Redirect Notice

Sample applications and documents.

As you gain experience writing your own applications and progress reports, examples of how others presented their ideas can help. NIH also provides attachment format examples, sample language, and more resources below.

Sample Grant Applications

With the gracious permission of successful investigators, some NIH institutes have provided samples of funded applications, summary statements, and more. When referencing these examples, it is important to remember:

- The best way to present your science may differ substantially from the approaches shown here. Seek feedback on your draft application from mentors and others.

- Samples are not available for all grant programs. Because many programs have common elements, the available samples can still be helpful as a demonstration of effective ways to present information.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

- Sample Applications and Summary Statements (R01, R03, R15, R21, R33, SBIR, STTR, K, F, G11, and U01)

- NIAID Sample Forms, Plans, Letters, Emails, and More

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

- Behavioral Research Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21)

- Cancer Epidemiology Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21, R37)

- Implementation Science Grant Applications (R01, R21, R37)

- Healthcare Delivery Research Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21, R50)

National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)

- Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) Applications and Summary Statements (K99/R00, K01, R01, R03, and R21)

- NHGRI Sample Consent Forms

National Institute on Aging (NIA)

- K99/R00: Pathway to Independence Awards Sample Applications and summary statements

- NIA Small Business Sample Applications (SBIR and STTR Phase 1, Phase 2, and Fast-Track)

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

- Research Project Grants (R01) Sample Applications and Summary Statements

- Early Career Research (ECR) R21 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

- Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant (R21) Sample Applications and Summary Statements

NIH Formats, Sample Language, and Other Examples

NIH provides additional examples of completed forms, templates, plans, and other sample language for reference. Your chosen approach must follow the instructions in your funding opportunity and the How to Apply – Application Guide .

Formats and Templates

- Application Format Pages for biographical sketches, other support, fellowship and training data tables, Data Management and Sharing (DMS) plans, reference letters, additional senior/key persons, additional performance sites, and more

- Animal Documents for animal welfare assurances, checklist, study proposal, and more from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW)

Sample Plans

- Authentication of Key Biological and/or Chemical Resources Plans

- Data Management and Sharing (DMS) Plans

- Model Organism Sharing Plans

- Multiple Principal Investigators, Project Leadership Plans

Other Examples

- Allowable Appendix Materials

- Application Titles, Abstracts, and Public Health Relevance Statements: Communicating Research Intent and Value

- Biosketches

- Informed Consent for Certificates of Confidentiality

- Informed Consent for Secondary and Genomic Research

- Other Support

- Scientific Rigor

- Person Months FAQ on Calculations

- Project Outcomes for Research Performance Progress Report (RPPR)

Looking for application forms?

- For a preview, go to Annotated Form Sets .

- To access fillable forms for your opportunity, you must use one of the Submission Options .

Check online guidance and direct your questions to staff in your organization's sponsored programs office. If you still need assistance, find NIH contacts at Need Help?

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS. A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Attention: Multifactor authentication is required to sign into Research.gov effective on Oct. 27, 2024. See Dear Colleague Letter (NSF 25-011 ) .

Funding at NSF

The U.S. National Science Foundation offers hundreds of funding opportunities — including grants, cooperative agreements and fellowships — that support research and education across science and engineering.

Learn how to apply for NSF funding by visiting the links below.

Finding the right funding opportunity

Learn about NSF's funding priorities and how to find a funding opportunity that's right for you.

Preparing your proposal

Learn about the pieces that make up a proposal and how to prepare a proposal for NSF.

Submitting your proposal

Learn how to submit a proposal to NSF using one of our online systems.

How we make funding decisions

Learn about NSF's merit review process, which ensures the proposals NSF receives are reviewed in a fair, competitive, transparent and in-depth manner.

NSF 101 answers common questions asked by those interested in applying for NSF funding.

Research approaches we encourage

Learn about interdisciplinary research, convergence research and transdisciplinary research.

Newest funding opportunities

Announcing the opportunity for nsf researchers to participate in biomade project calls as part of an integrated project team, addressing systems challenges through engineering teams (ascent), cultural anthropology program senior research awards (ca-sr), building synthetic microbial communities for biology, mitigating climate change, sustainability and biotechnology (synthetic communities).

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

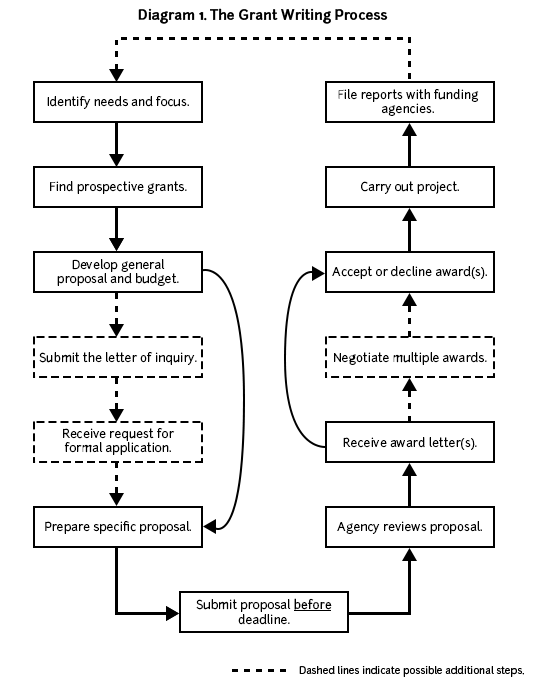

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.

