- Close ×

- ASWB Exam Prep Overview

- LCSW Exam Prep (ASWB Clinical Exam)

- LMSW Exam Prep (ASWB Masters Exam)

- LSW Exam Prep (ASWB Bachelors Exam)

- California Law and Ethics Exam Practice

- Free Practice Test

- Get Started

- Free Study Guide

- Printed Exams

- Testimonials

The social worker's role in the problem-solving process

First, a question: what's that mean exactly?

The Problem-Solving Process

The problem-solving process is a systematic approach used to identify, analyze, and resolve issues or challenges. It typically involves several steps:

Identification of the Problem: The first step is to clearly define and identify the problem or issue that needs to be addressed. This involves understanding the symptoms and root causes of the problem, as well as its impact on individuals, groups, or the community.

Gathering Information: Once the problem is identified, relevant information and data are gathered to gain a deeper understanding of the issue. This may involve conducting research, collecting data, or consulting with stakeholders who are affected by or have expertise in the problem.

Analysis of the Problem: In this step, the information collected is analyzed to identify patterns, underlying causes, and contributing factors to the problem. This helps in developing a comprehensive understanding of the problem and determining possible solutions.

Generation of Solutions: Based on the analysis, a range of potential solutions or strategies is generated to address the problem. Brainstorming, creative thinking techniques, and consultation with others may be used to generate diverse options.

Evaluation of Solutions: Each potential solution is evaluated based on its feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact. This involves considering factors such as available resources, potential risks, and alignment with goals and values.

Decision-Making: After evaluating the various solutions, a decision is made regarding which solution or combination of solutions to implement. This decision-making process may involve weighing the pros and cons of each option and considering input from stakeholders.

Implementation: Once a decision is made, the chosen solution is put into action. This may involve developing an action plan, allocating resources, and assigning responsibilities to ensure the effective implementation of the solution.

Monitoring and Evaluation: Throughout the implementation process, progress is monitored, and the effectiveness of the solution is evaluated. This allows for adjustments to be made as needed and ensures that the desired outcomes are being achieved.

Reflection and Learning: After the problem-solving process is complete, it's important to reflect on what was learned from the experience. This involves identifying strengths and weaknesses in the process, as well as any lessons learned that can be applied to future challenges.

The Social Worker's Role

Okay, so social worker's assist with all of that. The trickiest part (and the part most likely to show up on the ASWB exam) is decision making. Do social workers make decisions for clients, give advice, gently suggest...? The answer is no, sometimes, and sort-of. Client self-determination is a key component of social work ethics. Problem-solving and decision-making in social work are guided by these general principles:

Client-Centered Approach: Social workers prioritize the autonomy and self-determination of their clients. They empower clients to make informed decisions by providing them with information, options, and support rather than imposing their own opinions or solutions.

Collaborative Problem-Solving: Social workers engage in collaborative problem-solving with their clients. They work together to explore the client's concerns, goals, and available resources, and then develop strategies and plans of action that are mutually agreed upon.

Strengths-Based Perspective: Social workers focus on identifying and building upon the strengths and resources of their clients. They help clients recognize their own abilities and resilience, which can empower them to find solutions to their problems.

Non-Directive Approach: While social workers may offer suggestions or recommendations, they typically do so in a non-directive manner. They encourage clients to explore various options and consequences, and they respect the client's ultimate decisions.

Cultural Sensitivity: Social workers are sensitive to the cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and values of their clients. They recognize that advice-giving may need to be tailored to align with the cultural norms and preferences of the client.

Ethical Considerations: Social workers adhere to ethical principles, including the obligation to do no harm, maintain confidentiality, and respect the dignity and rights of their clients. They avoid giving advice that may potentially harm or exploit their clients.

Professional Boundaries: Social workers maintain professional boundaries when giving advice, ensuring that their recommendations are based on professional expertise and not influenced by personal biases or conflicts of interest.

On the Exam

ASWB exam questions on this material may look like this:

- During which step of the problem-solving process are potential solutions evaluated based on feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact?

- In the problem-solving process, what is the purpose of gathering information?

- Which ethical principle guides social workers in giving advice during the problem-solving process?

Or may be a vignette in which client self-determination (eg re sleeping outside) is paramount.

Get ready for questions on this topic and many, many others with SWTP's full-length practice tests. Problem: need to prepare for the social work licensing exam. Solution: practice!

Get Started Now .

March 15, 2024.

Right now, get SWTP's online practice exams at a reduced price. Just $39 . Get additional savings when buying more than one exam at a time-- less than $30 per exam!

Keep going till you pass. Extensions are free.

To receive our free study guide and get started!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 1 Chapter 1: Social Work and “Ways of Knowing”

This chapter is largely about social work knowledge—how social work professionals come to “know” what we know, and how that knowledge can be leveraged to inform practice. Thinking about what we know and how we come to know it is critically important to understanding social work values, beliefs, and practices. This means critically thinking about the sources and types of knowledge on which social workers rely, and the implications of relying on these different sources and types of knowledge.

What you will learn from reading this chapter is:

- The philosophical roots of different approaches to scientific knowledge on which social workers rely (epistemologies);

- Different types and sources of knowledge (“ways of knowing”);

- Strengths and limitations of various “ways of knowing” social workers encounter and might apply in understanding social problems and diverse populations;

- Principles of critical thinking;

- Distinctions between science, pseudoscience, and opinions.

Thinking about Knowledge

The study of knowledge and knowing about the world around us called epistemology , and represents one of the major branches of philosophy. Throughout much of human history, philosophers have dedicated a great deal of thought to understanding knowledge and its role in the human experience. Ancient Greek and western philosophers like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, as well as those who came before and after them, made lasting contributions to the way we think about knowledge and its applications in daily life. A great deal of this western philosophical activity centered around building knowledge based on facts and provable “truths,” rather than spirituality, mythology, and religion. These philosophical efforts contributed greatly to the evolution of rational thought, science, theory, and scientific methods that we use in our everyday and professional lives to make sense of the world around us. Much of the science on which we often rely to find answers to perplexing questions is derived from a philosophical position called positivism . Positivism essentially involves adopting a stance where valid knowledge, or “truth,” is based on systematic scientific evidence and proof: in order to be positive about knowing something, that something must be proven through scientific evidence. Scientific evidence, developed through a positivism lens, results from a rational, logically planned process identified as the scientific process. Similarly, empiricism is about proven knowledge, but contends that proof also may come through the application of logic or through direct observable evidence. In our SWK 3401 and SWK 3402 coursework you will be exposed to many of the methods that investigators apply in scientifically answering questions about social problems, diverse populations, social phenomena, and social work interventions. But science is not the only way of knowing, and it is important for social workers to understand the place science occupies in an array of ways knowledge is developed and applied.

Much of what is taught in the United States about knowledge and epistemology is somewhat constrained by traditions of western philosophy. Challenges to these constraints emerged in the literature during the 1990s under the headings of naturalistic epistemology, anthroepistemology, and ethnoepistemology (e.g., Maffie, 1990; 1995). An important contribution to our understanding of knowledge is an anthropological appreciation that knowledge is constructed within a cultural context. This is quite different from the positivist perspective concerning single, provable truths that are waiting to be discovered.

