- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Health Care in the United States, Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 1013

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

In the United States, there has long been discussion about the quality and nature of the delivery of healthcare. The debates have included who may receive such services, whether or not healthcare is a privilege or an entitlement, whether and how to make patient care affordable to all segments of the population, and the ways in which the government should, or should not, be involved in the provision of such services. Indeed, many people feel that the healthcare in this country is the best in the world; others believe tha (The Free Dictionary)t our health delivery system is broken. This paper shall examine different aspects of the healthcare system in our country, discussing whether it has been successful in providing essential services to American citizens.

The delivery of healthcare services is considered to be a system; according to the Free Diction- ary (Farlex, 2010), a system is defined as “a group of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent elements forming a complex whole.” This is an apt description of our healthcare structure, as it is compiled of patients, medical and mental health providers, hospitals, clinics, laboratories, insurance companies, and many other parties that are reliant on each other and that, when combined, make up the entity known as our healthcare system.

Those who believe that our healthcare system is the best in the world often point to the fact that leaders as well as private citizens from countries throughout the world frequently come to the United States to have surgeries and other treatments that they require for survival. A more cynical view of this phenomenon is that if people have the money, they are able to purchase quality care in the U.S., a “survival of the fittest” situation. Those who lack the resources to travel to the U.S. for medical treatment are simply out of luck, and often will die without the needed care.

In fact, reports by the World Health Organization and other groups consistently indicate that while the United States spends more than any other country on healthcare costs, Americans receive lower quality, less efficient and less fairness from the system. These conclusions come as a result of studying quality of care, access to care, equity and the ability to lead long, productive lives. (World Health Organization,2001.) What cannot be disputed is that the cost of healthcare is constantly rising, a fact which was the precipitant to the large movement to reform healthcare in our country in 2010. More than 10 years ago, the goal of managed care was to drive down the costs of healthcare, but those promises did not materialize (Garsten, 2010.) A large segment of the population is either uninsured or underinsured, and it is speculated that over the next decade, these problems will only increase while other difficulties will arise (Garson, 2010.)

When examining the healthcare system, there are three aspects of care that call for evaluation: the impact of delivering care on the patient, the benefits and harms of that treatment, and the functioning of the healthcare system, as described in an article by Adrian Levy. Levy argues that each of these outcomes should be assessed and should include both the successes and the limitations of each aspect. The idea is that there should be operational measurements of patients’ interactions with the healthcare system that would include patients’ experiences in hospitals, using measurements of their functional abilities and their qualities of life following discharge. The results of patients’ interactions with the healthcare system should be utilized to develop and improve the delivery of healthcare treatment, as well as to develop policy changes that would affect the entire field of healthcare in the United States.

One view of the state of American healthcare is that the system is fragmented; there have been many failed attempts by several presidents to introduce the idea of universal healthcare. Instead, American citizens are saddled with a system in which government pays either directly or indirectly for over 50% of the healthcare in our country, but the actual delivery of insurance and of care is undertaken by an assortment of private insurers, for-profit hospitals, and other parties who raise costs without increasing quality of service (Wells, Krugman, 2006.) If the United States were to switch to a single-payer system such as that provided in Canada, the government would directly provide insurance which would most likely be less expensive and provide better results than our current system.

It is clear that throwing money at a problem does not necessarily resolve it; the fact that the United States spends more than twice as much on healthcare provision as any other country in the world only makes it more ironic that when it comes to evaluating the service, Americans fall appallingly flat. In my opinion, if the new healthcare reform bill had included a public option which would have taken the profit margin out of the equation, the nation and its citizens would have been in a much better position to receive quality healthcare. The fact that people die every day from preventable illnesses and conditions simply because they do not have affordable insurance is a national disgrace. In addition, many of the people who have been the most adamantly against government “intrusion” into their healthcare are actually on Medicaid or Medicare, federally-funded programs. Their lack of understanding of what the debate actually involves is striking, and they are rallying against what is in their own best interests. These are people that equate Federal involvement in healthcare as socialism. Unless and until our healthcare system is able to provide what is needed to all of its citizens, all claims that we have the best healthcare system in the world are, sadly, utterly hollow.

Adrian R Levy (2005, December). Categorizing outcomes of Health Care delivery. Clinical and investigative medicine, pp. 347-351.

Arthur Garson (2000). The U.S. Healthcare System 2010: Problems Principles and Potential Solutions. Retrieved July 3, 2010, from Circulation: The Journal of the American Heart Association: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/101/16/2015

The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). Farlex. Retrieved July 3, 2010. http://www.thefreedictionary.com/system

World Health Organization. (2003, July). WHO World Health Report 2000. Retrieved July 3, 2010, from State of World Health: http://faculty.washington.edu/ely/Report2000.htm

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Using Learning Journals in Continuing and Higher Education, Article Critique Example

Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

What has the pandemic revealed about the US health care system — and what needs to change?

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

With vaccinations for Covid-19 now underway across the nation, MIT SHASS Communications asked seven MIT scholars engaged in health and health care research to share their views on what the pandemic has revealed about the U.S. health care system — and what needs to change. Representing the fields of medicine, anthropology, political science, health economics, science writing, and medical humanities, these researchers articulate a range of opportunities for U.S. health care to become more equitable, more effective and coherent, and more prepared for the next pandemic.

Dwaipayan Banerjee , associate professor of science, technology, and society

On the heels of Ebola, Covid-19 put to rest a persistent, false binary between diseases of the rich and diseases of the poor. For several decades, health care policymakers have labored under the impression of a great epidemiological transition. This theory holds that the developed world has reached a stage in its history that it no longer needs to worry about communicable diseases. These "diseases of the poor" are only supposed to exist in distant places with weak governments and struggling economies. Not here in the United States.

On the surface, Covid-19 made clear that diseases do not respect national boundaries. More subtly, it tested the hypothesis that the global north no longer need concern itself with communicable disease. And in so doing, it undermined our assumptions about global north health-care infrastructures as paradigmatically more evolved. Over the last decades, the United States has been focused on developing increasingly sophisticated drugs. While this effort has ushered in several technological breakthroughs, a preoccupation with magic-bullet cures has distracted from public health fundamentals. The spread of the virus revealed shortages in basic equipment and hospitals beds, the disproportionate effects of disease on the marginalized, the challenge of prevention rather than cure, the limits of insurance-based models to provide equitable care, and our unacknowledged dependence on the labor of underpaid health care workers.