Final decisions about which proposals are funded often come down to whether the proposal convinces the reviewer that the research project is well planned and feasible and whether the investigators are well qualified to execute it. Throughout the proposal, be as explicit as possible. Predict the questions that the reviewer may have and answer them. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) note that reviewers read with three questions in mind:

- What are we going to learn as a result of the proposed project that we do not know now? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is it worth knowing? (significance)

- How will we know that the conclusions are valid? (criteria for success) (2)

Be sure to answer these questions in your proposal. Keep in mind that reviewers may not read every word of your proposal. Your reviewer may only read the abstract, the sections on research design and methodology, the vitae, and the budget. Make these sections as clear and straightforward as possible.

The way you write your grant will tell the reviewers a lot about you (Reif-Lehrer 82). From reading your proposal, the reviewers will form an idea of who you are as a scholar, a researcher, and a person. They will decide whether you are creative, logical, analytical, up-to-date in the relevant literature of the field, and, most importantly, capable of executing the proposed project. Allow your discipline and its conventions to determine the general style of your writing, but allow your own voice and personality to come through. Be sure to clarify your project’s theoretical orientation.

Develop a general proposal and budget

Because most proposal writers seek funding from several different agencies or granting programs, it is a good idea to begin by developing a general grant proposal and budget. This general proposal is sometimes called a “white paper.” Your general proposal should explain your project to a general academic audience. Before you submit proposals to different grant programs, you will tailor a specific proposal to their guidelines and priorities.

Organizing your proposal

Although each funding agency will have its own (usually very specific) requirements, there are several elements of a proposal that are fairly standard, and they often come in the following order:

- Introduction (statement of the problem, purpose of research or goals, and significance of research)

Literature review

- Project narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes or deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination)

- Budget and budget justification

Format the proposal so that it is easy to read. Use headings to break the proposal up into sections. If it is long, include a table of contents with page numbers.

The title page usually includes a brief yet explicit title for the research project, the names of the principal investigator(s), the institutional affiliation of the applicants (the department and university), name and address of the granting agency, project dates, amount of funding requested, and signatures of university personnel authorizing the proposal (when necessary). Most funding agencies have specific requirements for the title page; make sure to follow them.

The abstract provides readers with their first impression of your project. To remind themselves of your proposal, readers may glance at your abstract when making their final recommendations, so it may also serve as their last impression of your project. The abstract should explain the key elements of your research project in the future tense. Most abstracts state: (1) the general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be as explicit as possible in your abstract. Use statements such as, “The objective of this study is to …”

Introduction

The introduction should cover the key elements of your proposal, including a statement of the problem, the purpose of research, research goals or objectives, and significance of the research. The statement of problem should provide a background and rationale for the project and establish the need and relevance of the research. How is your project different from previous research on the same topic? Will you be using new methodologies or covering new theoretical territory? The research goals or objectives should identify the anticipated outcomes of the research and should match up to the needs identified in the statement of problem. List only the principle goal(s) or objective(s) of your research and save sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Many proposals require a literature review. Reviewers want to know whether you’ve done the necessary preliminary research to undertake your project. Literature reviews should be selective and critical, not exhaustive. Reviewers want to see your evaluation of pertinent works. For more information, see our handout on literature reviews .

Project narrative

The project narrative provides the meat of your proposal and may require several subsections. The project narrative should supply all the details of the project, including a detailed statement of problem, research objectives or goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes or deliverables, and evaluation and dissemination of the research.

For the project narrative, pre-empt and/or answer all of the reviewers’ questions. Don’t leave them wondering about anything. For example, if you propose to conduct unstructured interviews with open-ended questions, be sure you’ve explained why this methodology is best suited to the specific research questions in your proposal. Or, if you’re using item response theory rather than classical test theory to verify the validity of your survey instrument, explain the advantages of this innovative methodology. Or, if you need to travel to Valdez, Alaska to access historical archives at the Valdez Museum, make it clear what documents you hope to find and why they are relevant to your historical novel on the ’98ers in the Alaskan Gold Rush.

Clearly and explicitly state the connections between your research objectives, research questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and outcomes. As the requirements for a strong project narrative vary widely by discipline, consult a discipline-specific guide to grant writing for some additional advice.

Explain staffing requirements in detail and make sure that staffing makes sense. Be very explicit about the skill sets of the personnel already in place (you will probably include their Curriculum Vitae as part of the proposal). Explain the necessary skill sets and functions of personnel you will recruit. To minimize expenses, phase out personnel who are not relevant to later phases of a project.

The budget spells out project costs and usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with the budget detailed as line items and a budget narrative (also known as a budget justification) that explains the various expenses. Even when proposal guidelines do not specifically mention a narrative, be sure to include a one or two page explanation of the budget. To see a sample budget, turn to Example #1 at the end of this handout.

Consider including an exhaustive budget for your project, even if it exceeds the normal grant size of a particular funding organization. Simply make it clear that you are seeking additional funding from other sources. This technique will make it easier for you to combine awards down the road should you have the good fortune of receiving multiple grants.

Make sure that all budget items meet the funding agency’s requirements. For example, all U.S. government agencies have strict requirements for airline travel. Be sure the cost of the airline travel in your budget meets their requirements. If a line item falls outside an agency’s requirements (e.g. some organizations will not cover equipment purchases or other capital expenses), explain in the budget justification that other grant sources will pay for the item.