“Anthroepistemology views epistemology as an historically and contingently constituted phenomenon, the nature, aims, and province of which are to be understood in terms of the life context in which epistemology is organically rooted and sustained rather than in terms of divine imperative, rationality per se, or pre-existing epistemic facts or principles” (Maffie, 1995, p. 223).

In other words, what we know, how we come to know it, and how we think about knowing all are influenced by the personal, historical, and cultural contexts surrounding our experiences. For example, consider what you “know” about deafness as a disability. This deficiency perspective comes from the cultural context of having lived in a hearing world. However, members of the Deaf community offer a different perspective: living within deaf culture and linguistic structures (e.g., using American Sign Language to communicate) conveys specific social and cultural implications for human development, behavior, thinking, and worldview (Jones, 2002). These implications are viewed the same way other cultures are viewed—as cultural differences when being compared, not as deficiencies, or “otherness.” This diversity of experience perspective (rather than a disability perspective) could be applied to other topics, such as autism, reflecting human neurodiversity rather than a disorder.

Implications for Social Work.

One implication of this observation might be that social workers should expect worldviews held by individuals with vastly different lived experiences to differ, too. Well over 100 years ago, the philosopher and psychologist William James (1902), discussing the varieties of religious experience, observed:

“Does it not appear as if one who lived more habitually on one side of the pain-threshold might need a different sort of religion from one who habitually lived on the other?” (p. 105).

In broader terms, social workers strive to understand diversity in its many forms. We appreciate that diverse life contexts, experiences, opportunities, and biology all interact in complex ways in contributing to diverse outcomes. These differences include differences in knowledge and understanding of the world—differences, not deficiencies. For example, we understand that the elements of a parenting education program delivered to two-parent, well-resourced, privileged, reasonably empowered families of one racial or ethnic background may be grossly inappropriate for families existing in a far different reality, facing very different challenges, very differently resourced or privileged, and responding to different experiences of discrimination, oppression, exploitation, threats of violence, and micro-aggression. The pre-existing knowledge different families bring to their parenting situations and their parenting knowledge needs differ significantly—even their parenting goals, approaches, and means of learning and developing knowledge may differ.

Social workers who adopt an anthropological, ethnoepistemology perspective are open to considering the beliefs of ordinary people around the world alongside those of leaders, academics, scientists, colleagues, and authorities. This line of thought encourages us to reflect on all epistemologies—wherever in the world they are practiced and by whomever they are practiced. Western philosophy, rational logic, and science are situated within this context—as one of the multitude of epistemologies that exist, not as the first or the most significant, but simply as one of many. These perspectives contribute to social work having a rich array of research methodologies available for understanding social problems, diverse populations, and social phenomena. A positivism/empiricism perspective contributes to many of our quantitative research methodologies; an anthropological, ethnoepistemology perspective underlies many qualitative research methods.

This philosophical background is relevant to social work education for several reasons:

- Social work professionals engage with individuals from many diverse backgrounds and social contexts. This means that we encounter many different ways of knowing and great diversity of belief among the people with whom we interact. Colleagues, professionals from other disciplines, clients, community members, agencies, policy decision makers and others all have their own understanding about the world we live in, and these understandings often differ in critically significant ways. We cannot work effectively with others if we do not have an appreciation for this diversity of understanding, thinking, and believing.

- To be effective in our interactions, social workers also need to understand and critically evaluate our own personal and professional epistemologies, and what we “know” about social work problems, diverse populations, and social phenomena. This idea fits into the social work practice mandate to “know yourself” (e.g., see Birkenmaier & Berg-Wegner, 2017).

- Significant differences exist between the philosophies that underlie different scientific methodologies. Rational logic underlies quantitative methodologies and ethnoepistemology underlies on qualitative methodologies. These differences contribute to complexity around the qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (integration of qualitative and quantitative) choices made by investigators whose work helps us understand social work problems, diverse populations, and social phenomena.

Thinking about Different Sources and Types of Knowledge

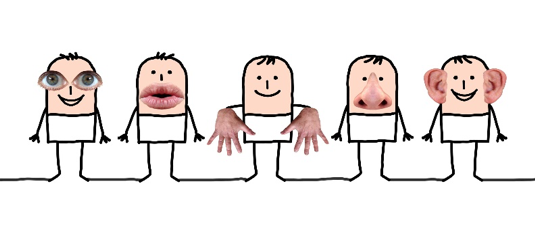

Humans have many different ways of developing our knowledge about the world around us. Think about how young children come to understand the world and all kinds of phenomena they experience. First, they utilize all five senses to explore the world: vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. For example, a baby might hear food being prepared, see and smell the food, touch it and taste it.

Sensory evidence provides people of all ages with a great deal of experiential knowledge about the physical and social world.

Second, people engage in internal mental operations we call cognition —they engage in thinking and problem solving—to create meaning from their experiences. To continue our example, it is through these internal mental experiences that babies develop their ideas about food. Some of their conclusions are effective, while their other conclusions are inaccurate; these guesses need to be revised through further experience and cognition. For example, this toddler learned (the hard way) to understand that paint is not food. These cognitions may take a few trials to accurately emerge.

Third, knowledge comes through basic learning principles involving reinforcement and punishment of behavior, as well as observational learning of others’ behaviors. Young children often conduct repeated experiments to develop knowledge concerning the basic principles by which the physical and social world operate. For example, a young child might experiment with using “naughty” swear words under different conditions. The first few times, it might simply be a case of copying a role model (such as parents, siblings, peers, or television/movie/music performers). Based on the way the social world responds to these experimental uses of language, the child may continue to experiment with using these words under different circumstances. This behavior might get one response from siblings or other children (laughing, giggling, and “Oooohhhhh!” responses), a different response from a parent or teacher (a corrective message or scolding response), and yet a different response still from a harried caregiver (simply ignoring the behavior). We may consider this child to be an “organic” scientist, naturally developing a complex understanding about the way the social world works.

People of all ages rely on these multiple ways of knowing about the world—experiential, cognitive, and experimental. What additional ways of knowing are important for social workers to understand? Answers to this question can help us better understand the diverse people with whom we engage and can help us better understand our own sources of knowledge as applied in professional practice. By the way, thinking about our thinking is called metacognition —having an awareness of your own processes of thinking and knowing.

Ways of Knowing.

Textbooks about the Theory of Knowledge offer various ways through which human beings derive knowledge (see for example IB, n.d.; TOK network, n.d). These ways of knowing include:

- Sensory perception

- Imagination and Intuition

Let’s examine each of these ways of knowing in a little more detail, and consider their implications for knowledge in social work. It is helpful to think about how we might consider our use of each source of knowledge to avoid running “off into a ditch of wrong conclusions” (Schick & Vaughn, 2010, p. 4).

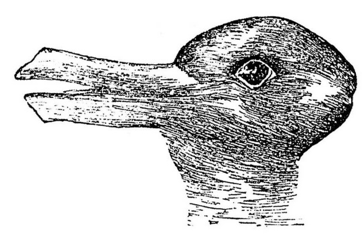

Sensory perception and selective attention. We have already considered the ways that individuals across the lifespan come to know about the world through engaging their five senses. In general, human beings rely on information acquired through their senses as being reliable evidence. While this is generally appropriate, there are caveats to consider. First, knowledge developed through our sensory experiences are influenced by the degree to which our sensory and neurological systems are intact and functional. There exists a great degree of variability in different individuals’ vision, for example. We can reduce the variability to some degree with adaptive aides like eye glasses, contact lenses, adaptive screen readers, and tools for sensing color by persons who are “color blind.” But, it is important to recognize that perception is highly individualistic. You may have played with optical illusions in the past .Or, you may recall the 2015 social media storm created by the “What color is this dress?” dilemma (#thedress, #whiteandgold, and #blackandblue). Or, for example, when you look at this image, what do you see?