To put it plainly, the pandemic did not create a crisis in U.S. health care. For many in the United States, crisis was already a precondition of care, delivered in emergency rooms and negotiated through denied insurance claims. As we begin to imagine a "new normal," we must ask questions about the old. The pandemic made clear that the "normal" had been a privilege only for a few well-insured citizens. In its wake, can we imagine a health-care system that properly compensates labor and recognizes health care as a right, rather than a privilege only available to the marginalized when an endemic crisis is magnified by a pandemic emergency?

Andrea Campbell , professor of political science

No doubt, the pandemic reveals the dire need to invest in public-health infrastructure to better monitor and address public-health threats in the future, and to expand insurance coverage and health care access. To my mind, however, the pandemic’s greatest significance is in revealing the racism woven into American social and economic policy.

Public policies helped create geographic and occupational segregation to begin with; inadequate racist and classist public policies do a poor job of mitigating their effects. Structural racism manifests at the individual level, with people of color suffering worse housing and exposure to toxins, less access to education and jobs, greater financial instability, poorer physical and mental health, and higher infant mortality and shorter lifespans than their white counterparts. Residential segregation means many white Americans do not see these harms.

Structural racism also materializes at the societal level, a colossal waste of human capital that undercuts the nation’s economic growth, as social and economic policy expert Heather McGhee shows in her illuminating book, "The Sum of Us." These society-wide costs are hidden as well; it is difficult to comprehend the counterfactual of what growth would look like if all Americans could prosper. My hope is that the pandemic renders this structural inequality visible. There is little point in improving medical or public-health systems if we fail to address the structural drivers of poor health. We must seize the opportunity to improve housing, nutrition, and schools; to enforce regulations on workplace safety, redlining, and environmental hazards; and to implement paid sick leave and paid family leave, among other changes. It has been too easy for healthy, financially stable, often white Americans to think the vulnerable are residual. The pandemic has revealed that they are in fact central. It’s time to invest for a more equitable future.

Jonathan Gruber , Ford Professor of Economics

The Covid-19 pandemic is the single most important health event of the past 100 years, and as such has enormous implications for our health care system. Most significantly, it highlights the importance of universal, non-discriminatory health insurance coverage in the United States. The primary source of health insurance for Americans is their job, and with unemployment reaching its highest level since the Great Depression, tens of millions of workers lost, at least temporarily, their insurance coverage.

Moreover, even once the economy recovers, millions of Americans will have a new preexisting condition, Covid-19. That’s why it is critical to build on the initial successes of the Affordable Care Act to continue to move toward a safety net that provides insurance options for all without discrimination.

The pandemic has also illustrated the power of remote health care. The vast majority of patients in the United States have had their first experience with telehealth during the pandemic and found it surprisingly satisfactory. More use of telehealth can lead to increased efficiency of health care delivery as well as allowing our system to reach underserved areas more effectively.

The pandemic also showed us the value of government sponsorship of innovation in the health sciences. The speed with which the vaccines were developed is breathtaking. But it would not have been possible without decades of National Institute of Health investments such as the Human Genome Project, nor without the large incentives put in place by Operation Warp Speed. Even in peacetime, the government has a critical role to play in promoting health care innovation

The single most important change that we need to make to be prepared for the next pandemic is to recognize that proper preparation is, by definition, overpreparation. Unless we are prepared for the next pandemic that doesn’t happen, we won’t possibly be ready for the next pandemic that does.

This means working now, while the memory is fresh, to set up permanent, mandatorily funded institutions to do global disease surveillance, extensive testing of any at-risk populations when new diseases are detected, and a permanent government effort to finance underdeveloped vaccines and therapeutics.

Jeffrey Harris , professor emeritus of economics and a practicing physician The pandemic has revealed the American health care system to be a non-system. In a genuine system, health care providers would coordinate their services. Yet when Elmhurst Hospital in Queens was overrun with patients, some 3,500 beds remained available in other New York hospitals. In a genuine system, everyone would have a stable source of care at a health maintenance organization (HMO). While our country has struggled to distribute the Covid-19 vaccine efficiently and equitably, Israel, which has just such an HMO-based system, has broken world records for vaccination.

Germany, which has all along had a robust public health care system, was accepting sick patients from Italy, Spain, and France. Meanwhile, U.S. hospitals were in financial shock and fee-for-service-based physician practices were devastated. We need to move toward a genuine health care system that can withstand shocks like the Covid-19 pandemic. There are already models out there to imitate. We need to strengthen our worldwide pandemic and global health crisis alert systems. Despite concerns about China’s early attempts to suppress the bad news about Covid-19, the world was lucky that Chinese investigators posted the full genome of SARS-CoV-2 in January 2020 — the singular event that triggered the search for a vaccine. With the recurrent threat of yet another pandemic — after H1N1, SARS, MERS, Ebola, and now SARS-Cov-2 — along with the anticipated health consequences of global climate change, we can’t simply cross our fingers and hope to get lucky again.

Erica Caple James , associate professor of medical anthropology and urban studies The coronavirus pandemic has revealed some of the limits of the American medical and health care system and demonstrated many of the social determinants of health. Neither the risks of infection nor the probability of suffering severe illness are equal across populations. Each depends on socioeconomic factors such as type of employment, mode of transportation, housing status, environmental vulnerability, and capacity to prevent spatial exposure, as well as “preexisting” health conditions like diabetes, obesity, and chronic respiratory illness.

Such conditions are often determined by race, ethnicity, gender, and “biology,” but also poverty, cultural and linguistic facility, health literacy, and legal status. In terms of mapping the prevalence of infection, it can be difficult to trace contacts among persons who are regular users of medical infrastructure. However, it can be extraordinarily difficult to do so among persons who lack or fear such visibility, especially when a lack of trust can color patient-clinician relationships.

One’s treatment within medical and health care systems may also reflect other health disparities — such as when clinicians discount patient symptom reports because of sociocultural, racial, or gender stereotypes, or when technologies are calibrated to the norm of one segment of the population and fail to account for the severity of disease in others.

The pandemic has also revealed the biopolitics and even the “necropolitics” of care — when policymakers who are aware that disease and death fall disproportionately in marginal populations make public-health decisions that deepen the risks of exposure of these more vulnerable groups. The question becomes, “Whose lives are deemed disposable?” Similarly, which populations — and which regions of the world — are prioritized for treatment and protective technologies like vaccines and to what degree are such decisions politicized or even racialized?

Although no single change will address all of these disparities in health status and access to treatment, municipal, state, and federal policies aimed at improving the American health infrastructure — and especially those that expand the availability and distribution of medical resources to underserved populations — could greatly improve health for all.