Many universities require that indirect costs (overhead) be added to grants that they administer. Check with the appropriate offices to find out what the standard (or required) rates are for overhead. Pass a draft budget by the university officer in charge of grant administration for assistance with indirect costs and costs not directly associated with research (e.g. facilities use charges).

Furthermore, make sure you factor in the estimated taxes applicable for your case. Depending on the categories of expenses and your particular circumstances (whether you are a foreign national, for example), estimated tax rates may differ. You can consult respective departmental staff or university services, as well as professional tax assistants. For information on taxes on scholarships and fellowships, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/ .

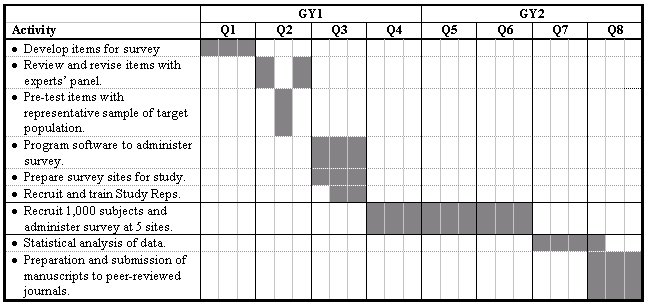

Explain the timeframe for the research project in some detail. When will you begin and complete each step? It may be helpful to reviewers if you present a visual version of your timeline. For less complicated research, a table summarizing the timeline for the project will help reviewers understand and evaluate the planning and feasibility. See Example #2 at the end of this handout.

For multi-year research proposals with numerous procedures and a large staff, a time line diagram can help clarify the feasibility and planning of the study. See Example #3 at the end of this handout.

Revising your proposal

Strong grant proposals take a long time to develop. Start the process early and leave time to get feedback from several readers on different drafts. Seek out a variety of readers, both specialists in your research area and non-specialist colleagues. You may also want to request assistance from knowledgeable readers on specific areas of your proposal. For example, you may want to schedule a meeting with a statistician to help revise your methodology section. Don’t hesitate to seek out specialized assistance from the relevant research offices on your campus. At UNC, the Odum Institute provides a variety of services to graduate students and faculty in the social sciences.

In your revision and editing, ask your readers to give careful consideration to whether you’ve made explicit the connections between your research objectives and methodology. Here are some example questions:

- Have you presented a compelling case?

- Have you made your hypotheses explicit?

- Does your project seem feasible? Is it overly ambitious? Does it have other weaknesses?

- Have you stated the means that grantors can use to evaluate the success of your project after you’ve executed it?

If a granting agency lists particular criteria used for rating and evaluating proposals, be sure to share these with your own reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

| Jet Travel | ||||

| RDU-Kigali (roundtrip) | 1 | $6,100 | $6,100 | |

| Maintenance Allowance | ||||

| Rwanda | 12 months | $1,899 | $22,788 | $22,788 |

| Project Allowance | ||||

| Research Assistant/Translator | 12 months | $400 | $4800 | |

| Transportation within country | ||||

| –Phase 1 | 4 months | $300 | $1,200 | |

| –Phase 2 | 8 months | $1,500 | $12,000 | |

| 12 months | $60 | $720 | ||

| Audio cassette tapes | 200 | $2 | $400 | |

| Photographic and slide film | 20 | $5 | $100 | |

| Laptop Computer | 1 | $2,895 | ||

| NUD*IST 4.0 Software | $373 | |||

| Etc. | ||||

| Total Project Allowance | $35,238 | |||

| Administrative Fee | $100 | |||

| Total | $65,690 | |||

| Sought from other sources | ($15,000) | |||

| Total Grant Request | $50,690 |

Jet travel $6,100 This estimate is based on the commercial high season rate for jet economy travel on Sabena Belgian Airlines. No U.S. carriers fly to Kigali, Rwanda. Sabena has student fare tickets available which will be significantly less expensive (approximately $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788 Based on the Fulbright-Hays Maintenance Allowances published in the grant application guide.

Research assistant/translator $4,800 The research assistant/translator will be a native (and primary) speaker of Kinya-rwanda with at least a four-year university degree. They will accompany the primary investigator during life history interviews to provide assistance in comprehension. In addition, they will provide commentary, explanations, and observations to facilitate the primary investigator’s participant observation. During the first phase of the project in Kigali, the research assistant will work forty hours a week and occasional overtime as needed. During phases two and three in rural Rwanda, the assistant will stay with the investigator overnight in the field when necessary. The salary of $400 per month is based on the average pay rate for individuals with similar qualifications working for international NGO’s in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200 The primary investigator and research assistant will need regular transportation within Kigali by bus and taxi. The average taxi fare in Kigali is $6-8 and bus fare is $.15. This figure is based on an average of $10 per day in transportation costs during the first project phase.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000 Project personnel will also require regular transportation between rural field sites. If it is not possible to remain overnight, daily trips will be necessary. The average rental rate for a 4×4 vehicle in Rwanda is $130 per day. This estimate is based on an average of $50 per day in transportation costs for the second and third project phases. These costs could be reduced if an arrangement could be made with either a government ministry or international aid agency for transportation assistance.

Email $720 The rate for email service from RwandaTel (the only service provider in Rwanda) is $60 per month. Email access is vital for receiving news reports on Rwanda and the region as well as for staying in contact with dissertation committee members and advisors in the United States.

Audiocassette tapes $400 Audiocassette tapes will be necessary for recording life history interviews, musical performances, community events, story telling, and other pertinent data.