You might see a duck head looking to the left, a rabbit head looking to the right, both, or neither. In both the dress and duck/rabbit examples, different individuals perceive the same stimuli in different ways.

This raises the question: can we trust our own perceptions to represent truth? In our everyday lives, we rely heavily on our perceptions without thinking about them at all. Occasionally, we might experience the thought: “I can’t believe my own eyes” or “I can’t believe what I am hearing.” Between these extremes, social workers often experience the need to confirm our perceptions and checking with others about theirs.

One reason why our perceptions might not match the perceptions of another person has to do with what we each pay attention to. Everyone practices a degree of selective attention . For example, as you are reading this material, are you aware of the feel of the room temperature, the sound of the air circulation, or the amount of light in the room? This information is all available to you, and you might have paid attention to them when you first sat down to read. But, you stopped being consciously aware of them as they remained steady and irrelevant to the task of reading. If any conditions changed, you might have noticed them again. But, it is human nature to ignore a great deal of the information collected by our sensory systems as being irrelevant. A source of individual difference is the degree to which they attend to different types of information. For example, as you ride through a neighborhood you might notice the location of different food or coffee establishments. Someone in recovery from an alcohol use disorder, taking the very same ride, might attend to the different liquor advertisements that could trigger a craving and warrant avoiding. You both experienced the same environment, but through selective attention you each came to know it differently.

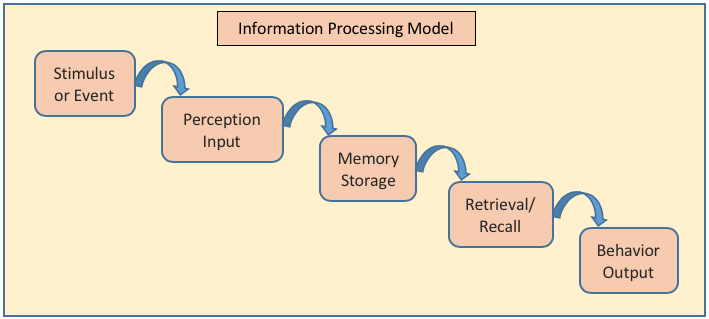

Memory and memory bias. You might argue that memory is not really a way of knowing, that it is only a tool in the process of knowing. You would be partially correct in this argument—it is a tool in the process. However, it is not ONLY a tool. Memory is an integral and dynamic part of the human mind’s information processing system. The diagram below represents steps in human information processing. The process begins with the sensory systems discussed earlier. But, look at what happens to those sensory perceptions next:

In terms of the information processing model, once something has been perceived or an event has been experienced by an individual (perception), the perception moves to the memory system. A perception first moves into short-term memory as something the person is actively aware of or thinking about. The short-term memory “buffer” is typically limited in space to around 5-7 items at a time and lasts for only about 18-30 seconds. After that, the memory either is cleared from the “buffer” zone and forgotten forever, or it is moved to longer term memory. If a memory is not converted into a long-term memory, it cannot be retrieved later.

The long-term memory system has a tremendous storage capacity and can store lasting memories. However, stored memories are relatively dynamic, rather than static, in nature. Memories are remarkably susceptible to change through the incorporation of new information. Human memory does not work like a video camera that can be replayed to show exactly what was originally experienced. Instead, recalling or retrieving memory for an event or experience happens through a process of recreation. In this process, other factors and information become woven into the result, making it a less-than-perfect depiction of the original experience. Consider research about the ways that additional (mis)information affects what individuals recalled about a story presented to them in a memory study (Wagner & Skowronski, 2017). Study participants reported “remembering” new facts presented later as having been part of the original story—these later facts became false memories of the original experience. False or erroneous memories were more likely when the original facts were scarce (versus robust), the new information seemed true (rather than questionably reliable), and the person was highly motivated to retell the story. These conditions provoked the human mind to fill in gaps with logical information.

The nature of a memory also may be (re)shaped by internally generated cognition based on our pre-existing understanding of the world—our thoughts. This process makes memories more relevant to the individual person but is a significant source of memory bias. We often use our own thoughts, ideas, cognitions, and other experiences to fill in knowledge gaps around what we remember from direct experiences. For example, you may have learned about the poor reliability of eyewitness testimony—what is remembered by the eyewitness is influenced by how the situation is understood, making it susceptible to distortion from beliefs, stereotypes, prejudice, and past experiences. This explains why convenience stores often have rulers painted on the doorframe: if a crime occurs, a shorter witness might recall a person’s height as being tall, and a taller witness might recall the person’s height as being short. The yardstick allows more objective, undistorted recall of the facts.

Memory reshapes itself over time, and sometimes people lose the connections needed to retrieve a memory. As a result, what we “think” we know and remember is influenced by other external and internal information.

Language. Like memory, language is both a product and producer of knowledge. Language is a created set of signs and symbols with meaning that exists because of conventional agreement on that meaning. Language helps describe what we know about the world, both for ourselves and to communicate with others. But, language also has the power to shape our understanding, as well. Linguistic determinism is about how the structures of language constrain or place boundaries on human knowledge.

Consider, for example, the limitations imposed on our understanding of the social world when language was limited to the binary categories of male and female used in describing gender. Our language being structured in this binary fashion leads individuals to think about gender only in this manner. Conventional agreement is extending to include terms like agender, androgynous, bigender, binary, cisgender, gender expansive, gender fluid, gender non-conforming, gender questioning, genderqueer, misgender, non-binary, passing, queer, transgender, transitioning, transsexual person, two-spirit (see Adams, 2017). With the addition of multiple descriptive terms to our language, it becomes easier to have a more contextual, complex, non-binary understanding of the diverse nature of gender. Language is one mechanism by which culture has a powerful influence on knowledge.

Reason and logic . Humans may come to “know” something through their own internal cognitive processing and introspection about it. Logic and reasoning represent thought processes that can result in knowledge. You may recall the important piece of reasoned logic offered by Rene Descartes (1637): “I think therefore I am.” This piece of reasoning was the first assumption underlying his building of an orderly system of “truth” where one conclusion could be deduced from other conclusions: deductive reasoning . In deductive reasoning, we develop a specific conclusion out of assembling a set of general, truthful principles (see Table 1-1). The specific conclusion is only as good as the general principles on which it is based—if any of the underlying premises are false, the conclusion may be incorrect, as well. The conclusion might also be incorrect if the premises are assembled incorrectly. On the other hand, inductive reasoning involves assembling a set of specific observations or premises into a general conclusion or generalized principle (see Table 1-1). Inductive reasoning is a case of applying cause and effect logic where a conclusion is based on a series of observations. For example, estimating future population numbers on the basis of the trend observed from a series of past population numbers (Kahn Academy example from www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=43&v=GEId0GonOZM ). Abductive reasoning is not entirely inductive or deductive in nature. It generates a hypothesis based on a set of incomplete observations (inductive reasoning) and then proceeds to examine that hypothesis through deductive logic.