Seth Mnookin , professor of science writing

The Covid-19 pandemic adds yet another depressing data point to how the legacy and reality of racism and white supremacy in America is lethal to historically marginalized groups. A number of recent studies have shown that Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native Americans have a significantly higher risk of infection, hospitalization, and death compared to white Americans.

The reasons are not hard to identify: Minority populations are less likely to have access to healthy food options, clean air and water, high-quality housing, and consistent health care. As a result, they’re more likely to have conditions that have been linked to worse outcomes in Covid patients, including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.

Marginalized groups are also more likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged — which means they’re more likely to work in service and manufacturing industries that put them in close contact with others, use public transportation, rely on overcrowded schools and day cares, and live in closer proximity to other households. Even now, more vaccines are going to wealthier people who have the time and technology required to navigate the time-consuming vaccine signup process and fewer to communities with the highest infection rates.

This illustrates why addressing inequalities in Americans’ health requires addressing inequalities that infect every part of society. Moving forward, our health care systems should take a much more active role in advocating for racial and socioeconomic justice — not only because it is the right thing to do, but because it is one of the most effective ways to improve health outcomes for the country as a whole.

On a global level, the pandemic has illustrated that preparedness and economic resources are no match for lies and misinformation. The United States, Brazil, and Mexico have, by almost any metric, handled the pandemic worse than virtually every other country in the world. The main commonality is that all three were led by presidents who actively downplayed the virus and fought against lifesaving public health measures. Without a global commitment to supporting accurate, scientifically based information, there is no amount of planning and preparation that can outflank the spread of lies.

Parag Pathak , Class of 1922 Professor of Economics The pandemic has revealed the strengths and weaknesses of America’s health care systems in an extreme way. The development and approval of three vaccines in roughly one year after the start of the pandemic is a phenomenal achievement. At the same time, there are many innovations for which there have been clear fumbles, including the deployment of rapid tests and contact tracing. The other aspect the pandemic has made apparent is the extreme inequality in America’s health systems. Disadvantaged communities have borne the brunt of Covid-19 both in terms of health outcomes and also economically. I’m hopeful that the pandemic will spur renewed focus on protecting the most vulnerable members of society. A pandemic is a textbook situation in economics of externalities, where an individual’s decision has external effects on others. In such situations, there can be major gains to coordination. In the United States, the initial response was poorly coordinated across states. I think the same criticism applies globally. We have not paid enough attention to population health on a global scale. One lesson I take from the relative success of the response of East Asian countries is that centralized and coordinated health systems are more equipped to manage population health, especially during a pandemic. We’re already seeing the need for international cooperation with vaccine supply and monitoring of new variants. It will be imperative that we continue to invest in developing the global infrastructure to facilitate greater cooperation for the next pandemic.

Prepared by MIT SHASS Communications Editor and designer: Emily Hiestand Consulting editor: Kathryn O'Neill

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Program in Science, Technology and Society

- Graduate Program in Science Writing

- MIT Anthropology

- Department of Economics

- Department of Political Science

- Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Related Topics

- Anthropology

- Political science

- Program in STS

- Science writing

- Public health

- Health care

- Diversity and inclusion

- Science, Technology, and Society

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

Related Articles

Reflecting on a year of loss, grit, and pulling together

Building equity into vaccine distribution.

In online vigil, MIT community shares grief, anger, and hope

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Scientists identify mechanism behind drug resistance in malaria parasite

Read full story →

Getting to systemic sustainability

New MIT-LUMA Lab created to address climate challenges in the Mediterranean region

MIT Press releases Direct to Open impact report

Modeling the threat of nuclear war

Modular, scalable hardware architecture for a quantum computer

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

5 Critical Priorities for the U.S. Health Care System

- Marc Harrison

A guide to making health care more accessible, affordable, and effective.

The pandemic has starkly revealed the many shortcomings of the U.S. health care system — as well as the changes that must be implemented to make care more affordable, improve access, and do a better job of keeping people healthy. In this article, the CEO of Intermountain Healthcare describes five priorities to fix the system. They include: focus on prevention, not just treating sickness; tackle racial disparities; expand telehealth and in-home services; build integrated systems; and adopt value-based care.

Since early 2020, the dominating presence of the Covid-19 pandemic has redefined the future of health care in America. It has revealed five crucial priorities that together can make U.S. health care accessible, more affordable, and focused on keeping people healthy rather than simply treating them when they are sick.

- Marc Harrison , MD, is president and CEO of Salt Lake City-based Intermountain Healthcare.

Partner Center

Understanding why health care costs in the U.S. are so high

The high cost of medical care in the U.S. is one of the greatest challenges the country faces and it affects everything from the economy to individual behavior, according to an essay in the May-June 2020 issue of Harvard Magazine written by David Cutler , professor in the Department of Global Health and Population at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Cutler explored three driving forces behind high health care costs—administrative expenses, corporate greed and price gouging, and higher utilization of costly medical technology—and possible solutions to them.

Read the Harvard Magazine article: The World’s Costliest Health Care

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

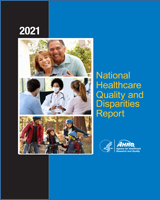

2021 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021 Dec.

2021 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report [Internet].

Overview of u.s. healthcare system landscape.

The National Academy of Medicine defines healthcare quality as “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” Many factors contribute to the quality of care in the United States, including access to timely care, affordability of care, and use of evidence-based guidelines to drive treatment.

This section of the report highlights utilization of healthcare services, healthcare workforce statistics, healthcare expenditures, and major contributors to morbidity and mortality. These factors help paint an overall picture of the U.S. healthcare system, particularly areas that need improvement. Quality measures show whether the healthcare system is adequately addressing risk factors, diseases, and conditions that place the greatest burden on the healthcare system and if change has occurred over time.

- Overview of the U.S. Healthcare System Infrastructure

The NHQDR tracks care delivered by providers in many types of healthcare settings. The goal is to provide high-quality healthcare that is culturally and linguistically sensitive, patient centered, timely, affordable, well coordinated, and safe. The receipt of appropriate high-quality services and counseling about healthy lifestyles can facilitate the maintenance of well-being and functioning. In addition, social determinants of health, such as education, income, and residence location can affect access to care and quality of care.

Improving care requires facility administrators and providers to work together to expand access, enhance quality, and reduce disparities. It also requires coordination between the healthcare sector and other sectors for social welfare, education, and economic development. For example, Healthy People 2030 includes 5 domains (shown in the diagram below) and 78 social determinants of health objectives for federal programs and interventions.

Healthy People 2030 social determinants of health domains.