Photographic & slide film $100 Photographic and slide film will be necessary to document visual data such as landscape, environment, marriages, funerals, community events, etc.

Laptop computer $2,895 A laptop computer will be necessary for recording observations, thoughts, and analysis during research project. Price listed is a special offer to UNC students through the Carolina Computing Initiative.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00 NUD*IST, “Nonnumerical, Unstructured Data, Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing,” is necessary for cataloging, indexing, and managing field notes both during and following the field research phase. The program will assist in cataloging themes that emerge during the life history interviews.

Administrative fee $100 Fee set by Fulbright-Hays for the sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

| Exploratory Research | Completed |

| Proposal Development | Completed |

| Ph.D. qualifying exams | Completed |

| Research Proposal Defense | Completed |

| Fieldwork in Rwanda | Oct. 1999-Dec. 2000 |

| Data Analysis and Transcription | Jan. 2001-March 2001 |

| Writing of Draft Chapters | March 2001 – Sept. 2001 |

| Revision | Oct. 2001-Feb. 2002 |

| Dissertation Defense | April 2002 |

| Final Approval and Completion | May 2002 |

Example #3: Project Timeline in Chart Format

Some closing advice

Some of us may feel ashamed or embarrassed about asking for money or promoting ourselves. Often, these feelings have more to do with our own insecurities than with problems in the tone or style of our writing. If you’re having trouble because of these types of hang-ups, the most important thing to keep in mind is that it never hurts to ask. If you never ask for the money, they’ll never give you the money. Besides, the worst thing they can do is say no.

UNC resources for proposal writing

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Holloway, Brian R. 2003. Proposal Writing Across the Disciplines. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Levine, S. Joseph. “Guide for Writing a Funding Proposal.” http://www.learnerassociates.net/proposal/ .

Locke, Lawrence F., Waneen Wyrick Spirduso, and Stephen J. Silverman. 2014. Proposals That Work . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Przeworski, Adam, and Frank Salomon. 2012. “Some Candid Suggestions on the Art of Writing Proposals.” Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrc-cdn2/art-of-writing-proposals-dsd-e-56b50ef814f12.pdf .

Reif-Lehrer, Liane. 1989. Writing a Successful Grant Application . Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wiggins, Beverly. 2002. “Funding and Proposal Writing for Social Science Faculty and Graduate Student Research.” Chapel Hill: Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science. 2 Feb. 2004. http://www2.irss.unc.edu/irss/shortcourses/wigginshandouts/granthandout.pdf.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 20 December 2019

Secrets to writing a winning grant

- Emily Sohn 0

Emily Sohn is a freelance journalist in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

When Kylie Ball begins a grant-writing workshop, she often alludes to the funding successes and failures that she has experienced in her career. “I say, ‘I’ve attracted more than $25 million in grant funding and have had more than 60 competitive grants funded. But I’ve also had probably twice as many rejected.’ A lot of early-career researchers often find those rejections really tough to take. But I actually think you learn so much from the rejected grants.”

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 577 , 133-135 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03914-5

Related Articles

- Communication

How I created a film festival to explore climate communication

Career Column 18 OCT 24

How do I tell someone that I can’t write them a strong letter of recommendation?

Career Feature 17 OCT 24

Season’s mis-greetings: why timing matters in global academia

Career Column 17 OCT 24

Does the 2024 US election matter to science? Take Nature’s poll

News 07 OCT 24

New peer-review trial lets grant applicants evaluate each other’s proposals

Nature Index 07 OCT 24

Funders launch online resource to help researchers navigate narrative CVs

Career News 01 OCT 24

Harassed? Intimidated? Guidebook offers help to scientists under attack

News 20 SEP 24

Brazil’s ban on X: how scientists are coping with the cut-off

News 06 SEP 24

Guide, don’t hide: reprogramming learning in the wake of AI

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

2024 Recruitment notice Shenzhen Institute of Synthetic Biology: Shenzhen, China

The wide-ranging expertise drawing from technical, engineering or science professions...

Shenzhen,China

Shenzhen Institute of Synthetic Biology

Faculty Positions in Center of Bioelectronic Medicine, School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

SLS invites applications for multiple tenure-track/tenured faculty positions at all academic ranks.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

Faculty Positions, Aging and Neurodegeneration, Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine

Applicants with expertise in aging and neurodegeneration and related areas are particularly encouraged to apply.

Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine (WLLSB)

Faculty Positions in Chemical Biology, Westlake University

We are seeking outstanding scientists to lead vigorous independent research programs focusing on all aspects of chemical biology including...

Open Rank Faculty Positions – Department of Genetics and Genome Sciences

Cleveland, Ohio (US)

Case Western Reserve University-School of Medicine

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to write a successful grant application: guidance provided by the European Society of Clinical Pharmacy

Anita e weidmann, cathal a cadogan, daniela fialová, ankie hazen, martin henman, monika lutters, betul okuyan, vibhu paudyal, francesca wirth.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2022 Sep 25; Accepted 2023 Jan 12; Issue date 2023.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Considering a rejection rate of 80–90%, the preparation of a research grant is often considered a daunting task since it is resource intensive and there is no guarantee of success, even for seasoned researchers. This commentary provides a summary of the key points a researcher needs to consider when writing a research grant proposal, outlining: (1) how to conceptualise the research idea; (2) how to find the right funding call; (3) the importance of planning; (4) how to write; (5) what to write, and (6) key questions for reflection during preparation. It attempts to explain the difficulties associated with finding calls in clinical pharmacy and advanced pharmacy practice, and how to overcome them. The commentary aims to assist all pharmacy practice and health services research colleagues new to the grant application process, as well as experienced researchers striving to improve their grant review scores. The guidance in this paper is part of ESCP’s commitment to stimulate “ innovative and high-quality research in all areas of clinical pharmacy ”.