Table 1. Examples of deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning from Live Science https://www.livescience.com/21569-deduction-vs-induction.html

| Spiders have 8 legs. A black widow is a spider. Conclusion: black widows have 8 legs | Pulling a series of coins from a coin purse, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th is each a penny. Conclusion: the 5th will be a penny, too. |

| Entering your room, you find that your loose papers are all over the place. You see that the window is open. Conclusion: the wind blew the papers around. But, you consider alternative explanations (another person came in and threw the papers around) and settle on the most probable/likely conclusion. | |

A person does not actually need to witness or experience an event to draw logically reasoned conclusions about what is likely. For example, a social worker may be trained in the knowledge that persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in their histories have a greater likelihood than the general population to experience problems in family relationships, unemployment, social isolation, homelessness, incarceration, depression, and suicide risk (Mantell, et al, 2017). In meeting a client with a TBI history, the social worker might reason that it is important to screen for the risk of each of these problems. The social worker does not need to wait for these problems to be observed; the knowledge gained through reasoning and logic is sufficient to warrant paying attention to the possibility of their being present or emerging.

Sometimes a line of reasoning seems rational and logical, but when carefully analyzed, you see that it is not logically valid—it is fallible, or capable of being in error. A fallacious argument is an unsound argument characterized by faulty reasoning. Fallacious arguments or flawed logic can result in the development of mistaken beliefs, misconceptions, and erroneous knowledge. For example, in the 1940s to 1950s a mistaken theory of autism was offered in the professional literature (see Rimland, 1964): the “refrigerator mother” theory was that the low levels of warmth parents were observed directing to an autistic child caused the child’s autism symptoms. The logic flaw in this case was a very common error: drawing a false causal conclusion from a correlational observation. The observed parental behavior actually was a sensitive response to behavioral cues presented by the children with autism, not a cause of the autism. Thus, the “refrigerator mother” misconception was influenced by logical fallacy. Clearly, the knowledge gained through reasoning is only as good as the weakest link in the chain of ideas and logic applied.

Emotion and affect . Human feelings have a powerful influence on what we think and understand about the world around us. Another word for emotion is affect (not to be confused with effect, pronounced with an “a as in apple”). For example, the advertising, entertainment, and news media have long recognized that individuals more strongly remember information to which they have developed an emotional response. This explains why we see so many cute puppies, adorable children, attempts at humor, and dramatic disaster footage in advertising and news programming. This also is why we are more likely to remember the score of a game our favorite team played than the scores of other games. It is why we remember news events that “hit close to home” compared to other reported world events.

The strongest emotions we experience as human beings may have developed as ways to improve our individual chances for survival. For example, by avoiding experiences that elicit fear we may be avoiding danger and risk of harm. By avoiding that which we find disgusting, we may be avoiding that which could make us ill. A lot of questions surround the emotional world—the origins of emotions and what is innate versus learned, for example. One thing that research since the 1970s concerning affective education has demonstrated is that how we interpret our own and others’ emotions (affect) has a strong influence on how we behave in different situations (e.g., Baskin & Hess, 1980). Because the ability to identify and label emotions (knowledge of your own and those of other people) has such a significant impact on interpersonal interactions and behaviors, a great deal of attention has been directed towards trying to understand individual differences in “emotional intelligence” or “EQ” (see Goleman, 1995).

Faith. Religious faith is only one aspect of how faith relates to knowledge. For some individuals, religious teachings provide them with knowledge surrounding certain topics. What a person knows through faith is considered to require no further analysis or proof—that is the nature of faith. For this reason, we can include other sources of knowledge derived through faith. This includes relying on knowledge attained through information shared by a mentor, expert, or authority. Identifying someone as an authority is intensely personal and individualized. Just as “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” perceptions of another person’s expertise are relative. One person might have faith in the expert opinion shared by a parent, grandparent, sibling, or best friend. Another person might place greater faith in the opinions expressed by celebrities, sports figures, news anchors, or political leaders. Social work interns may place faith in the expertise shared by field instructors and course instructors. Social work clients often rely on the knowledge shared by others in their support or treatment group who may have experienced similar challenges in life.

Knowledge derived from experts and authority is not foolproof, however. First, there may be differences of opinion expressed by different experts. For example, legal counsel on different sides of a court case often engage expert witnesses who have diametrically opposed expert opinions. Jury members are then faced with the challenge of evaluating the experts’ qualifications to decide which opinion is more reliable. Second, the knowledge held by experts and authorities is subject to the same sources of bias and limitation as any knowledge. For example, the expertise of social work supervisors was (at least partially) influenced by their supervisors’ expertise, which was influenced by their supervisors’ expertise, and so on. What if the original was wrong from the start? Or, more likely, what if that knowledge no longer applies to the current environment? In short, faith in the knowledge of authority needs to be tempered by awareness that knowledge from these sources is fallible.

“ Arguments from authority carry little weight—‘authorities’ have made mistakes in the past and will do so again” (Sagan, 1987, p. 12).

Imagination and Intuition. Sometimes what a person “knows” is not based on external events or objects, knowledge might be generated as new ideas or concepts completely through internal processes. Imagination, creativity, and intuition are special forms of cognitive activity, resulting in the creation of unique forms of knowledge. You have probably been exposed to examples of highly imaginative, creative art, music, film, dance, or literature. Sometimes the original insights we gain from these creations make them seem like sheer genius. We might say the same thing about a person’s apparent cognitive leaps that we might call intuition: seeming to know something without being able to trace where the knowledge was derived; it comes from reasoning that happens at an unconscious level. These ways of knowing combine elements from other forms previously discussed, but in different ways: perception, memory, emotion, language, and reasoning, for example. This is what leads to that “aha” moment when a new idea is born.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.

Culture and Ways of Knowing .

Earlier, you read that language is one way that culture has a powerful influence on knowledge. The influence of culture is not only in terms of what we know, but also in terms of how we learn what we know. The book Women’s Ways of Knowing : The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind (Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, & Tarule, 1986) describes the results of a deep qualitative study of how women develop their views and knowledge. The women’s development of knowledge was heavily influenced by their cultural experiences with authority, particularly in learning from family and schools. The authors included an analysis of five different ways of knowing, outlined below. These may very well express others’ ways of knowing, based on their own experiences with majority culture, not only based on gender.

Silence . As a way of knowing, silence is an expression of “blind” obedience to authority as a means of avoiding trouble or punishment. The concept of silence refers to an absence of self-expression and personal voice. The authors indicated that individuals characterized by silence also found the use of words to be dangerous and that words were often used as weapons.

Received Knowledge. Carriers of this way of knowing rely on others for knowledge, even knowledge about themselves. They tend to learn by listening to others, lacking confidence in their own original ideas or thoughts. There is a heavy reliance on authority as a source of knowledge. As a result, thinking is characterized by an inability to tolerate ambiguity, and is concretely dualistic—everything is categorized as good or evil, us or them, and black or white with no shades in between.

Subjective Knowledge. Subjective knowledge is highly individualistic because personal experience, “inward listening” and intuition are major sources of knowledge. A sense of voice exists, expressed as personal opinion. The source of knowledge is internal, and the authority listened to is self—and this knowledge is more important than knowledge from external sources.