The numbers of health service encounters and people working in health occupations illustrate the large scale and inherent complexity of the U.S. healthcare system. The tracking of healthcare quality measures in this report iii attempts to quantify progress made in improving quality and reducing disparities in the delivery of healthcare to the American people.

Number of healthcare service encounters, United States, 2018 and 2019.

- In 2018, there were 860 million physician office visits ( Figure 1 ).

- In 2019, patients spent 149 million days in hospice.

- In 2019, there were 100 million home health visits.

- Overview of Disease Burden in the United States

The National Institutes of Health defines disease burden as the impact of a health problem, as measured by prevalence, incidence, mortality, morbidity, extent of disability, financial cost, or other indicators.

This section of the report highlights two areas of disease burden that have major impact on the health system of the United States: years of potential life lost and leading causes of death. The NHQDR tracks measures of quality for most of these conditions. Variation in access to care and care delivery across communities contributes to disparities related to race, ethnicity, sex, and socioeconomic status.

The concept of years of potential life lost (YPLL) involves estimating the average time a person would have lived had he or she not died prematurely. This measure is used to help quantify social and economic loss from premature death, and it has been promoted to emphasize specific causes of death affecting younger age groups. YPLL inherently incorporates age at death, and its calculation mathematically weights the total deaths by applying values to death at each age. 1

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), unintentional injuries include opioid overdoses (unintentional poisoning), motor vehicle crashes, suffocation, drowning, falls, fire/burns, and sports and recreational injuries. Overdose deaths involving opioids, including prescription opioids , heroin , and synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl ), have been a major contributor to the increase in unintentional injuries. Opioid overdose has increased to more than six times its 1999 rate. 2

Age-adjusted years of potential life lost before age 65, by cause of death, 2010–2019. Key: YPLL = years of potential life lost. Note: The perinatal period occurs from 22 completed weeks (154 days) of gestation and ends 7 completed days after (more...)

- From 2010 to 2019, there were no changes in the ranking of the top 10 leading diseases and injuries contributing to YPLL. The top 5 were unintentional injury, cancer, heart disease, suicide, and complications during the perinatal period ( Figure 2 ). The remaining 5 were homicide, congenital anomalies, liver disease, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease.

- Unintentional injury increased from 791.8 per 100,000 population in 2010 to 1,024.3 per 100,000 population in 2019.

- Cancer decreased from 635.2 per 100,000 population in 2010 to 533.3 per 100,000 population in 2019.

- Heart disease decreased from 474.3 per 100,000 population in 2010 to 453.2 per 100,000 population in 2019.

Age-adjusted years of potential life lost before age 65, by cause of death and race, 2019. Key: AI/AN = American Indian or Alaska Native; PI = Pacific Islander.

- In 2019, among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, the top five contributing factors for YPLL were unintentional injuries (1,284.6 per 100,000 population), suicide (457.7 per 100,000 population), liver disease (451.6 per 100,000 population), heart disease (399.8 per 100,000 population), and cancer (339.6 per 100,000 population) ( Figure 3 ).

- In 2019, among Asian and Pacific Islander people, the top five contributing factors for YPLL were cancer (375.7 per 100,000 population), unintentional injuries (299.4 per 100,000 population), complications in the perinatal period (203.4 per 100,000 population), suicide (198.5 per 100,000), and heart disease (197.7 per 100,000 population).

- In 2019 among Black people, the top five contributing factors for YPLL were unintentional injuries (1,085.8 per 100,000 population), heart disease (843.5 per 100,000 population), homicide (801.7 per 100,000 population), cancer (652.7 per 100,000 population), and complications in the perinatal period (560.4 per 100,000 population).

- In 2019, among White people, the top five contributing factors for YPLL were unintentional injuries (1,080.0 per 100,000 population), cancer (530.1 per 100,000 population), heart disease (406.6 per 100,000 population), suicide (387.6 per 100,000 population), and complications in the perinatal period (215.7 per 100,000 population).

Leading causes of death for the total population, United States, 2018 and 2019.

- In 2019, heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and diabetes were among the leading causes of death for the overall U.S. population ( Figure 4 ).

- Overall, kidney disease moved from the 9 th leading cause of death in 2018 to the 8 th leading cause of death in 2019.

- Suicide remained the 10 th leading cause of death in 2018 and 2019.

The years of potential life lost, years with disability, and leading causes of death represent some aspects of the burden of disease experienced by the American people. Findings highlighted in this report attempt to quantify progress made in improving quality of care, reducing disparities in healthcare, and ultimately reducing disease burden.

- Overview of U.S. Community Hospital Intensive Care Beds

The United States has almost 1 million staffed hospital beds; nearly 800,000 are community hospital beds and 107,000 are intensive care beds. Figure 5 shows the numbers of different types of staffed intensive care hospital beds.

Medical-surgical intensive care provides patient care of a more intensive nature than the usual medical and surgical care delivered in hospitals, on the basis of physicians’ orders and approved nursing care plans. These units are staffed with specially trained nursing personnel and contain specialized equipment for monitoring and supporting patients who, because of shock, trauma, or other life-threatening conditions, require intensified comprehensive observation and care. These units include mixed intensive care units.

Pediatric intensive care provides care to pediatric patients that is more intensive in nature than that usually provided to pediatric patients. The unit is staffed with specially trained personnel and contains monitoring and specialized support equipment for treating pediatric patients who, because of shock, trauma, or other life-threatening conditions, require intensified, comprehensive observation and care.

Cardiac intensive care provides patient care of a more specialized nature than the usual medical and surgical care, on the basis of physicians’ orders and approved nursing care plans. The unit is staffed with specially trained nursing personnel and contains specialized equipment for monitoring, support, or treatment for patients who, because of severe cardiac disease such as myocardial infarction, open-heart surgery, or other life-threatening conditions, require intensified, comprehensive observation and care.

Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are distinct from the newborn nursery and provide intensive care to sick infants, including those with the very lowest birth weights (less than 1,500 grams). NICUs may provide mechanical ventilation, care before or after neonatal surgery, and special care for the sickest infants born in the hospital or transferred from another institution. Neonatologists typically serve as directors of NICUs.

Burn care provides care to severely burned patients. Severely burned patients are those with the following: (1) second-degree burns of more than 25% total body surface area for adults or 20% total body surface area for children; (2) third-degree burns of more than 10% total body surface area; (3) any severe burns of the hands, face, eyes, ears, or feet; or (4) all inhalation injuries, electrical burns, complicated burn injuries involving fractures and other major traumas, and all other poor risk factors.