Keywords: Clinical pharmacy , Economics, Funding, Grants, Peer review, Writing

Writing research grants is a central part of any good quality research. Once a detailed research proposal has been submitted, it is subjected to an expert peer review process. Such reviews are designed to reach a funding decision, with feedback provided to improve the study for this and any future submissions. Depending on the length of the proposal, complexity of the research and experience of the research team, a proposal can take between six to twelve months to write [ 1 ]. Ample time must be given to the writing of hypothesis/research aim, budgeting, discussion with colleagues and several rounds of feedback [ 2 ]. The draft research proposal should always be completed well before the deadline to allow for last minute delays. An application which is not fully developed should not be submitted since it will most likely be rejected [ 3 ].

Despite the large effort that goes into each grant application, success rates are low. Application success rates for Horizon 2020 were < 15% [ 4 ] and < 20% for the National Institute of Health (NIH) [ 5 – 8 ]. With these statistics in mind, it is evident that often repeated submissions are required before securing funding. Due to a paucity of specific clinical pharmacy grant awarding bodies, writing a grant application for a clinical pharmacy or pharmacy practice research project often involves multidisciplinary collaborations with other healthcare professions and focus on a specific patient population or condition. There is no guarantee of success when trying to secure funding for research. Even the most seasoned researchers will have applications rejected. The key is to never give up. This commentary provides useful pointers for the planning and execution of grant writing.

Conceptualising your research idea

Before writing a research grant proposal/application, consider what the research should achieve in the short, medium, and long term, and how the research goals will serve patients, science and society [ 9 , 10 ]. Practical implications of research, policy impact or positive impact on society and active patient/public involvement are highly valued by many research agencies as research should not be conducted “only for research”, serving the researchers’ interests. EU health policy and action strategies (CORDIS database) and other national strategies, such as national mental health strategy for grants within mental disorders, should be considered, as well as dissemination strategies, project deliverables, outcomes and lay public invitations to participate. The Science Community COMPASS has developed a useful “Message Box Tool” that can help in the identification of benefits and solutions, as well as the all-important “So What?” of the research [ 11 ]. Clearly determine what the lead researcher’s personal and professional strengths, expertise and past experiences are, and carefully select the research team to close these gaps [ 12 – 14 ].

How to find the right funding call

When trying to identify the right type of grant according to the research ambitions, one should be mindful that several types of grants exist, including small project grants (for equipment, imaging costs), personal fellowships (for salary costs, sometimes including project costs), project grants (for a combination of salary and project costs), programme grants (for comprehensive project costs and salary for several staff members), start-up grants and travel grants [ 15 ]. Types of grants include EU grants (e.g. Horizon, Norway Grant), commercial grants (e.g. healthcare agencies and insurance companies), New Health Program grants ideal for new, reimbursed clinical pharmacy service projects and national grants (e.g. FWF (Austria), ARRS (Slovenia), NKFIH (Hungary), NCN (Poland), FWO (Belgium), HRZZ (Croatia), GAČR (Czech Republic), SNSF (Switzerland), SSF (Sweden). It is worth remembering that early career researchers, normally within ten years of finishing a PhD, have a particular sub-category within most grants.

Many national agencies only have one “Pharmacy” category. This results in clinical pharmacy and advanced clinical pharmacy practice projects competing with pharmaceutical chemistry, pharmaceutical biology and pharmacy technology submissions, thereby reducing the success rate as these research areas can often be very advanced in most EU countries compared to clinical and advanced pharmacy practice. A second possible submission category is “Public Health”. Several essential factors can impact the grant selection, such as research field, budget capacity, leading researcher’s experience and bilateral grants. Examples of successful clinical pharmacy funded research studies can be found in the published literature [ 16 – 20 ].

Plan, plan, plan

One key element of successful grant writing is the ability to plan and organise time. In order to develop a realistic work plan and achieve milestones, it is imperative to note deadlines and to be well-informed about the details of what is required. The development of a table or Gantt Chart that notes milestones, outcomes and deliverables is useful [ 21 ].

All funders are quite specific about what they will and will not fund. Research your potential funders well in advance. It is vital to pay attention to the aims, ambitions and guidelines of the grant awarding bodies and focus your proposal accordingly. Submitting an application which does not adhere to the guidelines may lead to very early rejection. It is helpful to prepare the grant application in such a way that the reviewers can easily find the information they are looking for [ 15 , 22 ]. This includes checking the reviewers’ reports and adding “bolded” sentences into the application to allow immediate emphasis. Reviewers’ reports are often available on the agencies’ websites. It is extremely useful to read previously submitted and funded or rejected proposals to further help in the identification of what is required in each application. Most funding agencies publish a funded project list, and the ‘Centre for Open Science (COS) Database of Funded Research’ enables tracking of funding histories from leading agencies around the world [ 23 ]. Another useful recommendation is to talk to colleagues who have been successful when applying to that particular funder. Funding agency grant officers can provide advice on the suitability of the proposal and the application process.