Procedural Knowledge. Objective approaches are applied to the process of acquiring, developing, and communicating procedural knowledge. In other words, careful observation and critical analysis are required. Knowledge can come from multiple external sources, but only after careful internal critical analysis of the arguments provided by those sources. There exists awareness that others and one’s self can be wrong, and an effort to remove the impact of feelings from the process of objective analysis.

Constructed Knowledge. This is an integrative view where both subjective and objective strategies apply to knowledge. Ambiguity is tolerated well, as are apparent contradictions in what one knows. There exists a strong, constantly developing sense of self in relation to the external world. Constructed knowledge involves belief that knowledge is relative to context and frame of reference, and a person is responsible for actively trying to understand by “examining, questioning, and developing the systems that they will use for constructing knowledge” (see https://www.colorado.edu/UCB/AcademicAffairs/ftep/publications/documents/WomensWaysofKnowing.pdf ).

Thinking about Critical Thinking

As we have seen, much of what humans “know” is susceptible to bias and distortion, often represents only partial or incomplete knowledge, and socially constructed knowledge varies as a function of the different societies constructing it. The concept of critical thinking describes approaches to knowledge and knowing that rely on disciplined, logical analysis, and knowledge that is informed by evidence. Critical thinking extends beyond simple memorization of facts and information; it involves the analysis and evaluation of information, leading to reasoned, “thought-out” judgments and conclusions. You might recognize elements of critical thinking in the procedural and constructed ways of knowing previously described. A person engaged in critical thinking expresses curiosity about the topic or issue under consideration, seeks information and evidence related to the topic or issue, is open to new ideas, has a “healthy questioning attitude” about new information, and is humbly able to admit that a previously held opinion or idea was wrong when faced with new, contradictory information or evidence (DeLecce, n.d.).

Carl Sagan (1987) argued that critical thinking is, “the ability to construct, and to understand, a reasoned argument and—especially important—to recognize a fallacious or fraudulent argument” (p. 12). To understand what a fallacious argument might be, we can examine the concepts of logic: a branch of philosophy dedicated to developing the principles of rational thought. Sagan’s (1987) discussion of critical thinking indicated that it does not matter how much we might like the conclusions drawn from a train of reasoning; what matters is the extent to which the chain of logic “works.” He also contended that untestable propositions are worthless—if you cannot check out the assertions, it is not worthwhile considering. However, Sagan also reminded readers that critical thinking and science itself exist in a state of constant tension between two apparently contradictory attitudes:

“an openness to new ideas, no matter how bizarre or counterintuitive they may be, and the most ruthless skeptical scrutiny of all ideas, old and new. This is how deep truths are winnowed from deep nonsense” (Sagan, 1987, p. 12).

This quote describes the quality of a critical thinker mentioned earlier: simultaneously being open-minded and having a reasonable degree of skepticism about new information or ideas.

In terms of social work and social work education, being able to apply critical thinking skills, particularly “the principles of logic, scientific inquiry, and reasoned discernment” has been a curriculum expectation since the 1990s (Mathias, 2015, p. 457). The characteristics of critical thinking in social work include rational, reasoned thinking about complex, “fuzzy” problems that lack at least some elements of relevant information and readily apparent solutions (Mathias, 2015; Milner & Wolfer, 2014). Critical thinking in social work practice involves initially suspending judgment, then engaging in the process of generating relevant questions, considering assumptions, seeking information and divergent viewpoints, and applying logical, creative problem solving.

What is (Scientific) Evidence?

Strong arguments appear in the published literature concerning the importance of scientific reasoning in social work practice, and its significance to critical thinking and problem solving (e.g., see Gambrill, 1997; Gibbs & Gambrill, 1999; Gibbs et al., 1995). Francis Bacon is credited with presenting an approach to scientific method that is a foundation for science today (Dick, 1955). The Merriam-Webster definition of scientific method ( https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scientific%20method ) is:

Principles and procedures for the systematic pursuit of knowledge involving the recognition and formulation of a problem, the collection of data though observation and experiment, and the formulation and testing of hypotheses.

What you may find interesting is that different authors suggest different numbers of steps in the process called scientific method—between four and ten! Let’s look at what these descriptions have in common:

Step 1. It all begins with an observation about something that arouses curiosity. For example, a social work investigator and her colleague observed an emerging population of people who rely on emergency food pantry support for relatively long periods of time—despite the programs’ intended period of emergency support being relatively short-term (Kaiser & Cafer, 2016).

Step 2. The observation leads the curious social worker to develop a specific research question. In our example, the investigators asked what might be “the differences, particularly in food security status and use of federal support programs, between traditional, short-term emergency pantry users and an emerging population of long-term users” (Kaiser & Cafer, 2016, p. 46).

Step 3. Out of their questions, the social work scientist develops hypotheses. This may come from a review of existing knowledge about the topic—knowledge that is relevant but may not be sufficient to directly answer the question(s) developed in step 2. In our food security example, the investigators reviewed information from literature, community practice, and community sources to help identify key dimensions to explore. The hypothesis was, essentially, that exploring three factors would be informative: longevity, regularity, and trends of food pantry use.

Step 4. The social work scientist develops a systematic experiment or other means of systematically collecting data to answer the research question(s) or test the research hypotheses from steps 2 and 3. Kaiser and Cafer (2016) described their research methodology for randomly selecting their sample of study participants, their research variables and measurement tools, and their data collection procedures.

Step 5. The social worker will analyze the collected data and draw conclusions which answer the research question. This analysis not only includes the results of the study, but also an assessment of the study’s limitations of the methods used for the knowledge developed and the implications of the study findings. Our working example from the food security study described the approaches to data analysis that were used. They found that almost 67% of 3,691 food pantry users were long-term users, most commonly female and white. Being a persistent user (versus short-term user) was predicted by having Social Security, retirement, pension, or SSI/disability payment income. Also, the probability of being a persistent pantry user increased with participant age. The authors also discussed other patterns in use as related to some of the other study variables and the implications related to food security and economic vulnerability (Kaiser & Cafer, 2016).

Step 6. Social work scientists share their resulting knowledge with colleagues and others through professional presentations, training sessions, and professional publications. As noted in the reference list to this module, the investigators in our study example published their findings in a professional journal (see Kaiser & Cafer, 2016).

Step 7. The social work scientist then may ask new, related questions, and progress through the stages anew. In our food security example, the authors concluded with a new question: would raising minimum wage or establishing a living wage be a better means of supporting families in the precarious position of long-term dependence on emergency food pantry support?

As you can see, the scientific process potentially incorporates multiple sources of knowledge that we have discussed in this module and allows for inclusion of various methods of investigation depending on the nature of the research questions being asked. The result of quality science, regardless of methodology, is called research or scientific evidence.

In an interview where he was asked if religion and science could ever be reconciled, Stephen Hawking responded:

“There is a fundamental difference between religion, which is based on authority, [and] science, which is based on observation and reason. Science will win because it works.”