Other intensive care unit beds are in specially staffed, specialty-equipped, separate sections of a hospital dedicated to the observation, care, and treatment of patients with life-threatening illnesses, injuries, or complications from which recovery is possible. This type of care includes special expertise and facilities for the support of vital functions and uses the skill of medical, nursing, and other staff experienced in the management of conditions that require this higher level of care.

U.S. community hospital intensive care staffed beds, by type of intensive care, 2019. Note: Community hospitals are defined as all nonfederal, short-term general, and other special hospitals. Other special hospitals include obstetrics and gynecology; (more...)

- In 2019, of the more than 900,000 staffed hospital beds in the United States, 86% were in community hospitals (data not shown).

- Most of the more than 107,000 intensive care beds in community hospitals were medical-surgical intensive care (51.9%) and neonatal intensive care beds (21.1%) ( Figure 5 ).

Critical access hospital (CAH) is a designation given to eligible rural hospitals by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The CAH designation is designed to reduce the financial vulnerability of rural hospitals and improve access to healthcare by keeping essential services in rural communities. To accomplish this goal, CAHs receive certain benefits, such as cost-based reimbursement for Medicare services. As of July 16, 2021, 1,353 CAHs were located throughout the United States. 3 , iv

Distribution of critical access hospitals in the United States, 2021.

- According to CMS, CAHs must be located in a rural area or an area that is treated as rural, v so the number of CAHs varies by state ( Figure 6 ).

- In 2019, California had a population of 39.5 million and 36 CAHs compared with Iowa, which had a population of only 3.2 million but 82 CAHs.

- U.S. Healthcare Workforce

Healthcare access and quality can be affected by workforce shortages, particularly in rural areas. In addition, lack of racial, ethnic, and gender concordance between providers and patients can lead to miscommunication, stereotyping, and stigma, and, ultimately, suboptimal healthcare.

Healthcare Workforce Availability

Improving quality of care, increasing access to care, and controlling healthcare costs depend on the adequate availability of healthcare providers. 4 Physician shortages currently exist in many states across the nation, with relatively fewer primary care and specialty physicians available in nonmetropolitan counties compared with metropolitan counties. 5

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) further projects that the supply of key professions, including primary care providers, general dentists, adult psychiatrists, and addiction counselors, will fall short of demand by 2030. 6 These concerns have the potential to influence the delivery of healthcare and negatively affect patient outcomes.

Number of people working in health occupations, United States, 2019. Key: EMT = emergency medical technician. Note: Doctors of medicine also include doctors of osteopathic medicine. Active physicians include those working in direct patient care, administration, (more...)

- In 2019, there were 3.7 million registered nurses ( Figure 7 ).

- In 2019, there were 2.4 million healthcare aides, which includes nursing, psychiatric, home health, and occupational therapy aides and physical therapy assistants and aides.

- In 2019, there were 2.1 million health technologists.

- In 2019, 2.0 million other health practitioners provided care, including more than 145,000 physician assistants (PAs).

- In 2019, there were 972,000 active medical doctors in the United States, which include doctors of medicine and doctors of osteopathy.

- In 2019, there were 183,000 dentists.

In recent decades, promising approaches that address the supply-demand imbalance have emerged as alternatives to simply increasing the number of physicians. One strategy relies on telehealth technologies to improve physicians’ efficiency or to increase access to their services. For example, Project ECHO is a telehealth model in which specialists remotely support multiple rural primary care providers so that they can treat patients for conditions that might otherwise require traveling to distant specialty centers. 7

Another strategy relies on peer-led models, in which community-based laypeople receive the training and support needed to deliver care for a (typically) narrow range of conditions. Successful examples of this approach exist, including the deployment of community health workers to manage chronic diseases, 8 promotoras to provide maternal health services, 9 peer counselors for mental health and substance use disorders, 10 and dental health aides to deliver oral health services in remote locations. 11

The National Institutes of Health, HRSA, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have sponsored formative research to examine key issues that must be addressed to further develop these models, but all show promise for expanding access to care and increasing overall diversity within the healthcare workforce.

Workforce Diversity

The number of full-time, year-round workers in healthcare occupations has almost doubled since 2000, increasing from 5 million to 9 million workers, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey .

A racially and ethnically diverse health workforce has been shown to promote better access and healthcare for underserved populations and to better meet the health needs of an increasingly diverse population. People of color, however, remain underrepresented in several health professions, despite longstanding efforts to increase the diversity of the healthcare field. 12

Additional research has found that physicians from groups underrepresented in the health professions are more likely to serve minority and economically disadvantaged patients. It has also been found that Black and Hispanic physicians practice in areas with larger Black and Hispanic populations than other physicians do. 13

Gender diversity is also important. Women currently account for three-quarters of full-time, year-round healthcare workers. Although the number of men who are dentists or veterinarians has decreased over the past two decades, men still make up more than half of dentists, optometrists, and emergency medical technicians/paramedics, as well as physicians and surgeons earning over $100,000. 14

Women working as registered nurses, the most common healthcare occupation, earn on average $66,000. Women working as nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, the second most common healthcare occupation, earn only $27,000. 14

The impact of unequal gender distribution in the healthcare workforce is observed in the persistence of gender inequality in heart attack mortality. Most physicians are male, and some may not recognize differences in symptoms in female patients. The fact that gender concordance correlates with whether a patient survives a heart attack has implications for theory and practice. Medical practitioners should be aware of the possible challenges male providers face when treating female heart attack patients. 15

Research has shown that some mental health workforce groups, such as psychiatrists, are more diverse than many other medical specialties, and this diversity has improved over time. However, this diversity has not translated as well to academic faculty or leadership positions for underrepresented minorities. It was found that there was more minority representation among psychiatry residents (16.2%) compared with faculty (8.7%) and practicing physicians (10.4%). This difference results in minority students and trainees having fewer minority mentors to guide them in the profession.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Physicians

Diversification of the physician workforce has been a goal for several years and could improve access to primary care for underserved populations and address health disparities. Family physicians’ race/ethnicity has become more diverse over time but still does not reflect the national racial and ethnic composition. 16 , vi

Racial and ethnic distribution of all active physicians (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due (more...)

- In 2019, White people were 60% of the U.S. population and approximately 64% of physicians ( Figure 8 ).

- Asian people were about 6% of the U.S. population and approximately 22% of physicians.

- Black people were 12% of the U.S. population but only 5% of physicians.

- Hispanic people were 18% of the U.S. population but only 7% of physicians.

- People of more than race made up about 3% of the U.S. population but less than 2% of physicians.