It is important to pay particular attention to deadlines for the grant proposal and ensure that sufficient time is allocated for completion of all parts of the application, particularly those that are not fully within one’s own control, for example, gathering any required signatures/approvals. Funders will generally not review an application submitted beyond the deadline.

Lastly, it is important to obtain insight into the decision process of grants. Research applications are sent to several reviewers, who are either volunteers or receive a small compensation to judge the application on previously determined criteria. While the judging criteria may vary from funder to funder, the key considerations are:

Is there a clear statement of the research aim(s)/research question(s)/research objective(s)?

Is the proposed research “state-of-the-art” in its field and has all relevant literature been reviewed?

Is the method likely to yield valid, reliable, trustworthy data to answer question 1.?

If the answer to the second question is ’yes’, then what is the impact of financing this study on patient care, professional practice, society etc.?

Is there sufficient confidence that the research team will deliver this study on time with expected quality outputs and on budget?

Does the study provide value for money?

How to write

The key to good grant proposal writing is to be concise yet engaging. The use of colour and modern web-based tools such as #hashtags, webpage links, and links to YouTube presentations are becoming increasingly popular to improve the interest of a submission and facilitate a swift decision-making process. Ensure use of the exact section headings provided in the guidance, and use the keywords provided in the funding call documentation to reflect alignment with the funding bodies’ key interests. Attention to detail cannot be overstated; the quality and accuracy of the research proposal reflect the quality and accuracy of the research [ 24 ]. Try to adopt a clear, succinct, and simple writing style, making the grant easy to read. Having a clear focus can help to boost a grant to the top of a reviewer’s pile [ 25 , 26 ]. A clearly stated scientific question, hypothesis, and rationale are imperative. The reviewer should not have to work to understand the project [ 27 ]. Allow for plenty of time to incorporate feedback from trusted individuals with the appropriate expertise and consider having reviews for readability by non-experts.

What to write

Abstract, lay summary and background/rationale.

Take sufficient time to draft the scientific abstract and summary for the lay public. These should clearly state the long-term goal of the research, the aim and specific testable objectives, as well as the potential impact of the work. The research aim is a broad statement of research intent that sets out what the project hopes to achieve at the end. Research objectives are specific statements that define measurable outcomes of the project [ 28 , 29 ].

The lay summary is important for non-subject experts to quickly grasp the purpose and aims of the research. This is important in light of the increased emphasis on patient and public involvement in the design of the research. The abstract is often given little attention by the applicants, yet is essential. If reviewers have many applications to read, they may form a quick judgement when reading the abstract. The background should develop the argument for the study. It should flow and highlight the relevant literature and policy or society needs statements which support the argument, but at the same time must be balanced. It should focus on the need for the study at the local, national and international level, highlighting the knowledge gap the study addresses and what the proposed research adds. Ensure this section is well-referenced. The innovation section addresses the ‘‘So what?’’ question and should clearly explain how this research is important to develop an understanding in this field of practice and its potential impact. Will it change practice, or will it change the understanding of the disease process or its treatment? Will it generate new avenues for future scientific study? [ 30 ].

Hypothesis/aims and objectives

For the hypothesis, state the core idea of the grant in one or two sentences. It should be concise, and lead to testable specific aims. This section is fundamental; if it is unclear or poorly written, the reviewers may stop reading and reject the application. Do not attempt to make the aims overly complex. Well-written aims should be simply stated. Criteria such as PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes) [ 31 ], and FINER (feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant) [ 32 ], provide useful frameworks to help in writing aim(s), research question(s), objective(s) and hypotheses. Pay attention to the distinction between aim(s), research question(s), objective(s) and hypotheses. While it is tempting to want to claim that enormously complex problems can be solved in a single project, do not overreach. It is important to be realistic [ 25 ].

Experimental design, methods and expertise

The methodology is one of the most important parts of getting a grant proposal accepted. The reviewing board should be convinced that the relevant methodology is well within the research teams’ expertise. Any evidence of potential success, such as preliminary results or pilot studies strengthen the application significantly [ 33 ]. The methodology must relate directly to the aim. Structuring this section into specific activities/ set of activities that address each research question or objective should be considered. This clarifies how each question/ objective will be addressed. Each work-package should clearly define the title of the research question/objective to be addressed, the activities to be carried out including milestones and deliverables, and the overall duration of the proposed work-package. Deliverables should be presented in table format for ease of review. Each subsequent work-package should start once the previous one has been completed to provide a clear picture of timelines, milestones and deliverables which reflect stakeholder involvement and overall organisation of the proposed project. Using relevant EQUATOR Network reporting guidelines enhances the quality of detail included in the design [ 34 ]. Key elements of this methodology are detailed in Table 1 .