It may not be necessary to continue pitting these two ways of knowing against each other. Engaging in science involves multiple ways of knowing. Scientific activity requires a certain degree of imagination about which might be true, rational reasoning about how to demonstrate what might be true, perception and observation of what is happening, memory about what has happened in the past, language to communicate about the process and results, an emotional investment in what is being explored, (sometimes) a certain degree of intuition, and faith in the scientific process and what has come before. Acknowledging the collaborative, constructive, dynamic nature of scientific knowledge development, consider a quote Sir Isaac Newton borrowed from an earlier popular saying:

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

This does not mean always having noncritical faith in the results of science, however. Scientific results are wrong sometimes. Sometimes scientific results are inconsistent. Sometimes scientific results are difficult to interpret. For example, are eating eggs bad for you? In the early 1970s, a link between cholesterol levels in the body and heart disease was detected. The advice coming from that observation was that people should limit their consumption of cholesterol-containing foods (like eggs) to prevent heart disease. However, this conclusion was based on faulty logic: eating cholesterol was not the cause of the elevated cholesterol levels; cholesterol was being produced by the body. Further research indicated no increased risk of heart disease with eating eggs; the elevated cholesterol problem stems from other unhealthy behavior patterns. This example demonstrates the serial, sequential, accumulating nature of scientific knowledge where previous assumptions and conclusions are questioned and tested in further research. We need to accept a degree of uncertainty as complex problems are unraveled, because science is imperfect. Again, quoting Carl Sagan (1987):

“Of course, scientists make mistakes in trying to understand the world, but there is a built-in error-correcting mechanism: The collective enterprise of creative thinking and skeptical thinking together keeps the field on track” (p. 12).

Critically important is that science be conducted and shared with integrity. Research integrity concerns conducting all aspects of research with honesty, fairness, and accuracy. This includes objectively examining data, being guided by results rather than preconceived notions, and accurately reporting results and implications. Research integrity , or “good” science means that a study’s methods and results can be objectively evaluated by others, and the results can be replicated when a study is repeated by others. Science nerds enjoy the playfulness presented in the scientific humor magazine called The Journal of Irreproducible Results ( www.jir.com ).

Take a moment to complete the following activity. For each statement, decide if it is accurate (True) or not (False).

Imperfect Science versus Pseudoscience. Even “good” science has certain limitations, imperfections, and uncertainties. For example, conclusions drawn from statistical analyses are always based on probability. In later modules you will learn what it means when a statistical test has p <.05 and about the 95% confidence interval (CI) of a statistical value. In practical terms, this means that we cannot be 100% certain that conclusions drawn from any one study’s statistical results are accurate. While accepting that we should not engage in unquestioning acceptance even of “good” science, it is even more important to avoid unquestioning acceptance of information offered through “poor” science. Especially, it is important to recognize what is being presented as scientific knowledge when it is not science. By way of introducing the importance of scientific data and statistics, Professor Michael Starbird (2006, p. 12) introduced a famous quote by the author Mark Twain:

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

Professor Starbird’s response was:

“It is easy to lie with statistics, but it is easier to lie without them.”

Pseudoscience is about information that pretends to be based on science when it is not. This includes practices that are claimed to be based on scientific evidence when the “evidence” surrounding their use was gathered outside of appropriate scientific methods. You may have learned about “snake oil salesmen” from our country’s early history—people who fraudulently sold products with (usually secret) ingredients having unverifiable or questionable benefits for curing health problems—these products often caused more harm than cure! The pseudoscientific “evidence” used in marketing these products often included (unverifiable) expert opinions or anecdotal evidence from “satisfied” customers. See the historical advertisement about Wizard Oil and all the ills that it will cure: rheumatism (joint pain), neuralgia (nerve pain), toothache, headache, diphtheria, sore throat, lame back, sprains, bruises, corns, cramps, colic, diarrhea, and all pain and inflammation. The product was 65% alcohol and other active ingredients included turpentine, ammonia, capsicum, camphor, gum camphor, fir oil, sassafras oil, cajeput oil, thyme oil, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Fortunately, Wizard Oil was a liniment, applied topically and not consumed orally.

What does this look like in present times? We still, to this day, have people relying on unsubstantiated products and treatment techniques, much of which can be identified as “quackery.” For example, 9% of out-of-pocket health care spending in the United States pays for complementary health approaches (e.g., vitamins, dietary supplements, natural product supplements and alternative practitioners): over $30 billion (Nahin, Barnes, & Stussman, 2016). Many alternative and complementary health approaches lack a strong scientific evidence base—that does not necessarily mean that they offer no health benefits, but it may be that they do not help and sometimes they cause harm, especially with overuse. Proponents of these approaches adopt what Gambrill and Gibbs (2017) refer to as a “casual approach” to evidence, where weak evidence is accepted equally to strong evidence, and an open mind is equated with being non-critical.

Three reasons why this matters in social work (and other professions) are:

- There may be harmful “ingredients” in these interventions. For example, an untested treatment approach to helping people overcome the effects of traumatic experiences might have the unintended result of their being re-traumatized or further traumatized.

- Engaging in unproven interventions, even if not containing harmful “ingredients,” can delay a person receiving critically needed help of a type that has evidence supporting its use. For example, failure with an untested approach to treating a person’s opioid use disorder extends that person’s vulnerability to the harmful effects of opioid misuse—including potentially fatal overdose. This is difficult to condone, particularly in light of emerging evidence about certain combination approaches, like medications combined with evidence-supported behavioral therapies (medication assisted treatment, or MAT), having significant effectiveness for a range of individuals under a range of circumstances (Banta-Green, 2015).

Treatment failure with untested, ineffectual interventions can discourage a person from ever seeking help again, including from programs that have a strong track record of success. Engaging in these ineffectual interventions may also deplete a person’s resources to the point where evidence-supported interventions may not be affordable.

Despite limitations, pseudoscience does become applied. For example, the book about “psychomythology” called 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology (Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, & Beyerstein, 2010) discusses implications of the myth that most humans use only 10% of their potential brain power. The authors suggest that this myth is pervasive, in part because it would be great if true, and because it is exploitable and lucratively marketable through programs, devices, and practices available for purchase that will help people tap into the unused 90% reserve.

Learning to Recognize Pseudoscience . In Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology , the authors identified ten signs that raise the probability that we are looking at pseudoscience rather than science (Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Lohr, 2015). In their book Science and Pseudoscience in Social Work , Thyer and Pignotti (2015) help explain these signs. The ten signs are summarized here.

- Excuses, excuses, excuses. When a strongly held belief fails to be supported by rigorous empirical evidence, proponents of that belief may generate excuses to explain away the failure. These excuses are often unsupported by evidence. Hundreds of examples are present in recent political arguments aired on news talk shows. In science, when an expected result is not observed through application of scientific method, new hypotheses are generated to explain the unexpected results—then these new hypotheses are tested through scientific methods.

- Absence of self-correction makes the belief grow stronger . In pseudoscience, erroneous conclusions go untested, so corrections of theory and conclusions do not happen. Proponents of an untested, erroneous belief have no impetus to make corrections and critical questioning may lead them to “dig in their heels” more strongly. Scientists admittedly do make mistakes, but errors are eventually eliminated through application of scientific methods.

- Conspiracy theories. Proponents of a pseudoscientific belief may argue that scientific review of their “evidence” is never going to be favorable because of bias built into the scientific process and the science community. The approach is a “blame the system” strategy, as opposed to recognizing the flaws in their work. Pseudoscience is not likely to survive peer-review scrutiny because the methodologies, assumptions, and/or conclusions are flawed. Of concern in the information technology era are the many open-source journals appearing globally that claim peer-review and falsify editorial board membership. These “predatory journals” do not provide the review services present with legitimate journals and may be challenging for information consumers to spot (more on this topic in Chapter 4).