- AI/AN people and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) people accounted for 1% or less of the U.S. population and 1% or less of physicians (data not shown).

Preventive care, including screenings, is key to reducing death and disability and improving health. Evidence has shown that patients with providers of the same gender have higher rates of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. 17

Physicians by race/ethnicity and sex, 2018. Key: AI/AN = American Indian or Alaska Native; NHPI = Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Note: Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working (more...)

- In 2018, among Black physicians, females (53.0%) constituted a larger percentage than males (47.0%) ( Figure 9 ).

- Among White physicians, 65.5% were male.

- Among Asian physicians, 55.7% were male.

- Among AI/AN physicians, 60.1% were male.

- Among Hispanic physicians, 59.5% were male.

White physicians by age and sex, 2018. Note : Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working at least 20 hours per week. Physicians who are retired, semiretired, temporarily not in practice, (more...)

- In 2018, among White physicians, males were the vast majority of those age 65 years and over (79.3%) and of those ages 55–64 years (71.5%) ( Figure 10 ).

- A little more than half of White physicians age 34 and younger were females (50.6%).

- Among White physicians age 35 and over, males made up a larger percentage of the workforce than females. This percentage increased with age.

Black physicians by age and sex, 2018. Note: Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working at least 20 hours per week. Physicians who are retired, semiretired, temporarily not in practice, (more...)

- In 2018, among Black physicians under age 55, females made up a larger percentage of the workforce than males. This percentage decreased with increasing age ( Figure 11 ).

- Females were 44.2% of Black physicians ages 55–64 and 34.9% of Black physicians age 65 and over.

Asian physicians by age and sex, 2018. Note: Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working at least 20 hours per week. Physicians who are retired, semiretired, temporarily not in practice, (more...)

- In 2018, among Asian physicians, males were the vast majority of those age 65 years and over (72.7%) and of those ages 55–64 years (66.3%) ( Figure 12 ).

- Among Asian physicians age 34 and younger, there were more females (52.0%) than males (48.0%).

- Among Asian physicians age 35 and over, males made up a larger percentage of the workforce than females. This percentage increased with age.

American Indian or Alaska Native physicians by age and sex, 2018. Note: Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working at least 20 hours per week. Physicians who are retired, semiretired, (more...)

- In 2018, among AI/AN physicians, males were the vast majority of those age 65 years and over (73.2%) and of those ages 55–64 years (62.6%) ( Figure 13 ).

- Among AI/AN physicians age 34 and younger, there were more females (57.9%) than males (42.1%).

- Among AI/AN physicians age 45 and over, males made up a larger percentage of the workforce than females. This percentage increased with age.

Hispanic physicians by age and sex, 2018. Note: Physicians (federal and nonfederal) who are licensed by a state are considered active, provided they are working at least 20 hours per week. Physicians who are retired, semiretired, temporarily not in practice, (more...)

- In 2018, most Hispanic physicians age 65 years and over (77.5%) and ages 55–64 years (67.5%) were males ( Figure 14 ).

- Among Hispanic physicians age 34 and younger, there were more females (55.3%) compared with males (44.7%).

- Among Hispanic physicians age 35 and over, males made up a larger percentage of the workforce than females. This percentage increased with age.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Dentists

The racial and ethnic diversity of the oral healthcare workforce is insufficient to meet the needs of a diverse population and to address persistent health disparities. 18 However, among first-time, first-year enrollees in dental school, improved diversity has been observed. The number of African American enrollees nearly doubled and the number of Hispanic enrollees has increased threefold between 2000 and 2020. 19 Increased diversity among dentists may improve access and quality of care, particularly in the area of culturally and linguistically sensitive care.

Dentists by race (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and Other are non-Hispanic. If estimates for certain racial and ethnic groups meet data suppression criteria, they are recategorized into (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of dentists (70%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 15 ).

- Asian people, 18%,

- Hispanic people, 6%

- Black people, 5%, and

- Other (multiracial and AI/AN people), 1.0%.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Registered Nurses

Ensuring workforce diversity and leadership development opportunities for racial and ethnic minority nurses must remain a high priority in order to eliminate health disparities and, ultimately, achieve health equity. 20

Registered nurses by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding and (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of RNs (69%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 16 ).

- Black people, 11%,

- Asian people, 9%,

- Hispanic people, 8%,

- Multiracial people, 2%, and

- Other (AI/AN and NHPI people), 1%.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Pharmacists

Most healthcare diagnostic and treating occupations such as pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and dentists are primarily White while healthcare support roles such as dental assistants, medical assistants, and personal care aides are more diverse. To decrease disparities and enhance patient care, racial and ethnic diversity must be improved on all levels of the healthcare workforce, not just in support roles. 21

Progress has been made toward increased racial and ethnic diversity, but more work is needed. As Bush notes in an article on underrepresented minorities in pharmacy school, “If we are determined to reduce existing healthcare disparities among racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, then we must be determined to diversify the healthcare workforce.” 22

Pharmacists by race (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding and the exclusion of groups (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of pharmacists (65%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 17 ).

- Asian people, 20%,

- Black people, 7%,

- Hispanic people, 5%, and

- Multiracial people, 2%.

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Therapists

Occupational therapists, physical therapists, radiation therapists, recreational therapists, and respiratory therapists are classified as health diagnosing and treating practitioners. Hispanic people are significantly underrepresented in all of the occupations in the category of Health Diagnosing and Treating Practitioners. Among non-Hispanic people, Black people are underrepresented in most of these occupations.

Asian people are underrepresented among speech-language pathologists, and AI/AN people are underrepresented in nearly all occupations. To the extent they can be reliably reported, data also show that NHPI people are underrepresented in all occupations in the Health Diagnosing and Treating Practitioners group. 21

Therapists include occupational therapists, physical therapists, radiation therapists, recreational therapists, respiratory therapists, speech-language pathologists, exercise physiologists, and other therapists.

Therapists by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding and the exclusion (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of therapists (74%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 18 ).

- Black people, 8%,

- Asian people, 8%,

- Hispanic people, 8%, and

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Advanced Practice Registered Nurses

The adequacy and distribution of the primary care workforce to meet the current and future needs of Americans continue to be cause for concern. Advanced practice registered nurses are increasingly being used to fill this gap but may include clinicians in areas beyond primary care, such as clinical nurse specialists, nurse-midwives, and nurse anesthetists.

Advanced practice registered nurses are registered nurses educated at the master’s or post-master’s level who serve in a specific role with a specific patient population. They include certified nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse-midwives.