Summary of the key elements of the experimental design, methods and expertise

| Key elements of experimental design, methods and expertise | |

|---|---|

| Study design | State, justify and explain the study design and methodology. |

| Setting | Where will the study be conducted? Explain and justify the setting. |

| Target population | What is the study population? What are the inclusion and exclusion criteria? |

| Sampling, sample size | Is sampling required? If so, what is the sampling approach and sample size needed? |

| Recruitment | What is the approach for recruitment? |

| Data collection | What is the plan for data collection? How are tools to be developed, tested and piloted? |

| Outcome measures | What is going to be ‘measured’ (noting that the term ‘measure’ is different in qualitative studies)? The outcome measures should directly relate to the specific research questions/ objectives. |

| Validity, reliability, trustworthiness | What steps are planned to maximise data validity and reliability (and possibly responsiveness) for quantitative studies and trustworthiness for qualitative studies? |

| Analysis | What are the plans for analysis? The analysis plan must relate directly to the research question (s)/ objective (s). |

| Monitoring | What are the milestones and key performance indicators for the study? Depending on the funding body and the nature of the study, a monitoring and oversight/ advisory committee may need to be established. |

| Limitations, mitigation | What are the risks? What could go wrong? It is imperative to highlight these and plan mitigation measures. |

| Expertise | The research team must have the appropriate level of experience and expertise from relevant disciplines to give the reviewers confidence that the study will be delivered as planned. It is not mandatory for all team members to be highly experienced, since developing research capacity is also important, however all team members should have defined roles. |

| Patient and public engagement | Depending on the funding body it may be very important to thoroughly consider patient and public involvement in the study design, development of the research aim planning of the study design, written grant proposal and participation in the proposed study [ ]. Engaging the public in the research can improve the quality and impact of the research proposal [ ]. |

| Ethics and governance | Details of ethics board approvals including to be obtained for the study are crucial as are details of all governance measures followed. |

Proposed budget

The budget should be designed based on the needs of the project and the funding agency’s policies and instructions. Each aspect of the budget must be sufficiently justified to ensure accountability to the grant awarding body [ 35 ]. Costing and justification of the time of those involved, any equipment, consumables, travel, payment for participants, dissemination costs and other relevant costs are required. The funders will be looking for value for money and not necessarily a low-cost study. Ensure that the total budget is within the allocated funding frame.

Provide a breakdown of the key work packages and tasks to be completed, as well as an indication of the anticipated duration. Include a Gantt chart (A table detailing the most general project content milestones and activities) to demonstrate that all aspects of the proposal have been well thought through [ 21 ].

Critical appraisal, limitations, and impact of the proposed research

It is important to detail any strengths and limitations of the proposed project. Omitting these will present the reviewing board with sufficient grounds to reject the proposal [ 36 ]. Provide a clear statement about the short and long-term impact of the research [ 37 , 38 ]. The reviewers will pay particular attention to the differences the study can make and how potential impact aligns with the funding bodies goals as well as national policies. This statement is essential to make an informed decision whether or not to support the application. Useful diagrams summarise the different levels of impact [ 39 ].

Table 2 provides a summary of the key elements of project grants and key questions to ask oneself.

Summary of the key elements of project grants and key questions to ask oneself.

(Adapted from [ 5 ]: Koppelmann GH, Holloway JW. Successful grant writing. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2012; 13:63–66.)

| Key questions to ask oneself | |

|---|---|

| What is the research question being addressed? How important, or how big is the identified knowledge gap? Why is this research project needed? What previous literature is available on this research topic? How innovative is the grant proposal compared to already published or ongoing research? What would the impact of the study results on healthcare, economics and society be? What research is being done by other groups? What type of methodological approach would be required in an ideal world to address this issue? What is needed to bring this research project to a wider audience? Does the researcher and team have all the relevant skills, techniques, and knowledge? Am I ready to be a principal investigator or should I be a co-investigator? |

Although the grant writing process is time-consuming and complex, support is widely available at each stage. It is important to involve colleagues and collaborators to improve the proposal as much as possible and invest time in the detailed planning and execution. Even if the grant is not awarded, do not be disheartened. Use the feedback for improvement and exercise resilience and persistence in pursuing your research ambition.

The guidance in this paper is part of ESCP’s commitment to stimulate “innovative and high-quality research in all areas of clinical pharmacy”. In a previous ESCP survey, it was found that few opportunities for collaboration (especially for grant applications) was one of the key barriers for members towards conducting research [ 40 ]. ESCP promotes networking, which is essential for multi-centre grant applications, both among ESCP members and with other organisations as it recognises the need for “multi-centre research in all areas of clinical pharmacy both within countries and between countries or differing healthcare delivery systems”. ESCP is planning to relaunch its own research grant which was paused during the pandemic, and it is also planning to provide ESCP members with information about the research grants offered by other organizations. ESCP is exploring partnering with other organisations to develop research proposals in areas of common interest and, in the near future, it will ask its members about their research priorities. Taken together, these initiatives will inform ESCP’s research strategy and help it to formulate policies to address the challenges its members face.

Acknowledgements

Research works of Assoc. Prof. Fialová were also supported by the institutional program Cooperation of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Charles University.