- & 5. combined: Shifting the burden of proof. A sign of pseudoscientific beliefs involves demanding that critics prove them wrong (rather than assuming responsibility for proving the claim right). In science, the burden of proof is on the one making the claim. This goes along with the sign where promoters of a pseudoscientific claim seek only confirmatory evidence, not any evidence that might disprove the claim. Scientists, however, “bend over backward” to design studies that “test and potentially falsify our most cherished notions” (Thyer & Pignotti, p. 10).

- Unlike anything seen before. A common claim with any pseudoscientific beliefs is that it represents a totally new phenomenon, a dramatically different innovation, unlike anything seen before. In science, innovation is derived from existing models, theories, or interventions. Often the innovation involves a unique, novel, new way of thinking about what came before, but connectivity between past, present, and future can be demonstrated. With pseudoscience, claims of the extraordinary are involved, disconnecting the innovation from anything in the past. “Hence, the well-known saying that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence applies” (Thyer & Pignotti, 2015, p. 11).

- The power of testimonials. Promoters of pseudoscientific innovations rely heavily on testimonial statements and anecdotal “evidence” provided by those who have been swayed into belief. While it may be true that an individual providing the testimonial was helped by the innovation, this alone does not constitute reliable scientific evidence. It does not attempt to rule out influences such as social desirability, placebo effects, and poor retrospective recall on the person’s perceptions. The proponents of a pseudoscientific claim also do not share any complaints or reports of negative results in their advertising. This is at the heart of recent challenges to how social media product reviews are biased and potentially unreliable.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, consciousness is merely the potentiality of quantum locality expressing itself beyond the constraints of four-dimensional space-time. And, that is the externalization of what we call love.”

“Mindfulness, on the other hand, differentiates itself into the multi-dimensional expanse of external reality. It really is that simple. Quantum perception embraces all potential space-time events exponentially. Cosmic balance is simply the way the universe transcodes the raw potential of quantum energy into unbridled happiness.”

- One size fits everything . In the world of fashion, “one size fits all” is a false claim—there are always going to be individuals for whom that item is too large, too small, too short, or too long. The same is true in social work—the most effective possible interventions still fail to help some individuals. It is important for science to identify for whom an intervention might not work as intended; future scientific work might be able to unravel the reasons and create interventions targeted specifically to those individuals. Pseudoscientific claims tend to be overly inflated—the interventions are often advertised as working for everyone and/or for everything. A scientific approach requires evidence that it works for each condition claimed.

- The Combo Meal. Just as fast-food eateries offer consumers a combination meal option, rather than ordering individual items, pseudoscientific approaches are often presented as part of a package—where the other parts of the package might have supporting evidence. What makes this pseudoscience is that the new add-ons have not been scientifically evaluated independently, and the combination may not have the support of evidence, either. Science does not stop at demonstrating that an intervention has an effect on outcomes; a great deal of effort is directed to understanding the mechanisms of change, how the changes are produced. Not only would each intervention alone be tested, the mechanisms by which they operate would be studied, as would their interactions when combined.

When broken down and analyzed this way, you might wonder why people believe in pseudoscience, especially in the face of challenges from more critical thinkers. At least two forces are in play at these times. One is that people sometimes desperately seek simple, effective solutions to difficult problems. Parents tormented by watching their child disappear into the altered state of schizophrenia, individuals haunted by the cravings induced by addiction, anyone who experiences wrenching grief over the death of someone they love: these people are particularly susceptible to pseudoscientific claims.

The second reason people often stick to pseudoscientific beliefs despite a lack of evidence relates to a psychological phenomenon known as cognitive dissonance. A significant internal conflict is created when a person’s deeply held belief or attitude is challenged by contradictory beliefs, attitudes, or evidence. The discomfort of this conflicted experience is called cognitive dissonance . The person is left with few choices: change the original belief/attitude to fit the new information, remain in limbo with the two in conflict, or refute the new information and stick to the original belief/attitude. Remaining in limbo is an extremely uncomfortable state, so the person is likely to restore balance and comfort by selecting one of the other two options. Thus, it is not unusual for a person to reject the new evidence and cling to the original belief.

Consider the example of how you might respond to a homeless person on the street who asks you for money. Why does this scenario make you feel uncomfortable? On one hand, you see yourself as a kindly, generous, giving person who cares about other people. On the other hand, you do not want to give your hard-earned money away to strangers. These two beliefs come into conflict when the person in need asks for money, a conflict you experience as the uncomfortable state of cognitive dissonance. (One solution is to resort to rationalization to resolve the conflict and not give the money: it is not good to reinforce this behavior, the money might do harm if the homeless person buys alcohol or drugs with it, someone else with more money than I have will donate, my taxes go to providing services to this type of person so I have already donated, letting on that I have any money will make me vulnerable to being robbed, and other reasons.)

Emerging Science. Does all of this mean that all unproven techniques are pointless and should be avoided? No, not really. After all, we should consider the observation attributed to Sir Isaac Newton:

“What we know is a drop, what we don’t know is an ocean.”

Knowledge and science are always emerging and evolving. It is possible that what is unheard of today is going to be common knowledge in the future. In other words, what is today an alternative or complementary treatment approach may eventually become a standard practice based on evidence of its effectiveness and safety. For example, not long ago, meditation practices were considered to be unconfirmed alternative mental health intervention strategies. Evidence supports the inclusion of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and meditation alongside other intervention strategies for addressing a range of mental health concerns (Edenfield & Saeed, 2012). This includes stress reduction, anxiety, depression, and combat veterans’ post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Khusid & Vythilingam, 2016, Perestelo-Perez, et al., 2017).

A more current conundrum concerns the use of EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy as a treatment approach for addressing PTSD. As scientific study progresses, elements of this therapy that are similar to other evidence-supported approaches seem to have significant treatment benefits, but it is unclear that all of the eye-movement procedures are necessary elements (Lancaster, Teeters, Gros, & Back, 2016). Investigators are learning more about EMDR as the mechanisms of change in the treatment process are being more systematically and scientifically investigated. This EMDR therapy example fits into that part of the ocean about which we do not know enough. It serves as a reminder that we need to be mindful of the tension between what we know is true, what could be true, and what masquerades as truth.

Distinguishing between Facts and Opinions

We hear hundreds of statements of fact and opinion every day—from family, friends, the media, and experts in our field. It is important to decipher which are facts and which are opinions in making decisions about important matters. A fact is information that can be objectively proven or demonstrated. An opinion is a personal belief or point of view, is subjective, and proof is not relevant. Just because a person expresses an opinion does not mean that person has useful knowledge to impart.

“There are in fact two things, science and opinion; the former begets knowledge, the latter ignorance” (Hippocrates, circa 395 BC).

In a 1987 essay, The Fine Art of Baloney Detection: How Not to be Fooled, Carl Sagan addressed the importance of critical thinking and a healthy degree of skepticism about the information and knowledge that we encounter. He stated that:

“Skeptical habits of thought are essential for nothing less than our survival—because baloney, bamboozles, bunk, careless thinking, flimflam and wishes disguised as facts are not restricted to parlor magic and ambiguous advice on matters of the heart. Unfortunately, they ripple through mainstream political, social, religious and economic issues in every nation” (p. 13).

It is worth noting that they also ripple through the world of professional practice, as well. So, how do we tell the difference when we are provided with practice-related information? Here are some ways of assessing the information (Surbhi, 2016).