While physicians continue to account for most of the primary care workforce (74%) in the United States, nurse practitioners represent nearly one-fifth (19%) of the primary care workforce, followed by physician assistants, accounting for 7%. 23

Nurse practitioners provide an extensive range of services that includes taking health histories and providing complete physical exams. They diagnose and treat acute and chronic illnesses, provide immunizations, prescribe and manage medications and other therapies, order and interpret lab tests and x rays, and provide health education and supportive counseling.

Nurse practitioners deliver primary care in practices of various sizes, types (e.g., private, public), and settings, such as clinics, schools, and workplaces. Nurse practitioners work independently and collaboratively. They often take the lead in providing care in innovative primary care arrangements, such as retail clinics. 24

Advanced practice registered nurses by race (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of advanced practice registered nurses (78 %) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 19 ).

- Asian people, 6%,

- Hispanic people, 6%, and

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Emergency Professionals

Workforce diversity can reduce communication barriers and inequalities in healthcare delivery, especially in settings such as emergency departments, where time pressure and incomplete information may worsen the effects of implicit biases. The racial and ethnic makeup of the paramedic and emergency medical technician workforce indicates that concerted efforts are needed to encourage students of diverse backgrounds to pursue emergency service careers. 25

Emergency medical technicians and paramedics by race (left), and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding. In addition, (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics (72%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 20 ).

- Hispanic people, 13%

- Asian people, 3%,

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Other Health Practitioners

Other health practitioners include physician assistants, medical assistants, dental assistants, chiropractors, dietitians and nutritionists, optometrists, podiatrists, and audiologists, as well as massage therapists, medical equipment preparers, medical transcriptionists, pharmacy aides, veterinary assistants and laboratory animal caretakers, phlebotomists, and healthcare support workers.

Other health practitioners by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding (more...)

- In 2019, the distribution of other health practitioners closely aligned with the racial and ethnic distribution of the U.S. population ( Figure 21 ).

- In 2019, 58% of other health practitioners were non-Hispanic White.

- In 2019, Hispanic people accounted for 20% of other health practitioners.

- Black people, 12%,

- Asian people, 7%,

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Physician Assistants

Physician assistants (PAs) are included in the Other Health Practitioners workforce group but are highlighted because they play a critical role in frontline primary care services in many settings, especially medically underserved and rural areas. With the demand for primary care services projected to grow and PAs’ roles in direct care, understanding this occupation’s racial and ethnic diversity is important.

Studies identify the value of advanced practice providers in patient care management, continuity of care, improved quality and safety metrics, and patient and staff satisfaction. These providers can also enhance the educational experience of residents and fellows. 26 However, a lack of workforce diversity has detrimental effects on patient outcomes, access to care, and patient trust, as well as on workplace experiences and employee retention. 27

Physician assistants by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of physician assistants (73%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 22 ).

- Black people, 6%,

- Multiracial people, 3%, and

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Other Health Occupations

Other health occupations include veterinarians, acupuncturists, all other healthcare diagnosing or treating practitioners, dental hygienists, and licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses.

Other health occupations by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of staff in other health occupations (61%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 23 ).

- Black people, 19%,

- Hispanic people, 11%

- Asian people, 6 %,

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Health Technologists

Health technologists include clinical laboratory technologists and technicians, cardiovascular technologists and technicians, diagnostic medical sonographers, radiologic technologists and technicians, magnetic resonance imaging technologists, nuclear medicine technologists and medical dosimetrists, pharmacy technicians, surgical technologists, veterinary technologists and technicians, dietetic technicians and ophthalmic medical technicians, medical records specialists, and opticians (dispensing), miscellaneous health technologists and technicians, and technical occupations.

Health technologists by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding and the (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of health technologists (63%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 24 ).

- Black people, 14%,

- Hispanic people, 13%,

- Asian people, 8%, and

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Healthcare Aides

Healthcare aides include nursing, psychiatric, home health, occupational therapy, and physical therapy assistants and aides.

Healthcare aides by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, >1 Race, and Other are non-Hispanic. Percentages of the U.S. population do not add to 100 due to rounding and (more...)

- In 2019, 41% of healthcare aides were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 25 ).

- Black people, 32%,

- Hispanic people, 18%,

Racial and Ethnic Diversity Among Psychologists

The United States has an inadequate workforce to meet the mental health needs of the population, 28 , 29 , 30 and it is estimated that in 2020, nearly 54% of the U.S. population age 18 and over with any mental illness did not receive needed treatment. 31 This unmet need is even greater for racial and ethnic minority populations. Nearly 80% of Asian and Pacific Islander people, vii 63% of African Americans, and 65% of Hispanic people with a mental illness do not receive mental health treatment. 29 , 32 , 33 , 34

These gaps in mental health care may be attributed to a number of reasons, including stigma, cultural attitudes and beliefs, lack of insurance, or lack of familiarity with the mental health system. 35 , 36 , 37 However, a significant contributor to this treatment gap is the composition of the workforce.

The current mental health workforce lacks racial and ethnic diversity. 34 , 38 Research has shown that racial and ethnic patient-provider concordance is correlated with patient engagement and retention in mental health treatment. 39 In addition, racial and ethnic minority providers are more likely to serve patients of color than White providers. 34 , 36

Among psychologists, a key practitioner group in the mental health workforce, 37 , 40 minorities are significantly underrepresented. Psychologists in the United States are predominantly non-Hispanic White, while all racial and ethnic minorities represented only about one-sixth of all psychologists from 2011 to 2015.

Reducing the serious gaps in mental health care for racial and ethnic minority populations will require a significant shift in the workforce. Workforce recruitment, training, and education of more racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse practitioners will be essential to reduce these disparities.

Psychologists by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Note: White, Black, Asian, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. Psychologists include practitioners of general psychology, developmental and child (more...)

- In 2019, the vast majority of psychologists (79%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 26 ).

- Hispanic people,10%,

- Asian people, 4%, and

- Multiracial people, 2.0%.

Although the outpatient substance use treatment field has seen an increase in referrals of Black and Hispanic clients, there have been limited changes in the diversity of the workforce. This discordance may exacerbate treatment disparities experienced by these clients. 41

Substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors by race/ethnicity (left) and U.S. population racial and ethnic distribution (right), 2019. Key: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native. Note: White, Black, Asian, AI/AN, and >1 Race are non-Hispanic. (more...)

- In 2019, the majority of substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors (58%) were non-Hispanic White ( Figure 27 ).

- Black people, 18%,

- Hispanic people, 16 %,

- Asian people, 4%,

- AI/AN people, 1%.