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. This work was conducted without external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Devine EB. The art of obtaining grants. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2009;66(15):580–7. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070320. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Arthurs OJ. Think it through first: questions to consider in writing a success grant application. Paediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1507–11. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3053-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Elsevier Connect. 5 pitfalls to writing a wining grant application for your research. 2019. https://www.elsevier.com/connect/5-pitfalls-to-writing-a-winning-grant-application-for-your-research . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 4. Best practice guidelines WASP (write a Scientific Paper): writing a research grant – 1, applying for funding. Early Hum Dev. 2018;127:106–8. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.07.013. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. National Institute for Health (NIH). Success Rates: R01-Equivalent and Research Project Grants. 2022. https://report.nih.gov/nihdatabook/category/10 . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 6. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). Processing Times and Success rates., 2021. https://www.dfg.de/en/dfg_profile/facts_figures/statistics/processing_times_success_rates/index.html . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 7. Mervis J. Odds improve for winning NSF grants, but drop in applications troubles some observers. Science. 2022 doi: 10.1126/science.adc9471. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Myklebust JP. Should the ERC be worried about its low success rate? University World News. 2021 https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210521093708482 Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 9. Koppelmann GH, Holloway JW. Successful grant writing. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2012;13:63–6. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2011.02.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Kanji S. Turning your research idea into a proposal worth funding. Canadian J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(6):458. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v68i6.1502. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. COMPASS. The Message Box. 2022. https://www.compassscicomm.org/leadership-development/the-message-box/ . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 12. Ebadi A, Schiffauerova A. How to receive more funding for your research? Get connected to the right people. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0133061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133061. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Laurent GJ. Getting grant applications funded: lessons from the past and advice for the future. Thorax. 2004;59(12):1010–1. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.024182. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Research funding. Vitae, realising the potential of researchers. Available at https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researcher-careers/pursuing-an-academic-career/research-funding Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 15. Wellcome Trust. 2022. https://wellcome.org/grant-funding . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 16. McIntosh J, Alonso A, MacLure K, et al. Case study of polypharmacy management in nine European countries: implications for change management and implementation. PLOS One. 2018;13(4):e0195232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195232. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. de Godoi Rezende Costa Molino C, Chocano-Bedoya PO, Sadlon A. Prevalence of polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults from seven centres in five european countries: a cross-sectional study of DO-HEALTH. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e051881. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051881. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Bhagavathula AS, Assen Seid M, Adane A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of Multimorbidity, Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in older outpatients: Findindgs from EuroAgeism H2020 ESR7 Project in Ethiopia. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(9):844. doi: 10.3390/ph14090844. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Watson MC, Ferguson J, Barton GR, et al. A cohort study of influences, health outcomes and costs of patients’ health-seeking behaviour for minor ailments from primary and emergency care settings. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006261. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006261. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Patton DE, Pearce CJ, Cartwright M, et al. A non-randomised pilot study of the solutions for Medication adherence problems (S-MAP) intervention in community pharmacies to support older adults adhere to multiple medications. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021;7:18. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00762-3. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Gantt.com. What is a Gantt chart. 2022. https://www.gantt.com . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 22. Gholipour A, Lee EY, Warfield SK. The anatomy and art of writing a successful grant application: a pratical step-by-step approach. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1512–7. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-3051-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Centre for Open Science. 2022. https://www.cos.io . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 24. Liu JC, et al. Grant-writing pearls and pitfalls: Maximizing Funding Opportunities. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154(2):226–32. doi: 10.1177/0194599815620174. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Sohn E. Secrets to writing a winning grant. Nature. 2020;577:133–5. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-03914-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Powell K. The best-kept secrets to winning grants. Nat News. 2017;545:399. doi: 10.1038/545399a. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. McGee R. Keys to writing successful NIH research and career development grant applications. https://www.northwestern.edu/climb/resources/written-communication/Effective_NIH_Research_Career_Development_Proposals_Overview.pdf . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 28. Anon. Developing Research Aims and Objectives. In: David R Thomas, Ian Hodges. Designing and Planning Your Research Project: Core Skills for Social and Health Researchers. Sage Publications. 2010. P. 38–47.

- 29. Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, et al. Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010;53(4):278. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. University of York. Impact in research grant applications. 2022. https://www.york.ac.uk/staff/research/research-impact/impact-in-grants/ . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 31. Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. Designing Clinical Research. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Best practice guidelines WASP (write a Scientific Paper): writing a Research Grant – 2, Drafting the proposal. Early Hum Dev. 2018;127:109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.07.014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. EQUATOR Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. 2022. https://www.equator-network.org/ . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 35. Patil GP. How to plan and write a budget for research grant proposal? J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2019;10(20):139–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.08.005. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. UW-Madison Writing Center. Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics. 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8642360/ . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 37. UK Research Impact. Research Excellence Framework. 2021. Available at https://re.ukri.org/research/ref-impact/ . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 38. Hughes A, Kitson M, Bullock A, et al. The dual funding structure for research in the UK: research council and funding council 244 allocation methods and the pathways to impact of UK academics. Cambridge: Department of Innovation and Skills, UK Innovation Research Centre; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Research Councils UK. Pathways to impact. Available at https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/do-engagement/funding/pathways-impact#:~text=A%20clearly%20thought%20through%20and,our%20economic%20and%20social%20wellbeing . Accessed 05 Dec 2022.

- 40. Stewart D, Paudyal V, Cadogan C, et al. A survey of the European society of clinical pharmacy members’research involvement, and associated enablers and barriers. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(4):1073–87. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01054-9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (549.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sample Grant Applications. With the gracious permission of successful investigators, some NIH institutes have provided samples of funded applications, summary statements, and more. When referencing these examples, it is important to remember: Warning Alert.

Read about the basics of writing an effective scientific research proposal, and the differences between research proposals, grants and cover letters here.

The U.S. National Science Foundation offers hundreds of funding opportunities — including grants, cooperative agreements and fellowships — that support research and education across science and engineering. Search for funding. Search funded projects (awards) Learn how to apply for NSF funding by visiting the links below.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

Grant writing is a job requirement for research scientists who need to fund projects year after year. Most proposals end in rejection, but missteps give researchers a chance to learn how to...

This commentary provides a summary of the key points a researcher needs to consider when writing a research grant proposal, outlining: (1) how to conceptualise the research idea; (2) how to find the right funding call; (3) the importance of planning; (4) how to write; (5) what to write, and (6) key questions for reflection during preparation.