- Is the information based on observation or research, can it be validated or verified with pieces of evidence (fact)? Or, is it based on assumptions and personal views, representing a personal perception, judgment, or belief (opinion)?

- Does it hold true in general (fact) or does it differ individually (opinion)?

- Is it presented or described in objective, unbiased words (fact) or is it expressed with subjective, biased words (opinion)?

- Is it a debatable view (opinion) or non-debatable (fact)?

- Facts can change opinions but opinions cannot change facts.

The Problem with Expert Opinion. Over years of practice, social workers develop a wealth of experience in identifying and addressing certain problems encountered in routine practice. Under the heading of “practice makes perfect,” experience contributes to developing a certain degree of practice wisdom and expert opinion. What is important in this label is the word “opinion.” Experience does not change facts, it shapes opinion. Expert opinion is not, in itself, a bad thing to turn to. The problem lies in non-critical reliance on expert opinion. Let’s consider an example that a social work intern experienced in practice.

At intake in a mental health center, Mr. R (aged 34) describes recent scary incidents where he has experienced a loss of memory for certain events and found himself in dangerous situations. Most recently, he “came to” standing on the edge of a river embankment with the potential of falling into rushing water at night. He has complete amnesia for how he came to be at the river. In supervision, the intern suggested two hypotheses: Mr. R has a dissociative disorder and these incidents might involve suicidality, or Mr. R has alcohol (or other substance-induced) blackouts. The intern’s social work supervisor discounted the first hypothesis on the grounds that dissociative disorders do not occur in men, only women. Furthermore, the supervisor stated that dissociative disorders are rare, making it unlikely that the intern would encounter this in a first semester field placement, since most practitioners never see such a case in an entire career. The supervisor indicated that the proper assessment would be a substance use disorder.

Relatively few facts are present in this example. They include:

- Mr. R was seen by the intern at intake to the mental health center.

- The intern was in the first semester of field placement.

- The client provided a description of events.

- The intern offered two hypotheses.

- Dissociative disorders are rare.

- The supervisor did not address the potential suicidality risk of the client’s reported incidents.

The following either fall short of being demonstrable facts or represent opinion:

- The intern has the client’s description of what happened but does not know for a fact that these things happened.

- Dissociative disorders do not occur in men, only in women (they are more common among women but do occur among men).

- Because the disorder is rare, this would not show up in a first-semester internship caseload (a classic logic fallacy).

- The proper assessment is substance use disorder.

Based on this analysis, the social work intern should consider the “expert opinion” of the supervisor but should also seek more information to confirm the hypothesis of a substance use disorder. The intern should also keep an open mind to the other possibilities, including dissociative disorder (often related to a trauma experience) and suicidality, and seek information that either supports or refutes these alternative conclusions.

The Problem with Groupthink . Sometimes an individual makes decisions or judgments in conformity with a group’s thinking, decisions that run contrary to what that individual would have decided alone. The process of group think typically refers to faulty decision-making resulting in a group’s systematic errors. Groupthink is characterized by individuals abandoning their own critical analysis, reality testing, and reasoning—possibly abandoning their own moral reasoning (Street, 1997). An example discussed by the originator of the groupthink concept was the space shuttle Challenger disaster: the commission appointed to determine the probable causes of this incident concluded, among other things, that “a highly flawed decision process was an important contributing cause of the disaster (Janis, 1991, p. 235). A more everyday example follows:

Four friends on vacation at Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park hiked out to view an active volcano. They arrived at a point where park rangers had posted signs indicating that no one should go further because of the danger of breaking through thin lava. The group members were disappointed that they could only see the active lava flow in the distance. The group’s informal leader announced they had come this far and it looked safe enough; he encouraged everyone to follow him out onto the lava bed to get a closer look. Two other members started to willingly go along with him. One member decided that she was not going to cave in to group think, and told the others so. The two following the leader soon turned back, as well, conceding that this was ill-advised. The “leader” eventually agreed, and returned safely, too.

Critics of the original groupthink model proposed by Janis (1991) argue with the emphasis placed on certain aspects of group cohesion as a precursor to the observation that group decision-making can be faulty. However, researchers have observed that “the propensity for the group to display groupthink symptoms” is greatest when the group is characterized by a high degree of cohesion based on the socioemotional dimension and a low degree of task-oriented cohesion (Street, 2017, p. 78). This difference in groupthink occurrence is attributed to the importance placed on analytical (critical) thinking in task-oriented groups. These findings have important implications for social work practitioners working in organizations and communities, in particular.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

13 Social Work Methods & Interventions for Helping Others

While social work as a profession has remained in a state of flux for some years, dedicated professionals continue to support individuals, families, and communities at their most troubled times.

Their professional dedication remains underpinned by core skills, including a “commitment to human, relation-based practice” and methods and interventions garnered from multiple disciplines (Rogers, Whitaker, Edmondson, & Peach, 2020, p. 9).

This article introduces how social workers select the best approaches and interventions for meeting the needs of their service users.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Selecting an appropriate method & intervention, top 5 methods used by social workers, 8 best social work interventions, social work & domestic violence: 4 helpful methods, positivepsychology.com’s useful resources, a take-home message.

The “constantly evolving nature of social life” has made it difficult to build a single and standard model for social work (Parker, 2013, p. 311). A framework that offers a clear process for social workers to engage with service users and implement appropriate interventions is, however, vital.

As a result, social work has combined various interdisciplinary concepts and social work theories with firsthand, experiential knowledge to develop an evidence base for social workers’ decisions.

While more than one model is used to describe social work practice, Parker (2013) offers a simplified perspective built from three elements: assessment , intervention , and review.

The model is not linear; the stages merge, overlap, and require a degree of flexibility, analysis, and critical thinking to implement (Parker, 2013).

Although the final review stage is vital to social workers’ “statutory and legal obligations” and in ensuring care plans remain appropriate, this article focuses on choosing suitable methods of assessment and intervention (Parker, 2013, p. 317).

What is an assessment?

The assessment stage aims to understand the situation affecting the service user, directly or via referral. It can be complex, often involving many contributing factors, and sometimes seem as much art as science (Parker, 2013).

Typically, assessments are perspectives constructed at a particular time and place, and include the following elements (Parker, 2013):

- Preparation , planning , and engagement involve working with the individual requiring support to introduce the need to perform an assessment and agree how the social worker will carry it out.

- Collecting data and forming a picture help social workers understand the situation better.

- Preliminary analysis includes interpreting the data and testing out “thoughts and hunches” (Parker, 2013, p. 314).

- Deeper analysis and shared negotiation are required following testing to put together an interpretation. This can offer the client or referrer an alternative way of viewing the problem.

- Construct an action plan collaboratively.

Throughout the assessment, it is essential to engage and partner with all interested parties, sharing the reasons for the evaluation, how it will be used, and the rights of those involved.

“A good assessment allows the social worker to plan openly with service users what comes next” (Parker, 2013, p. 315). The plan forms the basis for selecting or putting together the intervention and how goals and objectives will be met.

What is an intervention?

The selection of methods and interventions is further influenced by the social worker’s underlying belief systems, value bases, and theoretical preferences.

The term intervention is sometimes challenged within social work because of its suggestion of doing something to others without their consent. As with counseling and therapy, it is most valuable when put together as part of an alliance between social workers and service users (Parker, 2013).