- Overview of Healthcare Expenditures in the United States

- Hospital care expenditures grew by 6.2% to $1.2 trillion in 2019, faster than the 4.2% growth in 2018.

- Physician and clinical services expenditures grew 4.6% to $772.1 billion in 2019, a faster growth than the 4.0% in 2018.

- Prescription drug spending increased by 5.7% to $369.7 billion in 2019, faster than the 3.8% growth in 2018.

- In 2019, the federal government (29%) and households (28%) each accounted for the largest shares of healthcare spending, followed by private businesses (19%), state and local governments (16%), and other private revenues (7%). Federal government spending on health accelerated in 2019, increasing 5.8% after 5.4% growth in 2018.

Personal Healthcare Expenditures

“Personal healthcare expenditures” measures the total amount spent to treat individuals with specific medical conditions. It comprises all of the medical goods and services used to treat or prevent a specific disease or condition in a specific person. These include hospital care; professional services; other health, residential, and personal care; home health care; nursing care facilities and continuing care retirement communities; and retail outlet sales of medical products. 43

Distribution of personal healthcare expenditures by type of expenditure, 2019. Key: CCRCs = continuing care retirement communities. Note: Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding. Personal healthcare expenditures are outlays for goods and services (more...)

- In 2019, hospital care expenditures were $1.192 trillion, nearly 40% of personal healthcare expenditures ( Figure 28 ).

- Expenditures for physician and clinical services were $772.1 billion, almost one-fourth of personal healthcare expenditures.

- Prescription drug expenditures were $369.7 billion, 10% of personal healthcare expenditures.

- Expenditures for dental services were $143.2 billion, 5% of personal healthcare expenditures.

- Nursing care facility expenditures were $172.7 billion and home health care expenditures were $113.5 billion, 5% and 4% of personal healthcare expenditures, respectively.

Personal healthcare expenditures, by source of funds, 2019. Note: Data are available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Personal healthcare (more...)

- In 2019, private insurance accounted for 33% of personal healthcare expenditures, followed by Medicare (23%), Medicaid (17%), and out of pocket (13%) ( Figure 29 ).

- Private insurance accounted for 37% of hospital, 40% of physician, 15% of home health, 10% of nursing home, 43% of dental, and 45% of prescription drug expenditures.

- Medicare accounted for 27% of hospital, 25% of physician, 39% of home health, 22% of nursing home, 1.0% of dental, and 28% of prescription drug expenditures.

- Medicaid accounted for 17% of hospital, 11% of physician, 32% of home health, 29% of nursing home, 10% of dental, and 9% of prescription drug expenditures.

- Out-of-pocket payments accounted for 3% of hospital, 8% of physician, 11% of home health, 26% of nursing home, 42% of dental, and 15% of prescription drug expenditures.

Prescription drug expenditures, by source of funds, 2019. Note: Data are available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Percentages do (more...)

- Private health insurance companies accounted for 44.5% of retail drug expenses ($164.6 billion in 2019).

- Medicare accounted for 28.3% of retail drug expenses ($104.6 billion).

- Medicaid accounted for 8.5% of retail drug expenses ($31.4 billion).

- Other health insurance programs accounted for 3.0% of retail drug expenses ($11.0 billion).

Other third-party payers had the smallest percentage of costs (1.2%), which represented $4.3 billion in retail drug costs.

- Variation in Healthcare Quality

State-level analysis included 182 measures for which state data were available. Of these measures, 140 are core measures and 42 are supplemental measures from the National CAHPS Benchmarking Database (NCBD), which provides state data for core measures with MEPS national data only.

The state healthcare quality analysis included all 182 measures, and the state disparities analysis included 108 measures for which state-by-race or state-by-ethnicity data were available. State-level data are also available for 136 supplemental measures. These data are available from the Data Query tool on the NHQDR website but are not included in data analysis.

State-level data show that healthcare quality and disparities vary widely depending on state and region. Although a state may perform well in overall quality, the same state may face significant disparities in healthcare access or disparities within specific areas of quality.

Overall quality of care, by state, 2015–2020. Note: All state-level measures with data were used to compute an overall quality score for each state based on the number of quality measures above, at, or below the average across all states. States (more...)

- Some states in the Northeast (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island), some in the Midwest (Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin), two states in the West (Colorado and Utah), and North Carolina and Kentucky had the highest overall quality scores.

- Some Southern and Southwestern states (District of Columbia, viii Florida, Georgia, New Mexico, and Texas), two Western states (California and Nevada), some Northwestern states (Montana, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming), and New York and Alaska had the lowest overall quality scores.

- More information about the measures and data sources included in the creation of this map can be found in Appendix C .

- More information about healthcare quality in each state can be found on the NHQDR website, https://datatools .ahrq.gov/nhqdr .

- Variation in Disparities in Healthcare

The disparities map ( Figure 32 ) shows average differences in quality of care for Black, Hispanic, Asian, NHPI, AI/AN, and multiracial people compared with the reference group, non-Hispanic White or White people. States with fewer than 50 data points are excluded.

Average differences in quality of care for Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and multiracial people compared with White people, by state, 2018–2019. Note: All measures in this report that (more...)

- Some Western and Midwestern states (Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, and Washington), several Southern states (Kentucky, Mississippi, Virginia, and West Virginia), and Maine had the fewest racial and ethnic disparities overall.

- Several Northeastern states (Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania), two Midwestern states (Illinois and Ohio), two Southern States (Louisiana and Tennessee), and Texas had the most racial and ethnic disparities overall.

Major updates made to three data sources since 2018, specifically the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, and National Health Interview Survey, have had an outsized impact on what the 2021 NHQDR can include. Trend data were provided in prior versions of the NHQDR but were not directly comparable for almost half of the core measures at the time this report was developed. Therefore, the 2021 NHQDR does not include a summary figure showing all trend measures or all changes in disparities. The report includes summary figures for trends and change in disparities for some populations and the results for individual measures.

More information on providers that may be eligible to become CAHs and the criteria a Medicare-participating hospital must meet to be designated by CMS as a CAH can be found at https://www .cms.gov/Medicare /Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification /CertificationandComplianc/CAHs .

All the criteria for a Medicare-participating hospital to be designated by CMS as a CAH can be found at https://www .cms.gov/Medicare /Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification /CertificationandComplianc/CAHs .

The most recent data year available is 2018 from the Association of American Medical Colleges, the current source for workforce data broken down by both race/ethnicity and sex.

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration combines data for Asian and Pacific Islander populations, which include Native Hawaiian populations.

For purposes of this report, the District of Columbia is treated as a state.

This document is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission. Citation of the source is appreciated.