instruction to compare the solution process likely evokes self-explaining processes as well. The reason we added self-explanation prompts to the other conditions was to rule out an effect of prompting as such, as well as a potential effect of time on task (i.e., the text length in the contrasting examples condition was considerably longer than in the other conditions). The positive effect of contrasting examples might have been negated by a positive effect of the self-explanation prompts given in the other conditions. However, had we found a positive effect of comparing, as we expected, our design would have increased the likelihood that this was due to the comparison process and not just to more in-depth processing or higher processing time through self-explaining. Unexpectedly, we did find time-on-task differences between conditions during practice, but this does not seem to affect our findings. Time-on-task during practice was not correlated with learning and transfer posttest performance. This also becomes apparent from the condition means, i.e., the conditions with the lowest time-on-task means did not differ on learning and transfer compared to the conditions with the highest time-on-task means.

The classroom setting might also explain why there were no differential effects of contrasting examples. This study was conducted as part of an existing course and the learning materials were relevant for the course/exam and. Because of that, students’ willingness to invest effort in their performance may have been higher than is generally the case in psychological laboratory studies: their performance on such tasks actually mattered (intrinsically or extrinsically) to them. As such, students in the control conditions may have engaged in generative processing themselves, for instance by trying to compare the given correct (or erroneous) examples with internally represented erroneous (or correct) solutions. Therefore, it is possible that effects of generative processing strategies such as comparing correct and erroneous examples found in the psychological laboratory—where students participate to earn required research credits and the learning materials are not part of their study program—might not readily transfer to field experiments conducted in real classrooms.

The absence of differential effects of the practice activities on learning and transfer may also be related to the affective and attitudinal dimension of CT. Attitudes and perceptions about learning affect learning (Marzano et al., 1993 ), probably even more so in the CT-domain than in other learning domains. Being able to think critically relies heavily on the extent to which one possesses the requisite skills and is able to use these skills, but also on whether one is inclined to use these skills (i.e., thinking dispositions; Perkins et al., 1993 ).

The present study raises further questions about how transfer of CT-skills can be promoted. Although several studies have shown that to enhance transfer of knowledge or skills, instructional strategies should contribute to storage strength by effortful learning conditions that trigger active and deep processing ( desirable difficulties ; e.g., Bjork & Bjork, 2011 ), the present study—once again (Van Peppen et al., 2018 , 2021 ; Heijltjes et al., 2014a , 2014b , 2015 )—showed that this may not apply to transfer of CT-skills. This lack of transfer could lie in inadequate recall of the acquired knowledge, recognition that the acquired knowledge is relevant to the new task, and/or the ability to actually map that knowledge onto the new task (Barnett & Ceci, 2002 ). Following this, a further study should elucidate what the underlying mechanism(s) is/are to shed more light on how to promote transfer of CT-skills.

Limitations and strengths

One limitation of this study is that our measures showed low levels of reliability. Under these circumstances, the probability of detecting a significant effect—given one exists—are low (e.g., Cleary et al., 1970 ; Rogers & Hopkins, 1988 ), and subsequently, the chance that Type 2 errors have occurred in the current study is relatively high. In our study, the low levels of reliability can probably be explained by the multidimensional nature of the CT-test, that is, it represents multiple constructs that do not correlate with each other. Performance on these tasks depends not only on the extent to which that task elicits a bias (resulting from heuristic reasoning), but also on the extent to which a person possesses the requisite mindware (e.g., rules or logic or probability). Thus, systematic variance in performance on such tasks can either be explained by a person’s use of heuristics or his/her available mindware. If it differs per item to what extent a correct answer depends on these two aspects, and if these aspects are not correlated, there may not be a common factor explaining all interrelationships between the measured items. Moreover, the reliability issue may have increased even more since multiple task types were included in the CT-skills tests, requiring different, and perhaps uncorrelated, types of mindware (e.g., rules of logic or probability). Future research, therefore, would need to find ways to improve CT measures (i.e., decrease measurement error), for instance by narrowing down the test into a single measurable construct, or should utilize measures known to have acceptable levels of reliability (LeBel & Paunonen, 2011 ). The latter option seems challenging, however, as multiple studies report rather low levels of reliability of tests consisting of heuristics and biases tasks (Aczel et al., 2015 ; West et al., 2008 ) and revealed concerns with the reliability of widely used standardized CT tests, particularly with regard to subscales (Bernard et al., 2008 ; Bondy et al., 2001 ; Ku, 2009 ; Leppa, 1997 ; Liu et al., 2014 ; Loo & Thorpe, 1999 ). This raises the question whether these issues are related to the general construct CT. To achieve further progress in research on instructional methods for teaching CT, more knowledge on the construct validity of CT in general and unbiased reasoning in particular is needed. When the aim is to evaluate CT as a whole, one should perhaps move towards a more holistic measurement method, for instance by performing pairwise comparisons (i.e., comparative judgment; Bramley & Vitello, 2018 ; Lesterhuis et al., 2017 ). If, however, the intention is to measure specific aspects of CT, one should indicate specifically which aspect of CT to measure and select a suitable test for that aspect. Mainly considering that individual aspects of CT may not be as strongly correlated as thought and then could not be included in one scale.

Another point worth mentioning, is that we opted for assessing invested mental effort, which reflects the amount of cognitive load students experienced. This is informative when combined with their performance (for a more elaborate discussion, see Van Gog & Paas, 2008 ). Moreover, research has shown that it is important to measure cognitive load immediately after each task (e.g., Schmeck et al., 2015 ; Van Gog et al., 2012 ) and the mental effort rating scale (Paas, 1992 ) is easy to apply after each task. However, it unfortunately does not allow us to distinguish between different types of load. It should be noted, though, that it seems very challenging to do this with other measurement instruments (e.g., Skulmowski & Rey, 2017 ). Also, instruments that might be suited for this purpose, for example the rating scale developed by Leppink et al. ( 2013 ), would have been too long to apply after each task in the present study.